Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- Population (P): Individuals with diabetes (type 1 or type 2), including adults (and adolescents where data are available), with or without diagnosed comorbid mental health conditions.

- Intervention (I): Integrated care interventions that combine diabetes care with mental health care. This encompasses collaborative care models, co-located services (embedding mental health providers in diabetes care settings), stepped-care approaches for mental health, and technology-enabled integration (telemedicine, digital mental health tools) implemented alongside usual diabetes treatment.

- Comparison (C): Usual diabetes care without structured mental health integration, or less-integrated approaches. This could include standard care where mental health is addressed via referral only, or a comparison between integrated intervention versus control (waiting list or minimal intervention).

- Outcomes (O): Primary outcomes include glycemic control (typically measured by HbA1c levels) and mental health outcomes (e.g., depression severity, depression remission rates, anxiety levels, diabetes distress scores). Secondary outcomes include diabetes self-management and adherence (medication adherence, lifestyle changes), quality of life, health service utilization (hospitalizations, emergency visits), and any reported adverse effects or cost outcomes.

Methods

Protocol and Registration

Eligibility Criteria

- Collaborative care models: structured programs involving a team (e.g., primary care or diabetes physicians, mental health specialists, nurses, care managers) working together to manage both diabetes and mental health conditions with shared care plans.

- Co-located services: interventions where mental health professionals (such as psychologists, psychiatrists or counselors) are physically present in diabetes care clinics or primary care practices, providing services in the same location and coordinating with diabetes care providers.

- Stepped care approaches: programs that provide a tiered model of mental health intervention intensity (from low-intensity self-management support up to specialist care) based on patient needs and responses.

- Glycemic control: primarily HbA1c levels, as well as other metabolic outcomes if reported (e.g., fasting glucose, blood pressure or lipid levels in multimorbidity studies).

- Mental health outcomes: depression and/or anxiety symptom scales (such as PHQ-9 for depression, GAD-7 for anxiety), rates of clinical depression remission or response, levels of diabetes-specific distress, or other psychological outcomes (e.g., well-being, stress).

- Behavioral outcomes: medication adherence (e.g., proportion of medications taken or refilled), diabetes self-care activities (diet, exercise, glucose monitoring adherence), or attendance rates to mental health appointments.

- Quality of life: evaluated by general or diabetes-specific quality of life instruments.

- Healthcare utilization and costs: such as number of hospital admissions, emergency department visits, overall healthcare costs, or cost-effectiveness metrics (e.g., cost per quality-adjusted life year).

Information Sources and Search Strategy

Study Selection

Data Extraction

Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

Data Synthesis

Results

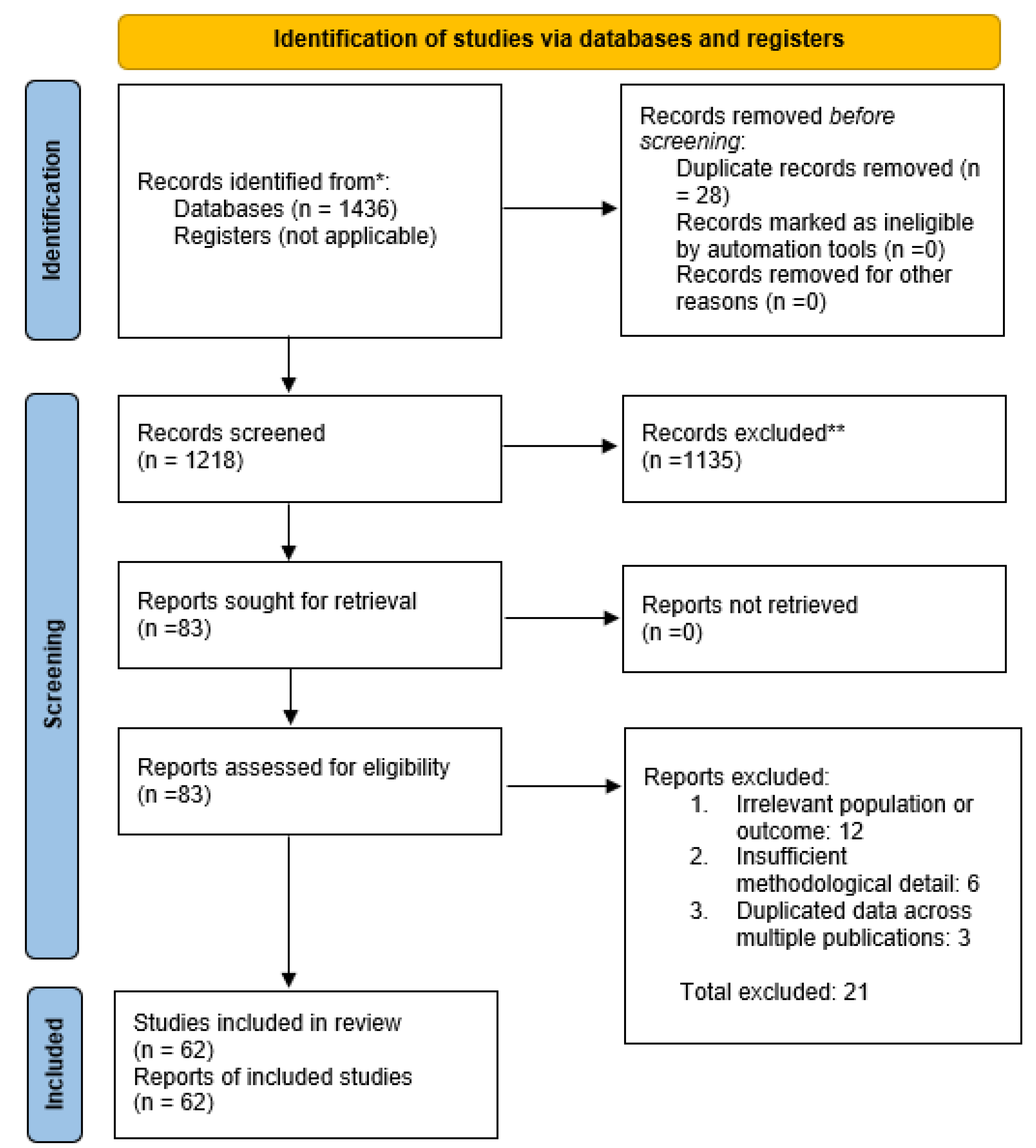

Study Selection

- Collaborative Care: This was the most common approach, featured in numerous RCTs. Collaborative care typically involved a care manager (often a nurse, diabetes educator, or social worker) who coordinated between the primary diabetes care team and a mental health specialist (e.g., psychologist or psychiatrist). These programs included systematic screening for depression or distress, evidence-based treatments (antidepressant medications or psychotherapy such as problem-solving therapy), regular follow-up and adjustment of treatment plans, and psychiatric case consultation for complex cases. One seminal example is the TEAMcare trial by Katon et al. (2010) in primary care clinics: in 214 patients with diabetes (or heart disease) and co-existing depression, nurse-led collaborative management led to significantly greater improvements in HbA1c, blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, and depression symptoms compared to usual care [32,33,34]. This highlighted how addressing mental health can simultaneously improve cardiometabolic control. Several other trials and a meta-analysis (see Results below) have confirmed the effectiveness of collaborative care for patients with diabetes and depression.

- Co-Located Services: In some interventions, mental health professionals were physically co-located in endocrinology or diabetes clinics. In these models, patients could see a mental health provider (like a clinical psychologist or counselor) in the same clinic visit or facility as their diabetes care, facilitating warm hand-offs between providers. Co-location was shown to normalize and destigmatize mental health care as part of chronic disease management. For instance, a 2023 study in diabetes clinic settings found that integrating a psychologist on-site led to a high completion rate of mental health referrals (over 80% of referred patients engaged in care, versus ~30% typical in standard referral systems). Over a 12-month period, patients receiving co-located mental health care experienced decreased diabetes-related distress, significant improvements in depressive symptom scores, and a reduction in HbA1c, alongside increased patient satisfaction with care.

- Stepped Care: Only a few studies explicitly used a stepped-care design in diabetes populations. Stepped care involves providing the lowest intensity intervention first (such as self-management education or guided self-help for mild symptoms) and “stepping up” to more intensive therapy (such as specialized psychotherapy or psychiatric care) for those who do not improve. While direct evidence in diabetes is limited, this model has shown success in general mental health treatment. An umbrella review by Jeitani et al. (2024) covering multiple conditions found stepped mental health care improved depression outcomes significantly compared to usual care. In diabetes care, stepped approaches are conceptually appealing to efficiently allocate resources, though more research in diabetic populations is needed (some included programs incorporated elements of stepping within collaborative care frameworks, escalating care based on symptom monitoring).

- Digital Integration: Several recent interventions leveraged telemedicine and digital health platforms to integrate mental health support. These included telehealth counseling or psychiatric consultation for people with diabetes, internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy programs tailored for those managing diabetes and depression, and mobile applications for mood and glucose tracking with feedback. Digital integration addresses access barriers, especially in rural or underserved areas. In this review, a handful of RCTs tested technology-supported integrated care: for example, trials of online CBT programs for patients with diabetes reported significant reductions in depression severity and improved treatment adherence compared to control groups, with some also noting reduced diabetes distress and small improvements in HbA1c. Telepsychiatry integrated into diabetes clinics similarly showed promise in improving mental health outcomes. However, digital modalities require patients to have internet access and digital literacy; one included study noted that purely app-based approaches might inadvertently exclude some vulnerable patients, highlighting an equity concern.

| Study (Year) & Design | Population (Sample Size) | Integrated Intervention (Model) | Key Outcomes vs. Comparison (Usual Care) |

| Katon et al., 2010 (TEAMcare RCT) | Adults with type 2 diabetes (and/or CVD) + depression (N=214) in primary care clinics | Collaborative care: Nurse care manager coordinated care between primary care physicians and psychiatrist; stepped medication adjustments and problem-solving therapy | ↓ HbA1c (mean 0.5% greater reduction), ↓ systolic BP, ↓ LDL cholesterol, and ↓ depression severity; higher satisfaction with care. |

| Atlantis et al., 2014 (Meta-analysis) | Patients with type 2 diabetes + depression across 8 RCTs (N=3,314 total) | Collaborative care (various programs): Multidisciplinary management of depression in diabetes (or chronic illness) populations | Depression: significantly improved outcomes (pooled effect showing higher remission rates); Glycemic control: modest but significant HbA1c improvement (~0.3% absolute reduction). Concluded collaborative care is effective for depression and has a small positive impact on diabetes control. |

| “Co-Located Care” Study, 2023 | Adults with diabetes (type 1 or 2) with high distress or depression in specialty diabetes clinics (N≈150) | Co-located mental health care: Psychologist embedded in diabetes clinic; patients received on-site counseling and management integrated with diabetes visits | ↓ Diabetes distress and ↓ PHQ-9 depression scores over 12 months; ↓ HbA1c by ~0.4% (from baseline) in intervention arm, whereas control group had no significant change (between-group difference significant). ~85% of referred patients engaged in mental health services (vs ~30% in usual care referrals). Improved patient-reported satisfaction with care. |

| COMPASS Initiative, 2016 | Real-world multi-site program in USA: adults with uncontrolled diabetes and/or CVD + depression (N=3,800 across 18 primary care clinics) | Collaborative care (population management): Care managers plus psychiatric consultants, using registry tracking and treatment protocols for depression integrated with chronic disease care | After 6 months: 40% of patients had a ≥50% reduction in depression scores. Among those with baseline HbA1c >9%, ≈25% achieved substantial HbA1c improvement (≥1% reduction). Also observed improvements in blood pressure control in those with hypertension. Demonstrated successful scaling of collaborative care with notable mental and physical health benefits. |

| Rutter et al., 2017 (Cost-effectiveness RCT) | Primary care patients with persistent depression (some with diabetes in subgroup) (N≈200) | Collaborative care (stepped): 12-month program with primary care physician, psychologist, and psychiatrist team; stepped antidepressant and psychotherapy | ↑ Depression-free days (intervention group experienced more depression-free days over 12 months). Costs: Slight increase in direct care costs, but cost per QALY gained was within acceptable range, indicating the approach was cost-effective. Supports economic viability of integrated care for mental health in chronic illness management. |

Risk of Bias Within Studies

Effects of Interventions on Key Outcomes

Synthesis of Results

Discussion

Principal Findings and Interpretation

Heterogeneity of Interventions and Outcomes

- Intervention components: Some interventions were intensive (e.g., monthly psychiatric case reviews, active medication management, and therapy sessions), while others were minimal (e.g., a few counseling sessions or enhanced screening). This likely led to variability in effect sizes – for instance, more intensive collaborative care tended to produce larger depression improvements than brief interventions. Digital interventions had different levels of human involvement, which could affect outcomes.

- Populations: Some studies focused exclusively on patients with diagnosed major depression (which might yield larger improvements in depression scores, as there was more room to improve), whereas others included any patient with diabetes regardless of baseline mental health (in which case population-wide outcomes might show smaller average changes). Additionally, a few studies targeted subgroups like those with poorly controlled diabetes or those from underserved communities, which might respond differently to interventions.

- Settings: Primary care vs specialty diabetes clinics vs community programs – each setting brings different resources and constraints. For example, primary care-based interventions can reach many patients but may face time constraints, whereas specialty clinics might have more focus but only see the most complex patients. These contextual differences introduce heterogeneity in implementation and outcomes.

- Outcomes measured: Not every study measured all outcomes; some focused-on depression and HbA1c, others added quality of life or cost outcomes. This made comprehensive comparison challenging. Moreover, timing of outcome measurement varied (some looked at 6-month outcomes, others at 12 or 18 months), affecting the observed impact (e.g., glycemic changes might be larger at 12 months than at 6).

Implications for Clinical Practice and Health Policy

- Routine Integration is Justified: Given the improved outcomes, healthcare systems and diabetes care providers should move toward routine integration of mental health services in diabetes care settings. It should become standard practice to have mental health screening (for depression, anxiety, distress) and, importantly, to have resources in place for providing care when patients screen positive. This might involve embedding mental health professionals in diabetes clinics or establishing collaborative care programs. The refrain from our findings is that mental health integration is not optional but essential for comprehensive diabetes care.

- Training and Workforce: To implement integrated care at scale, there is a need to train more providers in delivering psychosocial care. Primary care physicians and endocrinologists should be trained to recognize and initiate management of common mental health conditions in diabetes (e.g., using motivational interviewing, basic psychopharmacology for antidepressants) and to work in teams with mental health specialists. At the same time, more diabetes-knowledgeable mental health professionals (psychologists, clinical social workers) are needed. Task-sharing models can be beneficial: for example, training nurses or community health workers to deliver brief mental health interventions under supervision, which has shown promise in resource-limited settings.

- Patient Education and Engagement: Integrating care is not only about providers; patients and families should be educated that emotional well-being is a part of diabetes management. Reducing stigma around seeking mental health support can improve engagement. In practice, when mental health care is offered as part of diabetes care, patients may be more receptive (seeing it as routine). Providers should introduce mental health screenings and referrals in a normalizing way – e.g., “We ask all our patients about mood and stress, because it’s an important part of diabetes health.” This approach can increase uptake of services, as demonstrated by higher referral completion rates in co-located models.

- Integrated Care in Different Settings: For large hospital systems, co-locating behavioral health in diabetes or primary care clinics can be highly effective to facilitate warm hand-offs. Smaller practices might use a collaborative care approach where they partner with off-site mental health providers via telehealth or shared care plans. The use of telemedicine can extend integrated care to rural areas where specialist access is limited. Our findings showed telehealth interventions can be effective, but ensuring patients can use the technology is key. Hybrid models (combining in-person and digital) may work best.

- Policy and Funding: Sustainable integration requires supportive policies. Fee-for-service models often segregate mental health reimbursement from medical care, which is a barrier. Payers and policymakers should consider blended or collaborative care payment models (for example, the Collaborative Care Model has CPT billing codes in the US). Reimbursement structures need realignment so that team-based care and care coordination activities (often not reimbursed in traditional models) are supported. Additionally, including mental health metrics in diabetes quality dashboards and pay-for-performance programs would incentivize providers and organizations to prioritize this aspect. For instance, tracking the percentage of diabetes patients who receive depression screening and treatment as a quality indicator could drive integration.

- Addressing Disparities: Integrated care can improve access to mental health support for vulnerable groups, such as ethnic minorities or low-income patients, who typically face barriers in traditional mental health settings. By bringing services to where patients already receive care (their diabetes clinic), we lower barriers. Our review noted that integrated programs, especially when augmented by telehealth or community health workers, can reduce structural obstacles and improve continuity for underserved populations. Nonetheless, vigilance is required to ensure new models don’t inadvertently exclude some groups – for example, digital programs must be made user-friendly and accessible to those with low tech literacy. Culturally tailored approaches, like employing bilingual mental health providers or culturally adapted interventions [35,36,37] were highlighted as crucial for engagement. Health systems should invest in culturally competent integrated care to maximize benefit across diverse patient populations.

Limitations of the Evidence Base

- Research Design and Quality: Not all included studies were high-quality RCTs. We included some quasi-experimental studies to capture real-world implementations, and these have inherent biases. The lack of blinding in many trials could inflate perceived effects on subjective outcomes (like patient-reported depression symptoms). Additionally, a few studies had small sample sizes or short follow-up durations, limiting the robustness of conclusions about long-term effects. As noted earlier, heterogeneity in study design and execution means our findings are based on a diverse set of studies with varying internal validity. We attempted to account for risk of bias in interpreting results, but a formal meta-regression on study quality was not feasible due to the narrative approach.

- Population Gaps: There is a notable evidence gap for certain populations. Most research has focused on middle-aged and older adults with type 2 diabetes. We found very few studies specifically targeting children or adolescents with diabetes [40]. Youth with type 1 diabetes, for example, face unique psychosocial challenges and developmental issues; integrated care models might need adaptation for pediatric endocrinology settings. The absence of robust studies in this group is a limitation – our findings may not directly generalize to pediatric diabetes care. Likewise, pregnant women with diabetes (e.g., gestational diabetes or type 1/type 2 in pregnancy) were not explicitly studied in the context of integrated mental health care and could benefit from future research.

- Outcome Measures: The studies used a variety of outcome measures for mental health (different scales for depression, some focusing on distress, etc.), which makes direct comparison difficult. Few studies examined long-term “hard” outcomes like incidence of diabetes complications or mortality. It stands to reason that improved HbA1c and mental health might eventually translate into fewer complications and longer life, but this was beyond the scope of existing research. Also, quality of life, while included in some studies, was not universal; thus, our understanding of how much integrated care improves overall life satisfaction or functioning is incomplete.

- Follow-up Duration: Most trials only reported outcomes up to 12 months. As such, we do not fully know if the improvements in depression and glycemic control are sustained over years or if patients might relapse when integrated programs end. Long-term sustainability and whether periodic “boosters” are needed remain unclear. Additionally, any potential long-term adverse effects or patients’ eventual reliance on the integrated support (and outcomes after withdrawal of extra support) are not well studied.

- Generalizability: As mentioned, the geographic distribution of studies leans heavily toward high-income countries. Caution is warranted in extrapolating to low-resource settings where healthcare infrastructure and workforces differ. The fact that implementation is “patchy” and evidence mostly Western raises the issue of generalizability. Socio-cultural factors play a role in mental health stigma and help-seeking; integrated care that works in one culture may need modification in another. There is a need for more international research to validate these models across different healthcare systems and cultures.

- Publication and Reporting Bias: It is possible that studies showing positive results were more likely to be published, while negative or null trials (if any) might be underreported. We did not find clear evidence of unpublished large trials, but given the relatively uniformly positive tone of published studies, one should consider that some smaller efforts that found no improvement may not have made it to publication. This review attempted to be comprehensive, but we cannot rule out some degree of publication bias.

- This Review’s Limitations: Finally, with regard to our review process, we synthesized evidence across different study types without performing a formal meta-analysis for every outcome due to heterogeneity. While this allowed us to capture a broad picture, it means the review does not provide a single summary effect size for integrated care’s impact. Also, although we followed systematic methods, certain choices (like inclusion of quasi-experimental studies) and the qualitative nature of some synthesis could introduce subjectivity. We did not quantitatively assess inter-rater agreement for study inclusion or bias assessment (relying on consensus resolution). Nonetheless, we believe these limitations do not invalidate the overall conclusions but suggest that some caution and the need for further research remain.

Comparison with Other Reviews

Future Research Directions

- Long-Term and Sustainability Studies: There is a need for studies that look at outcomes beyond one year. Future RCTs or follow-up studies should examine whether improvements from integrated care are maintained over 2, 3, or 5 years. They should also evaluate if continuous integrated care is necessary or if patients can be stepped down to usual care after improvement without relapse. This ties into questions of the long-term viability and cost-effectiveness of keeping such programs running indefinitely.

- Focus on Diverse Populations: Research should focus on pediatrics (children and adolescents) with diabetes – for instance, testing integrated behavioral health interventions in pediatric diabetes clinics or family-based models. Additionally, more trials in low- and middle-income countries are needed. These could test task-shifting approaches (training lay counselors to provide mental health care as part of diabetes programs, for example) which might be more feasible in low-resource settings. Culturally tailored integrated care interventions, perhaps employing community health workers or peer supporters, merit testing in diverse ethnic communities to ensure the approach works for all.

- Specific Mental Health Conditions: While depression has been extensively studied, anxiety disorders, diabetes distress, and cognitive impairment [41,42]very few studies in diabetes deserve more attention. For example, does integrating care help prevent or slow cognitive decline in older diabetic patients? Can anxiety-focused interventions (like CBT for anxiety) integrate into diabetes visits improve both anxiety and diabetes outcomes? These specific questions remain under-explored.

- Component Analysis: Future studies might dismantle which components of integrated care are most critical. Is it the presence of a care manager, the psychiatric case review, the therapy sessions, or simply the systematic monitoring? Trials or implementation studies that vary one component at a time (factorial designs) could help optimize integrated care models for maximum impact at minimum cost.

- Digital and Hybrid Models: As technology evolves, research should continue to evaluate digital integrated care tools (apps, telehealth, remote monitoring). Particularly, there should be focus on how to effectively combine digital approaches with human care – for example, using automated mood tracking plus nurse follow-up – and testing those against traditional models. Ensuring equity in digital health (designing for low literacy, different languages, and accessible formats) should be part of these studies so that digital integration does not widen disparities.

- Policy and Systems Research: Another area is health services research on implementation: how to implement integrated care widely. Studying models of care integration in various healthcare systems, identifying barriers (such as those financial or regulatory mentioned) and testing interventions to overcome them (like new payment models, training programs) will be crucial. Essentially, now that efficacy is shown, how do we implement at scale? Research might include pragmatic trials or quality improvement initiatives that also collect outcome data.

- Cost-Benefit Over Time: More economic evaluations in diverse settings would bolster the case to policymakers. For example, do integrated programs save costs in a government-funded health system (like the NHS in the UK) as they appear to in some US systems? Long-term cost-benefit analyses factoring in avoided complications could strengthen the argument for funding integrated care.

Strengths and Weaknesses of this Review

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diabetes Available online:. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/diabetes (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Diabetes Available online:. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Gregg, E.W.; Pratt, A.; Owens, A.; Barron, E.; Dunbar-Rees, R.; Slade, E.T.; Hafezparast, N.; Bakhai, C.; Chappell, P.; Cornelius, V.; et al. The Burden of Diabetes-Associated Multiple Long-Term Conditions on Years of Life Spent and Lost. Nat Med 2024, 30, 2830–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facts & Figures. International Diabetes Federation.

- Beverly, E.A.; Gonzalez, J.S. The Interconnected Complexity of Diabetes and Depression. Diabetes Spectr 2025, 38, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducat, L.; Philipson, L.H.; Anderson, B.J. The Mental Health Comorbidities of Diabetes. JAMA 2014, 312, 691–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, M. Diabetes and Depression: Strategies to Address a Common Comorbidity Within the Primary Care Context. Am J Med Open 2023, 9, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Groot, M. Diabetes and Depression: Strategies to Address a Common Comorbidity Within the Primary Care Context. American Journal of Medicine Open 2023, 9, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, R.I. Diabetes and Depression. In Endotext; Feingold, K.R., Ahmed, S.F., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., Hofland, J., Kalra, S., Kaltsas, G., Kapoor, N., Koch, C., Kopp, P., Korbonits, M., Kovacs, C.S., Kuohung, W., Laferrère, B., Levy, M., McGee, E.A., McLachlan, R., Muzumdar, R., Purnell, J., Rey, R., Sahay, R., Shah, A.S., Singer, F., Sperling, M.A., Stratakis, C.A., Trence, D.L., Wilson, D.P., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth (MA), 2000.

- Anderson, R.J.; Freedland, K.E.; Clouse, R.E.; Lustman, P.J. The Prevalence of Comorbid Depression in Adults With Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, S.; Jena, B.N.; Yeravdekar, R. Emotional and Psychological Needs of People with Diabetes. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2018, 22, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangoulia, P.; Milionis, C.; Vlachou, E.; Ilias, I. The Interrelationship between Diabetes Mellitus and Emotional Well-Being: Current Concepts and Future Prospects. Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendekie, A.K.; Limenh, L.W.; Bizuneh, G.K.; Kasahun, A.E.; Wondm, S.A.; Tamene, F.B.; Dagnew, E.M.; Gete, K.Y.; Kassaw, A.T.; Dagnaw, A.D.; et al. Psychological Distress and Its Impact on Glycemic Control in Patients with Diabetes, Northwest Ethiopia. Front Med (Lausanne) 2025, 12, 1488023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee 1. Improving Care and Promoting Health in Populations: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2023, 47, S11–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimu, S.J.; Mahir, J.U.K.; Shakib, F.A.F.; Ridoy, A.A.; Samir, R.A.; Jahan, N.; Hasan, M.F.; Sazzad, S.; Akter, S.; Mohiuddin, M.S.; et al. Metabolic Reprogramming Through Polyphenol Networks: A Systems Approach to Metabolic Inflammation and Insulin Resistance. Medical Sciences 2025, 13, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, A.; Abunaser, R.; Khassawneh, A.; Alfaqih, M.; Khasawneh, A.; Abdo, N. The Bidirectional Relationship between Diabetes and Depression: A Literature Review. Korean J Fam Med 2018, 39, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Call to Improve Patient and Public Health Outcomes of Diabetes Available online:. Available online: https://www.apha.org/policy-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-briefs/policy-database/2022/01/07/call-to-improve-patient-and-public-health-outcomes-of-diabetes (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Hill-Briggs, F. The American Diabetes Association in the Era of Health Care Transformation. Diabetes Spectr 2019, 32, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The American Diabetes Association Releases the Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024 Available online:. Available online: https://diabetes.org/newsroom/press-releases/american-diabetes-association-releases-standards-care-diabetes-2024 (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Diabetes and the Nervous System: Linking Peripheral Neuropathy to Central Neurodegeneration[v1] | Preprints. Available online: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202508.1278/v1 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Mohib, M.M.; Uddin, M.B.; Rahman, M.M.; Tirumalasetty, M.B.; Al-Amin, M.M.; Shimu, S.J.; Alam, M.F.; Arbee, S.; Munmun, A.R.; Akhtar, A.; et al. Dysregulated Oxidative Stress Pathways in Schizophrenia: Integrating Single-Cell Transcriptomic and Human Biomarker Evidence. Psychiatry International 2025, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, M.W.; Lombardi, B.M.; Wu, S.; de Saxe Zerden, L.; Richman, E.L.; Fraher, E.P. Integrated Primary Care and Social Work: A Systematic Review. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 2018, 9, 175–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, D.E.; Kilbourne, A.M.; Nord, K.M.; Bauer, M.S. Mental Health Collaborative Care and Its Role in Primary Care Settings. Current psychiatry reports 2013, 15, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karam, M.; Chouinard, M.-C.; Poitras, M.-E.; Couturier, Y.; Vedel, I.; Grgurevic, N.; Hudon, C. Nursing Care Coordination for Patients with Complex Needs in Primary Healthcare: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Integrated Care 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, D.; Wang, M.; Hu, M.; Zhu, D.; Yu, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ding, R.; Zhao, M.; et al. Community-Based Integrated Care for Patients with Diabetes and Depression (CIC-PDD): Study Protocol for a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 2023, 24, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alodhialah, A.M.; Almutairi, A.A.; Almutairi, M. Short-Term Impact of Digital Mental Health Interventions on Psychological Well-Being and Blood Sugar Control in Type 2 Diabetes Patients in Riyadh. Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.; Marques-Pamies, M.; Valassi, E.; García-Martínez, A.; Serra, G.; Hostalot, C.; Fajardo-Montañana, C.; Carrato, C.; Bernabeu, I.; Marazuela, M.; et al. Implications of Heterogeneity of Epithelial-Mesenchymal States in Acromegaly Therapeutic Pharmacologic Response. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.B.; Frandsen, T.F. The Impact of Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) as a Search Strategy Tool on Literature Search Quality: A Systematic Review. Journal of the Medical Library Association 2018, 106, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA Statement Available online:. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Nobis, S.; Lehr, D.; Ebert, D.D.; Baumeister, H.; Snoek, F.; Riper, H.; Berking, M. Efficacy of a Web-Based Intervention with Mobile Phone Support in Treating Depressive Symptoms in Adults with Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Web-Based Depression Treatment for Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetic Patients | Diabetes Care | American Diabetes Association Available online:. Available online: https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/34/2/320/39236/Web-Based-Depression-Treatment-for-Type-1-and-Type (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Shimu, S.J. A 10-Year Retrospective Quantitative Analysis of The CDC Database: Examining the Prevalence of Depression in the Us Adult Urban Population. Frontiers in Health Informatics 2025, 6053–6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unutzer, J.; Katon, W.J.; Fan, M.-Y.; Schoenbaum, M.C.; Lin, E.H.B.; Della Penna, R.D.; Powers, D. Long-Term Cost Effects of Collaborative Care for Late-Life Depression. Am J Manag Care 2008, 14, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Unützer, J.; Katon, W.; Callahan, C.M.; Williams, J.W.; Hunkeler, E.; Harpole, L.; Hoffing, M.; Della Penna, R.D.; Noël, P.H.; Lin, E.H.B.; et al. Collaborative Care Management of Late-Life Depression in the Primary Care Setting: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2002, 288, 2836–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimu, S.J.; Islam, S. Gender Differences in Drug Addiction: Neurobiological, Social, and Psychological Perspectives in Women – A Systematic Review. Journal of Primeasia 2025, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkley, K.; Upsher, R.; Stahl, D.; Pollard, D.; Kasera, A.; Brennan, A.; Heller, S.; Ismail, K.; Winkley, K.; Upsher, R.; et al. Psychological Interventions to Improve Self-Management of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review; NIHR Journals Library, 2020.

- Winkley, K.; Upsher, R.; Stahl, D.; Pollard, D.; Brennan, A.; Heller, S.; Ismail, K. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials of Psychological Interventions to Improve Glycaemic Control in Children and Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabet Med 2020, 37, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, K.; Winkley, K.; Rabe-Hesketh, S. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials of Psychological Interventions to Improve Glycaemic Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. The Lancet 2004, 363, 1589–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltz-Cornelis, C. van der; Os, T.V.; Marwijk, H.V.; Leentjens, A.F. Effect of Psychiatric Consultation Models in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. In Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): Quality-assessed Reviews [Internet]; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (UK), 2010.

- Grey, M.; Whittemore, R.; Jeon, S.; Murphy, K.; Faulkner, M.S.; Delamater, A. ; TeenCope Study Group Internet Psycho-Education Programs Improve Outcomes in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 2475–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, A.; Jahan Shimu, S.; Jakanta Faika, M.; Islam, T.; Ferdous, N.-E.-; Nessa, A. Bangladeshi Parents’ Knowledge and Awareness about Cervical Cancer and Willingness to Vaccinate Female Family Members against Human Papilloma Virus: A Cross Sectional Study. Int J Community Med Public Health 2023, 10, 3446–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukierman-Yaffe, T.; Gerstein, H.C.; Colhoun, H.M.; Diaz, R.; García-Pérez, L.-E.; Lakshmanan, M.; Bethel, A.; Xavier, D.; Probstfield, J.; Riddle, M.C.; et al. Effect of Dulaglutide on Cognitive Impairment in Type 2 Diabetes: An Exploratory Analysis of the REWIND Trial. Lancet Neurol 2020, 19, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimu, S.J.; Patil, S.M.; Dadzie, E.; Tesfaye, T.; Alag, P.; Więckiewicz, G. Exploring Health Informatics in the Battle against Drug Addiction: Digital Solutions for the Rising Concern. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2024, 14, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- mhGAP Intervention Guide - Version 2. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549790 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Type 2 Diabetes in Adults: Management; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, 2022; ISBN 978-1-4731-1477-7.

- Cukierman-Yaffe, T.; Gerstein, H.C.; Colhoun, H.M.; Diaz, R.; García-Pérez, L.-E.; Lakshmanan, M.; Bethel, A.; Xavier, D.; Probstfield, J.; Riddle, M.C.; et al. Effect of Dulaglutide on Cognitive Impairment in Type 2 Diabetes: An Exploratory Analysis of the REWIND Trial. Lancet Neurol 2020, 19, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2019 Surveillance of Diabetes (NICE Guidelines NG17, NG18, NG19 and NG28); National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, 2019; ISBN 978-1-4731-3449-2.

| Outcome Domain | Effect of Integrated Care vs. Usual Care | Evidence Highlights |

| Depression symptoms | Significant improvement in nearly all studies (lower depression scores, higher remission rates) | Eight RCT meta-analysis: improved depressive outcomes. Large real-world program: 40% had major symptom reduction. |

| Anxiety symptoms | Improvement in studies measuring anxiety (moderate effect) | Less frequently measured; where reported, anxiety (e.g., GAD-7) decreased more in intervention groups. |

| Diabetes distress | Significant reduction (in all studies that measured it) | Co-located care study: reduced distress vs baseline. Integrated models alleviate diabetes-specific emotional burden. |

| Glycemic control (HbA1c) | Modest improvement (small HbA1c reduction, ~0.3–0.5%) in many studies; no studies showed deterioration | Recent meta-analysis: improved glycemia vs usual care. Several RCTs reported ∆HbA1c ~ –0.3% to –0.6%. |

| Adherence/Self-care | Improved medication adherence, diet/exercise behaviors, and care engagement | Integrated care tackling depression led to better self-management participation. Higher attendance in education/therapy sessions observed. |

| Quality of life | Mild improvements, especially in mental health-related quality of life and patient satisfaction | Patients report more holistic care and convenience. Some trials saw higher SF-36 mental component scores in intervention. |

| Healthcare use & costs | Trend toward reduced acute care use; cost-effective (and possibly cost-saving long-term) | Fewer ER visits/hospitalizations in some studies. Collaborative care found cost-effective with acceptable ICER. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).