Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: Abortion is a core component of reproductive healthcare and a critical determinant of maternal health outcomes. Globally, approximately 73 million abortions occur annually, with unsafe abortion contributing to 4.7–13.2% of maternal deaths, primarily in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Legal frameworks governing abortion vary widely, ranging from total prohibition to fully integrated care systems. Access is further shaped by health system capacity, procedural barriers, and socio-economic inequities. In an increasingly globalised world, migration adds complexity, as individuals move between countries with differing policies, influencing both direct access to care and regional healthcare dynamics. Understanding these intersecting factors is essential for improving reproductive health equity and reducing preventable morbidity and mortality. Methods: A global comparative analysis was conducted using two integrated datasets covering 100 countries. The first dataset captured legal, operational, and contextual variables, including gestational limits, funding mechanisms, provider cadres, and telemedicine availability. The second dataset provided demographic, socio-economic, and health system indicators. Access Scores were derived from weighted indicators on a 0–10 scale. Analyses included descriptive statistics, bivariate associations, and multivariable ordinal logistic regression. An intersectional approach explored disparities across income groups, geographic regions, and migration pathways, with visualisation tools such as heatmaps, bubble plots, and diaspora exposure differentials. Results: Countries with telemedicine-enabled early medical abortion (tele-EMA) were significantly associated with higher Access Scores (OR ≈1.45), while each additional mandated waiting day reduced odds of liberal access by 7%. Mid-level provider authorisation and public funding alone did not predict improved access. Migration analysis revealed that LMIC-to-HIC flows resulted in marked improvements in abortion access, though benefits were unevenly distributed, leaving vulnerable populations behind. African and Asian LMICs had the lowest Access Scores, reflecting systemic underfunding and restrictive laws. Conclusion: Abortion access is shaped by functional health system design rather than geography alone. Removing procedural barriers, expanding telemedicine, and embedding services within integrated health systems are essential to achieving equitable, sustainable reproductive healthcare worldwide.

Keywords:

Background

Rationale

Methods

Data Sources

- Legislative framework – gestational limits, grounds for abortion, approval requirements, conscientious objection, penalties, and reporting obligations.

- Service delivery and practice – provider cadres, facility designations, telemedicine availability, safe-access zones, and public funding mechanisms.

- Determinants and contextual variables – GDP per capita, gender inequality index, religious composition, urbanisation, and health system readiness indicators.

- Health outcomes – maternal mortality ratio, proportion of abortions performed safely, and prevalence of cross-border care.

Variables and Coding

- 0 – Prohibition where life-saving exception only

- 1 – Highly restrictive limited grounds where life, health, rape, foetal anomaly

- 2 – Moderate access where grounds plus socio-economic criteria

- 3 – Broad access on-request up to specified gestation

- 4 – Fully integrated care on-request with minimal barriers and national standardisation

Intersectionality Analysis

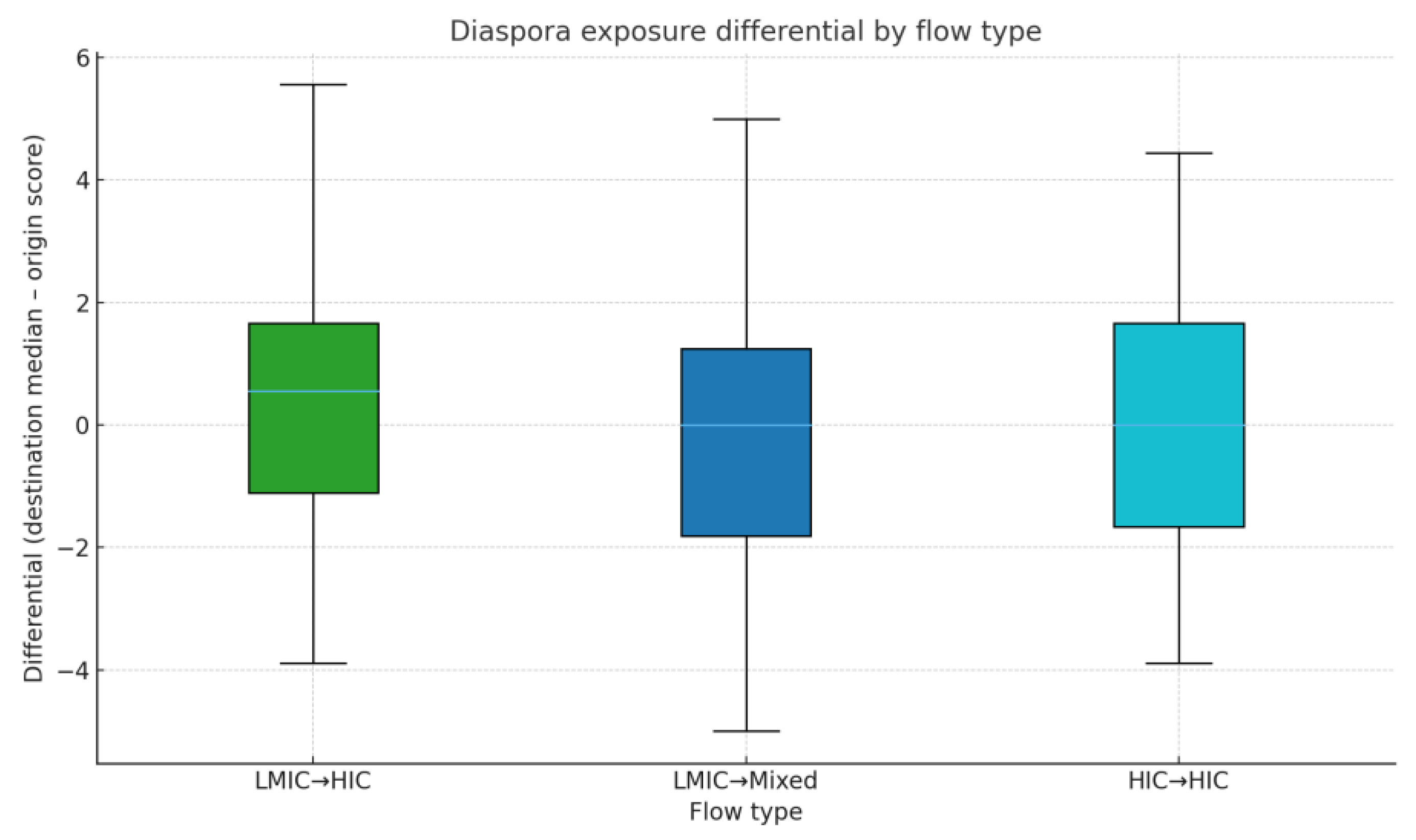

- Stage-1 was a stratified descriptive statistics were used to compare Access Scores across intersecting strata of income group and region.

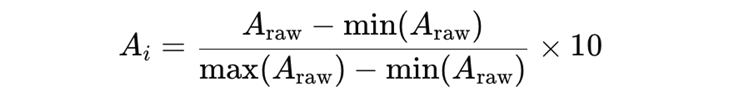

- LL = legal model score (e.g., prohibition = 0, grounds-based = 1, on request = 3)

- FF = funding level (public funding = 2, limited funding = -1)

- TT = telemedicine availability (available = 1, not available = 0)

- RR = referral duties for conscientious objection (explicit duty = 1, weak duty = -0.5)

- PP = provider care breadth (multi-cadre = 1, doctors only = -0.5)

- BB = third-party authorisation requirements (none = 1, two or more sign-offs = -0.5)

- WW = waiting period adjustment (no waiting period = 0, 2–3 days = -0.5, >3 days = -1)

- SS = safe-access zone protection (present = 0.5, none = 0)

- 2.

- Stage-2 was a cross-tabulations and visualisations explored how access patterns differed when income group, geographic region, and migration flow type were combined.

- R = geographic region (e.g., Africa, Asia)

- I = income group (HIC or LMIC)

- n = number of countries in that subgroup.

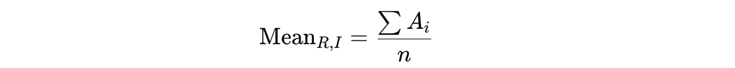

- Heatmaps – showing patterns of Access Scores by region and income group.

- Bubble plots – where the x-axis represented region, the y-axis represented mean Access Score, bubble size reflected the number of countries, and colour indicated income group.

- 3.

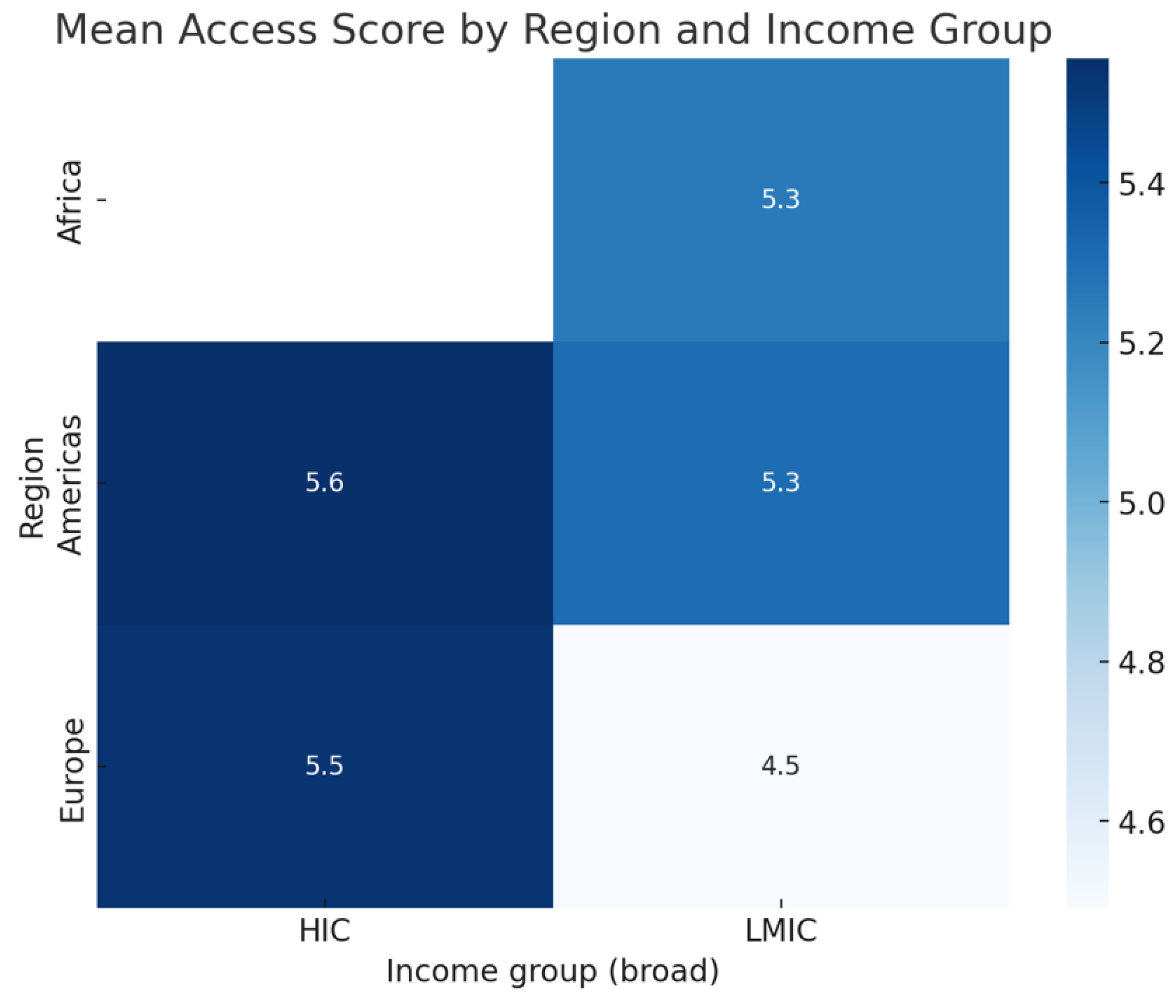

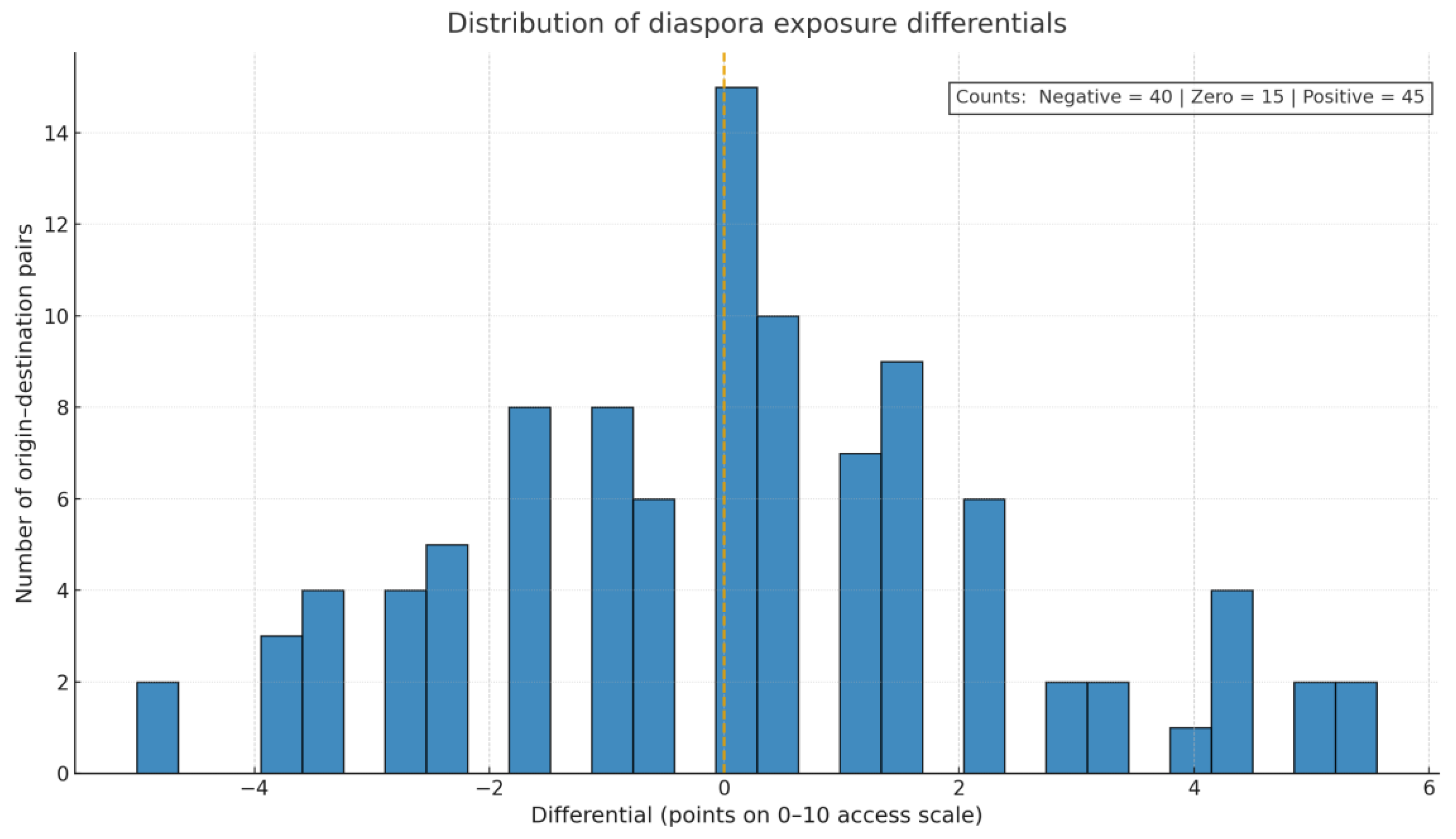

- Stage-3 Migration pathway analysis examined diaspora flows using boxplots and histograms to show how migration influenced abortion access.

- Adest_median = median Access Score of the destination region

- Aorigin = Access Score of origin country

Results

Descriptive and Distributional Findings

Bivariate Associations (Availability and Practice)

Multivariable Modelling (Policy Architecture as an Ordered Outcome)

Determinants-Based Analysis (From Your Variables)

Determinant: Telemedicine Policy

Determinant: Waiting Period Days

Determinant: Mid-Level Authorisation

Determinant: Public Funding

Determinant: Conscientious Objection and Referral Duty (Contextual)

Regional Structure (Contextual)

Robustness and Limitations

Determinants-Based Analysis

Telemedicine Policy

Waiting Period Days

Mid-Level Authorisation

Public Funding

Conscientious Objection and Referral Duty

Regional Contextualisation

Robustness and Limitations

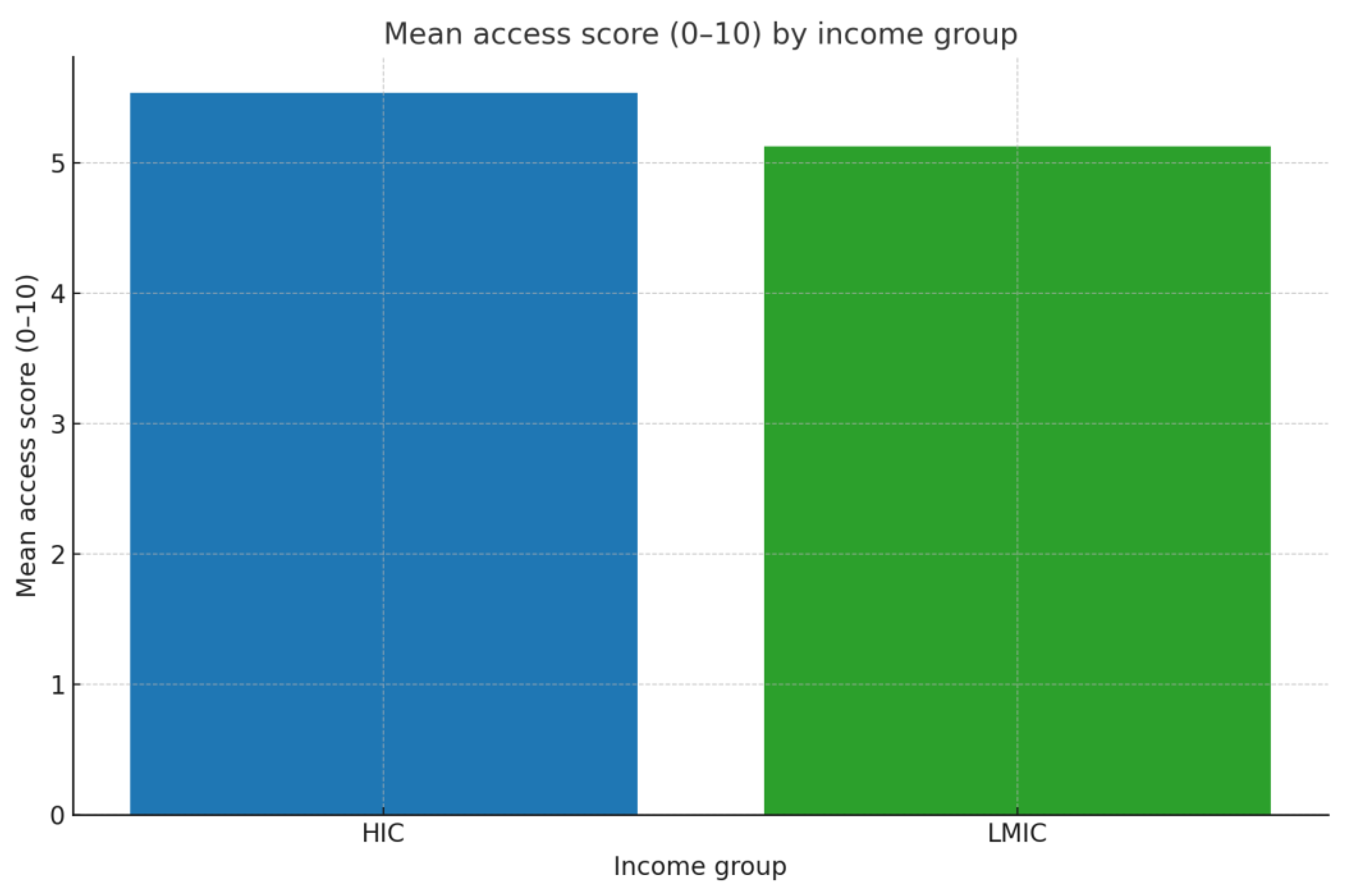

Access Score Disparities by Income Group and Region

- The mean Access Score in HICs was 5.6, reflecting liberal legal frameworks, strong public funding, and broad availability of services.

- In LMICs, the mean score was 4.7, indicating restrictive environments with limited funding and systemic barriers.

Heatmap: Intersection of Income Group and Region

Migration Pathways and Diaspora Exposure

Region and Income Group Interaction

Intersectional Findings

Discussion

Clinical Implications

Geopolitical Implications

Population Science and Sustainability

Conclusion

Code Availability

Ethics approval

Consent to participate

Consent for publication

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abortion care guideline [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240039483.

- Abortion [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/abortion.

- Reasons, U.S. Women Have Abortions: Quantitative and Qualitative Perspectives | Guttmacher Institute [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/journals/psrh/2005/reasons-us-women-have-abortions-quantitative-and-qualitative-perspectives. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Alipanahpour S, Tayebi N, Taheri M, Akbarzadeh M. Causes of Different Types of Abortion in Women Referring To Educational and Medical Centers in Shiraz, Iran. Journal of Midwifery and Reproductive Health [Internet]. 2021 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Sept 16];9(4):3034–42. Available from: https://jmrh.mums.ac.ir/article_18888.html.

- Chae S, Desai S, Crowell M, Sedgh G. Reasons why women have induced abortions: a synthesis of findings from 14 countries. Contraception [Internet]. 2017 Oct [cited 2025 Sept 16];96(4):233–41. [CrossRef]

- Basile KC, Smith SG, Liu Y, Kresnow M jo, Fasula AM, Gilbert L, et al. Rape-Related Pregnancy and Association With Reproductive Coercion in the U.S. Am J Prev Med [Internet]. 2018 Dec [cited 2025 Sept 16];55(6):770–6. [CrossRef]

- A Pregnancy Decision-Making Model: Psychological, Relational, and Cultural Factors Affecting Unintended Pregnancy - Elyssa M. Klann, Y. Joel Wong, 2020 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran S, Key K, Ow A, Lindsey A, Chin J, Goode B, et al. The role of community and culture in abortion perceptions, decisions, and experiences among Asian Americans. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Jan 17 [cited 2025 Sept 12];10:982215. [CrossRef]

- Recker F, Kagan KO, Maul H. Advancing knowledge and public health: a scientific exploration of abortion safety. Arch Gynecol Obstet [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sept 12];312(3):643–51. [CrossRef]

- Haddadi M, Hedayati F, Hantoushzadeh S. Parallel paths: abortion access restrictions in the USA and Iran. Contracept Reprod Med [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sept 4];10(1):44. 25 July. [CrossRef]

- Afsana, Alam T, Mateena Y. The hidden crisis: unsafe abortion and the fight for women’s health. International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology [Internet]. 2024 Nov 28 [cited 2025 Sept 16];13(12):3608–15. [CrossRef]

- Aramesh, K. Population, abortion, contraception, and the relation between biopolitics, bioethics, and biolaw in Iran. Dev World Bioeth. 2024 June;24(2):129–34. [CrossRef]

- Dickman SL, White K, Sierra G, Grossman D. Financial Hardships Caused by Out-of-Pocket Abortion Costs in Texas, 2018. American Journal of Public Health [Internet]. 2022 May [cited 2025 Sept 16];112(5):758. [CrossRef]

- Grossman D, Grindlay K, Burns B. Public funding for abortion where broadly legal. Contraception. 2016 Nov;94(5):453–60. [CrossRef]

- Wubetu AT, Munea AM, Balcha WF, Chekole FA, Nega AT, Getu AA, et al. Health care providers attitude towards safe abortion care and its associated factors in Northwest, Ethiopia, 2021: a health facility-based cross-sectional study. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Sept 16];21:83. 8 June. [CrossRef]

- Supply I of M (US) C on the USP, Lohr KN, Vanselow NA, Detmer DE. Relationship of Physician Supply to Key Elements of the Health Care System. In: The Nation’s Physician Workforce: Options for Balancing Supply and Requirements [Internet]. National Academies Press (US); 1996 [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 2325.

- Leung SY, Ku HB. Cross-border healthcare-seeking and utilization behaviours among ethnic minorities: exploring the nexus of the perceived better option and public health concerns. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Sept 16];24(1):1497. 4 June. [CrossRef]

- Berer, M. Abortion Law and Policy Around the World. Health Hum Rights [Internet]. 2017 June [cited 2025 Sept 16];19(1):13–27. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 5473. [Google Scholar]

- GAPD - The Global Abortion Policies Database - The Global Abortion Policies Database is designed to strengthen global efforts to eliminate unsafe abortion [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://abortion-policies.srhr.

- Milner A, Kavanagh A, Scovelle AJ, O’Neil A, Kalb G, Hewitt B, et al. Gender Equality and Health in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review of Within-Country Indicators of Gender Equality in Relation to Health Outcomes. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle) [Internet]. 2021 Apr 27 [cited 2025 Sept 16];2(1):113–23. [CrossRef]

- The Broad Benefits of Investing in Sexual and Reproductive Health | Guttmacher Institute [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher. 2004.

- Kramer A, Ti A, Travis L, Laboe A, Ochieng WO, Young MR. The impact of parental involvement laws on minors seeking abortion services: a systematic review. Health Aff Sch [Internet]. 2023 Sept 18 [cited 2025 Sept 12];1(4):qxad045. [CrossRef]

- National Guideline Alliance (UK). Accessibility and sustainability of abortion services: Abortion care: Evidence review A [Internet]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2019 [cited 2025 Sept 16]. (NICE Evidence Reviews Collection). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK561116/.

- Jerman J, Frohwirth L, Kavanaugh ML, Blades N. Barriers to Abortion Care and Their Consequences For Patients Traveling for Services: Qualitative Findings from Two States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Apr 30];49(2):95–102. [CrossRef]

- Stover J, Hardee K, Ganatra B, García Moreno C, Horton S. Interventions to Improve Reproductive Health. In: Black RE, Laxminarayan R, Temmerman M, Walker N, editors. Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health: Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 2) [Internet]. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; 2016 [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK361913/.

- THE 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development [Internet]. [cited 2025 ]. Available from: https://sdgs.un.org/goals. 21 May.

| Study ID | Policy/ articles name | Year | Policy Level | Country/Region | Policy Focused Area | Targeted Population | Policy Status | Objective | Outcomes | Equity Consideration | Global Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abortion Law Reform Act 2019 | 2019 | State | Australia | Legal framework for terminations | Pregnant persons / patients & registered health practitioners | Implemented | Reform abortion law and regulate practitioner conduct | Termination on request ≤22 weeks; >22 weeks with specialist approvals; counselling info; decriminalises self-termination; facility approvals and guidelines | Conscientious objection duties; info provision about services/counselling | Partial alignment with WHO Abortion care guideline (2022) |

| 2 | Abortion Law Reform Amendment (Health Care Access) Bill 2025 (NSW) – Explanatory Note | 2025 | State | Australia | Duty to ensure services statewide; expand who may perform ≤22 weeks | Patients seeking abortion; broader cadre of practitioners | Proposed | Increase access to abortion health care across NSW | Minister must ensure reasonable-distance access & public info; wider workforce authorised; mandatory transfer of care when objecting | Reduces geographic barriers; clarifies provider obligations re objection/transfer | Strong alignment with WHO guidance on task-sharing (midwives/NPs providing abortion ≤12–14w) and service availability obligation |

| 3 | Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act | 1996 | National | South Africa | Grounds & gestational limits; facilities; counselling; consent | Women/pregnant persons; medical practitioners & trained midwives | Implemented | Determine circumstances/conditions for legal abortion; promote reproductive rights | On request ≤12 weeks; 13–20 weeks on specified grounds (health, anomaly, rape/incest, socio-economic); >20 weeks on serious grounds; | Rights-based preamble; access emphasis; minors advised to consult but not required | High alignment with WHO guidance: abortion on request in the first trimester and broad grounds thereafter |

| 4 | Cabinet Resolution No. (44) of 2024 Concerning the Permitted Abortion Cases | 2024 | National | United Arab Emirates | Defines permitted abortion cases beyond existing law | Pregnant women; health facilities & authorities | Implemented | Regulate permitted abortion cases; | Permitted if pregnancy from rape or incest, or on spouses’ request with committee approval; ≤120 days GA; licensed OB-GYN; written consent; emergency exception; residency requirement for non-citizens; committee decision ≤5 business days; data/privacy duties | Privacy safeguards; oversight; some restrictions that may affect access | Limited/conditional alignment: committee-approved access for rape/incest and certain indications plus privacy safeguards echoes WHO harm-reduction and confidentiality standards |

| 5 | AusPAR Extract—Clinical Evaluation Report for mifepristone/misoprostol (MS-2 Step) | 2013 | National | Australia | Medical abortion regimen | Women of child-bearing age | Implemented | Provide alternative to surgical termination; composite pack rationale for better adherence | Expands access to early medical abortion option nationally | The regulatory approval promotes greater health equity by expanding safe, effective medical abortion options beyond urban hospital settings, reducing geographic and socio-economic disparities. | Strong alignment with WHO: endorses the recommended mifepristone+misoprostol regimen for early medical abortion; both medicines are on the WHO Essential Medicines List; |

| 6 | Contraception, Sterilisation, and Abortion (Safe Areas) Amendment Act | 2022 | National | New Zealand | Safe access to abortion services | Women seeking abortion | Implemented | Protect safety, privacy, and dignity of people accessing/providing abortion | Criminalises intimidation, harassment, obstruction near facilities; establishes enforceable “safe areas” up to 150m | Ensures dignity and privacy for women and providers; reduces inequity caused by intimidation that disproportionately affects vulnerable groups | Aligned with WHO Abortion Care Guideline (2022) on safe, stigma-free access; linked to ICPD, CEDAW GR No.24, and SDGs 3.7 and 5.6. |

| 7 | Replication of the Uruguayan model in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina | 2016 | Provincial | Argentina | legal abortion services at primary care | Women seeking abortion | Implemented | Reduce unsafe abortion and maternal deaths | Expansion of services; abortion-related maternal deaths fell by two-thirds | Addresses inequities by decentralizing services to primary care and empowering midwives/general doctors; prioritises poor women most affected by unsafe abortion | Closely aligned with WHO harm-reduction and task-sharing guidance, ICPD, and SDGs 3.1 and 3.7. |

| 8 | National Guideline for Family Planning Services | 2011 | National | Ethiopia | prevention of unsafe abortion | Women of reproductive age | Implemented | Reduce maternal mortality, unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortion | Scale-up of contraceptive methods (Implanon, misoprostol); strengthened health extension program | Prioritises underserved groups (rural women, adolescents), integrates misoprostol for postpartum haemorrhage and abortion prevention | Developed with UNFPA, WHO, USAID, Marie Stopes; aligned with MDG 5, ICPD, and WHO FP2020 goals. |

| 9 | National Strategy for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights | 2022 | National | Sweden | Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights | Whole population | Implemented | Achieve “good, fair, and equal Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights” | safe abortion, gender equality, anti-discrimination | Focus on equity across socioeconomic status, gender, migrants, LGBTQI, and disabled populations | Fully aligned with Guttmacher-Lancet SRHR framework (2018), WHO SRHR/Abortion Care (2022), ICPD, CEDAW, and SDGs. |

| 10 | National Reproductive Health Service Policy and Standards | 2014 | National | Ghana | Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights | Women of reproductive age | Implemented | Reduce maternal morbidity/mortality from unsafe abortion, ensure safe/accessible care, integrate abortion with broader reproductive health services | Increased access to legal abortion and PAC; reduction of unsafe abortion burden | Emphasises non-discrimination, no mandatory third-party consent, privacy/confidentiality, inclusion of rural and vulnerable women | Explicitly references WHO definition of unsafe abortion; aligned with ICPD commitments, WHO safe abortion guidance, and SDGs |

| 11 | National Women’s Health Strategy 2020–2030 | 2018 | National | Australia | sexual & reproductive health | All women & girls, | Implemented | Provide life-course, gender-specific framework; improve equity in SRHR and overall health | Identifies 5 priority areas incl. sexual & reproductive health; promotes integration across systems | Explicit focus on Aboriginal women, LGBTQI, migrants, low-income, disabled; addresses violence and inequities | Aligns with WHO Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (2016–2030), Agenda 2030 (SDG 3, 5, 10), ICPD, CEDAW. |

| 12 | National Medical Standard for Reproductive Health | 2020 | National | Nepal | post-abortion contraception | Women of reproductive age | Implemented | Ensure evidence-based FP/RH services incl. counselling, post-abortion contraception, sterilisation | Defines informed choice, rights-based counselling, and quality standards; integrates PAC contraception | Equity via nondiscrimination (age, marital, socio-economic, ethnicity, orientation); rural access; consent protocols | Based on WHO FP Handbook (2018), WHO MEC (2015); developed with UNFPA, DFID, USAID, WHO; aligned with ICPD and SDG |

| 13 | RANZCOG Submission on Women’s Health Strategy | 2023 | National | New Zealand | sexual & reproductive health | Women across lifespan | Implemented | Advocate for equity-based national strategy; strengthen SRHR, leadership, workforce | Identifies barriers (financial, geographic, cultural, systemic bias); proposes integrated, equity-based system | Explicit on racism, bias, gender inequity; Māori and Pacific priorities; cost & access barriers | Consistent with WHO SRHR rights-based approach, I |

| 14 | National Population Policy | 2006 | National | Tanzania | sexual & reproductive health | Whole population | Implemented | Integrate population issues into development; promote gender equality & reproductive rights | Strengthened FP/MCH services; PAC and youth ASRH integrated into development goals | Equity principles include gender equality, reproductive rights, vulnerable group inclusion | aligned with UN human rights standards, |

| 15 | National Reproductive Health Policy 2022–2032 | 2022 | National | Kenya | Abortion (post-abortion care), | All Kenyans, | Implemented | reduce maternal/neonatal mortality, unmet FP, unsafe abortion, | Expanded FP/PAC services, elimination of GBV/FGM, adolescent health integration, infertility services | Explicit focus on vulnerable groups (youth, elderly, PLWD, humanitarian settings); no spousal consent; rights-based | Anchored in Constitution (2010), Vision 2030; explicitly aligned to SDGs 3, 5, 10, ICPD, CEDAW, WHO SRHR frameworks |

| 16 | NHS Wales Women’s Health Plan 2025–2035 | 2025 | National | Wales | Abortion care | Women and girls 16+ | Implemented | deliver life-course women’s health | expanded abortion/contraception access | Intersectionality central (race, SES, disability, LGBTQ+); | Explicitly aligns with WHO SRHR/Abortion Care 2022, CEDAW, SDG 3, 5, 10, Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 |

| 17 | Women’s Health Plan 2021–2024 | 2021 | National | Scotland | Abortion care | Women and girls, | Implemented | improve access to abortion, contraception, and women’s specific services | Virtual abortion/contraception models post-COVID | Addresses gender pay gap, GBV, systemic bias; inclusive of trans/NB people; aims to tackle poverty-related health inequities | Aligned with WHO SRHR frameworks, ICPD, CEDAW, SDGs 3.7, 5.6, 10.2; |

| 18 | Abortion: Policy Position Statement (PHAA) | 2023 | National | Australia | Safe abortion regulation, access, integration into public health system, decriminalisation | All women and people able to conceive | Implemented | Decriminalise abortion in all jurisdictions | Framework for equitable abortion care, influencing federal and state health service planning, advocacy for workforce and curriculum reform | Explicit focus on underserved groups (rural, minority, low-income, adolescents, LGBTQ+), rejection of discriminatory barriers like spousal consent, emphasis on culturally safe and affordable care | Directly cites WHO Safe Abortion Guidance (2012) and UN SDGs (3.1, 3.7, 5.6); aligns with ICPD and UN human rights frameworks |

| 19 | Health Act 1993 – Part 6 Abortions (ACT) | 2023 (updated; first adopted 1989) | National | Australia | Abortion policy & reproductive health | Women, adolescents, sexual minorities, | Implemented | To ensure universal, safe, timely, affordable, and equitable access to abortion; remove abortion from criminal law; integrate abortion into public health services; strengthen national SRH strategy | Recognition of abortion as routine healthcare; support for nurse-led and telehealth abortion; call for national referral pathways and data collection; advocacy for removal of legal barriers; promotion of evidence-based guidelines and funding | Explicit recognition of equity barriers for adolescents, ethno-cultural minorities, low-income, rural/remote women, survivors of violence, and sexual minorities | Aligns with WHO’s Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance (2012) and UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDG 3.1, 3.7, 5.6). |

| 20 | Termination of Pregnancy Act | 2021 | State | South Australia | Abortion regulation | Women & pregnant people | Implemented | Legalise abortion up to 22w6d on request; after that with two doctors if health/life risk or severe anomalies; regulate conscientious objection and sex-selection | Provides safe access zones; privacy protections; mandatory counselling information; ensures medical care post-abortion; decriminalises self-managed abortion | Recognises barriers for rural, disadvantaged, and vulnerable groups (socio-economic, language, abuse) | Aligns with WHO Safe Abortion Guidance, UN ICPD, and SDGs |

| 21 | Abortion Access Scorecard (MSI Australia) | 2024 | National | Australia | Accessibility of abortion law & services (gestational limits, providers, conscientious objection, safe zones, data) | Women, adolescents, sexual minorities, migrants, rural/remote | Implemented | Evaluate abortion law harmonisation, highlight gaps & barriers | Maps gestational limits (16–24 weeks), SAZs (50–150m), counselling, CO referral duties, data gaps | Identifies inequities in rural/remote, low-income, migrants, LGBTQI+, and those facing harassment | Aligns with WHO/UN human rights commitments by benchmarking national practice against SDG 5.6 and WHO abortion care standards (2022). |

| 22 | Abortion Legislation Act | 2020 | National | New Zealand | Comprehensive abortion law reform | Women & pregnant people nationwide | Implemented | Decriminalise abortion; allow up to 20 weeks on request; after 20 weeks if clinically appropriate; ensure access, data, and CO regulations | Self-referral permitted; mandatory counselling info; CO requires redirection; national provider lists and data collection; periodic review of equitable access | Explicit on timely, equitable access; requires equity reviews every 5 years; mandates service availability nationwide | Fully aligned with WHO abortion standards, CEDAW, and SDG 3.7/5.6; integrates human rights framing into statutory law. |

| 23 | Middle East Abortion Laws & Global SRHR Policies (compiled source list) | Various years | International | Middle East, Australia, NZ, Africa, etc. | Abortion legal frameworks & SRHR strategy references | Women | Implemented | Provide comparative repository of abortion laws & policies worldwide | Summarises restrictive (e.g., Gulf, Iran) vs liberal (Australia, NZ, Uruguay) frameworks | Notes inequities esp. in restrictive contexts; highlights rights-based approaches in liberal settings | Aligns with UN SRHR policy frameworks (ICPD, CEDAW, SDG 3 & 5); maps national laws against WHO rights-based standards. |

| 24 | Family Planning Alliance Australia: Position Statement on Abortion | 2023 | National | Australia | Abortion access & healthcare integration | All women | Implemented | Call for nationally consistent, legal, affordable, stigma-free abortion | Advocates for national abortion dataset; inclusive, stigma-free care; education for youth; CO disclosure & referral duties | Emphasises barriers for rural/remote, uninsured, low-income, migrant, LGBTQI+ people | Explicitly cites WHO Safe Abortion (2012), IPPF, and aligns with SDGs |

| 25 | Termination of Pregnancy Act 2018 (Queensland) | 2018 | State | Australia | Abortion law reform: gestational limits, provider regulation, conscientious objection, safe access zones | Women & pregnant people in Queensland | Implemented | Enable safe and reasonable access to terminations; regulate providers; protect women from criminal liability | Abortion legal up to 22 weeks; after 22 weeks with 2 doctors considering medical, psychological, and social factors; decriminalises self-managed abortion; creates 150m safe access zones; establishes offences for harassment/recording near clinics | Recognises privacy, dignity, and safety; mandates CO disclosure with referral; protects adolescents, rural women, and vulnerable groups | Fully aligned with WHO Abortion Care Standards (2022), ICPD Programme of Action, CEDAW, and SDGs |

| 26 | Public Health Amendment (Safe Access to Reproductive Health Clinics) Act 2018 (NSW) | 2018 | State | Australia | Abortion-related safe access zones | Women, pregnant people, providers, clinic staff | Implemented | Protect privacy, dignity, and safety of those accessing or providing abortion services | Creates 150m safe access zones; criminalises harassment, intimidation, obstruction, or communications likely to cause distress; bans unauthorised filming/recording near clinics | Ensures safe, stigma-free access for all service users regardless of age, background, or income | Aligns with WHO recommendations on removing barriers to safe abortion, UN human rights standards, and SDG |

| 27 | Reproductive Health Act; Case Law (Dobbs v. Jackson,) | 2022 | National | United States | Abortion law & regulation | Women, providers | Implemented | Define grounds & restrictions | Patchwork: access varies by state | Huge inequities (state, income, race) | Misaligned (WHO recommends abortion on request) |

| 28 | Canada Health Act; R. v. Morgentaler (1988); Provincial policies | 1988–2017 | Federal + Provincial | Canada | Abortion law, healthcare coverage | Women, providers | Implemented | Ensure abortion as insured service | Access varies by province | Geographic & rural access inequities | Broadly aligned (on request, no federal gestational limit) |

| 29 | Penal Code; Clinical Guidelines; Funding Guidelines | 2011–2017 | Federal + Cantonal | Switzerland | Abortion law | Women, providers | Implemented | Protect women’s health | Distress clause beyond 12 weeks | Access depends on canton | Partial alignment – WHO rejects “distress” clause |

| 30 | Termination of Pregnancy Act | 2023 | National | Netherlands | Abortion regulation, funding | Women, providers | Implemented | Provide safe, regulated abortion | Broad access via clinics/hospitals | Generally equitable | Strong alignment with WHO |

| 31 | Penal Code; Law No. 1477 | 2019 | National | Monaco | Abortion restrictions | Women, providers | Implemented | Protect women in limited cases | Very narrow grounds | Access nearly absent | Misaligned with WHO |

| 32 | Health Code; Penal Code; Abortion Info Brochure | 2015–2022 | National | Luxembourg | Abortion law | Women, providers | Implemented | Guarantee abortion as healthcare | Accessible, but gestational cutoff | Equity gaps post-14 wks | Mostly aligned; gestational limit restrictive |

| 33 | Penal Code; Health Insurance Law | 1987–2000 | National | Liechtenstein | Abortion prohibition | Women, providers | Implemented | Restrict abortion | Women travel abroad | Heavy inequities | Misaligned with WHO |

| 34 | Penal Code; Pregnancy Conflict Law | 1996–2023 | National | Germany | Abortion law, counselling | Women, providers | Implemented | Manage pregnancy conflicts | Counselling/3-day wait creates barriers | Unequal access across regions | Partial alignment – WHO rejects mandatory counselling |

| 35 | Public Health Code; Bioethics Law; Constitutional Amendment | 2021–2024 | National | France | Abortion rights | Women, providers | Implemented | Make abortion a constitutional right | Widely available, constitutionally protected | Remaining limits beyond 14 wks | Broadly aligned; gestational limit restrictive |

| 36 | Law on Interruption of Pregnancy; Penal Code | 2018 | National | Belgium | Abortion law | Women, providers | Implemented | Integrate abortion in healthcare | Safe abortions accessible | Short limit (12 wks) | WHO recommends beyond 12; partial alignment |

| 37 | Criminal Code; Federal Hospitals Act | 1998–2022 | National | Austria | Abortion law | Women, providers | Implemented | Allow abortion within healthcare | Services available but limited by cutoff | Access varies | Partial alignment |

| 38 | Health Protection Law; Criminal Code; Abortion Guidelines | 2007–2024 | National | Russia | Abortion regulation | Women, providers | Implemented | Regulate abortion provision | Counselling requirements + sanctions | Barriers beyond 12 wks | Misaligned (grounds-based) |

| 39 | Penal Code; Medical Clinics Law; Norms | 2001–2009 | National | Romania | Abortion law | Women, providers | Implemented | Safeguard maternal health | Broad grounds but barriers remain | Rural & financial inequities | Partial alignment |

| 40 | Reproductive Health Law; Abortion Standards | 2010–2020 | National | Moldova | Abortion law | Women, adolescents, migrants | Implemented | Ensure safe abortion | Broader social grounds (e.g., rape, violence) | Some equity measures, but barriers remain | Partially aligned |

| 41 | Family Planning Act; Constitutional Tribunal rulings | 1993–2020 | National | Poland | Penal restrictions | Women, providers | Implemented | Protect “foetal rights” | Most abortions criminalised; women travel abroad | Severe inequities | Strongly misaligned with WHO |

| 42 | Law on Protection of Human Life; Decree on Foetal Life | 1992–2022 | National | Hungary | Abortion restrictions | Women, minors | Implemented | Protect foetal life | Mandatory counselling, waiting periods | Structural barriers | Partial misalignment |

| 43 | Law on Abortion; Criminal Code | 1986–2011 | National | Czech Republic | Abortion law | Women, providers | Implemented | Ensure safe abortion | Broad access, publicly funded | Strong equity compared to region | Mostly aligned with WHO |

| 44 | Ordinance No. 2; Criminal Code; Health Insurance Law | 2000–2017 | National | Bulgaria | Abortion law | Women, providers | Implemented | Protect health & regulate provision | Some admin barriers | Regional disparities | Partial alignment |

| 45 | Law on Healthcare; Criminal Code; Abortion Directive | 1999–2014 | National | Belarus | Abortion law | Women, providers | Implemented | Regulate safe abortion | Abortion broadly accessible | Counselling sometimes required | Partially aligned |

| 46 | Abortion Act 1967 (as amended 1990) | 1967–1990 | National | England, Scotland, Wales | Abortion law | Women, providers | Implemented | Clarify lawful abortion | >90% ≤13 wks; NHS access | Socio-economic/geographic disparities | Partial alignment |

| 47 | Abortion (NI) (No. 2) Regulations | 2020 | National | Northern Ireland | Abortion law | Women, providers | Implemented | Align with human rights law | Access newly available but underdeveloped | Commissioning delays; uneven access | Closer to WHO but still limits |

| 48 | BMA – Law & Ethics of Abortion | 2020–2025 | National | UK | Medical ethics | Doctors, women | Implemented | Ethical guidance for providers | Clarifies consent, conscientious objection | Emphasises equity & non-discrimination | Fully aligned with WHO/FIGO |

| 49 | DFID Safe & Unsafe Abortion Policy | 2014 | National and global | UK (Global) | Safe abortion in LMICs | Women & girls in LMICs | Implemented | Reduce unsafe abortion mortality | Recognises high maternal death burden | Targets poorest & most vulnerable | Fully aligned with WHO, ICPD |

| 50 | Isle of Man Abortion Reform Act (2019); Jersey Law (1997); Guernsey Law (2021) | 1997–2021 | Regional | Crown Dependencies | Abortion law | Women | Implemented | Modernise abortion frameworks | Improved access; less need for travel | Variations across islands | Broadly aligned but with limits |

| 51 | Organic Law No. 01/2012/OL amending Penal Code; Ministry of Health Guidelines | 2012 | National | Rwanda ( | Abortion regulation | Women, providers | Legal for rape, incest, forced marriage, health/life risk | Reduce maternal mortality, update law | Ambiguity, stigma, liability | Stigma and provider fear hinder access | Misaligned – grounds-based, not on request |

| 52 | Maternal Protection Law (1948, amended); MHLW approval of MEFEEGO Pack | 2023 | National | Japan | Abortion & medical abortion regulation | Women, providers | Implemented | Introduce safe medical abortion | Very low uptake (1.5%), restrictive hospital rules | Equity issues: only hospitals with beds allowed | Partial alignment – WHO recommends broader access |

| 53 | Population Policy (One-/Two-/Three-Child); Family Planning Law | 1979–present | National | China | Population control & abortion access | Women, couples | Implemented | Control population growth | High abortion rates; coercion & surveillance | Minority women disproportionately impacted | Misaligned – coercion violates WHO/UN standards |

| 54 | Medication Abortion Policy (Mifepristone unapproved until 2015) | 2008 | National | Canada | Medication abortion & right to health | Women, providers | Implemented | Assess right-to-health compliance | Only 1–2% abortions medical before 2015 | Rural/remote inequities | Misaligned – WHO recommends mifepristone availability |

| 55 | Penal Code; Health Regulations; Post-Abortion Care Guidelines (2016); Mifepristone registration (2024) | 1981–2024 | National | Tanzania | Abortion law & post-abortion care | Women, providers | Implemented | Provide limited lawful grounds | Unsafe abortion major contributor to maternal mortality | Rural, young women highly affected | Misaligned – WHO opposes restrictive grounds |

| 56 | Criminal Code Act (1916); Penal Code (1960) | 1916–1960 | National | Nigeria | Abortion law | Women, providers | Implemented | Restrict abortion | Unsafe abortion = ≈11% maternal deaths | Adolescents and poor women most affected | Strongly misaligned – near-total ban |

| 57 | Pakistan Penal Code (1860, amended 1990); National Abortion Study (2023) | 1990–2023 | National | Pakistan | Abortion law & health outcomes | Women | Implemented | Monitor abortion trends | 3.8M abortions in 2023; ↑25% since 2012 | Misoprostol improved safety but inequities remain | Misaligned – restrictive, unsafe burden |

| 58 | Penal Code (2014); Fiqh Academy Fatwa (2013); Nat. Reproductive Health Strategy (2014–2018) | 2013–2018 | National | Maldives | Abortion restrictions | Women, providers | Implemented | Recognise unsafe abortion burden | Only 387 hospital admissions recorded (2016) | Husband/guardian consent required | Strongly misaligned – spousal consent, limited grounds |

| 59 | Universal Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: Gaps in Policies in the Maldives | 2018 | National | Maldives | SRHR incl. abortion | General population, adolescents, women | Implemented | Identify policy & legislative gaps in SRHR access | Family planning access improved but abortion laws remain restrictive under sociocultural/religious influence | Notes inequities for unmarried youth and adolescents | SDGs 3.7 & 5.6, ICPD PoA, Beijing Platform |

| 60 | Abortion Care in Nepal, 15 Years after Legalization | 2017 | National | Nepal | Abortion care & human rights | Women of reproductive age | Implemented | Assess equity & access after legalization | Increased safe abortion uptake, but barriers persist (fees, rural access) | Rural & poor women face inequities | Supreme Court aligned abortion with human rights (2009); ICPD, SDGs |

| 61 | Unsafe Abortion in Zambia | 2009 | National | Zambia | Unsafe abortion burden | Women of reproductive age | Implemented | Review incidence & barriers | Unsafe abortions high, few safe legal procedures due to 3-doctor rule | Poor and rural women most affected | Maputo Protocol commitments unmet |

| 62 | Japan turns pro-life: recent change in reproductive health policy | 2014 | National | Japan | Abortion, reproductive technologies | Women of reproductive age | Implemented | Describe history & policy changes | Abortions used historically for population control; declining fertility shifts debate | Economic grounds once liberalized access; current selective abortion debate | WHO SRHR standards; population policies |

| 63 | Maldives National RMNCAH Strategy and Action Plan 2020–2025 | 2020 | National | Maldives | RMNCAH incl. abortion | Women, adolescents, children | Implemented | Strengthen maternal & reproductive health services | Abortion only under narrow grounds (life-saving, rape, fetal anomaly) | Adolescents face highest unmet need for contraception | Aligned with SDGs, Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health |

| 64 | Knowledge and Attitude towards Ghana’s Abortion Law | 2023 | National | Ghana | Abortion law knowledge & attitudes | Female undergraduates | Implemented | Assess knowledge & attitudes | Many unaware of legal grounds; unsafe abortions persist | Students’ knowledge linked to access & equity | CEDAW, SDGs, WHO |

| 65 | Facts on Abortion in the Philippines | 2008 | National | Philippines | Criminalization of abortion | All women | Implemented | Highlight consequences of ban | Unsafe abortion leads to maternal deaths and abuse in healthcare | Poor women disproportionately harmed | Misaligned with WHO, UN human rights standards |

| 66 | Reproducing Inequalities: Abortion Policy and Practice in Thailand | 2002 | National | Thailand | Abortion law & practice | Women of reproductive age | Implemented | Explore lived experiences | Abortions common despite legal limits; inequalities persist | Poorer women resort to unsafe practices | WHO unsafe abortion framework; calls for reform |

| 67 | Shaping the abortion policy – Zambia’s Termination of Pregnancy Act | 2019 | National | Zambia | Termination of Pregnancy Act, Abortion policy, socio-political discourse | Women of reproductive age, policymakers, healthcare providers | Implemented | Explore policy discourse, Examine religious & political debates | Ambiguity limits access despite liberal appearance, Persistent stigma and provider refusal restrict safe access | Rural and poor women disadvantaged, Religious influence creates inequities | Maputo Protocol; ICPD |

| 68 | Kenya’s 2010 Abortion Law Impacts Contraceptive Use and Fertility Rates | 2010 (study 2025) | National | Kenya | Abortion law reform & reproductive health | Women of reproductive age | Implemented | Assess law’s impact on contraceptive uptake & fertility | ↑ modern contraceptive use, ↓ recent births | Rural women, low-education groups face barriers | Aligned with WHO definition of health & Maputo Protocol |

| 69 | Abortion Laws in Pakistan and Around the World: Case Study of Roe v. Wade | 1990 reforms; 1996/97 amendments | National | Pakistan | Abortion criminal law & Islamic jurisprudence | Women | Implemented | Trace evolution of law and global comparisons | Unsafe abortions high; ~900,000 induced abortions annually | Stigma, vague law, rural inequities | Misaligned – WHO/UN call for safe abortion access |

| 70 | Termination of Pregnancy Act (Zambia, Chapter 304) | 1972; amended 1994 | National | Zambia | Abortion law | Women of reproductive age | Implemented | Clarify conditions for lawful abortion | Allows abortion on grounds of life, health, anomalies | Access hindered by 3-doctor requirement, rural inequities | Maputo Protocol – but implementation weak |

| 71 | World’s Abortion Laws (Map, 2024) | 2024 | Global (with Russian Federation focus) | Global / Russian Federation | Comparative abortion law categories | Women, policymakers | Implemented | Provide global classification | Russia categorized as Category I (on request) | Rural access varies | WHO/UN recognition of abortion as human right |

| 72 | Unsafe Abortion Practices and the Law in Nigeria: Time for Change | 2020 | National | Nigeria | Abortion law & unsafe abortion | Women, clinicians | Implemented | Advocate reform to reduce unsafe abortion deaths | Unsafe abortion causes 10–30% maternal mortality | Poor, young, rural women disproportionately affected | Misaligned – WHO, CEDAW call for safe abortion |

| 73 | Supreme Court of India Judgment on Abortion as a Fundamental Right | 2022 | National | India | Abortion rights & constitutional law | Women, adolescents, transgender persons | Implemented | Recognize abortion as reproductive autonomy right | Landmark ruling: unmarried women equal rights; marital rape included; minors protected under POCSO | Structural barriers remain (caste, poverty, provider bias) | Strong alignment – UN/WHO human rights framing of abortion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).