1. Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is associated

with abnormalities in the humoral and cellular immune responses. These changes,

associated both with the immunosuppressive therapy needed to control disease

manifestations and with active disease itself, are predisposing factors for

greater susceptibility to infections and progression to serious outcomes of

such infections [1,2]. Several previous

studies have shown that infections are the leading cause of both early and late

mortality in patients with SLE [3].

Individuals with SLE have an approximately sixfold

risk of serious infections compared to the general population [4]. The emergence of COVID-19, the infection caused

by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has been a cause of great concern for this vulnerable

population. Among the immune-mediated rheumatic diseases, SLE is associated

with some of the most severe manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection and some of

the highest hospitalization rates for COVID-19 [5,6].

Data from previous studies during pre-vaccination waves suggest hospitalization

rates of around 20%, with one reporting a rate of over 50% [7,8].

Immunization is one of the most effective tools for

preventing infections as a public health strategy, contributing to a reduced

incidence of serious cases of infectious disease and, consequently, reducing

interpersonal spread [9]. Patients with

immune-mediated rheumatic diseases exhibit different degrees of

immunosuppression depending on their therapeutic regimen, their level of

disease activity and the manifestations of their disease [10]. Live-attenuated vaccines are generally

contraindicated in this patient population due to the risk of the small amount

of live virus particles present inducing uncontrolled infection, but they may

be considered in selected patients with a lower degree of immunosuppression and

a favorable risk-benefit ratio. Conversely, inactivated vaccines are

recommended for use in immunosuppressed patients, preferably those whose

disease is in remission or before starting immunosuppressive therapy [11,12].

Data on vaccine response in SLE are controversial.

The immune response to vaccines and their real-world effectiveness are affected

by several host factors. Therefore, immunogenicity is hypothesized to be lower

in patients with SLE. A previous meta-analysis which evaluated the efficacy of

the influenza vaccine demonstrated lower immunogenicity in individuals with SLE

when compared to healthy controls, although the level of immunity achieved was

still considered protective [13].

Concerns regarding vaccine efficacy in these

patients were amplified for SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, which underwent a fast-tracked

emergency marketing authorization process and were developed on a wide range of

different platforms. Given these uncertainties, the objective of this study was

to evaluate the magnitude of the immune response and the real-world

effectiveness of these vaccines in individuals with SLE.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This study evaluated patients with SLE included in

the multicenter Study of Safety, Effectiveness and Duration of Immunity after

Vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in Patients with Immune-Mediated Inflammatory

Diseases (SAFER), a Brazilian observational, prospective, phase IV cohort study

started in June 2021 and completed in March 2024. Patients over 18 years of age

who met the 2019 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of

Rheumatology Associations (ACR/EULAR) classification criteria for SLE [14] and who had received any SARS-CoV-2 vaccine as

recommended in the Brazilian National Immunization Plan were included. The

exclusion criteria were history of previous adverse vaccine reaction,

pregnancy, and immunosuppression for any other reason (HIV, organ

transplantation, malignancy).

The included patients received a complete

vaccination schedule (2-dose regimen plus booster) against SARS-CoV-2 with

vaccines approved by the Brazilian Health Surveillance Agency, namely CoronaVac

(Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine), ChAdOx-1 (AstraZeneca), and BNT162b2

(Pfizer-BioNTech). All vaccine doses were administered as indicated by a

medical professional under supervision.

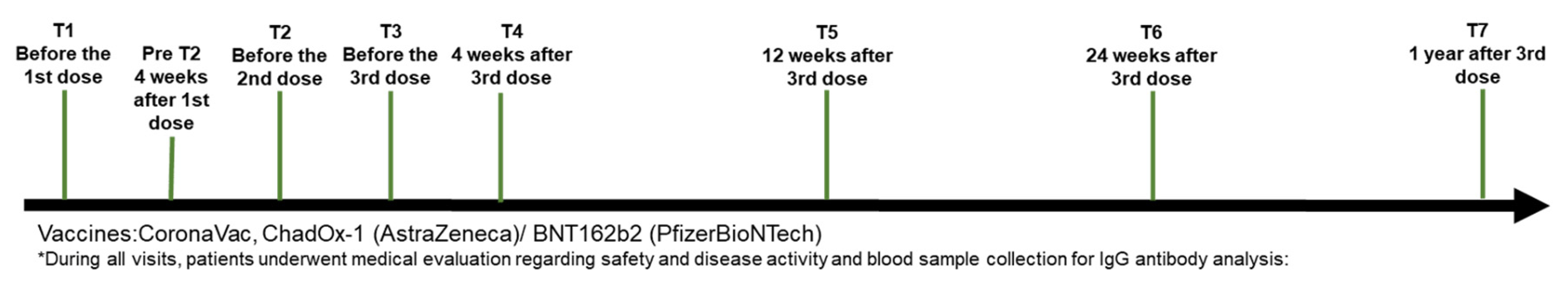

Patients were evaluated at different time points

before and after vaccine exposure (baseline, T1; before the 2nd and 3rd dose,

T2 and T3 respectively; four weeks after the 3rd dose, T4; three months after

the 3rd dose, T5; six months after the 3rd dose, T6; and 12 months after the

3rd dose, T7), with in-person and telephone monitoring conducted in the

intervals between in-person visits [Figure 1].

2.2. Variables of Interest

Demographic data (age, sex, and race), comorbidities,

and history of COVID-19 infection prior to vaccination were recorded at the

baseline visit. Disease activity score (SLEDAI-2K)—categorized into remission

(SLEDAI-2K = 0), low activity (SLEDAI-2K 1–5), or moderate to high activity

(SLEDAI 2K > 6)—and degree of immunosuppression were recorded at baseline

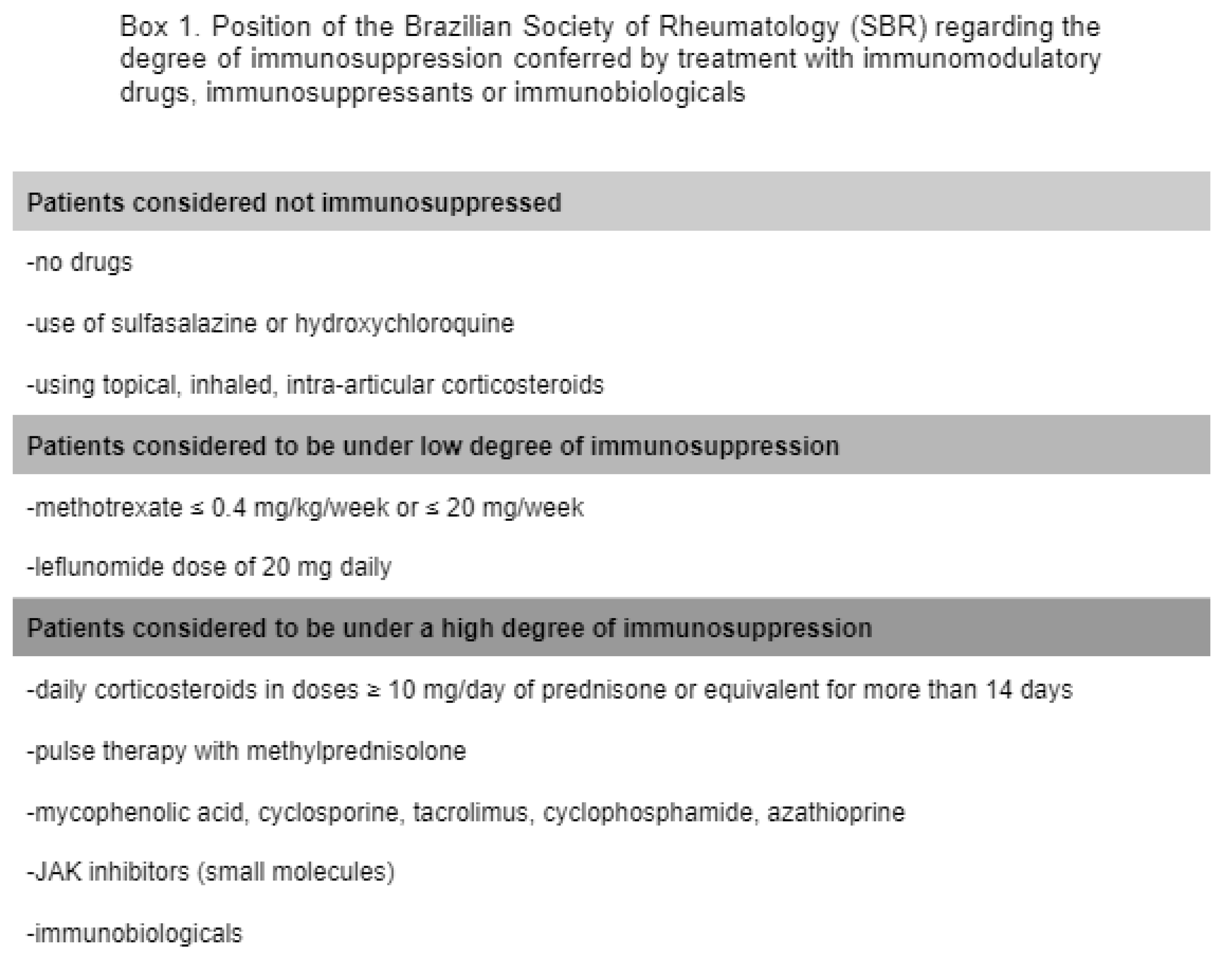

and subsequent assessments. The degree of immunosuppression was assessed

following the recommendations of the Brazilian Society of Rheumatology,

consistent with the risk of infectious events conferred by each medication [box

1] [15].

Biological specimens were collected at all visits

to measure the serologic response to vaccination, assessed by chemiluminescence

methods. The Elecsys® Anti-Sars-Cov-2 S immunoassay (Roche),

validated by the World Health Organization, was used [16].

Surveillance of symptomatic COVID-19 cases was

carried out remotely, periodically (every 2 weeks) or reactively. Patients who

developed symptoms consistent with COVID-19 infection for up to 12 months after

their last vaccine dose were advised to undergo nasal swab collection for PCR

testing; the outcomes were monitored by the study team.

The date of vaccine administration and type of

vaccine administered were recorded and categorized by the vaccine platform of

the first 2 doses. For cases of COVID-19, clinical presentation, date of

symptom onset, and duration and severity of infection were assessed.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using Stata (v.17) and R

(v.4.2.0) software. For all tests, statistical significance was accepted at the

5% level and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

We performed a descriptive analysis of demographic

data, comorbidities, disease activity score, and degree of immunosuppression

(using the definition recommended by the Brazilian Society of Rheumatology),

stratified by vaccine platform. For categorical variables, proportions between

groups were compared using the chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. For

continuous variables, proportions between groups were expressed as means and

standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges as appropriate. We analyzed

these variables using ANOVA and the Wilcoxon test (2 groups) or Kruskal–Wallis

test (>2 groups), respectively.

Humoral immunogenicity data were evaluated as the

seroconversion rate by vaccine group, according to collection time and

treatment type. Within each group, we compared the proportions of

seroconversion as well as the geometric means of antibody titers. For analysis

of IgG titers, data were normalized by log10-transformation.

Analysis of normalized IgG titers over time was then performed using the

nonparametric Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni correction. A

multivariate (linear) regression model for IgG titers was adjusted for disease

activity and degree of immunosuppression.

2.4. Ethical Aspects

The study was submitted to the National Research

Ethics Commission for approval (CAAE 43479221.0.1001.5505) and to the Research

Ethics Committees of all participating centers and was conducted in accordance

with the applicable guidelines and standards that regulate research on human

subjects. All participants signed an Informed Consent Form (ICF) after being

informed of the objective and protocol of the study.

All biosafety guidelines and Good Clinical

Laboratory Practices were followed.

3. Results

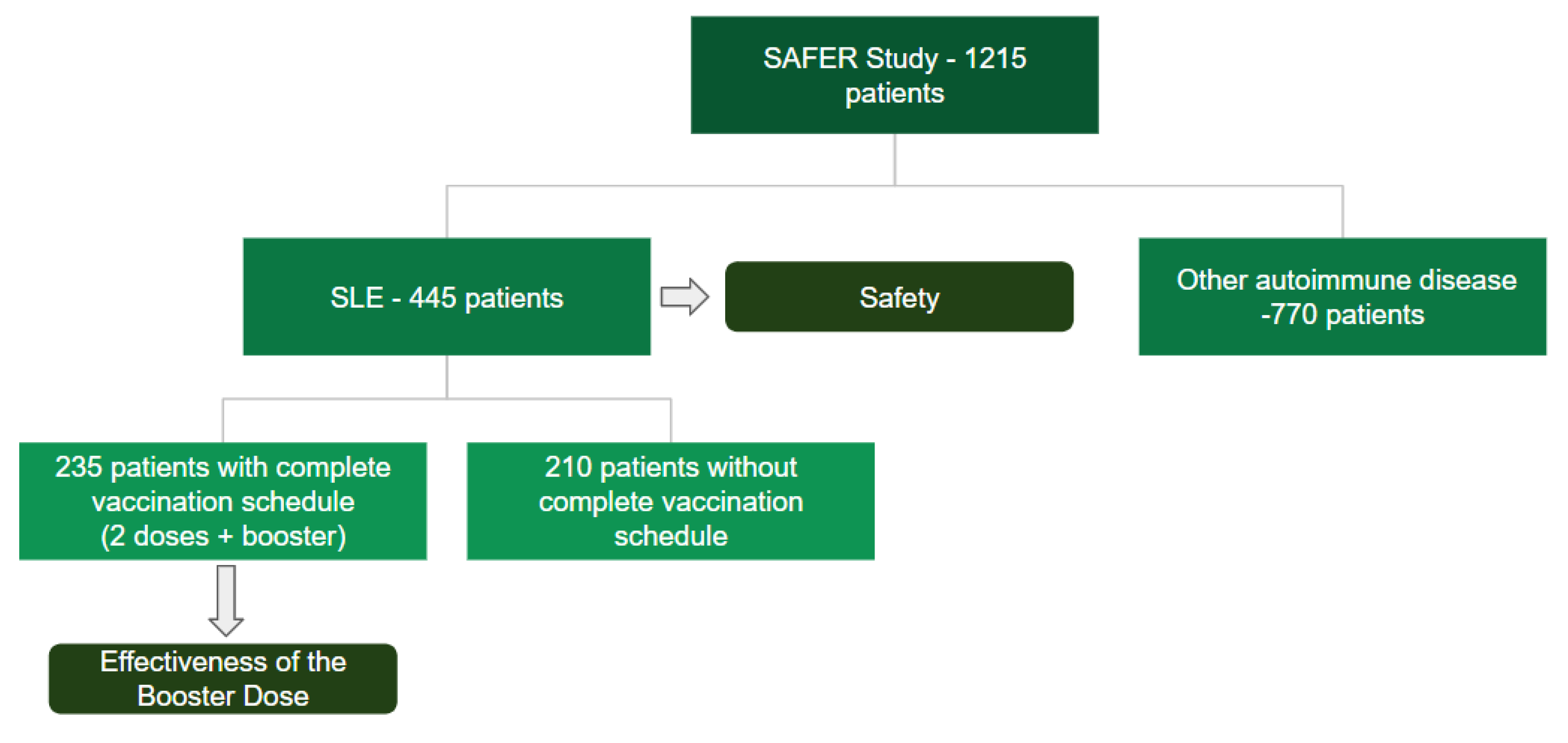

The present study included a total of 445 patients

with SLE, of whom 235 patients over 18 years of age completed a 3-dose COVID-19

vaccination schedule [Figure 2].

Of these, 210 (89.3%) were women and 25 (10.6%)

were men, with an average age of 38 years. Regarding ethnicity/skin color, 109

(46.3%) self-identified as brown and 87 (37%) as white. The median duration of

SLE follow-up was 10 years (interquartile range 5-16 years). Approximately

39.1% of individuals had no other comorbidities. Among reported comorbidities,

27.2% had hypertension and 11.4% had obesity; others included hypothyroidism,

osteonecrosis, and dyslipidemia. According to the SLEDAI-2K score, most

patients (72.4%) were in remission or had low disease activity. Regarding the

severity of immunosuppression, 135 (58.1%) had a high degree of

immunosuppression and 70 (30.1%) were not immunosuppressed [Table 1]. Concerning pharmacotherapy, 82.5% of

patients were on hydroxychloroquine; among immunosuppressants, azathioprine and

mycophenolate were equally common (22.98%). Approximately 50% of patients were

on oral glucocorticoids, most (48.2%) at doses of up to 5 mg per day [Table 2].

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics at inclusion.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics at inclusion.

| |

Total N = 235

|

CoronaVac + BNT162b2

N=116

|

ChadOx-1+ BNT162b2

N=87

|

BNT162b2 + BNT162b2

N=32

|

P |

| Sex, % |

|

|

|

|

0.54 |

| Female |

210 (89.36) |

101 (87.07) |

79 (90.80) |

30 (93.75) |

|

| Age, mean (SD) |

38.0 (29.0-46.0) |

35.5 (28.0-45.0) |

40.0 (31.0-47.0) |

37.5 (32.0-46.0) |

0.095 |

| Skin color (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.30 |

| White |

87 (37.02) |

51 (43.97) |

27 (31.03) |

9 (28.13) |

|

| Black |

33 (14.04) |

15 (12.93) |

14 (16.09) |

4 (12.50) |

|

| Brown |

109 (46.38) |

46 (39.66) |

45 (51.72) |

18 (56.25) |

|

| Disease in years, median (IQR) |

10 (5-16) |

8 (4-15) |

12 (7-18) |

7.7 (4-14) |

0.006 |

| Smoking, % |

15 (6.38) |

11 (9.48) |

4 (4.60) |

0 (0.00) |

0.13 |

| No comorbidities, % |

92 (39.15) |

59 (50.86) |

23 (26.44) |

10 (31.25) |

0.001 |

| Heart disease, % |

10 (4.26) |

5 (4.31) |

2 (2.30) |

3 (9.38) |

0.22 |

| Diabetes, % |

11 (4.68) |

6 (5.17) |

4 (4.60) |

1 (3.13) |

1.00 |

| Lung disease, % |

7 (2.98) |

1 (0.86) |

2 (2.30) |

4 (12.50) |

0.007 |

| Kidney disease, % |

4 (1.70) |

2 (1.72) |

2 (2.30) |

0 (0.00) |

1.00 |

| Hypertension, % |

64 (27.23) |

26 (22.41) |

29 (33.33) |

9 (28.13) |

0.22 |

| Obesity, % |

27 (11.49) |

12 (10.34) |

10 (11.49) |

5 (15.63) |

0.71 |

| Other comorbidities*, % |

95 (40.43) |

37 (31.90) |

44 (50.57) |

14 (43.75) |

0.025 |

| APS, % |

19 (8.09) |

11 (9.48) |

6 (6.90) |

2 (6.25) |

0.80 |

| Previous thrombosis, % |

32 (13.62) |

14 (12.07) |

11 (12.64) |

7 (21.88) |

0.34 |

| Disease activity, % |

|

|

|

|

0.056 |

| Remission |

90/225 (40) |

45/109 (41.28) |

30/84 (35.71) |

15/32 (46.88) |

|

| Low activity |

73/225 (32.44) |

28/109 (25.69) |

37/84 (44.05) |

8/32 (25.00) |

|

| Moderate to high activity |

62/225 (27.56) |

36/109 (33.03) |

17/84 (20.24) |

9/32 (28.13) |

|

| Degree of Immunosuppression, % |

|

|

|

|

0.16 |

| No immunosuppression |

70/232 (30.17) |

40/115 (34.78) |

25/86 (29.07) |

5/31 (16.13) |

|

| Low grade |

27/232 (11.64) |

9/115 (7.83) |

12/86 (13.95) |

6/31 (19.35) |

|

| High grade |

135/232 (58.19) |

66/115 (57.39) |

49/86 (56.98) |

20/31 (64.52) |

|

Table 2.

Medications on inclusion.

Table 2.

Medications on inclusion.

| |

Total

N=235

|

CoronaVac + BNT162b2

N=116

|

ChadOx-1

+ BNT162b2

N=87

|

BNT162b2

+ BNT162b2

N=32

|

P |

| Azathioprine, % |

54/235 (22.98) |

27/116 (23.28) |

17/87 (19.54) |

10/32 (31.25) |

0.40 |

| Oral corticosteroid, % |

112/235 (47.66) |

60/116 (51.72) |

38/87 (43.68) |

14/32 (43.75) |

0.47 |

| Oral corticosteroid dose, % |

|

|

|

|

0.007 |

| Up to 5 mg/day |

54/112 (48.21) |

24/60 (40.00) |

25/38 (65.79) |

5/14 (35.71) |

|

| ≥6 a 10 mg/day |

27/112 (24.11) |

14/60 (23.33) |

7/38 (18.42) |

6/14 (42.86) |

|

| ≥11 a 20 mg/day |

19/112 (16.96) |

10/60 (16.67) |

6/38 (15.79) |

3/14 (21.43) |

|

| >20 mg/day |

12/112 (10.71) |

12/60 (20.00) |

0/38 (0.00) |

0/14 (0.00) |

|

| Hydroxychloroquine, % |

194/235 (82.55) |

98/116 (84.48) |

68/87 (78.16) |

28/32 (87.50) |

0.37 |

| Mycophenolate, % |

54/235 (22.98) |

22/116 (18.97) |

25/87 (28.74) |

7/32 (21.88) |

0.26 |

| Methotrexate, % |

32/235 (13.62) |

12/116 (10.34) |

14/87 (16.09) |

6/32 (18.75) |

0.33 |

| Methotrexate dose, % |

|

|

|

|

0.88 |

| ≤20 mg/week |

23/32 (71.88) |

8/12 (66.67) |

10/14 (71.43) |

5/6 (83.33) |

|

| >20 mg/week |

9/32 (28.13) |

4/12 (33.33) |

4/14 (28.57) |

1/6 (16.67) |

|

| Rituximab (regular use), % |

7/235 (2.98) |

2/116 (1.72) |

5/87 (5.75) |

0/32 (0.00) |

0.17 |

Regarding vaccine platforms and immunization schedules, 116 patients received 2 doses of CoronaVac followed by 1 dose of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) vaccine, 87 received 2 doses of ChAdOx1-S (AstraZeneca) followed by 1 dose of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) vaccine, and 32 received 3 doses of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) vaccine.

Considering effectiveness data, within the 120-day follow-up period after the booster dose of vaccine, there were 28 incident cases of COVID-19 in patients with respiratory symptoms diagnosed more than 15 days after their 2nd dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Four cases of COVID-19 were diagnosed 15 days after the first dose of vaccine. No difference in the rate of incident cases was found between the different vaccination schedules [

Table 3].

Among patients diagnosed with COVID-19, the majority presented with mild symptoms of fatigue, weakness, changes in smell and taste, cough, and shortness of breath not meeting criteria for severity. Of the 28 infected patients, only 4 sought medical attention; all were seen at urgent care facilities and did not require hospitalization.

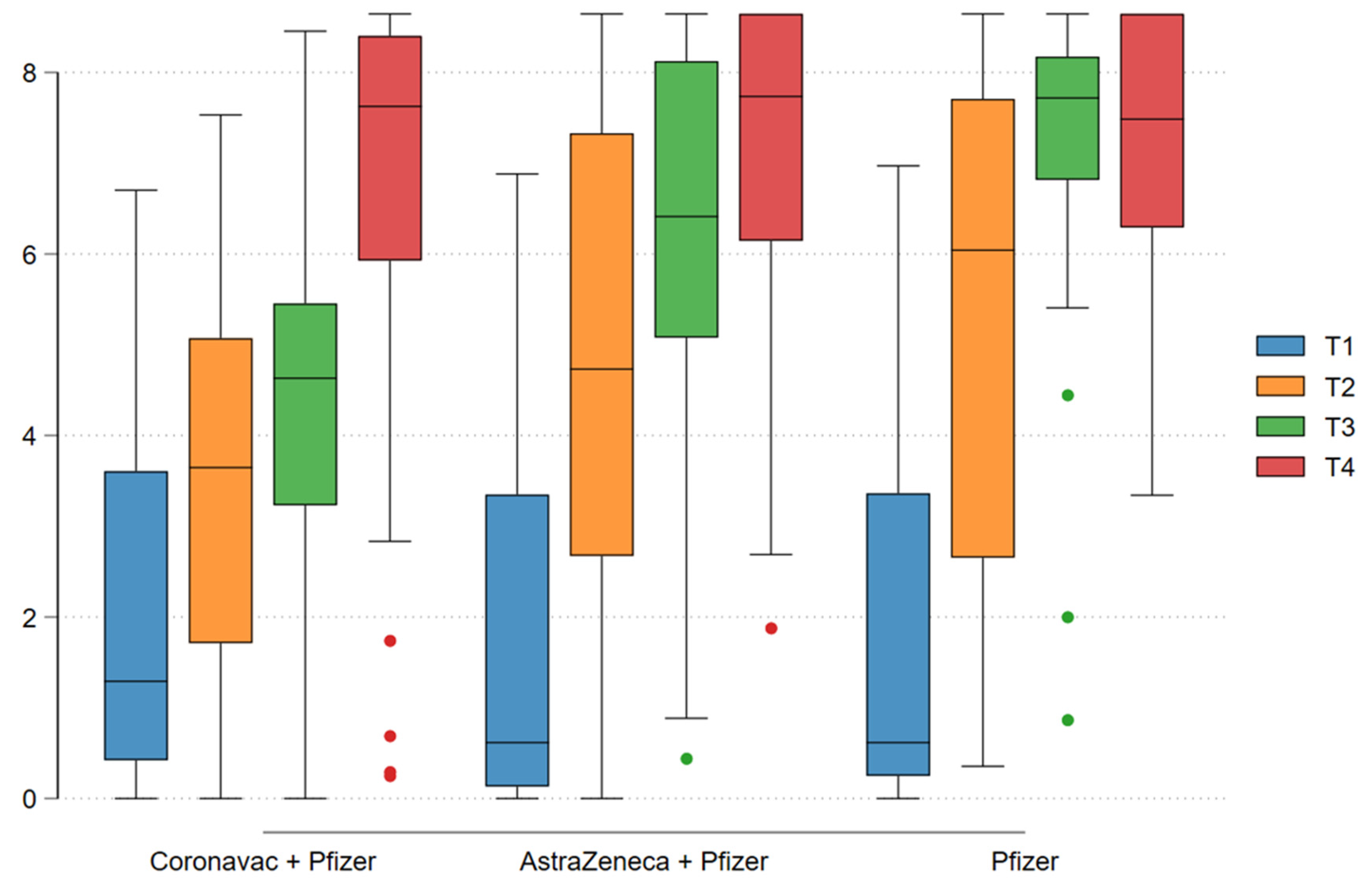

Analysis of the immunogenicity data showed an increase in seroconversion rate after the vaccine doses were administered, with no difference between vaccination schedules. Seropositivity was 39.47% at enrollment and 97.57% after the booster dose. Regarding IgG antibody titers (log-transformed), increases in geometric mean IgG titers were seen after each dose in the different vaccination schedules (log 1.86 at enrollment to log 7.06 after the third dose). Antibody titers after the second dose varied between the different vaccine platforms: log 4.37 for CoronaVac, log 6.30 for ChAdOx-1, and log 7.09 for BNT162b2 (p < 0.001), with a statistically significant difference demonstrating superiority of schedules containing ChAdOx-1 (AstraZeneca) and BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) over CoronaVac (p < 0.001). However, after the third dose, IgG titers was similar across all vaccination schedules (p = 0.68) [

Table 4]. [Graph 1].

Graph 1: T1: Enrollment; T2: After 1st dose; T3: After 2nd dose; T4: After 3rd dose. Assessment of immunogenicity throughout the vaccination period based on IgG antibody titers with each vaccination schedule.

Graph 1.

T1: Enrollment; T2: After 1st dose; T3: After 2nd dose; T4: After 3rd dose. Assessment of immunogenicity throughout the vaccination period based on IgG antibody titers with each vaccination schedule

Graph 1.

T1: Enrollment; T2: After 1st dose; T3: After 2nd dose; T4: After 3rd dose. Assessment of immunogenicity throughout the vaccination period based on IgG antibody titers with each vaccination schedule

In the multivariate linear regression model, considering immunogenicity (IgG titer after the 3rd dose of the vaccine) as the outcome variable, there was no association between disease activity or degree of immunosuppression with anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG titers after the 3rd (booster) dose of vaccine in patients with SLE (p > 0.05%) [

Table 5].

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrated high immunogenicity against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with SLE after a complete vaccination schedule (2 doses + 1 booster dose), regardless of the vaccine platform administered. This is one of the first studies to evaluate the response to different immunization schemes—CoronaVac (Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine), ChAdOx-1 (AstraZeneca), and BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech)—with an added booster dose in this patient population. Among the 235 patients with SLE included, an increase in antibody titers was observed after vaccination, with a seropositivity rate of 97.57% following a complete vaccination schedule, demonstrating greater induction of humoral immunity when compared to a one- or two-dose homologous vaccination schedule. Furthermore, this prospective longitudinal study was also able to demonstrate the medium-term real-life effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with an immune-mediated rheumatic disease.

Vaccination is a public health strategy to reduce mortality from infectious diseases at the population level. Before a vaccine can be recommended, its efficacy and effectiveness must be assessed; however, measurement of these parameters in many population subgroups, including patients with immune-mediated rheumatic diseases, is severely limited by their exclusion from phase III trials [

17]. Studies evaluating the incidence of hospitalization due to COVID-19 in patients with SLE demonstrated a risk approximately three times higher compared to the general population [

18]. Our prospective cohort found 28 incident cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection; however, all were mild respiratory tract infections, with no hospitalizations or deaths, demonstrating a change from the pre-vaccination scenario in which a higher risk of unfavorable outcomes and mortality was observed in patients with SLE [

19]. This was also reported in cohort studies comparing the outcomes of vaccinated and unvaccinated SLE patients relative to the general population [

20]. Therefore, our findings corroborate the existing data on the effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and provide further evidence of the importance of vaccination in patients with SLE.

The immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with immune-mediated diseases has been the object of several studies since the first stages of development of the different COVID-19 vaccine platforms. However, the recommendation for vaccination of patients with SLE was initially empirical [

21]. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated a seropositivity rate of 81.1% in SLE patients who were vaccinated against COVID-19, a lower rate than that found in our study, in which seropositivity rose from 39.47% at enrollment to 97.57% after completion of any vaccination schedule. This apparent superiority is mainly attributable to the studies included in the meta-analysis, which mostly evaluated outcomes after 2 doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine; only two studies involving a booster-dose schedule were included [

22].

On comparing the different vaccine platforms, we observed a smaller increase in IgG titers in patients who received the CoronaVac vaccine after the first and second doses. This finding is in line with previous studies of live inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine platforms, in which a seroconversion rate of 70.4% was found in patients with immune-mediated diseases (versus 95.5% in the control group), as well as a lower increase in IgG titers [

23].

The degree of immunosuppression in patients with SLE and their degree of disease activity are factors that may be related to blunting of the vaccine response in these individuals. However, we found no such association after multivariate analysis. This is in contrast with data from previous studies in which immunosuppression was found to have an impact on on the vaccine response, especially in patients receiving mycophenolic acid, glucocorticoids, and rituximab [

24,

25]. On analysis of these findings, we believe that the lack of difference in vaccine response in relation to the degree of immunosuppression is attributable to the fact that our study analyzed patients after they had received a booster dose, unlike previous studies which conducted outcome assessment after a two-dose schedule. The significant increase in humoral immunity in patients with an otherwise suboptimal response due to their degree of immunosuppression was also observed in another cohort that evaluated the effect of a booster dose in patients with immune-mediated disease who had received a homologous vaccination schedule with an inactivated-virus or adenovirus-vector vaccine [

26].

Our study has some limitations inherent to observational cohort designs. Although cases of COVID-19 infection were recorded before the vaccination period, some asymptomatic cases may have occurred during the intervals between vaccine doses, thus contributing to an increase in seropositivity in these patients. In an attempt to mitigate this effect, participants were contacted periodically by telephone so they would not underestimate mild symptoms and thus fail to undergo confirmatory diagnostic testing.

The strengths of this study are several, and include the number of participants enrolled, the length of follow-up and the real-world setting; as it was conducted following the recommendations of health agencies during the pandemic, it provided an accurate picture of the response to a boosted vaccination schedule as was recommended at the time for high-risk subgroups.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated the effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus receiving immunosuppressive therapy, confirming the importance of a complete (2-dose) vaccination schedule followed by a booster dose, which was associated with a significant increase in humoral immunity—especially for patients who received initial vaccination with a live inactivated vaccine.

Funding

This research was sponsored by the Brazilian Ministry of Health Department of Science and Technology (DECIT/MS).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Network of Observational Studies for monitoring the effectiveness and safety of vaccination against COVID-19 in Brazil and the natural history of the disease in children and teenagers, affiliated with the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), and the Department of Medical Affairs, Clinical Trials, and Postmarketing Surveillance at Bio-Manguinhos/Fiocruz for their technical and operational support. This research was sponsored by the Brazilian Ministry of Health Department of Science and Technology (DECIT/MS).

References

- Danza A, Ruiz-Irastorza G. Infection risk in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: susceptibility factors and preventive strategies. Lupus. 2013;22(12): 1286-94. Review.

- Rao M, Mikdashi J. A Framework to Overcome Challenges in the Management of Infections in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Open Access Rheumatol. 2023 Jul 27;15:125-137. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urowitz MB, Bookman AA, Koehler BE, Gordon DA, Smythe HA, Ogryzlo MA. The bimodal mortality pattern of systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Med. 1976;60(2):221-5.

- Herrinton LJ, Liu L, Goldfien R, Michaels MA, Tran TN. Risk of Serious Infection for Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Starting Glucocorticoids with or without Antimalarials. J Rheumatol. 2016 Aug;43(8):1503-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu XL, Qian Y, Jin XH, Yu HR, Du L, Wu H, Chen HL, Shi YQ. COVID-19 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review. Lupus. 2022 May;31(6):684-696. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianfrancesco M, Hyrich KL, Al- Adely S, et al. Characteristics associated with hospitalisation for COVID-19 in people with rheumatic disease: data from the COVID-19 global rheumatology alliance physician- reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:859–66. —-> Fernandez-Ruiz R, Masson M, Kim MY, Myers B, Haberman RH, Castillo R, Scher JU, Guttmann A, Carlucci PM, Deonaraine KK, Golpanian M, Robins K, Chang M, Belmont HM, Buyon JP, Blazer AD, Saxena A, Izmirly PM; NYU WARCOV Investigators.

- Marques CDL, Kakehasi AM, Pinheiro MM, Mota LMH, Albuquerque CP, Silva CR, Santos GPJ, Reis-Neto ET, Matos P, Devide G, Dantas A, Giorgi RD, Marinho AO, Valadares LDA, Melo AKG, Ribeiro FM, Ferreira GA, Santos FPS, Ribeiro SLE, Andrade NPB, Yazbek MA, Souza VA, Paiva ES, Azevedo VF, Freitas ABSB, Provenza JR, Toledo RA, Fontenelle S, Carneiro S, Xavier R, Pileggi GCS, Reis APMG. High levels of immunosuppression are related to unfavourable outcomes in hospitalised patients with rheumatic diseases and COVID-19: first results of ReumaCoV Brasil registry. RMD Open. 2021 Jan;7(1):e001461. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leveraging the United States Epicenter to Provide Insights on COVID-19 in Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Dec;72(12):1971-1980. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luz KR da, Souza DCC de, Ciconelli RM. Vacinação em pacientes imunossuprimidos e com doenças reumatológicas auto-imunes. Rev Bras Reumatol [Internet]. 2007 Mar;47(2):106–13. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Avery, RK. Vaccination of the immunosuppressed adult patient with rheumatologic disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1999 Aug;25(3):567-84, viii. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furer V, Rondaan C, Heijstek MW, et al.2019 update of EULAR recommendations for vaccination in adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2020;79:39-52.

- Garg M, Mufti N, Palmore TN, Hasni SA. Recommendations and barriers to vaccination in systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2018 Oct;17(10):990-1001. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao Z, Tang H, Xu X, Liang Y, Xiong Y, et al. (2016) Immunogenicity and Safety of Influenza Vaccination in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients Compared with Healthy Controls: A Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE 11(2): e0147856. [CrossRef]

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, Brinks R, Mosca M, Ramsey-Goldman R, Smolen JS, Wofsy D, Boumpas DT, Kamen DL, Jayne D, Cervera R, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Diamond B, Gladman DD, Hahn B, Hiepe F, Jacobsen S, Khanna D, Lerstrøm K, Massarotti E, McCune J, Ruiz-Irastorza G, Sanchez-Guerrero J, Schneider M, Urowitz M, Bertsias G, Hoyer BF, Leuchten N, Tani C, Tedeschi SK, Touma Z, Schmajuk G, Anic B, Assan F, Chan TM, Clarke AE, Crow MK, Czirják L, Doria A, Graninger W, Halda-Kiss B, Hasni S, Izmirly PM, Jung M, Kumánovics G, Mariette X, Padjen I, Pego-Reigosa JM, Romero-Diaz J, Rúa-Figueroa Fernández Í, Seror R, Stummvoll GH, Tanaka Y, Tektonidou MG, Vasconcelos C, Vital EM, Wallace DJ, Yavuz S, Meroni PL, Fritzler MJ, Naden R, Dörner T, Johnson SR. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Sep;71(9):1400-1412. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pileggi, G.S. , et al., Brazilian recommendations on the safety and effectiveness of the yellow fever vaccination in patients with chronic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. AdvRheumatol, 2019.59(1): p.17.

- Jochum S, Kirste I, Hortsch S, Grunert VP, Legault H, Eichenlaub U, Kashlan B, Pajon R. Clinical utility of Elecsys Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S assay in COVID-19 vaccination: An exploratory analysis of the mRNA-1273 phase 1 trial. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2021 Oct 19:2021.10.04.21264521. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianfrancesco M, Hyrich KL, Al-Adely S, Carmona L, Danila MI, Gossec L, Izadi Z, Jacobsohn L, Katz P, Lawson-Tovey S, Mateus EF, Rush S, Schmajuk G, Simard J, Strangfeld A, Trupin L, Wysham KD, Bhana S, Costello W, Grainger R, Hausmann JS, Liew JW, Sirotich E, Sufka P, Wallace ZS, Yazdany J, Machado PM, Robinson PC; COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance. Characteristics associated with hospitalisation for COVID-19 in people with rheumatic disease: data from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician-reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Jul;79(7):859-866. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westra J, Rondaan C, van Assen S, Bijl M. Vaccination of patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015 Mar;11(3):135-45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordtz R, Kristensen S, Dalgaard LPH, Westermann R, Duch K, Lindhardsen J, Torp-Pedersen C, Dreyer L. Incidence of COVID-19 Hospitalisation in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Nationwide Cohort Study from Denmark. J Clin Med. 2021 Aug 27;10(17):3842. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang X, Sparks J, Wallace Z, Deng X, Li H, Lu N, Xie D, Wang Y, Zeng C, Lei G, Wei J, Zhang Y. Risk of COVID-19 among unvaccinated and vaccinated patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a general population study. RMD Open. 2023 Mar;9(1):e002839. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bijlsma, JW. EULAR 20 view points on SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with RMDs. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:411–2. 20 December.

- Tan SYS, Yee AM, Sim JJL, Lim CC. COVID-19 vaccination in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review of its effectiveness, immunogenicity, flares and acceptance. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023 ;62(5):1757-1772. 2 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros-Ribeiro, A.C. , Aikawa, N.E., Saad, C.G.S. et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the CoronaVac inactivated vaccine in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases: a phase 4 trial. Nat Med 27, 1744–1751 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Yuki EFN, Borba EF, Pasoto SG, Seguro LP, Lopes M, Saad CGS, Medeiros-Ribeiro AC, Silva CA, de Andrade DCO, Kupa LVK, Betancourt L, Bertoglio I, Valim J, Hoff C, Formiga FFC, Pedrosa T, Kallas EG, Aikawa NE, Bonfa E. Impact of Distinct Therapies on Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2022 Apr;74(4):562-571. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izmirly PM, Kim MY, Samanovic M, Fernandez-Ruiz R, Ohana S, Deonaraine KK, Engel AJ, Masson M, Xie X, Cornelius AR, Herati RS, Haberman RH, Scher JU, Guttmann A, Blank RB, Plotz B, Haj-Ali M, Banbury B, Stream S, Hasan G, Ho G, Rackoff P, Blazer AD, Tseng CE, Belmont HM, Saxena A, Mulligan MJ, Clancy RM, Buyon JP. Evaluation of Immune Response and Disease Status in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients Following SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022 Feb;74(2):284-294. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assawasaksakul T, Sathitratanacheewin S, Vichaiwattana P, Wanlapakorn N, Poovorawan Y, Avihingsanon Y, Assawasaksakul N, Kittanamongkolchai W. Immunogenicity of the third and fourth BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 boosters and factors associated with immune response in patients with SLE and rheumatoid arthritis. Lupus Sci Med. 2022 Jul;9(1):e000726. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).