Submitted:

19 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Principles and Applications of Spectroscopic Techniques

2.1. SERS Techniques

2.1.1. Principles

2.1.2. SERS Substrates and Signal Enhancement Strategies

2.1.3. Research Progress of SERS in Pesticide Detection

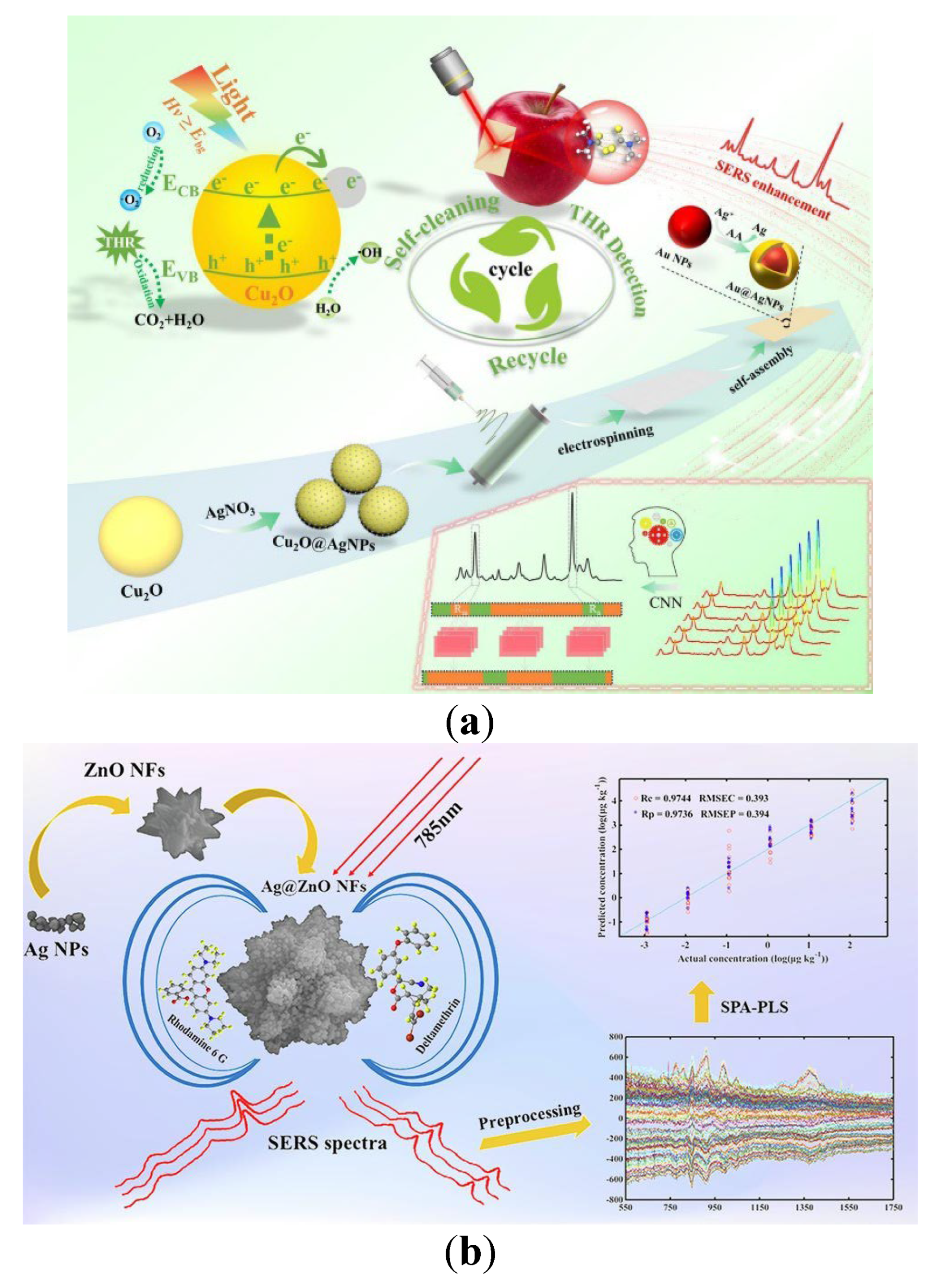

SERS Technology in Pesticide Residue Detection in Fruits and Vegetables

Pesticide Detection in Grains and Oil Crops

Application of Chemometrics Combined with SERS Technology in Pesticide Detection

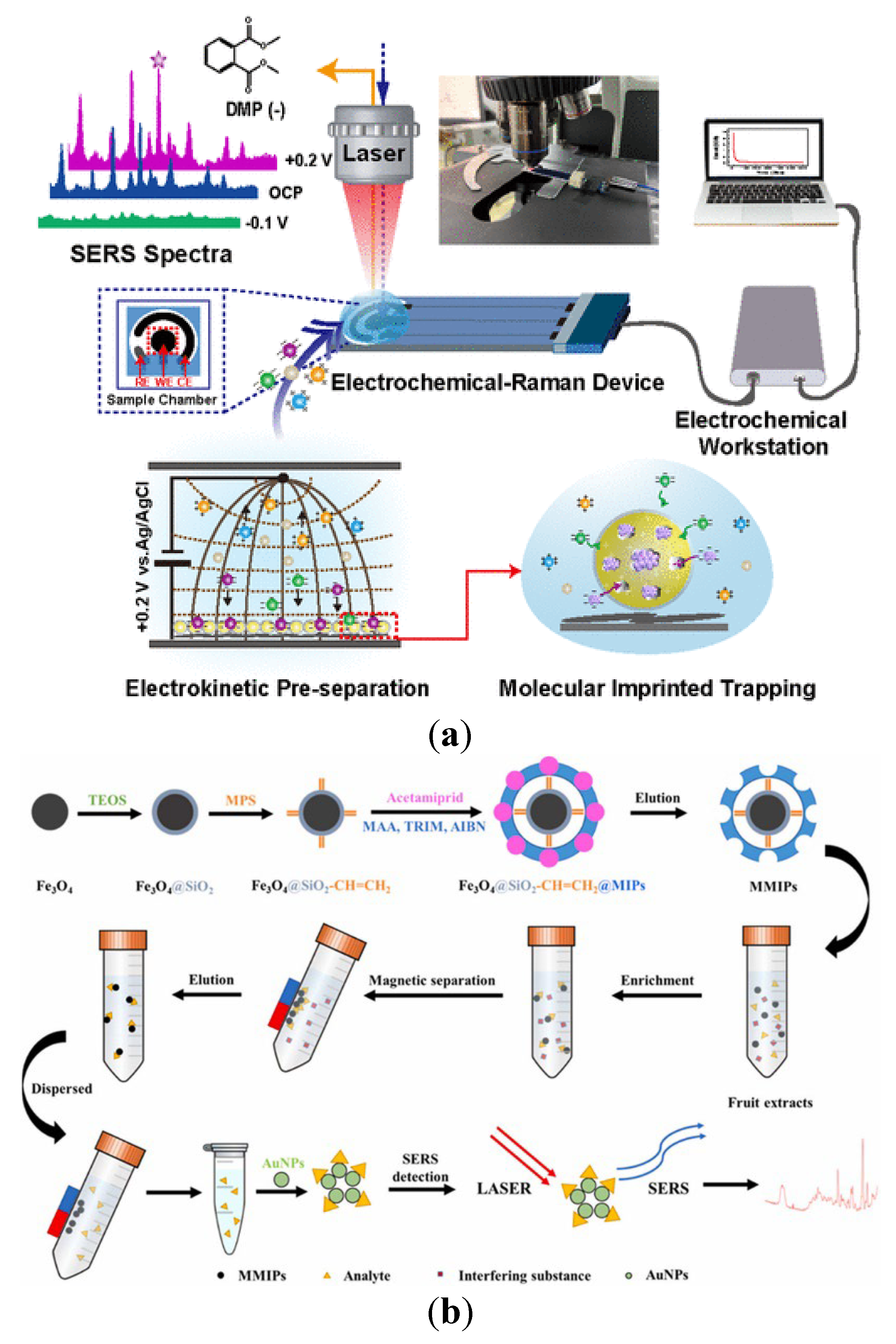

Application of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) with SERS Technology in Pes-ticide Detection

2.1.4 Comparison of Various SERS Detection Methods

| Detection Scheme | Data Analysis Methods | Pesticides | Recovery Rate (%) | RSD (%) | LOD | Detection Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERS | Portable Raman spectrometer (785 nm) | Thiram | -- | 2.29 | 1 ppm | 5–10 min | [54] |

| SERS | Portable Raman spectrometer | Melamine; Thiram | Melamine in milk: 95.9;Thiram in apple juice: 94.8 | Melamine:3.53;Thiram: 4.49 | Melamine: 7.38 μg/L;Thiram: 86.1 μg/L | <10 min | [56] |

| SERS with stoichiometry | - | TBZ | Good recycling performance | < 10 | 0.1 mg/kg | <10 min | [57] |

| SERS | Portable Raman spectrometer | Acetamiprid; Thiram | Acetamiprid: 90.2–122.12 (apple juice), 89.86–117.23 (orange juice); Thiram: 90.38–113.42(apple juice), 91.46–108.72 (orange juice) | Acetamiprid, Thiram | Acetamiprid: 0.272 mg/L(apple juice), 0.47 mg/L(orange juice); Thiram: 0.018 mg/L(apple juice),0.025 mg/L(orange juice) | - | [58] |

| SERS with stoichiometry | SPA-PLS | Deltamethrin | 96.33–109.17 | < 5 | 0.16 μg·kg⁻¹ | - | [61] |

| SERS | Portable Raman spectrometer | Acetamiprid (ACE); Cypermethrin (CBZ) | ACE: 93.86–105.64; CBZ: 92.62–102.3 |

- | ACE: 0.27 μg/kg;CBZ: 1.71 μg/kg | - | [67] |

| SERS with stoichiometry | - | Thiram | 88.32–111.80 | 2.92–4.91 | 0.020 mg/L | - | [68] |

| SERS | - | Methyl-parathion (MP); Thiram(TMTD), Chlorpyrifos (CPF) | MP: 81.77–118.67; TMTD: 64.68–117.20; CPF: 73.10–126.80 |

8.58 (1078 cm⁻¹), 9.29 (1583 cm⁻¹) | MP: 0.072 ng/cm²;TMTD: 0.052 ng/cm²;CPF: 0.059 ng/cm² | - | [70] |

| SERS | Confocal Laser Scanning Raman Microscope System (InVia Reflex, Renishaw, UK) |

Carbaryl | 82–99.8 | - | - | - | [71] |

| SERS | Confocal Laser Scanning Raman Microscope System (Renishaw, UK) | Thiabendazole (TBZ) | 95–101 | - | TBZ: 0.032 ppm (Apple juice), 0.034 ppm (Peach juice) | <30 min | [72] |

| SERS with stoichiometry | Pymetrozine; Thiram | - | <8% | 0.0001 μg/mL | - | [74] | |

| SERS with stoichiometry | GC-MS | Chlorpyrifos (CPS) | - | - | - | - | [76] |

| SERS with Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) Model | Thiram; Pymetrozine | Thiram: 83.06–92.6; Pymetrozine: 95.32–110.38 | Thiram:6.43; Pymetrozine:10.41% | Thiram:0.286 ppb; Pymetrozine:29 ppb | - | [77] | |

| SERS with Molecular Imprinting Technology (MIPs) | - | Pentachloronitrobenzene (PCNB) | 94.4–103.3 | 4.6–7.4 | 0.005 µg/mL | - | [82] |

| SERS with MIPs | Portable Raman spectrometer (RT5000, 785 nm) | Simazine; Prometryn | Simazine: 72.7–90.9; Prometryn: 79.1–86.5 | Simazine:1.7–7.6; Prometryn: 2.3–7.8 | 0.05 μg·mL⁻¹ | - | [83] |

| SERS | SPLD-RAMAN spectrometer (785 nm) | 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) | 93.5–102.2 | - | 0.00147 ng/mL | 2 h | [84] |

| SERS | Portable Raman spectrometer (785 nm) | Acetamiprid; Thiacloprid | Acetamiprid: 85.1–107.6(pear), 86.1–98.2(Peach);Thiacloprid: 90.1–105.6(pear),73.5–112.8(Peach) | 7.5 | Acetamiprid: 68.8 ng/g (pear), 33.7 ng/g (Peach); Thiacloprid: 36.4 ng/g (pear), 23.7 ng/ | - | [81] |

| SERS | Portable Raman spectrometer (785 nm) | Thiram; Carbendazim; TBZ; Carbaryl | -- | 4.65 | <10-15mol/L | - | [87] |

2.2. Infrared Spectroscopy

2.1.2. Principles

2.2.2. Research Progress of Infrared Spectroscopy in Pesticide Detection

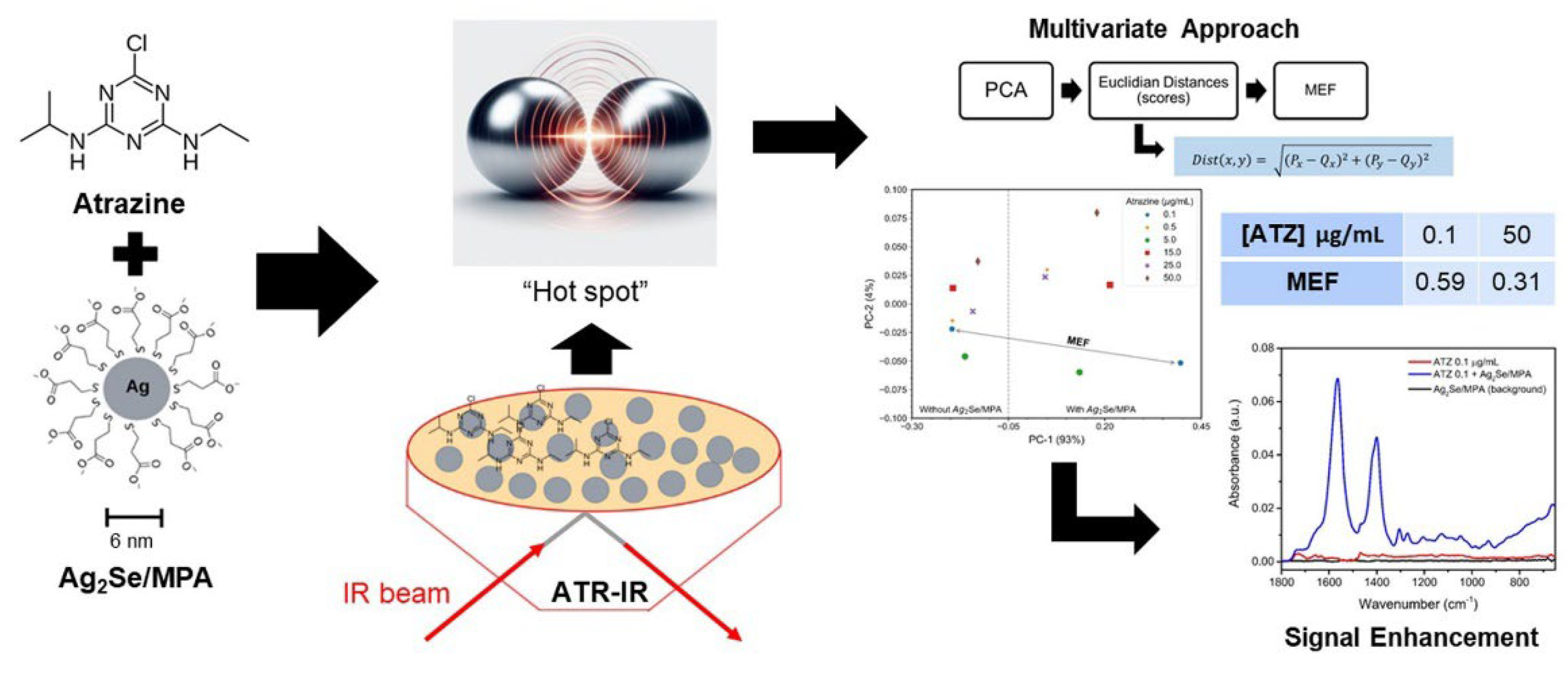

High-Performance SEIRA Enabled by Metallic Nanostructures

SEIRA Substrates Based on Hybrid Perovskites

Methodological Innovations and Hyphenated Techniques in SEIRA

2.3. Fluorescence Spectroscopy

2.3.1. Principle

2.3.2. Applications of Fluorescence Spectroscopy in Pesticide Residue Detection

Application of NIR Fluorescent Probes in the Detection of Organophosphorus Pesticides

Application of Fluorescent Probes Based on Novel Functional Materials in Pesticide Detection

Application of Fluorescence Sensors Based on Functional Materials in Pesticide Detection

Advances in Multimodal Pesticide Residue Detection Based on Fluorescence Spectroscopy

2.3.3. Comparison of Various SERS Detection Methods based on Fluorescence spectrum

2.4. UV-Vis Spectroscopy

2.4.1. Principle

2.4.2. Applications of UV-Vis Spectroscopy in Pesticide Detection UV Spectrophotometry

Derivatization-Based Colorimetric Technology

Enzyme Inhibition Assay

2.5. HSI Technology

2.5.1. Principle

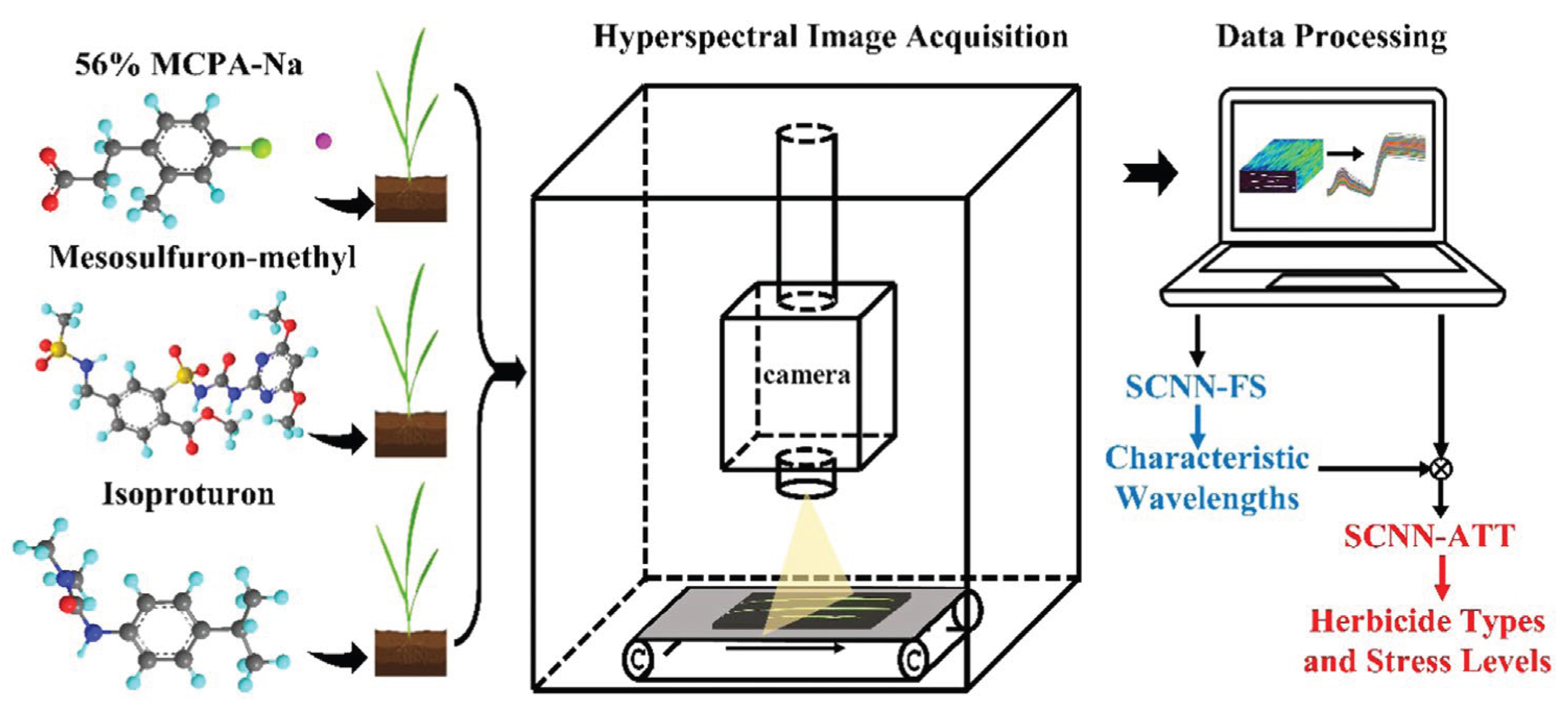

2.5.2. Applications of HSI in Pesticide Detection

3. Research Limitations and Future Directions of Spectroscopic Techniques

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, W.; Jiang, W.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Residue behaviors of six pesticides during apple juice production and storage. Food Res. Int. 2024, 177, 113894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jayan, H.; Gao, S.; Zhou, R.; Yosri, N.; Zou, X.; Guo, Z. Recent and emerging trends of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)-based sensors for detecting food contaminants: A critical and comprehensive review. Food Chem. 2024, 448, 139051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.; Gao, Q.; Shi, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, Y. Residue changes of five pesticides during the production and storage of rice flour. Food Addit. Contam., Part A 2022, 39, 542–550. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, J.; Tao, W.; Liang, Y.; He, X.; Wang, H.; Zeng, H.; Wang, Z.; Luo, X.; Sun, J.; Wang, P.; Zang, Y. Multi-scale monitoring for hazard level classification of Brown Planthopper damage in rice using hyperspectral technique. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2024, 17, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Dai, L.; Huang, Z.; Gong, C.; Chen, J.; Xie, J.; Qu, M. Corn Seed Quality Detection Based on Spectroscopy and Its Imaging Technology: A Review. Agriculture 2025, 15, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Ye, C.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Su, H.E.M.; Chen, X.; Su, T.; Yu, J.; Qian, X. Discovery of Enantiopure (S)-Methoprene Derivatives as Potent Biochemical Pesticide Candidates. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 72, 24979–24988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Okonkwo, C.E.; Chen, L.; Zhou, C. Multimode ultrasonic-assisted decontamination of fruits and vegetables: A review. Food Chem. 2024, 450, 139356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Li, H.; Zareef, M.; Khan, I.M.; Iqbal, M.W.; Niazi, S.; Raza, H.; Yan, Y.; Chen, Q. Recent Advances in Food Safety Detection: Split Aptamer-Based Biosensors Development and Potential Applications. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2025, 73, 4397–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, C.; Bodian, E.H.T.; Thiaré, D.D.; Diouf, D.; Diop, N.A.; Bakhoum, J.-P.; Cisse, L.; Diaw, P.A.; Coly, A.; Giamarchi, P. Development of a new spectral database of photo-induced pesticide compounds for an automatic monitoring and identification system. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1335, 343475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Gao, Z.; Guo, X.; Chen, G. Aptamer-Based Detection Methodology Studies in Food Safety. Food Anal. Methods 2019, 12, 966–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Peng, W.; Ji, Y.; Wei, J.; Che, J.; Huang, Y.; Huang, W.; Yang, W.; Xu, W. A self-powered photoelectrochemical aptasensor using 3D-carbon nitride and carbon-based metal-organic frameworks for high-sensitivity detection of tetracycline in milk and water. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 8022–8035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marimuthu, M.; Xu, K.; Song, W.; Chen, Q.; Wen, H. Safeguarding food safety: Nanomaterials-based fluorescent sensors for pesticide tracing. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.H.H.; Muthu, A.; Elsakhawy, T.; Sheta, M.H.; Abdalla, N.; El-Ramady, H.; Prokisch, J. Carbon Nanodots-Based Sensors: A Promising Tool for Detecting and Monitoring Toxic Compounds. Nanomater. 2025, 15, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azam, S.M.R.; Ma, H.; Xu, B.; Devi, S.; Stanley, S.L.; Siddique, M.A.B.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Zhu, J. Multi-frequency multi-mode ultrasound treatment for removing pesticides from lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) and effects on product quality. Lwt 2021, 143, 111147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Zhou, X.; Yu, D.; Jiao, S.; Han, X.; Zhang, S.; Yin, H.; Mao, H. Pesticide residues identification by impedance time-sequence spectrum of enzyme inhibition on multilayer paper-based microfluidic chip. J. Food Process Eng. 2020, 43, 13544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, T.; Wu, B.; Zhou, H. Identification of lambda-cyhalothrin residues on Chinese cabbage using fuzzy uncorrelated discriminant vector analysis and MIR spectroscopy. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2022, 15, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; Jun, S.; Bing, L.; Xiaohong, W.; Chunxia, D.; Ning, Y. Study on pesticide residues classification of lettuce leaves based on polarization spectroscopy. J. Food Process Eng. 2018, 41, 12903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Liao, J.-D.; Sivashanmugan, K.; Liu, B.H.; Fu, W.-e.; Chen, C.-C.; Chen, G.D.; Juang, Y.-D. Gold Nanoparticle-Coated ZrO2-Nanofiber Surface as a SERS-Active Substrate for Trace Detection of Pesticide Residue. Nanomater. 2018, 8, 402. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Liu, Z.; Yang, F.; Bu, Q.; Song, X.; Yuan, S. Multimodal Fusion-Driven Pesticide Residue Detection: Principles, Applications, and Emerging Trends. Nanomater. 2025, 15, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Guo, Z.; Fernandes Barbin, D.; Dai, Z.; Watson, N.; Povey, M.; Zou, X. Hyperspectral Imaging and Deep Learning for Quality and Safety Inspection of Fruits and Vegetables: A Review. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2025, 73, 10019–10035. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Yang, Y.; Tan, M.; Xia, H.; Peng, Y.; Fu, X.; Huang, Y.; Yang, X.; Ma, X. Rapid pesticide residues detection by portable filter-array hyperspectral imaging. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2025, 330, 125703. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Nie, C.; He, F.; Wu, G.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Du, C.; Zheng, Z.; Cheng, J.; Shen, Y.; Cheng, J. Oxidase-like nanozymes-driven colorimetric, fluorescence and electrochemiluminescence assays for pesticide residues. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 150, 104597. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, Q.; Chen, Q.; Ahmad, W.; Pan, J.; Zhao, S.; Xia, Y.; Ouyang, Q.; Chen, Q. Quantitative analysis and visualization of chemical compositions during shrimp flesh deterioration using hyperspectral imaging: A comparative study of machine learning and deep learning models. Food Chem. 2025, 481, 143997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Xu, S.; Wu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Duan, Y.; Li, Z.; Cao, H.; Zeng, J.; Shen, T.; Pan, L.; Xin, Z.; Fang, W.; Zhu, X. Authenticating vintage in white tea: Appearance-taste-aroma-based three-in-one non-invasive anticipation. Food Res. Int. 2025, 199, 115394. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Wu, X.; Wu, B.; Tan, Y.; Liu, J. Qualitative Analysis of Lambda-Cyhalothrin on Chinese Cabbage Using Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy Combined with Fuzzy Feature Extraction Algorithms. Agric. 2021, 11, 275. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Sun, J.; Xin, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, X.; Li, Q. Visualizing distribution of pesticide residues in mulberry leaves using NIR hyperspectral imaging. J. Food Process Eng. 2016, 40, 12510. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Cong, S.; Mao, H.; Wu, X.; Yang, N. Quantitative detection of mixed pesticide residue of lettuce leaves based on hyperspectral technique. J. Food Process Eng. 2017, 41, 12654. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, N.; Tao, S.; Mao, H.; Wei, M.; Fu, J.; Song, W. An Integrated Platform and Method for Rapid High-Throughput Quantitative Detection of Organophosphorus Pesticide Residues. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 9511011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.A.N.; Adade, S.Y.-S. S.; Ekumah, J.-N.; Kwadzokpui, B.A.; Xu, J.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Q. A comprehensive review of analytical techniques for spice quality and safety assessment in the modern food industry. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bērziņš, K.; Sales, R.E.; Barnsley, J.E.; Walker, G.; Fraser-Miller, S.J.; Gordon, K.C. Low-wavenumber Raman spectral database of pharmaceutical excipients. Vib. Spectrosc. 2020, 107, 103021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.A.F.; Jussiani, E.I.; Appoloni, C.R. Reference Raman Spectral Database of Commercial Pesticides. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 2019, 86, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, P. Raman Spectra of Pesticides on the Surface of Fruits. J. Light Scattering. 2004, 16, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, G.; Shen, X.; Ren, H.; Rao, Y.; Weng, S.; Tang, X. Kernel principal component analysis and differential non-linear feature extraction of pesticide residues on fruit surface based on surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 956778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Jiang, H. Monitoring of Chlorpyrifos Residues in Corn Oil Based on Raman Spectral Deep-Learning Model. Foods 2023, 12, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.-H.; Chang, C.-W.; Tseng, Y.-R.; Yau, H.-T. Efficient, automatic, and optimized portable Raman-spectrum-based pesticide detection system. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2024, 308, 123787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosri, N.; Gao, S.; Zhou, R.; Wang, C.; Zou, X.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Guo, Z. Innovative quantum dots-based SERS for ultrasensitive reporting of contaminants in food: Fundamental concepts and practical implementations. Food Chem. 2025, 467, 142395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, R.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X. Recent Advances in Food Safety: Nanostructure-Sensitized Surface-Enhanced Raman Sensing. Foods 2025, 14, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayan, H.; Zhou, R.; Zheng, Y.; Xue, S.; Yin, L.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Zou, X.; Guo, Z. Microfluidic-SERS platform with in-situ nanoparticle synthesis for rapid E. coli detection in food. Food Chem. 2025, 471, 142800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Zareef, M.; Xu, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, Q. SERS based sensor for mycotoxins detection: Challenges and improvements. Food Chem. 2021, 344, 128652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitjar, J.; Liao, J.-D.; Lee, H.; Liu, B.H.; Fu, W.-e. SERS-Active Substrate with Collective Amplification Design for Trace Analysis of Pesticides. Nanomater. 2019, 9, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashiagbor, K.; Jayan, H.; Yosri, N.; Amaglo, N.K.; Zou, X.; Guo, Z. Advancements in SERS based systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment for detection of pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Hassan, M.M.; Wu, J.; Mu, X.; Li, H.; Chen, Q. Competitive Ratiometric Aptasensing with Core-Internal Standard-Shell Structure Based on Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2022, 71, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wu, X.; Jayan, H.; Yin, L.; Xue, S.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Zou, X. Recent developments and applications of surface enhanced Raman scattering spectroscopy in safety detection of fruits and vegetables. Food Chem. 2024, 434, 137469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Qian, H.; Zhu, A.; Guo, Z.; Chen, Q.; Xu, Y. Au octahedrons monolayer film SERS substrate coupled with a hybrid metaheuristic algorithm-optimized ELM model: An analytical strategy for rapid and label-free detection of zearalenone in corn oil. Food Chem. 2025, 476, 143516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Wang, P.; Xue, C.Y.; Sun, J.; Mao, H.P.; Oppong, P.K. A portable detection method for organophosphorus and carbamates pesticide residues based on multilayer paper chip. J. Food Process Eng. 2018, 41, 12867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Qian, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhai, X.; Zhu, J. A Sensitive SERS Sensor Combined with Intelligent Variable Selection Models for Detecting Chlorpyrifos Residue in Tea. Foods 2024, 13, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aheto, J.H.; Huang, X.; Tian, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Yu, S. Activated carbon@silver nanoparticles conjugates as SERS substrate for capturing malathion analyte molecules for SERS detection. J. Food Saf. 2023, 43, 13072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yao, J.; Quan, Y.; Hu, M.; Su, R.; Gao, M.; Han, D.; Yang, J. Monitoring the charge-transfer process in a Nd-doped semiconductor based on photoluminescence and SERS technology. Light Sci. Appl. 2020, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Chen, P.; Yosri, N.; Chen, Q.; Elseedi, H.R.; Zou, X.; Yang, H. Detection of Heavy Metals in Food and Agricultural Products by Surface-enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Food Rev. Int. 2021, 39, 1440–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, A.; Han, J.; Yang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, G.; Xu, X.; Xu, D.; Lv, J.; Chen, J.; Lv, H.; Liu, G.L. A pH-responsive MOFs@ MPN nanocarrier with enhancing antifungal activity for sustainable controlling myclobutanil release. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 155713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Shi, G.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, W. Au-Decorated Dragonfly Wing Bioscaffold Arrays as Flexible Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) Substrate for Simultaneous Determination of Pesticide Residues. Nanomater. 2018, 8, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shen, Y.; Khalifa, S.A.M.; Huang, X.; Shi, J.; Li, Z.; Zou, X. Green and sustainable self-cleaning flexible SERS base: Utilized for cyclic-detection of residues on apple surface. Food Chem. 2024, 441, 138345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Mehedi Hassan, M.; Wang, J.; Wei, W.; Zou, M.; Ouyang, Q.; Chen, Q. Investigation of nonlinear relationship of surface enhanced Raman scattering signal for robust prediction of thiabendazole in apple. Food Chem. 2021, 339, 127843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, K.; Kim, J.; You, J.; Kim, D.W.; Kim, J. Highly sensitive thin SERS substrate by sandwich nanoarchitecture using multiscale nanomaterials for pesticide detection on curved surface of fruit. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 494, 138450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Geng, W.; Hassan, M.M.; Zuo, M.; Wei, W.; Wu, X.; Ouyang, Q.; Chen, Q. Rapid detection of chloramphenicol in food using SERS flexible sensor coupled artificial intelligent tools. Food Control 2021, 128, 108186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhai, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, C.; Zou, X.; Li, Z.; Shi, J.; Huang, X. Facile fabrication of three-dimensional gold nanodendrites decorated by silver nanoparticles as hybrid SERS-active substrate for the detection of food contaminants. Food Control 2021, 122, 107772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Ahmad, W.; Jiao, T.; Zhu, A.; Ouyang, Q.; Chen, Q. Label-free Au NRs-based SERS coupled with chemometrics for rapid quantitative detection of thiabendazole residues in citrus. Food Chem. 2022, 375, 131681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Han, E.; Yin, L.; Xu, Q.; Zou, C.; Bai, J.; Wu, W.; Cai, J. Simultaneous detection of mixed pesticide residues based on portable Raman spectrometer and Au@Ag nanoparticles SERS substrate. Food Control 2023, 153, 109951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hu, W.; Hassan, M.M.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Q. A facile and sensitive SERS-based biosensor for colormetric detection of acetamiprid in green tea based on unmodified gold nanoparticles. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 13, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Zareef, M.; Jiao, T.; Liu, S.; Xu, Y.; Viswadevarayalu, A.; Li, H.; Chen, Q. Signal optimized rough silver nanoparticle for rapid SERS sensing of pesticide residues in tea. Food Chem. 2021, 338, 127796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, T.; Mehedi Hassan, M.; Zhu, J.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, W.; Wang, J.; Lv, C.; Chen, Q.; Li, H. Quantification of deltamethrin residues in wheat by Ag@ZnO NFs-based surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy coupling chemometric models. Food Chem. 2021, 337, 127652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aheto, J.H.; Huang, X.; Wang, C.; Tian, X.; Yi, R.; Yuena, W. Fabrication and evaluation of chitosan modified filter paper for chlorpyrifos detection in wheat by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 7323–7330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ji, B.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, L.; Luo, M.; Wei, J.; Wang, Y.; Zou, L.; Liang, Y.; Zhou, B.; Li, P. Semi-wrapped gold nanoparticles for surface-enhanced Raman scattering detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 228, 115191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adade, S.Y.-S. S.; Lin, H.; Johnson, N.A.N.; Afang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Haruna, S.A.; Ekumah, J.-N.; Agyekum, A.A.; Li, H.; Chen, Q. Rapid quantitative analysis of acetamiprid residue in crude palm oil using SERS coupled with random frog (RF) algorithm. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 125, 105818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torović, L.; Vuković, G.; Dimitrov, N. Pesticide residues in fruit juice in Serbia: Occurrence and health risk estimates. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 99, 103889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Li, N.; Wang, D.; Xu, G.; Zhang, X.; Gong, H.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Pang, H.; Gao, M.; Liang, X. A Novel 3D Hierarchical Plasmonic Functional Cu@Co3O4@Ag Array as Intelligent SERS Sensing Platform with Trace Droplet Rapid Detection Ability for Pesticide Residue Detection on Fruits and Vegetables. Nanomater. 2021, 11, 3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Yang, X.; Yin, L.; Han, E.; Wang, C.; Zhou, R.; Bai, J.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Cai, J. Rapid dual-modal detection of two types of pesticides in fruits using SERS-based immunoassay. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 136, 106781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yin, L.; Jayan, H.; Jiang, S.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Zou, X.; Guo, Z. In situ self-cleaning PAN/Cu2O@Ag/Au@Ag flexible SERS sensor coupled with chemometrics for quantitative detection of thiram residues on apples. Food Chem. 2025, 473, 143032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Fang, H.; Feng, X.; He, Y.; Liu, X.; Shi, Y.; Wei, Y.; Hong, Z.; Fan, Y. Rapid Trace Detection of Pesticide Residues on Tomato by Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy and Flexible Tapes. J. Food Qual. 2022, 2022, 6947775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Hang, X.; Li, Z.; Zou, X. Convenient self-assembled PDADMAC/PSS/Au@Ag NRs filter paper for swift SERS evaluate of non-systemic pesticides on fruit and vegetable surfaces. Food Chem. 2023, 424, 136232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsammarraie, F.K.; Lin, M. Using Standing Gold Nanorod Arrays as Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) Substrates for Detection of Carbaryl Residues in Fruit Juice and Milk. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2017, 65, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Zou, X.; Li, Z.; Wei, R. Facile synthesis of Au@Ag core–shell nanorod with bimetallic synergistic effect for SERS detection of thiabendazole in fruit juice. Food Chem. 2022, 370, 131276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neo, E.R.K.; Low, J.S.C.; Goodship, V.; Debattista, K. Deep learning for chemometric analysis of plastic spectral data from infrared and Raman databases. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 188, 106718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hassan, M.M.; Ali, S.; Li, H.; Ouyang, Q.; Chen, Q. Self-Cleaning-Mediated SERS Chip Coupled Chemometric Algorithms for Detection and Photocatalytic Degradation of Pesticides in Food. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2021, 69, 1667–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, A.; Xu, Y.; Ali, S.; Ouyang, Q.; Chen, Q. Au@Ag nanoflowers based SERS coupled chemometric algorithms for determination of organochlorine pesticides in milk. Lwt 2021, 150, 111978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Agyekum, A.A.; Kutsanedzie, F.Y.H.; Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Ouyang, Q.; Jiang, H. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of chlorpyrifos residues in tea by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) combined with chemometric models. Lwt 2018, 97, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Luo, X.; Haruna, S.A.; Zareef, M.; Chen, Q.; Ding, Z.; Yan, Y. Au-Ag OHCs-based SERS sensor coupled with deep learning CNN algorithm to quantify thiram and pymetrozine in tea. Food Chem. 2023, 428, 136798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neng, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, P. Trace analysis of food by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy combined with molecular imprinting technology: Principle, application, challenges, and prospects. Food Chem. 2023, 429, 136883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- arooq, S.; Chen, B.; Gao, F.; Muhammad, I.; Ahmad, S.; Wu, H. Development of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers for Fenthion Detection in Food and Soil Samples. Nanomater. 2022, 12, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhai, W.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Lin, H.; Han, S. Electrokinetic Preseparation and Molecularly Imprinted Trapping for Highly Selective SERS Detection of Charged Phthalate Plasticizers. Anal. Chem. 2020, 93, 946–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Hu, Y.; Yu, H.; Sun, S.; Xu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Cong, S.; She, Y. Detection of neonicotinoids in agricultural products using magnetic molecularly imprinted polymers-surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Talanta 2024, 266, 125000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neng, J.; Liao, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, K. Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Pentachloronitrobenzene by Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Combined with Molecularly Imprinted Polymers. Biosensors 2022, 12, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; She, Y.; Cao, X.; Ma, J.; Chen, G.; Hong, S.; Shao, Y.; Abd El-Aty, A.M.; Wang, M.; Wang, J. A molecularly imprinted polymer with integrated gold nanoparticles for surface enhanced Raman scattering based detection of the triazine herbicides, prometryn and simetryn. Microchim. Acta 2019, 186, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Hassan, M.M.; Ali, S.; Li, H.; Chen, Q. SERS-based rapid detection of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid in food matrices using molecularly imprinted magnetic polymers. Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Jiang, J.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Yan, Y.; Li, C. Preparation of a self-cleanable molecularly imprinted sensor based on surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy for selective detection of R6G. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 4627–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, M.Z.; Feng, S.; Wang, S.; Lu, X. Rapid detection and quantification of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid in milk using molecularly imprinted polymers–surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2018, 258, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Song, J.; Feng, S.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G. Composite Nanotube Arrays for Pesticide Detection Assisted with Machine Learning Based on SERS Effect. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 9544–9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-L.; You, E.-M.; Panneerselvam, R.; Ding, S.-Y.; Tian, Z.-Q. Advances of surface-enhanced Raman and IR spectroscopies: from nano/microstructures to macro-optical design. Light Sci. Appl. 2021, 10, 161. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Zareef, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Ouyang, Q. Monitoring chlorophyll changes during Tencha processing using portable near-infrared spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2023, 412, 135505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruna, S.A.; Ivane, N.M.A.; Adade, S.Y.-S. S.; Luo, X.; Geng, W.; Zareef, M.; Jargbah, J.; Li, H.; Chen, Q. Rapid and simultaneous quantification of phenolic compounds in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) seeds using NIR spectroscopy coupled with multivariate calibration. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 123, 105516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xie, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zeng, P.; He, S.; Wang, J.; Wei, H.; Yu, C. Surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (SEIRAS) for biochemical analysis: Progress and perspective. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2024, 41, e00226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Ma, B.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Li, C. Nondestructive identification of pesticide residues on the Hami melon surface using deep feature fusion by Vis/NIR spectroscopy and 1D-CNN. J. Food Process Eng. 2020, 44, 13602. [Google Scholar]

- Kesama, M.R.; Yan, F.; Zhang, R.; Wang, S.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, X. A pesticide residue detection model for food based on NIR and SERS. Plos One 2025, 20, e0320456. [Google Scholar]

- Garrigues, S.; de la Guardia, M.; Cassella, A.R.; de Campos, R.C.; Santelli, R.E.; Cassella, R.J. Flow injection-FTIR determination of dithiocarbamate pesticides. The Analyst 2000, 125, 1829–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sun, Z.; Low, T.; Hu, H.; Guo, X.; García de Abajo, F.J.; Avouris, P.; Dai, Q. Nanomaterial-Based Plasmon-Enhanced Infrared Spectroscopy. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1704896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, F.C.S.; de Souza Sobrinha, I.G.; Pereira, G.; Pereira, G.A.L.; Raimundo, I.M.; Pereira, C.F. A surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (SEIRA) multivariate approach for atrazine detection. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2024, 322, 124867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Shi, L.; Luo, B.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Fan, M.; Gong, Z. Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis. 2020, 40, 1809–1814. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, J.; Zhao, C.; Zou, Y.; Kong, W.; Yu, Z.; Shan, Y.; Dong, Q.; Zhou, D.; Yu, W.; Guo, C. Modulating the optical and electrical properties of MAPbBr3 single crystals via voltage regulation engineering and application in memristors. Light Sci. Appl. 2020, 9, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Mo, Z. Based on the hybrid perovskite surface-enhanced IR research[D]. Chongqing: College of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering of Chongqing University, 2015.

- Shan, L.; Lv, J.; Liang, J.; Xu, J.; Wu, C.; Wang, A.; Zhang, L.; Ge, S.; Li, L.; Yu, J. Spin-State Reconfigurable Magnetic Perovskite-Based Photoelectrochemical Sensing Platform for Sensitive Detection of Acetamiprid. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 2418023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Cai, W. Advances in Electrochemical Surface-Enhanced Infrared Spectroscopy. Electrochemistry. 2013, 19, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Gong, Z.; Luo, B. Preparation of surface enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy substrate and its application in rapid detection of DMDS pesticides[D]. Sichuan: Southwest Jiaotong University, 2013.

- Shi, L.; Sun, J.; Cong, S.; Ji, X.; Yao, K.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, X. Fluorescence hyperspectral imaging for detection of selenium content in lettuce leaves under cadmium-free and cadmium environments. Food Chem. 2025, 481, 144055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A.; Imtiaz, A.; Yaqoob, S.; Awais, M.; Awan, K.A.; Naveed, H.; Khalifa, I.; Al-Asmari, F.; Qian, J.Y. Integration of Fluorescence Spectroscopy Along with Mathematical Modeling for Rapid Prediction of Adulteration in Cooked Minced Beef Meat. J. Food Process Eng. 2024, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Xu, J.; Ye, Y.; Han, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Sun, D.; Zhou, Y.; Ni, Z. Visual detection of mixed organophosphorous pesticide using QD-AChE aerogel based microfluidic arrays sensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 136, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhang, W.; Xu, X.; Zhou, L. Applications and Challenges of Fluorescent Probes for the Detection of Pesticide Residues in Food. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2025, 73, 4982–4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, C.; Ni, S.; Jiang, P.; Fan, P.; Li, L. Dual-Mode Detection of Glyphosate Based on DNAzyme-Mediated Click Chemistry and DNAzyme-Regulated CeO2 Peroxidase-like Activity. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2025, 73, 7496–7503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Ning, X. Detection of Tomato Leaf Pesticide Residues Based on Fluorescence Spectrum and Hyper-Spectrum. Hortic. 2025, 11, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hassan, M.M.; Rong, Y.; Liu, R.; Li, H.; Ouyang, Q.; Chen, Q. A solid-phase capture probe based on upconvertion nanoparticles and inner filter effect for the determination of ampicillin in food. Food Chem. 2022, 386, 132739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Hu, X.; Hao, M.; Shi, J.; Zou, X.; Dusabe, K.D. Upconversion nanoparticles-based background-free selective fluorescence sensor developed for immunoassay of fipronil pesticide. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 3125–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, S.; Li, D.; Wu, J.; Jiao, T.; Wei, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Q. Sulfadiazine detection in aquatic products using upconversion nanosensor based on photo-induced electron transfer with imidazole ligands and copper ions. Food Chem. 2024, 456, 139992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Yang, X.; Xue, S.; Zhou, R.; Wang, C.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cai, J. “Raman plus X” dual-modal spectroscopy technology for food analysis: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, 70102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, N.; Shang, F. A detection method of two carbamate pesticides residues on tomatoes utilizing excitation-emission matrix fluorescence technique. Microchem. J. 2021, 164, 105920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Peng, R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ren, J.; Li, W.; Xiong, Y.; Yi, S.; Wen, Q. Enzyme-targeted near-infrared fluorescent probe for organophosphorus pesticide residue detection. Anal. Bioanal.Chem. 2023, 415, 4849–4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.; Wei, L.; Limeng, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, M.; Song, Y.; Shu, W.; Zeng, C. A novel ultrafast and highly sensitive NIR fluorescent probe for the detection of organophosphorus pesticides in foods and biological systems. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nekoueian, K.; Amiri, M.; Sillanpää, M.; Marken, F.; Boukherroub, R.; Szunerits, S. Carbon-based quantum particles: an electroanalytical and biomedical perspective. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 4281–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Li, H.; Yan, X.; Lin, Y.; Lu, G. Biosensors based on fluorescence carbon nanomaterials for detection of pesticides. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2021, 134, 116126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Li, P.; Tang, B. Recent progresses in fluorescent probes for detection of polarity. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 427, 213582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yan, B.; Lian, X. Wearable glove sensor for non-invasive organophosphorus pesticide detection based on a double-signal fluorescence strategy. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 13722–13729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Yu, S.; Liu, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J. Colorimetric and visual determination of total nereistoxin-related insecticides by exploiting a nereistoxin-driven aggregation of gold nanoparticles. Microchim. Acta 2015, 182, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Hao, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Luo, X.; Fang, G.; Liu, J.; Wang, S. Perspective on recent developments of nanomaterial based fluorescent sensors: applications in safety and quality control of food and beverages. J. Food Drug Anal. 2020, 28, 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimuthu, M.; Arumugam, S.S.; Sabarinathan, D.; Li, H.; Chen, Q. Metal organic framework based fluorescence sensor for detection of antibiotics. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 1002–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhai, X.; Zou, X.; Shi, J.; Huang, X.; Li, Z. A Ratiometric Fluorescent Sensor Based on Silicon Quantum Dots and Silver Nanoclusters for Beef Freshness Monitoring. Foods 2023, 12, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Wang, M.; Shao, Y.; She, Y.; Cao, Z.; Xiao, M.; Jin, F.; Wang, J.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. Fluorescent sensor for rapid detection of organophosphate pesticides using recombinant carboxylesterase PvCarE1 and glutathione-stabilized gold nanoclusters. Microchemical Journal 2024, 200, 110322. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.; Yang, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, A.; Wei, W.; Liu, S. Fluorescence sensor for organophosphorus pesticide detection based on the alkaline phosphatase-triggered reaction. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1131, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irshad, H.; Khadija; Qvortrup, K. Advances in fluorescent sensors for trace detection of metal contaminants and agrochemical residues in soil: A comprehensive review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2025, 191, 118365.

- Wu, N.; Zhao, L.-X.; Jiang, C.-Y.; Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Ye, F. A naked-eye visible colorimetric and fluorescent chemosensor for rapid detection of fluoride anions: Implication for toxic fluorine-containing pesticides detection. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 302, 112549. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Chen, S.-W.; Zhang, B.; Tu, Q.; Wang, J.; Yuan, M.-S. Non-biological fluorescent chemosensors for pesticides detection. Talanta 2022, 240, 123200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Tang, H.; Yang, J.; Luo, X.; Tian, Y.; Yang, M.; Jiang, J.; Wang, M.; Zheng, L.; Ma, C.; Xing, G.; Wang, H.; Li, J. A bionic palladium metal–organic framework based on a fluorescence sensing enhancement mechanism for sensitive detection of phorate. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 934–946. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.-X.; Cheng, J.-H.; Ma, J.; Sun, D.-W. Advancing Aquatic Food Safety Detection Using Highly Sensitive Graphene Oxide and Reduced Graphene Oxide (GO/r-GO) Fluorescent Sensors. Food Eng. Rev. 2024, 16, 618–634. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.-P.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.-Y.; Jia, L.-F.; Yang, A.-Z.; Zhao, W.-T.; Jia, Y.; Yu, B.-Y.; Zhao, H.-Q. Water-stable mixed-ligand Cd(II) metal-organic frameworks as bis-color excited fluorescent sensors for the detection of vitamins and pesticides in aqueous solutions. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1305, 137699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, M.; Thakur, A.; Sharma, A.; Flora, S.J.S. Organic-Molecule-Based Fluorescent Chemosensor for Nerve Agents and Organophosphorus Pesticides. Top. Curr. Chem. 2021, 379, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Gong, Y.; Yang, S.; Qiu, G.; Tian, H.; Sun, B. Determination of carboxylesterase by fluorescence probe to guide detection of carbamate pesticide. Luminescence 2023, 39, 4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, R.; Ma, S.; Yao, H.; Han, Y.; Yang, X.; Chen, R.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, T.; Bian, H. Multiple kinds of pesticide residue detection using fluorescence spectroscopy combined with partial least-squares models. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Cao, W.; Zhang, G.; Ang, E.H.; Su, L.; Liu, C.; He, W.; Lai, W.; Deng, S. Traffic signal-inspired fluorescence lateral flow immunoassay utilizing self-assembled AIENP@Ni/EC for simultaneous multi-pesticide residue detection. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 501, 157565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, Z.; de P., R. Moreira, I.; Bofill, J.M.; Poater, J. Adjusting UV-Vis Spectrum of Alizarin by Insertion of Auxochromes. ChemistryOpen 2024, 13, e202400030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolkarimi-Mahabadi, M.; Bayat, A.; Mohammadi, A. Use of UV-Vis Spectrophotometry for Characterization of Carbon Nanostructures: a Review. Theor. Exp. Chem. 2021, 57, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, X.; Gan, L.; Wang, G. Investigation of UV-vis spectra of azobenzene containing carboxyl groups. J. Mol. Model. 2021, 27, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, N.; Lin, W.; Chen, Z.; Lin, F.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.H. Determination of Orthophenylphenol in Tea by Ultraviolet Spectrophotometry. Fujian Tea 2017, (12), 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, D.; Yu, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Z. Simultaneous Detection of Imidacloprid, Acetamiprid, and Clothianidin in Apple Juice Using Ultraviolet Spectroscopy and the SSA–BPNN Model. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 2025, 92, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Cai, H.; Zeng, Q.; Ni, H. Study on an Alkalinehydrolysis-spectrophotometry for Detecting Organophosphate Pesticide. J. Jimei University (Natural Science), 2009, 14, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Yang, P. Study on the determination of pesticide residues by pre-column fluorescence derivatization and high-performance liquid chromatography[D]. Sichuan: China West Normal University, 2016.

- Liu, A.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, L.; Yang, F.; Lin, D.; Jiang, C. Supramolecular Fluorescence Probe for Rapid Visual Detection of Pyrethroid and Composite Aerogel as a Pyrethroid Vapor Sensor. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 13672–13680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, H.; Hassan, M.M.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Q. Fabricating an Acetylcholinesterase Modulated UCNPs-Cu2+ Fluorescence Biosensor for Ultrasensitive Detection of Organophosphorus Pesticides-Diazinon in Food. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2019, 67, 8b07201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhu, Y.; Qian, L.; Yin, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yang, D.; Qiu, F. Lamellar Ti3C2 MXene composite decorated with platinum-doped MoS2 nanosheets as electrochemical sensing functional platform for highly sensitive analysis of organophosphorus pesticides. Food Chem. 2024, 459, 140379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, J.; Han, L.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Guo, H.; Wei, H. Nanozyme Sensor Arrays Based on Heteroatom-Doped Graphene for Detecting Pesticides. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 9b05110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adade, S.Y.-S. S.; Lin, H.; Johnson, N.A.N.; Nunekpeku, X.; Aheto, J.H.; Ekumah, J.-N.; Kwadzokpui, B.A.; Teye, E.; Ahmad, W.; Chen, Q. Advanced food contaminant detection through multi-source data fusion: Strategies, applications, and future perspectives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 156, 104851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Sun, J.; Shi, L.; Yao, K.; Zhang, B. Application of hyperspectral imaging technology combined with ECA-MobileNetV3 in identifying different processing methods of Yunnan coffee beans. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 143, 107625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, M.; Duan, H.; Bu, Q.; Dong, X. Recent advances of optical sensors for point-of-care detection of phthalic acid esters. Front. Sustainable Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1474831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xie, S.; Ning, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Z. Evaluating green tea quality based on multisensor data fusion combining hyperspectral imaging and olfactory visualization systems. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 99, 1787–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, X.; Mao, H.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q. Discrimination of pesticide residues in lettuce based on chemical molecular structure coupled with wavelet transform and near infrared hyperspectra. J. Food Process Eng. 2016, 40, 12509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Sun, J.; Lu, B.; Ge, X.; Zhou, X.; Zou, M. Application of deep brief network in transmission spectroscopy detection of pesticide residues in lettuce leaves. J. Food Process Eng. 2019, 42, 13005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, X.; Mao, H.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Gao, H. Identification of pesticide residue level in lettuce based on hyperspectra and chlorophyll fluorescence spectra. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2016, 9, 231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Ma, B.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, G. Non-Destructive Detection of Different Pesticide Residues on the Surface of Hami Melon Classification Based on tHBA-ELM Algorithm and SWIR Hyperspectral Imaging. Foods 2023, 12, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, W.; Yan, T.; Zhang, C.; Duan, L.; Chen, W.; Song, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, W.; Gao, P. Detection of Pesticide Residue Level in Grape Using Hyperspectral Imaging with Machine Learning. Foods 2022, 11, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, H.; Zhang, C.; Wang, M.; Gouda, M.; Wei, X.; He, Y.; Liu, Y. Hyperspectral imaging with shallow convolutional neural networks (SCNN) predicts the early herbicide stress in wheat cultivars. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 421, 126706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Ge, X.; Wu, X.; Dai, C.; Yang, N. Identification of pesticide residues in lettuce leaves based on near infrared transmission spectroscopy. J. Food Process Eng. 2018, 41, 12816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, A.; Samiwala, M.; Albo, J.; Jiang, X.; Rao, Q. Challenges in SERS-based pesticide detection and plausible solutions. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2019, 67, 12341–12347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zou, Y.; Sun, B.; Yu, X.; Shang, Z.; Huang, J.; Jin, S.; Liang, P. Raman spectrum classification based on transfer learning by a convolutional neural network: Application to pesticide detection. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2022, 265, 120366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, T.; Zhang, Q.; Ying, Y.; Fu, Y. Portable and durable sensor based on porous MOFs hybrid sponge for fluorescent-visual detection of organophosphorus pesticide. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 216, 114659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Detection Scheme | Data Analysis Method | Pesticides |

Recovery Rate (%) | RSD (%) | LOD | Detection Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence spectrum with biosensor | Fluorescence imaging system | Paraoxon; Dichlorvos; Parathion; Deltamethrin |

98.7–109.2 | 5.46–14.80 | < 1.2 × 10⁻¹² M | <20 min | [105] |

| Fluorescence spectrum with biosensor | Fluorescence immunosensor | Fipronil | 95.95–137.07 | 0.07–0.23 | 0.01 μg/L | - | [110] |

| Fluorescence spectrum | Bionic fluorescence sensor | Phorate | 87.69–106.12 | < 11.16 | 0.0017μg/L | 45 s | [111] |

| Excitation-Emission Matrix Fluorescence Spectroscopy | Fluorescence spectrophotometer (250–600 nm) | Tsumacide (TSU); Carbaryl (CBL) |

TSU: 98.94; CBL: 99.25 |

- | TSU:0.147 ug/mL; CBL:0.159 ug/mL |

<dozens of minutes | [114] |

| NIR Fluorescence | NIR Fluorescent Prob(CES-targeted probe 1) | Isocarbophos; Other typical OPs |

97.63–100.21 | 2.32–5.62 | 0.030 ug/L | Dozens of minutes | [115] |

| NIR Fluorescence | - | Dichlorvos; Trichlorfon |

Dichlorvos:96.50–01.83; Trichlorfon:97.09–102.71 | - | Dichlorvos:18.9 ug/L; Trichlorfon:16.529 ug/L | - | [116] |

| Dual-signal fluorescence spectrum | Glove sensor (365 nm) | Chlorpyrifos (CP) | - | ≤12 | 89 × 10⁻⁹ M | 30 s | [120] |

| Turn-on fluorescence | - | Dichlorvos; Trichlorfon; Profenofos |

84.5–106.3 | 1.3–10.5 | Dichlorvos: 0.2 μg/L; Trichlorfon: 5 μg/L: Profenofo: 5 μg/L |

Within a few minutes | [111] |

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy | Fluorescence Spectrophotometer (425 nm) | Chlorpyrifos | 94.5–106.7 | < 11.51 | 0.015 ng/mL | 180 min | [125] |

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy | - | Phorate | 87.69–106.12 | < 11.16 | 1.7 pg/L | 45 s | [129] |

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy | Dual-color excited fluorescent sensing technology (310 nm and 360 nm) | Atrazine; Carbaryl; Chlorpyrifos; Prometryn |

Atrazine: 96.0– 104.0; Carbaryl: 95.5–103.5; Chlorpyrifos: 997.0–105.0; Prometryn: 96.5– 104.5 | Atrazine: 1.8–3.2; Carbaryl: 2.1–3.5; Chlorpyrifos: 1.6–3.0; Prometryn: 1.9– 3.3 |

Atrazine: 0.091 μM; Carbaryl: 0.103 μM; Chlorpyrifos: 0.087 μM; Prometryn: 0.095 μM |

<5 min | [131] |

| Fluorescence spectrum with Smartphone Image Recognition | - | Carbaryl | 97.85–103.10 | 0.64–1.44 | 27.40× 10⁻⁹ M | Dozens of minutes | [133] |

| Fluorescence spectrum with Partial Least Squares (PLS) model | LS55 Fluorescence Spectrometer(Perkin Elmer) | - | - | - | 0–0.0305 mg/mL | Suitable for online onitoring | [134] |

| Multicolor fluorescence signal | - | Chlorothalonil (CTN); Paclobutrazol (PBZ); Fipronil(FIP) | - | - | CTN: 0.038 ng/mL; PBZ: 0.025 ng/mL; FIP: 0.046 ng/mL |

<5 s | [135] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).