Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

21 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Rationale

Methods

Search Strategy

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Screening and Selection

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

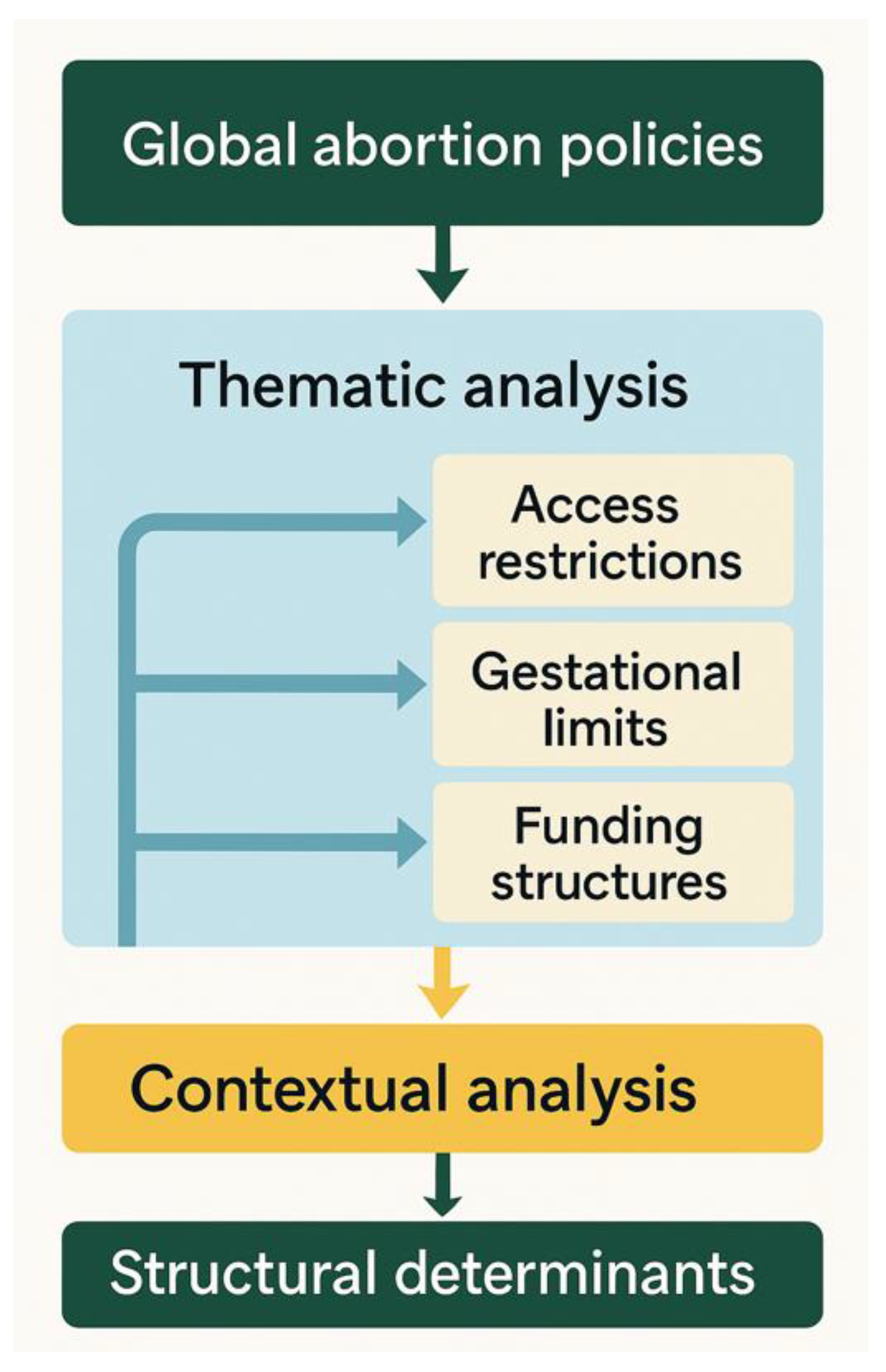

Thematic and Contextual Analysis

Synthesis and Interpretation

Results

Thematic Synthesis

Contextual Analysis

Comparative analysis by region

Northern and Western Europe

Southern Europe

Eastern and Central Europe

Nordic–Baltic Contrasts

Americas

Oceania

Africa and Humanitarian Settings

Asia–Pacific and Gulf

Abortion at a Woman’s Request

Legal Grounds for Gestational Limit

Additional Requirements for Accessing Safe Abortion Care

Conscientious Objection

Penalties

Regional Patterns with Operational Consequences

Discussion

Population Science: Implications for Global Health

Clinical Implications

Ethical and Cultural Implications

Towards Better Policy: Evidence-Informed Reform

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflicts of interest

Availability of data and material

Code availability

Author contributions

Ethics approval

Consent to participate

Consent for publication

Acknowledgements

References

- Haddadi M, Hedayati F, Hantoushzadeh S. Parallel paths: abortion access restrictions in the USA and Iran. Contracept Reprod Med [Internet]. 2025 July 25 [cited 2025 Sept 4];10(1):44. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-025-00382-3. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. www.who.int. 2022. Abortion care guideline. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240039483.

- Jerman J, Frohwirth L, Kavanaugh ML, Blades N. Barriers to Abortion Care and Their Consequences For Patients Traveling for Services: Qualitative Findings from Two States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Apr 30];49(2):95–102. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1363/psrh.12024. [CrossRef]

- Haddadi M, Sahebi L, Hedayati F, Shah IH, Parsaei M, Shariat M, et al. Induced abortion in Iran, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, the law and the diverging attitude of medical and health science students. PLOS ONE [Internet]. 2025 Mar 25 [cited 2025 Apr 22];20(3):e0320302. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0320302. [CrossRef]

- Aramesh K. Population, abortion, contraception, and the relation between biopolitics, bioethics, and biolaw in Iran. Dev World Bioeth. 2024 June;24(2):129–34. [CrossRef]

- Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Ganatra B, Moller AB, Tunçalp Ö, Beavin C, et al. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: Estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990–2019. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(9):e1152–61. [CrossRef]

- Figo [Internet]. 2022. New WHO guidelines on abortion – a landmark tool to prevent unsafe abortion | Figo. Available from: https://www.figo.org/news/new-who-guidelines-abortion-landmark-tool-prevent-unsafe-abortion.

- Major B, Beckman L, Dutton M, Russo N, West C. Mental Health and Abortion APA Task Force on Mental Health and Abortion Mark Appelbaum, PhD [Internet]. 2008. Available from: https://www.apa.org/pi/women/programs/abortion/mental-health.pdf.

- Termination Of Pregnancy Act, No. 43 [Internet]. Ministry of Health; 2019. Available from: https://www.government.is/library/04-Legislation/Termination%20of%20Pregnancy%20Act%20No%2043%202019.pdf.

- Abortion Services Aotearoa New Zealand: Annual Report 2022 [Internet]. Ministry of Health; 2022. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/2022-10/abortion-services-aotearoa-new-zealand-annual-report-2022-oct22.pdf.

- Pasieka A. The Politics of Morality. The Church, the State, and Reproductive Rights in Postsocialist Poland. By Joanna Mishtal. J Church State. 2018;60(1):139–41. [CrossRef]

- Ruibal A. Movement and counter-movement: a history of abortion law reform and the backlash in Colombia 2006–2014. Reprod Health Matters. 2014;22(44):42–51. [CrossRef]

- Joyce T, Henshaw S, Dennis A, Finer L, Blanchard K. The Impact of State Mandatory Counseling and Waiting Period Laws on Abortion: A Literature Review The Impact of State Mandatory Counseling And Waiting Period Laws on Abortion: A Literature Review [Internet]. 2009. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/pubs/MandatoryCounseling.pdf.

- The Legalization of Abortion: Law 194 of the Italian Republic, 1978 [Internet]. 1978. Available from: https://www.columbia.edu/itc/history/degrazia/courseworks/legge_194.pdf.

- White K, Narasimhan S, A. Hartwig S, Carroll E, McBrayer A, Hubbard S, et al. Parental Involvement Policies for Minors Seeking Abortion in the Southeast and Quality of Care. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2021;19. [CrossRef]

- Amnesty International [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. El Salvador’s total abortion ban sentences children and families to trauma and poverty. Available from: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2015/11/el-salvador-s-total-abortion-ban-sentences-children-and-families-to-trauma-and-poverty.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ [Internet]. 2021 Mar 29 [cited 2025 Apr 16];372:n71. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n71. [CrossRef]

- GAPD - The Global Abortion Policies Database - The Global Abortion Policies Database is designed to strengthen global efforts to eliminate unsafe abortion [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://abortion-policies.srhr.org/.

- WHO handbook for guideline development, 2nd Edition [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241548960.

- Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act 1996 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://www.saflii.org/za/legis/consol_act/cotopa1996325/.

- Renner RM, Ennis M, Kyeremeh A, Norman WV, Dunn S, Pymar H, et al. Telemedicine for First-Trimester Medical Abortion in Canada: Results of a 2019 Survey. Telemed J E-Health Off J Am Telemed Assoc. 2023 May;29(5):686–95. [CrossRef]

- Parsons JA, Romanis EC. 2020 developments in the provision of early medical abortion by telemedicine in the UK. Health Policy Amst Neth [Internet]. 2021 Jan [cited 2025 Sept 16];125(1):17–21. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8847102/. [CrossRef]

- Keefe-Oates B, Tejada CG, Zurbriggen R, Grosso B, Gerdts C. Abortion beyond 13 weeks in Argentina: healthcare seeking experiences during self-managed abortion accompanied by the Socorristas en Red. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2022 Aug 26 [cited 2025 Sept 16];19:185. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9419329/. [CrossRef]

- Australian Journal of General Practice [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Early medical abortion provision via telehealth in Victoria. Available from: https://www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2024/november/early-medical-abortion-provision-via-telehealth-in.

- Telemedicine for medical abortion: a systematic review - Endler - 2019 - BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology - Wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.15684. [CrossRef]

- Clarification on procured abortion [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_20090711_aborto-procurato_en.html.

- Impact of restrictive abortion law in Poland | 21-10-2024 | News | European Parliament [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/agenda/briefing/2024-10-21/10/impact-of-restrictive-abortion-law-in-poland.

- Commissioner for Human Rights [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Need to reform abortion law in Malta - Commissioner for Human Rights - www.coe.int. Available from: https://www.coe.int/pl/web/commissioner/country-work/malta/-/asset_publisher/TZP8peUL0wDD/content/need-to-reform-abortion-law.

- Iceland’s parliament passes landmark abortion law | EPF [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://www.epfweb.org/node/425.

- Sweden - Shhh [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://shhh-stories.com/sweden.

- Kapelańska-Pręgowska J. The Scales of the European Court of Human Rights: Abortion Restriction in Poland, the European Consensus, and the State’s Margin of Appreciation. Health Hum Rights [Internet]. 2021 Dec [cited 2025 Sept 16];23(2):213. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8694290/.

- Lov om abort (abortloven) - Lovdata [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2024-12-20-96?q=abortloven.

- Stifani BM, Vilar D, Vicente L. “Referendum on Sunday, working group on Monday”: A success story of implementing abortion services after legalization in Portugal. Int J Gynecol Obstet [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Sept 16];143(S4):31–7. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ijgo.12675. [CrossRef]

- T B, H P. Reconsidering post 20-week abortion in Aotearoa New Zealand. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol [Internet]. 2023 Oct [cited 2025 Sept 16];63(5). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37872722/.

- Information on Abortion in South Australia - SHINE SA [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://shinesa.org.au/health-information/pregnancy/information-on-abortion-in-south-australia/.

- Queensland; c=AU; o=The S of. Termination of pregnancy | Pregnancy and family planning [Internet]. corporateName=The State of Queensland; jurisdiction=Queensland; [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://www.qld.gov.au/health/children/pregnancy/termination-of-pregnancy.

- Abortion Law in Australia [Internet]. MSI Australia. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://www.msiaustralia.org.au/abortion-law-in-australia/.

- Information on Abortion in South Australia - SHINE SA [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://shinesa.org.au/health-information/pregnancy/information-on-abortion-in-south-australia/.

- Abortion legislation | Ministry of Health NZ [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/regulation-legislation/abortion/abortion-legislation.

- Recker F, Kagan KO, Maul H. Advancing knowledge and public health: a scientific exploration of abortion safety. Arch Gynecol Obstet [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sept 12];312(3):643–51. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC12374908/. [CrossRef]

- Giubilini A, Schuklenk U, Minerva F, Savulescu J. Defusing Arguments in Favour of Conscientious Objection. In: Rethinking Conscientious Objection in Health Care [Internet] [Internet]. Oxford University Press; 2025 [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK612562/.

- On conscientious objection to abortion: Questioning mandatory referral as compromise in the international human rights framework - Zoe L Tongue, 2022 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/09685332221119503. [CrossRef]

| Theme | Sub-themes | Exposures (policy levers) | Determinants | Aligned regulations/legislation | Impact |

| Legal architecture | On-request access | Typical limits 10–24 weeks (10–14 EU; 18 Sweden; 20 New Zealand; clinical standard in Canada) | Rights framing; welfare state capacity | Sweden Abortion Law 1975/2009; New Zealand Abortion Legislation Act 2020; Canada Health Act/jurisprudence | Timely early access; lower unsafe abortion; residual inequities where rural supply is thin Results Results |

| Legal architecture | Grounds-based later access | Grounds include risk to life/health, severe foetal anomaly, rape/incest; often committee-reviewed | Ethical/viability considerations; political compromise | Norway Abortion Act/Regs (amended 2021–22); Portugal Termination of Pregnancy Act 2007 | Safer later-term pathways but delays near limits from approvals Results Results |

| Gatekeeping | Third-party authorisation | Two-doctor signatures; counselling certificates; judicial orders; board approvals | Administrative culture; medico-legal risk | Germany, Slovakia, and Bulgaria commission models | Time costs, missed windows, disproportionate burden on low-income and rural users Results Results |

| Provider model | Task-sharing and scope | Midwife/nurse provision for early care; designated facilities for later procedures | Workforce distribution; rural access | South Africa Choice on TOP Act (midwife provision); Queensland/NSW reforms | Expanded throughput and reach; maintained surgical governance for complexity Results Results |

| Safe environments | Safe-access/safe-areas | 150 m protected zones; restrictions on harassment, filming | Stigma; clinic protests | New Zealand Safe Areas; NSW Public Health Amendment (Safe Access) 2018 | Reduced intimidation; improved dignity and service uptake Results Results |

| Access friction | Waiting periods | 2–7-day mandatory delays | Moralised policy tools; political bargaining | Portugal, Germany, Slovakia, Uruguay | No clinical benefit; higher logistical and financial burden Results |

| Adolescents | Parental/judicial involvement | Parental consent/notification; judicial bypass | Child protection norms; confidentiality risks | Multiple European and Latin American statutes | Delayed care; privacy risks; later-term presentations Results |

| Financing & delivery | Public funding, integration, tele-EMA | Universal coverage; mainstream hospital/primary care provision; telemedicine | Health system strength; digital readiness | Western/Northern Europe, Canada, Uruguay, UK/Argentina/Australia/NZ tele-EMA | Earlier access, fewer complications; digital access in remote areas Results |

| Criminal law | Criminalisation and penalties | Sanctions on women, providers, and assistants | Religious/political dominance; colonial legacies | Poland Constitutional Tribunal 2020; Malta Criminal Code 2023; Holy See Canon Law | Chilling effect; cross-border travel; unsafe abortion Results Results |

| Migration & status | Residency/ID controls | Residency duration; committee approvals; documentation (e.g., police reports) | Migration governance; public-order framing | UAE Cabinet Resolution 44/2024; Indonesia PP No. 28/2024 | Exclusion/delay for migrants and survivors; compressed timelines against gestational caps Results |

| Domain | Current Challenge | Proposed Improvement | Evidence Source |

| Legal structure | Inconsistent gestational limits and grounds | Standardise to WHO-aligned thresholds and explicit definitions of grounds | Quantitative cross-country data |

| Access pathways | Waiting periods, committee approvals, geographic bottlenecks | Streamline processes, decentralise care via telemedicine, and task-sharing | Mixed-methods implementation studies |

| Data and accountability | Lack of reliable reporting and outcome tracking | Mandate national-level data collection and integrate it into health system planning. | Health systems research and audits |

| Ethics and rights | Unmanaged conscientious objection, patient harassment | Enforce referral duties and establish safe-access zones | Qualitative stakeholder interviews, legal reviews |

| Cultural adaptation | Policies are misaligned with the local context. | Co-produce policies with communities to ensure acceptability and feasibility | Participatory research and community engagement |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).