Submitted:

18 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

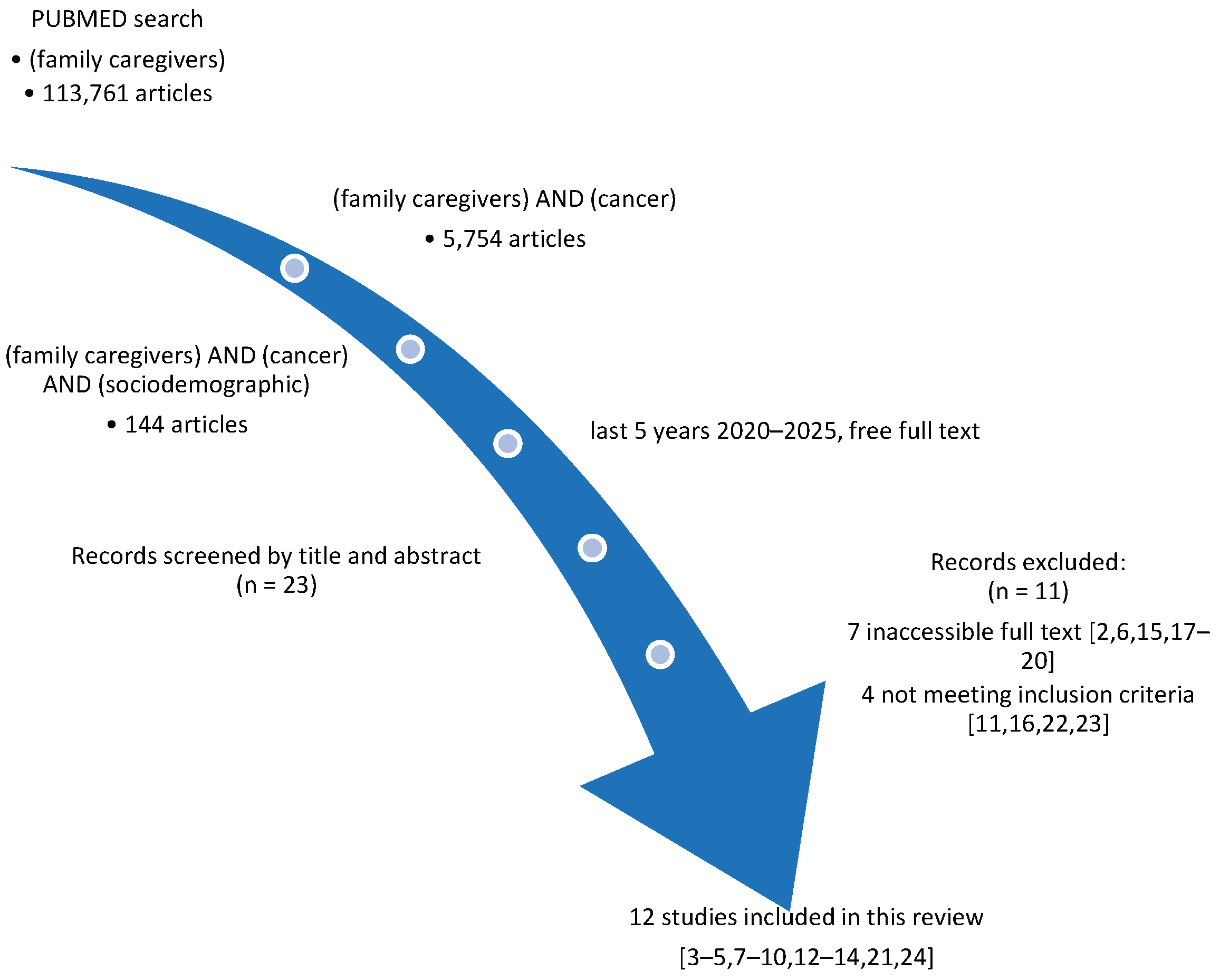

- family caregivers - 113,761 articles,

- (family caregivers) AND (cancer) - 5,754 articles (last 5 years),

- (family caregivers) AND (cancer) AND (sociodemographic) - 144 articles (free/full text).

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Age, Gender, and Marital Status

4.2. Socioeconomic Determinants and Employment

4.3. Rurality, Caregiver Role, and Family Composition

4.4. Cultural and Religious Influences

4.5. Patient Characteristics and Contextual Factors

4.6. Psychosocial and Health System Support

4.7. Contradictions and Methodological Diversity

5. Conclusions

6. Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bechthold, A.C.; Azuero, A.; Puga, F.; Ejem, D.B.; Kent, E.E.; Ornstein, K.A.; Ladores, S.L.; Wilson, C.M.; Knoepke, C.E.; Miller-Sonet, E.; et al. What Is Most Important to Family Caregivers When Helping Patients Make Treatment-Related Decisions: Findings from a National Survey. Cancers 2023, 15, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.P.; Haque, Md.I.; Hossain, Md.B.; Sarker, R.J.; Abedin, E.S.; Shahinuzzaman, Md.; Saifuddin, K.; Kabir, R.; Alauddin Chowdhury, A. Depression and Anxiety Status among Informal Caregivers of Patients with Cancer Treated at Selected Tertiary Hospitals in Nepal. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences 2024, 19, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourissi, H.; Bourkhime, H.; El Rhazi, K.; Mellas, S. Exploring Factors Influencing the Physical and Mental Quality of Life of Caregivers of Cancer Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study at Hassan II University Hospital Center. Cureus 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belapurkar, P.; Acharya, S.; Shukla, S.; Kumar, S.; Khurana, K.; Acharya, N. Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression, and Perceived Stress Among Family Caregivers of Patients Diagnosed With Oral Cancer in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Central India: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Huang, X.; Yan, H. Relationship between Sense of Coherence and Subjective Well-Being among Family Caregivers of Breast Cancer Patients: A Latent Profile Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 1515570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Mullan, J.T.; Semple, S.J.; Skaff, M.M. Caregiving and the Stress Process: An Overview of Concepts and Their Measures. The Gerontologist 1990, 30, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M.; Friel, S.; Bell, R.; Houweling, T.A.; Taylor, S. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. The Lancet 2008, 372, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windle, G. What Is Resilience? A Review and Concept Analysis. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 2011, 21, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Azuero, A.; Taylor, R.A.; Wells, R.D.; Hendricks, B.A.; Bechthold, A.C.; Reed, R.D.; Harrell, E.R.; Dosse, C.K.; Engler, S.; et al. Resilience, Preparedness, and Distress among Family Caregivers of Patients with Advanced Cancer. Support Care Cancer 2021, 29, 6913–6920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano-Toledano, F.; Luna, D.; Moral De La Rubia, J.; Martínez Valverde, S.; Bermúdez Morón, C.A.; Salazar García, M.; Vasquez Pauca, M.J. Psychosocial Factors Predicting Resilience in Family Caregivers of Children with Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study. IJERPH 2021, 18, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doege, D.; Frick, J.; Eckford, R.D.; Koch-Gallenkamp, L.; Schlander, M.; Baden-Württemberg Cancer Registry; Arndt, V. Anxiety and Depression in Cancer Patients and Survivors in the Context of Restrictions in Contact and Oncological Care during the COVID -19 Pandemic. Intl Journal of Cancer 2025, 156, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, E.A.; Goodwin, B.C.; Myers, L.; March, S.; Aitken, J.F.; Chambers, S.K.; Dunn, J. Support-seeking by Cancer Caregivers Living in Rural Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 2022, 46, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasek, M.; Suchocka, L. A Model of Social Support for a Patient–Informal Caregiver Dyad. BioMed Research International 2022, 2022, 4470366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryl, K.; Tortora, S.; Whitley, J.; Kim, S.-D.; Raghunathan, N.J.; Mao, J.J.; Chimonas, S. Utilization, Delivery, and Outcomes of Dance/Movement Therapy for Pediatric Oncology Patients and Their Caregivers: A Retrospective Chart Review. Current Oncology 2023, 30, 6497–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.M.; Khedr, M.A.; Mansy, A.M.A.; El-Monshed, A.H.; Malek, M.G.N.; El-Ashry, A.M. Assessing Caregiver Stress and Resource Needs in Pediatric Cancer Care. BMC Nurs 2024, 23, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branley, C.E.; Goulding, M.; Tisminetzky, M.; Lemon, S.C. The Association between Multimorbidity and Food Insecurity among US Parents, Guardians, and Caregivers. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado-de-Mendoza, A.; Gonzales, F.; Song, M.; Holmes, E.J.; Graves, K.D.; Retnam, R.; Gómez-Trillos, S.; Lopez, K.; Edmonds, M.C.; Sheppard, V.B. Association between Aspects of Social Support and Health-Related Quality of Life Domains among African American and White Breast Cancer Survivors. J Cancer Surviv 2022, 16, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.L.; Kuharic, M.; Pickard, A.S. A Comparison of a Preliminary Version of the EQ-HWB Short and the 5-Level Version EQ-5D. Value in Health 2022, 25, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.I.; Ghebre, R.; Dwivedi, R.; Macheledt, K.; Watson, S.; Duffy, B.L.; Rogers, E.A.; Pusalavidyasagar, S.; Guo, C.; Misono, S.; et al. Academic Clinician Frontline-Worker Wellbeing and Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic Experience: Were There Gender Differences? Preventive Medicine Reports 2023, 36, 102517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, P.P.; Weitlauf, J.C.; LaMonte, M.J.; Sisto, S.A.; Tomita, M.; Gallagher-Thompson, D.; Shadyab, A.H.; Bidwell, J.T.; Manson, J.E.; Kroenke, C.H.; et al. Caregiving and All-cause Mortality in Postmenopausal Women: Findings from the Women’s Health Initiative. J American Geriatrics Society 2024, 72, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, N.; Park, J.H.; Bang, G.; Kang, D.; Yoon, S.E.; Kim, K.; Cho, J.; Kim, S.J. Different Level and Difficulties with Financial Burden in Multiple Myeloma Patients and Caregivers: A Dyadic Qualitative Study. Seminars in Oncology Nursing 2025, 151848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amonoo, H.L.; Guo, M.; Boardman, A.C.; Acharya, N.; Daskalakis, E.; Deary, E.C.; Waldman, L.P.; Gudenkauf, L.; Lee, S.J.; Joffe, H.; et al. A Positive Psychology Intervention for Caregivers of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Survivors (PATH-C): Initial Testing and Single-Arm Pilot Trial. Transplantation and Cellular Therapy 2024, 30, 448.e1–448.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano-Toledano, F.; Jiménez, S.; Moral De La Rubia, J.; Merino-Soto, C.; Rivera-Rivera, L. Positive Mental Health Scale (PMHS) in Parents of Children with Cancer: A Psychometric Evaluation Using Item Response Theory. Cancers 2023, 15, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karvonen, K.L.; Anunwah, E.; Gilmore, S.; Griffiths-Randolph, U.; Karvonen, K.A.; Moore, D.; Miller, K.; Overall, J.; Wooten, L.; Afulani, P.A. Gaps, Successes, and Opportunities Related to Social Drivers of Health from the Perspectives of Black Preterm Infant Caregivers: A Qualitative Study. The Journal of Pediatrics 2025, 282, 114598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguirre Vergara, F.; Pinker, I.; Fischer, A.; Seuring, T.; Tichomirowa, M.A.; De Beaufort, C.; Kamp, S.-M.; Fagherazzi, G.; Aguayo, G.A. Readiness of Adults with Type 1 Diabetes and Diabetes Caregivers for Diabetes Distress Monitoring Using a Voice-Based Digital Health Solution: Insights from the PsyVoice Mixed Methods Study. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e088424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häger Tibell, L.; Årestedt, K.; Holm, M.; Wallin, V.; Steineck, G.; Hudson, P.; Kreicbergs, U.; Alvariza, A. Preparedness for Caregiving and Preparedness for Death: Associations and Modifiable Thereafter Factors among Family Caregivers of Patients with Advanced Cancer in Specialized Home Care. Death Studies 2024, 48, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Sorensen, S. Gender Differences in Caregiver Stressors, Social Resources, and Health: An Updated Meta-Analysis. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 2006, 61, P33–P45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, C. Intergenerational Family Support in Romania. Rev. Psih. 2014, 60(4), 293–303. [Google Scholar]

- Bordinc, E.; Irsay, L. Indications and Contraindications of Physiotherapy in Breast Cancer Patients. BALNEO 2014, 5, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iancu, M.A.; Dumitra, G.G.; Ivanov, S.M.; Ivanov, A.M.; Sandu, M.N.; Ticarau, A.; Calin, R.D.; Popescu, D.; Condur, L.M.; Popovici, C.; et al. Rehabilitation of the Elderly in Primary Healthcare. Balneo and PRM Research Journal 2025, 16, 791–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Year | Study Type/Design | Population & Setting | Cancer Type | Factors Examined | Wellbeing Outcomes | Key Findings | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amin et al. | 2024 | Cross-sectional descriptive study | 258 caregivers of pediatric cancer patients, Egypt | Pediatric cancer | Age, education, marital status, income, number of children, child’s age, diagnosis duration | Caregiver stress (KCSS), resource needs (CNRA) | Higher stress linked to lower income, higher education; number of children, age, diagnosis duration significant; psychological needs increased stress | Support programs should consider income and educational background; psychological/spiritual support is crucial |

| Bechthold et al. | 2023 | National survey; quantitative analysis with mixed models | 1,661 US caregivers, various cancer types | Various cancer types | Age, race, gender, ethnicity | Values in decision-making (QoL, emotional wellbeing, etc.) | Top factors: QoL, physical/emotional wellbeing; importance of oncology team opinions varied by age, race, gender | Care planning should incorporate diverse caregiver values; culturally sensitive decision-making needed |

| Belapurkar et al. | 2023 | Cross-sectional survey | 82 caregivers of oral cancer patients, India | Oral cancer | Education, employment, income, cancer stage | Depression (BDI-II), Anxiety (MAS), Stress (PSS-10) | High rates of depression (65.1%), anxiety (69.5%), stress (74.7%); lower education and income correlated with worse outcomes | Highlights urgent need for mental health and financial support for low-SES caregivers |

| Bourissi et al. | 2024 | Cross-sectional study | 247 caregivers at Moroccan university hospital | Various (Moroccan setting) | Age, gender, employment, marital status, relationship to patient, cancer type | Physical and mental QoL (SF-12) | Older age, female gender, unemployment and close relation to patient worsened mental and physical QoL | Need for targeted social and economic support interventions for vulnerable subgroups |

| Branley et al. | 2025 | Cross-sectional survey using national data | 26,579 US caregivers (NHIS data) | Various (NHIS caregivers) | Chronic disease count, income, race, gender | Food insecurity | Multimorbidity (esp. with mental conditions) strongly associated with higher food insecurity; disparities across racial/ethnic groups | Public health policies should address chronic health and food security among caregivers, especially in disadvantaged communities |

| Bryl et al. | 2023 | Retrospective chart review | Pediatric oncology patients and their caregivers, US hospital | Pediatric cancer | Not detailed | Intervention participation, psychosocial outcomes | Dance/movement therapy sessions well-received; suggested positive impact on caregiver-child interaction and stress relief | Integrative therapies may benefit both patients and caregivers in pediatric oncology |

| Doege et al. | 2025 | Observational study during COVID-19 | 2439 cancer patients and survivors (including caregivers), Germany | Various cancers | Not caregiver-specific;age, gender, education, marital status, income, living situation | Anxiety, depression during pandemic restrictions | Significant mental health burden noted; caregiver roles contributed to increased anxiety/depression levels | Pandemic preparedness in oncology care should include mental health support for caregivers |

| Häger Tibell et al. | 2024 | Cross-sectional study | 39 Family caregivers in specialized home care, Sweden | Advanced cancer | Gender, relationship to patient, time spent caregiving, age, education, enployment | Preparedness for caregiving and death | Higher preparedness linked with prior training and experience; emotional readiness predicted post-death adaptation | Training programs for end-of-life care could enhance caregiver wellbeing and resilience |

| Sharma et al. | 2024 | Cross-sectional study | 383 Caregivers of cancer patients, Nepal | Various | Age, gender, education, employment, income, marital status | Depression and anxiety (DASS-21) | High prevalence of moderate to severe anxiety and depression; females and unemployed most affected | Mental health screening and support crucial, especially for vulnerable caregivers |

| Toledano-Toledano et al. | 2021 | Cross-sectional study | 330 caregivers of children with cancer, Mexico | Pediatric cancer | Age, gender, education, marital status, religion, income, number of children, caregiver relationship | Resilience (RESI-M), depression, anxiety, QoL, caregiver burden, psychological wellbeing | Resilience positively associated with education, psychological wellbeing and QoL; negatively with depression, anxiety, burden; married and Catholic caregivers showed higher resilience | Tailored psychosocial interventions should consider educational level, marital status and religious support to enhance resilience |

| Toledano-Toledano et al. | 2023 | Cross-sectional psychometric evaluation using IRT | 623 caregivers of children with cancer, Mexico | Pediatric cancer | Age, gender, education, income, family status, religion | Positive mental health (PMHS), depression, anxiety, QoL, caregiver burden, resilience | PMHS is a valid and reliable tool for assessing caregiver mental health; positive mental health moderately independent of depression/anxiety | PMHS can be used in caregiver interventions to monitor mental wellbeing; policies should focus on holistic health support for caregiving parents |

| Wang et al. | 2025 | Latent profile analysis | 360 caregivers of breast cancer patients, China | Breast cancer | Age, gender, income, education, caregiving time, residence, income | Sense of coherence, subjective wellbeing | Three caregiver profiles identified; high coherence linked to better wellbeing; income and education major predictors | Interventions should tailor support based on caregiver profiles and SES |

| Study | Year | Factors Examined | Wellbeing Outcomes | Key Findings |

| Amin et al. | 2024 | Age, education, marital status, income, number of children, children’s age, diagnosis duration, spirituality | Caregiver stress (KCSS), resource needs (CNRA) | Higher stress linked to lower income, rural residence, marital status and higher age (p < 0.01), higher education was a protective factor (p < 0.05); number of children, diagnosis duration (p < 0.05) influenced stress; higher psychological needs increased stress (p < 0.01), spirituality negatively corellated with stress (p < 0.05). |

| Bechthold et al. | 2023 | Age, race, gender, ethnicity | Decision-making preferences, support needs | Caregivers with lower education/income more likely to need treatment information (OR 2.1, p = 0.032); female and non-White caregivers had distinct support preferences (p < 0.05). significant associations between caregiver age and patient quality of life, physical and emotional well-being and the opinions/feelings of the oncology team (p < 0.001); caregiver gender (p = 0.006) and race (p = 0.009) and the opinions/feelings of the oncology team Cramer’s V = 0.079) and caregiver ethnicity and patient physical well-being (p = 0.004) |

| Belapurkar et al. | 2023 | Education, employment, income, cancer stage | Depression (BDI-II), Anxiety (MAS), Stress (PSS-10) | High rates of depression (65.1%), anxiety (69.5%), stress (74.7%); lower education and income significantly associated with worse caregiver outcomes (p < 0.001). Depresion was linked to cancer stage, employment status and lower income to anxiety and educational attainment to distress and anxiety. |

| Bourissi et al. | 2024 | Income, education, employment, marital status | Physical and mental quality of life | Lower education and lower income predicted worse physical and mental QoL (p < 0.05); married caregivers showed better scores (p = 0.041). higher age (over 40), gender (female), close family ties to the pacient and unemployment vere predictors of lower QoL. Regional differences were also found. |

| Branley et al. | 2025 | Chronic disease count, income, race, gender | Food insecurity | Caregivers with 3+ chronic conditions had 2.7× higher odds of food insecurity (95% CI: 1.9–3.6, p < 0.001) and reported more frequently depression and anxiety; race and income disparities were statistically significant. |

| Bryl et al. | 2023 | Caregiver participation, therapy exposure | Engagement, perceived benefit | Therapy decreased caregiver’s burden and improved relationship with the care beneficiar was reported. |

| Doege et al. | 2025 | General caregiver roles (within patient sample) | Anxiety, depression | Significantly increased anxiety (GAD-7, mean = 10.3) and depression (PHQ-9, mean = 11.8) during COVID-19 care restrictions (p < 0.001). |

| Häger Tibell et al. | 2024 | Gender, relationship to patient, time spent caregiving, age, education, enployment | Preparedness for caregiving and death | Higher preparedness correlated with prior caregiving experience (p = 0.008) and emotional readiness (p < 0.01); predictive of better coping after patient death. No result on sociodemographic factors found during review. |

| Sharma et al. | 2024 | Income, rural residence, education, age, gender, employment, income, marital status | Depression, anxiety | Depression and anxiety were significantly higher in rural, low-income caregivers, over 36 years old (p < 0.001); education level also predictive (p = 0.013). married caregivers were more depressed. Hospital type (gouvernamental or not) and pacient cancer stage were also predictors for depression and anxiety. |

| Toledano-Toledano et al. | 2021 | Age, gender, education, marital status, religion, income, number of children, caregiver relationship | Resilience (RESI-M), depression, anxiety, QoL, caregiver burden, psychological wellbeing | Higher resilience linked to education (p = 0.002), psychological wellbeing (p < 0.01); negatively correlated with depression, anxiety, caregiver burden (all p < 0.001). Being married and Catholic predicted higher resilience. Education, income and support networs buffer the effects of care. |

| Toledano-Toledano et al. | 2023 | Income, marital status, age, gender, education, family status, religion | Positive mental health (PMHS) | PMHS scores were independent of resilience, depression, anxiety, caregiver burden and quality of life, |

| Wang et al. | 2025 | Age, gender, income, education, caregiving time, type of residence, cancer stage | Sense of coherence, subjective wellbeing | Profile analysis highlighted that high sense of coherence group had best wellbeing (p < 0.001). Age, residence, income and education, caregiving duration are significant predictors(p < 0.01) of positive mental health and subjective wellbeing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).