1. Introduction

Marine carbonate rock reservoirs are rich in hydrocarbon resources, which account for approximately 70% of global hydrocarbon reserves, and have been an important field for petroleum geologists [

1,

2,

3]. With continuous innovations in global hydrocarbon exploration, development theory, and technology, deep and ultra-deep fields are gradually being targeted [

4,

5]. Hence, in recent years, investigation into incremental reserves of deep and ultra-deep oil and gas around the world is increasing rapidly. According to Information Handling Service (IHS) (2014) data[

6], 187 oil and gas reservoirs have been discovered in ultra-deep reservoirs (> 6000 m), with proven recoverable reserves of 943 × 10

8 tons, accounting for 39.99% of the total recoverable reserves in the world. In the past 20 years, a series of breakthroughs have also been made in deep hydrocarbon exploration in China. For example, several deep oil and gas fields have been discovered and developed in both the Tarim and Sichuan Basins. Hydrocarbon reserves were found in Cambrian strata at depths of more than 8000 m in well TS 1, in the northern Tarim Basin[

7,

8] . With a buried depth of 6500–8000 m, fracture-vuggy carbonate reservoirs also developed in Ordovician rocks in the Halahatang Oilfield[

9,

10]. These findings indicate that there are high qualities, abundant hydrocarbon reservoirs in deep carbonate oilfields, which have great potential for oil and gas exploration and development.

The Paleozoic marine carbonate reservoirs of the Tarim Basin experienced multi-stage tectonic events and complex diagenetic alteration during their long geologic history, which resulted in complex reservoirs with distinct features[

9,

11,

12]. For carbonate strata at great burial depths, primary porosity and permeability commonly disappear due to various physico-chemical effects, such as intensive cementation and compaction [

13,

14]. Therefore, the carbonate matrix (CM) generally has both low porosity and permeability[

15,

16]. Reservoirs formed by secondary dissolution are the main reservoir space for deep hydrocarbon accumulation [

17,

18,

19]. Three types of carbonate reservoirs exist, according to the main controlling factors of Ordovician strata in the Tarim Basin: Reef – shoal (by micofacies)[

20,

21], paleo-karst (by weathered crust)[

22,

23,

24], and "sweet spot" cavity reservoirs (by fault) [

25,

26].

The Tahe Oilfield is located on the south of the Tabei Uplift; it is a famous integrated marine carbonate oil and gas field, which has proven geological reserves exceeding 13.5× 10

8 tons [

27]. The most prolific strata are the Lower–-Middle Ordovician Yijianfang Formation (O

2yj) limestone, and the Yingshan Formation (O

1-2y) limestone and dolomite. In the northern or “main” area of the Tahe Oilfield, affected by multi-stage tectonic uplift, weathering, and denudation[

28], the Upper Ordovician strata are almost completely eroded [

22,

29]. Therefore, long-term exposure, leaching, and karstification occurred in both the Yijianfang (O

2yj) and Yingshan Formations (O

1-2y). The paleokarst systems mainly developed under the influence of multi-stage karstification for millions of years. In contrast, the southern area of Tahe Oilfield falls within the peripheral slope area (

Figure 1(b) and (c)); the Upper Ordovician strata did not undergo strong denudation due to the relatively weak intensity of multi-stage tectonism in this area[

30]. Therefore, the upper part of Lower–Middle Ordovician limestone is covered by a thick nearly insoluble layer of Upper Ordovician argillaceous limestone. Local petroleum exploration and development have proved that there are high-quality, rich reservoirs in the southern region of Tahe Oilfield[

31]. There is no obvious weathering of Middle and Lower Ordovician limestone due to the shielding effect of the Upper Ordovician strata. Therefore, the genetic mechanism, controlling factors, and distribution rules of deep high-quality carbonate reservoirs in the southern area of Tahe Oilfield are clearly different from those in the northern area of Tahe Oilfield.

The formation and maintenance of high quality deep carbonate reservoirs are controlled by many factors. It is well known that fault systems and their distribution play a key role in hydrocarbon migration and accumulation in petroliferous basins[

32,

33] . Fault systems may also have important controls on subsurface fluid flow acting as localized conduits[

34,

35,

36] or barriers[

37,

38], caused by the difference of permeability and surrounding rock in fault zones of several orders of magnitude[

36]. Faults in carbonate strata are more distinctive as they not only demonstrate the interplay of the two above mentioned roles, but also the area impacted by the physical and chemical actions of various diagenetic fluids[

39]. During the long-term burial period, considering both tectonic activity and fault growth, different diagenetic processes (e.g., cementation and dissolution) occurred in the fault zones under a series of physical and chemical actions, resulting in the formation of different types of reservoir spaces [

40,

41]. Rock fracturing and fault system development and distribution are assumed to enhance the permeability of significant physical modifications in deep carbonate strata[

41,

42]. The types and activity characteristics of diagenetic fluids are the main factors affecting dissolution and reformation within deep carbonate strata[

43]. Many scholars believe that the diagenetic fluids in deep carbonates mainly include meteoric water[

17,

44], hydrothermal fluids[

45,

46,

47], organic acids, and acidic fluids produced by thermochemical sulfate reaction (TSR)[

48,

49,

50], which increases the reservoir capacity. The difference of diagenetic fluid properties leads to the difference of dissolution ability and reservoir scale in deep carbonate formation. We have not yet fully understood the origin and evolution of carbonate reservoirs which covered by the thick and insoluble in the southern area of Tahe Oilfield, how Paleozoic strike slip faults and diagenetic fluids affect reservoir development is still unclear. These key problems restrict the further exploration and development of deep hydrocarbon resources in Tahe Oilfield.

Based on cores, well logging, image logging, and seismic data, in this study, we characterize the fault system and carbonate reservoir features in detail in deep strata of the southern area of Tahe Oilfield. The characteristics of diagenetic fluids are studied based on C, O, and Sr isotopes, as well as fluid inclusions in the southern area of Tahe Oilfield. The objectives of this study are as follows: (1) to determine the relationship between the strike slip fault and carbonate reservoir; (2) to analyze the types and evolution of diagenetic fluids for such carbonate reservoir dissolution; and (3) to discuss the effect of strike slip faults and diagenetic fluids on the origin and evolution of carbonates reservoirs.

2. Geological Setting

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

The Tarim Basin covers an area of up to 56 × 10

4 km

2 in northwest China[

51]. The Basin is a superimposed petroliferous basin, surrounded by three orogenic belts: the Tianshan tectonic belt in the north, the Altun tectonic belt in the South, and the West Kunlun tectonic belt in the southwest[

52]. The Tahe Oilfield, with an area of 2400 km

2, is located in the south of the Tabei Uplift in the Tarim basin (

Figure 1(a)). The Tabei Uplift borders the Kuqia depression in the north and Manjiaer depression in the south. It is an ancient uplift developed on the pre-Sinian metamorphic basement, which experienced multiple tectonic movements. The Tahe Oilfield is rich in hydrocarbon resources, with the main hydrocarbon production area originating from the Lower–Middle Ordovician carbonate reservoir, accounting for more than 70% of the total production. The study area is located in the southern area of Tahe Oilfield (

Figure 1 (b), (c), and (d)).

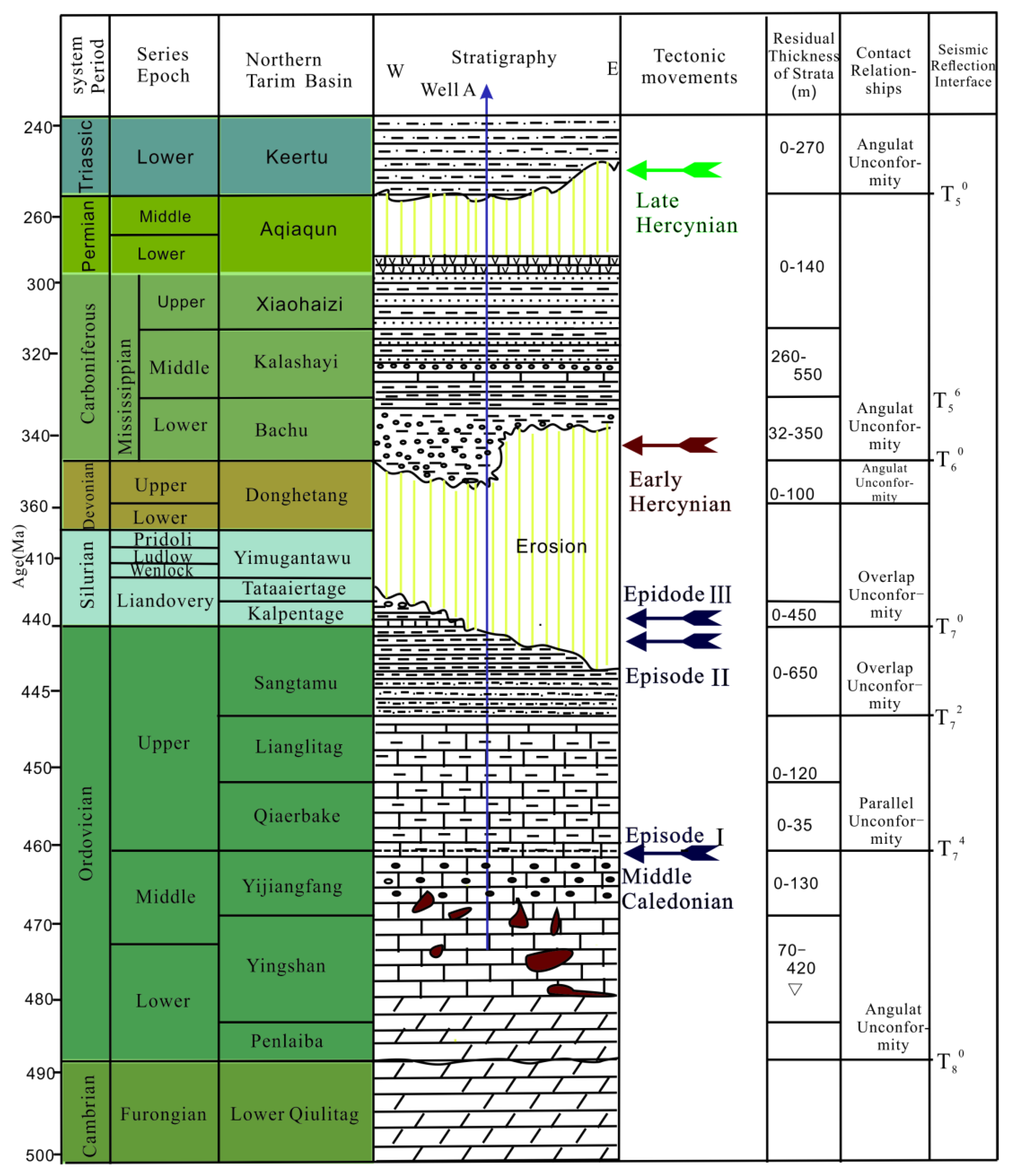

The basement of the Tarim Basin is composed of pre-Sinian craton metamorphic rock, which is overlain by a sedimentary sequence with a 16000 m maximum thickness between the Sinian and the Quaternary[

53]. The Paleozoic marine strata are developed in the Ordovician, Cambrian, and Upper Sinian, of which the Ordovician carbonate rocks are currently the main oil producing horizon. The Ordovician stratigraphic sequences in the southern area of Tahe Oilfield from bottom to top can be divided into six stratigraphic units[

54].

(1) The Lower Ordovician Penglaiba Formation (O1p): 250–400 m thick, developed from a tidal flat-shallow shelf environment, primarily composed of silty fine crystalline dolomite and calcareous dolomite;

(2)The Lower–Middle Ordovician Yingshan Formation (O1-2y): 600–900 m thick, the result of a restricted platform-open platform environment, primarily composed of yellow gray to light gray micritic limestone and dolomitic limestone, which is conformable with the underlying O1p Formation;

(3) The Middle Ordovician Yijianfang Formation (O2yj): mainly consisting of microcrystalline limestone and sandy limestone, from an open platform environment;and the three Upper Ordovician deposits mainly consisting of marginal slope-shelf and continental platform depositional environments;

(4) The Querbake Formation (O3q) and (5) the Lianglitage Formation (O3l): mainly composed of knotty limestone containing mud and argillaceous limestone;

And( 6) The Sangtamu Formation (O

3s): mainly consisting of siliciclastic mudstone and sandstone, with a thickness up to 900 m, and showing unconformable contact with the overlying Silurian strata[

54]. The O

3s Formation is composed of insoluble siliciclastic rocks with a large thickness; hence, it often regarded as a regional caprock, which blocks the exposure and dissolution of the underlying carbonate strata. The insoluble O

3s Formation pinch-out line divides the Tahe Oilfield into its northern and southern parts[

54]. Compared with the northern region, the Upper Ordovician strata in the southern region are relatively intact (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

After the formation of the Pre-Sinian metamorphic basement, the Tabei Uplift underwent the multistage major regional tectonic movements: Caledonian, Hercynian, Indosinian-Yanshanian, and Himalayan. Among them, the Middle Caledonian and Early Hercynian tectonic movements played an important role in the structural morphology and fault development of Tahe Oilfield. From the Early Sinian to Early Ordovician, the Tarim block broke away from the Rodinia supercontinent, and the northern Tianshan Ocean expanded in the northern part of the Tarim plate[

52,

55]. The Middle Caledonian tectonic movements in the Middle Ordovician led to the northward movement of the Tarim plate and subsequent collision with the northern East Tianshan plate, which resulted in changing the background stress from tension to compression, creating the Tabei Uplift.

The Middle Caledonian tectonic movements can be divided into three episodes: the first episode movement had little influence on Tabei uplift. The second episode movement formed by the collision between the southern Tarim Basin and the South Kunlun plate was relatively weak, and the Tabei uplift continued to rise. The third episode movement caused by the collision between the southern Tianshan Ocean island arc and the northern margin of Tarim Basin further uplifted the northern part of Tabei Uplift and formed the unconformity between Silurian (S) and Ordovician (O)[

56].

The early Hercynian movement occurred at the end of the Devonian Period, causing strong erosion of the Devonian, Silurian, and Upper Ordovician strata, and creating an angular unconformity between the Carboniferous (C) and Ordovician (O). The Late Hercynian movement took place during the Middle Permian–Late Permian. There largely developed volcano erupting and effusing of the lava from the deep stratum in Tarim Basin, the thickness of 10 to 100 m of magmatic rocks caused by the Tarim Large Igneous Province are encountered in most wells in the southern Tahe Oilfield[

57].

Due to the differential uplift of the Tabei uplift, there are obvious differences in carbonate reservoir development between the northern and southern area of Tahe Oilfield. As a result of multi-stage tectonic movement, the Devonian, Silurian and Upper Ordovician strata were denuded in the northern area of Tahe Oilfield. The Middle and Lower Ordovician (O2yj and O1-2y) carbonate rocks are subaerially exposed, and were leached and dissolved by atmospheric fresh water, which developed into a mainly paleokarst drainage system. On the contrary, in the southern area of Tahe oilfield, the Middle-Lower Ordovician carbonate rocks remained covered by regional caprock; hence, these strata did not directly undergo erosion and karstification by atmospheric fresh water. This implies that the southern Tahe oilfield hydrocarbon reservoir development is mainly affected by faults.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Core Samples, Well Logging, and Seismic Data

Currently, more than 93 wells have been drilled into the Middle-Lower Ordovician carbonate strata of the southern Tahe Oilfield. Most of these are vertical wells with finished depths exceeding 6000 m. The cores from 13 coring wells were observed comprehensively, and 485 core photographs were collected to analyze the rock type and characteristics of the carbonate reservoir. Over 270 thin sections cut from the carbonate rock cores from 13 representative wells were observed through cathodoluminescence (CL) using a Zeiss Axio Imager fluorescence microscope in the Key Laboratory of Reservoir Geology, in Shandong Province. Obvious differences in the geophysical response between the fracture-cavity and the tight CM were found. A total of 93 sets of conventional logging data and 15 Formation Microscanner Images (FMIs) were obtained from the wells in the study area; together, these provided sufficient data for characterizing the fractures and caves within individual strata.

The high-precision 3D seismic dataset covering approximately 398 km2 of this study area was processed in 2013, with a data bin size of 15 m × 15 m. The overall vertical sample rate of the seismic volume was 2 ms, and the target formation of dominant frequency was approximately 35 Hz. The large-scale reservoir shows "a string of beads" strong amplitude in seismic sections[

58]. This seismic data was processed via a series of steps, and the coherence and curvature attributes of different target horizons were extracted from the seismic data volume to identify and predict the characteristics of faults and fractures. Variance and curvature attributes are the seismic attributes that can calculate the difference between waveforms or traces in 3D seismic volume, which is very sensitive to fault interpretation. The plane distribution of the carbonate reservoir is characterized by extracting the amplitude variation rate attribute, while the spatial variation of the carbonate reservoir is characterized by 3D sculpture volume. We used SVI software (by PetroSolution Tech, Inc.) to identify the extent of faults and carbonate caves by characterizing both the spatial distribution pattern of the faults and the spatial morphology of the resulting karst caves. The detailed workflow of this process includes three steps:

(1) Use a Noise Filter to de-noise the original seismic data to improve its image clarity, extracting the composite attributes of both Tensor and Envelope attributes from the processed seismic volume;

(2) Fault and geological body signal enhancement and recognition; and (3) fuse and display the identified faults and geological bodies.

3.2. Geochemistry

The 15 core samples were crushed into millimeter-sized fragments and pure calcite vein particles were picked out. The pure calcite particles were ground into 200 meshes -- fine powder for testing by a grinding apparatus. The experimental process is detailed in Han et al. (2019). All isotope experiments were carried out at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences. C and O data are reported as per mil (‰) δ18O and δ13C values relative to Pee Dee belemnite (VPDB international standard), respectively. The precision for δ13C and δ18O measurement was ±0.2‰.

A total of 12 powder samples were analyzed using a Finnigan MAT Triton TI for Sr isotope compositions. Rock powders and 2 mL of 6 M HCl were used for a dissolution reaction in a jar, for 24 h at a temperature of 100–110 ℃. Results were controlled by repeated analysis of the NBS-987 standard, averaging (n=26) 0.710202 ±0.00004 (2σ), normalized to

87Sr/

86Sr, and equal to 0.1194[

15].

Fluid inclusion (FI) micro-thermometric analysis was performed on the calcite samples using the Linkam THMGS600 heating-freezing stage. Homogenization temperature measurements were obtained using a heating rate of 10 ℃/min. Comprehensive analysis was performed on 456 fluid inclusions in calcite, which filled dissolution pores, fractures, and caverns within 11 wells.

4. Results

4.1. Reservoir Types and Characteristics

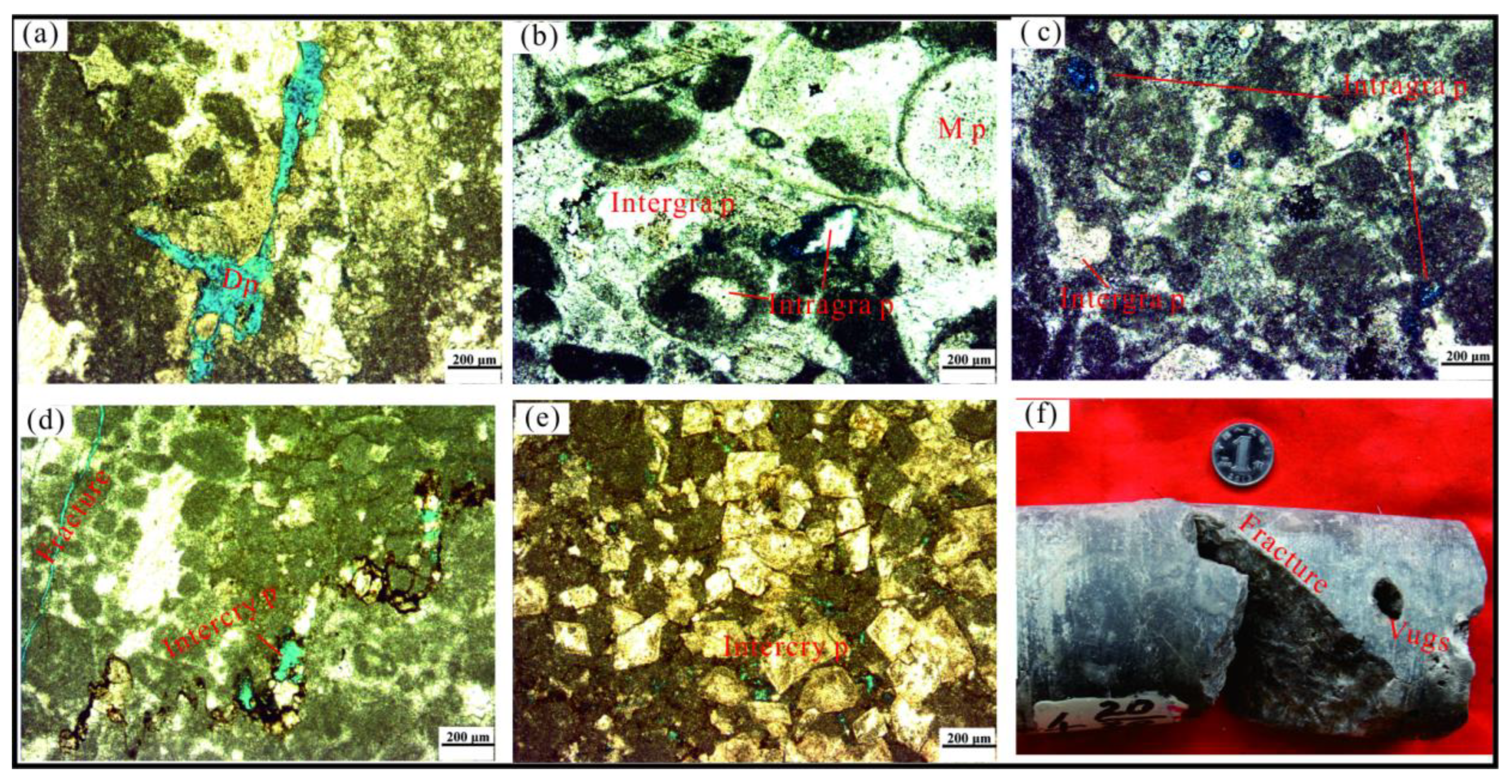

The Ordovician carbonate reservoirs in the southern area of Tahe Oilfield were not generated by weathering crust karstification because the Middle-Lower Ordovician carbonate rocks have not undergone large-scale upliftment nor been exposed to the surface for a long time. Over its long geological history, the Middle-Lower Ordovician carbonate strata experienced complex cementation and long-term strong compaction; hence, the contribution of CM porosity and permeability to reservoir space is very small. The matrix porosity of the Middle-Lower Ordovician carbonate rocks ranges from 0.6 to 3.8%, with an average of 1.62%; the permeability is mainly distributed as 0.02–21.02 × 10-3 μm2, with an average of 1.32 × 10-3 μm2. Moreover, the carbonate strata underwent both multi-stage tectonic movements and multi-stage dissolution by diagenetic fluids, thus forming a complex heterogeneous porous system dominated by dissolved pores, fractures, and caves, which developed into the main reservoir space.

The dissolved pores of the Middle-Lower Ordovician hydrocarbon reservoirs mainly include intergranular dissolution pores, some intragranular and intercrystalline dissolution pores, and moldic pores (

Figure 4a and f). The fluids flowing along the fractures have better contact with surrounding rock on both sides; these fluids dissolve the calcite to form dissolved pores (

Figure 4c). The intergranular residual pores and intragranular pores formed by the dissolution of calcite minerals are filled again in the later stage (

Figure 4b). The other types of intergranular pores occur between dolomite crystals; dolomite agglomerates are distributed in the stylolite structure, and the intercrystalline pores are filled with asphaltene (

Figure 4d and e).

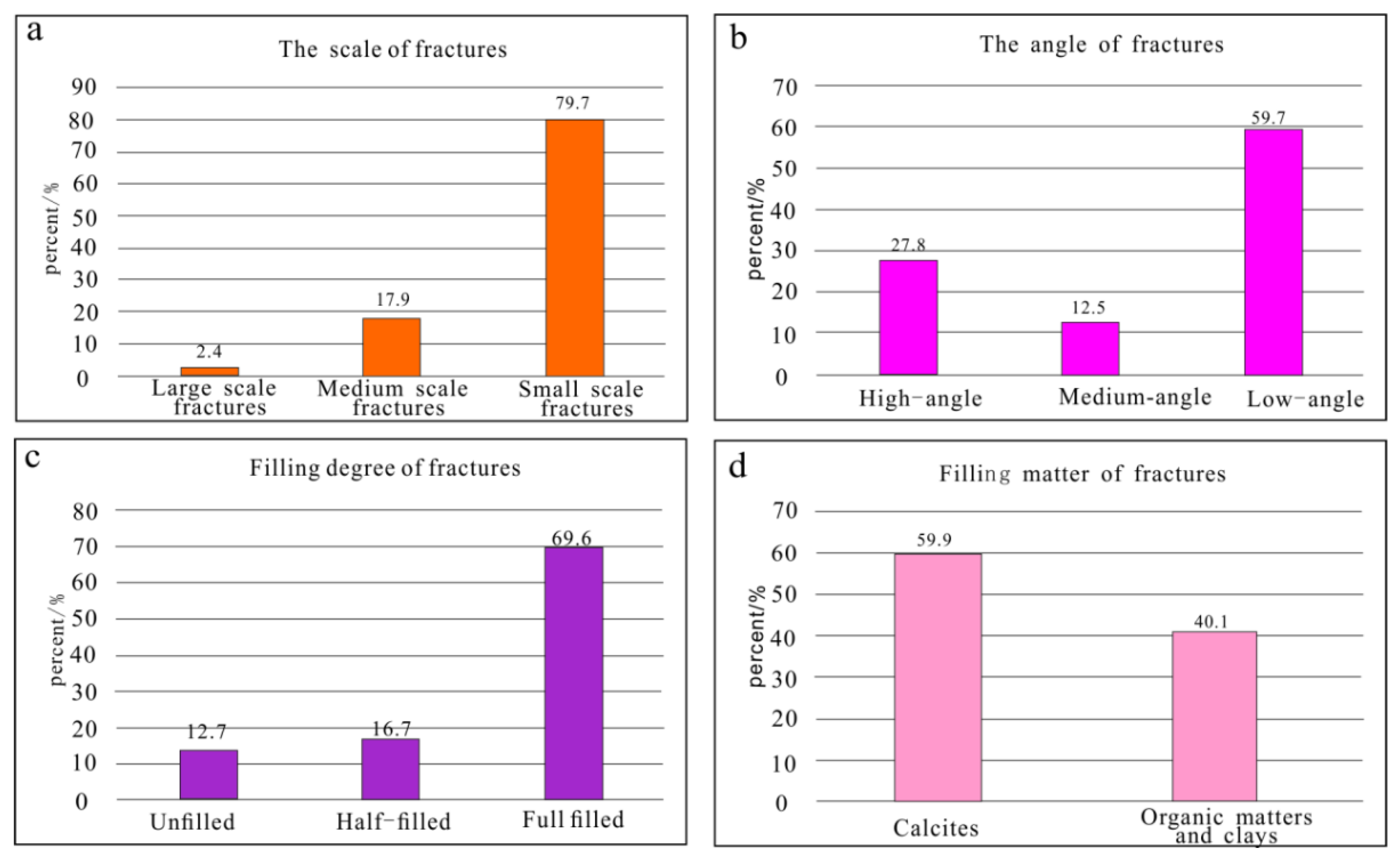

Fractures are not only an important reservoir space in carbonate rocks, but they also function as a main fluid migration pathway[

59]. Structural fractures are one of the main types of reservoirs in the study area, which are mainly distributed on both sides of the fault zone and in the axial region of folds. These are mainly medium-small fractures, wherein small fractures account for 79.7% and medium fractures account for 17.9% of the total fractures (

Figure 5a). The low angle fractures that account for 59.7% are short and flat, and most of them are filled with calcites and clays (

Figure 5b and c). The medium angle and high angle fractures are tension-shear fractures; their fracture surface is relatively straight, the width of the fracture aperture is more than 0.1–1 cm, and they are unfilled or half-filled with calcites and dark organic matter (

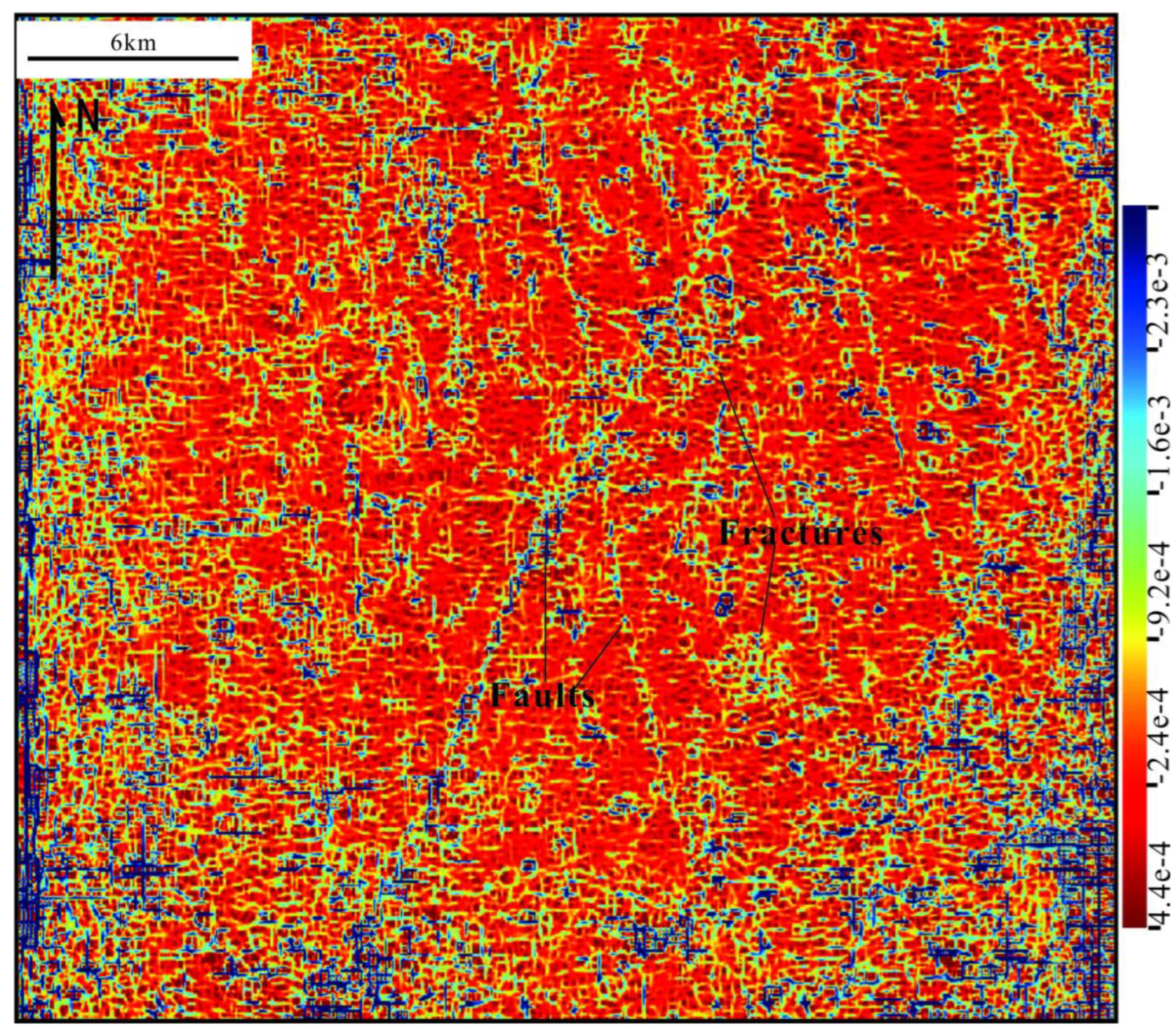

Figure 5d). These fractures appear on the FMI as sinusoidal lines, and the amplitude of sinusoidal lines of fractures with different dip angles are varied. The greater the amplitude of the sinusoidal lines, the larger the fracture dip angle, and vice versa. The faults and derived fractures show good response characteristics on the attribute of maximum negative curvature maps[

60]. The most developed structural fractures, which are linear or reticular (in the blue yellow area), are distributed on both sides of the fault; and the larger the fault, the wider the development range of the fractures on both sides (

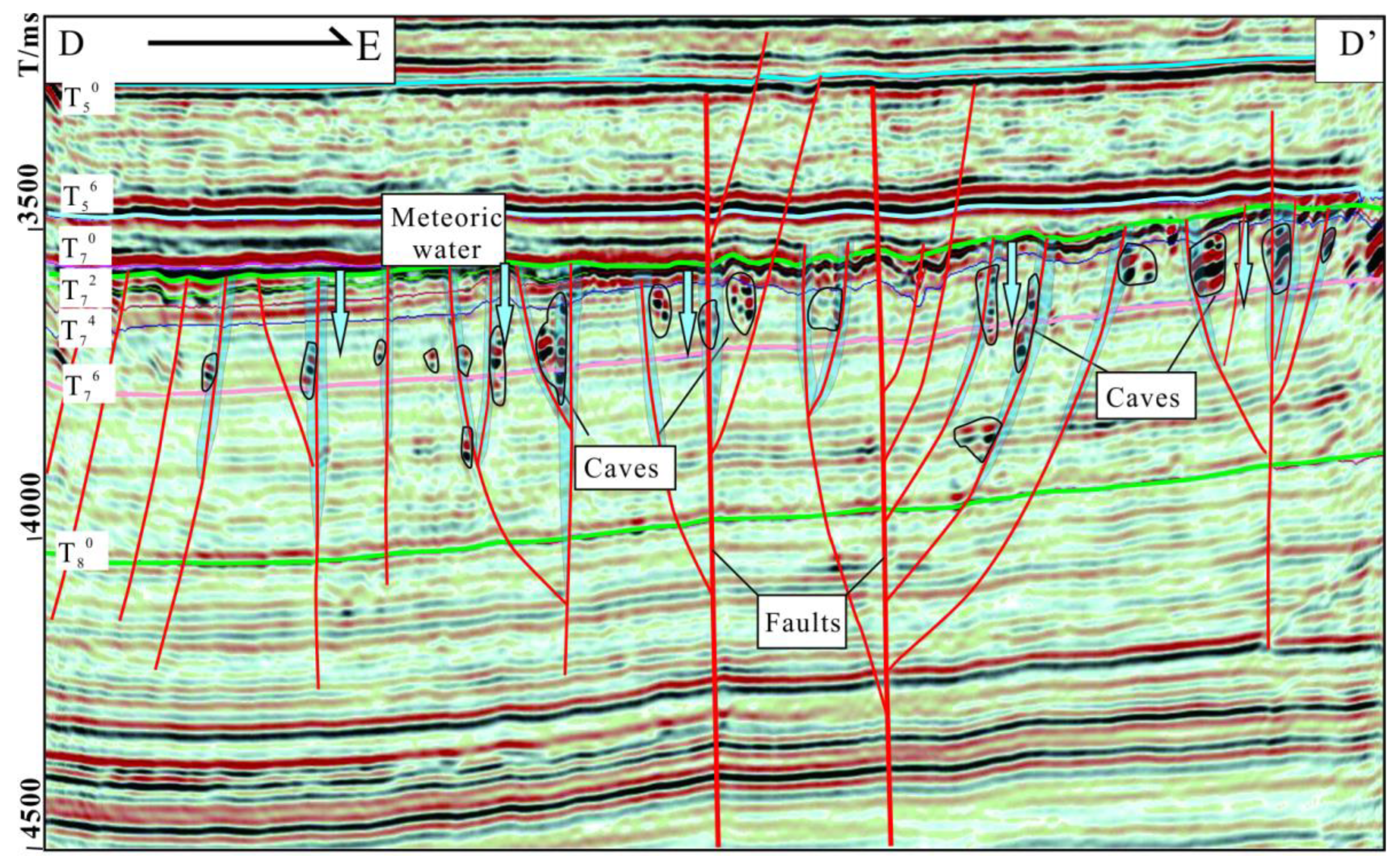

Figure 6).

The diameter of large caves is more than 100 mm; hence, owing to its large scale, it cannot be completely observed on the core. Karst breccia formed by cave collapse and calcareous debris sediments brought in with flowing water can be observed on the cores. This can be easily identified by dropout, mud loss, and sudden acceleration during drilling. The well logging response of the caves shows that the natural gamma (GR) value increases, the diameter expands clearly, the deep investigate induction log (LLD) and shallow investigate induction log (LLS) value decreases significantly and shows a positive difference, the density logging (DEN) value decreases, and the acoustic time difference (AC) value and neutron (CN) also show a clear increases. The FMI logs show dark black and disordered images (

Figure 7). On the seismic section, owing to the velocity and impedance differences between the caves and surrounding CM, the deep buried cave complexes are displayed as ‘bright’ spot-shaped reflections (

Figure 7), which implies strong reflection amplitudes, long longitudinal extensions, and small horizontal ranges [

31]. This is the main reservoir space of oil and gas, indicating high well production. In this study, we used the attribute of amplitude change rate, which is sensitive to extremely high amplitudes, for characterizing caves complexes. When seismic waves propagate in homogeneous carbonate rock, the change in the seismic wavelength is small. However, when encountering caves the seismic wavelength will change, showing a high amplitude and frequency response. Therefore, the amplitude change rate of the CM is a low value and appears as a blue area; in contrast, the fracture cave reservoir development zone shows a high value and displays a bright red color (

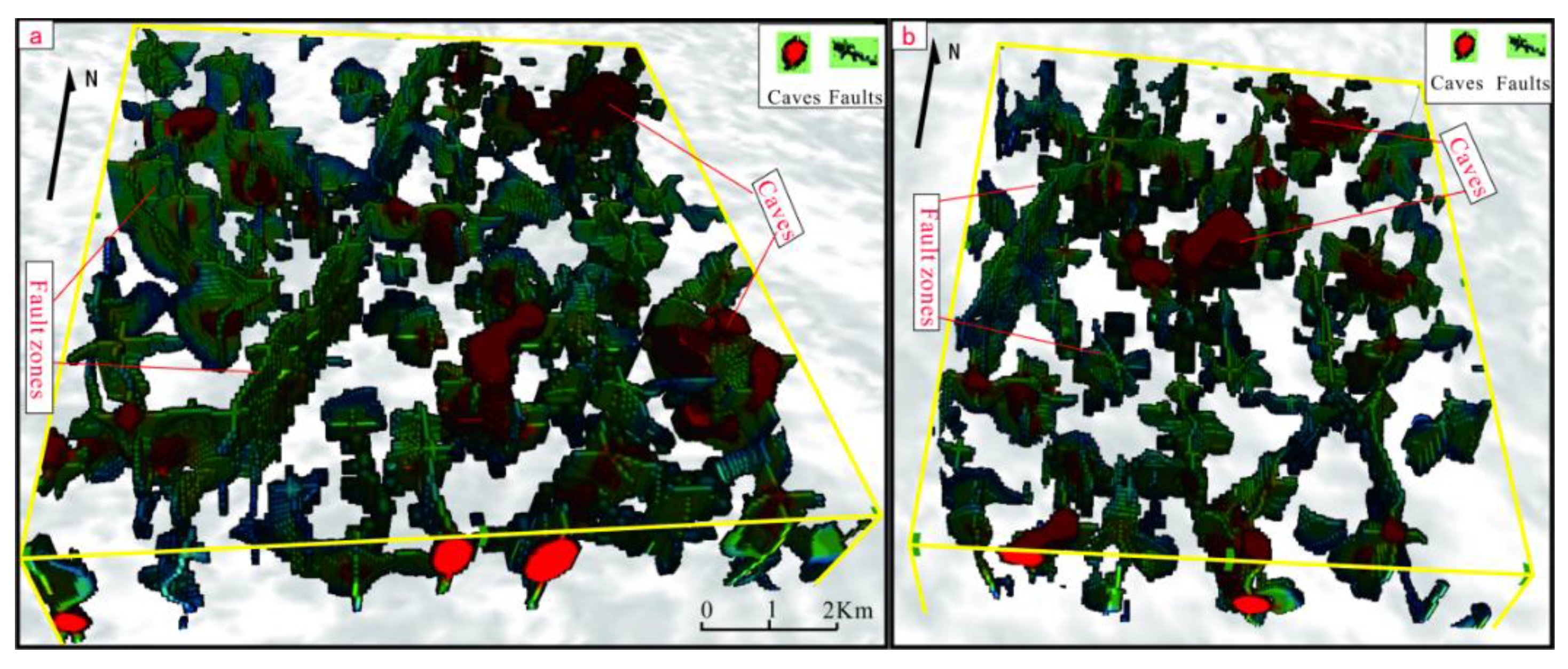

Figure 8a). The spatial distribution characteristics of cave bodies in carbonate rock can be observed more clearly using 3D models of the caves. The extraction of the enhancement tensor and envelope attributes and carving of the cave body used SVI software, selected appropriate threshold values of the attributes to depict the fracture cavity body, thus allowing us to better understand deeply buried paleokarst reservoirs, and the caves mostly isolated in spatial distribution and have poor region connectivity (

Figure 8b). The supergene karstification of meteoric water is not developed in the Middle- Lower Ordovician carbonate rocks in this area, and there is no formation of a paleokarst drainage system. Hence, the reservoir development is mainly controlled by the fault system.

4.2. Paleozoic Fault Characteristics and Evolution

As the quantitative estimation of the fault formation period is difficult, we primarily determine the relative formation period of the faults within the seismic section. Based on the analysis of regional tectonic stress field, the formation period is determined by the relationship between faults with neighboring stratigraphy and unconformity in the seismic section. When a fault cuts off a stratum, this indicates that the fault is younger than the stratum; conversely, when another fault terminates the stratum, the fault is determined to be older than the stratum[

52].

4.2.1. Multi-Stages of Paleozoic Faults

According to the above criteria estimate of the fault formation period, faults in the study area can be divided into four stages using new 3D seismic data: extensional faults in the Cambrian–Early Ordovician; strike-slip faults in the Middle Ordovician; reactivation of strike-slip faults in the Silurian–Devonian; and faults related to volcanic activities during the Permian.

(1) Extensional normal faults during the Cambrian–Early Ordovician

In the early Caledonian period, the Tarim Basin was located in an extensional environment due to the spreading of the Ancient Tianshan Ocean, the Ancient Kunlun Ocean, and the Altyn Ocean. The slope area of the Tahe Oilfield in the Tabei Uplift, is subjected to relatively weak N-S extension, forming two groups of early normal extensional faults in both the NEE and NWW directions (

Figure 10a). The fault plane is steep and straight, with relatively minor throw values, and a part of the fault plane cuts downward through the top of the Precambrian strata (T

90). Under the influence of subsequent multiple period tectonic movements, the extensional faulting was reactivated and became complex (

Figure 9).

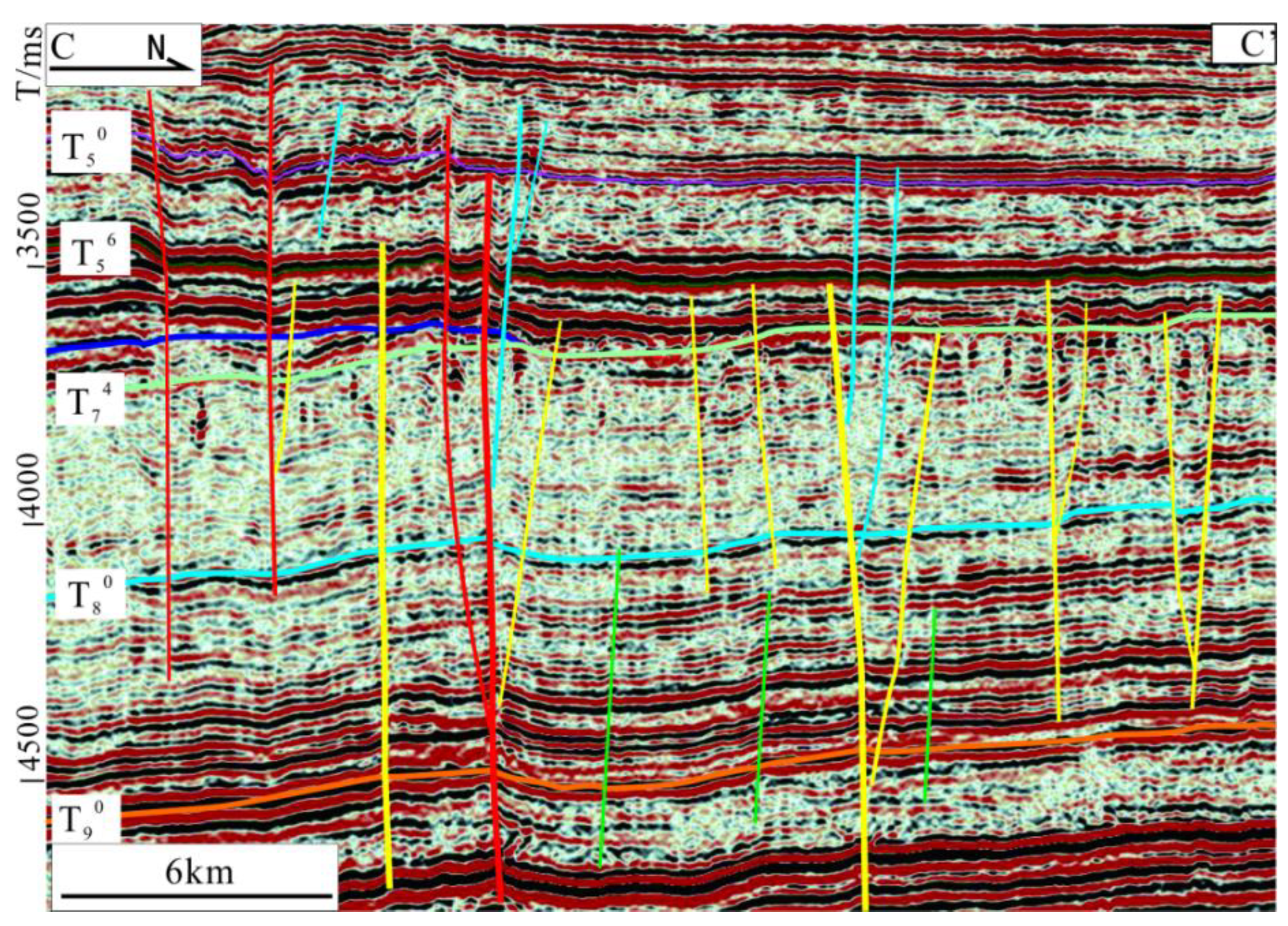

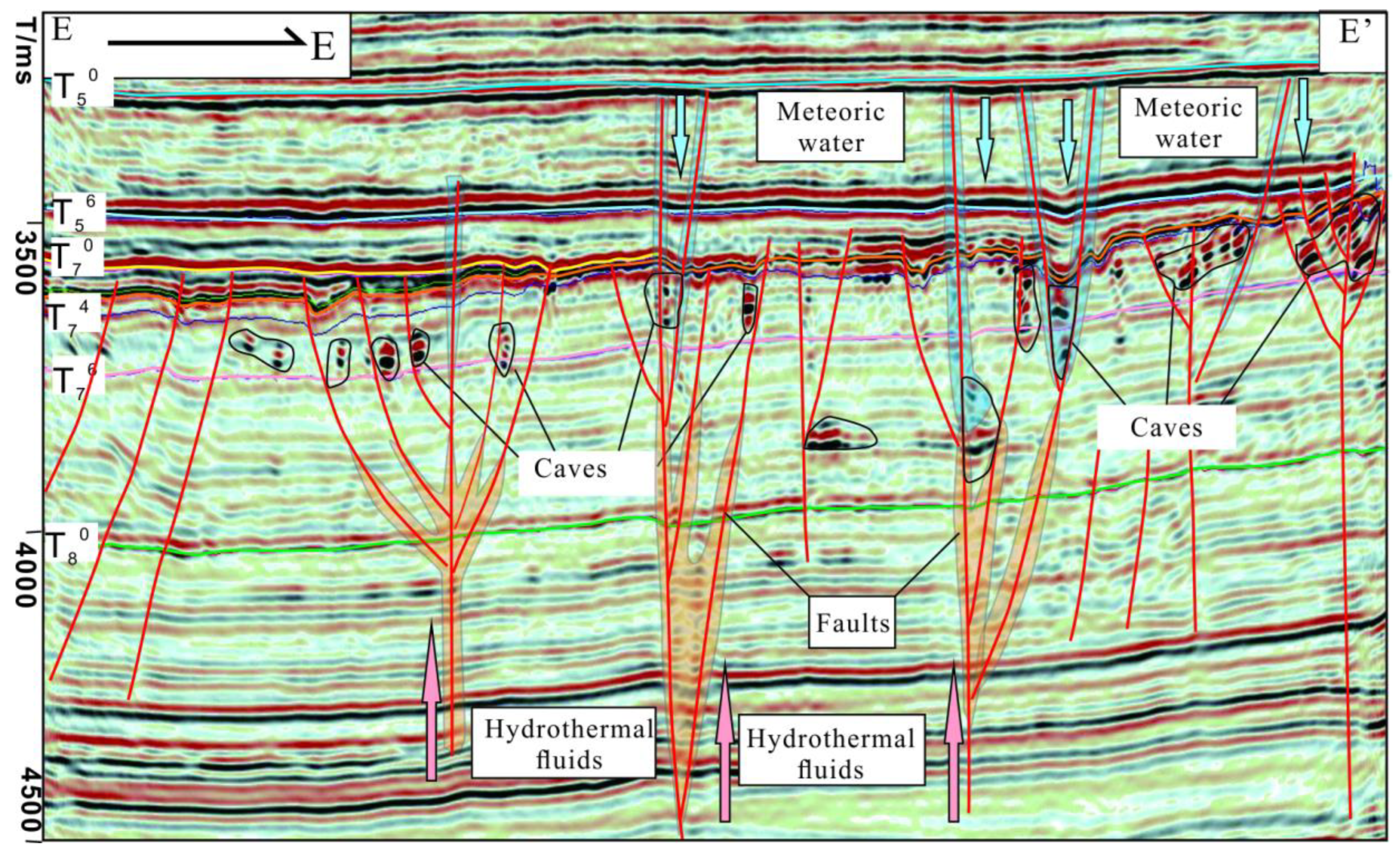

Figure 9.

Seismic profiles across the study area showing the Paleozoic faults and stratigraphic interpretations. See

Figure 1: C-C’ for location. Faults are in their color definitions: Early Caledonian in green, Early/Middle Caledonian–Early Hercynian in yellow, Early/Middle Caledonian–Late Hercynian in red, Early Hercynian and Late Hercynian in navy.

Figure 9.

Seismic profiles across the study area showing the Paleozoic faults and stratigraphic interpretations. See

Figure 1: C-C’ for location. Faults are in their color definitions: Early Caledonian in green, Early/Middle Caledonian–Early Hercynian in yellow, Early/Middle Caledonian–Late Hercynian in red, Early Hercynian and Late Hercynian in navy.

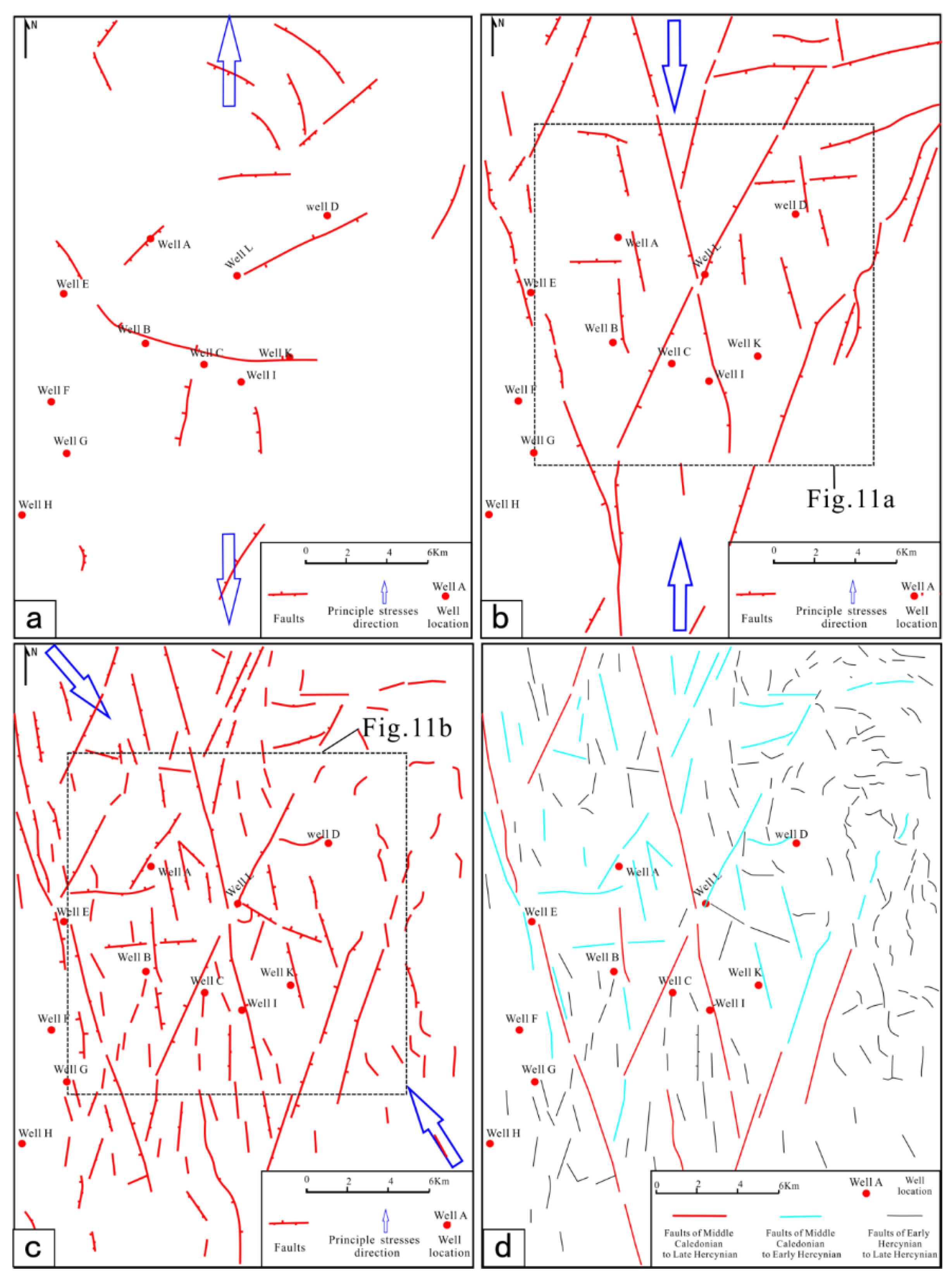

Figure 10.

Distribution of fault system in different stages. (a) Faults formed in Early Caledonian period; (b) Faults formed in Middle Caledonian period; (c) Faults formed in Early Hercynian period; (d) Characteristics of inherited faults.

Figure 10.

Distribution of fault system in different stages. (a) Faults formed in Early Caledonian period; (b) Faults formed in Middle Caledonian period; (c) Faults formed in Early Hercynian period; (d) Characteristics of inherited faults.

(2) Strike-slip faults in the Middle Ordovician

In the Middle Caledonian, the tectonic stress field of the Tarim Basin changed from extensional to compressional, and the Tahe Oilfield region underwent S-N compression stress action. A group of NNW and NNE trending “X” conjugate shear faults with large extension lengths (

Figure 10b) and good continuity can be seen clearly on the stratum coherence attribute map (

Figure 11a) and maximum curvature attribute map (

Figure 11b). The faults formed during this period are characterized by their large scale, as they cut through several strata on the seismic section. The inherited faults also cut through the top surface of the deep Cambrian strata (T

90) (

Figure 9).

(3) Reactivation of strike-slip faults in the Silurian-Devonian

In the Early Hercynian tectonic movement, the direction of the compression stress field transformed from S-N to the NW and SE direction. This period is the most important in terms of tectonic movements for large-scale fault development in the Tahe oilfield. Under the action of strong tectonic compression-torsion stress, a series of derived faults developed on both sides of the NNW and NNE trending “X” conjugate strike slip faults (

Figure 10c). The faults formed in the Middle Caledonian, then moved further and upward, cutting through the Upper Ordovician Sangtamu Formation (T

70). There are four types of structures of strike slip faults on the seismic section: positive flower-structure, negative flower-structure, half flower-structure. The flower-structure is characterized by the steep and straight fault plane of the main fault, which plunges directly into the deep Cambrian strata. The derived faults are distributed on both sides of the main fault, converging from the shallow to the deep and intersecting with the main fault. Positive flower-structure is characterized by "compression, reverse fault and anticlinal fold" and negative flower-structure is characterized by "extension, normal fault and syncline structure". The half flower-structure develops derived faults only on one side of the main fault (

Figure 9).

(4) Faults related to volcanic activities during the Permian

At the end of Early Permian, the Tarim Basin was in a continental rift extensional environment due to the comprehensive action of the ancient Tianshan Fold Belt and the subduction of the Old Tethys Ocean. Basic volcanic eruptive rocks and neutral-acid eruptive rocks occurred widely in the Tarim Basin. As a result of the volcanic activities, a series of extensional normal faults was formed, which were mainly distributed along the pre-existing faults; their strike directions are varied, and lengths are relatively short.

4.2.2. Inheritance of Paleozoic Faults

The faults in the study area were comprehensively affected by multi-stage tectonic movements, and the tectonic stress field and evolution characteristics are complex. Therefore, the fault activity may continue over a long period, developing simple to complex evolutionary characteristics, from small to large scales. According to the plane distribution characteristics and evolutionary history of faults on the seismic section, the fault formation and final relative faulting period was determined and analyzed; this is summarized as follows:

(1) From Middle Caledonian to Late Hercynian continual activity

These faults are characterized by multi-stage activity and inherited development, which often manifested as the reactivation of early formed faults under the action of late tectonic movement. With structural inversion, the nature and scale of faults often change. These faults formed in the Middle Caledonian and stopped being active in the Late Hercynian: two groups of NW-SE faults with long extensions (

Figure 10d), cutting downward through T90 and upward to T

50 on the seismic section (

Figure 9).

(2) From Middle Caledonian to Early Hercynian continual activity

This area includes faults formed in the Middle Caledonian that stopped activity in the Early Hercynian With the further stress increase, some strike slip faults were reactivated in the middle Caledonian when the derived strike slip faults developed on a large scale. These are distributed in the NNW and NNE direction (

Figure 10d), cutting downward through T80 and terminating upward at T

56 on the seismic section (

Figure 9).

(3) Early Hercynian and Late Hercynian active faults

Most of these faults were formed by single stage tectonic movements, and the later stage tectonic movements had little influence on them. With relatively small scale and short profile extensions, they only cut downward through T

74 and terminated upward at T

50 (

Figure 9).

Owing to the heterogeneity of the tectonic stress field intensity and the transformation of direction of tectonic movements, large-scale strike slip faults indicate clear segmentation on the plane, with complex differences in the nature, scale, and structural style of the faults.

4.3. Geochemical Characteristics

4.3.1. C and O Isotopes

C and O isotopes can reflect the changes in ancient sedimentary environments. The isotopic compositions of C and O in the CM, pore-filling fine-crystallinecalcite (PC), fracture-filling middle-coarse crystalline calcite (FC), and cavity-filling coarse crystalline (CC) samples are summarized in

Table 1. All samples in this study were collected from the Yingshan and Yijianfang Formations. The changes in various geological factors in marine sedimentary environments are relatively small; hence, the chemical and thermodynamic properties of carbonate rocks formed in this environment are relatively stable[

57].

The CM samples have δ

13C values ranging from -1.5‰ to 0.5‰ VPDB (average -0.4‰ VPDB), and δ

18O values from -6.7‰ to -6.3‰ VPDB (average -6.5‰ VPDB) (

Table 1). The isotopic compositions of C and O are consistent with those of the un-eroded Ordovician carbonate rocks.

The FC samples have δ13C values ranging from -4.67 to -0.87‰ VPDB (average -2.47‰ VPDB), and δ18O values from -13.3% to -7.3‰ VPDB (average -9.8‰ VPDB). The δ13C values of the PC samples vary from -0.9 ‰ to 0.72‰ VPDB (average -6.15‰ VPDB), and their δ18O values vary from -6.8‰ to -5.46‰ VPDB (average -13.08‰ VPDB).

The CC samples have δ

13C values ranging from -4.26‰ to -1.50‰ VPDB (average -2.62‰ VPDB), and δ

18O values from -14.17‰ to -7.96‰ VPDB (average -12.65‰ VPDB). In addition to the CM samples, the O and C isotope values of other samples also exhibit an obvious negative offset. The negative δ

18O values in calcite are mainly caused by the interference of external fluids during late diagenesis, such as atmospheric fresh water with poor δ

18O and hydrothermal fluids with higher temperature causing δ

18O values to decrease [

43,

57]. The isotopic composition of C in CO

2 is different due to variations in fluid sources and forming environments. CO

2 was released from mantle magma degassing with δ

13C values in the range of -7‰ to -5‰, produced by the transformation of organic matter with δ

13C values ranging from -30‰ to -10‰, and released from carbonate minerals in clastic sedimentary or argillaceous rocks with δ

13C values ranging from -15‰ to -9‰[

57].

4.3.2. Sr Isotope

The 87Sr/86Sr ratios of Middle and Lower Ordovician CM ranged from 0.708741 to 0.708813 (average 0.708770) (

Table 1), and the

87Sr/

86Sr ratios in study area are mostly located in the range of Ordovician marine carbonate as determined by Denison (Denison et al., 1998). The PC samples have

87Sr/

86Sr ratios ranging from 0.708176 to 0.709883 (average 0.708927); except for one sample with a very high value (0.709883), the range is the same as that for CM samples. The FC and CC samples have

87Sr/

86Sr ratios ranging from 0.709221 to 0.710177 (average 0.709601), and 0.709 to 0.71012 (average 0.709359), respectively (

Figure 12). High

87Sr/

86Sr ratios indicate the contribution of external sources and other rich

87Sr fluids, such as crust source Sr provided by meteoric freshwater. Deep intermediate acid volcanic rocks can also contribute to increase in

87Sr/

86Sr ratios (Lu et al., 2017; Han et al., 2019).

4.3.3. Fluid Inclusions

The evolution of petroliferous structural basins is accompanied by the formation, development, and evolution of fluids. The Ordovician reservoir in the Tahe Oilfield is a marine carbonate deposit which has experienced a long process of structural evolution, and suffered from multiple tectonic movements and structural deformations. The fluid inclusions in calcite veins in different parts of the Ordovician carbonate strata record the temperature, pressure, and other thermodynamic information of different periods throughout the tectonic history. The characteristics of homogenization temperatures of fluid inclusions in carbonates in southern area of Tahe Oilfield are presented in

Figure 13. The homogenization temperature of fluid inclusions varied from 43.2 ºC to 261.3 ºC; these are divided into three groups based on distribution range of homogenization temperature of fluid inclusions : < 60 to 140 ºC, 140 to 170 ºC, and 170 ºC to more than 200 ºC.

5. Discussion

5.1. Fluids Types and Evolution Constraints According to Petrological and Geochemical Characteristics

The Ordovician carbonate strata in the Tahe Oilfield are deeply buried and have experienced multi-stage tectonic movement and fault activity. These thick carbonates have been subjected to transformation by multi-stage fluid dissolution; they have also formed various types and generations of carbonate cements. Optical photomicrographs, CL, and core samples indicate that five generations of cement or fractures/cave-filling calcites formed during burial diagenetic evolutionary history.

The first stage calcite (C1) was formed in the syngenetic-contemporaneous period. Under the action of atmospheric fresh water, the internal selective dissolution of carbonate rock particles formed mold pores, or intragranular pores filled with calcites (

Figure 14a). The second stage calcite (C2) is generally fine-grained and grows around carbonate particles (

Figure 14a and b). The third generation cemented calcite has coarse grains and a rough crystal surface, which is filled in the residual intergranular pores after the formation of the second generation calcite (

Figure 14a and b). The C2 and C3 are mainly formed by burial dissolution and cementation. The fourth stage calcite (C4) is a clean calcite filled with dissolution pores, showing a bright orange ring under CL. The fifth stage calcite (C5) is a clean medium coarse crystal calcite with bright orange rings under CL (

Figure 14c, d, e and f). Both the C4 and C5 are related to hydrothermal fluids.

In the three intervals of homogenization temperatures of fluid inclusions (

Figure 13), there were three phases of fluids with different temperatures participating in diagenesis. The data support a wide distribution range in the low temperature section, indicating the homogenization temperature of fluid inclusions in the medium deep burial diagenetic environment. These diagenetic fluids were mainly atmospheric fresh water and formation fluids. Two abnormal sections of high temperature data indicate the dissolution of hydrothermal fluids at different temperatures during two separate periods.

The δ

18O values of calcite cement in the Middle-Lower Ordovician carbonate rocks in the study area are clearly negative; the minimum value reached 14.17 ‰ VPDB. The negative δ

18O values may be attributed to the meteoric water and deep hydrothermal fluids. During the middle Caledonian, Early Hercynian, and Late Hercynian tectonic movements, the Tahe Oilfield formed multi-stage structural faults, which provided favorable conditions for atmospheric fresh water to enter this thick carbonate formation through otherwise impermeable layers. At the same time, there were four important volcanic events in the Tarim Basin history, including the Permian volcanic activity in the Late Hercynian, which was the most active, and distributed over a large area. Hydrothermal fluids derived from magma moved upward along the fault, which led to a rise in temperature of the formation fluid. From the perspective of isotopic equilibrium fractionation, temperature controls the isotope fractionation coefficient of water rock reactions. The highest temperatures of extrusive volcanic rock can reach thousands of degrees, and these differentiated hydrothermal fluids have a very high temperature, resulting in the negative shift of δ

18O values of calcite cement, along with a large migration range. However, the negative δ

18O migration degree of calcite cement formed by atmospheric fresh water is relatively small. The HCO

3- content in meteoric freshwater is affected by CO

2 in the atmosphere, and δ

13C shows a partial negative shift. Deep magmatism can also release more CO

2, which provides δ

13C with a slight negative migration. When atmospheric fresh water mixes with formation water, the isotopic characteristics of the mixed fluids are between those of atmospheric fresh water and formation water (

Figure 15a).

The atmospheric fresh water concentrate large quantities of

87Sr, which seeps into the carbonate rocks along the faults, thus increasing the

87Sr/

86Sr value. At the same time, the hydrothermal fluid formed by magmatism also forms calcite veins with high 87Sr/86Sr value (

Figure 15b).

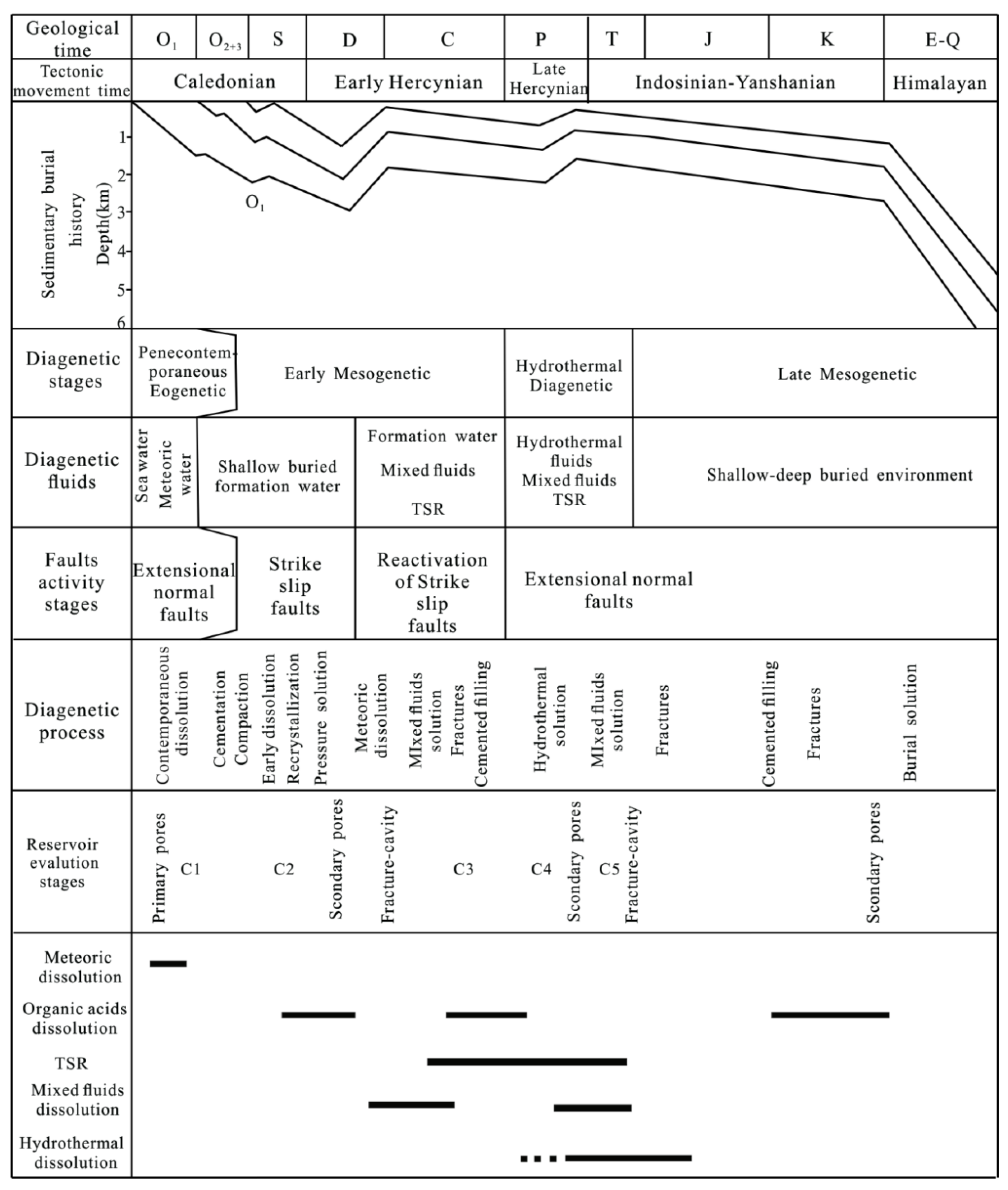

5.1.2. Diagenesis and Fluid Evolution

Based on petrological observations, fluid inclusions, and isotopic data, the diagenetic processes can be broadly divided into four stages: penecontemporaneous eogenetic, early mesogenetic diagenetic, hydrothermal diagenetic, and late mesogenetic diagenetic [

61].

These carbonate strata experienced multiple tectonic uplifting movements and suffered from meteoric freshwater dissolution in the penecontemporaneous eogenetic stage, which occurred during the first episode of the Middle Caledonian and main diagenetic processes, and included selective dissolution and calcite cementation (Jia et al., 2016). It can be observed that a large number of intergranular pores and moldic pores are filled with abundant cements (C1).

With the decline of tectonic movement during a stable sedimentary placement period, the study area entered the early mesogenetic diagenesis stage[

14]. The main diagenetic process includes secondary dissolution, pressure solution, recrystallization, compaction, cementation, and filling[

62]. The dissolution of the constructive diagenetic process includes both buried and mixed fluids dissolution. The pores and cavities formed during this period are mostly filled by calcite and other minerals, e.g., C2 and C3. In the middle deep burial stage, the organic matter in the source rock produced acidic fluids rich in organic acids, CO

2, and H

2S in the mature stage. When the acid fluid is unsaturated to calcium carbonate, it will be extremely corrosive to the carbonate rock[

63]. The δ

18O and δ

13C values of calcite range from -6.8‰ to -5.5‰ VPDB, and -1.5‰ to 0.72‰ VPDB, respectively. The homogenization temperature of fluid inclusions varied from 60 ºC to 90 ºC. The dissolution process of mixed fluids is relatively complex. During the second and third episodes of the Middle Caledonian and Early Hercynian, a large number of large-scale strike slip faults formed, and a large number of associated fractures formed around these faults[

64]. These fault systems directly communicated with the surface and had contact with the meteoric freshwater environment. The atmospheric fluids penetrated downward along the fault zone and dissolved the carbonate rock, forming pores and cavities. As the calcium carbonate in the fluid gradually reaches the saturation state, the dissolution weakened. However, when the saturated fluids mixed with formation water, the dissolution occurred again; therefore, the δ

18O and δ

13C values of calcite cements are between those of meteoric freshwater and formation water, ranging from -10.8‰ to -8.2‰ VPDB, and -2.6‰ to -0.87‰ VPDB, respectively.

From the Early to Late Permian period, intense magmatic activities occurred in the Tabei Uplift region. High temperature hydrothermal fluids differentiated from the magma, which was rich in CO2, H2S, SO2, and other volatile substances. The dissolving hydrothermal fluid migrated along the faults to the soluble carbonate rock stratum, and flowed laterally along the fractures and within the early dissolution cavities, resulting in different degrees of dissolution on the carbonate rock, leading to the formation of superimposed and transformed pores and caves. Similarly, some minerals such as calcites and hydrothermal products filled in the secondary pores and caves that formed in the early stage (C4 and C5). Hydrothermal associated minerals such as dolomite, quartz, barite, and fluorite precipitated in the fractures and dissolution cavities. The δ18O and δ13C values of calcite range from -14.17‰ to -11.8‰ VPDB, and -4.67‰ to -1.3‰ VPDB, respectively. The homogenization temperature of fluid inclusions varied from 160 ºC to 200 ºC. The hydrothermal fluid has a high temperature; hence, when hydrocarbons enter into carbonate stratum and oxidation reduction reaction between sulfate and hydrocarbon happened, thermochemical sulfate reactions (TSRs) occur, and a large amount of acidic substances such as CO2 and SO2 are produced. These acidic substances dissolved in the hydrothermal solution have very strong corrosivity; if these substances continue to move upward, they will further corrode and transform the early dissolution pores.

As the basin entered the stable sedimentary stage, the diagenetic stage evolved into the late mesogenetic diagenesis. During this period, tectonic and TSR dissolution were the main factors that affected the pores, while cementation, compaction and filling were the main destructive factors.

5.2. Effect of Faults on Carbonate Reservoir Development

Faults are not only the main migration channel of underground fluid, but also the main region of carbonate reservoirs development[

37,

65]. Different faults develop different complex internal structural characteristics within a fault zone[

66]. In turn, fault zones are composed of complex fracture networks, which provide seepage channels for the surface fluids to flow into the deep strata[

67]. Different properties of faults have obvious differences in their control of fracture development. The regions of faults intersection formed multiple groups of fracture systems, which were then affected by multi-stage stress fields. The development of fractures improves the physical properties of carbonate rock for fluid accumulation; hence, the fault intersections are favorable for carbonate hydrocarbon reservoir development. All or most intersections are distributed within fault zones or develop on both sides of fault zones, which indicates that these zones are the most developed for fracture cavities to develop into reservoirs (

Figure 16 and

Figure 17). Similarly, the fracture cave reservoirs predicted from the amplitude change rate attribute map are mostly distributed on both sides of the fault zones, at the tips of the fault lines, and within the overlapping area between the two faults. The fracture cave reservoirs are distributed in short strips along direction of the fault extension (

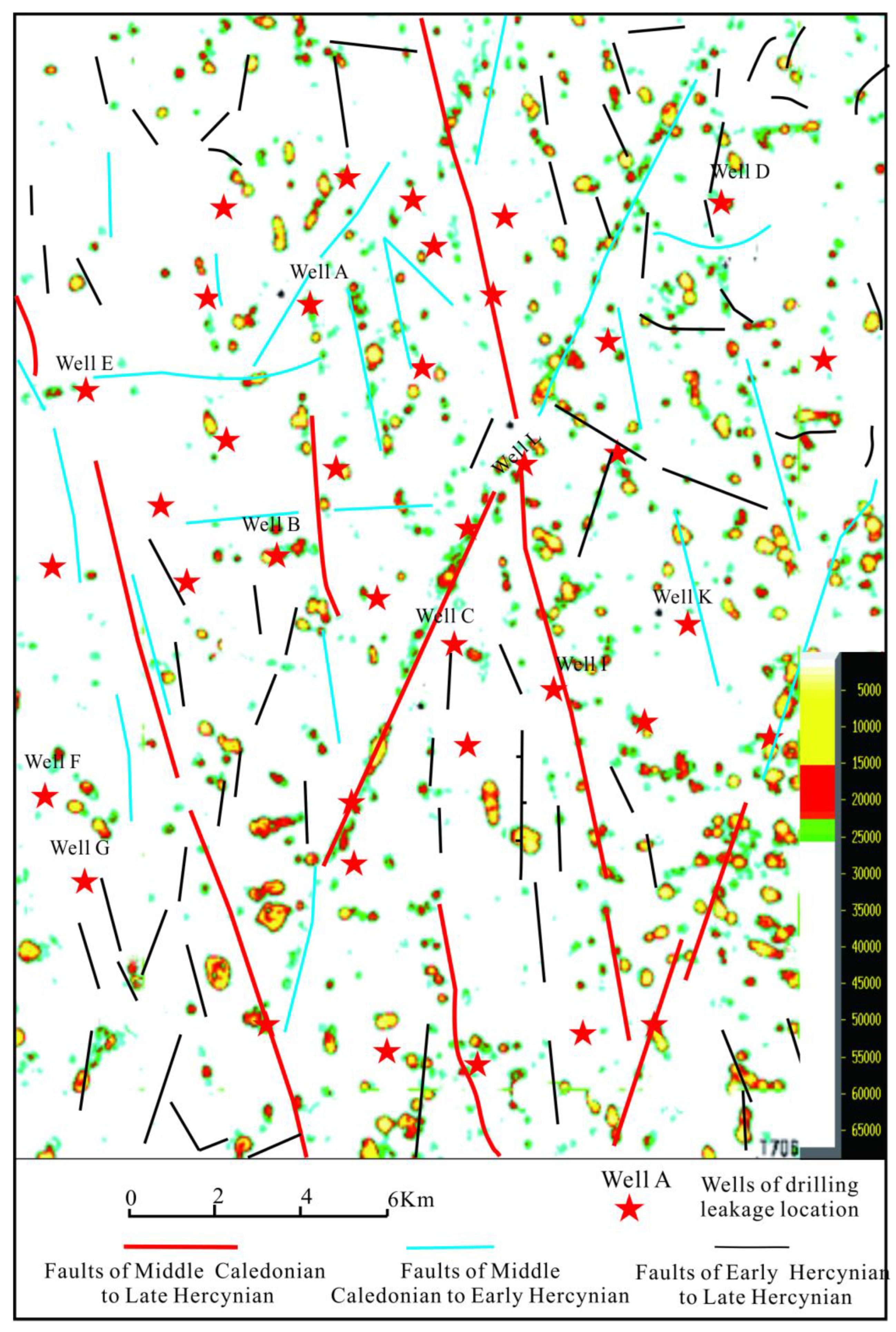

Figure 18).

There are obvious differences in the controlling effect of faults formed in different active periods on the distribution of carbonate reservoirs. The fracture cave reservoirs developed near the NE and NW trending strike slip fault, where the drilling leakage phenomenon was obvious. The longer the duration of fault activity, the stronger the karstification, and more corrosion fractures and caves formed. Therefore, the control effect of faults formed during both the Middle Caledonian to Late Hercynian, and the Middle Caledonian to Late Hercynian on reservoir distribution and hydrocarbon enrichment are obviously stronger (

Figure 18). These multi-stage inherited faults clearly controlled the fracture cave reservoirs. Most of the faults that formed in the Middle Caledonian continued to be active during the Early Hercynian and Late Hercynian. Therefore, these faults continued downward into the basement or upward towards the surface, providing pathways for the upward and downward migration of deep hydrothermal fluids or atmospheric fresh water. The fault zones are also where dissolution was strongest, which helped control the development of deep reservoirs.

5.3. Effect of Strike Slip Faults and Diagenetic Fluids on the Origin and Evolution of Carbonate Reservoirs

There are several types of dissolution that can occur during a geological period. Dissolution processes during different geological periods transform and overlap with each other, forming complex carbonate reservoirs (

Figure 19).

After the deposition of the Yijianfang Formation (O1-2yj), a tectonic uplift occurred during the Middle Caledonian, and the Tarim Basin was compressed in the N-S direction. Due to the relatively weak influence of tectonic movements in the Tabei area, some small-scale faults and fracture systems were formed. The carbonate reefs and shoals were exposed to the sea for a short time. The carbonate rocks were leached by atmospheric fresh water, and paracontemporaneous diagenesis occurred, without compaction, pressure solution, and cementation.

The third episode of the Middle Caledonian tectonic movement occurred at the end of the Sangtamu Formation (O3s). The NNW and NNE strike slip faults formed under N-S compression stress; some of these faults were inherited. During this period, the faults broke through the T70 interface, continuing downward to the T90 interface. Atmospheric fresh water infiltrated the carbonate formation through the fault zone, and a large amount of organic acids were generated. However, due to the short tectonic uplift and stability during this period, some small isolated dissolution caves and fractures developed.

The Early Hercynian is the most important tectonic movement for the formation and development of fault-controlled carbonate reservoirs in the study area. Under the action of NW-SE trending regional stress, the inherited strike slip faults in the Middle Caledonian developed strong activity along the scale and the width of the fault zone became larger. At the same time, a series of NNW, NW, and NE trending faults and folds formed. These large-scale strike slip faults extended upward to the T

57 interface and downward to the T

90. The faults connecting the surface provided the long-term conditions for atmospheric fresh water to penetrate and dissolve the Middle and Lower Ordovician limestone strata along the faults and fracture zones. TSR occurred deep within the formation, which generated significant amounts of H

2S and CO

2 during the thermal degradation of the organic matter in the strata. The dissolution fluids converges to the fault zone and migrates upward to where fractures and dissolution vuggy formed in the early stage, occurs dissolution transformation to form new reservoirs.The well-preserved large-scale karst caves, the dissolution vuggy layer, and fracture reservoir were clearly controlled by faults and were found distributed along the fault zones (

Figure 20).

During the late Hercynian tectonic uplift at the end of Permian, more faults developed and some of them broke through the surface of the Kalashayi Formation. Hydrothermal fluids associated with volcanic activities during this period converged in the fault zone and migrated upward. At the same time, TSR and volcanic activities released a large amount of CO

2 and H

2S acid gas, which dissolved in the water and contributed to dissolution of the carbonate rock. Meteoric water migrated to these deep strata along the fault zone from the surface, dissolving the carbonate rock, and improving its permeability. The mixing of atmospheric fresh water, hydrothermal fluids, and formation water also enhanced the dissolution ability of the fluids. Karstification had the effect of superimposing the dissolution effects on the reservoir formed in the earlier stage, further enlarging the scale of the reservoir, while simultaneously forming some new reservoirs (

Figure 21).

6. Conclusions

(1) The Ordovician carbonate reservoirs in the southern Tahe Oilfield were not generated by weathering crust karstification because of the shielding effect of the Upper Ordovician strata in southarea of Tahe oilfield. The carbonate reservoirs in this area were divided into three types: dissolved pores, fractures, and caves.

(2) These strata experienced three stages of large-scale geologic events, namely, the Middle Caledonian, Early Hercynian and Late Hercynian tectonic movements, which played an important role in the development of fracture-vuggy reservoirs. Further, four stages of fault systems are classified: extensional faults in the Cambrian-Early Ordovician, strike-slip faults in the Middle Ordovician, reactivation of strike-slip faults in the Silurian-Devonian, and faults related to volcanic activities in the Permian.

(3) Four dominate types of diagenetic fluids, such as meteoric water, formation water, hydrothermal fluid, and mixed fluids, played an important role in the development of carbonate reservoirs, with particular contributions of mixed fluids and hydrothermal fluids.

(4) The mixed dissolution of meteoric water is coupled with two stages of tectonic faults: the Early Hercynian and Late Hercynian.; the most important contribution to the reservoir occurred in the Early Hercynian. Hydrothermal dissolution mainly occurred during the large-scale volcanic activities in the Late Hercynian. TSR dissolution mainly occurred from the Early Hercynian to Late Hercynian, with certain dissolution capacity. Organic acid dissolution within formation water occurred during the subsidence burial period, which mainly occurred in the Late Caledonian, Late Hercynian, and Yanshanian-Himalayan.

7. Patents

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 42562022), National Science and Technology Major Project (Project No. 2025ZD1402300), the Foundation of Sinopec KeyLaboratory of Enhanced oil Recovery for Fractured Vuggy Reservoirs , for the financial support. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments for improving the manuscript.

References

- Zenger, D.H.; Junham, J.B.; Ethington, R.L. 1980. Concepts and models of dolomitization. SEPM Special Publication 28, 320 pp.

- Pang, X.Q.; Jia, C.Z.; Pang, H.; Yang, H.J. Destruction of hydrocarbon reservoirs due to tectonic modifications: Conceptual models and quantitative evaluation on the Tarim Basin, China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2018, 91, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousufia, M.M.; Elhaja, M.E.M.; Moniruzzamanb, M.; Abdalla, M. A review on use of emulsified acids for matrix acidizing in carbonate reservoirs. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2018, 13, 8151–8164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.L.; Zhang, J.T.; Ding, Q.; You, D.H.; Peng, S.T.; Zhu, D.Y.; Qian, Y.X. Factors controlling the formation of high-quality deep to ultra-deep carbonate reservoirs. Oil and Gas Geology 2017, 38, 633–644. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.S.; He, Z.L.; Zhao, P.R.; Zhu, H.Q.; Han, J.; You, D.H.; Zhang, J.T. A new progress in formation mechanism of deep and ultra-deep carbonate reservoir. Acta Petrolei Sinica 2019, 40, 1415–1425. [Google Scholar]

- IHS. Energy-world Houston, Texas[EB/OL].[2014-09-01].

- Yun, L.; Zhai, X.X. Discussion on characteristics of the Cambrianreservoirs and hydrocarbon accumulation in Well Tashen 1. Tarim Basin. Oil and Gas Geology 2008, 29, 726–732. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Meng, Q.; Jin, Z.; Liu, Q.; Hu, W. Formation mechanism of deep Cambrian dolomite reservoirs in the Tarim Basin,northwestern China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2015, 59, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.Y.; Zou, C.N.; Yang, H.J.; Wang, K.; Zheng, D.M.; Zhu, Y.F.; Wang, Y. Hydrocarbon accumulation mechanisms and industrial exploration depth of large-area fracture–cavity carbonates in the Tarim Basin, western China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2015, 133, 889–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.H.; Zhao, K.Z.; Qu, H.Z.; Nicola, S.; Zhang, Y.T.; Han, J.F.; Xu, Y.F. Permeability distribution and scaling in multi-stages carbonate damage zones: Insight from strike-slip fault zones in the Tarim Basin, NW China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.D.; Lü, X.X.; Zhu, Y.M.; Yu, H.F. The geometry and origin of strike-slip faults cutting the Tazhong low rise megaanticline (central uplift, Tarim Basin, China) and their control on hydrocarbon distribution in carbonate reservoirs. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2015, 22, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.Q.; Jia, C.Z.; Pang, H.; Yang, H.J. Destruction of hydrocarbon reservoirs due to tectonic modifications: Conceptual models and quantitative evaluation on the Tarim Basin, China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2018, 91, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, M.S.; Brassell, A.C.; Carroll, A.R.; Graham, S.A. Sedimentology, organic geochemistry, and petroleum potential of Jurassic coal measures: Tarim, Junggar, and Turpan basins, northwest China. AAPG Bulletin 1995, 79, 929–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.J.; Zhu, D.Y.; Hu, W.X.; Zhang, X.F.; Zhang, J.T.; Song, Y.C. Mesogenetic dissolution of the middle Ordovician limestone in the Tahe oilfield of Tarim basin, NW China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2009, 26, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Lu, X.B.; Tian, J.J.; Ren, L.H.; Ma, C.F. Petrological and geochemical constraints on fluid types and formation mechanisms of the Ordovician carbonatereservoirs in Tahe Oilfield, Tarim Basin, NW China. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2019, 178, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, N.; Zhang, S.N.; Qing, H.R.; Lie, Y.T.; Huang, Q.Y.; Liu, D. Dolomitization and its impact on porosity development and preservation in the deeply burial Lower Ordovician carbonate rocks of Tarim Basin, NW China. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, R.G.; Mescher, P.K.; McMechan, G.A. Three-dimensional architecture of a coalesced, collapsed paleocave system in the Lower Ordovician Ellenburger Group, central Texas. AAPG Bull. 2004, 88, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Loucks, R.; Janson, X.; Wang, G.; Xia, Y.; Yuan, B.; Xu, L. Three dimensional seismic geomorphology and analysis of the Ordovician paleokarst drainage system in the central Tabei Uplift, northern Tarim Basin, western China. AAPG Bull. 2011, 95, 2061–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Wang, G.; Janson, X.; Loucks, R.; Xia, Y.; Xu, L.; Yuan, B. Characterizing seismic bright spots in deeply buried, ordovician paleokarst strata, Central tabei uplift, tarim Basin, western China. Geophysics 2011, 76, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.X.; Jia, C.Z.; Gao, R.S. Sedimentation characteristics and reservoir geological model of Mid -Lower Ordovician carbonate rock in Tazhong northern slope. Acta Pet. Sin. 2012, 33 (Suppl. 1), 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Zhu, G.; Wang, Y.; Su, J.; Zhang, B. The geological characteristics of reservoirs and major controlling factors of hydrocarbon accumulation in the Ordovician of Tazhong area, Tarim Basin. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2014, 32, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Jin, Q.; Lu, X.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, S.; Liu, N. Multi-layered Ordovician paleokarst reservoir detection and spatial delineation: A case study in the Tahe Oilfield, Tarim Basin, Western China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2016, 69, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Lu, X.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, H.; Rong, Y.; Yang, D.; Liu, N. Structure and filling characteristics of paleokarst reservoirs in the northern Tarim Basin, revealed by outcrop, core and borehole images. Open Geosci. 2017, 9, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.B.; Wang, Y.; Tian, F.; Li, X.; Yang, D.; Li, T.; He, X. New insights into the carbonate karstic fault system and reservoir formation in the Southern Tahe area of the Tarim Basin. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2017, 86, 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Luo, X.R.; Zhang, W. Integrated geological-geophysical characterizations of deeply buried fractured-vuggy carbonate reservoirs in Ordovician strata, Tarim Basin. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2019, 99, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.H.; Yang, H.J.; He, S.; Cao, S.J.; Liu, X.; Jing, B. Effects of structural segmentation and faulting on carbonate reservoir properties: A case study from the Central Uplift of the Tarim Basin, China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2016, 71, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xue, Z.J.; Cheng, Z.; Jiang, H.J.; Wang, R.Y. Progress and development directions of deep oil and gas exploration and development in China. China Petroleum Exploration 2020, 25, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, H.; Loucks, R.; Janson, X.; Wang, G.; Xia, Y.; Yuan, B.; Xu, L. Three dimensional seismic geomorphology and analysis of the Ordovician paleokarst drainage system in the central Tabei Uplift, northern Tarim Basin, western China. AAPG Bull. 2011, 95, 2061–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.B.; Hu, W.G.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.H.; Li, T.; Lv, Y.P.; He, X.M.; Yang, D.B. Characteristics and development practice of fault-karst carbonate reservoirs in Tahe area, Tarim Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2015, 36, 347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S.; Li, Z.; Jiang, L. The ordovicianesilurian tectonic evolution of the northeastern margin of the tarim block, NW China: Constraints from detrital zircon geochronological records. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2016, 122, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.Y.; Chen, H.H.; Qing, H.R.; Chi, G.X.; Chen, Q.L.; You, D.H.; Yin, H.; Zhang, S.Y. Petrography, fluid inclusion and isotope studies in Ordovician carbonate reservoirs in the Shunnan area, Tarim basin, NW China: Implications for the nature and timing of silicification. Sedimentary Geology 2017, 359, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Sanderson, D.J. Structural similarity and variety at the tips in a wide range of strike–slip faults: A review. Terra Nova 2006, 18, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A.; Berryman, J.G. Analysis of the growth of strike-slip faults using effective medium theory. J. Struct. Geol. 2010, 32, 1629–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storti, F.; Billi, A.; Salvini, F. Particle size distribution in natural carbonate fault rocks: Insights for non-self similar cataclasis. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2003, 206, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micarelli, L.; Benedicto, A.; Wibberley, C.A.J. Structural evolution and permeability of normal fault zones in highly porous carbonate rocks. Journal of Structural Geology 2006, 28, 1214–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosta, F.; Prasad, M.; Aydin, A. Physical properties of carbonate fault rocks, Fucino basin (Central Italy): Implications for fault seal in platform carbonates. Geofluids 2007, 7, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, C.; Manzocchi, T.; Walsh, J.J.; Bonson, C.G.; Nicol, A.; Schöpfer, M.P.J. A geometric model of fault zone and fault rock thickness variations. J. Struct. Geol. 2009, 31, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Edwards, P.; Ko, K.; Kim, Y.S. Definition and classification of fault damage zones: A review and a new methodological approach. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2016, 152, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosta, F.; 2008. Fluid flow properties of basin-bounding normal faults in platform carbonates, Fucino Basin, central Italy. In: Wibberley, C.A.J.; Kurz, W.; Imber, J.;Holdsworth, R.E.; Collettini, C. (Eds.), The Internal Structure of Fault Zones: Implications for Mechanical an1d Fluid-flow Properties. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 299, 277–291.

- Williams, R.T.; Goodwin, L.B.; Mozley, P.S. Diagenetic controls on the evolution of fault-zone architecture and permeability structure: Implications for episodicity of fault-zone fluid transport in extensional basins. GSA Bull. 2017, 129, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.H.; Zhao, K.Z.; Qu, H.Z.; Nicola, S.; Zhang, Y.T.; Han, J.F.; Xu, Y.F. Permeability distribution and scaling in multi-stages carbonate damage zones: Insight from strike-slip fault zones in the Tarim Basin, NW China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arosi, H.A.; Wilson, M.E.J. Diagenesis and fracturing of a large-scale, syntectonic carbonate platform. Sediment. Geol. 2015, 326, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.Q. Sulfur isotopic compositions of individual organosulfur compounds and their genetic links in the Lower Paleozoic petroleum pools of the Tarim Basin, NW China. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2016, 182, 88–108. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Wei, T.; Dong, C.; Ren, L.H.; Zhang, X.G.; Dong, L.; Zhao, X. Paleogeomorphology restoration and the controlling effects of paleogeomorphology on karst reservoirs: A case study of an ordovician-aged section in Tahe oilfield, Tarim Basin, China. Carbonates & Evaporites 2019, 34, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Feng, C.; Wang, L.; Li, C. Measurement and analysis of thermal conductivity of rocks in the Tarim Basin, Northwest China. Acta Geologica Sinica-English Edition 2011, 85, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.J.; Chen, H.H.; Tang, D.Q.; Cao, Z.C.; Lu, Z.Y.; Su, A.; Wei, H.D. Coupling relationship between ne strike-slip faults and hypogenic karstification in Middle-Lower Ordovician of Shunnan Area, Tarim Basin, Northwest China. Earth Sci. 2017, 42, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.C.; Qiu, N.S.; Li, H.L.; Ma, A.L.; Chang, J.; Jia, J.K. Terrestrial heat flow and crustal thermal structure in the northern slope of Tazhong uplift in Tarim Basin. Geothermics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Zhang, X.F.; Wang, C.W.; Li, P.P.; Guo, T.L.; Zou, H.Y.; Zhu, Y.M.; Liu, J.Z.; Cai, Z.X. The fate of CO2 derived from thermochemical sulfate reduction (TSR) and effect of TSR on carbonate porosity and permeability, Sichuan basin, China. Earth Sci. Rev. 2015, 141, 154–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.F.; Hu, G.Y.; Li, H.X.; Jiang, L.; He, W.X.; Zhang, B.S.; Jia, L.Q.; Wang, T.K. Origins and fates of H2S in the Cambrian and Ordovician in Tazhong area: Evidence from sulfur isotopes, fluid inclusions and production data. Mar. Petroleum Geol. 2015, 67, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.F.; Amrani, A.; Worden, R.H.; Xiao, Q.L.; Wang, T.K.; Gvirtzman, Z.; Li, H.X.; SaidAhmad, W.; Jia, L.Q. Sulfur isotopic compositions of individual organosulfur compounds and their genetic links in the Lower Paleozoic petroleum pools of the Tarim Basin, NW China. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2016, 182, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.B.; Li, Z.; Yang, L. Fault system impact on paleokarst distribution in the Ordovician Yingshan Formation in the central Tarim basin, northwest China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2016, 75, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.X.; Wang, X.F.; Li, B.L.; He, D.F. Paleozoic fault systems of the Tazhong Uplift, Tarim Basin, China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2013, 39, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.Y.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Zhou, X.X.; Lia, T.T.; Han, J.F.; Sun, C.H. The complexity, secondary geochemical process, genetic mechanism and distribution prediction of deep marine oil and gas in the Tarim Basin, China. Earth-Science Reviews 2019, 39, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Di, Q.Y.; Jin, Q.; Cheng, F.Q.; Zhang, W.; Lin, L.M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, D.B.; Niu, C.K.; Li, Y.X. Multiscale geological-geophysical characterization of the epigenic origin and deeply buried paleokarst system in Tahe Oilfield, Tarim Basin. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2019, 102, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Jian, P.; Zheng, H.F.; Zou, H.B.; Zhang, L.F.; Liu, D.Y. U-Pb zircon geochronology and geochemistry of Neoproterozoic volcanic rocks in the Tarim Block of northwest China: Implications for the breakup of Rodinia supercontinent and Neoproterozoic glaciations. Precambrian Research 2005, 136, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.H.; Sun, J.H.; Guo, Q.Y.; Tang, T.; Chen, Z.Y.; Feng, X.J. The distribution of detrital zircon UePb ages and its significance to Precambrian basement in Tarim Basin. Acta Geoscientica Sinica 2010, 31, 64–72, (in Chinese with abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Yu, B.S.; Gong, H.N.; Ruan, Z.; Pan, Y.L.; Ren, Y. Carbonate reservoirs modified by magmatic intrusions in the Bachu area, Tarim Basin, NW China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2015, 6, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Wang, G.; Janson, X.; Loucks, R.; Xia, Y.; Xu, L.; Yuan, B. Characterizing seismic bright spots in deeply buried, ordovician paleokarst strata, Central Tabei uplift, Tarim Basin, western China. Geophysics 2011, 76, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.L.; Fan, T.L.; Yu, B.S.; Huang, X.B.; Liu, C. Ordovician carbonate reservoir fracture characteristics and fracture distribution forecasting in the Tazhong area of Tarim Basin, Northwest China. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2012, 86–87, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.C.; Tian, J.J.; Hu, C.L.; Liu, H.L.; Wang, W.F.; Huan, Z.P.; Feng, S. Lithofacies characteristics and their controlling effects on reservoirs in buried hills of metamorphic rocks: A case study of late Paleozoic units in the Aryskum depression, South Turgay Basin, Kazakhstan. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2020, 191, 107–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngong, R.N.; Hu, M.Y.; Gao, D. Tectonic and geothermal controls on dolomitization and dolomitizing fluid flows in the Cambrian-Lower Ordovician carbonate successions in the western and central Tarim basin, NW China. Journal of Asian Earth sciences 2019, 172, 359–382. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Fan, T.L.; Gao, Z.Q.; Yin, X.X.; Fan, X.; Li, C.C.; Yue, W.Y.; Lia, C.; Zhang, C.J.; Zhang, J.H.; Sun, X.N. A conceptual model to investigate the impact of diagenesis and residual bitumen on the characteristics of Ordovician carbonate cap rock from Tarim Basin, China. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2018, 168, 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.P.; Hao, F.; Zhang, B.Q.; Zou, H.Y.; Yu, X.Y.; Wang, G.W. Heterogeneous distribution of pyrobitumen attributable to oil cracking and its effect on carbonate reservoirs: Feixianguan Formation in the Jiannan gas field, China. AAPG Bull. 2015, 99, 763–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Kang, Z.H.; Li, P.; Rong, Y.M.; Dai, H.B. Development characteristics and geological model of Ordovician karst carbonate reservoir space in Tahe oilfield. Geoscience 2013, 27, 356–365. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, N.H.; Sayers, N.J.; Dickson, J.A. Fluid flow history from damage zone cements near the dent and Rawthey faults, NW England. Journal of the Geological Society 2008, 165, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, D.; Evans, J.P. Fault architecture, linkage and internal structure: Field examples from the iron wash fault zone, central Utah. Gulf Coast Association of Geological Societies 2013, 42, 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Bonson, C.G.; Childs, C.; Walsh, J.J.; SchPfer, M.P.J.; Carboni, V. Geometric and kinematic controls on the internal structure of a large normal fault in massive limestones: The maghlaq fault, malta. Journal of Structural Geology 2007, 29, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

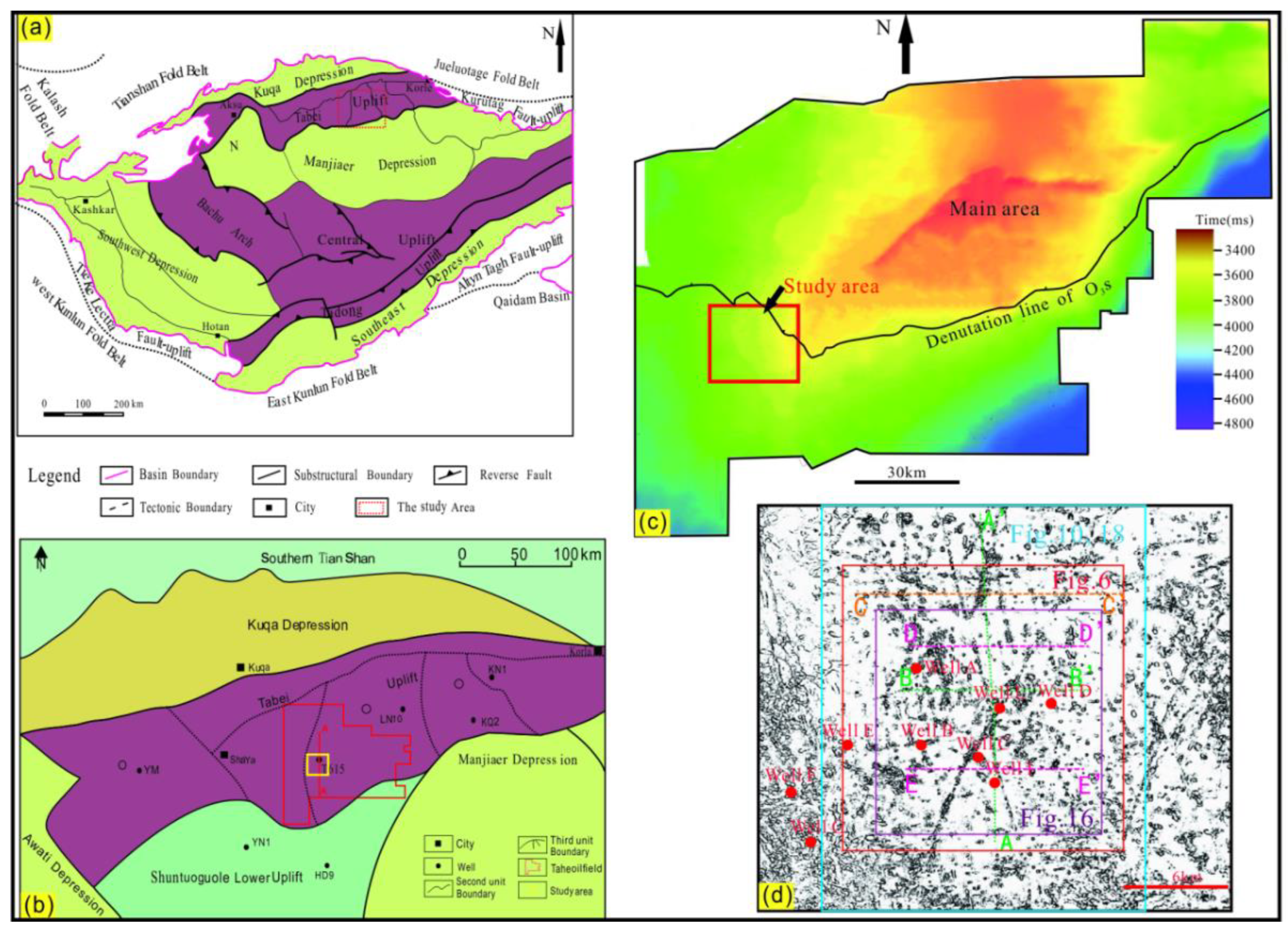

Figure 1.

Location, map and coherence attribute of the Tahe Oilfield in the Tarim Basin; (a)Tectonic outline of Tarim Basin with the studying area in the Tabei Uplift of Tarim Basin; (b) Secondary structural units in the Tabei Uplift in the Tarim Basin; (c) Paleogeomorphic map of Upper Ordovician strata in Tahe Oilfield. The study area is in the southern area of Tahe oilfield and the upper Ordovician(insoluble strata) stratum are preserved to a certain thickness; (d) Coherence attribute map of study area along T74 layer.

Figure 1.

Location, map and coherence attribute of the Tahe Oilfield in the Tarim Basin; (a)Tectonic outline of Tarim Basin with the studying area in the Tabei Uplift of Tarim Basin; (b) Secondary structural units in the Tabei Uplift in the Tarim Basin; (c) Paleogeomorphic map of Upper Ordovician strata in Tahe Oilfield. The study area is in the southern area of Tahe oilfield and the upper Ordovician(insoluble strata) stratum are preserved to a certain thickness; (d) Coherence attribute map of study area along T74 layer.

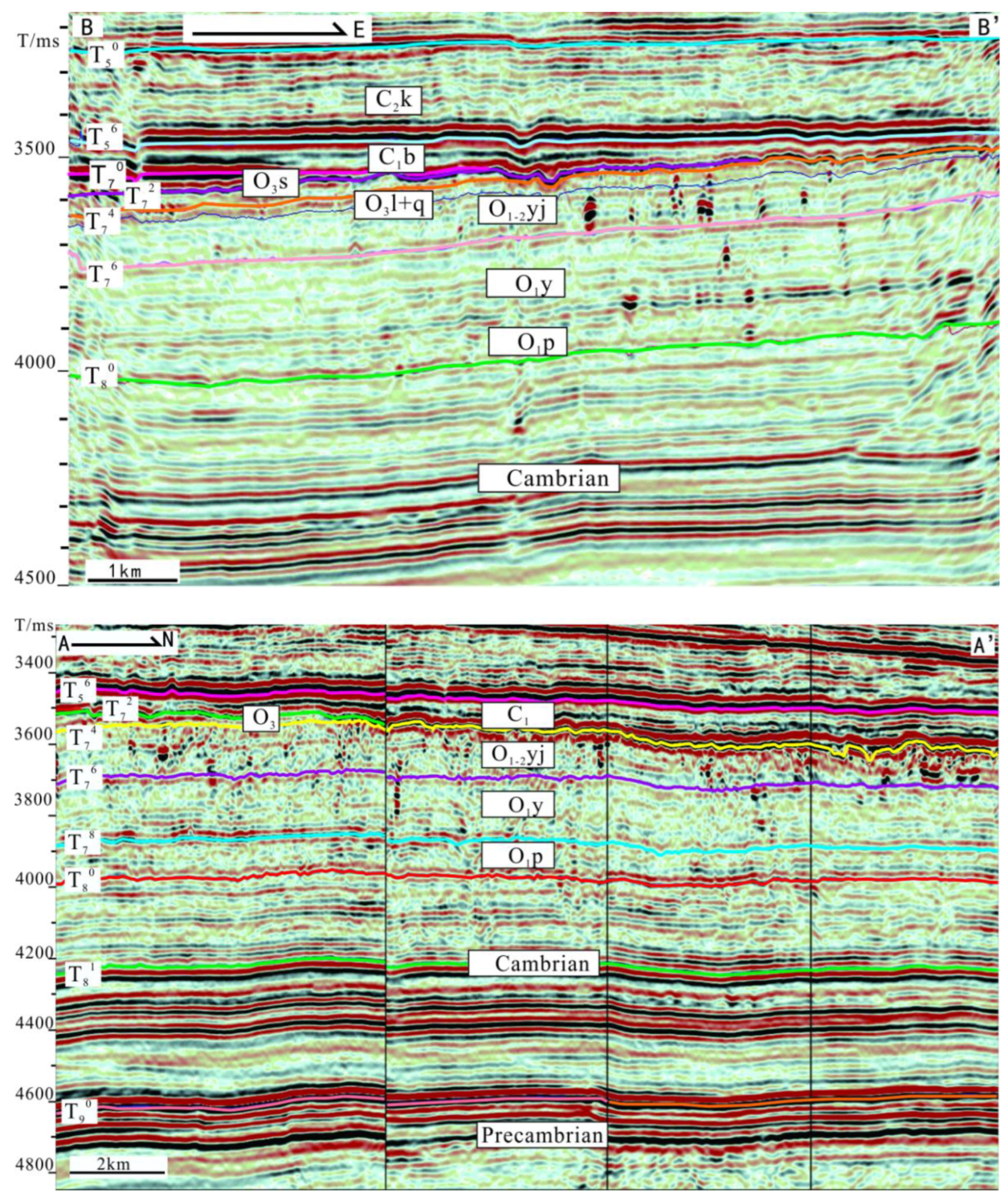

Figure 2.

Stratigraphic profiles across the southern of Tahe Oilfield. (a) Cross section A-A’, showing a N-S direction; (b). Cross section B-B’, showing a W-E direction. T56: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Carboniferous Bachu Formation; T70: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Upper Ordovician Sangtamu Formation; T72: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Upper Ordovician Lianglitage Formation ; T74: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Middle Ordovician Yijianfang Formation (mainly reservoirs);T76: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Middle-Lower Ordovician Yingshan Formation (mainly reservoirs);T78: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Lower Ordovician Penglaiba Formation; T80: the seismic reflection interface on top of Cambrian strata (mainly source rocks); T90: the seismic reflection interface on top of Precambrian strata.

Figure 2.

Stratigraphic profiles across the southern of Tahe Oilfield. (a) Cross section A-A’, showing a N-S direction; (b). Cross section B-B’, showing a W-E direction. T56: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Carboniferous Bachu Formation; T70: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Upper Ordovician Sangtamu Formation; T72: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Upper Ordovician Lianglitage Formation ; T74: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Middle Ordovician Yijianfang Formation (mainly reservoirs);T76: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Middle-Lower Ordovician Yingshan Formation (mainly reservoirs);T78: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Lower Ordovician Penglaiba Formation; T80: the seismic reflection interface on top of Cambrian strata (mainly source rocks); T90: the seismic reflection interface on top of Precambrian strata.

Figure 3.

Generalized stratigraphic column of southern area of Tahe oilfield, the formations from the Upper Cambrian to the Lower Triassic (Adapted from Tian et al., 2016). T50: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Permian; T56: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Carboniferous Bachu Formation; T70: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Upper Ordovician Sangtamu Formation; T72: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Upper Ordovician Lianglitage Formation; T74: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Middle Ordovician Yijianfang Formation; T80: the seismic reflection interface on top of Cambrian strata.

Figure 3.

Generalized stratigraphic column of southern area of Tahe oilfield, the formations from the Upper Cambrian to the Lower Triassic (Adapted from Tian et al., 2016). T50: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Permian; T56: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Carboniferous Bachu Formation; T70: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Upper Ordovician Sangtamu Formation; T72: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Upper Ordovician Lianglitage Formation; T74: the seismic reflection interface on top of the Middle Ordovician Yijianfang Formation; T80: the seismic reflection interface on top of Cambrian strata.

Figure 4.

Photographs of pores and fractures from the thin sections and cores. (a) Unfilled dissolved pore(Dp)(Well A, 6110.43m,O1-2yj); (b) Moldic pores(Mp), intergranular pore(Intergra p) and intragranular pore(Intragra p) filled with calcite(wellA, 6034.51m, O1-2yj); (c) Unfilled intragranular pore(Well A, 6067.31m,O1-2yj); (d) Microfractures and intercrystalline pores in dolomite along stylolite(Well F, 5555.61m, O1-2yj); (e) Intercrystalline pores in dolomite, unfilled(Well G, 5662.23m, O1-2yj); (f) Dissolution vugs around fracture(Well B, 5895.10m, O1-2yj).

Figure 4.

Photographs of pores and fractures from the thin sections and cores. (a) Unfilled dissolved pore(Dp)(Well A, 6110.43m,O1-2yj); (b) Moldic pores(Mp), intergranular pore(Intergra p) and intragranular pore(Intragra p) filled with calcite(wellA, 6034.51m, O1-2yj); (c) Unfilled intragranular pore(Well A, 6067.31m,O1-2yj); (d) Microfractures and intercrystalline pores in dolomite along stylolite(Well F, 5555.61m, O1-2yj); (e) Intercrystalline pores in dolomite, unfilled(Well G, 5662.23m, O1-2yj); (f) Dissolution vugs around fracture(Well B, 5895.10m, O1-2yj).

Figure 5.

Fracture information statistics from the cores(N=768).

Figure 5.

Fracture information statistics from the cores(N=768).

Figure 6.

The attribute of maximum negative curvature along the top of Middle-Lower Ordovician Yingshan Formation (T76).

Figure 6.

The attribute of maximum negative curvature along the top of Middle-Lower Ordovician Yingshan Formation (T76).

Figure 7.

Well log and geological interpretation of Well A, showing a fracture cavity reservoir. See

Figure 1d for the well location.

Figure 7.

Well log and geological interpretation of Well A, showing a fracture cavity reservoir. See

Figure 1d for the well location.

Figure 8.

A 3D topographic map of the caves in the study area generated from a 3D seismic dataset. (a) The amplitude change rate showing of fracture cavity; (b) Carving of caves body used SVI software.

Figure 8.

A 3D topographic map of the caves in the study area generated from a 3D seismic dataset. (a) The amplitude change rate showing of fracture cavity; (b) Carving of caves body used SVI software.

Figure 11.

The curvature attributes of different layer showing different stages faults. (a) Faults formed in Middle Caledonian period; (b) Faults formed in Early Hercynian period.

Figure 11.

The curvature attributes of different layer showing different stages faults. (a) Faults formed in Middle Caledonian period; (b) Faults formed in Early Hercynian period.

Figure 12.

Strontium isotope compositions of Ordovician calcite and limestone in Tahe Oilfield.

Figure 12.

Strontium isotope compositions of Ordovician calcite and limestone in Tahe Oilfield.

Figure 13.

Statistical analysis of homogeneous temperature distribution of calcite saline inclusion.

Figure 13.

Statistical analysis of homogeneous temperature distribution of calcite saline inclusion.

Figure 14.