1. Introduction

In today's data-driven world, data quality has become a vital factor in achieving organizational success, advancing scientific progress, and informing effective policymaking. Reliable information is indispensable across business, healthcare, and public administration. Poor data quality in these domains leads to significant social and economic consequences. [

1,

2,

3,

4]. While the concept of "quality" is context-dependent, it is broadly defined as data being “fit for [its] intended uses in operations, decision making and planning” [

5,

6]

This principle is critically important for research, as ensuring data quality is a prerequisite for transparency, reproducibility, and accountability in the scientific process. Robust data quality practices enhance the traceability of datasets and the credibility of scientific conclusions, aligning with broader initiatives such as the FAIR principles, which stipulate that data should be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable [

7].

This narrative review offers a unique contribution by synthesizing three areas that are seldom connected: established theoretical frameworks, practical applications in the business world, and emerging trends such as ethical governance and the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in data management. Unlike works that focus on a single dimension, this review offers a holistic perspective that connects technical challenges with their organizational and ethical implications, underscoring their direct impact on scientific reproducibility and strategic decision-making.

Data quality is typically assessed through a set of measurable dimensions—accuracy, completeness, consistency, timeliness, relevance, and validity—which together provide a framework for identifying and addressing potential issues [

7,

8]. These dimensions are widely applied across domains, including Customer Relationship Management (CRM). In SMEs, for example, failures in CRM implementation have often been linked to poor data quality, particularly in accuracy, consistency, and completeness, underscoring the importance of robust evaluation tools and processes [

9].

2. Material and Methods

We performed a narrative literature review covering publications from 1996 to 2025. Databases searched included PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, complemented with standards and technical documents (e.g., ISO/IEC 25012, ISO 8000). Inclusion criteria were: works explicitly addressing data quality frameworks, dimensions, or management practices; studies with applications in healthcare, business, or interdisciplinary contexts. Exclusion criteria included opinion pieces without methodological detail and articles that focused exclusively on data security. Sources were screened by title and abstract, and full texts were reviewed for relevance. Grey literature and international standards were considered to ensure comprehensive coverage. The findings were synthesized thematically, highlighting dimensions, methodologies, and applications of data quality. Detailed methodology is provided in

Supplementary Materials (S1).

3. Definitions and Frameworks of Data Quality

Data quality is an inherently contextual concept. The fundamental principle, widely accepted and popularized by Wang and Strong, is that high-quality data is "fit for use by data consumers"[

10] (Wang, 1996). This pragmatic definition emphasizes that quality is not an intrinsic, absolute property, but rather a dependent one, varying according to specific purpose, whether in operations, decision-making, or planning [

2,

11].

3.1. Standards and ISO 8000

ISO 8000, the international data quality standard, originated in the NATO Codification System (NCS), a framework developed to catalog material items with uniform descriptions and codes, improving inventory management and supply chain efficiency [

12]. In 2004, NATO Allied Committee 135 and the Electronic Commerce Code Management Association (ECCMA) formalized its promotion as the basis for an international standard. This collaboration led to ISO 8000, which built on the NCS’s emphasis on precise, standardized data descriptions and management practices, refined over decades [

11,

12,

13].

ISO 8000 defines quality data as “portable data that meets stated requirements.” Data must be separable from a software application (portable) and comply with explicit, unambiguous requirements set by the user or consumer [

13]. It also aligns with broader initiatives in data portability and preservation, enabling organizations to define, request, and verify data quality using standard conventions [

14]

Complementing ISO 8000, ISO 25012 provides a foundational model with 15 dimensions of data quality, including accuracy, completeness, consistency, and traceability, initially designed for software but now widely applied across domains [

15].

Table 1.

Comparison of selected definitions and frameworks of data quality.

Table 1.

Comparison of selected definitions and frameworks of data quality.

| Source / Standard |

Definition of Data Quality |

Key Dimensions / Emphasis |

Notes |

| ISO 8000 (2011–2015) [5,13,14,16] |

“Quality is the conformance of characteristics to requirements.” Data is high-quality if it meets stated requirements. |

Accuracy, completeness, consistency, timeliness, uniqueness, validity. |

Formal international standard; widely adopted in industry. |

| Wang & Strong (1996)[10] |

“Data quality is data that is fit for use by data consumers.” |

Four categories: Intrinsic (accuracy, objectivity), Contextual (relevance, timeliness, completeness), Representational (interpretability, consistency), Accessibility (access, security). |

Highly influential conceptual framework; consumer-oriented. |

| Strong, Lee & Wang (1997)[11] |

Emphasizes data quality as “fitness for use” in operations, decision-making, and planning. |

Same four categories as above. |

Extends the earlier framework with an organizational perspective. |

| Pipino, Lee & Wang (2002)[17] |

Defines data quality through measurable attributes that reflect accuracy, completeness, consistency, and timeliness. |

Quantitative measures for core dimensions. |

Introduces practical tools for data quality assessment. |

| Ehrlinger & Wöß (2022) [18] |

Data quality as a multidimensional construct is influenced by context and use. |

Highlights timeliness, completeness, plausibility, integrity, and multifacetedness. |

Extends beyond classical dimensions and focuses on big data. |

| Haug, Zachariassen & van Liempt (2011)[19] |

Suggests that “perfect” data quality is neither achievable nor optimal; instead, the right level balances costs of maintenance vs. costs of poor data. |

Trade-off between quality maintenance effort and business impact. |

Cost-oriented perspective. |

3.2. Conceptual Definitions

Maintaining high data quality in Customer Relationship Management (CRM) systems is crucial, as it directly impacts key performance indicators, including customer loyalty and promotional success. Reliable data supports accurate decision-making, marketing objectives, and competitive advantage in data-driven environments [

20]

High-quality data is commonly defined as “fit for use” in operations, decision-making, and planning, emphasizing its contextual and subjective nature [

18]. Philosophical analyses reinforce this perspective, noting that data quality is not intrinsic but depends on its relationship to research questions, tools, and goals. Thus, a dataset may be suitable for epidemiological research but inadequate for historical analysis, underscoring the need for assessments to consider context as much as the dataset itself [

21].

Evaluation of data quality encompasses multiple dimensions, including accuracy, completeness, consistency, timeliness, validity, accessibility, uniqueness, and integrity [

22]. These dimensions ensure that organizations relying on data-driven insights can achieve their objectives [

11]

Quality also depends on meeting the expectations of data consumers, which are often implicit and evolving. Continuous engagement with users helps ensure reliability and adaptability to changing needs [

23]. A critical task is managing “critical data”—information that has a significant impact on regulatory compliance, financial accuracy, or strategic decision-making. Master data, such as customer, supplier, and product records, exemplifies this, as it directly affects operations and outcomes. Prioritizing critical data enables organizations to allocate resources efficiently, mitigate risks, and enhance customer satisfaction [

23].

Pragmatically, data quality is defined as data that effectively supports analysis, planning, and operations [

24]. High-quality data contributes to organizational success by providing trustworthy inputs for processes and analytics, even as enterprises face increasing data volumes and diversity [

22]

3.3. Frameworks

Although many organizations aim to improve data quality, efforts often focus narrowly on accuracy and completeness. This overlooks the multidimensional nature of data quality, which must also reflect consumer needs and perceptions. Wang and Strong developed a widely used framework with four dimensions: [

10]

Intrinsic – data should be accurate, reliable, and error-free;

Contextual – relevance depends on the task or use case;

Representational – clarity and proper formatting enable correct interpretation;

Accessibility – data must be available to users when and where needed.

Data quality should be systematically assessed using both subjective perceptions and objective measures [

17]. In healthcare, for instance, reliable data underpins patient records, diagnostics, research, and public health monitoring.

Vaknin and Filipowska (2017) integrated information quality into business process modeling, addressing potential deficiencies at the design stage rather than relying solely on post-hoc cleansing [

25]. In Customer Relationship Management (CRM), high-quality data enables segmentation, forecasting, and targeted marketing, directly affecting satisfaction and business performance, while poor-quality data undermines insights and decision-making [

7,

20]. Practical management requires preprocessing, profiling, and cleansing to ensure accurate analytics [

1,

18,

25].

Miller advanced the field by aggregating 262 terms into standardized dimensions based on ISO 25012, which was extended to include governance, usefulness, quantity, and semantics [

15]. This addresses terminology fragmentation and promotes cross-sector collaboration. A complementary approach grounded in the FAIR principles proposes quality ascertained from comprehensive metadata, decoupling intrinsic properties from subjective needs and facilitating reuse across contexts [

26]. FAIR has also been adapted for research software (FAIR4RS), accounting for executability, dependencies, and versioning, thereby extending reproducibility beyond data to the software that processes it [

27]

Recent methods embed information quality requirements directly into business process models. Silva Lopes introduced “information quality fragments,” modular components that integrate checks for accessibility, completeness, accuracy, and consistency, improving efficiency and reducing modeling time [

28].

Beyond business contexts, frameworks for public administration emphasize both organizational and technological aspects. Studies of Ukrainian e-government show that staff skills, process design, and management practices are decisive for ensuring high-quality information in government [

29].

A notable theoretical contribution is Xu Jianfeng’s Objective Information Theory, which defines information through a sextuple structure and nine metrics—such as extensity, richness, validity, and distribution—offering a systematic basis for quantitative analysis [

30]. Building on this, research in the judicial domain has applied six-tuple information theory and rough set knowledge to develop measurable standards for document quality, showing that even text-driven contexts like court documents can benefit from formalized models that quantify accuracy, completeness, and semantic fidelity [

31]

The FAIR principles have also been extended beyond data to research software, emphasizing that reproducibility depends not only on datasets but also on the tools and code that process them [

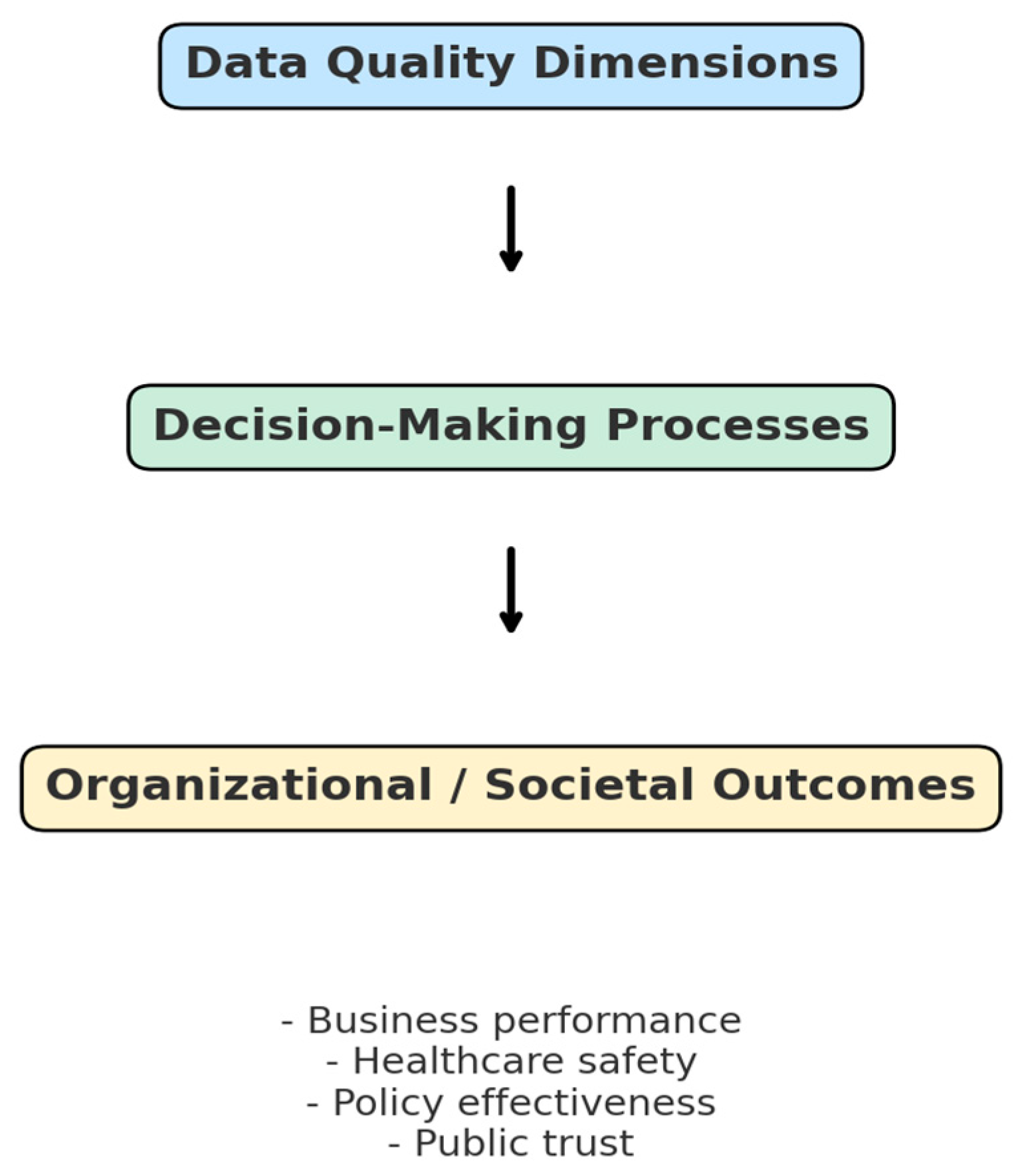

32]. Together, these approaches underscore the diverse contributions of models of information quality to decision-making and broader outcomes across various sectors, as illustrated in

Figure 1, where multiple dimensions of data quality support reliable analysis and foster trust in business, healthcare, and public policy.

3.4. Scope of Data Quality in Data Analytics

In data analytics, data quality is paramount: analytical models and algorithms depend on accurate and complete inputs to generate meaningful insights and support sound decision-making. Models trained on flawed data can yield unreliable predictions, leading to misguided strategies. Conversely, high-quality data enhances the accuracy, fairness, robustness, and scalability of machine learning models, underscoring the importance of specialized tools in the era of data-centric AI [

33]. [

34]

3.4.1. Role in Data Analytics

Within Customer Relationship Management (CRM), data quality is especially critical. Reliable and consistent datasets enable accurate predictive modeling, such as customer lifetime value (CLV) estimations and RFM (Recency, Frequency, and Monetary) analysis, supporting effective segmentation, investment optimization, and customer equity assessment systems [

3,

7,

8,

20,

22]. Well-maintained data sets enhance the effectiveness of predictive modeling, such. Poor data quality, by contrast, compromises analytics, leading to misinformed decisions, missed opportunities, and weakened strategies [

24,

33]].

The importance of data quality tools is reflected in a 2022 systematic review, which identified 667 solutions for profiling, measurement, and automated monitoring [

18]. Nevertheless, despite this breadth, many organizations still rely on rudimentary methods: a German survey found that 66% of companies validate data quality with Excel or Access, and 63% do so manually without long-term planning [

35]. Within CRM, this gap between available technologies and organizational practices highlights the persistent challenges of implementing comprehensive, scalable data quality management.

4. Dimensions of Data Quality

Building on these frameworks and conceptual definitions, the following sections examine the key dimensions of data quality—such as accuracy, completeness, consistency, timeliness, relevance, and validity—that provide practical criteria for assessing and improving information quality across domains.

4.1. Accuracy

Accuracy refers to the extent to which data represents the real-world construct they describe. [

24] It can be quantified through error rates, field- and record-level measures [

18,

33], and newer metrics that distinguish between random and systematic errors. [

36]. Accuracy is especially critical for ensuring reliable insights in analytics and marketing, where decisions must reflect actual market conditions [

9,

20]. In CRM systems, maintaining accuracy is challenging because customer information (e.g., addresses or contacts) changes frequently [

33]. Inaccurate data can distort segmentation, targeting, and predictive models, undermining customer management strategies. To safeguard accuracy, organizations employ validation and verification processes [

24]. Complemented by audits, cross-checking with external databases, and automated validation techniques [

34]. Ultimately, accurate data is a cornerstone of data quality, supporting effective decision-making and strengthening organizational performance.

4.2. Completeness

Completeness measures the extent to which all required data are present [

18]. It involves ensuring that all necessary data is present and accounted for, minimizing the occurrence of missing values that can compromise the dataset's overall usefulness. This dimension needs to be quantified through specific metrics to assess data quality effectively [

18]. In CRM systems, complete data is essential for creating comprehensive customer profiles and achieving accurate analytical outcomes [

20].

4.3. Consistency

Data consistency is important, particularly in terms of standardizing data definitions and structures. Consistent data ensures that different departments and functions within an organization interpret and use the data similarly, which is crucial for maintaining the integrity and reliability of data-driven decisions [

22].

4.4. Timeliness

Timeliness reflects the availability of data when needed, considering both speed and context. Real-time data is vital in domains such as stock trading, where rapid changes demand instant responses [

37], while daily or weekly updates may suffice for inventory management, helping prevent overproduction or stockouts [

38]. Timeliness depends on collection methods, processing speed, and update frequency, requiring organizations to minimize latency and ensure data is current [

39,

40,

41,

42].

Regulatory frameworks often mandate timely reporting [

43,

44,

45]. In healthcare, outdated records can compromise patient safety [

46,

47,

48,

49]. In business, untimely data undermines marketing campaigns and agility, while current data enhances responsiveness and competitiveness [

50]. Organizations must balance the benefits of real-time information against the costs of maintaining it [

51].

A related challenge is data decay, the gradual obsolescence of information, as seen in marketing, where up to 40% of email addresses change every two years [

35]. Mitigating decay and maintaining timeliness are crucial for reliable analytics, resource efficiency, and improved decision-making [

52].

4.5. Relevance

Relevance assesses how well data supports specific business needs and decision-making [

10]. Data must serve its intended purpose, aligning with organizational objectives and challenges [

53]. For example, accurate purchase histories may not fully explain customer churn if they lack information on satisfaction or service interactions; incorporating sentiment data provides more relevant insights.

Relevance is highly context-dependent, varying across organizational areas [

54]. Marketing departments prioritize demographics, purchasing behavior, and market trends to craft strategies, while financial teams focus on cash flow, revenue, and expenses for accurate planning. Thus, relevance is not static but shifts with the goals and requirements of users.

Measuring relevance ensures that collected information contributes to informed decisions. Common approaches include tracking dataset usage, assessing “time to analysis” (shorter times reflect higher relevance), and gathering user feedback to identify gaps [

55]. By aligning data with context-specific needs, organizations ensure that analytics are not only accurate but also meaningful for strategy and performance.

4.6. Validity

Validity ensures that data accurately represent real-world constructs and comply with predefined standards and business rules [

56]. It assesses conformity to formats, ranges, and logical relationships—for example, a date of birth within a realistic range or an address following national conventions [

57]. Validity encompasses several forms: content validity, which confirms that a dataset covers all relevant aspects [

58]; construct validity, ensuring alignment with theoretical concepts [

59,

60]; and criterion-related validity, which evaluates predictive power[

61].

Invalid data can cause flawed analyses, poor decisions, and operational disruptions. Examples include failed deliveries to incorrect addresses [

62], misleading financial data that affects investors, or inaccurate market research leading to wasted resources. Validity also supports integration and interoperability, as adherence to shared rules and formats facilitates combining data from multiple sources [

63]

In the era of big data and AI, validity is increasingly critical: high-quality inputs underpin reliable models and algorithms, while advanced analytics can also assist in validating data [

64,

65]. Thus, validity is both a safeguard and an enabler of trustworthy data-driven processes.

4.7. Emerging Dimensions (Plausibility, Multifacetedness, Integrity)

Beyond classical attributes, new dimensions such as governance, usefulness, quantity, and semantics have been proposed [

15]. Governance refers to the accountability and authority structures that guide data activities. Usefulness emphasizes adaptability and reusability. Quantity addresses sufficiency and scalability. Semantics ensure that data meaning is preserved across systems. These additions reflect evolving understandings of data quality in contexts such as IoT, big data, and knowledge graphs.

Vaknin and Filipowska [

25] further highlight process-related dimensions, including traceability, semantic validity, and conformance of data flow, embedding quality checks into workflows rather than applying them post hoc. This process-centric view extends traditional dimensions, such as accuracy and completeness, ensuring proactive verification of accessibility and consistency at the workflow level [

28].

At the theoretical level, Xu Jianfeng’s Objective Information Theory [

30] defines information through a sextuple structure and nine quantitative metrics (e.g., extensity, richness, validity), providing a mathematical foundation for assessing information beyond traditional attributes.

Ultimately, research on judicial documents underscores the growing importance of semantic and context-specific dimensions. Here, quality evaluation must capture not only syntactic correctness but also semantic adequacy, underscoring the domain-driven expansion of data quality frameworks [

31].

Table 2 summarizes the main dimensions of data quality, with their definitions, practical examples, and approaches to measurement.

5. Consequences of Poor Data Quality

Organizations that neglect data quality in their CRM systems face serious consequences, including misleading conclusions, wasted resources, and reputational harm [

7]. Inaccurate or inconsistent records distort insights, inflate costs, and reduce efficiency. Studies estimate that organizations can lose up to 6% of sales due to poor customer data management [

24]. Fraudulent practices represent a particularly damaging source of poor quality: research shows that falsified records, such as fraudulent sick-leave claims, degrade timeliness, coherence, believability, and interpretability, sometimes even inflating completeness while eroding reliability [

66]. Such issues often require costly cleansing and manual intervention.

5.1. Impact on Decision-Making and Outcomes

The financial impact is substantial. Gartner estimates annual losses of USD 12.9 million per organization, while IBM reports that U.S. businesses lose over USD 3.1 trillion annually[

67,

68,

69,

70]. Poor data quality also increases ecosystem complexity, leading to suboptimal decisions [

71]. In CRM, outdated contact details or incorrect names can undermine segmentation and marketing efforts.[

24].

5.2. Flawed Insights and Conclusions

Low-quality data leads directly to flawed segmentation, poor targeting, and reduced performance [

22]. Time, money, and credibility are wasted addressing these issues [

23]. Industry experts estimate that data quality challenges consume 10–30% of a company's revenue. [

52] A striking example is Unity Technologies’ Audience Pinpoint error (2022), where poor input data led to faulty algorithms, resulting in USD 110 million in losses and a 37% decline in stock value [

72].

5.3. Wasted Resources

Cleaning inaccurate or incomplete data is a significant and resource-intensive task. Manual and automated correction efforts are expensive, with Harvard Business Review estimating tasks done with bad data cost 100 times more than those with accurate data. The 1-10-100 rule illustrates that prevention (

$1) is far cheaper than correction (

$10) or failure costs (

$100) [

33,

73].

5.4. Damaged Reputation

Incorrect interactions or failed campaigns erode customer trust and damage brand image. Case studies show reputational damage is a frequent consequence of poor data management. [

20]

5.5. Missed Opportunities

Poor-quality data contributes to wasted potential, with up to 45% of generated leads being deemed unusable due to duplication, invalid emails, or incomplete records [

74]. Consequences include lost revenue, overlooked market segments, and hindered research progress. In healthcare, incomplete patient records may obscure critical patterns, delaying discoveries. Such missed opportunities amplify long-term competitive disadvantages [

34,

75]

Table 3 summarizes key consequences across domains.

6. Case Studies: Illustrating the Consequences of Data Quality Failures and Successes

Real-world cases highlight both the risks associated with poor data quality and the benefits of robust data management. Organizations with decentralized storage and inconsistent entry practices often struggle to manage customer relationships effectively, while those investing in integration tools and governance frameworks report greater efficiency, cost savings, and competitive advantage [

7,

20]. High-quality data enables precise segmentation and targeting, supporting stronger customer relationships and sustainable growth [

24]

Systemic issues can also arise from organizational architecture. A financial institution, for example, found that legacy “data silos” perpetuated duplication, inconsistency, and limited access, hampering analytics. Transitioning toward modern paradigms, such as the Data Mesh, has improved availability and quality across the enterprise [

76].

Overall, these examples show that failures often stem from governance and architectural oversights with significant consequences, while success requires sustained monitoring, continuous improvement, and the application of robust frameworks.

Table 4 summarizes key cases of data quality failures and successes.

Real-world cases vividly show how data quality shapes organizational outcomes. A classic example is the loss of NASA’s Mars Climate Orbiter, which was destroyed by a mismatch between imperial and metric units—a

$125 million failure of consistency [

77]. In contrast, Netflix’s personalized recommendation system demonstrates how high-quality data can become a strategic asset: leveraging user behavior data to drive over 80% of platform consumption [

78].

These cases illustrate the high stakes of data quality: poor practices can lead to catastrophic losses, while robust frameworks can create a lasting competitive advantage. [

20,

22,

24,

25,

33,

72,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84]. Additional failures and successes across domains—including finance, healthcare, logistics, and public administration—are summarized in

Table 4

Table 4.

Case Studies of Data Quality Issues and Their Consequences Across Domains.

Table 4.

Case Studies of Data Quality Issues and Their Consequences Across Domains.

| Case / Organization |

Domain |

Data Quality Issue |

Consequence |

| Failures |

|

|

|

| Equifax [72] |

Finance / Credit reporting |

Inaccurate and poorly managed consumer credit data |

Erosion of public trust; legal and financial consequences |

| NASA Mars Climate Orbiter) [25] |

Aerospace / Engineering |

Unit mismatch (imperial vs. metric) not reconciled in data systems |

Spacecraft loss (~$125 million) |

| Mid-sized enterprise (CRM migration) [24] |

Business / CRM |

Data quality challenges during migration from legacy systems |

Errors, inconsistent formats, and disruption in customer management |

| Large home appliance business [20] |

Retail / CRM |

Low completeness, timeliness, and accuracy of customer data |

Ineffective campaigns, reduced loyalty, and weak predictive performance |

| University fundraising CRM. [33] |

Education / Fundraising |

Outdated, incomplete, and inaccurate alumni data |

Reduced donor identification, inefficient fundraising, wasted resources |

| Target [82]. |

Retail / CRM |

Predictive analytics revealed sensitive customer information |

Public backlash over privacy intrusion |

| Google Flu Trends (2008–2013) [79,80,81]. |

Public health analytics |

Overfitting and reliance on biased signals |

Overestimation of flu cases; credibility loss |

| Amsterdam Tax Office [24]. |

Public sector |

Duplicate and inconsistent taxpayer records |

Inefficient operations; reduced compliance |

| Healthcare organizations [22,83,84] |

Healthcare / CRM |

Incomplete or inconsistent patient data in electronic health records |

Medical errors, patient safety risks |

| Successes of Data Quality |

|

|

|

| Netflix Recommendation System [78]. |

Entertainment / Business |

Leveraging high-quality behavioral data for personalization |

Recommendations drive 80% of content consumption; increased engagement and revenue |

| Freight forwarding industry [25] |

Logistics / Freight forwarding |

Workflow-embedded quality checks across logistics processes |

Improved coordination, fewer customs delays, reduced correction costs |

7. Ensuring Data Quality: Methods and Best Practices

Ensuring high data quality requires a combination of standardized methodologies and continuous validation. Effective data collection is fundamental: standardized procedures and tools minimize errors at the source, while validation checks confirm that data entries meet predefined criteria[

85]

7.1. Data Collection Practices

In CRM adoption by SMEs, robust data collection processes are essential for capturing accurate and relevant customer information. This involves integrating multiple internal and external sources and ensuring that data is timely and aligned with business objectives. Systematic frameworks and staff training help maintain consistency and reduce errors such as duplicate or incomplete records, which can undermine CRM performance [

9].

Best practices include the use of automated data entry systems, regular cleaning processes to eliminate inaccuracies, and validation checks to ensure consistency and accuracy. Continuous monitoring and maintenance are crucial as data sources and systems evolve, ensuring that quality standards are consistently maintained over time.[

7]

7.2. Data Cleaning and Validation

Data cleaning and validation are crucial for maintaining data quality, which involves detecting and correcting inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and missing values [

9]. Automated tools can efficiently flag anomalies, but critical production environments often require a balanced approach that integrates manual review to ensure accuracy and reliability. A multicenter clinical database study demonstrated the effectiveness of semi-automated assessments in detecting widespread issues, while minimal manual checks remained necessary to address errors missed by automation [

86]. However, manual abstraction also generated false positives, emphasizing the need to optimize manual efforts.[

18] Regular monitoring and quality reviews help sustain reliable datasets [

9,

87]. Establishing metrics and periodic audits ensures data remains accurate, timely, and fit for analysis. In CRM systems, poor validation can erode user trust and compromise adoption [

22,

24], particularly in SMEs facing frequent inconsistencies [

24]. Robust cleaning practices—such as removing duplicates, filling missing values, and discarding outdated entries—reduce remediation costs and risks [

33]. Preventive controls and improved entry processes further minimize errors [

8].

Advanced methods, including deep learning models such as the Denoising Self-Attention Network (DSAN), enhance the imputation of mixed-type tabular data by leveraging self-attention and multitask learning to predict substitutes for both numerical and categorical fields [

88]. Data fusion also enhances reliability by integrating heterogeneous sources, thereby reducing uncertainty and providing more comprehensive representations [

89].

Ultimately, rigorous validation and governance policies [

1] combined with automated tools and audits [

9] ensure consistent data quality. This is crucial for CRM, where reliable data directly impacts campaign success, customer loyalty, and business performance [

20].

7.3. Monitoring and Maintenance

Monitoring and maintenance are crucial for preserving data integrity, accuracy, and reliability. Monitoring involves continuous oversight of collected, stored, and processed data to detect anomalies or inconsistencies [

78]. Automated tools can track sources and issue real-time alerts for deviations from quality standards [

75,

90], supporting compliance with regulatory requirements for accurate and secure management [

18,

91]

Maintenance refers to ongoing activities that sustain and improve data quality [

92]. These include periodic cleansing and validation, updating outdated information, standardizing formats, and removing obsolete records to maintain relevance. Regular updates of data definitions and metadata ensure that stakeholders share a clear understanding of the data [

81]. Maintenance may also refine collection methods and incorporate feedback loops, allowing users to report issues and suggest improvements.

Both processes require collaboration among IT teams, data stewards, and business users [

93]. Clear communication channels, regular quality reviews, and training programs help ensure all stakeholders understand their roles [

94]. Together, monitoring and maintenance establish a proactive framework that keeps data a reliable asset for operations, planning, and analytics.

7.4. Governance/Ethics

Effective governance provides the foundation for maintaining sustainable data quality by defining clear roles, responsibilities, and procedures to ensure accountability throughout the data lifecycle. Leadership commitment and stewardship are crucial, as technical tools alone cannot guarantee reliability [

95]. Governance frameworks should also incorporate compliance with regulations, such as the GDPR, to mitigate legal and ethical risks.

An integrated data and AI governance model spans four phases: (1) data sourcing and preparation with ethical acquisition and bias detection, (2) model development with fairness-aware validation, (3) deployment and operations with drift monitoring, and (4) feedback and iteration to update policies dynamically [

96].. Automated checkpoints across these phases link data integrity with model ethics.

Responsible governance must extend beyond compliance to embed fairness, accountability, and inclusivity [

97].. Ethical lapses can erode trust, reinforce bias, and produce harmful outcomes in domains such as healthcare or finance [

98]. Embedding ethical principles within governance frameworks ensures data quality is evaluated not only for efficiency but also for societal impact.

These concerns are amplified in large language models, where massive training datasets raise challenges of provenance, bias, and misuse. Robust governance of LLMs is therefore essential to prevent social and economic harm [

99]

8. Challenges and Proposed Solutions

Managing data quality in CRM systems presents challenges, including decentralized storage, inconsistent data entry, and limited integration of diverse data sources. Proposed solutions include standardizing collection procedures, using advanced integration tools, and implementing comprehensive management frameworks to strengthen accuracy and consistency [

7].

8.1. Technical Challenges

Technical obstacles stem from data heterogeneity, scale, and limited automation. Integrating multiple sources and processing large volumes of inconsistent or outdated information remain critical difficulties [

20]. These issues are exacerbated by web-based platforms and SaaS models, which aggregate data from various internal and external sources [

24]. Many organizations continues to rely on outdated or manual quality checks, which are inadequate given the volume and velocity of contemporary data [

18].

A further barrier is the lack of standardized terminology across sectors; Miller identified 262 distinct terms in the literature to describe aspects of data quality, which complicates interoperability and hinders the adoption of automated assurance tools. [

15] Addressing these challenges requires not only technical solutions but also harmonized frameworks that enable consistency and support effective, data-driven decision-making.

8.2. Organizational Challenges

The significance of data quality extends beyond technical systems to organizational processes, as illustrated by studies showing that even computerized criminal records in the U.S. are often inaccurate or incomplete [

71]. Poor information quality undermines workflows by introducing inefficiencies and errors, highlighting the need to align process design with information system requirements from the outset [

25]. Common issues include inadequate data entry, poorly designed systems [

8], weak leadership commitment, and insufficient resource allocation.

AI adoption introduces new challenges. Automation of complex tasks can deskill experts, reducing their role to passive monitoring and eroding the valuable expertise they possess. The autonomy of AI systems also creates ambiguity over accountability—raising legal and ethical questions when errors occur. [

97]

A systematic review of Data Science projects identified 27 barriers grouped into six clusters: people, data and technology, management, economic, project, and external factors. The most frequently cited included insufficient skills, lack of management support, poor data quality, and misalignment between project goals and company objectives [

100]. Addressing these barriers requires comprehensive governance, continuous training, and systematic frameworks for handling and interpreting data [

22].

Perfect data quality is neither achievable nor cost-effective. Organizations should instead pursue the “right level” of quality, balancing maintenance efforts against the costs of poor quality [

101]. For large datasets, the marginal benefits of further improvements diminish over time [

33]. Relevance is another concern: as business needs evolve, datasets may lose strategic value, and silos that isolate data within departments hinder efficient decision-making [

102,

103].

Organizational disconnection between process design and quality management exacerbates these issues. Too often, quality checks are retrofitted after processes are implemented, which increases costs and the risk of failure [

25]. Embedding quality frameworks directly into workflows ensures validation mechanisms are integral rather than peripheral. The reuse of predefined process fragments provides a systematic way to integrate checks, reduce errors, and enhance reliability [

28]

Public administration research confirms that technology alone does not ensure high-quality information. Shortcomings such as insufficient training, weak governance, and organizational inefficiencies limit outcomes, underscoring that data quality challenges in government are rooted as much in people and structures as in systems [

29].

8.3. Solutions

Organizations can address data quality challenges by adopting advanced, automated tools, including AI and machine learning. These technologies enable continuous monitoring, anomaly detection, and large-scale validation that surpass the capabilities of manual methods. Recent work demonstrates the potential of multi-agent AI systems, where “planner” and “executor” agents automatically generate and execute PySpark validation code from natural language prompts, adapting to evolving data sources.[

104]. However, user acceptance remains a barrier: a survey of an AI-generated e-commerce platform (ChatGPT-4 and DALL·E 3) revealed concerns about security and trust despite positive evaluations of functionality and aesthetics [

105].

Effective solutions also require developing business-relevant quality metrics to guide decision-making and improvement strategies. AI-based frameworks can support Business Intelligence (BI) and Decision Support Systems (DSS) through layered architectures: data ingestion, quality assessment (e.g., Isolation Forests, BERT), cleansing and correction (e.g., KNN, LSTM), and monitoring with feedback loops [

106]. Predictive approaches, such as XGBoost, can correct anomalies across multiple dimensions (accuracy, completeness, conformity, uniqueness, consistency, and readability), improving composite Data Quality Index scores from 70% to over 90% in large-scale applications [

107].

Beyond technology, sustainable quality depends on robust governance. Frameworks should define criteria for data relevance, ensure alignment with organizational objectives, and include regular audits to maintain validity [

56]. Engaging stakeholders in data management further strengthens the practical utility of collected information.

9. Discussion

9.1. Synthesis of Literature: What Is Agreed upon, What Is Debated

This review confirms the persistence of inconsistencies in defining and applying data quality dimensions across various sectors. Miller’s hierarchical model offers a promising path by harmonizing terminology and adding new dimensions relevant to modern contexts such as IoT and machine learning [

15]. At the same time, AI and machine learning are transforming governance by automating profiling, anomaly detection, and metadata management, reducing manual intervention and improving compliance. However, a systematic review of 151 tools found that most prepare “data quality for AI,” while few exploit “AI for data quality” [

108], exposing a gap between current market offerings and the need for intelligent, automated DQM.

The FAIR principles—Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable—provide a widely recognized foundation for transparent management [

109]. Applied not only to data but also to software, they ensure reproducibility by making workflows, tools, and dependencies openly accessible [

27,

110]. FAIR should be viewed as a flexible, community-driven framework designed to create “AI-ready” digital objects that machines can process with minimal human intervention [

111]. Aligning quality frameworks with FAIR thus enhances both reliability and cross-domain reuse of scientific outputs.

Despite progress, systematic analyses of repositories reveal significant shortcomings in quality assurance [

112]. The broader reproducibility crisis has eroded trust in science [

113], prompting calls for open science interventions that emphasize transparency in data practices to strengthen accountability [

114]. Together, these findings position data quality as integral to reproducibility, FAIR compliance, and ongoing scientific reform.

9.2. Emerging Trends and Lessons from Failures

Semantic-driven technologies, including ontologies and knowledge graphs, emphasize semantics as a standalone dimension of data quality [

20]. Ethical principles are increasingly embedded directly in AI systems through privacy-preserving algorithms such as federated learning and homomorphic encryption, which minimize risks by training or computing on distributed, encrypted data [

96]. This reflects a shift toward privacy-by-design architectures, making governance an integral part of technical systems.

Large Language Models (LLMs) extend this trend, enabling semantic-level assessments of data quality. Seabra demonstrated that LLMs can identify contextual anomalies in relational databases that are overlooked by rule-based methods [

114,

115]. Similarly, OpenAI’s DaVinci model has demonstrated the capacity to assess temporal, geographic, and technology coverage, reducing practitioner bias [

116]. Multi-agent frameworks further automate the lifecycle, generating and refining PySpark validation scripts with minimal human input [

104]. While these advances promise efficiency, they also raise ethical challenges. AI-driven governance must strike a balance between automation and safeguards, such as fairness and explainability [

76,

117], as algorithmic decision-making can amplify biases and erode accountability [

118,

119].

Hallucinations in LLMs exemplify the risks of poor data quality. Inadequate governance during training and evaluation—resulting from misuse, weak security, or poor-quality inputs—leads to actual errors [

99]. Empirical results show that GPT-3.5's hallucination rates rose from 3.2% with curated data to 19.4% with noisy inputs [

120], underscoring the importance of quality for reliability. Governance frameworks that integrate ethical safeguards [

119,

121] are therefore vital to sustaining trust.

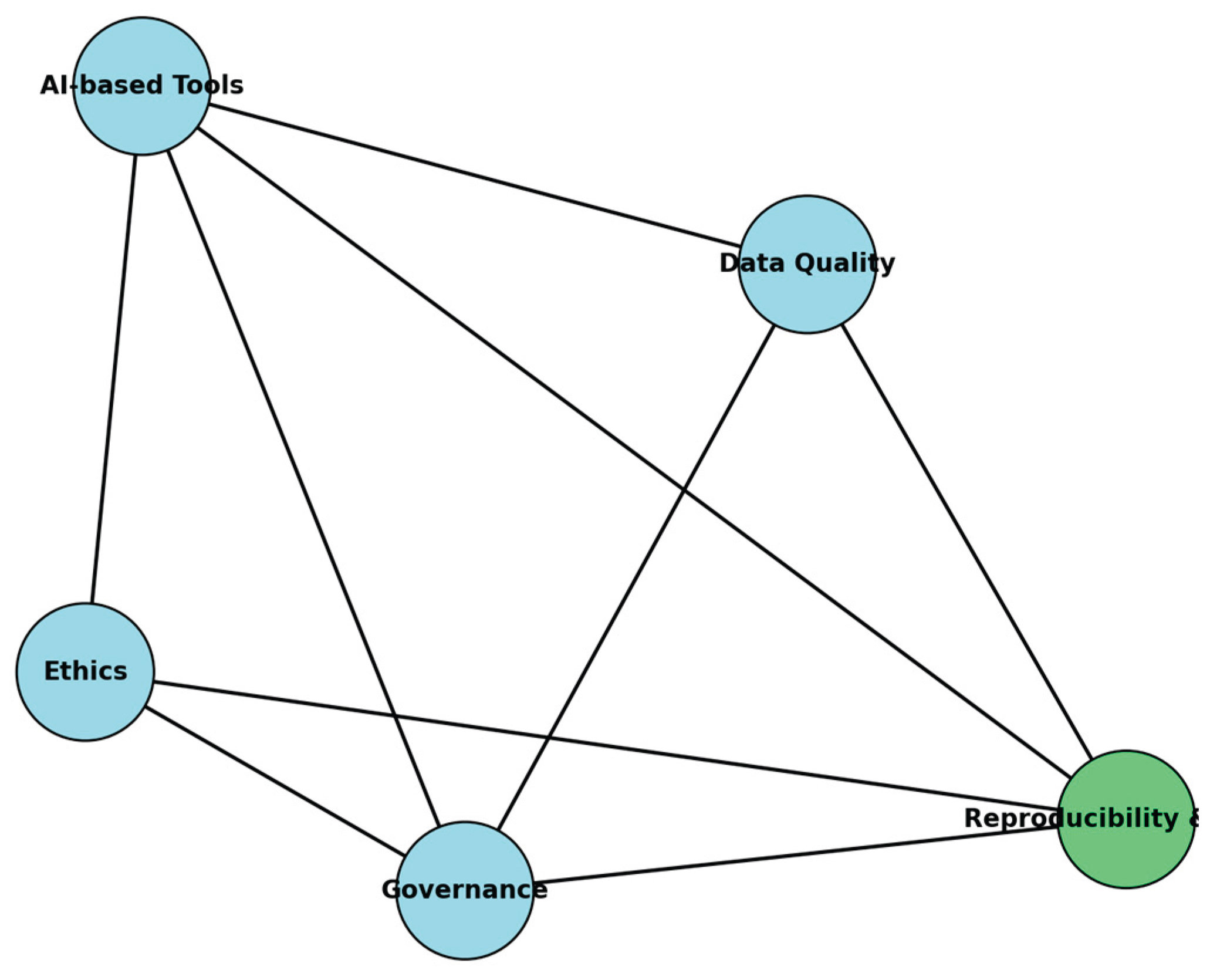

Figure 2 illustrates these interactions, showing governance as a mediator between technical tools, organizational practices, and ethical safeguards.

Failures provide further lessons. Poor timeliness, granularity, or completeness consistently impair CRM analytics. For example, a study reported that 64% of customer data had a timeliness score of ≤0.3, producing outdated segmentation and ineffective campaigns [

20]. Such cases reinforce that sustainable progress depends on continuous monitoring, systematic validation, and robust governance. Regulatory penalties and reputational damage highlight the cost of neglect [

8]. These lessons show that innovation must be coupled with organizational learning to avoid recurring pitfalls.

9.3. Research Gaps

Despite progress, key gaps remain. The organizational dimension of information quality in public administration is underexplored, as governance structures, staff skills, and administrative processes strongly influence reliability, but are mainly insufficiently studied [

29]. Promising theoretical tools, such as sixtuple information theory and rough set approaches, are still confined to narrow domains like judicial documents [

31], requiring testing in broader contexts (healthcare, publishing, administration).

Measurement standards also lack harmonization. The WHO’s Data Quality Review toolkit [

122] proposes a facility-level framework, but adoption remains uneven across regions, while sector-specific standards remain fragmented. In healthcare, real-world data often lack standardized definitions, which hinders analytics and research [

123]. Qualitative work in Ethiopian public facilities reveals that inadequate training and infrastructure compromise timeliness, completeness, and accuracy [

124], underscoring persistent vulnerabilities in the public sector.

Similarly, SMEs remain underexplored. A study of 85 UK SMEs found that deficits in technical skills and resources limit the adoption of robust practices [

125]. More comprehensive empirical research is needed to determine whether current frameworks effectively support data-driven decision-making in resource-constrained settings.

9.4. Implications for Practitioners and Policymakers

For practitioners, embedding quality mechanisms directly into business process models offers a sustainable approach to governance. Validation and monitoring should be intrinsic to workflows rather than external add-ons [

26]. Reusable “information quality fragments” reduce modeling time, provide explicit checkpoints, and increase confidence, while their validation by domain experts demonstrates feasibility [

28].

For policymakers and standard setters, these insights underscore the importance of explicit data quality validation in process modeling guidelines to mitigate systemic risks. Embedding FAIR principles—ensuring data are Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable—remains a practical pathway toward reproducibility and accountability in research [

7]. Incorporating FAIR into governance frameworks not only ensures compliance with regulatory and ethical standards but also enhances the long-term value of datasets through greater reusability [

126].

10. Conclusions

This review demonstrates that data quality is a multidimensional concept that extends beyond technical accuracy to include contextual, representational, and accessibility dimensions, as well as emerging attributes such as governance and semantics. Its central contribution has been to connect classic theoretical frameworks with real-world case studies and contemporary challenges in governance, ethics, and artificial intelligence. Ensuring data quality is therefore not only a technical task but also a strategic and socio-organizational imperative for scientific reproducibility and organizational trust.

The literature consistently demonstrates that poor data quality undermines decision-making, wastes resources, erodes trust, and yields harmful outcomes. Case studies from finance, healthcare, logistics, and aerospace confirm the pervasive and costly consequences of inadequate quality. Effective practices cannot rely solely on post-hoc cleaning but must embed validation and governance across the whole data lifecycle—from collection to continuous monitoring and ethical oversight. Standards such as ISO 8000 and ISO 25012, as well as newer hierarchical models, provide practical foundations; however, fragmentation in terminology and uneven adoption persist.

Key challenges remain: the proliferation of heterogeneous data sources, the velocity of big data, and entrenched organizational silos. While AI-driven validation tools and governance frameworks offer promising solutions, cost–benefit trade-offs often prevent systematic adoption.

For practitioners, high-quality data should be treated as a strategic asset. For researchers and policymakers, stronger integration with data ethics and greater attention to underexplored contexts such as healthcare systems and SMEs are urgently needed.

Finally, aligning practices with the FAIR principles—ensuring data are Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable [

7] —reinforces transparency, reproducibility, and long-term societal impact.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, EAO, FGG, and IAO; methodology, EAO, FGG, and IAO; formal analysis, FGG and IAO; investigation, MGA and LGA; resources, EAO; data curation, MGA and LGA; writing—original draft preparation, MGA and LGA; writing—review and editing, EAO, FGG, IAO, MGA, and LGA; visualization, MGA and LGA; supervision, FGG and IAO; project administration, FGG and IAO. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Full Term |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| BERT |

Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| BI |

Business Intelligence |

| CLV |

Customer Lifetime Value |

| CRM |

Customer Relationship Management |

| DQA |

Data Quality Assessment |

| DQI |

Data Quality Index |

| DQM |

Data Quality Management |

| DSAN |

Denoising Self-Attention Network |

| DSS |

Decision Support Systems |

| ECCMA |

Electronic Commerce Code Management Association |

| FAIR |

Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability |

| FAIR4RS |

FAIR for Research Software |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| ISO |

International Organization for Standardization |

| KNN |

K-Nearest Neighbors |

| LLMs |

Large Language Models |

| LSTM |

Long Short-Term Memory |

| NATO |

North Atlantic Treaty Organization |

| NCS |

NATO Codification System |

| RFM |

Recency, Frequency, and Monetary |

| SaaS |

Software as a Service |

| SMEs |

Small and Medium-sized Enterprises |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Bernardi, F.; Andrade Alves, D.; Crepaldi, N. Y.; Yamada, D. B.; Lima, V.; Costa Rijo, R. P. C. L. Data Quality in Health Research: A Systematic Literature Review [PrePrint]. medRxiv 2022.

- Elahi, E. Data quality in healthcare – Benefits, challenges, and steps for improvement https://dataladder.com/data-quality-in-healthcare-data-systems/ (accessed 2024 -08 -16).

- Ali, S. M.; Naureen, F.; Noor, A.; Kamel Boulos, M. N.; Aamir, J.; Ishaq, M.; Anjum, N.; Ainsworth, J.; Rashid, A.; Majidulla, A.; Fatima, I. Data Quality: A Negotiator between Paper-Based and Digital Records in Pakistan’s TB Control Program. Data (Basel) 2018, 3 (3), 27. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hailey, D.; Wang, N.; Yu, P. A Review of Data Quality Assessment Methods for Public Health Information Systems. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014, 11 (5), 5170–5207. [CrossRef]

- ISO 8000-1:2022(en). Data quality — Part 1: Overview https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:8000:-1:ed-1:v1:en (accessed 2025 -08 -20).

- ECCMA. What is ISO 8000? https://eccma.org/what-is-iso-8000/ (accessed 2025 -08 -20).

- Wilkinson, M. D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, Ij. J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.-W.; da Silva Santos, L. B.; Bourne, P. E.; Bouwman, J.; Brookes, A. J.; Clark, T.; Crosas, M.; Dillo, I.; Dumon, O.; Edmunds, S.; Evelo, C. T.; Finkers, R.; Gonzalez-Beltran, A.; Gray, A. J. G.; Groth, P.; Goble, C.; Grethe, J. S.; Heringa, J.; ’t Hoen, P. A. C.; Hooft, R.; Kuhn, T.; Kok, R.; Kok, J.; Lusher, S. J.; Martone, M. E.; Mons, A.; Packer, A. L.; Persson, B.; Rocca-Serra, P.; Roos, M.; van Schaik, R.; Sansone, S.-A.; Schultes, E.; Sengstag, T.; Slater, T.; Strawn, G.; Swertz, M. A.; Thompson, M.; van der Lei, J.; van Mulligen, E.; Velterop, J.; Waagmeester, A.; Wittenburg, P.; Wolstencroft, K.; Zhao, J.; Mons, B. The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship. Sci Data 2016, 3 (1), 160018. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. Y.; Strong, D. M. Beyond Accuracy: What Data Quality Means to Data Consumers. Journal of Management Information Systems 1996, 12 (4), 5–33. [CrossRef]

- Strong, D. M.; Lee, Y. W.; Wang, R. Y. Data Quality in Context. Commun ACM 1997, 40 (5), 103–110. [CrossRef]

- Benson, P. NATO Codification System as the Foundation for ISO 8000, the International Standard for Data Quality. Oil IT Journal 2008, 1 (5), 1–4.

- ISO 8000-8:2015. Data Quality — Part 8: Information and Data Quality: Concepts and Measuring. Geneva, Switzerland 2015.

- ISO 8000-110:2009. Data Quality — Part 110: Master Data: Exchange of Characteristic Data: Syntax, Semantic Encoding, and Conformance to Data Specification. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland 2009.

- ISO 8000-1:2011. Data Quality — Part 1: Overview. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland 2011.

- Miller, R.; Whelan, H.; Chrubasik, M.; Whittaker, D.; Duncan, P.; Gregório, J. A Framework for Current and New Data Quality Dimensions: An Overview. Data (Basel) 2024, 9 (12), 151. [CrossRef]

- Pipino, L. L.; Lee, Y. W.; Wang, R. Y. Data Quality Assessment. Commun ACM 2002, 45 (4), 211–218. [CrossRef]

- Ehrlinger, L.; Wöß, W. A Survey of Data Quality Measurement and Monitoring Tools. Front Big Data 2022, 5. [CrossRef]

- Haug, A.; Zachariassen, F.; van Liempd, D. The Costs of Poor Data Quality. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management 2011, 4 (2), 168–193.

- Suh, Y. Exploring the Impact of Data Quality on Business Performance in CRM Systems for Home Appliance Business. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 116076–116089. [CrossRef]

- Canali, S. Towards a Contextual Approach to Data Quality. Data (Basel) 2020, 5 (4), 90. [CrossRef]

- Payton, F. C.; Zahay, D. Understanding Why Marketing Does Not Use the Corporate Data Warehouse for CRM Applications. Journal of Database Marketing & Customer Strategy Management 2003, 10 (4), 315–326. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, D.; Earley, S.; Sykora, E.; Smith, E. DAMA -DMBOOK Data Management Body of Knowledge, Second Edition.; DAMA International: Basking Ridge, NJ, 2017.

- Bidlack, C.; Wellman, M. P. Exceptional Data Quality Using Intelligent Matching and Retrieval. AI Mag 2010, 31 (1), 65–73. [CrossRef]

- Vaknin, M.; Filipowska, A. Information Quality Framework for the Design and Validation of Data Flow Within Business Processes - Position Paper; 2017; pp 158–168. [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M. Data Quality in Customer Relationship Management (CRM): Literature Review. Strategic Management 2020, 25 (2), 40–47. [CrossRef]

- Even, A.; Shankaranarayanan, G.; Berger, P. D. Evaluating a Model for Cost-Effective Data Quality Management in a Real-World CRM Setting. Decis Support Syst 2010, 50 (1), 152–163. [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, N.; Negrao Carvalho, R.; Štotl, I. A FAIR Perspective on Data Quality Frameworks. Data (Basel) 2025, 10 (9), 136. [CrossRef]

- Lamprecht, A.-L.; Garcia, L.; Kuzak, M.; Martinez, C.; Arcila, R.; Martin Del Pico, E.; Dominguez Del Angel, V.; van de Sandt, S.; Ison, J.; Martinez, P. A.; McQuilton, P.; Valencia, A.; Harrow, J.; Psomopoulos, F.; Gelpi, J. Ll.; Chue Hong, N.; Goble, C.; Capella-Gutierrez, S. Towards FAIR Principles for Research Software. Data Science 2020, 3 (1), 37–59. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C. S.; Silveira, D. S. da; Araujo, J. Business Processes Fragments to Promote Information Quality. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 2021, 38 (9), 1880–1901. [CrossRef]

- Oliychenko, I.; Ditkovska, M. Improving Information Quality in E-Government of Ukraine. Electronic Government, an International Journal 2023, 19 (2), 146. [CrossRef]

- Jianfeng, X.; Jun, T.; Xuefeng, M.; Bin, X.; Yanli, S.; Yongjie, Q. Objective Information Theory: A Sextuple Model and 9 Kinds of Metrics. 2014.

- Lian, H.; He, T.; Qin, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, J. Research on the Information Quality Measurement of Judicial Documen. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability and Security Companion (QRS-C; IEEE, Ed.; IEEE: Lisbon, 2018; pp 177–181.

- Chue Hong, N. P. .; Aragon, S.; Hettrick, S.; Jay, C. The Future of Research Software Is the Future of Research. Patterns 2025, 6 (7), 101322. [CrossRef]

- Foote, K. The Impact of Poor Data Quality (and How to Fix It) https://www.dataversity.net/the-impact-of-poor-data-quality-and-how-to-fix-it/ (accessed 2024 -08 -26).

- Henderson, D.; Earley, S.; Sykora, E.; Smith, E. Data Quality. In DAMA -DMBOOK Data Management Body of Knowledge; Henderson, D., Earley, S., Sykora, E., Smith, E., Eds.; DAMA International: Basking Ridge, NJ, 2017; pp 551–611.

- Schäffer, T.; Beckmann, H. Trendstudie Stammdatenqualität 2013: Erhebung Der Aktuellen Situation Zur Stammdatenqualität in Unternehmen Und Daraus Abgeleitete Trends [Trend StudyMaster Data Quality 2013: Inquiry of the Current Situation of Master Data Quality in Companies and Derived Trends].; Steinbeis-Edition: Stuttgart, 2014.

- Alshawi, S.; Missi, F.; Irani, Z. Organisational, Technical and Data Quality Factors in CRM Adoption — SMEs Perspective. Industrial Marketing Management 2011, 40 (3), 376–383. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C. W.; Lauria, E. J. M.; Matheus, C. C. An Accuracy Metric. Journal of Data and Information Quality 2009, 1 (3), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zeng, W.; Zhu, L.; Wu, X.; Li, D. A Novel Proposal for Improving Economic Decision-Making Through Stock Price Index Forecasting. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2024, 15 (4). [CrossRef]

- Kelka, H. Supply Chain Resilience Navigating Disruptions Through Strategic Inventory Management, Metropolia University of Applied Sciences, Helsinki, 2024.

- Al-Harrasi, A. S.; Adarbah, H. Y.; Al-Badi, A. H.; Shaikh, A. K.; Al-Shihi, H.; Al-Barrak, ِa. Exploring the Adoption of Big Data Analytics in the Oil and Gas Industry: A Case Study. Journal of Business, Communication & Technology 2024, 1–16.

- Joseph, M.; Kumar, D. P.; Keerthana, J. K. Stock Market Analysis and Portfolio Management. In 2024 11th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions) (ICRITO); IEEE, 2024; pp 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Purohit, P.; Al Nuaimi, F.; Nakkolakkal, S. Data Governance, Privacy, Data Sharing Challenges. In Day 2 Wed, May 08, 2024; SPE, 2024. [CrossRef]

- UTradeAlgos. The Importance of Real-Time Data in Algo Trading Software https://utradealgos.com/blog/the-importance-of-real-time-data-in-algo-trading-software/ (accessed 2024 -08 -27).

- Bernard Owusu Antwi; Beatrice Oyinkansola Adelakun; Augustine Obinna Eziefule. Transforming Financial Reporting with AI: Enhancing Accuracy and Timeliness. International Journal of Advanced Economics 2024, 6 (6), 205–223. [CrossRef]

- Chioma Susan Nwaimo; Ayodeji Enoch Adegbola; Mayokun Daniel Adegbola; Kudirat Bukola Adeusi. Evaluating the Role of Big Data Analytics in Enhancing Accuracy and Efficiency in Accounting: A Critical Review. Finance & Accounting Research Journal 2024, 6 (6), 877–892. [CrossRef]

- Judijanto, L.; Edtiyarsih, D. D. The Effect of Company Policy, Legal Compliance, and Information Technology on Audit Report Accuracy in the Textile Industry in Tangerang. West Science Accounting and Finance 2024, 2 (02), 287–298. [CrossRef]

- Ehsani-Moghaddam, B.; Martin, K.; Queenan, J. A. Data Quality in Healthcare: A Report of Practical Experience with the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network Data. Health Information Management Journal 2021, 50 (1–2), 88–92. [CrossRef]

- Lorence, D. Measuring Disparities in Information Capture Timeliness Across Healthcare Settings: Effects on Data Quality. J Med Syst 2003, 27 (5), 425–433. [CrossRef]

- Mashoufi, M.; Ayatollahi, H.; Khorasani-Zavareh, D.; Talebi Azad Boni, T. Data Quality in Health Care: Main Concepts and Assessment Methodologies. Methods Inf Med 2023, 62 (01/02), 005–018. [CrossRef]

- WAGER, K. A.; SCHAFFNER, M. J.; FOULOIS, B.; SWANSON KAZLEY, A.; PARKER, C.; WALO, H. Comparison of the Quality and Timeliness of Vital Signs Data Using Three Different Data-Entry Devices. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing 2010, 28 (4), 205–212. [CrossRef]

- Alzghoul, A.; Khaddam, A. A.; Abousweilem, F.; Irtaimeh, H. J.; Alshaar, Q. How Business Intelligence Capability Impacts Decision-Making Speed, Comprehensiveness, and Firm Performance. Information Development 2024, 40 (2), 220–233. [CrossRef]

- Kusumawardhani, F. K.; Ratmono, D.; Wibowo, S. T.; Darsono, D.; Widyatmoko, S.; Rokhman, N. The Impact of Digitalization in Accounting Systems on Information Quality, Cost Reduction and Decision Making: Evidence from SMEs. International Journal of Data and Network Science 2024, 8 (2), 1111–1116. [CrossRef]

- GOV.UK. Hidden costs of poor data quality Tackling data quality saves money and reduces risk.

- Sattler, K.-U. Data Quality Dimensions. In Encyclopedia of Database Systems; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2016; pp 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Black, A.; van Nederpelt, P. Dimensions of Data Quality (DDQ) Research Paper; Herveld, Netherlands, 2020.

- Chen, B. What is Data Relevance? Definition, Examples, and Best Practices https://www.metaplane.dev/blog/data-relevance-definition-examples (accessed 2024 -08 -27).

- IBM. What is data quality?

- Enterprise Big Data Framework. Understanding Data Quality: Ensuring Accuracy, Reliability, and Consistency https://www.bigdataframework.org/knowledge/understanding-data-quality/ (accessed 2024 -08 -27).

- Ibrahim, A.; Mohamed, I.; Satar, N. S. M.; Hasan, M. K. Master Data Quality Management Framework: Content Validity. Scalable Computing: Practice and Experience 2024, 25 (3), 2001–2012. [CrossRef]

- Houston, M. B. Assessing the Validity of Secondary Data Proxies for Marketing Constructs. J Bus Res 2004, 57 (2), 154–161. [CrossRef]

- Piedmont, R. L. Construct Validity. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp 1332–1332. [CrossRef]

- Van Iddekinge, C. H.; Ployhart, R. E. Developments in the Criterion-related Validation of Selection Procedures: A Critical Review and Recommendations for Practice. Pers Psychol 2008, 61 (4), 871–925. [CrossRef]

- Collibra. The 6 data quality dimensions with examples www.collibra.com/us/en/blog/the-6-dimensions-of-data-quality (accessed 2024 -08 -27).

- Okembo, C.; Morales, J.; Lemmen, C.; Zevenbergen, J.; Kuria, D. A Land Administration Data Exchange and Interoperability Framework for Kenya and Its Significance to the Sustainable Development Goals. Land (Basel) 2024, 13 (4), 435. [CrossRef]

- Ellul, C.; Reynolds, P.; Vilardo, L. (M)App My Data! Developing a Map-Ability Rating and App to Rapidly Communicate Data Quality and Interoperability Potential of Open Data. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2024, X-4/W4-2024, 49–56. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Harmouch, H.; Naumann, F.; Srivastava, D. Data Quality Assessment: Challenges and Opportunities. 2024.

- Terzi, S.; Stamelos, I. Architectural Solutions for Improving Transparency, Data Quality, and Security in EHealth Systems by Designing and Adding Blockchain Modules, While Maintaining Interoperability: The EHDSI Network Case. Health Technol (Berl) 2024, 14 (3), 451–462. [CrossRef]

- Bammidi, T.; Gutta, L.; Kotagiri, A.; Samayamantri, L.; Vaddy, R. The Crucial Role of Data Quality in Automated Decision-Making Systems. International Journal of Management Education for Sustainable Development 2024, 7 (7), 1–22.

- Yandrapalli, V. AI-Powered Data Governance: A Cutting-Edge Method for Ensuring Data Quality for Machine Learning Applications. In 2024 Second International Conference on Emerging Trends in Information Technology and Engineering (ICETITE); IEEE, 2024; pp 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Brahimi, S.; Elhussein, M. Measuring the Effect of Fraud on Data-Quality Dimensions. Data (Basel) 2023, 8 (8), 124. [CrossRef]

- Gartner INC. Data Quality: Why It Matters and How to Achieve It https://www.gartner.com/en/data-analytics/topics/data-quality (accessed 2025 -08 -20).

- Ambler, S. W. Data Quality: The Impact of Poor Data Quality https://agiledata.org/essays/impact-of-poor-data-quality.html (accessed 2025 -08 -20).

- Gregory, D. Data quality issues (causes & consequences) | Ataccama https://www.ataccama.com/blog/data-quality-issues-causes-consequences (accessed 2025 -08 -20).

- MacIntyre, L. The Cost of Incomplete Data: Businesses Lose $3 Trillion Annually - Enricher.io https://enricher.io/blog/the-cost-of-incomplete-data (accessed 2025 -08 -20).

- Delpha. The Impacts of Bad Data Quality; Paris, 2021.

- Forrest, S. Study examines accuracy of arrest data in FBI’s NIBRS crime database https://phys.org/news/2022-02-accuracy-fbi-nibrs-crime-database.html (accessed 2024 -08 -15).

- Gates, S. 5 Examples of Bad Data Quality in Business — And How to Avoid Them https://www.montecarlodata.com/blog-bad-data-quality-examples/ (accessed 2024 -08 -26).

- Nagle, T.; Redman, T. C.; Sammon, D. Only 3% of Companies’ Data Meets Basic Quality Standards. Harv Bus Rev 2017.

- Elahi, E. The impact of poor data quality: Risks, challenges, and solution https://dataladder.com/the-impact-of-poor-data-quality-risks-challenges-and-solutions/ (accessed 2024 -08 -26).

- MacDonald, L. Measuring Data Quality: Key Metrics, Processes, and Best Practices https://www.montecarlodata.com/blog-measuring-data-quality-key-metrics-processes-and-best-practices/ (accessed 2024 -08 -27).

- Mahendra, P.; Doshi, P.; Verma, A.; Shrivastava, S. A Comprehensive Review of AI and ML in Data Governance and Data Quality. In 2025 3rd International Conference on Inventive Computing and Informatics (ICICI); IEEE, 2025; pp 01–06. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, N. The cost of poor data quality on business operations https://lakefs.io/blog/poor-data-quality-business-costs/#:~:text=What%20is%20the%20business%20cost,lead%20to%20inaccurate%20decision%2Dmaking. (accessed 2024 -08 -26).

- Biemer, P. P. Data Quality and Inference Errors. In Big Data and Social Science Data Science Methods and Tools for Research and Practice; Foster, I., Ghani, R., Jarmin, R., Kreuter, F., Lane, J., Eds.; CRC: Boca Raton, Florida, 2020.

- Butler, D. When Google Got Flu Wrong. Nature 2013, 494 (7436), 155–156. [CrossRef]

- Lazer, D.; Kennedy, R.; King, G.; Vespignani, A. The Parable of Google Flu: Traps in Big Data Analysis. Science (1979) 2014, 343 (6176), 1203–1205. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Applications and Challenges of Big Data in Market Analytics. Transactions on Economics, Business and Management Research 2024, 9, 450–458. [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Kumar, V.; Mittal, A.; Rathore, B.; Jha, A.; Rahman, M. S. The Role of 3S in Big Data Quality: A Perspective on Operational Performance Indicators Using an Integrated Approach. The TQM Journal 2023, 35 (1), 153–182. [CrossRef]

- Marzullo, A.; Savevski, V.; Menini, M.; Schilirò, A.; Franchellucci, G.; Dal Buono, A.; Bezzio, C.; Gabbiadini, R.; Hassan, C.; Repici, A.; Armuzzi, A. Collecting and Analyzing IBD Clinical Data for Machine-Learning: Insights from an Italian Cohort. Data (Basel) 2025, 10 (7), 100. [CrossRef]

- Tlouyamma, J.; Mokwena, S. Automated Data Quality Control System in Health and Demographic Surveillance System. Science, Engineering and Technology 2024, 4 (2), 82–91. [CrossRef]

- Pykes, K. 10 Signs of Bad Data: How to Spot Poor Quality Data https://www.datacamp.com/blog/10-signs-bad-data-quality (accessed 2024 -08 -26).

- Fu, A.; Shen, T.; Roberts, S. B.; Liu, W.; Vaidyanathan, S.; Marchena-Romero, K.-J.; Lam, Y. Y. P.; Shah, K.; Mak, D. Y. F.; Chin, S.; Stern, S. J.; Koppula, R.; Joyce, L. F.; Pellegrino, N.; Harris, N.; Ng, V.; Srivastava, S.; Manikan, N.; Wilkinson, A.; Gastmeier, J.; Kwan, J. C.; Byaruhanga, H.; Shaji, L.; George, S.; Handsor, S.; Roy, R. A.; Kim, C. S.; Mequanint, S.; Razak, F.; Verma, A. A. Optimizing the Efficiency and Effectiveness of Data Quality Assurance in a Multicenter Clinical Dataset. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2025, 32 (5), 835–844. [CrossRef]

- Haverila, M. J.; Haverila, K. C. The Influence of Quality of Big Data Marketing Analytics on Marketing Capabilities: The Impact of Perceived Market Performance! Marketing Intelligence & Planning 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-H.; Kim, H. A Self-Attention-Based Imputation Technique for Enhancing Tabular Data Quality. Data (Basel) 2023, 8 (6), 102. [CrossRef]

- Becerra, M. A.; Tobón, C.; Castro-Ospina, A. E.; Peluffo-Ordóñez, D. H. Information Quality Assessment for Data Fusion Systems. Data (Basel) 2021, 6 (6), 60. [CrossRef]

- Sluzki, N. 8 Data Quality Monitoring Techniques & Metrics to Watch https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/data-quality-monitoring-techniques (accessed 2024 -08 -27).

- Karkošková, S. Data Governance Model To Enhance Data Quality In Financial Institutions. Information Systems Management 2023, 40 (1), 90–110. [CrossRef]

- Woods, C.; Selway, M.; Bikaun, T.; Stumptner, M.; Hodkiewicz, M. An Ontology for Maintenance Activities and Its Application to Data Quality. Semant Web 2024, 15 (2), 319–352. [CrossRef]

- Stepanenko, R. Data Stewardship Explained: The Backbone of Data Management https://recordlinker.com/data-stewardship-explained/ (accessed 2025 -09 -14).

- Jatin, B. Data Governance for Quality: Policies Ensuring Reliable Data https://www.decube.io/post/data-quality-data-governance (accessed 2024 -08 -27).

- Khatri, V.; Brown, C. V. Designing Data Governance. Commun ACM 2010, 53 (1), 148–152. [CrossRef]

- Duggireddy, G. B. R. Integrated Data and AI Governance Framework: A Lifecycle Approach to Responsible AI Implementation. Journal of Computer Science and Technology Studies 2025, 7 (7), 771–777.

- Papagiannidis, E.; Mikalef, P.; Conboy, K. Responsible Artificial Intelligence Governance: A Review and Research Framework. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 2025, 34 (2), 101885. [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L.; Taddeo, M. What Is Data Ethics? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2016, 374 (2083), 20160360. [CrossRef]

- Pahune, S.; Akhtar, Z.; Mandapati, V.; Siddique, K. The Importance of AI Data Governance in Large Language Models. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2025, 9 (6), 147. [CrossRef]

- Labarrère, N.; Costa, L.; Lima, R. M. Data Science Project Barriers—A Systematic Review. Data (Basel) 2025, 10 (8), 132. [CrossRef]

- Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority. Annual Audit Report for 1982-1983: Data Quality of Computerized Criminal Histories. ; National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS).: Springfield, 1983.

- Bosse, R. C.; Jino, M.; de Franco Rosa, F. A Study on Data Quality and Analysis in Business Intelligence; 2024; pp 249–253. [CrossRef]

- Sienkiewicz, M. From Data Silos to Data Mesh: A Case Study in Financial Data Architecture; 2026; pp 3–20. [CrossRef]

- Senguttuvan, KR. Multi-Agent Based Automated Data Quality Engineering, Fordham University, New York, 2025.

- Stamkou, C.; Saprikis, V.; Fragulis, G. F.; Antoniadis, I. User Experience and Perceptions of AI-Generated E-Commerce Content: A Survey-Based Evaluation of Functionality, Aesthetics, and Security. Data (Basel) 2025, 10 (6), 89. [CrossRef]

- Vanam, R. R.; Pingili, R.; Myadaboyina, S. G. AI-Based Data Quality Assurance for Business Intelligence and Decision Support Systems. International Journal of Emerging Trends in Computer Science and Information Technology 2025, 6, 21–29. [CrossRef]

- Elouataoui, W.; El Mendili, S.; Gahi, Y. An Automated Big Data Quality Anomaly Correction Framework Using Predictive Analysis. Data (Basel) 2023, 8 (12), 182. [CrossRef]

- Tamm, H. C.; Nikiforova, A. From Data Quality for AI to AI for Data Quality: A Systematic Review of Tools for AI-Augmented Data Quality Management in Data Warehouses. 2025.

- Stoudt, S.; Jernite, Y.; Marshall, B.; Marwick, B.; Sharan, M.; Whitaker, K.; Danchev, V. Ten Simple Rules for Building and Maintaining a Responsible Data Science Workflow. PLoS Comput Biol 2024, 20 (7), e1012232. [CrossRef]

- Mons, B.; Schultes, E.; Liu, F.; Jacobsen, A. The FAIR Principles: First Generation Implementation Choices and Challenges. Data Intell 2020, 2 (1–2), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Stvilia, B.; Pang, Y.; Lee, D. J.; Gunaydin, F. Data Quality Assurance Practices in Research Data Repositories—A Systematic Literature Review. An Annual Review of Information Science and Technology (ARIST) Paper. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol 2025, 76 (1), 238–261. [CrossRef]

- Korbmacher, M.; Azevedo, F.; Pennington, C. R.; Hartmann, H.; Pownall, M.; Schmidt, K.; Elsherif, M.; Breznau, N.; Robertson, O.; Kalandadze, T.; Yu, S.; Baker, B. J.; O’Mahony, A.; Olsnes, J. Ø.-S.; Shaw, J. J.; Gjoneska, B.; Yamada, Y.; Röer, J. P.; Murphy, J.; Alzahawi, S.; Grinschgl, S.; Oliveira, C. M.; Wingen, T.; Yeung, S. K.; Liu, M.; König, L. M.; Albayrak-Aydemir, N.; Lecuona, O.; Micheli, L.; Evans, T. The Replication Crisis Has Led to Positive Structural, Procedural, and Community Changes. Communications Psychology 2023, 1 (1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Dudda, L.; Kormann, E.; Kozula, M.; DeVito, N. J.; Klebel, T.; Dewi, A. P. M.; Spijker, R.; Stegeman, I.; Van den Eynden, V.; Ross-Hellauer, T.; Leeflang, M. M. G. Open Science Interventions to Improve Reproducibility and Replicability of Research: A Scoping Review. R Soc Open Sci 2025, 12 (4). [CrossRef]

- MacMaster, S.; Sinistore, J. Testing the Use of a Large Language Model (LLM) for Performing Data Quality Assessment. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2024. [CrossRef]

- Batool, A.; Zowghi, D.; Bano, M. AI Governance: A Systematic Literature Review. AI and Ethics 2025, 5 (3), 3265–3279. [CrossRef]

- Gebru, T.; Morgenstern, J.; Vecchione, B.; Vaughan, J. W.; Wallach, H.; III, H. D.; Crawford, K. Datasheets for Datasets. Commun ACM 2021, 64 (12), 86–92. [CrossRef]

- Leslie, D. Understanding Artificial Intelligence Ethics and Safety: A Guide for the Responsible Design and Implementation of AI Systems in the Public Sector. ; London, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A. R. Impact of High Data Quality on LLM Hallucinations. Int J Comput Appl 2025, 187 (4), 35–39. [CrossRef]

- Abhishek, A.; Erickson, L.; Bandopadhyay, T. Data and AI Governance: Promoting Equity, Ethics, and Fairness in Large Language Models. 2025. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Overview of the Data Quality Review (DQR) Frameworkand Methodology; Geneva, 2020.