Submitted:

07 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Results

Mutual Co-Clustering of NRas and PI3K at the Plasma Membrane of Melanoma Cells

PI3K Recruitment to NRas Clusters Declines, yet Persists over Minutes

PI3K Co-Clusters with Oncogenic NRas Mutants

BRAF Recruitment to NRas Clusters Is Simultaneous with PI3K but less Homogeneous

RBD Mediates Effective Recruitment of Effectors to NRas Nanoclusters

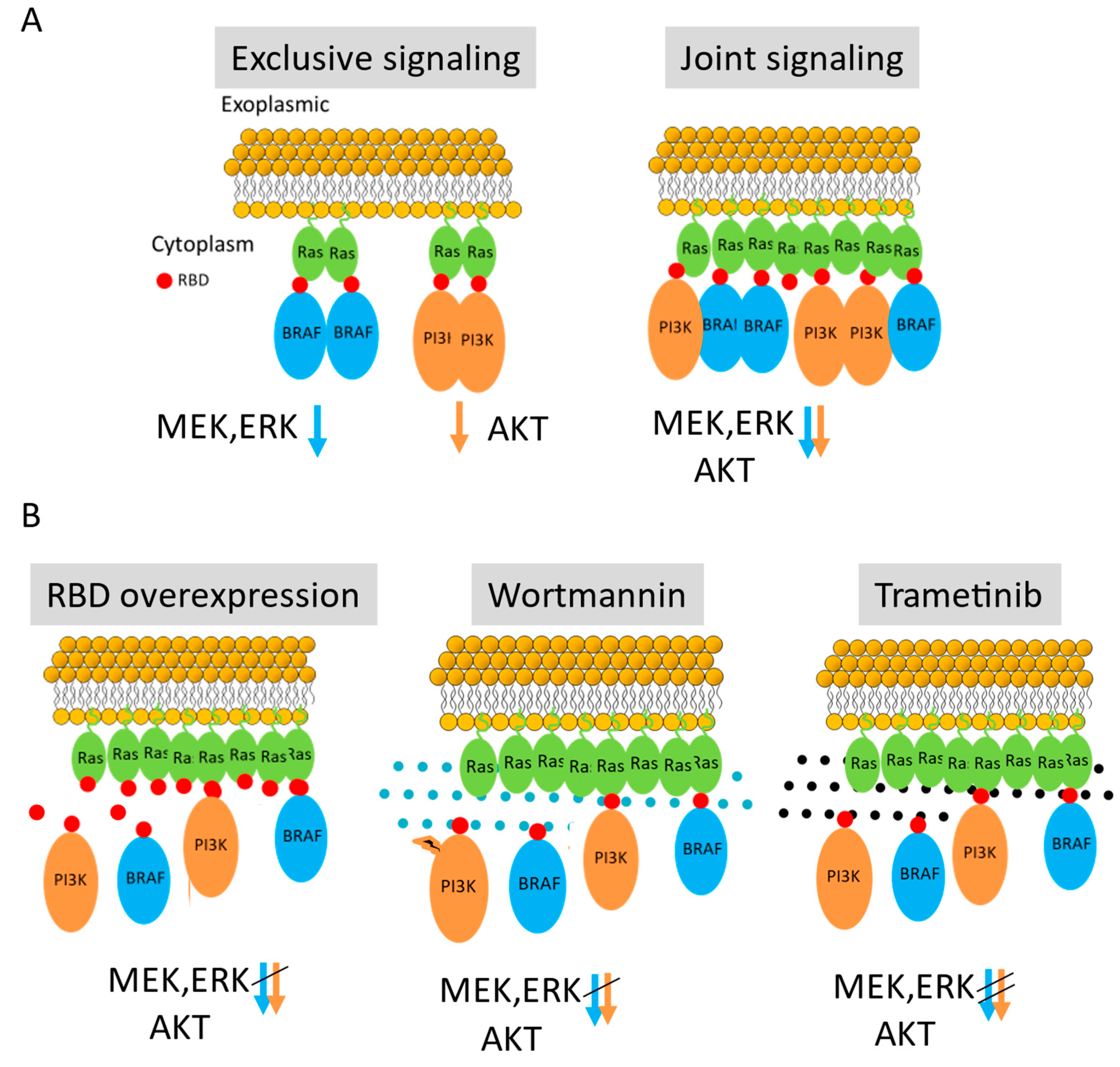

RBD Overexpression Competes with PI3K Recruitment to NRas Nanoclusters

PI3K and NRas Self-Clustering and Co-Clustering Are Reduced by Inhibiting PI3K Activity Using Wortmannin

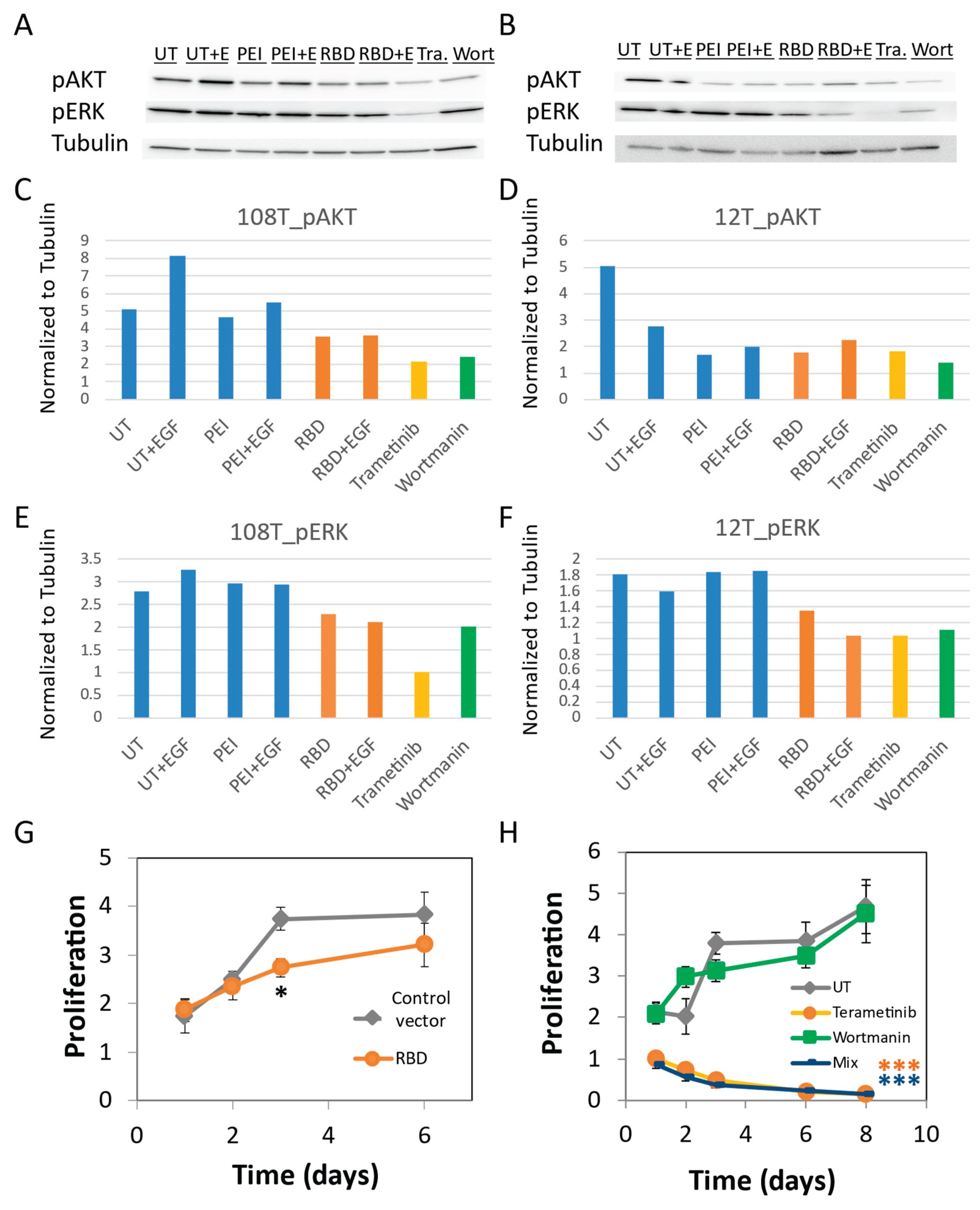

pAKT Is Reduced by Cells Treatment with MEK Inhibitor (Trametinib) and RBD Overexpression

pERK Is Reduced by Cells Treatment with PI3K Inhibitor (Wortmannin) and RBD Overexpression

RBD Overexpression and MEK Inhibition Significantly Decrease Melanoma Cell Growth

Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olson, M.F.; Marais, R. Ras protein signalling. Semin. Immunol. 2000, 12, 63–73. [CrossRef]

- Prior, I.A.; Hood, F.E.; Hartley, J.L. The frequency of ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 2669–2974.

- Cancer Genome Atlas, N. Genomic Classification of Cutaneous Melanoma. Cell 2015, 161, 1681–1696. [CrossRef]

- Hodis, E.; Watson, I.R.; Kryukov, G. V; Arold, S.T.; Imielinski, M.; Theurillat, J.P.; Nickerson, E.; Auclair, D.; Li, L.; Place, C.; et al. A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell 2012, 150, 251–263. [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.A.; Stemke-Hale, K.; Lin, E.; Tellez, C.; Deng, W.; Gopal, Y.N.; Woodman, S.E.; Calderone, T.C.; Ju, Z.; Lazar, A.J.; et al. Integrated Molecular and Clinical Analysis of AKT Activation in Metastatic Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 7538–7546. [CrossRef]

- Prior, I.A.; Muncke, C.; Parton, R.G.; Hancock, J.F. Direct visualization of ras proteins in spatially distinct cell surface microdomains. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 160, 165–170. [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Harding, A.; Inder, K.; Plowman, S.; Parton, R.G.; Hancock, J.F. Plasma membrane nanoswitches generate high-fidelity Ras signal transduction. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 905–914. [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.F.; Parton, R.G. Ras plasma membrane signalling platforms. Biochem. J. 2005, 389, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Rawson, S.; Schmoker, A.; Kim, B.-W.; Oh, S.; Song, K.; Jeon, H.; Eck, M.J. Cryo-EM structure of a RAS/RAF recruitment complex. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4580. [CrossRef]

- Steffen, C.L.; Manoharan, G. babu; Pavic, K.; Yeste-Vázquez, A.; Knuuttila, M.; Arora, N.; Zhou, Y.; Härmä, H.; Gaigneaux, A.; Grossmann, T.N.; et al. Identification of an H-Ras nanocluster disrupting peptide. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 837. [CrossRef]

- Shaw Research, D.E.; York, N.; Mysore, V.P.; Zhou, Z.-W.; Ambrogio, C.; Li, L.; Kapp, J.N.; Lu, C.; Wang, Q.; Tucker, M.R.; et al. A structural model of a Ras-Raf signalosome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. [CrossRef]

- Betzig, E.; Patterson, G.H.; Sougrat, R.; Lindwasser, O.W.; Olenych, S.; Bonifacino, J.S.; Davidson, M.W.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Hess, H.F. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science 2006, 313, 1642–1645. [CrossRef]

- Abankwa, D.; Gorfe, A.A.; Hancock, J.F. Ras nanoclusters: Molecular structure and assembly. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007, 18, 599–607. [CrossRef]

- Yakovian, O.; Sajman, J.; Arafeh, R.; Neve-Oz, Y.; Alon, M.; Samuels, Y.; Sherman, E. MEK inhibition reverses aberrant signaling in melanoma cells through reorganization of nras and braf in self nanoclusters. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 1279–1292. [CrossRef]

- Yakovian, O.; Sajman, J.; Alon, M.; Arafeh, R.; Samuels, Y.; Sherman, E. NRas activity is regulated by dynamic interactions with nanoscale signaling clusters at the plasma membrane. iScience 2022, 25, 105282. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Viciana, P.; Warne, P.H.; Dhand, R.; Vanhaesebroeck, B.; Gout, I.; Fry, M.J.; Waterfield, M.D.; Downward, J. Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase direct target of Ras. Nature 1994, 370, 527–532. [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.H.; Perisic, O.; Ried, C.; Stephens, L. Structural insights into phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalysis and signalling. 1999, 944, 313–320. [CrossRef]

- Pacold, M.E.; Suire, S.; Perisic, O.; Lara-Gonzalez, S.; Davis, C.T.; Walker, E.H.; Hawkins, P.T.; Stephens, L.; Eccleston, J.F.; Williams, R.L. Crystal structure and functional analysis of Ras binding to its effector phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma. Cell 2000, 103, 931–943. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Jang, H.; Nussinov, R. The structural basis for Ras activation of PI3Kα lipid kinase. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 12021–12028. [CrossRef]

- Czyzyk, D.; Yan, W.; Messing, S.; Gillette, W.; Tsuji, T.; Yamaguchi, M.; Furuzono, S.; Turner, D.M.; Esposito, D.; Nissley, D. V; et al. Structural insights into isoform-speci fi c RAS- PI3K α interactions and the role of RAS in PI3K α activation. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Alon, M.; Arafeh, R.; Sang Lee, J.; Madan, S.; Kalaora, S.; Nagler, A.; Abgarian, T.; Greenberg, P.; Ruppin, E.; Samuels, Y. CAPN1 is a novel binding partner and regulator of the tumor suppressor NF1 in melanoma. Oncotarget 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Aramini, J.M.; Vorobiev, S.M.; Tuberty, L.M.; Janjua, H.; Campbell, E.T.; Seetharaman, J.; Su, M.; Huang, Y.J.; Acton, T.B.; Xiao, R.; et al. The RAS-Binding Domain of Human BRAF Protein Serine/Threonine Kinase Exhibits Allosteric Conformational Changes upon Binding HRAS. Structure 2015, 23, 1382–1393. [CrossRef]

- Subach, F. V; Malashkevich, V.N.; Zencheck, W.D.; Xiao, H.; Filonov, G.S.; Almo, S.C.; Verkhusha, V. V Photoactivation mechanism of PAmCherry based on crystal structures of the protein in the dark and fluorescent states. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 21097–21102. [CrossRef]

- Ovesný, M.; Křížek, P.; Borkovec, J.; Svindrych, Z.; Hagen, G.M. ThunderSTORM: a comprehensive ImageJ plug-in for PALM and STORM data analysis and super-resolution imaging. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2389–2390. [CrossRef]

- Betzig, E.; Patterson, G.H.; Sougrat, R.; Lindwasser, O.W.; Olenych, S.; Bonifacino, J.S.; Davidson, M.W.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Hess, H.F. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science (80-. ). 2006, 313, 1642–1645. [CrossRef]

- Sander, J.; Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Xu, X. Density-based clustering in spatial databases: The algorithm GDBSCAN and its applications. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 1998, 2, 169–194. [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, T.; Moloney, K.A. Rings, circles, and null-models for point pattern analysis in ecology. Oikos 2004, 104, 209–229. [CrossRef]

- Sherman, E.; Barr, V.A.A.; Samelson, L.E.E. Resolving multi-molecular protein interactions by photoactivated localization microscopy. Methods 2013, 59, 261–269. [CrossRef]

- Malkusch, S.; Endesfelder, U.; Mondry, J.; Gelléri, M.; Verveer, P.J.; Heilemann, M. Coordinate-based colocalization analysis of single-molecule localization microscopy data. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 137, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, C.; Arévalo-Alameda, C.; Castellano, E. The importance of being PI3K in the RAS signaling network. Genes (Basel). 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Fedorenko, I. V; Gibney, G.T.; Smalley, K.S.M. NRAS mutant melanoma: biological behavior and future strategies for therapeutic management. Oncogene 2013, 32, 3009–3018. [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, G.A.; Der, C.J.; Rossman, K.L. RAS isoforms and mutations in cancer at a glance. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Nussinov, R.; Tsai, C.-J.; Jang, H. Ras assemblies and signaling at the membrane. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2020, 62, 140–148. [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, N.; Yamashita, S.; Kurokawa, K. Spatio-temporal images of activation of Ras and Rap1. 2001.

- Ferby, I.; Waga, I.; Kume, K.; Sakanaka, C.; Shimizu, T. PAF-Induced MAPK Activation is Inhibited by Wortmannin in Neutrophils and Macrophages BT - Platelet-Activating Factor and Related Lipid Mediators 2: Roles in Health and Disease. In; Nigam, S., Kunkel, G., Prescott, S.M., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1996; pp. 321–326 ISBN 978-1-4899-0179-8.

- Barr, V.A.; Sherman, E.; Yi, J.; Akpan, I.; Rouquette-Jazdanian, A.K.; Samelson, L.E.; V. A. Barr J. Yi, I. Akpan, A. K. Rouquette-Jazdanian and L. E. Samelson, E.S. Development of nanoscale structure in LAT-based signaling complexes. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 4548–4562. [CrossRef]

- Sherman, E.; Barr, V.A.; Merrill, R.K.; Regan, C.K.; Sommers, C.L.; Samelson, L.E. Hierarchical nanostructure and synergy of multimolecular signalling complexes. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12161. [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.-J.; Hancock, J.F. Ras nanoclusters: a new drug target? Small GTPases 2013, 4, 57–60. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, M.C.; Er, E.E.; Blenis, J. The Ras-ERK and PI3K-mTOR pathways: cross-talk and compensation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011, 36, 320–328. [CrossRef]

- Balagopalan, L.; Coussens, N.P.; Sherman, E.; Samelson, L.E.; Sommers, C.L. The LAT story: a tale of cooperativity, coordination, and choreography. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2. [CrossRef]

- Engelman, J.A.; Chen, L.; Tan, X.; Crosby, K.; Guimaraes, A.R.; Upadhyay, R.; Maira, M.; Mcnamara, K.; Perera, S.A.; Song, Y.; et al. Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. 2008, 14, 1351–1356. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).