Submitted:

18 September 2025

Posted:

19 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

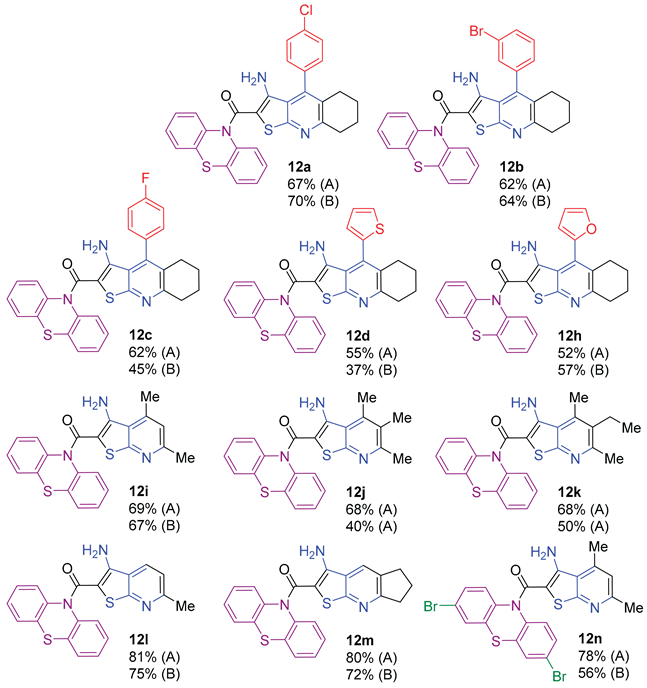

2. Results and Discussion

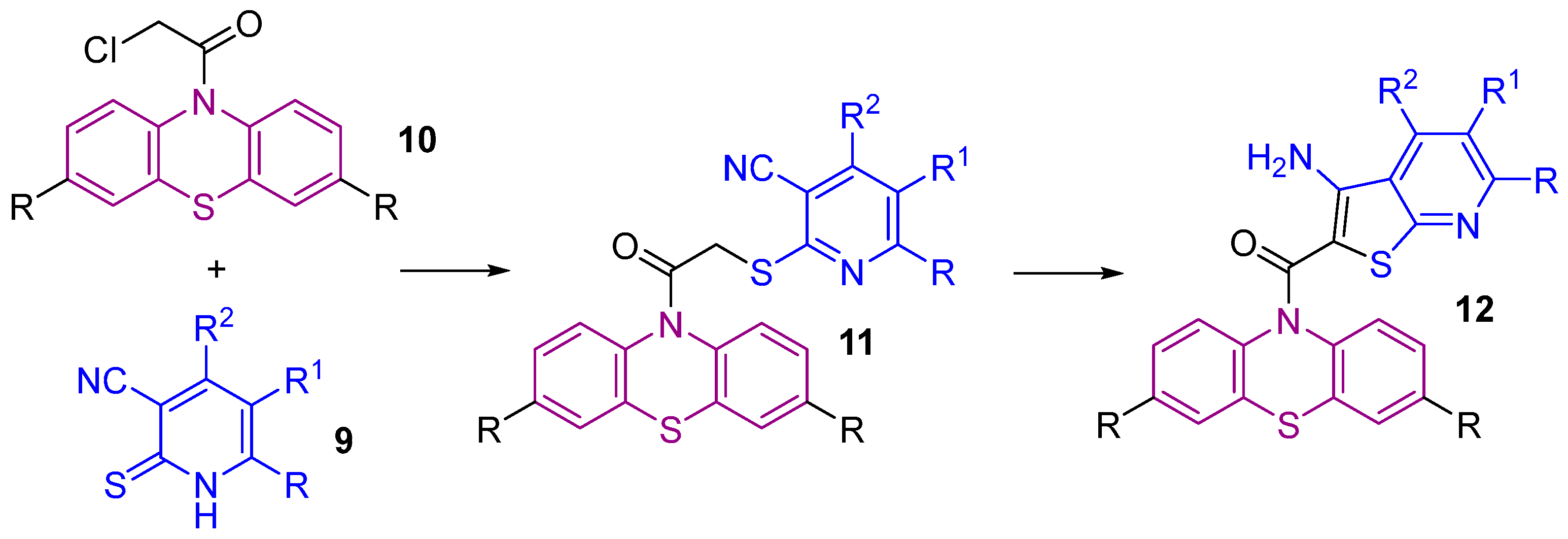

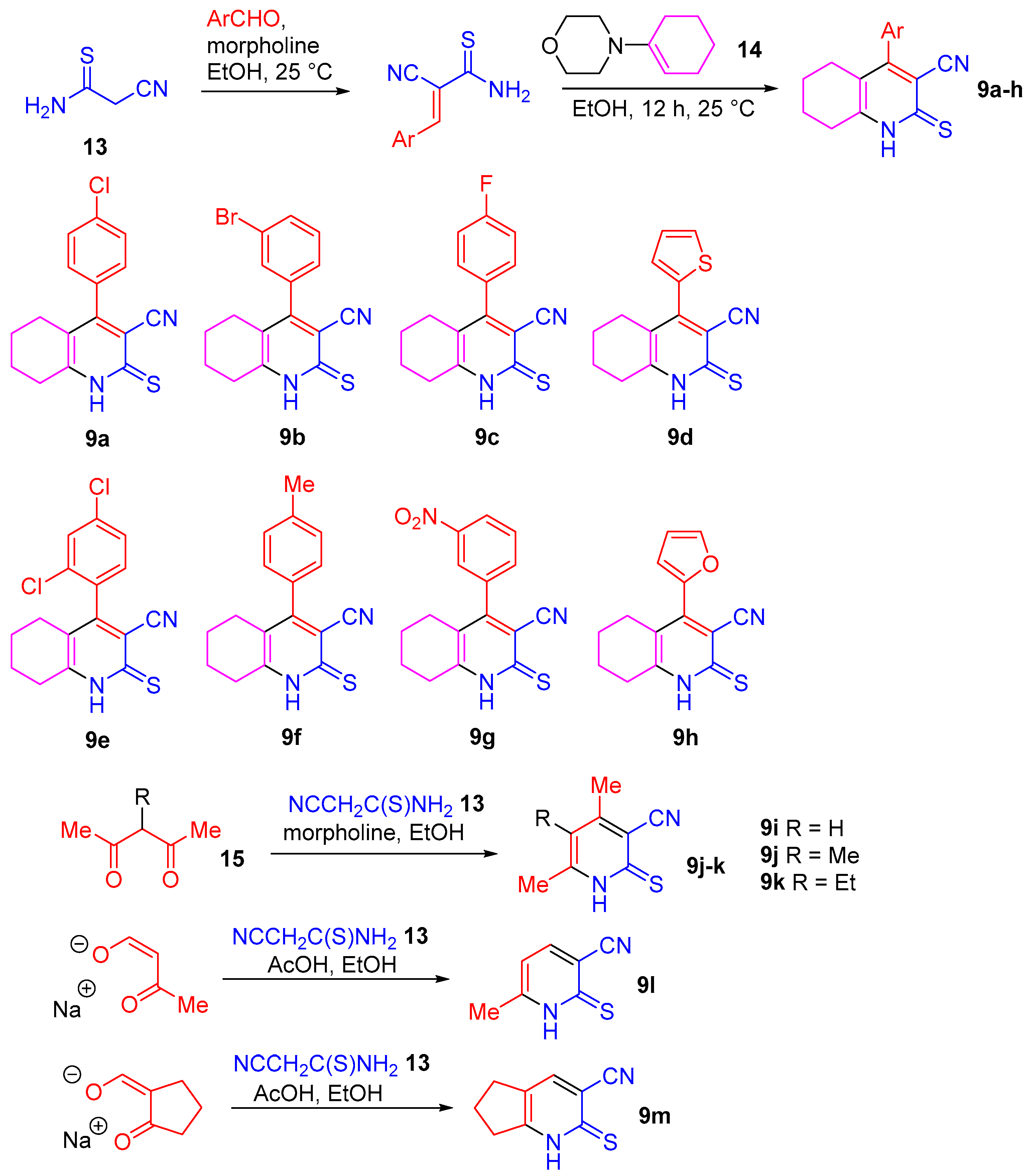

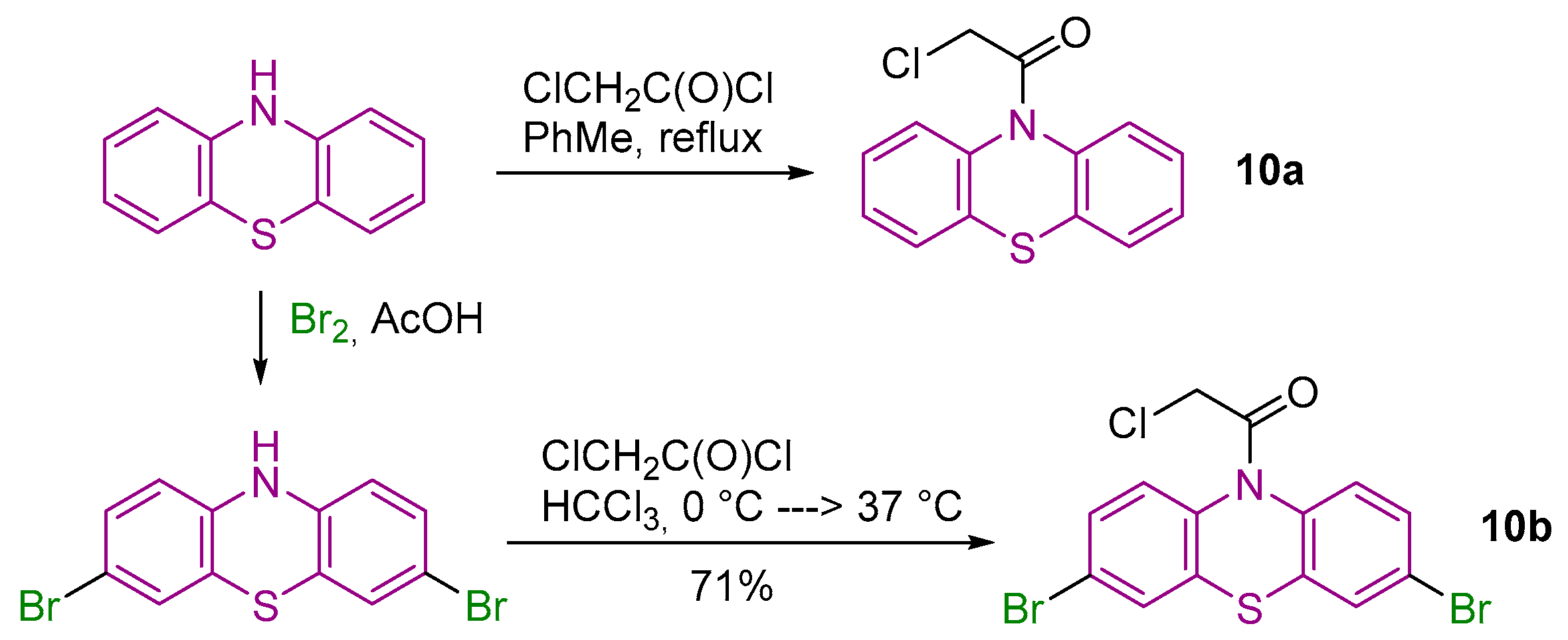

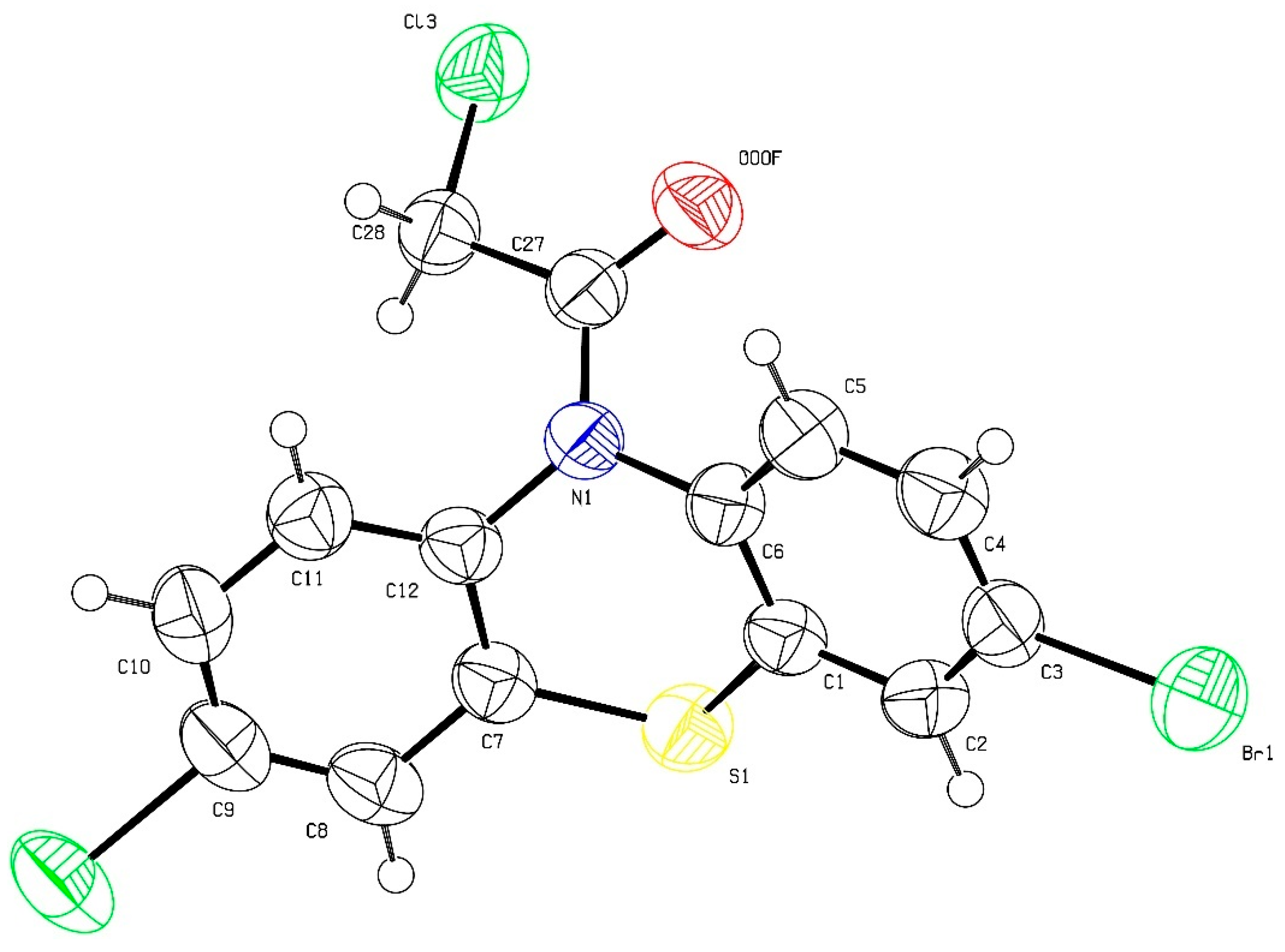

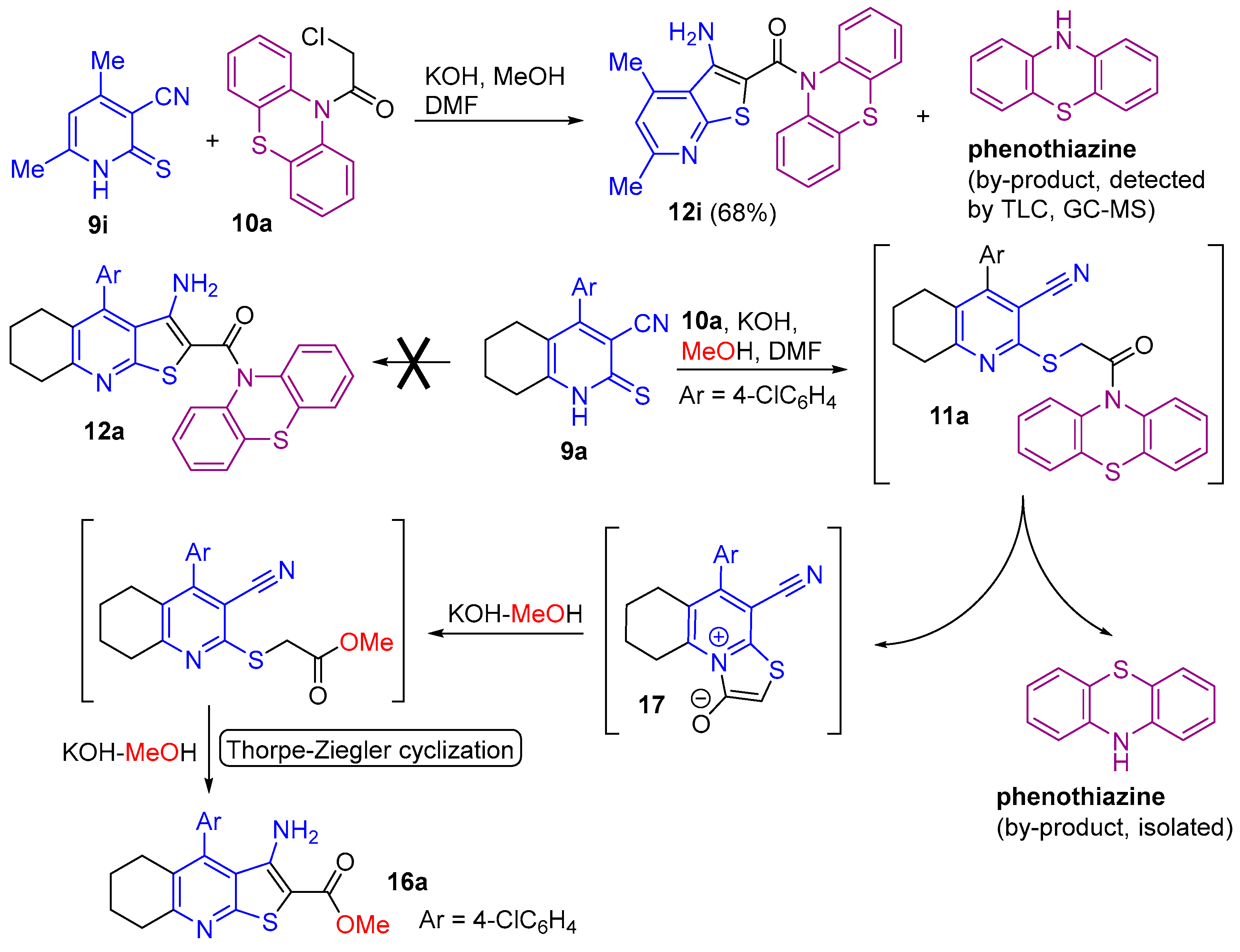

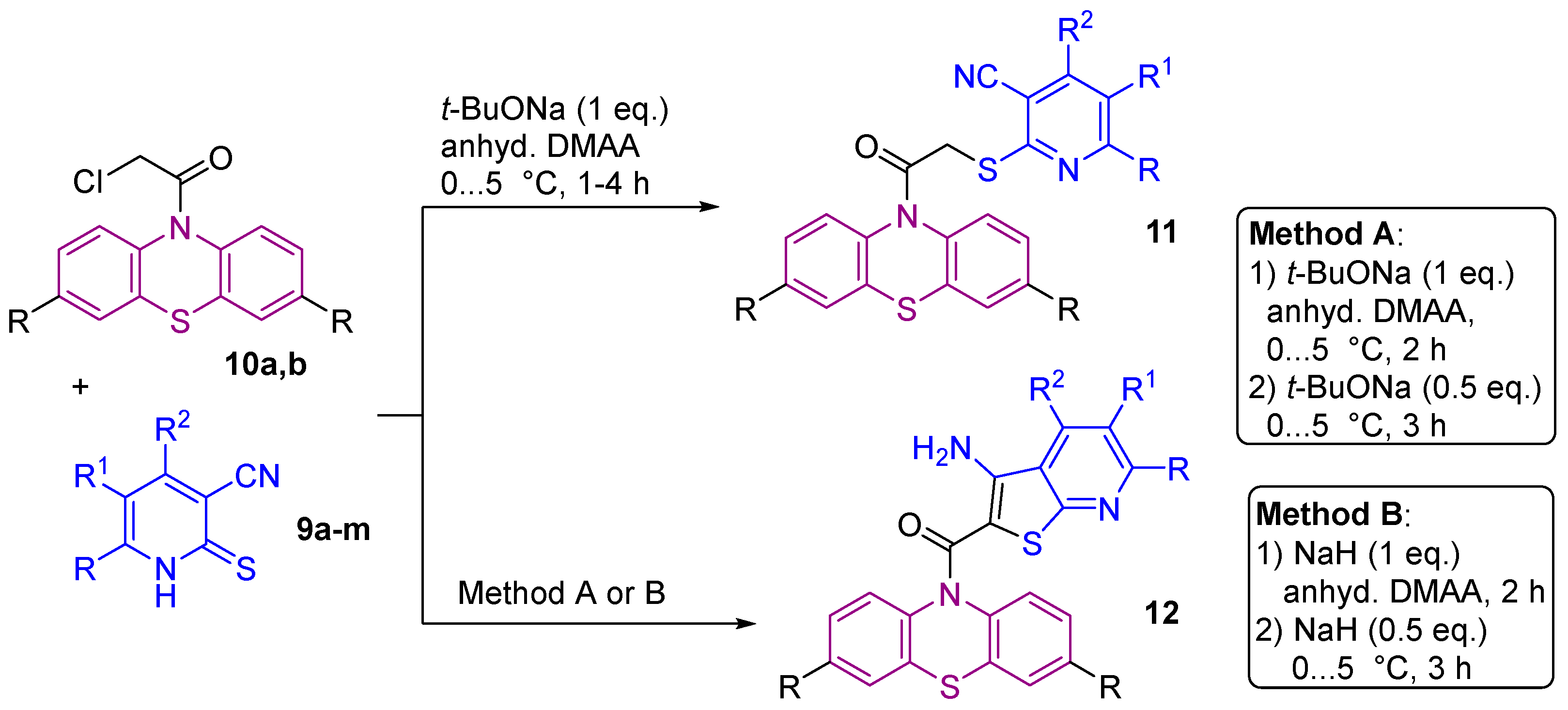

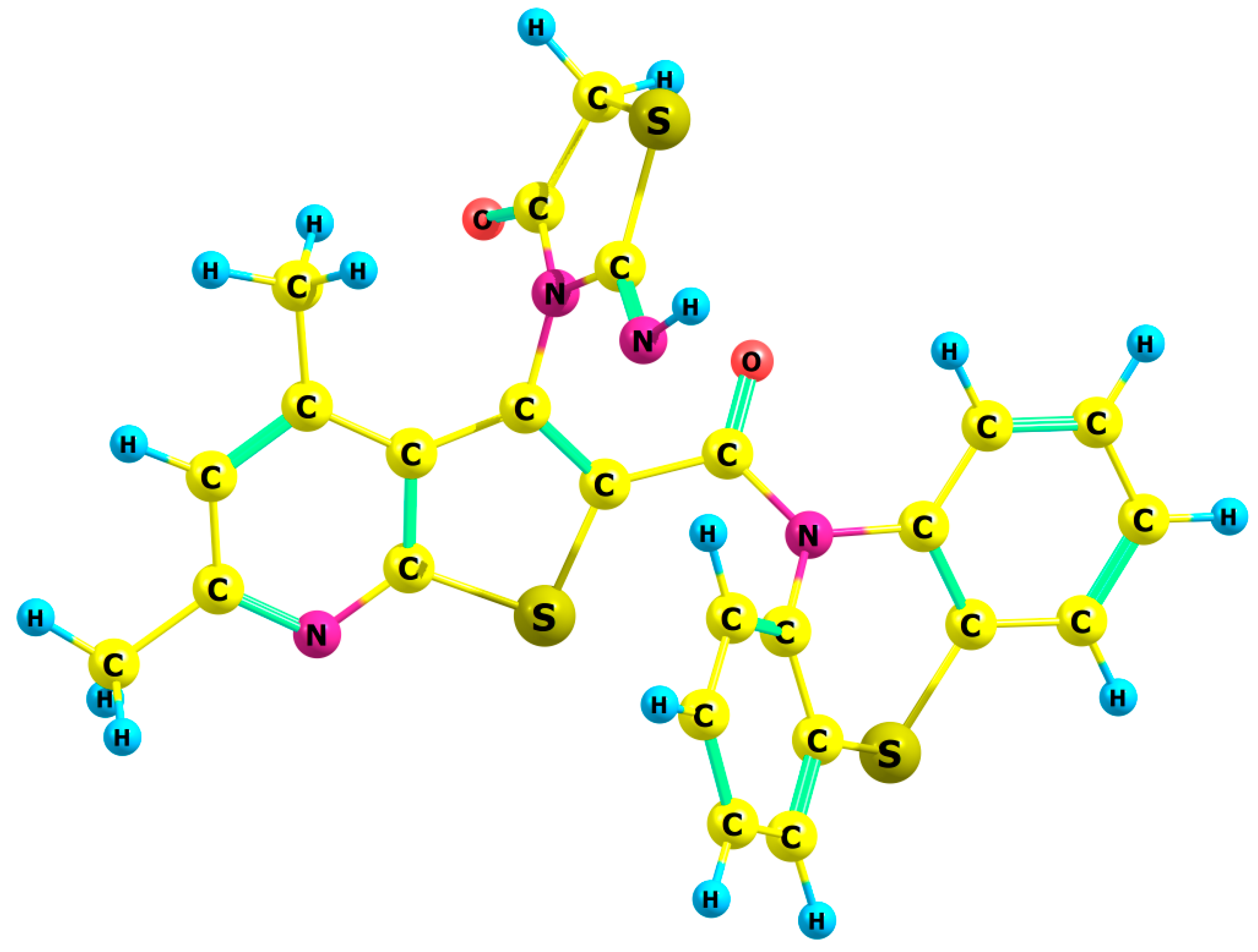

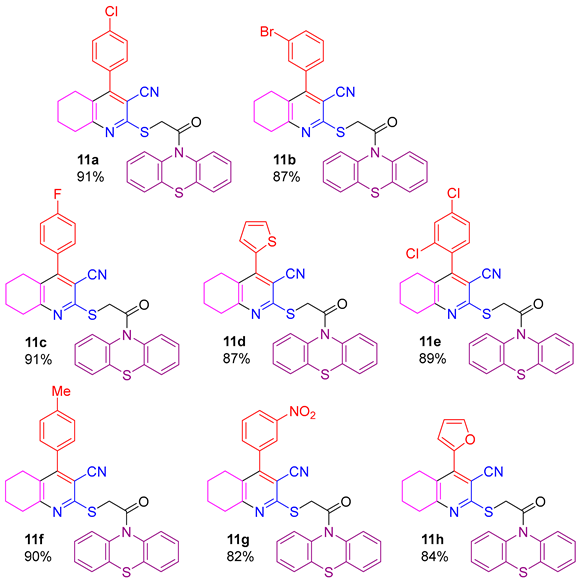

2.1. Synthesis

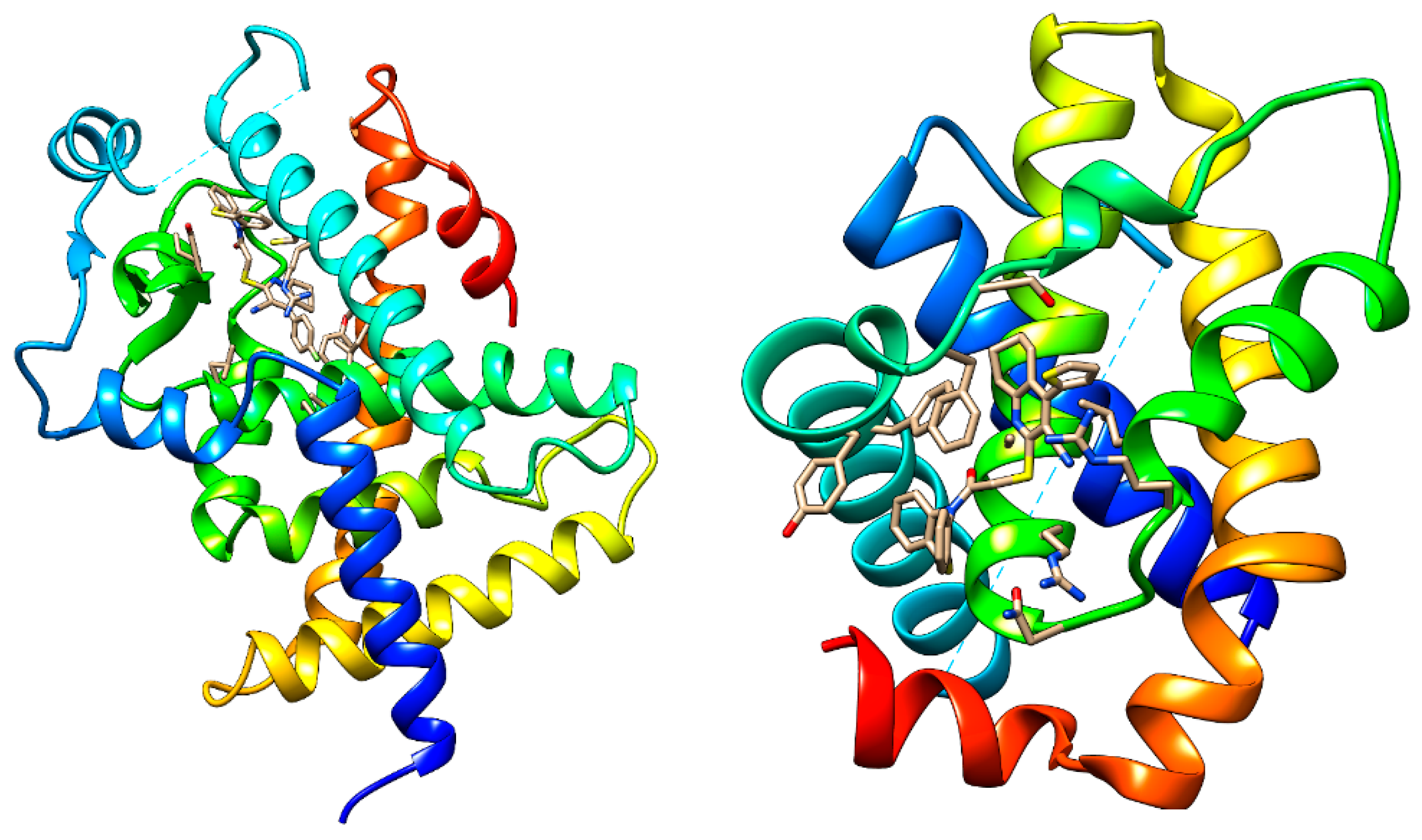

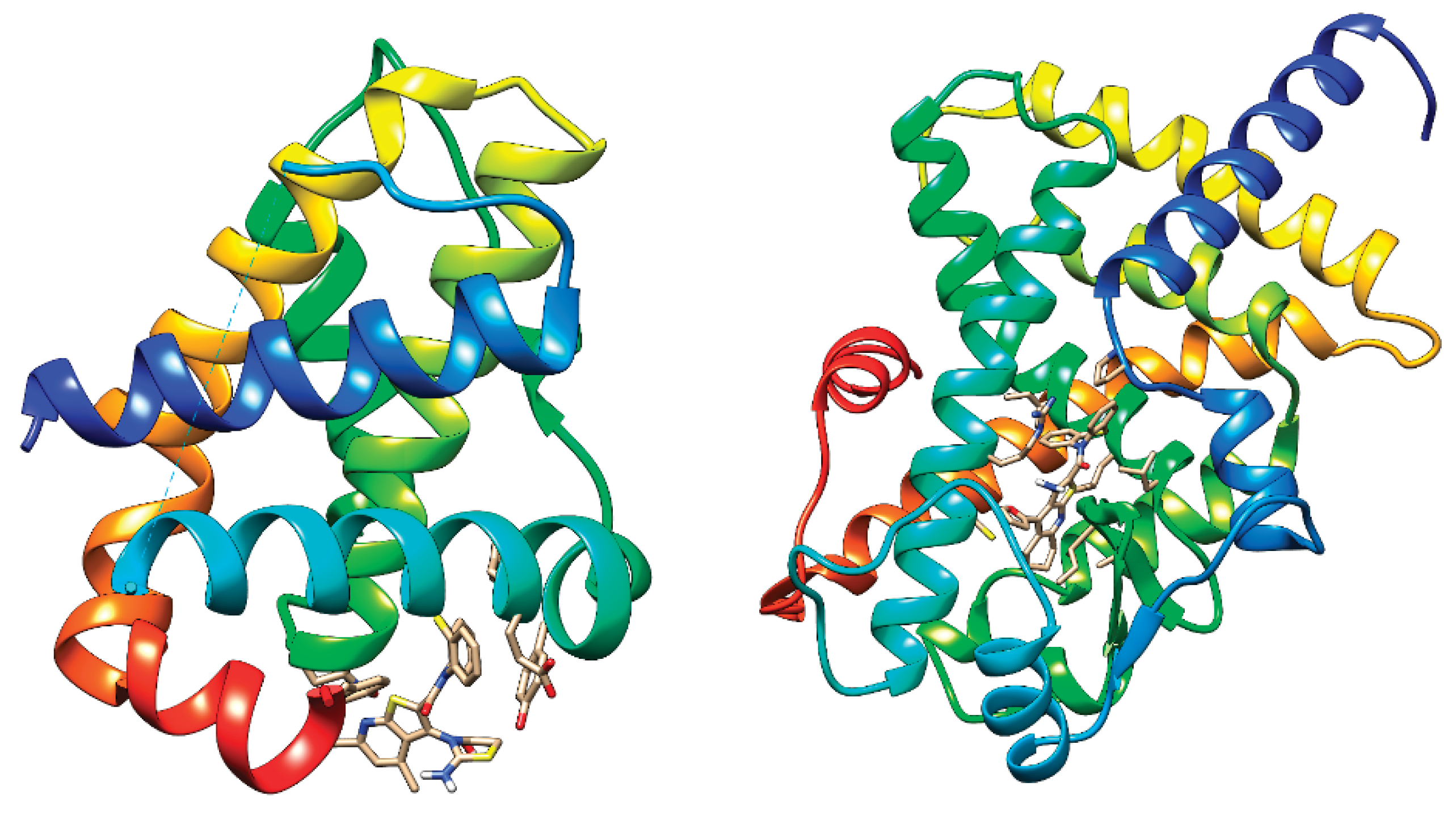

2.2. Drug-Relevant Properties, ADMET and Docking Studies

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soltan, O. M.; Shoman, M. E.; Abdel-Aziz, S. A.; Narumi, A.; Konno, H.; Abdel-Aziz, M. Molecular hybrids: a five-year survey on structures of multiple targeted hybrids of protein kinase inhibitors for cancer therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 225, paper 113768. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. K.; Kumar, A.; Singh, H.; Sonawane, P.; Paliwal, H.; Thareja, S.; Pathak, P.; Grishina, M.; Jaremko, M.; Emwas, A. H.; Yadav, J. P.; Verma, A.; Khalilullah, H.; Kumar, P. Concept of hybrid drugs and recent advancements in anticancer hybrids. Pharmaceuticals. 2022, 15, paper 1071. [CrossRef]

- Alkhzem, A. H.; Woodman, T. J.; Blagbrough, I. S. Design and synthesis of hybrid compounds as novel drugs and medicines. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 19470–19484.

- Bérubé, G. An overview of molecular hybrids in drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2016, 11, 281–305.

- Szumilak, M.; Wiktorowska-Owczarek, A.; Stanczak, A. Hybrid drugs—a strategy for overcoming anticancer drug resistance? Molecules 2021, 26, paper 2601. [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, F.; Liu, J.; Xu, Z. Recent updates on 1,2,3-, 1,2,4-, and 1,3,5-triazine hybrids (2017–present): the anticancer activity, structure–activity relationships, and mechanisms of action. Arch. Pharm. 2023, 356, paper e2200479.

- Xu, Z.; Zhao, S. J.; Liu, Y. 1,2,3-Triazole-containing hybrids as potential anticancer agents: current developments, action mechanisms and structure-activity relationships. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 183, paper 111700. [CrossRef]

- Shagufta; Ahmad, I. Therapeutic significance of molecular hybrids for breast cancer research and treatment. RSC Med. Chem. 2022, 14, 218–238.

- Shalini; Kumar, V. Have molecular hybrids delivered effective anti-cancer treatments and what should future drug discovery focus on? Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2021, 16, 335–363.

- Wang, J.; Shi, Y. Recent Updates on Anticancer Activity of Betulin and Betulinic Acid Hybrids (A Review). Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2023, 93, 610–627.

- de Sena Murteira Pinheiro, P.; Franco, L. S.; Montagnoli, T. L.; Fraga, C. A. M. Molecular hybridization: a powerful tool for multitarget drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2024, 19, 451–470. [CrossRef]

- Peter, S.; Alven, S.; Maseko, R. B.; Aderibigbe, B. A. Doxorubicin-based hybrid compounds as potential anticancer agents: a Review. Molecules. 2022, 27, paper 4478.

- Alam, M. M. 1,2,3-Triazole hybrids as anticancer agents: a review. Arch. Pharm. 2022, 355, paper 2100158. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qian, S.; Wang, S.; Zou, Y. Recent advances on pyrazole-pyrimidine/fused pyrimidine hybrids with anticancer potential (a review). Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2023, 93, 2090–2112.

- Nakypova, S.; Smolobochkin, A.; Rizbayeva, T.; Turmanov, R.; Gazizov, A.; Akylbekov, N.; Zhapparbergenov, R.; Narmanova, R.; Ibadullayeva, S.; Zalaltdinova, A.; Syzdykbayev, M.; Voronina, J.; Lyubina, A.; Voloshina, A.; Klimanova, E.; Sashenkova, T.; Mishchenko, D.; Burilov, A. Taurine-based hybrid drugs as potential anticancer therapeutic agents: in vitro, in vivo evaluations. Pharmaceuticals. 2025, 18, 1056.

- Singh, M.; Kaur, M.; Chadha, N.; Silakari, O. Hybrids: a new paradigm to treat Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Divers. 2016, 20, 271–297. [CrossRef]

- Khudina, O. G.; Grishchenko, M. V.; Makhaeva, G. F.; Kovaleva, N. V.; Boltneva, N. P.; Rudakova, E. V.; Lushchekina, S. V.; Shchegolkov, E. V.; Borisevich, S. S.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I.; Charushin, V. N. Conjugates of amiridine and thiouracil derivatives as effective inhibitors of butyrylcholinesterase with the potential to block β-amyloid aggregation. Arch. Pharm. 2024, 357, paper 2300447.

- Hatami, M.; Basri, Z.; Sakhvidi, B. K.; Mortazavi, M. Thiadiazole – a promising structure in design and development of Anti-Alzheimer agents. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 118, paper 110027.

- Bubley, A.; Erofeev, A.; Gorelkin, P.; Beloglazkina, E.; Majouga, A.; Krasnovskaya, O. Tacrine-based hybrids: past, present, and future. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, paper 1717.

- Makhaeva, G. F.; Kovaleva, N. V.; Rudakova, E. V.; Boltneva, N. P.; Lushchekina, S. V.; Astakhova, T. Y.; Timokhina, E. N.; Serkov, I. V.; Proshin, A. N.; Soldatova, Y. V.; Poletaeva, D. A.; Faingold, I. I.; Mumyatova, V. A.; Terentiev, A. A.; Radchenko, E. V.; Palyulin, V. A.; Bachurin, S. O.; Richardson, R. J. Combining experimental and computational methods to produce conjugates of anticholinesterase and antioxidant pharmacophores with linker chemistries affecting biological activities related to treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Molecules. 2024, 29, paper 321.

- Pathak, C.; Kabra, U. D. A Comprehensive Review of multi-target directed ligands in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 144, paper 107152.

- Litus, E. A.; Shevelyova, M. P.; Vologzhannikova, A. A.; Deryusheva, E. I.; Chaplygina, A. V.; Rastrygina, V. A.; Machulin, A. V.; Alikova, V. D.; Nazipova, A. A.; Permyakova, M. E.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Permyakov, S. E.; Nemashkalova, E. L. Interaction between glucagon-like peptide 1 and its analogs with amyloid-β peptide affects its fibrillation and cytotoxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, paper 4095. [CrossRef]

- Jana, A.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Das, S. S.; Srivastava, A.; Choudhury, A.; Bhattacharjee, R.; De, S.; Perveen, A.; Iqbal, D.; Gupta, P. K.; Jha, S. K.; Ojha, S.; Singh, S. K.; Ruokolainen, J.; Jha, N. K.; Kesari, K. K.; Ashraf, G. M. Molecular insights into therapeutic potentials of hybrid compounds targeting Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 3512–3528.

- Makhaeva, G. F.; Grishchenko, M. V.; Kovaleva, N. V.; Boltneva, N. P.; Rudakova, E. V.; Astakhova, T. Y.; Timokhina, E. N.; Pronkin, P. G.; Lushchekina, S. V.; Khudina, O. G.; Zhilina, E. F.; Shchegolkov, E. V.; Lapshina, M. A.; Dubrovskaya, E. S.; Radchenko, E. V.; Palyulin, V. A.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I.; Charushin, V. N.; Richardson, R. J. Conjugates of amiridine and salicylic derivatives as promising multifunctional CNS agents for potential treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. Arch. Pharm. 2025, 358, paper e2400819.

- Makhaeva, G. F.; Kovaleva, N. V.; Rudakova, E. V.; Boltneva, N. P.; Grishchenko, M. V.; Lushchekina, S. V.; Astakhova, T. Y.; Serebryakova, O. G.; Timokhina, E. N.; Zhilina, E. F.; Shchegolkov, E. V.; Ulitko, M. V.; Radchenko, E. V.; Palyulin, V. A.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I.; Bachurin, S. O.; Richardson, R. J. Conjugates of tacrine and salicylic acid derivatives as new promising multitarget agents for Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, paper 2285. [CrossRef]

- Elkina, N. A.; Grishchenko, M. V.; Shchegolkov, E. V.; Makhaeva, G. F.; Kovaleva, N. V.; Rudakova, E. V.; Boltneva, N. P.; Lushchekina, S. V.; Astakhova, T. Y.; Radchenko, E. V.; Palyulin, V. A.; Zhilina, E. F.; Perminova, A. N.; Lapshin, L. S.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I.; Richardson, R. J. New multifunctional agents for potential Alzheimer’s disease Treatment Based on tacrine conjugates with 2-arylhydrazinylidene-1,3-diketones. Biomolecules. 2022, 12, paper 1551. [CrossRef]

- Grishchenko, M. V.; Makhaeva, G. F.; Burgart, Y. V.; Rudakova, E. V.; Boltneva, N. P.; Kovaleva, N. V.; Serebryakova, O. G.; Lushchekina, S. V.; Astakhova, T. Y.; Zhilina, E. F.; Shchegolkov, E. V.; Richardson, R. J.; Saloutin, V. I. Conjugates of tacrine with salicylamide as promising multitarget agents for Alzheimer's disease. ChemMedChem. 2022, 17, paper e202200080.

- Abdul Rahaman, T. A.; Rajendra, T. N.; Suhas, K. P.; Ippagunta, S. K.; Chaudhary, S. 1,2,4,5-Tetraoxane derivatives/hybrids as potent antimalarial endoperoxides: chronological advancements, structure−activity relationship (SAR) studies and future perspectives. Med. Res. Rev. 2024, 44, 2266–2290.

- Robert, A.; Paloque, L.; Augereau, J. M.; Nardella, F.; Nguyen, M.; Meunier, B.; Benoit-Vical, F. Hybrid Molecules As Efficient drugs against multidrug-resistant malaria parasites. ChemMedChem. 2025, 20, paper e202500086. [CrossRef]

- Peter, S.; Jama, S.; Alven, S.; Aderibigbe, B. A. Artemisinin and derivatives-based hybrid compounds: promising therapeutics for the treatment of cancer and malaria. Molecules. 2021, 26, paper 7521.

- Ferreira, V. F.; Graciano, I. A.; de Carvalho, A. S.; de Carvalho da Silva, F. 1,2,3-Triazole- and quinoline-based hybrids with potent antiplasmodial activity. Med. Chem. 2022, 18, 521–535. [CrossRef]

- Vinindwa, B.; Dziwornu, G. A.; Masamba, W. Synthesis and Evaluation of chalcone-quinoline based molecular hybrids as potential anti-malarial agents. Molecules. 2021, 26, paper 4093.

- Pacheco, P. A. F.; Santos, M. M. M. Recent Progress in the development of indole-based compounds active against malaria, trypanosomiasis and leishmaniasis. Molecules. 2022, 27, paper 319.

- Ravindar, L.; Hasbullah, S. A.; Rakesh, K. P.; Raheem, S.; Ismail, N.; Ling, L. Y.; Hassan, N. I. Pyridine and pyrimidine hybrids as privileged scaffolds in antimalarial drug discovery: a recent development. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 114, paper 129992.

- Mehta, K.; Khambete, M.; Abhyankar, A.; Omri, A. Anti-Tuberculosis Mur Inhibitors: structural insights and the way ahead for development of novel agents. Pharmaceuticals. 2023, 16, 377.

- Hegde, V.; Bhat, R. M.; Budagumpi, S.; Adimule, V.; Keri, R. S. Quinoline hybrid derivatives as effective structural motifs in the treatment of tuberculosis: emphasis on structure-activity relationships. Tuberculosis. 2024, 149, paper 102573.

- Leite, D. I.; de Castro Bazan Moura, S.; da Conceição Avelino Dias, M.; Costa, C. C. P.; Machado, G. P.; Pimentel, L. C. F.; Branco, F. S. C.; Moreira, R.; Bastos, M. M.; Boechat, N. A Review of the development of multitarget molecules against HIV-TB coinfection pathogens. Molecules. 2023, 28, paper 3342.

- Mishra, S.; Kumar, G.; Singh, P. Isoniazid hybrids as potential antitubercular agents. ChemistrySelect. 2024, 9, paper e202402933.

- Owais, M.; Kumar, A.; Hasan, S. M.; Singh, K.; Azad, I.; Hussain, A.; Suvaiv; Akil, M. Quinoline derivatives as promising scaffolds for antitubercular activity: a comprehensive review. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2024, 24, 1238–1251. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, D. S.; Kongot, M.; Kumar, A. Coumarin hybrid derivatives as promising leads to treat tuberculosis: recent developments and critical aspects of structural design to exhibit anti-tubercular activity. Tuberculosis. 2021, 127, paper 102050.

- Montana, M.; Montero, V.; Khoumeri, O.; Vanelle, P. Quinoxaline moiety: a potential scaffold against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Molecules. 2021, 26, paper 4742.

- Alghamdi, S.; Qusty, N. F.; Atwah, B.; Alhindi, Z.; Alatawy, R.; Verma, S.; Asif, M. Isoniazid analogs and their biological activities as antitubercular agents (A Review). Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2024, 94, 2101–2141. [CrossRef]

- Liman, W.; Ait Lahcen, N.; Oubahmane, M.; Hdoufane, I.; Cherqaoui, D.; Daoud, R.; El Allali, A. Hybrid molecules as potential drugs for the treatment of HIV: Design and Applications. Pharmaceuticals. 2022, 15, paper 1092.

- Starosotnikov, A. M.; Bastrakov, M. A. Recent Developments in the Synthesis of HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitors incorporating pyridine moiety. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, paper 9314.

- Chen, Q.; Wu, C.; Zhu, J.; Li, E.; Xu, Z. Therapeutic potential of indole derivatives as Anti-HIV Agents: a Mini-Review. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 993–1008.

- Feng, L. S.; Zheng, M. J.; Zhao, F.; Liu, D. 1,2,3-Triazole hybrids with anti-HIV-1 activity. Arch. Pharm. 2021, 354, paper 2000163.

- Suleiman, M.; Almalki, F. A.; Ben Hadda, T.; Kawsar, S. M. A.; Chander, S.; Murugesan, S.; Bhat, A. R.; Bogoyavlenskiy, A.; Jamalis, J. Recent Progress in Synthesis, POM Analyses and SAR of coumarin-hybrids as potential Anti-HIV Agents—A Mini Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2023, 16, 1538.

- Deng, C.; Yan, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Liu, K.; Shi, Y. The Anti-HIV potential of imidazole, oxazole and thiazole hybrids: a mini-review. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, paper 104242.

- Zhang, L.; Wei, F.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C.; López-Carrobles, N.; Liu, X.; Menéndez-Arias, L.; Zhan, P. Current medicinal chemistry strategies in the discovery of novel HIV-1 ribonuclease h inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 243, paper 114760. [CrossRef]

- Navacchia, M. L.; Cinti, C.; Marchesi, E.; Perrone, D. Insights into SARS-CoV-2: Small-Molecule Hybrids for COVID-19 Treatment. Molecules. 2024, 29, paper 5403.

- Lungu, I. A.; Moldovan, O. L.; Biriș, V.; Rusu, A. Fluoroquinolones hybrid molecules as promising antibacterial agents in the fight against antibacterial resistance. Pharmaceutics. 2022, 14, 1749.

- Belakhov, V. V. Polyfunctional drugs: search, development, use in medical practice, and environmental aspects of preparation and application (A Review). Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2022, 92, 3030–3055.

- Gao, J.; Hou, H.; Gao, F. Current scenario of quinolone hybrids with potential antibacterial activity against ESKAPE Pathogens. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 247, paper 115026.

- Smolobochkin, A.; Gazizov, A.; Appazov, N.; Sinyashin, O.; Burilov, A. Progress in the stereoselective synthesis methods of pyrrolidine-containing drugs and their precursors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, paper 11158. [CrossRef]

- Chugunova, E.; Gibadullina, E.; Matylitsky, K.; Bazarbayev, B.; Neganova, M.; Volcho, K.; Rogachev, A.; Akylbekov, N.; Nguyen, H. B. T.; Voloshina, A.; Lyubina, A.; Amerhanova, S.; Syakaev, V.; Burilov, A.; Appazov, N.; Zhanakov, M.; Kuhn, L.; Sinyashin, O.; Alabugin, I. Diverse biological activity of benzofuroxan/sterically hindered phenols hybrids. Pharmaceuticals. 2023, 16, paper 499.

- Marinescu, M. Benzimidazole-triazole hybrids as antimicrobial and antiviral agents: a systematic review. Antibiotics. 2023, 12, paper 1220.

- Patel, K. B.; Kumari, P. A Review: structure-activity relationship and antibacterial activities of quinoline based hybrids. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1268, paper 133634.

- Volynkina, I. A.; Bychkova, E. N.; Karakchieva, A. O.; Tikhomirov, A. S.; Zatonsky, G. V.; Solovieva, S. E.; Martynov, M. M.; Grammatikova, N. E.; Tereshchenkov, A. G.; Paleskava, A.; Konevega, A. L.; Sergiev, P. V.; Dontsova, O. A.; Osterman, I. A.; Shchekotikhin, A. E.; Tevyashova, A. N. Hybrid molecules of azithromycin with chloramphenicol and metronidazole: synthesis and study of antibacterial properties. Pharmaceuticals. 2024, 17, 187. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. P.; Tu, Y.; Tian, W. Current scenario of pleuromutilin derivatives with antibacterial potential (A Review). Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2023, 93, S908–S927.

- Levshin, I. B.; Simonov, A. Y.; Panov, A. A.; Grammatikova, N. E.; Alexandrov, A. I.; Ghazy, E. S. M. O.; Ivlev, V. A.; Agaphonov, M. O.; Mantsyzov, A. B.; Polshakov, V. I. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a series of new hybrid amide derivatives of triazole and thiazolidine-2,4-dione. Pharmaceuticals. 2024, 17, paper 723.

- Khwaza, V.; Aderibigbe, B. A. Antifungal activities of natural products and their hybrid molecules. Pharmaceutics. 2023, 15, paper 2673. [CrossRef]

- Gharge, S.; Alegaon, S. G. Recent studies of nitrogen and sulfur containing heterocyclic analogues as novel antidiabetic agents: a Review. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 21, paper e202301738.

- Fallah, Z.; Tajbakhsh, M.; Alikhani, M.; Larijani, B.; Faramarzi, M. A.; Hamedifar, H.; Mohammadi-Khanaposhtani, M.; Mahdavi, M. A Review on synthesis, mechanism of action, and structure-activity relationships of 1,2,3-triazole-based α-glucosidase inhibitors as promising anti-diabetic agents. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1255, paper 132469.

- Chawla, G.; Pradhan, T.; Gupta, O. An insight into the combat strategies for the treatment of type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2024, 24, 403–430.

- Sharma, J.; Kaushal, R. Nitrogen Containing Heterocyclic Chalcone Hybrids and Their Biological Potential (A Review). Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2024, 94, 1794–1814. [CrossRef]

- Trifonov, R. E.; Ostrovskii, V. A. Tetrazoles and related heterocycles as promising synthetic antidiabetic agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17190.

- Tretyakova, E.; Smirnova, I.; Kazakova, O.; Nguyen, H. T. T.; Shevchenko, A.; Sokolova, E.; Babkov, D.; Spasov, A. New molecules of diterpene origin with inhibitory properties toward A-Glucosidase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13535. [CrossRef]

- Huneif, M. A.; Mahnashi, M. H.; Jan, M. S.; Shah, M.; Almedhesh, S. A.; Alqahtani, S. M.; Alzahrani, M. J.; Ayaz, M.; Ullah, F.; Rashid, U.; Sadiq, A. New succinimide–thiazolidinedione hybrids as multitarget antidiabetic agents: design, synthesis, bioevaluation, and molecular modelling studies. Molecules. 2023, 28, 1207.

- Mohammad, B. D.; Baig, M. S.; Bhandari, N.; Siddiqui, F. A.; Khan, S. L.; Ahmad, Z.; Khan, F. S.; Tagde, P.; Jeandet, P. Heterocyclic compounds as dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors with special emphasis on oxadiazoles as potent anti-diabetic agents. Molecules. 2022, 27, 6001.

- Farwa, U.; Raza, M. A. Heterocyclic compounds as a magic bullet for diabetes mellitus: a Review. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 22951–22973.

- Khator, R.; Monga, V. Recent advances in the synthesis and medicinal perspective of pyrazole-based α-amylase inhibitors as antidiabetic agents. Future Med. Chem. 2024, 16, 173–195.

- Ramsis, T. M.; Ebrahim, M. A.; Fayed, E. A. Synthetic coumarin derivatives with anticoagulation and antiplatelet aggregation inhibitory effects. Med. Chem. Res. 2023, 32, 2269–2278.

- Spasov, A. A.; Fedorova, O. V.; Rasputin, N. A.; Ovchinnikova, I. G.; Ishmetova, R. I.; Ignatenko, N. K.; Gorbunov, E. B.; Sadykhov, G. A.; Kucheryavenko, A. F.; Gaidukova, K. A.; Sirotenko, V. S.; Rusinov, G. L.; Verbitskiy, E. V.; Charushin, V. N. Novel substituted azoloazines with anticoagulant activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, paper 15581.

- Bhagat, P. P.; Bansode, T. N. Coumarin derivatives: pioneering new frontiers in biological applications. Curr. Org. Chem. 2025, 29, 794–813. [CrossRef]

- Skoptsova, A. A.; Geronikaki, A.; Novichikhina, N. P.; Sulimov, A. V.; Ilin, I. S.; Sulimov, V. B.; Bykov, G. A.; Podoplelova, N. A.; Pyankov, O. V.; Shikhaliev, K. S. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of new hybrid derivatives of 5,6-dihydro-4h-pyrrolo[3,2,1-ij]quinolin-2(1H)-one as potential dual inhibitors of blood coagulation factors Xa and XIa. Molecules. 2024, 29, 373.

- Kouznetsov, V. V. Exploring acetaminophen prodrugs and hybrids: a Review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 9691–9715. [CrossRef]

- Laev, S. S.; Salakhutdinov, N. F. New small-molecule analgesics. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 6234–6273.

- Belyaeva, E. R.; Myasoedova, Y. V.; Ishmuratova, N. M.; Ishmuratov, G. Y. Synthesis and biological activity of N-Acylhydrazones. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 48, 1123–1150.

- Cheremnykh, K.; Bryzgalov, A.; Baev, D.; Borisov, S.; Sotnikova, Y.; Savelyev, V.; Tolstikova, T.; Sagdullaev, S.; Shults, E. Synthesis, pharmacological evaluation, and molecular modeling of lappaconitine–1,5-benzodiazepine hybrids. Molecules. 2023, 28, paper 4234. [CrossRef]

- Zayed, M. F. Medicinal chemistry of quinazolines as analgesic and anti-inflammatory agents. ChemEngineering. 2022, 6, paper 94.

- Baramaki, I.; Altıntop, M. D.; Arslan, R.; Alyu Altınok, F.; Özdemir, A.; Dallali, I.; Hasan, A.; Bektaş Türkmen, N. Design, synthesis, and in vivo evaluation of a new series of indole-chalcone hybrids as analgesic and anti-inflammatory agents. ACS Omega. 2024, 9, 12175–12183.

- Ryazantsev, M. N.; Strashkov, D. M.; Nikolaev, D. M.; Shtyrov, A. A.; Panov, M. S. Photopharmacological compounds based on azobenzenes and azoheteroarenes: principles of molecular design, molecular modelling, and synthesis. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2021, 90, 868–893.

- da Cruz, R. M. D.; Mendonça-Junior, F. J. B.; de Mélo, N. B.; Scotti, L.; de Araújo, R. S. A.; de Almeida, R. N.; de Moura, R. O. Thiophene-based compounds with potential anti-inflammatory activity. Pharmaceuticals. 2021, 14, 692.

- Ahmadi, M.; Bekeschus, S.; Weltmann, K. D.; von Woedtke, T.; Wende, K. Non-Steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: recent advances in the use of synthetic COX-2 inhibitors. RSC Med. Chem. 2022, 13, 471–496.

- Bian, M.; Ma, Q.; Wu, Y.; Du, H.; Guo-hua, G. Small molecule compounds with good anti-inflammatory activity reported in the literature from 01/2009 to 05/2021: a Review. J. Enzyme Inhib. Medicinal Chem. 2021, 36, 2139–2159.

- Wu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yao, C.; Zhan, J.; Wu, P.; Han, Z.; Zuo, J.; Feng, H.; Qian, Z. Recent advances in small-molecule fluorescent photoswitches with photochromism in diverse states. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2023, 11, 15393–15411.

- Khuzin, A. A.; Tuktarov, A. R.; Venidiktova, O. V.; Barachevsky, V. A.; Mullagaliev, I. N.; Salikhov, T. R.; Salikhov, R. B.; Khalilov, L. M.; Khuzina, L. L.; Dzhemilev, U. M. Hybrid molecules based on fullerene C60 and dithienylethenes. synthesis and photochromic properties. optically controlled organic field-effect transistors. Photochem. Photobiol. 2022, 98, 815–822.

- Khuzin, A. A.; Galimov, D. I.; Khuzina, L. L. Photochromic and luminescent properties of a salt of a hybrid molecule based on C60 fullerene and spiropyran—a promising approach to the creation of anticancer drugs. Molecules. 2023, 28, 1107.

- Stoikov, I. I.; Antipin, I. S.; Burilov, V. A.; Kurbangalieva, A. R.; Rostovskii, N. V.; Pankova, A. S.; Balova, I. A.; Remizov, Y. O.; Pevzner, L. M.; Petrov, M. L.; Vasilyev, A. V.; Averin, A. D.; Beletskaya, I. P.; Nenajdenko, V. G.; Beloglazkina, E. K.; Gromov, S. P.; Karlov, S. S.; Magdesieva, T. V.; Prishchenko, A. A.; Popkov, S. V.; Terent’ev, A. O.; Tsaplin, G. V.; Kustova, T. P.; Kochetova, L. B.; Magdalinova, N. A.; Krasnokutskaya, E. A.; Nyuchev, A. V.; Kuznetsova, Y. L.; Fedorov, A. Y.; Egorova, A. Y.; Grinev, V. S.; Sorokin, V. V.; Ovchinnikov, K. L.; Kofanov, E. R.; Kolobov, A. V.; Rusinov, V. L.; Zyryanov, G. V.; Nosov, E. V.; Bakulev, V. A.; Belskaya, N. P.; Berezkina, T. V.; Obydennov, D. L.; Sosnovskikh, V. Y.; Bakhtin, S. G.; Baranova, O. V.; Doroshkevich, V. S.; Raskildina, G. Z.; Sultanova, R. M.; Zlotskii, S. S.; Dyachenko, V. D.; Dyachenko, I. V.; Fisyuk, A. S.; Konshin, V. V.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Ivleva, E. A.; Reznikov, A. N.; Klimochkin, Y. N.; Aksenov, D. A.; Aksenov, N. A.; Aksenov, A. V.; Burmistrov, V. V.; Butov, G. M.; Novakov, I. A.; Shikhaliev, K. S.; Stolpovskaya, N. V.; Medvedev, S. M.; Kandalintseva, N. V.; Prosenko, O. I.; Menshchikova, E. B.; Golovanov, A. A.; Khashirova, S. Y. Organic Chemistry in Russian Universities. Achievements of Recent Years. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 60, 1361–1584.

- Charushin, V. N.; Verbitskiy, E. V.; Chupakhin, O. N.; Vorobyeva, D. V.; Gribanov, P. S.; Osipov, S. N.; Ivanov, A. V.; Martynovskaya, S. V.; Sagitova, E. F.; Dyachenko, V. D.; Dyachenko, I. V.; Krivokolylsko, S. G.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Aksenov, A. V.; Aksenov, D. A.; Aksenov, N. A.; Larin, A. A.; Fershtat, L. L.; Muzalevskiy, V. M.; Nenajdenko, V. G.; Gulevskaya, A. V.; Pozharskii, A. F.; Filatova, E. A.; Belyaeva, K. V.; Trofimov, B. A.; Balova, I. A.; Danilkina, N. A.; Govdi, A. I.; Tikhomirov, A. S.; Shchekotikhin, A. E.; Novikov, M. S.; Rostovskii, N. V.; Khlebnikov, A. F.; Klimochkin, Y. N.; Leonova, M. V.; Tkachenko, I. M.; Mamedov, V. A. O.; Mamedova, V. L.; Zhukova, N. A.; Semenov, V. E.; Sinyashin, O. G.; Borshchev, O. V.; Luponosov, Y. N.; Ponomarenko, S. A.; Fisyuk, A. S.; Kostyuchenko, A. S.; Ilkin, V. G.; Beryozkina, T. V.; Bakulev, V. A.; Gazizov, A. S.; Zagidullin, A. A.; Karasik, A. A.; Kukushkin, M. E.; Beloglazkina, E. K.; Golantsov, N. E.; Festa, A. A.; Voskresenskii, L. G.; Moshkin, V. S.; Buev, E. M.; Sosnovskikh, V. Y.; Mironova, I. A.; Postnikov, P. S.; Zhdankin, V. V.; Yusubov, M. S. O.; Yaremenko, I. A.; Vil', V. A.; Krylov, I. B.; Terent'ev, A. O.; Gorbunova, Y. G.; Martynov, A. G.; Tsivadze, A. Y.; Stuzhin, P. A.; Ivanova, S. S.; Koifman, O. I.; Burov, O. N.; Kletskii, M. E.; Kurbatov, S. V.; Yarovaya, O. I.; Volcho, K. P.; Salakhutdinov, N. F.; Panova, M. A.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I.; Sitdikova, A. R.; Shchegravina, E. S.; Fedorov, A. Y. The chemistry of heterocycles in the 21st Century. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2024, 93, RCR5125.

- Larin, A. A.; Fershtat, L. L. Energetic Heterocyclic N-Oxides: synthesis and performance. Mendeleev Commun. 2022, 32, 703–713. [CrossRef]

- Shaferov, A. V.; Ananyev, I. V.; Monogarov, K. A.; Fomenkov, I. V.; Pivkina, A. N.; Fershtat, L. L. Energetic methylene-bridged furoxan-triazole/tetrazole hybrids. ChemPlusChem. 2024, 89, e202400496.

- Muravyev, N. V.; Fershtat, L.; Zhang, Q. Synthesis, design and development of energetic materials: quo vadis?. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 486, 150410.

- Dotsenko, V. V.; Frolov, K. A.; Krivokolysko, S. G. Synthesis of partially hydrogenated 1,3,5-thiadiazines by Mannich reaction. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2015, 51, 109–127.

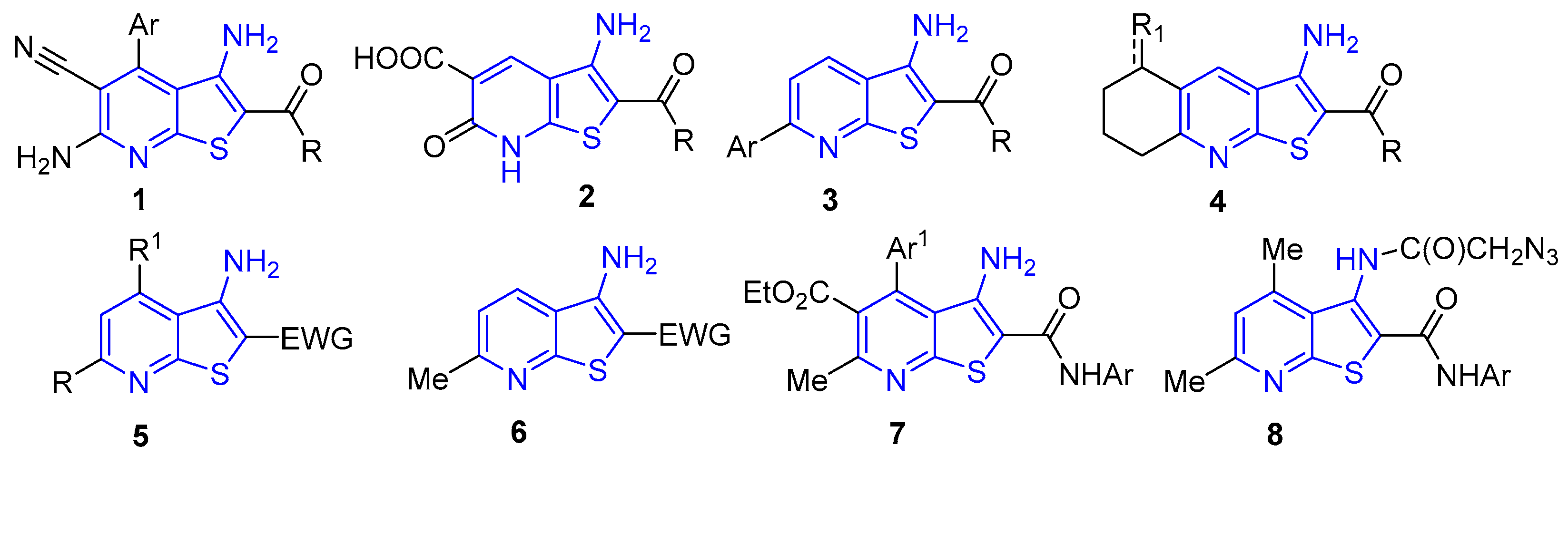

- Dotsenko, V. V.; Buryi, D. S.; Lukina, D. Y.; Krivokolysko, S. G. Recent advances in the chemistry of thieno[2,3-b]pyridines. 1. Methods of synthesis of thieno[2,3-b]pyridines. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2020, 69, 1829–1858.

- Dotsenko, V. V.; Frolov, K. A.; Chigorina, E. A.; Khrustaleva, A. N.; Bibik, E. Y.; Krivokolysko, S. G. New possibilities of the Mannich reaction in the synthesis of N-, S,N-, and Se,N-Heterocycles. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2019, 68, 691–707.

- Stroganova, T. A.; Vasilin, V. K.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Aksenov, N. A.; Morozov, P. G.; Vassiliev, P. M.; Volynkin, V. A.; Krapivin, G. D. Unusual oxidative dimerization in the 3-aminothieno[2,3-b]pyridine-2-carboxamide series. ACS Omega. 2021, 6, 14030–14048.

- Dotsenko, V. V.; Muraviev, V. S.; Lukina, D. Y.; Strelkov, V. D.; Aksenov, N. A.; Aksenova, I. V.; Krapivin, G. D.; Dyadyuchenko, L. V. Reaction of 3-amino-4,6-diarylthieno[2,3-b]pyridine-2-carboxamides with ninhydrin. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2020, 90, 948–960. [CrossRef]

- Dotsenko, V. V.; Lukina, D. Y.; Buryi, D. S.; Strelkov, V. D.; Aksenov, N. A.; Aksenova, I. V. Synthesis of new polycyclic compounds containing thieno[2′,3′:5,6]pyrimido[2,1-a]isoindole fragment. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2021, 91, 1292–1296.

- Dotsenko, V. V.; Rudenko, S. V.; Lukina, D. Y.; Smirnova, A. K.; Krivokolysko, S. G.; Temerdashev, A. Z.; Harutyunyan, A. S.; Paronikyan, E. G.; Aksenov, N. A.; Aksenova, I. V. Synthesis of 2,2-dimethyl-2,3-dihydropyrido[3′,2′: 4,5]thieno[3,2-d]pyrimidin-4(1H)-ones by reaction of 3-aminothieno[2,3-b]pyridine- 2-carboxamides with acetone. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2025, 95, 1236–1247.

- Pakholka, N. A.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Churakov, A. V.; Krivokolysko, S. G. Synthesis, Structure, and bromination of 3-(arylamino)-2-(4-arylthiazol-2-yl)acrylonitriles. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2025, 95, 1210–1224.

- Dotsenko, V. V.; Bespalov, A. V.; Sinotsko, A. E.; Temerdashev, A. Z.; Vasilin, V. K.; Varzieva, E. A.; Strelkov, V. D.; Aksenov, N. A.; Aksenova, I. V. 6-Amino-4-aryl-7-phenyl-3-(phenylimino)-4,7-dihydro-3H-[1,2]dithiolo[3,4-b]pyridine-5-carboxamides: synthesis, biological activity, quantum chemical studies and in silico docking studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 769. [CrossRef]

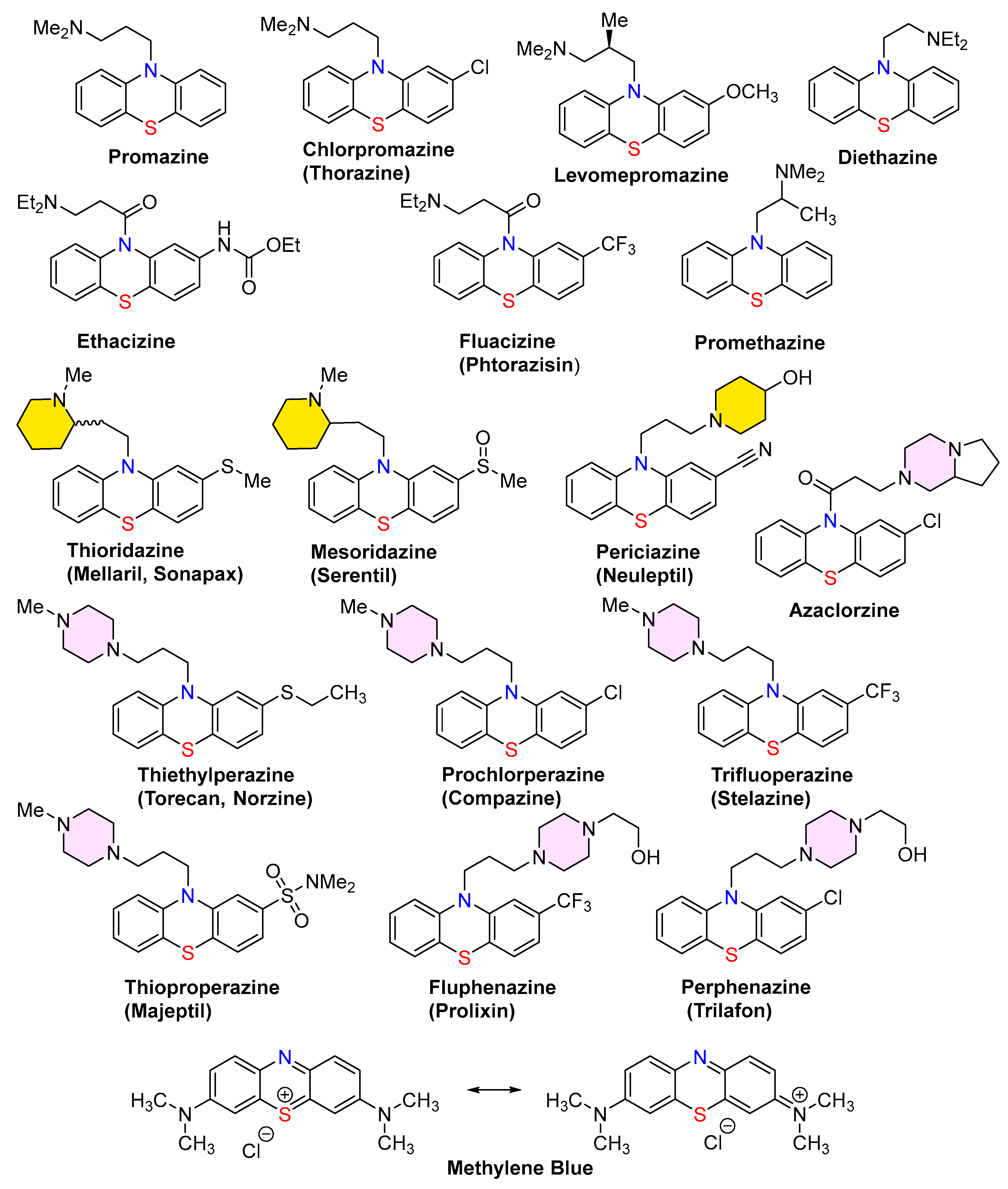

- Mosnaim, A. D.; Ranade, V. V.; Wolf, M. E.; Puente, J.; Antonieta Valenzuela, M. Phenothiazine molecule provides the basic chemical structure for various classes of pharmacotherapeutic agents. Am. J. Ther. 2006, 13, 261–273.

- Ohlow, M. J.; Moosmann, B. Phenothiazine: the seven lives of pharmacology's first lead structure. Drug Discov. Today. 2011, 16, 119–131.

- Zaharia, C. A. Phenothiazine-based dopamine D2 antagonists for the treatment of schizophrenia (Chapter 5). In Bioactive Heterocyclic Compound Classes: Pharmaceuticals, 1st Edition Dinges, J., Lamberth, C., Eds. Wiley: Hoboken, New Jersey, U.S., 2012, pp. 65–79.

- Wainwright, M. The development of phenothiazinium photosensitisers. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2005, 2, 263–272. [CrossRef]

- Medina, D. X.; Caccamo, A.; Oddo, S. Methylene Blue reduces aβ levels and rescues early cognitive deficit by increasing proteasome activity. Brain Pathol. 2011, 21, 140–149.

- Padnya, P. L.; Khadieva, A. I.; Stoikov, I. I. Current achievements and perspectives in synthesis and applications of 3,7-disubstituted phenothiazines as Methylene Blue analogues. Dyes Pigments. 2023, 208, 110806.

- Oz, M.; Lorke, D. E.; Petroianu, G. A. Methylene Blue and Alzheimer's Disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2009, 78, 927–932.

- Seitkazina, A.; Yang, J. K.; Kim, S. Clinical effectiveness and prospects of Methylene Blue: a Systematic Review. Precis. Future Medicine. 2022, 6, 193–208.

- Taldaev, A.; Terekhov, R.; Nikitin, I.; Melnik, E.; Kuzina, V.; Klochko, M.; Reshetov, I.; Shiryaev, A.; Loschenov, V.; Ramenskaya, G. Methylene Blue in anticancer photodynamic therapy: systematic review of preclinical studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, paper 1264961. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Vigato, C.; Boschi, D.; Lolli, M. L.; Kumar, D. Phenothiazines as anti-cancer agents: SAR Overview and Synthetic Strategies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 254, paper 115337.

- González-González, A.; Vazquez-Jimenez, L. K.; Paz-González, A. D.; Bolognesi, M. L.; Rivera, G. Recent advances in the medicinal chemistry of phenothiazines, new anticancer and antiprotozoal agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 7910–7936.

- Babalola, B. A.; Malik, M.; Sharma, L.; Olowokere, O.; Folajimi, O. Exploring the therapeutic potential of phenothiazine derivatives in medicinal chemistry. Results Chem. 2024, 8, 101565.

- Voronova, O.; Zhuravkov, S.; Korotkova, E.; Artamonov, A.; Plotnikov, E. Antioxidant properties of new phenothiazine derivatives. Antioxidants. 2022, 11, paper 1371.

- El-Sedik, M. S.; Mohamed, M. B. I.; Abdel-Aziz, M. S.; Aysha, T. S. Synthesis of New D–Π–A phenothiazine-based fluorescent dyes: aggregation induced emission and antibacterial activity. J. Fluoresc. 2024, 35, 3119–3130.

- Khan, F.; Misra, R. Recent advances in the development of phenothiazine and its fluorescent derivatives for optoelectronic applications. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2023, 11, 2786–2825.

- Xu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M. X. Asymmetric Phenothiazine derivatives modified with diphenylamine and carbazole: photophysical properties and hypochlorite sensing. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 340, paper 126346. [CrossRef]

- Ilakiyalakshmi, M.; Dhanasekaran, K.; Napoleon, A. A. A Review on recent development of phenothiazine-based chromogenic and fluorogenic sensors for the detection of cations, anions, and neutral analytes. Top. Curr. Chem. 2024, 382, article number 29.

- Ilakiyalakshmi, M.; Arumugam Napoleon, A. Phenothiazine-derived fluorescent chemosensor: a versatile platform enabling swift cyanide ion detection and its multifaceted utility in paper strips, environmental water, food samples and living cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2024, 447, 115213.

- Li, Y.; Zhou, C.; Li, J.; Sun, J. A New phenothiazine-based fluorescent sensor for detection of cyanide. Biosensors. 2024, 14, 51.

- Serkov, I. V.; Proshin, A. N.; Ustinov, A. K.; Bachurin, S. O. Phenothiazine derivatives containing a NO-generating fragment. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2022, 71, 2757–2760.

- Malanina, A. N.; Kuzin, Y. I.; Padnya, P. L.; Ivanov, A. N.; Stoikov, I. I.; Evtugyn, G. A. Cationic and anionic phenothiazine derivatives: electrochemical behavior and application in DNA sensor development. Analyst. 2025, 150, 2087–2100.

- Kononov, A. I.; Strekalova, S. O.; Budnikova, Y. H. Electrochemical and photochemical functionalization of phenothiazines towards the synthesis of N-Aryl phenothiazines: recent updates and prospects. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 28, e202401472.

- Dumur, F. Recent advances on visible light phenothiazine-based photoinitiators of polymerization. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 165, 110999.

- Hölter, N.; Rendel, N. H.; Spierling, L.; Kwiatkowski, A.; Kleinmans, R.; Daniliuc, C. G.; Wenger, O. S.; Glorius, F. Phenothiazine sulfoxides as active photocatalysts for the synthesis of γ-lactones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 12908–12916. [CrossRef]

- Posso, M. C.; Domingues, F. C.; Ferreira, S.; Silvestre, S. Development of phenothiazine hybrids with potential medicinal interest: a Review. Molecules. 2022, 27, paper 276.

- Bachurin, S. O.; Shevtsova, E. F.; Makhaeva, G. F.; Aksinenko, A. Y.; Grigoriev, V. V.; Goreva, T. V.; Epishina, T. A.; Kovaleva, N. V.; Boltneva, N. P.; Lushchekina, S. V.; Rudakova, E. V.; Vinogradova, D. V.; Shevtsov, P. N.; Pushkareva, E. A.; Dubova, L. G.; Serkova, T. P.; Veselov, I. M.; Fisenko, V. P.; Richardson, R. J. Conjugates of Methylene Blue With cycloalkaneindoles as new multifunctional agents for potential treatment of neurodegenerative disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13925. [CrossRef]

- Kisla, M. M.; Yaman, M.; Zengin-Karadayi, F.; Korkmaz, B.; Bayazeid, O.; Kumar, A.; Peravali, R.; Gunes, D.; Tiryaki, R. S.; Gelinci, E.; Cakan-Akdogan, G.; Ates-Alagoz, Z.; Konu, O. Synthesis and structure of novel phenothiazine derivatives, and compound prioritization via in silico target search and screening for cytotoxic and cholinesterase modulatory activities in liver cancer cells and in Vivo in Zebrafish. ACS Omega. 2024, 9, 30594–30614.

- Gorecki, L.; Uliassi, E.; Bartolini, M.; Janockova, J.; Hrabinova, M.; Hepnarova, V.; Prchal, L.; Muckova, L.; Pejchal, J.; Karasova, J. Z.; Mezeiova, E.; Benkova, M.; Kobrlova, T.; Soukup, O.; Petralla, S.; Monti, B.; Korabecny, J.; Bolognesi, M. L. Phenothiazine-tacrine heterodimers: pursuing multitarget directed approach in Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 1698–1715.

- Carocci, A.; Barbarossa, A.; Leuci, R.; Carrieri, A.; Brunetti, L.; Laghezza, A.; Catto, M.; Limongelli, F.; Chaves, S.; Tortorella, P.; Altomare, C. D.; Santos, M. A.; Loiodice, F.; Piemontese, L. Novel phenothiazine/donepezil-like hybrids endowed with antioxidant activity for a multi-target approach to the therapy of Alzheimer’s disease. Antioxidants. 2022, 11, 1631.

- Spivak, A. Y.; Nedopekina, D. A.; Davletshin, E. V.; Khalitova, R. R. Efficient and practical synthesis of a novel lipophilic phenothiazine derivative with an α-tocopherol isoprenoid side chain. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2025, 95, 1494–1500. [CrossRef]

- Cibotaru, S.; Sandu, A. I.; Nicolescu, A.; Marin, L. Antitumor activity of PEGylated and TEGylated phenothiazine derivatives: Structure–Activity Relationship. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5449.

- Iniyaval, S.; Saravanan, V.; Mai, C. W.; Ramalingan, C. Tetrazolopyrimidine-tethered phenothiazine molecular hybrids: synthesis, biological and molecular docking studies. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 13384–13396. [CrossRef]

- Doddagaddavalli, M. A.; Bhat, S. S.; Seetharamappa, J. Characterization, crystal structure, anticancer and antioxidant activity of novel N-(2-oxo-2-(10H-phenothiazin-10-yl) ethyl)piperidine-1-carboxamide. J. Struct. Chem. 2023, 64, 131–141.

- Sarhan, M. O.; Haffez, H.; Elsayed, N. A.; El-Haggar, R. S.; Zaghary, W. A. New phenothiazine conjugates as apoptosis inducing agents: design, synthesis, in-vitro anti-cancer screening and 131I-radiolabeling for in-vivo evaluation. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 141, 106924.

- Litvinov, V.P. The chemistry of 3-cyanopyridine-2 (1H)-chalcogenones. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2006, 75, 577–599.

- Litvinov, V.P. Partially hydrogenated pyridinechalcogenones. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1998, 47, 2053–2073.

- Litvinov, V.P.; Krivokolysko, S.G., Dyachenko, V.D. Synthesis and properties of 3-cyanopyridine-2(1H)-chalcogenones. Review. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1999, 35, 509–540.

- Gouda, M.A.; Berghot, M.A.; Abd El Ghani, G.E.; Khalil, A.E.G.M. Chemistry of 2-amino-3-cyanopyridines. Synth. Commun. 2014, 44, 297–330.

- Salem, M.A.; Helel, M.H.; Gouda, M.A.; Ammar, Y.A.; El-Gaby, M.S.A. Overview on the synthetic routes to nicotine nitriles. Synth. Commun. 2018, 48, 345–374.

- Gouda, M.A.; Hussein, B.H.; Helal, M.H.; Salem, M.A. A Review: Synthesis and medicinal importance of nicotinonitriles and their analogous. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2018, 55, 1524–1553.

- Gouda, M.A.; Attia, E.; Helal, M.H.; Salem, M.A. Recent progress on nicotinonitrile scaffold-based anticancer, antitumor, and antimicrobial agents: A literature review. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2018, 55, 2224–2250. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.; Hisham, M.; Osman, M.; Hayallah, A. Nicotinonitrile as an essential scaffold in medicinal chemistry: an updated review. J. Adv. Biomed. & Pharm. Sci. 2023, 6, 1–11.

- Anwer, K. E.; Sayed, G. H. Synthesis and reactions of 2-amino-3-cyanopyridine derivatives (A Review). Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 60, 2170–2227. [CrossRef]

- Khlus, A. V.; Egorov, D. M. Synthetic approaches to 2-aminopyridine-3-carbonitriles (A Review). Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 61, 195–211.

- Mekky, A. E. M.; Sanad, S. M. H. [3+2] Cycloaddition Synthesis of new (nicotinonitrile-chromene)-based bis(pyrazole) hybrids as potential acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2023, 60, 156–160. [CrossRef]

- Ashmawy, F. O.; Gomha, S. M.; Abdallah, M. A.; Zaki, M. E. A.; Al-Hussain, S. A.; El-desouky, M. A. Synthesis, in vitro evaluation and molecular docking studies of novel thiophenyl thiazolyl-pyridine hybrids as potential anticancer agents. Molecules. 2023, 28, 4270.

- Ali, S. S.; Nafie, M. S.; Farag, H. A.; Amer, A. M. Anticancer potential of nicotinonitrile derivatives as PIM-1 kinase inhibitors through apoptosis: in vitro and in vivo studies. Med. Chem. Res. 2025, 34, 1074–1088.

- Bardasov, I. N.; Ievlev, M. Y.; Chunikhin, S. S.; Alekseeva, A. U.; Ershov, O. V. Synthesis and photophysical properties of novel nicotinonitrile-based chromophores of 1,4-diarylbuta-1,3-diene series. Dyes Pigments. 2023, 217, 111432.

- Ketova, E. S.; Myazina, A. V.; Bibik, E. Y.; Krivokolysko, S. G. New compounds with a dihydropyridine framework as promising hypolipidemic and hepatoprotective agents. Res. Results Pharmacol. 2024, 10, 61–71.

- Tilchenko, D. A.; Bibik, E. Y.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Krivokolysko, S. G.; Frolov, K. A.; Aksenov, N. A.; Aksenova, I. V. Synthesis and hypoglycemic activity of new nicotinonitrile-furan molecular hybrids. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 50, 554–570.

- Dotsenko, V. V.; Krivokolysko, B. S.; Bibik, E. Y.; Frolov, K. A.; Aksenov, N. A.; Aksenova, I. V.; Krivokolysko, S. G. Synthesis and in vivo evaluation of hepatoprotective effects of novel sulfur-containing 1,4-dihydropyridines and 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyridines. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 2023, 19, e171022210054.

- Krivokolysko, D. S.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Bibik, E. Y.; Samokish, A. A.; Venidiktova, Y. S.; Frolov, K. A.; Krivokolysko, S. G.; Vasilin, V. K.; Pankov, A. A.; Aksenov, N. A.; Aksenova, I. V. New 4-(2-furyl)-1,4-dihydronicotinonitriles and 1,4,5,6-tetrahydronicotinonitriles: synthesis, structure, and analgesic activity. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2021, 91, 1646–1660. [CrossRef]

- Krivokolysko, D. S.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Bibik, E. Y.; Myazina, A. V.; Krivokolysko, S. G.; Vasilin, V. K.; Pankov, A. A.; Aksenov, N. A.; Aksenova, I. V. Synthesis, structure, and analgesic activity of 4-(5-cyano-{4-(fur-2-yl)-1,4- dihydropyridin-3-yl}carboxamido)benzoic acids ethyl esters. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2021, 91, 2588–2605. [CrossRef]

- Krivokolysko, D. S.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Bibik, E. Y.; Samokish, A. A.; Venidiktova, Y. S.; Frolov, K. A.; Krivokolysko, S. G.; Pankov, A. A.; Aksenov, N. A.; Aksenova, I. V. New hybrid molecules based on sulfur-containing nicotinonitriles: synthesis, analgesic activity in acetic acid-induced writhing test, and molecular docking studies. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 48, 628–635.

- Bibik, I. V.; Bibik, E. Y.; Pankov, A. A.; Frolov, K. A.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Krivokolysko, S. G. Study of anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive properties of new derivatives of condensed 3-aminothieno[2,3-b]pyridines and 1,4-dihydropyridines. Acta Biomed. Sci. 2023, 8, 220–233.

- Dotsenko, V. V.; Jassim, N. T.; Temerdashev, A. Z.; Abdul-Hussein, Z. R.; Aksenov, N. A.; Aksenova, I. V. New 6′-amino-5′-cyano-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1′H-spiro[indole-3,4′-pyridine]-3′-carboxamides: synthesis, reactions, molecular docking studies and biological activity. Molecules. 2023, 28, 3161.

- Dyadyuchenko, L. V.; Dmitrieva, I. G.; Aksenov, N. A.; Dotsenko, V. V. Synthesis, structure, and biological activity of 2,6-diazido-4-methylnicotinonitrile derivatives. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2018, 54, 964–970. [CrossRef]

- Al-Wahaibi, L. H.; Abou-Zied, H. A.; Hisham, M.; Beshr, E. A. M.; Youssif, B. G. M.; Bräse, S.; Hayallah, A. M.; Abdel-Aziz, M. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel 3-cyanopyridone/pyrazoline hybrids as potential apoptotic antiproliferative agents targeting EGFR/BRAFV600E inhibitory pathways. Molecules. 2023, 28, 6586.

- Litvinov, V. P.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Krivokolysko, S. G. Thienopyridines: synthesis, properties, and biological activity. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2005, 54, 864–904.

- Litvinov, V. P.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Krivokolysko, S. G. The chemistry of thienopyridines. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 2007, 93, 117–178.

- El-Sayed, H. A. Heterocyclization of ethyl 3-amino-4,6-dimethylthieno[2,3-b]pyridine-2-carboxylate (Review). J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2014, 11, 131–145. [CrossRef]

- Salem, M. A.; Abu-Hashem, A. A.; Abdelgawad, A. A. M.; Gouda, M. A. Synthesis and reactivity of thieno[2,3-b]quinoline derivatives (part II). J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2021, 58, 1705–1740.

- Shaw, R.; Tewari, R.; Yadav, M.; Pandey, E.; Tripathi, K.; Rani, J.; Althagafi, I.; Pratap, R. Recent advancements in the synthesis of fused thienopyridines and their therapeutic applications. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2024, 12, 100185.

- Anighoro, A.; Pinzi, L.; Marverti, G.; Bajorath, J.; Rastelli, G. Heat Shock Protein 90 and Serine/Threonine Kinase B-Raf Inhibitors have overlapping chemical space. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 31069–31074.

- Masch, A.; Kunick, C. Selective Inhibitors of Plasmodium Falciparum Glycogen Synthase-3 (PfGSK-3): new antimalarial agents? Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Proteins Proteom. 2015, 1854, 1644–1649.

- Schweda, S. I.; Alder, A.; Gilberger, T.; Kunick, C. 4-Arylthieno[2,3-b]pyridine-2-carboxamides are a new class of antiplasmodial agents. Molecules. 2020, 25, 3187.

- Masch, A.; Nasereddin, A.; Alder, A.; Bird, M. J.; Schweda, S. I.; Preu, L.; Doerig, C.; Dzikowski, R.; Gilberger, T. W.; Kunick, C. Structure–Activity Relationships in a series of antiplasmodial thieno[2,3-b]pyridines. Malar. J. 2019, 18, paper 89.

- Fugel, W.; Oberholzer, A. E.; Gschloessl, B.; Dzikowski, R.; Pressburger, N.; Preu, L.; Pearl, L. H.; Baratte, B.; Ratin, M.; Okun, I.; Doerig, C.; Kruggel, S.; Lemcke, T.; Meijer, L.; Kunick, C. 3,6-Diamino-4-(2- halophenyl)-2-benzoylthieno[2,3-b]pyridine-5-carbonitriles are selective inhibitors of Plasmodium Falciparum glycogen synthase kinase-3. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 264–275.

- Nkomba, G.; Terre’Blanche, G.; Janse van Rensburg, H. D.; Legoabe, L. J. Design, synthesis and evaluation of amino-3,5-dicyanopyridines and thieno[2,3-b]pyridines as ligands of adenosine A1 Receptors for the potential treatment of epilepsy. Med. Chem. Res. 2022, 31, 1277–1297.

- Betti, M.; Catarzi, D.; Varano, F.; Falsini, M.; Varani, K.; Vincenzi, F.; Dal Ben, D.; Lambertucci, C.; Colotta, V. The aminopyridine-3,5-dicarbonitrile core for the design of new non-nucleoside-like agonists of the human adenosine A2B Receptor. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 150, 127–139.

- Dotsenko, V. V.; Krivokolysko, S. G.; Chernega, A. N.; Litvinov, V. P. Anilinomethylidene derivatives of cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the synthesis of new sulfur-containing pyridines and quinolines. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2002, 51, 1556–1561.

- Dayam, R.; Al-Mawsawi, L. Q.; Zawahir, Z.; Witvrouw, M.; Debyser, Z.; Neamati, N. Quinolone 3-Carboxylic Acid Pharmacophore: Design of Second Generation HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 1136–1144.

- Nagarajan, S.; Doddareddy, M.; Choo, H.; Cho, Y. S.; Oh, K. S.; Lee, B. H.; Pae, A. N. IKKβ Inhibitors Identification Part I: Homology Model Assisted Structure Based Virtual Screening. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 2759–2766.

- Mermerian, A. H.; Case, A.; Stein, R. L.; Cuny, G. D. Structure–Activity relationship, kinetic mechanism, and selectivity for a new class of ubiquitin c-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 3729–3732.

- Sorci, L.; Pan, Y.; Eyobo, Y.; Rodionova, I.; Huang, N.; Kurnasov, O.; Zhong, S.; MacKerell, A. D.; Zhang, H.; Osterman, A. L. Targeting NAD biosynthesis in bacterial pathogens: structure-based development of inhibitors of nicotinate mononucleotide adenylyltransferase NadD. Chem. Biol. 2009, 16, 849–861.

- Xu, Y.; Zheng, R.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, F.; Lin, H.; Bu, Q.; Mao, Y.; Yu, L.; Yang, L.; Yang, S.; Zhao, Y. Small molecular anticancer agent SKLB703 induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells via the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in vitro and inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2011, 313, 44–53. [CrossRef]

- Nikkhoo, A. R.; Miri, R.; Arianpour, N.; Firuzi, O.; Ebadi, A.; Salarian, A. A. Cytotoxic activity assessment and C-Src Tyrosine kinase docking simulation of thieno[2,3-b] pyridine-based derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2014, 23, 1225–1233.

- Leung, E.; Hung, J. M.; Barker, D.; Reynisson, J. The effect of a thieno[2,3-b]pyridine PLC-γ inhibitor on the proliferation, morphology, migration and cell cycle of breast cancer cells. Med. Chem. Commun. 2013, 5, 99–106.

- Arabshahi, H. J.; Leung, E.; Barker, D.; Reynisson, J. The development of thieno[2,3-b]pyridine analogues as anticancer agents applying in silico methods. MedChemComm. 2014, 5, 186.

- Zafar, A.; Pilkington, L.; Haverkate, N.; van Rensburg, M.; Leung, E.; Kumara, S.; Denny, W.; Barker, D.; Alsuraifi, A.; Hoskins, C.; Reynisson, J. Investigation into improving the aqueous solubility of the thieno[2,3-b]pyridine anti-proliferative agents. Molecules. 2018, 23, 145.

- Arabshahi, H. J.; van Rensburg, M.; Pilkington, L. I.; Jeon, C. Y.; Song, M.; Gridel, L. M.; Leung, E.; Barker, D.; Vuica-Ross, M.; Volcho, K. P.; Zakharenko, A. L.; Lavrik, O. I.; Reynisson, J. A Synthesis, in silico, in vitro and in vivo study of thieno[2,3-b]pyridine anticancer analogues. MedChemComm. 2015, 6, 1987–1997.

- Binsaleh, N. K.; Wigley, C. A.; Whitehead, K. A.; van Rensburg, M.; Reynisson, J.; Pilkington, L. I.; Barker, D.; Jones, S.; Dempsey-Hibbert, N. C. Thieno[2,3-b]pyridine derivatives are potent anti-platelet drugs, inhibiting platelet activation, aggregation and showing synergy with aspirin. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 1997–2004. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. P.; Fleck, R.; Brickwood, J.; Capolino, A.; Catron, K.; Chen, Z.; Cywin, C.; Emeigh, J.; Foerst, M.; Ginn, J.; Hrapchak, M.; Hickey, E.; Hao, M. H.; Kashem, M.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; Morwick, T.; Nelson, R.; Marshall, D.; Martin, L.; Nemoto, P.; Potocki, I.; Liuzzi, M.; Peet, G. W.; Scouten, E.; Stefany, D.; Turner, M.; Weldon, S.; Zimmitti, C.; Spero, D.; Kelly, T. A. The discovery of thienopyridine analogues as potent IκB kinase β inhibitors. Part II. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 5547–5551.

- Mekky, A. E. M.; Sanad, S. M. H.; Said, A. Y.; Elneairy, M. A. A. Synthesis, cytotoxicity, in-vitro antibacterial screening and in-silico study of novel thieno[2,3-b]pyridines as potential pim-1 inhibitors. Synth. Commun. 2020, 50, 2376–2389.

- Laudette, M.; Coluccia, A.; Sainte-Marie, Y.; Solari, A.; Fazal, L.; Sicard, P.; Silvestri, R.; Mialet-Perez, J.; Pons, S.; Ghaleh, B.; Blondeau, J. P.; Lezoualc’h, F. Identification of a pharmacological inhibitor of Epac1 that protects the heart against acute and chronic models of cardiac stress. Cardiovasc. Res. 2019, 115, 1766–1777.

- Li, X. D.; Liu, L.; Cheng, L. Identification of thienopyridine carboxamides as selective binders of HIV-1 trans activation response (TAR) and Rev Response Element (RRE) RNAs. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 9191–9196.

- Bakhite, E. A.; Gad, M. A.; Khamies, E.; Thagfan, F. A.; Mohamed, R. A. E. H.; Bakry, M. M. S. Exploration of some thieno[2,3-b]pyridines, thieno[3,2-d]pyrimidinones, and thieno[3,2-d][1,2,3]triazinones as insecticidal agents against Aonidiella Aurantii. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2025, 51, 816–826.

- Dotsenko, V.V.; Buryi, D.S.; Lukina, D.Y.; Stolyarova, A.N.; Aksenov, N.A.; Aksenova, I.V.; Strelkov, V.D.; Dyadyuchenko, L.V. Substituted N-(thieno[2,3-b]pyridine-3-yl)acetamides: Synthesis, reactions, and biological activity. Monatsh. Chem. 2019, 150, 1973–1985.

- Sanad, S. M. H.; Mekky, A. E. M. Ultrasound-mediated synthesis of new (piperazine-chromene)-linked bis(thieno[2,3-b]pyridine) hybrids as potential anti-acetylcholinesterase. ChemistrySelect. 2022, 7, e202203020.

- Alenazi, N. A.; Alharbi, H.; Fawzi Qarah, A.; Alsoliemy, A.; Abualnaja, M. M.; Karkashan, A.; Abbas, B.; El-Metwaly, N. M. New thieno[2,3-b]pyridine-based compounds: synthesis, molecular modelling, antibacterial and antifungal activities. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 105226. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Mu, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Shen, C.; Mu, Q.; Feng, B.; Xu, Y.; Hou, T.; Gao, L.; Jiang, H.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, W. Novel Thieno[2,3-b]quinoline-procaine hybrid molecules: a new class of allosteric SHP-1 activators evolved from PTP1B Inhibitors. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 108063. [CrossRef]

- Dyachenko, V. D.; Dyachenko, I. V.; Nenajdenko, V. G. Cyanothioacetamide: a polyfunctional reagent with broad synthetic utility. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2018, 87, 1.

- Sharanin, Yu. A.; Rodinovskaya, L. A.; Litvinov, V. P.; Promonenkov, V. K.; Mortikov, V. Yu.; Shestopalov, A. M. Reactions of arylidenecyanothioacetamides with carbonyl compounds and their enamines. J. Org. Chem. USSR (Engl. Transl.), 1985, 21, 619–620.

- Sharanin, Y. A.; Litvinov, V. P.; Shestopalov, A. M.; Nesterov, V. N.; Struchkov, Y. T.; Shklover, V. E.; Promonenkov, V. K.; Mortikov, V. Y. Structure of 4-amino-6-phenyl-5-cyano-2-cyclohexanespiro-1,3-dithia-4-cyclohexene and its recyclization to 5,6-tetramethylene-4-phenyl-3-cyano-2[1H]Pyridinethione. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR Div. Chem. Sci. 1985, 34, 1619–1625. [CrossRef]

- Litvinov, V. P.; Promonenkov, V. K.; Sharanin, Y. A.; Shestopalov, A. M.; Rodinovskaya, L. A.; Mortikov, V. Y.; Bogdanov, V. S. Condensed pyridines communication 3. Arylidenethio(seleno)acetamides in the synthesis of 4-aryl-3-cyano- 2[1H]pyridinethiones and 4-aryl-3-cyano-2[1H]pyridineselenones. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR Div. Chem. Sci. 1985, 34, 1940–1947.

- Kindop, V. K.; Bespalov, A. V.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Strelkov, V. D.; Lukina, D. Yu.; Baichurin, R. I.; Paronikyan, E. G.; Harutyunyan, A. S.; Ovcharov, S. N.; Aksenov N. A.; Aksenova, I. V. Synthesis and structural characterization of 2-iminothiazoline/quinoline and 2-iminothiazoline/thieno[2,3-b]quinoline molecular hybrids with herbicide safening properties. Tetrahedron, 2025, 134889.

- Narushyavichus, É. V.; Garalene, V. N.; Krauze, A. A.; Dubur, G. Ya. Cardiotropic activity of pyridin-2(1H)-ones. Pharm. Chem. J. 1989, 23, 983–986.

- Frolova, N. G.; Zav'yalova, V. K.; Litvinov, V. P. Synthesis of 4,5,6-trisubstituted 3-cyanopyridine-2(1H)-thiones based on α-substituted β-diketones. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1996, 45, 2578–2580.

- Hussain, B. A.; Attia, A. M.; Elgemeie, G. E. H. Synthesis of N-glycosylated pyridiines as new antimetabolite agents. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1999, 18, 2335–2343.

- Rodinovskaya, L. A.; Belukhina, E. V.; Shestopalov, A. M.; Litvinov, V. P. Regioselective synthesis of 5,6-polymethylene-3-cyanopyridine-2(1H)-thiones and fused heterocycles based on them. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1994, 43, 449–457. [CrossRef]

- Marcu, A.; Schurigt, U.; Müller, K.; Moll, H.; Krauth-Siegel, R. L.; Prinz, H. Inhibitory effect of phenothiazine- and phenoxazine-derived chloroacetamides on Leishmania Major growth and Trypanosoma Brucei trypanothione reductase. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 108, 436–443.

- Khelwati, H.; van Geelen, L.; Kalscheuer, R.; Müller, T. J. J. Synthesis, electronic, and antibacterial properties of 3,7-di(hetero)aryl-substituted phenothiazinyl N-propyl trimethylammonium salts. Molecules 2024, 29, paper 2126.

- Nizi, M. G.; Desantis, J.; Nakatani, Y.; Massari, S.; Mazzarella, M. A.; Shetye, G.; Sabatini, S.; Barreca, M. L.; Manfroni, G.; Felicetti, T.; Rushton-Green, R.; Hards, K.; Latacz, G.; Satała, G.; Bojarski, A. J.; Cecchetti, V.; Kolář, M. H.; Handzlik, J.; Cook, G. M.; Franzblau, S. G.; Tabarrini, O. Antitubercular polyhalogenated phenothiazines and phenoselenazine with reduced binding to CNS Receptors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 201, 112420.

- Kindop, Vl. K.; Kindop, V. K.; Dotsenko, V. V. ; Lukina, D. Yu.; Aksenov, N. А.; Aksenova, I. V. The unexpected result of the Thorpe-Ziegler heterocyclization of N-[(3-cyanoquinolin-2-yl)thio]acetylphenothiazines promoted by KOH–CH3OH. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2025, accepted.

- Gruner, M.; Rehwald, M.; Eckert, K.; Gewald, K. New syntheses of 2-alkylthio-4-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinazolines, 2-alkylthio- quinazolines, as well as their hetero analogues. Heterocycles 2000, 53, 2363-2377. [CrossRef]

- Zaki, R. M.; Kamal El-Dean, A. M.; Radwan, S. M.; Ammar, M. A. Efficient synthesis, reactions and anti-inflammatory evaluation of novel cyclopenta[d]thieno[2,3-b]pyridines and their related heterocycles. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 48, S121–S135.

- Zaki, R. M.; Radwan, S. M.; El-Dean, A. M. K. Synthesis and reactions of 1-amino-5-morpholin-4-yl- 6,7,8,9-tetrahydrothieno[2,3-c]isoquinoline. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2011, 58, 544–554.

- El-Mariah, F. Thieno[2,3-c]pyridazine derivatives: synthesis and antimicrobial activity. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2008, 183, 2795–2806.

- Regal, M. K. A.; Rafat, E. H.; El-Sattar, N. E. A. A. Synthesis, characterization, and dyeing performance of some azo thienopyridine and thienopyrimidine dyes based on wool and nylon. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2020, 57, 1173–1182. [CrossRef]

- Abu El-Azm, F. S. M.; Ali, A. T.; Hekal, M. H. Facile synthesis and anticancer activity of novel 4-aminothieno[2,3-d]pyrimidines and triazolothienopyrimidines. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 2019, 51, 507–520.

- Saravanan, G.; Selvaraju, R.; Nagarajan, S. Synthesis of novel 2-iminothiazolidin-4-ones. Synth. Commun. 2012, 42, 3361–3367.

- Tikhonov, D. S.; Gordiy, I.; Iakovlev, D. A.; Gorislav, A. A.; Kalinin, M. A.; Nikolenko, S. A.; Malaskeevich, K. M.; Yureva, K.; Matsokin, N. A.; Schnell, M. Harmonic scale factors of fundamental transitions for dispersion-corrected quantum chemical methods. ChemPhysChem. 2024, 25, e202400547.

- Lipinski, C. A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today: Technol. 2004, 1, 337–341. [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C. A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B. W.; Feeney, P. J. Experimental and Computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 4–17.

- Sander, T. OSIRIS Property Explorer. Avail. URL: http://www.organic-chemistry.org/prog/peo/. Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Switzerland.

- Gu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Lou, C.; Yang, C.; Li, W.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y. AdmetSAR3.0: a comprehensive platform for exploration, prediction and optimization of chemical ADMET properties. Nucl. Acids Res. 2024, 52, W432–W438.

- GalaxyWEB. Avail. URL: http://galaxy.seoklab.org/index.html. A web server for protein structure prediction, refinement, and related methods. Computational Biology Lab, Department of Chemistry, Seoul National University, S. Korea.

- Yang, J.; Kwon, S.; Bae, S. H.; Park, K. M.; Yoon, C.; Lee, J. H.; Seok, C. GalaxySagittarius: structure- and similarity-based prediction of protein targets for druglike compounds. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 3246–3254.

- Pettersen, E. F.; Goddard, T. D.; Huang, C. C.; Couch, G. S.; Greenblatt, D. M.; Meng, E. C.; Ferrin, T. E. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [CrossRef]

- UCSF Chimera. Available URL: https://www.rbvi.ucsf.edu/chimera/. Visualization system for exploratory research and analysis developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, US.

- Dotsenko, V. V.; Krivokolysko, S. G.; Polovinko, V. V.; Litvinov, V. P. On the regioselectivity of the reaction of cyanothioacetamide with 2-acetylcyclohexanone, 2-acetylcyclopentanone, and 2-acetyl-1-(morpholin-4-yl)-1-cycloalkenes. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2012, 48, 309–319.

- Sharanin, Yu. A.; Shestopalov, A. M.; Promonenkov, V. K.; Rodinovskaya, L. A. Cyclization of nitriles. X. Enamino nitriles of the 1,3-dithia-4-cyclohexene series and their recyclization to derivatives of pyridine and thiazole. J. Org. Chem. USSR (Engl. Transl.), 1984, 20, 1402-1415.

- Dolomanov, O. V.; Bourhis, L. J.; Gildea, R. J.; Howard, J. A. K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341.

- Sheldrick, G. M. A Short History of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A. 2008, 64, 112–122. [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G. M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C. 2015, 71, 3–8.

- Neese, F. The ORCA Program System. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 1. 73–78.

- Neese, F. Software Update: the ORCA Program System—Version 6.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2025, 15, e70019. [CrossRef]

- Becke, A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A. 2002, 38, 3098–3100.

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 2002, 37, 785–789.

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A Consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104.

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and Assessment of Accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297. [CrossRef]

- de Souza, B. GOAT: a Global Optimization Algorithm for molecules and atomic clusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202500393.

- Bannwarth, C.; Ehlert, S.; Grimme, S. GFN2-XTB—An Accurate and broadly parametrized self-consistent tight-binding quantum chemical method with multipole electrostatics and density-dependent dispersion contributions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 1652–1671. [CrossRef]

|

|

| Vibrations | Experimental bands, cm-1 | Calculated vibrational frequencies, сm-1 | |

| No correction factors | With correction factors* | ||

| ν N-H | 3294 | 3503 | 3388 |

| ν C-H(Ar) | 3063 | 3196 | 3091 |

| νas CH3 | 2978 | 3113 | 3011 |

| νs CH3 | 2935 | 3037 | 2938 |

| ν C=O thiazolidinone | 1720 | 1805 | 1746 |

| ν C=O (amide I) | 1659 | 1701 | 1665 |

| ν C=N | 1624 | 1672 | 1637 |

| ν C-C(Ar) ThPy | 1585 | 1622 | 1588 |

| ν C-C(Ar) ThPy | 1555 | 1596 | 1562 |

| ν C-C(Ar) ThPy | 1524 | 1558 | 1525 |

| ν C-C(Ar) + δ C-H(Ar) PhTz | 1458 | 1502 | 1470 |

| ν C-N + δ CH3 | 1396 | 1423 | 1393 |

| skeletal | 1331 | 1367 | 1338 |

| skeletal | 1261 | 1299 | 1272 |

| skeletal | 1211 | 1233 | 1207 |

| δ N-H + δ C-H(Ar) | 1126 | 1169 | 1144 |

| δ C-H(Ar) | 1030 | 1060 | 1038 |

| skeletal | 918 | 938 | 918 |

| skeletal | 895 | 907 | 888 |

| ν C-S PhTz | 868 | 878 | 860 |

| δ N-H | 787 | 795 | 778 |

| δ C-H(Ar) | 764 | 777 | 761 |

| skeletal | 725 | 738 | 723 |

| skeletal | 613 | 633 | 620 |

| МАPЕ**, % | - | 2.83 | 0.77 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).