Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

18 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

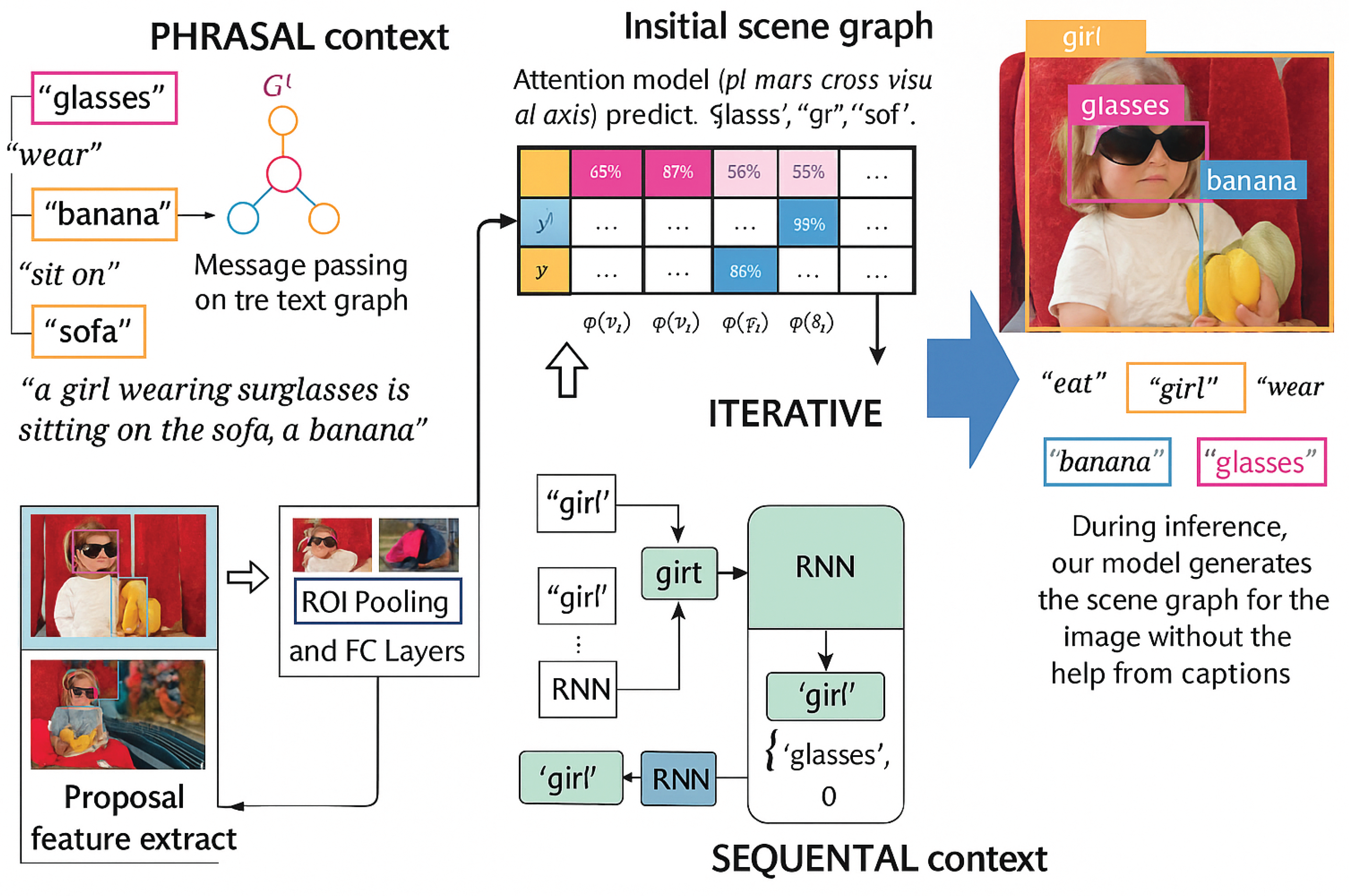

- We introduce LINGGRAPH, a novel framework for scene graph generation that leverages structured linguistic signals from captions as weak supervision.

- We propose a dual-context modeling strategy, capturing both narrative-level semantics and syntactic-level dependencies for entity disambiguation and relation grounding.

- We design an iterative refinement mechanism to progressively improve the alignment between captions and visual regions, mitigating noise inherent in weak supervision.

- We demonstrate through experiments that captions can serve as a practical and scalable alternative to annotated triplets, achieving competitive performance and semantic coherence.

2. Related Work

2.1. Textual Supervision for Structured Representation Learning

2.2. Cross-Modal Grounding and Region Alignment

2.3. Scene Graph Generation Under Different Supervision Regimes

2.4. Scaling Vision-Language Learning with Captions

2.5. Structured Language as Indirect Visual Supervision

3. Methodology

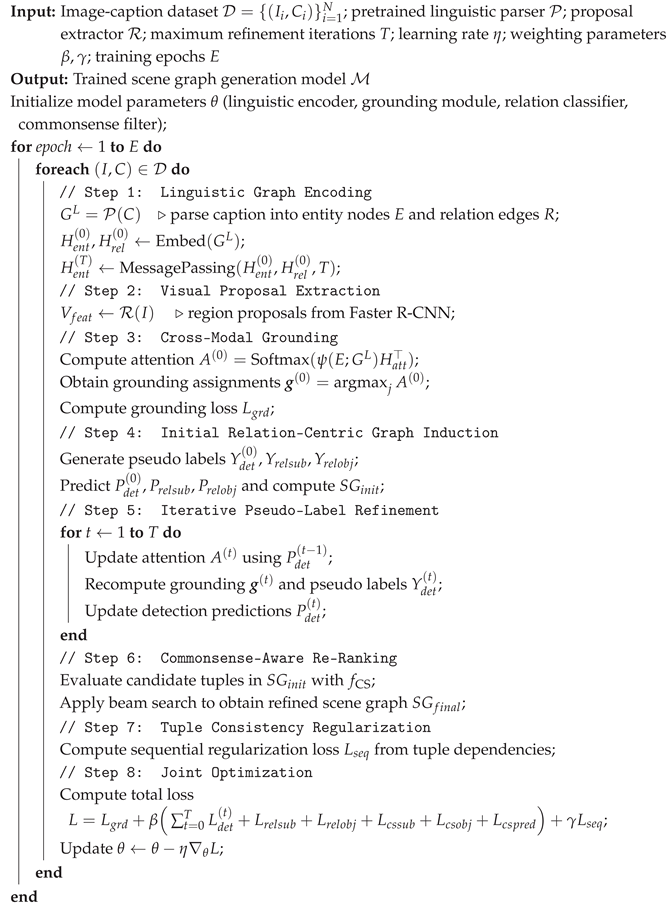

3.1. Linguistic Graph Construction and Embedding

3.2. Cross-Modal Entity Grounding with Attention

3.3. Relation-Centric Graph Induction

3.4. Iterative Refinement of Pseudo Labels

3.5. Commonsense-Guided Tuple Filtering

3.6. Regularization via Sequential Tuple Consistency

3.7. Training Objective

| Algorithm 1: Training Procedure of LINGGRAPH (Caption-Aligned Prior for Textual Supervision) |

|

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup and Datasets

4.2. Linguistic Graph Supervision Strategies

- VG-GT-Graph: Ground-truth scene graphs in VG are mapped into textual graph form by connecting object pairs with IoU > 0.5, providing a clean reference supervision.

- VG-Cap-Graph: Region-level descriptions in VG are parsed into graphs using the parser from [40], discarding bounding boxes to mimic weak textual supervision.

- COCO-Cap-Graph: Caption-level supervision from COCO is transformed similarly, offering coarser yet scalable sentence-level structures.

4.3. Evaluation Protocols and Metrics

4.4. Baselines and Ablation Variants

4.5. Results Under GT-Graph Supervision

| Zareian et al. [53] | Xu et al. [47] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | R@50 | R@100 | R@50 | R@100 |

| Weakly-supervised | ||||

| VtransE-MIL [55] | 1.53 | 2.44 | - | - |

| PPR-FCN-single [56] | 1.68 | 2.63 | - | - |

| PPR-FCN [56] | 1.83 | 2.74 | - | - |

| VSPNet [53] | 3.10 | 4.41 | 4.91 | 6.02 |

| LINGGRAPH-Basic | 2.20 | 3.32 | 3.82 | 5.10 |

| +Phrasal | 2.77 | 4.05 | 4.04 | 5.76 |

| +Iterative | 3.26 | 4.81 | 6.06 | 7.42 |

| +Sequential | 4.92 | 6.39 | 7.30 | 8.65 |

| +HA (Ours) | 5.38 | 6.85 | 7.79 | 9.12 |

| +C2F (Ours) | 5.89 | 7.42 | 8.41 | 9.96 |

| Fully-supervised | ||||

| IMP [47] | - | - | 3.44 | 4.24 |

| MotifNet [54] | - | - | 6.90 | 7.96 |

| Asso.Emb. [33] | - | - | 6.50 | 7.31 |

| MSDN [23] | - | - | 7.10 | 8.05 |

| Graph R-CNN [48] | - | - | 7.52 | 8.90 |

| VSPNet (fully-sup) [53] | - | - | 8.30 | 9.01 |

4.6. Results Under Caption-Graph Supervision

| VG-Cap-Graph | COCO-Cap-Graph | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | R@50 | R@100 | R@50 | R@100 |

| LINGGRAPH-Basic | 1.40 | 2.07 | 1.56 | 2.14 |

| +Phrasal | 1.83 | 2.49 | 1.72 | 2.36 |

| +Iterative | 2.33 | 3.02 | 2.26 | 2.97 |

| +Sequential | 3.85 | 4.86 | 3.28 | 4.31 |

| +HA (Ours) | 4.13 | 5.21 | 3.75 | 4.96 |

| +C2F (Ours) | 4.55 | 5.66 | 4.02 | 5.38 |

4.7. Ablation Studies

| Method | VG-GT-Graph | VG-Cap-Graph | COCO-Cap-Graph |

|---|---|---|---|

| LINGGRAPH-Basic | 3.82 | 1.40 | 1.56 |

| +Phrasal | 4.04 | 1.83 | 1.72 |

| +Iterative | 6.06 | 2.33 | 2.26 |

| +Sequential | 7.30 | 3.85 | 3.28 |

| +HA | 7.79 | 4.13 | 3.75 |

| +C2F | 8.41 | 4.55 | 4.02 |

4.8. Zero-Shot Generalization

4.9. Robustness and Noise Analysis

4.10. Parser Sensitivity Analysis

4.11. Qualitative Case Studies

4.12. Implementation Details

4.13. Cross-Dataset Transfer Experiments

4.14. Error Pattern Analysis

4.15. Computational Efficiency and Resource Usage

5. Conclusion

References

- Martín Abadi, Paul Barham, Jianmin Chen, Zhifeng Chen, Andy Davis, Jeffrey Dean, Matthieu Devin, Sanjay Ghemawat, Geoffrey Irving, Michael Isard, Manjunath Kudlur, Josh Levenberg, Rajat Monga, Sherry Moore, Derek G. Murray, Benoit Steiner, Paul Tucker, Vijay Vasudevan, Pete Warden, Martin Wicke, Yuan Yu, and Xiaoqiang Zheng. Tensorflow: A system for large-scale machine learning. In Proceedings of the USENIX Conference on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI), November 2016.

- Jacob Andreas, Marcus Rohrbach, Trevor Darrell, and Dan Klein. Neural module networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2016.

- Gabor Angeli, Melvin Jose Johnson Premkumar, and Christopher D. Manning. Leveraging linguistic structure for open domain information extraction. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), July 2015.

- Peter W Battaglia, Jessica B Hamrick, Victor Bapst, Alvaro Sanchez-Gonzalez, Vinicius Zambaldi, Mateusz Malinowski, Andrea Tacchetti, David Raposo, Adam Santoro, Ryan Faulkner, et al. Relational inductive biases, deep learning, and graph networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.01261, 2018.

- Hakan Bilen and Andrea Vedaldi. Weakly supervised deep detection networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2016.

- Kan Chen, Jiyang Gao, and Ram Nevatia. Knowledge aided consistency for weakly supervised phrase grounding. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2018.

- Kai Chen, Hang Song, Chen Change Loy, and Dahua Lin. Discover and learn new objects from documentaries. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), July 2017.

- Tianshui Chen, Weihao Yu, Riquan Chen, and Liang Lin. Knowledge-embedded routing network for scene graph generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2019.

- Luciano Del Corro and Rainer Gemulla. Clausie: clause-based open information extraction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW), 2013.

- Karan Desai and Justin Johnson. VirTex: Learning Visual Representations from Textual Annotations. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2021.

- Anthony Fader, Stephen Soderland, and Oren Etzioni. Identifying relations for open information extraction. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), July 2011.

- Omer Goldman, Veronica Latcinnik, Ehud Nave, Amir Globerson, and Jonathan Berant. Weakly supervised semantic parsing with abstract examples. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), July 2018.

- Jiuxiang Gu, Handong Zhao, Zhe Lin, Sheng Li, Jianfei Cai, and Mingyang Ling. Scene graph generation with external knowledge and image reconstruction. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2019.

- Max Jaderberg, Karen Simonyan, Andrew Zisserman, et al. Spatial transformer networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2015.

- Achiya Jerbi, Roei Herzig, Jonathan Berant, Gal Chechik, and Amir Globerson. Learning object detection from captions via textual scene attributes. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.14558, 2020.

- Justin Johnson, Bharath Hariharan, Laurens van der Maaten, Judy Hoffman, Li Fei-Fei, C. Lawrence Zitnick, and Ross Girshick. Inferring and executing programs for visual reasoning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Oct 2017.

- Justin Johnson, Ranjay Krishna, Michael Stark, Li-Jia Li, David Shamma, Michael Bernstein, and Li Fei-Fei. Image retrieval using scene graphs. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2015.

- Andrej Karpathy, Armand Joulin, and Li F Fei-Fei. Deep fragment embeddings for bidirectional image sentence mapping. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2014.

- Eun-Sol Kim, Woo Young Kang, Kyoung-Woon On, Yu-Jung Heo, and Byoung-Tak Zhang. Hypergraph attention networks for multimodal learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2020.

- Diederick P Kingma and Jimmy Ba. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2015.

- Ranjay Krishna, Yuke Zhu, Oliver Groth, Justin Johnson, Kenji Hata, Joshua Kravitz, Stephanie Chen, Yannis Kalantidis, Li-Jia Li, David A Shamma, et al. Visual genome: Connecting language and vision using crowdsourced dense image annotations. International Journal of Computer Vision (IJCV), 123(1), 2017. [CrossRef]

- Alina Kuznetsova, Hassan Rom, Neil Alldrin, Jasper Uijlings, Ivan Krasin, Jordi Pont-Tuset, Shahab Kamali, Stefan Popov, Matteo Malloci, Alexander Kolesnikov, et al. The open images dataset v4. International Journal of Computer Vision (IJCV), 2020.

- Yikang Li, Wanli Ouyang, Bolei Zhou, Kun Wang, and Xiaogang Wang. Scene graph generation from objects, phrases and region captions. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Oct 2017.

- Tsung-Yi Lin, Michael Maire, Serge Belongie, James Hays, Pietro Perona, Deva Ramanan, Piotr Dollár, and C Lawrence Zitnick. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2014.

- Xin Lin, Changxing Ding, Jinquan Zeng, and Dacheng Tao. Gps-net: Graph property sensing network for scene graph generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2020.

- Cewu Lu, Ranjay Krishna, Michael Bernstein, and Li Fei-Fei. Visual relationship detection with language priors. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2016.

- Jiayuan Mao, Chuang Gan, Pushmeet Kohli, Joshua B. Tenenbaum, and Jiajun Wu. The neuro-symbolic concept learner: Interpreting scenes, words, and sentences from natural supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), May 2019.

- Mausam, Michael Schmitz, Stephen Soderland, Robert Bart, and Oren Etzioni. Open language learning for information extraction. In Proceedings of the Joint Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and Computational Natural Language Learning (EMNLP-CoNLL), July 2012.

- Antoine Miech, Jean-Baptiste Alayrac, Lucas Smaira, Ivan Laptev, Josef Sivic, and Andrew Zisserman. End-to-end learning of visual representations from uncurated instructional videos. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2020.

- Antoine Miech, Dimitri Zhukov, Jean-Baptiste Alayrac, Makarand Tapaswi, Ivan Laptev, and Josef Sivic. Howto100m: Learning a text-video embedding by watching hundred million narrated video clips. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), October 2019.

- Ishan Misra, C. Lawrence Zitnick, Margaret Mitchell, and Ross Girshick. Seeing through the human reporting bias: Visual classifiers from noisy human-centric labels. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2016.

- Arsha Nagrani, Chen Sun, David Ross, Rahul Sukthankar, Cordelia Schmid, and Andrew Zisserman. Speech2action: Cross-modal supervision for action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2020.

- Alejandro Newell and Jia Deng. Pixels to graphs by associative embedding. In I. Guyon, U. V. Luxburg, S. Bengio, H. Wallach, R. Fergus, S. Vishwanathan, and R. Garnett, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2017.

- Maxime Oquab, Leon Bottou, Ivan Laptev, and Josef Sivic. Is object localization for free? - weakly-supervised learning with convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2015.

- Jeffrey Pennington, Richard Socher, and Christopher Manning. GloVe: Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Oct. 2014.

- Julia Peyre, Josef Sivic, Ivan Laptev, and Cordelia Schmid. Weakly-supervised learning of visual relations. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Oct 2017.

- Mengshi Qi, Weijian Li, Zhengyuan Yang, Yunhong Wang, and Jiebo Luo. Attentive relational networks for mapping images to scene graphs. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2019.

- Shaoqing Ren, Kaiming He, Ross Girshick, and Jian Sun. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2015.

- Anna Rohrbach, Marcus Rohrbach, Ronghang Hu, Trevor Darrell, and Bernt Schiele. Grounding of textual phrases in images by reconstruction. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2016.

- Sebastian Schuster, Ranjay Krishna, Angel Chang, Li Fei-Fei, and Christopher D. Manning. Generating semantically precise scene graphs from textual descriptions for improved image retrieval. In Workshop on Vision and Language (VL15), Sept. 2015.

- Piyush Sharma, Nan Ding, Sebastian Goodman, and Radu Soricut. Conceptual captions: A cleaned, hypernymed, image alt-text dataset for automatic image captioning. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), July 2018.

- Dídac Surís, Dave Epstein, Heng Ji, Shih-Fu Chang, and Carl Vondrick. Learning to learn words from visual scenes. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2020.

- Christian Szegedy, Sergey Ioffe, Vincent Vanhoucke, and Alexander Alemi. Inception-v4, inception-resnet and the impact of residual connections on learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), number 1, 2017.

- Peng Tang, Xinggang Wang, Xiang Bai, and Wenyu Liu. Multiple instance detection network with online instance classifier refinement. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), July 2017.

- Yu-Siang Wang, Chenxi Liu, Xiaohui Zeng, and Alan Yuille. Scene graph parsing as dependency parsing. In Proceedings of the Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (NAACL), June 2018.

- Hao Wu, Jiayuan Mao, Yufeng Zhang, Yuning Jiang, Lei Li, Weiwei Sun, and Wei-Ying Ma. Unified visual-semantic embeddings: Bridging vision and language with structured meaning representations. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2019.

- Danfei Xu, Yuke Zhu, Christopher B. Choy, and Li Fei-Fei. Scene graph generation by iterative message passing. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), July 2017.

- Jianwei Yang, Jiasen Lu, Stefan Lee, Dhruv Batra, and Devi Parikh. Graph r-cnn for scene graph generation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), September 2018.

- Alexander Yates, Michele Banko, Matthew Broadhead, Michael Cafarella, Oren Etzioni, and Stephen Soderland. TextRunner: Open information extraction on the web. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (NAACL), Apr. 2007.

- Keren Ye, Mingda Zhang, Adriana Kovashka, Wei Li, Danfeng Qin, and Jesse Berent. Cap2det: Learning to amplify weak caption supervision for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), October 2019.

- Kexin Yi, Jiajun Wu, Chuang Gan, Antonio Torralba, Pushmeet Kohli, and Josh Tenenbaum. Neural-symbolic vqa: Disentangling reasoning from vision and language understanding. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2018.

- Peter Young, Alice Lai, Micah Hodosh, and Julia Hockenmaier. From image descriptions to visual denotations: New similarity metrics for semantic inference over event descriptions. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics (TACL), 2, 2014.

- Alireza Zareian, Svebor Karaman, and Shih-Fu Chang. Weakly supervised visual semantic parsing. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2020.

- Rowan Zellers, Mark Yatskar, Sam Thomson, and Yejin Choi. Neural motifs: Scene graph parsing with global context. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2018.

- Hanwang Zhang, Zawlin Kyaw, Shih-Fu Chang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Visual translation embedding network for visual relation detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), July 2017.

- Hanwang Zhang, Zawlin Kyaw, Jinyang Yu, and Shih-Fu Chang. Ppr-fcn: Weakly supervised visual relation detection via parallel pairwise r-fcn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Oct 2017.

- Fang Zhao, Jianshu Li, Jian Zhao, and Jiashi Feng. Weakly supervised phrase localization with multi-scale anchored transformer network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2018.

- Pradeep K. Atrey, M. Anwar Hossain, Abdulmotaleb El Saddik, and Mohan S. Kankanhalli. Multimodal fusion for multimedia analysis: a survey. Multimedia Systems, 16(6):345–379, April 2010. ISSN 0942-4962.

- Meishan Zhang, Hao Fei, Bin Wang, Shengqiong Wu, Yixin Cao, Fei Li, and Min Zhang. Recognizing everything from all modalities at once: Grounded multimodal universal information extraction. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, 2024.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, and Tat-Seng Chua. Universal scene graph generation. Proceedings of the CVPR, 2025.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Jingkang Yang, Xiangtai Li, Juncheng Li, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-seng Chua. Learning 4d panoptic scene graph generation from rich 2d visual scene. Proceedings of the CVPR, 2025.

- Yaoting Wang, Shengqiong Wu, Yuecheng Zhang, Shuicheng Yan, Ziwei Liu, Jiebo Luo, and Hao Fei. Multimodal chain-of-thought reasoning: A comprehensive survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.12605, 2025. arXiv:2503.12605.

- Hao Fei, Yuan Zhou, Juncheng Li, Xiangtai Li, Qingshan Xu, Bobo Li, Shengqiong Wu, Yaoting Wang, Junbao Zhou, Jiahao Meng, Qingyu Shi, Zhiyuan Zhou, Liangtao Shi, Minghe Gao, Daoan Zhang, Zhiqi Ge, Weiming Wu, Siliang Tang, Kaihang Pan, Yaobo Ye, Haobo Yuan, Tao Zhang, Tianjie Ju, Zixiang Meng, Shilin Xu, Liyu Jia, Wentao Hu, Meng Luo, Jiebo Luo, Tat-Seng Chua, Shuicheng Yan, and Hanwang Zhang. On path to multimodal generalist: General-level and general-bench. In Proceedings of the ICML, 2025.

- Jian Li, Weiheng Lu, Hao Fei, Meng Luo, Ming Dai, Min Xia, Yizhang Jin, Zhenye Gan, Ding Qi, Chaoyou Fu, et al. A survey on benchmarks of multimodal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.08632, 2024. arXiv:2408.08632.

- Yann LeCun, Yoshua Bengio, and Geoffrey Hinton. Deep learning. Nature, 521(7553):436–444, may 2015. [CrossRef]

- Dong Yu Li Deng. Deep Learning: Methods and Applications. NOW Publishers, May 2014. URL https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/deep-learning-methods-and-applications/.

- Eric Makita and Artem Lenskiy. A movie genre prediction based on Multivariate Bernoulli model and genre correlations. (May), mar 2016. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1604.08608.

- Junhua Mao, Wei Xu, Yi Yang, Jiang Wang, and Alan L Yuille. Explain images with multimodal recurrent neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1410.1090, 2014. arXiv:1410.1090.

- Deli Pei, Huaping Liu, Yulong Liu, and Fuchun Sun. Unsupervised multimodal feature learning for semantic image segmentation. In The 2013 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), pp. 1–6. IEEE, aug 2013. ISBN 978-1-4673-6129-3. URL http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/lpdocs/epic03/wrapper.htm?arnumber=6706748.

- Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556, 2014. arXiv:1409.1556.

- Richard Socher, Milind Ganjoo, Christopher D Manning, and Andrew Ng. Zero-Shot Learning Through Cross-Modal Transfer. In C J C Burges, L Bottou, M Welling, Z Ghahramani, and K Q Weinberger (eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 26, pp. 935–943. Curran Associates, Inc., 2013. URL http://papers.nips.cc/paper/5027-zero-shot-learning-through-cross-modal-transfer.pdf.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Enhancing video-language representations with structural spatio-temporal alignment. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Karpathy and L. Fei-Fei, “Deep visual-semantic alignments for generating image descriptions,” TPAMI, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 664–676, 2017.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Retrofitting structure-aware transformer language model for end tasks. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 2151–2161, 2020.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Meishan Zhang, Yijiang Liu, Chong Teng, and Donghong Ji. Mastering the explicit opinion-role interaction: Syntax-aided neural transition system for unified opinion role labeling. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 11513–11521, 2022.

- Wenxuan Shi, Fei Li, Jingye Li, Hao Fei, and Donghong Ji. Effective token graph modeling using a novel labeling strategy for structured sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 4232–4241, 2022.

- Hao Fei, Yue Zhang, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Latent emotion memory for multi-label emotion classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 7692–7699, 2020.

- Fengqi Wang, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Jingye Li, Shengqiong Wu, Fangfang Su, Wenxuan Shi, Donghong Ji, and Bo Cai. Entity-centered cross-document relation extraction. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 9871–9881, 2022.

- Ling Zhuang, Hao Fei, and Po Hu. Knowledge-enhanced event relation extraction via event ontology prompt. Inf. Fusion, 100:101919, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Adams Wei Yu, David Dohan, Minh-Thang Luong, Rui Zhao, Kai Chen, Mohammad Norouzi, and Quoc V Le. Qanet: Combining local convolution with global self-attention for reading comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.09541, 2018. arXiv:1804.09541.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Lidong Bing, and Tat-Seng Chua. Information screening whilst exploiting! multimodal relation extraction with feature denoising and multimodal topic modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11719, 2023. arXiv:2305.11719.

- Jundong Xu, Hao Fei, Liangming Pan, Qian Liu, Mong-Li Lee, and Wynne Hsu. Faithful logical reasoning via symbolic chain-of-thought. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.18357, 2024. arXiv:2405.18357.

- Matthew Dunn, Levent Sagun, Mike Higgins, V Ugur Guney, Volkan Cirik, and Kyunghyun Cho. SearchQA: A new Q&A dataset augmented with context from a search engine. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.05179, 2017. arXiv:1704.05179.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, Bobo Li, Fei Li, Libo Qin, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Lasuie: Unifying information extraction with latent adaptive structure-aware generative language model. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2022, pages 15460–15475, 2022.

- Guang Qiu, Bing Liu, Jiajun Bu, and Chun Chen. Opinion word expansion and target extraction through double propagation. Computational linguistics, 37(1):9–27, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Yue Zhang, Donghong Ji, and Xiaohui Liang. Enriching contextualized language model from knowledge graph for biomedical information extraction. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 22(3), 2021. [CrossRef]

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Wei Ji, and Tat-Seng Chua. Cross2StrA: Unpaired cross-lingual image captioning with cross-lingual cross-modal structure-pivoted alignment. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 2593–2608, 2023.

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Tat-seng Chua, and Donghong Ji. 2024a. Multimodal emotion-cause pair extraction with holistic interaction and label constraint. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications and Applications (2024).

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Shengqiong Wu, Lizi Liao, Yinwei Wei, Tat-Seng Chua, and Donghong Ji. 2025. Revisiting conversation discourse for dialogue disentanglement. ACM Transactions on Information Systems 43, 1 (2025), 1–34. [CrossRef]

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Yuhan Wu, Jinsong Zhang, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, Yijiang Liu, Lizi Liao, Tat-Seng Chua, and Donghong Ji. 2023. DiaASQ: A Benchmark of Conversational Aspect-based Sentiment Quadruple Analysis. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023. 13449–13467.

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Lizi Liao, Yu Zhao, Fangfang Su, Fei Li, and Donghong Ji. 2024b. Harnessing holistic discourse features and triadic interaction for sentiment quadruple extraction in dialogues. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, Vol. 38. 18462–18470.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Liangming Pan, William Yang Wang, Shuicheng Yan, and Tat-Seng Chua. 2025a. Combating Multimodal LLM Hallucination via Bottom-Up Holistic Reasoning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 39. 8460–8468.

- Shengqiong Wu, Weicai Ye, Jiahao Wang, Quande Liu, Xintao Wang, Pengfei Wan, Di Zhang, Kun Gai, Shuicheng Yan, Hao Fei, et al. 2025b. Any2caption: Interpreting any condition to caption for controllable video generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.24379 (2025). arXiv:2503.24379.

- Han Zhang, Zixiang Meng, Meng Luo, Hong Han, Lizi Liao, Erik Cambria, and Hao Fei. 2025. Towards multimodal empathetic response generation: A rich text-speech-vision avatar-based benchmark. In Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025. 2872–2881.

- Yu Zhao, Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-seng Chua. 2025. Grammar induction from visual, speech and text. Artificial Intelligence 341 (2025), 104306. [CrossRef]

- Pranav Rajpurkar, Jian Zhang, Konstantin Lopyrev, and Percy Liang. Squad: 100,000+ questions for machine comprehension of text. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.05250, 2016. arXiv:1606.05250.

- Hao Fei, Fei Li, Bobo Li, and Donghong Ji. Encoder-decoder based unified semantic role labeling with label-aware syntax. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, pages 12794–12802, 2021.

- D. P. Kingma and J. Ba, “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization,” in ICLR, 2015.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Yafeng Ren, Fei Li, and Donghong Ji. Better combine them together! integrating syntactic constituency and dependency representations for semantic role labeling. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 549–559, 2021.

- K. Papineni, S. Roukos, T. Ward, and W. Zhu, “Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation,” in ACL, 2002, pp. 311–318.

- Hao Fei, Bobo Li, Qian Liu, Lidong Bing, Fei Li, and Tat-Seng Chua. Reasoning implicit sentiment with chain-of-thought prompting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11255, 2023. arXiv:2305.11255.

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 4171–4186, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics. URL https://aclanthology.org/N19-1423.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Leigang Qu, Wei Ji, and Tat-Seng Chua. Next-gpt: Any-to-any multimodal llm. CoRR, abs/2309.05519, 2023.

- Qimai Li, Zhichao Han, and Xiao-Ming Wu. Deeper insights into graph convolutional networks for semi-supervised learning. In Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2018.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Wei Ji, Hanwang Zhang, Meishan Zhang, Mong-Li Lee, and Wynne Hsu. Video-of-thought: Step-by-step video reasoning from perception to cognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2024.

- Naman Jain, Pranjali Jain, Pratik Kayal, Jayakrishna Sahit, Soham Pachpande, Jayesh Choudhari, et al. Agribot: agriculture-specific question answer system. IndiaRxiv, 2019.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Wei Ji, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Dysen-vdm: Empowering dynamics-aware text-to-video diffusion with llms. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pages 7641–7653, 2024.

- Mihir Momaya, Anjnya Khanna, Jessica Sadavarte, and Manoj Sankhe. Krushi–the farmer chatbot. In 2021 International Conference on Communication information and Computing Technology (ICCICT), pages 1–6. IEEE, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Fei Li, Chenliang Li, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, and Donghong Ji. Inheriting the wisdom of predecessors: A multiplex cascade framework for unified aspect-based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI, pages 4096–4103, 2022.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Donghong Ji, and Jingye Li. Learn from syntax: Improving pair-wise aspect and opinion terms extraction with rich syntactic knowledge. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 3957–3963, 2021.

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Lizi Liao, Yu Zhao, Chong Teng, Tat-Seng Chua, Donghong Ji, and Fei Li. Revisiting disentanglement and fusion on modality and context in conversational multimodal emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM, pages 5923–5934, 2023.

- Hao Fei, Qian Liu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Scene graph as pivoting: Inference-time image-free unsupervised multimodal machine translation with visual scene hallucination. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 5980–5994, 2023.

- S. Banerjee and A. Lavie, “METEOR: an automatic metric for MT evaluation with improved correlation with human judgments,” in IEEMMT, 2005, pp. 65–72.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Hanwang Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Vitron: A unified pixel-level vision llm for understanding, generating, segmenting, editing. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2024,, 2024.

- Abbott Chen and Chai Liu. Intelligent commerce facilitates education technology: The platform and chatbot for the taiwan agriculture service. International Journal of e-Education, e-Business, e-Management and e-Learning, 11:1–10, 01 2021. [CrossRef]

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Xiangtai Li, Jiayi Ji, Hanwang Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Towards semantic equivalence of tokenization in multimodal llm. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.05127, 2024. arXiv:2406.05127.

- Jingye Li, Kang Xu, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. MRN: A locally and globally mention-based reasoning network for document-level relation extraction. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 1359–1370, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Yafeng Ren, and Meishan Zhang. Matching structure for dual learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML, pages 6373–6391, 2022.

- Hu Cao, Jingye Li, Fangfang Su, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Bobo Li, Liang Zhao, and Donghong Ji. OneEE: A one-stage framework for fast overlapping and nested event extraction. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 1953–1964, 2022.

- Isakwisa Gaddy Tende, Kentaro Aburada, Hisaaki Yamaba, Tetsuro Katayama, and Naonobu Okazaki. Proposal for a crop protection information system for rural farmers in tanzania. Agronomy, 11(12):2411, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Boundaries and edges rethinking: An end-to-end neural model for overlapping entity relation extraction. Information Processing & Management, 57(6):102311, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jingye Li, Hao Fei, Jiang Liu, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Chong Teng, Donghong Ji, and Fei Li. Unified named entity recognition as word-word relation classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 10965–10973, 2022.

- Mohit Jain, Pratyush Kumar, Ishita Bhansali, Q Vera Liao, Khai Truong, and Shwetak Patel. Farmchat: a conversational agent to answer farmer queries. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, 2(4):1–22, 2018.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Imagine that! abstract-to-intricate text-to-image synthesis with scene graph hallucination diffusion. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 79240–79259, 2023.

- P. Anderson, B. Fernando, M. Johnson, and S. Gould, “SPICE: semantic propositional image caption evaluation,” in ECCV, 2016, pp. 382–398.

- Hao Fei, Tat-Seng Chua, Chenliang Li, Donghong Ji, Meishan Zhang, and Yafeng Ren. On the robustness of aspect-based sentiment analysis: Rethinking model, data, and training. ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 41(2):50:1–50:32, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yu Zhao, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Bobo Li, Meishan Zhang, Jianguo Wei, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Constructing holistic spatio-temporal scene graph for video semantic role labeling. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM, pages 5281–5291, 2023.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Lidong Bing, and Tat-Seng Chua. Information screening whilst exploiting! multimodal relation extraction with feature denoising and multimodal topic modeling. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 14734–14751, 2023.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Yue Zhang, and Donghong Ji. Nonautoregressive encoder-decoder neural framework for end-to-end aspect-based sentiment triplet extraction. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 34(9):5544–5556, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kelvin Xu, Jimmy Ba, Ryan Kiros, Kyunghyun Cho, Aaron Courville, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, Richard S Zemel, and Yoshua Bengio. Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention. arXiv preprint arXiv:1502.03044, 2(3):5, 2015. arXiv:1502.03044.

- Seniha Esen Yuksel, Joseph N Wilson, and Paul D Gader. Twenty years of mixture of experts. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems, 23(8):1177–1193, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Sanjeev Arora, Yingyu Liang, and Tengyu Ma. A simple but tough-to-beat baseline for sentence embeddings. In ICLR, 2017.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).