1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infective disease which is a global public health issue with high disease burden [

1]. In 2024, the number of TB cases in Republic of Korea (ROK) was 17,944 (35.2 cases per 100,000 population), continuing a decreasing trend over the past decade [

2] However, the proportion of medical aid recipients has increased from 2.9% in 2023 to 11.3% in 2024 which poses a greater economic burden[

2]. Patients with tuberculosis are usually treated in outpatient department. A previous study showed that the proportion of patients admitted through the emergency room and intensive care unit (ICU) was higher in the decedent group than the survivor group[

3]. Hospitalization uses more medical resources and is related with poorer outcome. By identifying risk factors for hospitalization and providing intense interventions to high-risk patients, favorable outcomes can be achieved while reducing the overall burden.

Nutritional status and comorbidities were identified as risk factors associated with mortality in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis[

4]. Nutrition status was assessed by nutrition risk score which consists of body mass index (BMI), serum albumin, serum cholesterol, and lymphocyte count[

5]. Kim et. al have shown that mortality was associated with decreased hemoglobin, lymphocyte, albumin and cholesterol. Independent predictors associated with mortality were blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and admission during treatment of tuberculosis [

3]. A retrospective cohort study from Australia suggested that all-cause mortality was associated with renal impairment in patients with tuberculosis in a low tuberculosis prevalence[

6]. Anti TB drug induced liver injury contributes to longer hospital stays and increased economic burden [

7]. An inflammatory biomarker, C-reactive protein (CRP) was associated with mortality in critically ill patients with tuberculosis [

8]. Therefore, we considered nutrition status, kidney function, liver function, and CRP as variables to analyze the associated with hospitalization in patients with tuberculosis.

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox regression model selects variables and shrinks coefficients in the Cox proportional hazard regression model[

9]. Previous studies applied LASSO Cox screening genes to establish prognostic model for cancers [

10,

11]. Zhou et al. have demonstrated that LASSO Cox regression presents accurate and prognostic prediction for patients with alpha-fetoprotein-negative hepatocellular carcinoma (AFP-HCC) [

12]. The aim of this study was to identify risk factors for hospitalization and establish LASSO Cox regression model to predict hospitalization in patients with TB.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

Patients who were first diagnosed with TB at Kangwon National University Hospital between January 2024 and August 2025 were included in this study. Data were extracted from the Kangwon National University Hospital Clinical Data Warehouse (CDW). A total of 117 patients were enrolled in this study.

2.2. Variables and Outcome definition

Demographic data including age, gender and laboratory data including total white blood cell (WBC) count, neutrophil, lymphocyte, hemoglobin, creatinine, albumin, aspartate-aminotransferase (AST), alanin-aminotransferase (ALT), and total cholesterol were defined as variables. Creatinine was used to represent kidney function and ALT was used to represent liver function. Lymphocyte, albumin, and total cholesterol were used to represent nutrition status. Total WBC, neutrophil, and CRP were used to represent the severity of inflammation. Hospitalization for any cause within the follow-up period after TB diagnosis was defined as the outcome. Patients were followed from the date of the TB diagnosis until the date of hospitalization, or the end of follow-up. The follow-up time ranged from 1 to 180days.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables are presented as numbers with percentages. Patients were grouped into two groups: Hospitalized group and outpatient group. Unpaired t-test was used for the comparison of continuous variables between the two groups and Chi-squared test was performed for the comparison of categorical variables.

LASSO Cox regression was performed to select variables for hospitalization in patients with TB. Patients who had any missing values in the variables were excluded in the analysis. To avoid overfitting due to the relatively small number of events, we used 5-fold cross-validation to determine the optimal penalty parameter (λ). Because the sample size was small and the number of events was limited, we did not perform a fixed test set. Instead, model performance was estimated using out-of-fold (OOF) predictions from 5-fold cross-validation. In each outer fold, a LASSO Cox model was trained on the remaining folds and risk scores were calculated for the held-out fold. The λ value that minimized the partial likelihood deviance was selected. Variables at the optimal λ were selected and were then included in the LASSO Cox model. Concordance Index (C-Index) was calculated to evaluate the prediction performance of the model.

A univariable Cox proportional hazards regression model was performed to identify risk factors for hospitalization for any cause. All variables with p< 0.05 in the univariable analysis were included in the multivariable analysis. Time dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and area under the curve (AUC) values within the follow-up time were calculated to evaluate the discriminatory ability of the model. All analyses were conducted using R version 4.4.2 (R foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Overall Patient Characteristic and Comparison between Hospitalization and Outpatient Groups

117 patients were first diagnosed as tuberculosis during the study period. Among 117 patients, 34 patients (29.1%) were hospitalized for any cause and 83 patients (70.9%) were treated at outpatient department. The overall patient characteristics and comparison between two groups are shown in

Table 1. Neutrophil was higher and ALT was lower in the hospitalization group (

p=0.033 and

p=0.022 )

3.2. Risk factors for hospitalization in tuberculosis patients

The results of Cox proportional hazards regression models are presented in

Table 2. In the univariable analysis, Total WBC, neutrophil and platelet had p values less than 0.05 and were entered in the multivariable analysis. In the multivariable analysis, neutrophil at the time of TB diagnosis was independently associated with hospitalization (Hazard ratio (HR), 1.6652; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.0389-2.6691,

p-value =0.034).

3.3. LASSO Cox regression

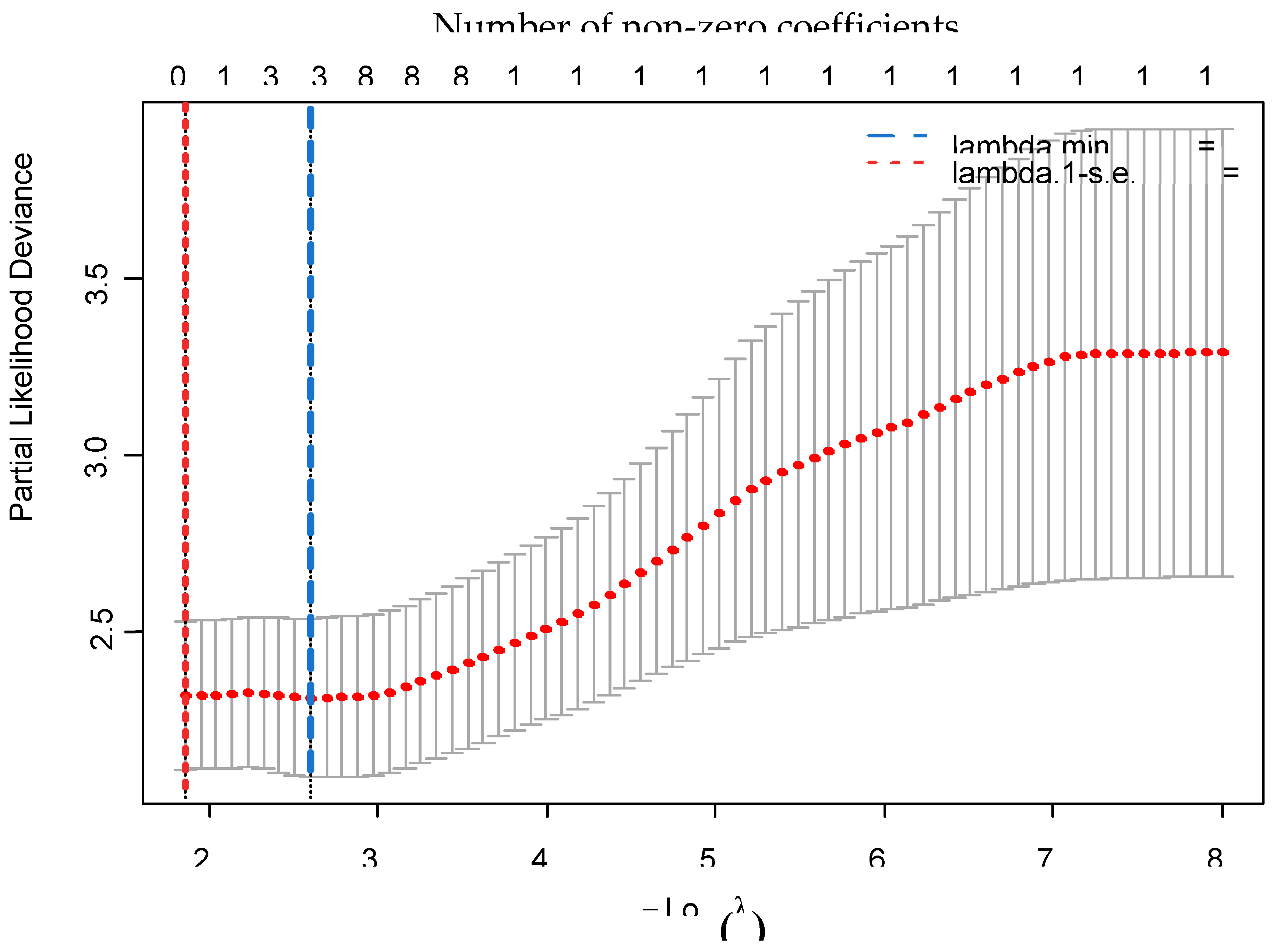

62 patients had at least one missing value in the variabels and were excluded from the anlaysis. The remaining 55 patients were included in the LASSO Cox regression. Among 55 patients. 20 patients were hospitalizaed and 35 patients were treated in the outpatient department. The plot of cross-validated partial likelihood deviance is presented in

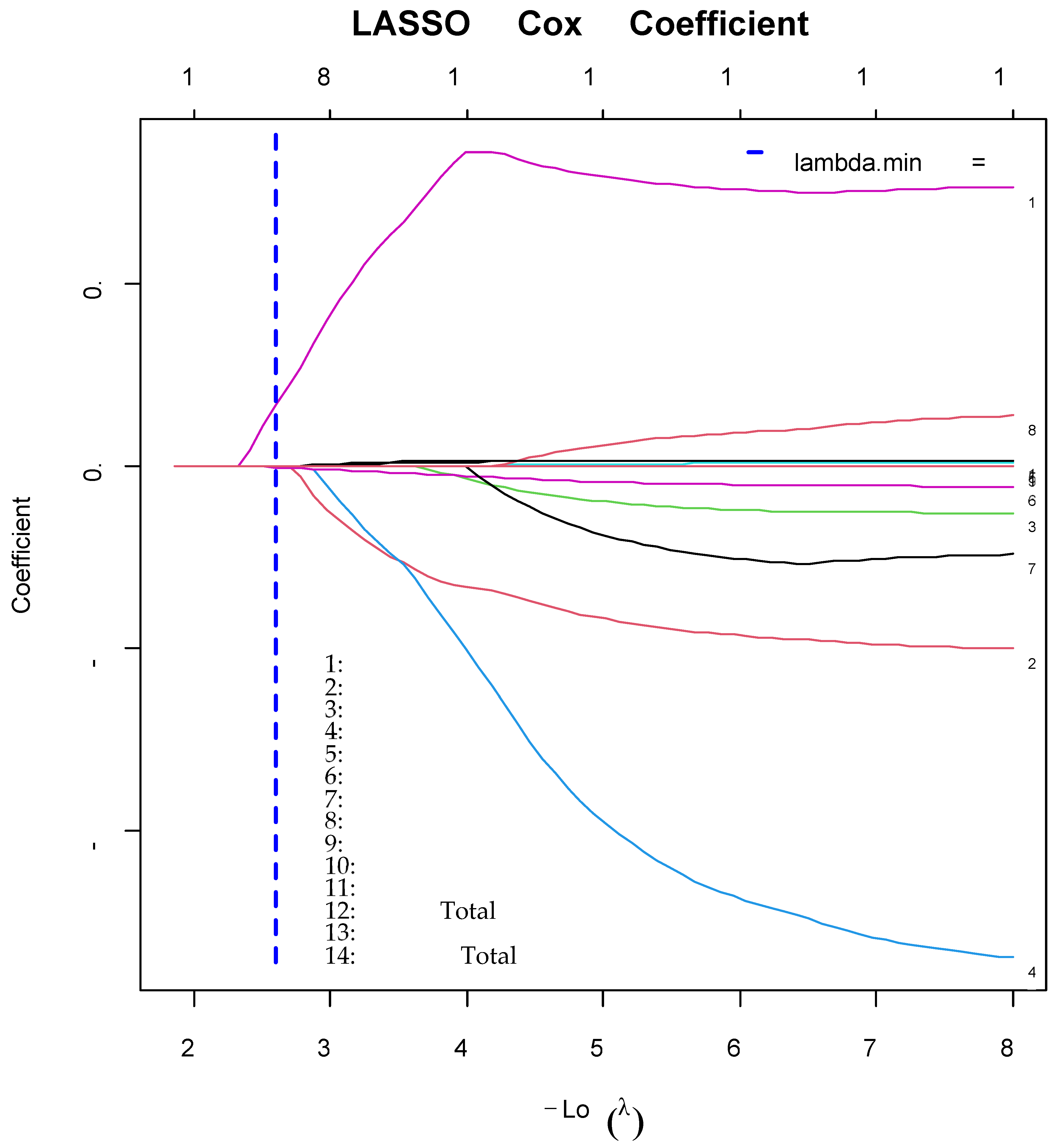

Figure 1. Two dotted vertical lines represent lambda.min and lambda.1-s.e. (standard error) The final model was selected based on lambda.min. Lambda min was 0.074, with -log (λ), 2.600. according to 5-fold cross-validation. LASSO coefficient profiles of the 14 variables are shown in

Figure 2. The vertical line was drawn at lambda.min which resulted in three nonzero coefficeients – neutrophils, ALT and total bilirubin. The C-index of the LASSO Cox regression model was 0.629 (95% CI : 0.489-0.765).

Tuning parameter (λ) selection used five-fold cross-validation. Three variables were selected at lambda.min. (At minimum criteria including neutrophils, ALT and total bilirubin). All coefficients were set to zero at 1-s.e. criteria. s.e.; standard error

A vertical line was drawn at lambda.min chosen via 5-fold cross-validation, where 3 coefficients were non-zero. WBC, white blood cell; AST, aspartate-aminotransferase; ALT, alanine-aminothransferase; CRP, C-reactive protein

3.4. Time-Dependent ROC curve Analysis

The results of time-dependent ROC of the LASSO Cox regression model are presented in

Figure 3. Neutrophils, ALT and total bilirubin were selected in the LASSO Cox regression model. AUC was 68.14 (95% CI : 52.17-84.11) at 49 days after diagnosis and 64.97 (95% CI: 48.66 – 81.28 ) at 175 days after diagnosis.

4. Discussion

Neutrophil was higher in the hospitalized group while ALT was higher in the outpatient group. Since ALT levels were within the normal range in both groups, the higher ALT observed in the outpatient group does not necessarily indicate impaired liver function. Previous study has shown that patients in the mortality group had lower hemoglobin and lymphocyte [

3]. Although, nutrition status was an important risk for mortality in the previous study [

4], albumin and total cholesterol was not statistically significant in our study. Serum albumin <3.0g/dL and serum cholesterol<90mg/dL were assigned as 1 point in the nutrition risk score [

5]. In our study, both the hospitalized group and outpatient groups had serum albumin level greater than 3.0g/dL and serum cholesterol levels above 90mg/dL, indicating that the study population was relatively well-nourished. This may explain why nutrition status was not statistically significant in the Cox regression model. Future studies with larger sample size are warranted.

TB is caused by

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Innate immune response system plays a crucial role in respiratory infection. Phagocytic cells such as neutrophils and macrophages are key components in innate immune response system [

13]. Macrophages interact with mycobacteria at the initial site of infection and signals from infected macrophages within the granuloma recruits neutrophils [

14].The abundance of neutrophils in the blood is associated with bacillary load and poor disease outcome [

15,

16]. Neutrophils act through phagocytosis and release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).

Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces NETs. Previous study demonstrated that NETs may be associated with lung tissue damage among TB patients [

17]. Neutrophils mode of action can lead to long-term pulmonary sequelae [

16]. Since the recommended TB treatment duration in the ROK is 180 days [

18], outcome was defined as admission within 180 days. The effects of neutrophils on hospitalization might be attributable to lung tissue damage and subsequent long-term pulmonary sequelae.

Total number of neutrophils, ALT and total bilirubin measured at diagnosis were selected in the LASSO Cox regression model. LASSO Cox regression model applies a penalty function and performs variable selection [

12]. Because our sample size was relatively small compared with the number of variables, overfitting was a concern. The LASSO mitigates this risk by shrinking coefficients [

19]. Therefore, we used LASSO Cox regression model in our study. Lambda.min is the optimal value of λ with the minimum mean cross-validated error and lambda.1-s.e. is the largest λ value such that the cross-validation error is within 1 s.e. of the minimum [

20]. Since lambda.1-s.e. did not select any variables, we used lambda.min in our study. The final Cox model with the selected variable, neutrophils, ALT and total bilirubin demonstrated a discriminative ability with a C-index of 0.629 in our study. This result shows the value of neutrophils, ALT and total bilirubin measured at the time of diagnosis in predicting hospitalization in patients with TB. Time-dependent ROC analysis revealed that the predictive performance of the model improved over time. These results suggest that the neutrophils, ALT and total bilirubin at baseline has increasing prognostic value for hospitalization as time progresses. The model’s performance became more robust in the later follow-up period. This finding may reflect the evolving clinical course of TB and the growing influence of baseline inflammatory markers on long-term outcomes. Our study provides insights into the value of laboratory data at the time of diagnosis in predicting admission during TB treatment. However, there are several limitations in our study. First, this was a single center study and the sample size was relatively small. Second, the follow-up period may not fully capture long-term hospitalization risks associated with TB. Third, variables such as treatment adherence, socioeconomic status, comorbidities and other laboratory values were not included in this study due to data limitations. Fourth, because performance was estimated from OOF cross-validation, external validation is required. Further studies with larger number of samples and more clinical variables are warranted.

5. Conclusion

Our study indicated that baseline neutrophil count was independently associated with an increased risk of hospitalization in patients with TB, as shown in the multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression. LASSO Cox regression model selected three variables at the time of diagnosis – neutrophils, total bilirubin and ALT using the value of λ with the minimum mean cross-validated error. This model demonstrated discriminative performance with a C-index of 0.629. Time dependent ROC analysis showed AUC of 64.97 at 175 days after diagnosis. Early identification and closer monitoring on patients with high neutrophil counts, ALT and total bilirubin at the time of TB diagnosis could improve clinical outcomes and optimize healthcare resource allocation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.B.K. and S.-S.H..; methodology, O.B.K. and Y.H..; software, O.B.K..; validation, D.H.M., W.J.K. and S.-J.L..; formal analysis, O.B.K..; investigation, Y.H. and D.H.M.; resources, W.J.K..; data curation, S.-S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, O.B.K..; writing—review and editing, O.B.K., Y.H., M.D.H., and S.-S.H.; visualization, O.B.K..; supervision, S.-S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by 2025 Kangwon National University Hospital Grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kangwon National University Hospital (KNUH-2025-07-016).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TB |

Tuberculosis |

| ROK |

Republic of Korea |

| ICU |

Intensive care unit |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| BUN |

Blood urea nitrogen |

| CRP |

C-reactive protein |

| OOF |

Out-of-fold |

| LASSO |

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator |

| Afp-HCC |

Alpha-fetoprotein-negative hepatocellular carcinoma |

| CDW |

Clinical data warehouse |

| WBC |

White blood cell |

| AST |

Aspartate-amonitransferase |

| ALT |

Alanin-aminotransferase |

| C-index |

Concordance index |

| ROC |

Receiver operating characteristic |

| AUC |

Area under the curve |

| NET |

Neutrophil extracellular traps |

References

- Yang, H.; Ruan, X.; Li, W.; Xiong, J.; Zheng, Y. Global, regional, and national burden of tuberculosis and attributable risk factors for 204 countries and territories, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Diseases 2021 study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3111.

- Lee, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Park, Y.-J.; Jeong, H.; Kim, H.; Shin, J.; Ahn, H.; Lee, E.; Jang, A. Tuberculosis notification status in the Republic of Korea, 2024. 2025.

- Kim, C.W.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.N.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, M.K.; Lee, J.H.; Shin, K.C.; Yong, S.J.; Lee, W.Y. Risk factors related with mortality in patient with pulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2012, 73, 38-47.

- Kwon, O.B.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, E.G.; Park, Y.; Jung, S.S.; Kim, J.W.; Oh, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S., et al. Nutrition Status and Comorbidities Are Important Factors Associated With Mortality During Anti-Tuberculosis Treatment. J Korean Med Sci 2025, 40.

- Kim, D.K.; Kim, H.J.; Kwon, S.Y.; Yoon, H.I.; Lee, C.T.; Kim, Y.W.; Chung, H.S.; Han, S.K.; Shim, Y.S.; Lee, J.H. Nutritional deficit as a negative prognostic factor in patients with miliary tuberculosis. Eur Respir J 2008, 32, 1031-1036.

- Carr, B.Z.; Briganti, E.M.; Musemburi, J.; Jenkin, G.A.; Denholm, J.T. Effect of chronic kidney disease on all-cause mortality in tuberculosis disease: an Australian cohort study. BMC Infectious Diseases 2022, 22, 116.

- Pradhan, R.R.; Yadav, A.K. Incidence, Clinical Features, Associated Factors and Outcomes of Intensive Phase Antituberculosis Drug Induced Liver Injury Among Patients With Tuberculosis at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Nepal: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. Health Science Reports 2025, 8, e70686.

- Mishra, S.; Gala, J.; Chacko, J. Factors Affecting Mortality in Critically Ill Patients With Tuberculosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med 2024, 52, e304-e313.

- Tibshirani, R. The lasso method for variable selection in the Cox model. Stat Med 1997, 16, 385-395.

- Liu, G.-M.; Zeng, H.-D.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Xu, J.-W. Identification of a six-gene signature predicting overall survival for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell International 2019, 19, 138.

- Li, Y.; Ge, D.; Gu, J.; Xu, F.; Zhu, Q.; Lu, C. A large cohort study identifying a novel prognosis prediction model for lung adenocarcinoma through machine learning strategies. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 886.

- Zhou, D.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Yan, F.; Wang, P.; Yan, H.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Z. A prognostic nomogram based on LASSO Cox regression in patients with alpha-fetoprotein-negative hepatocellular carcinoma following non-surgical therapy. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 246.

- O'Garra, A.; Redford, P.S.; McNab, F.W.; Bloom, C.I.; Wilkinson, R.J.; Berry, M.P. The immune response in tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol 2013, 31, 475-527.

- Yang, C.T.; Cambier, C.J.; Davis, J.M.; Hall, C.J.; Crosier, P.S.; Ramakrishnan, L. Neutrophils exert protection in the early tuberculous granuloma by oxidative killing of mycobacteria phagocytosed from infected macrophages. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 12, 301-312.

- Borkute, R.R.; Woelke, S.; Pei, G.; Dorhoi, A. Neutrophils in Tuberculosis: Cell Biology, Cellular Networking and Multitasking in Host Defense. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22.

- Muefong, C.N.; Sutherland, J.S. Neutrophils in Tuberculosis-Associated Inflammation and Lung Pathology. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, Volume 11 - 2020.

- de Melo, M.G.M.; Mesquita, E.D.D.; Oliveira, M.M.; da Silva-Monteiro, C.; Silveira, A.K.A.; Malaquias, T.S.; Dutra, T.C.P.; Galliez, R.M.; Kritski, A.L.; Silva, E.C., et al. Imbalance of NET and Alpha-1-Antitrypsin in Tuberculosis Patients Is Related With Hyper Inflammation and Severe Lung Tissue Damage Frontiers in immunology [Online], 2018, p. 3147. PubMed.

- 2024; 18. Korean Guidelines For Tuberculosis Fifth Edition, 2024, Joint Committee for the Revision of Korean Guidelines for Tuberculosis, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Ye, D.; Chi, P. A LASSO-based survival prediction model for patients with synchronous colorectal carcinomas based on SEER. Transl Cancer Res 2022, 11, 2795-2809.

- Waldmann, P.; Mészáros, G.; Gredler, B.; Fuerst, C.; Sölkner, J. Evaluation of the lasso and the elastic net in genome-wide association studies. Front Genet 2013, 4, 270.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).