1. Introduction: The Strategic Importance of Quantum Readiness in the Cybersecurity Era

Information security in the digital age relies on the computational hardness of mathematical problems such as integer factorization and discrete logarithms, which underpin public-key cryptographic schemes like RSA and Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC). These systems have formed the foundation for secure communications, e-commerce, and digital signatures for decades. However, the rapid progress in quantum computing challenges these assumptions. Quantum algorithms—most notably Shor’s algorithm for integer factorization and discrete logarithms [

1] and Grover’s algorithm for quadratic speed-up of unstructured search [

2]—have the potential to render classical cryptographic systems obsolete.

This situation creates what is commonly referred to as the

quantum threat: a near-future scenario in which a cryptographically relevant quantum computer (CRQC) will be able to break RSA and ECC in feasible time frames. This is not only a theoretical risk but a concrete danger to national security, financial systems, and sensitive data that is being stored today. The so-called “harvest now, decrypt later (HNDL)” strategy adopted by adversaries—in which encrypted data is collected now with the intention of decrypting it later when quantum computers become available—raises the urgency of preparing for this paradigm shift [

3,

13,

14].

The concept of

quantum readiness has therefore emerged as a multidimensional framework that covers algorithmic innovation, infrastructure migration, and organizational policy adaptation. Quantum readiness is not just about developing quantum-safe algorithms, but also about evaluating current cryptographic assets, understanding risks, and defining migration roadmaps toward post-quantum cryptography (PQC) [

4]. This article aims to provide a comprehensive review of quantum readiness by addressing three critical dimensions: Academic and theoretical foundations of PQC algorithms and quantum threat models, Global standardization efforts and national strategies led by organizations such as NIST, ETSI, and the European Commission, and Sectoral implementations in critical infrastructures and the emerging concept of crypto-agility. By integrating these dimensions, this review fills a gap in the existing literature, which often focuses on either narrow technical aspects or policy considerations. The paper concludes with an analysis of open challenges, performance considerations, and future research directions that will shape the transition to a secure quantum era.

2. Methodology: Literature Search Strategy, Selection Criteria, and Review Scope

To ensure comprehensiveness and reproducibility, this review was conducted using a structured methodology consisting of three stages: literature search, selection and screening, and thematic synthesis.

The review covers research from

2018 to 2025, a period that has witnessed significant developments in PQC and quantum readiness policy-making. Searches were conducted on

IEEE Xplore, Scopus, SpringerLink, and arXiv, with additional consideration of

government and industry whitepapers from NIST [

4], ETSI [

5], the European Commission [

6], the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) [

7], and major technology vendors (IBM [

8], Microsoft [

9]). The following search terms were used individually and in combination: “post-quantum cryptography”, “quantum readiness”, “crypto-agility”, “harvest-now-decrypt-later”, and “quantum-safe transition”.

From the initial search, over 80 publications were identified. These were screened using inclusion criteria such as: Direct relevance to PQC algorithm design, standardization, or migration. Clear link to cybersecurity implications of quantum computing. Timeliness (preferably 2018 or later) and credibility (peer-reviewed or from a reputable institution). Studies were excluded if they: Focused solely on hardware implementation of quantum computers without cryptographic context, Were duplicates or outdated by more recent reports, Lacked practical or policy relevance. After filtering, approximately 40 key sources formed the core of the review.

The selected works were grouped into five thematic dimensions forming the structure of this article: Theoretical foundations—Quantum algorithms and their cryptanalytic impact, Standardization and global strategies—NIST PQC competition, EU initiatives, national roadmaps, Academic ecosystem—Algorithm development, cryptanalysis, QKD and QRNG research, Sectoral implementations and crypto-agility—Finance, telecom, and defense industry adoption, Challenges and future directions—Performance, interoperability, and human-capital issues. This structured methodology ensures that the review provides both academic rigor and practical relevance, serving as a bridge between research findings and actionable migration strategies for industry and policymakers.

3. Theoretical Foundations of the Quantum Threat: Algorithms, Complexity, and Cryptographic Implications

The central concern of quantum readiness lies in understanding the

mathematical and computational foundations of the quantum threat. Modern cryptographic systems rely on problems considered intractable for classical computers—primarily integer factorization, discrete logarithms, and elliptic curve discrete logarithms—which form the security basis of RSA, Diffie–Hellman, and ECC [

1]. The advent of large-scale quantum computers introduces a paradigm shift, as certain quantum algorithms offer exponential or quadratic speedups for these problems.

3.1. Shor’s Algorithm and Its Impact on Public-Key Cryptography

Shor’s algorithm is a

quantum polynomial-time algorithm for solving the integer factorization and discrete logarithm problems [

1]. Classical factoring algorithms like GNFS have sub-exponential complexity, but Shor’s algorithm reduces complexity to polynomial time, breaking RSA keys of practical size. Similarly, Shor’s algorithm efficiently solves ECDLP, nullifying ECC security advantages. As a result, all public-key cryptography used today—including TLS handshakes, PKI, and digital signatures—is theoretically breakable once a cryptographically relevant quantum computer exists [

2].

3.2. Grover’s Algorithm and Its Effect on Symmetric Cryptography

Grover’s algorithm provides a quadratic speed-up for brute-force search [

2]. This reduces AES-128’s effective security to 64 bits. Mitigation can be achieved with AES-256 or longer keys to restore desired security margins [

4].

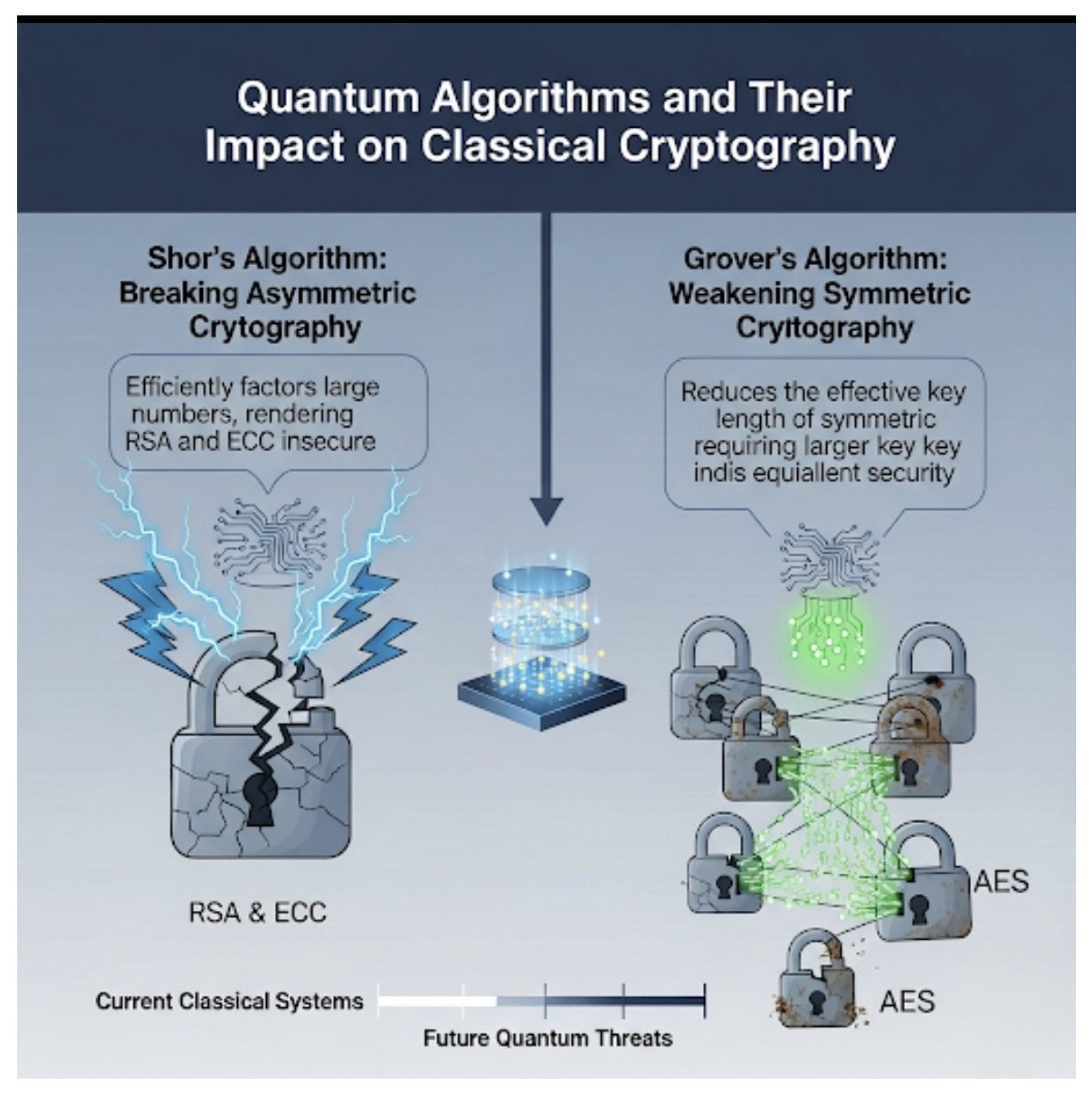

Figure 1.

A diagram showing the effect of quantum algorithms (Shor and Grover) on classical cryptographic systems.

Figure 1.

A diagram showing the effect of quantum algorithms (Shor and Grover) on classical cryptographic systems.

3.3. Harvest-Now-Decrypt-Later (HNDL) Threat Model

Adversaries may collect encrypted data now and decrypt it later when CRQCs become available [

3], creating an urgent need for proactive PQC migration to protect long-lived data such as government archives, medical records, and legal documents.

3.4. Complexity and Quantum Advantage Thresholds

Fault-tolerant quantum computers with millions of qubits are required to run Shor’s algorithm at scale. Forecasts suggest a

10–15 year Y2Q window before RSA-2048 becomes practically breakable [

7], driving governments and industry to act now [

7].

4. Global Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) Standardization Efforts and National Quantum Readiness Strategies

The mitigation of the quantum threat requires not only academic innovation but also coordinated global standardization efforts and well-defined national migration strategies. Governments, standards bodies, and industry consortia have recognized that transitioning to post-quantum cryptography (PQC) is not optional—it is a matter of national security, economic stability, and global interoperability [

4].

This section presents a comprehensive overview of international PQC standardization initiatives, with a primary focus on the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) competition, followed by European, Asian, and other national strategies that form the backbone of global quantum readiness.

Table 1.

NIST PQC Standardization Timeline.

Table 1.

NIST PQC Standardization Timeline.

| Year |

Milestone |

Outcome |

| 2016 |

Competition Launch |

Call for submissions of quantum-resistant algorithms. |

| 2019 |

Round 2 |

Security, performance, and cryptanalysis evaluations. |

| 2022 |

Round 3 Finalists Announced |

CRYSTALS-Kyber, CRYSTALS-Dilithium, Falcon, SPHINCS+. |

| 2024 |

Final Standards Published |

FIPS 203–205 released, providing first-generation PQC standards [15]. |

The selected algorithms rely on

lattice-based cryptography (Kyber, Dilithium),

hash-based signatures (SPHINCS+), and other mathematically hard problems that are believed to resist Shor’s algorithm [

4]. NIST has recommended these algorithms as mandatory for U.S. federal agencies, and industry adoption is expected to follow rapidly.

4.1. European Union Initiatives

The European Commission has identified PQC as a

strategic priority within its digital sovereignty agenda [

6]. Key initiatives include:

EuroQCI (European Quantum Communication Infrastructure): A large-scale program to build a secure quantum communication network across Europe, combining PQC and quantum key distribution (QKD).

Horizon Europe & EIC Funding: Significant investment in PQC research, algorithm development, and pilot implementations in sectors like finance and critical infrastructure. The EU’s approach is holistic, integrating

policy, research, and infrastructure development to accelerate PQC adoption.

4.2. National Strategies in Other Regions

Many countries have published roadmaps and guidance for PQC transition.

Table 2.

Comparison of National PQC Strategies.

Table 2.

Comparison of National PQC Strategies.

| Country/Region |

Strategic Focus |

Timeline |

Notes |

| United States |

NIST PQC Standardization |

2016–2024 |

Federal adoption mandatory; industry adoption ongoing |

| European Union |

EuroQCI, Horizon Europe Funding |

2020–2030 (rolling) |

PQC + QKD integrated infrastructure |

| United Kingdom |

NCSC Migration Roadmap |

2025–2035 |

Inventory by 2028, full migration by 2035 |

| Canada |

CSE PQC Guidance |

Ongoing |

Aligned with NIST standards |

| Japan |

NEDO PQC Supply Chain Projects |

2023–2026 |

Industry-focused, public-private collaboration |

| Australia |

National PQC Adoption Guidelines |

Ongoing |

Coordination with Five Eyes partners |

| China |

Independent National Standards (ICCS) |

Ongoing |

Strategic independence, domestic algorithm ecosystem |

4.3. Geopolitical and Interoperability Considerations

PQC is no longer just a cryptographic challenge—it is a

geopolitical race. The U.S.-led NIST process is expected to set global norms, but China is pursuing independent standards through the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and its own commercial cryptography standards (ICCS) [

10]. This creates a potential risk of

fragmentation, where incompatible ecosystems could emerge. Interoperability is critical for global supply chains, financial networks, and international communication systems. Therefore, collaboration through

ETSI, ISO/IEC, and ITU-T is essential to ensure that PQC adoption does not result in a balkanized internet with incompatible cryptographic stacks.

4.4. Summary and Strategic Implications

The PQC standardization and adoption process provides a roadmap for global quantum readiness. The NIST standards are expected to serve as a reference model for most countries, but national initiatives, funding programs, and industry pilots will determine the speed and success of the transition. Organizations must stay aligned with these standards to ensure long-term security, regulatory compliance, and interoperability.

5. Sectoral Implementation of Post-Quantum Cryptography and the Role of Crypto-Agility

The theoretical understanding of the quantum threat and the establishment of PQC standards must ultimately translate into real-world adoption. This adoption is particularly critical in sectors where data confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity must be preserved for long periods.

The most significant adoption efforts are currently observed in

finance, telecommunications, defense, and cloud service industries, where cryptographic transitions have direct implications for national security and economic stability [

4,

7,

16].

5.1. Financial Sector: Long-Term Confidentiality and Regulatory Pressure

Financial institutions rely on

secure key exchange, digital signatures, and transaction validation that must remain confidential for years—sometimes decades—due to compliance requirements (e.g., SOX, GDPR). The “harvest-now, decrypt-later” threat model is particularly relevant in this domain, as adversaries may collect encrypted SWIFT transactions today with the goal of decrypting them post-Y2Q [

3]. Key initiatives include:

Hybrid TLS Implementations: Google and Cloudflare have tested hybrid TLS handshakes that combine X25519 key exchange with CRYSTALS-Kyber to ensure forward secrecy even if ECC is broken in the future.

Regulatory Guidance: The U.S. Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) has begun issuing recommendations to inventory cryptographic assets and plan PQC migration by the late 2020s.

Risk-Based Prioritization: Financial firms are advised to prioritize systems that secure high-value data such as interbank settlement messages, customer authentication, and payment processing APIs.

5.2. Telecommunications: Protecting Critical Infrastructure

Telecom providers must secure massive volumes of data in motion, including 5G signaling, VoIP, and IoT device communication. Transition challenges include: Protocol Overhead: PQC algorithms often have larger keys and signatures, potentially impacting latency-sensitive services like voice calls. Network Equipment Upgrades: Legacy routers and base stations may require firmware updates or hardware replacements to support PQC libraries. Standardization Efforts: The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) has initiated working groups for PQC-enabled TLS and VPN standards, ensuring that telecom providers can gradually upgrade without breaking compatibility.

5.3. Defense and National Security Systems

Defense systems face the highest stakes. Military communications, satellite links, and classified archives must remain secure for decades. Crypto-Modernization Programs: The U.S. Department of Defense has initiated programs such as Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0 (CNSA 2.0) that mandate migration to PQC algorithms once NIST standards are finalized. Air-Gapped Systems: Some classified networks cannot be upgraded quickly; crypto-agility mechanisms allow algorithm replacement with minimal re-engineering.

Figure 2.

A diagram illustrating how crypto-agility works, showing how systems can rapidly switch cryptographic algorithms.

Figure 2.

A diagram illustrating how crypto-agility works, showing how systems can rapidly switch cryptographic algorithms.

5.4. Cloud Service Providers and Software Vendors

Major cloud vendors (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud) are piloting PQC-enabled

Key Management Systems (KMS) and

VPN gateways.

IBM Quantum Safe: IBM has introduced PQC-hardened cloud services allowing clients to test lattice-based key exchange mechanisms [

8].

Developer Tooling: OpenSSL and BoringSSL are already integrating PQC primitives in experimental branches, helping developers prepare for hybrid and fully quantum-safe protocols.

5.5. The Concept of Crypto-Agility

Crypto-agility refers to the ability of an organization’s infrastructure to

rapidly switch cryptographic algorithms without requiring a major architectural redesign [

5]. This involves

Modular Design: systems must decouple cryptographic primitives from application logic, using abstraction layers or standardized APIs.

Hybrid Deployment: In transitional phases, hybrid schemes (e.g., ECDH + Kyber) offer compatibility and risk reduction.

Future-Proofing: Crypto-agility not only helps with PQC transition but also protects against future vulnerabilities (e.g., algorithm breaks, side-channel discoveries).

5.6. Challenges in Sectoral Adoption

Despite early progress, several adoption barriers remain:

Legacy System Complexity: Industrial control systems and embedded IoT devices may lack firmware update mechanisms.

Cost and Resource Constraints: Upgrading hardware security modules (HSMs) and key management systems can be expensive.

Performance Overheads: Larger PQC keys can stress bandwidth-limited environments (e.g., satellite communications) [

14].

Vendor Coordination: Multi-vendor ecosystems require coordinated upgrades to avoid protocol mismatches.

5.7. Summary

Sectoral implementation is a multidimensional effort, requiring technical, operational, and policy coordination. The successful adoption of PQC will depend on early inventory management, staged migration strategies, and the integration of crypto-agility principles across system design and procurement processes. The lessons learned from finance, telecom, defense, and cloud computing sectors will likely set the blueprint for other industries as the world approaches the Y2Q horizon.

6. Academic Research Ecosystem: Foundations, Collaborations, and the Role of Cryptanalysis

Academic research serves as the backbone of progress in

post-quantum cryptography (PQC) and quantum readiness. While standardization efforts like the NIST PQC project provide a formal process for algorithm selection,

academia is where the majority of novel algorithm design, security proofs, and cryptanalytic evaluations originate [

4]. The dynamic and open nature of academic research enables continuous peer review, public scrutiny, and the discovery of potential weaknesses before large-scale deployment.

6.1. Algorithm Development and Theoretical Foundations

Universities and research centers worldwide have been instrumental in developing the lattice-based, code-based, multivariate, and hash-based cryptographic schemes that now form the basis of PQC standards. For instance: Lattice-based Cryptography: Research teams at institutions like University of Waterloo and ENS Lyon have advanced Learning with Errors (LWE) and Module-LWE based constructions, which underpin CRYSTALS-Kyber and Dilithium. Code-based Cryptography: The McEliece cryptosystem and its variants have been refined by researchers at Ruhr University Bochum and TU Eindhoven, ensuring they remain competitive despite large key sizes. Multivariate Schemes: KU Leuven and Chinese Academy of Sciences researchers have explored multivariate polynomial cryptography, although several candidates were eliminated during NIST Round 3 due to cryptanalysis. Hash-Based Signatures: SPHINCS+ is a direct product of academic collaboration, offering stateless hash-based signatures with well-understood security guarantees.

6.2. Cryptanalysis and Security Evaluation

Equally important to algorithm design is cryptanalysis—the rigorous process of stress-testing proposed schemes against known and novel attack vectors. This includes: Classical Attacks: Differential and linear algebra-based techniques are used to test the hardness assumptions of candidate schemes. Quantum Attacks: Researchers explore how quantum algorithms beyond Shor’s and Grover’s (e.g., quantum sieving, amplitude amplification) might weaken security margins. Side-Channel Analysis: Teams at KU Leuven’s COSIC group and Radboud University have demonstrated power analysis and timing attacks on lattice-based schemes, prompting mitigations in final NIST candidates. This iterative process ensures that by the time an algorithm is standardized, it has survived extensive real-world and theoretical scrutiny.

6.3. Collaboration Between Academia, Industry, and Government

Many PQC candidates were the result of joint efforts between academic researchers and industrial cryptographers. For example: CRYSTALS-Kyber/Dilithium: Developed collaboratively by a team including researchers from Radboud University, Ruhr University Bochum, and Google’s security teams. Falcon: Co-developed by academics from ENS and IBM Research. Government agencies (NIST, NSA) and standards bodies (ETSI, ISO) rely heavily on open workshops, conferences (PQCrypto, CHES), and academic publications to guide their evaluation processes.

6.4. Education and Workforce Development

Academic programs are also central to training the next generation of cryptographers. Post-quantum cryptography is now featured in graduate curricula at MIT, ETH Zurich, and University of Waterloo, ensuring a skilled workforce to implement and maintain PQC solutions. Several universities have launched dedicated quantum-safe security labs that allow students to work on experimental PQC deployment and hybrid protocol testing.

6.5. International Research Initiatives

Significant funding programs have been launched globally to sustain PQC research: European Quantum Flagship and Celtic-Next projects support academic–industrial consortia across Europe. US NSF and DARPA programs provide grants for fundamental research on lattice problems, quantum-resistant protocols, and hardware acceleration. Japan’s NEDO and AIST programs focus on integrating PQC into the national supply chain with strong academic participation.

6.6. Summary

The academic research ecosystem not only produces algorithms but also serves as the critical testing ground for their reliability and efficiency. The process of peer-reviewed publication, open cryptanalysis, and collaborative development ensures that the algorithms chosen for standardization are trustworthy and robust. This symbiosis between academia, industry, and government will remain essential as the field moves from first-generation PQC standards to second-generation, post-deployment optimizations.

7. Discussion and Open Challenges: Bridging the Gap Between Theory and Deployment

Although significant progress has been made in understanding the quantum threat, designing post-quantum cryptographic schemes, and initiating standardization efforts, the path to global PQC deployment is fraught with challenges. These challenges are both technical and organizational, requiring collaboration among governments, academia, and industry.

This section discusses the key open problems that must be addressed to achieve a smooth and secure transition.

7.1. Performance Overheads and Efficiency Trade-Offs

One of the most cited concerns in PQC deployment is the

larger key sizes and signatures compared to classical cryptography.

Lattice-based KEMs (Kyber): Public keys and ciphertexts are an order of magnitude larger than RSA or ECC, potentially increasing handshake times in high-latency networks [

4].

Signature Schemes (Dilithium, Falcon): While Dilithium provides strong security, its signature size is significantly larger than ECDSA. Falcon offers more compact signatures but is computationally more expensive and harder to implement securely [

11].

These overheads could impact: TLS Handshakes: Increasing initial handshake size can slow web page loads and APIs. IoT & Constrained Devices: Memory-limited microcontrollers may not be able to store PQC key material without firmware changes. High-Throughput Systems: VPN gateways, CDN edge servers, and cloud load balancers may need hardware acceleration to handle the extra cryptographic workload. Mitigation strategies include hybrid key exchange (using both ECC and Kyber), parameter tuning for performance/security balance, and the development of hardware accelerators (FPGAs, PQC-ready HSMs).

7.2. Legacy System Migration and IoT Challenges

The migration of legacy systems is one of the most expensive and complex aspects of quantum readiness:

Industrial Control Systems (ICS): Many ICS and SCADA devices have life cycles of 20+ years and may not be upgradeable [

17].

IoT Devices: Billions of IoT devices lack sufficient processing power to run PQC algorithms efficiently.

Firmware Constraints: Some devices cannot receive over-the-air updates, requiring physical replacement to achieve compliance [

7]. The concept of

crypto-agility [

5] becomes critical: designing updateable cryptographic modules now will reduce the cost of future migrations.

7.3. Interoperability and Standards Fragmentation

There is a risk that

multiple PQC standards may emerge, driven by geopolitical motivations.

US/EU vs. China: NIST standards are likely to dominate in Western markets, whereas China is pursuing its own domestic cryptographic standards (ICCS) [

10].

Risk of Protocol Incompatibility: This could fragment global communication systems, creating trade barriers or interoperability failures. International bodies such as

ISO/IEC, ETSI, and ITU-T must accelerate consensus-building to avoid a “cryptographic splinternet”.

7.4. Side-Channel Security and Implementation Risks

While PQC schemes are mathematically secure, they are not immune to

implementation-level attacks:

Timing Attacks: Non-constant-time implementations of lattice-based schemes can leak secret information [

11].

Power/EM Analysis: Research has shown that certain Kyber implementations can be broken using differential power analysis (DPA) if countermeasures are not applied. Secure implementations must use constant-time operations, masking techniques, and robust testing under side-channel attack scenarios before deployment.

7.5. Human Capital and Skills Shortage

There is a significant shortage of

cryptographers and security engineers trained in PQC:

Curriculum Gaps: Many universities are just beginning to integrate PQC topics into computer science and cybersecurity programs [

12,

14].

Operational Expertise: Enterprises need specialists who can inventory cryptographic assets, assess Y2Q risks, and design migration strategies.

Global Disparity: Some countries risk falling behind due to lack of skilled workforce, exacerbating cybersecurity inequality. Investments in

training, certification programs, and open-source PQC libraries are necessary to close the skills gap.

7.6. Governance and Compliance Uncertainty

Regulatory clarity is still evolving:

Compliance Deadlines: While NIST standards are finalized, no global timeline mandates their adoption [

16].

Sector-Specific Rules: Financial, healthcare, and defense industries may adopt PQC at different paces, creating complexity for multinational organizations [

7]. A coordinated governance approach—potentially via international treaties or cybersecurity frameworks—will be necessary to harmonize adoption schedules.

7.7. Synthesis and Outlook

The challenges outlined above represent not barriers, but roadmaps: they indicate where research, funding, and policy must focus. The next decade will require: Efficient and hardware-optimized PQC implementations, Large-scale pilot deployments in critical sectors, Development of interoperable standards, Global workforce development efforts. If addressed systematically, these steps will ensure a secure and seamless transition into the post-quantum era.

8. Future Directions: Roadmap for a Secure Post-Quantum Era

The transition to post-quantum cryptography (PQC) is not a one-time event but a long-term, multi-phase process that will continue to evolve as quantum computing technology advances. While first-generation standards have been published, research and deployment efforts must remain adaptive and forward-looking. This section highlights the most promising future directions and research priorities.

8.1. Optimization of PQC Algorithms and Implementations

Although NIST’s first-generation PQC standards provide a baseline, further work is needed to optimize performance:

Hardware Acceleration: Development of PQC-specific instruction sets (e.g., PQC extensions to RISC-V or ARM) and integration into Hardware Security Modules (HSMs) can reduce latency.

Parameter Tuning: Research is ongoing to balance key size, security level, and performance for resource-constrained environments (IoT, automotive ECUs).

Side-Channel Resistance: Future algorithm implementations must be hardened by design against timing, power, and fault-injection attacks [

11].

8.2. Second-Generation Standards and Algorithm Diversity

While the first round of NIST PQC standards focused primarily on lattice-based cryptography,

algorithmic diversity remains important to hedge against unforeseen breakthroughs.

Code-Based and Multivariate Schemes: Continued exploration of McEliece variants and multivariate signature schemes ensures fallback options.

Hybrid Models: Future standards may formalize hybrid cryptography (PQC + classical) to smooth migration and enable incremental adoption.

Algorithm Lifecycle Management: Research into automated deprecation mechanisms for cryptographic algorithms will support crypto-agility [

5].

8.3. Integration with Quantum Communication Technologies

Post-quantum cryptography is one part of a larger ecosystem that includes

Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) and

Quantum Random Number Generation (QRNG).

Complementary Use: PQC provides mathematical security, while QKD offers information-theoretic security for key exchange. Future systems may combine both approaches for high-assurance environments [

12].

Network Integration: Research into QKD integration with 5G/6G networks and software-defined networking (SDN) will create flexible hybrid infrastructures.

8.4. Global Governance and Policy Development

The next decade will require

international cooperation to prevent fragmentation and ensure interoperability:

ISO/IEC and ETSI Alignment: Efforts must continue to harmonize standards and certification frameworks across jurisdictions [

6].

Compliance Timelines: Clear global adoption roadmaps can prevent “last-minute” migrations that create operational risk.

Export Control and Cyber Diplomacy: As PQC becomes part of critical infrastructure, export policies and cyber treaties must address equitable access and prevent misuse.

8.5. Workforce Development and Education

To meet global demand for PQC deployment:

Curriculum Modernization: Universities should expand cryptography courses to include PQC theory, implementations, and migration planning [

12].

Professional Training: Industry certifications (e.g., PQC Security Engineer) can help upskill the existing cybersecurity workforce.

Open-Source Ecosystem: Investment in open-source PQC libraries will lower the barrier to adoption and support security audits.

8.6. Preparing for the Unexpected: Post-Standardization Vigilance

Even after migration, organizations must remain alert:

Cryptanalytic Breakthroughs: Continuous monitoring of academic research is essential in case a new quantum algorithm weakens current PQC standards.

Quantum Computing Advances: If large-scale quantum computers arrive earlier than expected, migration timelines must be accelerated.

Resilience-by-Design: Systems should incorporate crypto-agility so that future algorithm swaps can be made with minimal operational disruption [

5].

8.7. Vision for the Quantum-Resilient Future

Ultimately, the goal is a quantum-resilient digital ecosystem where cryptographic systems can withstand quantum and classical attacks for decades. This vision requires: Strong collaboration between academia, industry, and governments, Sustained funding for fundamental cryptographic research, Ongoing international standardization efforts, A culture of proactive risk management in cybersecurity. The successful execution of these future directions will define the security, privacy, and trustworthiness of the next generation internet.

9. Conclusions

The advent of quantum computing represents a paradigm shift for modern cybersecurity. This review has shown that

the quantum threat is no longer a distant theoretical concept, but a tangible and time-sensitive challenge that demands coordinated global action. Across

Section 1–8, we have examined: The

theoretical underpinnings of the quantum threat, highlighting the impact of Shor’s and Grover’s algorithms on public-key and symmetric cryptography [

1,

2].

The

standardization process, led by NIST and complemented by initiatives from ETSI, the European Commission, and other national agencies, which has produced the first generation of post-quantum standards [

4,

6,

15]. The

sector-specific adoption strategies in finance, telecommunications, defense, and cloud computing, emphasizing the importance of crypto-agility and staged migration [

5,

7,

8]. The

academic research ecosystem, which continues to deliver new algorithms, perform cryptanalysis, and train the next generation of security professionals [

11,

12]. The

open challenges and future directions, ranging from performance optimization to global interoperability and workforce development.

The findings underscore that

quantum readiness is not merely a technical upgrade but a strategic imperative with national security, economic, and geopolitical dimensions. Organizations must start

cryptographic asset inventories, prioritize systems with long-term confidentiality requirements, and adopt

hybrid solutions where possible to mitigate “harvest-now-decrypt-later” risks [

3].

Looking ahead, the journey to a quantum-secure future will require: Continuous monitoring of cryptanalytic advances and updating standards accordingly. Global collaboration to prevent standards fragmentation and ensure interoperability. Sustained investment in education, tooling, and workforce development to meet implementation demands. By following these principles, the transition to a quantum-resilient digital ecosystem can be achieved in a timely and coordinated manner, ensuring that the confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity of digital communications remain intact well into the quantum era.

References

- P. W. Shor, “Algorithms for Quantum Computation: Discrete Logarithms and Factoring,” in Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 1994.

- L. K. Grover, “A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search,” in Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, 1996.

- PwC, “Preparing for the Quantum Computing Era,” 2021.

- NIST, “Report on Post-Quantum Cryptography,” NISTIR 8105, 2016.

- ETSI, “Quantum-Safe Cryptography: An ETSI White Paper,” 2019.

- European Commission, “The European Quantum Flagship,” 2020.

- NCSC, “Timelines for Migration to Post-Quantum Cryptography,” 2025.

- IBM, “IBM Quantum Safe,” 2023.

- Microsoft, “Quantum Computing and Cybersecurity,” 2023.

- Merics, “China’s Long View on Quantum Tech Has the US and EU Playing Catch-Up,” 2024.

- M. Albrecht et al., “Concrete Security for Lattice-Based Cryptography,” Cryptology ePrint Archive: Report 2016/504, 2016.

- N. Gisin et al., “Quantum Cryptography,” Rev. Mod. Phys., vol. 74, no. 1, pp. 145–195, 2002.

- Computing Research Association, “The Post-Quantum Cryptography Transition: Making Progress, But Still a Long Road Ahead,” 2025.

- C. Beder, “Post-Quantum Cryptography: A Call to Action,” ISACA, 2025.

- NIST, “Status Report on the Fourth Round of the NIST Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization Process,” NISTIR 8545, 2024.

- I. Kong, M. Janssen, & N. Bharosa, “Challenges in the Transition towards a Quantum-safe Government,” in Proceedings of the 23rd Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, 2022.

- M. S. Siddiqui, A. G. G. Ahmad, & M. S. R. Khan, “Post Quantum Cryptography: A Comprehensive Review of Migration Challenges & Strategies,” International Journal of Novel Research and Development, 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).