1. Introduction

According to the National Health Institute of Czech Republic, up to 60% of the middle-aged population is overweight, with 25% of women and 22% of men suffering from obesity [

1]. This is linked to the increasing number and complexity of elective surgical procedures. We know that patients after elective surgery have a poor quality of life in all areas, such as pain, limited mobility and physical health [

2]. Patients recovery can be thus significantly influenced by thorough preoperative preparation – prehabilitation. Prehabilitation can be understood as a set of measures that can be implemented through physiotherapeutic intervention as part of the preoperative preparation before elective surgery. Physiotherapy procedures should be individually focused, based on the results of the kinesiological analysis (e.g. soft and scar tissue therapy, early verticalization, respiratory physiotherapy, thromboembolic prevention etc.). Depending on the patient's current condition before surgery, an individual or group exercise program may be recommended to increase cardiorespiratory efficiency. By implementing prehabilitation, a more favorable course of hospital stay, recovery, and improvement in the quality of life of operated patients can be expected [

3].

Several studies had shown interest in prehabilitation. For example, prehabilitation (exercise program and nutritional therapy) has been found to have a positive effect on reducing morbidity, reducing length of hospital stay, and improving quality of life. The effect of nutritional therapy alone is inferior compared to the effects of an exercise program. Thus, the use of a combination of exercise and nutritional therapy appears to be optimal [

4]. Similar results are shown in another study exploring the unfavorable perioperative outcomes in the elderly and comorbid population. The reason for these outcomes is malnutrition and poor tolerance to exercise. Positive outcomes can be expected when prehabilitation is applied in the form of a combination of exercise program and nutritional therapy, which should form a unified intervention [

5]. Other studies shown that although prehabilitation is effective, there is an inconsistency in the content of prehabilitation exercise programs and in the assessment of functional capacity of operated patients. The authors of these studies agree that it is necessary to develop an optimal prehabilitation exercise program with clearly structured interventions and to establish objective evaluation for assessing the functional capacity of operated patients. All these aspects require standardization before the final evaluation of the effect of exercise programs used in prehabilitation [

6,

7,

8]. Similar findings were also reached in another study, where exercise and nutritional therapy seem to be the optimal combination for improving the quality of life after transplantation surgery [

9]. In addition to these studies, we also know that a significant portion of patients aged 40-59 do not follow the recommendations of healthcare professionals who inform them about the need to include physical activity in their life [

10].

Nordic walking is a very popular physical activity and has been applied countless times in rehabilitation studies. For instance, Nordic walking has been applied as part of a rehabilitation program in patients after lung transplantation [

11,

12]. Furthermore, one study evaluated the physiological responses of the body when using Nordic walking in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [

13]. Another study monitored the parameters of oxygen uptake, energy expenditure, and heart rate in patients rehabilitated after a coronary event [

14]. Additionally, a study compared the effect of Nordic walking and conventional walking in patients with cardiovascular disease [

15]. The aforementioned mentioned studies consistently show an increase in cardiovascular performance, positive influence on bone and joint health, the immune system, psychological state, and improved fat burning.

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of this pilot observational study with prospective data collection over a six-week period (from September 30th to November 15th, 2019) is to test whether a Nordic walking exercise program alone would affect the functional capacity of enrolled participants. Volunteers (n = 10) from the University of the Third Age (U3A) of Jan Evangelista Purkyne University in Usti nad Labem (UJEP) were included in the study. All participants provided the authors of the pilot study with basic anamnestic data and signed an informed consent. The pilot study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Studies UJEP under number 374/19. The number of participants was based on the results of a similar study conducted in 2018 with one group of U3A volunteers who had completed a special training program [

16]. Sample size calculation (applied in STATISTICA software, version 12) in this case assumes that a significant difference between the baseline dataset and final dataset will be detected at n = 10.

The participants of the study underwent Nordic walking once a week under expert supervision on flat terrain without elevation gain. The intensity was set to moderate (approximately 6 km/hour), and the Talk Test was used to determine the correct intensity. The distance for the first week was set to 1 500 meters, and in each subsequent week, the distance was extended by 500 meters (in the sixth and last week, the participants finished a distance of 4 000 meters). Additionally, the participants performed the same exercise in the form of self-therapy once a week.

Our hypothesis was as follows: We hypothesize that a group of participants (n = 10) following a six-week Nordic Walking exercise program will demonstrate statistically significant improvement in functional capacity, as verified by standardized tests:

Six Minute Walk Test (6MWT) is a simple test for assessing submaximal load activity along a flat surface. Testing is normally performed in a long straight corridor of 30 meters, but a distance of 50 meters can also be used. The patient is asked to walk as fast as possible over a given distance, which is bounded by cones, and walk around these cones for six minutes. At any time during the testing, the patient can stop, slow down, or sit down [

17]. In our case, the testing was performed outdoors over a distance of 50 meters. In older populations, it is generally reported that the minimum meaningful change is 20 meters and a significant change is 50 meters [

18].

Timed Up and Go test (TUG) is a test for a wide range of diagnoses. During the test, the patient is asked to get up from the chair on command, walk to a cone three meters away, walk around it, and then return to the chair and sit down. The standard is to complete the test within 12 seconds [

19].

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) of pain rates the intensity of pain on a ten centrimeters long line, where number 0 represents no pain and number 10 represents excruciating pain [

20].

Anthropometric measurements of chest mobility involve determining the difference between the chest circumference at maximum inspiration and maximum expiration, i.e. chest amplitude. This measurement is taken using a tape measure and is conducted three times, with the resulting amplitude calculated as the average of these values. In our study, the circumferences were measured in the axilla region, mesosternal region (4th rib region) and xiphosternal region (xiphoid process region) [

21]. The average values of the amplitude are 7–10 cm for men and 5–8 cm for women [

22]. Values below 2.5 cm are considered a symptom of reduced chest mobility [

23].

Baseline data were collected before the study started (week 0). Subsequently, data were collected after the completion of each week (week 1 to week 6). Thus, seven datasets were collected for each participant.

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, standard error, median, mode, minimum, maximum and sum) were used for numerical variables (age, height, weight, 6MWT, TUG and anthropometric measurements of chest mobility). The hypothesis was tested by applying non-parametric, paired one-sided Wilcoxon test to compare the baseline dataset against the last week dataset. A significance level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. The only exception was VAS, where the percentage of the value 0 was evaluated and the exact version of McNemar’s test was used to compare the baseline and the last week. Trends are illustrated by line graphs and data distribution in week 0 and week 6 are illustrated by box plot graphs. Statistical processing was performed using FW R-project software (version 4.3.1), while line and box plot graphs were created in the STATISTICA software (version 12).

3. Results

3.1. Participatns

Thirty-five volunteers confirmed their interest in participating in the study. However, only ten participants arrived for the initial data collection (week 0). Unfortunately, two participants discontinued their participation after week 2. Therefore, only eight participants completed the study, compared to the planned number of ten participants. The characteristics of enrolled participants are presented in

Table 1.

3.2.6. MWT

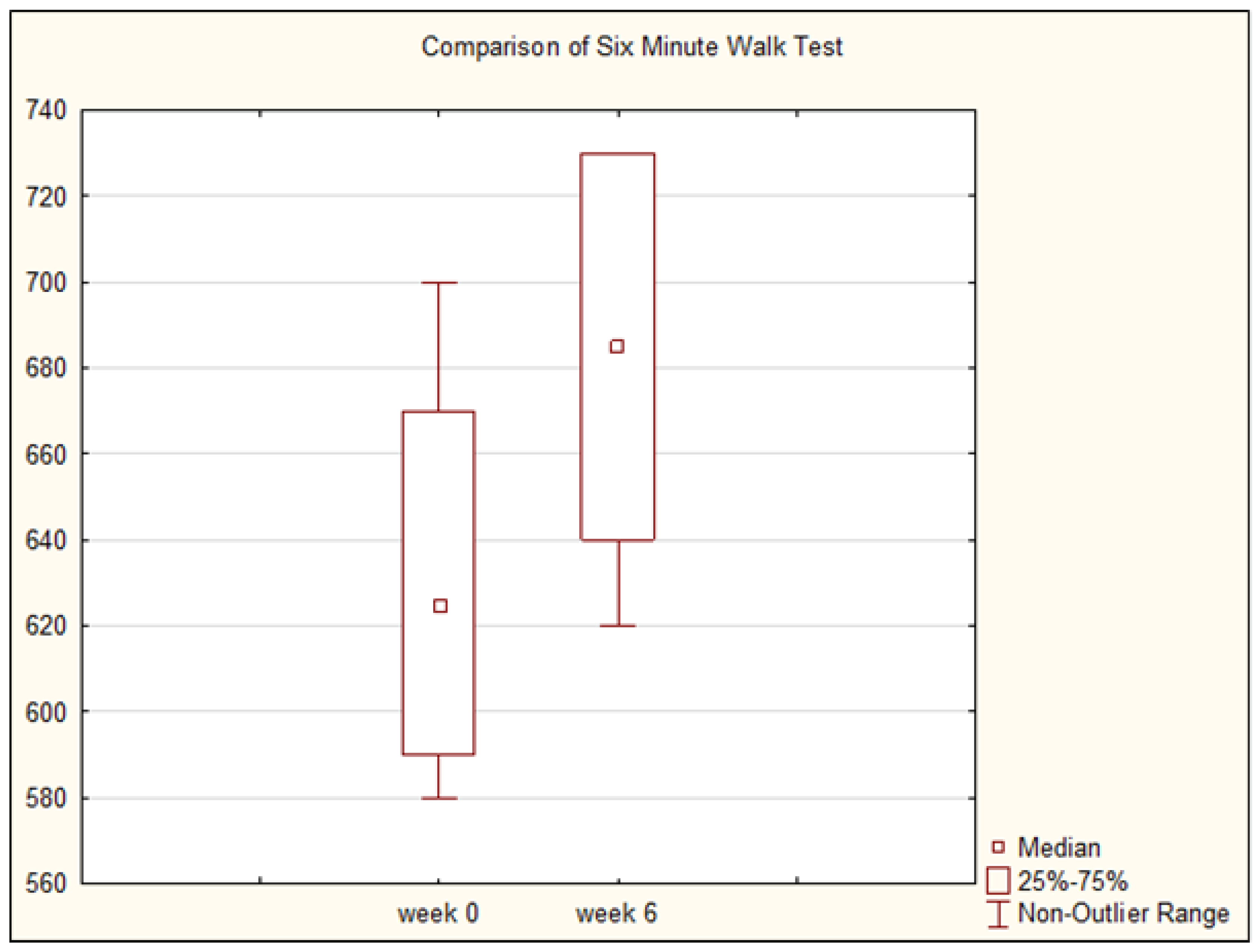

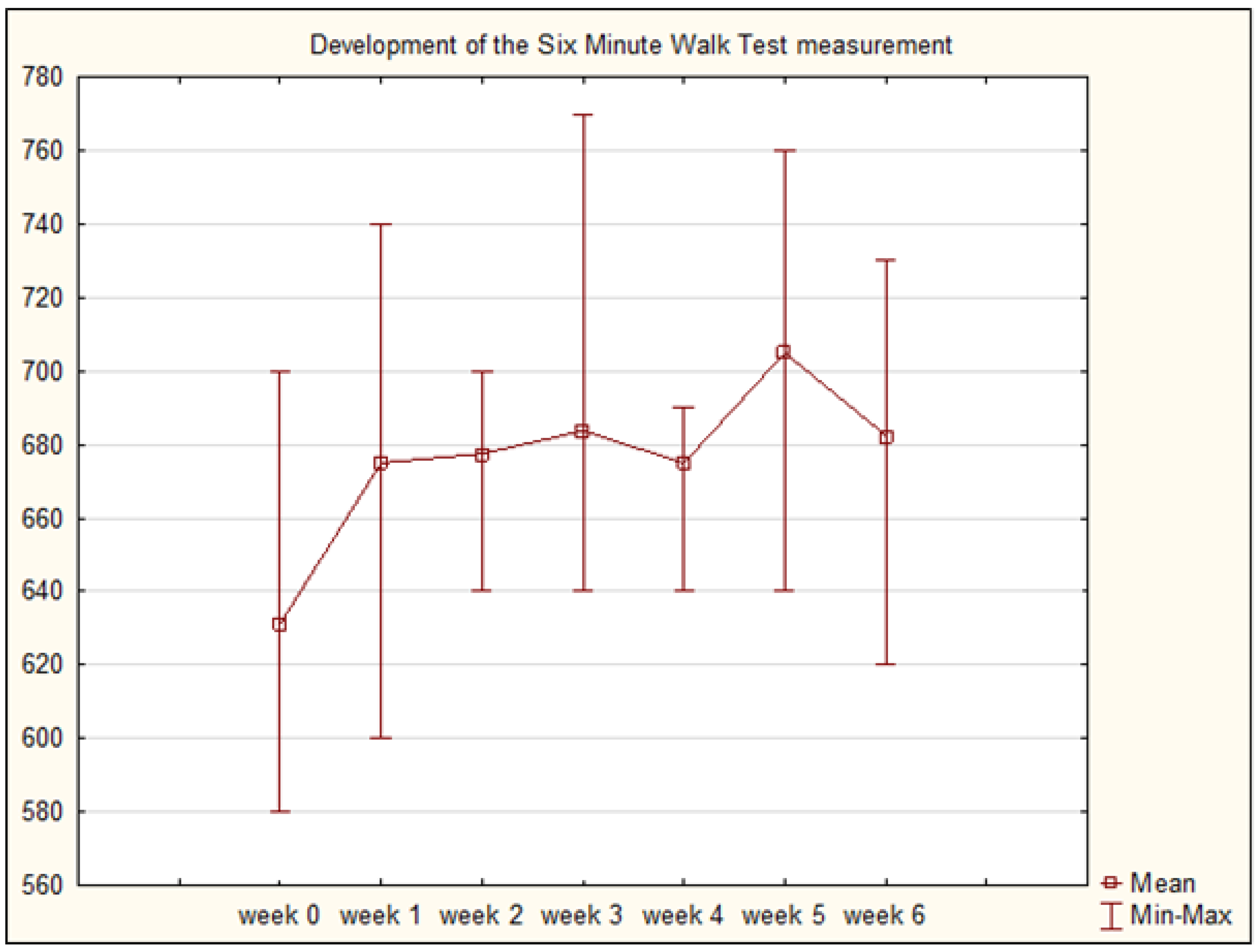

The average distance at the beginning of the study was 631.25 meters. After completing a six-week Nordic walking program, the participants showed an improvement in average distance of 51.25 meters, reaching 682.50 meters (

Table 2). Improvement in 6MWT was found to be statistically significant (p = 0.034).

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 illustrate the difference between week 0 and week 6 and trend of measured values (distances).

3.3. TUG

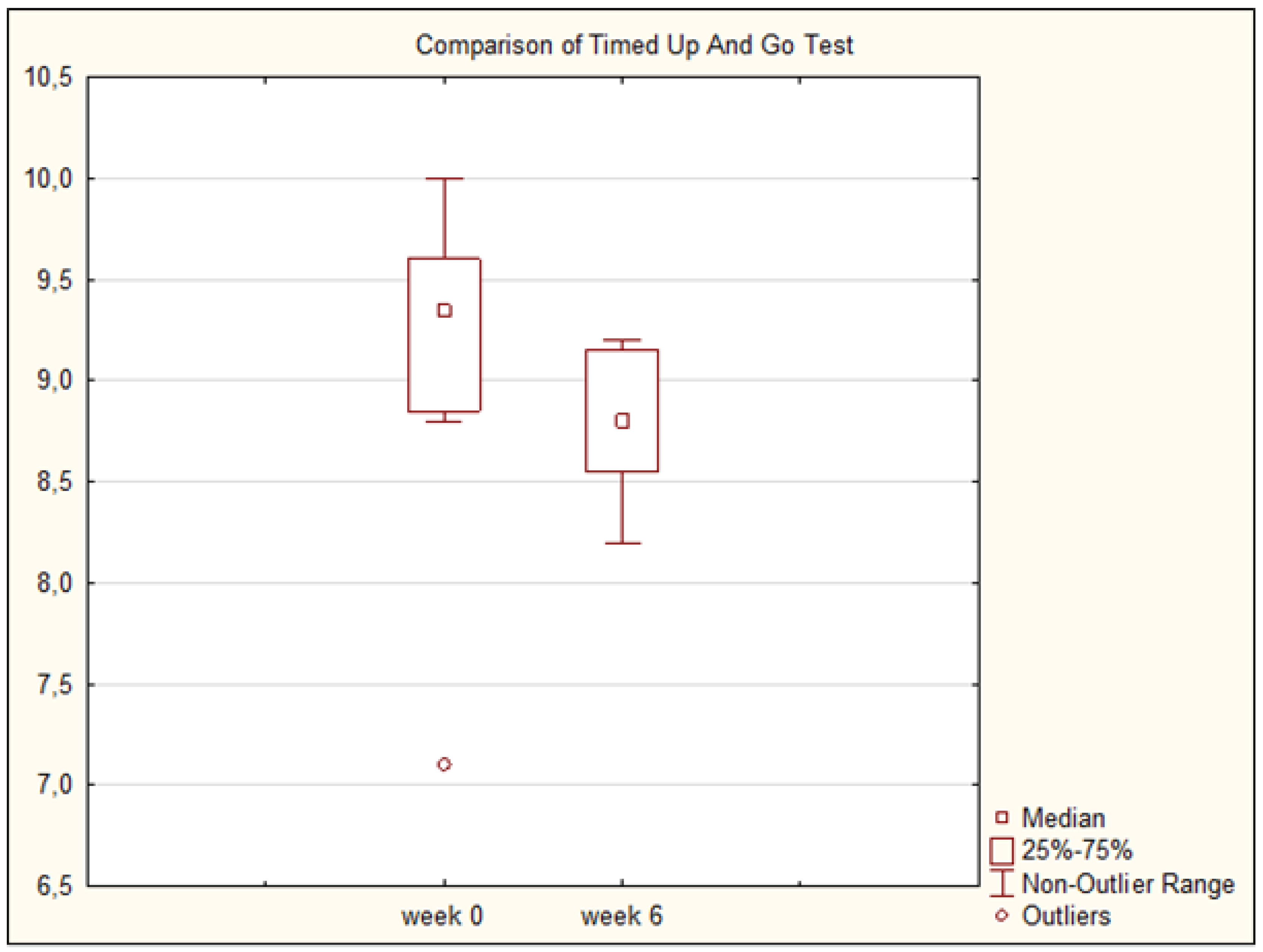

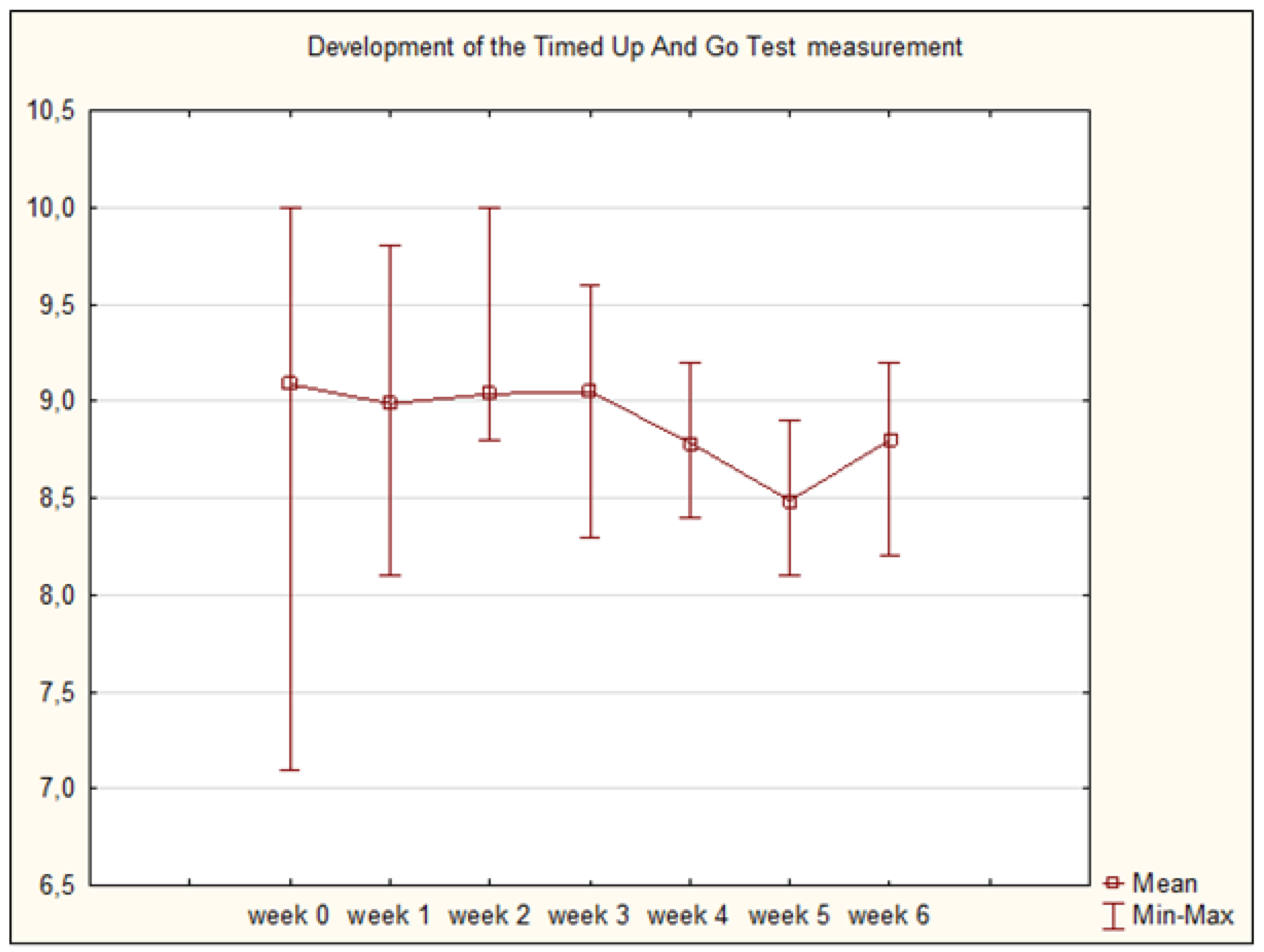

The average time at the beginning of the study was 9.09 seconds. After completing a six-week Nordic walking program, the participants showed a slight improvement in the average time to 8.80 seconds (

Table 3). However, this slight improvement was found to be statistically insignificant (p = 0.191).

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 illustrate the difference between week 0 and week 6 and trend of measured values (times).

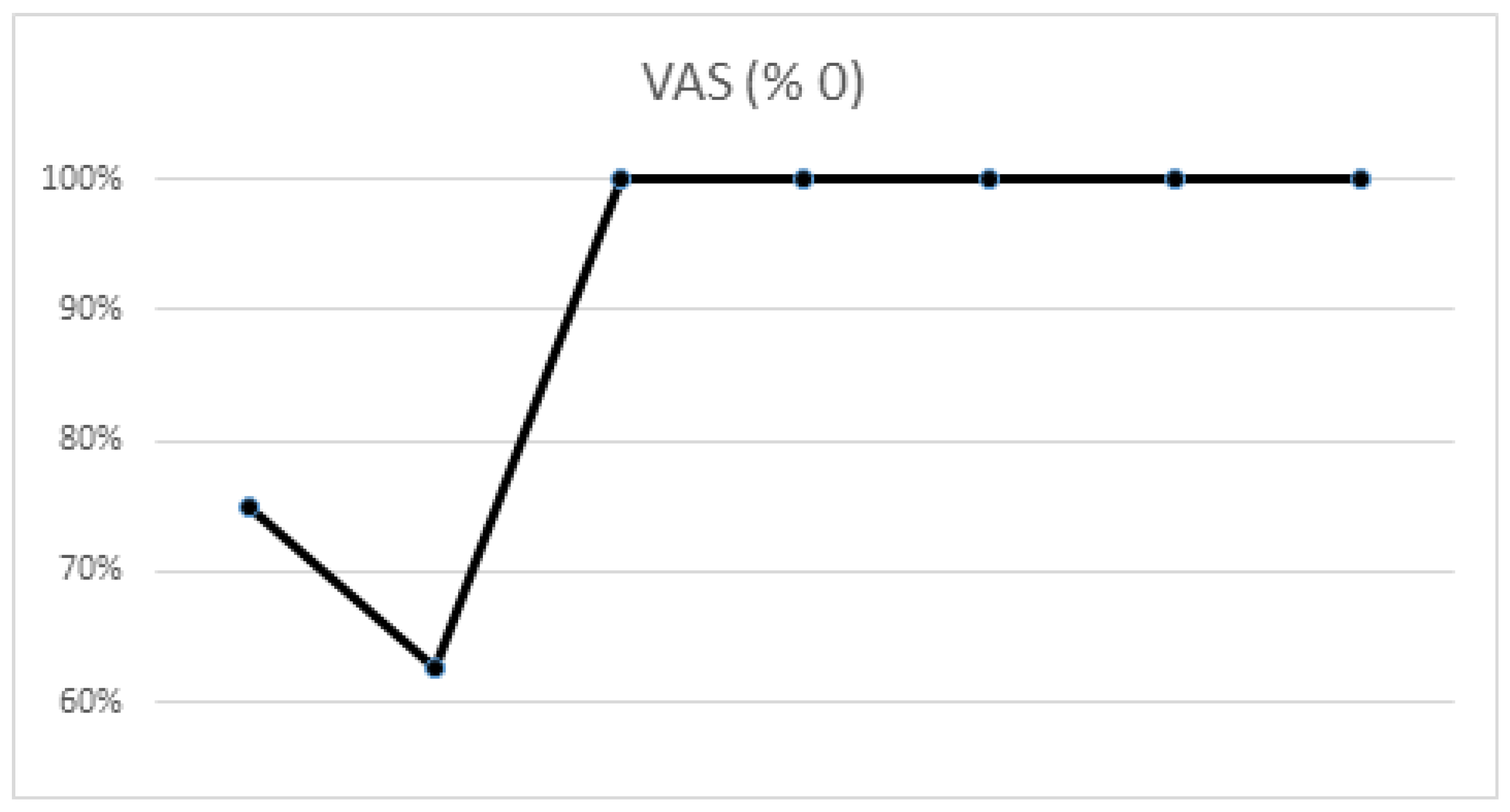

3.4. VAS

There was an insignificant increase (p = 1.000) in the percentage representation of value 0 (i.e., no pain), with 75% of participants reporting a score of 0 before the study, while 100% of participants reported a value of 0 after the study (

Table 4). The turning point came in week 2, after which 100% of participants reported a value of 0 (

Figure 5).

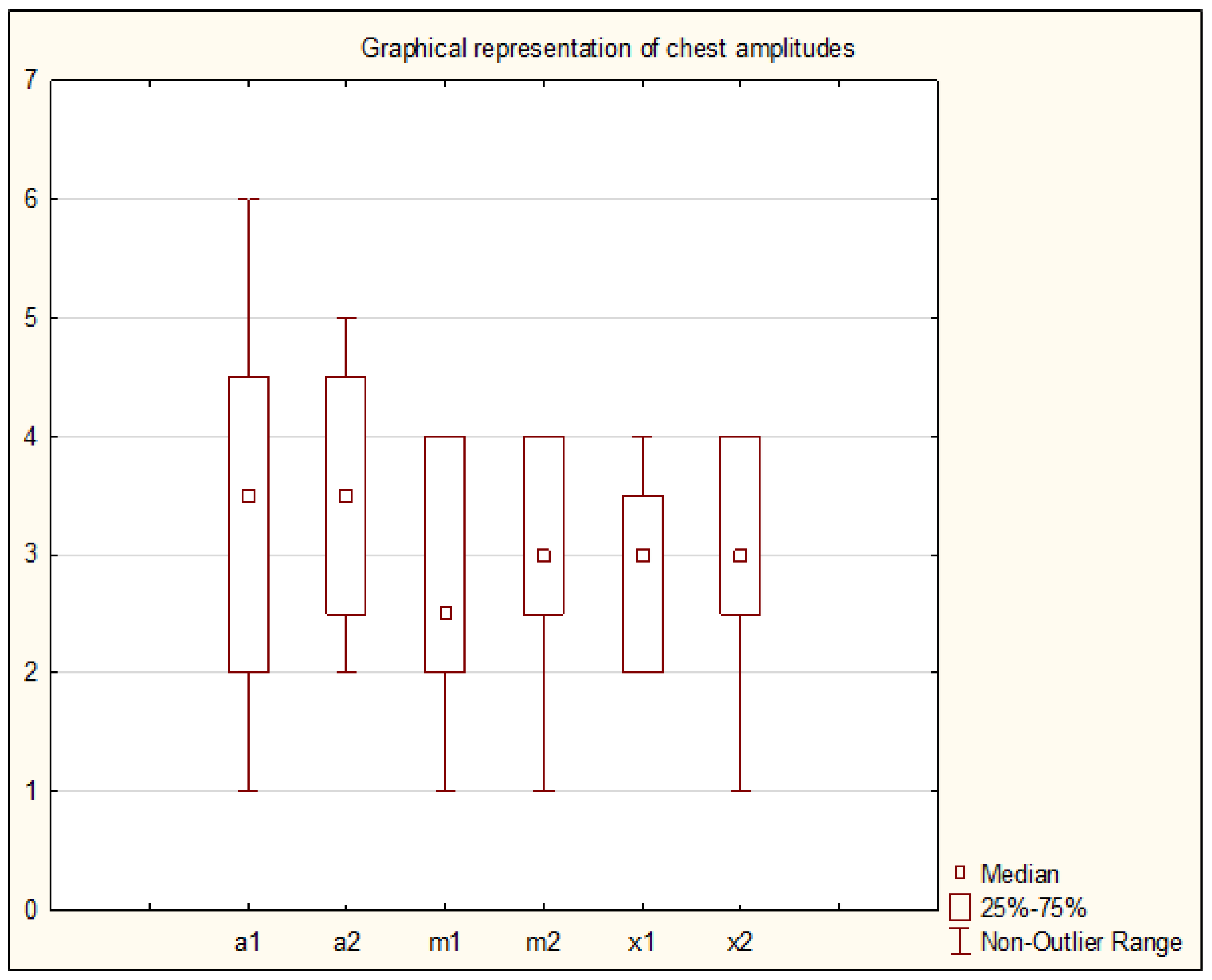

3.5. Anthropometric Measurements of Chest Mobility

The average values of chest mobility amplitudes at the beginning of the study were 3.38 cm, 2.75 cm and 2.88 cm for axilla, mesosternal and xiphosternal, respectively. After completing a six-week Nordic walking program, the participants showed a slight improvement in the average values for chest mobility amplitudes as follows: 3.50 cm, 3.00 cm and 3.00 cm for axilla, mesosternal and xiphosternal, respectively (

Table 5 and

Figure 6). These slight improvements were found to be statistically insignificant (p = 0.412; p = 0.293; p = 0.412).

4. Discussion

4.1. Results

Based on the studies already conducted, we expected improvements in all measured parameters. However, we confirmed our hypothesis only for the 6MWT and VAS results. We observed statistically significant improvement in 6MWT results, with an average improvement of 51.25 meters. This finding is significant and consistent with other studies [

7,

18]. For TUG results, there was also an improvement (decrease in time needed to complete the test), but it was not statistically significant. The likely cause may be the nature of our exercise program, which was at a moderate intensity. TUG primarily focuses on the speed of execution, and it's worth noting that all participants already showed values typical of a healthy population at baseline (twelve seconds or less). Thus, the question arises whether these values need further improvement. Regarding VAS, we recorded a score of 0 (i.e., no pain) in 100% of participants from week 2 onwards. Thus, it can be indirectly concluded that our exercise program led to a reduction in participants' perception of pain, nevertheless this reduction was not statistically significant. A similar result was achieved in a study, where Nordic walking was used in patients with arthralgia [

24]. For chest mobility amplitudes, there were no statistically significant improvements. It should be noted that all participants were at the lower range of physiological chest amplitude, so that the presence of pathologies such as rib or chest joint blockages cannot be excluded. Additionally, it is questionable whether a Nordic walking exercise program can have an effect on increasing chest mobility amplitudes. Such an effect has been observed, but only in the comprehensive therapy where, in addition to Nordic walking, several other types of therapy, e.g. breathing gymnastics with elements of superficial breathing, were used [

25].

Our pilot study of prehabilitation had clearly defined examination and course of exercise program. Thus, we fully agree with other authors [

4,

7] that the content of prehabilitation must be clearly defined before implementation. We consider an individual approach to be absolutely ideal, i.e. each patient should be individually assessed and a completely individual therapy should be designed accordingly. If an individual approach is not feasible, then it is recommended to group patients based on baseline test results and administer the same therapy to all patients within a given category.

4.2. Limits of the Study

Limited sample: Enrolled participants were volunteers from the U3A of UJEP in Usti nad Labem. Due to this limitation, participation was not consistent, resulting in only eight participants completing the study instead of the planned ten. Future studies should aim for a larger number of participants and avoid operating at the minimum sample size to enhance the robustness of the study results.

Tracking of performed self-therapy: Only verbal evaluations by the participants were utilized to monitor the completion of the self-therapy. Consequently, it is not possible to confirm with 100% certainty whether participants actually performed the self-therapy. It would be desirable to incorporate wearable sensors (e.g., smartwatches) along with evaluation software [

26]. However, considering the age of the enrolled participants, it is questionable whether they would be willing to learn and use these technologies, especially if they are unfamiliar with them and do not use them in their daily lives.

The Talk test: We use only verbal evaluation of the target (moderate) intensity. For more accurate measurement, it would be appropriate to use some wearable sensors, e.g. smartwatch or better pulse oximeter.

Lack of control group: This study did not include a control group or another exercise group for comparison of therapy effects. The absence of a control group means that it is not possible to determine whether the outcomes of this study (despite being mostly statistically insignificant) are solely attributable to the Nordic walking exercise program or to other factors.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of this pilot study suggest Nordic walking exercise program may offer some measurable improvements in the functional capacity and quality of life of participants and although Nordic walking is a relatively basic physical activity, it is absolutely essential to monitor this activity accurately and include it in a comprehensive prehabilitation program.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.T. and V.Č.; methodology, K.H.; software, K.H.; validation, O.K., E.B.; investigation, O.K., E.B., A.J. V.K.; resources, K.T.; data curation, K.H., V.K.; writing—original draft preparation, O.K.; writing—review and editing, O.K., V.K.; supervision, V.Č.; project administration, O.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Health Studies UJEP (protocol code 374/19, date of approval: September 2nd, 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 6MWT |

Six Minute Walk Test |

| cm |

centrimeter |

| TUG |

Timed Up and Go Test |

| U3A |

The University of the Third Age |

| UJEP |

Jan Evangelista Purkyny University in Usti nad Labem |

| VAS |

Visual Analogue Scale |

References

- Čechová, Š. Více než 60 procent Čechů má nadváhu, trpí jí až čtvrtina dětí. Obezita způsobuje závažné zdravotní komplikace. Státní zdravotní ústav. Available online: https://szu.cz/aktuality/vice-nez-60-procent-cechu-ma-nadvahu-trpi-ji-az-ctvrtina-deti-obezita-zpusobuje-zavazne-zdravotni-komplikace/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Bobčíková, K.; Macounová, P.; Bužgová, R.; Tomášková, H.; Staňková, A.; Janulková, T.; Mitták, M.; Maďar, R. An assessment of quality of life, health, and disability in patients undergoing lung resection. Kontakt 2023, 25, 4, 307–313. [CrossRef]

- Mazúr, A.; Šrámek, V.; Čundrle, I. Prehabilitation in surgery - narrative review. Anesteziologie & intenzivní medicína 2021, 32, 136–141. [CrossRef]

- West, M.A.; Wischmeyer, P.E.; Grocott, M.P.W. Prehabilitation and Nutritional Support to Improve Perioperative Outcomes. Current Anesthesiology Reports 2017, 7, 340–349. [CrossRef]

- Whittle, J.; Wischmeyer, P.E.; Grocott, M.P.W.; Miller, T.E. Surgical Prehabilitation. Anesthesiology Clinics 2018, 36, 567–580. [CrossRef]

- Bolshinsky, V.; Li M.H.G.; Ismail, H.; Burbury, K.; Riedel, B.; Heriot, A. Multimodal Prehabilitation Programs as a Bundle of Care in Gastrointestinal Cancer Surgery: A Systematic Review. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum 2018, 61, 124–138. [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, Y.; Gondal, U.; Aziz, O. A systematic review of prehabilitation programs in abdominal cancer surgery. International Journal of Surgery 2017, 39, 156–162. [CrossRef]

- Luther, A.; Gabriel, J.; Watson, R.P.; Francis, N.K. The Impact of Total Body Prehabilitation on Post-Operative Outcomes After Major Abdominal Surgery: A Systematic Review. World Journal of Surgery 2018, 42, 2781–2791. [CrossRef]

- Strejcová, B.; Mahrová, A.; Švagrová, K.; Štollová, M.; Teplan, V. The changes in quality of life during the first year after the renal transplantation: The influence of physical activity and nutrition. Kontakt 2014, 16, 249–255. [CrossRef]

- Chloubová, I.; Tóthová, V.; Olišarová, V.; Šedová, L.; Trešlová, M.; Bártlová, S.; Prokešová, R.; Michálková, H. The importance of education on physical activities regarding cardiovascular illnesses. Kontakt 2019, 21, 3–7. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Garrido, A.; Pujol, V.; Roca, R.; Oscar, G.; Launois, P.; Roman, A. Does Nordic walking improve exercise capacity in lung transplant patients? Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 2018, 61, e282. [CrossRef]

- Ochman, M.; Maruszewski, M.; Latos, M.; Jastrzębski, D.; Wojarski, J.; Karolak, W.; Przybyłowski, P.; Zeglen, S. Nordic Walking in Pulmonary Rehabilitation of Patients Referred for Lung Transplantation. Transplantation Proceedings 2018, 50, 2059–2063. [CrossRef]

- Barberan-Garcia, A.; Arbillaga-Etxarri, A.; Gimeno-Santos, E.; Rodríguez, D.A.; Torralba, Y.; Roca, J.; Vilaró, J. Nordic Walking Enhances Oxygen Uptake without Increasing the Rate of Perceived Exertion in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Respiration 2015, 89, 221–225. [CrossRef]

- Rybicki, J.R.; Leszczyńska-Bolewska, B.M.; Grochulska, W.E.; Malina, T.F.; Jaros, A.J.; Samek, K.D.; Baner, A.A.; Kapko, W.S. Oxygen uptake during Nordic walking training in patients rehabilitated after coronary events. Kardiologia Polska 2015, 73, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Girold, S.; Rousseau, J.; Le Gal, M.; Coudeyre, E.; Le Henaff, J. Nordic walking versus walking without poles for reha-bilitation with cardiovascular disease: Randomized controlled trial. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 2017, 60, 223–229. [CrossRef]

- Buchtelová, E.; Lhotská, Z.; Hrach, K.; Tichá, K.; Kvochová, V.; Neckař, P.; Kališko, O. Prehabilitační trénink - testování modelu. Zdravotnické listy 2022, 10, 50–58. https://zl.tnuni.sk/fileadmin/Archiv/2022/2022-10.c.4/ZL_2022_10_4_09_Buchtelova.pdf.

- ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS Statement: Guidelines for the Six-Minute Walk Test. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2002, 166, 111–117. [CrossRef]

- Perera, S.; Mody, S.H.; Woodman, R.C.; Studenski, S.A. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2006, 54, 743–749. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Timed Up & Go (TUG). https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/media/pdfs/steadi-assessment-tug-508.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Delgado, D.A.; Lambert, B.S.; Boutris, N.; McCulloch, P.C.; Robbins, A.B.; Moreno, M.R.; Harris, J.D. Validation of Digital Visual Analog Scale Pain Scoring With a Traditional Paper-based Visual Analog Scale in Adults. JAAOS: Global Research and Reviews 2018, 2, e088. [CrossRef]

- Dylevský, I. Biomedicínská ergonomie. Grada Publishing: Praha, Czech Republic, 2022; p. 167. ISBN 978-80-271-3600-1.

- Isajev, J.; Mojsjuková, L. Průduškové astma: dýchání, masáže, cvičení. Granit: Praha, Czech Republic, 2005; p. 168. ISBN 978-80-7296-042-2.

- Neumannová, K.; Kolek, V. Asthma bronchiale a chronická obstrukční plicní nemoc: možnosti komplexní léčby z pohledu fyzioterapeuta. Mladá fronta: Praha, Czech Republic, 2018; p. 170. ISBN 978-80-204-2617-8.

- Fields, J.; Richardson, A.; Hopkinson, J.; Fenlon, D. Nordic Walking as an Exercise Intervention to Reduce Pain in Women With Aromatase Inhibitor-Associated Arthralgia: A Feasibility Study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2016, 52, 548–559. [CrossRef]

- Ruban, L.; Kochuieva, M.; Rohozhyn, A.; Kochuiev, G.; Tymchenko, H.; Samburg, Y. Complex physical rehabilitation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at a polyclinic stage of treatment. Physiotherapy Quarterly 2019, 27, 11–16. [CrossRef]

- Hannan, A.L.; Harders, M.P.; Hing, W.; Climstein, M.; Coombes, J.S.; Furness, J. Impact of wearable physical activity monitoring devices with exercise prescription or advice in the maintenance phase of cardiac rehabilitation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation 2019, 11, 1–21. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).