1. Introduction

P-type ATPases move substances -- especially

cations and lipids -- across membranes through the hydrolysis of ATP and the

transient phosphorylation of a highly conserved aspartate (D) residue [1]. Despite their crucial importance in cellular

physiology, relatively little research has been done on the potential of P-type

ATPases as drug targets against the malaria parasite. Among the potential

twelve P-type ATPases that have been identified in the Plasmodium falciparum

genome [2] , most research has been done on the

SERCA orthologue and potential drugs that target this enzyme have been

identified [3,4]. The ability to generate

accurate 3-dimensional models of proteins using known structures as templates,

often called homology modeling, will certainly expedite the identification and

characterization of potential drug targets [5].

This may be especially true of P-type ATPases since their 3-dimensional

structures are relatively well characterized. Homology modeling is a powerful

and essential tool in pathogen research and drug discovery that will provide

insight into protein structure, function, and interactions.

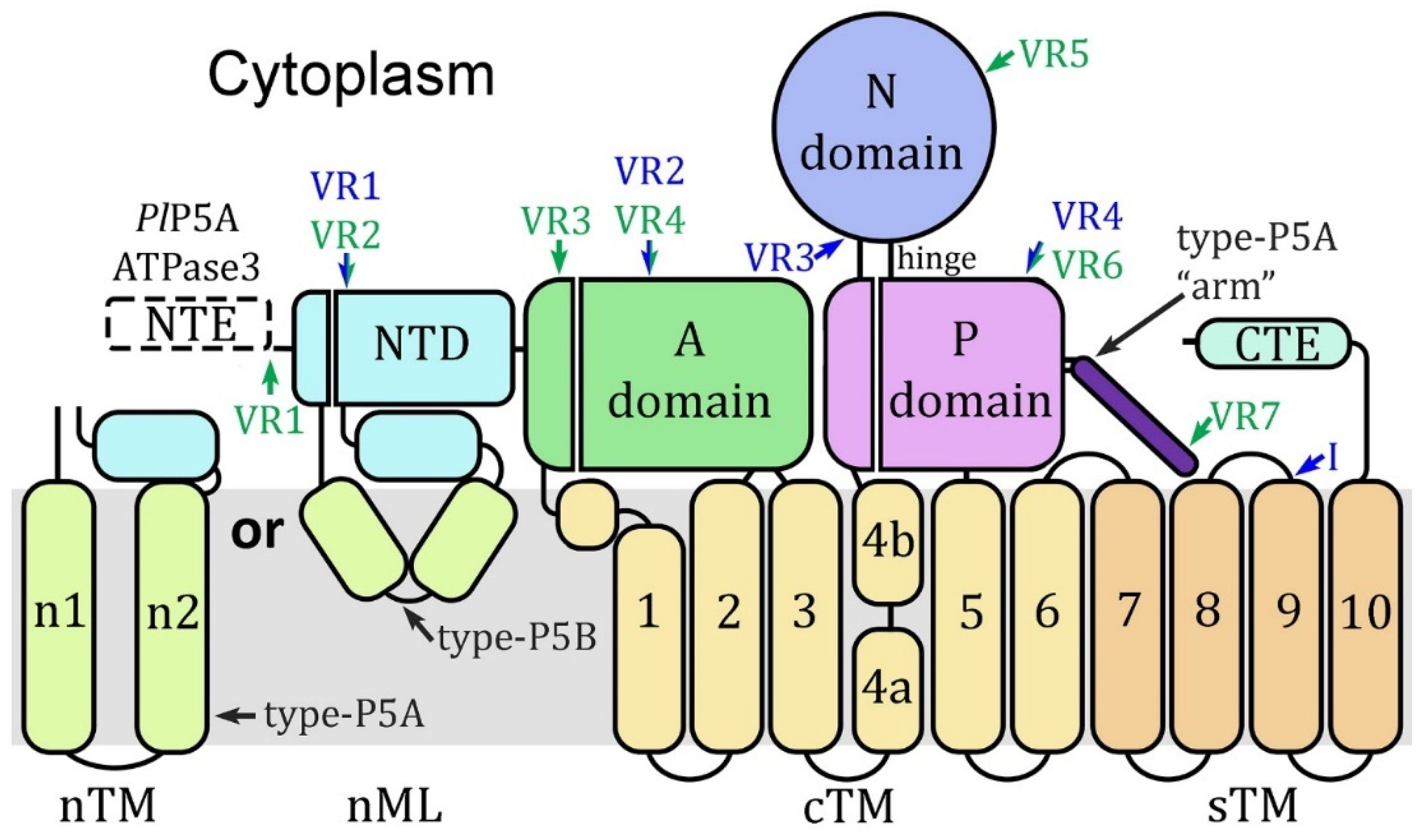

1.1. P-Type ATPases

P-type ATPases comprise a large and ubiquitous gene

family that is defined by canonical structural features. The first and foremost

is the highly conserved phosphorylation motif DKTGT which defines P-type

ATPases. During substrate transport the aspartate (D) is transiently

phosphorylated via ATP hydrolysis and the resulting protein conformation

changes associated with the phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycles facilitate

movement of substances across membranes. All P-type ATPases are comprised of

four highly conserved domains called the actuator (A) domain, the

phosphorylation (P) domain, the nucleotide-binding (N) domain, and membrane (M)

domain [6]. The A-domain has phosphatase

activity to remove the phosphate. The N-domain binds ATP so that the γ -phosphate is adjacent to the phosphorylated

aspartate residue of the DKTGT motif in the P-domain. These three domains are

located on the cytoplasmic face of the membrane. The M-domain is formed by six

core transmembrane helices (cTM) and a variable number of supporting

transmembrane helices (sTM). A substrate-binding groove that opens to the

extracytoplasmic (i.e., extracellular or luminal) side of the membrane is

formed by the cTM. There is a highly conserved proline in the fourth

transmembrane helix (cTM4) that forms a ‘kink’ which forms the base of the

substrate binding groove.

There are five major types (numbered 1-5) of P-type

ATPases based on sequence homology, additional structural domains, and

substrate specificity [1,7]. Subtypes have

also been defined and are designated with capital letters. Type-P5 ATPases, the

least characterized among the P-type ATPases, are defined through sequence

homology and structural features. For example, the signature motif is an

expanded FDKTGTLT, there is an N-terminal domain (NTD), and the M-domain

contains four sTM helices (

Figure 1). The

two subtypes (A and B) of type-P5 ATPases are quite similar and differ

primarily in the NTD, the P-domain, and substrate specificity [1,8]. For example, the NTD of subtype-P5A has two

N-terminal transmembrane helices (nTM), whereas subtype-P5B has a triangular

N-terminal membrane loop (nML). Another distinguishing feature is a helical

projection from the P-domain called the ‘arm’ in subtype-P5A that is not found

in subtype-P5B. And subtype-P5A ATPase has been described as a transmembrane

helix dislocase of the ER [9] and subtype-P5B

ATPase has been described as a polyamine transporter of the lysosome [10,11].

1.2. Type-P5 ATPases of Plasmodium

Type-P5 ATPases are only found in eukaryotes and

most eukaryotes have a single copy of the subtype-P5A and multiple paralogues

of the subtype-P5B, especially in multicellular organisms [8,12]. A single gene for a P5A-subtype has been

identified in Plasmodium [12]. The

protein has not been characterized other than its presence in genomic databases

and the P. falciparum gene is described as a putative

cation-transporting P-type ATPase that is located on chromosome seven [2]. Two subtype-P5B genes designated as ATPase1 and

ATPase3 have been identified in P. falciparum. ATPase1 arose from a

duplication of ATPase3 early in the evolution of the malaria parasite and is

only found in P. falciparum and related parasites of the great apes

(i.e., Laverania), avian malaria parasites, and Haemoproteus [13]. Orthologues of ATPase3 can be positively

identified throughout the Apicomplexa, but no clear orthologues outside of the

Apicomplexa could be identified. ATPase1 and ATPase3 from all the apicomplexan

species exhibited a high level of sequence homology except for four rather

large variable regions composed of low-complexity sequence. Both ATPase1 and

ATPase3 genes also have a single intron located in the same position. The only

quasi-substantial difference between these two paralogues is an extended N-terminus

of variable sequence in ATPase3.

Homology

modeling with Phyre® was carried out in the previous study

[13]

to search

for structural homologues. Numerous P-type ATPases were identified as potential

templates and templates from type-P5 ATPases tended to produce robust

structural models with the expected canonical structural features. However, in

some of the structural models, conserved sequences were sometimes excluded and

replaced with sequences from variable regions to form the secondary elements of

the ATPase domains. This suggests that the variable regions may interfere with

the ability of the templates to generate accurate and robust models. If true,

this may be an important limitation in the analysis of Plasmodium proteins

which often contain large regions of low complexity sequence

[14,15]

.

In addition, detailed analyses of the

polyamine-binding site in the modeled structures of ATPase1 and ATPase3 were

carried out. The predicted structures using a P5B-subtype as the template are

quite similar to the experimentally determined polyamine-binding site and most

of the key amino acids are conserved, especially in ATPase1. The differences

between ATPase1 and ATPase3 opens the possibility of different substrate

specificities. However, as discussed in detail [13]

neither ATPase1 nor ATPase3 are likely to be polyamine transporters and neither

ATPase1 nor ATPase3 appear to be located in the lysosome, which is called the

digestive vacuole in the malaria parasite [16].

Immunofluorescence studies using antibodies against ATPase1 or ATPase3 reveal a

diffuse vesicle-like cytoplasmic staining [17–19]. As previously discussed [20] , this immunofluorescence pattern is consistent

with the known ultrastructure of the ER in malaria parasites [21,22]. The possible ER-localization of ATPase1 and

ATPase3 indicates that these Plasmodium subtype-P5B ATPases may have a

different function than the subtype-P5B ATPases of fungi or metazoans.

To address these potential limitations with

3-dimensional modeling and to gain insight into the structure and function of

type-P5 ATPases from the malaria parasite, Spf1, a rather well-characterized

subtype-P5A ATPase [9] , and ATP13A2, a rather

well-characterized subtype-P5B ATPase [11] ,

were used as templates to investigate sequence and structural homologies of Plasmodium

subtype-P5A ATPase (PlP5A), ATPase1, and ATPase3 from P.

falciparum and P. relictum. These two templates were particularly

robust in the previous study at predicting structures that recapitulated the

experimentally determined structures [13]. The

two species not only serve as replicate analyses but also may provide insight

into the effects of the variable regions since the P. relictum proteins

tend to have smaller variable regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of Subtype-P5A ATPases from Haemosporidians and the SAR Supergroup

The

P. falciparum subtype-P5A ATPase (Gene

ID: PF3D7_0727800) was used as a query in BLASTP searches [23] of non-redundant protein sequences at NCBI and

PlasmoDB [24]. Alignments associated with the

BLAST results were used to eliminate partial sequences and sequences with

obvious errors. Subsequently, the newly identified sequences were used as

queries in BLAST searches to ensure that no subtype-P5A sequences were missed.

In cases where complete sequences were available from multiple strains of a

single species, the reference strain for that species was chosen. For the

haemosporidians a chromosome number was recorded when available. A partial

genome sequence of

Haemoproteus tartakovskyi which is not part of the

non-redundant database is available [25]. A

TBLASTN search of those contigs was performed using the subtype-P5A ATPase from

P. relictum as a query. A complete gene sequence was identified on a

single contig (HtScaffold0006) and corrected by the insertion of a single A

residue. A summary of all the sequences is found in

Table S1.

A conserved-domain (CD) analysis was also carried

out [26] and the e-values associated with the

subtype-P5A (accession number cd07543) and subtype-P5B (accession number

TIGR01657) ATPases were recorded.

2.2. Sequence Alignments

The haemosporidian subtype-P5A sequences were

aligned with ClustalW within Mega XI [27].

Alignments were adjusted manually to accommodate variable regions and core

regions of P-type ATPases. The adjusted alignments were used to generate

phylogenetic trees (

Figure S1).

Subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B ATPases from

P.

falciparum and

P. relictum were subjected to a detailed analysis of

their sequences and predicted 3-dimensional structures, which were compared to

Spf1 and ATP13A2 (

Table 1). Spf1 was used

as a prototype of subtype-P5A ATPases and ATP13A2 was used as a prototype of

subtype-P5B ATPases. The

P. falciparum subtype-P5A ATPase was originally

described in a survey of transporter genes with Gene ID PF07_0115 [28] , which was later changed to PF3D7_0727800. This

sequence was also used in the phylogenetic analysis of type-P5 ATPases [12]. The

P. relictum orthologue of

subtype-P5A was identified in PlasmoDB [24].

ATPase3 is a subtype-P5B ATPase found in apicomplexans and ATPase1 arose from a

gene duplication early in the evolution of the malaria parasite and is only

found in some malaria species [13].

The initial alignment of these eight ATPases was

carried out using ClustalW within Mega 11 [27].

This alignment was adjusted manually using 3-dimensional structures generated

by Swiss Model [29] as a guide to determine

the boundaries between the various domains. The transmembrane helices of the

M-domain were determined from the membrane annotation of Swiss Model

predictions. The first residue after the β -sheet

in the NTD was used as the boundary between the NTD and the A-domain. The first

residue of β -strand-1 and the last

residue of β -strand-6 of the modified

Rossmann fold were used as the boundaries between the P-domain and N-domain.

Furthermore, aligning the β -strand-2

from the subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B ATPases greatly improved the alignment.

Boxshade (

https://junli.netlify.app/apps/boxshade/) was used to denote

identical (shaded in black) or similar (shaded in gray) residues.

Pairwise distances of the conserved regions of the

ATPases were also determined in Mega 11 after removing the variable regions of

low-complexity sequence from the alignment as previously recommended [7,30].

2.3. Homology Modeling

Homology modeling of the eight type-P5 sequences

was carried out with Swiss Model® [29]

using two templates each from Spf1 (PDB ID 6xmq and 6xmu) and ATP13A2 (PDB ID

7m5v and 7m5x). Templates 6xmq and 7m5v were bound with a non-hydrolysable ATP

analog (AMP-PCP) and templates 6xmu and 7m5x were bound with BeF3 and

their respective substrates of a transmembrane helix or spermine. These

templates were previously identified as reliable templates in Phyre®

analyses using the ATPase1 and ATPase3 sequences to search structural databases

[13]. Homology modeling was also carried out

on the Plasmodium ATPases after removal of the large regions of low

complexity and variable sequence.

Images were generated with PyMOL 3.1.3

(Schrodinger, LLC). The various domains were demarcated in different colors,

and the color names refer to the names given by PyMOL. Color scheme: nMH

(limon), cTM (yelloworange), sTM (light orange), NTD (aquamarine), A-domain

(tv_green), N-domain (skyblue), P-domain (violetpurple), cTM4 kink and

signature motif (magenta), phosphorylated asp (yellow), P-domain arm

(purpleblue), and IDL (deepsalmon).

Four criteria were used to assess the quality of

the models: the Global Model Quality Estimation (GMQE), the QMEANDisCo, the

percentage of Ramachandran favorable and Θ angles, and the retention of ligands. GMQE

predicts the expected accuracy of a protein model. QMEANDisCo is a composite

scoring function that provides both global and local quality estimates for a

protein model. Non-covalently bound ligands are retained in models if there are

at least three coordinating residues in the protein and those residues are

conserved in the target–template alignment, and if the resulting atomic

interactions in the model are within the expected range for van der Waals interactions

and water-mediated contacts.

3. Results

3.1. Subtype-P5A ATPase of Haemosporida

The P. falciparum subtype-P5A ATPase (PfP5A)

was originally described in a survey of transporter genes as a presumptive

cation transporter [28] and subsequently

included in a phylogenetic analysis of type-P5 ATPases [12]. Searches of PlasmoDB and NCBI identified

orthologues of subtype-P5A ATPase from other haemosporidians (Table S1). All the haemosporidian genes have a

single exon and their chromosomal locations correspond to the known gene

synteny of Plasmodium [31]. A search of

conserved domains [26] identified cd07543

(subtype-P5A) and TIGR01657 (subtype-P5B) as the two highest scoring domains

based on E-values. In both cases the E-values were extremely low and as

expected the cd07543 tended to be lower than TIGR01657. This confirms that the

sequences are subtype-P5A ATPases but also indicates that subtype-P5A and

subtype-P5B are very similar.

Alignment of the haemosporidian subtype-P5A

orthologues revealed regions of very high sequence homology interspersed with

variable regions of low sequence homology (

Figure S1a). These haemosporidian subtype-P5A ATPases exhibit a similar

phylogeny as reported for ATPase3 [13] and

separate into eight clades (

Figure S1b-c)

that are consistent with the current views on the phylogeny of malaria

parasites [32,33]. The eight clades are

Haemoproteus,

avian parasites,

Laverania, rodent parasites,

Hepatocystis,

malariae, ovale, and vivax-like. As previously observed with ATPase3 [13] ,

Haemoproteus, avian parasites, and

Laverania

form a clade and the other mammalian parasites including

Hepatocystis

form a second clade (

Figure S1b).

The

Plasmodium subtype-P5A ATPases (

PlP5A)

have N-terminal extensions (NTE) not found in either Spf1 or ATP13A2. ATPase3

also has an NTE but ATPase1 does not [13]. The

NTE of

PlP5A is longer than the NTE of ATPase3 and there is no shared

sequence homology (

Figure S2). In the

case of ATPase3, there is substantial sequence homology of the NTE within the

major apicomplexan clades (i.e., haemosporidians, piroplasmids, and

coccidians), whereas there is little homology between these clades [13]. The first half of the NTE of subtype-P5A

exhibits a high degree of sequence homology across all haemosporidians and the

second half of the NTE exhibits little sequence homology (

Figure S1). This creates an insertion of a

variable region between the NTE and the NTD designated as variable region 1

(VR1). Six additional variable regions (VR2-VR7) are found in the

haemosporidian orthologues of subtype-P5A ATPase. These inserts tend to be low

complexity sequence with a high preponderance of asparagine and lysine residues

and tandem repeats are sometimes observed (

Figure S1a).

3.2. Sequence Homology between Subtype-P5A and Subtype-P5B ATPases of Malaria Parasites

ATPase1, ATPase3, and

PlP5A from

Plasmodium

falciparum and

P. relictum were aligned with Spf1 (subtype-P5A) and

ATP13A2 (subtype-P5B). The alignment exhibited regions of high sequence

homology between all eight proteins that were interspersed with regions of

little sequence homology (

Figure S2). The

region including the NTD and the N-terminal membrane loops (nML) exhibit a

moderate level of homology. The regions of highest sequence homology correspond

to the canonical domains of P-type ATPases (A, N, P, and M). Other than the

P-domain (discussed below), there were no substantial regions in which the

sequence homology clearly segregated into either subtype-P5A or subtype-P5B.

This is consistent with the paucity of specific signature sequences to

distinguish subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B [8,12].

Large stretches of low complexity sequence are

inserted between or within the highly conserved canonical domains of the

Plasmodium

type-P5 ATPases. This was previously described in ATPase1 and ATPase3 as

four large variable regions inserted into the NTD, A-domain, N-domain, and

P-domain referred to as variable regions (VR) 1-4 respectively [13]. The positions of these variable regions are

the same in ATPase1 and ATPase3. Subtype-P5A ATPase of

Plasmodium has

seven substantial inserts of low complexity sequence that exhibit sequence

variation (

Figure S1a). The locations of

some of the inserts are exclusive for either subtype-P5A or subtype-P5B,

whereas three inserts have a shared location between the two subtypes (

Table 2). Inserts with shared locations the

inserts tend to be substantially larger in one of the two subtypes. In general,

the inserts of the subtype-P5A ATPases tend to be smaller in size than the

subtype-P5B ATPases. The total percentage of the ATPases that are associated

with variable regions is approximately the same between subtype-P5A and

subtype-P5B. If present, the insert sizes within Spf1 and ATP13A2 are

substantially smaller.

An alignment with the low homology inserts removed

was used to generate a pairwise distance matrix of the eight type-P5 ATPases (

Table 3). Comparisons of ATPases of the same

subtype were designated as concordant and comparisons between subtype-P5A and

subtype-P5B ATPases were designated as discordant. The distance between Spf1

(subtype P5A) and ATP12A2 (subtype P5B) is 1.39 and represents the divergence

subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B from early in the evolution of eukaryotes. The

distances between other discordant sequences exhibit similar values

(1.36-1.59). The concordant subtype-P5B sequences also exhibit similar values

(1.24-1.56), whereas the values from concordant subtype-P5A sequences were a

little lower (1.14-1.16). Even though ATPase1 and ATPase3 are subtype-P5B

ATPases, they are also essentially equal distance from subtype-P5A (1.41-1.59)

and subtype-P5B (1.24-1.56) templates. As expected, the

P. falciparum

and

P. relictum orthologues are the most closely related (0.13-0.42) and

reflect a substantially more recent divergence which is on the order of 10

million years ago [34].

3.3. Homology Modeling and Structure Comparisons

The experimentally determined structures of Spf1

and ATP13A2 were used as templates to carry out homology modeling of the Plasmodium

type-P5 ATPases. As controls, the Spf1 and ATP13A2 sequences were modeled with

the same template (i.e., concordant) or the other template (i.e., discordant).

Modeling with either the concordant or discordant templates produced structures

that were similar to each other and to the experimentally determined

structures. This is especially true for the predicted structures of the M-, A-,

N-, and P-domains. Neither template provided much insight into the structures

of the N-terminal and C-terminal extensions since these sequences were usually

excluded from the models.

As expected, differences between subtype-P5A and

subtype-P5B were primarily in the NTD, including the N-terminal membrane loops,

and the arm in the P-domain. Concordant templates produced more complete

structures than discordant templates. For example, modeling Spf1 with the Spf1

template generated two N-terminal transmembrane helices as is found in

subtype-P5A (

Figure 2), and the

discordant template generated a single N-terminal transmembrane helix (

Figure 3). Similarly, modeling ATP13A2 with the

concordant template generated the expected triangular membrane loop that is

found in subtype-P5B ATPases (

Figure 3)

and triangular loop generated by the discordant template was somewhat

incomplete (

Figure 2). Another feature

specific to subtype-P5A ATPases is a α -helical

‘arm’ that projects from the P-domain. The arm is evident in the experimentally

determined structure and a shorter version is predicted in the concordant model

while no arm is generated with the discordant template.

In general, the predicted structures of the

Plasmodium ATPases are similar to the templates and the major domains of P-type ATPases are readily discernable. However, neither template did an extremely good job at generating the NTD including the associated membrane loops. No NTD was generated with the Spf1 template in four of the

Plasmodium ATPases, and the first transmembrane helix was lacking in the other two ATPases (

Figure 2). Similarly, the NTD was lacking in five of the

Plasmodium ATPase models generated with the ATP13A2 template (

Figure 3). However, in PrATPase1 a complete triangular membrane loop was generated.

3.4. Quality Assessment of Modeling

The quality of the structural models produced from concordant and discordant templates was assessed with two templates representing different conformational states of both Spf1 and ATP13A2 by four criteria as described in the Methods (

Table 4). Models of Spf1 or ATP13A2 using concordant templates represent the maximum possible quality scores and serve as positive controls, whereas scores from discordant sequence and template pairs represent the magnitude of the difference between subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B. The

PlP5A sequences modeled with the Spf1 templates (i.e., concordant) had notably higher GMQE scores and slightly higher QMEANDisCo scores than those modeled with the discordant templates (7m5x and 7m5v). This was not observed with the

Plasmodium subtype-P5B ATPases which exhibited essentially the same quality scores with either the concordant or discordant templates. The

P. falciparum sequences have lower GMQE scores than the

P. relictum sequences, which is likely due to the smaller variable regions in the

P. relictum proteins. Magnesium was the most often retained ligand and was only excluded in a few instances and only with templates bound with non-hydrolysable ATP analogs. The substrates and non-hydrolysable ATP analogs were not retained in any models. There were a few instances of models retaining the BeF

3 using the ATP13A2 template.

The quality assessments indicate that the models of the Plasmodium type-P5 ATPases are relatively accurate, and the quality assessments did not substantially favor one template over the other in subtype-P5B ATPases. In contrast, the concordant template (i.e., Spf1) was favored in the subtype-P5A ATPases.

3.5. A-Domain

The A-domain is formed by a segment between the NTD and cTM1 plus the loop between cTM2 and cTM3. The loop between cTM2 and cTM3 is composed of eight primarily anti-parallel β-strands which form a structure called a distorted jelly roll [

6]. The order of the β-strands in the β-sheet according to linear amino acid sequence is b2-b1-b3-b8-b4-b7-b5-b6, and b4 and b7 are parallel while the other β-strands are anti-parallel. Two α-helices connected to cTM1 and a third α-helix connected to cTM3 are stacked against this β-sheet. These basic features of the distorted jelly roll are found in the experimentally determined structures of Spf1 and ATP13A2 except for some minor differences (

Figure 4a). For example, Spf1 appears to be missing β-strand-6 and both Spf1 and ATP13A2 have a short β-strand of two amino acids (designated b6’) that is found between β-strand-4 and β-strand-7 which is not found in the standard distorted jelly roll. This short β-strand (b6’) is not observed in any of the models generated with either concordant or discordant templates, and β-strand-6 is present in all the models generated with both templates (

Figure S3). Except for the perplexing case of the experimentally determined structure of Spf1, the distorted jelly roll is the same as the known structure of the A-domain of type-P5 ATPases.

The predicted A-domain structures of the

Plasmodium type-P5 ATPases are similar to the experimentally determined structures, and the same structures were produced with either concordant or discordant templates (

Figure S3). Differences in the modeled

Plasmodium proteins were minor, inconsistent, or of dubious importance. All three subtype-P5A ATPases modeled with the ATP13A2 template (discordant) had an extra helix in a short segment of low sequence homology between β-strand-7 and β-strand-8 (

Figure 4b). However, this helix (h’) was not observed in the experimentally determined structure of Spf1 nor in the predicted structures with the concordant template (6xmu). An additional short β-strand (b’) that is not part of the β-sheet was observed in PfATPase1 and PrP5A and an additional short helix (h”) is seen in PrP5A. This additional β-strand is also seen in the experimentally determined ATP13A2 structure but not found in the modeled structures produced with either template. These additional elements are found in regions of low sequence homology (

Figure 4b). A large portion of N-terminal sequence, including part of the A-domain, was excluded from the

P. falciparum subtype-P5A structure modeled with either 6xmu or 7m5x templates and from the

P. relictum subtype-P5A structure modeled with 7m5x. In summary, there are no major differences in the A-domain between subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B ATPases including the

Plasmodium type-P5 ATPases.

3.6. N-Domain

N-domains have been described as either a six-stranded twisted antiparallel β-sheet [

35] or a seven-stranded twisted antiparallel β-sheet [

6,

36] flanked by four [

6,

35] or five [

36] α-helices. The basic structure of the N-domain of both Spf1 and ATP13A2 consists of a twisted six-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet flanked by four α-helices (

Figure 5), thus, both are similar to the Cu-transporting P-type ATPase [

35]. Additional β-strands are observed in both Spf1 and ATP13A2 (

Figure 5). Two additional β-strands of two amino acids each are observed in Spf1 between α-helix-1 and α-helix-2 and are not likely to be incorporated into the twisted β-sheet. These short β-strands are not found in any of the modeled structures (

Figure S4a). In ATP13A2 the additional β-strands are located between α-helix-2 and β-strand-2 and are potentially in close enough proximity to be part of the β-sheet. These two β-strands are found in the model structures of ATP13A2 and Spf1 using the ATP13A2 template but are not found in any of the modeled

Plasmodium ATPases (

Figure S4b). The sequence encoding these additional β-strands is in a short non-conserved region that tends to form IDL (

Figure 5b), thus raising questions about their validity or significance. Except for the extra β-strands, the N-domain structures of Spf1 and ATP13A2 are nearly identical.

The predicted structures of the N-domains from the

Plasmodium type-5 ATPases are very similar to the structures of Spf1 and ATP13A2 except for the lack of the extra β-strands (

Figure S5). No substantial differences between subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B ATPases are seen in the N-domain and no unique features of the

Plasmodium type-5 ATPases were observed. The N-domain of the type-P5 ATPases is highly conserved in regard to its secondary structural features.

3.7. P-Domain

The P-domain of SERCA is described as a modified Rossmann fold with a six-stranded parallel β-sheet and six associated α-helices [

6]. The Rossmann fold is a common tertiary structure found in proteins that bind nucleotides [

37]. This modified Rossmann fold is formed from alternating β-strands and α-helices with the resulting β-sheet being somewhat sandwiched between two rows of α-helices. The fourth helix has a kink resulting in two closely associated helices designated as helix-4a and helix-4b. For the most part, the β-strands and α-helices making up this modified Rossmann fold are readily identified in the experimentally determined structure of Spf1 and ATP13A2 (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). In addition, two additional parallel β-strands (b7 and b8), two additional anti-parallel β-strands (b’ and b”), and an additional α-helix (h’) are observed.

The experimentally determined structures of Spf1 and ATP13A2 are quite similar to each other except that ATP13A2 is missing the α-helix-3 (

Figure 7). However, homology modeling of the ATP13A2 sequence with the Spf1 template results in random-coil sequence in the shape of a helix at this position (

Figure 6), and modeling of the Spf1 sequence with the ATP13A2 template results in the loss of this third helix (

Figure 7). In other words, the structures generated with concordant templates better recapitulated the actual experimentally determined structures. Another unique feature of the subtype-P5A P-domain is the presence of a α-helical projection called the arm. Following the arm is an intrinsically disordered region that may interact with the membrane [

9]. The arm is readily identified in the experimentally determined structure of Spf1 and in predicted structure of Spf1 using Spf1 as a template (

Figure 6). As expected, no arm is seen in either the experimentally determined structure of ATP13A2 nor the predicted structure using the Spf1 template. These results confirm that subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B differ in regard to the presence of the arm structure and imply that there may be a difference between the Rossmann folds of subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B ATPases, especially in the region of the third helix.

Homology modeling of the

Plasmodium subtype-P5A ATPases with the Spf1 (i.e., concordant) generates structures similar to the experimentally determined Spf1 with all the expected secondary structures of the Rossmann fold (

Figure 6). However, a shorter than expected arm is predicted in the PrP5A structure, and no arm is predicted in the PfP5A structure. As expected, no arms are predicted in ATPase1 or ATPase3. In contrast, there were several missing secondary structural elements in ATPase1 and ATPase3 (i.e., subtype-P5B

Plasmodium sequences) modeled with Spf1 (i.e., discordant), as well as β-strand-b” of

PrATPase1 being generated from variable region-4 sequence. The ATP13A2 template performed approximately equally well with

Plasmodium types-P5A (i.e., discordant) and subtype-P5B ATPases (i.e., concordant) (

Figure 7). For example, the ATP13A2 template also generated several instances of variable sequence being incorporated into the secondary structures of the P-domain in both concordant and discordant structures. There were also several instances of missing secondary structural elements in both concordant and discordant structures. These anomalies are restricted to the central part of the P-domain in a region that does not exhibit a high level of sequence homology and that includes VR4 of ATPase1/3 and VR6 of PlP5A (

Figure 8). In particular, β-strand-3, helix-3, β-strand-4, and helix-4a are in a region of low sequence homology.

3.8. Variable Regions Effects

Overall, the predicted structures of the

Plasmodium type-P5 ATPases are quite similar to the experimentally determined structures, and this is especially true for the A- and N-domains. The relatively minor discrepancies in the P-domain of the predicted structures are often associated with the variable regions composed of IDL. The potential effects of the variable regions were analyzed by modeling the

Plasmodium subtype-P5B ATPase sequences with or without variable regions using the Spf1 and ATP13A2 templates. In general, removing the variable regions more than doubled the GMQE scores, increased the QMEANDisCo scores by 20% or more, and increased the percentage of Ramachandran favorable

and Θ angles by 10% or more (

Table 4). The retention of ligands did not appear to be affected by the presence or absence of variable regions.

Removing the variable regions for the most part either had no effect on the predicted structures or improved the homology modeling by generating structures that better recapitulated the experimentally determined structures (

Figure S5 and

Table 5). For example, most of the predicted structures of ATPase1 and ATPase3 were missing part of the NTD and removing the variable regions partially or completely restored the membrane associated helices of the NTD. Similarly, for the most part, the minor discrepancies in the P-domain were corrected by removing the variable regions. When there were no discrepancies, removing the variable regions did not introduce discrepancies except for a loss of β-strands in the P-domain of PrATPase3. There was no obvious correlation between the size of the variable regions and whether their removal had a positive, neutral, or negative impact on the predicted 3-dimensional structures.

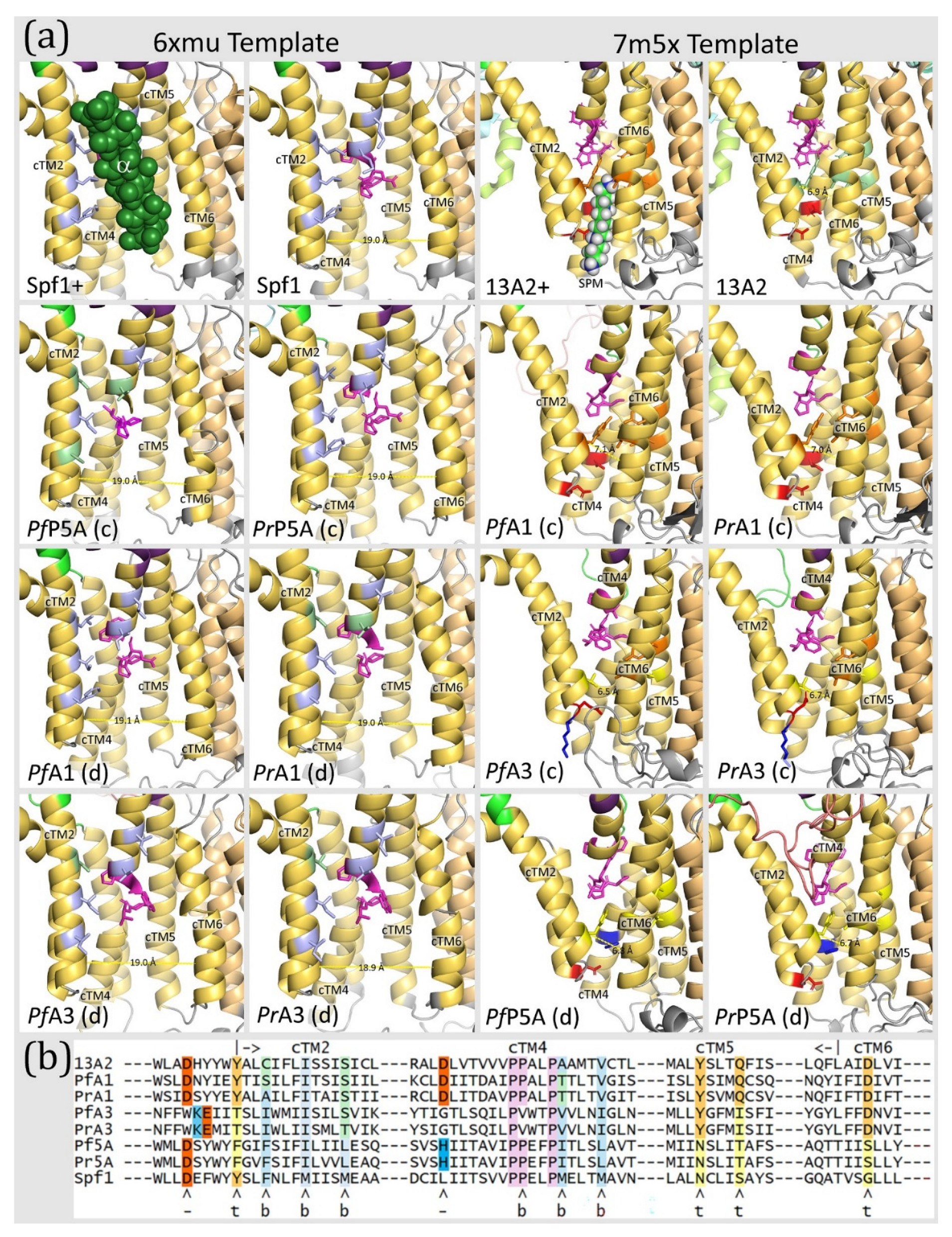

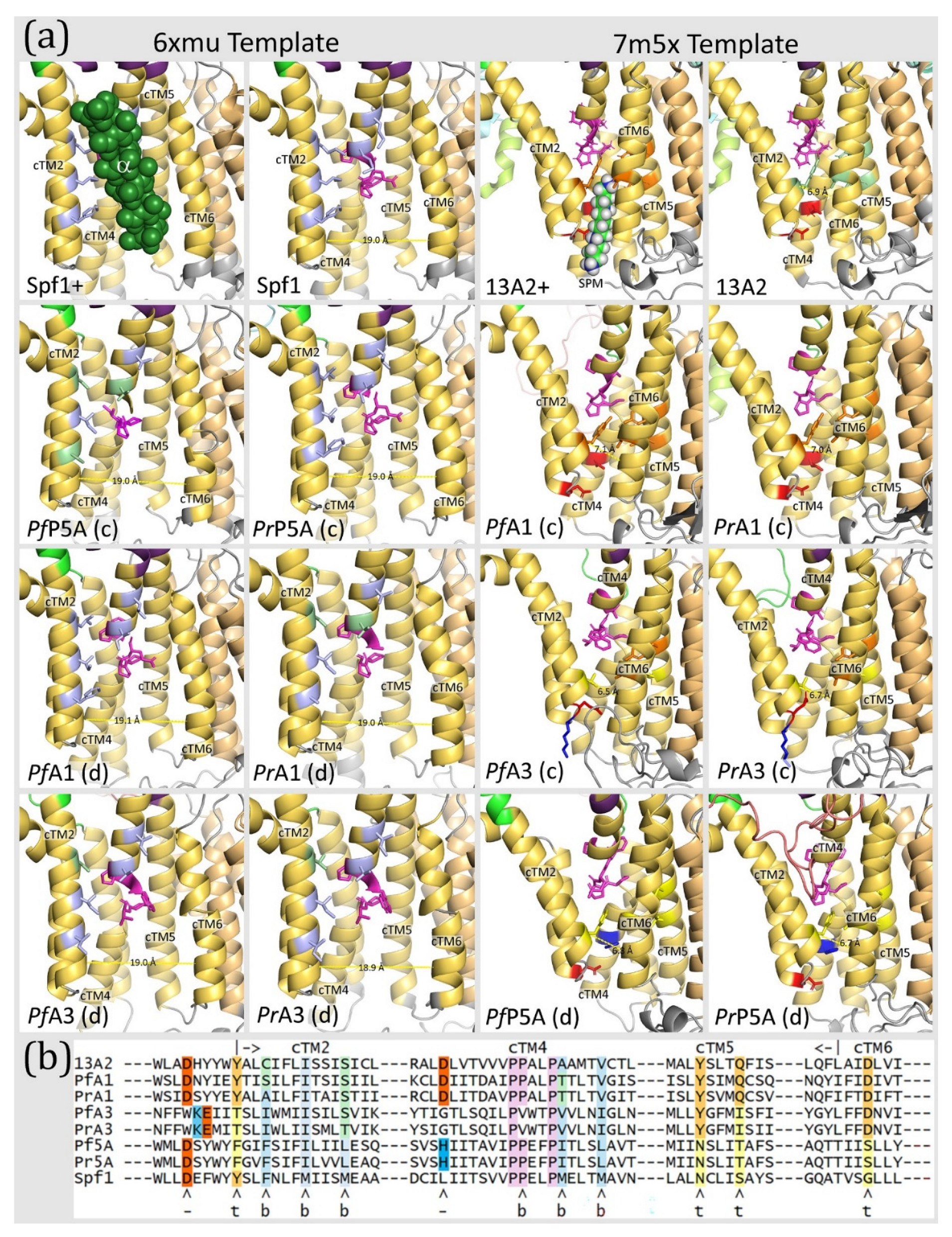

3.9. Substrate-Binding Site

The substrate-binding sites of P-type ATPases are formed from the core transmembrane helices, and cTM2, cTM4, and cTM6 often interact with the substrate [

1]. These helices wrap around to form an incomplete cylindrical structure that makes up the substrate-binding groove. This groove typically opens to the extra-cytoplasmic face of the membrane and the kink in cTM4 forms the base. Subtype-P5A ATPase has a much wider substrate groove than subtype-P5B to accommodate the transmembrane-helix substrate, and the groove opens laterally within the lipid bilayer. This wider substrate groove is due to cTM5 and cTM6 rotating away from the other cTM [

8]. For example, the distance between cTM2 and cTM6 is approximately 19 Å in Spf1 and 7 Å in ATP13A2 (

Figure 9). Important residues in Spf1 are six non-polar amino acids on cTM2 and cTM4 that interact with the α-helical substrate [

12]. These are F223, M227 and M231 of cTM2, P445 of the kink in cTM4, and M449 and M453 of cTM4b. The substrate-binding groove of ATP13A2 is stabilized by interactions between Y259 in cTM2, Y940 and Q944 in cTM5, and D967 in cTM6 called the tetrad [

11]. In addition, aspartates that provide negative charges to interact with the positive charges of polyamines have also been identified.

Homology modeling of the

Plasmodium subtype-P5A ATPases with the Spf1 template yields structures that are essentially identical to the experimentally determined Spf1 structures and the six residues implicated in substrate binding are all non-polar (

Figure 9). Somewhat unexpectant though, modeling

Plasmodium subtype-P5A ATPases with the discordant template produces a substrate-binding groove essentially identical to the experimentally determined ATP13A2 structure (i.e., subtype-P5B). However, none of the stabilizing tetrad amino acids are conserved and only one of the aspartates is conserved and the other is replaced with a positively charged histidine. Thus, even though the discordant structure recapitulates the subtype-P5B ATPase, key residues are missing, and therefore the

Plasmodium subtype-P5A ATPases are not likely to be polyamine transporters.

Likewise, modeling of ATPase1 and ATPase3 with the concordant template produced models essentially identical to ATP13A2 and the discordant template produced models essentially identical to Spf1. As previously noted [

13], the residues making up the tetrad and the aspartate residues of ATPase1 are identical to ATP13A2, whereas these residues are only partially conserved in ATPase3. In regard to the discordant template, the six non-polar residues implicated in substrate binding are all non-polar in ATPase3, whereas 5/6 of the residues are non-polar in PrATPase1 and 4/6 residues are non-polar in PfATPase1. However, these three polar residues are next to non-polar residues. The conservation of the non-polar residues that interact with the substrate suggests that

Plasmodium subtype-P5B ATPases may be able to conform to α-helix dislocase activity.

4. Discussion

Type-P5 ATPases are not well characterized, and this is especially true for the type-P5 ATPases of the malaria parasite. Malaria parasites, like most other eukaryotes, have two type-P5 ATPases designated as subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B. The subtype-P5A gene and protein of

Plasmodium have not yet been characterized other than to be listed as part of genomic surveys [

28] or phylogenetic studies [

12]. Two subtype-P5B ATPases have been identified in the major human pathogen

Plasmodium falciparum and designated as ATPase1 and ATPase3. ATPase1 is not found in all species of malaria parasites and is limited to the parasites of great apes (i.e.,

Laverania), avian malaria parasites, and

Haemoproteus [

13]. ATPase1 arose from a duplication of the ATPase3 gene early in the evolution of the malaria parasite. Further characterization of the type-P5 ATPases from the malaria parasite using Spf1, a subtype-P5A ATPase of yeast, and ATP13A2, a subtype-P5B ATPase of humans, as templates provided insight into the structures of the

Plasmodium type-P5 ATPases, revealed a possible role for the IDL associated with these proteins, allowed for speculation about the possible functions of type-P5 ATPases in the malaria parasite, and possibly contributed to a better understanding of the evolution of the type-P5 ATPases.

4.1. Homology Modeling and Predicted Structures

Sequence alignments and homology modeling of the

Plasmodium type-P5 ATPases identified all the expected canonical domains found in P-type ATPases (i.e., A, N, P, and M). The predicted secondary structures of these canonical domains recapitulated experimentally determined structures with relatively minor discrepancies whether concordant (i.e., same subtype) or discordant (i.e., different subtype) templates were used in homology modeling. Many of these discrepancies disappeared if the regions corresponding to the IDL were removed from the sequences before modeling. This suggests that large intrinsically disorganized regions may interfere with homology modeling. Even though this effect is relatively minor, it may be prudent to carry out modeling on both complete protein sequences and sequences with large regions of low-complexity sequence removed. This may be especially important for proteins of the malaria parasite since large regions of low-complexity sequence are often found in

Plasmodium proteins [

15]. In contrast to the canonical P-type ATPase domains, the NTD and CTE were not always accurately modeled, and often the N-terminal and C-terminal regions were excluded from the predicted three-dimensional structures.

The secondary structural features of the A- and N-domains were nearly identical between the subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B ATPases whether concordant or discordant templates were used. This emphasizes the similarity between the two subtypes of the type-P5 ATPases. Overall, homology modeling predicted structures that recapitulated the known structures of type-P5 ATPases and it is likely that the subtype-P5A proteins from Plasmodium have a similar structure as other subtype-P5A ATPases and ATPase1 and ATPase3 have similar structures as other subtype-P5B ATPases. The good performance of homology modeling also indicates that homology modeling will be a useful tool in future studies of these proteins and may be useful in preliminary studies to search for possible drugs targeting P-type ATPases.

Differences between subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B ATPases are primarily in the membrane associated helices of the NTD, the arm of the P-domain, and the substrate specificity [

8]. For example, the subtype-P5A NTD has two additional transmembrane helices and the subtype-P5B NTD has a triangular membrane loop that does not traverse the lipid bilayer. Homology modeling of the

Plasmodium type-P5 ATPases did correctly generate these structures when concordant templates were used and especially if the variable regions were removed from the protein sequences. Another difference between subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B is a α-helical projection in the P-domain called the arm that is not found in subtype-P5B. As expected, no arm structures are found in ATPase1 or ATPase3 and this arm was predicted in the PrP5A sequence with the Spf1 (i.e., concordant) template and not the ATP13A2 (i.e., discordant) template. It is not clear why the arm was not predicted in PfP5A. An extra α-helix was observed in the Rossmann fold of the P-domain in the subtype-P5A ATPases which was not seen in the subtype-P5B ATPases. This extra helix may possibly be another structural feature to distinguish subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B ATPases and merits further investigation. To accommodate their distinct substrates, the substrate binding groove of Spf1 is much wider than the narrow groove of ATP13A2.

4.2. Limitations of Homology Modeling

Discordant templates revealed a potential limitation of homology modeling since the predicted 3-dimensional structures had a strong tendency to recapitulate the template, especially in the NTD and substrate-binding grove. For example, homology modeling of the

Plasmodium subtype-P5A ATPase with the subtype-P5B template (i.e., discordant) generated the triangular membrane loop, whereas modeling with the concordant template produced the expected transmembrane helices. This same effect of the predicted structures reflecting the templates was also observed in the

Plasmodium subtype-P5B ATPases. However, in the case of the NTD the concordant templates did produce structures of slightly higher quality in regard to recapitulating the experimentally determined structures than the discordant templates. This was not true with the substrate-binding groove. The homology models were essentially identical to the experimentally determined structures of the templates and both concordant and discordant templates appeared to generate structures of equal quality. Thus, it will be important to use the correct template when carrying out homology modeling and to have a means to choose the correct template among multiple possible templates. For example, the Spf1 template ranked equally well to subtype-P5B templates in an analysis of subtype-P5B ATPases using Phyre

® [

13].

Another limitation is that most experimental work on eukaryotes has been carried out in humans and other mammals or yeasts. In terms of eukaryotic diversity, fungi and metazoans are relatively closely related as members of the opisthokonts in a major eukaryotic supergroup, or clade, that includes some amoeba called Amorphea [

38]. Little experimental work has been carried out in the other major eukaryotic supergroups other than perhaps plants and a smattering of pathogenic eukaryotes. It is not inconceivable that even highly conserved proteins may exhibit structural or functional differences between the major eukaryotic supergroups. In regard to this study, experimentally determined structures from other apicomplexans or members of SAR supergroup, which represents half of all eukaryote diversity [

39], may be informative and useful as templates. Thus, more experimental data reflecting the extreme diversity of eukaryotes is clearly needed.

4.3. Possible Functions of IDL

An obvious unique feature of the predicted structures of the

Plasmodium type-P5 ATPases is the presence of large loops of intrinsically disorganized sequence. Intrinsically disorganized regions in proteins are random coil secondary structures that lack bulky hydrophobic amino acids and do not adopt a tertiary structure with a hydrophobic core [

40,

41]. Traditionally, IDL were viewed as passive linkers between structured domains, but are now known to have functional roles [

42]. For example, IDL can be involved in the formation of protein complexes and higher-order supramolecular structures [

43]. The flexibility of the IDL allows them to take on many conformations and may allow for an induced fit as they bind ligands including other proteins. Thus, the IDL may allow for low-affinity interactions with other proteins. At the same time, the physical mass of the IDL, which ranges from one-third to one-half in the type-P5 ATPases of

Plasmodium, could also provide spacing between proteins.

The flexibility of the IDL could also form a shroud-like structure that surrounds the core ATPase structure. Such a shroud could have a protective role and prevent damage to the primary domains. Similarly, such a shroud may provide a buffer zone for these ATPase molecules so that other proteins on the membrane do not inadvertently interact with them and thus possibly interfere with their function. A protective role of the shroud and a role in protein-protein interactions are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

The IDL are correlated with inserts of variable regions which intuitively would argue against a specific function. However, these variable regions only exhibit variation between the eight haemosporidian clades and are conserved within the individual haemosporidian clades for both subtype-P5A (

Figure S1) and subtype-P5B [

13]. These variable regions are composed of low-complexity sequences that are highly enriched in polar amino acids, as are IDL in general [

40,

41]. Thus, despite the lack of sequence conservation, the flexibility and similar amino acid composition of the IDL could preserve a function such as low affinity binding to other proteins. Indeed, low-complexity sequence has been demonstrated to be subject to natural selection [

44]. The observation that tandem repeats are often observed in these low-complexity regions suggests a mechanism to explain the variability and preservation of the amino acid composition. A periodic replacement and expansion of tandem repeats through slipped-strand mispairing [

45] or unequal crossing-over [

46] could occur on a similar evolutionary timeframe as the formation of the major haemosporidian clades.

4.4. Substrate Specificity

The substrate specificity of P-type ATPases and their subcellular locations are key elements regarding their functions [

8]. Subtype-P5A ATPases are localized to the ER [

47] and have been previously hypothesized to transport calcium [

48], manganese [

49], or lipids [

50]. Recent studies indicate that Spf1 is likely a transmembrane helix dislocase [

8,

11]. Presumably this dislocase activity serves as a quality control mechanism to remove mistargeted transmembrane helices from the ER membrane. Consistent with this function, a subtype-P5A ATPase from

Caenorhabditis elegans plays a role in correctly targeting membrane and secretory proteins [

51]. Other than some early speculation that subtype-P5B might be heavy metal transporters [

52], most studies have characterized subtype-P5B ATPases as polyamine transporters of the late endosomes or lysosomes [

10,

53,

54,

55,

56].

Homology modeling by itself cannot resolve the substrate specificity of the

Plasmodium type-P5 ATPases since the substrate-binding sites conform to the template. Nonetheless, it is quite likely that

Plasmodium subtype-P5A ATPases are helix dislocases. This assertion is supported by the observation that the key residues for binding to the α-helix substrate are conserved, whereas as key residues involved in polyamine binding are less conserved (

Figure 9). Helix dislocase activity is likely a necessary quality control mechanism in the ER and disruption of the gene has adverse pleiotropic effects [

8,

57]. The subtype-P5A gene is found in all eukaryotes and with few exceptions it is a single copy gene [

58], and it is believed that subtype-P5A may have a general and highly conserved function [

47]. The very high level of sequence conservation, except for the variable region inserts, within the haemosporidians (

Figure S1), and identification of clear orthologues throughout the SAR (

Table S1) further support a conserved function of the subtype-P5A ATPases in all eukaryotes including the malaria parasite.

In contrast, as previously discussed [

13], it is unlikely that the haemosporidian subtype-P5B ATPases are lysosomal polyamine transporters. Previously published immunofluorescence data [

17,

18,

19] are more reminiscent of ER staining, and proteomic analysis did not detect any P-type ATPases in the lysosomal compartment (i.e., digestive vacuole) of the malaria parasite [

59]. Furthermore, malaria parasites are capable of synthesizing polyamines [

60] and have a plasma membrane associated polyamine transporter to take up polyamines from the host cell cytoplasm [

61]. In addition, clear orthologues of ATPase3 can only be identified in the apicomplexans and ATPase1 is limited to only some of the malaria parasites [

13]. If the apicomplexan and opisthokont subtype-P5B ATPases had the same function one might expect to be able to identify clear orthologues throughout the eukaryotes. Determining the substrate specificity of the haemosporidian or apicomplexan subtype-P5B ATPases will likely require experimental verification.

4.5. Divergent Evolution of Subtype-P5B ATPases

Type-P5 ATPases likely originated during the early evolution of eukaryotes, and its origin was likely coincident with the formation of the ER and other internal membrane systems [

12,

58]. The duplication and divergence into subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B also likely occurred in a primordial eukaryote before the formation of the major eukaryote supergroups. A limited number of subsequent duplications of subtype-P5A have also been noted in the archaeplastids and stramenopiles [

58]. In contrast, subtype-P5B has been duplicated many times in several different eukaryotic lineages [

8,

12,

13]. In addition, subtype-P5B is not found in all eukaryotes, and this is usually attributed to lineage specific losses of subtype-P5B [

12]. For example, gene loss certainly explains the lack of subtype-P5B in

Entamoeba since these organisms are amorpheans, as are fungi and metazoans which have subtype-P5B. Therefore, it is likely a loss of the subtype-P5B gene occurred after the amoebozoans split from the opisthokonts.

Duplicated genes can undergo divergent evolution, and this allows for an expansion and diversification of gene families and provides opportunities for innovation and adaptation to new environments or physiological milieus [

62]. Following the split into subtype-P5A and subtype-P5B it is probable that subtype-P5A maintained its function as an ER helix dislocase in all eukaryotes. Subtype-P5B, on the other hand, may have evolved new functions in a lineage-specific manner. For example, subtype-P5B in the opisthokonts diverged into a polyamine transporter located in the lysosome. In contrast to the opisthokonts, the subtype-P5B ATPases of the malaria parasite appear to have maintained their location in the ER and did not evolve to transport polyamines. Therefore, it is unlikely that subtype-P5B ATPases have a common function in all eukaryotes and there could be lineage specific functions in the various eukaryotic supergroups.

The retention of subtype-P5B ATPase in the ER of malaria parasites implies a possible retention and localization of subtype-P5B ATPases to the ER throughout the Apicomplexa and even perhaps the SAR supergroup. This could represent redundancy or perhaps a divergence to a more specialized function. Furthermore, homology modeling with the discordant subtype-P5A template indicates that ATPase1 and ATPase3 can at least in theory might be capable of helix dislocase activity. In addition, the observation that the

Plasmodium subtype-P5B ATPases are approximately equal distance from Spf1 and ATP13A2 in phylogenetic pairwise analyses (

Table 3) is also consistent with

Plasmodium subtype-P5B ATPases having a similar function as subtype-P5A ATPases. Similarly, the quality assessment scores of

Plasmodium subtype-P5B ATPases are approximately the same with concordant or discordant templates suggesting no strong preference for either template. In contrast, the subtype-P5A ATPase shows a preference for concordant templates over discordant templates. Therefore, it is not inconceivable that the subtype-P5B ATPases of

Plasmodium, other apicomplexans and members of SAR have a function similar to the subtype-P5A ATPases.

Maintenance of two genes with similar functions allows for divergence in regard to the precise substrate specificity. For example, subtype-P5A ATPases have also been implicated in the removal of signal peptides from the ER membrane [

8]. Interestingly, the malaria parasite and other apicomplexans may have two distinct pathways targeting proteins for export [

63]. One of these pathways involves the traditional signal peptide and the other involves a signal called PEXEL [

64]. PEXEL signaling is also found in some stramenopiles [

65]. As highly hypothetical speculation, one could propose the need for different helix dislocases to remove these rather different peptide signals from the ER membrane.

5. Conclusions

The subtype-P5A ATPase of malaria parasites is likely a helix dislocase of the ER as are other subtype-P5A ATPases. In contrast, the subtype-P5B ATPases of the malaria parasite have likely diverged from other subtype-P5B ATPases and are not polyamine transporters of the lysosome. Experimental verification of cellular locations and substrate specificities of the type-P5 ATPases of the malaria are needed. A notable difference between the type-P5 ATPases of the malaria parasite and other subtype-P5A ATPases are the insertion of variable regions composed of low complexity sequence. This low complexity sequence may form a shroud that surrounds the core of the ATPase which may function in low-affinity protein-protein interactions or protection of the core ATPase.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Identification of subtype-P5A ATPase genes in SAR (Stramenopiles, Alveolata, and Rhizaria); Figure S1: Alignment and phylogeny of subtype-P5A ATPases from haemosporidians; Figure S2: Alignment of Plasmodium type-P5 ATPases with Spf1 (type-P5A) and 13A2 (type-P5B); Figure S3: A-domain structure of type-P5 ATPases; Figure S4: N-domain structure of type-P5 ATPases; Figure S5. Effects of low complexity variable regions on homology modeling.

Author Contributions

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Contact author to receive data generated by this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| cTM |

core transmembrane helix |

| CTE |

C-terminal extension |

| IDL |

intrinsically disorganized loops |

| PEXEL |

Plasmodium export element |

| PlP5A |

Plasmodium subtype-P5A ATPase |

| SAR |

stramenopiles-alveolates-rhizarians |

| SERCA |

sarcoplasmic-endoplasmic reticulum ATPase |

References

- Palmgren, M. P-Type ATPases: Many More Enigmas Left to Solve. J Biol Chem 2023, 299, 105352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.E.; Henry, R.I.; Abbey, J.L.; Clements, J.D.; Kirk, K. The “permeome” of the Malaria Parasite: An Overview of the Membrane Transport Proteins of Plasmodium Falciparum. Genome Biol 2005, 6, R26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnou, B.; Montigny, C.; Morth, J.P.; Nissen, P.; Jaxel, C.; Møller, J.V.; Maire, M. le The Plasmodium Falciparum Ca2+-ATPase PfATP6: Insensitive to Artemisinin, but a Potential Drug Target. Biochem Soc Trans 2011, 39, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.; Pulcini, S.; Fatih, F.; Staines, H. Artemisinins and the Biological Basis for the PfATP6/SERCA Hypothesis. Trends Parasitol 2010, 26, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiser, A. Template-Based Protein Structure Modeling. Methods Mol Biol 2010, 673, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, D.L.; Green, N.M. Structure and Function of the Calcium Pump. Annu Rev Biophys 2003, 32, 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelsen, K.B.; Palmgren, M.G. Evolution of Substrate Specificities in the P-Type ATPase Superfamily. J Mol Evol 1998, 46, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, S.I.; Park, E. P5-ATPases: Structure, Substrate Specificities, and Transport Mechanisms. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2023, 79, 102531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, M.J.; Sim, S.I.; Ordureau, A.; Wei, L.; Harper, J.W.; Shao, S.; Park, E. The Endoplasmic Reticulum P5A-ATPase Is a Transmembrane Helix Dislocase. Science 2020, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, K.; Salustros, N.; Grønberg, C.; Gourdon, P. Structure and Transport Mechanism of P5B-ATPases. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillinghast, J.; Drury, S.; Bowser, D.; Benn, A.; Lee, K.P.K. Structural Mechanisms for Gating and Ion Selectivity of the Human Polyamine Transporter ATP13A2. Mol Cell 2021, 81, 4650–4662.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møller, A.B.; Asp, T.; Holm, P.B.; Palmgren, M.G. Phylogenetic Analysis of P5 P-Type ATPases, a Eukaryotic Lineage of Secretory Pathway Pumps. Mol Phylogenet Evol 2008, 46, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiser, M.F. Duplication of a Type-P5B-ATPase in Laverania and Avian Malaria Parasites and Implications about the Evolution of Plasmodium. Parasitologia 2025, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, G.T.; Beltran, M.M.G.; Gómez-Alegría, C.J.; Wiser, M.F. Identification of a Protein Unique to the Genus Plasmodium That Contains a WD40 Repeat Domain and Extensive Low-Complexity Sequence. Parasitol Res 2021, 120, 2617–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePristo, M.A.; Zilversmit, M.M.; Hartl, D.L. On the Abundance, Amino Acid Composition, and Evolutionary Dynamics of Low-Complexity Regions in Proteins. Gene 2006, 378, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiser, M.F. The Digestive Vacuole of the Malaria Parasite: A Specialized Lysosome. Pathogens 2024, 13, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, S.; Cowan, G.; Meade, J.C.; Wells, R.A.; Stringer, J.R.; Robson, K.J. A Family of Cation ATPase-like Molecules from Plasmodium Falciparum. Journal of Cell Biology 1993, 120, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozmajzl, P.J.; Kimura, M.; Woodrow, C.J.; Krishna, S.; Meade, J.C. Characterization of P-Type ATPase 3 in Plasmodium Falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2001, 116, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, M.; Tanabe, K.; Krishna, S.; Tsuboi, T.; Saito-Ito, A.; Otani, S.; Ogura, H. Gametocyte-Dominant Expression of a Novel P-Type ATPase in Plasmodium Yoelii. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1999, 104, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiser, M.F.; Lanners, H.N.; Bafford, R.A.; Favaloro, J.M. A Novel Alternate Secretory Pathway for the Export of Plasmodium Proteins into the Host Erythrocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94, 9108–9113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikawa, M. Parasitological Review. Plasmodium: The Fine Structure of Malarial Parasites. Exp Parasitol 1971, 30, 284–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langreth, S.G.; Jensen, J.B.; Reese, R.T.; Trager, W. Fine Structure of Human Malaria in Vitro. J Protozool 1978, 25, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Zaretskaya, I.; Raytselis, Y.; Merezhuk, Y.; McGinnis, S.; Madden, T.L. NCBI BLAST: A Better Web Interface. Nucleic Acids Res 2008, 36, W5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aurrecoechea, C.; Brestelli, J.; Brunk, B.P.; Dommer, J.; Fischer, S.; Gajria, B.; Gao, X.; Gingle, A.; Grant, G.; Harb, O.S.; et al. PlasmoDB: A Functional Genomic Database for Malaria Parasites. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensch, S.; Canbäck, B.; DeBarry, J.D.; Johansson, T.; Hellgren, O.; Kissinger, J.C.; Palinauskas, V.; Videvall, E.; Valkiūnas, G. The Genome of Haemoproteus Tartakovskyi and Its Relationship to Human Malaria Parasites. Genome Biol Evol 2016, 8, 1361–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Lu, S.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; Thanki, N.; Yamashita, R.A.; et al. The Conserved Domain Database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, D384–D388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.E.; Henry, R.I.; Abbey, J.L.; Clements, J.D.; Kirk, K. The “permeome” of the Malaria Parasite: An Overview of the Membrane Transport Proteins of Plasmodium Falciparum. Genome Biol 2005, 6, R26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology Modelling of Protein Structures and Complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, G.J.; Brown, W.M. Amphioxus Mitochondrial DNA, Chordate Phylogeny, and the Limits of Inference Based on Comparisons of Sequences. Systematic Bology 1998, 47, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cepeda, A.S.; Mello, B.; Pacheco, M.A.; Luo, Z.; Sullivan, S.A.; Carlton, J.M.; Escalante, A.A. The Genome of Plasmodium Gonderi: Insights into the Evolution of Human Malaria Parasites. Genome Biology and Evolutioniology and Evolution 2024, 16, evae027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, D.E.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Learn, G.H.; Plenderleith, L.J.; Sundararaman, S.A.; Sharp, P.M.; Hahn, B.H. Out of Africa: Origins and Evolution of the Human Malaria Parasites Plasmodium Falciparum and Plasmodium Vivax. Int J Parasitol 2017, 47, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, M.A.; Escalante, A.A. Origin and Diversity of Malaria Parasites and Other Haemosporida. Trends Parasitol 2023, 39, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhme, U.; Otto, T.D.; Cotton, J.A.; Steinbiss, S.; Sanders, M.; Oyola, S.O.; Nicot, A.; Gandon, S.; Patra, K.P.; Herd, C.; et al. Complete Avian Malaria Parasite Genomes Reveal Features Associated with Lineage-Specific Evolution in Birds and Mammals. Genome Res 2018, 28, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banci, L.; Bertini, I.; Cantini, F.; Inagaki, S.; Migliardi, M.; Rosato, A. The Binding Mode of ATP Revealed by the Solution Structure of the N-Domain of Human ATP7A. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 2537–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Håkansson, K.O. The Crystallographic Structure of Na,K-ATPase N-Domain at 2.6Å Resolution. J Mol Biol 2003, 332, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.-H.; Kihara, D. 55 Years of the Rossmann Fold. Methods in Molecular Biology 2019, 1958, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiser, M.F. Protozoa. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity (Volume 2); Scheiner, S.M.B.T., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, 2024; ISBN 978-0-323-98434-8. [Google Scholar]

- Grattepanche, J.-D.; Walker, L.M.; Ott, B.M.; Paim Pinto, D.L.; Delwiche, C.F.; Lane, C.E.; Katz, L.A. Microbial Diversity in the Eukaryotic SAR Clade: Illuminating the Darkness between Morphology and Molecular Data. BioEssays 2018, 40, 1700198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, P.; Chakravarty, D. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins/Regions and Insight into Their Biomolecular Interactions. Biophys Chem 2022, 283, 106769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, H.J.; Wright, P.E. Intrinsically Unstructured Proteins and Their Functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005, 6, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N.; Kulkarni, P. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: Chronology of a Discovery. Biophys Chem 2021, 279, 106694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Fuxreiter, M. The Structure and Dynamics of Higher-Order Assemblies: Amyloids, Signalosomes, and Granules. Cell 2016, 165, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, S.R.; Lwin, N.; Phelan, D.; Escalante, A.A.; Battistuzzi, F.U. Comparative Analysis of Low Complexity Regions in Plasmodia. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viguera, E.; Canceill, D.; Ehrlich, S.D. Replication Slippage Involves DNA Polymerase Pausing and Dissociation. EMBO J 2001, 20, 2587–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, H.M.; Nofal, S.D.; McLaughlin, E.J.; Osborne, A.R. Repetitive Sequences in Malaria Parasite Proteins. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2017, 41, 923–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, D.M.; Holemans, T.; van Veen, S.; Martin, S.; Arslan, T.; Haagendahl, I.W.; Holen, H.W.; Hamouda, N.N.; Eggermont, J.; Palmgren, M. Parkinson Disease Related ATP13A2 Evolved Early in Animal Evolution. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0193228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, S.R.; Rao, R.; Hampton, R.Y. Cod1p/Spf1p Is a P-Type ATPase Involved in ER Function and Ca2+ Homeostasis. J Cell Biol 2002, 157, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.; Megyeri, M.; Chen, O.C.W.; Condomitti, G.; Riezman, I.; Loizides-Mangold, U.; Abdul-Sada, A.; Rimon, N.; Riezman, H.; Platt, F.M. The Yeast P5 Type ATPase, Spf1, Regulates Manganese Transport into the Endoplasmic Reticulum. PLoS One 2013, 8, e85519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, D.M.; Holen, H.W.; Pedersen, J.T.; Martens, H.J.; Silvestro, D.; Stanchev, L.D.; Costa, S.R.; Günther Pomorski, T.; López-Marqués, R.L.; Palmgren, M. The P5A ATPase Spf1p Is Stimulated by Phosphatidylinositol 4-Phosphate and Influences Cellular Sterol Homeostasis. Mol Biol Cell 2019, 30, 1069–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Li, T.; Nie, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Liao, J.; Zou, Y. CATP-8/P5A ATPase Regulates ER Processing of the DMA-1 Receptor for Dendritic Branching. Cell Rep 2020, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veen, S.; Sørensen, D.M.; Holemans, T.; Holen, H.W.; Palmgren, M.G.; Vangheluwe, P. Cellular Function and Pathological Role of ATP13A2 and Related P-Type Transport ATPases in Parkinson’s Disease and Other Neurological Disorders. Front Mol Neurosci 2014, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, S.I.; von Bülow, S.; Hummer, G.; Park, E. Structural Basis of Polyamine Transport by Human ATP13A2 (PARK9). Mol Cell 2021, 81, 4635–4649.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veen, S.; Martin, S.; Van den Haute, C.; Benoy, V.; Lyons, J.; Vanhoutte, R.; Kahler, J.P.; Decuypere, J.-P.; Gelders, G.; Lambie, E. ATP13A2 Deficiency Disrupts Lysosomal Polyamine Export. Nature 2020, 578, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azfar, M.; van Veen, S.; Houdou, M.; Hamouda, N.N.; Eggermont, J.; Vangheluwe, P. P5B-ATPases in the Mammalian Polyamine Transport System and Their Role in Disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research 2022, 1869, 119354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, S.; Yin, J.; Zhang, P.; Xuan, X.; Wang, P.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, B.; Yang, M. Cryo-EM Structures and Transport Mechanism of Human P5B Type ATPase ATP13A2. Cell Discov 2021, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, D.M.; Holen, H.W.; Holemans, T.; Vangheluwe, P.; Palmgren, M.G. Towards Defining the Substrate of Orphan P5A-ATPases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2015, 1850, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmgren, M.; Sørensen, D.M.; Hallström, B.M.; Säll, T.; Broberg, K. Evolution of P2A and P5A ATPases: Ancient Gene Duplications and the Red Algal Connection to Green Plants Revisited. Physiol Plant 2020, 168, 630–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarque, M.; Tastet, C.; Poncet, J.; Demettre, E.; Jouin, P.; Vial, H.; Dubremetz, J.-F. Food Vacuole Proteome of the Malarial Parasite Plasmodium Falciparum. Proteomics Clin Appl 2008, 2, 1361–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.A. Polyamines in Protozoan Pathogens. J Biol Chem 2018, 293, 18746–18756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemand, J.; Louw, A.I.; Birkholtz, L.; Kirk, K. Polyamine Uptake by the Intraerythrocytic Malaria Parasite, Plasmodium Falciparum. Int J Parasitol 2012, 42, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Zhu, W.; Zhou, J.; Li, H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, B.; Gao, X. Repetitive DNA Sequence Detection and Its Role in the Human Genome. Commun Biol 2023, 6, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiser, M.F. Unique Endomembrane Systems and Virulence in Pathogenic Protozoa. Life (Basel) 2021, 11, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullen, H.E.; Crabb, B.S.; Gilson, P.R. Recent Insights into the Export of PEXEL/HTS-Motif Containing Proteins in Plasmodium Parasites. Curr Opin Microbiol 2012, 15, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Hiller, N.L.; Liolios, K.; Win, J.; Kanneganti, T.-D.; Young, C.; Kamoun, S.; Haldar, K. The Malarial Host-Targeting Signal Is Conserved in the Irish Potato Famine Pathogen. PLoS Pathog 2006, 2, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of type-P5 ATPases. The canonical A-domain, N-domain, and P-domain are located on the cytoplasmic face of the membrane along with an N-terminal domain (NTD) and a C-terminal extension (CTE) of variable length. The M-domain (gray background) consists of six core transmembrane (cTM) helices, four supporting transmembrane (sTM) helices, and membrane helices associated with the NTD. Subtype-P5A ATPases have two N-terminal transmembrane helices (nTM) and subtype-P5B has an N-terminal membrane loop (nML) formed by three short helices. Subtype-P5A ATPases have a helical projection from the P-domain that is not found in subtype-P5B ATPases called the “arm”. ATP binding occurs in a crevice between the N-domain and P-domain called the hinge. The transmembrane helix of cTM4 is disrupted by conserved prolines that results in a ‘kink’ in the helix (between 4a and 4b) which plays an essential role in the formation of the substrate-binding groove. Similar nomenclature and color schemes are used in all subsequent figures. A single subtype-P5A ATPase (PlP5A) and two subtype-P5B ATPases (ATPase1 and ATPase3) have been identified in genomes of malaria parasites. PlP5A has a single exon and ATPase1 and ATPase3 have two exons with the position of the intron denoted by a blue arrow near sTM9. PlP5A and ATPase3 have N-terminal extensions that are not found in other type-P5 ATPases. Alignment of PlP5A sequences reveals seven variable regions (VR1-7 green) composed of low-complexity sequence which are denoted with green arrows and lettering. ATPase1 and ATPase3 exhibit four variable regions (VR1-4), three of which are shared with PlP5A, composed of low-complexity sequence and are denoted with blue arrows and lettering.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of type-P5 ATPases. The canonical A-domain, N-domain, and P-domain are located on the cytoplasmic face of the membrane along with an N-terminal domain (NTD) and a C-terminal extension (CTE) of variable length. The M-domain (gray background) consists of six core transmembrane (cTM) helices, four supporting transmembrane (sTM) helices, and membrane helices associated with the NTD. Subtype-P5A ATPases have two N-terminal transmembrane helices (nTM) and subtype-P5B has an N-terminal membrane loop (nML) formed by three short helices. Subtype-P5A ATPases have a helical projection from the P-domain that is not found in subtype-P5B ATPases called the “arm”. ATP binding occurs in a crevice between the N-domain and P-domain called the hinge. The transmembrane helix of cTM4 is disrupted by conserved prolines that results in a ‘kink’ in the helix (between 4a and 4b) which plays an essential role in the formation of the substrate-binding groove. Similar nomenclature and color schemes are used in all subsequent figures. A single subtype-P5A ATPase (PlP5A) and two subtype-P5B ATPases (ATPase1 and ATPase3) have been identified in genomes of malaria parasites. PlP5A has a single exon and ATPase1 and ATPase3 have two exons with the position of the intron denoted by a blue arrow near sTM9. PlP5A and ATPase3 have N-terminal extensions that are not found in other type-P5 ATPases. Alignment of PlP5A sequences reveals seven variable regions (VR1-7 green) composed of low-complexity sequence which are denoted with green arrows and lettering. ATPase1 and ATPase3 exhibit four variable regions (VR1-4), three of which are shared with PlP5A, composed of low-complexity sequence and are denoted with blue arrows and lettering.

Figure 2.

Homology modeling with the Spf1 template. Plasmodium subtype-P5A, ATPase1 (A1), and ATPase3 (A3) sequences from P. falciparum (Pf) and P. relictum (Pr) were modeled by Swiss Model® with the Spf1 (PDB Acc. No. 6xmu) template. Spf1* is the experimentally determined structure and concordant (c) and discordant (d) models are noted. Dashed boxes denote missing elements in the modeled structures. The ‘arm’ (arrow, dark purple) is an α-helix that is specific to subtype-P5A. The A-domain is colored green, the N-domain blue, the P-domain purple, the transmembrane helices yellow, and the NTD aqua with the membrane associated loops light green. The intrinsically disordered loops (IDL) produced by the variable regions are salmon. The white asterisk (*) denotes the α-helix substrate (dark green) in the substrate-binding groove.

Figure 2.

Homology modeling with the Spf1 template. Plasmodium subtype-P5A, ATPase1 (A1), and ATPase3 (A3) sequences from P. falciparum (Pf) and P. relictum (Pr) were modeled by Swiss Model® with the Spf1 (PDB Acc. No. 6xmu) template. Spf1* is the experimentally determined structure and concordant (c) and discordant (d) models are noted. Dashed boxes denote missing elements in the modeled structures. The ‘arm’ (arrow, dark purple) is an α-helix that is specific to subtype-P5A. The A-domain is colored green, the N-domain blue, the P-domain purple, the transmembrane helices yellow, and the NTD aqua with the membrane associated loops light green. The intrinsically disordered loops (IDL) produced by the variable regions are salmon. The white asterisk (*) denotes the α-helix substrate (dark green) in the substrate-binding groove.

Figure 3.

Homology modeling with the ATP13A2 template. Plasmodium subtype-P5A, ATPase1 (A1), and ATPase3 (A3) sequences from P. falciparum (Pf) and P. relictum (Pr) were modeled by Swiss Model® with the ATP13A2 (PDB Acc. No. 7m5x) template. 13A2* is an experimentally determined structure and concordant (c) and discordant (d) models are noted. Dashed boxes denote missing elements in the modeled structures. The A-domain is colored green, the N-domain blue, the P-domain purple, the transmembrane helices yellow, and the NTD aqua with the membrane associated loops light green. IDL produced by the variable regions are colored salmon. The arrow denotes the spermine substrate in the substrate-binding groove.

Figure 3.

Homology modeling with the ATP13A2 template. Plasmodium subtype-P5A, ATPase1 (A1), and ATPase3 (A3) sequences from P. falciparum (Pf) and P. relictum (Pr) were modeled by Swiss Model® with the ATP13A2 (PDB Acc. No. 7m5x) template. 13A2* is an experimentally determined structure and concordant (c) and discordant (d) models are noted. Dashed boxes denote missing elements in the modeled structures. The A-domain is colored green, the N-domain blue, the P-domain purple, the transmembrane helices yellow, and the NTD aqua with the membrane associated loops light green. IDL produced by the variable regions are colored salmon. The arrow denotes the spermine substrate in the substrate-binding groove.

Figure 4.

A-domain of type-P5 ATPases. (

a) Shown are the experimentally determined structures of the A-domain with the eight β-strands (b1-8) of the distorted jelly roll and the three associated α-helices (h1-3) denoted. Beta-strand-6 in ATP13A2 is colored differently as well as the corresponding segment in Spf1 (circled). The circled short β-strand (b6’) in teal is found in experimentally determined structures but none of the modeled structures (

Figure S3). The blue annotations refer to differences in the