Submitted:

19 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Motivation

1.1. Research Challenges

1.2. Research Scope and Contribution

- We propose a secure and sustainable university building access control system using a mobile credential. To this end we develop a mobile App to provide building access rights to authorize users such as staff, students, and visitors.

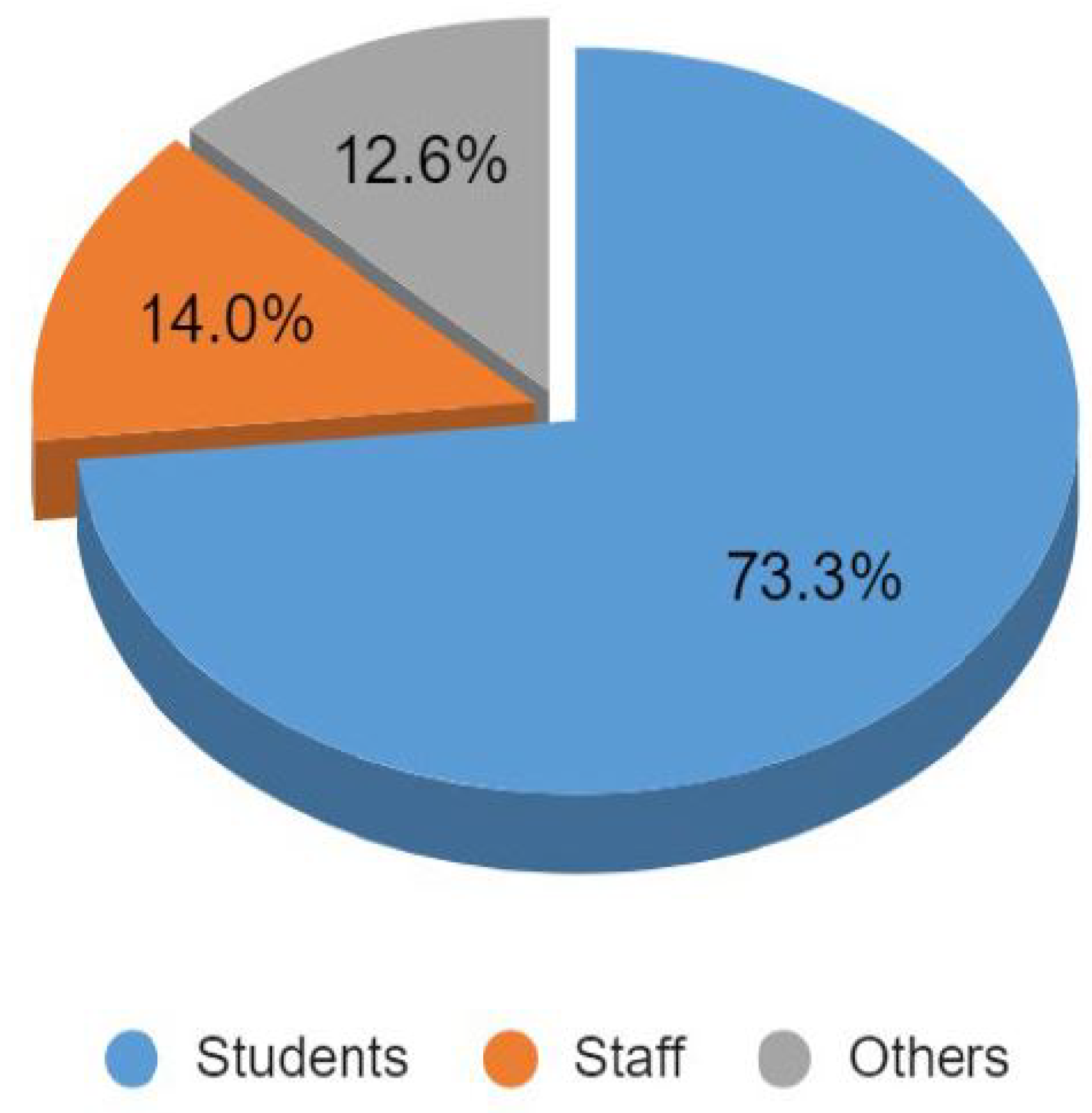

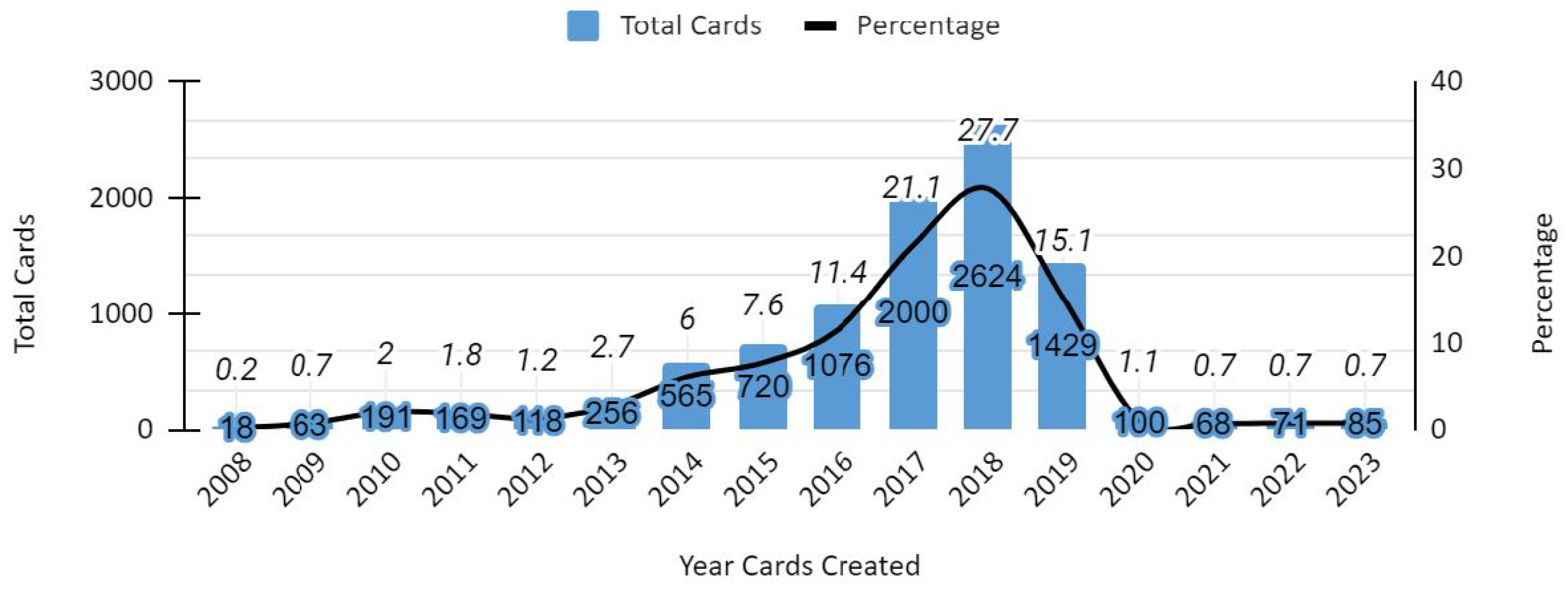

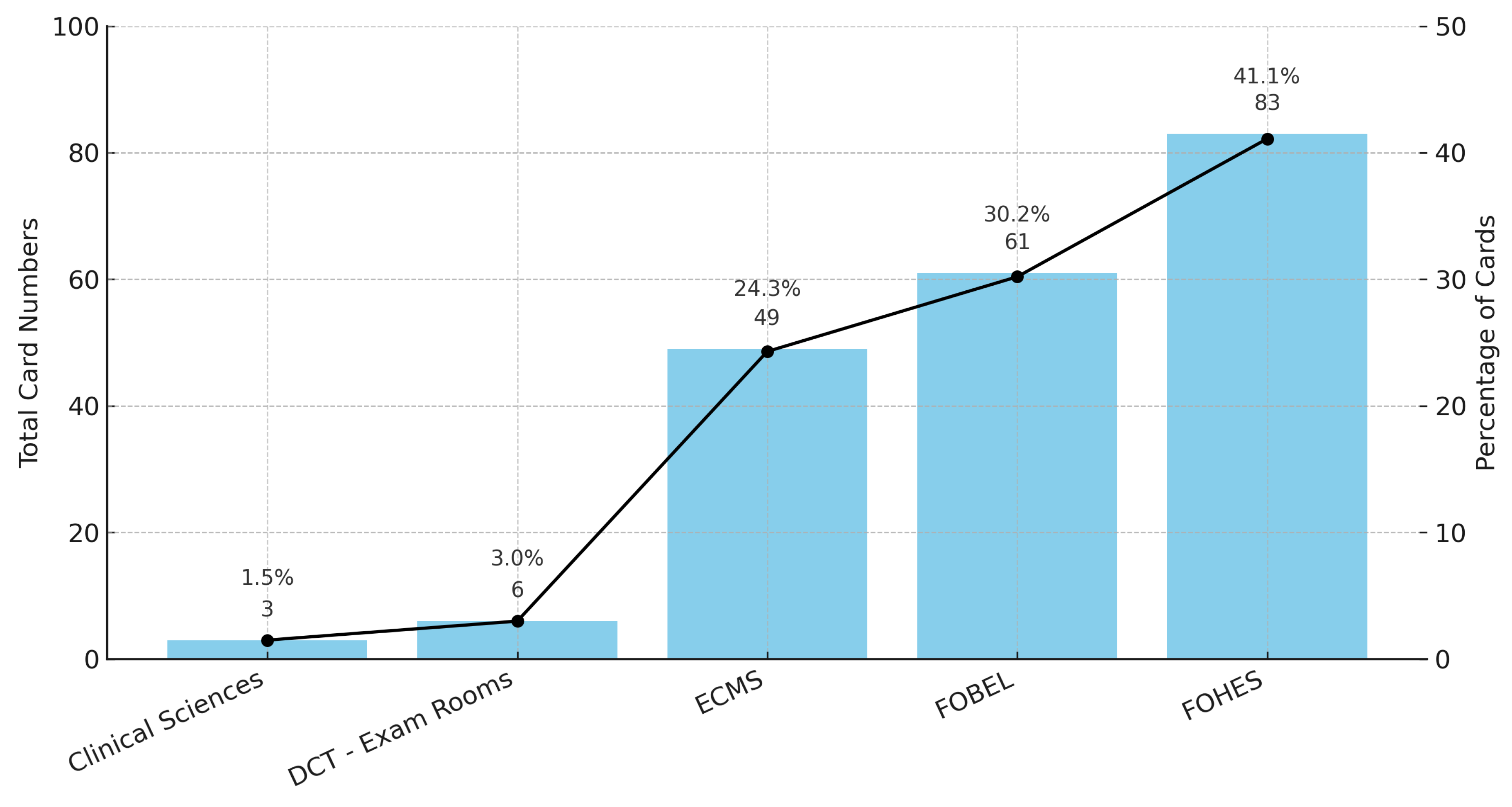

- We conducted risk analysis of the university’s existing infrastructure to map potential operational continuity threats. To this end, we analyse card issuance records, identify high-risk areas such as restricted laboratories, and evaluate the resilience of the current Gallagher–Salto system against cloning and replay attacks.

- We quantify the distribution and usage of cards that are vulnerable to Crypto1-based exploits, highlighting that more than two-fifths of active credentials remain insecure. This quantification allows us to prioritise mitigation strategies, demonstrate the scale of institutional exposure, and provide a clear evidence base for transitioning towards mobile credentials.

2. Related Work

3. Methodology and Risk Model

3.1. Mathematical Risk Model

- : the proportion of active credentials of type t issued to category i;

- : an access-privilege weight, higher for zones classified as high-risk (e.g., restricted labs);

- : a normalised activity factor, representing the relative frequency of access for category i in zone z;

- : a vulnerability factor for credential type t (e.g., , , ) to reflect the likelihood of cloning or compromise.

4. System Design and Implementation Issues

5. Results and Discussion

6. System Implications and Open Issues

6.1. Practical Implications

| Theme | Evidence / Trigger (from this study) | Operational Action / Recommendation | Expected Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legacy credential risk | High share of MIFARE Classic in circulation; exposure in restricted labs (Figure 1, Figure 3) | Prioritise migration of high-privilege users (staff, lab supervisors) first; revoke/replace Classic cards on a rolling schedule | Immediate reduction of cloning/replay risk in critical areas |

| Sustainable security | PVC card dependence; mobile credentials reduce material use (Results & Discussion) | Adopt mobile credentials as default issuance for new users; phase out plastic reprints | Security uplift with parallel progress on sustainability targets |

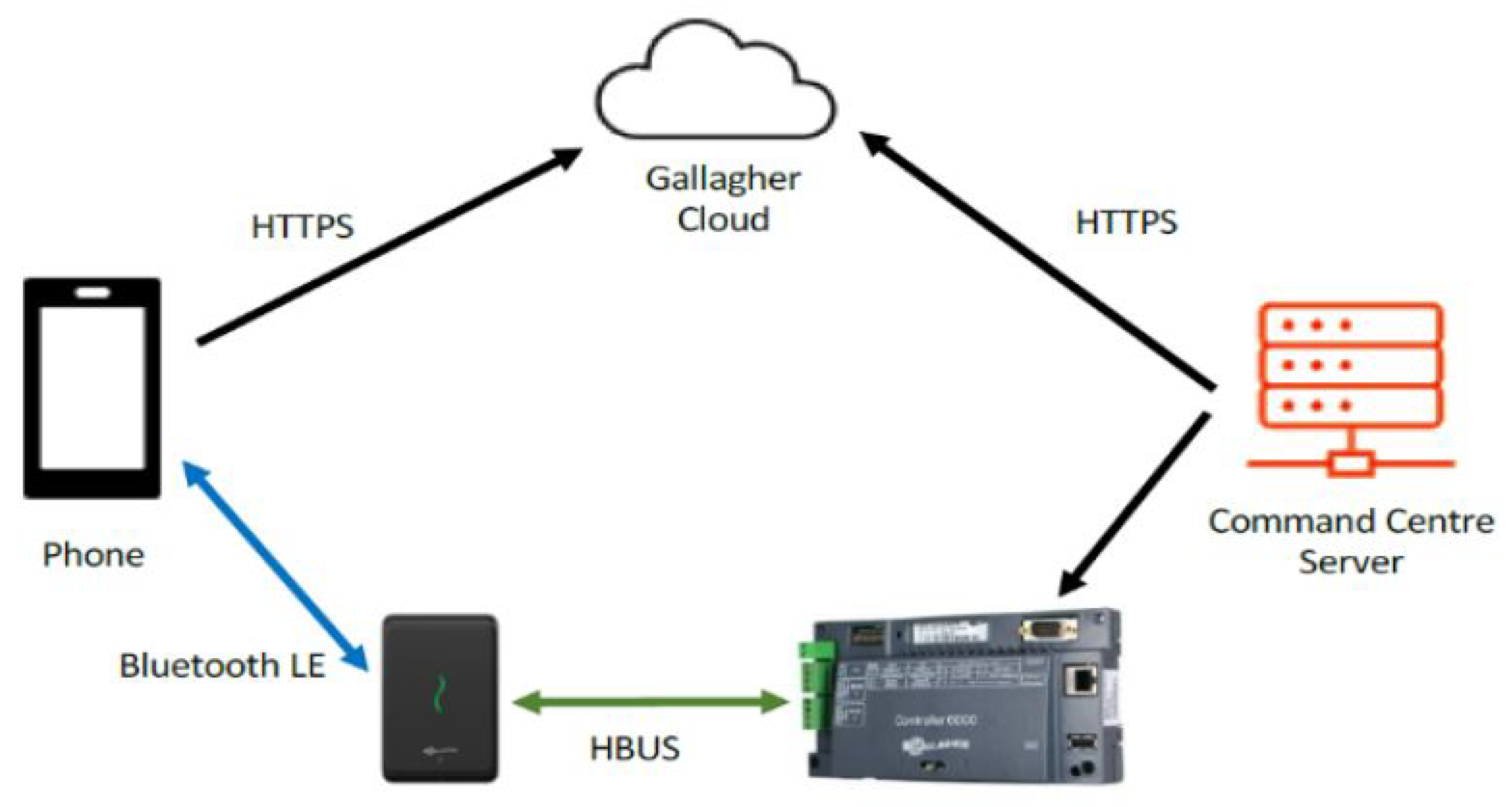

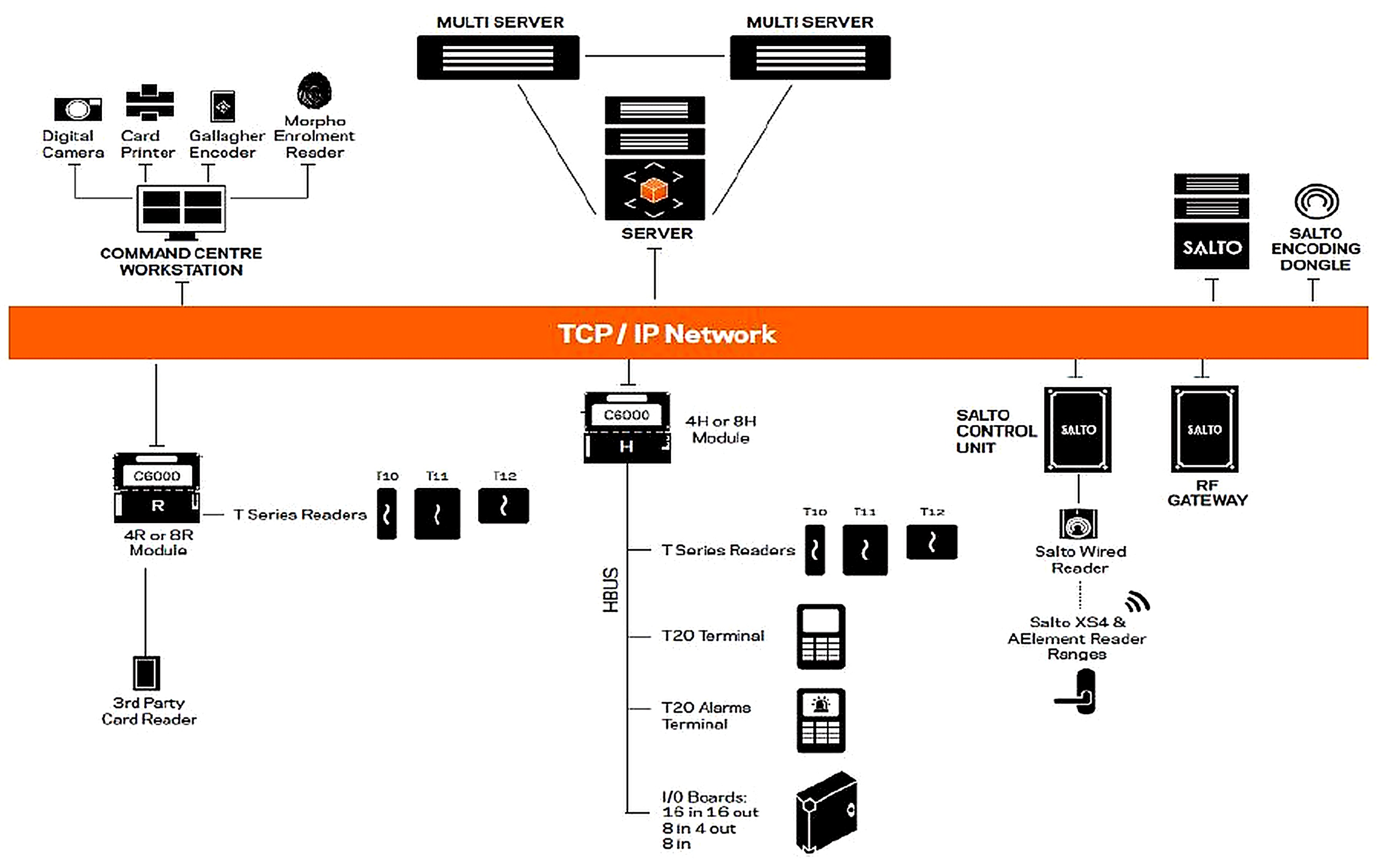

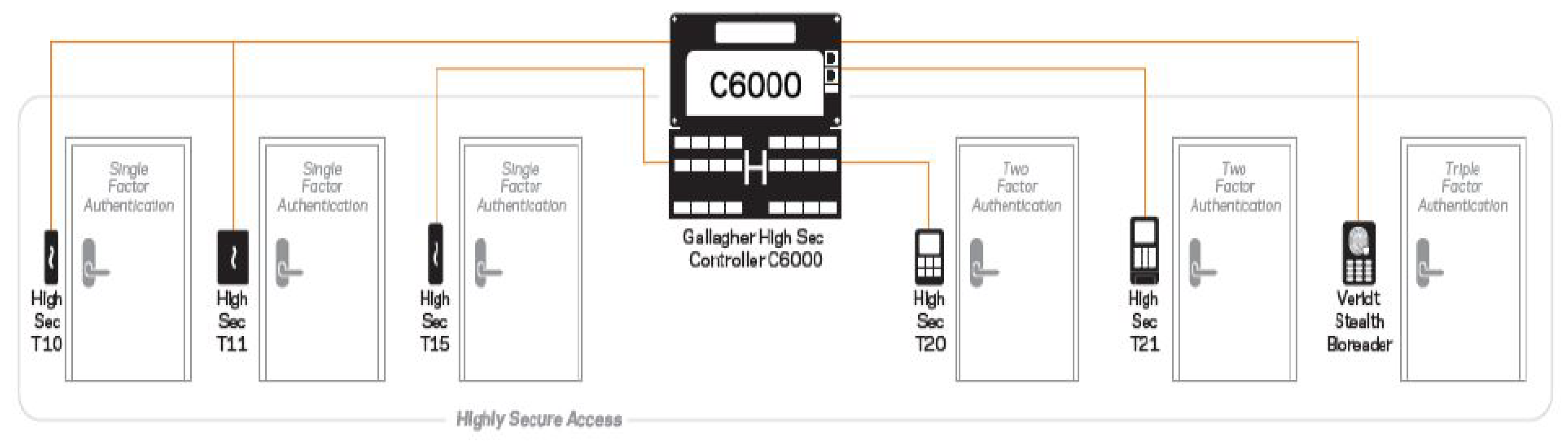

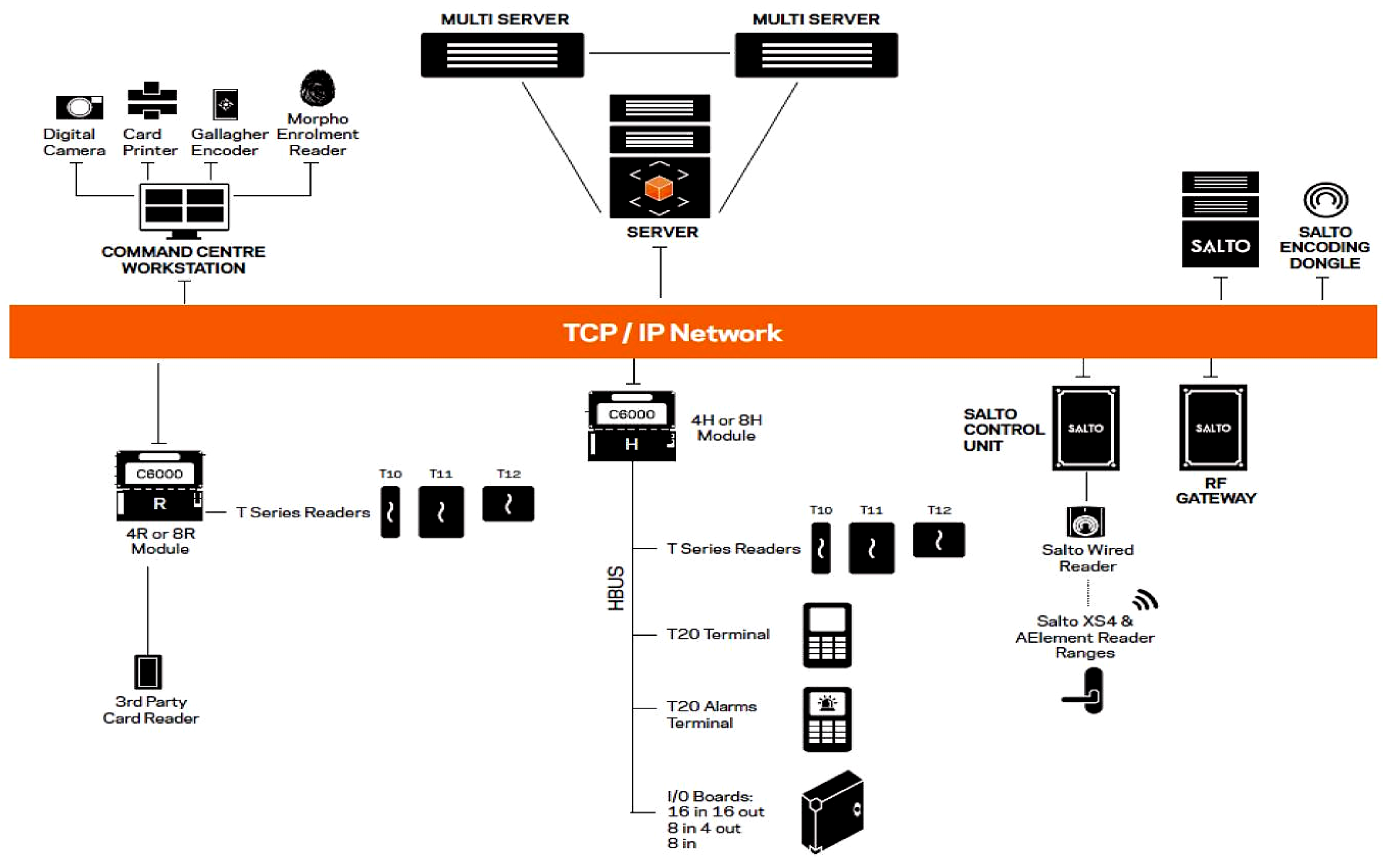

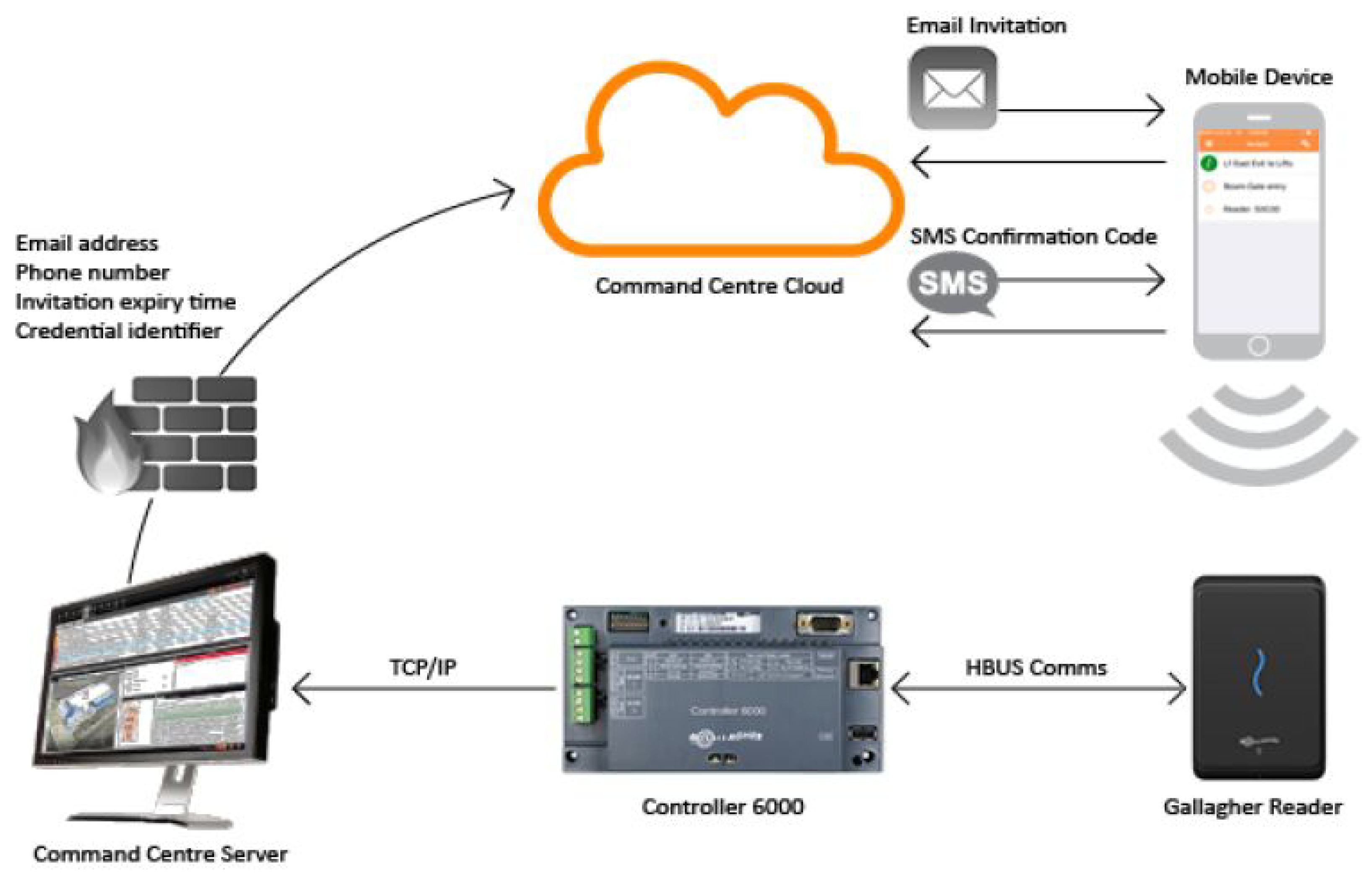

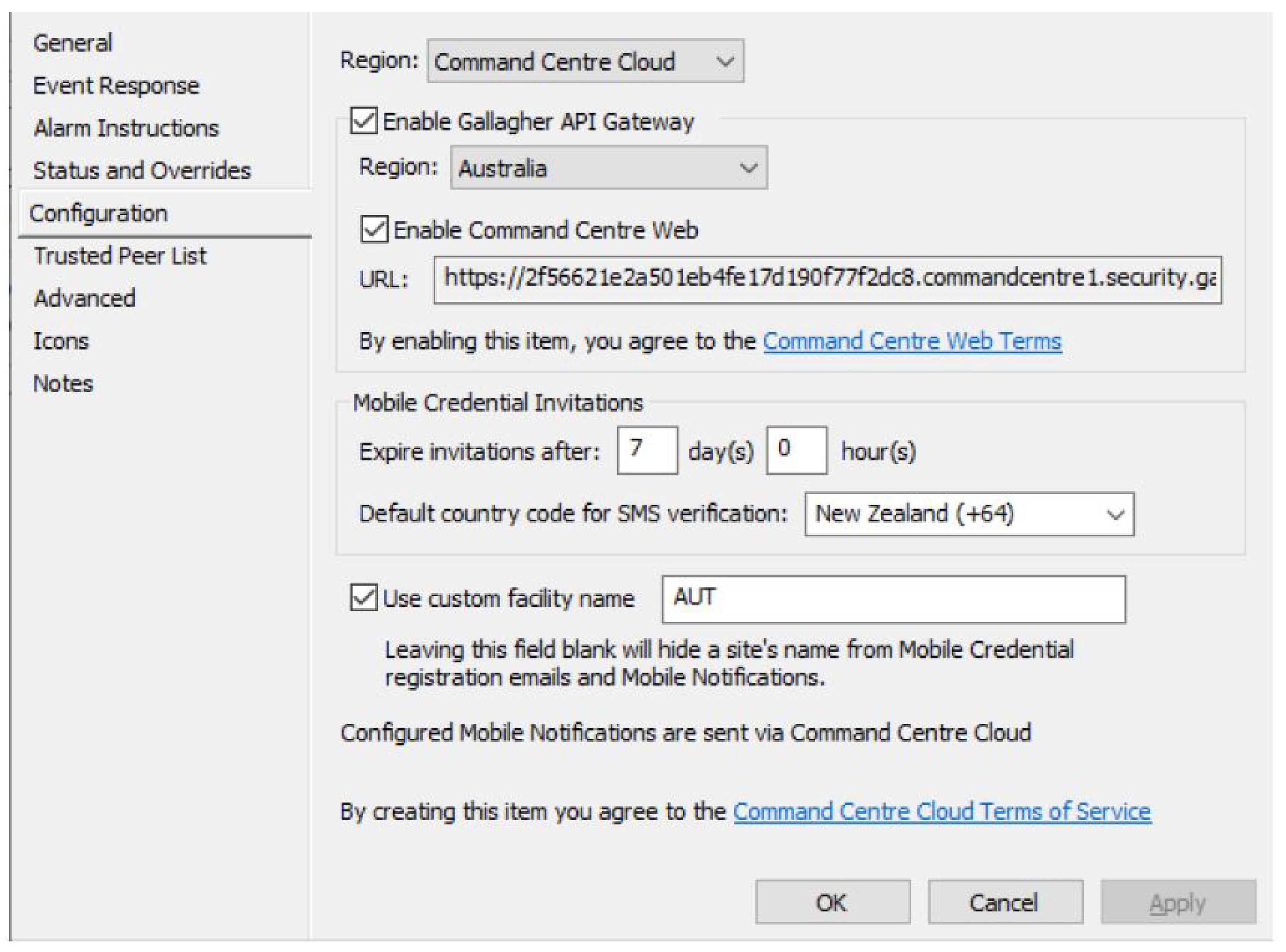

| Architecture fit | Proven Gallagher–Salto integration; Controller 6000 policy enforcement (Figure 6, Figure 7) | Keep policy logic central in Command Centre; standardise reader protocols (NFC/BLE) | Consistent enforcement and simpler operations campus-wide |

| Hardware constraints | Pilot showed gaps where legacy readers persist (Figure 13) | Tie credential migration to phased reader upgrades (replace GBUS-bound paths first) | Fewer access failures; smoother user experience |

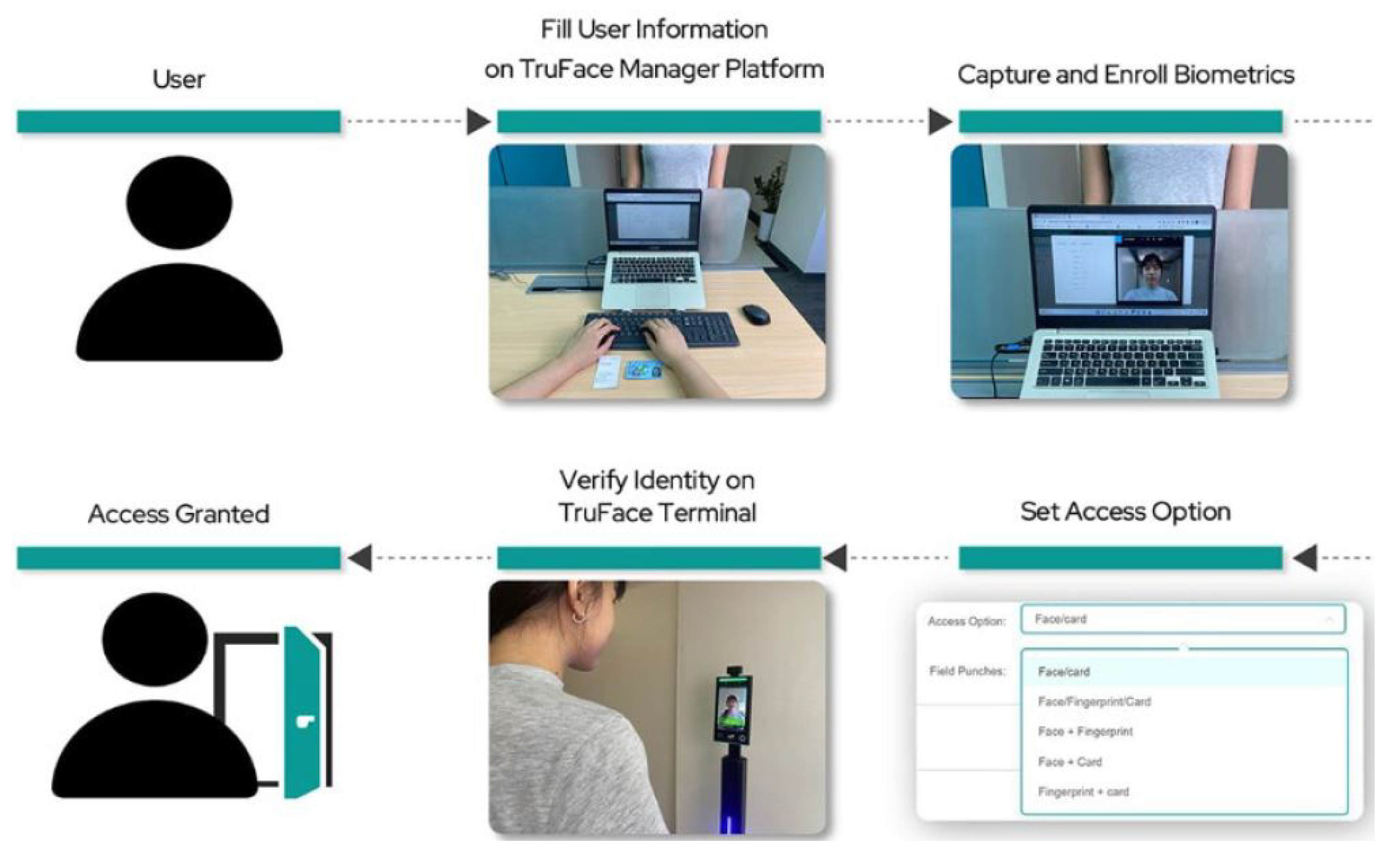

| User experience | Positive feedback on biometrics; concerns on battery reliance (pilot notes) | Enable MFA (PIN/biometric) on high-risk doors; publish device/battery good-practice | Higher acceptance with minimal friction; predictable entry reliability |

| Policy integrity | Dual issuance weakens control (Figure 14) | Enforce mutually exclusive policy: mobile or card per user, not both | Reduces sharing/abuse; clearer audit and revocation |

6.2. Open Issues and Future Directions

- Integrating mobile credentials with multi-factor authentication frameworks that adapt dynamically to risk levels (e.g., stricter checks in high-risk labs).

- Assessing the long-term reliability of mobile solutions under conditions of high user density, such as lecture theatres and examination halls.

- Expanding sustainability analysis beyond PVC cards to include the energy consumption of mobile infrastructure, ensuring that security gains do not introduce hidden environmental costs.

- Exploring how biometric authentication can be layered into the mobile ecosystem once costs and hardware barriers decrease.

| Open Issue | Research/Engineering Question | Proposed Approach / Next Step | Anticipated Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid infrastructure | How to ensure consistent UX when legacy and modern readers coexist? (cf. Figure 13) | Map “weak segments”; prioritise upgrades on critical paths; certify doors for mobile before go-live | Uniform reliability and reduced incident rates |

| Credential policy | How to enforce mobile or card without user resistance? (Figure 14) | Stage policy with grace periods; auto-revoke on acceptance of mobile; clear comms and support | Stronger governance; fewer policy exceptions |

| Cost of transition | How to finance reader/cloud upgrades at scale? | Phased CAPEX tied to risk hotspots; explore SaaS licensing; inter-faculty cost-sharing | Predictable spend; quicker risk reduction where it matters most |

| Adaptive MFA | When should authentication step-up be required? | Risk-based MFA: door sensitivity, time-of-day, anomaly score; pilot ABAC+MFA on lab doors | Higher assurance with minimal added friction |

| Peak-load performance | Will mobile scale during surges (exams/lectures)? | Load tests on busy entries; queue telemetry; BLE/NFC tuning and reader placement | Verified throughput; fewer bottlenecks at turnstiles |

| Sustainability accounting | What is the whole-of-life footprint post-migration? | Extend LCA to include reader power, cloud ops, device charging; compare to PVC baseline | Evidence-backed sustainability reporting |

| Biometrics roadmap | When do biometrics become viable campus-wide? | Targeted rollout on highest-risk doors; TCO/benefit study; privacy and consent framework | Clear path to stronger assurance with compliance |

| Incident response | How to handle lost phones and rapid revocation? | MDM hooks/self-service portal; instant credential kill-switch; audit trails | Faster containment; improved user trust |

7. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| AUT | Auckland University of Technology |

| DCT | Department of Clinical Training |

| ECMS | School of Engineering, Computer and Mathematical Sciences |

| FOBEL | Faculty of Business, Economics and Law |

| FOHES | Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences |

| HBUS | High-Speed Bus is Gallagher’s proprietary high-speed |

| RFID | Radio Frequency Identification |

| NFC | Near Field Communication |

| NFV | Network Function Virtualisation |

| ISO | International Standardization Organization |

| IEC | International Electrotechnical Commission |

| RNG | Random Number Generator |

| TCP | Transmission Control Protocol |

| SQL | Structured Querry language |

| PVC | Polyvinyl Chloride |

| REST | Representational State Transfer |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| FIDO | Fast Identity Online |

| TLS | Transport Layer Security |

| MIFARE | MIkron FARE collection system |

References

- Mustafa, R.; Sarkar, N.I.; Mohaghegh, M.; Pervez, S. A Cross-Layer Secure and Energy-Efficient Framework for the Internet of Things: A Comprehensive Survey. Sensors 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cäsar, M.; Pawelke, T.; Steffan, J.; Terhorst, G. A survey on Bluetooth Low Energy security and privacy. Computer Networks 2022, 203, 108712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onumadu, I.; Abroshan, H. Near Field Communication (NFC): Cyber Threats and Mitigation—A Systematic Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 7423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veľas, A.; Boroš, M.; Kuffa, R.; Lenko, F. Testing of Permeability of RFID Access Control System for Buildings. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestenický, P.; Hruboš, M.; Kolla, E. Evaluation of Contactless Identification Card Chip Immunity to Electromagnetic Disturbance. Electronics 2023, 12, 4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greß, H.; Krüger, B.; Tischhauser, E. The Newer, the More Secure? Standards-Compliant BLE Devices as Exemplary Targets for Security in Early 2025. Sensors 2025, 25, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peker, Y.K.; Bello, G.; Perez, A.J. On the Security of BLE in Two Different Consumer Devices. Sensors 2022, 22, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.S.U.; Ghani, A.; Daud, A.; Akbar, H.; Khan, M.F. A Review on Secure Authentication Mechanisms for Mobile Devices. Sensors 2025, 25, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudra, G.; Cui, H.; Johnstone, M.N. Survey: An Overview of Lightweight RFID Authentication Protocols Suitable for the Maritime Internet of Things. Electronics 2023, 12, 2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Li, K.; Xiao, L.; Cai, J.; Xiao, J.; Liang, W.; Liang, W.; Khan, M.K. An Adaptive, Lightweight, Secure, and Efficient RFID Fast Authentication Protocol. Sensors 2023, 23, 5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fan, Z.; Su, Y.; Zheng, B.; Liu, Z.; Dai, Y. A Lightweight, Efficient, and Physically Secure Key Agreement Scheme for IoV. Electronics 2024, 13, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Ausecha, C.; Ruiz-Rosero, J.; Ramirez-Gonzalez, G. RFID Applications and Security Review. Computation 2021, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corches, C.; Daraban, M.; Miclea, L. Availability of an RFID Object-Identification System in IoT. Sensors 2021, 21, 6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natgunanathan, I.; Fernando, N.; Loke, S.W.; Weerasuriya, C. Bluetooth Low Energy Mesh: Applications, Considerations and Current State-of-the-Art. Sensors 2023, 23, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Tian, Y. Study on Address Privacy for Bluetooth Low Energy. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wei, Z.; Yang, Z. Robust Beamfocusing for Secure Near-Field Communications with Imperfect Channel State Information. Sensors 2025, 25, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Alharbi, O.; Qasaymeh, Y.; Aljaedi, A. DC-NFC: Securing NFC with Deep Learning and Dynamic Contextual Evaluation. Sensors 2025, 25, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firlej, A.; Musial, S.; Kubiak, I. Data Immunity in Near Field RFID Communication for Universal Devices. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymoniak, S.; Kesar, S. Key Agreement and Authentication Protocols in the Internet of Things: A Review. Applied Sciences 2022, 13, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragothaman, K.M.; Wang, Y.; Rimal, B.P.; Lawrence, M. Access Control for IoT: A Survey of Existing Research, Dynamic Policies and Future Directions. Sensors 2023, 23, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namane, S.; Dhaou, I.B. Blockchain-Based Access Control Techniques for IoT Systems: A Taxonomy. Electronics 2022, 11, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukova, B.; Tengler, J.; Brumercikova, E.; Brumercik, F.; Kissova, O. Environmental Burden Case Study of RFID Technology in Logistics Centre. Sensors 2023, 23, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Cucurachi, S.; Tukker, A.; Ward, H. The Environmental Benefits and Burdens of RFID Systems in Li-Ion Battery Supply Chains—An Ex-Ante LCA Approach. Resources, Conservation & Recycling 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliakbarian, B.; Ghirlandi, S.; Rizzi, A.; Stefanini, R.; Vignali, G. Life Cycle Assessment of Plastic and Paper-Based Ultra High Frequency RFID Tags. Radio Frequency Technology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segkoulis, T.; Limniotis, K. Enhancing Multi-Factor Authentication for Mobile Devices: A Survey. Electronics 2025, 14, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wu, J.; Chen, L. A Review of RFID Applications and Security Challenges in Supply Chain Management. Computers & Security 2022, 117, 102683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Domain/Focus | Main Contribution / Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| [2] | BLE Security Survey | Maps BLE flaws and defences; foundation for secure mobile credential design. |

| [3] | NFC Threat Review | Systematic review of NFC attacks/mitigations; supports secure migration to mobile. |

| [4] | RFID System Reliability | Quantifies throughput/permeability in access control; informs door/mobile deployments. |

| [5] | Contactless Chip Immunity | Tests card chip performance under EMI; justifies replacing MIFARE Classic. |

| [6] | BLE Security Evolution | Assesses newer BLE devices; shows progress but persistent risks. |

| [7] | BLE Device Weaknesses | Empirical flaws in consumer BLE devices; relevance to PACS readers. |

| [8] | Mobile Authentication | Survey of MFA, biometrics, cryptographic methods; informs mobile credential policy. |

| [9] | Lightweight RFID Protocols | Reviews RFID auth protocols; categorises by scalability, overhead, security. |

| [10] | Fast RFID Authentication | New lightweight protocol; efficient against cloning/relay. |

| [11] | Key Agreement (IoV) | PUF+ECC protocol; shows resilience transferable to PACS. |

| [12] | RFID Applications | Broad survey of RFID uses/security; underscores legacy risks. |

| [13] | RFID Reliability | Models IoT RFID availability; relevant to continuous door operation. |

| [14] | Bluetooth Mesh | Surveys BLE Mesh uses, challenges; scalability insights for campus-wide access. |

| [15] | BLE Address Privacy | Analyzes randomization weaknesses; implications for mobile credential privacy. |

| [16] | NFC Physical Security | Robust beamfocusing to improve NFC resilience. |

| [17] | NFC + Deep Learning | Proposes DL-based DC-NFC; adaptive security for mobile apps. |

| [18] | Near-field RFID | Studies data immunity/interference; improves secure door placement. |

| [19] | IoT Protocols | Reviews auth/key-agreement; trade-offs in lightweight vs secure schemes. |

| [20] | IoT Access Control | Surveys AC models/policies; relevance to dynamic campus contexts. |

| [21] | Blockchain AC | Taxonomy of blockchain-based IoT access control. |

| [22] | RFID Sustainability | Case study of RFID in logistics; ecological trade-offs highlight plastic card waste. |

| [23] | RFID LCA | Ex-ante LCA of RFID; shows sustainability benefits and burdens. |

| [24] | UHF Tag Lifecycle | Compares paper vs plastic RFID tags; supports greener material transition. |

| [25] | Mobile MFA | Reviews contextual/biometric MFA; relevant for mobile credential security. |

| [26] | RFID in Supply Chains | Reviews RFID benefits/flaws; analogy to PACS risk vs enabler. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).