1. Introduction

Since the start of the epidemic in 1981, 42.3 million people have died from illnesses related to AIDS, which is the late stage of infection of HIV. [

1] AIDS is an advanced condition related to untreated HIV infection that is diagnosed based on specific AIDS-defining illnesses that are rare in the general population and tend to occur when circulating CD4+ lymphocytes are below <200/mm3 [

2]. There have been advancements in diagnosis and in treatment of HIV, particularly with the development of antiretroviral therapy (ART), which has led to a rise in life expectancy. However, there is no cure and HIV is now considered a chronic disease [

3]. In 2022, 630,000 people died from AIDS-related illnesses worldwide [

1], and HIV/AIDS was the eleventh most common cause of disability-adjusted life-years globally in 2019–the second most common cause for individuals 25–49 years of age, and the ninth most common at 10-24 years of age [

4]. A reduction in lifespan is one strategy to estimate a disease’s impact, although the traditional lifespan approach can be of limited value when the disease can be acquired at different ages. Life years lost (LYL) is a method of estimating disease impact that is calculated based on the age of onset or diagnosis of a condition [

5] to overcome this limitation, and has been developed into an R package [

6]. Average years of life lost (AYLL) describes the average number of LYL across all ages, to represent the number of additional years an individual would be expected to live if not for premature death from their disease versus the general population in their age group ([

7,

8]). This method is particularly valuable for conditions like AIDS, where the age of onset can vary widely.

LYL has previously been applied to cancer [

9], epilepsy [

10], and mental illness [

11], though it has not frequently been used in HIV/AIDS [

12,

13,

14]. We have previously calculated LYL in cohorts of patients with an HIV diagnosis without an AIDS diagnosis versus those with an AIDS diagnosis, regardless of HIV status [

13]. We also calculated LYL in those with an HIV diagnosis regardless of AIDS status [

14] and analyzed the demographic variables in the latter population. Here, we determine the LYL in those with an AIDS diagnosis. We have previously estimated LYL for patients with an HIV diagnosis at the ages of 0, 30, and 60 to be 39, 32, and 14, respectively, in this cohort [

14]. Prior estimates for LYL in HIV/AIDS have been at 46 years lost following diagnosis at age 20 in a study in Iran [

12]; 25 average years of life lost across all ages (AYLL) in a study in Tanzania due to six different illnesses that included HIV/AIDS [

15]; and, in a US study (not including Puerto Rico), 12.8 AYLL for males and 16.5 years for females. In the latter study, LYL for individuals diagnosed with HIV at ages 20, 40, 60, and 80 years was 17.6, 14.1, 10.4, and 6.2 years, respectively, for males, and 24.5, 18.3, 12.1, and 7.3 years, respectively, for females [

16].

LYL related to AIDS diagnosis has been estimated on a still more infrequent basis. A 2014 study estimated the burden of disease due to AIDS in the Brazilian Southern State of Santa Catarina at 257.5 years lost and 331.9 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) per 100,000 total inhabitants, highest in males in the age groups of 30-44 and 45-59 [

17]. A 2015 study in the same region estimated 593.1 DALYs/100,000 inhabitants (780.7 DALYs/100,000 men and 417.1 DALYs/100,000 women) among residents of the city of Tubarao, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, with men aged 30-44 years and women 60-69 years most affected. [

18]. Other studies looked at sociodemographic variables, such as a 2016 descriptive study [

19] that found a difference between males and females who died from AIDS and AIDS-related causes (987 males and 340 females) among youth with secondary education in South Africa between 2009-2011, and a 2022 study analyzing the association of AIDS deaths in females between 2007-2017 in Porto Alegre in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, with race/skin and social vulnerability indicators. The latter study estimated 86.5 years lost/1,000 females, with a higher proportion of deaths among females of White race/skin color (53.4%), but a higher rate of years of life lost among females of Black and mixed race/skin color living in regions with higher risk. [

20]

We have previously demonstrated for HIV patients as a whole that various risk factors, such as poverty and transmission modality, are associated with greater LYL [

13]. Poverty has previously been shown to be associated with decreased life expectancy among different age, gender, and racial/ethnic groups [

21]. Risk factors, including different modes of transmission, have also been associated with differences in life expectancy [

16,

22].

Additionally, we have previously demonstrated reduced life expectancy in HIV patients compared with results from the mainland U.S., such as estimating 20-year-old to have approximately 22 years to live [

14], as compared for example to one study estimating a 21-year-old to have 54.9 years left to live in 2000-2016 [

23]. The earlier timeframe of the mainland U.S. study makes this likely a conservative comparison given that life expectancy has tended to improve over time based on this and other studies.

The estimation of life years lost allows the breakdown of specific contributors or causes of death at different ages of diagnosis, to evaluate the magnitude of each factor, and help implement focused public health programs. Life years lost have not been frequently estimated for HIV/AIDS in general, and the association between LYL specifically after an AIDS diagnosis and sociodemographic variables has not yet been evaluated for the Puerto Rican population per our knowledge. We previously characterized and estimated LYL in the Puerto Rico HIV/AIDS population [

13,

14]]. This included those HIV patients who received a diagnosis of AIDS, which entails an advanced HIV condition that is diagnosed based on specific AIDS-defining illnesses that are rare in the general population and tend to occur when circulating CD4+ lymphocytes are below <200/mm3, and correlates with untreated disease. The objective of the present study is to evaluate whether certain sociodemographic risk factors in patients with AIDS in Puerto Rico from 2000-2020 are associated with lower life expectancy as reflected in life years lost (LYL), as well as to detect trends such as level of poverty over time in this population that occur during this period.

3. Results

Population Characteristics

This study used a data set that included 3,624 patients with a specific date of AIDS diagnosis and a date of death indicated, which was obtained from an initial data set of 24,143 patients with HIV/ AIDS belonging to the eligible metropolitan area (EMA) of San Juan, Puerto Rico, from 2000 to 2020.

The average age of AIDS diagnosis was 42.8 years for men and 41.4 years for women. For transgender patients, it was 40.7 years. In this study, individuals had an average annual income of

$6,534. The majority of individuals (63.2 %) lived at or below 50% of the poverty level. Most individuals (85%) had public health insurance (58% had Medicaid, and the remaining 27% had Medicare/other public insurance). Additionally, 7.86% had private insurance, 2.48% had “other” insurance, 4.5% were uninsured, and 0.06% had no specified insurance information. 47.1% of individuals in this study reported being presumably infected through heterosexual contact, 25.6% through the use of intravenous drugs, and 20.9% through male-to-male sexual contact. Only 1% reported both homosexual contact and intravenous drug use, while 1% reported transfusion, and 2% reported perinatal transmission.

Table 1 presents the demographic information of the patients.

LYL Results

The mean life expectancy of the general population of Puerto Ricans of 80.25 years old (76.7 years old for males and 83.6 years old for females.) is the mean life expectancy assumed by our model as the tau that we used for the maximum age required by the model for both males and females. We also tried varied the maximum tau between 80-99, with insignificant changes in interpretations of the main results.

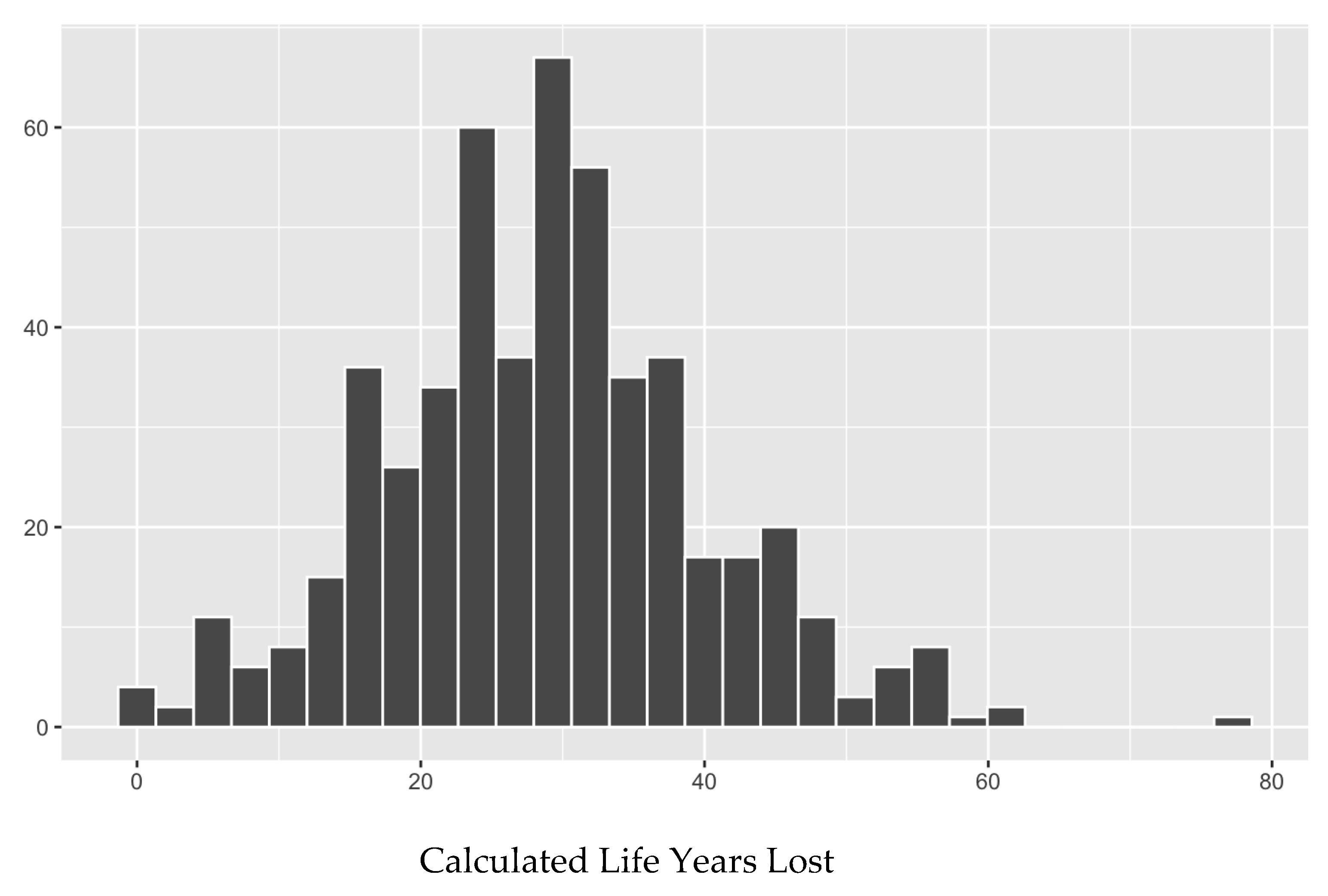

Impact on AIDS Patients

The average expected LYL of all patients who were diagnosed with AIDS and already had a date of death (n = 505, after removing those with a date of death that preceded the date of AIDS diagnosis) is 28.56 overall (27.58-29.54), 54.75 years for the youngest patients (under 20) (35.87-73.63), 42.05 at age 30 (37.87-46.23), and 15.25 at age 60 (12.65-17.85). The average life expectancy across all ages (years of life remaining after the diagnosis) of an AIDS-diagnosed individual is between 5 and 8 years. The life expectancy of individuals with AIDS, irrespective of the age of onset, is many years less than that of the general population. An individual who is diagnosed with AIDS, at the age of 20, 30 and 50, has an expected mean lifespan of another ± 9, 10 and 7 years, respectively. The average life expectancy considering the whole population across all ages is ± 40 years remaining to live for an age-matched cohort.

Poverty Level

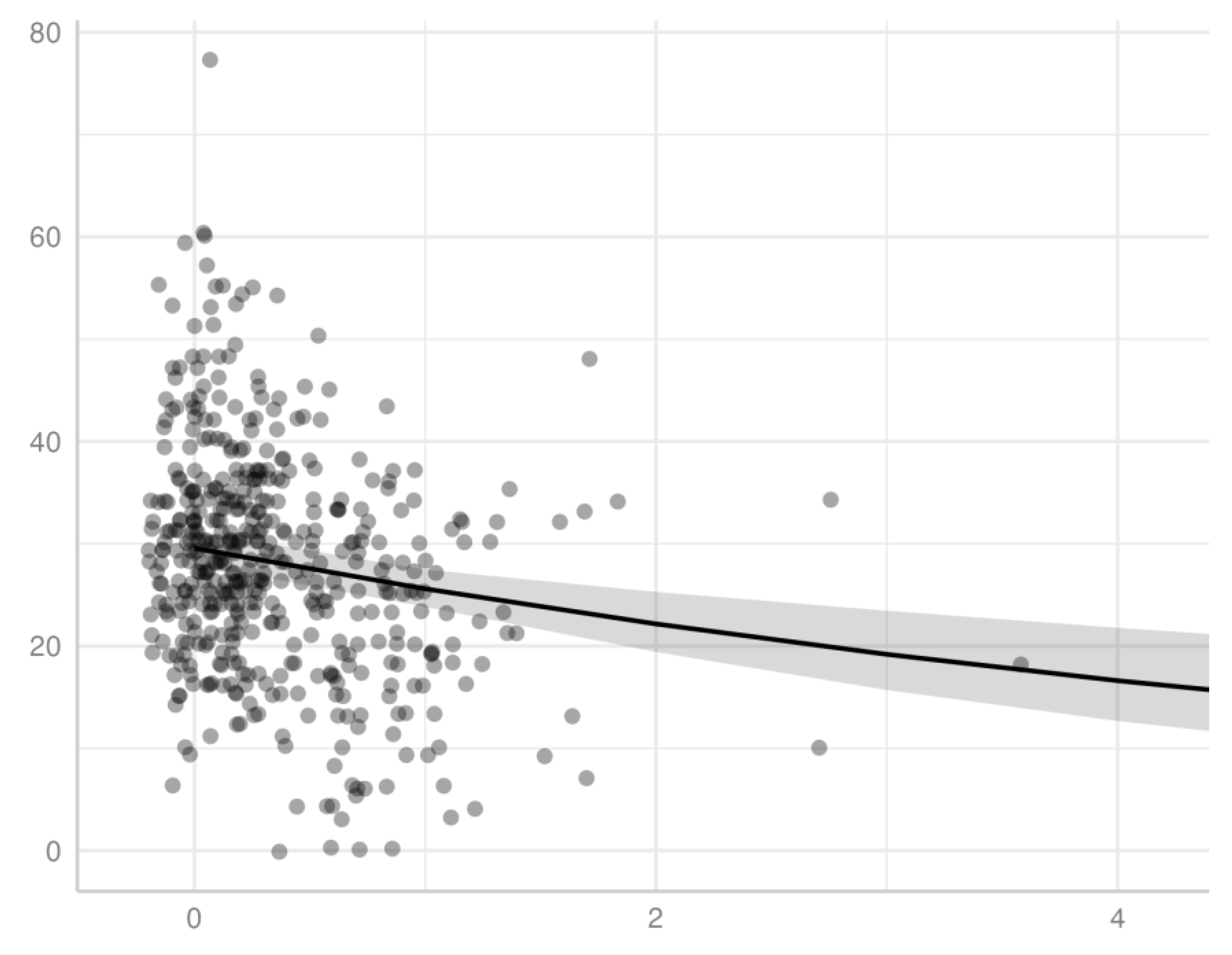

We demonstrated a significant inverse association for patients diagnosed with AIDS between income, measured by percentage of the poverty level, and LYL (p < 0.001), using a gamma distribution model. We observed this association model across all ages of AIDS diagnosis for patients in this study (

Figure 2), as well as within specific age ranges of AIDS diagnosis, specifically for those diagnosed at the age ranges of 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, and 60-69. An individual diagnosed with AIDS with <100% poverty level at the age of 35, 45, and 55 has an expected mean lifespan of approximately 44.4, 51.7, and 59.7, respectively. Of note, the latter set of ranges excludes the extremes of age, which had a smaller sample size and did not generate statistical significance, potentially related to lack of power. Extreme age ranges may also have less predictive accuracy with respect to both LYL as a measure of impact on survival (for example, in an elderly individual with a lower remaining life expectancy) as well as current household income as a measure of socioeconomic status (for example in a child or retired individual with no income.)

Figure 1.

Mean LYL versus poverty level of individuals diagnosed with AIDS. The points represent individuals, and the line represents predicted values of LYL based on a gamma distribution model, including 95% confidence levels (shaded area). The threshold for 100% the federal poverty limit is equal to 1. The x-axis excluded values larger than 3x the poverty level (only 1 data point.).

Figure 1.

Mean LYL versus poverty level of individuals diagnosed with AIDS. The points represent individuals, and the line represents predicted values of LYL based on a gamma distribution model, including 95% confidence levels (shaded area). The threshold for 100% the federal poverty limit is equal to 1. The x-axis excluded values larger than 3x the poverty level (only 1 data point.).

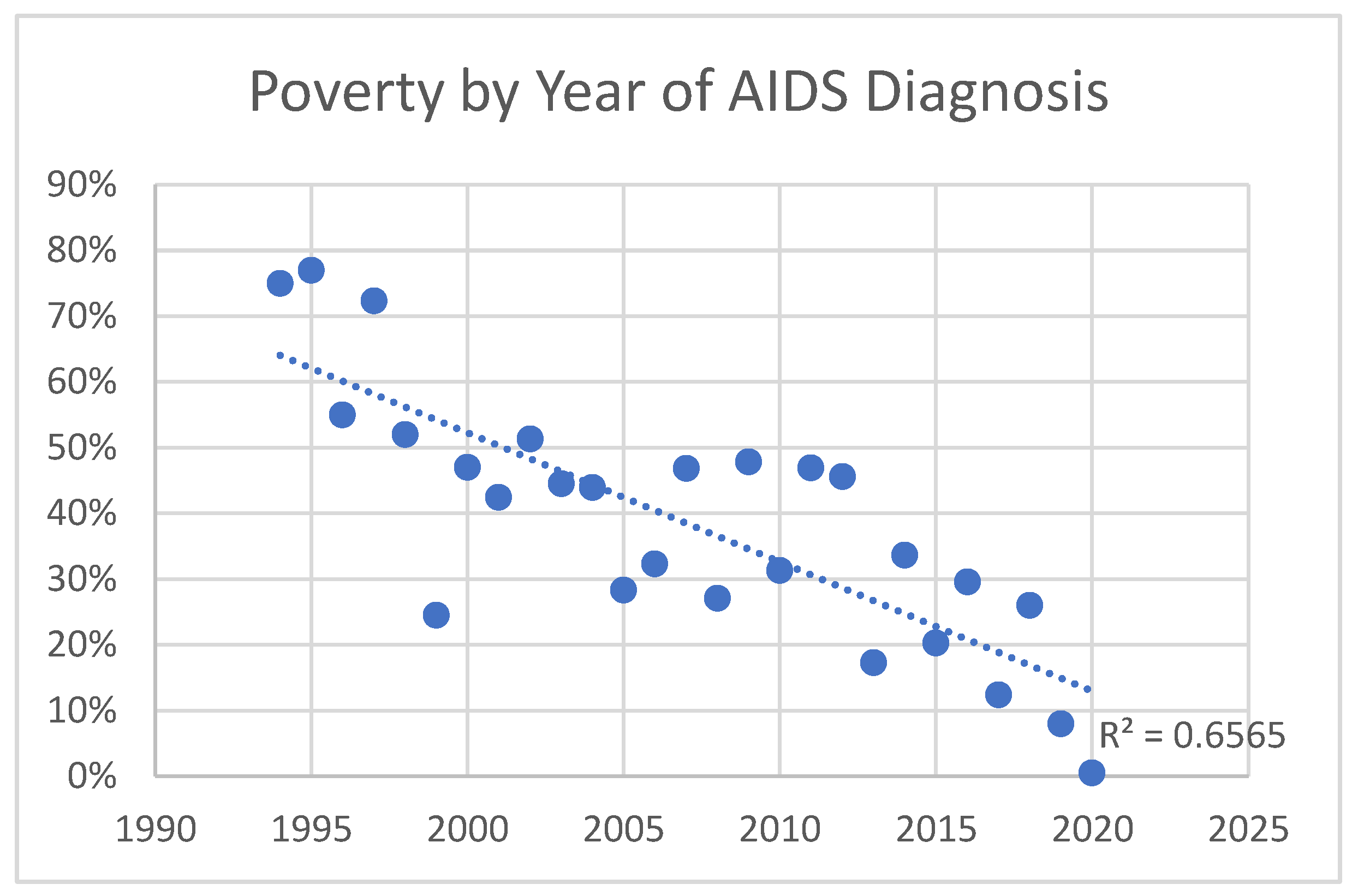

Poverty Level Over Time

Poverty level increased over time in those diagnosed with AIDS, as well as HIV in general. The trend was greater for those with AIDS. Those diagnosed with HIV before 2010 had an average income at 40% of the poverty limit, versus 20% after 2010. (p=0.0003) Those diagnosed with AIDS before 2010 had an average income at 40% of the poverty limit, versus 30% for those diagnosed after 2010. (p=0.03) The trend for those diagnosed <1990, 1990-2000, 2000-2010, and 2010-2020 was 40%, 40%, 30%, and 20%, respectively, for HIV, and 170%, 50%, 40%, and 30% for AIDS. This indicates greater levels of poverty for those diagnosed with HIV and AIDS over time, which is more pronounced in those with AIDS. Thus, economic disparity has increased with AIDS in particular becoming more and more a disease of the poor (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Poverty by year of HIV diagnosis: Linear regression of level of poverty (by percentage of poverty limit) of individuals diagnosed with HIV as a function of year of diagnosis.

Figure 2.

Poverty by year of HIV diagnosis: Linear regression of level of poverty (by percentage of poverty limit) of individuals diagnosed with HIV as a function of year of diagnosis.

Figure 3.

Poverty by year of AIDS diagnosis: Linear regression of level of poverty (by percentage of poverty limit) of individuals diagnosed with AIDS as a function of year of diagnosis.

Figure 3.

Poverty by year of AIDS diagnosis: Linear regression of level of poverty (by percentage of poverty limit) of individuals diagnosed with AIDS as a function of year of diagnosis.

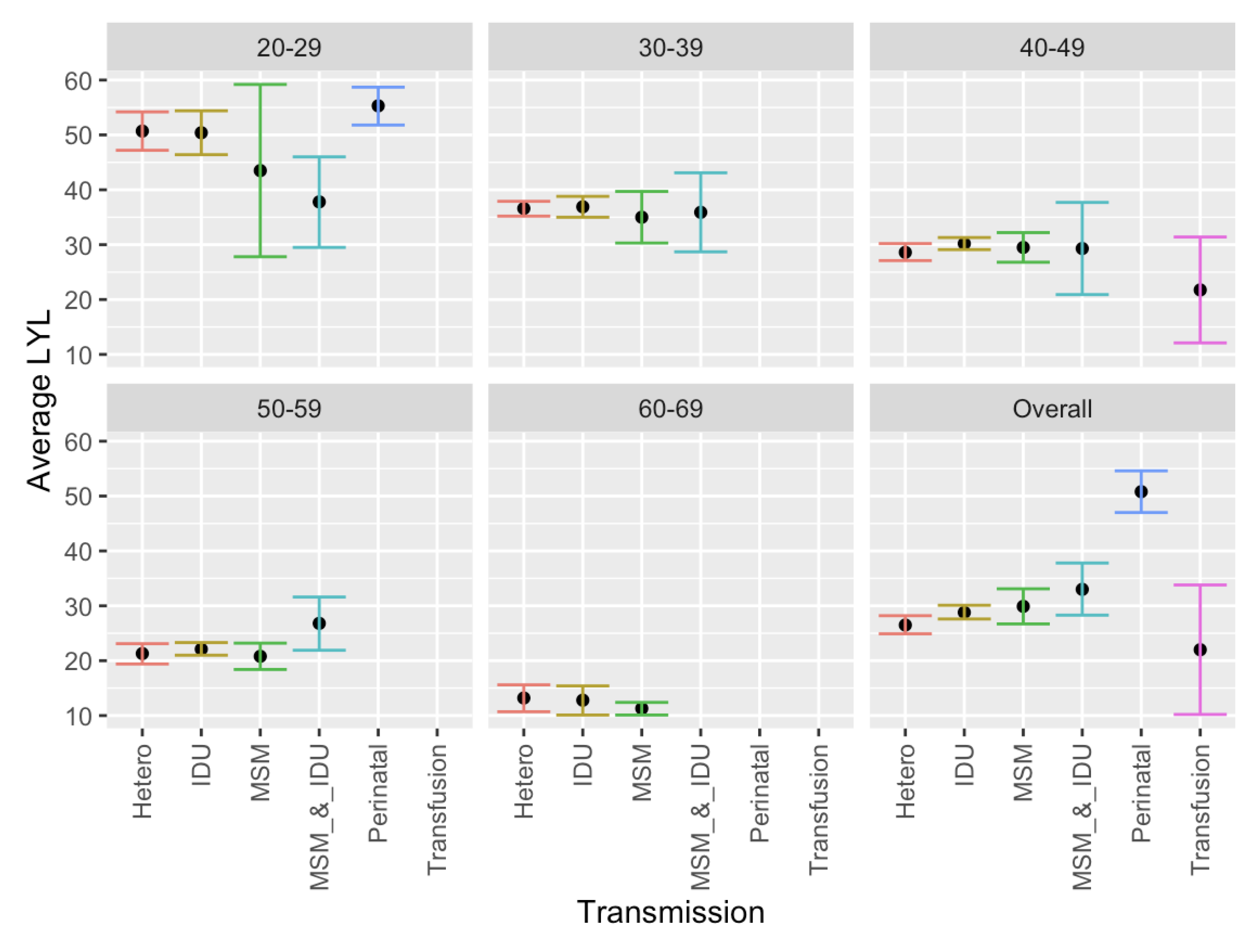

Mode of Transmission

Significantly greater LYL were found across all ages of patients diagnosed with AIDS with perinatal transmission compared to other modes of transmission, and greater LYL were found with IDU and MSM combined compared with heterosexual contact. Other differences were observed within specific age groups. Specifically, in the age group 20-29, IDU alone had greater LYL than IDU and MSM combined. (

Figure 4). However, as a general pattern LYL was generally similar among transmission methods within a given group age category.

Medical Insurance

There was no significant difference found between insurance categories for LYL when calculated across all ages for AIDS patients in this study. Although greater LYL were found in those with no insurance (34.6) versus those with insurance (29.5), the difference was not significant (p = 0.13).

Among individuals with age range of diagnosis between 40-49, however, we did demonstrate significantly greater LYL were found in those with no insurance versus with insurance (34.3 versus 29.2, respectively, p = 0.04.) All age groups exhibited this general trend, but it was only significant in the 40-49 age group, which also included the greatest number of patients (n=179 with insurance, 7 without). Among the age group of 40-49 years, those with no insurance also had significantly greater LYL than those with public insurance or Medicaid specifically. No significant difference in LYL was observed between public versus private insurance in any age group, nor overall. We also found no significant difference between specific types of public insurance (e.g., Medicaid versus Medicare or other public insurance.)

Gender

We found no association with gender, with approximately equal LYL found overall, and within all age groups between males and females with AIDS. This was also previously found to be the case with males and females with HIV generally. [

14]. Overall, patients lost a total of 28.6 years (28.4 ± 1.2 for males, and 28.9 ± 1.8 for females.) Transgender patients and those who refused to answer the question of gender tended to have greater AYLL, but these were few in number (n=1 and 1, respectively). In general, as we previously found for HIV/AIDS patients ([

13,

14]), number of life years lost decreased with increased age at AIDS diagnosis. Of note, our use of a Gaussian distribution for comparison of LYL is justified, as LYL values followed a normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilks test of normality, p >0.05; see

Figure 5, below.)

Trends Over Time in AIDS Patients

Over the years of this study, AIDS diagnoses were made on average at a greater age in later years compared with earlier years of this data set, and was also at a greater age than for HIV (42.6 ± 1.1 prior to 2010 versus 49.6 after 2010 ±1.6 for AIDS diagnoses, versus 38.3 ± 0.7 prior to 2010 versus 48.3 ± 1.8 after 2010 for HIV diagnosis). Additionally, deaths occurred on average at a higher age during later years (e.g., recorded deaths in this population of HIV patients tended to occur on average between 42-50 years of age through 2012, then between 51-60 from 2013-2022). Diagnoses themselves initially increased and then decreased while deaths increased. The proportion of AIDS to HIV diagnoses increased over time. As noted above, poverty level in those diagnosed with AIDS trended to increased poverty over time, suggesting growing disproportionate affecting of those without means.

4. Discussion

Various demographic factors are associated with LYL among AIDS patients. Age of diagnosis carries an association with LYL, as previously demonstrated among HIV patients [

14], as expected, given there are fewer years to lose with age. A newborn diagnosed with AIDS is likely to lose approximately 40 years of life, while a 50-year-old is expected to lose closer to 20 years of life. This trend is consistent with other studies estimating LYL in the United States ([

16]). AIDS diagnoses are associated with greater LYL than HIV diagnoses, despite generally occurring at a later age. On average across all ages, those diagnosed with AIDS had 5-8 years left to live, versus those diagnosed with HIV, who had 12-14 years left. Compared to the average 31.67 life years lost following HIV diagnosis at age 30 [

13], those diagnosed with AIDS at age 30 lost 42.05. Greater LYL for AIDS vs. HIV patients overall were also exhibited within the most impoverished segments of the population, where those with AIDS below 100% of the poverty level at the age of 35 and 45 had an expected mean lifespan of approximately 44.4 and 51.7 respectively, versus the HIV population overall below 100% of the poverty level with an expected mean lifespan of 51.2 ± 2.8 and 56.2 ± 2.5 years, respectively [

14]. Diagnosis at later stages of disease may allow for less control of the disease and greater LYL that result. This finding is consistent with prior findings looking at those with HIV who never developed AIDS versus all those who developed AIDS [

13], and also consistent with previous results in 2016 [

16] indicating that those with late-stage disease at diagnosis (stage 3, i.e., AIDS) had a life expectancy that was, on average, 6.6 years lower than that for persons with HIV who never received a diagnosis of AIDS (stage 3 HIV). This indicates poorer outcomes with later diagnosis and more advanced/uncontrolled disease. 5.9 million people did not know they were living with HIV in 2021, per UNAIDS data [

1], signifying the prevalence of those who are not aware that they were infected initially and are at risk of progressing to later stages of the disease before diagnosis and treatment.

Furthermore, certain risk factors are associated with increased mortality and trends associated this. We noted not only a significant association with poverty level, where poverty is associated with greater LYL, but that AIDS diagnoses have tended to occur in poorer populations over time. This signifies that this is becoming more and more a disease of the poor over time, particularly as treatments such as ART have been available to reduce, if not eliminate, the increased mortality in this population. This is further highlighted by the more pronounced trend associated with AIDS diagnoses versus HIV, suggesting that those who are diagnosed late or are found to be already be progressed AIDS when they are first discovered to be HIV positive tend to be those with less access to healthcare resources and in more underprivileged segments of society, even when as a whole our population tended to have high levels of poverty.

Certain modes of transmission were also associated with greater LYL than others. Although. potentially expected given the association with age, significantly greater AYLL were found following perinatal transmission compared with other modes of transmission. Greater LYL were also found in the IDU and MSM combined group versus heterosexual contact for patients overall, which was significant across patients of all ages combined, though not significant within any age category, likely due to lower power within the individual age categories. The greater years lost with IDU and MSM likely relate to rates of transmissibility of the virus and other infections with intravenous injection and male-to-male sexual contact, and/or association with risky behaviors and other risk factors such as lower socioeconomic status in the injection drug group. It is also hard to know how the disease was transmitted when multiple modes of transmission are possible. In addition, we are assuming accurate reporting of sexual behavior represented in the data set, despite the stigma still associated with varying sexual behaviors that may reduce this accuracy [

30]. Moreover, acceptable social behavior and associated stigma may also vary among age groups.

We found greater LYL in individuals without insurance versus those with insurance across all age groups, although this difference was only significant in the age range of 40-49 years. This age range had the highest number of patients and thus greater power. Other factors could also play a role, such as the fact that this age group may have been more likely to have insurance tied to employment, versus children or young adults, whose insurance may be through the parents, school, or another entity, or older patients who are eligible for Medicare. No significant difference in LYL was detected between public versus private insurance in any age groups, which may be due to no actual difference, or due to inadequate reporting or lack of power leading to a type II error. This is interesting since U.S. Medicaid insurance has previously been shown not to be equivalent in services to private insurance [

31]. Of note, we have also observed the above trends concerning insurance in our prior analysis involving HIV patients as a whole, with or without AIDS [

14].

Many of our results are generally consistent with prior studies. Poverty has been associated with lower life expectancy in different age, gender, and racial/ethnic groups [

17], and socioeconomic, racial, and geographic disparities in HIV/AIDS have persisted with higher HIV/AIDS mortality in more socioeconomically deprived groups [

32]. Transmission/risk factor categories have also been analyzed, with the MSM category being found to have a longer life expectancy than other groups in some studies [

16,

18], though we did not detect this trend. We also did not detect gender differences in this study on AIDS patients, nor in prior analyses on HIV patients as a whole ([

13,

14]). However, other studies did find gender differences with regard to AIDS life expectancy specifically ([

13,

19,

20]), as well as HIV generally in one study [

23] where it was also found in the mainland US that adults with HIV have similar life expectancy to the general population, which differs with our results in Puerto Rico. This difference does not appear to be related to sample size but instead appears to be reflective of our demographic in Puerto Rico, as our study was adequately powered and demonstrated nearly identical LYL between genders as a whole and across all age groups.

Our study is limited in that the sample sizes are unequal among ages, as the number of newborns, youth, and those aged 60 or above diagnosed with AIDS was small. There was also only one transgender patient in this study population. Additionally, the deaths reported during the study period by the San Juan Eligible Metropolitan Area (EMA) were not matched with the Puerto Rico Demographic Registry. Moreover, the data for the San Juan Eligible Metropolitan Area (EMA) does not include people who have been tested anonymously or people infected with HIV/AIDS who were not tested.

Currently, another limitation is in the ability of our estimated values for LYL to be compared with prior studies, given the lack of prior studies using the same time frames, methods, and populations. For example, few studies include Puerto Rico (e.g., a 2016 U.S. study [

16] and a 2010 U.S. study [

29]) and therefore will likely produce different results due to the different population and access to care in the mainland United States versus Puerto Rico, in addition to different time frames and methods. Additionally, methods may vary (e.g., using a life table from a different year). The use of more recent data may also yield different results, with mortality potentially improved due to developments in treatment [

16] that can help improve life expectancy, though not without co-morbidities [

23]. However, HIV mortality in the United States mainland [

23] is substantially different from that in Puerto Rico, likely reflective of socioeconomic, racial, and geographic disparities [

32]. Nonetheless, caution is needed in comparing different studies with different methods that may estimate different quantities, and researchers should consider the purpose of the research and the type of available data when deciding among methods to estimate LYL [

7].

Data limitations also exist, such as restrictions in categorization or limitations in knowledge to assign categories. For example, it may be challenging to determine with certainty the mode of transmission, particularly when more than one potential mode or risk factor exists. We combined MSM and IDU but did not include other combinations. The combined MSM and IDU group also reduced the number of patients in the individual MSM and IDU groups because we did not include individuals in more than one overlapping group, although the number in this combined group was relatively small.

In conclusion, we estimated average years of life lost to evaluate the impact of an AIDS diagnosis in Puerto Rico and evaluated associated risk factors. The number of life years lost (LYL) in AIDS patients is related to age of onset as well as to insurance/no insurance status, poverty level, and transmission mode, but not male versus female gender, and AIDS is becoming more of a disease of the poor with time. Additionally, those with AIDS have fewer years of life to live than those with HIV, despite AIDS being diagnosed later than HIV and an inverse association with age and LYL. This study has important implications regarding sociodemographic disparities in HIV/AIDS mortality.