Submitted:

15 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Sumatra camphor (Dryobalanops aromatica Gaertn.) is a high-value non-timber forest product (NTFP) traditionally harvested by forest-dependent communities in northern Sumatra, Indonesia. Despite its extensive ethnobotanical utilization in medicinal and olfactory applications, scientific data on its phytochemical composition remain limited. This study aims to characterize the physical and phytochemical properties of Sumatra camphor oleoresin, collected from natural population in the Pakpak Bharat of Sumatra, one of few remaining endemic habitats for this vulnerable species. Using traditional oleoresin extraction methods, two fractions—camphor oil and aqueous camphor—were collected and analysed. Phytochemical identification was conducted using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. The analysis identified 79 compounds in camphor oil and 11 in the aqueous fraction, each with distinct profiles. Camphor oil was dominated by non-polar volatile compounds with pronounced olfactory properties and prospects bioactive activities, while aqueous camphor contained polar compounds such as carboxylic acids, esters, and alcohols, which have pharmacological and functional potential. These findings provide scientific evidence supporting the traditional utilization of Sumatran camphor and its bioactive potential for valorisation in plant-based cosmetic products, aromatherapy, and pharmaceutical industries. Furthermore, the results contribute to conservation-based bioeconomic strategies for managing Sumatra camphor sustainably as part of community-based forest management systems in Indonesia.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

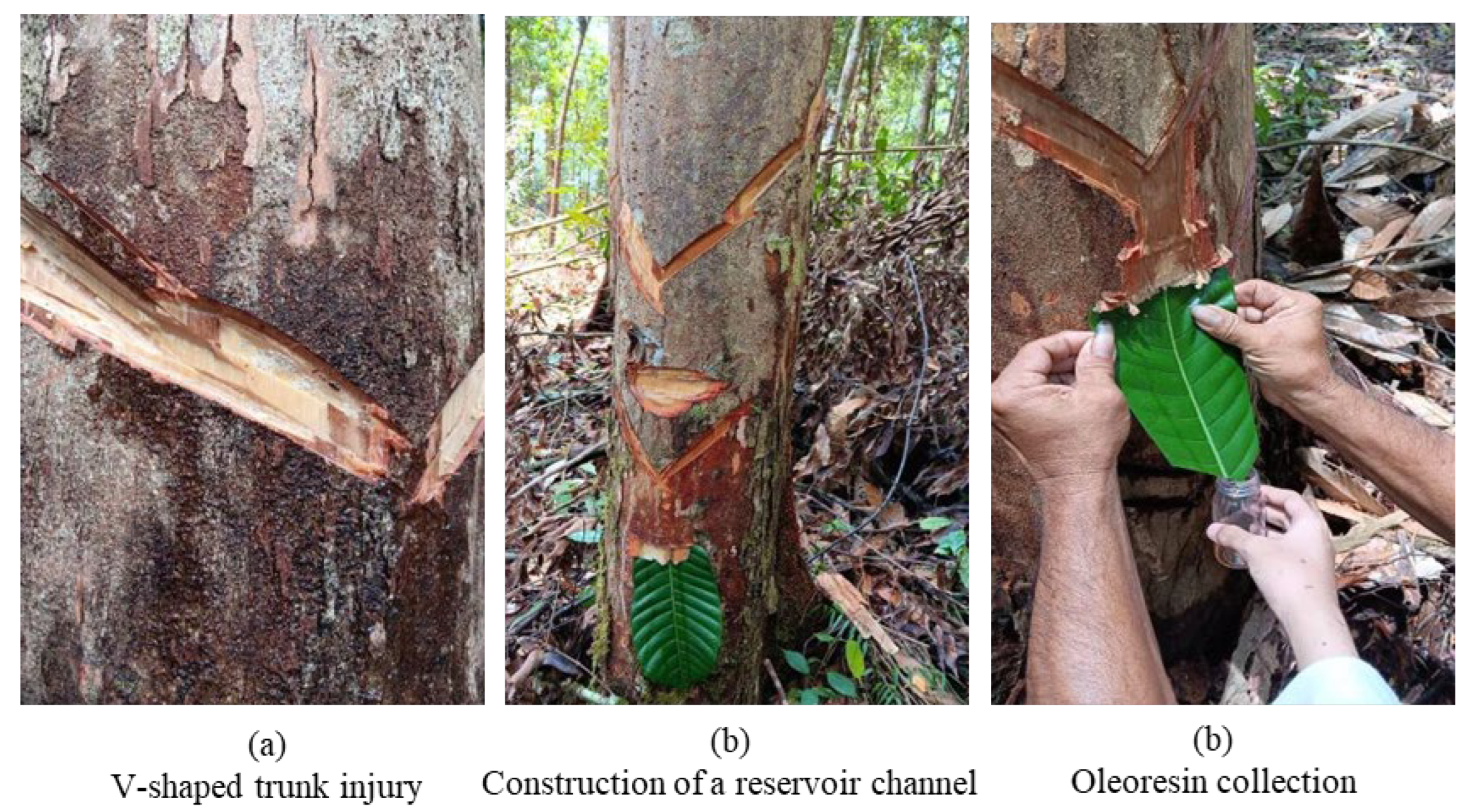

2.1. Oleoresin Hasvesting

2.3. Analysis of Phytochemical Component

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Sample Collection

3.2. Analysis Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Environment and Forestry. The State of Indonesia’s Forests 2020. Jakarta; 2021.

- Sun, J.; Liu, B.; Rustiami, H.; Xiao, H.; Shen, X.; Ma, K. Mapping Asia Plants: Plant Diversity and a Checklist of Vascular Plants in Indonesia. Plants 2024, 13, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, H.Y.S.H.; Nurfatriani, F.; Indrajaya, Y.; Yuwati, T.W.; Ekawati, S.; Salminah, M.; et al. Mainstreaming Ecosystem Services from Indonesia’s Remaining Forests. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrajaya, Y.; Yuwati, T.W.; Lestari, S.; Winarno, B.; Narendra, B.H.; Nugroho, H.Y.S.H.; et al. Tropical Forest Landscape Restoration in Indonesia: A Review. Land (Basel) 2022, 11, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margono, B.A.; Potapov, P.V.; Turubanova, S.; Stolle, F.; Hansen, M.C. Primary forest cover loss in Indonesia over 2000–2012. Nat Clim Chang 2014, 4, 730–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Kennedy, C.M.; Xu, B. Effective moratoria on land acquisitions reduce tropical deforestation: evidence from Indonesia. Environmental Research Letters 2019, 14, 044009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santika, T.; Meijaard, E.; Budiharta, S.; Law, E.A.; Kusworo, A.; Hutabarat, J.A.; et al. Community forest management in Indonesia: Avoided deforestation in the context of anthropogenic and climate complexities. Global Environmental Change 2017, 46:60–71.

- Heyne, K. Tumbuhan Berguna Indonesia. Vol. III. Jakarta, Indonesia: Yayasan Sarana Wana Jaya; 1987.

- Aswandi, A.; Kholibrina, C.R. New insights into Sumatran camphor (Dryobalanops aromatica Gaertn) management and conservation in western coast Sumatra, Indonesia. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2021, 739, 012061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswandi, A.; Kholibrina, C.R. Essential oil and hydrosol production from leaves and resin of Sumatran camphor (Dryobalanops aromatica). In: AIP Conference Proceedings [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0- 85189243235&doi=10.1063%2f5.0184706&partnerID=40&md5=042218f8065bdd3e3a8f491cc753bc8e.

- Axelsson, E.P.; Franco, F.M. Popular Cultural Keystone Species are also understudied — the case of the camphor tree (Dryobalanops aromatica). Trees, Forests and People 2023, 13:100416.

- RITONGAFN; DWIYANTIFG; KUSMANAC; SIREGARUJ; SIREGARIZ Population genetics and ecology of Sumatran camphor (Dryobalanops aromatica) in natural and community-owned forests in Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2018, 19, 2175–82. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, J.; Song, L.; Cao, X.; Yao, X.; Tang, F.; et al. GC×GC-TOFMS Analysis of Essential Oils Composition from Leaves, Twigs and Seeds of Cinnamomum camphora L. Presl and Their Insecticidal and Repellent Activities. Molecules 2016, 21, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazmiya, M.J.A.; Sultana, A.; Rahman, K.; Heyat MBBin Sumbul Akhtar, F.; et al. Current Insights on Bioactive Molecules, Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Other Pharmacological Activities of Cinnamomum camphora Linn. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022, 2022(1).

- Zhang, H.; Huang, T.; Liao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.; et al. Extraction of Camphor Tree Essential Oil by Steam Distillation and Supercritical CO2 Extraction. Molecules 2022, 27, 5385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, D.S.; Park, S.H.; Park, H. Phytochemistry and Applications of Cinnamomum camphora Essential Oils. Molecules 2022, 27, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Jawaid, T. Cinnamomum camphora (Kapur): Review. Pharmacognosy Journal 2012, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, U.; Kumar, A.; Lohani, H.; Chauhan, N. Chemical Composition of Essential Oil of Camphor Tree ( Cinnamomum camphora ) Leaves Grown in Doon Valley of Uttarakhand. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants 2022, 25, 548–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasaribu, G.; Winarni, I.; Gusti, R.E.P.; Maharani, R.; Fernandes, A.; Harianja, A.H.; et al. Current Challenges and Prospects of Indonesian Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs): A Review. Forests 2021, 12, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Bakar Said, Aswandi Anas. Kafur: Bahan Aromatika Alami Asal Indonesia untuk Dunia Islam masa Umayyah dan Abbasiyah (Abad 7 M – 13 M). Solo: Literasinesia; 2023.

- Narayanankutty, A.; Famurewa, A.C.; Oprea, E. Natural Bioactive Compounds and Human Health. Molecules 2024, 29, 3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelliah, R.; Vijayalakshmi, S.; Karuvelan, M.; Barathikannan, K.; Ghimeray, S.; Oh, D.H. Revitalizing natural products for sustainable drug Discovery: Innovations bridging food bioscience and green therapeutic development. Sustain Chem Pharm 2025, 46:102082.

- Muhammed, N.S.; Haq, B.; Al Shehri, D.; Al-Ahmed, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Zaman, E. A review on underground hydrogen storage: Insight into geological sites, influencing factors and future outlook. Energy Reports 2022, 8:461–99.

- Van Canneyt, K.; Verdonck, P. Mechanics of Biofluids in Living Body. In: Comprehensive Biomedical Physics. Elsevier; 2014. p. 39–53.

- Gyrdymova, Y.V.; Rubtsova, S.A. Caryophyllene and caryophyllene oxide: a variety of chemical transformations and biological activities. Chemical Papers 2022, 76, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasath, K.G.; Alexpandi, R.; Parasuraman, R.; Pavithra, M.; Ravi, A.V.; Pandian, S.K. Anti-inflammatory potential of myristic acid and palmitic acid synergism against systemic candidiasis in Danio rerio (Zebrafish). Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 133:111043.

- Korbecki, J.; Bajdak-Rusinek, K. The effect of palmitic acid on inflammatory response in macrophages: an overview of molecular mechanisms. Inflammation Research 2019, 68, 915–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmar, N. Variational Aspects of Secondary Metabolites. In 2024. p. 3–8.

- Jadaun, J.S.; Yadav, R.; Yadav, N.; Bansal, S.; Sangwan, N.S. Influence of Genetics on the Secondary Metabolites of Plants. In: Natural Secondary Metabolites. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2023. p. 403–33.

- Aggarwal, P.R.; Mehanathan, M.; Choudhary, P. Exploring genetics and genomics trends to understand the link between secondary metabolic genes and agronomic traits in cereals under stress. J Plant Physiol 2024, 303:154379.

- Samanta, A.; Ojha, K.; Mandal, A. Interactions between Acidic Crude Oil and Alkali and Their Effects on Enhanced Oil Recovery. Energy & Fuels 2011, 25, 1642–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, W.; Kelland, S.J.; Jones, D.M. Influence of biodegradation on crude oil acidity and carboxylic acid composition. Org Geochem 2000, 31, 1059–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisiriko, M.; Anastasiadi, M.; Terry, L.A.; Yasri, A.; Beale, M.H.; Ward, J.L. Phenolics from Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: Characterisation and Potential as Biostimulants and Bioprotectants. Molecules 2021, 26, 6343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, P.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, Y. A Brief Review of Phenolic Compounds Identified from Plants: Their Extraction, Analysis, and Biological Activity. Nat Prod Commun 2022, 17(1).

- Salehi, B.; Upadhyay, S.; Erdogan Orhan, I.; Kumar Jugran, A.; LD Jayaweera S, A. Dias D, et al. Therapeutic Potential of α- and β-Pinene: A Miracle Gift of Nature. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 738. [Google Scholar]

- Allenspach, M.; Steuer, C. α-Pinene: A never-ending story. Phytochemistry 2021, 190:112857.

- Valente, J.; Zuzarte, M.; Gonçalves, M.J.; Lopes, M.C.; Cavaleiro, C.; Salgueiro, L.; et al. Antifungal, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of Oenanthe crocata L. essential oil. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2013, 62:349–54.

- Thakre, A.D.; Mulange, S.V.; Kodgire, S.S.; Zore, G.B.; Karuppayil, S.M. Effects of Cinnamaldehyde, Ocimene, Camphene, Curcumin and Farnesene on <i>Candida albicans</i> Adv Microbiol. 2016;06, 627–43.

- Hachlafi, N.E.L.; Aanniz, T.; Menyiy NEl Baaboua AEl Omari NEl Balahbib, A.; et al. In Vitro and in Vivo Biological Investigations of Camphene and Its Mechanism Insights: A Review. Food Reviews International 2023, 39, 1799–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadotti, V.M.; Huang, S.; Zamponi, G.W. The terpenes camphene and alpha-bisabolol inhibit inflammatory and neuropathic pain via Cav3. 2 T-type calcium channels. Mol Brain 2021, 14, 166. [Google Scholar]

- Surendran, S.; Qassadi, F.; Surendran, G.; Lilley, D.; Heinrich, M. Myrcene—What Are the Potential Health Benefits of This Flavouring and Aroma Agent? Front Nutr 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Tang, J. Myrcene Exhibits Antitumor Activity Against Lung Cancer Cells by Inducing Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis Mechanisms. Nat Prod Commun 2020, 15(9).

- Kazemi, M. Phytochemical Composition, Antioxidant, Anti-inflammatory and Antimicrobial Activity of Nigella sativa L. Essential Oil. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants 2014, 17, 1002–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuete, V. Canarium schweinfurthii. In: Medicinal Spices and Vegetables from Africa. Elsevier; 2017. p. 379–84.

- Shiekh RAEl Atwa, A.M.; Elgindy, A.M.; Mustafa, A.M.; Senna, M.M.; Alkabbani, M.A.; et al. Therapeutic applications of eucalyptus essential oils. Inflammopharmacology 2025, 33, 163–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arooj, B.; Asghar, S.; Saleem, M.; Khalid, S.H.; Asif, M.; Chohan, T.; et al. Anti-inflammatory mechanisms of eucalyptol rich Eucalyptus globulus essential oil alone and in combination with flurbiprofen. Inflammopharmacology 2023, 31, 1849–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvatori, E.S.; Morgan, L.V.; Ferrarini, S.; Zilli, G.A.L.; Rosina, A.; Almeida, M.O.P.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory and Antimicrobial Effects of Eucalyptus spp. Essential Oils: A Potential Valuable Use for an Industry Byproduct. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2023, 2023(1).

- Ahmad, R.S.; Imran, M.; Ahmad, M.H.; Khan, M.K.; Yasmin, A.; Saima, H.; et al. Eucalyptus essential oils. In: Essential Oils: Extraction, Characterization and Applications [Internet]. 2023. p. 217–39. Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85158949163&doi=10.1016%2fB978-0-323-91740-7. 0000. [Google Scholar]

- Kardinan, A.; Maris, P.; Darwati, I.; Mustapha, Z.; Ngah, N. Efficacy of Eucalyptus citriodora and Syzygium aromaticum essential oil as insecticidal, antiovipositant, and fumigant against Callosobruchus maculatus F (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). Journal of Entomological and Acarological Research [Internet]. 2023;55(1). Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85175183725&doi=10.4081%2fjear.2023. 1167. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; et al. D-Limonene: Promising and Sustainable Natural Bioactive Compound. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandakumar, P.; Kamaraj, S.; Vanitha, M.K. D-limonene: A multifunctional compound with potent therapeutic effects. J Food Biochem 2021, 45(1).

- Masyita, A.; Mustika Sari, R.; Dwi Astuti, A.; Yasir, B.; Rahma Rumata, N.; Emran TBin et, a.l. Terpenes and terpenoids as main bioactive compounds of essential oils, their roles in human health and potential application as natural food preservatives. Food Chem X 2022, 13:100217.

- Souza, R.P.; Reis ACdos Pimentel, V.D.; Leal Bde, S.; Freitas MMde Esteves Jda, C.; et al. Toxicogenetic profile and antioxidant evaluation of gamma-terpinene: Molecular docking and in vitro and in vivo assays. Drug Chem Toxicol 2025, 48, 959–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bicas, J.L.; Neri-Numa, I.A.; Ruiz, A.L.T.G.; De Carvalho, J.E.; Pastore, G.M. Evaluation of the antioxidant and antiproliferative potential of bioflavors. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2011, 49, 1610–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sales, A.; Felipe Lde, O.; Bicas, J.L. Production, Properties, and Applications of α-Terpineol. Food Bioproc Tech 2020, 13, 1261–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.J.; Lin, J.H.; Hsu, S.C.; Weng, S.W.; Huang, Y.P.; Tang, N.Y.; et al. Alpha-phellandrene promotes immune responses in normal mice through enhancing macrophage phagocytosis and natural killer cell activities. In Vivo. 2013;27, 809–14.

- Radice, M.; Durofil, A.; Buzzi, R.; Baldini, E.; Martínez, A.P.; Scalvenzi, L.; et al. Alpha-Phellandrene and Alpha-Phellandrene-Rich Essential Oils: A Systematic Review of Biological Activities, Pharmaceutical and Food Applications. Life 2022, 12, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang J hong, Sun H long, Chen S yang, Zeng L, Wang T tao. Anti-fungal activity, mechanism studies on α-Phellandrene and Nonanal against Penicillium cyclopium. Bot Stud 2017, 58, 13.

- Hu, X.; Yan, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, J.; Fan, T.; Deng, H.; et al. Advances and perspectives on pharmacological activities and mechanisms of the monoterpene borneol. Phytomedicine 2024, 132:155848.

- Bracalini, M.; Tellini Florenzano, G.; Panzavolta, T. Verbenone Differently Affects the Behavior of Saproxylic Beetles: Trials in Pheromone-Baited Bark Beetle Traps. 2024.

- Bracalini, M.; Florenzano, G.T.; Panzavolta, T. Verbenone Affects the Behavior of Insect Predators and Other Saproxylic Beetles Differently: Trials Using Pheromone-Baited Bark Beetle Traps. Insects 2024, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhao, R.; Chen, H.; Jia, P.; Bao, L.; Tang, H. Bornyl acetate has an anti-inflammatory effect in human chondrocytes via induction of IL-11. IUBMB Life 2014, 66, 854–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao Z jun, Sun Y long, Ruan X fen. Bornyl acetate: A promising agent in phytomedicine for inflammation and immune modulation. Phytomedicine 2023, 114:154781.

- Magnani, R.F.; Volpe, H.X.L.; Luvizotto, R.A.G.; Mulinari, T.A.; Agostini, T.T.; Bastos, J.K.; et al. α-Copaene is a potent repellent against the Asian Citrus Psyllid Diaphorina citri. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, R.F.; Volpe, H.X.L.; Luvizotto, R.A.G.; Mulinari, T.A.; Agostini, T.T.; Bastos, J.K.; et al. α-Copaene is a potent repellent against the Asian Citrus Psyllid Diaphorina citri. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scandiffio, R.; Geddo, F.; Cottone, E.; Querio, G.; Antoniotti, S.; Gallo, M.P.; et al. Protective Effects of (E)-β-Caryophyllene (BCP) in Chronic Inflammation. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francomano, F.; Caruso, A.; Barbarossa, A.; Fazio, A.; La Torre, C.; Ceramella, J.; et al. β-Caryophyllene: A Sesquiterpene with Countless Biological Properties. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes de Lacerda Leite, G.; de Oliveira Barbosa, M.; Pereira Lopes, M.J.; de Araújo Delmondes, G.; Bezerra, D.S.; Araújo, I.M.; et al. Pharmacological and toxicological activities of α-humulene and its isomers: A systematic review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2021, 115:255–74.

- Dalavaye, N.; Nicholas, M.; Pillai, M.; Erridge, S.; Sodergren, M.H. The Clinical Translation of α-humulene – A Scoping Review. Planta Med 2024, 90, 664–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwizhi, N.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Cinnamic Acid Derivatives and Their Biological Efficacy. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, M.; Ribeiro, D.; Janela, J.S.; Varela, C.L.; Costa, S.C.; da Silva, E.T.; et al. Plant-derived and dietary phenolic cinnamic acid derivatives: Anti-inflammatory properties. Food Chem 2024, 459:140080.

- Ruwizhi, N.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Cinnamic Acid Derivatives and Their Biological Efficacy. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, S.P.; Letizia, C.S.; Api, A.M. Fragrance material review on β-caryophyllene alcohol. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2008, 46, S95–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidyt, K.; Fiedorowicz, A.; Strządała, L.; Szumny, A. β -caryophyllene and β -caryophyllene oxide—natural compounds of anticancer and analgesic properties. Cancer Med 2016, 5, 3007–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.S.; Zhu, Y.J.; Li, H.L.; Zhuang, J.X.; Zhang, C.L.; Zhou, J.J.; et al. Inhibitory Effects of Methyl trans -Cinnamate on Mushroom Tyrosinase and Its Antimicrobial Activities. J Agric Food Chem 2009, 57, 2565–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purushothaman, R.; Vishnuram, G.; Ramanathan, T. Antiinflammatory efficacy of n-Hexadecanoic acid from a mangrove plant Excoecaria agallocha L. through in silico, in vitro and in vivo. Pharmacological Research - Natural Products 2025, 7:100203.

- Aparna, V.; Dileep, K.V.; Mandal, P.K.; Karthe, P.; Sadasivan, C.; Haridas, M. Anti-Inflammatory Property of n -Hexadecanoic Acid: Structural Evidence and Kinetic Assessment. Chem Biol Drug Des 2012, 80, 434–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparna, V.; Dileep, K.V.; Mandal, P.K.; Karthe, P.; Sadasivan, C.; Haridas, M. Anti-Inflammatory Property of n -Hexadecanoic Acid: Structural Evidence and Kinetic Assessment. Chem Biol Drug Des 2012, 80, 434–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorova, I.; de Koster, C.G.; Boon, J.J. Analytical Study of Free and Ester Bound Benzoic and Cinnamic Acids of Gum Benzoin Resins by GC-MS and HPLC-frit FAB-MS. Phytochemical Analysis 1997, 8, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.S.; Hong, J.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, H.J.; Park, J.Y.; Choi, J.H.; et al. β-Caryophyllene in the Essential Oil from Chrysanthemum Boreale Induces G1 Phase Cell Cycle Arrest in Human Lung Cancer Cells. Molecules 2019, 24, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; An, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Han, B.; Tao, H.; et al. Vanillin Has Potent Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities In Vitro and in Mouse Colitis Induced by Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafali, M.; Finos, M.A.; Tsoupras, A. Vanillin and Its Derivatives: A Critical Review of Their Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Infective, Wound-Healing, Neuroprotective, and Anti-Cancer Health-Promoting Benefits. Nutraceuticals 2024, 4, 522–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zari, A.T.; Zari, T.A.; Hakeem, K.R. Anticancer properties of eugenol: A review. Molecules [Internet]. 2021;26(23). Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85121119547&doi=10. 3390. [Google Scholar]

- Ulanowska, M.; Olas, B. Biological Properties and Prospects for the Application of Eugenol—A Review. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisar, M.F.; Khadim, M.; Rafiq, M.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Wan, C.C. Pharmacological Properties and Health Benefits of Eugenol: A Comprehensive Review. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021(1).

- Daniel, A.N.; Sartoretto, S.M.; Schmidt, G.; Caparroz-Assef, S.M.; Bersani-Amado, C.A.; Cuman, R.K.N. Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities of eugenol essential oil in experimental animal models. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia [Internet]. 2009;19(1 B):212–7. Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-69949085117&doi=10. 1590. [Google Scholar]

- Kholibrina, C.R.; Aswandi, A. The Consumer Preferences for New Sumatran Camphor Essential Oil-based Products using a Conjoint Analysis Approach. In: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85104173132&doi=10.1088%2f1755-1315%2f715%2f1%2f012078&partnerID=40&md5=e80b926df0942f65655fd4f797329f1c.

- Bhatia, S.P.; Wellington, G.A.; Cocchiara, J.; Lalko, J.; Letizia, C.S.; Api, A.M. Fragrance material review on cinnamyl cinnamate. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2007, 45, S66–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunia-Krzyżak, A.; Słoczyńska, K.; Popiół, J.; Koczurkiewicz, P.; Marona, H.; Pękala, E. Cinnamic acid derivatives in cosmetics: current use and future prospects. Int J Cosmet Sci 2018, 40, 356–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

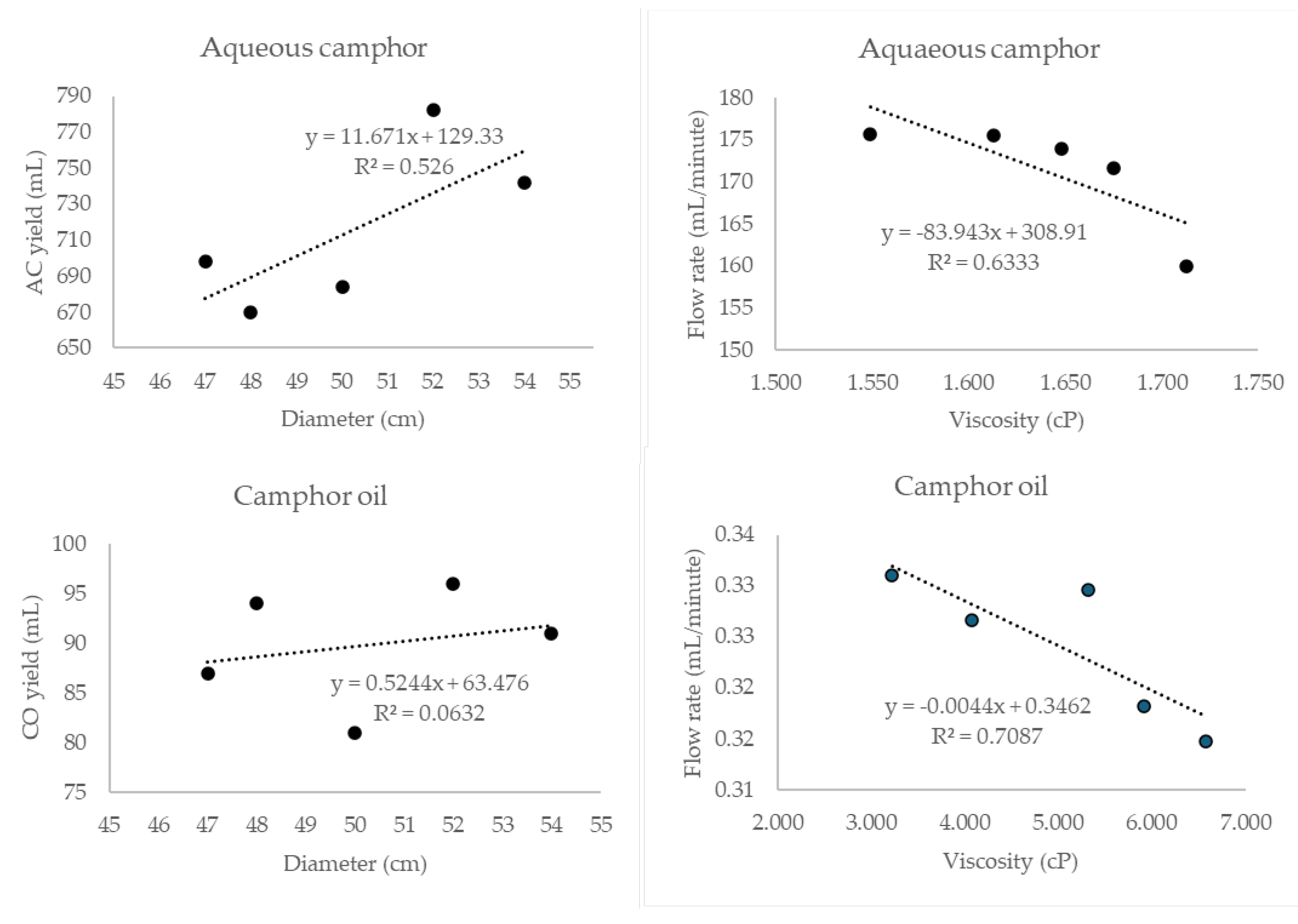

| Sample | Diameter (cm) |

Aqueous camphor | Camphor oil | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (minutes) | Yield (ml) |

Flow rate (ml/min) | Viscocity (cP) |

Time (minutes) | Yield (ml) |

Flow rate (ml/min) | Viscocity (cP) |

||

| Tree 1 | 52 | 4.52 | 722 | 159.85 | 1.713 | 305 | 96 | 0.315 | 6.579 |

| Tree 2 | 48 | 3.90 | 678 | 173.85 | 1.648 | 264 | 87 | 0.330 | 5.325 |

| Tree 3 | 54 | 4.15 | 712 | 171.57 | 1.675 | 286 | 91 | 0.318 | 5.914 |

| Tree 4 | 50 | 3.78 | 664 | 175.51 | 1.613 | 248 | 81 | 0.327 | 4.072 |

| Tree 5 | 48 | 4.10 | 720 | 175.61 | 1.549 | 284 | 94 | 0.331 | 3.225 |

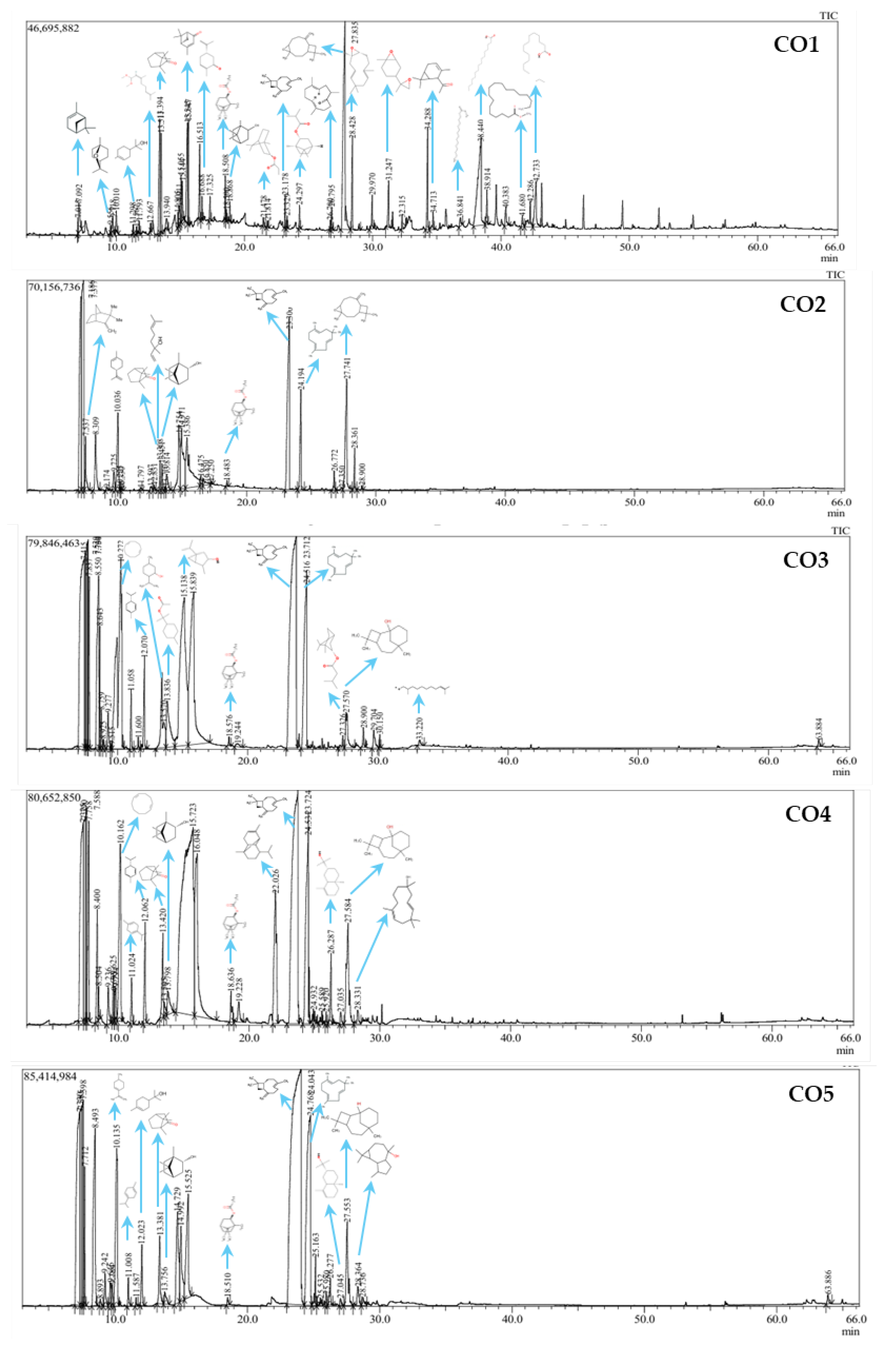

| No | RTime | Component | Group | Area content (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO1 | CO2 | CO3 | CO4 | CO5 | ||||

| 1 | 7.015 | α-Pinene | Hydrocarbon | 2.52 | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | 7.186 | 1,3,6-Heptatriene, 2,5,5-trimethyl- | Hydrocarbon | - | 33.71 | 1.28 | 3.19 | 3.74 |

| 3 | 7.325 | β-Ocimene | Hydrocarbon | - | - | 11.76 | 7.82 | 10.46 |

| 4 | 7.385 | 1,4-Cyclohexadiene, 3,3,6,6-tetramethyl | Hydrocarbon | - | - | - | - | 5.78 |

| 5 | 7.390 | 8-Methylenebicyclo [4.2.0]oct-2-ene | Hydrocarbon | - | - | - | 5.26 | - |

| 6 | 7.520 | 6-Propenylbicyclo [3.1.0]hexan-2-one | Ketone | - | - | 4.04 | - | - |

| 7 | 7.537 | Camphene | Hydrocarbon | - | 1.92 | 1.59 | 2.89 | 1.31 |

| 8 | 8.309 | β-Pinene | Hydrocarbon | - | 3.41 | - | 1.49 | - |

| 9 | 8.493 | Bicyclo [2.2.1]heptane, 2,2-dimethyl-3-methyl | Hydrocarbon | - | - | 4.54 | - | 5.53 |

| 10 | 8.504 | Cyclohexane, 1-isopropyl-1-methyl- | Hydrocarbon | - | - | - | 0.31 | - |

| 11 | 8.643 | Cyclohexane, 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethyl)-, cis | Hydrocarbon | - | - | 1.32 | - | - |

| 12 | 8.759 | Bicyclo [4.1.0]heptane, 3,7,7-trimethyl- | Hydrocarbon | - | - | 0.49 | - | - |

| 13 | 8.893 | β-Myrcene | Hydrocarbon | - | - | 0.14 | - | 0.13 |

| 14 | 9.174 | 4,7-Methano-1H-indene, 2,4,5,6,7,7a-hexahy | Hydrocarbon | - | 0.16 | - | - | - |

| 15 | 9.236 | α-Thujene | Hydrocarbon | - | - | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.68 |

| 16 | 9.515 | Eucalyptol | Ether | 0.99 | - | 0.06 | 0.54 | - |

| 17 | 9.646 | 2-Carene | Hydrocarbon | - | - | - | - | 0.58 |

| 18 | 9.718 | Cymene | Hydrocarbon | 1.08 | 1.08 | - | 0.80 | 0.48 |

| 19 | 10.036 | D-Limonene | Hydrocarbon | - | 4.43 | - | - | 1.00 |

| 20 | 10.135 | para-Menthadiene | Hydrocarbon | - | - | - | - | 4.88 |

| 21 | 10.162 | 1,5-Cyclodecadiene, (E,Z)- | hydrocarbon | - | - | 11.80 | 4.35 | - |

| 22 | 10.330 | trans-β-Ocimene | Hydrocarbon | - | 0.07 | - | - | - |

| 23 | 11.008 | γ-Terpinene | Hydrocarbon | - | - | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.46 |

| 24 | 11.298 | Terpineol | Alcohol | 7.70 | 16.55 | 10.40 | 7.13 | 3.65 |

| 25 | 11.567 | D-Fenchone | Ketone | 0.18 | - | 0.13 | - | 0.09 |

| 26 | 11.793 | p-(1-Propenyl)-toluene | Hydrocarbon | 0.43 | 0.11 | - | - | - |

| 27 | 12.062 | α-Phellandrene | Hydrocarbon | - | - | 1.35 | 1.36 | - |

| 28 | 12.667 | Neral dimethyl acetal | Aldehyde | 3.97 | 0.88 | - | - | - |

| 29 | 12.831 | α-Campholenal | Aldehyde | - | 0.24 | - | - | - |

| 30 | 13.394 | (+)-2-Bornanone (camphor) | Ketone | 5.41 | 1.00 | - | 1.26 | 1.31 |

| 31 | 13.570 | Menthol | Alcohol | - | - | 2.46 | - | - |

| 32 | 13.710 | Linalool | Alcohol | - | 0.14 | - | - | - |

| 33 | 13.756 | Octanal, 7-hydroxy-3,7-dimethyl- | Aldehyde | - | - | - | - | 0.42 |

| 34 | 13.798 | Borneol | Alcohol | - | 6.39 | - | 0.82 | 3.41 |

| 35 | 13.836 | Cyclohexanemethanol, α, α.,4-trimet | Alcohol | - | - | 2.35 | - | - |

| 36 | 13.940 | 7-Octen-2-ol, 2,6-dimethyl- | Alcohol | 0.78 | - | - | - | - |

| 37 | 14.805 | Fenchyl acetate | Ester | 0.60 | - | - | - | - |

| 38 | 15.055 | Bicyclo [3.1.1]hept-2-ene-2-carboxaldehyde, 6 | Aldehyde | 1.86 | - | - | - | - |

| 39 | 15.138 | Bicyclo [3.1.0]hexan-3-ol, 4-methyl-1-(1-meth | Alcohol | - | - | 12.84 | - | - |

| 40 | 15.647 | Verbenone | Ketone | 3.70 | - | - | - | - |

| 41 | 16.688 | D-Carvone | Ketone | 0.75 | - | - | - | - |

| 42 | 17.325 | (−)-Pinanediol | Alcohol | 0.83 | 0.10 | - | - | - |

| 43 | 18.508 | Bornyl acetate | Ester | 4.01 | 1.47 | 0.12 | 0.53 | 0.13 |

| 44 | 18.590 | Carvenone | Ketone | 0.28 | - | - | - | - |

| 45 | 18.868 | Isoborneol | Alcohol | 0.49 | - | - | - | - |

| 46 | 21.478 | Isobornyl propionate | Ester | 0.42 | - | - | - | - |

| 47 | 22.026 | Copaene | Hydrocarbon | - | - | - | 4.11 | - |

| 48 | 23.300 | Caryophyllene | Hydrocarbon | 1.29 | 13.64 | 18.11 | 17.30 | 36.02 |

| 49 | 23.329 | 2-Heptanone, 7,7-dimethoxy-5-(1-methylethy | Ketone | 0.39 | - | - | - | - |

| 50 | 24.194 | Humulene | Hydrocarbon | - | 4.45 | 6.59 | - | 11.96 |

| 51 | 24.297 | Propanoic acid, 2-methyl-, 1,7,7-trimethylbicy | Carboxylic acid | 0.68 | - | 0.13 | - | - |

| 52 | 24.531 | Cyclohexene, 4-[(1E)-1,5-dimethyl-1,4-hexad | Hydrocarbon | - | - | - | 6.70 | - |

| 53 | 24.932 | (3R,4aS,5R)-4a,5-Dimethyl-3-(prop-1-en-2-yl | Hydrocarbon | - | - | - | 0.25 | - |

| 54 | 25.163 | Germacrene D | Hydrocarbon | - | - | - | - | 0.69 |

| 55 | 25.532 | Bicyclo [5.2.0]nonane, 2-methylene-4,8,8- trimethylnonane bicyclic | Hydrocarbon | - | - | - | - | 0.26 |

| 56 | 25.589 | Muurolene | Hydrocarbon | - | - | - | 0.19 | 0.16 |

| 57 | 25.920 | 1H-Cycloprop[e]azulene, decahydro-1,1,7-tri | Hydrocarbon | - | - | - | 0.12 | - |

| 58 | 26.277 | 1-Isopropyl-4,7-dimethyl-1,2,3,5,6,8a-hexahy | Hydrocarbon | - | - | - | 0.88 | 0.48 |

| 59 | 26.700 | 2,5,9-Trimethylcycloundeca-4,8-dienone | Ketone | 0.44 | - | - | - | - |

| 60 | 27.035 | 2-Naphthalenemethanol, 1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,8a-oct | Alcohol | - | - | - | 0.21 | 0.15 |

| 61 | 27.326 | Bornyl isovalerate | Ester | - | - | 0.23 | - | - |

| 62 | 27.553 | Caryophyllenyl alcohol | Alcohol | - | - | 1.23 | 3.30 | 2.65 |

| 63 | 27.835 | Caryophyllene oxide | Oxide | 21.27 | 8.45 | - | - | 0.30 |

| 64 | 28.331 | 3,7-Cycloundecadien-1-ol, 1,5,5,8-tetramethyl- | Alcohol | - | - | - | 0.34 | - |

| 65 | 28.361 | Terpene oxide | Oxide | - | 1.35 | - | - | - |

| 66 | 28.364 | Ledol | Alcohol | - | - | - | - | 0.62 |

| 67 | 28.428 | (1R,3E,7E,11R)-1,5,5,8-Tetramethyl-12-oxab | Ether | 4.26 | - | - | - | - |

| 68 | 28.900 | Bicyclo [3.1.0]hexane-6-methanol, 2-hydroxy- | Alcohol | - | 0.16 | - | - | - |

| 69 | 28.900 | 2(1H)-Naphthalenone, octahydro-1,1,4a-trime | Ketone | - | - | 0.28 | - | - |

| 70 | 29.970 | 11-Hexadecyn-1-ol | Alcohol | 1.49 | - | - | - | - |

| 71 | 31.247 | 7-Oxabicyclo [4.1.0]heptane, 1-methyl-4-(2-m | Oxide | 2.01 | - | - | - | - |

| 72 | 32.135 | (1R,2S,4S,5R,7R)-5-isopropyl-1-methyl-3,8-d | Hydrocarbon | 0.40 | - | - | - | - |

| 73 | 33.220 | 9-Undecenal, 2,10-dimethyl- | Aldehyde | - | - | 0.14 | - | - |

| 74 | 34.713 | 3-Carene, 2-acetyl- | Ketone | 0.86 | - | - | - | - |

| 75 | 36.841 | Methyl palmitate | Ester | 0.56 | - | - | - | - |

| 76 | 38.440 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | Carboxylic acid | 14.92 | - | - | - | - |

| 77 | 40.383 | Eicosanoic acid | Carboxylic acid | 1.14 | - | - | - | - |

| 78 | 41.680 | Methyl stearate | Ester | 0.60 | - | - | - | - |

| 79 | 42.733 | Octadecanoic acid | Carboxylic acid | 4.05 | - | - | - | - |

| Group | Number of Component | Sample CO1 | Sample CO2 | Sample CO3 | Sample CO4 | Sample CO5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Hydrocarbon | 34 | 5 | 5.72 | 10 | 62.98 | 13 | 60.29 | 18 | 58.21 | 18 | 84.60 |

| Alcohol | 15 | 5 | 11.29 | 5 | 23.34 | 5 | 29.28 | 5 | 11.8 | 5 | 10.48 |

| Aldehyde | 5 | 2 | 5.83 | 2 | 1.12 | 1 | 0.14 | - | 1 | 0.42 | |

| Ketone | 10 | 8 | 12.01 | 1 | 1.00 | 3 | 4.45 | 1 | 1.26 | 2 | 1.40 |

| Ether | 2 | 2 | 5.25 | - | 1 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.54 | - | - | |

| Oxide | 3 | 2 | 23.28 | 2 | 9.80 | - | - | - | 1 | 0.30 | |

| Ester | 6 | 5 | 6.19 | 1 | 1.47 | 2 | 0.35 | 1 | 0.53 | 1 | 0.13 |

| Carboxylic acid | 4 | 4 | 20.79 | - | 1 | 0.13 | - | - | - | - | |

| Grand Total | 79 | 33 | 21 | 26 | 26 | 28 | |||||

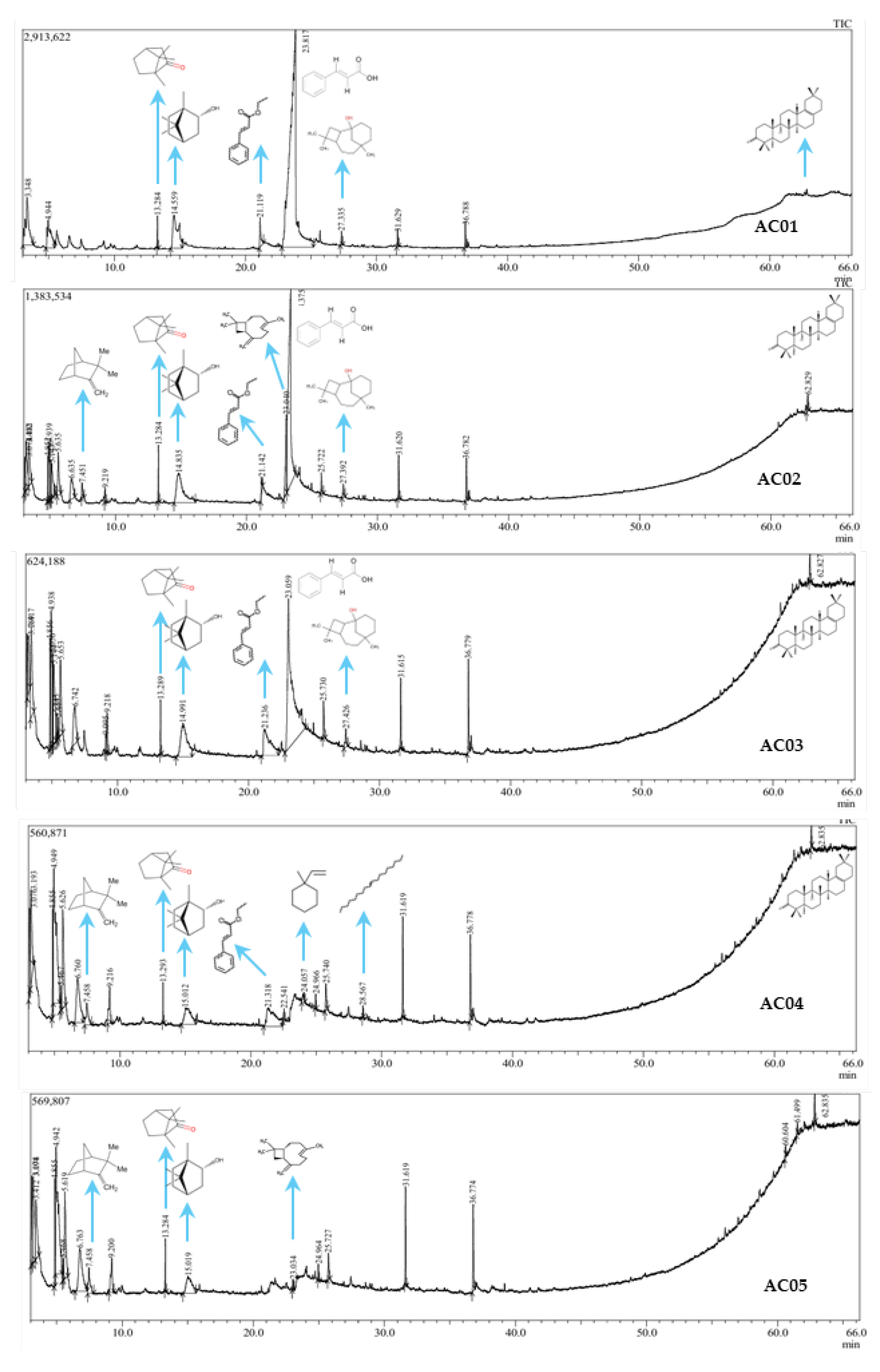

| No | R. Time | Component | Group | Area content (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC1 | AC2 | AC3 | AC4 | AC5 | ||||

| 1 | 7.451 | Camphene | Hydrocarbon | - | 1.77 | - | 13.77 | 22.67 |

| 2 | 13.284 | (+)-2-Bornanone (Camphor) | Ketone | 1.13 | 3.58 | 2.61 | 5.40 | 13.67 |

| 3 | 14.835 | Borneol | Alcohol | 11.18 | 21.87 | 18.52 | 29.52 | 44.80 |

| 4 | 21.119 | Methyl cinnamate | Ester | 1.99 | 1.80 | 15.38 | 41.97 | - |

| 5 | 23.034 | Caryophyllene | Hydrocarbon | - | 11.47 | - | - | 3.27 |

| 6 | 23.059 | trans-Cinnamic acid | Carboxylic acid | 85.07 | 56.51 | 59.76 | - | - |

| 7 | 24.057 | Cyclohexane, 1-ethenyl-1-methyl-2-(1-methyl | Hydrocarbon | - | - | - | 3.58 | - |

| 8 | 27.335 | Caryophyllenyl alcohol | Alcohol | 0.63 | 1.43 | 1.91 | - | - |

| 9 | 28.567 | 9-Octadecene, (E)- | Hydrocarbon | - | - | - | 1.57 | - |

| 10 | 60.604 | Onocerin | Ketone | 3.07 | - | - | - | - |

| 11 | 61.499 | 28-Norolean-17-en-3-one | Ketone | 12.53 | 1.58 | 1.83 | 4.19 | - |

| Group | Area content (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camphor oil | Aqueous camphor | |||||||||

| CO1 | CO2 | CO3 | CO4 | CO5 | AC1 | AC2 | AC3 | AC4 | AC5 | |

| Hydrocarbon | 5.72 | 62.98 | 60.29 | 58.21 | 84.60 | - | 13.24 | - | 18.92 | 25.94 |

| Alcohol | 11.29 | 23.34 | 29.28 | 11.8 | 10.48 | 11.81 | 23.30 | 20.43 | 29.52 | 44.80 |

| Aldehyde | 5.83 | 1.12 | 0.14 | - | 0.42 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ketone | 12.01 | 1.00 | 4.45 | 1.26 | 1.40 | 1.13 | 5.16 | 4.44 | 9.59 | 29.27 |

| Ether | 5.25 | - | 0.06 | 0.54 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Oxide | 23.28 | 9.80 | - | - | 0.30 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ester | 6.19 | 1.47 | 0.35 | 0.53 | 0.13 | 1.99 | 1.80 | 15.38 | 41.97 | - |

| Carboxylic acid | 20.79 | - | 0.13 | - | - | 85.07 | 56.51 | 59.76 | - | - |

| Compound | Aroma Profile | Bioactivity | Application | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavour | Fragrance | Cosmetic | Medicine | |||

| Pinene | Piney, resinous, herbal | Anti-inflammatory, bronchodilator, AChE inhibitor, GABA modulator, antimicrobial (solvent, biofuel)[35,36] | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| β-Ocimene | Sweet, fruity, herbaceous, floral | Antifungal, anti-inflammatory, plant defense [37,38] | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Camphene | Herbal, woody, fir, camphor | Antibacterial, antifungal, anticancer, antioxidant, antiparasitic, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, anti-leishmanial, hepatoprotective, antiviral, anti-acetylcholinesterase inhibitory and hypolipidemic activities [38,39,40] | √ | √ | √ | - |

| β-Myrcene | Fruity, herbal, musky, earthy | Anti-inflammatory, analgesic, sedative, anti-cancer, antitumor [41,42]. | - | √ | - | - |

| α-Thujene | woody, herbal, spicy | Antioxidant, antimalarial, antibacterial, antimicrobial [43,44] | - | √ | √ | √ |

| Eucalyptol | fresh, camphor, spicy | Anti-inflammatory, expectorant, antimicrobial, antiseptic, insecticidal [45,46,47,48,49] | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| D-Limonene | citrusy, sweet | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antibacterial, and natural solvent of topical drugs [50,51] | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| γ-Terpinene | Herbal, citrus, spicy, fresh | Antimicrobial, antiparasitic, anticancer, antinociceptive, antiplatelet, natural preservative [52,53] | - | √ | √ | - |

| Terpineol | Floral, fresh, pine, citrusy | Antioxidant, antiproliferative [54,55] | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| α-Phellandrene | Peppery, herbal, citrusy, minty | Antifungal, immunostimulant [56,57,58] | √ | √ | √ | - |

| Borneol | Soft, woody, balsamic camphor. | anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antibacterial, antiviral, relieves pain and fever, repellent [59] | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| (+)-2-Bornanone (camphor) | Sharp, refreshing, minty camphor | anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, topical analgesic, rubefacient - improves blood circulation [14,16,17] | - | √ | √ | √ |

| Verbenone | verbena, rosemary-like | Beetle pheromone/inhibitor, anti-microbial [60,61] | - | √ | - | √ |

| Bornyl acetate | Balsamic, resin-like, sweet | Anti-inflammatory, immune modulator [62,63]. | √ | √ | - | √ |

| Copaene | Balsamic, woody, peppery, herbal | Insect-repellent, attracts/repels certain pests [64,65]. | √ | √ | - | - |

| β-Caryophyllene | Woody, spicy, dry | anti-inflammatory, anticancer, analgesic, interaction with CB2 (cannabinoid) receptors, [66,67] | - | √ | √ | √ |

| Humulene | earthy, woody, slightly spicy | anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antibacterial, [68,69] | - | √ | - | - |

| Cinnamic acid | Sweet, balsamic, cinnamon-like | anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antibacterial, antidiabetic, sunscreen and skin lightening product [70,71,72] | √ | - | √ | √ |

| Caryophyllenyl alcohol | Woody, slightly floral | anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, sedative effects [73] | - | √ | - | √ |

| Caryophyllene oxide | Woody, spicy, fresh | antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal [25,74] | - | √ | - | √ |

| Methyl cinnamate | Sweet, fruity, like strawberries | anti-inflammatory, antifungal, antimicrobial [75] | √ | √ | √ | - |

| n-Hexadecanoic acid | Waxy, faint (olive oil-like) | anti-inflammatory, prostaglandin E2 9 reductase inhibitor [76,77,78] | - | - | √ | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).