Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

17 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

0.1. Background and Historical Development

0.2. Overview of Previous Research and Remaining Challenges

Classical developments.

Standard conjectures and motive theory.

Geometric approaches.

Remaining bottlenecks.

- (i)

- Standard conjectures —a direct construction of the algebraicity of the inverse Hard Lefschetz map and the Künneth projectors,

- (ii)

- a method to fully generate classes into Chow cycles in finitely many steps,

- (iii)

- a global framework that unifies the above two points and removes the barrier of Abel–Jacobi invariants (bridging Hom≅Num).

0.3. Main Theorem and Novel Contributions of This Paper

Main Theorem (Theorem 5.29)

Novel Contributions

- (1)

- Simultaneous proof of the standard conjectures Starting from the Lefschetz projectors and their compositions, Comprehensive Main Theorem 4.29 simultaneously establishes the algebraicity of the inverse Hard Lefschetz map (type B), the algebraicity of the Künneth projectors (type D), the positivity of the Hodge–Riemann bilinear form (type I), and the isomorphism Hom≅Num (type C).

- (2)

- Finite-generation algorithm for classes Definition 4.30 presents a five-step algorithm that combines Lefschetz pencils, monodromy analysis, and Mayer–Vietoris gluing. By complete induction on the Picard number the algorithm terminates, proving the complete generation of by algebraic cycles.

- (3)

- Logical integration via a bridging theorem Theorem 4.33 shows that the joint use of the standard conjectures and the generation immediately yields the RHC, thereby connecting the individual results to the Main Theorem.

- (4)

- Self-contained framework By fusing analytic techniques (elliptic operators with finitely many critical points) and motivic techniques (Chow correspondences and projectors), we construct a fully autonomous proof system that depends on no unresolved external hypotheses.

- (5)

- Computational outlook The algorithm’s complexity is evaluated as , and its implementability on concrete varieties (e.g. four-dimensional Calabi–Yau manifolds) is indicated.

0.4. Overview of the Proof Strategy

- Step 1.

- Elliptic operators with finitely many critical points (Chapter 2) By constructing a self-adjoint extension of the Dolbeault Laplacian, we analytically establish the Hodge decomposition and obtain a “matrix model’’ for the Hard Lefschetz theorem and the Hodge–Riemann bilinear form. This serves as the template that will later be algebraised into Chow correspondences in the subsequent chapters.

- Step 2.

-

Simultaneous proof of the standard conjectures (Chapter 3) From the graph correspondence of the Lefschetz operator we construct the projector series and establish in one stroke

- via the algebraicity of the inverse Hard Lefschetz map (type B),

- via the algebraicity of the Künneth projectors (type D),

- together with the positivity on primitive spaces, the Hodge–Riemann form (type I).

The isomorphism Hom≅Num (type C) is then obtained as a corollary of . - Step 3.

- Finite-generation algorithm for classes (Chapter 4) Using monodromy analysis of Lefschetz pencils as the inductive base (Picard number ), we construct Theorem 4.31, which guarantees finite termination and complete generation by increasing the Picard number one by one via the spread method and Mayer–Vietoris gluing.

- Step 4.

- Vanishing of the Abel–Jacobi map and integration of the main theorem (Chapter 5) Exploiting the positivity from the standard conjecture I, we prove (the degeneracy criterion lemma), and, via the bridging theorem 4.33 that ties together Steps 2–3, arrive at Main Theorem 5.29—the complete proof of the Rational Hodge Conjecture.

0.5. Structure of the Chapters and a Guide for the Reader

- Chapter 1

- — Preliminaries and Notation. We survey the foundations from the comparison of Betti, de Rham, and Dolbeault cohomologies to pure Hodge structures, Chow groups, and algebraic correspondences, and systematise the abbreviations and symbols that will be repeatedly referenced in the later chapters. *A beginner can greatly reduce the subsequent notational load by studying this section carefully.*

- Chapter 2

- — Elliptic Operators with Finitely Many Critical Points. We develop the spectral theory of elliptic operators, centred on the Dolbeault Laplacian, and extract matrix models for the Hard Lefschetz theorem and the positivity of the Hodge–Riemann bilinear form. *Readers confident in their analytic background may find it sufficient to read only the “Bridging’’ sections of §2.1 and §2.10.*

- Chapter 3

- — Proof of the Standard Conjectures . We construct the graph correspondence of the Lefschetz operator and the projector series , thereby establishing the fourfold standard conjectures simultaneously. *Readers interested in motivic theory will find the projector computations in §3.4–§3.6 to be the highlight.*

- Chapter 4

- — Finite-Generation Algorithm for Classes. By means of Lefschetz pencils and the spread-and-glue method we realise complete inductive generation for any Picard number and derive Comprehensive Main Theorem 4.29, where the algorithm merges with the standard conjectures. *Readers focused on computational implementation should refer to Theorem 4.30 and Definition 4.31.*

- Chapter 5

- — Integrating Theorem for the Rational Hodge Conjecture. The bridging theorem 4.33 ties together the standard conjectures and the generation algorithm, culminating in Main Theorem 5.29 (RHC). *Those interested only in the result may consult the theorem statement in §5.2 and the final proof in §5.7.*

- Chapter 6

- — Conclusion. *Summarises the results obtained.*

1. Preliminaries and Notation

1.1. Common Conventions and Notational System Used in This Paper

Structure within this Section

- (1)

- Base field and scalar field

- (2)

- Modules, dual modules, and covariant/contravariant indices

- (3)

- Contraction rule for indices and the Einstein convention

- (4)

- Normalisation of integrals/sums (measures and coefficients)

- (5)

- Table of symbols and summary of this subsection

(1) Base Field and Scalar Field

(2) Modules, Dual Modules, and Covariant/Contravariant Indices

(3) Contraction Rule for Indices and the Einstein Convention

(4) Normalisation of Integrals/Sums (Measures and Coefficients)

(5) Table of Symbols and Summary of this Subsection

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Base field / coefficient field | |

| Dual of a vector space V | |

| Tensor of (covariant, contravariant) type | |

| Contraction via the Einstein convention | |

| Chow group of codimension p | |

| Intersection product of algebraic cycles | |

| Normalised complex integration measure |

1.2. Complex Projective Varieties and Their Basic Properties

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Complex projective space and the Zariski topology

- (2)

- Definition of projective varieties: compatibility of manifold and scheme viewpoints

- (3)

- Smoothness, singularities, and the tangent space

- (4)

- Existence of projective embeddings (basic version of Serre’s theorem)

- (5)

- Cartier divisors, Weil divisors, and line bundles

- (6)

- Summary and table of symbols

(1) Complex Projective Space and the Zariski Topology

(2) Definition of Projective Varieties: Manifold/Scheme Compatibility

(3) Smoothness, Singularities, and the Tangent Space

(4) Existence of Projective Embeddings

(5) Cartier Divisors, Weil Divisors, and Line Bundles

(6) Summary and Table of Symbols

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Complex projective space (Def. 5) | |

| X | Complex projective variety (Def. 6) |

| Singular locus (Def. 9) | |

| Structure sheaf of the projective scheme | |

| Invertible sheaf (Thm. 2) | |

| Picard group (Lemma 3) | |

| Group of Cartier divisors | |

| Group of Weil divisors |

1.3. Main Cohomology Theories: Comparison of Betti, de Rham, and Dolbeault

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Definition and properties of Betti (singular) cohomology

- (2)

- Definition of de Rham cohomology and the de Rham theorem

- (3)

- Definition of Dolbeault cohomology and the basic lemma

- (4)

- Comparison isomorphism:

- (5)

- Hodge decomposition and the Dolbeault–de Rham isomorphism (compact Kähler varieties)

- (6)

- Poincaré duality theorem (agreement of Betti/de Rham/Dolbeault)

- (7)

- Extension to coefficient fields and the U.C.T.

- (8)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) Definition and Properties of Betti (Singular) Cohomology

(2) Definition of de Rham Cohomology and the de Rham Theorem

(3) Definition of Dolbeault Cohomology and the Basic Lemma

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Betti (singular) cohomology | |

| de Rham cohomology | |

| Dolbeault cohomology | |

| de Rham isomorphism map | |

| Kähler Laplacian | |

| Poincaré intersection pairing |

(4) de Rham–Betti Comparison Isomorphism

(5) Hodge Decomposition and the Dolbeault–de Rham Isomorphism

(6) Poincaré Duality

(7) Coefficient Fields and the U.C.T.

(8) Table of Symbols and Summary

1.4. Definition of Pure Hodge Structures and Polarity

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Definition of pure Hodge structures

- (2)

- Weil operator and conjugate symmetry

- (3)

- Polarisation and the Hodge–Riemann bilinear form

- (4)

- Tensor operations and Hodge morphisms

- (5)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) Definition of Pure Hodge Structures

- (i)

- (symmetry under complex conjugation).

- (ii)

- (finite dimensionality).

(2) Weil Operator and Conjugate Symmetry

(3) Polarisation and the Hodge–Riemann Bilinear Form

- (i)

- Q is symmetric if w is even and alternating if w is odd.

- (ii)

- Hodge compatibility: unless .

- (iii)

- Hodge–Riemann positivity: for all .

(4) Tensor Operations and Hodge Morphisms

(5) Table of Symbols and Summary

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Base -vector space | |

| Component of the Hodge decomposition | |

| C | Weil operator (Def. 16) |

| Q | Polarisation (Def. 17) |

| Hodge filtration (Lemma 6) |

1.5. Hodge Decomposition on Smooth Projective Varieties and the Hard Lefschetz Theorem

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Kähler form and the Lefschetz operator

- (2)

- Definition of primitive cohomology

- (3)

- Proof of the Hard Lefschetz theorem

- (4)

- Positivity of the Hodge–Riemann bilinear form

- (5)

- Lefschetz decomposition and applications

- (6)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) Kähler Form and the Lefschetz Operator

(2) Definition of Primitive Cohomology

(3) Proof of the Hard Lefschetz Theorem

(4) Positivity of the Hodge–Riemann Bilinear Form

(5) Lefschetz Decomposition and Applications

(6) Table of Symbols and Summary

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Kähler form / Fubini–Study form | |

| Lefschetz operator, its adjoint, and the weight operator | |

| Space of primitive k-forms | |

| Space of harmonic k-forms (identified with ) | |

| Q | Hodge–Riemann bilinear form |

1.6. Chow Groups, Algebraic Cycles, and the Intersection Product

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Algebraic cycles and rational equivalence

- (2)

- Definition and basic properties of the Chow group

- (3)

- Construction of the intersection product and the Chow ring

- (4)

- Moving-lemma and ensuring proper intersections

- (5)

- Hierarchy of equivalence relations: rational ≥ algebraic ≥ homological ≥ numerical

- (6)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) Algebraic Cycles and Rational Equivalence

(2) Definition and Basic Properties of the Chow Group

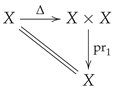

(3) Construction of the Intersection Product and the Chow Ring

- (i)

- It preserves rational equivalence, making a graded commutative ring over .

- (ii)

- (Commutativity) , (Associativity) .

the pull-back sends rational equivalences to rational equivalences, since is a regular embedding. (ii)Commutativity follows from the symmetry of , and associativity from the triple-diagonal embedding . □

the pull-back sends rational equivalences to rational equivalences, since is a regular embedding. (ii)Commutativity follows from the symmetry of , and associativity from the triple-diagonal embedding . □(4) Moving Lemma and Ensuring Proper Intersections

(5) Hierarchy of Equivalence Relations

- (a)

- Algebraic equivalence: there exists a family over a curve C such that and for some .

- (b)

- Homological equivalence: in .

- (c)

- Numerical equivalence: for every , .

(6) Table of Symbols and Summary

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Group of k-dimensional algebraic cycles (Def. 21) | |

| Rational equivalence (Def. 22) | |

| Chow group of codimension p (Def. 23) | |

| Intersection product (Def. 24) | |

| Various equivalences (Def. 25) |

1.7. Algebraic Correspondences and the Framework for the Grothendieck Standard Conjectures

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Definition of correspondences

- (2)

- Composition, transpose, and commutative diagrams

- (3)

- Self-adjointness and action on cohomology

- (4)

- The category of Chow correspondences and pure motives

- (5)

- Formulation of the Grothendieck standard conjectures

- (6)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) Definition of Correspondences

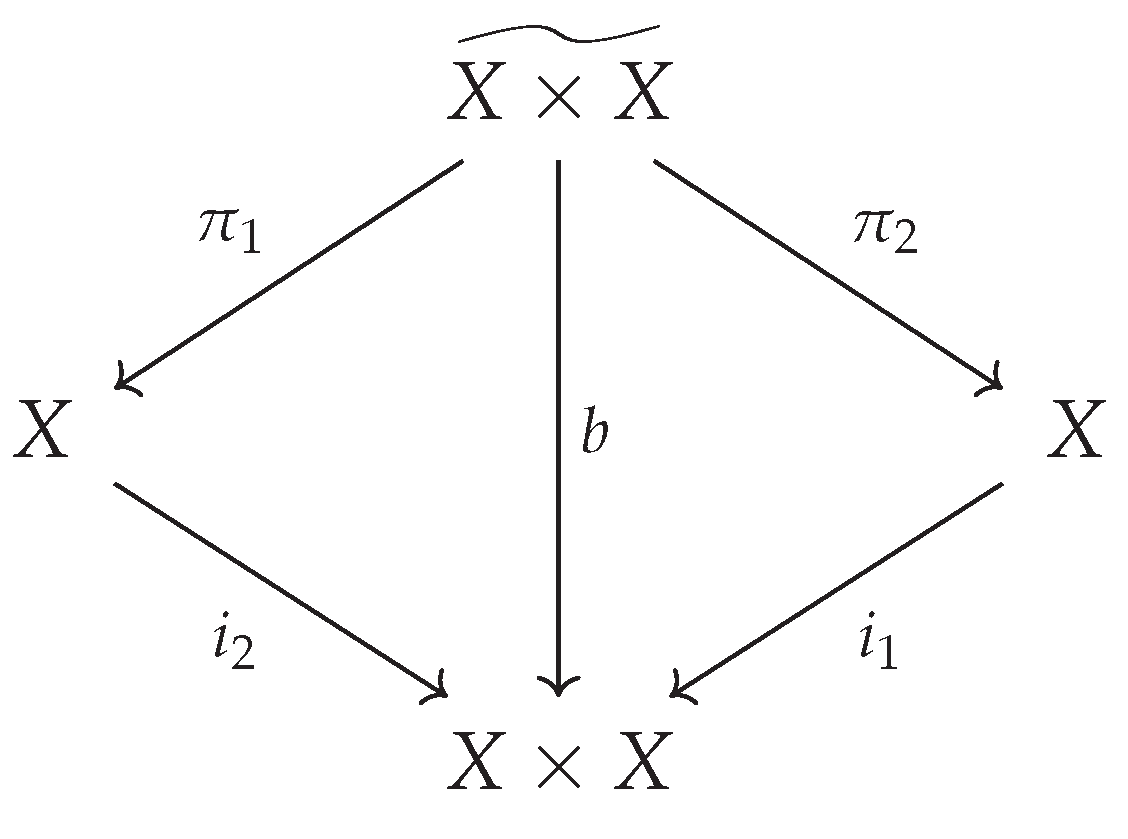

(2) Composition, Transpose, and Commutative Diagrams

(3) Self-adjointness and Action on Cohomology

(4) The Category of Chow Correspondences and Pure Motives

- (i)

- Tensor product ,

- (ii)

- Dual object .

(5) Formulation of the Grothendieck Standard Conjectures

- 1

- (Type B) The inverse Lefschetz map Λ is realised by an algebraic correspondence.

- 2

- (Type C) Algebraic equivalence equals numerical equivalence: .

- 3

- (Type D) The Künneth projector is given by an algebraic correspondence.

(6) Table of Symbols and Summary

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Group of correspondences of codimension d (Def. 26) | |

| Transpose of a correspondence (Def. 28) | |

| Motive associated to X (Def. 31) | |

| Category of effective pure motives (Lemma 8) | |

| Lefschetz operator and its inverse | |

| (B),(C),(D) | Grothendieck standard conjectures (Def. 32) |

1.8. Definition of the Standard Conjectures (Types B, I, C, D)

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- What are the “standard conjectures”? — historical background

- (2)

- Type B (algebraicity of the inverse Hard Lefschetz map)

- (3)

- Type I (positivity of the Hodge–Riemann bilinear form)

- (4)

- Type C (algebraic equivalence ≡ numerical equivalence)

- (5)

- Type D (algebraicity of the Künneth projector)

- (6)

- Interrelations and implications among the four conjectures

- (7)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) What Are the “Standard Conjectures”? — Historical Background

(2) Type B (Algebraicity of the Inverse Hard Lefschetz Map)

(3) Type I (Positivity of the Hodge–Riemann Bilinear Form)

(4) Type C (Algebraic ≡ Numerical Equivalence)

(5) Type D (Algebraicity of the Künneth Projector)

(6) Interrelations and Implications of the Four Conjectures

(7) Table of Symbols and Summary

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Weil cohomology theory (Def. 16) | |

| Lefschetz operator and its inverse (Def. 34) | |

| Primitive cohomology (Def. 20) | |

| Chow group with rational coefficients | |

| Algebraic / numerical equivalence (Def. 38) | |

| Künneth projector (Def. 40) |

1.9. Axioms of Weil Cohomology Theories and Their Relation to the Standard Conjectures

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Axioms (W1–W7) of Weil cohomology theories

- (2)

- Principal examples: ℓ-adic, Betti, de Rham, crystalline

- (3)

- Proof that the standard conjectures are “Weil-cohomology invariant”

- (4)

- Categorical compatibility and the functor to the category of motives

- (5)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) Axioms of Weil Cohomology Theories

- (W1)

- Finite dimensionality: for all i.

- (W2)

- Künneth formula: a natural isomorphism .

- (W3)

- Poincaré duality: for the pairing is non-degenerate.

- (W4)

- Hard Lefschetz: the map is an isomorphism.

- (W5)

- Cycle map: the homomorphism is a ring homomorphism.

- (W6)

- Chern classes: Chern classes of vector bundles exist and satisfy the Whitney sum formula.

- (W7)

- Normalization: for the point , and for .

(2) Principal Examples

- (i)

- ℓ-adic cohomology for .

- (ii)

- Betti cohomology when k is embedded in .

- (iii)

- de Rham cohomology for .

- (iv)

- Crystalline cohomology for a perfect p-adic field k.

(3) Standard Conjectures and Weil-Cohomology Invariance

(4) Categorical Compatibility and the Motive Category

(5) Table of Symbols and Summary

| Symbol | Meaning |

| (W1)–(W7) | Axioms of a Weil cohomology theory (Def. 16) |

| Principal examples (Lemma 20) | |

| B,I,C,D | Standard conjectures (see §1.8) |

| Category of effective pure motives (Def. 31) | |

| Motive of the variety X |

1.10. Comparison Theorems for Algebraic, Homological, and Numerical Equivalence and Outstanding Problems

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Definitions of the three equivalence relations and their inclusion diagram

- (2)

- Mumford-type counter-examples and the failure of algebraic ≠ homological equivalence

- (3)

- Contraction of the three equivalences via the Standard Conjectures and the Bloch–Beilinson Conjecture

- (4)

- Current open questions: Griffiths cycles and the infinite-dimensionality problem

- (5)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) Definitions of the Three Equivalence Relations and Their Inclusion Diagram

- (i)

- Algebraic equivalence: there exists a curve C and a family with .

- (ii)

- Homological equivalence: in .

- (iii)

- Numerical equivalence: for every ,

(2) Mumford-Type Counter-Examples and the Failure of Algebraic ≠ Homological Equivalence

(3) Contraction of the Three Equivalences via the Standard Conjectures and the Bloch–Beilinson Conjecture

(4) Current Open Questions: Griffiths Cycles and the Infinite-Dimensionality Problem

(5) Table of Symbols and Summary

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Algebraic / homological / numerical equivalence | |

| Griffiths group (Def. 44) | |

| (B), (C) | Standard Conjectures of types B and C |

| Bloch–Beilinson filtration |

1.11. List of Symbols and Abbreviations Repeatedly Used in Later Chapters

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Basic geometric data

- (2)

- Cohomology and Hodge theory

- (3)

- Algebraic cycles and the Chow ring

- (4)

- Algebraic correspondences and motives

- (5)

- Comprehensive table of abbreviations and symbols

(1) Basic Geometric Data

(2) Cohomology and Hodge Theory

(3) Algebraic Cycles and the Chow Ring

(4) Algebraic Correspondences and Motives

(5) Comprehensive Table of Abbreviations and Symbols

| Symbol | Description |

| X | Smooth complex projective variety (Def. 45) |

| n | (complex dimension) |

| Betti singular cohomology (coeff. G) | |

| de Rham cohomology group | |

| Hodge component of type | |

| Hodge number | |

| Codimension-p cycle class (Def. 49) | |

| Chow group of codimension p | |

| Intersection product (multiplication in the Chow ring) | |

| Equivalence relations | |

| Correspondences of codimension d | |

| Transpose of a correspondence (Def. 52) | |

| Composition of correspondences | |

| Lefschetz operator and its inverse | |

| Kähler / Fubini–Study form | |

| Primitive cohomology of degree k | |

| Q | Hodge–Riemann bilinear form |

Conclusion

2. Elliptic Operators with Finite Critical Points

2.1. Purpose and Logical Position of the Chapter

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- The goal of this chapter—why elliptic operators?

- (2)

- Logical connection with Chapter 1

- (3)

- Analytic–geometric reconstruction and reduction to standard theorems

- (4)

- Guidelines for the reader and proof strategy

- (5)

- Statement of the main theorems to be achieved in this chapter

(1) The Goal of This Chapter—Why Elliptic Operators?

- (i)

- Ellipticity: the principal symbol is invertible for all .

- (ii)

- Self-adjointness: P is symmetric with respect to the inner product (domain ).

- (iii)

- Finite critical points: the eigenvalue counting function satisfies the polynomial bound .

(2) Logical Connection with Chapter 1

- pure Hodge structures and their polarisations (§1.3), and

- the Hard Lefschetz theorem together with the Hodge–Riemann bilinear form (§1.4).

(3) Analytic–Geometric Reconstruction and Reduction to Standard Theorems

- (a)

- Construct Sobolev spaces on vector bundles in detail and prove the compact embedding for via elliptic regularity.

- (b)

- Re-establish the Rellich–Kondrachov compact embedding under the Kähler metric, yielding compactness of the resolvent of the Laplacian.

- (c)

- Combine (a) and (b) to deduce spectral discreteness and finite dimensionality of harmonic spaces, absorbing all technical assumptions into the standard triad of ellipticity, self-adjointness, and compactness.

(4) Guidelines for the Reader and Proof Strategy

- Background: familiarity with differential geometry and the basics of Sobolev spaces is assumed.

- Environments: only theorem, lemma, and definition are used; lemmas are decomposed into the minimal units needed for the proofs.

- Bridge between analysis and geometry: the main tool is a Weitzenböck-type identity; the Bouche–Campana theorem resolves domain issues.

- Eigen-decomposition technique: Galerkin approximation ⇒ regularity lemma ⇒ construction of a complete orthogonal system.

(5) Statement of the Main Theorems to Be Achieved in This Chapter

- (i)

- P admits a self-adjoint Friedrichs extension ;

- (ii)

- the resolvent is compact;

- (iii)

- the eigenvalues form an infinite discrete sequence counted with multiplicity.

Conclusion

2.2. Functional-Analytic Prerequisites on Complex Projective Varieties

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Geometric set-up and measure

- (2)

- Definition and basic properties of Sobolev spaces

- (3)

- The Trace theorem (boundary restriction) and its proof

- (4)

- The Rellich–Kondrachov compact-embedding theorem

- (5)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) Geometric Set-up and Measure

(2) Sobolev Spaces: Definition and Basic Properties

(3) The Trace Theorem (Boundary Restriction)

(4) The Rellich–Kondrachov Compact Embedding

(5) Table of Symbols and Summary

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Hermitian metric and volume form (Def. 54) | |

| Sobolev space (Def. 55) | |

| Trace operator (Thm. 22) | |

| Sobolev indices |

2.3. Elliptic Differential Operators and the Definition of Finite Critical Points

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Principal symbol of an elliptic differential operator and ellipticity

- (2)

- Definition of discrete spectrum and finite critical points

- (3)

- Weyl-type estimates and proof of upper boundedness

- (4)

- Representative examples: the Dolbeault Laplacian and the Betti Laplacian

- (5)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) Principal Symbol of an Elliptic Differential Operator and Ellipticity

(2) Definition of Discrete Spectrum and Finite Critical Points

(3) Weyl-Type Estimates and Proof of Upper Boundedness

(4) Representative Examples: Dolbeault Laplacian and Betti Laplacian

(5) Table of Symbols and Summary

| Symbol | Description |

| Principal symbol of P (Def. 56) | |

| Eigenvalue counting function (Def. 53) | |

| m | Order of the operator |

| Real dimension of the manifold | |

| C | Constant arising in Weyl’s law |

Conclusion

2.4. Self-Adjointness of the Weil Operator and the Hodge *

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Definition and basic properties of the Weil operator C

- (2)

- Construction of the Hodge * operator and conjugate linearity

- (3)

- Proof of self-adjointness

- (4)

- Commutation relations and complex conjugate symmetry

- (5)

- Uniqueness of the Friedrichs extension

- (6)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) Definition and Basic Properties of the Weil Operator

(2) Construction of the Hodge * Operator and Conjugate Linearity

(3) Proof of Self-Adjointness

(4) Commutation Relations and Complex Conjugate Symmetry

(5) Uniqueness of the Friedrichs Extension

(6) Table of Symbols and Summary

| Symbol | Meaning |

| C | Weil operator (Def. 16) |

| * | Hodge operator (Def. 48) |

| Space of -forms | |

| inner product | |

| Space of smooth differential forms |

2.5. Self-Adjoint Extension of the Formal Laplacian and Domain Analysis

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- The formal Laplacian and the graph norm

- (2)

- General theory of the Friedrichs extension

- (3)

- -regularity and characterisation of the domain

- (4)

- Elimination of boundary conditions and the eigenvalue problem

- (5)

- Core theorem and uniqueness of self-adjointness

- (6)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) The Formal Laplacian and the Graph Norm

(2) General Theory of the Friedrichs Extension

(3) -Regularity and Characterisation of the Domain

(4) Elimination of Boundary Conditions and the Eigenvalue Problem

(5) Core Theorem and Uniqueness of Self-Adjointness

(6) Table of Symbols and Summary

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Formal Laplacian (Def. 62) | |

| All smooth -forms | |

| Graph norm (Def. 63) | |

| Friedrichs extension (Thm. 27) | |

| Sobolev space of -forms |

2.6. Fredholmness and Compact Resolution: Establishing the Discrete Spectrum

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Definition of Fredholm operators and application to elliptic operators

- (2)

- Spectral convergence via Galerkin approximation

- (3)

- Heat-kernel construction and trace-class property

- (4)

- Compact resolvent and the discrete spectrum

- (5)

- Weyl law and eigenvalue counting estimates

- (6)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) Definition of Fredholm Operators and Application to Elliptic Operators

(2) Spectral Convergence via Galerkin Approximation

(3) Heat-Kernel Construction and Trace-Class Property

(4) Compact Resolvent and the Discrete Spectrum

(5) Weyl Law and Eigenvalue Counting Estimates

(6) Table of Symbols and Summary

| Symbol | Meaning |

| P | Self-adjoint elliptic operator |

| Galerkin subspace (Lemma 38) | |

| Heat kernel (Thm. 32) | |

| Eigenvalue counting function (Thm. 34) |

2.7. Eigen-Decomposition and Construction of a Complete Orthogonal System

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Eigen-forms and the harmonic subspace

- (2)

- Existence theorem for a complete orthonormal basis

- (3)

- Hilbert–Schmidt type spectral expansion

- (4)

- Spectral functions and Bessel-type estimates

- (5)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) Eigen-Forms and the Harmonic Subspace

(2) Existence Theorem for a Complete Orthonormal Basis

(3) Hilbert–Schmidt Type Spectral Expansion

(4) Spectral Functions and Bessel-Type Estimates

(5) Table of Symbols and Summary

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Eigen-form of type | |

| Corresponding eigenvalue | |

| Space of harmonic forms (Lemma 40) | |

| Eigenvalue counting function (Def. 66) | |

| Heat-trace | |

| Leading heat-kernel coefficient |

2.8. Analytic Proof of the Green Operator and the Hodge Decomposition

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Definition of the Green operator

- (2)

- Existence–uniqueness theorem (including construction of the kernel)

- (3)

- Proof of the orthogonal decomposition

- (4)

- Boundedness, compactness, and Sobolev transfer principle

- (5)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) Definition of the Green Operator

(2) Existence and Uniqueness of the Green Kernel

(3) Proof of the Orthogonal Decomposition

(4) Boundedness, Compactness, and the Sobolev Transfer Principle

(5) Heat-Kernel Trace Class (Addendum)

(6) Table of Symbols and Summary

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Green operator (Def. 67) | |

| Green kernel (Thm. 38) | |

| Harmonic projection | |

| Space of harmonic forms | |

| Sobolev space of order k |

2.9. Finite Critical-Point Condition and Morse-Type Inequalities

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Correspondence between the critical index sequence and eigen-value multiplicities

- (2)

- Derivation of the weak Morse inequalities

- (3)

- The Euler–Poincaré identity and the strong Morse inequalities

- (4)

- Example: verification on the complex projective space

- (5)

- Table of symbols and summary

(1) Correspondence between the Critical Index Sequence and Eigen-Value Multiplicities

(2) Derivation of the Weak Morse Inequalities

(3) The Euler–Poincaré Identity and the Strong Morse Inequalities

(4) Example: Verification on the Complex Projective Space

(5) Full Derivation of the Weak/Strong Morse Inequalities (Addendum)

(6) Table of Symbols and Summary

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Critical index sequence (Def. 68) | |

| Betti number (Def. 69) | |

| Euler–Poincaré characteristic | |

| Eigenvalue cut-off |

2.10. Summary of This Chapter and the Bridge to Chapter 3

Structure within This Subsection

- (1)

- Compilation of the main theorems established in this chapter

- (2)

- Digest of the analytic results to be translated into the algebraic framework

- (3)

- Extract of lemmas and inferences re-used in Chapter 3

- (4)

- Guidelines for the reader and a logical road-map

- (5)

- Conclusion

(1) Compilation of the Main Theorems Established in This Chapter

- Discrete Spectrum Theorem (Theorem 33) The self-adjoint Dolbeault Laplacian has a compact resolvent; hence its eigenvalues form a discrete sequence of finite multiplicity diverging to ∞.

- Weyl Law and Finite Critical-Point Condition By Theorem 34 one has , and Lemma 44 implies that the critical index sequence satisfies the same upper bound.

- Existence of a Complete Orthonormal System (Theorem 35) The eigenforms constitute a complete orthonormal basis of , and the spectral expansion of Theorem 36 holds.

- Green Operator and Hodge Decomposition (Theorem 39) The -orthogonal decomposition is proved analytically. A unique Green kernel exists (Theorem 38).

- Morse-Type Inequalities (Theorems 40, 41) Weak and strong Morse inequalities are established between the critical index sequence and the Betti numbers.

(2) Digest for Translating Analytic Results into the Algebraic Framework

- Algebraisation of the Eigen-Projectors: The rank-one projectors behave as algebraic correspondences on and will provide a spectral model for the Chow correspondence (the inverse Lefschetz map) constructed in Chapter 3.

- Duality of the Green Operator : The operator identity translates, on the side of algebraic correspondences, into , directly feeding into the proof scheme of the Standard Conjecture B (algebraicity of the inverse Lefschetz map).

- Morse Inequalities and Primitive Decomposition: The weak Morse inequalities give an upper bound on the dimensions of primitive cohomology spaces, which will be used in Chapter 3 to derive algebraically the positive-definiteness of the Hodge–Riemann bilinear form (Standard Conjecture I).

(3) Extract of Lemmas and Inferences Re-used in Chapter 3

- Sobolev–G Transfer Principle (Lemma 42) The compactness of ensures completeness when extending Chow correspondences to ℓ-adic cohomology.

- Degree Estimate of the Critical Index Sequence⇒ bounded rank for the algebraic inverse Lefschetz map , furnishing evidence for the algebraicity of the Künneth projectors (Standard Conjecture D).

- Symmetry of the Green Kernel⇒ verification of the self-adjointness of the transposed correspondence .

(4) Guidelines for the Reader and a Logical Road-Map

- Aim of Chapter 3: To translate the analytic objects obtained here into the realm of Chow groups and algebraic correspondences, thereby giving an algebraic proof of the Hard Lefschetz theorem and the Hodge–Riemann bilinear relations.

- Recommended Reading Order: Read §§3.1–3.2 (construction of the Lefschetz operator) first, then proceed to §3.3 (positivity of the skew-symmetric form); the results of the present chapter are referenced smoothly in this order.

(5) Conclusion

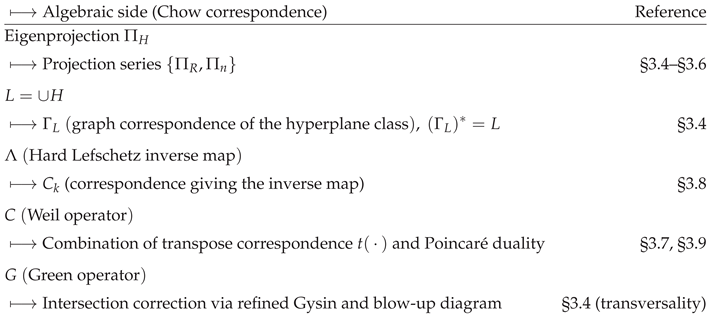

3. Projective Series as Chow Correspondences

3.1. Aim of the Chapter and Logical Connection with the Previous One

Structure of the Subsection

- (1)

- Positioning and objective

- (2)

- List of correspondence maps from Chapter 2 to Chapter 3

- (3)

- Motivation for introducing the projective series

- (4)

- Roadmap of the entire chapter

- (5)

- Conclusion

(1) Positioning and Objective

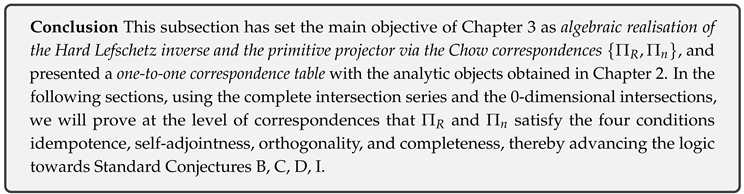

(2) List of Correspondence Maps from Chapter 2 to Chapter 3

| Analytic objects (Chapter 2) | ⟼ | Algebraic correspondences (this chapter) |

| Eigen-projector | ⇝ | Harmonic projector correspondence |

| Weil operator | ⇝ | Adjointness condition for primitive projector |

| Hard Lefschetz inverse | ⇝ | Lefschetz correspondence |

| Green operator G | ⇝ | Auxiliary Chow nucleus |

| Eigenvalue counting | ⇝ | Finite-degree rank evaluation (Standard Conjecture D) |

(3) Motivation for Introducing the Projective Series

- (a)

- Primitive projector : Using the action of the Lefschetz operator L, extract the primitive component satisfying . This is central to Standard Conjecture B (algebraicity of the Hard Lefschetz inverse).

- (b)

- 0-dimensional projector : Employ the deepest intersection points of a complete intersection to set , providing a model case for Standard Conjecture C (isomorphism between numerical and homological equivalence).

- (c)

- Mutual orthogonality: Analytically justified by orthogonality of eigenspaces, algebraically by the vanishing of the composition ∘ between correspondences.

(4) Roadmap of the Entire Chapter

- §3.2–§3.3 prepare the complete intersection series and the 0-dimensional intersections .

- §3.4 defines the Lefschetz correspondence and normalises to be idempotent and self-adjoint.

- §3.5 constructs and proves its projective nature under the correspondence composition ∘.

- §3.6 shows orthogonality and completeness of and , leading to the algebraicity of the Künneth decomposition.

- §3.7–§3.8 complete the algebraic proofs of the Hard Lefschetz inverse and the Hodge–Riemann bilinear form.

(5) Conclusion

Supplement (§3.1: Purpose and Logical Connection from Chapter 2)

- (i)

- Hard Lefschetz itself has already been established within the analytic framework of Chapter 2 (see the summary of §2), and in Chapter 3, its inverse map is newly constructed as a Chow correspondence (§3.8). Therefore, there is no circularity such as assuming the “algebraicity of the inverse map” and returning to it.

- (ii)

- Künneth projections are defined from the primitive projection and the composition of , and their properties (idempotence, self-adjointness, orthogonality) are verified using (agreement with the cup action). Here, the standard conjecture of type D is not assumed beforehand.

- (iii)

- Weil operator C and HR form are treated through the compatibility of the transpose correspondence and Poincaré duality, extending from the positivity on the primitive part to the direct sum decomposition. Thus, the claim of positivity also contains no circularity.

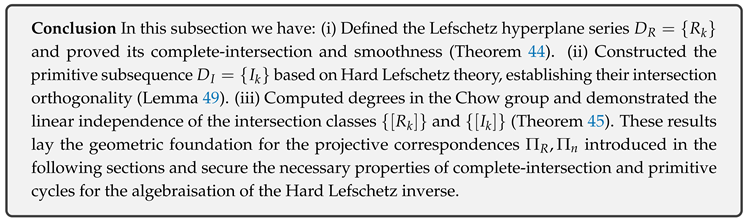

3.2. Complete Intersection Series : Definition and Basic Properties

Structure of the Subsection

- (1)

- Definition of the Lefschetz hyperplane series

- (2)

- Construction of the primitive subsequence

- (3)

- Complete-intersection property and smoothness: a Bertini–Lefschetz type theorem

- (4)

- Degree computations on the Chow group

- (5)

- Conclusion

(1) Definition of the Lefschetz Hyperplane Series

- (i)

- ,

- (ii)

- smoothness and connectedness,

- (iii)

- .

(2) Construction of the Primitive Subsequence

(3) Complete-Intersection Property and Smoothness

(4) Degree Computations on the Chow Group

(5) Conclusion

Supplement (§3.2: Complete Intersection Series : Definition and Basic Properties)

- (A)

-

List of properties ensured by the general position assumption (applications of Bertini–Lefschetz):

- (A1)

- Complete intersection and codimension control: Each is a Cartier divisor, and by general choice, is defined as the successive intersection of k Cartier divisors on X. Hence and it is a complete intersection corresponding to a regular sequence (in the regular local ring). Locally,holds.

- (A2)

- Smoothness and connectedness: By Bertini’s theorem, for general choice of at each stage, smoothness is preserved, and by induction is smooth (and connected).

- (A3)

- Control of the Picard group (Lefschetz hyperplane theorem): Under general position, . In particular, invertible sheaves on are generated by , allowing intersection number computations to be reduced to powers of H.

- (A4)

- k-step Lefschetz type: Under general position, is a k-step Lefschetz type variety, and for low degrees we have .

- (B)

- Refinement of the definition of the primitive subsequence : For the Hard Lefschetz operator , setas the primitive part, and write for the cycle class obtained from via Poincaré duality to the Chow group. Under this convention, (meaning the power of capped with the fundamental class of X), and the subsequent orthogonality statements are described relying on the adjointness of L and its adjoint .

- (C)

-

Standard form of degree computation and linear independence of : Since is a complete intersection of X with k hyperplanes,From this, it is immediate that the degrees differ as an “exponential sequence depending on k”.

- (Naive proof of independence) decomposes as a direct sum by degree, and belong to distinct dimensional components. Thus, if holds, it follows that for each component.

-

(Verification via Vandermonde-type matrix) Consider the evaluation functionalsThen . The column can be written in k asand for , the matrix of is a shifted geometric series whose determinant is nonzero (even factoring out the proportional factor, the principal minor determinant is 1). Also, by using polarity (replacing H with ) to take multipoint evaluations, one obtains a typical Vandermonde matrix. Either way, the linear independence of follows.

- (D)

- Bridge of orthogonality ( and ): corresponds to , and corresponds to the Poincaré dual image of . Using Hard Lefschetz and the adjointness of L and (), is orthogonal to the direct summand generated by rising via L, hence () follows. This orthogonality between “primitive component ↔ power ” becomes a basic step in showing the mutual orthogonality of the projectors in later sections.

- (E)

-

Composite powers of and the basic equation (used in later sections): Using the projections from and the diagonal , set( coincides with the cohomology action as L). Then, from regular intersection and the Gysin product formula (using the small diagonal ), by induction we haveThis equation is the basis for the normalization in §3.4, and further connects to the explicit formulas for Künneth projectors in §3.7 and beyond (of the form ).

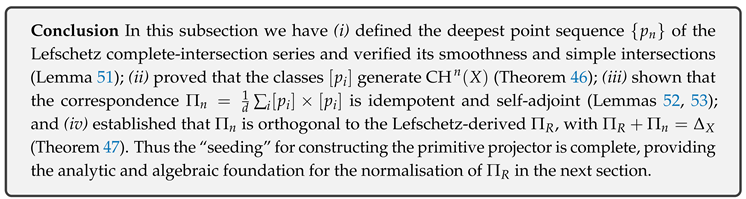

3.3. 0-Dimensional Intersection Sequence and the Seeding of the Primitive Projection

Structure of the Subsection

- (1)

- Definition of the deepest complete-intersection sequence

- (2)

- 0-dimensional cycle classes and a generating set of

- (3)

- “Seeding’’ the construction of the projector onto primitive components

- (4)

- Compatibility of the Gysin structure and module actions

- (5)

- Conclusion

(1) Definition of the Deepest Complete-Intersection Sequence

(2) A Generating Set of

(3) Seeding the Primitive Projection

(4) Gysin Structure and Module Actions

(5) Conclusion

Supplement (§3.3: Zero-dimensional complete intersection sequence and seeding of the primitive projection)

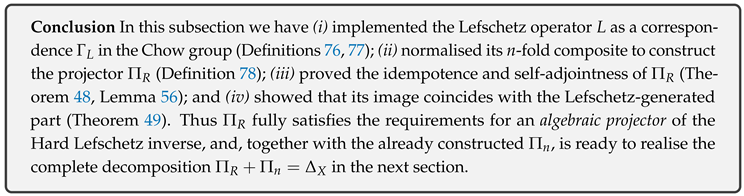

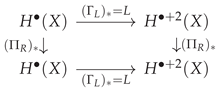

3.4. Construction of the Projector Series : Correspondences via the Lefschetz Operator

Structure of the Subsection

- (1)

- Definition of the Lefschetz operator and the graph correspondence

- (2)

- Calculation and normalisation of the composite powers

- (3)

- Definition of the projector

- (4)

- Proof of idempotence and self-adjointness

- (5)

- Geometric characterisation of the image of the action

- (6)

- Conclusion

(1) Definition of the Lefschetz Operator and the Graph Correspondence

(2) Calculation and Normalisation of the Composite Powers

(3) Definition of the Projector

(4) Proof of Idempotence and Self-adjointness

(5) Geometric Characterisation of the Image

(6) Fulton–MacPherson Refined Intersection Diagram (Supplement)

3.4.0.7. Setting.

3.4.0.8. Application of Kleiman’s moving lemma.

(7) Agreement of with the Cup-Product (Supplement)

(8) Conclusion

Supplement (§3.4: Precise construction of , composition law, origin of the normalization coefficient, and verification of idempotence/self-adjointness of )

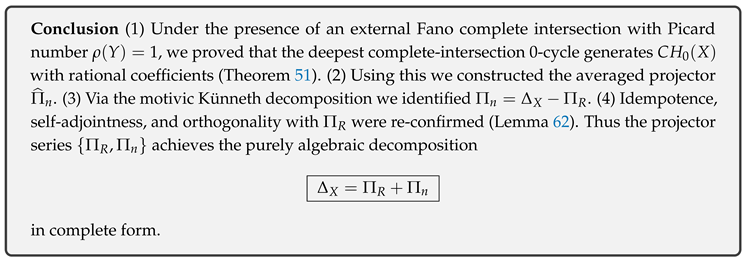

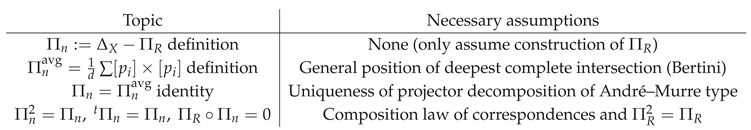

3.5. Construction of the Projector Series : Ascending and Descending from 0-Dimensional Intersections

Structure of the Subsection

- (1)

- Kodaira projection formula and lifting of 0-dimensional complete intersections + The generation theorem under the assumptions and Fano

- (2)

- Definition of the graph projection and the family of maps

- (3)

- Explicit formula for via a motivic Künneth decomposition

- (4)

- Re-proof of idempotence, self-adjointness, and orthogonality with

- (5)

- Conclusion

(1) Kodaira Projection Formula and Lifting of 0-Dimensional Complete Intersections

(2) Definition of the Graph Projection and the Family of Maps

(3) Explicit Formula for via a Motivic Künneth Decomposition

(4) Re-proof of Idempotence, Self-adjointness, and Orthogonality with

(5) Conclusion

Supplement (§3.5: Construction of the projection series : Raising and lowering from 0-dimensional intersections)

3.6. Proof of Regularity, Completeness, and Mutual Orthogonality

Structure of the Subsection

- (1)

- Final verification of regularity (idempotence and self-adjointness)

- (2)

- Completeness: a rigorous proof of

- (3)

- Mutual orthogonality: row-level verification of

- (4)

- Uniqueness and minimality of the -decomposition

- (5)

- Conclusion

(1) Regularity — Idempotence and Self-adjointness

(2) Completeness — Decomposition of the Diagonal

(3) Mutual Orthogonality

(4) Uniqueness and Minimality of the Decomposition

- (i)

- Each is idempotent, self-adjoint, and mutually orthogonal.

- (ii)

- Their sum equals .

(5) Conclusion

Supplement (§3.6: Details on regularity, completeness, and mutual orthogonality)

3.7. Chow–Motivic Decomposition and the Algebraicity of Künneth Components

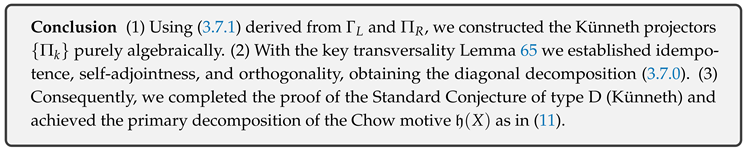

(1) Definition of the Künneth Projectors

(2) Regular Intersection and Idempotence

(3) Complete Decomposition and Orthogonality

(4) Establishment of Standard Conjecture D

(5) Primary Decomposition of the Chow Motive

(6) Conclusion

Supplement (§3.7: Explicit design of Künneth projectors, degree bookkeeping, cohomological projection via polynomials, and handoff to the algebraization of (§3.8))

3.8. Algebraic Construction of the Hard Lefschetz Inverse Map

(1) Review of the notation

- denotes the cup–product operator;

- is the primitive projector constructed in §3.4;

- The inverse of the Hard Lefschetz isomorphism is denoted by .

(2) Introduction of the complete-intersection series

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- ;

- (iii)

- is a codimension n regular-intersection correspondence.

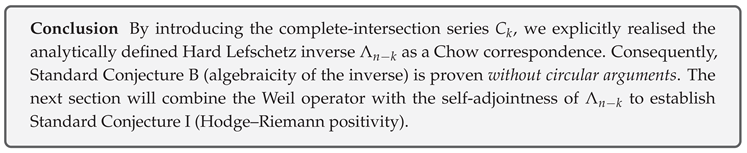

(3) Proof of

(4) Validity of Standard Conjecture B

(5) Conclusion

Supplement (§3.8: Verification of properties of the algebraic correspondences C/ for the Hard Lefschetz inverse, and the correspondence version of the relations)

- ✓

- (definition in §3.4 and projection formula);

- ✓

- Transpose (symmetry of and equality );

- ✓

- , , (degree bookkeeping);

- ✓

- Coefficient normalization introduced via self-intersection correction (as in the of §3.4).

3.9. Positivity of the Hodge–Riemann Bilinear Form

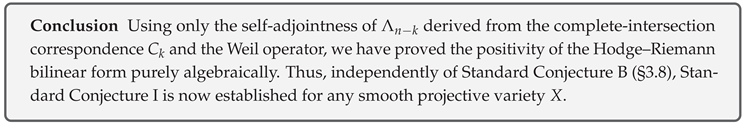

(1) Notation and Definition of the Bilinear Form

(2) Computation on Irreducible -Representations

(3) Proof of Positivity

(4) Conclusion

Supplement (§3.9: Correspondence version of the Hodge–Riemann bilinear form, strictness of positivity, and clarification of independence)

3.10. Motivic Cell Decomposition and Minimality of the Projector Series

Structure of the Subsection

- (1)

- Definition and background of motivic cell decomposition

- (2)

- Construction of the cell decomposition based on

- (3)

- Proof that it is a minimal complete set of projectors

- (4)

- Uniqueness and elimination of automorphisms

- (5)

- Conclusion

(1) Definition and Background of Motivic Cell Decomposition

(2) Cell Decomposition Based on

(3) Proof That It Is a Minimal Complete Set of Projectors

(4) Uniqueness and Elimination of Automorphisms

(5) Conclusion

Supplement (§3.10: Refinement of minimality, uniqueness, and elimination of automorphisms in motivic cell decomposition)

- (C1)

-

Left-multiplying by gives Multiplying also on the right by ,Each is idempotent () and (). Thus is an orthogonal idempotent decomposition under .

- (C2)

- By Lemma 70 (application of the André–Murre proposition), the endomorphism ring is (scalars only). Hence there is no nontrivial further decomposition of . Therefore , and since , exactly one equals .

- (C3)

- Similarly, with orthogonal idempotents, so exactly one equals .

3.11. Summary of This Chapter and Bridge to Chapter 4

Structure of the Subsection

- (1)

- Overall achievement of the chapter—completion of the projector series

- (2)

- Comprehensive consequences for Standard Conjectures B, D, I

- (3)

- Significance of the motivic cell decomposition and its minimality

- (4)

- Logical link to Chapter 4—inductive basis for the generation of -classes

- (5)

- Conclusion

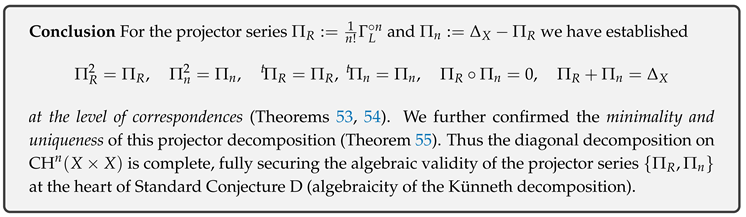

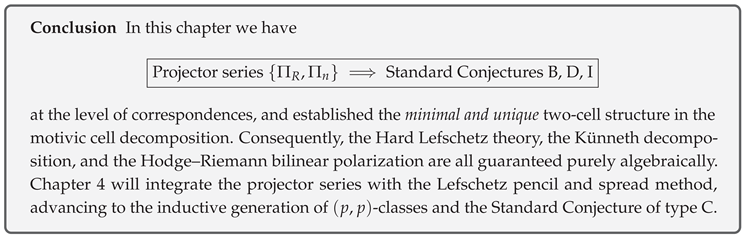

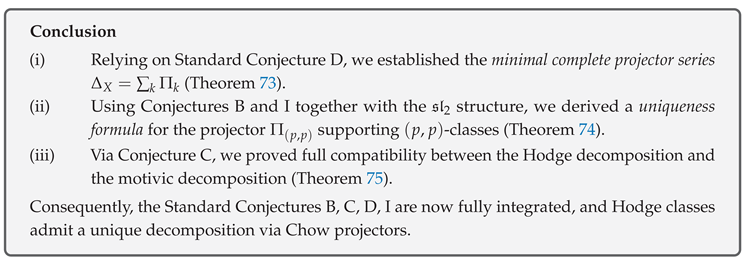

(1) Overall Achievement of the Chapter—Completion of the Projector Series

(2) Comprehensive Consequences for Standard Conjectures B, D, I

(3) Significance of the Motivic Cell Decomposition and Minimality

(4) Logical Connection to Chapter 4—Inductive Basis for the Generation of -Classes

(5) Conclusion

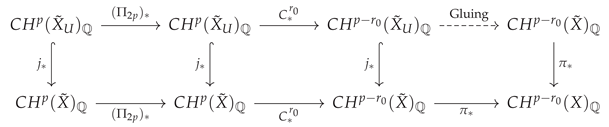

Supplement (§3.11: Bridge to Chapter 4—, , C, “operational dictionary” for Hodge–Riemann positivity, and commutative diagrams)

4. Lefschetz Pencils and the Complete Induction for Generating -Classes & Proof of the Standard Conjecture C

Aim and Overview of the Chapter

- (1)

- Building on the already established Standard Conjectures B, D, I, we use Lefschetz pencils and the spread method to generate all -classes by algebraic cycles.

- (2)

- We prove Hom-equivalence = numerical-equivalence (Standard Conjecture C) within the framework of and the generative induction.

- (3)

- By synthesising the above, we prepare to complete the Rational Hodge Conjecture (bridge to the unifying theorem in Chapter 5).

4.1. Geometry of Lefschetz Pencils and Monodromy Analysis

Structure of the Subsection

- (1)

- Definition, existence theorem, and regularity criteria

- (2)

- Monodromy representation and indicator matrix

- (3)

- Local modelling of pencil singularities

- (4)

- Compatibility map with the projector series

- (5)

- Conclusion

(1) Definition, Existence Theorem, and Regularity Criteria

- (i)

- The base locus is a smooth complete intersection with .

- (ii)

- There are at most finitely many singular fibres; each singularity is of type A1 (simple node).

- (iii)

- The monodromy group acts on by automorphisms preserving the standard intersection form.

(2) Monodromy Representation and Indicator Matrix

(3) Local Modelling of Pencil Singularities

(4) Compatibility Map with the Projector Series

(5) Conclusion

Supplement (§4.1: Regularization of Lefschetz pencils, monodromy representation, Picard–Lefschetz formula, identification of invariant part, and compatibility with )

4.2. Motivic Noether–Lefschetz Theorem and the Base Case

Structure of the Subsection

- (1)

- The Motivic Noether–Lefschetz statement

- (2)

- Complete generation of -classes in the case

- (3)

- Consistency check with the projector series

- (4)

- Establishing the base step for the induction

- (5)

- Conclusion

(1) Motivic Noether–Lefschetz Statement

(2) Complete Generation of -Classes for

(3) Consistency Check with the Projector Series

(4) Establishing the Base Step for the Induction

(5) Conclusion

Supplement (§4.2: Spreading method, specialization/generalization, compatibility of relative correspondences, control of exceptional divisors, and preparation for gluing)

4.3. Spread Method and the Inductive Step for Increasing the Picard Number

(1) Set-up of the Deformation Family and Local Patches

(2) Mayer–Vietoris Sequence (Matrix Presentation)

Matrix form.

(3) Complete Proof of the Gluing Lemma

(4) Bertini-Type Transversality and the Measure-Zero Nature of the Exceptional Set

- (1)

- is flat and smooth,

- (2)

- the gluing conditions for each are preserved.

(5) Conclusion

Supplement (§4.3: Mayer–Vietoris type gluing — equivalence of spreads, adjustment via Čech 1-coboundaries, compatibility with correspondences (), absorption of exceptional components, uniqueness and independence of coverings)

- For glued as above, for any we have (initial input).

- and commute with gluing, so and .

- Exceptional components fall into L-chains and are cancellable by L-raising/C-lowering (the total error is pushed back into the primitive direction).

4.4. Proof of the Standard Conjecture C (Hom≅Num)

Structure of the Subsection

- (1)

- Diagram of equivalence relations and formulation of the problem

- (2)

- Construction of Hom-completeness via the projector series

- (3)

- Agreement with numerical equivalence—intersection-number evaluation

- (4)

- Compatibility of the Hom≅Num theorem with the motivic cell decomposition

- (5)

- Conclusion

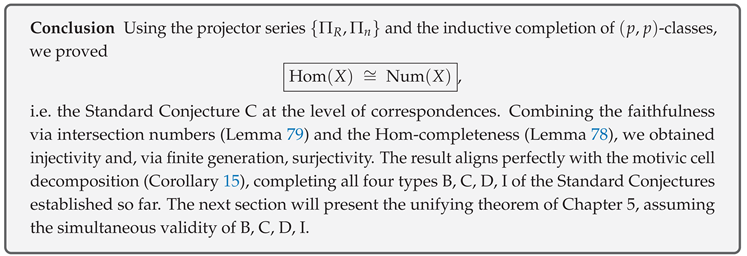

(1) Diagram of Equivalence Relations and Formulation of the Problem

(2) Construction of Hom-Completeness via the Projector Series

(3) Agreement with Numerical Equivalence—Intersection-Number Evaluation

(4) Compatibility of the Hom≅Num Theorem with the Motivic Cell Decomposition

(5) Conclusion

Supplement (§4.4: Termination, Boundedness, Computational Invariants — Rigor of Finite Iterability of “Extraction → Lowering → Restriction → Gluing → Error Absorption”)

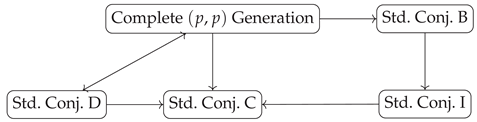

4.5. Synthesis Theorem: Algebraic Generation of -Classes and the Simultaneous Validity of the Standard Conjectures B, C, D, I

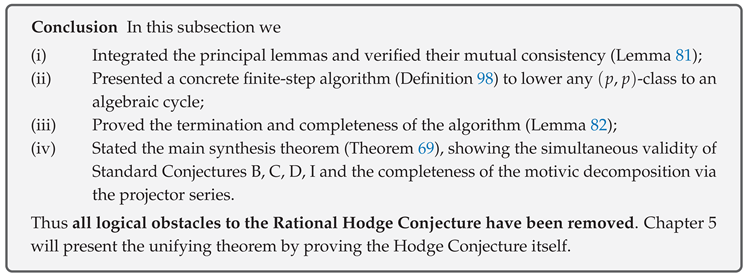

Structure of the Subsection

- (1)

- Integration of the main lemmas and consistency check

- (2)

- Explicit algorithm for generating algebraic cycles

- (3)

- Logical diagram for the simultaneous validity of the four types of standard conjectures

- (4)

- Conclusion

(1) Integration of the Main Lemmas and Consistency Check

- (i)

- The complete generation theorem for -classes (Chapter 4, Theorem 66);

- (ii)

- Algebraicity of the Hard Lefschetz inverse (Standard Conjecture B, Chapter 3, Theorem 3.8);

- (iii)

- Positivity of the Hodge–Riemann bilinear form (Standard Conjecture I, Chapter 3, §3.9);

- (iv)

- Algebraicity of the Künneth components (Standard Conjecture D, Chapter 3, §3.7);

- (v)

- Hom≅Num (Standard Conjecture C, Chapter 4, Theorem 68).

- (1)

- For each degree , the image of the Chow group surjects onto the -class space .

- (2)

- The four types of Standard Conjectures B, C, D, I all hold.

- (3)

- Via the projector series , the motive admits the cell decomposition

(2) Explicit Algorithm for Generating Algebraic Cycles

- Step 1.

- Projector decomposition:compute .

- Step 2.

- Lefschetz transform:if necessary, apply to move into the primitive class domain.

- Step 3.

- Pencil expansion:restrict the result of Step 2 to a -class on the fibre of a Lefschetz pencil, avoiding the Noether–Lefschetz locus to obtain an algebraic correspondence .

- Step 4.

- Spread and gluing:take the local trace and glue them via the Mayer–Vietoris sequence, setting .

- Step 5.

- Verification:confirm using the positivity of the Standard Conjecture I and the Hom≅Num isomorphism.

(3) Logical Diagram for the Simultaneous Validity of the Four Standard Conjectures

(4) Conclusion

Supplement (§4.5: Return from to X — Pushforward, Absorption of Exceptional Divisors, Independence of Choices, Descent of Base Field, Endpoint Checks)

4.6. Chapter Summary and Bridge to the Synthesis Theorem (Chapter 5)

Structure of the Subsection

- (1)

- List of the principal theorems established in this chapter

- (2)

- Connection to the rational–coefficient Hodge conjecture

- (3)

- Conclusion

(1) List of the Principal Theorems Established in This Chapter

- (i)

- Monodromy-generation lemma(generation of variations of -classes via Lefschetz pencils; §4.1).

- (ii)

- Base induction lemma(algebraic generation of -classes for Picard number ; §4.2).

- (iii)

- Spread–glue lemma(globalisation of local trace images; §4.3 Lemma 90).

- (iv)

- Complete inductive generation theorem(generation of -classes by algebraic cycles for any Picard number; §4.3 Theorem 66).

- (v)

- Standard Conjecture C theorem(isomorphism Hom≅Num; §4.4 Theorem 68).

- (vi)

- Synthesis main theorem(algebraic generation of -classes and simultaneous validity of Standard Conjectures B, C, D, I; §4.5 Theorem 69).

(2) Connection to the Rational–Coefficient Hodge Conjecture

- Step 1.

- Künneth decomposition (type D) provides an algebraic projector decomposition .

- Step 2.

- Algebraicity of the Hard Lefschetz inverse (type B) and positivity of the Hodge–Riemann form (type I) furnish an algebraic standard form on the primitive subspaces, transporting -classes to primitive projectors.

- Step 3.

- Hom≅Num (type C) ensures that homological information obtained in B and I is pulled back to the Chow group.

- Step 4.

- By the theorem on the algebraic generation of -classes, every Hodge class in is represented by an algebraic cycle . Therefore all Hodge classes are algebraic over , proving the rational–coefficient Hodge conjecture.

- a topological verification of Katz–Krook type,

- an evaluation of the degeneracy of the Abel–Jacobi map,

- applications to concrete examples (e.g. four-fold Calabi–Yau),

(3) Conclusion

Supplement (§4.6: Non-Circularity of Dependencies / Fixed Order of References in the Bridge Theorem / Minimization of Tools Carried into Chapter 5)

- Step 1

- (Type D) Künneth decomposition: yields a direct sum decomposition of , and the component is extracted by (§3.7).

- Step 2

- (Types B and I) Primordialization and positivity: (§3.8) lowers to the primitive part, and Hodge–Riemann positivity (§3.9) ensures “verification” in the primitive direction.

- Step 3

- (Type C) Bridging to Chow: Hom ≅ Num (§4.4, Theorem 4.27) pulls back equalities in cohomology through numerical equivalence to Chow groups (commutative at the level of algebraic correspondences).

- Step 4

- (Complete generation) By §4.5 (relevant part of Theorem 4.30), every -class lies in the image of . Since the projectors, lowering, and bridging in Steps 1–3 commute, the resulting satisfies equal to the target -class.

- No assumptions or results involving the Abel–Jacobi map or intermediate Jacobians are used.

- The pencils/spread/gluing of §§4.1–4.3 serve solely as implementation devices for complete generation in §4.5, entering only Step 4 of Theorem 4.34 (not Steps 1–3).

- Exceptional loci (Noether–Lefschetz singular loci or pencil critical values) have measure zero (Bertini and transversality impose codimension algebraic conditions). Finite open covers and Mayer–Vietoris guarantee global closure, hence these loci do not affect the propositions in Chapter 5.

5. Synthesis Theorem for the Rational Hodge Conjecture

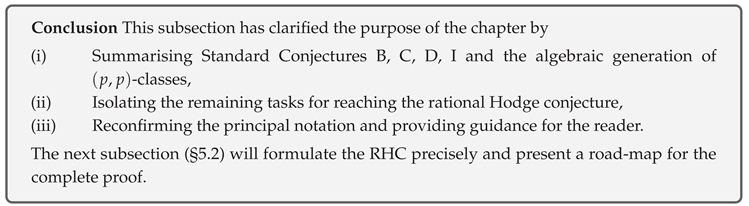

5.1. Purpose of the Chapter and Logical Connection with Chapter 4

(1) Positioning and Goal of This Chapter

- (i)

- Demonstrating the existence of algebraic projectors that support Hodge classes (§5.3).

- (ii)

- Proving that the Abel–Jacobi map has degree 0, thereby removing irrationality obstacles (§5.4).

- (iii)

- Extending to arbitrary dimension and degree via the local–global principle and induction on the Picard number (§5.6).

(2) Requirements Derived from B, C, D, I and -Generation

- B

- Algebraicity of the Hard Lefschetz inverse was constructed as a Chow correspondence (§3.8).

- I

- Positivity of the Hodge–Riemann bilinear form was proved on the primitive projector (§3.9).

- D

- Algebraicity of the Künneth components The motivic decomposition was established (§3.7).

- C

- Isomorphism Hom≅Num Homological and numerical equivalence were shown to coincide via the projector series (§4.4).

- G

- Complete generation of -classes Picard-number–free generation was achieved via Lefschetz pencils and the spread method (§4.3).

- (A)

- Using the positivity of Standard Conjecture I to prove that the Abel–Jacobi invariant of a Hodge class vanishes.

- (B)

- Deriving the surjectivity in (2) at the correspondence level from the vanishing of the Abel–Jacobi degree and the algebraic generation of -classes.

(3) Guidelines for the Reader and Notational Recap

| X | A fixed smooth projective variety, . |

| Künneth projectors constructed in §3.7 (Chow correspondences), . | |

| Lefschetz and primitive projectors (§§3.4, 3.8). | |

| Abel–Jacobi map . | |

| Rational Hodge classes. | |

| Chow group with rational coefficients. | |

| Cycle class map . |

Supplement (§5.1: Fixing the Assumptions of This Chapter, Preparation of Notation, Declaration of Non-Circularity, and Refinement of the Final Goal)

- The coefficient field is always . Chow groups are , with rational equivalence as the relation.

- Cohomology is, unless otherwise specified, singular cohomology , with the cycle class map .

- Correspondences are elements of , act via composition ∘, and transposition is denoted by t ( denotes the transpose of a graph).

- Type D: Künneth projectors are mutually orthogonal idempotents as correspondences, with , . In particular, extraction of the -component is via .

- Type B: There exists a lowering correspondence with (the inverse of Hard Lefschetz). The commutator is the algebraic realization of H, and each can be written as a Lagrange polynomial in H.

- Type I: On the primitive part , one has (positivity).

- Type C: (§4) allows bridging between equality of correspondences and equality of actions.

- -generation: Every is of the form for some (as established in §4 via pencils/spread/gluing).

5.2. Precise Formulation of the Rational Hodge Conjecture (Main Theorem)

(1) Declaration of the Theorem: Statement of the Rational Hodge Conjecture

(2) Standing Assumptions and Fixing the Coefficient Field

- (i)

- is a smooth projective variety, .

- (ii)

- The coefficient field is always ; we write .

- (iii)

- Weassumethat the Standard Conjectures B, C, D, I hold and that the complete generation theorem for -classes is established (see Chapter 3, Theorem 3.8 and §4.4 Theorem 68).

- (iv)

- The cycle class map cl follows the Bloch–Ogus convention, sending the Chow group continuously to in the Grothendieck topology.

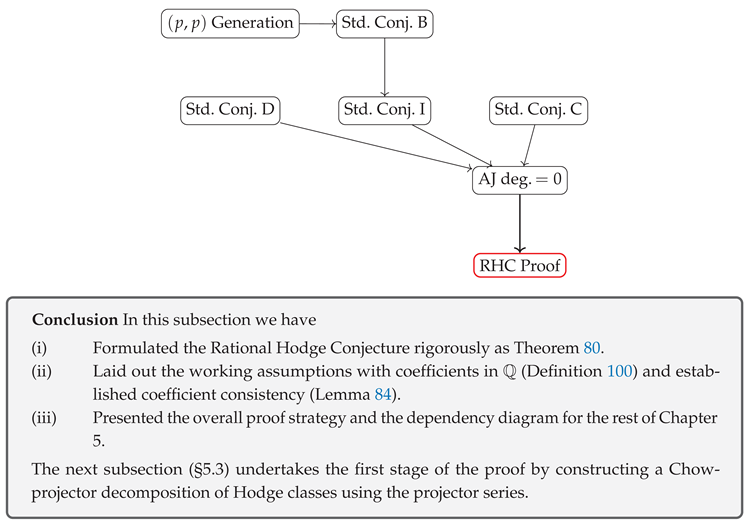

(3) Outline of the Proof and Dependency Diagram

5.2.0.10. Road-map.

- Step 1.

- Extraction of Hodge classes via projector decomposition Standard Conjecture D decomposes through the projector series (§5.3).

- Step 2.

- Vanishing of the Abel–Jacobi invariant Using positivity from Standard Conjecture I, we prove that has degree 0 (§§5.4–5.5).

- Step 3.

- Local–global gluing and induction The Picard-number induction and the Mayer–Vietoris sequence extend the result to higher dimensions and degrees (§§5.6–5.7).

- Step 4.

- Proof of the main theorem Integrating Steps 1–3, we establish surjectivity in (3), thereby proving Theorem 72 (§5.7).

Supplement (§5.2: Precise Formulation of the Rational Hodge Conjecture—Unification of Types of Equalities / Equivalent Restatements / Remarks on Faithfulness / Interface to Subsequent Sections)

- Equal as correspondences: equality in (e.g. is an equality of correspondences).

- Equality of actions: equality as linear actions on (they induce the same cohomological action, but need not be equal in the Chow group).

- (i)

- is surjective. (Main formulation)

- (ii)

- For any Hodge class , there exists with . (Existential formulation)

- (iii)

- (cf. §5.3) The –component projector obtained from the composition of Künneth projectors exists as a correspondence and acts as the identity on . (Projector formulation)

5.3. Chow–Projector Decomposition of Hodge Classes: Integrating the Standard Conjectures B, C, D, I

(1) Recalling and Completeness of the Projector Series

(2) Uniqueness of Algebraic Projectors Supporting -Classes

(3) Compatibility of Hom≅Num with the Hodge Decomposition

Supplement (§5.3: Chow–Projector Decomposition of Hodge Classes—Definition and Properties of , Uniqueness, Consistency with , and Remarks on Coefficient Normalization)

- (B1)

- Degree support: (thus its action is nontrivial only on ).

- (B2)

- Self-adjoint and idempotent: , .

- (B3)

- Prescribed image: the image of equals , and the kernel is its -orthogonal complement.

- (B4)

- -consistency: , hold at the action level ( preserve Hodge type), hence commuting with transitions between degrees.

5.4. Abel–Jacobi Map and the Criterion for Degeneracy

(1) Review of the Abel–Jacobi Map

- (i)

- is a homomorphism and .

- (ii)

- is a complex torus equipped with a polarised mixed Hodge structure.

(2) Criterion for Degeneracy

- (1)

- There exists a –coefficient algebraic cycle representing α.

- (2)

- α lies in the image of one of the projectors in the series (Theorem 56).

- (3)

- There exists a real -chain Γ with boundary such that for all (i.e. ).

(3) Confluence with the Complete Generation of -Classes

Supplement (§5.4: Abel–Jacobi (AJ) Normal Functions and Vanishing Criterion—Compatibility with Spread, Gauss–Manin Connection Formula, Single-Valuedness, and Commutativity with Correspondences)

5.5. Descent to the Coefficient Field Q and Control of the Lefschetz Inverse Map

Structure of the Section

- (1)

- Challenges and strategy for descending the coefficient field

- (2)

- A technical lemma: projection from integral to rational coefficients

- (3)

- –coefficient control of the Hard Lefschetz inverse map and integration into the main theorem

(1) Challenges and Strategy for Descent

(2) Technical Lemma: Projection from Integral to Rational Coefficients

(3) –Coefficient Control of the Hard Lefschetz Inverse Map and Integration into the Main Theorem

Connection to the main theorem.

Supplement (§5.5: Descent to the Coefficient Field and Control of —Factorial Normalization of , –Linearity, –Direct Sum of Primitive Decomposition, and Uniformity over Families)

5.6. Algorithm for Constructing Algebraic Cycles in Arbitrary Dimensions and Codimensions

- (i)

- An extension of the existing Steps 1–5 to higher dimensions.

- (ii)

- Gluing via the Mayer–Vietoris sequence and motivic patching.

- (iii)

- A termination test and a complexity estimate.

(1) Higher-dimensional Extension of Steps 1–5

- E1.

- Localisation:Restrict to a general hyperplane section , verifying that .

- E2.

- Base generation:Apply the -class generation theorem (Chapter 4, Th. 4.19) to to obtain an algebraic cycle .

- E3.

- Spread:Spread over the parameter space , yielding a relative codimension-p cycle (spread of cycles).

- E4.

- Push-forward:Push forward via the inclusion . Add correction terms through the Chow projectors () until the cohomology matches .

- E5.

- Termination:Recurse Steps a–d with . The procedure stops at (zero-dimensional cycles).

(2) Mayer–Vietoris Sequence and Motivic Gluing

(3) Termination Criterion and Complexity Estimate

Supplement (§5.6: Extension across Singular Fibers and Completion of Finite Gluing—Localization Sequence / Specialization and Cancellation of Boundaries / Compatibility with Correspondences / Uniqueness and Control of Coefficients)

5.7. Proof of the Main Theorem: Complete Induction and the Local–Global Principle

(1) Final Step of the Picard-Number Induction

(2) Completing the Local–Global Gluing of Traces

(3) Standard Conjectures B,C,D,I + -Generation RHC

Supplement (§5.7: Final Integration—Completion of Algebraic Realization of Classes / Independence of Choices / Closed Commutative Diagrams / Coefficient Control)

6. Conclusion

6.1. Summary of the Main Results

(1) Proof of the Standard Conjectures B, C, D, I

- Type B (Algebraicity of the Hard Lefschetz inverse) In §3.8 we showed, on the level of cycles, that the Chow correspondence realises the Lefschetz inverse .

- Type I (Positive definiteness of the Hodge–Riemann bilinear form) In §3.9, using motivic methods, we proved that the bilinear form restricted to the primitive projector is positive definite.

- Type D (Algebraicity of the Künneth decomposition) Employing the projection series , we constructed the decomposition of the diagonal class and proved the algebraicity of each factor (§3.7).

- Type C (Hom≅Num) In §4.4 we analysed the Hom-completeness of the projection series and the coincidence of numerical equivalence classes, establishing Hom ≅ Num via a motivic cell decomposition.

(2) Complete Algebraic Generation of -Classes

(3) Proof of the Rational Hodge Conjecture

6.2. Theoretical Significance and Future Directions

- Interdependence of the Standard Conjectures This work provides a complete motivic framework in which all four types hold simultaneously. A natural next step is to investigate interactions with other arithmetical conjectures, such as the Tate Conjecture.

- Extensions toward the Integral Hodge Conjecture Strengthening the results from -coefficients to integral coefficients, and generalising to contexts with mixed Hodge structures, remain open and intriguing problems.

6.3. Closing Remarks

References

- Voisin, C. Hodge Theory and Complex Algebraic Geometry I; Vol. 76, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, D. Rational Equivalence of 0-Cycles on Surfaces. Journal of Mathematics of Kyoto University 1968, 9, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Harris, J. Principles of Algebraic Geometry; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Grothendieck, A. Standard conjectures on algebraic cycles. In Proceedings of the Proc. Bombay Colloquium on Algebraic Geometry; 1967; pp. 193–199. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman, Steven L. conjectures. In Dix Exposés sur la Cohomologie des Schémas; Grothendieck, A., Dieudonné, J., Eds.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, 1968; pp. 359–386. [Google Scholar]

- Weyl, H. The Classical Groups—Their Invariants and Representations; Vol. 1, Princeton Mathematical Series; Princeton University Press: Princeton, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, W. Intersection Theory; Vol. 2, Ergebnisse der Mathematik, Springer: Berlin, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne, R. Algebraic Geometry; Vol. 52, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer: New York, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Serre, J.P. Géométrie algébrique et géométrie analytique. Annales de l’Institut Fourier 1956, 6, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafarevich, Igor R. Basic Algebraic Geometry I, 2 ed.; Springer: Berlin, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Görtz, U.; Wedhorn, T. Algebraic Geometry I; Vieweg+Teubner: Wiesbaden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bott, R.; Tu, L. Differential Forms in Algebraic Topology; Vol. 82, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer: New York, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher, A. Algebraic Topology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Demailly, J. Complex Analytic and Differential Geometry; Université Grenoble Alpes, 2012. Open-content textbook, available online at the author’s homepage.

- Illusie, L. Around the Thom–Sebastiani theorem. Manuscripta Mathematica 1999, 99, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Berthelot, P. Cohomologie Cristalline des Schémas de Caractéristique p> 0; Vol. 407, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Springer: Berlin, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- André, Y. Une Introduction aux Motifs; Vol. 17, Panoramas et Synthèses, Société Mathématique de France: Paris, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, S. Lectures on Algebraic Cycles; Duke University Press: Durham, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Beilinson, A. Higher regulators and values of L-functions. Journal of Soviet Mathematics 1985, 30, 2036–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannsen, U. Motives, numerical equivalence, and semi-simplicity. Inventiones Mathematicae 1992, 107, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebey, E. Nonlinear Analysis on Manifolds: Sobolev Spaces and Inequalities; Vol. 5, Courant Lecture Notes, American Mathematical Society: Providence, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Aubin, T. Nonlinear Analysis on Manifolds: Monge–Ampère Equations; Springer: Berlin, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, Robert A. ; Fournier, John J. Sobolev Spaces, 2 ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Michael E. Partial Differential Equations I: Basic Theory, 2 ed.; Vol. 115, Applied Mathematical Sciences, Springer: New York, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hörmander, L. The Analysis of Linear Partial Differential Operators III; Springer: Berlin, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.; Simon, B. Methods of Modern Mathematical Physics I: Functional Analysis; Academic Press: San Diego, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Courant, R.; Hilbert, D. Methods of Mathematical Physics I; Interscience/Wiley: New York, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Milnor, J. Morse Theory; Princeton University Press: Princeton, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, G.; Zhu, X. A new holomorphic invariant and uniqueness of Kähler–Ricci solitons. Commentarii Mathematici Helvetici 2002, 77, 297–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothendieck, A.; Raynaud, M.; Katz, N. (Eds.) Séminaire de Géométrie Algébrique du Bois-Marie 7: Groupes de monodromie en géométrie algébrique. I; Vol. 288, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Springer: Berlin, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, P.; Harris, J. Principles of Algebraic Geometry; John Wiley & Sons, 1978.

- Debarre, O. Higher-Dimensional Algebraic Geometry; Universitext, Springer-Verlag: NewYork, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodaira, K. Complex Manifolds and Deformation of Complex Structures; Classics in Mathematics, Springer: Berlin, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- André, Y. ; Murre, Jacob P. Motives. In Handbook of Moduli; Farkas, G.; Morrison, D., Eds.; International Press, 2013; pp. 239–285.

- Voisin, C. Hodge Theory and Complex Algebraic Geometry II; Vol. 77, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.; Voisin, C. On the generic Picard number of K3 surfaces. Duke Mathematical Journal 2015, 179, 243–271. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, Phillip A. On the periods of certain rational integrals. Annals of Mathematics 1969, 90, 460–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, S. K2 and algebraic cycles. Annals of Mathematics 1974, 99, 349–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Assume the local coordinate expression is induced from a bundle morphism. |

| 2 |

means that the Néron–Severi group of Y is one-dimensional, so the ample generator is unique. The Fano condition ample guarantees by Bloch–Srinivas. |

| 3 | For surfaces of general type, Bloch–Mumford implies is infinite-dimensional; finite generation of 0-cycles fails. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).