1. Introduction

Hydroxychloroquine, originally an anti-malarial drug, is a cornerstone disease-modifying therapy for rheumatic and autoimmune conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren’s syndrome, and mixed connective tissue disease, thanks to its diverse immunomodulatory effects [

1]. Antimalarial drugs, including HCQ and its analogues, are well established for treating rheumatic, cardiovascular, and dermatological disorders, and emerging evidence suggests they may also have therapeutic potential in infectious diseases and oncology [

2]. HCQ exerts pleiotropic, multi-step effects on both innate and adaptive immunity, modulating autoimmunity while largely preserving the body’s ability to combat pathogens [

3]. Hydroxychloroquine has been shown to inhibit the complement cascade, a key contributor to autoimmune disease pathogenesis. In a Japanese cohort of SLE patients treated with HCQ for 12 months, complement levels increased, with effects becoming evident around three months after therapy initiation [

4]. Quinine derivatives Chloroquine and

Hydroxychloroquine belong to the 4-aminoquinolones family [

5]. According to several studies, HCQ exhibits antiviral activity by disrupting multiple stages of viral replication, including blocking viral interaction with host cell receptors and preventing viral entry [

6]. Some studies about HCQ effect on SARS-CoV-2, suggest that HCQ acts by binding to the gangliosides and sialic acids, which are very important for the virus to enter to the cell [

7]. With the outbreaking of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, it was hypothesized that HCQ or its analogues had an important effect on the treatment and prophylaxis of the disease, because of its in-vitro anti-viral effects [

8,

9].

Moreover, HCQ is an inexpensive and well-tolerated drug with a long history of effective use in malaria and autoimmune diseases [

8,

10]. In vitro, it has demonstrated a synergistic effect with azithromycin [

11]; however, due to conflicting evidence regarding its impact on COVID-19 mortality, HCQ is not recommended in standard treatment guidelines for SARS-CoV-2. According to European League against Rheumatism (EULAR) recomendations, patients with rheumatic diseases should continue their therapy as always during the pandemic. We began to gather evidence of SARS-COV-2 infection in patients who were taking HCQ for their rheumatic disease but also, we were alerted about new infections in a part of healthcare personnel who took HCQ in prophylactic doses voluntarily.

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective case-control study included patients with rheumatic diseases—rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjogren’s syndrome (SS), and mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD)—taking therapeutic doses of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), and healthy individuals, mainly healthcare personnel exposed to SARS-CoV-2, who initiated low-dose HCQ prophylaxis. The study ran from 25 February 2020, two weeks before Albania’s first COVID-19 cases, to 25 March 2021, coinciding with the start of mass vaccination. All participants underwent SARS-CoV-2 PCR and serology testing.

Study Location: Rheumatology Clinic, Internal Medicine, and Infectious Diseases Departments, University Hospital Centre “Mother Teresa,” Tirana, Albania and Internal Medicine Department, Korça Regional Hospital, Albania.

Sample Size: 222 participants (145 cases, 77 controls). The sample size was calculated using a single-proportion design from a target population of 20,000, assuming a 95% confidence level and 10% confidence interval.

Subjects & Selection: Consecutive rheumatic patients attending the Rheumatology Clinic were enrolled, all on HCQ (200–400 mg/day) and PCR-negative at baseline. The control group included 77 healthy volunteers on HCQ 400 mg/week for COVID-19 prophylaxis.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants of this research. All patients included in this study had accepted the informed consent given from the research group.

The included population consisted of:

1. Group I (the cases): 145 patients. 102 females and 43 males. Rheumatic disease distribution was as follows:

- -

Rheumatoid Arthritis: 55 patients (HCQ 200mg/day)

- -

SLE: 32 patients (HCQ 400mg/day)

- -

Sjogren’s: 31 patients (HCQ 200-400mg/day)

- -

MCTD: 27 patients (HCQ 200-400mg/day)

2. Group II (the controls): 77 healthy individuals: 37 females and 40 males (HCQ 400mg/week).

Inclusion criteria:

Rheumatoid arthritis patients.

Sjogren’s syndrome patients.

MCTD patients.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus patients.

Aged ≥ 18 years.

All patients should have been taking hydroxychloroquine for their rheumatic condition.

All patients should be negative on PCR testing for COVID-19 and COVID-19 naïve at the beginning of the study.

As for the control group, all individuals should have commenced voluntarily the HCQ prophylaxis.

Exclusion criteria:

Pregnant women.

Patients who had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 infection before.

Patients younger than 18 years old.

Patients not taking HCQ.

Patients that for any reason had to stop HCQ were excluded from the study.

Patients that resulted in PCR positive for COVID-19 at the beginning of the study.

After written informed consent was obtained, a well-designed questionnaire was used to collect the data of the recruited patients retrospectively. The questionnaire included sociodemographic characteristics such as age, sex, diagnosis. PCR analysis for SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 serology was performed on all the included individuals every 3 months

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

The doses of Hydroxychloroquine were as follow:

Group I

- -

Rheumatoid Arthritis: 55 patients (HCQ 200mg/day)

- -

SLE: 32 patients (HCQ 400mg/day)

- -

Sjogren’s: 31 patients (HCQ 200-400mg/day)

- -

MCTD: 27 patients (HCQ 200-400mg/day)

Group II

- -

35 healthy individuals (including 4 authors of this study) (HCQ 400mg/week).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection between patients with autoimmune diseases on therapeutic doses of hydroxychloroquine and the control group on prophylactic doses was compared using the Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and the strength of association was expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

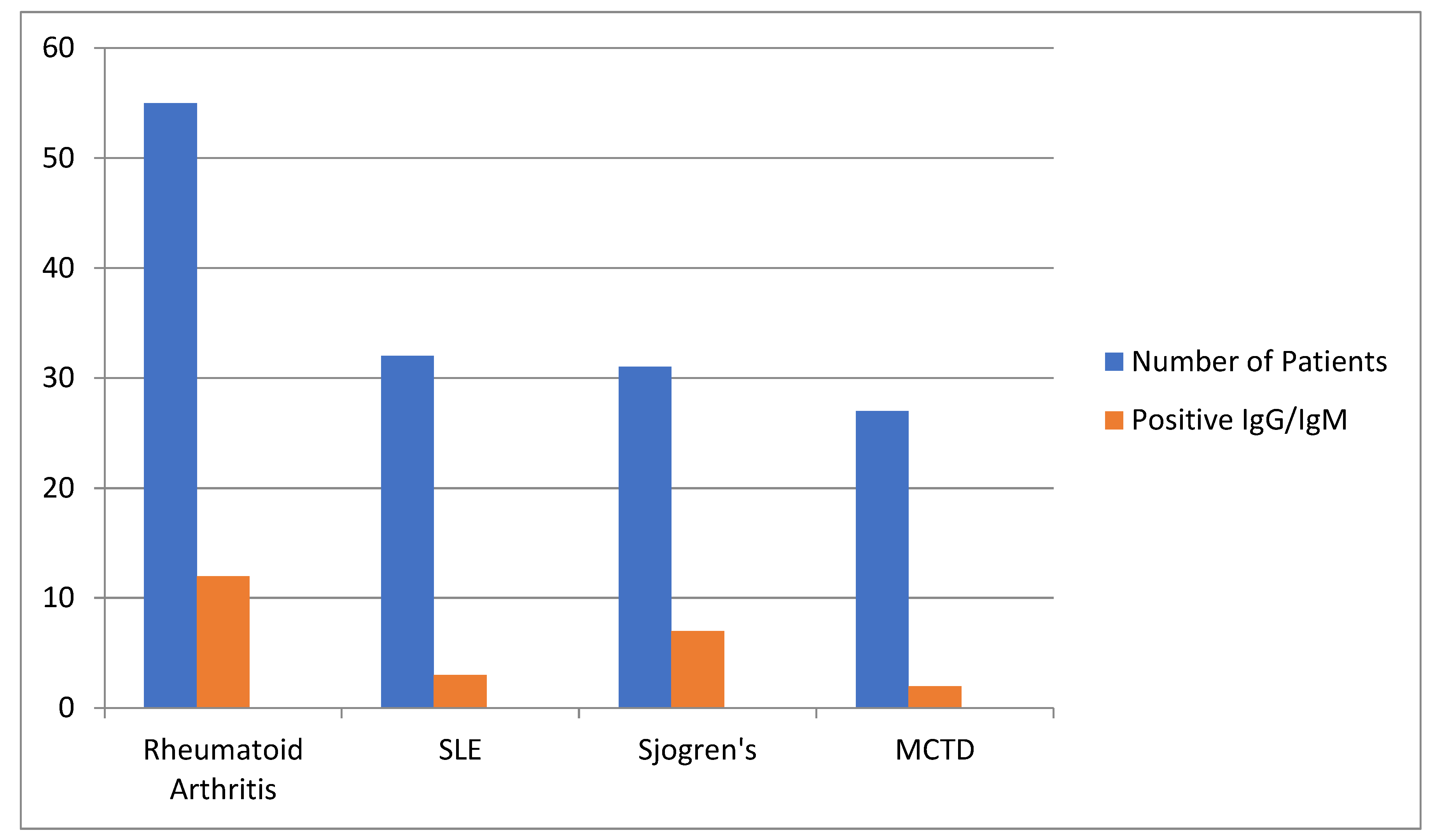

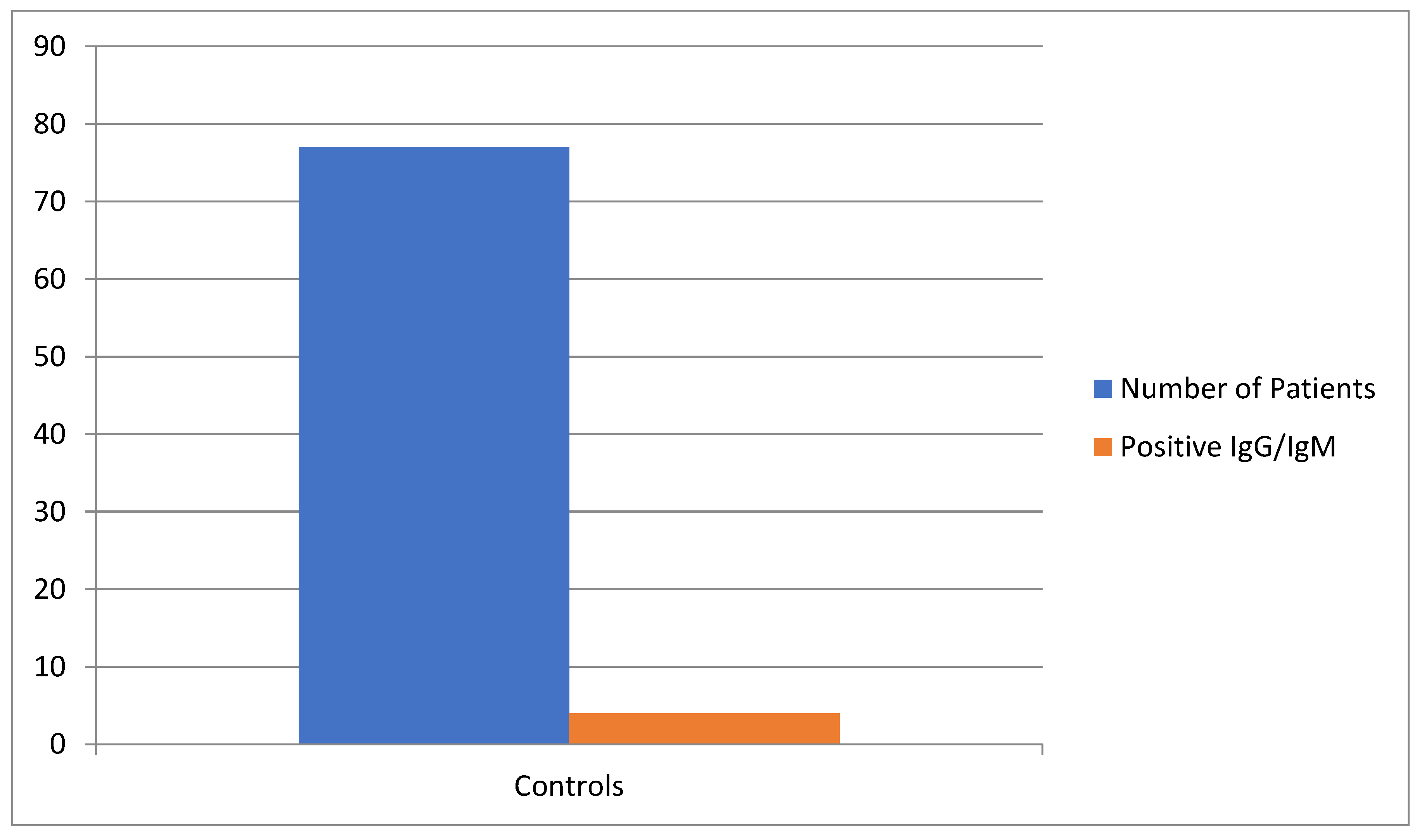

222 individuals were included in this prospective study. The first group (case group) consisted in 145 patients with rheumatic diseases on HCQ, while in the other group (the control group), 77 were healthy volunteer individuals which have begun HCQ as a prophylactic way against COVID- 19. After gathering all data, it was observed that for the first group, positivity rate for IgG/IgM for COVID-19 was 24 individuals (16.5%), while for the control group, it was seen a positivity rate of 4 individuals (5.2%).

When observing the course of the COVID-19 in positive cases, it was seen that in patients with autoimmune diseases on HCQ, pulmonary implications were present only in 4 patients (16.6%). None of the cases needed hospitalization and recovered with no complications. Even in the control group, it was seen a good prognosis of COVID-19 in COVID-19 positive individuals, with no fatalities nor hospitalizations.

When both groups were compared, it was seen a significant difference between 2 groups regarding COVID-19 positivity (p=0.01), making the control group more protected against COVID-19, even though they were on low dosage of HCQ.

Table 1.

Distribution of cases according to autoimmune pathology and positive case distribution.

Table 1.

Distribution of cases according to autoimmune pathology and positive case distribution.

| |

Rheumatoid Arthritis |

SLE |

Sjogren’s |

MCTD |

Total |

| Number of Patients |

55 |

32 |

31 |

27 |

145 |

| Positive IgG/IgM |

12 |

3 |

7 |

2 |

24 |

| Percentage (%) |

21.8 |

9.4 |

22.6 |

7.4 |

16.5 |

Chart 1.

The distribution of autoimmune diseases and positive IgG/IgM cases.

Chart 1.

The distribution of autoimmune diseases and positive IgG/IgM cases.

Chart 2.

Distribution of controls with positive IgG/IgM.

Chart 2.

Distribution of controls with positive IgG/IgM.

Table 2.

Distribution of controls with positive IgG/IgM.

Table 2.

Distribution of controls with positive IgG/IgM.

| |

Controls |

| Number of Patients |

77 |

| Positive IgG/IgM |

4 |

| Percentage (%) |

5.2% |

Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 incidence between groups showed a statistically significant difference:

These results suggest that patients with autoimmune diseases on HCQ had higher odds of SARS-CoV-2 positivity compared to healthy controls on prophylactic HCQ.

Table 3.

Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 positivity between rheumatic patients on HCQ and controls.

Table 3.

Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 positivity between rheumatic patients on HCQ and controls.

| Group |

Total |

Positive |

Negative |

% Positive |

| Rheumatic patients (cases) |

145 |

24 |

121 |

16.6% |

| Healthy controls |

77 |

4 |

73 |

5.2% |

All SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals experienced mild symptoms. Among cases, only 4 patients (16.6% of positives) had mild pulmonary involvement. No hospitalizations or fatalities occurred in either group.

4. Discussion

Since early 2020, the world has faced the COVID-19 pandemic, caused by SARS-CoV-2, which by June 2022 had resulted in over 542 million cases and 6.32 million confirmed deaths worldwide, making it one of the deadliest infectious diseases in history [

12]. Initially, leading infectious disease experts recommended prophylactic use of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin for COVID-19. However, regulatory agencies such as the FDA and EMA later cautioned against this use due to potential additive adverse effects, including cardiac arrhythmias, particularly in patients with heart conditions. These warnings did not affect the drug’s established indications for malaria and autoimmune diseases [

13].

We aimed to evaluate the impact of hydroxychloroquine on COVID-19 morbidity and disease progression in patients with autoimmune conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, and mixed connective tissue disease. In parallel, some healthcare personnel voluntarily took a moderate prophylactic dose of HCQ (400 mg/week). After approximately one year of follow-up, COVID-19 morbidity in both autoimmune patients on HCQ and the control group was lower than expected.

Hydroxychloroquine is a disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug with proven benefits in treating autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, mixed connective tissue disease, and Sjogren’s syndrome. Some studies have shown that HCQ positively modulates the complement cascade in SLE patients [

4]. Notably, in patients with active long COVID-19, complement dysregulation persists and does not fully return to normal function [

14].

In our study, with a total of 222 participants, we observed a statistically significant difference in SARS-CoV-2 incidence between patients with autoimmune diseases on therapeutic HCQ and healthy controls on prophylactic HCQ. Specifically, 16.6% of rheumatic patients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 compared with 5.2% of controls (p = 0.027, Fisher’s exact test p = 0.018), corresponding to an odds ratio of approximately 3.62. These findings suggested that, although HCQ is widely used in autoimmune diseases, its prophylactic use at lower doses in healthy individuals may confer a relative protective effect against COVID-19. Importantly, all positive cases in both groups experienced mild disease with no hospitalizations, supporting the overall safety of HCQ in these populations. While these results do not establish causality, they highlight the potential relevance of dosage and underlying health status in evaluating HCQ’s role in SARS-CoV-2 infection, and they reinforce the need for larger, multicenter, randomized studies to confirm these observations. According to current literature, there is controversy on treatment and safety of HCQ in COVID-19 patients, most of the studies have not shown any relevance [

15], but they were non-randomized and with preliminary results [

16].

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the sample size, particularly in the control group, was relatively small, which may have limited the statistical power to detect differences between groups. Second, the study design was observational and non-randomized, making it susceptible to potential selection bias and unmeasured confounding factors. Third, patients with autoimmune diseases may inherently differ from healthy controls in terms of immune status, comorbidities, and concurrent medications, which could have influenced the incidence and course of SARS-CoV-2 infection independently of hydroxychloroquine use. Fourth, adverse events were assessed based on clinical reporting rather than systematic monitoring, so mild or subclinical events may have been underreported. Finally, the study was conducted prior to the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants and widespread vaccination, limiting the generalizability of our findings to the current phase of the pandemic. Although our study has shown an important role of Hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 prophylaxis in patients with autoimmune diseases and in healthy individuals too, a multi-centred, randomized clinical trial is needed to prove its importance to the question.

While these limitations should be considered, the study also offers several notable strengths. It was conducted prospectively over more than a year, covering the critical pre-vaccination phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. All participants underwent systematic PCR and serological testing, which reduced the risk of underdiagnosis of asymptomatic or mild cases. The inclusion of both patients with autoimmune diseases receiving therapeutic doses of hydroxychloroquine and healthy controls on prophylactic low-dose regimens allowed for a direct comparison of these two populations. Furthermore, adherence to treatment was closely monitored, and no significant adverse effects were reported, strengthening the reliability of the safety data. Finally, this study provides real-world evidence from a unique clinical setting, adding valuable insights to the ongoing debate regarding the prophylactic role of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19.

5. Conclusions

Therapeutic hydroxychloroquine in patients with autoimmune diseases did not appear to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection as effectively as low-dose prophylactic use in healthy controls. Nevertheless, disease manifestations were mild in both groups. The pleiotropic effects of HCQ may still offer potential benefits in COVID-19 prevention. In our cohort, adverse effects were insignificant, supporting the overall safety of HCQ at both therapeutic and prophylactic doses. Interestingly, the relatively greater protection observed with low-dose prophylactic use may reflect underlying immune dysregulation in autoimmune patients rather than differences in HCQ efficacy.

6. Key Messages

Hydroxychloroquine is safe in both therapeutic and prophylactic settings, with no significant adverse effects observed in our study.

Low-dose prophylactic HCQ appeared to offer relatively greater protection against SARS-CoV-2 compared to therapeutic use in autoimmune patients.

The reduced effectiveness in autoimmune patients may be influenced by underlying immune dysregulation rather than the drug itself.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Mikel Jordhani, Petraq Jordhani and Tritan Kalo; methodology, Mikel Jordhani, Dorina Ruci, Petraq Jordhani.; software, Mikel Jordhani.; validation, Tritan Kalo, Dorina Ruci and Petraq Jordhani.; formal analysis, Mikel Jordhani.; investigation, Mikel Jordhani.; resources, Tritan Kalo; data curation, Mikel Jordhani.; writing—original draft preparation, Mikel Jordhani.; writing—review and editing, Mikel Jordhani.; visualization, Mikel Jordhani.; supervision, Petraq Jordhani, Tritan Kalo, Dorina Ruci.; project administration, Mikel Jordhani.; funding acquisition, Petraq Jordhani. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by the Institutional Review Board of University Hospital Center ‘Mother Teresa,’ as the study was observational, and no intervention beyond routine care was performed.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HCQ |

Hydroxychloquine |

| RA |

Rheumatoid Arthritis |

| SLE |

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus |

| SS |

Sjogren’s Syndrome |

| MCTD |

Mixed Connective Tissue Disease |

| PCR |

Protein Chain Reaction |

References

- Schreiber K, Sciascia S, Wehrmann F, Weiß C, Leipe J, Krämer BK, Stach K. The effect of hydroxychloroquine on platelet activation in model experiments. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021 Aug;52(2):674-679. Epub 2021 Jan 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla AM, Wagle Shukla A. Expanding horizons for clinical applications of chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and related structural analogues. Drugs Context. 2019 Nov 25;8:2019-9-1. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fox RI. Mechanism of action of hydroxychloroquine as an antirheumatic drug. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1993;23(2 Suppl 1):82–91.

- Ikeda Y, Tamaki H, Okada M The effect of hydroxychloroquine on complement status in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus; Analysis of Japanese real-world patients with SLE in a large single center over twelve-month period Lupus Science & Medicine 2019;6. [CrossRef]

- Savarino, A., Boelaert, J. R., Cassone, A., Majori, G., and Cauda, R. (2003). Effects of chloroquine on viral infections: an old drug against today’s diseases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3, 722–727. [CrossRef]

- Kwiek, J. J., Haystead, T. A. J., and Rudolph, J. (2004). Kinetic mechanism of quinone oxidoreductase 2 and its inhibition by the antimalarial quinolines†. Biochemistry 43, 4538–4547. [CrossRef]

- Fantini J, Chahinian H, Yahi N. Synergistic antiviral effect of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in combination against SARS-CoV-2: What molecular dynamics studies of virus-host interactions reveal. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 Aug;56(2):106020. Epub 2020 May 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, D. J., Gudsoorkar, V. S., Weisman, M. H., and Venuturupalli, S. R. (2012). New insights into mechanisms of therapeutic effects of antimalarial agents in SLE. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 8, 522–533. [CrossRef]

- Fantini, J., Di Scala, C., Chahinian, H., and Yahi, N. (2020). Structural and molecular modelling studies reveal a new mechanism of action of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents, 55, 105960. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J., Silverman, E., and Bargman, J. M. (2011). The role of antimalarial agents in the treatment of SLE and lupus nephritis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 7, 718–729. [CrossRef]

- Andreani J, Le Bideau M, Duflot I, Jardot P, Rolland C, Boxberger M, Wurtz N, Rolain JM, Colson P, La Scola B, Raoult D. In vitro testing of combined hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin on SARS-CoV-2 shows synergistic effect. Microb Pathog. 2020 Aug;145:104228. Epub 2020 Apr 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hannah Ritchie, Edouard Mathieu, Lucas Rodés-Guirao, Cameron Appel, Charlie Giattino, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Joe Hasell, Bobbie Macdonald, Diana Beltekian and Max Roser (2020) - “Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)”. Published online at OurWorldInData.org.

- Food and Drug Administration (2020), FDA cautions against use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for COVID-19 outside of the hospital setting or a clinical trial due to risk of heart rhythm problems. Does not affect FDA-approved uses for malaria, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-cautions-against-use-hydroxychloroquine-or-chloroquine-covid-19-outside-hospital-setting-or.

- Carlo Cervia-Hasler et al. Persistent complement dysregulation with signs of thromboinflammation in active Long Covid.Science383,eadg7942(2024). [CrossRef]

- Rajasingham, R., Bangdiwala, A. S., Nicol, M. R., Skipper, C. P., Pastick, K. A., Margaret, L. A., et al. (2020). Hydroxychloroquine as pre-exposure prophylaxis for COVID-19 in healthcare workers: a randomized trial. medRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Younis NK, Zareef RO, Al Hassan SN, Bitar F, Eid AH and Arabi M (2020) Hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 Patients: Pros and Cons. Front. Pharmacol. 11:597985. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).