Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

18 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Nanotechnology and Its Significance in Drug Delivery

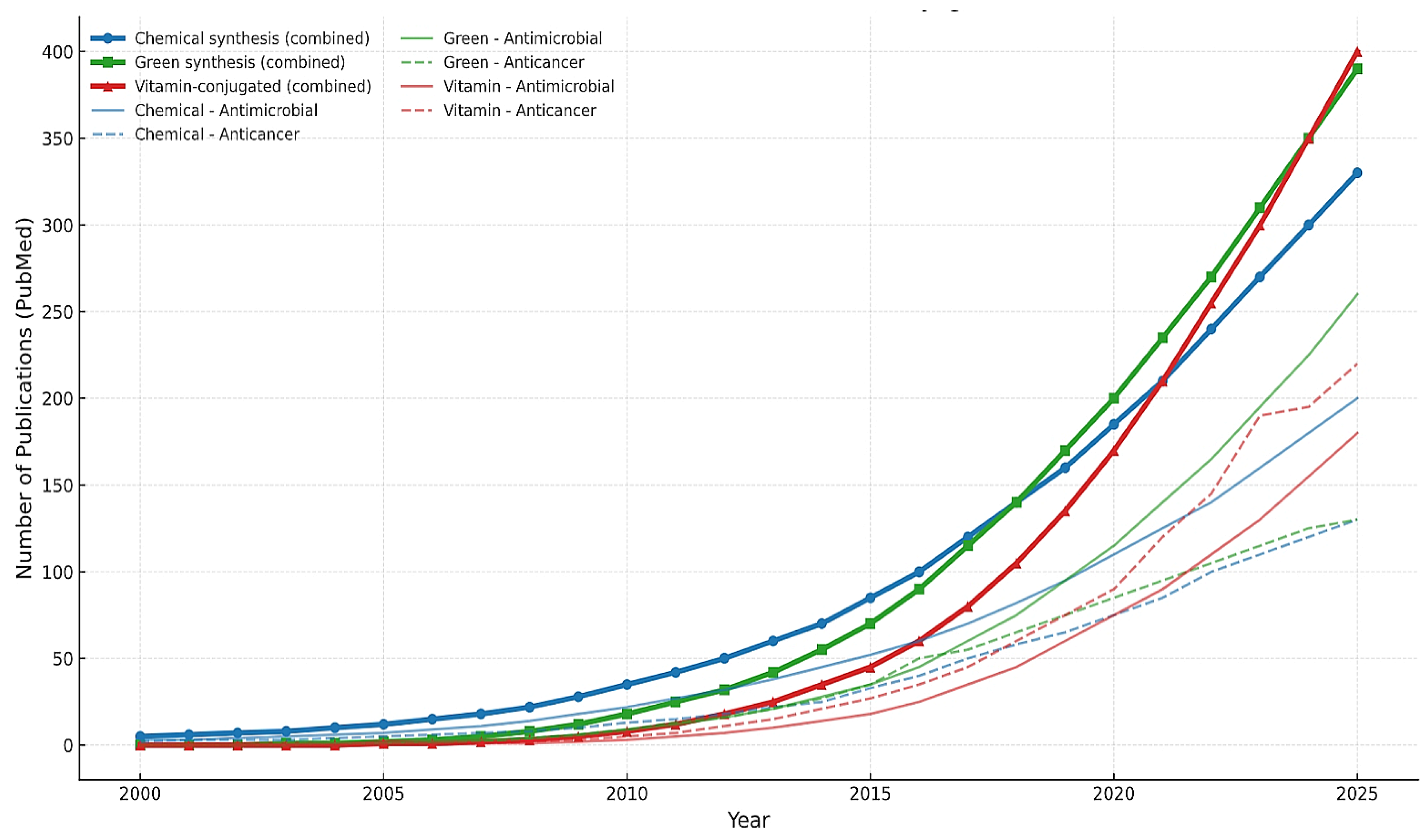

1.2. Vitamin Conjugated Metallic Nanoparticles

2. Methods of Metal Nanoparticles Synthesis

2.1. Chemical Approach

2.2. Greener Approach

2.3. Influence of Synthesis Parameters

3. Characterization Techniques of Nanoparticles

| S/N | Metal NP + Vitamin | Synthesis Method | Size & Morphology | Characterization Techniques | Applications | Key Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ag (Ag/Cu) + Ascorbic Acid | Chemical reduction | Ag: ~200–800 nm; Cu: ~160–630 nm spherical | UV–Vis, DLS, TEM | Antibacterial: Tested against Bacillus subtilis (Gram+) and E. coli (Gram–). | Strongest bactericidal effect (MIC ~0.05–0.08 mg/L). | [90] |

| 2 | Au + Vitamin C (with algal EPS) | Green biosynthesis | ~6–40 nm spherical AuNPs | UV–Vis, XRD, TEM, FTIR | Antibacterial: Multi-strain (E. coli, S. aureus, S. enterica, S. mutans, Candida spp.). Anticancer: Tested against MCF-7, A549, and CaCo-2 cells. | Most effective: >88% kill of E. coli and ~83% of S. aureus under light (via ROS generation), and ~70% growth inhibition of MCF-7 breast cancer cells. | [91] |

| 3 | CeO2 + Folic Acid | Green one-pot precipitation | ~21–28 nm polyhedral; DLS (hydrodynamic ~200 nm; 22 mV) | XRD, TEM/SEM | Antibacterial: Potent against MRSA. Antioxidant/Anti-inflammatory. Anticancer (MDA-MB-231). | Inhibit ~95.6% of MRSA growth, accelerated wound healing and selective toxicity toward bacteria and cancer cells. | [92] |

| 4 | Cu–MOF + Folic Acid (Cu-TCPP MOF/Pt-FA) | Chemical method | Nanosheets ~100–200 nm; Pt NPs ~2 nm | TEM/HRTEM, XRD, XPS, FTIR, Zeta potential | Anticancer (PDT & immunotherapy) | Greatly enhances PDT even in hypoxic conditions. | [93] |

| 5 | Cu2S + Vitamin C | Single-step aqueous synthesis (Chemical reduction) | CuS ~8–10 nm, quasi-spherical; agglomerates into 50–100 nm clusters | XRD, FTIR, TEM/SEM, EDS | Antibacterial (S. aureus, E. coli, K. pneumoniae), Antioxidant | Broad-spectrum bactericidal activity. MIC: ~2 mg/mL (E. coli) and 10 µg/mL (other strains). Also scavenged DPPH & NO radicals. | [94] |

| 6 | Fe3O4 + Riboflavin (B2) | Solvothermal method | ~200 nm spherical | XRD, XPS, Zeta potential, UV-Vis, Fluorescence | Antibacterial and Antioxidant | Kills >90% of S. aureus and ~88% of E. coli at 0.5 mg/mL. | [95] |

| 7 | Fe3O4 + Folic Acid (PLGA nanocarrier) | Double emulsion solvent evaporation | ~150–180 nm polymeric spheres (PLGA); Fe3O4 cores ~8 nm | TEM, DLS, FTIR, NMR, MRI | Anticancer | Induce ~90% cell death in ovarian cancer. | [96] |

| 8 | Fe3O4 + Folic/TNF/IFN/DOX | Surface functionalization & self-assembly | Fe3O4 core ~5 nm; clusters ~50 nm spherical | FTIR, DLS, UV–Vis | Anticancer (combined therapy) | Produced synergistic cancer cell killing with reduced systemic toxicity. | |

| 9 | Ag + Folic Acid (valve coating) | Biofunctional coating | ~10 nm AgNPs | SEM, EDS, FTIR | Antibacterial & anti-inflammatory implant | Reduced calcification and inflammation in vivo. | [97] |

| 10 | Ag/MOF + Folic Acid (nanocapsule) | Biopolymer-templated in situ MOF synthesis | ~320–350 nm mixture of rod-like and spherical particles | XRD, FTIR, SEM, TEM, BET | Antibacterial, antioxidant, targeted drug delivery | Single folate-targeted nanocapsule can deliver chemotherapeutics while preventing infection & oxidative damage. | [98] |

| 11 | Gd2O3 + Vitamin C | Biogenic precipitation | ~50 nm amorphous Gd2O3 particles | TEM, DLS, XPS, ICP | Antibacterial | Potent bactericidal effects against multiple pathogens. | [99] |

| 12 | Au + Riboflavin (B2) | Photochemical surface-modification | AuNP ~20 nm, spherical | UV–Vis | Photodynamic antimicrobial therapy (S. aureus, P. aeruginosa) | Vitamin B2 + AuNP create synergistic ROS + Au+ antibacterial effect. | [100] |

| 13 | Ag + α-Tocopherol Succinate (Vit E) | Surface functionalization | Ag core ~20 nm; hydrodynamic size ~25 nm (TOS coating) | UV–Vis, FTIR, DLS/Zeta potential | Anticancer (A549 lung carcinoma) | TOS coating enhanced cancer selectivity & therapeutic index of AgNPs. | [101] |

| 14 | Y2O3 + Folic Acid | Chemical synthesis/thermal decomposition | ~5–10 nm hexagonal phase; aggregates into ~100 nm clusters; folate-PEG ~120 nm | Photoluminescence, TEM, FTIR, DLS | Cancer imaging | Enabled precise NIR-triggered imaging & potential phototherapy. | [102] |

| 15 | Se + Vitamin C | Chemical reduction | ~50–60 nm spherical | UV–Vis, DLS, Zeta potential, XPS | Antibacterial | Strong activity against S. aureus; stabilized Se–VitC NPs retained activity 2–6 months. | [103] |

| 16 | Zn/Ag MOF + Vitamin C | Chemical synthesis with functionalization | ~100–200 nm polyhedral | XRD, TEM, SEM, FTIR, BET | Antibacterial | Strong activity against Gram+ and Gram– bacteria common in wound infections. | [104] |

| 17 | Fe/MOF + Riboflavin | Hydrothermal method | Uniform polyhedral morphology | TEM, DLS, Zeta potential, XRD, FTIR, SEM, EDS, UV-Vis, Thermal imaging | Treatment of bacterial keratitis (S. aureus, P. aeruginosa) | Rapid infection clearance with minimal collateral damage. | [105] |

| 18 | Ag NPs + Biotin, D-Pantothenic acid & Nicotinic acid | Chemical reduction with NaBH4 | ~10 nm spherical | UV-Vis, TEM, FTIR, DLS, TGA, FE-STEM | Antimicrobial | Effective at low concentrations (15.62–62.5 μg/mL) against planktonic cells & biofilms. | [106] |

4. Applications

4.1. Antimicrobial Applications

4.2. Anti-Cancer Applications

4.3. Other Emerging Applications

5. Mechanisms of Actions

5.1. Antimicrobial Mechanisms

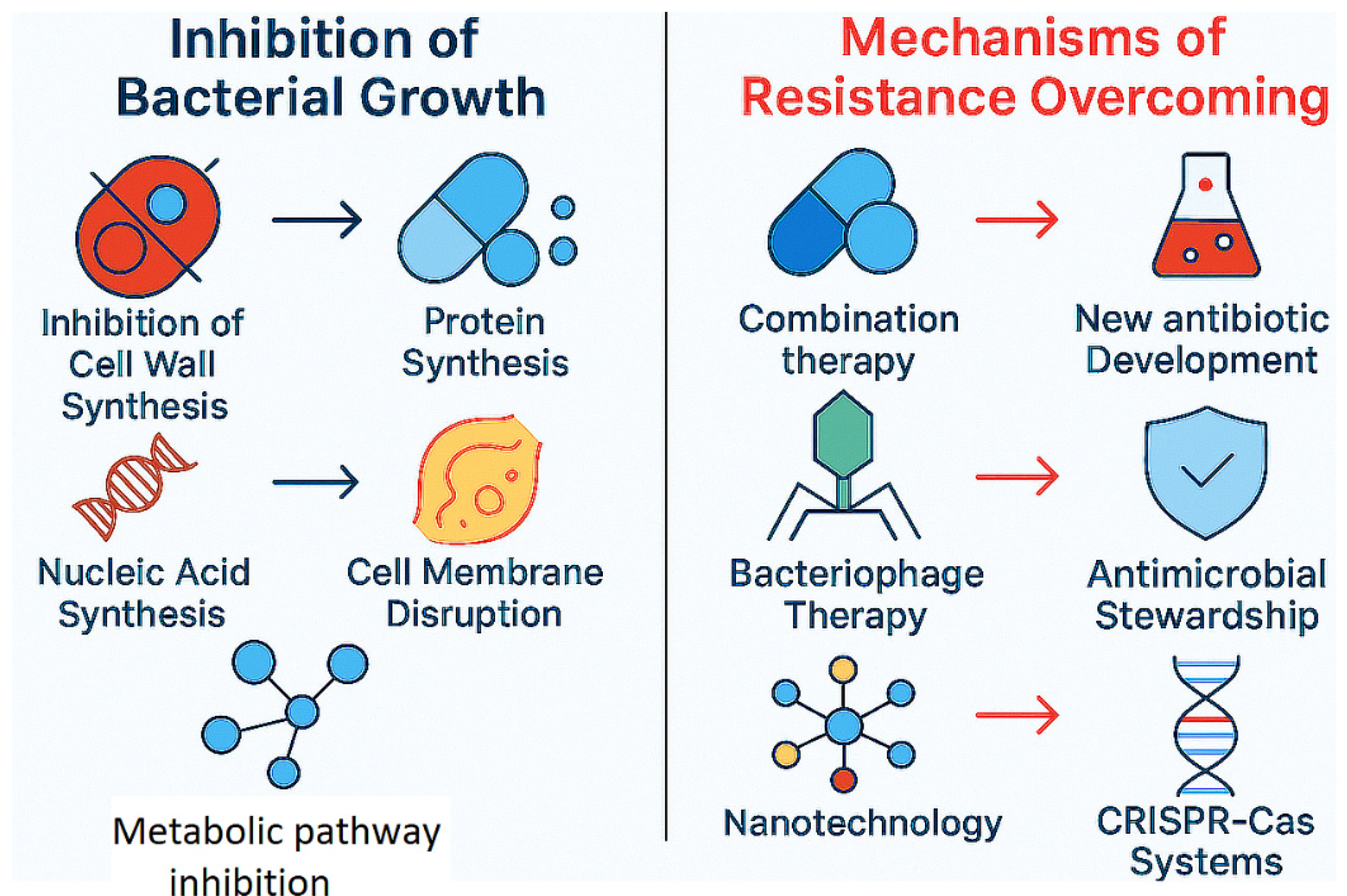

5.1.1. Inhibition of Bacterial Growth

5.1.2. Mechanisms of Resistance Overcoming

5.2. Anti-Cancer Mechanisms

5.2.1. Targeted Delivery to Tumors

5.2.2. Induction of Apoptosis in Cancer Cells

5.2.3. Mechanisms of Drug Resistance Modulation

5.3. Influence of Vitamin Functionalization

5.3.1. Enhanced Cellular Uptake

5.3.2. Improved Biocompatibility and Efficacy

6. Challenges and Limitations

7. Future Perspectives

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bayda, S.; Adeel, M.; Tuccinardi, T.; Cordani, M.; Rizzolio, F. The History of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology: From Chemical–Physical Applications to Nanomedicine. Molecules 2019, 25, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maghsoudnia, N.; Eftekhari, R.B.; Sohi, A.N.; Zamzami, A.; Dorkoosh, F.A. Application of Nano-Based Systems for Drug Delivery and Targeting: A Review. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2020, 22, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, W.; Chu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, N. A Review on Nano-Based Drug Delivery System for Cancer Chemoimmunotherapy. Nano-Micro Lett. 2020, 12, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, J.A.; Witzigmann, D.; Thomson, S.B.; Chen, S.; Leavitt, B.R.; Cullis, P.R.; Van Der Meel, R. The Current Landscape of Nucleic Acid Therapeutics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.A.; Jalouli, M.; Yadab, M.K.; Al-Zharani, M. Progress in Drug Delivery Systems Based on Nanoparticles for Improved Glioblastoma Therapy: Addressing Challenges and Investigating Opportunities. Cancers 2025, 17, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim Khan, K.S.; Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, Applications and Toxicities. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, D. Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Systems: Strategies for Improving Oral Drug Bioavailability. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, J. The Importance of Drug Delivery: An Innovative Approach for Revolutionizing Healthcare. Drug Des. Open Access 2023, 12, 254. [Google Scholar]

- Karahmet Sher, E.; Alebić, M.; Marković Boras, M.; Boškailo, E.; Karahmet Farhat, E.; Karahmet, A.; Pavlović, B.; Sher, F.; Lekić, L. Nanotechnology in Medicine Revolutionizing Drug Delivery for Cancer and Viral Infection Treatments. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 660, 124345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassaee, S.N.; Richard, D.; Ayoko, G.A.; Islam, N. Lipid Polymer Hybrid Nanoparticles against Lung Cancer and Their Application as Inhalable Formulation. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 2113–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Self-Assembled Lipid-Based Nanoparticles for Chemotherapy against Breast Cancer. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1482637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojarad-Jabali, S.; Roh, K.-H. Peptide-Based Inhibitors and Nanoparticles: Emerging Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 669, 125055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.; Fan, X. Insights into the Prospects of Nanobiomaterials in the Treatment of Cardiac Arrhythmia. J. Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhong, Y.; Shen, J.; An, W. Biomimetic Exosomes: A New Generation of Drug Delivery System. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 865682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamimed, S.; Jabberi, M.; Chatti, A. Nanotechnology in Drug and Gene Delivery. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2022, 395, 769–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetisgin, A.A.; Cetinel, S.; Zuvin, M.; Kosar, A.; Kutlu, O. Therapeutic Nanoparticles and Their Targeted Delivery Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Lv, Z.; Yang, Q.; Chang, R.; Wu, J. Research Progress on Stimulus-Responsive Polymer Nanocarriers for Cancer Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Xie, Q.; Sun, Y. Advances in Nanomaterial-Based Targeted Drug Delivery Systems. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1177151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabahar, K.; Alanazi, Z.; Qushawy, M. Targeted Drug Delivery System: Advantages, Carriers and Strategies. Indian J Pharm Educ 2021, 55, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezike, T.C.; Okpala, U.S.; Onoja, U.L.; Nwike, C.P.; Ezeako, E.C.; Okpara, O.J.; Okoroafor, C.C.; Eze, S.C.; Kalu, O.L.; Odoh, E.C.; et al. Advances in Drug Delivery Systems, Challenges and Future Directions. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, S. Nano-Antioxidants: A New Frontier In Antioxidant Delivery Systems. 2025.

- Thatyana, M.; Dube, N.P.; Kemboi, D.; Manicum, A.-L.E.; Mokgalaka-Fleischmann, N.S.; Tembu, J.V. Advances in Phytonanotechnology: A Plant-Mediated Green Synthesis of Metal Nanoparticles Using Phyllanthus Plant Extracts and Their Antimicrobial and Anticancer Applications. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, T. Vitamins and Human Health: Systematic Reviews and Original Research. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagbohun, O.F.; Gillies, C.R.; Murphy, K.P.J.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Role of Antioxidant Vitamins and Other Micronutrients on Regulations of Specific Genes and Signaling Pathways in the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugandhi, V.V.; Pangeni, R.; Vora, L.K.; Poudel, S.; Nangare, S.; Jagwani, S.; Gadhave, D.; Qin, C.; Pandya, A.; Shah, P.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of Vitamin Dosage Forms: A Complete Overview. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 48–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedhiafi, T.; Idoudi, S.; Fernandes, Q.; Al-Zaidan, L.; Uddin, S.; Dermime, S.; Billa, N.; Merhi, M. Nano-Vitamin C: A Promising Candidate for Therapeutic Applications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 158, 114093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crintea, A.; Dutu, A.G.; Sovrea, A.; Constantin, A.-M.; Samasca, G.; Masalar, A.L.; Ifju, B.; Linga, E.; Neamti, L.; Tranca, R.A.; et al. Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery: An Overview with Emphasis on Vitamin D and K Transportation. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi-karkan, S.; Sargazi, S.; Shojaei, S.; Farasati Far, B.; Mirinejad, S.; Cordani, M.; Khosravi, A.; Zarrabi, A.; Ghavami, S. Biotin-Functionalized Nanoparticles: An Overview of Recent Trends in Cancer Detection. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 12750–12792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, C.; Mishra, S.; Chaurasia, S.K.; Pandey, B.K.; Dhar, R.; Pandey, J.K. Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles Using Biometabolites: Mechanisms and Applications. BioMetals 2025, 38, 21–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggeletopoulou, I.; Kalafateli, M.; Geramoutsos, G.; Triantos, C. Recent Advances in the Use of Vitamin D Organic Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Wang, P.-W.; Alalaiwe, A.; Lin, Z.-C.; Fang, J.-Y. Use of Lipid Nanocarriers to Improve Oral Delivery of Vitamins. Nutrients 2019, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabasz, A.; Bzowska, M.; Szczepanowicz, K. Biomedical Applications of Multifunctional Polymeric Nanocarriers: A Review of Current Literature. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 8673–8696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezigue, M. Lipid and Polymeric Nanoparticles: Drug Delivery Applications. In Integrative Nanomedicine for New Therapies; Krishnan, A., Chuturgoon, A., Eds.; Engineering Materials; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 167–230 ISBN 978-3-030-36259-1.

- Altammar, K.A. A Review on Nanoparticles: Characteristics, Synthesis, Applications, and Challenges. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1155622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, D.; Sherkar, R.; Shirsathe, C.; Sonwane, R.; Varpe, N.; Shelke, S.; More, M.P.; Pardeshi, S.R.; Dhaneshwar, G.; Junnuthula, V.; et al. Biofabrication of Nanoparticles: Sources, Synthesis, and Biomedical Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1159193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Taheri-Ledari, R.; Ganjali, F.; Afruzi, F.H.; Hajizadeh, Z.; Saeidirad, M.; Qazi, F.S.; Kashtiaray, A.; Sehat, S.S.; Hamblin, M.R.; et al. Nanoscale Bioconjugates: A Review of the Structural Attributes of Drug-Loaded Nanocarrier Conjugates for Selective Cancer Therapy. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Rashid, A.; Younas, R.; Chong, R. A Chemical Reduction Approach to the Synthesis of Copper Nanoparticles. Int. Nano Lett. 2016, 6, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, F.V.; Lima, I.S.; De Falco, A.; Ereias, B.M.; Baffa, O.; Diego de Abreu Lima, C.; Morais Sinimbu, L.I.; de la Presa, P.; Luz-Lima, C.; Damasceno Felix Araujo, J.F. The Effect of Temperature on the Synthesis of Magnetite Nanoparticles by the Coprecipitation Method. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A. A Review on Synthesis Methods of Materials Science and Nanotechnology. Adv. Mater. Lett. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daruich De Souza, C.; Ribeiro Nogueira, B.; Rostelato, M.E.C.M. Review of the Methodologies Used in the Synthesis Gold Nanoparticles by Chemical Reduction. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 798, 714–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iravani, S.; Korbekandi, H.; Mirmohammadi, S.V.; Zolfaghari, B. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: Chemical, Physical and Biological Methods. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 9, 385–406. [Google Scholar]

- Villaverde-Cantizano, G.; Laurenti, M.; Rubio-Retama, J.; Contreras-Cáceres, R. Reducing Agents in Colloidal Nanoparticle Synthesis—An Introduction. In Reducing Agents in Colloidal Nanoparticle Synthesis; Mourdikoudis, S., Ed.; The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2021; pp. 1–27 ISBN 978-1-83916-165-0.

- Antarnusa, G.; Jayanti, P.D.; Denny, Y.R.; Suherman, A. Utilization of Co-Precipitation Method on Synthesis of Fe3O4/PEG with Different Concentrations of PEG for Biosensor Applications. Materialia 2022, 25, 101525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotresh, M.G.; Patil, M.K.; Inamdar, S.R. Reaction Temperature Based Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles Using Co-Precipitation Method: Detailed Structural and Optical Characterization. Optik 2021, 243, 167506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazid, N.A.; Joon, Y.C. Co-Precipitation Synthesis of Magnetic Nanoparticles for Efficient Removal of Heavy Metal from Synthetic Wastewater.; Penang, Malaysia, 2019; p. 020019.

- Bokov, D.; Turki Jalil, A.; Chupradit, S.; Suksatan, W.; Javed Ansari, M.; Shewael, I.H.; Valiev, G.H.; Kianfar, E. Nanomaterial by Sol-Gel Method: Synthesis and Application. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5102014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danks, A.E.; Hall, S.R.; Schnepp, Z. The Evolution of ‘Sol–Gel’ Chemistry as a Technique for Materials Synthesis. Mater. Horiz. 2016, 3, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr Azadani, R.; Sabbagh, M.; Salehi, H.; Cheshmi, A.; Beena Kumari, A.R.; Erabi, G. Sol-Gel: Uncomplicated, Routine and Affordable Synthesis Procedure for Utilization of Composites in Drug Delivery: Review. J. Compos. Compd. 2021, 2, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqar, M.A.; Mubarak, N.; Khan, A.M.; Khan, R.; Khan, I.N.; Riaz, M.; Ahsan, A.; Munir, M. Sol-Gel for Delivery of Molecules, Its Method of Preparation and Recent Applications in Medicine. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 2024, 63, 1564–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, K.; Takuli, A.; Gupta, T.K.; Gupta, D. Rethinking Nanoparticle Synthesis: A Sustainable Approach vs. Traditional Methods. Chem. Asian J. 2024, 19, e202400701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banjara, R.A.; Kumar, A.; Aneshwari, R.K.; Satnami, M.L.; Sinha, S.K. A Comparative Analysis of Chemical vs Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles and Their Various Applications. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2024, 22, 100988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, M.; Kashif, M.; Muhammad, S.; Azizi, S.; Sun, H. Various Methods of Synthesis and Applications of Gold-Based Nanomaterials: A Detailed Review. Cryst. Growth Des. 2025, 25, 2227–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverberi, A.; Vocciante, M.; Lunghi, E.; Pietrelli, L.; Fabiano, B. New Trends in the Synthesis of Nanoparticles by Green Methods. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017, 61, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gour, A.; Jain, N.K. Advances in Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles. Artif. Cells Nanomedicine Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Desimone, M.F.; Pandya, S.; Jasani, S.; George, N.; Adnan, M.; Aldarhami, A.; Bazaid, A.S.; Alderhami, S.A. Revisiting the Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles: Uncovering Influences of Plant Extracts as Reducing Agents for Enhanced Synthesis Efficiency and Its Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2023, 18, 4727–4750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Mehra, N.K.; Jain, N.K. Development and Characterization of the Paclitaxel Loaded Riboflavin and Thiamine Conjugated Carbon Nanotubes for Cancer Treatment. Pharm. Res. 2016, 33, 1769–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Jana, N.R. Vitamin C-Conjugated Nanoparticle Protects Cells from Oxidative Stress at Low Doses but Induces Oxidative Stress and Cell Death at High Doses. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 41807–41817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kader, D.A.; Rashid, S.O.; Omer, K.M. Green Nanocomposite: Fabrication, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Application of Vitamin C Adduct-Conjugated ZnO Nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 9963–9977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nah, H.; Lee, D.; Heo, M.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, S.J.; Heo, D.N.; Seong, J.; Lim, H.-N.; Lee, Y.-H.; Moon, H.-J.; et al. Vitamin D-Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles as Functional Carriers to Enhancing Osteogenic Differentiation. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2019, 20, 826–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamenraz, S.; Jafarpour, M.; Eskandari, A.; Rezaeifard, A. Vitamin B5 Copper Conjugated Triazine Dendrimer Improved the Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2 Nanoparticles for Aerobic Homocoupling Reactions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, Z.; Ali, S.A.; Shah, M.R.; Ahmed, F.; Ahmed, A.; Ijaz, U.; Afzal, H.; Ahmed, S.; Sheraz, M.A.; Usmani, M. Photochemical Preparation, Characterization and Formation Kinetics of Riboflavin Conjugated Silver Nanoparticles. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1289, 135863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Nagendra, V.; Baig, R.; Varma, R.; Nadagouda, M. Expeditious Synthesis of Noble Metal Nanoparticles Using Vitamin B12 under Microwave Irradiation. Appl. Sci. 2015, 5, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malassis, L.; Dreyfus, R.; Murphy, R.J.; Hough, L.A.; Donnio, B.; Murray, C.B. One-Step Green Synthesis of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles with Ascorbic Acid and Their Versatile Surface Post-Functionalization. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 33092–33100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, S.; Guan, Z.; Ofoegbu, P.C.; Clubb, P.; Rico, C.; He, F.; Hong, J. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles: Current Developments and Limitations. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 26, 102336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewska, K.; Marciniak, L. Influence of the Synthesis Conditions on the Morphology and Thermometric Properties of the Lifetime-Based Luminescent Thermometers in YPO4 :Yb3+,Nd3+ Nanocrystals. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 31466–31473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiopu, A.-G.; Iordache, D.M.; Oproescu, M.; Cursaru, L.M.; Ioța, A.-M. Tailoring the Synthesis Method of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles for Desired Properties. Crystals 2024, 14, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavan, K.; Ashokkumar, T. Plant-Mediated Biosynthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles: A Review of Literature, Factors Affecting Synthesis, Characterization Techniques and Applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 4866–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, I.; Zhou, Y. Impact of pH on the Stability, Dissolution and Aggregation Kinetics of Silver Nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2019, 216, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Tan, P.; Fu, S.; Tian, X.; Zhang, H.; Ma, X.; Gu, Z.; Luo, K. Preparation and Application of pH-Responsive Drug Delivery Systems. J. Controlled Release 2022, 348, 206–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payanda Konuk, O.; Alsuhile, A.A.A.M.; Yousefzadeh, H.; Ulker, Z.; Bozbag, S.E.; García-González, C.A.; Smirnova, I.; Erkey, C. The Effect of Synthesis Conditions and Process Parameters on Aerogel Properties. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1294520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Awadh, A.A.; Shet, A.R.; Patil, L.R.; Shaikh, I.A.; Alshahrani, M.M.; Nadaf, R.; Mahnashi, M.H.; Desai, S.V.; Muddapur, U.M.; Achappa, S. Sustainable Synthesis and Characterization of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Raphanus Sativus Extract and Its Biomedical Applications. Crystals 2022, 12, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.; Mahajan, P.; Mahajan, S.; Khosla, A.; Datt, R.; Gupta, V.; Young, S.-J.; Oruganti, S.K. Review—Influence of Processing Parameters to Control Morphology and Optical Properties of Sol-Gel Synthesized ZnO Nanoparticles. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 023002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.U.; Jalil, K.; Shahid, M.; Rauf, A.; Muhammad, N.; Khan, A.; Shah, M.R.; Khan, M.A. Green Synthesis and Biological Activities of Gold Nanoparticles Functionalized with Salix Alba. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 2914–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, A.; Dawood, A.; Rida; Saira, F.; Malik, A.; Alkholief, M.; Ahmad, H.; Khan, M.A.; Ahmad, Z.; Bazighifan, O. Enhancing Catalytic Activity of Gold Nanoparticles in a Standard Redox Reaction by Investigating the Impact of AuNPs Size, Temperature and Reductant Concentrations. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.J.F.; Sánchez, M.D.; Falcone, R.D.; Ritacco, H.A. Production of Pd Nanoparticles in Microemulsions. Effect of Reaction Rates on the Particle Size. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 1692–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi Dehsari, H.; Halda Ribeiro, A.; Ersöz, B.; Tremel, W.; Jakob, G.; Asadi, K. Effect of Precursor Concentration on Size Evolution of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 6694–6702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, S.; Daneshkhah, A.; Diwate, A.; Patel, H.; Smith, J.; Reul, O.; Cheng, R.; Izadian, A.; Hajrasouliha, A.R. Model for Gold Nanoparticle Synthesis: Effect of pH and Reaction Time. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 16847–16853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P.M.; Felício, M.R.; Santos, N.C.; Gonçalves, S.; Domingues, M.M. Application of Light Scattering Techniques to Nanoparticle Characterization and Development. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joudeh, N.; Linke, D. Nanoparticle Classification, Physicochemical Properties, Characterization, and Applications: A Comprehensive Review for Biologists. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joudeh, N.; Linke, D. Nanoparticle Classification, Physicochemical Properties, Characterization, and Applications: A Comprehensive Review for Biologists. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modena, M.M.; Rühle, B.; Burg, T.P.; Wuttke, S. Nanoparticle Characterization: What to Measure? Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1901556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngumbi, P.K.; Mugo, S.W.; Ngaruiya, J.M. Determination of Gold Nanoparticles Sizes via Surface Plasmon Resonance. IOSR J Appl Chem 2018, 11, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dawadi, S.; Katuwal, S.; Gupta, A.; Lamichhane, U.; Thapa, R.; Jaisi, S.; Lamichhane, G.; Bhattarai, D.P.; Parajuli, N. Current Research on Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications. J. Nanomater. 2021, 2021, 6687290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, N.S.; Alsubhi, N.S.; Felimban, A.I. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Medicinal Plants: Characterization and Application. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2022, 15, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Lotina, A.; Portela, R.; Baeza, P.; Alcolea-Rodríguez, V.; Villarroel, M.; Ávila, P. Zeta Potential as a Tool for Functional Materials Development. Catal. Today 2023, 423, 113862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiufiuc, G.F.; Stiufiuc, R.I. Magnetic Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Their Use in Biomedical Field. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Arnold, W. Nanoscale Ultrasonic Subsurface Imaging with Atomic Force Microscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.-Q.; Hayat, Z.; Zhang, D.-D.; Li, M.-Y.; Hu, S.; Wu, Q.; Cao, Y.-F.; Yuan, Y. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, Modification, and Applications in Food and Agriculture. Processes 2023, 11, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.D.; Prasad, R.S.; Prasad, R.B.; Prasad, S.R.; Singha, S.B.; Singha, D.; Prasad, R.J.; Sinha, P.; Saxena, S.; Vaidya, A.K. A Review on Modern Characterization Techniques for Analysis of Nanomaterials and Biomaterials. ES Energy Environ. 2024, 23, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zain, N.M.; Stapley, A.G.F.; Shama, G. Green Synthesis of Silver and Copper Nanoparticles Using Ascorbic Acid and Chitosan for Antimicrobial Applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 112, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Deeb, N.M.; Khattab, S.M.; Abu-Youssef, M.A.; Badr, A.M.A. Green Synthesis of Novel Stable Biogenic Gold Nanoparticles for Breast Cancer Therapeutics via the Induction of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Pathways. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boopathi, T.S.; Rajiv, A.; Patel, T.S.G.M.; Bareja, L.; Salmen, S.H.; Aljawdah, H.M.; Arulselvan, P.; Suriyaprakash, J.; Thangavelu, I. Efficient One-Pot Green Synthesis of Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Folic Acid Embedded Ultrafine CeO2 Nanocomposite and Its Superior Multi-Drug Resistant Antibacterial Activity and Anticancer Activity. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 48, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Yao, Z.; Su, J.; Wang, Z.; Xia, H.; Liu, S. 2D Copper(II) Metalated Metal–Organic Framework Nanocomplexes for Dual-Enhanced Photodynamic Therapy and Amplified Antitumor Immunity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 44199–44210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.; Siddiqui, S.; Mashraqi, A.; Mandal, R.K.; Wahid, M.; Ahmad, F.; Fatima, B. Green Synthesis and Biomedical Potential of l -Ascorbic Acid-Stabilized Copper Sulfide Nanoparticles as Antibacterial and Antioxidant Agents. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2025, 51, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Li, D.; Chen, L.; Jiang, J.; Gao, L. Vitamin B2 Functionalized Iron Oxide Nanozymes for Mouth Ulcer Healing. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghareghomi, S.; Ahmadian, S.; Zarghami, N.; Hemmati, S. hTERT-Molecular Targeted Therapy of Ovarian Cancer Cells via Folate-Functionalized PLGA Nanoparticles Co-Loaded with MNPs/siRNA/Wortmannin. Life Sci. 2021, 277, 119621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, P.; Wu, Y.; Fan, M.; Chen, X.; Dong, M.; Qiao, W.; Dong, N.; Wang, Q. Folic Acid Modified Silver Nanoparticles Promote Endothelialization and Inhibit Calcification of Decellularized Heart Valves by Immunomodulation with Anti-Bacteria Property. Biomater. Adv. 2025, 166, 214069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safarpour, R.; Pooresmaeil, M.; Namazi, H. Folic Acid Functionalized Ag@MOF(Ag) Decorated Carboxymethyl Starch Nanoparticles as a New Doxorubicin Delivery System with Inherent Antibacterial Activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aashima; Pandey, S.K.; Singh, S.; Mehta, S.K. Biocompatible Gadolinium Oxide Nanoparticles as Efficient Agent against Pathogenic Bacteria. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 529, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas Aiello, M.B.; Ghilini, F.; Martínez Porcel, J.E.; Giovanetti, L.; Schilardi, P.L.; Mártire, D.O. Riboflavin-Mediated Photooxidation of Gold Nanoparticles and Its Effect on the Inactivation of Bacteria. Langmuir 2020, 36, 8272–8281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.-Q.; Qiao, Y.; Lu, X.-Y.; Jiang, S.-P.; Li, W.-S.; Wang, X.-J.; Xu, X.-L.; Qi, J.; Xiao, Y.-H.; Du, Y.-Z. Tocopherol Polyethylene Glycol Succinate-Modified Hollow Silver Nanoparticles for Combating Bacteria-Resistance. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 2520–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandhasamy, K.; Chinnaiyan, S.K.; Balakrishnan, K.; Baskaran, N.; Ali, S. Multifunctional Fucoidan and Folic Acid-Functionalized Yttrium Oxide Nanoparticles: A Novel Approach for Anti-Cancer, Antibacterial, Larvicidal and Environmental Remediation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 318, 144761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bužková, A.; Hochvaldová, L.; Večeřová, R.; Malina, T.; Petr, M.; Kašlík, J.; Kvítek, L.; Kolář, M.; Panáček, A.; Prucek, R. Selenium Nanoparticles: Influence of Reducing Agents on Particle Stability and Antibacterial Activity at Biogenic Concentrations. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 8170–8182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moaness, M.; Mabrouk, M.; Ahmed, M.M.; Das, D.B.; Beherei, H.H. Novel Zinc-Silver Nanocages for Drug Delivery and Wound Healing: Preparation, Characterization and Antimicrobial Activities. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 616, 121559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, L.; Wei, Y.; Wu, Q.; Mao, K.; Wang, X.; Cai, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, Y. Photothermal Iron-Based Riboflavin Microneedles for the Treatment of Bacterial Keratitis via Ion Therapy and Immunomodulation. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 2304448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudose, M.; Culita, D.C.; Ionita, P.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Silver Nanoparticles Embedded into Silica Functionalized with Vitamins as Biological Active Materials. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 4460–4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, S.; Salman, A.; Khan, Z.; Khan, S.; Krishnaraj, C.; Yun, S.-I. Metallic Nanoparticles: A Promising Arsenal against Antimicrobial Resistance—Unraveling Mechanisms and Enhancing Medication Efficacy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamer, A.M.A.; El Maghraby, G.M.; Shafik, M.M.; Al-Madboly, L.A. Silver Nanoparticle with Potential Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Efficiency against Multiple Drug Resistant, Extensive Drug Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Clinical Isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Kumar, G.S.; Roy, H.; Maddiboyina, B.; Leporatti, S.; Bohara, R.A. From Nature to Nanomedicine: Bioengineered Metallic Nanoparticles Bridge the Gap for Medical Applications. Discov. Nano 2024, 19, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.; Nazam, N.; Rizvi, S.M.D.; Ahmad, K.; Baig, M.H.; Lee, E.J.; Choi, I. Mechanistic Insights into the Antimicrobial Actions of Metallic Nanoparticles and Their Implications for Multidrug Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agreles, M.A.A.; Cavalcanti, I.D.L.; Cavalcanti, I.M.F. Synergism between Metallic Nanoparticles and Antibiotics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 3973–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.I.; Dias, A.M.; Zille, A. Synergistic Effects Between Metal Nanoparticles and Commercial Antimicrobial Agents: A Review. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 3030–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-López, E.; Gomes, D.; Esteruelas, G.; Bonilla, L.; Lopez-Machado, A.L.; Galindo, R.; Cano, A.; Espina, M.; Ettcheto, M.; Camins, A.; et al. Metal-Based Nanoparticles as Antimicrobial Agents: An Overview. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lin, D.; Li, M.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chu, H.; Ye, J.; Liu, Y. Bioactive Metallic Nanoparticles for Synergistic Cancer Immunotherapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 1869–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-J.; Zhang, W.-C.; Guo, Y.-W.; Chen, X.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-N. Metal Nanoparticles as a Promising Technology in Targeted Cancer Treatment. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, E.R.; Bugga, P.; Asthana, V.; Drezek, R. Metallic Nanoparticles for Cancer Immunotherapy. Mater. Today 2018, 21, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, T.; Qin, S.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Shi, J.; Nice, E.C.; Xie, N.; Huang, C.; Shen, Z. Enhancing the Therapeutic Efficacy of Nanoparticles for Cancer Treatment Using Versatile Targeted Strategies. J. Hematol. Oncol.J Hematol Oncol 2022, 15, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelechowska-Matysiak, K.; Salvanou, E.-A.; Bouziotis, P.; Budlewski, T.; Bilewicz, A.; Majkowska-Pilip, A. Improvement of the Effectiveness of HER2+ Cancer Therapy by Use of Doxorubicin and Trastuzumab Modified Radioactive Gold Nanoparticles. Mol. Pharm. 2023, 20, 4676–4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beik, J.; Khademi, S.; Attaran, N.; Sarkar, S.; Shakeri-Zadeh, A.; Ghaznavi, H.; Ghadiri, H. A Nanotechnology-Based Strategy to Increase the Efficiency of Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy: Folate-Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Arivarasan, V.K. A Multifunctional Drug Delivery Cargo: Folate-Driven Gold Nanoparticle-Vitamin B Complex for next-Generation Drug Delivery. Mater. Lett. 2024, 355, 135425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Duan, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chu, H. DNA-Functionalized Metal or Metal-Containing Nanoparticles for Biological Applications. Dalton Trans. 2024, 53, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Swierczewska, M.; Lee, S.; Chen, X. Functional Nanoparticles for Molecular Imaging Guided Gene Delivery. Nano Today 2010, 5, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabello, V.; Calatayud, D.G.; Arrowsmith, R.L.; Ge, H.; Pascu, S.I. Metallic Nanoparticles as Synthetic Building Blocks for Cancer Diagnostics: From Materials Design to Molecular Imaging Applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 5657–5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnwal, A.; Kumar Sachan, R.S.; Devgon, I.; Devgon, J.; Pant, G.; Panchpuri, M.; Ahmad, A.; Alshammari, M.B.; Hossain, K.; Kumar, G. Gold Nanoparticles in Nanobiotechnology: From Synthesis to Biosensing Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 29966–29982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi-karkan, S.; Sargazi, S.; Shojaei, S.; Farasati Far, B.; Mirinejad, S.; Cordani, M.; Khosravi, A.; Zarrabi, A.; Ghavami, S. Biotin-Functionalized Nanoparticles: An Overview of Recent Trends in Cancer Detection. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 12750–12792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamimed, S.; Jabberi, M.; Chatti, A. Nanotechnology in Drug and Gene Delivery. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2022, 395, 769–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Veroniaina, H.; Su, N.; Sha, K.; Jiang, F.; Wu, Z.; Qi, X. Applications and Developments of Gene Therapy Drug Delivery Systems for Genetic Diseases. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 16, 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.; Kim, S. Recent Advances in the Development of Gene Delivery Systems. Biomater. Res. 2019, 23, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Veroniaina, H.; Su, N.; Sha, K.; Jiang, F.; Wu, Z.; Qi, X. Applications and Developments of Gene Therapy Drug Delivery Systems for Genetic Diseases. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 16, 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Pan, C.; Yong, H.; Wang, F.; Bo, T.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, B.; He, W.; Li, M. Emerging Non-Viral Vectors for Gene Delivery. J. Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R.L. Mechanism of Action and Target Identification: A Matter of Timing in Drug Discovery. iScience 2020, 23, 101487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.L.-H.; Chiang, S.; Kalinowski, D.S.; Bae, D.-H.; Sahni, S.; Richardson, D.R. The Role of the Antioxidant Response in Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Degenerative Diseases: Cross-talk between Antioxidant Defense, Autophagy, and Apoptosis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 6392763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaallah, R.; Amine, A. The Kinetic and Analytical Aspects of Enzyme Competitive Inhibition: Sensing of Tyrosinase Inhibitors. Biosensors 2021, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.D.; Huang, B.-W.; Tsuji, Y. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Homeostasis and Redox Regulation in Cellular Signaling. Cell. Signal. 2012, 24, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Saxena, J.; Srivastava, V.K.; Kaushik, S.; Singh, H.; Abo-EL-Sooud, K.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Jyoti, A.; Saluja, R. The Interplay of Oxidative Stress and ROS Scavenging: Antioxidants as a Therapeutic Potential in Sepsis. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusti, A.M.T.; Qusti, S.Y.; Alshammari, E.M.; Toraih, E.A.; Fawzy, M.S. Antioxidants-Related Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), Catalase (CAT), Glutathione Peroxidase (GPX), Glutathione-S-Transferase (GST), and Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS) Gene Variants Analysis in an Obese Population: A Preliminary Case-Control Study. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gal, K.; Schmidt, E.E.; Sayin, V.I. Cellular Redox Homeostasis. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ming, H.; Qin, S.; Nice, E.C.; Dong, J.; Du, Z.; Huang, C. Redox Regulation: Mechanisms, Biology and Therapeutic Targets in Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, F.R.M.; Araujo, T.L.S.; Abrahão, T.B. Nox NADPH Oxidases and the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 2755–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Kong, A. Molecular Mechanisms of Nrf2-mediated Antioxidant Response. Mol. Carcinog. 2009, 48, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliwell, B. Understanding Mechanisms of Antioxidant Action in Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modi, S.K.; Gaur, S.; Sengupta, M.; Singh, M.S. Mechanistic Insights into Nanoparticle Surface-Bacterial Membrane Interactions in Overcoming Antibiotic Resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1135579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Variyathody, H.; Arthanari, M.; Murugan, M.; Kuppannan, G. Evaluating the Antibacterial Profile of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles—Vitamin E (CuO NPs-Vit E) Complex against Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia Coli and Staphylococcus Aureus. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 17, 2080–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, P.R.; Pandit, S.; Filippis, A.D.; Franci, G.; Mijakovic, I.; Galdiero, M. Silver Nanoparticles: Bactericidal and Mechanistic Approach against Drug Resistant Pathogens. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, R.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Qin, Y. Potential Antibacterial Mechanism of Silver Nanoparticles and the Optimization of Orthopedic Implants by Advanced Modification Technologies. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 3311–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, S.S.N.; Gunasekara, T.; Holton, J. Antimicrobial Nanoparticles: Applications and Mechanisms of Action. 2018.

- Aunins, T.R.; Erickson, K.E.; Chatterjee, A. Transcriptome-Based Design of Antisense Inhibitors Potentiates Carbapenem Efficacy in CRE Escherichia Coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 30699–30709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afrasiabi, S.; Partoazar, A. Targeting Bacterial Biofilm-Related Genes with Nanoparticle-Based Strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1387114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, P.R.; Pandit, S.; Filippis, A.D.; Franci, G.; Mijakovic, I.; Galdiero, M. Silver Nanoparticles: Bactericidal and Mechanistic Approach against Drug Resistant Pathogens. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hu, C.; Shao, L. The Antimicrobial Activity of Nanoparticles: Present Situation and Prospects for the Future. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2017, 1227–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imad Abd-AlAziz, S.; Thalij, K.M.; Zakari, M.G. Inhibitory Susceptibility of Synthetic Selenium Nanoparticles and Some Conjugate Nutritional Compounds in Inhibition of Some Bacterial Isolates Causing Food Poisoning. Tikrit J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 23, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, R.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Qin, Y. Potential Antibacterial Mechanism of Silver Nanoparticles and the Optimization of Orthopedic Implants by Advanced Modification Technologies. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 3311–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, D.; Charlton-Sevcik, A.K.; Braswell, W.E.; Sayes, C.M. Evaluating the Antibacterial Potential of Distinct Size Populations of Stabilized Zinc Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairnar, S.V.; Das, A.; Oupický, D.; Sadykov, M.; Romanova, S. Strategies to Overcome Antibiotic Resistance: Silver Nanoparticles and Vancomycin in Pathogen Eradication. RSC Pharm. 2025, 2, 455–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M.M.; Sorinolu, A.J.; Munir, M.; Vejerano, E.P. Nanoantibiotics: Functions and Properties at the Nanoscale to Combat Antibiotic Resistance. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 687660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutt, Y.; Dhiman, R.; Singh, T.; Vibhuti, A.; Gupta, A.; Pandey, R.P.; Raj, V.S.; Chang, C.-M.; Priyadarshini, A. The Association between Biofilm Formation and Antimicrobial Resistance with Possible Ingenious Bio-Remedial Approaches. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saffari Natanzi, A.; Poudineh, M.; Karimi, E.; Khaledi, A.; Haddad Kashani, H. Innovative Approaches to Combat Antibiotic Resistance: Integrating CRISPR/Cas9 and Nanoparticles against Biofilm-Driven Infections. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezeh, C.K.; Dibua, M.E.U. Anti-Biofilm, Drug Delivery and Cytotoxicity Properties of Dendrimers. ADMET DMPK 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar, C.; Jiménez, A.; Silva, A.; Kaur, N.; Thangarasu, P.; Ramos, J.; Singh, N. Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Nanoparticles for Bacterial Inhibition: Synthesis and Characterization of Doped and Undoped ONPs with Ag/Au NPs. Molecules 2015, 20, 6002–6021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrasiabi, S.; Partoazar, A. Targeting Bacterial Biofilm-Related Genes with Nanoparticle-Based Strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1387114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhole, R.P.; Jadhav, S.; Zambare, Y.B.; Chikhale, R.V.; Bonde, C.G. Vitamin-Anticancer Drug Conjugates: A New Era for Cancer Therapy. Istanb. J. Pharm. 2020, 50, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palvai, S.; Nagraj, J.; Mapara, N.; Chowdhury, R.; Basu, S. Dual Drug Loaded Vitamin D3 Nanoparticle to Target Drug Resistance in Cancer. RSC Adv 2014, 4, 57271–57281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Gawali, S.; Patil, S.; Basu, S. Synthesis, Characterization and in Vitro Evaluation of Novel Vitamin D3 Nanoparticles as a Versatile Platform for Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, G.; Rieger, S.; Hewison, M.; Capobianco, E.; Lisse, T.S. The Impact of Vitamin D on Cancer: A Mini Review. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 231, 106308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liu, H.; Ye, Y.; Lei, Y.; Islam, R.; Tan, S.; Tong, R.; Miao, Y.-B.; Cai, L. Smart Nanoparticles for Cancer Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palvai, S.; Nagraj, J.; Mapara, N.; Chowdhury, R.; Basu, S. Dual Drug Loaded Vitamin D3 Nanoparticle to Target Drug Resistance in Cancer. RSC Adv 2014, 4, 57271–57281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Gawali, S.; Patil, S.; Basu, S. Synthesis, Characterization and in Vitro Evaluation of Novel Vitamin D3 Nanoparticles as a Versatile Platform for Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Shim, M.K.; Moon, Y.; Kim, J.; Cho, H.; Yun, W.S.; Shim, N.; Seong, J.-K.; Lee, Y.; Lim, D.-K.; et al. Cancer Cell-Specific and pro-Apoptotic SMAC Peptide-Doxorubicin Conjugated Prodrug Encapsulated Aposomes for Synergistic Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Lei, Y.; Ning, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, G.; Wang, C.; Wan, Q.; Guo, S.; Liu, Q.; Xie, R.; et al. PGF2α Facilitates Pathological Retinal Angiogenesis by Modulating Endothelial FOS -driven ELR+ CXC Chemokine Expression. EMBO Mol. Med. 2023, 15, e16373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, L.; Pareek, V.; Dilip, R.V.; Bhargava, A.; Pasha, S.S.; Laskar, I.R.; Saini, H.; Dash, S.; Chowdhury, R.; Panwar, J. Biosynthesized Protein-Capped Silver Nanoparticles Induce ROS-Dependent Proapoptotic Signals and Prosurvival Autophagy in Cancer Cells. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 1489–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Hu, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X.; Huang, X.; Tian, B.; Zhao, C.-X.; Du, Y.; Wu, L. Programmed Enhancement of Endogenous Iron-Mediated Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization for Tumor Ferroptosis/Pyroptosis Dual-Induction. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.-Y.; Wu, C.; He, X.-Y.; Zhuo, R.-X.; Cheng, S.-X. Multi-Drug Loaded Vitamin E-TPGS Nanoparticles for Synergistic Drug Delivery to Overcome Drug Resistance in Tumor Treatment. Sci. Bull. 2016, 61, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Thapa, R.K.; Yong, C.S.; Kim, J.O. Nanoparticle-Based Combination Drug Delivery Systems for Synergistic Cancer Treatment. J. Pharm. Investig. 2016, 46, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kydd, J.; Jadia, R.; Velpurisiva, P.; Gad, A.; Paliwal, S.; Rai, P. Targeting Strategies for the Combination Treatment of Cancer Using Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.; Tang, L.; Romero, G. Nanoparticles-Mediated Combination Therapies for Cancer Treatment. Adv. Ther. 2019, 2, 1900076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, R.; Jin, T.; Hu, K.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; et al. Vitamin D Promotes the Cisplatin Sensitivity of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Inhibiting LCN2-Modulated NF-κB Pathway Activation through RPS3. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, L.; Lei, J. Multifunctional Metal–Organic Framework Heterostructures for Enhanced Cancer Therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 1188–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, A.; Gül, D.; Wandrey, M.; Lu, Q.; Knauer, S.K.; Reinhardt, C.; Strieth, S.; Hagemann, J.; Stauber, R.H. The Vitamin D Receptor–BIM Axis Overcomes Cisplatin Resistance in Head and Neck Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khursheed, R.; Dua, K.; Vishwas, S.; Gulati, M.; Jha, N.K.; Aldhafeeri, G.M.; Alanazi, F.G.; Goh, B.H.; Gupta, G.; Paudel, K.R.; et al. Biomedical Applications of Metallic Nanoparticles in Cancer: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 150, 112951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, T.T.; Mondal, S.; Doan, V.H.M.; Tak, S.; Choi, J.; Oh, H.; Nguyen, T.D.; Misra, M.; Lee, B.; Oh, J. Precision-Engineered Metal and Metal-Oxide Nanoparticles for Biomedical Imaging and Healthcare Applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 332, 103263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miah, M.S.; Chy, M.W.R.; Ahmed, T.; Suchi, M.; Muhtady, M.A.; Ahmad, S.N.U.; Hossain, M.A. Emerging Trends in Nanotechnologies for Vitamin Delivery: Innovation and Future Prospects. Nano Trends 2025, 10, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Yadagiri, G.; Javaid, A.; Sharma, K.K.; Verma, A.; Singh, O.P.; Sundar, S.; Mudavath, S.L. Hijacking the Intrinsic Vitamin B12 Pathway for the Oral Delivery of Nanoparticles, Resulting in Enhanced in Vivo Anti-Leishmanial Activity. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 10, 5669–5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Li, D.; Li, T.Y.; Wu, Y.-L.; Piao, J.S.; Piao, M.G. Vitamin A—Modified Betulin Polymer Micelles with Hepatic Targeting Capability for Hepatic Fibrosis Protection. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 174, 106189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiensathaporn, S.; Solé-Porta, A.; Baowan, D.; Pissuwan, D.; Wongtrakoongate, P.; Roig, A.; Katewongsa, K.P. Nanoencapsulation of Vitamin B2 Using Chitosan-modified Poly(Lactic- Co -glycolic Acid) Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and in Vitro Studies on Simulated Gastrointestinal Stability and Delivery. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e17631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotake-Nara, E.; Komba, S.; Hase, M. Uptake of Vitamins D2, D3, D4, D5, D6, and D7 Solubilized in Mixed Micelles by Human Intestinal Cells, Caco-2, an Enhancing Effect of Lysophosphatidylcholine on the Cellular Uptake, and Estimation of Vitamins D’ Biological Activities. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albukhaty, S.; Sulaiman, G.M.; Al-Karagoly, H.; Mohammed, H.A.; Hassan, A.S.; Alshammari, A.A.A.; Ahmad, A.M.; Madhi, R.; Almalki, F.A.; Khashan, K.S.; et al. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: The Versatility of the Magnetic and Functionalized Nanomaterials in Targeting Drugs, and Gene Deliveries with Effectual Magnetofection. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 99, 105838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, S.; Liu, S.; Ji, J.; Zhai, G. Transdermal Delivery System Based on Heparin-Modified Graphene Oxide for Deep Transportation, Tumor Microenvironment Regulation, and Immune Activation. Nano Today 2022, 46, 101565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Liu, T.; Wang, K. Chitosan Nanoparticles for Oral Photothermally Enhanced Photodynamic Therapy of Colon Cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 589, 119763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Lee, D.Y. Near-Infrared-Responsive Cancer Photothermal and Photodynamic Therapy Using Gold Nanoparticles. Polymers 2018, 10, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.-Y.; Liu, Z.-H.; Weng, W.-H.; Chang, C.-W. Magnetic Nanocomplexes for Gene Delivery Applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 4267–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidaleo, M.; Tacconi, S.; Sbarigia, C.; Passeri, D.; Rossi, M.; Tata, A.M.; Dini, L. Current Nanocarrier Strategies Improve Vitamin B12 Pharmacokinetics, Ameliorate Patients’ Lives, and Reduce Costs. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuldyushev, N.A.; Simonenko, S.Y.; Goreninskii, S.I.; Pallaeva, T.N.; Zamyatnin, A.A.; Parodi, A. From Nutrient to Nanocarrier: The Multifaceted Role of Vitamin B12 in Drug Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, T.; Qin, S.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Shi, J.; Nice, E.C.; Xie, N.; Huang, C.; Shen, Z. Enhancing the Therapeutic Efficacy of Nanoparticles for Cancer Treatment Using Versatile Targeted Strategies. J. Hematol. Oncol.J Hematol Oncol 2022, 15, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Huang, L.; Han, G. Dye Doped Metal-Organic Frameworks for Enhanced Phototherapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 189, 114479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, T.; Zhu, H.; Han, T.; Wang, J.; Dai, H. Roles of pH, Cation Valence, and Ionic Strength in the Stability and Aggregation Behavior of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 267, 110656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monopoli, M.P.; Åberg, C.; Salvati, A.; Dawson, K.A. Biomolecular Coronas Provide the Biological Identity of Nanosized Materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, C.P.; Abdul-Wahab, M.F.; Jaafar, J.; Chan, G.F.; Rashid, N.A.A. Effect of pH and Biological Media on Polyvinylpyrrolidone-Capped Silver Nanoparticles.; Penang, Malaysia, 2016; p. 080002.

- Misra, S.K.; Rosenholm, J.M.; Pathak, K. Functionalized and Nonfunctionalized Nanosystems for Mitochondrial Drug Delivery with Metallic Nanoparticles. Molecules 2023, 28, 4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; Riviere, J.E. Pharmacokinetics of Metallic Nanoparticles. WIREs Nanomedicine Nanobiotechnology 2015, 7, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolova, M.P.; Joshi, P.B.; Chavali, M.S. Updates on Biogenic Metallic and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: Therapy, Drug Delivery and Cytotoxicity. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Han, F.; Lin, W. Targeted Drug Delivery Systems for Kidney Diseases. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 683247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakic, K.; Selc, M.; Razga, F.; Nemethova, V.; Mazancova, P.; Havel, F.; Sramek, M.; Zarska, M.; Proska, J.; Masanova, V.; et al. Long-Term Accumulation, Biological Effects and Toxicity of BSA-Coated Gold Nanoparticles in the Mouse Liver, Spleen, and Kidneys. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 4103–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, K.; Coen, D.; Nafo, W. Polymer-Based Nanoparticles for Cancer Theranostics: Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Explor. BioMat-X 2025, 2, 101342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, L.; Kushwaha, P.; Ansari, T.M.; Kumar, A.; Rao, A. Recent Trends in Biologically Synthesized Metal Nanoparticles and Their Biomedical Applications: A Review. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2024, 202, 3383–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geigert, J. The Challenge of CMC Regulatory Compliance for Biopharmaceuticals; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-31908-2.

- Foulkes, R.; Man, E.; Thind, J.; Yeung, S.; Joy, A.; Hoskins, C. The Regulation of Nanomaterials and Nanomedicines for Clinical Application: Current and Future Perspectives. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 4653–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skotland, T.; Iversen, T.-G.; Sandvig, K. Development of Nanoparticles for Clinical Use. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 1295–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrakala, V.; Aruna, V.; Angajala, G. Review on Metal Nanoparticles as Nanocarriers: Current Challenges and Perspectives in Drug Delivery Systems. Emergent Mater. 2022, 5, 1593–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Guo, X.; Ramlawi, N.; Pfeiffer, T.V.; Geutjens, R.; Basak, S.; Nirschl, H.; Biskos, G.; Zandbergen, H.W.; Schmidt-Ott, A. Green Manufacturing of Metallic Nanoparticles: A Facile and Universal Approach to Scaling Up. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 11222–11227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, S.J.; Sheng, J.; Hosseinian, F.; Willmore, W.G. Nanoparticle Effects on Stress Response Pathways and Nanoparticle–Protein Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, T.A.; Kevadiya, B.D.; Bajwa, N.; Singh, P.A.; Zheng, H.; Kirabo, A.; Li, Y.-L.; Patel, K.P. Role of Nanoparticle-Conjugates and Nanotheranostics in Abrogating Oxidative Stress and Ameliorating Neuroinflammation. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicea, D.; Nicolae-Maranciuc, A. Metal Nanocomposites as Biosensors for Biological Fluids Analysis. Materials 2025, 18, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeaka, H.; Passaretti, P.; Miri, T.; Al-Sharify, Z.T. The Safety of Nanomaterials in Food Production and Packaging. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawne, P.J.; Ferreira, M.; Papaluca, M.; Grimm, J.; Decuzzi, P. New Opportunities and Old Challenges in the Clinical Translation of Nanotheranostics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2023, 8, 783–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M.S.; Chy, M.W.R.; Ahmed, T.; Suchi, M.; Muhtady, M.A.; Ahmad, S.N.U.; Hossain, M.A. Emerging Trends in Nanotechnologies for Vitamin Delivery: Innovation and Future Prospects. Nano Trends 2025, 10, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C. Editorial: Nanomedicine Development and Clinical Translation. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1458690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).