Submitted:

18 September 2025

Posted:

19 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Survey

1.2. Contribution and Paper Outline

- We develop a mathematical model for a hybrid mid-level controller, integrated with a diffusive distributed controller at the primary level and a UC framework at the secondary level;

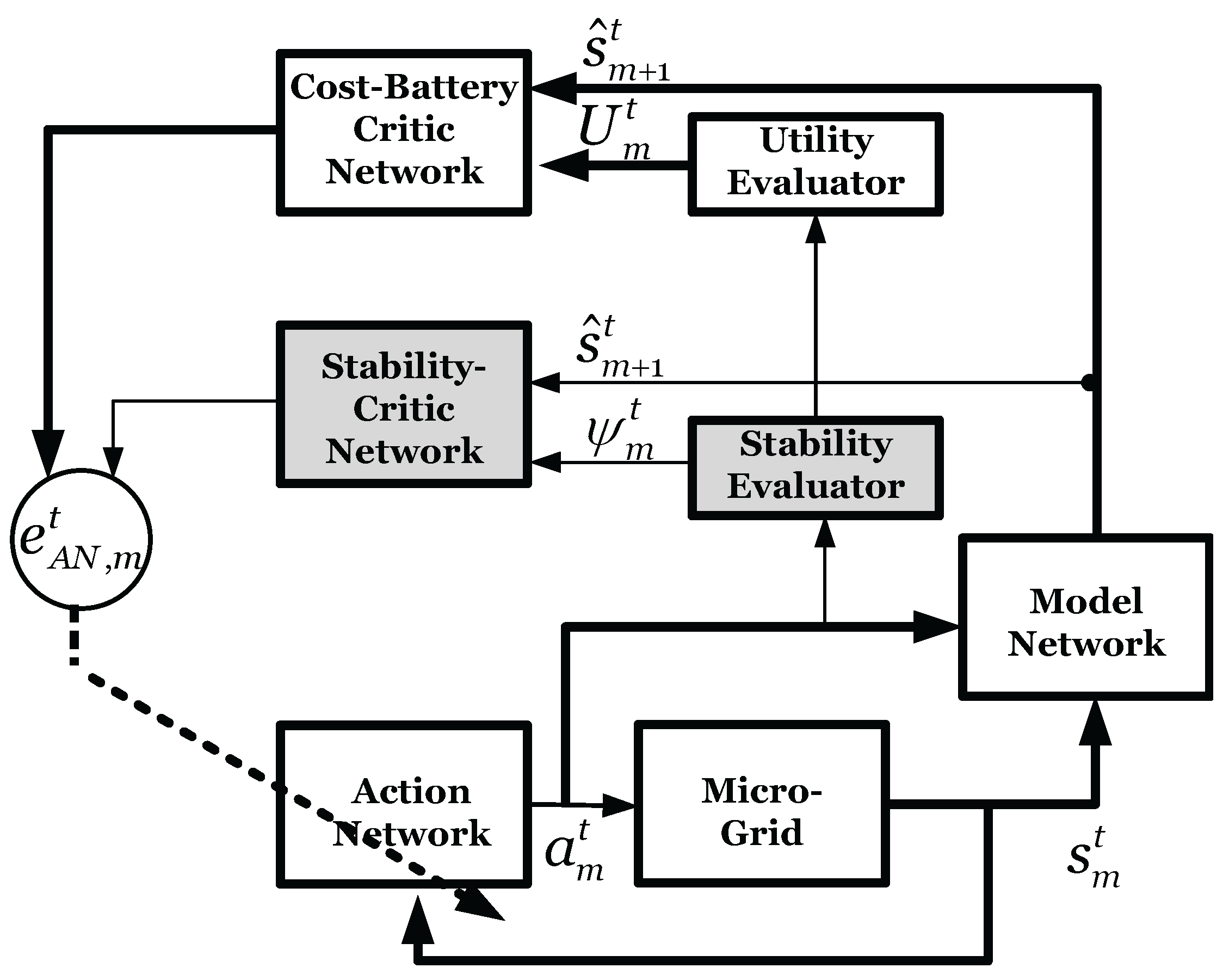

- We propose a two-critic adaptive critic design model to minimize frequency and voltage deviations while ensuring microgrid stability;

- We present a model-free voltage and frequency controller, based on a dynamic programming algorithm, to achieve economic operation and enhance the lifecycle efficiency of the energy storage system (ESS).

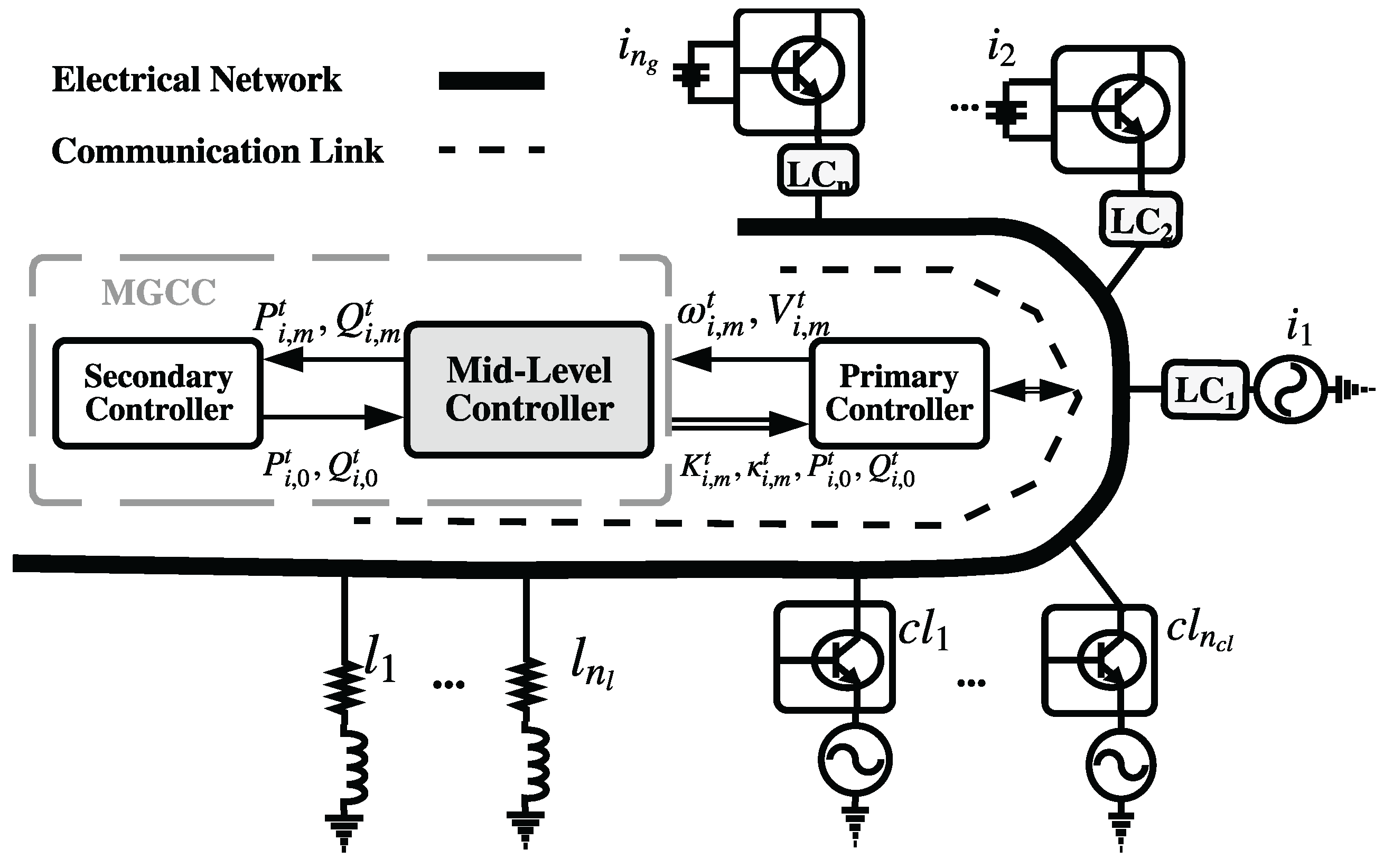

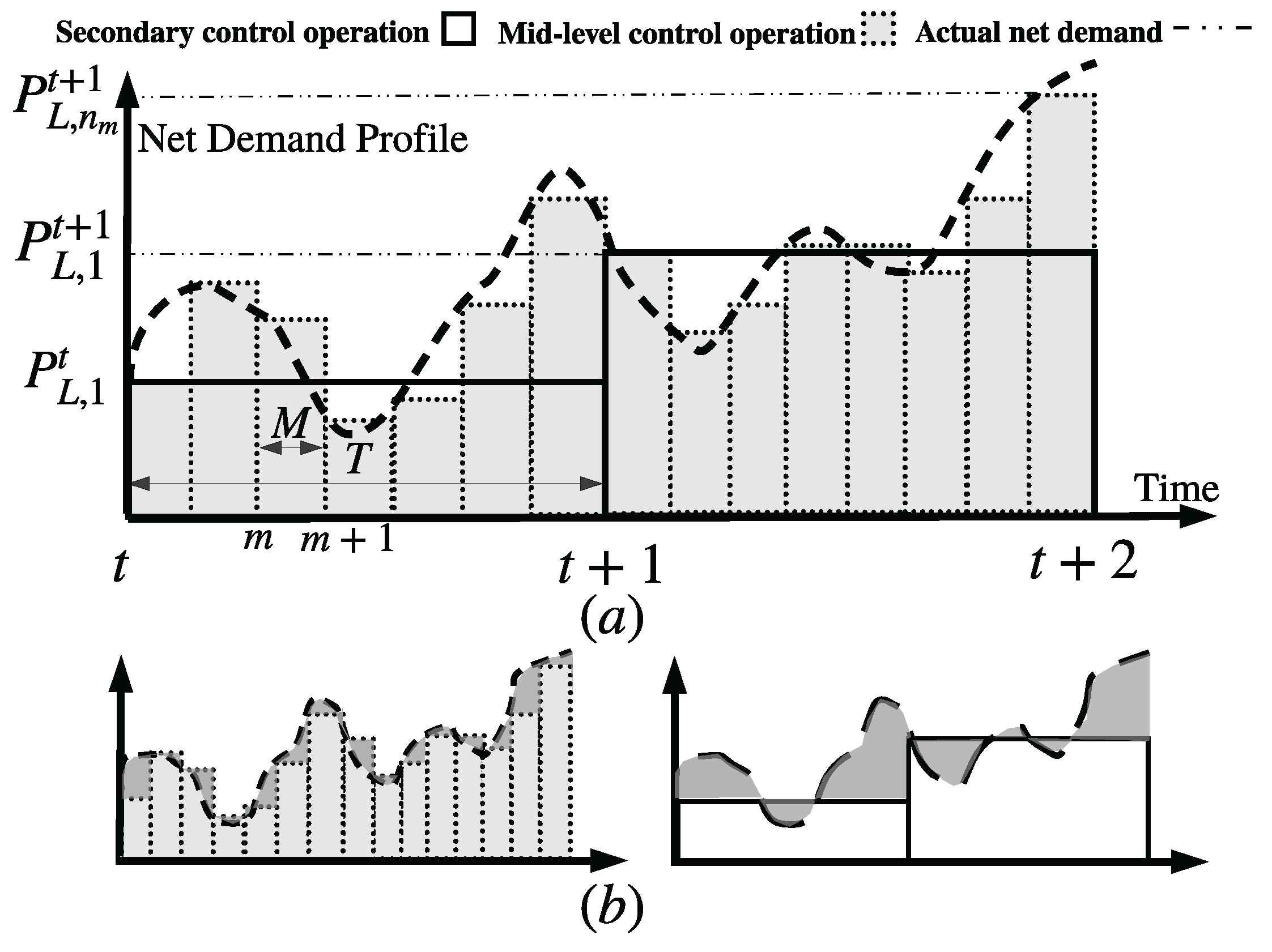

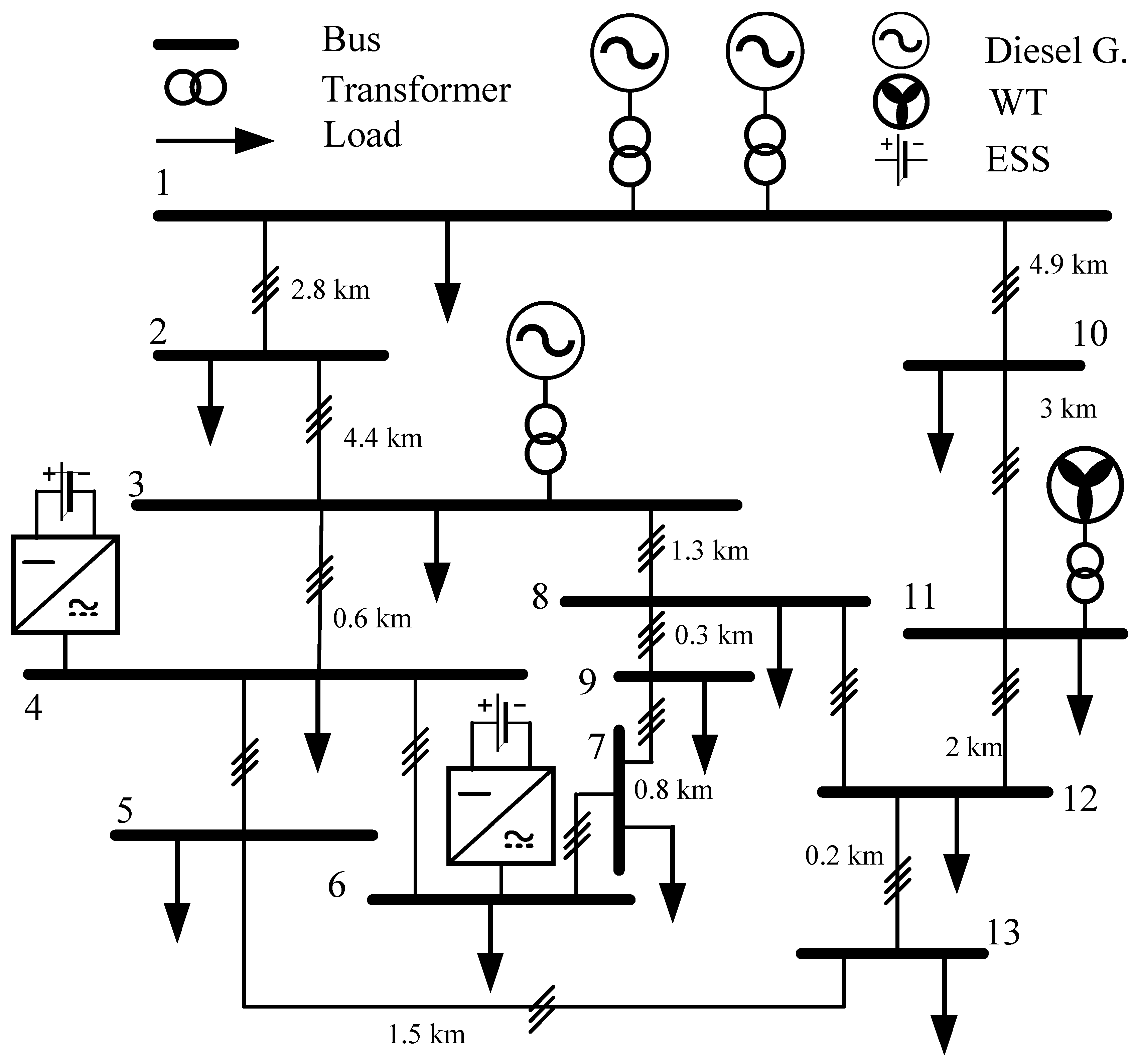

2. System Model and Problem Description

2.1. Droop Power Sharing Control

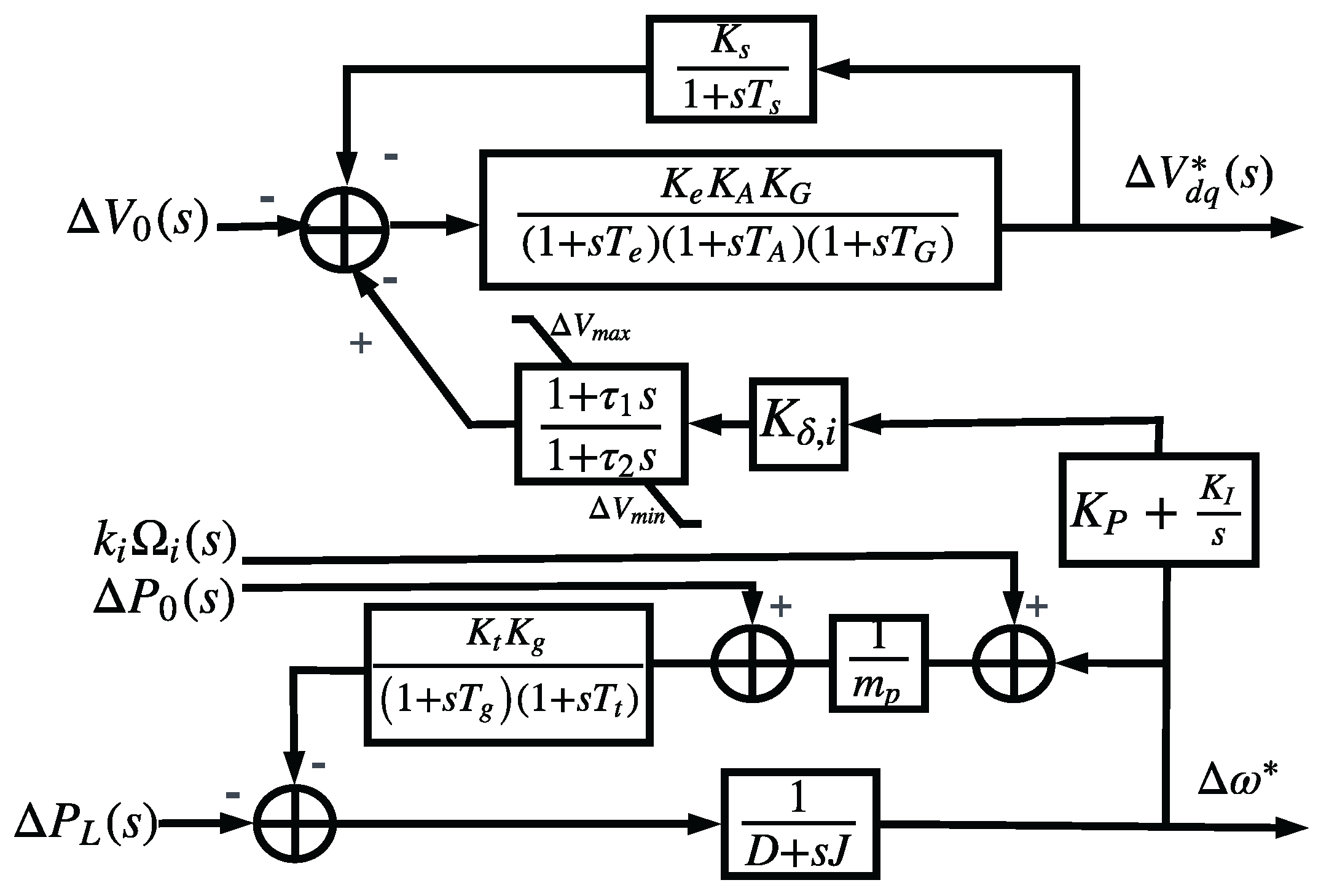

2.2. Components in Frequency and Voltage Control

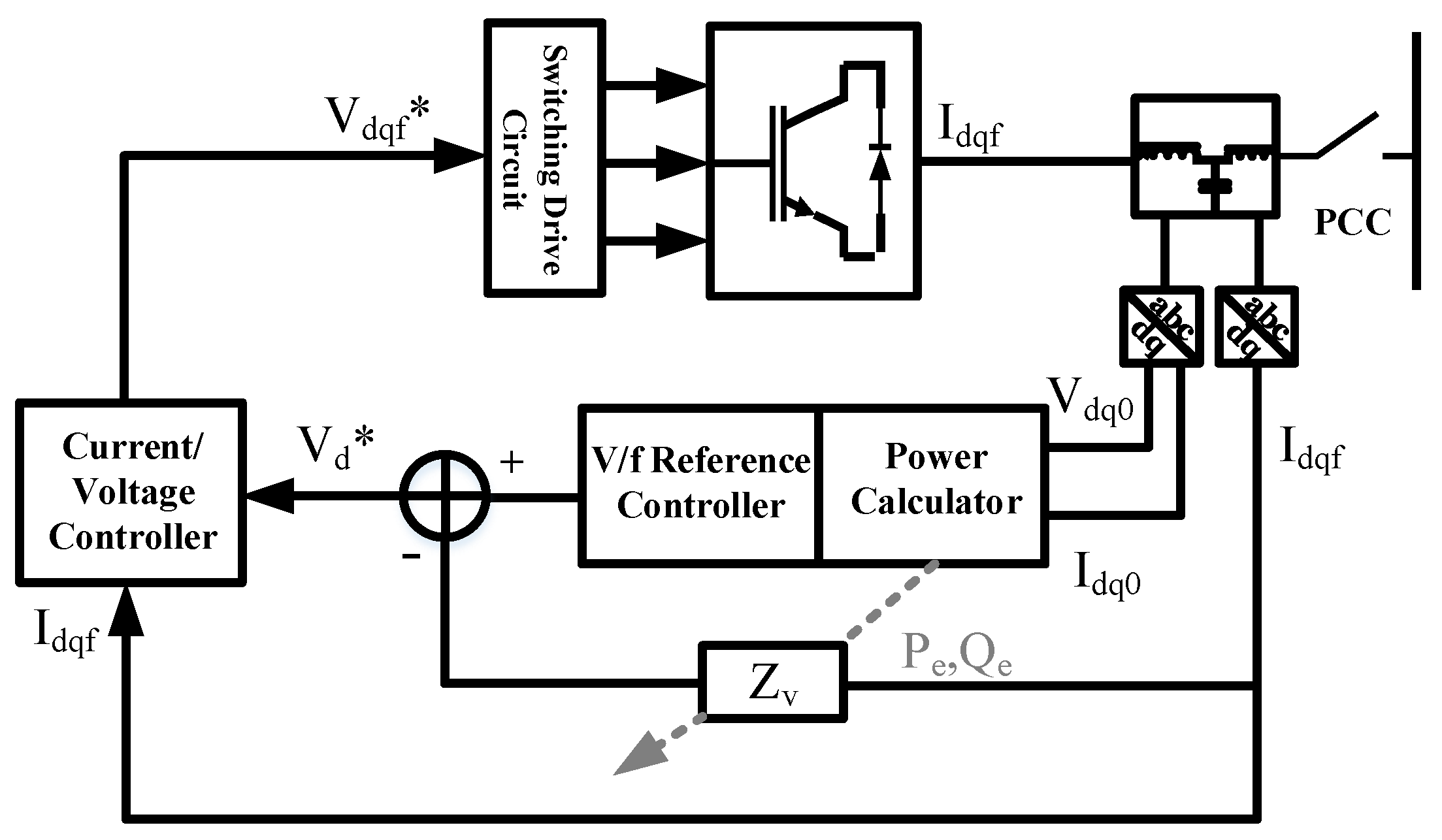

2.2.1. Inverter-Based Generators

2.2.2. Synchronous Generators

2.2.3. Frequency-Voltage Dependent Load

3. Small-Perturbation Stability Analysis

4. Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Controller

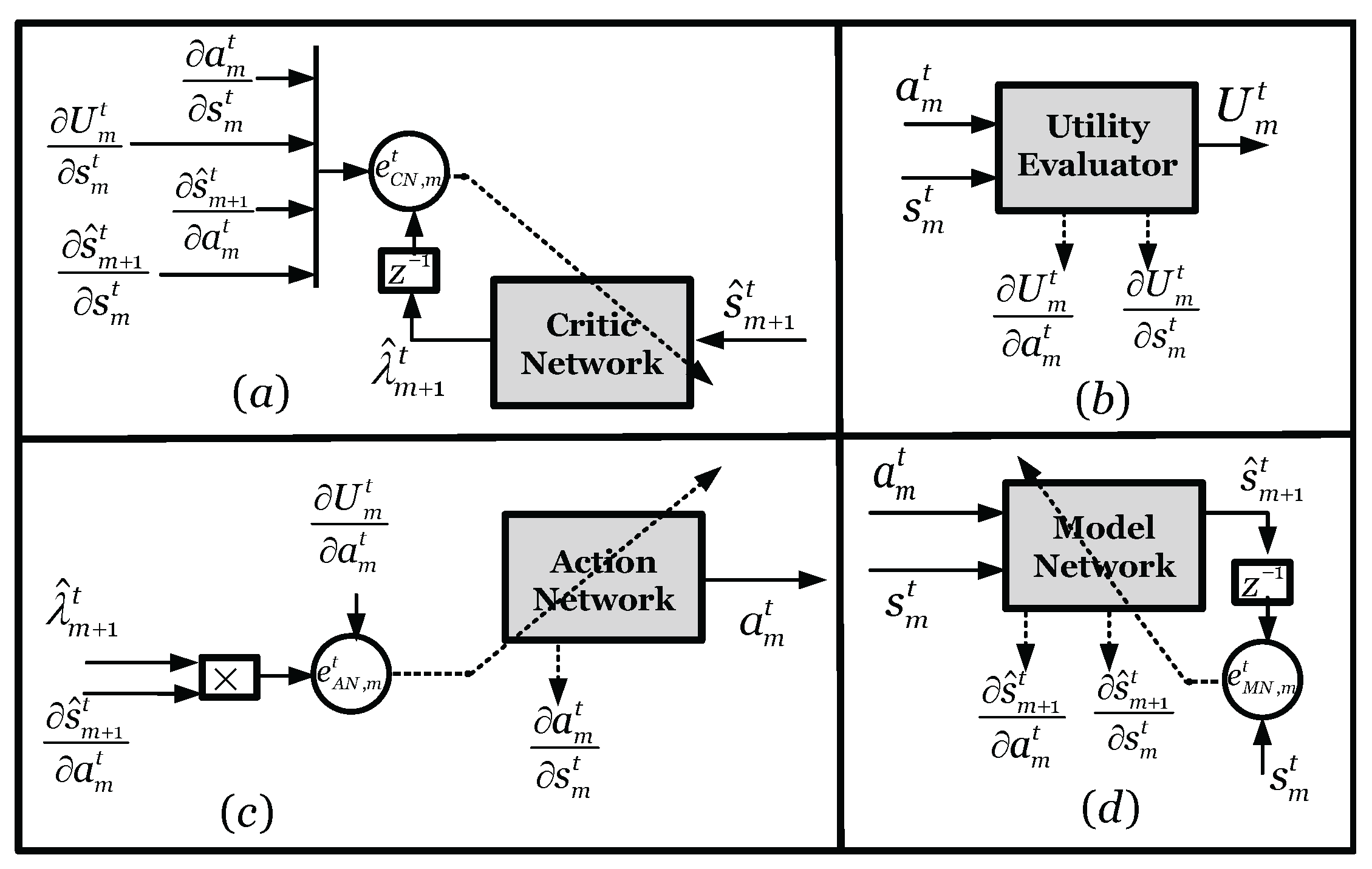

4.1. Model Network Design

4.2. Feed-Forward Critic Network Process

4.3. Action Network Design

4.4. Design and Initialization of DVFC

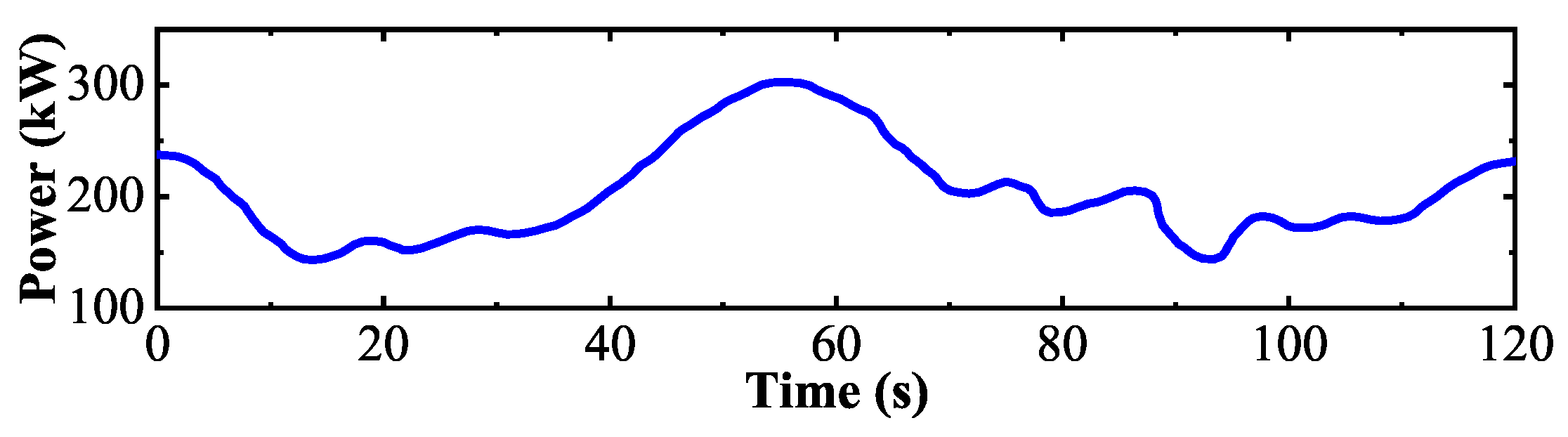

5. Numerical Results

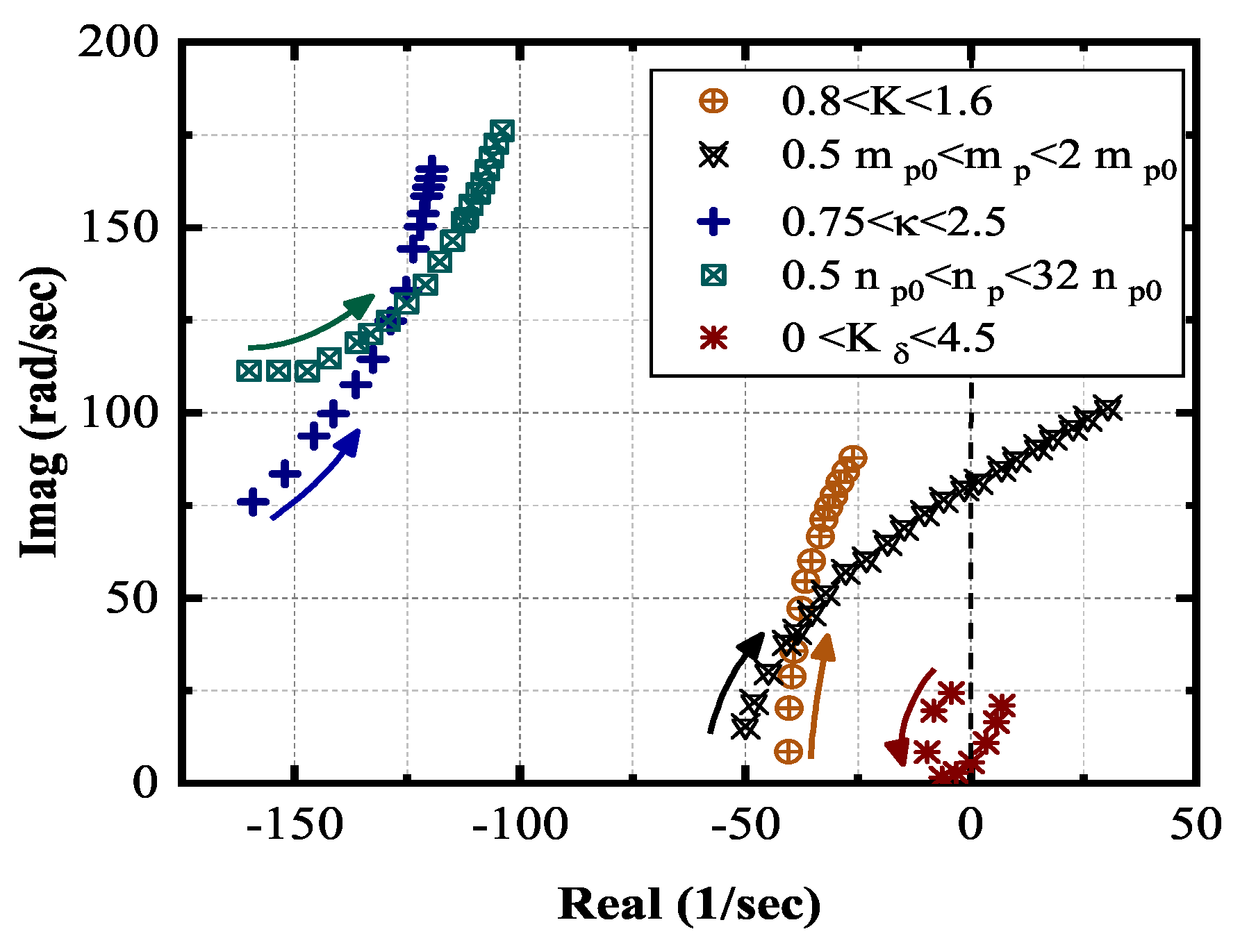

5.1. Dominant Eigenvalue Traces Versus System Parameters

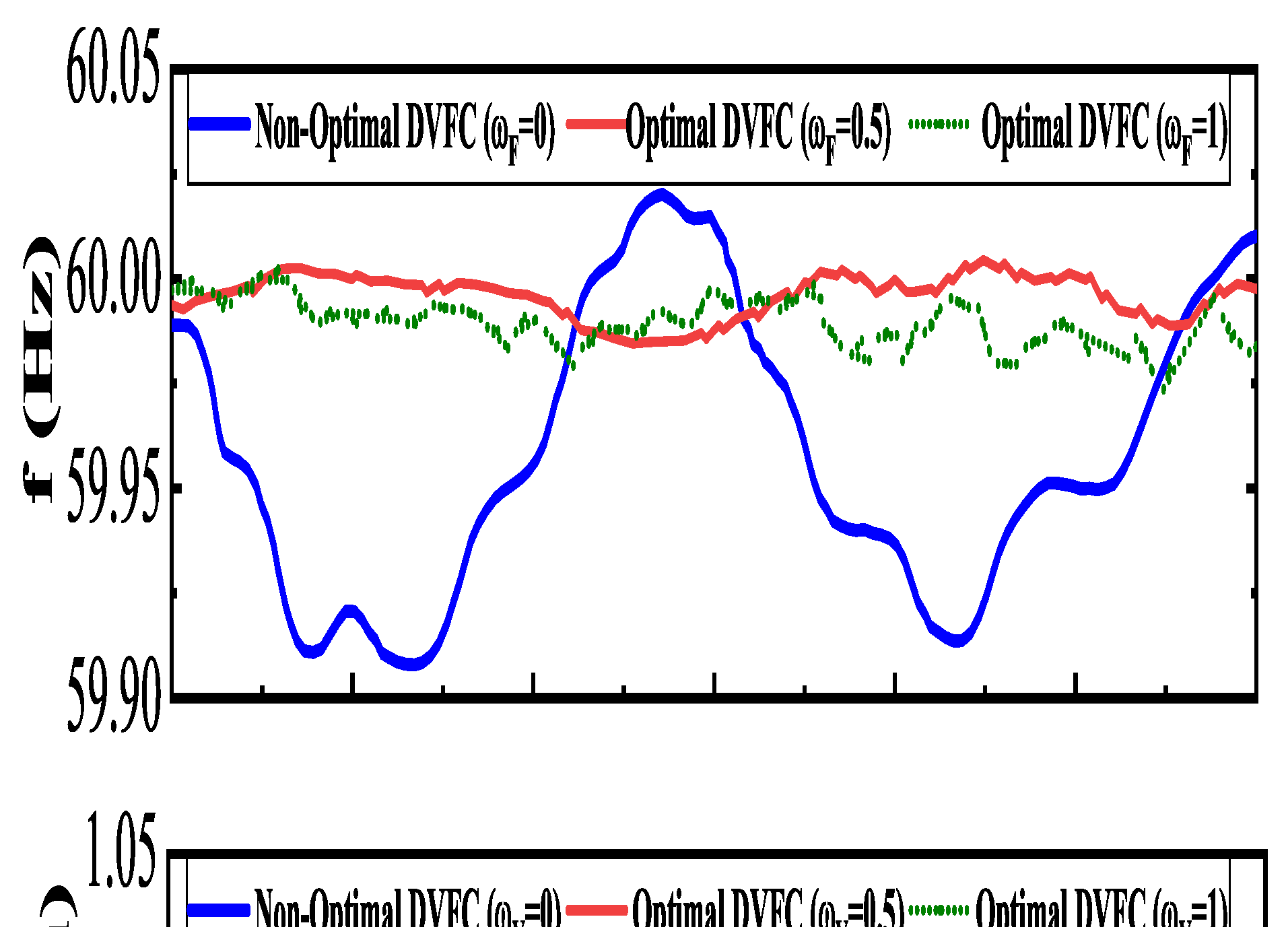

5.2. DVFC for Frequency and Voltage Regulation (Scenarios 1 and 2)

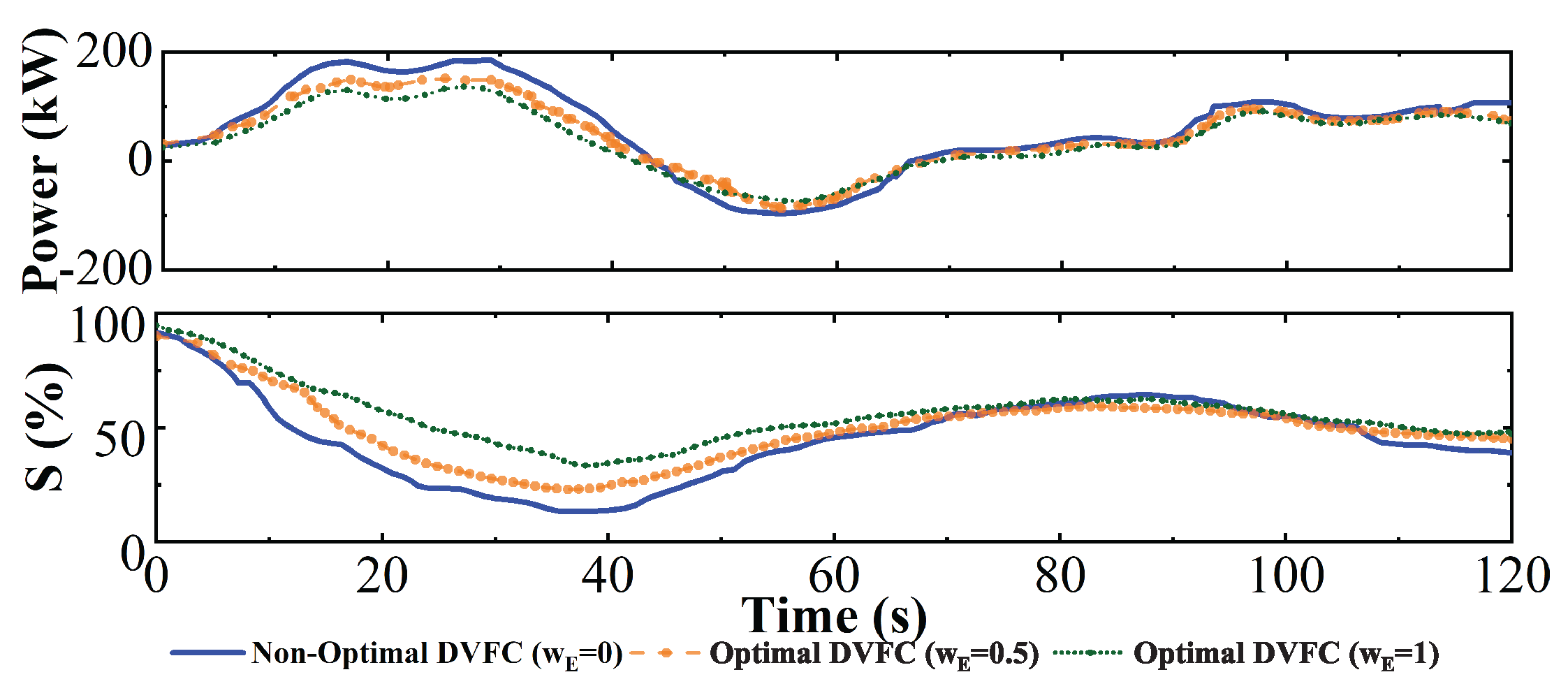

5.3. DVFC Versus ESS Penetration (Scenario 3)

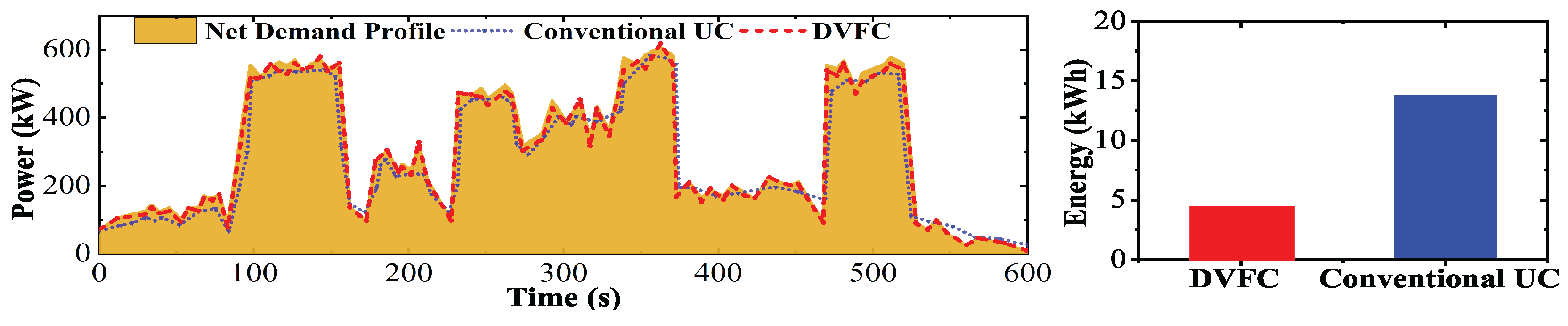

5.4. Minimum Operating Cost by DVFC (Scenario 4)

5.5. Optimum Performance of DVFC (Scenario 5)

5.6. Plug and Play Functionality of DVFC (Scenario 6)

6. Conclusion and Future Work

Abbreviations

| UC | Unit Commitment |

| DG | Distributed Generation |

| DVFC | Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Controller |

| ESS | Energy Storage System |

| SG | Synchronous Generator |

| WT | Wind Turbine |

| FVC | Frequency and Voltage Controller |

| SI | Stability Index |

| EDF | ESS-Driven Function |

| CDF | Cost-Driven Function |

References

- Ghasemi, N.; Ghanbari, M.; Ebrahimi, R. Intelligent and optimal energy management strategy to control the micro-grid voltage and frequency by considering the load dynamics and transient stability. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 145, 108618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepehrzad, R.; Hedayatnia, A.; Amohadi, M.; Ghafourian, J.; Al-Durra, A.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A. Two-stage experimental intelligent dynamic energy management of microgrid in smart cities based on demand response programs and energy storage system participation. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 155, 109613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, M.M.A.; Shaaban, M.F.; Farag, H.E.; El-Saadany, E.F. A multistage centralized control scheme for islanded microgrids with PEVs. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2014, 5, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhabadi, M.; Canizares, C.A.; Bhattacharya, K. Unit commitment for isolated microgrids considering frequency control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 9, 3270–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson-Porco, J.W.; Shafiee, Q.; Dörfler, F.; Vasquez, J.; Guerrero, J.; Bullo, F. Secondary frequency and voltage control of islanded microgrids via distributed averaging. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 7025–7038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Shafiullah, M.; Ahmed, C.B.; Alowaifeer, M. A review of microgrid energy management and control strategies. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 21729–21757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Starke, M.; Xiao, B.; Tomsovic, K. Robust optimisation-based microgrid scheduling with islanding constraints. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2017, 11, 1820–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Espana, G.; Ramos, A.; Garcia-Gonzalez, K. An MIP formulation for joint market-clearing of energy and reserves based on ramp scheduling. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2014, 29, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Xu, J.; Guo, J.; Ni, Q.; Chen, B.; Lai, L.L. Robust energy management for multi-microgrids based on distributed dynamic tube model predictive control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, M.A.; Pérez-Londoño, S.; Garcés, A. Dynamic performance evaluation of the secondary control in islanded microgrids considering frequency-dependent load models. Energies 2022, 15, 3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, A.; Gao, F.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Hu, S. Double-loop control strategy with cascaded model predictive control to improve frequency regulation for islanded microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 13, 3954–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, M.A.; Garces, A. An optimization model based on the frequency dependent power flow for the secondary control in islanded microgrids. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 97, 107617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvizimosaed, M.; Zhuang, W. Enhanced active and reactive power sharing in islanded microgrids. IEEE Syst. J. 2020, 14, 5037–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Lao, X.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; Dong, H. Dynamic event-triggered protocol-based distributed secondary control for islanded microgrids. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 137, 107723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosini, A.; Mestriner, D.; Labella, A.; Bonfiglio, A.; Procopio, R. A decentralized approach for frequency and voltage regulation in islanded PV-storage microgrids. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2021, 193, 106974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venayagamoorthy, G.K.; Sharma, R.; Gautam, P.; Ahmadi, A. Dynamic energy management system for a smart microgrid. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2016, 27, 1643–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Sanseverino, E.; Luna, A.; Dragicevic, T.; Vasquez, J.; Guerrero, J. Microgrid supervisory controllers and energy management systems: A literature review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 60, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, D.E.; et al. Trends in microgrid control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2014, 5, 1905–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, M.A.; Farag, H.E.; El-Saadany, E. Optimum reconfiguration of droop-controlled islanded microgrids. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 2144–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, H.; Michaelson, D.; Jiang, J. Accurate reactive power Sharing in an islanded microgrid using adaptive virtual impedances. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 30, 1605–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaghebi, M.; Jalilian, A.; Vasquez, J.C.; Guerrero, J.M. Autonomous voltage unbalance compensation in an islanded droop-controlled microgrid. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2013, 60, 1390–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.D.; Madani, S.S.; Karimi, A. Closed-loop data-driven modeling and distributed control for islanded microgrids with input constraints. Control Eng. Pract. 2022, 126, 105251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhabadi, M.; Canizares, C.A.; Bhattacharya, K. Frequency control in isolated/islanded microgrids through voltage regulation. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 8, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Choi, B.J.; Zhuang, W.; Shen, X. Stability enhancement of decentralized inverter control through wireless communications in microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2013, 4, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogaku, N.; Prodanovic, M.; Green, T.C. Modeling, analysis.

| Training Cycle | Model | Action | Critic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (s) | 10 | 150–250 | <200 | ∼600 |

| Algorithms | ($) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-optimal DVFC | 1877 | 1660 | 2055 | 365 |

| Optimal DVFC () | 1842 | 2140 | 1610 | 355 |

| Optimal DVFC () | 1817 | 2320 | 1455 | 351 |

| Methods | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UC(CDF) | 9.10 | 9.42 | 165.21 | 50,688 |

| UC(EDF) | 10.89 | 8.45 | 133.1 | 53,435 |

| UC(CDF+EDF) | 9.55 | 9.70 | 146.05 | 52,298 |

| DVFC | 4.42 | 6.11 | 143.13 | 51,264 |

| Parameters | UC without ESS | UC With ESS | DVFC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency Deviation (Hz) | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Voltage Deviation (p.u.) | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| ESS Utilization (kWh) | - | 4.44 | 3.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 1996 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).