1. Introduction

A revolutionary change in the interaction between digital and human tools of creation is being ushered in by the incorporation of generative artificial intelligence into creative design. We are on the cusp of a new era known as "Human-AI Co-Creation," where AI systems actively participate in synergistic creative processes, surpassing their previous function as an adjunct to human creativity.[

1]. The creative design process has been significantly impacted and transformed over the last ten years by the changing landscape of human-AI interaction [

2]. According to this paradigm, artificial intelligence and humans operate together as a cohesive system that promotes group innovation. This partnership creates a unique kind of invention that is the result of ongoing, dynamic interchange rather than just the sum of the individual efforts. The final product exceeds the creative potential of any one agent and exemplifies a synergy that enhances originality beyond what could be accomplished separately[

3].

As AI becomes more and more integrated into everyday human activities, We need to reevaluate how we perceive and use this quickly evolving technology. Non-academic discourse posits that AI has the potential to automate repetitive work, freeing up human attention for more creative endeavors. However, the rise of Creative AI is blurring traditional automation boundaries. [

4] outlines three different uses for Creative AI: (1) Comprehension (since creative processes require some level of comprehension), (2) Representation (using artificial intelligence to fill in the gaps in existing datasets), and (3) Generation (including text-to-image synthesis and visual transformation to create original outputs). In essence, by integrating (generative) AI tools, systems, and agents, Human-AI Co-Creativity has the potential to significantly improve human creative powers beyond what is now typical for (non-enhanced) human creativity.

This paradigm change necessitates a more thorough comprehension of these co-creative relationships, related difficulties, and the prerequisites for augmenting AI[

5]. From the standpoint of information science, this change necessitates a reassessment of the ways in which information is exchanged, understood, and changed in a human-AI partnership. Whereas the AI needs precise, low-level information inputs (prompts, parameters), the human gives ambiguous, high-level information needs (vision, intent, style). Many collaboration failures stem from this basic mismatch in information behavior. In order to enable the intricate information connections that define creative labor, including exploration, reflection, and serendipitous discovery, this study contends that effective co-creative systems must be built as information-rich environments that can translate over this gap. Our suggested paradoxes offer a foundation for creating more flexible and generative systems as well as a vocabulary for identifying these informational failures. Collaboratively, improving human creative performances is possible through the integration of generative AI tools into creative processes. These technologies can assist in overcoming the drawbacks of conventional approaches and expanding the realm of what is creatively feasible by emphasizing the enhancement of human creativity rather than its replacement[

6].

1.1. Shift From AI as a tool to as a Collaborator:

Collaboration between humans and creative systems is crucial because it boosts creativity, introduces new viewpoints, promotes continuous learning, and solves complex issues. In order for a system to be deemed autonomously creative, it must be capable of creative behavior, such as coming up with original concepts or solutions on its own without assistance from humans[

7]. This raises the question of whether generative AI tools are inherently creative. The foundation of this type of creativity is machine learning, which gives algorithms the ability to learn, adapt, and react in ways that can be considered "intelligent"—and hence, potentially creative[

8]. But the argument over whether technical systems are truly creative goes beyond science and turns into a philosophical discussion about appearing vs being. This discussion centers on the possible drawbacks of generative AI. According to perspectives, AI's dependence on pre-existing data would limit it to exhibiting "incremental creativity," raising doubts about the breadth and genuineness of its creative output[

9,

10]. within non-academic discourse, posits that genuine creativity is an exclusive domain of humankind, contingent upon our singular ability to experience profound emotions and exercise empathy[

11].

Throughout the creative process, humans employ a wide variety of creative techniques and thought processes, and concepts and the final product evolve dynamically over time. The agent must be flexible in order to keep up with this constant flow of ideas. Furthermore, it isn't always explicit about the role and interactions of the co-creative AI throughout the co-creation process. For instance, the human may want to take the lead and let the AI aid with certain duties. At other times, the human may want the AI to take the lead in order to generate ideas or work autonomously. In the relatively new topic of human-computer co-creativity, there are still many unanswered concerns regarding the mechanics of co-creation[

12]. Numerous generative design methods currently in use are inadequate in taking human variables into account, which restricts their capacity to take into account the entire range of human skills and limitations, and affective reactions that must be taken into account in order to advance true human-centered product and service innovation[

13]. Critical issues like role ambiguity, cognitive overload, authorship, uncertainty about outcomes and control conflicts between users and AI agents have also been found by recent studies[

14,

15,

16].

According to the section, generative AI is bringing about a revolutionary new era known as "Human-AI Co-Creation," in which AI ceases to be a passive instrument and instead becomes an active, cooperative partner. The goal of this collaboration is to generate collective creativity that is superior than what either AI or humans could do on their own. We believe that although AI can improve human creativity and automate activities, its development blurs conventional lines and calls for a better comprehension of co-creative dynamics. The main issue noted is that present AI tools frequently act as linear "executors" of commands, which is in opposition to human creativity's non-linear, iterative, and ambiguous nature. Because of the significant shortcomings caused by this mismatch, based on studies[

6,

12,

17,

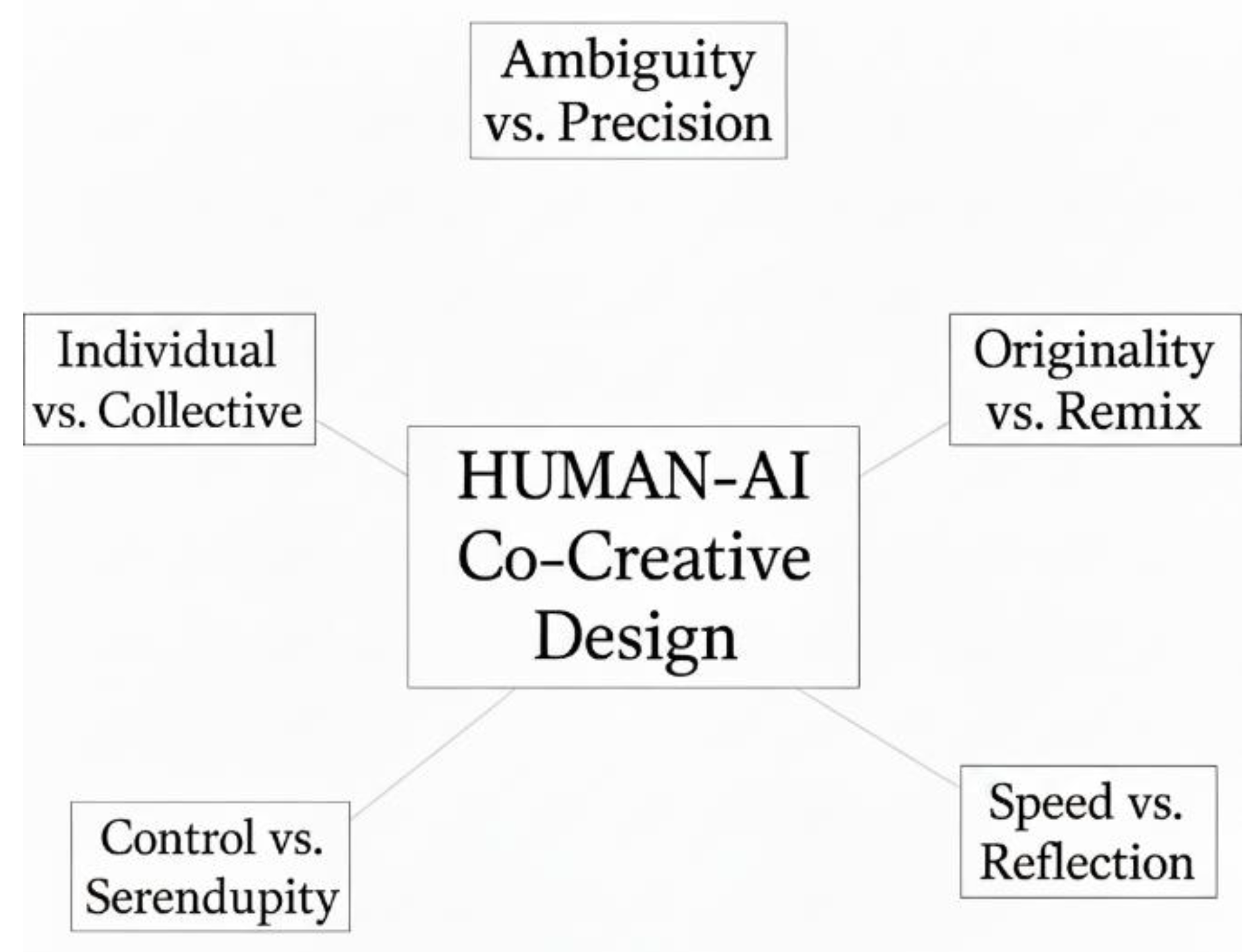

18] we propose five irreducible paradoxes—originality vs. remix, speed vs. reflection, control vs. serendipity, and ambiguity vs. precision—fundamentally shape the design space for human-AI co-creative systems. We suggest that these paradoxes offer a critical lens through which to examine current systems and produce fresh design frameworks, and that they are not issues to be resolved but rather necessary conflicts to be handled.

2. Related Work:

Creativity is an essential component of graphic design, allowing designs to differentiate themselves from competition and engage consumers' attention[

19]. Critical issues such role ambiguity, cognitive overload, and control conflicts between users and AI agents have been found by recent studies. As AI technology develops quickly, a variety of generative design tools have surfaced to help in the process of creative design[

18]. These technologies can interact with users and maximize design outcomes in response to textual instructions. However, because they are unaware of the natural cooperation process in creative design, they could have a bad user experience[

20].

Since both humans and computers take the initiative in the creative process and collaborate as co-creators, the idea of co-creative systems was born, merging standalone generating systems with tools to support creativity[

21]. The creative process in a co-creative system is complex and emergent due to the interaction between the AI agent and the human. According to a study, creativity that results from human-computer interaction cannot be attributed only to either party and outweighs the initial goals of both parties because new ideas are generated during the encounter[

22]. Researching human creative collaboration can serve as a solid foundation for exploring issues related to modeling an efficient interaction design for co-creative systems[

23]. According to author methods to lay the groundwork for the creation of computer-based systems that can support or improve collaborative creativity can be developed by comprehending the elements of human collaborative creativity[

24].

The ramifications of generative AI have started to be examined in recent information science work. A study[

5] argue that 'getting humans back in the loop' is necessary to ensure human agency in socio-technical systems by framing AI engagement via the lens of affordances. It is consistent with our criticism of AI's passive 'executor' position, which allows only a limited range of information sharing. Additionally, studies on information interaction using generative models reveal that prompt engineering is a major information retrieval difficulty for users[

25]. It can hinder creativity for users to have to learn how to translate their internal information needs into a syntactic format that the AI can grasp. This informational friction is directly addressed in our work on the Ambiguity vs. Precision conundrum. Our paradoxes offer a higher-level conceptual framework that explains why interaction patterns are tense, providing a complementary lens anchored in the fundamental informational conflicts of co-creation, even though models such as COFI[

12] are excellent at modeling such patterns.

In order to address gaps researchers faced during Human-Ai Collaboration severals

insufficiencies that must address to cover up this gap are presented in this literature, essentially, the very behaviors that give design its unique character are actively hampered by AI's linear workflow. The user is compelled to behave as an exact "command coder" instead of an adventurous "creative partner”. Instead than using their imagination, the user expends mental energy creating the ideal prompt. AI agents in well-known programs like Copilot[

26] and Midjourney[

27] require exact instructions and do not make it easier to mashup different possibilities. Until they get outcomes that are largely satisfying, designers frequently rework their prompts and regenerate images.

2.1. Linearity of AI Tools:

The creative process becomes a non-linear, iterative loop when prompts can be manually refined and hybridized. But in the end, the AI's training data and algorithms limit this non-linearity. When contrasted with the infinite, associative, and frequently intuitive non-linearity of human creativity itself, this basic limitation emphasizes the inadequacy of the AI tool's non-linearity is. The natural nonlinear transit between creative design stages [

28,

29,

30,

31] which entails taking inspiration from multiple simultaneous iterations and sometimes changing initial concepts along the way [

32], is hampered by such a turn-based linear approach. Because of their need for exact commands and limited operations on results, current AI-assisted tools consequently disregard the design requirements. The user must be allowed to exit this loop, create a new command, and resume the process in order to solve this issue. This will result in a workflow that is sequential and incremental by nature. Every stage is a separate, distinct transaction, that is property of non-linearity which entails divergent thinking, emergence and iteration and revision as well. Although a research[

18] tried to cover this gap by introducing a novel framework but result in time consuming. To overcome linearity, an AI system should, with each iteration, automatically produce several qualitatively different variations rather than just one output per command. As a result, the user interface (UI) for a creative system needs to be created so that various "operational strategies"—the AI describing how it understood the prompt to produce the output—can be used. The user may quickly visualize a "design space" thanks to this, which facilitates the non-linear thought leaping that is essential to innovation. Creating a prototype initially is a better way to understand this. A continuous dialogue interface that allows the user to engage with the outputs without having to start over must be integrated into the user interface.

2.2. Lack of Support for Refinement

Despite flexibility of AI, human responses are always rated as more creative than AI. Flexibility means having a lot of different thoughts or ways to solve a problem[

33]. On the other side AI demonstrates its inability to truly handle ambiguity in a human-like way. There are may several reasons for this like tools demand precise and accurate information while the input provided to these tools are vague, unclear words, which leads towards failure, which is counted as another

insufficiency of lack of support for refinement. Modern chatbots like ChatGPT have achieved human-level creativity, surpassing average human responders in psychological tasks like the Ambiguous task [

11,

34] or the Torrance test[

35], according to recent research comparing AI and human creative outputs. All of these research have demonstrated, meanwhile, that even the most advanced AI systems cannot match the performance of the best human performers.

These research' use of somewhat antiquated creativity tests, for which a sizable amount of information and examples are available online, is one of their limitations. It's possible that these items served as training data for the chatbot, which would subsequently re-pose when given the assignment. In this scenario, the chatbots' creative output would be a memory output from the stored training data rather than representing actual creative behaviors. A study[

36], evaluate AI against human performance, The study highlights that mental imagery, a sensory-based cognitive process where people imagine and manipulate information, is probably involved in tasks like the FIQ. According to the authors, "human creativity draws from a diverse range of subjective experiences and sensory-driven cognitive processes." AI lacks sensory perception. It can only determine what an abstract shape most likely symbolizes based on text it has processed; it cannot "imagine" what it feels like or what it evokes. Its inability to successfully negotiate the task's ambiguity in a way that appeals to human judges as genuinely innovative is due to this fundamental mismatch.

The notion[

37] that "all users demand identical creative outputs" is a direct cirtique of the tools. Ambiguity is frequently cleared up by context, which varies depending on the individual and the endeavor. An AI will always be forced to interpret ambiguous commands from scratch, producing generic or unsuccessful results, if it is unable to acquire the distinct style, preferences, and project history of a user or a team. This is one of the main causes of the "lack of support for refinement." A critical design principle is that effective human-AI interaction (HAII) in creative systems necessitates the mitigation of known collaborative challenges. Furthermore, a significant gap in the design of many creative AI tools is the general failure to account for collaborative workflows altogether.

2.3. Single Output/Multiple Exploration:

The tendency of many AI systems to focus on producing a single, optimal output rather than enabling a thorough exploration of the design space is a major barrier to successful human-AI co-creation. The human designer's function as an idea curator may be compromised by this single-output emphasis, which can also prematurely merge creative processes and inhibit uniqueness[

38]. Future AI systems must be specifically built as exploration engines rather than solution generators in order to overcome this constraint. This can be accomplished via a number of crucial tactics:

In order to help the early "Discover" and "Define" phases of the design process, where problem-framing and ideation are crucial, AI development must first change. Since the later phases of development and delivery[

39] are mostly the focus of current AI-DSS technologies, convergence is naturally preferred over divergence. Early-stage tools would focus on producing a broad range of thoughts, metaphors, and linkages in order to broaden the solution space before focusing on narrowing it. Second, it is crucial to include AI into iterative, non-linear workflows. Creative exploration rarely follows a straight route; instead, it necessitates concept branching, recombination, and backtracking. This fluidity should be supported by AI systems, which would enable designers to effortlessly save, revisit, and combine several lines of inquiry[

40,

41]. This method fits nicely with the organic flow of creative activity, in which preliminary concepts are improved via iterative reflection and feedback.

Third, designers might escape cognitive fixedness by utilizing AI for serendipity and associative thinking. AI should be entrusted with using its extensive training data to provide lateral variations, stylistic opposites, or surprising pairings rather than aiming for the best answer. Layered and progressive prompting can produce rich and varied visual outputs, transforming the AI into a collaborator for chance discovery, as demonstrated in research on AI-assisted design education [

42]. Importantly, the user must have clear control over the exploration through the design of the interface and interaction. Systems should give designers user-friendly controls, like sliders for originality, randomness, style influence, and constraint adherence, to stop AI from taking over the creative[

43] direction. In order to allow the designer to evaluate, compare, and curate the ideas produced, the findings should also be displayed as a multifaceted collection of possibilities rather than as a single output, such as in galleries or plotted onto a graph of trade-offs. This strengthens the designers' ultimate authorship over the finished work and gives them the ability to use their creative agency.

By putting these approaches into practice, we may move away from AI systems that automate design decisions and toward ones that enhance human creativity, making sure that AI serves as a lens for human imagination rather than a framework that limits it.

2.4. AI's Limited Role as an Executor

According to the Executor role, AI is a strong but passive instrument for executing commands rather than an active collaborator in the creative process as defined by[

18] for an AI tool Copilot” Copilot provides users with an optimal output to their commands without explaining how it is inferred from the user's instructions”. To understand this deficiency we must consider one thing that this technique fundamentally conflicts with the inherent character of creative design, introducing several key problems, like Restriction of exploratory ideas and divergent thinking. Executor AI systems prematurely converge the design space by producing a single output for each command. This feature directly contradicts a fundamental aspect of creativity: the production and exploration of diverse ideas. In contrast to human collaborators who supply "alternative solutions as sources of inspiration,"[

18] an executor AI does not offer divergent thinking. This flaw lowers the design process to a lengthy and inefficient trial-and-error loop, frequently resulting in user irritation and abandoned tasks when the AI continuously fails to understand the user's purpose.

AI-powered technologies like ChatGPT, Midjourney, and Autodesk Dreamcatcher promote iterative, non-linear collaboration, combining human intuition and AI-generated insights[

15,

44]. These tools In fact, typically nonetheless serve as executors in practice because they require precision, hinder natural processes, and focus on single outputs. The executor mode lays the full responsibility for translation and precision on the human creator. Users are compelled to break down their high-level, often ambiguous creative intents into low-level, executable instructions—a task that necessitates significant effort and domain-specific knowledge. The fact is executors sometimes fail when meet vague language when used with creative ideation, it could be reduce by paraphrasing the user's commands or by creating a communication layer that enables humans and AI to comprehend one another.

A significant body of research outlines human collaboration patterns, emphasizing the value of aligning requirements and fostering creative idea synthesis. However, a key issue in the development of successful co-creative systems is the basic question of how requirement alignment and remixing between human and artificial agents can be efficiently enabled. This issue is still open and complicated.

While prior work [

6,

12,

17,

18]

identifies isolated challenges in Human-AI collaboration we argue these form a system of paradoxes unique to co-creative domains, where AI must balance competing demands without stifling human ingenuity. We suggest that these paradoxes offer a critical lens through which to examine current systems and produce innovative design frameworks, and that they are not issues to be resolved but rather necessary conflicts to be handled. Moreover, these will provide a valuable analytical lens for critiquing existing systems and a generative framework for guiding future design.

Presented work highlights significant shortcomings in the state of AI technologies in creative creation. It makes the case that widely used programs like Copilot and Midjourney, which function as "executors" that need exact instructions and generate single outputs, impose a linear workflow. The inherent non-linearity of human creativity—which flourishes on variation, iteration, and exploration—is hampered by this structure. These technologies also don't support refinement, struggle with the imprecise terminology that comes with early creative thought, and don't pick up on a user's distinct style. The emphasis on a single ideal result is a serious drawback since it stifles chance discovery and prematurely converges the design space. In the synthesis of these criticisms, we contend that previous studies have addressed these issues separately, but that they actually constitute a network of paradoxes that need to be handled collaboratively when designing co-creative systems.

3. Core Paradoxes in Human AI Co-Creative Design

We define these conflicts as five irreducible paradoxes that are essential to the design space of human-AI co-creative systems: originality vs. remix, speed vs. reflection, control vs. serendipity, ambiguity vs. accuracy, and individual vs. collective

Figure 1.

3.1. Ambiguity vs. Precision

Advanced generative AI systems like GPT-4 are being adopted at a rapid pace, revolutionizing human-technology interaction by enabling conversational, intuitive problem-solving using natural language across a variety of applications[

45]. Since AI models trained on vast amount of data, designed to provide best with precise outputs, on the other side human input may contain ambiguous or emotive language which leads to the question Without limiting initial creative exploration, how can we create interfaces that serve as "ambiguity translators," assisting users in gradually refining vague intentions into prompts?

There is a fundamental mismatch where users struggle to translate their vision into executable commands, leading to frustration because Human creative thought is inherently ambiguous, expressed through abstract concepts and subjective language, on the other side AI systems require precision and explicit parameters to function predictably. Here ambiguity translators does not mean to design an input box but to design designing interaction loops. The answer will not provided in just single output rather will be design for multi-turn like in[

42], integration of artificial intelligence (AI), more especially text-to-image (T2I) generators like Midjourney, into the conceptual design stage of interior design education was investigated. Results show that AI-assisted visualization improved conceptual precision, sped up design iteration, and improved ideation. A fundamental question is introduced by this possibility[

6]: where do we draw the boundary between creativity and human-AI systems? Determining the source of creativity—is it the human, the AI, or the cooperation itself—is the main challenge. This unresolved question critically shapes how we evaluate creative outputs, forcing a choice between viewing AI as a mere tool or as a genuine creative partner. The same fundamental contradiction is discussed in section 2.1: the conflict between the nature of present AI systems and human creativity and presents this conflict from the perspective of linearity vs non-linearity.

From HCI design perspective, creating interfaces that acts as a ambiguity translators based on guidance rich content, it may involve iterations in order to achieve precision. For instance, instead of locking user into single output asking or offering structure or presenting more suitable information could be more helpful. Moreover, this will enhance user experience describing relevant content into manageable chunk, like by asking more relevant questions to the user. Second, role based approach By incorporating a diverse and fluid spectrum of roles—from supportive tools to active co-creators, will ensures that precision does not become a restriction. It deliberately retains a degree of role ambiguity, which is proved to be required for creative potential, allowing the collaboration to evolve and emergent roles to form.

3.2. Control vs. Serendipity

The creative process has a contingency. There are numerous ways to achieve creative success—or failure—from the very beginning of a concept to its eventual adoption by the target audience. Serendipity is the paradoxical event in which an unexpected accident (chance) and a person's sagacity (skill) meet in an unexpected way to produce a new and worthwhile discovery. We argue that this is paradoxical since it necessitates the simultaneous presence of two seemingly incompatible elements: i) Lack of Control ii)Agency & Control. Discovery must commence with an unforeseen, unplanned incident that lies beyond the individual's direct control or intention. It is a disruption to the expected course of events[

46,

47]. To strike the agency and control the person must be knowledgeable, sensitive, and cognitively prepared (sagatic) enough to see the accident's potential and be able to use it expertly and purposefully to produce something original and worthwhile[

48].

Here, creativity arises from the tension between passively accepting chance and actively, skillfully manipulating it; it is neither completely accidental nor purely agential. Pure agency lacks the disruptive spark of the unexpected, whereas pure chance is passive and "blind," according to Ross. At the exact point where these two opposing forces converge, serendipity occurs[

49]. Serendipity is valuable if the user trusts the AI's intention. This locus of control can be determined by concluding, What is the optimal balance between AI-generated suggestions and user veto power? We argue that optimal balance is critical topic that crosses a technical specification and delves deeper into the concept of interaction design. The system does not aim for a flawless predetermined optimum.

Though sagacity levels are different, vary from person to person so it depends on cognitive state of user. The balance is a dynamic interaction intended to promote the circumstances rather than a static arrangement but to foster serendipity it might be possible thorugh several ways, by actively countering enhancement of algorithms[

50], and another key point is to control repetition, preventing the system from providing the same core answer with only superficial changes in vocabulary. Another way is to support, not exploration[

51] as AI should be a catalyst that broadens the user's horizon, working as the digital counterpart of "visiting the library, going to the stacks, or going to the seemingly unrelated seminar." The ideal balance between AI-generated ideas and user veto power is one that deliberately places veto authority as the critical manifestation of the prepared mind required for serendipitous discovery[

51]. Furthermore, vetoing serves as an active reasoning process that strengthens the user's role in abductive thinking, which is crucial for serendipity. It facilitates the synchronization of prior information with apparent anomalies[

52]. This cognitive curation is crucial for spotting valuable deviations; by discarding irrelevant suggestions, the user frees attentional space to recognize and use unexpected insights that may otherwise be overlooked in a stream of homogenized recommendations. The conflict between AI-proposed options and human veto power creates a dynamic in which algorithmic breadth is balanced by expert discernment, fostering settings conducive to unique and meaningful discovery.

3.3. Speed vs. Reflection

AI is not affected by physiological factors like fatigue [

53], but humans are expected to invent continually and quickly on a huge scale. AI's speed sets a hard bar for human creators, but it also reduces the training requirements for artists and creatives. AI's ability to learn from human creations sets a higher standard for innovation. The objective is not to slow down AI for its own sake, but rather to intentionally foster human judgment, contextualization, and intentionality. The importance of speed is based on theories of divergent thinking and brainstorming, in which postponing judgment and creating a large number of ideas is an important stage in the creative process. In human-AI co-creative design, reflection[

54] denotes the metacognitive process of critical thought, evaluation, and integration. The tension arises when AI systems accelerate processes for instance, text generation, but this acceleration unintentionally limits time available for human reflective skills such as critical thinking, contextual interpretation, and creative intent. This creates a contradiction between efficiency and depth of comprehension.

Several studies tried to overcome this paradox, for instance, paradox is most clearly discussed in the Radiology use case, where AI speeds up the diagnosis process - this is viewed as an issue of increasing productivity while integrating AI - but it may unintentionally reduce the time for creative intent, which cannot develop sufficiently in high-speed settings because the load for individual reflection decreases with the number of images to be reflected in a time unit[

55]. We state that using AI for speed may accidentally weaken the reflective techniques that make human specialists competent and capable of dealing with novel situations in the long term. Here, the "speed" path is alluring. It provides instant advantages in productivity and efficiency. However, it risks producing a generation of professionals who are increasingly reliant on AI outputs, and whose critical thinking abilities may deteriorate due to lack of use—a phenomenon known as deskilling[

56]. Another study[

57] proposed that this conflict can be resolved not by selecting between speed and reflection, but by purposefully creating AI systems to encourage reflection, so making human professionals more effective rather than just faster. Future co-creative systems must be purposefully built with strategic "pause points" or "friction" that encourage critical review and incorporation of AI-generated content in order to reconcile the conflict between speed and contemplation. In order to ensure that AI's speed enriches rather than diminishes the depth of human creative cognition, interfaces that promote annotation of outputs, comparative analysis of many possibilities, and required reflection prompts can be included.

3.4. Individual vs. Collective

The paradox is profound and nuanced, and it gets to the core of the growing interaction between humans and AI. When a single human creator (the Individual) collaborates with an artificial intelligence that is, by definition, an embodiment of a Collective—trained on aggregated data, patterns, and outputs from large swathes of human culture and knowledge—a fundamental tension occurs. Here we define two sides of this paradox one of them is human(individual) with the goal of uniqueness, coherent creative vision. Other side is AI model(collaborative) involving generic human or wisdom of all data. Manifest of paradox here is when output of collective misalign with the vision of individual. For instance, AI-powered design tools like Copilot & Midjourney often follow a linear sequence of exact instructions to approximate design objectives. These procedures contravene creative design guidelines, limiting AI agents' ability to accomplish creative tasks[

18]. This tension raises crucial research questions; How do designers and AIs settle creative disputes and which interface features work best for negotiating a common course? These inquiries are the paradox's practical expressions, looking for ways to address the discrepancy between individual intentions and group production. A study[

58] demonstrates how AI influences human narrative, pointing to a type of implicit negotiation in which people integrate AI-generated concepts into their own original work. Assimilation and compromise are ways of "settling" creative disputes. Additionally, the study demonstrates that hybrid human-AI networks attained the greatest diversity over time, indicating that creative synergy can still result from straightforward, anonymous, iterative collaboration (without formal negotiation interfaces). This suggests that minimally controlled interactions can help humans and AIs negotiate their creative differences. According to a different study[

59], complementing cooperation rather than overt bargaining is how creative "disputes" are settled. While AI delivers size, pattern recognition, and quick generation, humans give context, intentionality, and moral judgment. Both can contribute their strengths thanks to this synergy without one taking over the other, On the other hand, the study also supports open-ended, adaptable technologies that let humans direct the creative process while utilizing AI's capacity to produce concepts and variations. The ideal "interface" is one that lets AI manage extensive pattern synthesis while still permitting human oversight and contextual input.

We might draw the conclusion that a conflict is inevitable when a single creator interacts with this collective reflection. Because it is based on probability, the AI will go toward the traditional, the cliché, the visually "safe" choice that fits the data it was trained on. This paradox can be resolved by changing people's perspectives and abilities: i) The New Creative Skill: Beyond mere creation, the most valuable skill is now creative direction. It's the capacity to create a vision, communicate it to the AI in a form that it can comprehend, and then carefully select the results. By directing the orchestra of collective intelligence to play their own symphony, the artist transforms into a conductor. ii) Reframing the Collective: The communal aspect of AI might be viewed as the ultimate source of inspiration rather than as a danger to individualism. It allows one individual to access the collective styles of all the writers, designers, and artists on which it was trained. Remixing, honing, and concentrating this collective chaos into a fresh, cohesive whole that is uniquely theirs is where the individual's brilliance resides.

3.5. Originality vs. Remix

AI systems may generate unique material using data and algorithms, a concept known as originality. This notion evaluates the parallels and differences between AI and human creativity, taking into account both technical and ethical considerations. AI-generated material is considered original based on its unique methodologies, data sets, and results[

60]. On the other side, theory of remix defined by[

61] "Copy, transform, and combine" is a recursive algorithm for making new works from existing resources”. The paradox is that this very ability—to quickly remix and regenerate content—enables both extraordinary production and a troubling erosion of creative variation.

We argue that generative AI embodies the remix concept. It works by quantitatively evaluating a large collection of human inventions (the ultimate remix source material) and identifying patterns, styles, and relationships within it. Its output is a recombination of these previously learnt patterns; it is the result of an extreme algorithmic remix. While on the other hand, the output of AI appears to meet the criterion for originality. It can create a new image, text, or design that did not previously exist in that exact form. It can result in work that is unique (new) and frequently worthwhile. To a human observer, the outcome can appear unique, unexpected, and inventive. This creates irreconcileable tension from both remix and originality perspectives. It pulls us in two directions at once, exposing weaknesses and limitations in our long-held conception of uniqueness and creativity. According to findings from a study[

62] AI can help to promote and deepen design originality, but it may be restricted in its ability to generate creativity itself. When paired with human ingenuity, AI improves design processes by providing both efficiency and originality. This suggests that value is not in the AI-generated remix, but in the human's capacity to control, pick from, and infuse it with personal vision and context. The AI handles the computationally demanding "remix" (variation generation), whereas the human gives the "original" artistic direction.

The process of generative AI significantly questions the underlying concepts of originality and remix. According to Gunkel [

63]the system works by processing statistical data rather than sampling content, converting cultural objects into mathematical embeddings that describe hidden patterns. This ontological shift implies that using the binary of "original" (a privileged source) and "remix" (a derivative copy) is a fundamental misapplication of categories.

4. Discussion

This study contributes a novel conceptual framework for information science to critically analyze human-AI co-creation. A new viewpoint on informational breakdowns in creative systems is offered by the five paradoxes: Ambiguity vs. Precision, Control vs. Serendipity, Speed vs. Reflection, Individual vs. Collective, and Originality vs. Remix. They express the basic tensions that define user information behavior and AI system information provisioning within a cooperative dyad, going beyond just defining interaction patterns. This paper makes the case for a paradigm change away from the simplistic idea of AI as a tool and toward an active, communicative partner. The approach does a good job of showing that incorporating generative AI into creative workflows is a fundamental shift rather than a piecemeal one. This change calls for a reexamination of traditional HCI paradigms, which frequently place a higher value on efficiency and accuracy than on the ambiguity, inquiry, and serendipity that are essential to human creativity. A turn-based, linear interaction model frequently predominates, as demonstrated by systems such as Copilot[

26] and Midjourney[

27], which reduces the person to a "command coder" instead of a "creative partner." The non-linear, iterative, and emergent aspects of true creative cooperation are suppressed by this structure [

28,

29,

31].

The main contribution of the work is the formulation of these five irreconcilable paradoxes. They are presented as necessary conflicts to be managed in the design of co-creative systems rather than as issues to be resolved. This paradigm provides a creative basis for creating new tools as well as a powerful analytical lens for evaluating current ones. The Ambiguity vs. Precision conundrum, for example, draws attention to a fundamental inconsistency: human creative cognition is abstract and subjective, yet artificial intelligence (AI) needs specific criteria to operate. Creating interfaces that function as "ambiguity translators" through iterative, multi-turn discourse is a viable remedy[

42].

Similarly, the delicate balance necessary for fruitful collaboration is encapsulated in the Control vs. Serendipity conundrum. It reinterprets the user's "veto power" as an active, advantageous part of "abductive thinking" and cognitive curation [

51,

52], which are crucial for chance discovery, rather than as an AI failure. The Originality vs. Remix conundrum is especially important since it calls into question basic ideas about authorship and creativity. According to this paper, the ultimate remix engine is generative AI, which operates on statistical patterns in large amounts of training data [

61]. However, its results can seem new and different. As a result, the human's ability to provide creative guidance—curating, improving, and adding context and personal perspective to the AI's output—becomes more useful than the AI's inherent generative ability [

62]. This suggests that mastery of creative direction and curation, rather than mastery of a medium, may be the most important talent for aspiring producers. The description of the Executor position [

18] brings up a significant point: AI frequently generates results that are not explicable. One important tactic for resolving a number of paradoxes is the application of Explainable AI (XAI) concepts. One way to close the ambiguity-precision gap and give users more agency would be to disclose the "operational strategies" an AI employed to interpret a prompt.

Theoretical Implications: By framing the difficulties of human-AI co-creation as a system of basic, constructive paradoxes, this study represents a substantial conceptual breakthrough. It moves the emphasis of study away from technical expertise and toward the subtleties of interaction design, cognitive cooperation, and the essence of creativity itself. The framework enhances theories in information science and HCI by offering a novel vocabulary and a critical perspective for examining the informational dynamics and underlying conflicts in co-creative dyads.

Practical Implication: For designers and developers, the main practical implication is a clear directive: stop attempting to eliminate these tensions and begin creating systems that dynamically manage them. The design of next-generation co-creative applications can be guided by the generative framework provided by the paradoxes. For instance, designers can use serendipity sliders for Control, multi-turn refinement loops for Ambiguity, reflective prompts for Speed, and curation interfaces that show a range of options for Individual vs. Collective and Originality. In order to ensure that AI serves as a "lens for human imagination" rather than a cage for it, the ultimate goal is to establish a cooperative partnership where humans and AI complement each other's strengths and make up for each other's shortcomings.

Future work and limitations: While this paper presents a conceptual framework derived from a synthesis of existing literature, its primary limitation is its theoretical nature. Despite being based on recognized flaws in existing systems, the suggested paradoxes need empirical support to evaluate their applicability and influence on co-creative system design. Operationalizing this approach to carry out controlled user research is our urgent next task. For example, by including tools for multi-turn refining (Ambiguity vs. Precision), serendipity sliders (Control vs. Serendipity), and reflective prompts (Speed vs. Reflection), we intend to create prototype co-creative interfaces that are specifically made to handle each contradiction. These prototypes will be assessed in tasks involving visual design or conceptual ideation using standard "executor"-model tools.

Conclusions: We present the field of information science a crucial tool to help direct the development of future co-creative information systems that are not only more potent but also more intuitive, helpful, and ultimately more human by presenting these difficulties as irreducible paradoxes. The future of creative design, according to this article, lies in rethinking AI as an active, opinionated collaborator rather than in perfecting it as a tool. We have defined the fundamental issues as five irreducible paradoxes, by combining criticisms of the current linear "executor" systems. The fundamental design area for co-creation between humans and AI is defined by these tensions. We suggest that instead of trying to solve these paradoxes, the goal should be to create systems that can manage them dynamically while promoting a cooperative relationship. The ultimate objective is to enhance human creativity by making sure AI serves as an inspiration rather than a limitation, enabling people to continue being the deliberate, creative leaders at the center of the process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, Z.S. and R.H.-N.; methodology, Z.S. and R.H.-N.; validation, Z.S. and R.H.-N.; formal analysis, Z.S., R.H.-N. and C.P.; investigation, Z.S. and R.H.-N.; resources, Z.S., R.H.-N. and C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.S.; writing—review and editing, Z.S., R.H.-N.; visualisation, R.H.-N. and Z.S.; supervision, R.H.-N. and C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by research grants PID2022-137849OB-I00 funded by MI CIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the ERDF, EU.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Serbanescu, A.; Nack, F. Human-AI system co-creativity for building narrative worlds. IASDR 2023: Life-Changing Design. [CrossRef]

- Gu, N.; Behbahani, P.A. A Critical Review of Computational Creativity in Built Environment Design. Buildings 2021, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, R.K.; DeZutter, S. Distributed creativity: How collective creations emerge from collaboration. Psychol. Aesthetics, Creativity, Arts 2009, 3, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, K. You never fake alone. Creative AI in action. Information, Commun. Soc. 2020, 23, 2110–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, N.P.; Robert, L.; Xiao, X. Putting humans back in the loop: An affordance conceptualization of the 4th industrial revolution. Inf. Syst. J. 2022, 33, 733–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, J.; Pokutta, S. Human-AI Co-Creativity: Exploring Synergies Across Levels of Creative Collaboration. arXiv arXiv:2411.12527, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, K.E. Developing Creativity: Artificial Barriers in Artificial Intelligence. Minds Mach. 2010, 20, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateja, D.N.; Heinzl, A. Towards Machine Learning as an Enabler of Computational Creativity. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2021, 2, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, M.A. Computer Models of Creativity. AI Mag. 2009, 30, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropley, D.; Cropley, A. Creativity and the Cyber Shock: The Ultimate Paradox. J. Creative Behav. 2023, 57, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, J.; Hanel, P.H. Artificial muses: Generative artificial intelligence chatbots have risen to human-level creativity. J. Creativity 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezwana, J.; Maher, M.L. Designing Creative AI Partners with COFI: A Framework for Modeling Interaction in Human-AI Co-Creative Systems. ACM Trans. Comput. Interact. 2023, 30, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, H.O.; Goldstein, M.H.; Li, X.; Sha, Z. Human-Centered Generative Design Framework: An Early Design Framework to Support Concept Creation and Evaluation. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 2023, 40, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, E.K.; Lee, J.D. Trusting Automation: Designing for Responsivity and Resilience. Hum. Factors: J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2021, 65, 137–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, V.; Liao, Q.V.; Vaughan, J.W.; Bansal, G. Understanding the Role of Human Intuition on Reliance in Human-AI Decision-Making with Explanations. Proc. ACM Human-Computer Interact. 2023, 7, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmeiner, F.; Yang, H.; Yao, L.; Holstein, K.; Martelaro, N. Exploring Challenges and Opportunities to Support Designers in Learning to Co-create with AI-based Manufacturing Design Tools’, in Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, in CHI ’23. New York, NY, Apr. 2023, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; pp. 1–20. [CrossRef]

- C. Moruzzi and S. Margarido, ‘A User-centered Framework for Human-AI Co-creativity’, in Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, in CHI EA ’24. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, May 2024, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; et al. Understanding Nonlinear Collaboration between Human and AI Agents: A Co-design Framework for Creative Design. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.07312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, D.; Correia, J.; Machado, P., ‘EvoDesigner: Towards Aiding Creativity in Graphic Design’, in Artificial Intelligence in Music, Sound, Art and Design, T. Martins, N. Rodríguez-Fernández, and S. M. Rebelo, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 162–178. [CrossRef]

- Frich, J.; Vermeulen, L.M.; Remy, C.; Biskjaer, M.M.; Dalsgaard, P. , ‘Mapping the Landscape of Creativity Support Tools in HCI’, in Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, in CHI ’19. New York, NY, May 2019, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; pp. 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Kantosalo, A.; Jordanous, A. , ‘Role-Based Perceptions of Computer Participants in Human-Computer Co-Creativity’, presented at the 7th Computational Creativity Symposium at AISB 2021, London, UK: AISB, 2021, pp. 20–26. Accessed: Aug. 26, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://aisb.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/cc_aisb_proc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Liapis, A.; Yannakakis, G.N.; Togelius, J., ‘Computational game creativity’, Jun. 2014, Accessed: Aug. 26, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/29473.

- Davis, N.; Hsiao, C.-P.; Popova, Y.; Magerko, B., ‘An Enactive Model of Creativity for Computational Collaboration and Co-creation’, in Creativity in the Digital Age, N. Zagalo and P. Branco, Eds., London: Springer, 2015, pp. 109–133. [CrossRef]

- Mamykina, L.; Candy, L.; Edmonds, E. Collaborative creativity. Commun. ACM 2002, 45, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj-Bolouri, A.; University West; Conboy, K. ; University of Galway; Gregor, S.; Australian National University Research Perspectives: An Encompassing Framework for Conceptualizing Space in Information Systems: Philosophical Perspectives, Themes, and Concepts. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2024, 25, 407–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Stallbaumer, ‘Introducing Copilot for Microsoft 365’, Microsoft 365 Blog. Accessed: Aug. 26, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/blog/2023/03/16/introducing-microsoft-365-copilot-a-whole-new-way-to-work/.

- Tan, L.; Luhrs, M. Using Generative AI Midjourney to enhance divergent and convergent thinking in an architect’s creative design process. Des. J. 2024, 27, 677–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. S. Gero, ‘Design Prototypes: A Knowledge Representation Schema for Design’, AI Magazine, vol. 11, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Dec. 1990. [CrossRef]

- Gero, J.S.; Kannengiesser, U. The situated function–behaviour–structure framework. Des. Stud. 2004, 25, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Hatchuel and B. Weil, ‘A NEW APPROACH OF INNOVATIVE DESIGN : AN INTRODUCTION TO C-K THEORY.’, DS 31: Proceedings of ICED 03, the 14th International Conference on Engineering Design, Stockholm, pp. 109-110 (exec.summ.), full paper no. DS31_1794FPC, 2003.

- Howard, T.; Culley, S.; Dekoninck, E. Describing the creative design process by the integration of engineering design and cognitive psychology literature. Des. Stud. 2008, 29, 160–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girotto, V. Collective Creativity through a Micro-Tasks Crowdsourcing Approach’, in Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing Companion, in CSCW ’16 Companion. New York, NY, Feb. 2016, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; pp. 143–146. [CrossRef]

- E. Clement, Cognitive Flexibility: The Cornerstone of Learning. John Wiley & Sons, 2022.

- Koivisto, M.; Grassini, S. Best humans still outperform artificial intelligence in a creative divergent thinking task. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzik, E.E.; Byrge, C.; Gilde, C. The originality of machines: AI takes the Torrance Test. J. Creativity 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassini, S.; Koivisto, M. Artificial Creativity? Evaluating AI Against Human Performance in Creative Interpretation of Visual Stimuli. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. H.-C. Hwang, ‘Too Late to be Creative? AI-Empowered Tools in Creative Processes’, in CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Extended Abstracts, New Orleans LA USA: ACM, Apr. 2022, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- X. Guo, Y. Xiao, J. Wang, and T. Ji, ‘Rethinking designer agency: A case study of co-creation between designers and AI’, IASDR Conference Series, Oct. 2023, [Online]. Available: https://dl.designresearchsociety.org/iasdr/iasdr2023/fullpapers/170.

- Lee, S.-Y.; Law, M.; Hoffman, G. When and How to Use AI in the Design Process? Implications for Human-AI Design Collaboration. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 2024, 41, 1569–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltà-Salvador, R.; El-Madafri, I.; Brasó-Vives, E.; Peña, M. Empowering Engineering Students Through Artificial Intelligence (AI): Blended Human–AI Creative Ideation Processes With ChatGPT. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2025, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ege, D.N.; Øvrebø, H.H.; Stubberud, V.; Berg, M.F.; Steinert, M.; Vestad, H. Benchmarking AI design skills: insights from ChatGPT's participation in a prototyping hackathon. Proc. Des. Soc. 2024, 4, 1999–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadağ, D.; Ozar, B. A new frontier in design studio: AI and human collaboration in conceptual design. Front. Arch. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. D. Weisz, M. Muller, J. He, and S. Houde, ‘Toward General Design Principles for Generative AI Applications’, Jan. 13, 2023. arXiv:arXiv:2301.05578. [CrossRef]

- Z. Dehghani Champiri, ‘UX design & evaluation of healthQB: A mobile application to manage chronic pain’. Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://summit.sfu.ca/item/35168.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. , ‘BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding’, in Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), J. Burstein, C. Doran, and T. Solorio, Eds., Minneapolis, Jun. 2019, Minnesota: Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 4171–4186. [CrossRef]

- Ross, W. The possibilities of disruption: Serendipity, accidents and impasse driven search. Possib- Stud. Soc. 2023, 1, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, M.I.; Keane, M.T. The Role of Surprise in Learning: Different Surprising Outcomes Affect Memorability Differentially. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2018, 11, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, W.; Vallée-Tourangeau, F. Microserendipity in the Creative Process. J. Creative Behav. 2020, 55, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisberg, R.W. On the Usefulness of “Value” in the Definition of Creativity. Creativity Res. J. 2015, 27, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Finn, What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of Computing. MIT Press, 2017.

- LISETE BARLACH, ‘Serendipity: obstacles and facilitators’, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Fortes, G. ‘Abduction’, in The Palgrave Encyclopedia of the Possible, V. P. Glăveanu, Ed., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, K.; Payne, K. Strategy in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. J. Strat. Stud. 2015, 39, 793–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Быкoва, Е.А. Reflection as a Factor in the Success of Learners’ Innovative Activity. Lurian J. 2022, 3, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkens, U.; Field, A.E. Creative Intent and Reflective Practices for Reliable and Performative Human-AI Systems’, Schriftenreihe der Wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft für Arbeits- und Betriebsorganisation (WGAB), vol. 2023, pp. 77–94, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- Attewell, P. The Deskilling Controversy. Work. Occup. 1987, 14, 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Karim, B.M.; Pfeuffer, N.; Carl, K.V.; Hinz, O.; Goethe University Frankfurt am Main. How AI-Based Systems Can Induce Reflections: The Case of AI-Augmented Diagnostic Work. MIS Q. 2023, 47, 1395–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Shiiku, R. Marjieh, M. Anglada-Tort, and N. Jacoby, ‘The Dynamics of Collective Creativity in Human-AI Hybrid Societies. arXiv:2025 arXiv:2502.17962. [CrossRef]

- J. Linares-Pellicer, J. Izquierdo-Domenech, I. Ferri-Molla, and C. Aliaga-Torro, ‘We Are All Creators: Generative AI, Collective Knowledge, and the Path Towards Human-AI Synergy’. arXiv:arXiv:2504.07936. [CrossRef]

- S. Fan and M. Taylor, Will AI Replace Us? Thames and Hudson Ltd, 2019. Accessed: Sep. 10, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.perlego.com/book/1594627/will-ai-replace-us-pdf.

- D. J. Gunkel, ‘Generative AI and Remix: Difference and Repetition’, in The Routledge Companion to Remix Studies, 2nd ed., Routledge, 2025.

- Günay, M. Artificial Intelligence and Originality in Design. 2025, 4, 449–469. [CrossRef]

- L. Orozco, ‘Holly Herndon’, New Suns. Accessed: Sep. 10, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://newsuns.net/holly-herndon-spawning-identities/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).