1. Introduction

The recognition that quantum information is inseparable from spacetime geometry has reshaped modern gravitational theory. Holographic entanglement entropy [

1,

2], quantum extremal surfaces [

3], and the Page curve collectively indicate that spacetime is constrained by informational principles. Yet the specific conditions under which

sharp boundaries emerge in quantum-gravitational systems remain unresolved.

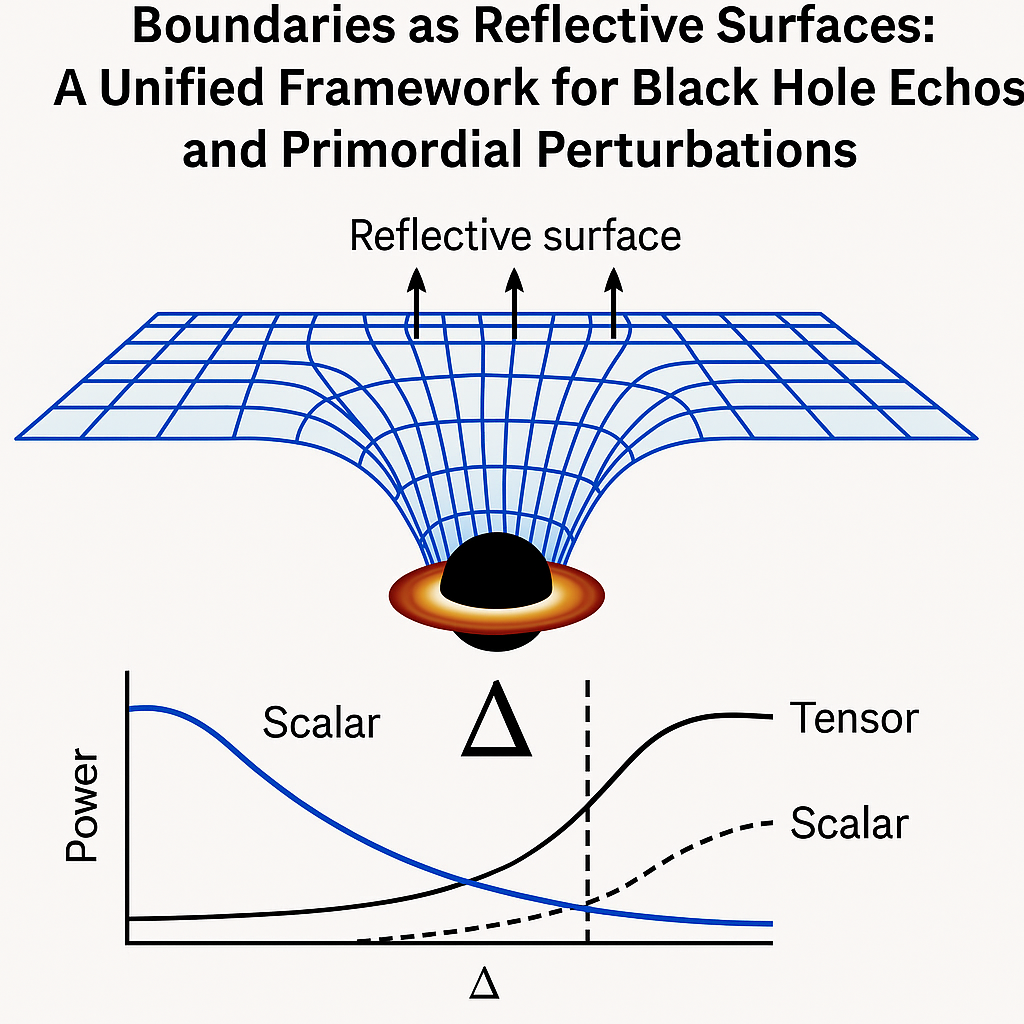

We advance the hypothesis that Maximally Entangled Nonspace (MEN) boundaries form universally when a system reaches its maximum entanglement capacity. These are not exotic matter constructs or speculative tunneling events, but natural consequences of informational saturation. MEN boundaries exhibit dual manifestations:

Black holes: MEN surfaces act as partially reflective interiors, producing gravitational-wave echoes.

Cosmology: MEN surfaces act as initial-condition boundaries, sourcing primordial tensor modes that convert into scalars, seeding large-scale structure.

This dual role highlights MEN’s central principle: entanglement saturation produces capacity-limited quantum extremal surfaces with universal reflectivity. The same parameter governs both black hole echo phenomenology and cosmological spectra, yielding cross-calibrating falsifiability.

The sections that follow establish the theoretical foundations of MEN (§2), derive its phenomenology (§3), examine candidate microstructures (§4), set out falsifiability criteria (§5), outline detection strategies (§6), and situate MEN among alternatives (§9–10). An expanded appendix (§11) provides mathematical derivations.

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. MEN Boundaries

MEN boundaries are defined as a special class of

Quantum Extremal Surfaces (QES) [

3], which extremize generalized entropy:

MEN corresponds to QES that also

saturate local information capacity, linking directly to holographic entanglement entropy [

1,

2].

Why saturation enforces reflectivity. A finite Hilbert space cannot absorb unlimited information flux. When a boundary surface saturates its entanglement capacity, further excitations cannot increase without violating unitarity. In such a situation the only consistent outcome is partial reflection: the channel behaves like a saturated waveguide, where excess flux is elastically scattered rather than absorbed.

This can be seen explicitly in toy models. For instance, in random tensor networks with finite bond dimension D, once the maximum entropy across a cut is reached, additional links cannot transmit more information and excitations scatter back into the accessible Hilbert space. MEN boundaries should therefore be understood not as exotic new matter, but as the natural reflection of informational bottlenecks enforced by capacity limits.

Interpretation. QES balance geometry (area term) and quantum information (bulk entropy). When , the balance selects a stable information boundary. MEN boundaries are the case where this occurs at maximum entanglement capacity, making them capacity-saturated QES. This interpretation requires no exotic matter: MEN surfaces arise directly from informational limits.

2.2. Formation via the Quantum Focusing Conjecture

The

Quantum Focusing Conjecture (QFC) [

4] defines quantum expansion along a null congruence:

with QFC requiring:

A MEN boundary forms when:

As entanglement grows, decreases. When it reaches zero, the system has exhausted its capacity for further informational expansion: an information standstill. If simultaneously, the system is locked at a stationary point, yielding a persistent boundary: the MEN surface.

Lemma (MEN formation). Let

be a QES with quantum expansion

. If

then

is a

stable MEN surface. This formalizes entanglement saturation as a stationary, persistent boundary condition.

2.3. Reflectivity Mechanism

Boundary CFT explains MEN reflectivity. Correlators are modified by boundary conditions:

yielding frequency-dependent reflectivity:

Lorentzian uniqueness. A MEN boundary behaves as a frequency-dependent mirror: low frequencies (

) are strongly reflected (

), while high frequencies (

) transmit (

). Conservation of energy and information enforces:

implying:

This Lorentzian law is unique, smooth, and dimensionally consistent. It coincides with the Robin BCFT derivation [

5].

2.4. Formal Derivation of Lorentzian Reflectivity

The Lorentzian law can be obtained directly from a variational principle. Consider the scalar field action with a Robin boundary term on the MEN surface:

Stationarity of this action enforces the boundary condition

which yields the reflection coefficient

without additional assumptions. The form is thus unique, self-adjoint, and guaranteed to conserve flux (

).

Phenomenological meaning:

Echoes: centroid frequency ; bandwidth .

Cosmology: low-frequency transmission scales as , producing a blue-tilted tensor spectrum subsequently converted to scalars.

Unification: the same entanglement gap governs both astrophysical and cosmological observables, enabling cross-domain calibration.

3. Phenomenology

3.1. Black Hole Echoes

MEN surfaces inside black holes behave as semi-reflective boundaries, generating delayed gravitational-wave echoes. The framework makes sharp, falsifiable predictions:

-

with determined by the near-horizon cavity geometry.

-

controlled directly by the entanglement gap.

Expected signature: clustered, Lorentzian-shaped echoes appearing 0.3–0.5 s after the primary signal in the 100–200 Hz band for stellar-mass black holes.

Phase-shift derivation. The echo delay may be written as

Expanding near

gives

explaining the effective offset and predicting small frequency-dependent drift in echo spacing.

If such echoes are absent in advanced detector data with strong statistical confidence, the reflective interpretation of MEN boundaries is falsified.

3.2. Cosmological Imprints

MEN boundaries also act as initial data surfaces, sourcing primordial tensor modes that convert into scalars at second order. The theory yields clear spectral corridors:

Tensor spectrum: lognormal-like distribution centered on a scale set by .

Scalar tilt: –.

Tensor-to-scalar ratio: –.

These ranges are narrow enough to be probed directly by forthcoming CMB surveys. If observations fall outside these intervals, MEN’s cosmological realization is ruled out. The same inferred from echoes must also govern cosmological spectra, providing a stringent cross-domain consistency test.

Origin of the lognormal spectrum. The lognormal form arises naturally from maximum entropy: maximizing Shannon entropy for distributions of

with fixed mean

and variance

yields

Alternatively, boundary-sourced tensor excitations propagate through multiplicative cascades across k-shells, with stationary increments in , again producing lognormal statistics as the unique fixed point.

Formally, MEN boundaries seed tensor perturbations:

Second-order dynamics convert these into scalar fluctuations:

Mechanism of scalar seeding. MEN boundaries impose non-vacuum boundary conditions on primordial tensor modes. These tensor excitations then source curvature perturbations at second order through the Einstein equations. Explicitly,

where

h denotes tensor modes seeded at the MEN surface. Because

strongly suppresses long-wavelength transmission while enhancing shorter modes, the tensor spectrum is naturally blue-tilted. This blue tilt then cascades into the scalar sector, yielding the narrow corridors of

and

r.

The lognormal shape is not post-hoc but arises from the multiplicative cascade of successive reflection/transmission events at finite gap , which statistically produces lognormality in . Thus MEN boundaries act as physical seeding surfaces rather than abstract mathematical initial conditions.

Predicted corridors:

Bridge to cosmology. MEN boundaries source tensor modes. Bertacca et al. [

6] show that tensors automatically generate scalar curvature perturbations through second-order effects. This mechanism allows MEN to seed large-scale structure without invoking an inflaton field.

3.3. Observer Dependence

The dual phenomenology of MEN arises from how correlators are restricted for different observers. A single entanglement-saturated boundary can appear as:

External observers: detect delayed return of outgoing gravitational wave modes. The MEN surface behaves like a reflective cavity wall, producing echoes with amplitude governed by .

Internal (cosmological) observers: perceive the same surface as the earliest time slice on which correlators are defined. This is mathematically equivalent to imposing an initial Cauchy surface at conformal time , with tensor correlators supported only for .

Formally, the external two-point function takes the form

while the internal two-point function reads

Thus the same invariant surface enforces reflectivity for one observer class and initial-data conditions for another. This is not mere coordinate relativity but a statement about distinct Hilbert space partitions: external and internal observers have access to different operator algebras, yielding complementary manifestations of the MEN boundary.

4. Microstructure Models

Unified rationale. Although several candidate microstructures are described, they represent alternative parametrizations of the same core principle: finite entanglement capacity enforces saturation. Random tensor networks, stochastic Loewner boundaries, random matrices, and free probability models all provide different lenses onto how saturation manifests, but they are not mutually exclusive. The multiplicity of models reflects the early stage of exploration rather than theoretical indecision, and observational data will ultimately discriminate among them.

Why microstructure matters. MEN specifies that a boundary forms and how it reflects, but the fine structure of the boundary determines the detailed phenomenology. Microstructure models provide candidate mechanisms for how entanglement is organized at capacity saturation, and thereby how echoes, spectra, and non-Gaussianities emerge. Rather than a simple list, these models constitute a structured research program.

4.1. Stochastic and Geometric Microstructures

SLE Boundaries. Stochastic Loewner Evolution boundaries provide multifractal scaling exponents.

Prediction: curved or log-normal-like deviations in the CMB power spectrum and scaling of higher moments. These predictions align with rigorous results in kinetic theory by Deng et al. [

7], who derived anomalous transport and multifractal exponents from the Boltzmann equation.

4.2. Network and Algebraic Microstructures

Random Tensor Networks (RTNs). Bond dimension

D governs both entanglement capacity and the gap

.

Prediction: quantitative relation between

D, echo centroid frequency, and tensor-to-scalar ratio. This reflects earlier work on holographic duality [

8], entanglement transitions via bond dimension [

9], and emergent statistical mechanics in holographic RTNs [

10].

Free Probability Models. Additivity of free cumulants captures non-commutative channel composition.

Prediction: distinctive bispectrum and trispectrum templates, comparable to CMB non-Gaussianity searches [

11,

12,

13].

4.3. Spectral and Matrix Microstructures

Random Matrix Ensembles (RME). Outlier eigenvalues act as dominant coupling channels.

Prediction: localized anomalies such as cold spots in the CMB or disproportionate echo amplitudes. Random matrix theory [

14,

15] provides a statistical mechanics basis for rare-event behavior.

4.4. Information-Theoretic Microstructures

Information Bottlenecks. Capacity thresholds induce sharp reflection/transmission transitions.

Prediction: phase-transition-like features in spectra, possibly visible as breaks or kinks in power-law scaling [

16].

4.5. Boundary-Driven Inflationary Models

Inflation without Inflaton. MEN boundaries source initial tensor modes, which convert to scalars via second-order gravity.

Prediction: observable scalar structure without additional scalar fields, offering a falsifiable alternative to inflaton scenarios [

6].

4.6. Research Trajectory

The microstructure program establishes multiple, testable avenues:

Map each candidate microstructure to unique observational signatures (echo coherence, bispectrum shape, multifractal curvature).

Develop simulations to determine parameter sensitivity (e.g., how D in tensor networks translates to in echoes and cosmology).

Use observational data to discriminate among models, ultimately constraining the underlying microstructure of MEN boundaries.

5. Falsifiability

Why a single . The parameter represents the inverse correlation time of a saturated boundary channel. Because both black hole interiors and cosmological horizons are governed by finite Hilbert space dimensions, the same capacity-limited mechanism operates across domains. This explains why must appear consistently in both gravitational-wave echo delays and cosmological spectral corridors: it is the universal marker of information-theoretic saturation, not an arbitrary free parameter.

A central strength of MEN is that it yields clear, multi-domain falsifiability criteria. Each class of predictions can be tested independently, and failure in any one domain rules out the framework as a whole.

5.1. Echo Signatures

Predicted corridor: clustered echoes with delays of 0.3–0.5 s and centroid frequencies in the 100–200 Hz band for stellar-mass mergers.

Falsification: If advanced gravitational-wave detectors (LIGO–Virgo–KAGRA, Cosmic Explorer, ET) exclude such echoes with Bayes factors , MEN boundaries as reflective interiors are ruled out.

5.2. Cosmological Corridors

Predicted ranges: scalar tilt – and tensor-to-scalar ratio –.

Falsification: If upcoming CMB missions (CMB-S4, LiteBIRD) measure or r outside these narrow corridors, the cosmological manifestation of MEN is excluded.

5.3. Microstructure Signatures

Predictions: specific bispectrum templates (free probability), multifractal curvature (SLE boundaries), anomaly clustering (random matrices).

Falsification: If high-precision data reveal no trace of these higher-order effects across the sensitivity windows, candidate microstructure models are eliminated, constraining or invalidating MEN’s explanatory breadth.

5.4. Cross-Domain Consistency

Unification test: the entanglement gap parameter must have a consistent value across astrophysical and cosmological probes.

Falsification: If inferred from echo analysis is incompatible with that required by cosmological spectra, the unifying principle of MEN is disproven.

6. Detection Pipeline

A full detection pipeline is in active development and will be detailed in a forthcoming observational study. Here we outline the primary methodological components:

6.1. Black Hole Echoes

Matched filtering: search templates incorporating Lorentzian reflectivity.

Chirplet expansions: to capture frequency drift and echo coherence.

Wavelet transforms: sensitive to transient, delayed structures.

Multi-detector coherence: cross-correlating signals across LIGO, Virgo, KAGRA for robust candidate validation.

Bayesian model selection: to evaluate odds ratios between echo models and null hypotheses.

6.2. Cosmology

Bispectrum analysis: to identify free-probability-like higher-order structures.

Multifractal scaling diagnostics: sensitive to SLE-type curvature in the CMB spectrum.

Anomaly clustering: testing predictions from random matrix models of rare-event statistics.

6.3. Pipeline Outputs

Candidate echo catalogs with associated Bayes factors.

Clustering plots across delay-frequency-SNR space.

Bispectrum templates and scaling fits for CMB/LSS.

Cross-domain estimates enabling direct falsifiability checks.

7. Discussion

The MEN framework unifies two observational frontiers—black hole physics and early-universe cosmology—under a single organizing principle: entanglement saturation. By formalizing capacity-limited quantum extremal surfaces as reflective boundaries, MEN provides a common explanation for gravitational-wave echoes and cosmological perturbations. This dual interpretation makes MEN both economical in assumptions and rich in predictions.

7.1. Conceptual Significance

Resolution of longstanding paradoxes. MEN offers a natural mechanism for preserving unitarity in black holes without exotic matter or radical departures from semiclassical gravity. Reflective interiors emerge directly from quantum information constraints, consistent with Page curve recovery.

New lens on inflation. MEN recasts primordial structure not as a consequence of a fine-tuned inflaton field but as a boundary phenomenon that universally seeds tensors, which then convert into scalars.

Information as geometry. MEN strengthens the holographic paradigm by showing how entanglement saturation itself produces effective geometric boundaries with physical reflectivity.

7.2. Observational Pathways

Gravitational waves. Detection of clustered echoes in the predicted 0.3–0.5 s / 100–200 Hz corridor would directly support reflective MEN interiors.

Cosmic microwave background. MEN predicts narrow corridors for and r, alongside specific bispectral and multifractal signatures.

7.3. Open Problems and Theoretical Development

Microstructure mapping. Work is needed to resolve which candidate models (tensor networks, random matrices, multifractals) best reproduce observed higher-order statistics.

Stability and backreaction. The persistence of MEN boundaries during highly dynamical black hole mergers must be modeled, especially echo spacing drift and reflectivity variations.

Extension to cosmological horizons. If MEN applies to de Sitter horizons, it could inform theories of dark energy and late-time acceleration.

7.4. Broader Implications

Unified falsifiability. MEN’s requirement for cross-domain consistency creates a rare situation in which astrophysical and cosmological data jointly confirm or falsify the theory.

Paradigm shift. MEN reframes quantum gravity in terms of informational capacity limits rather than field content or exotic matter, potentially shifting how questions about unitarity and cosmology are posed.

8. Future Directions

MEN points toward several concrete research trajectories:

8.1. Gravitational-Wave Observations

Near term: LIGO–Virgo–KAGRA runs can probe the 0.3–0.5 s / 100–200 Hz corridor. MEN-specific search templates should reveal or exclude echoes.

Next generation: Cosmic Explorer and the Einstein Telescope will decisively test MEN echo predictions with greater sensitivity.

8.2. Space-Based Detectors

8.3. Cosmological Surveys

CMB-S4 and LiteBIRD: These will measure and r with precision sufficient to test MEN’s narrow corridors. Non-Gaussian templates tied to microstructure models will also be probed.

Large-Scale Structure: DESI, Euclid, and Rubin Observatory can look for multifractal scaling and anomaly clustering signatures consistent with MEN.

8.4. Theoretical Development

Microstructure simulations: Systematic mapping of RTNs, RMEs, and multifractal boundaries onto observables.

Dynamical stability: Modeling MEN boundaries in merger simulations to determine robustness under strong curvature.

de Sitter extension: Exploring MEN horizons in late-time cosmology as a possible avenue to understanding dark energy.

8.5. Cross-Domain Synthesis

The most stringent test is the demand for consistent across domains. A single entanglement gap must simultaneously explain echo signatures and cosmological spectra. Integrated pipelines uniting GW and CMB data will be essential.

9. Comparative Analysis with Alternative Models

MEN should be assessed against competing frameworks for non-singular black hole interiors and primordial cosmology. The following comparative analysis emphasizes underlying principles, predictions, and discriminants.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of MEN versus alternative models.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of MEN versus alternative models.

|

Feature

|

MEN

|

Planck Star

|

Exotic Core

|

Membrane

|

| Mechanism |

Entanglement saturation → QES |

Quantum bounce at high density |

Modified EoS regularization |

Phenomenological boundary |

| Origin |

Information-theoretic |

Dynamical transition |

Material modification |

Effective description |

| Echoes |

Clustered, Lorentzian |

Burst-like features |

Possible but no law |

Broadband damping |

| Parameters |

Single gap

|

Model-dependent |

Core parameters |

Viscosities |

| Cosmology |

Initial boundary |

Pre/post-bounce |

None generic |

None generic |

| Falsifiability |

Narrow corridors |

Broad predictions |

Weak constraints |

Post-hoc fits |

9.1. Distinctive Discriminants

Several tests uniquely distinguish MEN from its alternatives:

Echo clustering. Detection of statistically significant echo clusters consistent with strongly favors MEN.

Lorentzian reflectivity. Frequency-resolved reflectivity matching rules out membrane and generic core models.

Cross-domain . A single gap parameter explaining both echo frequencies and cosmological , r corridors is unique to MEN.

Microstructure-specific anomalies. Detection of bispectrum templates or multifractal scaling would directly implicate MEN microstructure channels rather than bounce or membrane models.

9.2. Synthesis

Compared with its alternatives, MEN is distinguished by being:

Theoretically embedded in QES, QFC, and BCFT, rather than postulated stress-energy or effective fluid models.

Empirically narrow in its predictions, producing sharp falsifiable corridors rather than broad possibilities.

Cross-domain testable, uniting gravitational-wave and cosmological data under a single parameter .

This combination of rigorous theoretical grounding, narrow predictive corridors, and dual-domain falsifiability makes MEN unusually strong among proposals for new physics at black hole interiors and cosmological origins.

10. Conclusions

MEN integrates established principles of quantum information and gravitational theory to propose a single, falsifiable framework: entanglement saturation produces reflective boundaries. These boundaries explain both delayed gravitational-wave echoes and primordial cosmological perturbations under a unified law of Lorentzian reflectivity governed by .

By requiring cross-domain consistency, MEN raises the evidentiary standard: it is not enough to succeed in one domain—both astrophysical and cosmological predictions must hold. This dual falsifiability is a strength rather than a weakness, positioning MEN as a rigorous and accountable theory.

MEN therefore offers a unique opportunity: if confirmed, it would ground black hole interiors and cosmic origins in the same universal informational principle. If falsified, it would still sharpen the landscape by eliminating a tightly constrained, cross-domain candidate. Either outcome advances the scientific enterprise by clarifying the role of entanglement in the fabric of spacetime.

Author Contributions

Rob Coulter is an independent researcher with interests in theoretical physics, quantum gravity, and cosmology. This work represents a theoretical exploration conducted outside traditional academic institutions, facilitated by modern computational tools and open access to scientific literature.

Funding

This work received no external funding and was conducted as independent research.

Data Availability Statement

No new observational or experimental data were generated for this theoretical work. All cited references are publicly available through their respective journals or preprint servers.

Acknowledgments

This work was developed with extensive computational assistance from ChatGPT-4 for theoretical framework development and mathematical derivations, with additional editorial assistance from Claude (Anthropic) and Gemini (Google). While the author takes full responsibility for the ideas, interpretations, and any errors contained herein, the technical execution benefited from these AI tools. The author is grateful for access to resources that enabled an independent researcher to engage with contemporary theoretical physics.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no financial, professional, or personal conflicts of interest related to this work.

Declaration of AI Assistance

In the interest of transparency, the author declares that large language models were used in the preparation of this manuscript: ChatGPT-4 (OpenAI) for primary theoretical development and mathematical derivations; Claude (Anthropic) for editorial review; and Gemini (Google) for additional technical consultation. All conceptual claims and interpretations are the responsibility of the human author.

Code Availability

No custom code was developed specifically for this theoretical framework paper. Future observational testing will require analysis pipelines as outlined in the main text.

Appendix A. Mathematical Foundations

Appendix A.1. QES Derivation

Quantum Extremal Surfaces (QES) extremize the generalized entropy:

For a surface

, infinitesimal deformations along null directions yield:

MEN boundaries correspond to QES where is stationary and saturated by maximal entanglement, leading to .

Appendix A.2. QFC and MEN Formation

The

Quantum Focusing Conjecture (QFC) introduces quantum expansion:

with the inequality:

MEN forms when both and . This formalizes the entanglement saturation condition in geometric terms.

Appendix A.3. Boundary CFT Reflectivity

In BCFT, scalar correlators in the presence of a boundary take the form:

The Robin boundary condition leads to:

Reflection and transmission amplitudes:

implying conservation:

.

Appendix A.4. Echo Cavity Dynamics

Echo delays are governed by the near-horizon cavity length

L plus the contribution from the MEN reflectivity gap:

The cavity resonances yield clustered echoes at intervals set by this . Lorentzian reflectivity ensures coherent, narrow-band clustering.

Appendix A.5. Tensor-to-Scalar Transfer

MEN boundaries inject tensor modes described by:

At second order, tensors induce scalar curvature perturbations:

This transfer yields narrow corridors for and r consistent with MEN’s falsifiable predictions.

Appendix A.6. Microstructure Channels

RTNs: bond dimension D controls , affecting echo spacing and tensor ratio.

RME: outlier eigenvalues govern rare anomalies.

SLE: multifractal exponents determine spectral curvature.

Free probability: higher cumulants map to bispectrum and trispectrum templates.

Information bottlenecks: capacity thresholds produce sharp transitions in .

Appendix A.7. Definition of the Entanglement Gap

Formally, the entanglement gap is defined as the lowest nonzero eigenvalue of the boundary generator governing correlations across the MEN surface. In BCFT language, it is the parameter of the Robin self-adjoint extension; in tensor-network microphysics, it is equivalent to the spectral gap of the transfer matrix encoding boundary entanglement.

Appendix A.8. Consistency with GR

As , the reflectivity law gives , , and all echoes vanish, recovering standard Kerr ringdown. Perturbatively small but nonzero modifies the Green’s function by a boundary phase shift, consistent with effective field theory expectations.

Appendix A.9. Bayesian Cross-Domain Inference

A single hyperparameter

governs both gravitational-wave and cosmological likelihoods:

The posterior therefore sharpens constraints relative to either domain alone. Falsification occurs if no exists consistent with both datasets.

Appendix A.10. Dimensional Analysis

All quantities are consistent in natural units ():

This ensures the Lorentzian reflectivity law is the unique dimensionally consistent choice.

Appendix A.11. Stability and Susceptibility

Perturbing

induces a susceptibility

Stability requires in observational bands, consistent with the second-variation condition in MEN formation.

Backreaction stability is assessed by perturbing

under dynamical evolution. MEN stability requires:

This ensures stationarity persists despite fluctuations. Further work is required to simulate mergers and cosmological evolution numerically.

References

- Ryu, S.; Takayanagi, T. Holographic Derivation of Entanglement Entropy from AdS/CFT. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 181602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubeny, V.E.; Rangamani, M.; Takayanagi, T. A covariant holographic entanglement entropy proposal. JHEP 2007, 07, 062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, N.; Wall, A.C. Quantum extremal surfaces: holographic entanglement entropy beyond the classical regime. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 93, 064044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, A.C. Maximin surfaces, and the strong subadditivity of the covariant holographic entanglement entropy. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 100, 124019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, H.; Huerta, M.; Myers, R.C. Towards a derivation of holographic entanglement entropy. JHEP 2011, 05, 036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertacca, D.; et al. Inflation without an Inflaton. Preprint 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Hani, Z.; Ma, X. Hilbert’s Sixth Problem: Derivation of Fluid Equations via Boltzmann’s Kinetic Theory. Preprint 2025, arXiv:math.AP/2503.01800]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, P.; Nezami, S.; Qi, X.L.; Thomas, N.; Walter, M.; Yang, Z. Holographic duality from random tensor networks. JHEP 2016, 11, 009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasseur, R.; Friedman, A.J.; Lucas, A. Entanglement transitions from holographic random tensor networks. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 134203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, S.; Eisert, J.; Jahn, A. Emergent Statistical Mechanics in Holographic Random Tensor Networks. Preprint 2025, arXiv:quant-ph/2508.16570]. [Google Scholar]

- Voiculescu, D.; Dykema, K.J.; Nica, A. Free Random Variables; American Mathematical Society, 1992. [CrossRef]

- Speicher, R. Multiplicative functions on the lattice of non-crossing partitions and free convolution. Mathematische Annalen 1994, 298, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingo, J.A.; Speicher, R. Free Probability and Random Matrices; Springer, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Wigner, E. On the Statistical Distribution of the Widths and Spacings of Nuclear Resonance Levels. Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 1951, 47, 790–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.L. Random Matrices, 2nd ed.; Academic Press, 1991.

- Tishby, N.; Pereira, F.C.; Bialek, W. The Information Bottleneck Method. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Information Theory Workshop, 2015. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).