Submitted:

19 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

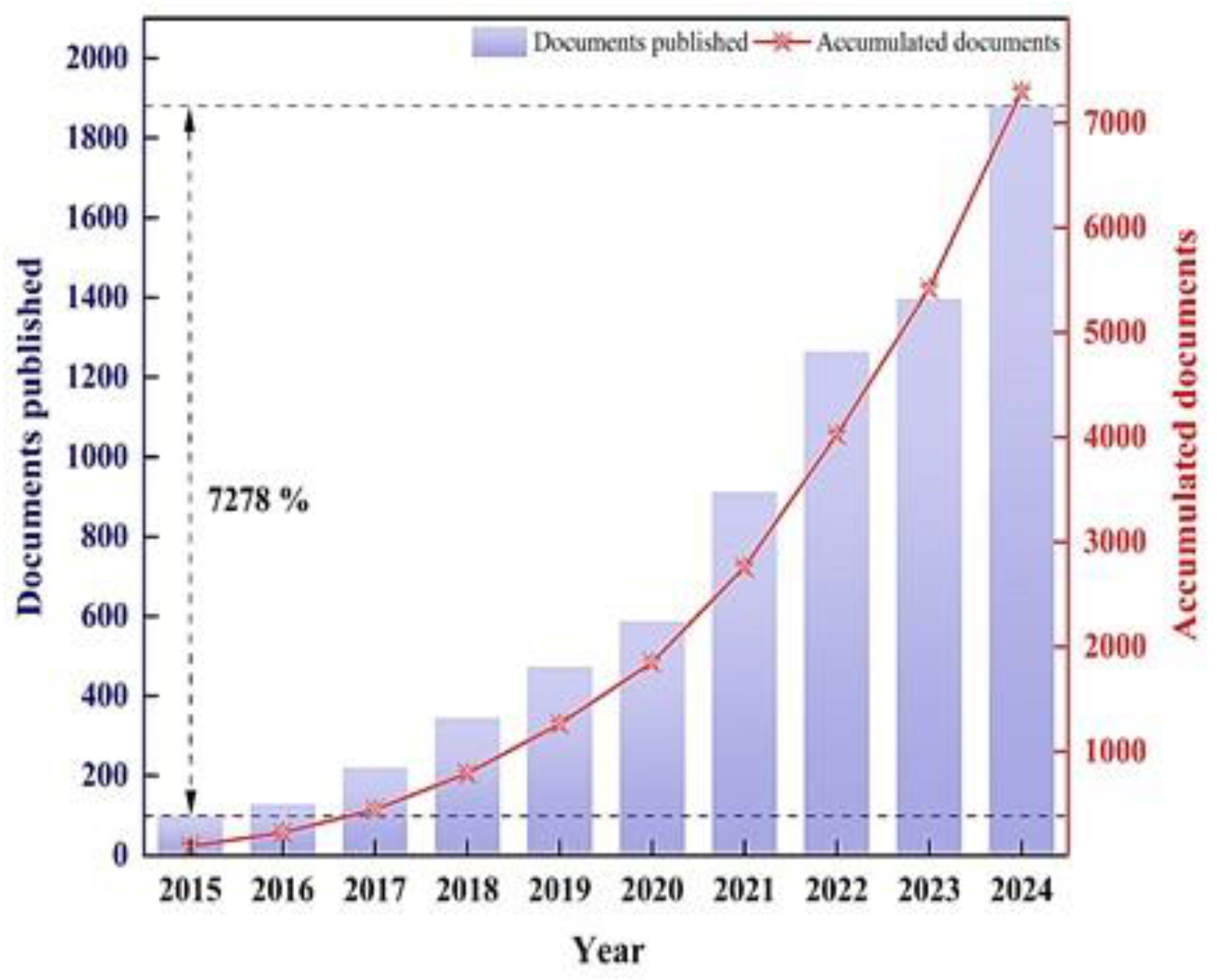

1. Introduction

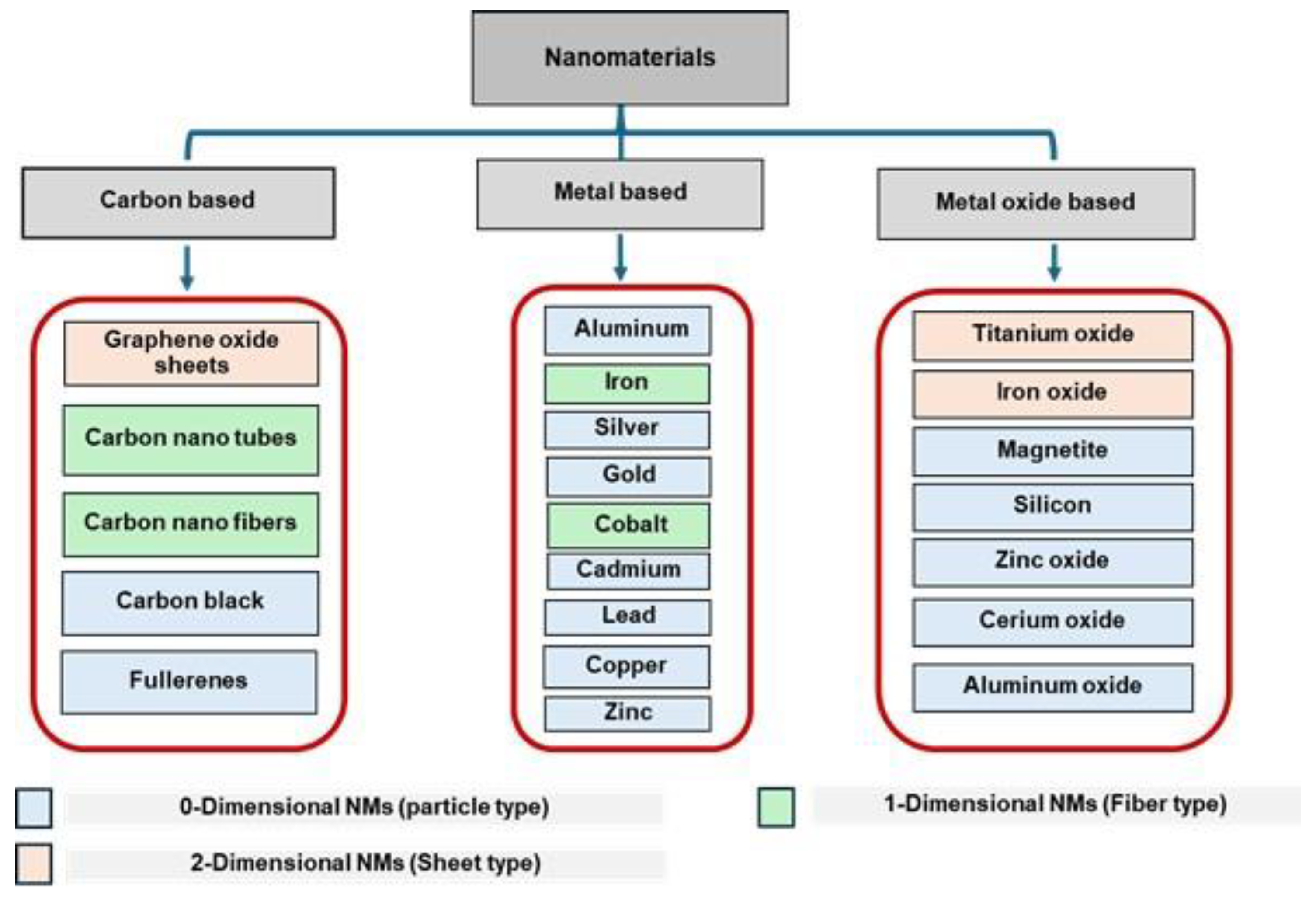

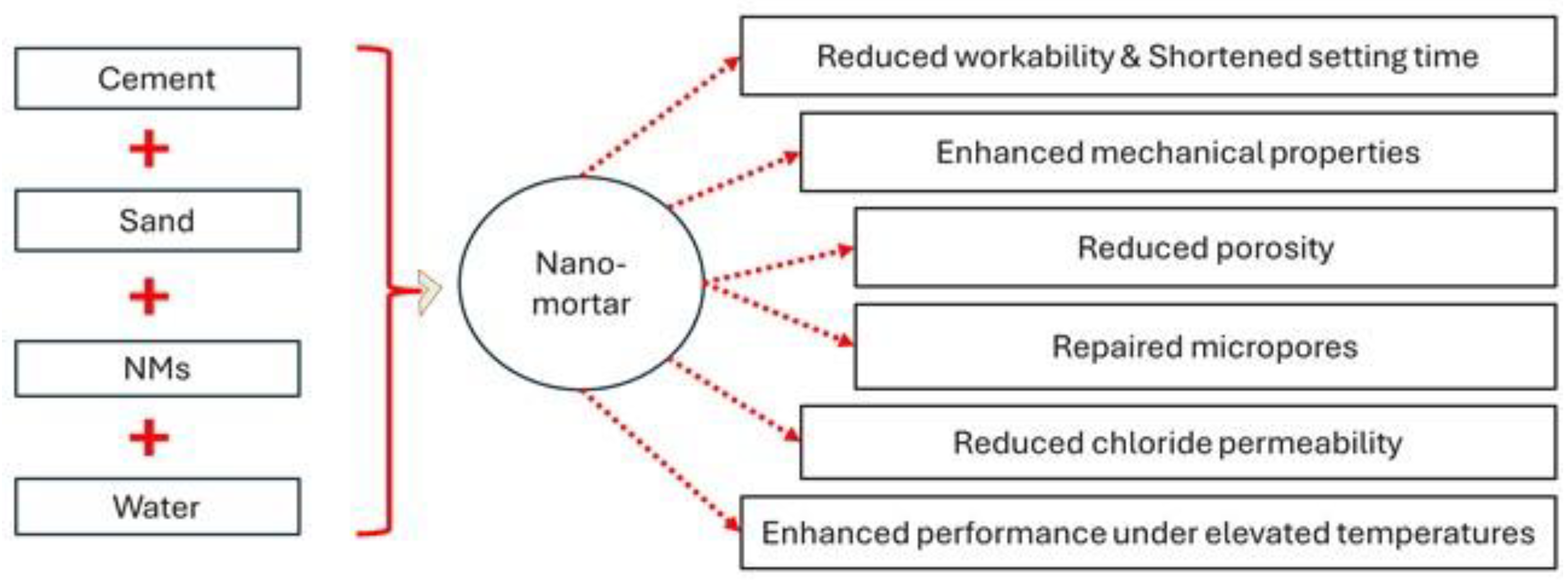

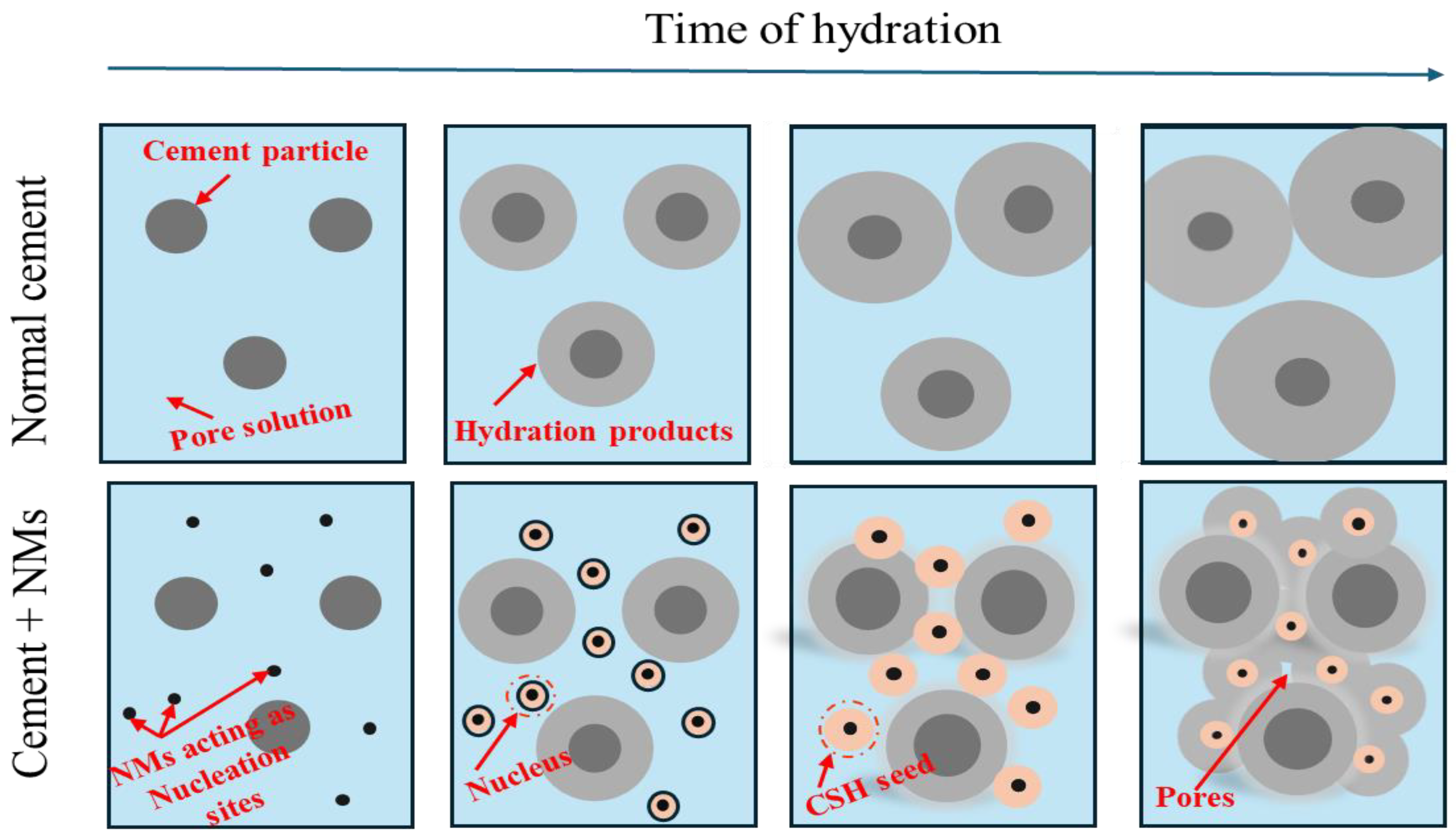

2. Nanotechnology in Cementitious Composites: Influence on Hydration Kinetics, Mechanical Strength and Microstructure

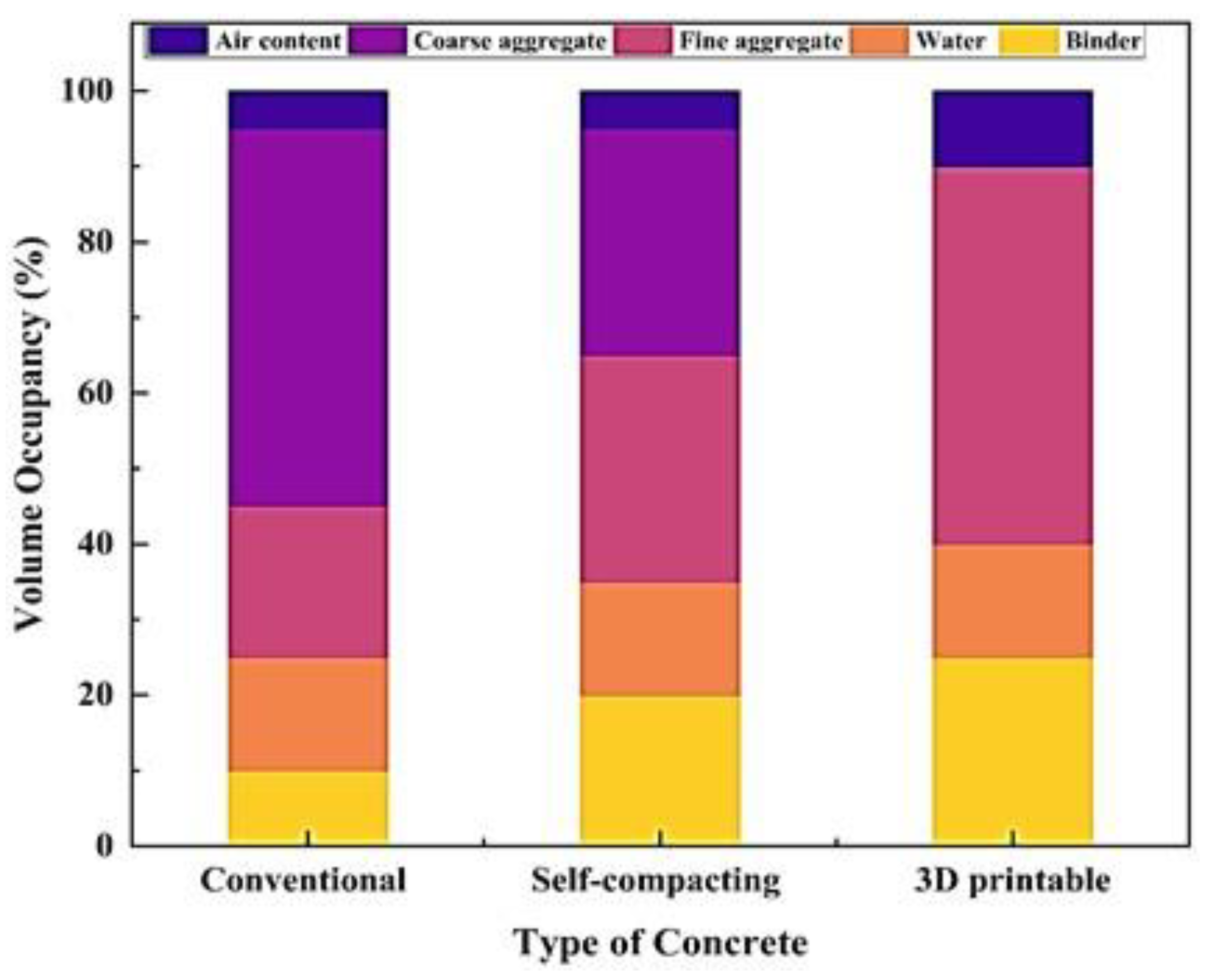

3. Fresh and Hardened Properties of 3DPC and the Role of NMs

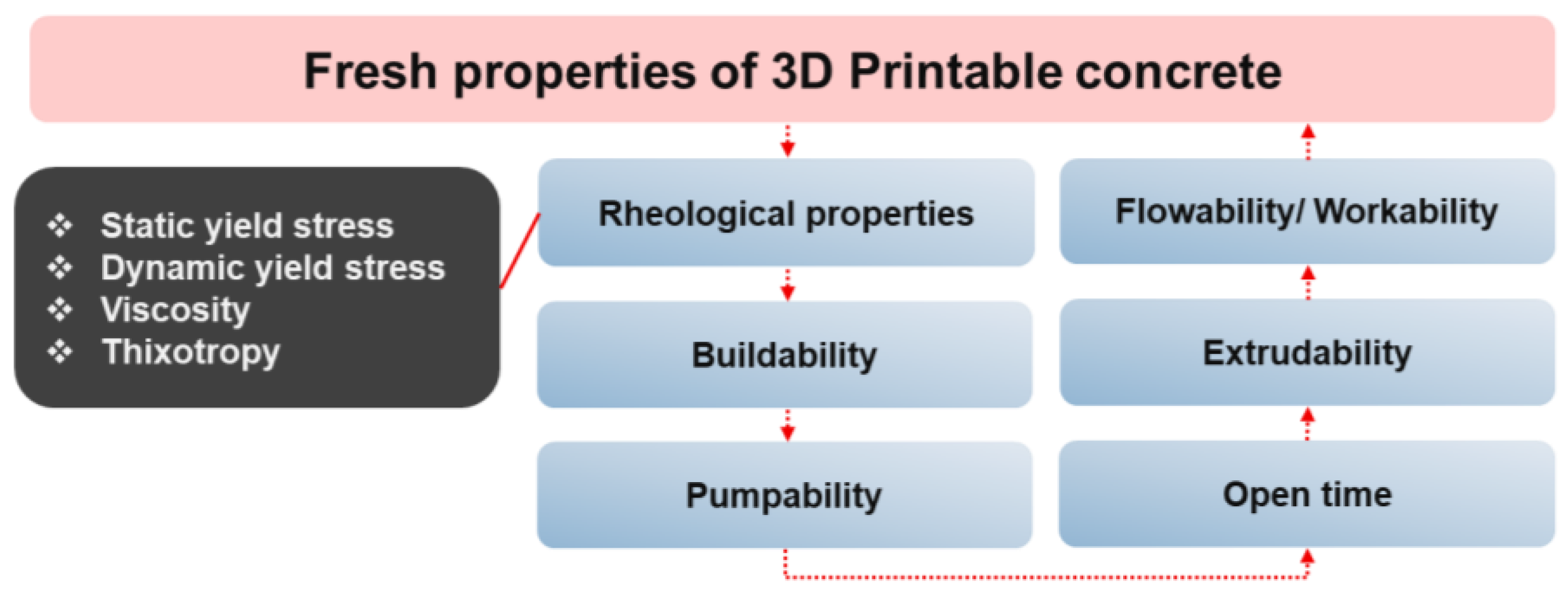

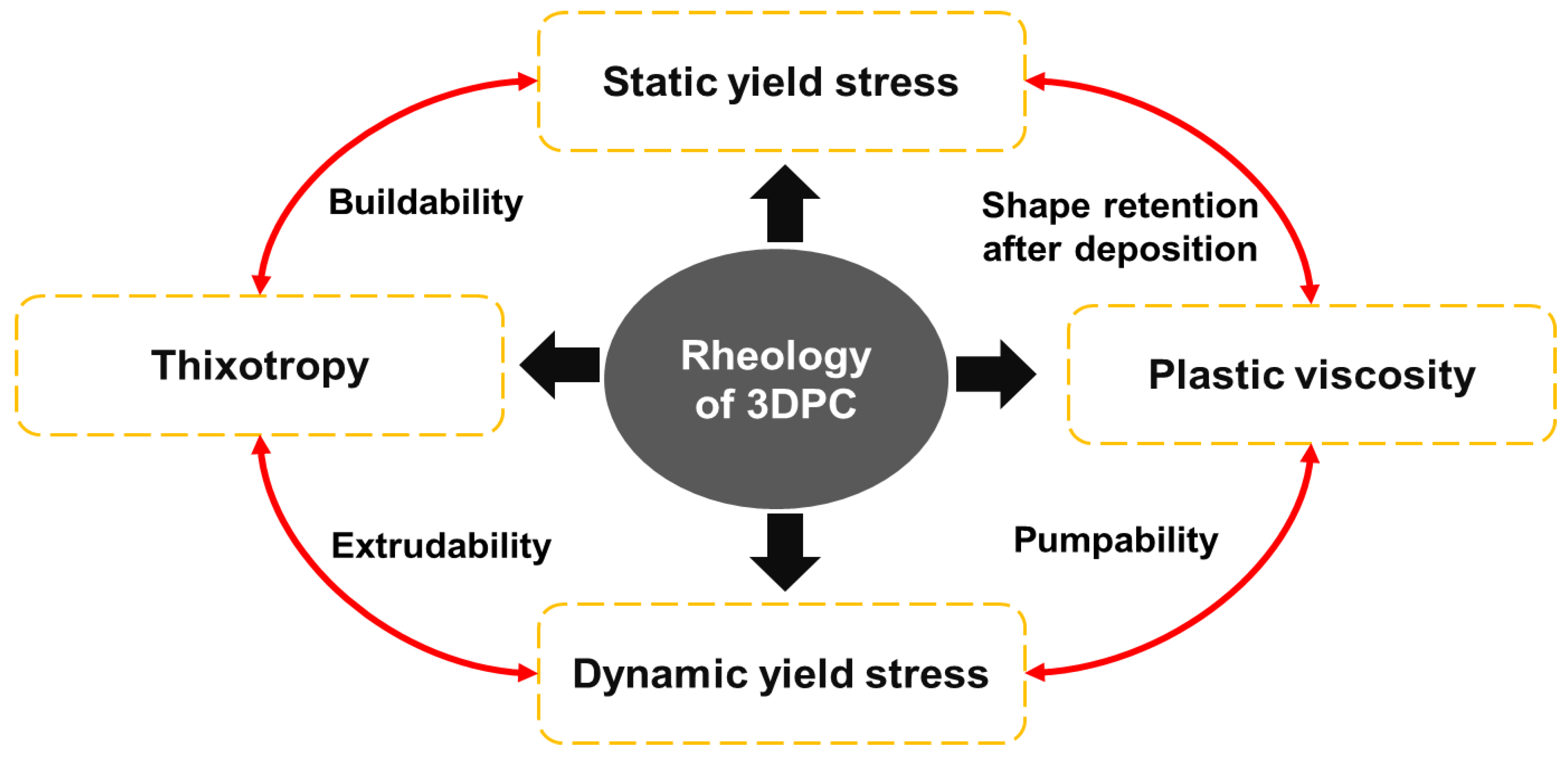

3.1. Fresh Properties

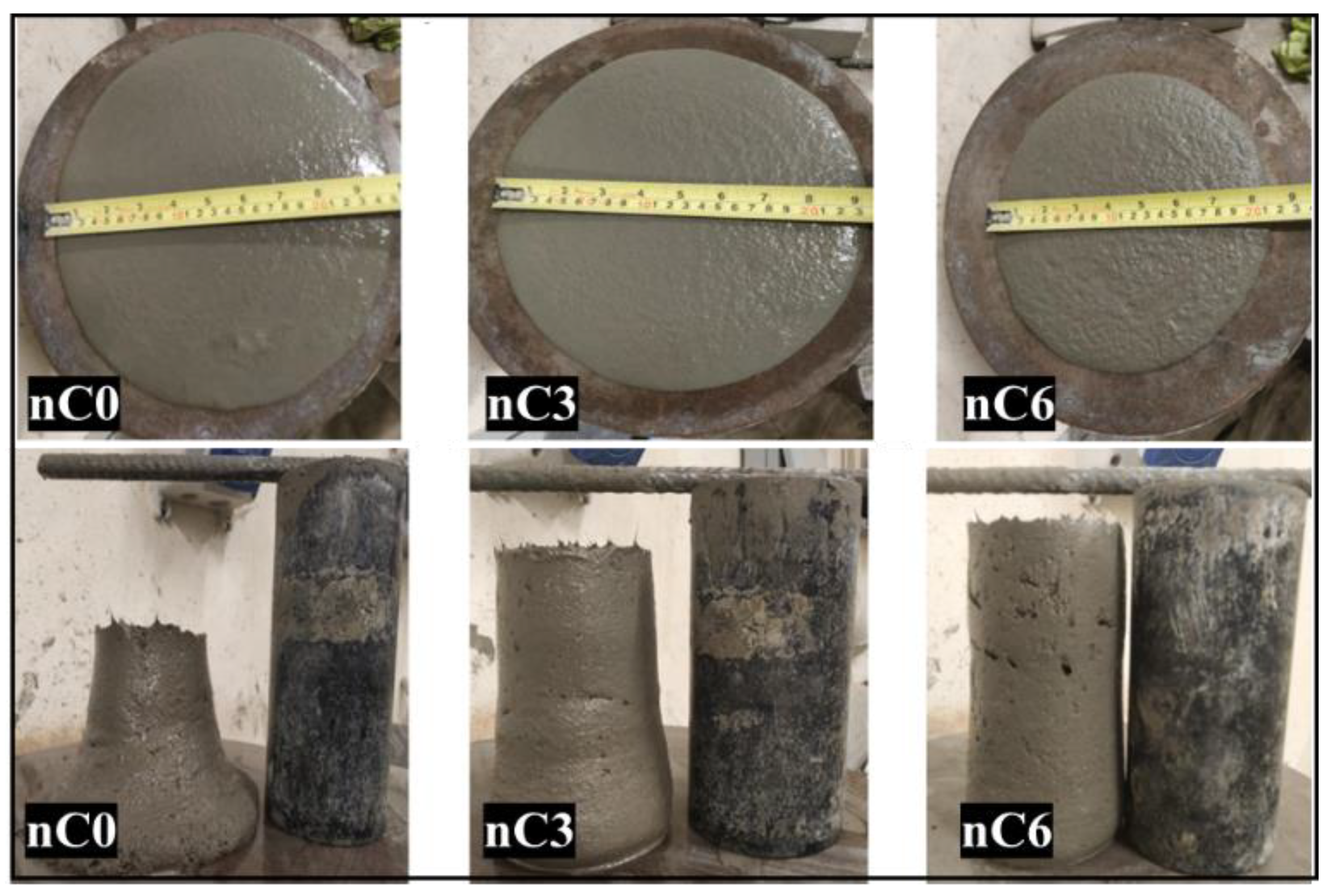

3.1.1. Flowability

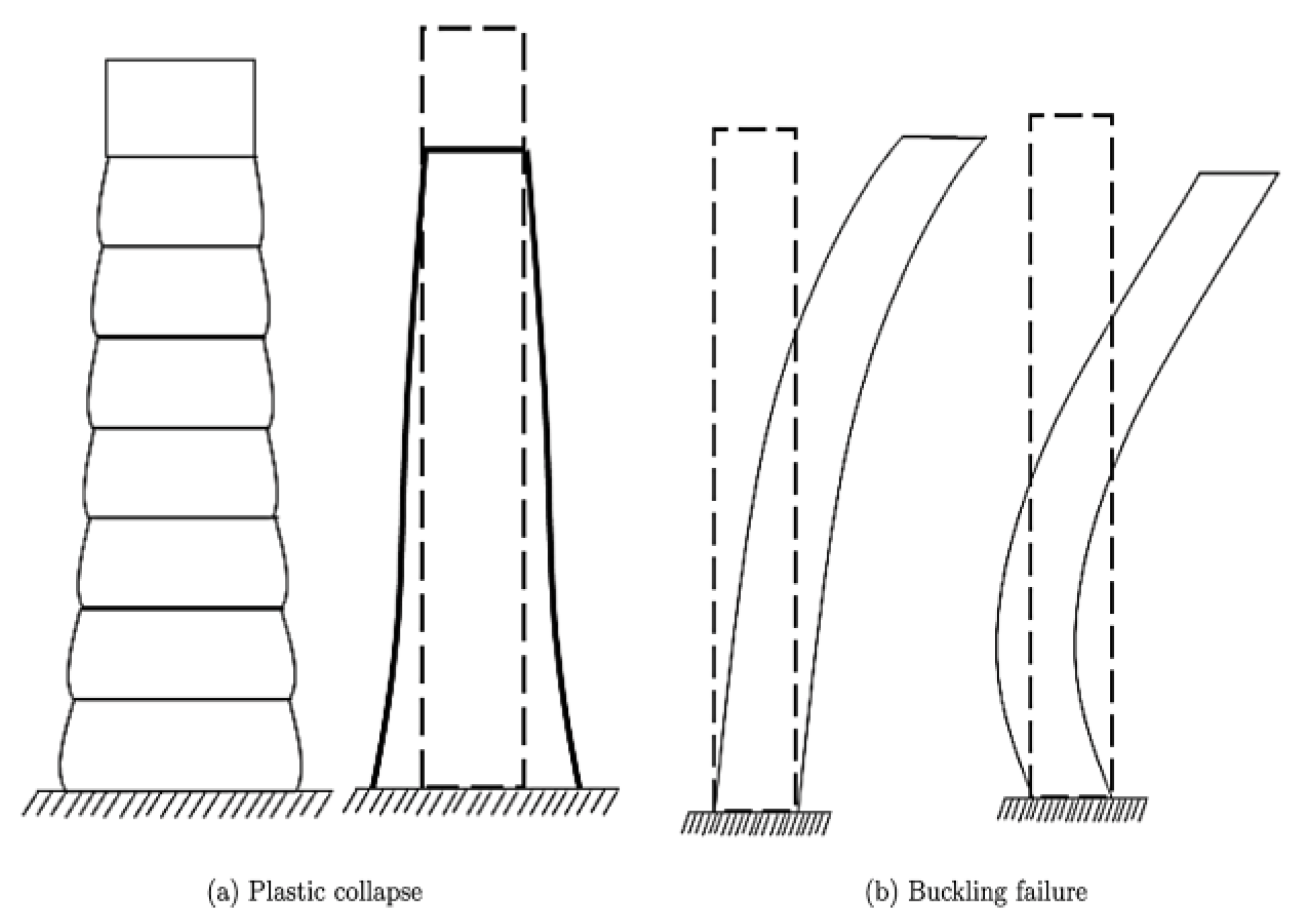

3.1.2. Buildability

3.1.3. Extrudability

3.1.4. Pumpability

3.1.5. Open Time

3.1.6. Rheological Properties

3.2. Mechanical Properties

4. Influence of NMs on Fresh and Hardened Properties of 3DPC

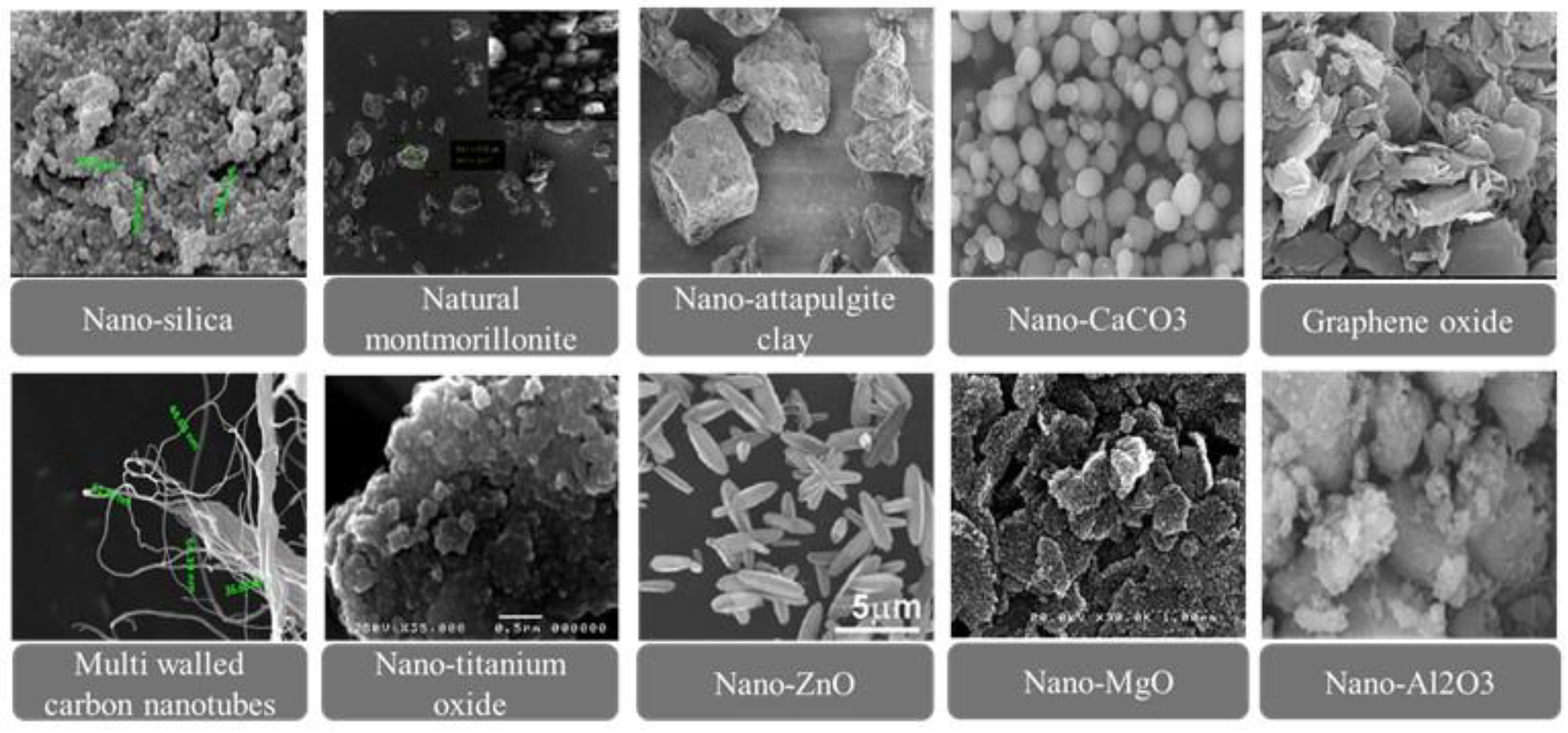

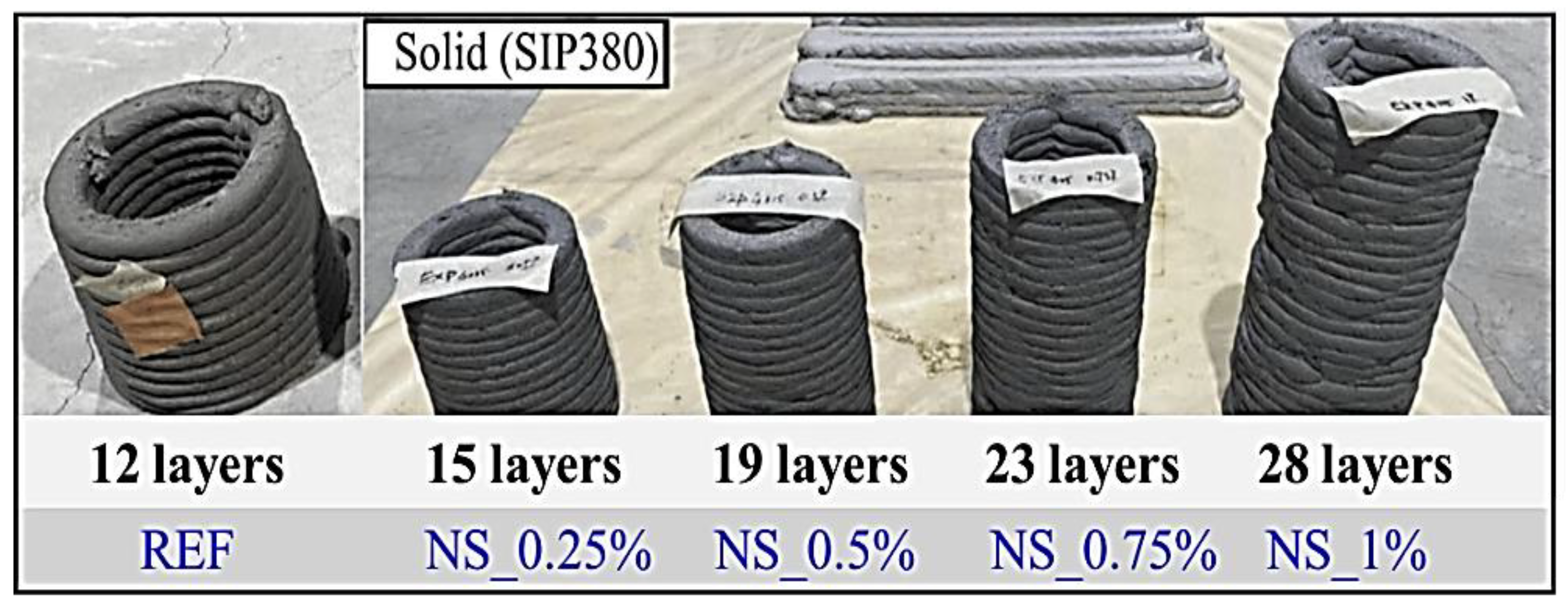

4.1. Nano Silica

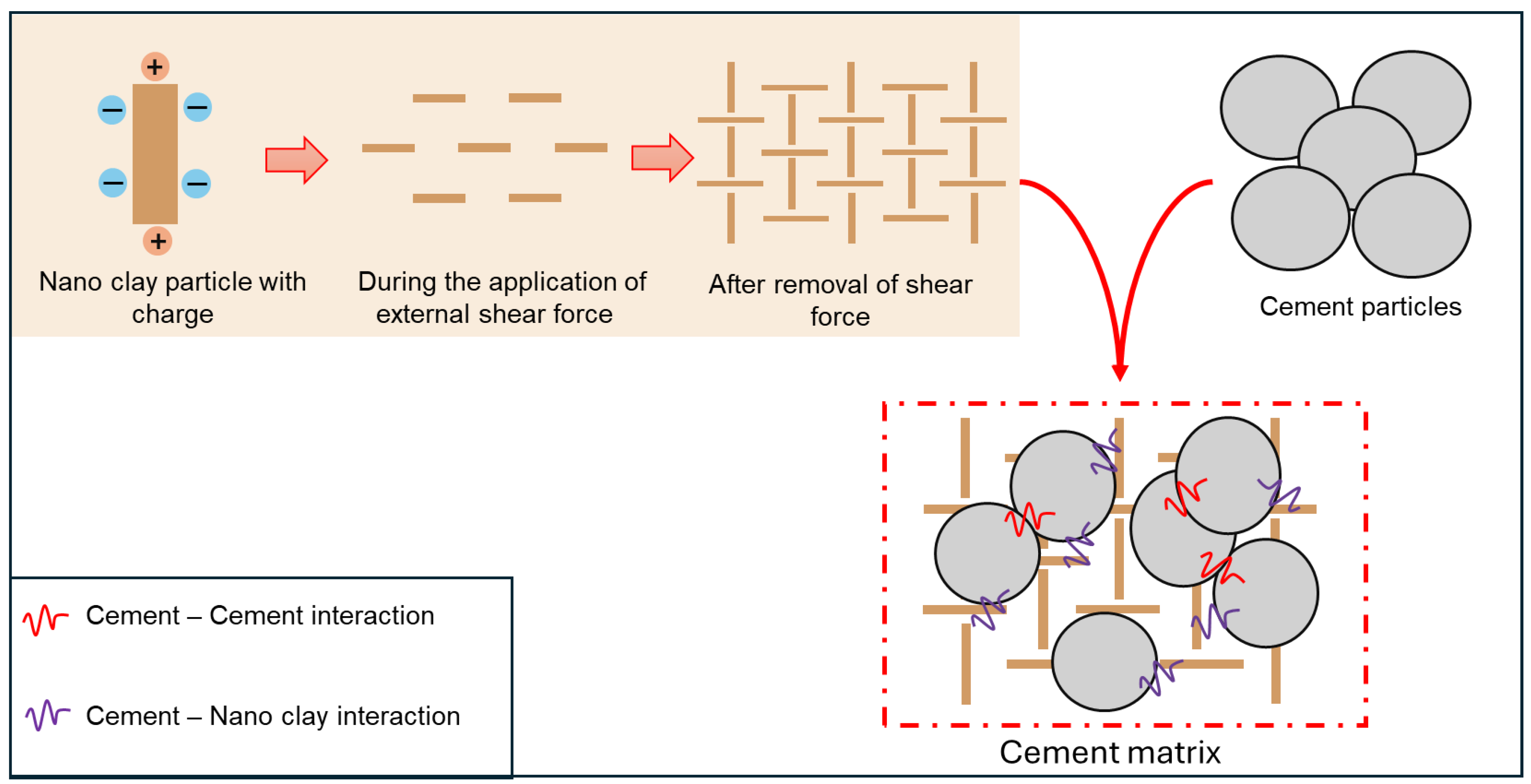

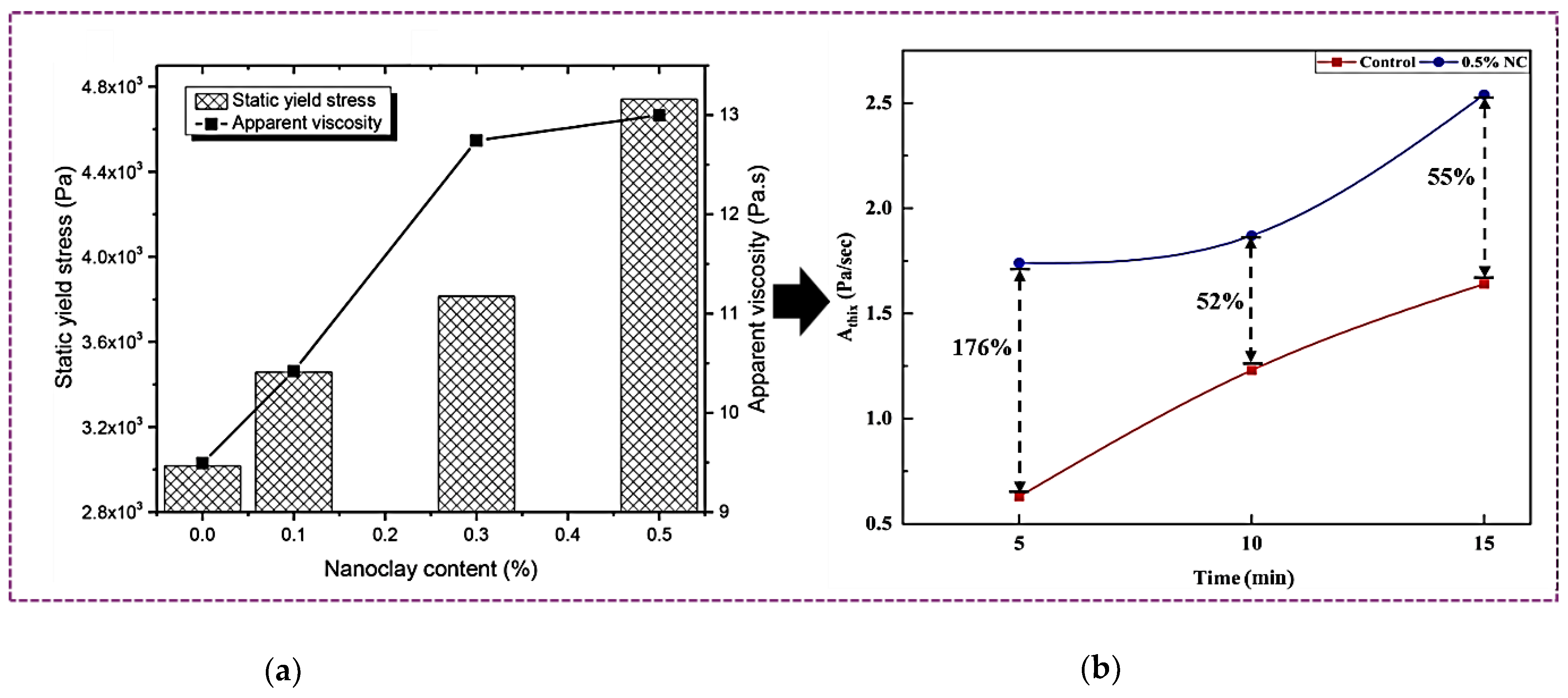

4.2. Nano Clay

4.3. Nano CaCo3

4.4. Carbon Based Nanomaterials

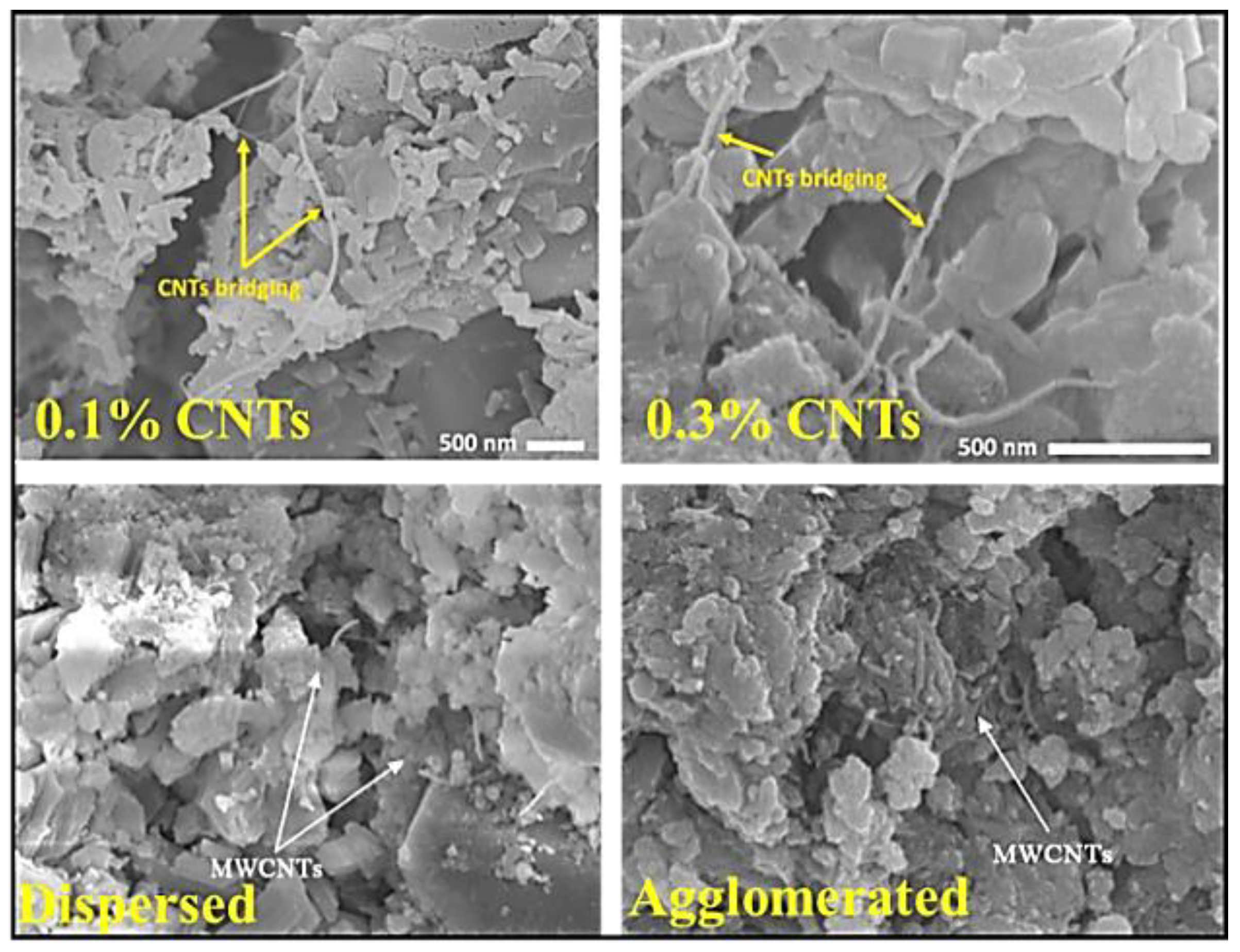

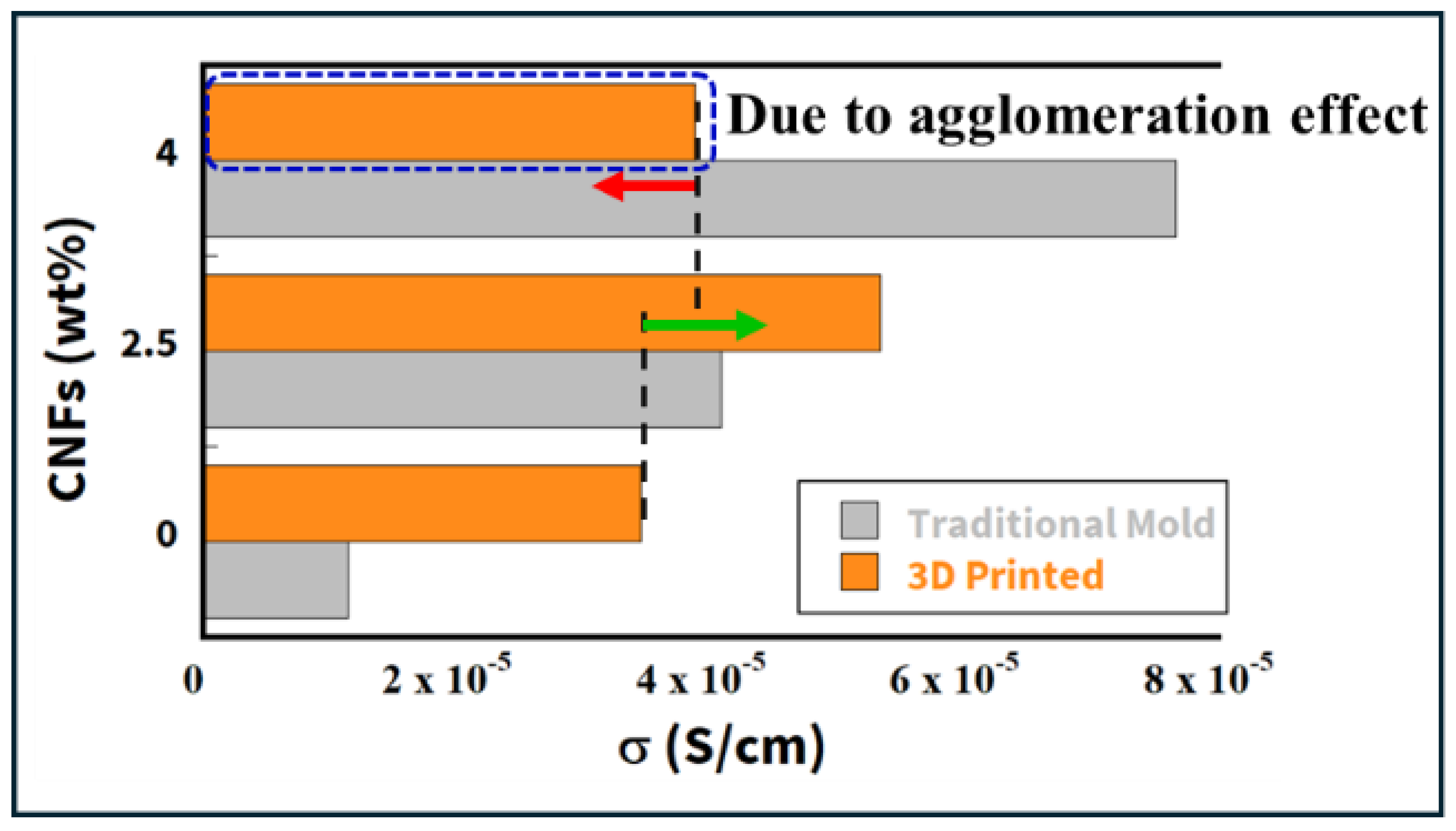

4.4.1. Carbon Nanotubes and Fibers

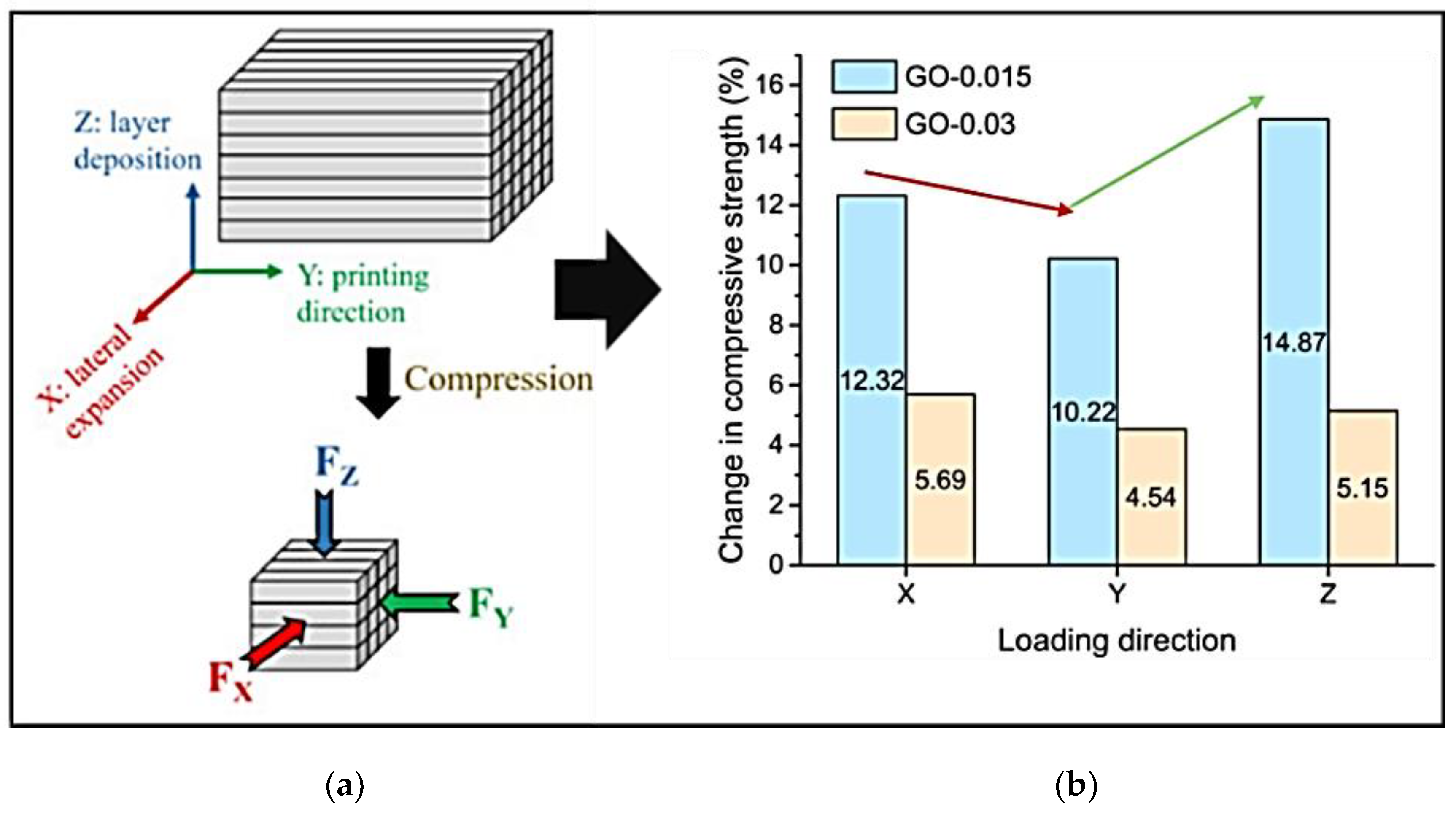

4.4.2. Nano Graphene Oxide

4.5. Nano TiO₂

| S.No |

Nano material |

Additional materials |

Dosage of NMs (% of mass of cement/ binder) |

Inferences | References |

| 1 | Graphene | - | 0.5-2 | Pore-filling clustering at higher dosages leads to an improvement in tensile strength. Enhancement of mechanical strength and microstructure upon the addition of silica fume. |

[145] |

| 2 | Titanium dioxide | Polypropylene (PP) fibres | 0-0.03 | Increased static yield stress, lower dynamic yield stress, and hydration acceleration. Void filling improved density and mechanical strength while reducing porosity by over 40%. |

[144] |

| 3 | Calcium carbonate | – | 0-3 | Lower compressive strength in 3D-printed cement pastes, particularly along the printing direction, is attributed to higher porosity and a weaker ITZ. Early age strength gain occurs due to the filler effect and an accelerated hydration reaction, resulting in reduced anisotropy. |

[146] |

| 4 | Calcium carbonate | Modified PP fiber | 0-4 |

Improves buildability, shape stability, and mechanical strength; reduces flowability and setting time; increases density via surface area and filling effect. Higher dose caused particle agglomeration, reducing efficiency. Modified PP fibers provided skeletal support. |

[147] |

| 5 | Silica | - | 0-2 | Flexural and compressive strengths at an early age were enhanced due to accelerated hydration and pore filling. The excessive addition of NS caused agglomeration, which may have a negative impact on extrudability and printability. Improved interfacial transition zone and dense microstructure. |

[148] |

| 6 | Silica | - | 0-1 | Improvements in rheological properties, thickening of mixes, reduction of setting time, enhancement of buildability and negative impact on pumpability. Densification of the microstructure increases the risk of carbonation at higher dosages. |

[117] |

| 7 | Silica | PP fibers | 0-1 |

NS enhanced the hydrophilicity of PP fibers, that improved cement bonding and mortar packing, led to smoother printability Double doped mix enhanced buildability around 1.25 times. Combined of NS and PP reduced anisotropy. Limited availability of water may reduce NS nucleation, which has a negative impact on compressive strength. |

[149] |

| 8 | Clay | - | 0.4% | Declination of Pumpability, higher shape retention, buildability and thixotropy. Enhancement of mechanical strength. |

[150] |

| 9 | Clay | - | 0.5- 4 | Enhancements in rheological properties include a static yield stress improvement of up to 15 times and a near doubling of viscosity, as well as improvements in shape stability and buildability. The acceleration phase has resulted in increased heat, leading to accelerated C-S-H growth and nucleation, as well as improved matrix stiffening. |

[151] |

| 10 | Clay | Carbohydrate complex chemical-based admixture | 0-0.6 | Increased static yield stress and dynamic yield stress, reduced viscosity, and enhanced elasticity were observed, while VMA effects were minor, except at higher attapulgite doses. Lower static yield stress led to collapse or mixed elastic-plastic failures. |

[152] |

| 11 | Clay | Fly ash | Montmorillonite 0-1 Sepiolite 0-1 |

Enhanced thixotropy, dynamic yield stress, shape retention, and buildability result in a stiff mix at a higher dosage. Fly ash improves thixotropy and structural build-up but slightly reduces recovery and natural tendencies. |

[153] |

| 12 | Clay | Gypsum | 0-0.4 | Enlarged thixotropic area. Enhanced early and overall strength through nucleation, accelerated C-S-H formation, and reduced porosity. Combined materials led to a reduction in flowability, early hydration, refinement of pore structure, optimised rheological behaviour, and volume instability. |

[154] |

| 13 | Clay | Fly ash | 0.5-2.5 | Reduced slump, elevated yield stresses, and increased plastic viscosity. NC increased air entrainment because the fine particles absorb lubricated water. Trapping air led to a reduction in compressive strength and stiffness. Fly ash decreased slump and compressive strength at later ages while enhancing hydration, improving microstructure, and reducing induced bleeding through better particle packing and dispersion. |

[155] |

5. Performance of NMs in Development of Sustainable 3DPC

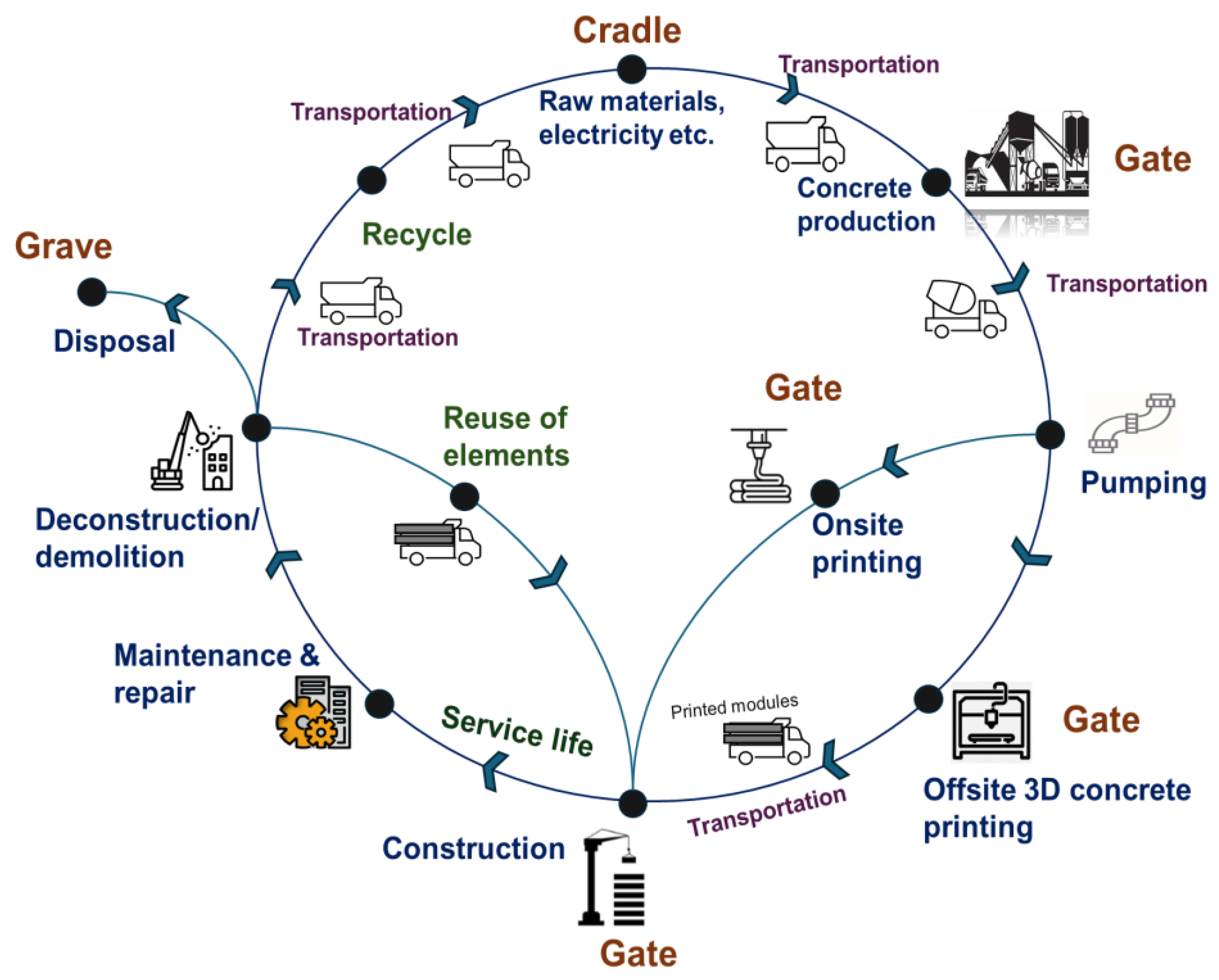

5.1. Sustainability in 3DPC

5.2. Sustainability Challenges and Economic Implications of Nanomaterial Incorporation in 3DPC

| Sl. No |

Nanomaterial |

Purity (%) |

Size (nm) |

~Surface area (m2/g) |

Approximate price Per kg (USD) |

Dosage considered (% by binder mass) |

Mass of NMs per m³ (kg) | Additional cost per m³ (USD) |

| 1 | Montmorillonite | ~99.9 | <500 | 180-220 | 58.61 | 0.5 | 4.5 | 263.75 |

| 2 | Silicon Dioxide | >99.9 | <100 | 120 | 57.44 | 0.5 | 4.5 | 258.48 |

| 3 | Graphene oxide | ~99 | 0.8-2 (thickness) D50- 10μm |

120 | 339.95 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 91.79 |

| 4 | Titanium Dioxide | >99.9 | <100 | 150 | 57.44 | 0.75 | 6.75 | 387.72 |

| 5 | Multiwalled carbon nanotubes | ~99% | 10-20 (diameter), ~10μm (length) |

230 | 375.12 | 0.2 | 1.8 | 675.216 |

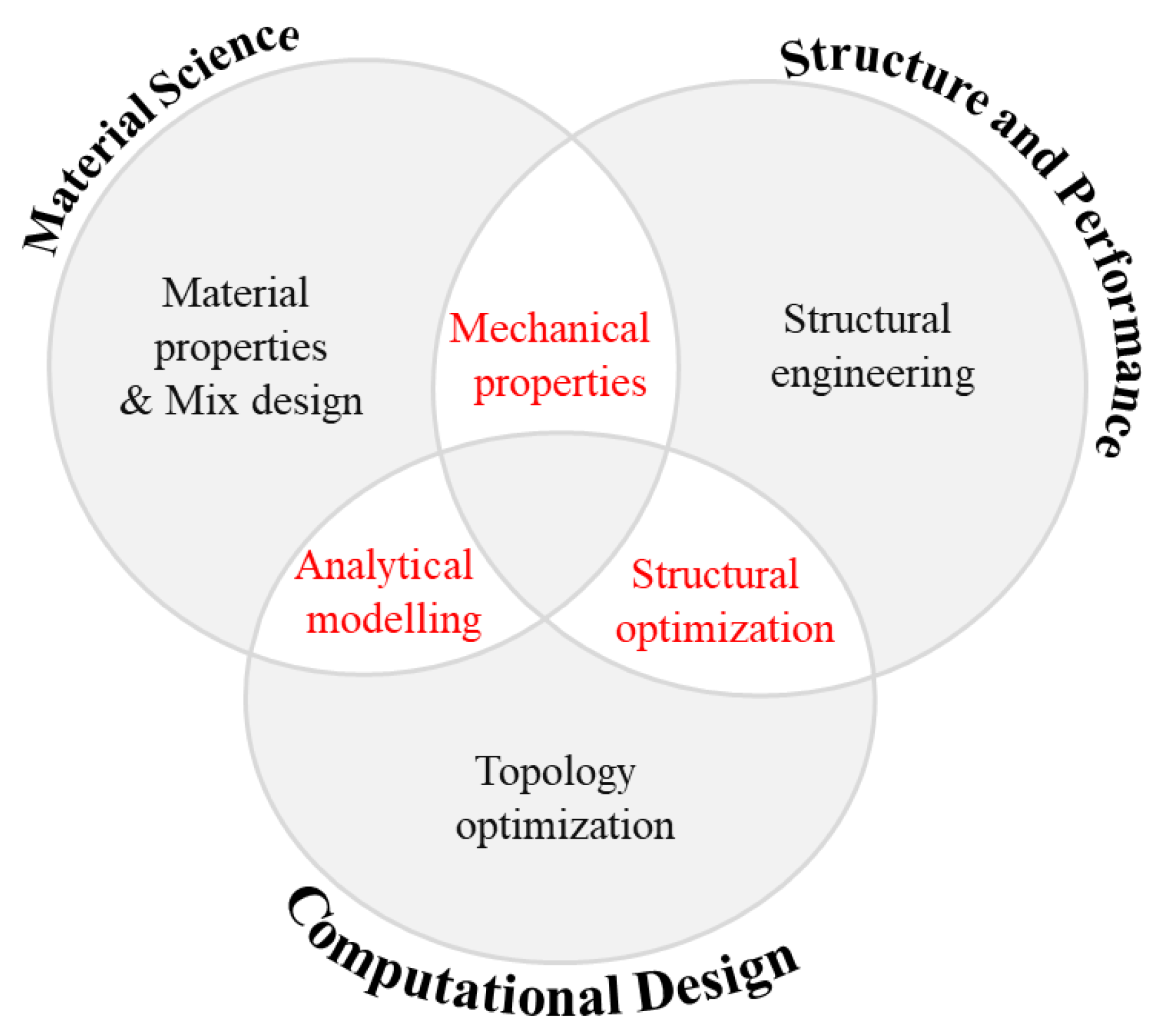

5.3. Role of Structural Optimisation for Sustainability

6. Conclusions

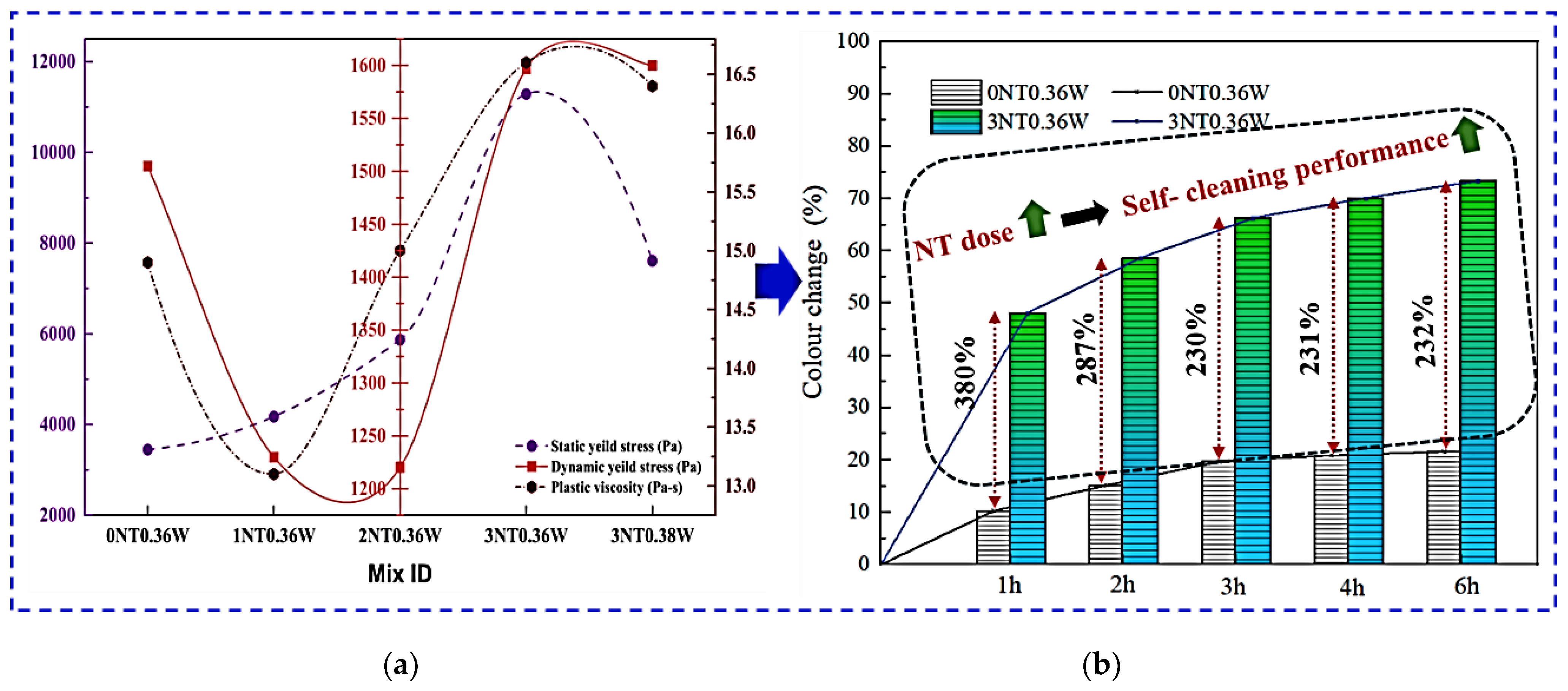

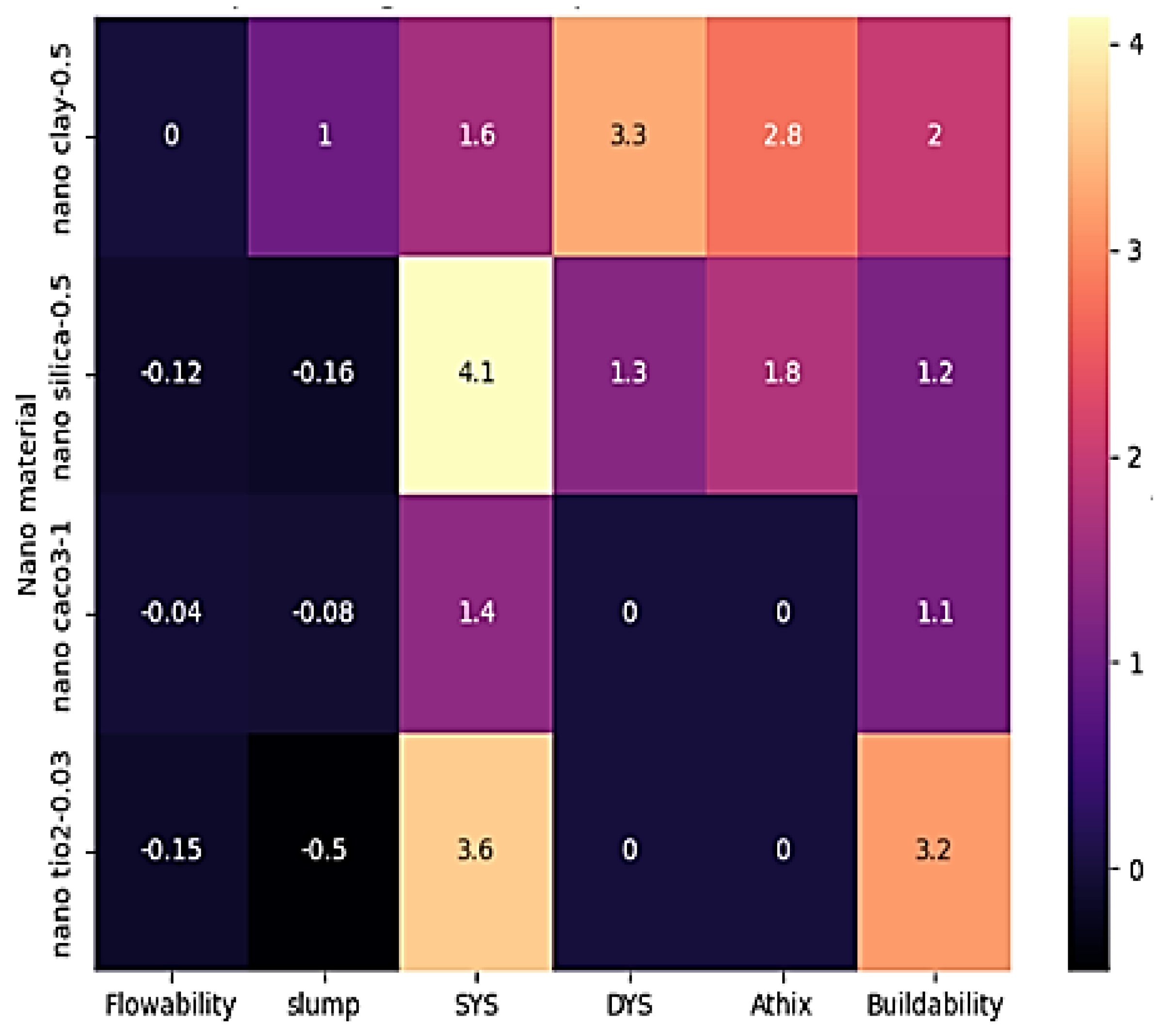

- Most of the NMs significantly enhance the rheological properties of the printable concrete when used in a limited dosage. Specifically, NMs such as NC (0.5%), NS (0.5%), NCa (1%), and NT (0.03%) have been shown to enhance the cohesiveness and yield stress of the mix, thereby improving shape retention and buildability post-extrusion. Notably, the addition of NS resulted in a substantial increase of approximately 410% in static yield stress, followed by a 360% improvement.

- At optimal dosages, NMs reduced flowability by 10–15% and slump by up to 50%. This reduction is attributed to their high surface area and particle reactivity, which increase water demand and thicken the mix. Consequently, higher superplasticiser dosages are required to restore workability. The stiffening effect impairs pumpability and extrusion, underscoring a trade-off between buildability and fresh-state performance.

- NC enhances green strength and early stiffness through its flocculation-promoting capacity, acting as a viscosity-modifying agent, while NS accelerates hydration kinetics and improves structural buildup and shape retention. An excessive dosage of NMs leads to agglomeration and pumpability issues, often resulting in unprintable mixes. Almost all NMs have a negative impact on the flowability of the blend due to their larger surface area.

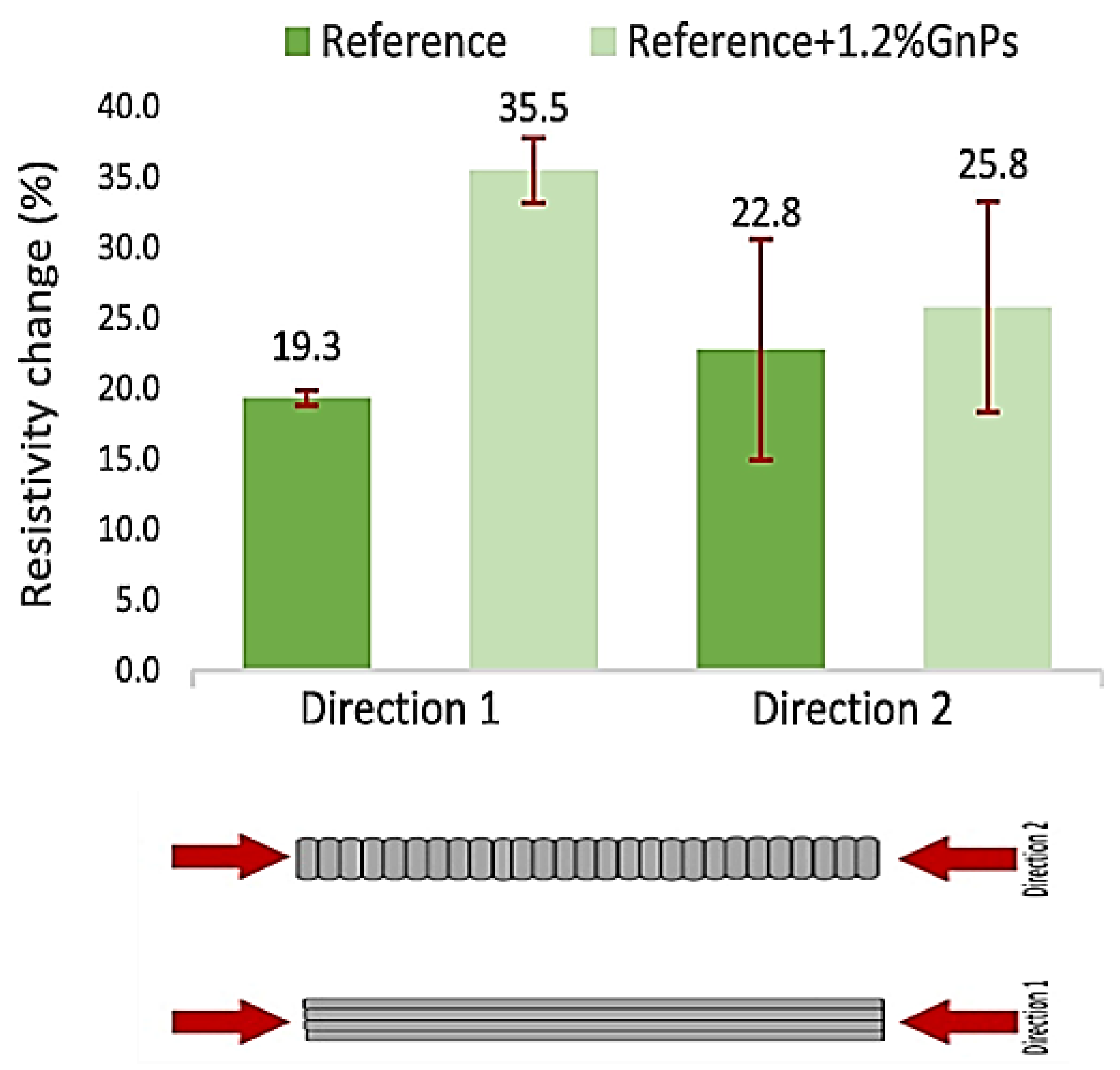

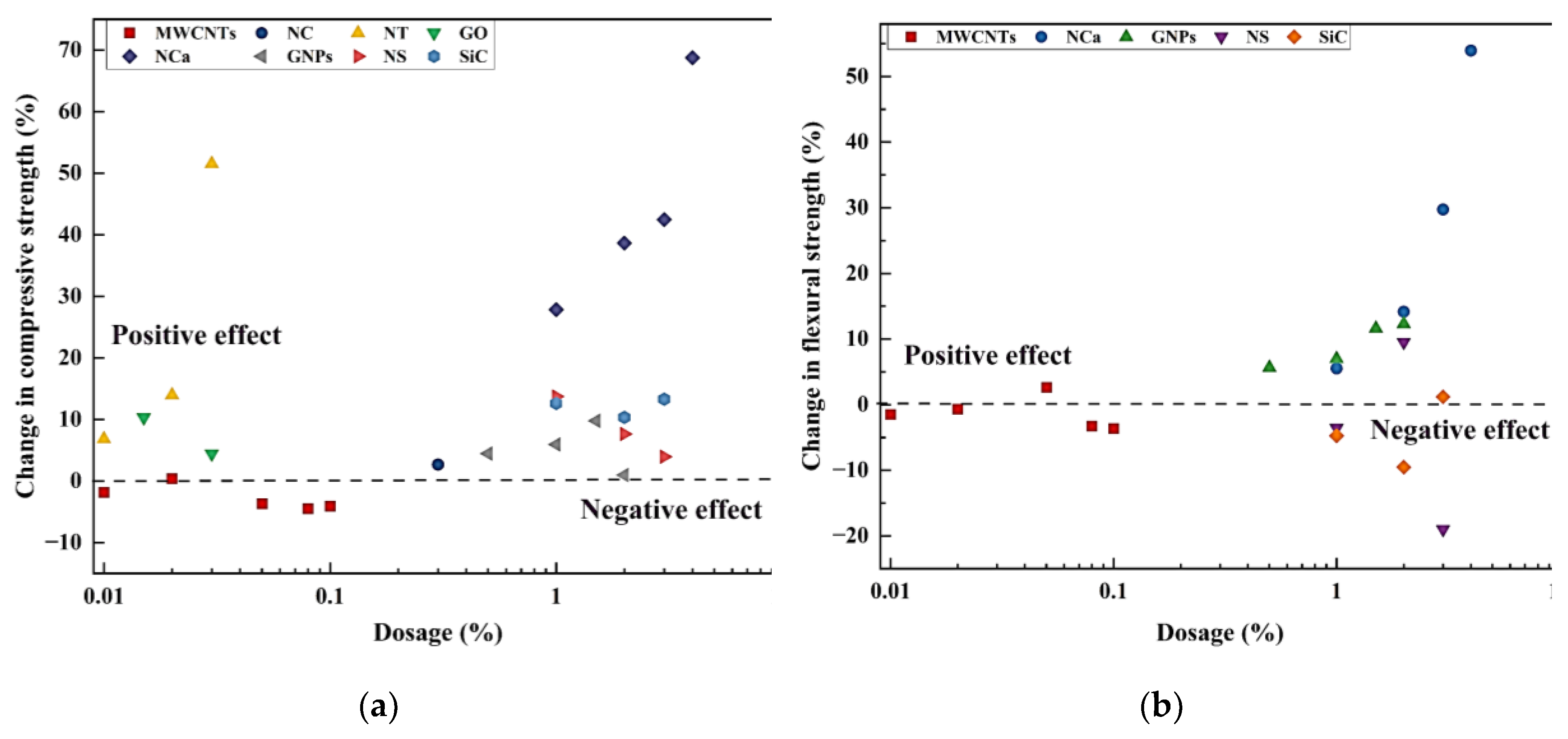

- The addition of NMs into 3D printable concrete significantly enhances mechanical performance, with optimal dosages (~0.05–1.0 wt.%) yielding up to a 70% improvement in compressive strength and a 55% improvement in flexural strength. NMs like GO and GNPs offer high efficiency at low dosages (~0.1–1 wt.%), while mineral-based NMs (NS, NCa) provide moderate, consistent improvements between ~20 to 35%. This enhancement is attributed to improved nucleation, densification of the matrix, and effective stress transfer. Beyond optimal dosage, the disruption of agglomeration and hydration kinetics degrades performance. Thus, NM selection and dosage tuning are critical to maximising reinforcement efficiency in printable cementitious systems.

- Incorporating NMs improves mechanical properties of concrete through microstructural densification, pore filling, and accelerated cement hydration. Few carbon-based NMs form crack-bridging networks that enhance interlayer bonding and reduce anisotropy. However, anisotropic weaknesses persist in specific configurations due to uneven material distribution and weak interlayer bonding, necessitating further studies.

- NMs can be embedded into printable concrete to impart unique functionalities. For instance, adding NT enables concrete to clean itself by breaking down over 70% of surface pollutants within 6 hours of exposure to light, while GNPs enhance its self-sensing ability.

- Dispersion of NMs is a significant challenge. Improper dispersion leads to agglomeration, which negatively impacts both rheological and mechanical properties. Techniques such as ultrasonication can improve uniform distribution, but they also increase production costs and energy demands. Enhanced strategies for effective NM incorporation are needed to minimise these drawbacks.

- The synergistic use of NMs with SCMs and fibres provide enhanced fresh and hardened properties; in combination with superplasticisers, this reduces water demand. However, excessive fibre dosages lead to blockages and inefficient printing.

- Although NMs improve concrete properties, their production is energy-intensive, resulting in high environmental footprints. Topology optimisation techniques can further enhance sustainability by minimising material usage without compromising structural integrity in 3DPC.

7. Knowledge Gaps in NM-Modified 3DPC

8. Future Research Directions

- Develop predictive multiscale frameworks that integrate NM dispersion dynamics, hydration kinetics, and rheological evolution with process parameters (e.g., extrusion rate, interlayer time, build height). Such models must be supported by scalable dispersion methods (high-shear, ultrasonic, and surface functionalisation) to ensure uniform distribution and reliable structural build-up.

- Incorporate NM-specific mechanical and durability datasets into structural design by embedding mechanical and durability properties into topology optimisation and anisotropy-aware computational models, enabling lightweight, resource-efficient, and performance-driven 3D printed structures.

- Advance sustainability assessments through refined LCA frameworks that capture service-life extension due to NM integration, and end-of-life recovery pathways such as recycling or carbonation.

- Formulate dedicated test protocols for 3DPC that measure buildability, open time, interlayer adhesion, and anisotropic properties, addressing the limitations of current cement-based standards.

- Evolve design codes and guidelines toward performance-based criteria that explicitly account for digital fabrication processes, unconventional reinforcement layouts, and the durability enhancements achieved through NM integration.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3DPC | Three-Dimensional Printing Concrete |

| AMC | Additive Manufacturing Concrete |

| C-S-H | Calcium Silicate Hydrate |

| CNT | Carbon Nanotube |

| GGBS | Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag |

| GNPs | Graphene Nanoparticles |

| GO | Graphene Oxide |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| MWCNTs | Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| NC | Nano Clay |

| NCa | Nano Calcium Carbonate |

| NMs | Nanomaterials |

| NS | Nano Silica |

| NT | Nano Titanium-dioxide |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SCMs | Supplementary Cementitious Materials |

| VMA | Viscosity Modifying Agent |

References

- Lim, S.; Buswell, R.; Le, T.; Austin, S.; Gibb, A.; Thorpe, T. Developments in construction-scale additive manufacturing processes. Autom. Constr. 2012, 21, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schutter, G.; Lesage, K.; Mechtcherine, V.; Nerella, V.N.; Habert, G.; Agusti-Juan, I. Vision of 3D printing with concrete — Technical, economic and environmental potentials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 112, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Koç, M.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Sustainability assessment, potentials and challenges of 3D printed concrete structures: A systematic review for built environmental applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batikha, M.; Jotangia, R.; Baaj, M.Y.; Mousleh, I. 3D concrete printing for sustainable and economical construction: A comparative study. Autom. Constr. 2022, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Hou, J.; Ge, M. Research Progress and Trend Analysis of Concrete 3D Printing Technology Based on CiteSpace. Buildings 2024, 14, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayna, T.; Striukova, L. From rapid prototyping to home fabrication: How 3D printing is changing business model innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 102, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qutaifi, S.; Nazari, A.; Bagheri, A. Mechanical properties of layered geopolymer structures applicable in concrete 3D-printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 176, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.; Paul, S.C.; Mohamed, N.A.N.; Tay, Y.W.D.; Tan, M.J. Measurement of tensile bond strength of 3D printed geopolymer mortar. Measurement 2018, 113, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, C.; Duballet, R.; Roux, P.; Gaudillière, N.; Dirrenberger, J.; Morel, P. Large-scale 3D printing of ultra-high performance concrete – a new processing route for architects and builders. Mater. Des. 2016, 100, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Marchment, J.G. Sanjayan, B. Nematollahi, M. Xia, Interlayer Strength of 3D Printed Concrete, in: 3D Concrete Printing Technology, Elsevier, 2019: pp. 241–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815481-6.00012-9.

- Paul, S.C.; van Zijl, G.P.; Tan, M.J.; Gibson, I. A review of 3D concrete printing systems and materials properties: current status and future research prospects. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2018, 24, 784–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, B.; Xia, M.; Sanjayan, J. Current Progress of 3D Concrete Printing Technologies. 34th International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, TaiwanDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 260–267.

- Khoshnevis, B.; Bukkapatnam, S.; Kwon, H.; Saito, J. Experimental investigation of contour crafting using ceramics materials. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2001, 7, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Xia, B. Nematollahi, J.G. Sanjayan, Development of Powder-Based 3D Concrete Printing Using Geopolymers, in: 3D Concrete Printing Technology, Elsevier, 2019: pp. 223–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815481-6.00011-7.

- Motalebi, A.; Khondoker, M.A.H.; Kabir, G. A systematic review of life cycle assessments of 3D concrete printing. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2024, 5, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D Printing In Construction Market Report, 2022-2027, (n.d.). https://www.industryarc.com/Report/18132/3d-printing-in-construction-market.html (accessed , 2024). 5 June.

- NASA Looks to Advance 3D Printing Construction Systems for the Moon and Mars - NASA, (n.d.). https://www.nasa.gov/technology/manufacturing-materials-3-d-printing/nasa-looks-to-advance-3d-printing-construction-systems-for-the-moon-and-mars/ (accessed , 2024). 5 June.

- Zhu, B.; Nematollahi, B.; Pan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y. 3D concrete printing of permanent formwork for concrete column construction. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Dong, S.; Yu, X.; Han, B. A review of the current progress and application of 3D printed concrete. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.H. A review of “3D concrete printing”: Materials and process characterization, economic considerations and environmental sustainability. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Yuan, Q.; Peng, J. Effect of coarse aggregate on printability and mechanical properties of 3D printed concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Kim, J.-H. 3D Concrete Printing: A Systematic Review of Rheology, Mix Designs, Mechanical, Microstructural, and Durability Characteristics. Materials 2021, 14, 3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Li, V.C. Influence of printing parameters on 3D printing engineered cementitious composites (3DP-ECC). Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambily, P.; Kaliyavaradhan, S.K.; Rajendran, N. Top challenges to widespread 3D concrete printing (3DCP) adoption – A review. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2023, 28, 300–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Ren, Q. Mechanical anisotropy of ultra-high performance fibre-reinforced concrete for 3D printing. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahul, A.; Mohan, M.K.; De Schutter, G.; Van Tittelboom, K. 3D printable concrete with natural and recycled coarse aggregates: Rheological, mechanical and shrinkage behaviour. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Pang, B.; Liu, Z.; Liu, G. Extrusion-based 3D printing concrete with coarse aggregate: Printability and direction-dependent mechanical performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemian, A.; Yuan, X.; Cochran, E.; Khoshnevis, B. Cementitious materials for construction-scale 3D printing: Laboratory testing of fresh printing mixture. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 145, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, H.; Nerella, V.N.; Mechtcherine, V. Developing and Testing of Strain-Hardening Cement-Based Composites (SHCC) in the Context of 3D-Printing. Materials 2018, 11, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moelich, G.M.; Kruger, J.; Combrinck, R. Plastic shrinkage cracking in 3D printed concrete. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2020, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambach, M.; Volkmer, D. Properties of 3D-printed fiber-reinforced Portland cement paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 79, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot, A.; Rangeard, D.; Pierre, A. Structural built-up of cement-based materials used for 3D-printing extrusion techniques. Mater. Struct. 2015, 49, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.; Tang, S.; Yang, H.; Li, W.; Shi, M. Influences of Air-Voids on the Performance of 3D Printing Cementitious Materials. Materials 2021, 14, 4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manikandan, K.; Wi, K.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Qin, H. Characterizing cement mixtures for concrete 3D printing. Manuf. Lett. 2020, 24, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, H.; Kashani, A. Analysis of rheological properties and printability of a 3D-printing mortar containing silica fume, hydrated lime, and blast furnace slag. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukrishnan, S.; Kua, H.W.; Na Yu, L.; Chung, J.K.H. Fresh Properties of Cementitious Materials Containing Rice Husk Ash for Construction 3D Printing. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 04020195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinoco, M.P.; Gouvêa, L.; Martins, K.d.C.M.; Filho, R.D.T.; Reales, O.A.M. The use of rice husk particles to adjust the rheological properties of 3D printable cementitious composites through water sorption. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.; Lim, J.H.; Tan, M.J. Mechanical properties and deformation behaviour of early age concrete in the context of digital construction. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2019, 165, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Weng, Y.; Wong, T.N.; Tan, M.J. Mixture Design Approach to optimize the rheological properties of the material used in 3D cementitious material printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 198, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Figueiredo, S.C.; Li, Z.; Chang, Z.; Jansen, K.; Çopuroğlu, O.; Schlangen, E. Improving printability of limestone-calcined clay-based cementitious materials by using viscosity-modifying admixture. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jansen, K.; Zhang, H.; Rodriguez, C.R.; Gan, Y.; Çopuroğlu, O.; Schlangen, E. Effect of printing parameters on interlayer bond strength of 3D printed limestone-calcined clay-based cementitious materials: An experimental and numerical study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.-J.; Lin, C.; Tao, J.-L.; Ye, T.-H.; Fang, Y. Printability and particle packing of 3D-printable limestone calcined clay cement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soda, P.R.K.; Dwivedi, A.; M, S.C.; Gupta, S. Development of 3D printable stabilized earth-based construction materials using excavated soil: Evaluation of fresh and hardened properties. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 924, 171654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effect of Nanoclay on the Printability of Extrusion-based 3D Printable Mortar. NanoWorld J. 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Reales, O.A.M.; Duda, P.; Silva, E.C.; Paiva, M.D.; Filho, R.D.T. Nanosilica particles as structural buildup agents for 3D printing with Portland cement pastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 219, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Matos, P.; Zat, T.; Corazza, K.; Fensterseifer, E.; Sakata, R.; Mohamad, G.; Rodríguez, E. Effect of TiO2 Nanoparticles on the Fresh Performance of 3D-Printed Cementitious Materials. Materials 2022, 15, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Tran, P.; Ginigaddara, T.; Mendis, P. Exploration of using graphene oxide for strength enhancement of 3D-printed cementitious mortar. Addit. Manuf. Lett. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, P.; Chougan, M.; Cuevas, K.; Liebscher, M.; Mechtcherine, V.; Ghaffar, S.H.; Liard, M.; Lootens, D.; Krivenko, P.; Sanytsky, M.; et al. The effects of nano- and micro-sized additives on 3D printable cementitious and alkali-activated composites: a review. Appl. Nanosci. 2021, 12, 805–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaizi, A.M.; Huseien, G.F.; Lim, N.H.A.S.; Amran, M.; Samadi, M. Effect of nanomaterials inclusion on sustainability of cement-based concretes: A comprehensive review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadikolaee, M.R.; Cerro-Prada, E.; Pan, Z.; Korayem, A.H. Nanomaterials as Promising Additives for High-Performance 3D-Printed Concrete: A Critical Review. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.G.; Fang, Z.-Q.; Chu, S.-H.; Kwan, A.K.H. Improving mechanical properties of 3D printed mortar through synergistic effects of fly ash microspheres and nanosilica. Mag. Concr. Res. 2025, 77, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.; Hasany, M.; Kohestanian, M.; Mehrali, M. Micro/nano additives in 3D printing concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, H.; Zaidi, S.J.; Alnuaimi, N.A. Recent Advancements in the Nanomaterial Application in Concrete and Its Ecological Impact. Materials 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effect of Red Mud, Nanoclay, and Natural Fiber on Fresh and Rheological Properties of Three-Dimensional Concrete Printing. ACI Mater. J. 2021, 118, 97–110. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Yang, Y.; Wu, M.; Pang, B. Fresh properties of a novel 3D printing concrete ink. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 174, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.; Sonebi, M.; Amato, G.; Perrot, A.; Das, U.K. Influence of nanoclay on the fresh and rheological behaviour of 3D printing mortar. Mater. Today: Proc. 2022, 58, 1063–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Nassrullah, G.; Abu Al-Rub, R.K.; El-Khasawneh, B.; Ghaffar, S.H.; Kim, T.-Y. Influence of carbon nanotubes on printing quality and mechanical properties of 3D printed cementitious materials. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami, A.H.; Olabi, A.G.; Ayoub, M.; Aljaghoub, H.; Alasad, S.; Abdelkareem, M.A. 3D Concrete Printing: Recent Progress, Applications, Challenges, and Role in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Buildings 2023, 13, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, D.J.M.; Sanjayan, J.G. Green house gas emissions due to concrete manufacture. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2007, 12, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatt, R.J.; Wangler, T. On sustainability and digital fabrication with concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinoco, M.P.; de Mendonça, É.M.; Fernandez, L.I.C.; Caldas, L.R.; Reales, O.A.M.; Filho, R.D.T. Life cycle assessment (LCA) and environmental sustainability of cementitious materials for 3D concrete printing: A systematic literature review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, K.; Nicholas, P. Sustainability and 3D concrete printing: identifying a need for a more holistic approach to assessing environmental impacts. Arch. Intell. 2023, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.; Unluer, C.; Tan, M.J. Investigation of the rheology and strength of geopolymer mixtures for extrusion-based 3D printing. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 94, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujeeb, S.; Samudrala, M.; Lanjewar, B.A.; Chippagiri, R.; Kamath, M.; Ralegaonkar, R.V. Development of Alkali-Activated 3D Printable Concrete: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Ghazi, S.M.U.; Amjad, H.; Imran, M.; Khushnood, R.A. Emerging horizons in 3D printed cement-based materials with nanomaterial integration: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadikolaee, M.R.; Cerro-Prada, E.; Pan, Z.; Korayem, A.H. Nanomaterials as Promising Additives for High-Performance 3D-Printed Concrete: A Critical Review. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.P. Feynman, There’s plenty of room at the bottom, Resonance 16 (1999) 890–905.

- S. Mehnath, A.K. Das, S.K. Verma, M. Jeyaraj, Biosynthesized/green-synthesized nanomaterials as potential vehicles for delivery of antibiotics/drugs, in: Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry, Elsevier, 2021: pp. 363–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.coac.2020.12.011.

- K. Sobolev, How Nanotechnology Can Change the Concrete World Part Two of a Two-Part Series, American Ceramic Society Bulletin 84 (2005).

- Abid, N.; Khan, A.M.; Shujait, S.; Chaudhary, K.; Ikram, M.; Imran, M.; Haider, J.; Khan, M.; Khan, Q.; Maqbool, M. Synthesis of nanomaterials using various top-down and bottom-up approaches, influencing factors, advantages, and disadvantages: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 300, 102597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, N.; Kammakakam, I.; Falath, W. Nanomaterials: a review of synthesis methods, properties, recent progress, and challenges. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 1821–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, A.; Burnett, L.; Smith, J.V.; Kurmus, H.; Milas, J.; Arulrajah, A.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Abdul Kadir, A. Nanoparticles in Construction Materials and Other Applications, and Implications of Nanoparticle Use. Materials 2019, 12, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regalla, S.S.; N, S.K. Effect of nano SiO2 on rheology, nucleation seeding, hydration mechanism, mechanical properties and microstructure amelioration of ultra-high-performance concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, T.J.; Ponce, A.G.; Alvarez, V.A. Nano-clays from natural and modified montmorillonite with and without added blueberry extract for active and intelligent food nanopackaging materials. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 194, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.; Ruan, S.; Unluer, C.; Tan, M.J. Improving the 3D printability of high volume fly ash mixtures via the use of nano attapulgite clay. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2019, 165, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Mahmoud, Z.H.; Abdullaev, S.; Ali, F.K.; Naeem, Y.A.; Mizher, R.M.; Karim, M.M.; Abdulwahid, A.S.; Ahmadi, Z.; Habibzadeh, S.; et al. Nano titanium oxide (nano-TiO2): A review of synthesis methods, properties, and applications. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, G.; Stephan, D. Controlling cement hydration with nanoparticles. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 57, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Imam, M.K.; Irshad, K.; Ali, H.M.; Hasan, M.A.; Islam, S. Comparative Overview of the Performance of Cementitious and Non-Cementitious Nanomaterials in Mortar at Normal and Elevated Temperatures. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuesta, A.; Morales-Cantero, A.; De la Torre, A.G.; Aranda, M.A.G. Recent Advances in C-S-H Nucleation Seeding for Improving Cement Performances. Materials 2023, 16, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, E.; Matschei, T.; Stephan, D. Nucleation seeding with calcium silicate hydrate – A review. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 113, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Huang, S.; Corr, D.; Yang, Y.; Shah, S.P. Whether do nano-particles act as nucleation sites for C-S-H gel growth during cement hydration? Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 87, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, L.J.; Kalfat, R. Fresh and hardened performance of concrete enhanced with graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs). J. Build. Eng. 2023, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Sha, D.; Li, Q.; Zhao, S.; Ling, Y. Effect of Nano Silica Particles on Impact Resistance and Durability of Concrete Containing Coal Fly Ash. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, C. E EFFECT OF NANO-TiO₂ ON THE DURABILITY OF ULTRA-HIGH PERFORMANCE CONCRETE WITH AND WITHOUT A FLEXURAL LOAD. Ceram. - Silik. 2018, 62, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X. TiO2-Based Photocatalysts for Removal of Low-Concentration NOx Contamination. Catalysts 2025, 15, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Sanjayan, J.G.; Duan, W.H.; Nazari, A. Graphene Oxide Impact on Hardened Cement Expressed in Enhanced Freeze–Thaw Resistance. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2016, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.T.; Ferreira, I.M.; de Moraes, E.G.; Senff, L.; de Oliveira, A.P.N. 3D printed concrete for large-scale buildings: An overview of rheology, printing parameters, chemical admixtures, reinforcements, and economic and environmental prospects. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, N. Rheological requirements for printable concretes. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 112, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Zhou, D.; Khayat, K.H.; Feys, D.; Shi, C. On the measurement of evolution of structural build-up of cement paste with time by static yield stress test vs. small amplitude oscillatory shear test. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 99, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, Y.W.D.; Qian, Y.; Tan, M.J. Printability region for 3D concrete printing using slump and slump flow test. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2019, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Rawat, S.; Yang, R. (.; Mahil, A.; Zhang, Y. A comprehensive review on fresh and rheological properties of 3D printable cementitious composites. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V.N. Nerella, M. V.N. Nerella, M. Krause, V. Mechtcherine, Practice-Oriented Buildability Criteria for Developing 3D-Printable Concretes in the Context of Digital Construction, (2018). [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.; Tay, Y.; Paul, S.; Tan, M. Current challenges and future potential of 3D concrete printing. Mater. und Werkst. 2018, 49, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, N.; Ovarlez, G.; Garrault, S.; Brumaud, C. The origins of thixotropy of fresh cement pastes. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliyavaradhan, S.K.; Ambily, P.; Prem, P.R.; Ghodke, S.B. Test methods for 3D printable concrete. Autom. Constr. 2022, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Austin, S.A.; Lim, S.; Buswell, R.A.; Gibb, A.G.F.; Thorpe, T. Mix design and fresh properties for high-performance printing concrete. Mater. Struct. 2012, 45, 1221–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Wang, L. A critical review of preparation design and workability measurement of concrete material for largescale 3D printing. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2017, 12, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerella, V.; Näther, M.; Iqbal, A.; Butler, M.; Mechtcherine, V. Inline quantification of extrudability of cementitious materials for digital construction. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 95, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, J.K. Prediction of Concrete Pumping Using Various Rheological Models. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2014, 8, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paritala, S.; Singaram, K.K.; Bathina, I.; Khan, M.A.; Jyosyula, S.K.R. Rheology and pumpability of mix suitable for extrusion-based concrete 3D printing – A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Deng, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Mechtcherine, V.; Sun, Z. Predicting the static yield stress of 3D printable concrete based on flowability of paste and thickness of excess paste layer. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.H.; Jo, B.W.; Cho, W.; Kim, J.-H. Development of a 3D Printer for Concrete Structures: Laboratory Testing of Cementitious Materials. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2020, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-W.; Lee, H.-J.; Choi, M.-S. Correlation between thixotropic behavior and buildability for 3D concrete printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, J.; Cho, S.; Zeranka, S.; Viljoen, C.; van Zijl, G. 3D concrete printer parameter optimisation for high rate digital construction avoiding plastic collapse. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2020, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahul, A.; Santhanam, M.; Meena, H.; Ghani, Z. 3D printable concrete: Mixture design and test methods. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 97, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, J.; Zeranka, S.; van Zijl, G. 3D concrete printing: A lower bound analytical model for buildability performance quantification. Autom. Constr. 2019, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, N. A thixotropy model for fresh fluid concretes: Theory, validation and applications. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayathilakage, R.; Rajeev, P.; Sanjayan, J. Yield stress criteria to assess the buildability of 3D concrete printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prem, P.R.; Ravichandran, D.; Kaliyavaradhan, S.K.; Ambily, P. Comparative evaluation of rheological models for 3D printable concrete. Mater. Today: Proc. 2022, 65, 1594–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Meng, X.; Chen, J.-F.; Ye, L. Mechanical properties of structures 3D printed with cementitious powders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 93, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, D.; Tan, M.J.; Qian, S. Investigation of interlayer adhesion of 3D printable cementitious material from the aspect of printing process. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjayan, J.G.; Nematollahi, B.; Xia, M.; Marchment, T. Effect of surface moisture on inter-layer strength of 3D printed concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 172, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, T.; Schreter-Fleischhacker, M.; Shkundalova, O.; Neuner, M.; Hofstetter, G. Constitutive modeling of orthotropic nonlinear mechanical behavior of hardened 3D printed concrete. Acta Mech. 2023, 234, 5893–5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senff, L.; Labrincha, J.A.; Ferreira, V.M.; Hotza, D.; Repette, W.L. Effect of nano-silica on rheology and fresh properties of cement pastes and mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 2487–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quercia, G.; Hüsken, G.; Brouwers, H. Water demand of amorphous nano silica and its impact on the workability of cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Zhou, D.; Li, B.; Huang, H.; Shi, C. Effect of mineral admixtures on the structural build-up of cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 160, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Moo, G.S.J.; Kobayashi, H.; Wong, T.N.; Tan, M.J. Effect of Nanostructured Silica Additives on the Extrusion-Based 3D Concrete Printing Application. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, J.; Zeranka, S.; van Zijl, G. An ab initio approach for thixotropy characterisation of (nanoparticle-infused) 3D printable concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 224, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanotechnology for Improved Three-Dimensional Concrete Printing Constructability. ACI Mater. J. 2021, 118, 19–28. [CrossRef]

- M. Van Den Heever, F.A. Bester, P.J. Kruger, G.P.A.G. Van Zijl, Effect of silicon carbide (SiC) nanoparticles on 3D printability of cement-based materials, in: A. Zingoni (Ed.), Advances in Engineering Materials, Structures and Systems: Innovations, Mechanics and Applications, 1st ed., CRC Press, 2019: pp. 1616–1621. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429426506-279.

- Jiang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Wu, S.; Zheng, H.; Sun, W. Modification effect of nanosilica and polypropylene fiber for extrusion-based 3D printing concrete: Printability and mechanical anisotropy. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norhasri, M.M.; Hamidah, M.S.; Fadzil, A.M. Applications of using nano material in concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 133, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douba, A.; Ma, S.; Kawashima, S. Rheology of fresh cement pastes modified with nanoclay-coated cements. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, H.; Barluenga, G.; Perrot, A. Extrusion and structural build-up of 3D printing cement pastes with fly ash, nanoclays and VMAs. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, S.; Kim, J.H.; Corr, D.J.; Shah, S.P. Study of the mechanisms underlying the fresh-state response of cementitious materials modified with nanoclays. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 36, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, S.; Chaouche, M.; Corr, D.J.; Shah, S.P. Rate of thixotropic rebuilding of cement pastes modified with highly purified attapulgite clays. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 53, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Pan, T.; Yin, K. The Synergistic Effect of Ester-Ether Copolymerization Thixo-Tropic Superplasticizer and Nano-Clay on the Buildability of 3D Printable Cementitious Materials. Materials 2021, 14, 4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natanzi, A.S.; McNally, C. Experimental investigation of low carbon 3D printed concrete. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 3696–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.; Mohamed, N.A.N.; Paul, S.C.; Singh, G.B.; Tan, M.J.; Šavija, B. The Effect of Material Fresh Properties and Process Parameters on Buildability and Interlayer Adhesion of 3D Printed Concrete. Materials 2019, 12, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; She, W.; Yang, L.; Liu, G.; Yang, Y. Rheological and harden properties of the high-thixotropy 3D printing concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 201, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Xin, J.; Huang, M. The printable and hardened properties of nano-calcium carbonate with modified polypropylene fibers for cement-based 3D printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Xu, W.; Niu, D. Effect of nano calcium carbonate on hydration characteristics and microstructure of cement-based materials: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 50, 104220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Che, Y.; Shi, M. Influences of calcium carbonate nanoparticles on the workability and strength of 3D printing cementitious materials containing limestone powder. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, W.; Che, Y. 3D Printing Cementitious Materials Containing Nano-CaCO3: Workability, Strength, and Microstructure. Front. Mater. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Chen, L. Influence of multi-walled nanotubes on the fresh and hardened properties of a 3D printing PVA mortar ink. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goracci, G.; Salgado, D.M.; Gaitero, J.J.; Dolado, J.S. Electrical Conductive Properties of 3D-Printed Concrete Composite with Carbon Nanofibers. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosson, M.; Brown, L.; Sanchez, F. Early-Age Performance of 3D Printed Carbon Nanofiber and Carbon Microfiber Cement Composites. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2020, 2674, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, K.; Mousavi, S.S.; Dehestani, M. Influence of nano-coated micro steel fibers on mechanical and self-healing properties of 3D printable concrete using graphene oxide and polyvinyl alcohol. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2023, 38, 1312–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulaj, A.; Salet, T.; Lucas, S. Mechanical properties and self-sensing ability of graphene-mortar compositions with different water content for 3D printing applications. Mater. Today: Proc. 2022, 70, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, R.H.; Silva, R.S.; Nascimento, L.L.; Okura, M.H.; Patrocinio, A.O.T.; Rossignolo, J.A. Photocatalytic and Antimicrobial Activity of TiO2 Films Deposited on Fiber-Cement Surfaces. Catalysts 2023, 13, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikkar, H.; Kapre, V.; Diwan, A.; Sekar, S. Titanium dioxide as a photocatalyst to create self-cleaning concrete. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021, 45, 4058–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahabizadeh, B.; Segundo, I.R.; Pereira, J.; Freitas, E.; Camões, A.; Tavares, C.J.; Teixeira, V.; Cunha, V.M.C.F.; Costa, M.F.M.; Carneiro, J.O. Development of Photocatalytic 3D-Printed Cementitious Mortars: Influence of the Curing, Spraying Time Gaps and TiO2 Coating Rates. Buildings 2021, 11, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahabizadeh, B.; Segundo, I.R.; Pereira, J.; Freitas, E.; Camões, A.; Teixeira, V.; Costa, M.F.; Cunha, V.M.; Carneiro, J.O. Photocatalysis of functionalised 3D printed cementitious materials. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Huang, M.; Xin, J.; Chen, P. The fresh and hardened properties of 3D printing cement-base materials with self-cleaning nano-TiO2:An exploratory study. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, H.A.; Mutalib, A.A.; Kaish, A.B.M.A.; Syamsir, A.; Algaifi, H.A. Development of Ultra-High-Performance Silica Fume-Based Mortar Incorporating Graphene Nanoplatelets for 3-Dimensional Concrete Printing Application. Buildings 2023, 13, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.; Yang, H. Hydration products, pore structure, and compressive strength of extrusion-based 3D printed cement pastes containing nano calcium carbonate. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Xin, J.; Huang, M. The printable and hardened properties of nano-calcium carbonate with modified polypropylene fibers for cement-based 3D printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Chen, T.; Fan, K.; Zhang, M. Effect of nano-silica sol dosage on the properties of 3D-printed concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Wu, S.; Zheng, H.; Sun, W. Modification effect of nanosilica and polypropylene fiber for extrusion-based 3D printing concrete: Printability and mechanical anisotropy. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagasuntharam, S.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Sanjayan, J. Investigating PCM encapsulated NaOH additive for set-on-demand in 3D concrete printing. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douba, A.; Ma, S.; Kawashima, S. Rheology of fresh cement pastes modified with nanoclay-coated cements. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, U.; Ma, J.; Baharlou, E.; Ozbulut, O.E. Effects of viscosity modifying admixture and nanoclay on fresh and rheo-viscoelastic properties and printability characteristics of cementitious composites. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, E.M.; Kara, B.; Bundur, Z.B.; Ozyurt, N.; Bebek, O.; Gulgun, M.A. A comparative evaluation of sepiolite and nano-montmorillonite on the rheology of cementitious materials for 3D printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Wang, Z.; Yu, C.; Qian, X.; Chen, R.; Zhou, X.; Weng, Y.; Song, Y.; Ruan, S. Properties and microstructures of 3D printable sulphoaluminate cement concrete containing industrial by-products and nano clay. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejaeghere, I.; Sonebi, M.; De Schutter, G. Influence of nano-clay on rheology, fresh properties, heat of hydration and strength of cement-based mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 222, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, C.; Francioso, V.; Velay-Lizancos, M. Modification of CO2 capture and pore structure of hardened cement paste made with nano-TiO2 addition: Influence of water-to-cement ratio and CO2 exposure age. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, V.; Uthaman, S. Environmental impact of sustainable green concrete. In Smart Nanoconcrete. In Smart Nanoconcretes and Cement-Based Materials; Properties, Modelling and Applications Micro and Nano Technologies, Ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, H.; Moura, B.; Soares, N. Advancements in nano-enabled cement and concrete: Innovative properties and environmental implications. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasreen, M.M.; Banfill, P.F.G.; Menzies, G.F. Life-Cycle Assessment and the Environmental Impact of Buildings: A Review. Sustainability 2009, 1, 674–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, L.; Castell, A.; Pérez, G.; Solé, C.; Boer, D.; Cabeza, L.F. Evaluation of the environmental impact of experimental buildings with different constructive systems using Material Flow Analysis and Life Cycle Assessment. Appl. Energy 2013, 109, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellenberger, D.; Althaus, H.-J. Relevance of simplifications in LCA of building components. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, S.; Basavaraj, A.S.; Rahul, A.; Santhanam, M.; Gettu, R.; Panda, B.; Schlangen, E.; Chen, Y.; Copuroglu, O.; Ma, G.; et al. Sustainable materials for 3D concrete printing. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.W.; de Lannoy, C.-F.; Wiesner, M.R. Cellulose Nanomaterials in Water Treatment Technologies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 5277–5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolgun, G.K.; Koşan, M.; Kayfeci, M.; Georgiev, A.G.; Keçebaş, A. Life Cycle Assessment and Cumulative Energy Demand Analyses of a Photovoltaic/Thermal System with MWCNT/Water and GNP/Water Nanofluids. Processes 2023, 11, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Krishnamurthy, K.V.; Singh, S. Experimental studies of TiO2 nanoparticles synthesized by sol-gel and solvothermal routes for DSSCs application. Results Phys. 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, P.; Isaacs, J.A.; Eckelman, M.J. Net energy benefits of carbon nanotube applications. Appl. Energy 2016, 173, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroccio, S.C.; Scarfato, P.; Bruno, E.; Aprea, P.; Dintcheva, N.T.; Filippone, G. Impact of nanoparticles on the environmental sustainability of polymer nanocomposites based on bioplastics or recycled plastics – A review of life-cycle assessment studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Martens, M. Mathot, F. Bos, J. Coenders, Optimising 3D Printed Concrete Structures Using Topology Optimisation, in: D.A. Hordijk, M. Luković (Eds.), High Tech Concrete: Where Technology and Engineering Meet, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2018: pp. 301–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59471-2_37.

- Liew, A.; López, D.L.; Van Mele, T.; Block, P. Design, fabrication and testing of a prototype, thin-vaulted, unreinforced concrete floor. Eng. Struct. 2017, 137, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.T. Bukhari, S.Q. Bukhari, M. Fahad, Sustainability evaluation of home appliance industry in Pakistan, in: F.M. Da Silva, H. Bártolo, P. Bártolo, R. Almendra, F. Roseta, H.A. Almeida, A.C. Lemos (Eds.), Challenges for Technology Innovation: An Agenda for the Future, 1st ed., CRC Press, 2017: pp. 233–235. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315198101-41.

- Heywood, K.; Nicholas, P. Sustainability and 3D concrete printing: identifying a need for a more holistic approach to assessing environmental impacts. Arch. Intell. 2023, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangler, T.; Lloret, E.; Reiter, L.; Hack, N.; Gramazio, F.; Kohler, M.; Bernhard, M.; Dillenburger, B.; Buchli, J.; Roussel, N.; et al. Digital Concrete: Opportunities and Challenges. RILEM Tech. Lett. 2016, 1, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labonnote, N.; Rønnquist, A.; Manum, B.; Rüther, P. Additive construction: State-of-the-art, challenges and opportunities. Autom. Constr. 2016, 72, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Hack, T. N. Hack, T. Wangler, J. Mata-Falcón, K. Dörfler, N. Kumar, A. Walzer, K. Graser, L. Reiter, H. Richner, J. Buchli, W. Kaufmann, R. Flatt, F. Gramazio, M. Kohler, MESH MOULD: AN ON SITE, ROBOTICALLY FABRICATED, FUNCTIONAL FORMWORK, 2017.

- Habert, G.; Arribe, D.; Dehove, T.; Espinasse, L.; Le Roy, R. Reducing environmental impact by increasing the strength of concrete: quantification of the improvement to concrete bridges. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 35, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustí-Juan, I.; Habert, G. Environmental design guidelines for digital fabrication. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2780–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Synthesis Method | Nanomaterials Commonly Produced |

| Sol-Gel | SiO₂, TiO₂, ZrO₂, Fe₂O₃, other metal oxide nanoparticles |

| Hydrothermal | SiO₂, TiO₂, Fe₃O₄, ZrO₂, nano clays (montmorillonite, attapulgite), other oxides |

| Co-precipitation | Fe₃O₄, ZrO₂, other metal oxide nanoparticles |

| Green Synthesis | SiO₂, TiO₂, Fe₂O₃, ZrO₂, Fe₃O₄ (using plant extracts, etc.) |

| CVD | CNTs, graphene, other carbon nanomaterials |

| Arc Discharge | CNTs, fullerenes, carbon onions |

| Laser Ablation | CNTs, fullerenes, graphene, metal nanoparticles |

| Electrochemical Exfoliation | Graphene, graphene oxide |

| Mechanical/ Ultrasonic Exfoliation | Graphene, nano clays (montmorillonite, attapulgite) |

| Solution/ Melt Blending, In-situ Polymerisation | Montmorillonite and attapulgite nano clay composites |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).