1. Introduction

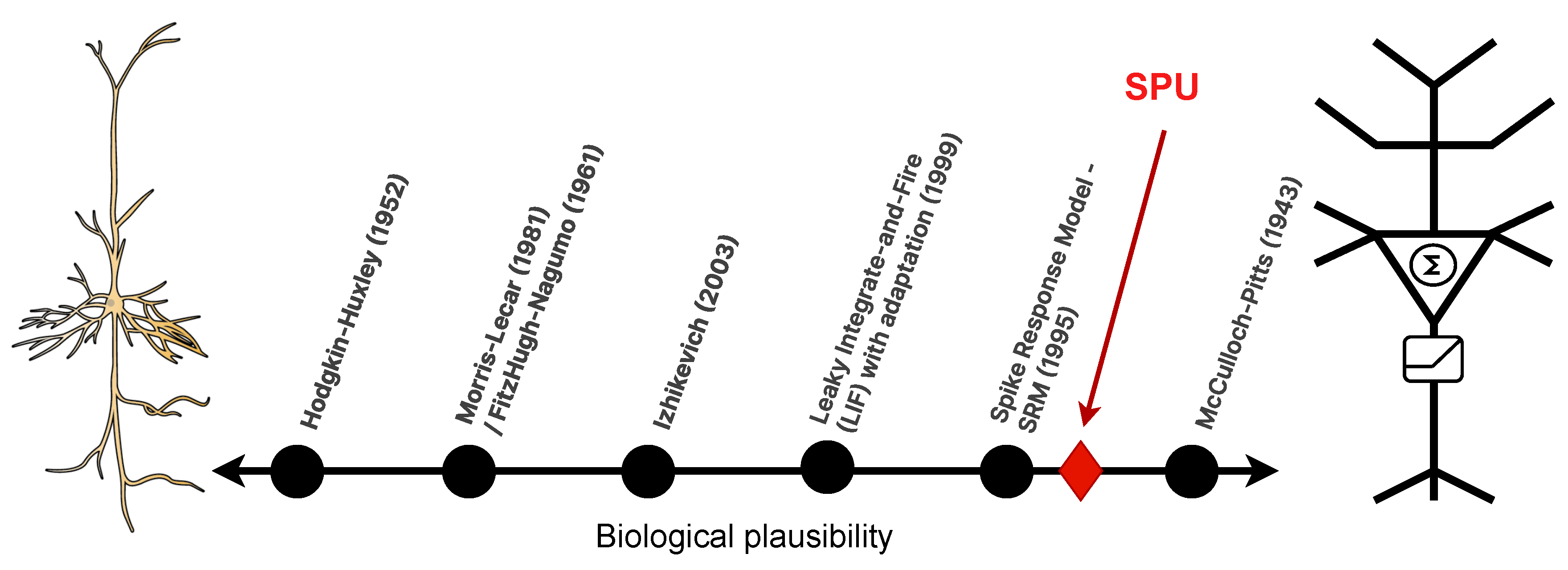

Computational neuroscience is fundamentally governed by a trade-off between biological plausibility and computational efficiency [

1]. This core tension delineates a spectrum of modeling approaches. At one extreme, biophysically detailed models such as Hodgkin-Huxley [

2] achieve high fidelity in replicating neural dynamics but incur prohibitive computational costs [

3,

4], limiting their practicality for large-scale simulations or applied engineering contexts. At the opposite extreme, the abstract neurons characterizing second-generation Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)—which evolved from the McCulloch-Pitts framework [

5], incorporated nonlinearities through the work of Widrow and Hoff [

6], and were later optimized via the Backpropagation algorithm [

7]—prioritize computational tractability and have become central to Deep Learning. However, this very abstraction has led to a pronounced divergence from the brain’s core architectural principles, forsaking key sources of its computational efficiency—such as event-based sparse communication, massive parallelism, and in-memory computation—that are inherent to spiking paradigms.

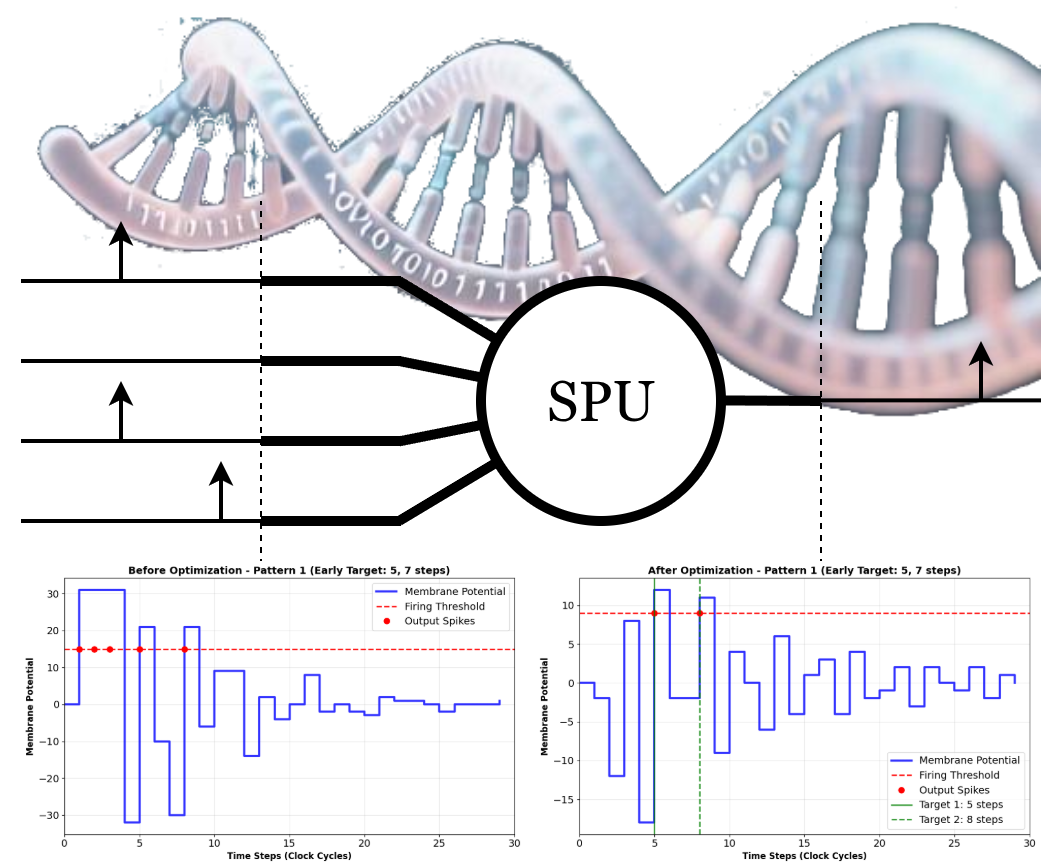

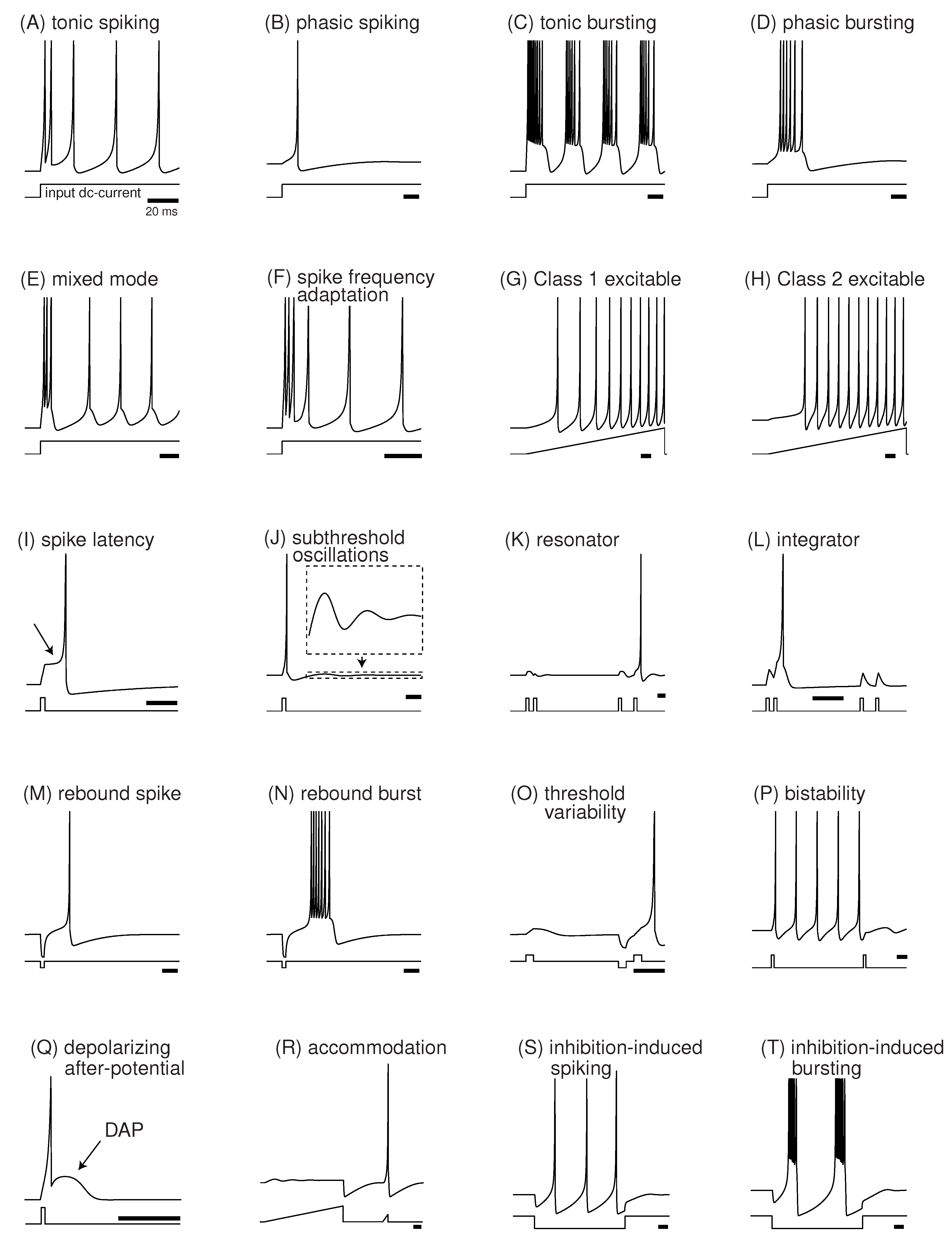

Occupying an intermediate position are simplified spiking models (

Figure 1), such as Izhikevich’s [

8], which strike a balance by reproducing key dynamical behaviors (

Figure 2) with reduced computational overhead. While effective in software, these models face a critical barrier in hardware implementation: their reliance on complex arithmetic operations, particularly digital multiplications with floating-point numbers, which are notoriously area- and power-intensive [

9]. This inefficiency directly contradicts the goal of neuromorphic computing—to create systems that emulate the brain’s exceptional energy efficiency [

10].

The exceptional efficiency of the nervous system arises from fundamental architectural principles that circumvent the von Neumann bottleneck [

11], a critical limitation in conventional computing architectures caused by the physical separation of memory and processing units. This architectural divide introduces significant performance and energy overheads, including data transfer latency, high energy costs associated with data movement, and limited scalability due to sequential processing constraints [

12]. In contrast, biological neural systems achieve remarkable computational efficiency through massive parallelism, in-memory processing [

13], and sparse, event-driven communication. Neuromorphic engineering seeks to emulate these principles in artificial systems, with Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) [

14] emerging as a leading paradigm in the third generation of neural network models. Unlike traditional artificial neural networks (ANNs), which rely on continuous-valued activations, SNNs encode information in the temporal dynamics of discrete spike events, rendering them inherently event-driven and highly energy-efficient.

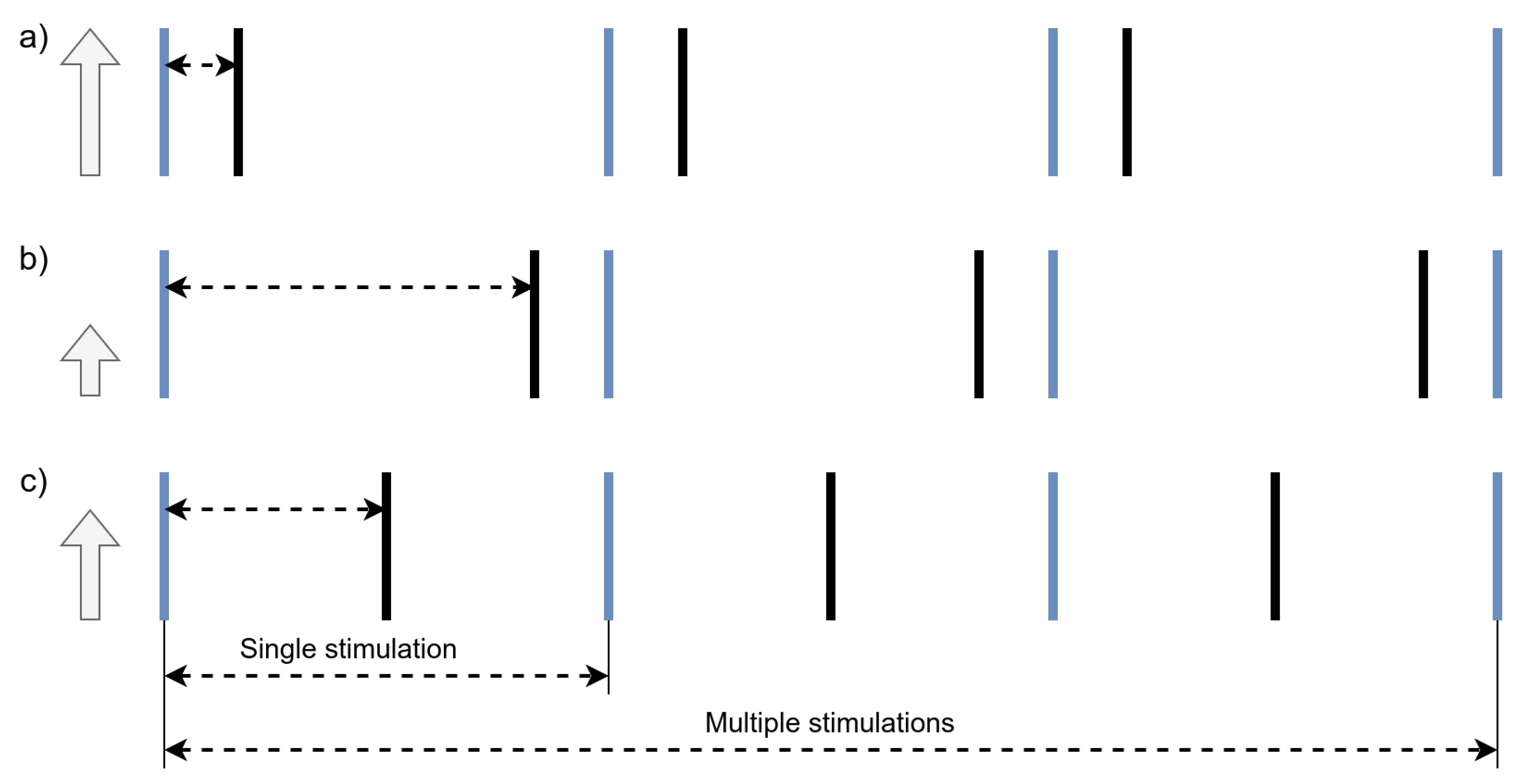

In SNNs, information is not represented by analog amplitudes or real-valued activations, but rather by the precise timing of spikes. The amplitude of individual spikes is invariant and thus carries no information; instead, computational meaning is derived from the temporal structure of spike trains. A particularly efficient and biologically plausible coding scheme is the Inter-Spike Interval (ISI) representation, in which analog values are encoded as the time interval between consecutive spikes—shorter intervals corresponding to higher values, and longer intervals to lower values. This coding strategy is illustrated in

Figure 3.

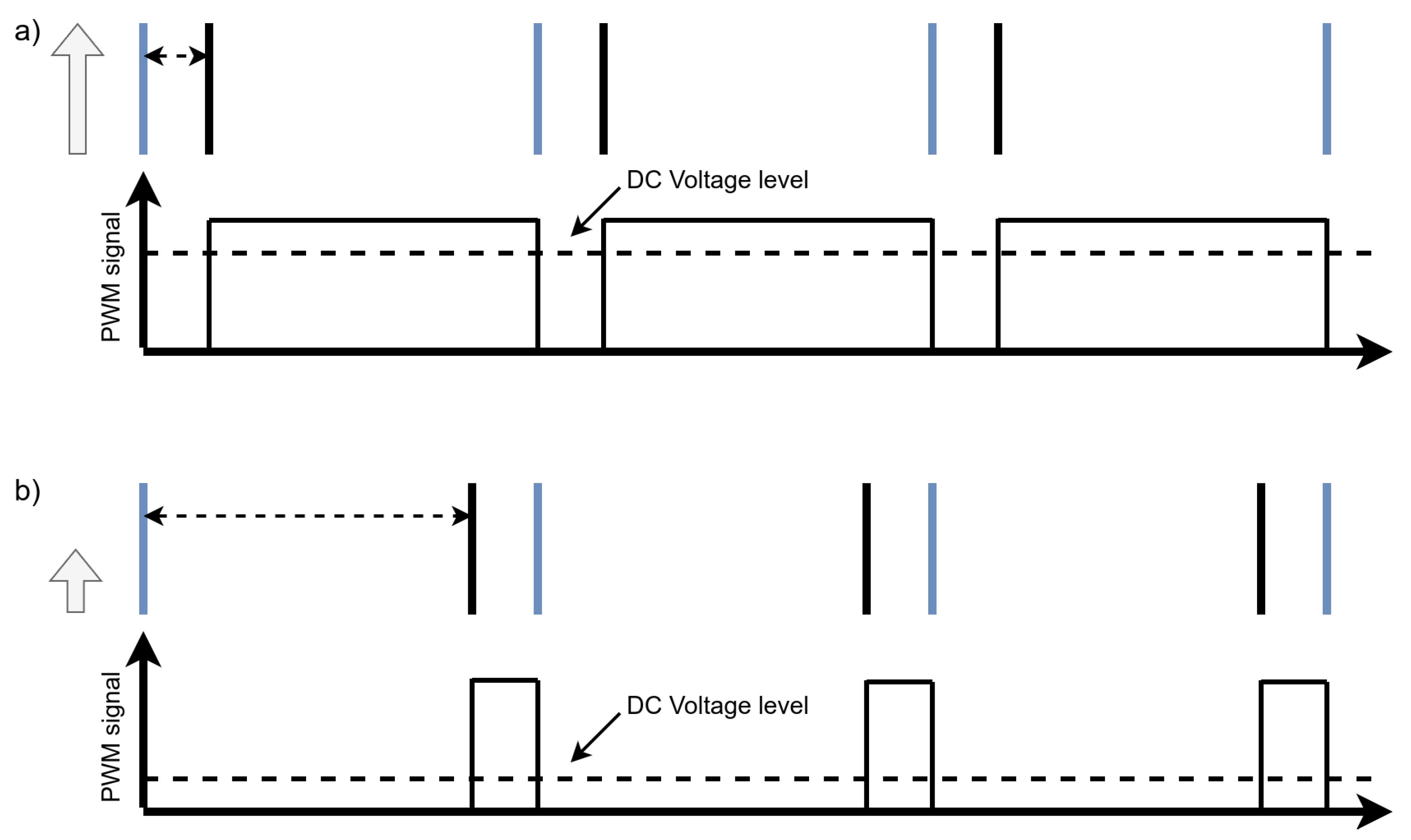

The ISI format offers significant advantages in terms of energy efficiency, as it requires only two spikes per value representation, minimizing neuronal activity and thereby reducing power consumption—especially critical in hardware implementations. Furthermore, at the network output, ISI-encoded signals can be directly converted into Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) signals, as depicted in

Figure 4. This conversion is particularly advantageous for real-world applications, as PWM is a widely adopted method for controlling actuators such as motors, LEDs, and other analog-driven devices.

By leveraging the ISI coding scheme, spiking neural networks can interface directly with sensors and actuators with minimal preprocessing or postprocessing circuitry, enabling end-to-end spike-based signal processing pipelines.

This work introduces the Spike Processing Unit (SPU), a novel digital neuron model designed with a hardware-first philosophy.

The remainder of this paper presents the SPU architecture, elucidates its operational principles, and demonstrates through simulation its capacity to be trained via a genetic algorithm for temporal pattern discrimination. These results validate the model’s functional correctness and highlight its potential as a foundation for ultra-low-power, event-driven neuromorphic systems.

2. The Spike Processing Unit (SPU) Model

This section details the architecture and operational principles of the Spike Processing Unit (SPU), a novel neuron model designed for ultra-low-power digital implementation. The model is built upon a discrete-time Infinite Impulse Response (IIR) filter and incorporates several key innovations to eliminate digital multipliers and minimize hardware resource usage.

2.1. Model Overview and Computational Philosophy

The design of the Spike Processing Unit (SPU) is guided by a fundamental hypothesis: that maximal hardware efficiency in neuromorphic systems is achieved not through the incremental approximation of biological fidelity, but through a functionalist abstraction. This philosophy prioritizes the preservation of computational essence—such as temporal integration, thresholding, and spike-based communication—while deliberately discarding biologically inspired but computationally expensive mechanisms.

The SPU embodies this principle by aiming to replicate the core computational

role of a biological neuron rather than its precise biological

mechanics. The model receives spike events on its inputs, integrates them into a membrane potential variable via an Infinite Impulse Response (IIR) filter that mimics synaptic dynamics and membrane potential integration, and generates an output spike when this potential exceeds a threshold. The key innovation of this architecture—beyond its conceptual shift—is the constraint of all IIR filter coefficients to powers of two. This critical design choice enables the replacement of power-hungry arithmetic multipliers with low-cost bit-shift operations. When combined with 6-bit two’s complement integer arithmetic and inter-spike interval (ISI) based temporal coding, the model becomes entirely multiplier-free and fundamentally optimized for efficient digital hardware implementation.

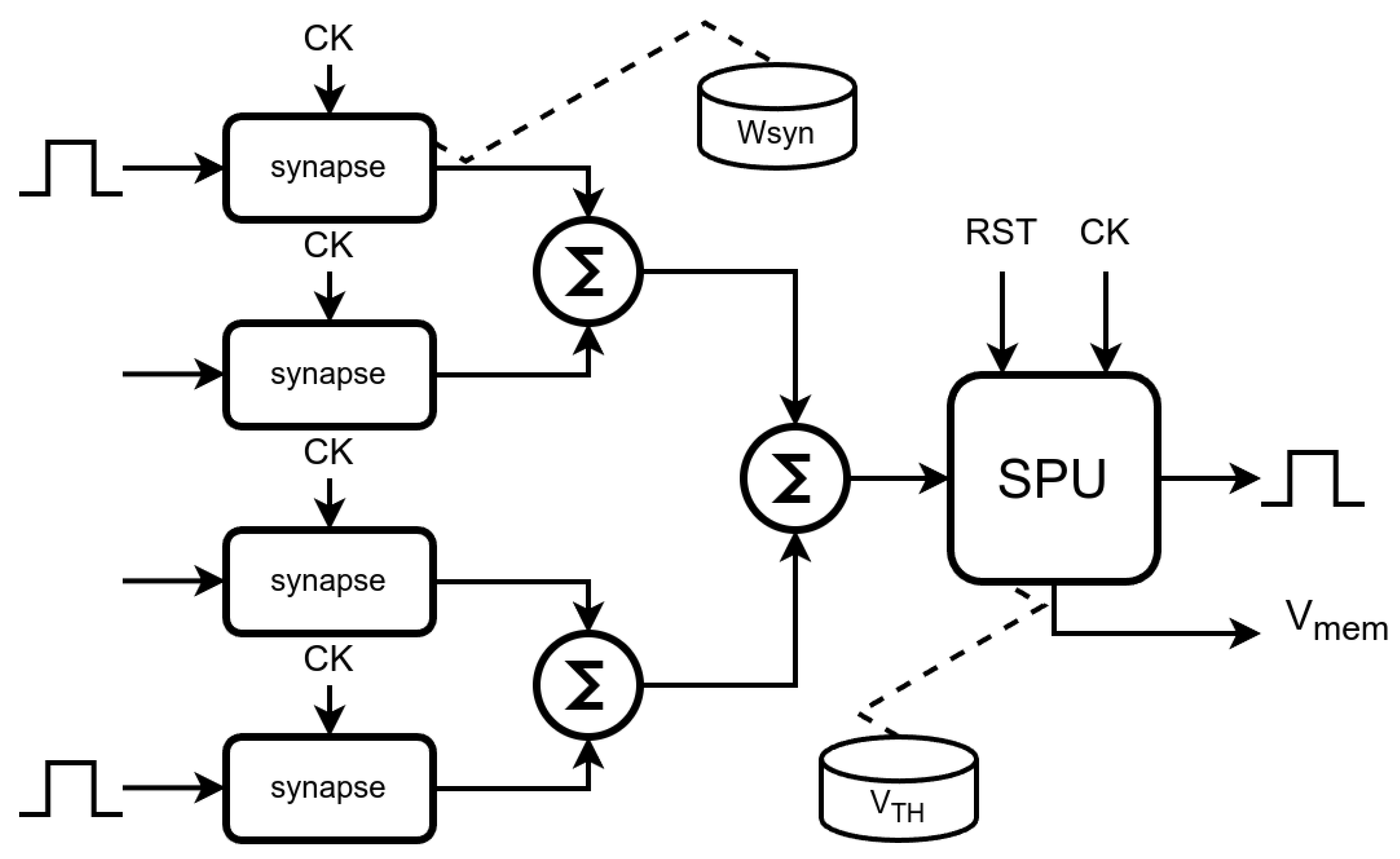

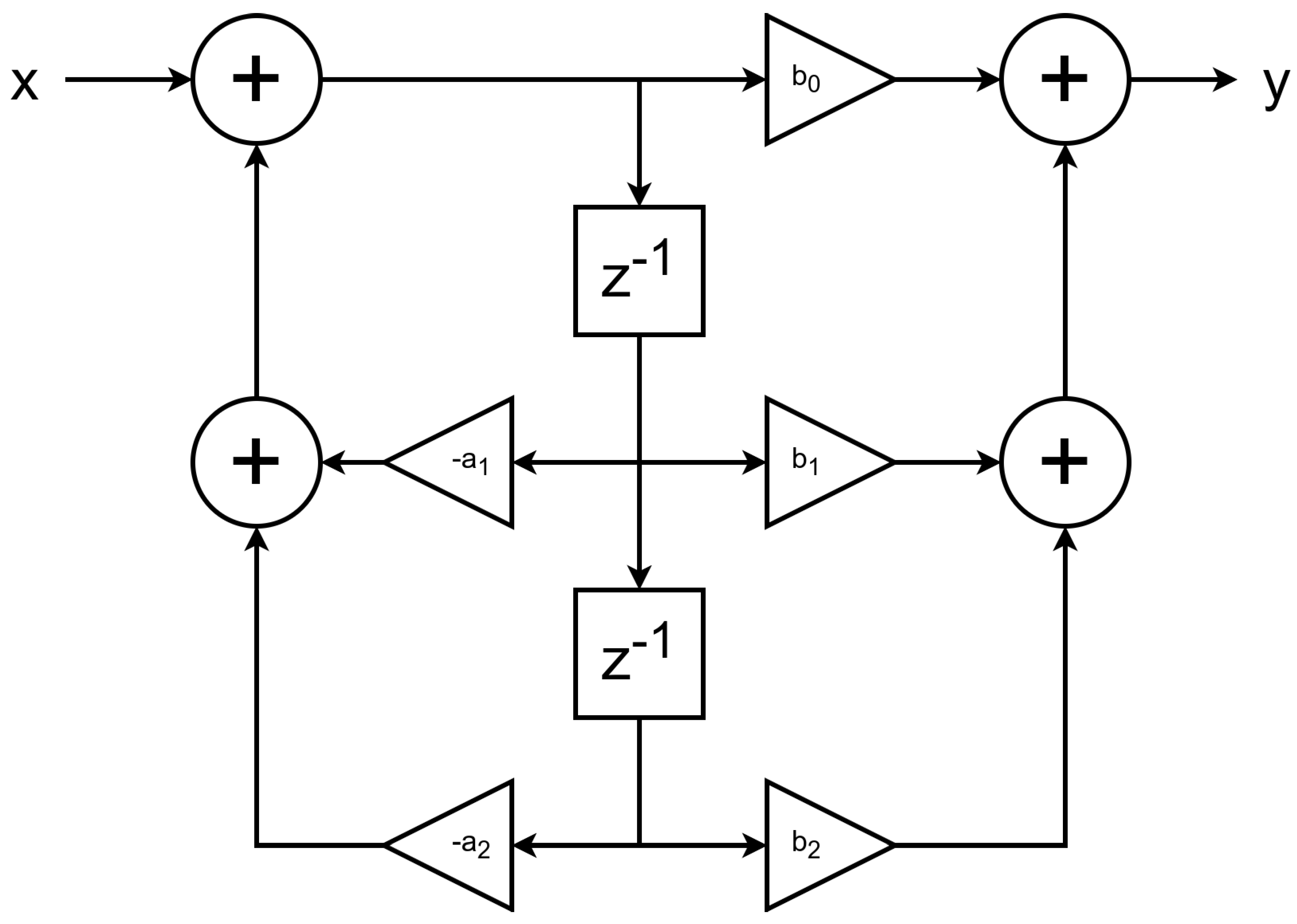

Figure 5 provides a high-level block diagram of the SPU’s architecture, while

Figure 6 details the second-order IIR filter that forms its computational core.

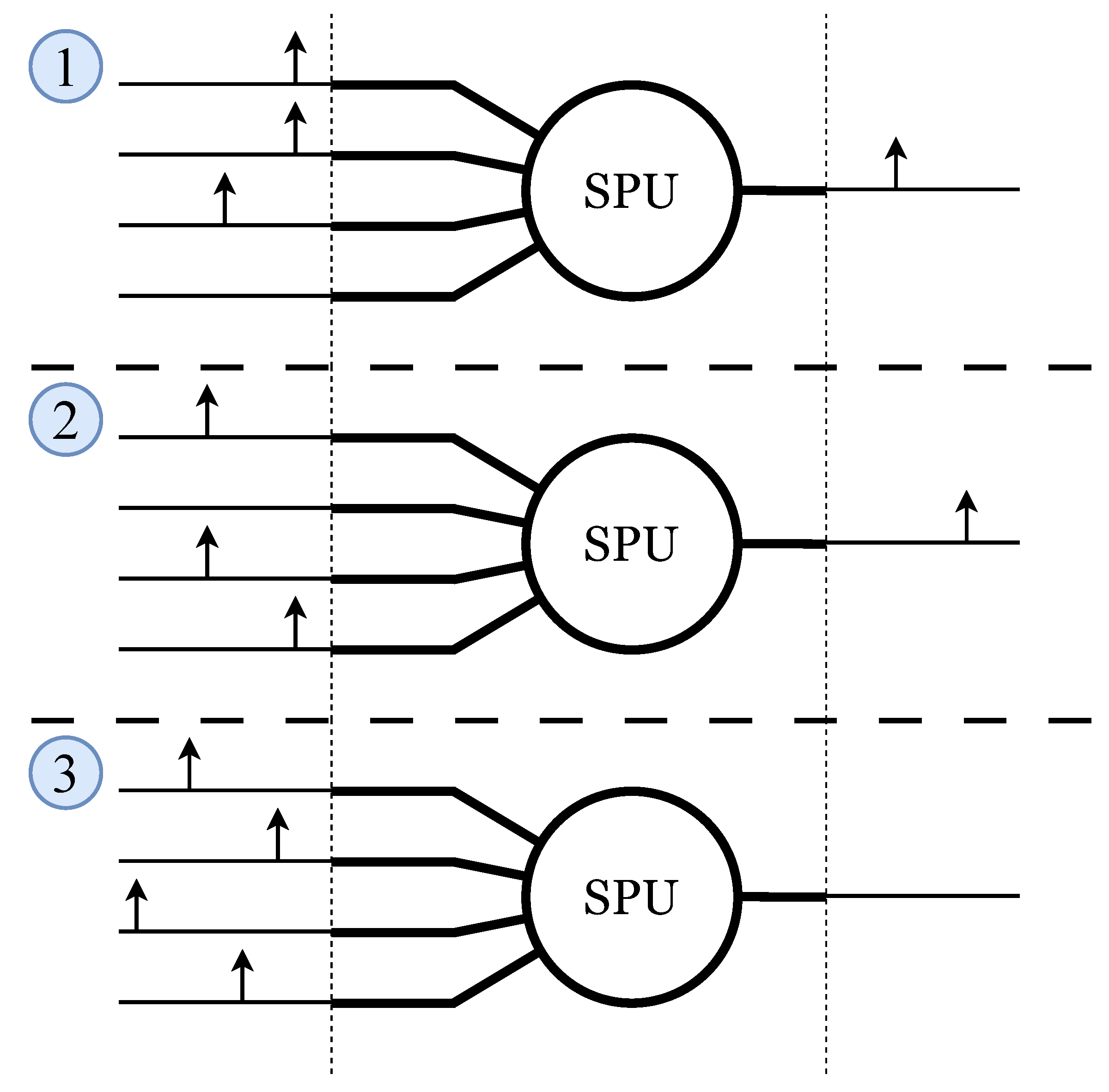

The SPU (

Figure 5) can be scaled to include as many synapses as required by adding more synapse modules and summing nodes to the

soma (SPU’s body).

The clock signal, CK, serves as a form of “time constant” for the neuron. In theory, each SPU could operate at a different clock frequency. In practice, two distinct clock frequencies could be defined to emulate fast and slow neurons, or a single frequency could be used, and so relying only on the SPU’s dynamics to process the spikes.

2.2. Synaptic Input and Weighted Summation

The SPU features

M synaptic inputs. Each synapse has an associated weight

, stored as a 6-bit two’s complement integer. The total synaptic input

at discrete time step

n is the sum of the weights of all synapses that received a spike in that clock cycle:

where

indicates the presence (1) or absence (0) of a spike on synapse

m at time

n.

That means, when a spike arrives at the input, the synapse presents its weight value to the summing node and keeps it there until it is sampled by the SPU soma (neuron body) at the rising edge of the clock signal. Additionally, the synapse acts as a buffer to synchronize the SPU’s clock frequency with the unpredictable timing of input spikes.

2.3. IIR Filter as Membrane Dynamics

The core of the SPU is a second-order IIR filter (

Figure 6), which calculates the current membrane potential

based on current and past inputs and past outputs:

The key innovation is the constraint of the coefficients

and

to the set

. This allows all multiplications in Equation (

2) to be implemented as simple arithmetic bit shifts and additions/subtractions, completely eliminating the need for digital multiplier circuits.

2.4. Spike Generation and Reset Mechanism

An output spike

is generated at time

n if the membrane potential

exceeds a trainable threshold parameter

:

This is accomplished by a simple digital comparator coupled with a register used to store the threshold value.

The dynamics of the IIR filter govern the temporal evolution of the membrane potential, producing behaviors that range from rapid decay and damped oscillations to more complex resonant patterns. This inherent dynamics renders an explicit reset mechanism unnecessary. Crucially, the interaction of incoming spikes with the filter’s lingering impulse response is not a limitation but a fundamental feature: it enables the SPU to process information encoded in inter-spike intervals (ISI), where an initial pulse excites the filter and subsequent pulses modulate its state. This property provides each SPU with a form of short-term memory and allows for rich, temporal interactions within a network. Moreover, this design leverages the well-established mathematical framework of digital filter theory, facilitating analysis and optimization through standard signal processing techniques.

Still, a reset signal (RST in

Figure 5) is present in each SPU unit for system initialization purposes, or even to allow the application of some strategies like "Winner Takes All", in which the first neuron to fire inhibits neighboring cells.

2.5. Information Representation and Hardware-Optimized Precision

A fundamental choice in neuromorphic engineering is how information is encoded and transmitted. The SPU model leverages two complementary strategies to achieve hardware efficiency: a temporal coding scheme and a low-precision numerical representation.

2.5.1. Inter-Spike Interval (ISI) Coding

The SPU employs inter-spike interval (ISI) coding for both input and output communication. In this scheme, information is encoded in the temporal intervals between successive spike events rather than in analog signal amplitudes. This form of temporal coding is not only biologically plausible but also inherently digital and sparse, leading to high energy efficiency in event-based systems. Importantly, ISI coding decouples signal representation from the precision of internal arithmetic operations. The exact integer value of the membrane potential is functionally irrelevant; only the timing of its threshold crossing carries information. This architecture ensures inherent robustness to quantization errors and saturation effects that are unavoidable in low-precision numerical implementations.

Moreover, the SPU’s strictly spike-based processing paradigm eliminates the need for explicit time measurement as a source of numerical information, avoiding the approximations inherent in such approaches. The system operates purely through reactive processing of spike sequences, further enhancing its hardware efficiency.

2.5.2. Low-Precision Integer Arithmetic

To exploit the benefits of temporal coding, all internal state variables () and parameters () are represented as 6-bit two’s complement integers. The coefficients are represented in floating-point for simulation purposes, but the multiplication of these coefficients by the synaptic weights is rounded to an integer before proceeding with the sums. In the hardware implementation, the coefficients are not explicitly represented in numerical form, as they are obtained by bit-shifting the input values. To achieve this, a configuration register is required. The low-precision numerical representation minimizes the size of the registers and the logic area.

This drastic reduction in bit-width, compared to standard 32-bit floating-point representations, directly translates to hardware gains:

Reduced Silicon Area: Smaller registers and arithmetic units (e.g., adders, shifters) consume less physical space on a chip.

Lower Power Consumption: Switching activity on fewer bits and the elimination of complex multiplier circuits significantly reduces dynamic power dissipation.

Increased Operating Frequency: Simpler logic with shorter critical paths can potentially allow for higher clock speeds.

The synergy between ISI coding and low-precision integers is the cornerstone of the SPU’s efficiency. The former ensures functionality is preserved, while the latter enables the hardware gains that are the model’s primary objective.

2.6. Filter Order and Neural Dynamics Repertoire

The order of the IIR filter is a critical hyperparameter that determines the richness of the dynamical behaviors the SPU can exhibit. The choice of a second-order system represents a deliberate trade-off between computational complexity and functional capability, enabling the emulation of key neural computations.

First-Order (e.g., LIF equivalence): A first-order IIR filter can be configured to precisely replicate the behavior of a Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) neuron. It performs a simple, exponential integration of input currents, characterized by a single time constant governing the decay of the membrane potential. It is possible to get oscillatory behavior allowing the presence of zeros and poles in the filter equation. While highly efficient, its behavioral repertoire is fundamentally limited to passive integration and is insufficient for modeling more complex phenomena like resonance or damped oscillations.

Second-Order (Proposed Model): The second-order transfer function introduced in Equation (

2) is the minimal configuration required to model resonant dynamics and damped oscillations. The pair of poles in the system’s transfer function allows it to be tuned to some resonant frequencies (considering the limitations imposed by the constrained coefficients), meaning the neuron can become selectively responsive to input spikes arriving at a particular frequency. This aligns with the behavior of certain biological neurons that exhibit subthreshold resonance [

15], enhancing their ability to discriminate input patterns based on temporal structure. This capability to act as a bandpass filter is a significant advantage over first-order models for temporal signal processing tasks.

Higher-Order (Third and Fourth): Third and fourth-order filters offer an even richer dynamical repertoire, including multiple resonant peaks, more complex oscillatory behaviors, and sharper frequency selectivity. However, this increased behavioral complexity comes at a steep cost: each increase in order adds two more state variables, more coefficients to store and manage, and a significant increase in the complexity of the parameter space for training. For most target applications, the marginal gain in functionality does not justify the quadratic increase in hardware resources and training difficulty.

The choice of a second-order model for the SPU is therefore a “sweet spot”. It provides a necessary improvement in computational functionality over first-order models—specifically, the ability to process information in the frequency domain through resonance—while avoiding the prohibitive costs of higher-order systems. If more complex behavior needs to be modeled, this can be accomplished by the network itself, not by the individual neuron. But if this were unavoidable, a higher-order model can be obtained simply by chaining together second-order models (by propagating in this case). The theoretical framework remains the same, from the simplest to the most complex models.

The dynamical behavior of the SPU is governed by the values of its IIR coefficients (

,

), which determine its filtering properties (e.g., low-pass, band-pass, resonant frequency), and the synaptic weights (

) and threshold (

), which determine its sensitivity and spiking behavior. This combination allows a single second-order SPU to exhibit a versatile repertoire of functionalities crucial for processing spike trains, such as tonic spiking, bursting, phasic spiking, and transient response to specific input frequencies (see some of these behaviors on

Figure 2).

Another fundamental characteristic of the SPU, when compared to traditional neuron models, is that its coefficients can also be trainable parameters, thus expanding its behavioral repertoire in response to input stimuli. Traditional models rely solely on variations in their synaptic weights and, eventually, their activation threshold, to respond appropriately to any input stimulus.

3. Simulation Framework and Training Methodology

This section describes the software simulation framework developed to validate the SPU model, the design of the temporal pattern discrimination task, and the genetic algorithm (GA) used to train the SPU’s parameters.

3.1. Software Simulation and Numerical Representation

A cycle-accurate simulation of the SPU was implemented in Python to validate its functionality before hardware deployment. The simulation strictly adheres to the proposed numerical constraints: all operations—including the arithmetic shifts for coefficient multiplication—are performed using 6-bit two’s complement integer arithmetic. This ensures that the simulation accurately models the quantization and overflow behavior that will occur in the actual digital hardware, providing a faithful representation of the system’s performance.

3.2. Temporal Pattern Discrimination Task

To evaluate the computational capability of a single SPU, a temporal pattern discrimination task was designed. The neuron receives input from four synapses (), each capable of receiving a spike train.

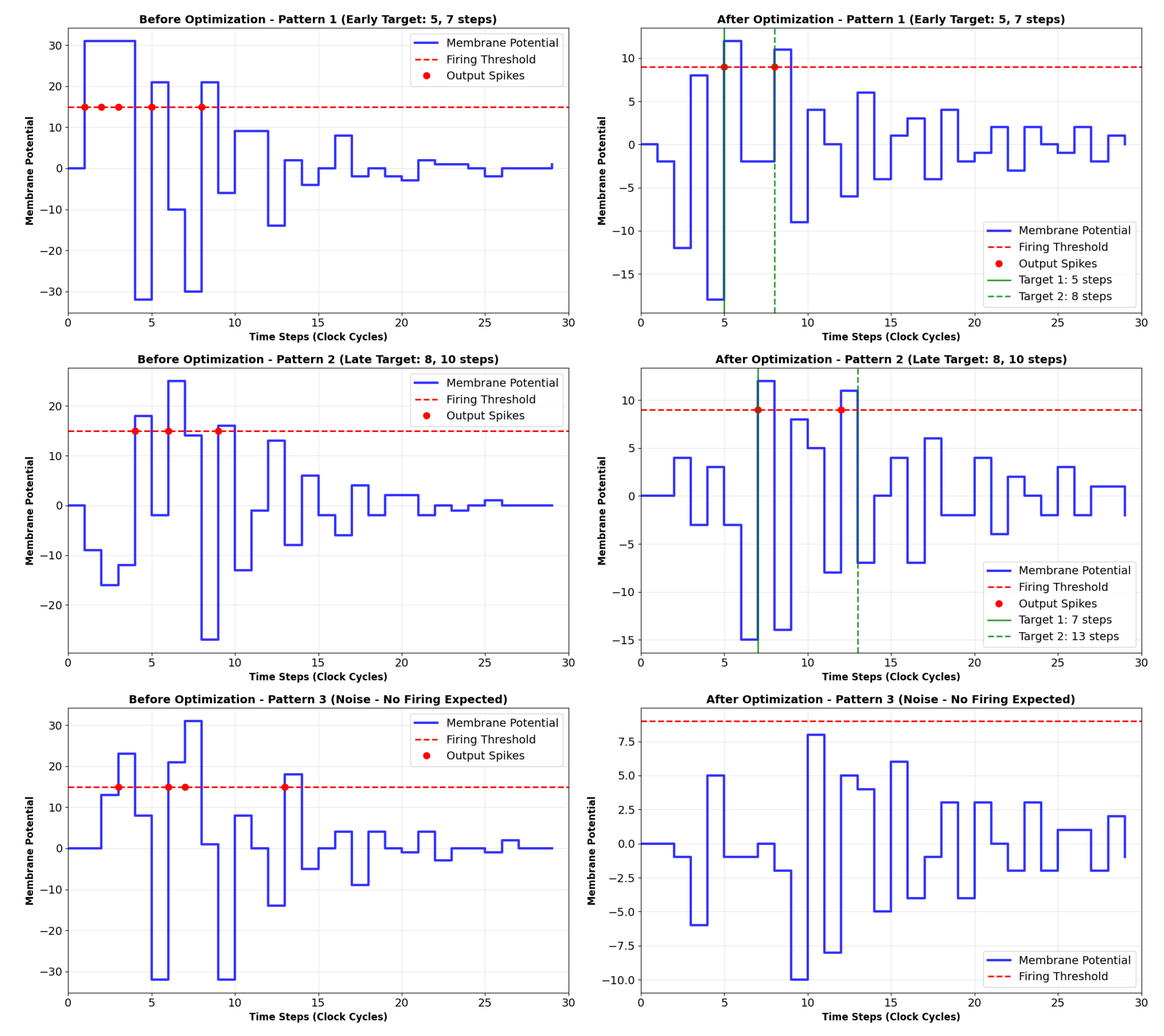

The desired behavior for the SPU is to emit a single output spike at a unique, pattern-specific time step in response to Pattern A and Pattern B, and to remain silent (i.e., produce no output spikes) when presented with Pattern C.

A second pattern discrimination task was also devised: for the same input patterns, the SPU was trained to generate two output pulses at well-defined times. This approach is useful if the output is to be encoded in ISI format.

Table 1.

SPU Input Stimulus Pattern Specifications and Desired Outputs (double spike)

Table 1.

SPU Input Stimulus Pattern Specifications and Desired Outputs (double spike)

| Pattern |

Input Stimuli (Synapse ID, Time Step) |

Desired Outputs (Time Steps) |

| Pattern 1 |

Synapse A: timestep 1

Synapse B: timestep 1

Synapse C: timestep 3

|

First spike: timestep 5

|

| |

|

Second spike: timestep 8

|

| Pattern 2 |

Synapse D: timestep 1

Synapse A: timestep 5

Synapse C: timestep 5

|

First spike: timestep 7

|

| |

|

Second spike: timestep 13

|

| Pattern 3 (Noise) |

Synapse B: timestep 2

Synapse D: timestep 4

Synapse A: timestep 6

Synapse C: timestep 8

|

No expected spike |

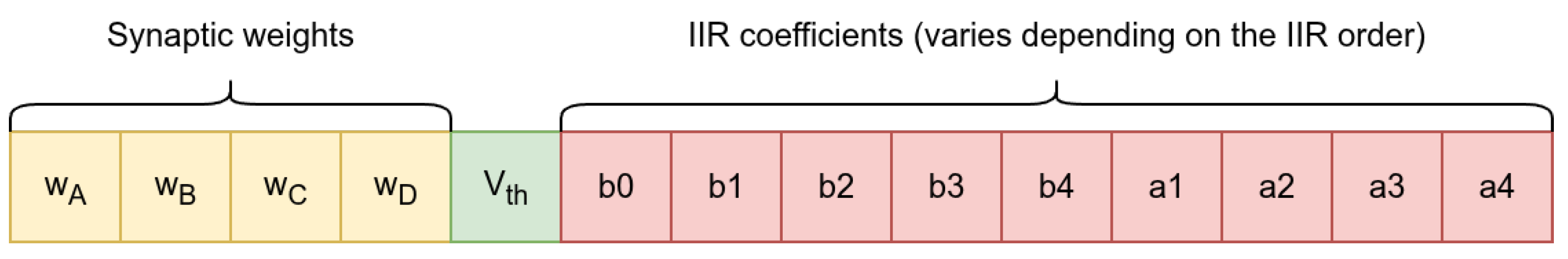

3.3. Genetic Algorithm for Parameter Training

This work employs a standard genetic algorithm (GA) to optimize the parameters of the Spike Processing Unit—SPU (see

Table 2). A population of chromosomes, each encoding the SPU’s synaptic weights, firing threshold, and IIR filter coefficients, is iteratively evolved. The fitness of each candidate solution is evaluated based on its accuracy in performing a temporal pattern discrimination task, specifically rewarding correct output spike timing for target patterns and suppression of activity for noise. Tournament selection, single-point crossover, and constrained point mutation (ensuring coefficients remain valid powers of two) form the core of the evolutionary process. The algorithm concludes after a fixed number of generations, with the highest-fitness solution representing a functionally competent and hardware-optimized SPU configuration.

Figure 8.

Chromosomal representation of SPU. Each “gene” represents a specific characteristic.

Figure 8.

Chromosomal representation of SPU. Each “gene” represents a specific characteristic.

An exceptionally high mutation rate was used to maximize the exploration capacity of the problem space, while elitism ensures the maintenance of better-fit individuals.

Optimizing the genetic algorithm, or employing variations based on evolutionary strategies, is beyond the scope of this work and can be further explored in future publications, in conjunction with SPU-based neural network training methodologies.

3.4. Experimental Setup

The experimental procedure consisted of initializing a population of chromosomes with randomized parameters and executing the genetic algorithm for a predetermined number of generations. The performance of the highest-fitness individual was subsequently evaluated against a held-out test set of pattern instances to assess its generalization capability.

Both experimental campaigns were successfully completed: the first trained the SPU to produce a single output pulse in response to specific patterns, while the second extended this capability to the generation of precisely timed double pulses.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results of the training process and the performance of the optimized Spike Processing Unit (SPU) on the temporal pattern discrimination task. The findings demonstrate the model’s capability to learn distinct temporal patterns and generalize its functionality under strict hardware-oriented constraints.

4.1. Trained SPU Dynamics and Performance

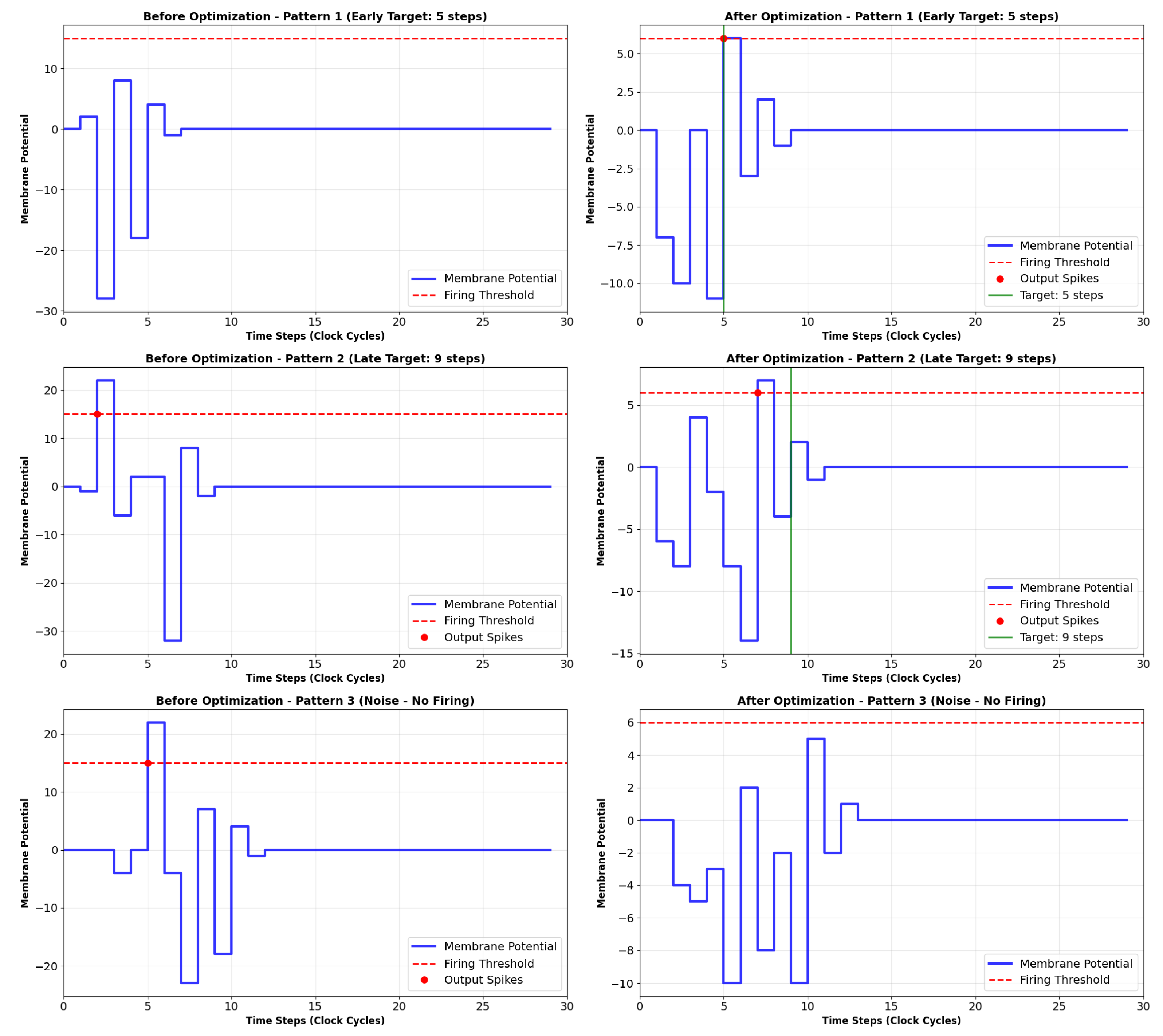

The functionality of the trained SPU is visualized in

Figure 9, which shows the membrane potential

and output spikes in response to the three input patterns.

For Pattern A and Pattern B, the membrane potential integrates the specific spatiotemporal input, crosses the threshold , and elicits an output spike at a distinct, pattern-specific time step. Crucially, the timing of the output spike is consistent and different for each pattern, fulfilling the core requirement of the task.

For Pattern C (Noise), the membrane potential fluctuates but never surpass the firing threshold, resulting in no output spikes. This demonstrates the SPU’s ability to suppress irrelevant inputs and respond only to the learned, salient patterns.

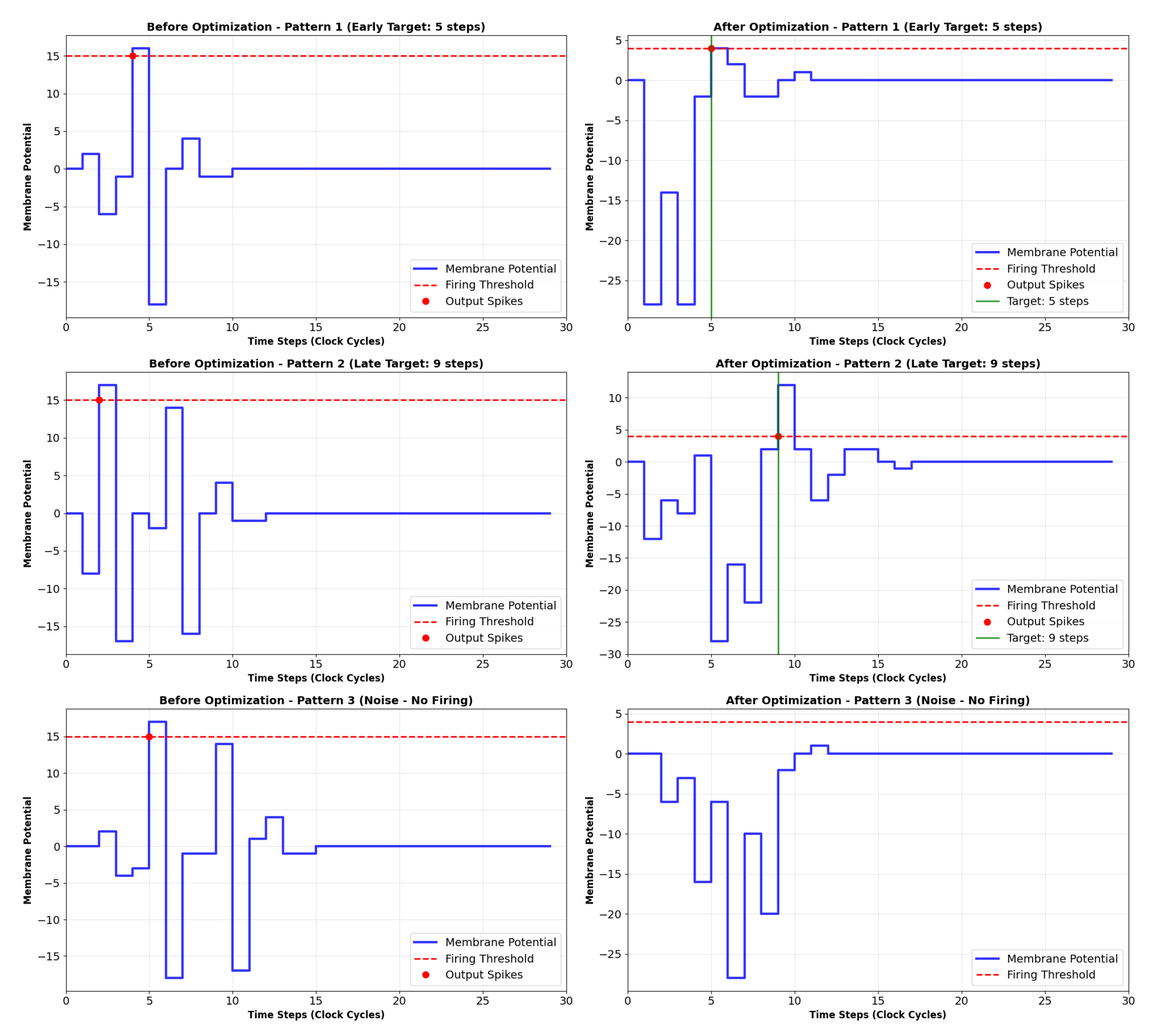

For comparison, the graph in

Figure 10 shows the temporal response of an SPU implemented from a first-order IIR. Although the training process has made progress, the positioning of one of the spikes presents a small temporal error. Such an error always exists in first-order filters, but the output can be perfectly adjusted with higher-order filters.

For the second pattern discrimination test, which expects a two-pulse output at set times, even a fourth-order IIR fails to correctly position the output. A network of SPUs is expected to solve this problem. This will be explored in a future publication.

The parameters discovered by the GA provide insights into the SPU’s operating principles. The values of the IIR coefficients (

) were valid powers of two, confirming the viability of the multiplier-free constraint. The synaptic weights

and the threshold

were also within the range of 6-bit integers. Observing

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, it is evident that the evolutionary approach was effective in determining the SPU’s parameters, thus proving its usefulness as a feasible model for spiking neurons.

4.2. Discussion on Functional Abstraction and Hardware Efficiency

The results serve as a successful

proof-of-concept for the core thesis of this work: that the computational

function of a spiking neuron can be abstracted into a multiplier-less IIR filter operating on low-precision integers. The SPU did not replicate biological action potential waveforms (c.f.

Figure 2), yet it successfully performed a non-trivial temporal processing task. This functionalist approach is the key enabler of the promised hardware efficiency.

The chosen constraints directly translate to hardware advantages:

Multiplier-Free Design: The filter coefficients require only shift-and-add operations.

Minimal Area Footprint: 6-bit registers and integer arithmetic units significantly reduce silicon area compared to 32-bit floating-point equivalents.

Low Power Consumption: The elimination of multipliers and the use of simple logic gates lead to a reduction in dynamic power.

The successful performance demonstrated in

Section 4.1 validates the core premise that ISI coding renders the system’s function robust to the quantization errors inherent to the low-precision arithmetic, thereby enabling these hardware benefits.

While a second-order IIR SPU can be successfully trained to produce a single output spike at a precise time, our experiments indicate that generating accurately timed double spikes requires a higher-order dynamic response. Specifically, even a fourth-order IIR implementation proved insufficient for this more complex temporal patterning. A comprehensive analysis of multi-spike generation, including the required filter order and novel training methodologies, will be the subject of a future publication, following the completion of our ongoing study on SPU network dynamics and learning rules.

This demonstrates that the SPU represents a pragmatic trade-off, sacrificing biological detail for orders-of-magnitude gains in hardware efficiency, making it suitable for large-scale neuromorphic systems on resource-constrained edge devices.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper has introduced the Spike Processing Unit (SPU), a novel hardware-oriented model for spiking neurons that prioritizes computational efficiency and hardware implementability over biological plausibility. The core innovation of the SPU lies in its formulation as an Infinite Impulse Response (IIR) filter with coefficients constrained to powers of two, enabling a fully multiplier-free design where all multiplications are reduced to simple bit-shift operations. Coupled with a low-precision 6-bit two’s complement integer representation and event-driven processing based on inter-spike intervals (ISI), the model is fundamentally designed for minimal resource consumption in digital hardware.

The viability of this approach was demonstrated through a temporal pattern discrimination task. A single SPU was successfully trained via a genetic algorithm to distinguish between two specific spatiotemporal spike patterns and suppress its output for a random noise pattern. This result serves as a critical proof-of-concept, confirming that the SPU—despite its extreme architectural simplifications—can perform non-trivial temporal processing essential for neuromorphic computing. The functionalist approach, which focuses on replicating the computational role of a neuron rather than the form of its biological dynamics, has proven to be a viable path toward extreme hardware efficiency.

5.1. Summary of Contributions

The primary contributions of this work are fourfold:

A Novel Neuron Model: The introduction of the SPU, a multiplier-less, IIR-based spiking neuron model that operates entirely on low-precision integers.

A Hardware-First Design Philosophy: A demonstration that divorcing functional computation from biological realism can yield drastic gains in hardware efficiency, offering a new design pathway for neuromorphic engineering.

A Validation Methodology: A framework for training and evaluating the SPU using genetic algorithms on a temporal processing task, proving its computational capability.

A Foundation for Scalable Systems: The SPU provides a foundational building block for constructing large-scale, energy-efficient SNNs that are feasible to implement on FPGAs and ASICs for edge computing applications.

5.2. Future Work

This work establishes a foundation for several promising avenues of future research:

Hardware Implementation: The immediate next step is the physical implementation of the SPU on an FPGA platform. This will provide concrete measurements of area, power consumption, and maximum clock frequency, allowing for a direct comparative analysis against other neuron models from the literature.

Network-Level Integration: Exploring the behavior of networks of interconnected SPUs is crucial. Research directions include studying recurrent network dynamics for reservoir computing and developing learning rules (e.g., a modified Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity - STDP) capable of training not only synaptic weights but also the IIR coefficients themselves.

Advanced Applications: Applying SPU-based networks to more complex benchmark tasks, such as spoken digit recognition or time-series prediction, will be essential for benchmarking its performance against established ANN and SNN models.

Algorithm-Hardware Co-Design: Further exploration of the trade-offs between numerical precision, filter order, and task performance could lead to optimized variants of the SPU for specific application domains.

In conclusion, the SPU model represents a significant step toward the development of truly efficient and scalable neuromorphic systems. By embracing a functionalist approach and rigorous hardware-oriented constraints, it offers a compelling alternative to more biologically complex models, paving the way for the next generation of low-power, brain-inspired computing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANN |

Artificial Neural Network |

| GA |

Genetic Algorithm |

| IIR |

Infinite Impulse Response (filter) |

| ISI |

Inter-Spike Interval |

| LIF |

Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (neuron model) |

| SNN |

Spiking Neural Network |

| SPU |

Spike Processing Unit |

References

- Brette, R.; Rudolph, M.; Carnevale, T.; Hines, M.; Beeman, D.; Bower, J.M.; Diesmann, M.; Morrison, A.; Goodman, P.H.; Harris, F.C.; et al. Simulation of networks of spiking neurons: A review of tools and strategies, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Hodgkin, A.L.; Huxley, A.F. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J. Physiol. 1952, 117, 500–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Collado, A.; Rueda, C. A simple parametric representation of the Hodgkin-Huxley model. PLoS ONE 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, P.H.; Oliveira, B.C.; de, S. Souza, A.A.; Blanco, W. Mitigating Computer Limitations in Replicating Numerical Simulations of a Neural Network Model With Hodgkin-Huxley-Type Neurons. Front. Neuroinformatics 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, W.S.; Pitts, W. A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. Bull. Math. Biophys. 1943, 5, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widrow, B.; Hoff, M.E. Neurocomputing, Volume 1, 1 ed.; Vol. 1, The MIT Press, 1988; pp. 96–104. [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhikevich, E. Simple model of spiking neurons. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2003, 14, 1569–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.; Srinivasa, N.; Lin, T.H.; Chinya, G.; Cao, Y.; Choday, S.H.; Dimou, G.; Joshi, P.; Imam, N.; Jain, S.; et al. Loihi: A Neuromorphic Manycore Processor with On-Chip Learning. IEEE Micro 2018, 38, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, W.B.; Calvert, V.G. Communication consumes 35 times more energy than computation in the human cortex, but both costs are needed to predict synapse number. Biophys. Comput. Biol. 2021, 27, 2008173118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backus, J. Can programming be liberated from the von Neumann style? Commun. ACM 1978, 21, 613–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdahl, G.M. Validity of the single processor approach to achieving large scale computing capabilities. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the April 18-20, 1967, spring joint computer conference on - AFIPS ’67 (Spring). ACM Press, 1967, p. 483. [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Jaiswal, A.; Panda, P. Towards spike-based machine intelligence with neuromorphic computing. Nature 2019, 575, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maass, W. Networks of Spiking Neurons: The Third Generation of Neural Network Models. Technical report, 1997.

- Hutcheon, B.; Yarom, Y. Resonance, oscillation and the intrinsic frequency preferences of neurons. Trends Neurosci. 2000, 23, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Short Biography of Authors

|

Hugo Puertas de Araújo holds a Ph.D. in Microelectronics (2004), an M.Sc. (2000), and a B.Sc. in Electrical Engineering (1997), all from the Polytechnic School of the University of São Paulo (USP). With expertise in cleanroom procedures and micro-electronics, he began his career at LSI-USP before joining IC Design House LSI-TEC, where he led projects in integrated circuit design and IoT platform development. Currently, he is an Associate Professor at UFABC’s Center for Mathematics, Computation and Cognition (CMCC), with research focused on Artificial Neural Networks and Neuromorphic Hardware for advanced computing. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).