1. Introduction

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) continues to pose a significant threat in both healthcare and community settings. The infections caused by MRSA range from superficial skin lesions to life-threatening conditions such as bacteremia, endocarditis, pneumonia, and osteomyelitis (Lee et al., 2018; Turner et al., 2019). Globally, MRSA accounts for high morbidity and mortality rates, creating substantial healthcare costs and socio-economic burdens (Tong et al., 2015; Hassoun et al., 2017). The diminishing effectiveness of conventional antibiotics, coupled with a stagnant development pipeline, underscores the urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies (Magana et al., 2020).

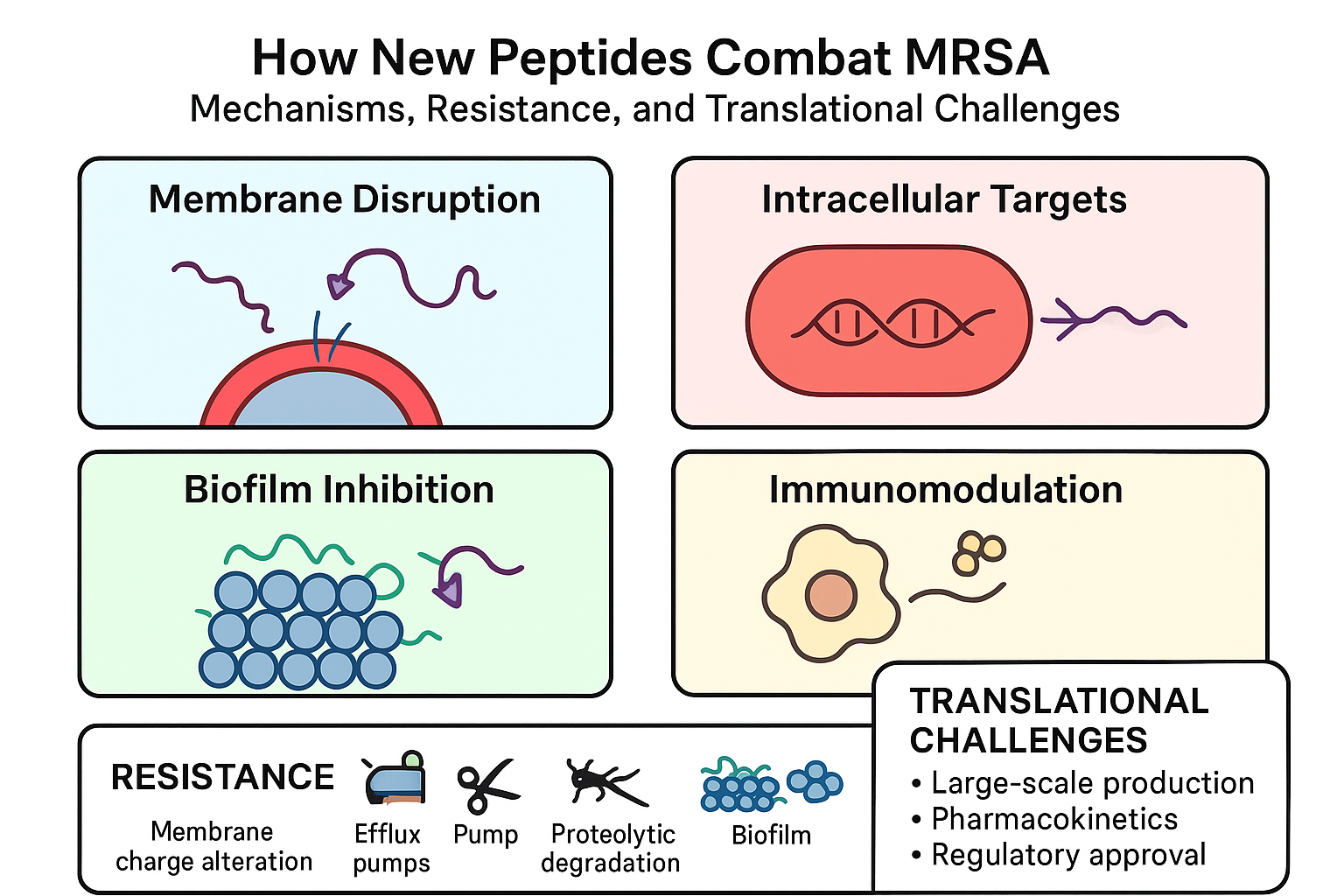

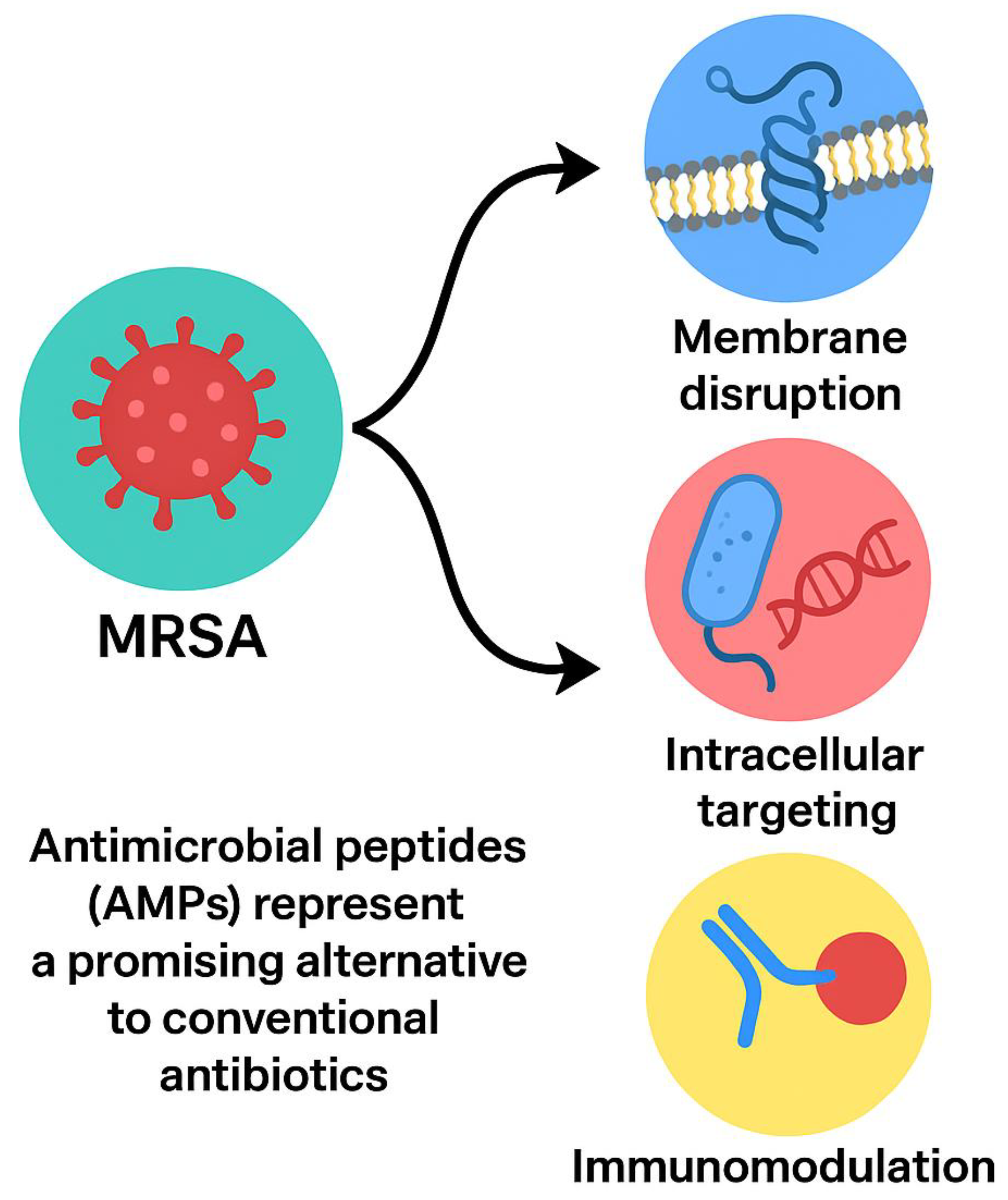

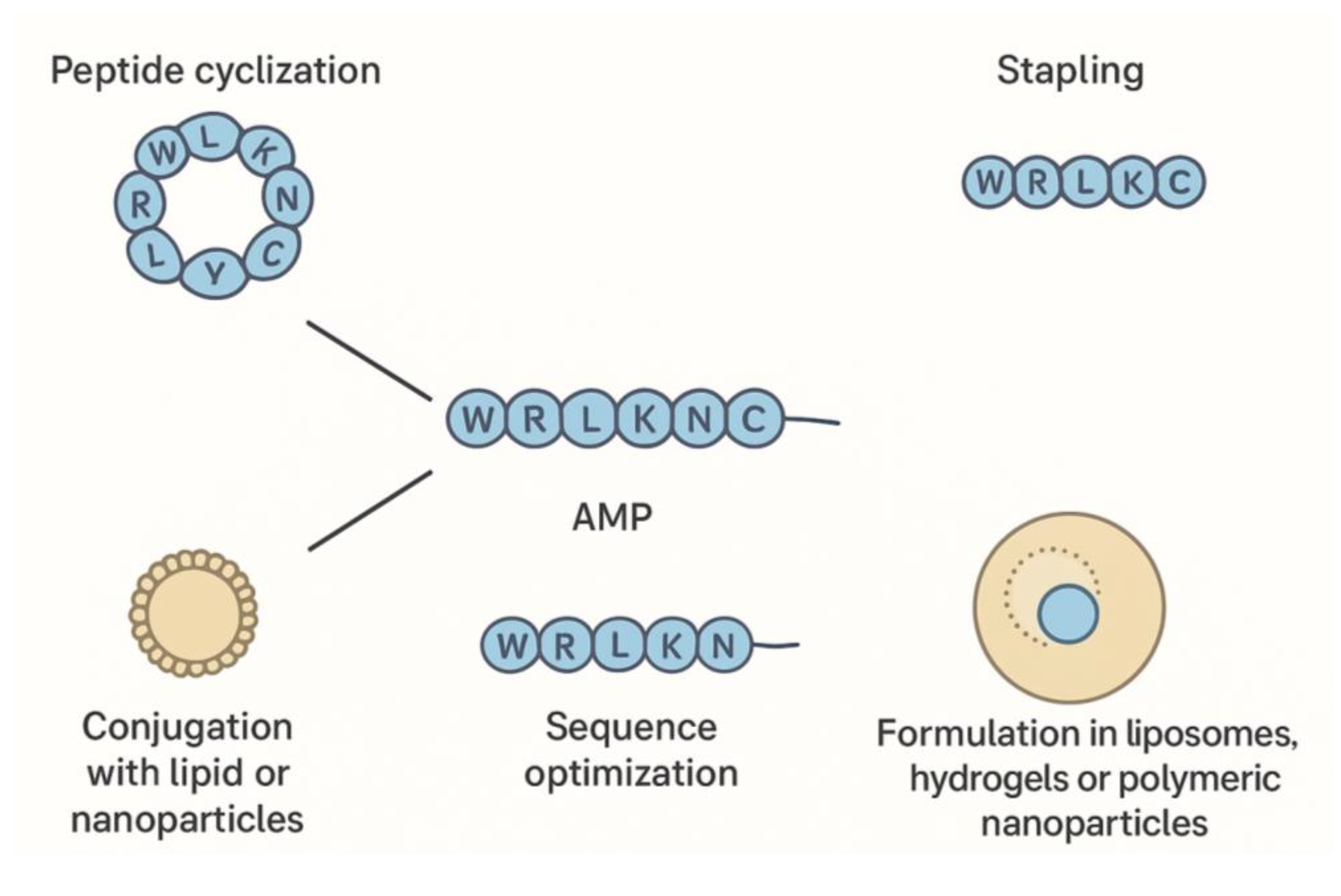

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), small cationic molecules present in a wide range of organisms, provide a promising alternative to traditional antibiotics. Unlike antibiotics that often target a single bacterial pathway, AMPs exert multi-faceted actions, including membrane disruption, inhibition of intracellular targets, interference with biofilm formation, and modulation of host immune responses (Mahlapuu et al., 2021; da Cunha et al., 2022). This broad-spectrum activity reduces the likelihood of resistance development. Advances in peptide engineering, such as cyclization, stapling, and conjugation with lipid or nanoparticle carriers, further enhance stability, potency, and specificity (Huan et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). This review synthesizes the current knowledge on MRSA-targeting peptides, focusing on mechanisms of action, resistance circumvention, formulation strategies, translational challenges, and future directions.

2. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in MRSA

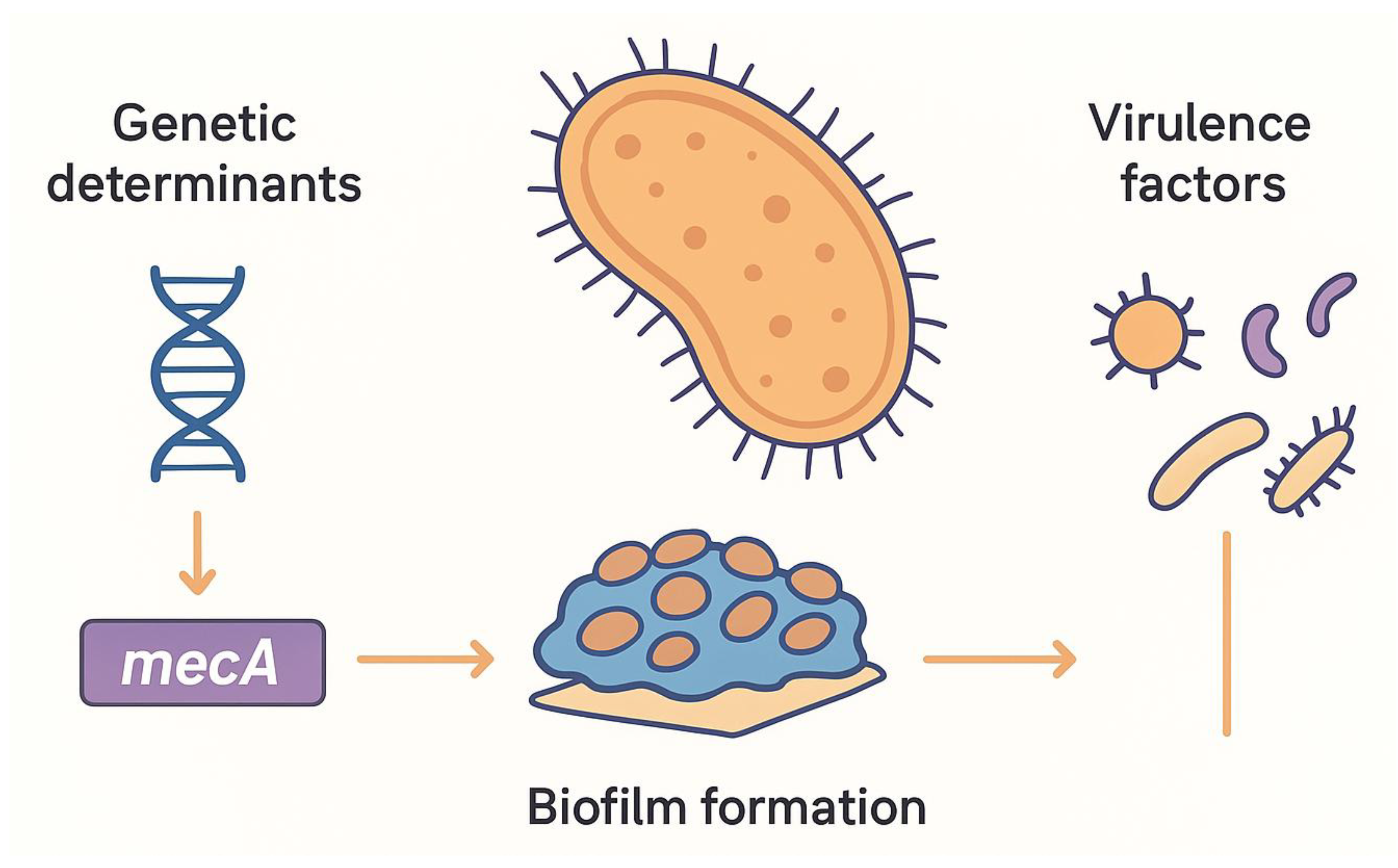

MRSA’s remarkable resilience stems from its diverse resistance mechanisms. The acquisition of the mecA gene, encoding an altered penicillin-binding protein (PBP2a), is central to methicillin resistance, allowing cell wall synthesis in the presence of β-lactams (Hartman & Tomasz, 1984; Peacock & Paterson, 2015). Additionally, the mecC gene, detected in both clinical and zoonotic isolates, broadens the genetic basis of resistance (Shore et al., 2011). Resistance to other antibiotic classes is mediated by multiple pathways: erm genes confer MLSB resistance, aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes target aminoglycosides, tetK/tetM efflux or ribosomal protection confers tetracycline resistance, and gyrA/parC mutations reduce fluoroquinolone susceptibility (Chambers & DeLeo, 2009; Hooper, 2001).

Biofilm formation is another critical factor in MRSA pathogenicity. Within these biofilms, bacterial cells are embedded in an extracellular matrix that reduces metabolic activity, impedes antibiotic penetration, and facilitates horizontal gene transfer. This structural complexity contributes to chronic infections and heightened antimicrobial tolerance (Otto, 2013). Additionally, MRSA expresses a variety of virulence factors, including surface adhesins, α-toxin, and Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), which further enhance pathogenicity and complicate treatment (Löffler & Tuchscherr, 2017). Collectively, these mechanisms—genetic resistance, biofilm formation, and virulence factor expression—underlie the limited success of conventional antibiotics and underscore the urgent need for alternative therapeutic strategies (

Figure 1).

3. Antimicrobial Peptides as Emerging Therapeutics

AMPs are typically 10–50 amino acid residues, cationic, and amphipathic, enabling strong interactions with negatively charged bacterial membranes (Zasloff, 2002). Their primary mechanism involves membrane disruption, causing rapid bacterial death and minimizing resistance development (Hancock & Sahl, 2006). Certain AMPs penetrate bacterial cells, inhibiting DNA, RNA, or protein synthesis, while others prevent biofilm formation or disrupt established biofilms (Otto, 2013). Moreover, AMPs can modulate host immune responses, enhancing chemotaxis, promoting wound healing, and attenuating excessive inflammation (Mahlapuu et al., 2016). As illustrated in

Figure 2, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are typically 10–50 amino acid residues, cationic, and amphipathic, enabling strong interactions with negatively charged bacterial membranes. Their primary mechanisms include membrane disruption, inhibition of intracellular targets, prevention or disruption of biofilms, and modulation of host immune responses.

AMPs are ubiquitously produced across different species. Vertebrates generate defensins and cathelicidins; invertebrates produce cecropins and tachyplesins; plants synthesize thionins and defensin-like peptides; microorganisms, particularly lactic acid bacteria, produce bacteriocins. Despite structural diversity, common motifs enable antimicrobial and immunomodulatory functions, with structures including α-helices, β-sheets stabilized by disulfide bonds, proline-rich extended chains, and cyclic peptides (Mansour et al., 2014).

The advantages of AMPs over conventional antibiotics include rapid action, multi-target activity, efficacy against multidrug-resistant pathogens, and synergistic potential with antibiotics. Challenges include proteolytic degradation, cytotoxicity, and high production costs (Mahlapuu et al., 2016; Huan et al., 2020).

Given the growing need for alternatives to conventional antibiotics, various AMPs have been characterized for their anti-MRSA activity. These peptides differ in length, amino acid composition, and target specificity, offering unique advantages in combating resistant strains. To provide a concise overview of these key peptides,

Table 1 lists several well-studied AMPs, summarizing their sources, primary mechanisms of action, and observed minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) against MRSA. It is evident that AMPs demonstrate diverse structural motifs and mechanisms, offering flexibility in therapeutic design. Their multi-target activities allow them to circumvent conventional resistance mechanisms and disrupt biofilms, addressing key challenges associated with MRSA infections. Moreover, ongoing studies on peptide engineering, including cyclization, stapling, and nanoparticle conjugation, further optimize stability, efficacy, and delivery, paving the way for the translation of AMPs from bench to bedside (Mahlapuu et al., 2021; Zhang & Gallo, 2021). This summary highlights the structural diversity and multifaceted activities of AMPs, which collectively contribute to their potential as effective therapeutics against multidrug-resistant infections.

4. Peptide Engineering, Formulation, and Translational Challenges

To overcome natural limitations, AMPs undergo various engineering strategies. Cyclization and stapling enhance peptide stability and protease resistance. Conjugation with lipids, polymers, or nanoparticles improves delivery, reduces toxicity, and increases target specificity. Rational design and computational modeling enable optimization of sequences for potency, stability, and pharmacokinetics (Mahlapuu et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021).

Formulation strategies, including liposomes, hydrogels, and polymeric nanoparticles, protect peptides, enable controlled release, and facilitate diverse routes of administration. Combination therapies with conventional antibiotics can enhance efficacy and reduce required doses. Nonetheless, translational challenges remain, including manufacturing standardization, stability under physiological conditions, regulatory approval, and cost-effective production (da Cunha et al., 2022).

To illustrate these advanced strategies,

Figure 3 provides a comprehensive overview of AMP engineering and delivery approaches. The diagram depicts how cyclization, stapling, and sequence optimization improve peptide stability and activity, while conjugation with lipids, polymers, or nanoparticles enhances targeted delivery and reduces toxicity. Additionally, the figure highlights formulation techniques such as liposomes, hydrogels, and polymeric nanoparticles, which protect peptides, enable controlled release, and facilitate various administration routes. This visual summary underscores the integrated approach required to overcome natural limitations of AMPs and address key translational challenges in therapeutic development.

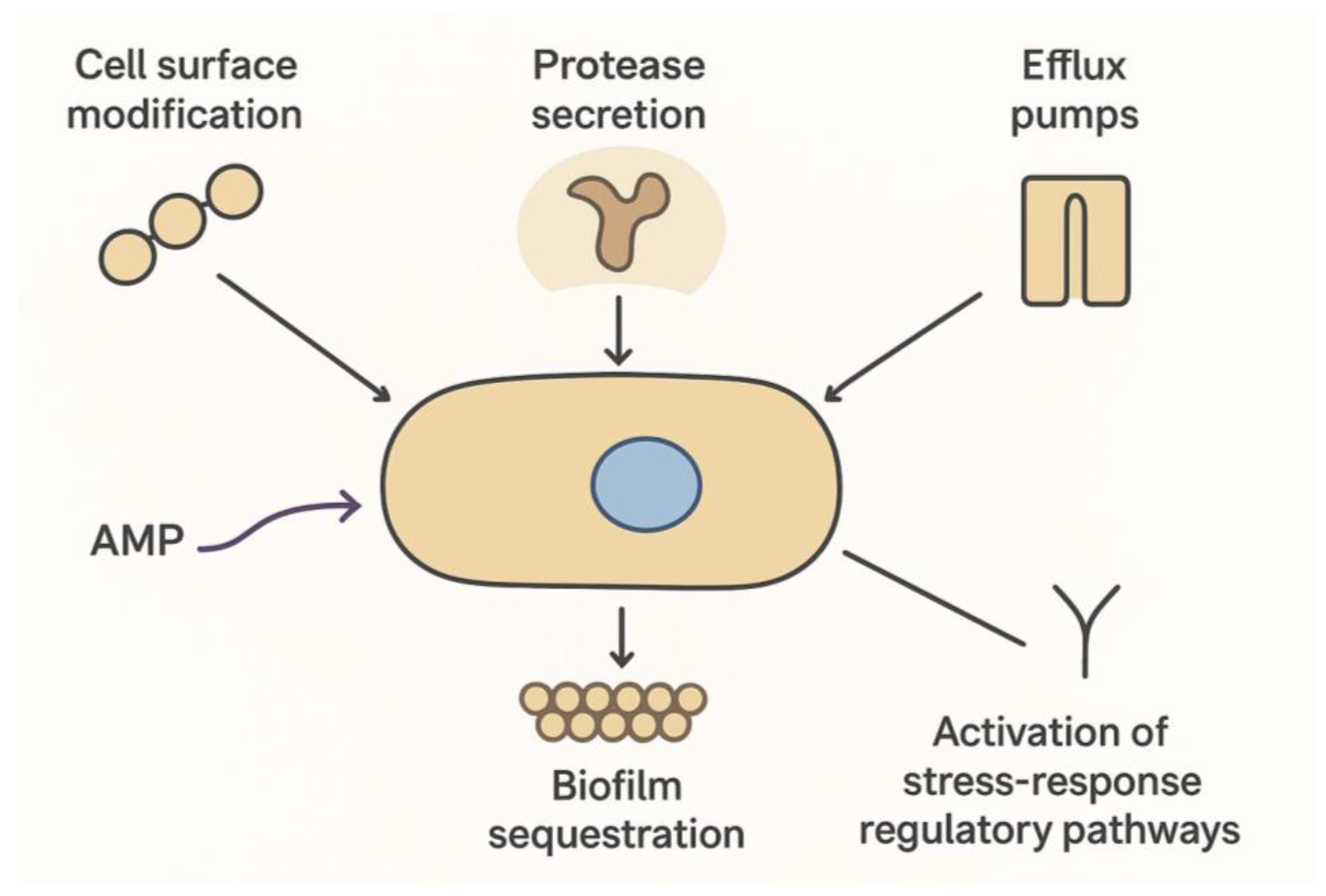

4. Emergence of Resistance to Antimicrobial Peptides (Figure 4)

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) effectively circumvent classic MRSA resistance mechanisms due to their multi-target nature. By simultaneously disrupting bacterial membranes and inhibiting intracellular targets, AMPs limit the emergence of resistant strains, while also exhibiting potent anti-biofilm activity that prevents biofilm formation, disperses established biofilms, and interferes with quorum sensing pathways (Otto, 2013). These properties make AMPs particularly valuable for treating chronic, device-associated, and biofilm-mediated infections. However, despite their broad-spectrum and multi-target mechanisms, MRSA and other pathogens have demonstrated the ability to adapt and reduce susceptibility to these agents. The evolution of resistance to AMPs is multifactorial, reflecting a complex interplay between bacterial physiology, genetic regulation, and environmental pressures (Andersson et al., 2016). Bacteria can modify their cell surface by altering membrane phospholipid composition or incorporating positively charged molecules, which diminishes electrostatic attraction and impedes AMP binding. In addition, the upregulation of extracellular proteases can degrade peptides before they reach their targets, while efflux pumps actively transport AMPs out of the bacterial cytoplasm, reducing intracellular concentrations to sublethal levels. Biofilm formation further contributes by sequestering AMPs within the extracellular polymeric matrix, creating a protective microenvironment with reduced metabolic activity and enhanced stress responses. MRSA can also activate stress-response regulatory pathways, including the GraRS and VraRS two-component systems, to induce adaptive modifications that confer transient or stable tolerance to AMPs (Peschel & Sahl, 2006).

Collectively, these strategies illustrate that, despite their advantages, AMPs are not entirely immune to resistance, highlighting the ongoing evolutionary “arms race” between antimicrobial peptides and bacterial pathogens. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for guiding the rational design of next-generation AMPs, which may include sequence optimization, cyclization, incorporation of non-natural amino acids, or combination therapies to minimize the likelihood of adaptive resistance.

Figure 3 schematically summarizes these known MRSA strategies to evade AMP activity, highlighting the ongoing evolutionary “arms race” between antimicrobial peptides and bacterial pathogens.

Figure 4.

Emergence of MRSA Resistance to Antimicrobial Peptides. Schematic representation of MRSA strategies to evade AMPs, including cell surface modification, protease secretion, efflux pumps, biofilm sequestration, and activation of stress-response regulatory pathways.

Figure 4.

Emergence of MRSA Resistance to Antimicrobial Peptides. Schematic representation of MRSA strategies to evade AMPs, including cell surface modification, protease secretion, efflux pumps, biofilm sequestration, and activation of stress-response regulatory pathways.

5. Clinical Potential and Future Perspectives

Preclinical studies demonstrate AMPs’ efficacy against MRSA, both in vitro and in animal models. However, translating these findings to clinical applications remains challenging. Pharmacokinetic issues, potential cytotoxicity, high production costs, and regulatory hurdles have slowed clinical progress. Current strategies focus on rational peptide design, high-throughput screening, and advanced delivery systems to overcome these barriers. Synergistic therapies combining AMPs with antibiotics or immunomodulators show promise against multidrug-resistant infections (Magana et al., 2020).

Future research should integrate computational approaches, such as machine learning and molecular modeling, to design optimized AMPs with enhanced stability, specificity, and potency. Personalized medicine approaches may also enable tailored AMP therapies for high-risk patient populations. Addressing pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and production costs will be crucial for clinical translation. Ultimately, AMPs have the potential to complement or replace traditional antibiotics in the post-antibiotic era (Huan et al., 2020; Mahlapuu et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021).

6. Conclusion

Antimicrobial peptides represent a promising class of therapeutics against MRSA due to their multi-target mechanisms, rapid action, and reduced potential for resistance development. Advances in peptide engineering, formulation, and delivery technologies enhance their clinical potential. However, the emergence of adaptive resistance mechanisms in MRSA underscores the need for careful design, optimization, and combination strategies to sustain efficacy. Ongoing research integrating rational design, in vivo validation, and combination therapies is critical for translating AMPs from bench to bedside, offering a viable alternative to traditional antibiotics in combating multidrug-resistant infections.

Author Contributions

Husna Madoromae: Data Extraction, Data Curation, Quality Assessment, Writing—Review & Editing: Tuanhawanti Sahabuddeen: Literature Search, Data Extraction, Table & Figure Preparation, Editing: Monthon Lertcanawanichakul (Corresponding author): Supervision, Project Administration, Conceptualization, Literature Search, Data Extraction, Writing—Original Draft, Final Approval of Manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This study received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this review are from previously published studies and are available in the cited references. No new data were generated or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the School of Allied Health Sciences, Walailak University, and the laboratory staff for their valuable support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this work.

Ethics Statement

This study is a literature review and used only previously published data; no human participants or animals were involved. Therefore, ethical approval was not required.

Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)

ChatGPT (OpenAI) was used to assist in grammar and language refinement. No AI tool was involved in data analysis, interpretation, or drawing scientific conclusions. All content was critically reviewed and validated by the authors.

References

- Chambers, H.F.; DeLeo, F.R. Waves of resistance: Staphylococcus aureus in the antibiotic era. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2009, 7, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, R.E.; Sahl, H.G. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nature Biotechnology 2006, 24, 1551–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, B.J.; Tomasz, A. Altered penicillin-binding proteins in methicillin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Bacteriology 1984, 158, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.C. Mechanisms of action and resistance of older and newer fluoroquinolones. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2001, 31 (Suppl 2), S24–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, Y.; Kong, Q.; Mou, H.; Yi, H. Design and modification of antimicrobial peptides to overcome bacterial resistance. Biomaterials Science 2020, 8, 6850–6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Li, Y.; Lu, H.; Shao, T.; Xiong, Y.; Ye, C.; Wang, H. A designed antimicrobial peptide with potential ability against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Frontiers in Microbiology 2016, 7, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.S.; De Lencastre, H.; Garau, J.; Kluytmans, J.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Peschel, A.; Harbarth, S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2018, 4, 18033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, B.; Tuchscherr, L. Staphylococcus aureus persistence in non-phagocytic cells. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2017, 40, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S.C.; Pena, O.M.; Hancock, R.E.W. Host defense peptides: Front-line immunomodulators. Trends in Immunology 2014, 35, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.F.; Abdelkhalek, A.; Seleem, M.N. Evaluation of short synthetic antimicrobial peptides for treatment of drug-resistant and intracellular Staphylococcus aureus. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 29707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlapuu, M.; Håkansson, J.; Ringstad, L.; Björn, C. Antimicrobial peptides: An emerging category of therapeutic agents. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2016, 6, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, M. Staphylococcal biofilms. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology 2013, 322, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; … & Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, S.J.; Paterson, G.K. Mechanisms of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Annual Review of Biochemistry 2015, 84, 577–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, M.C. Update on macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin, ketolide, and oxazolidinone resistance genes. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2008, 282, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shore, A.C.; Deasy, E.C.; Slickers, P.; et al. Detection of mecC, a novel methicillin resistance gene in Staphylococcus aureus. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2011, 11, 606–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.Y.C.; Davis, J.S.; Eichenberger, E.; Holland, T.L.; Fowler, V.G., Jr. Staphylococcus aureus infections: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2015, 28, 603–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.A.; Sharma-Kuinkel, B.K.; Maskarinec, S.A.; et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: An overview of basic and clinical research. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2019, 17, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia contributors. (2025). Lariocidin. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lariocidin.

- Zasloff, M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 2002, 415, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.J.; Gallo, R.L. Antimicrobial peptides: Promising alternatives in the post-antibiotic era. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 6753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).