Submitted:

15 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

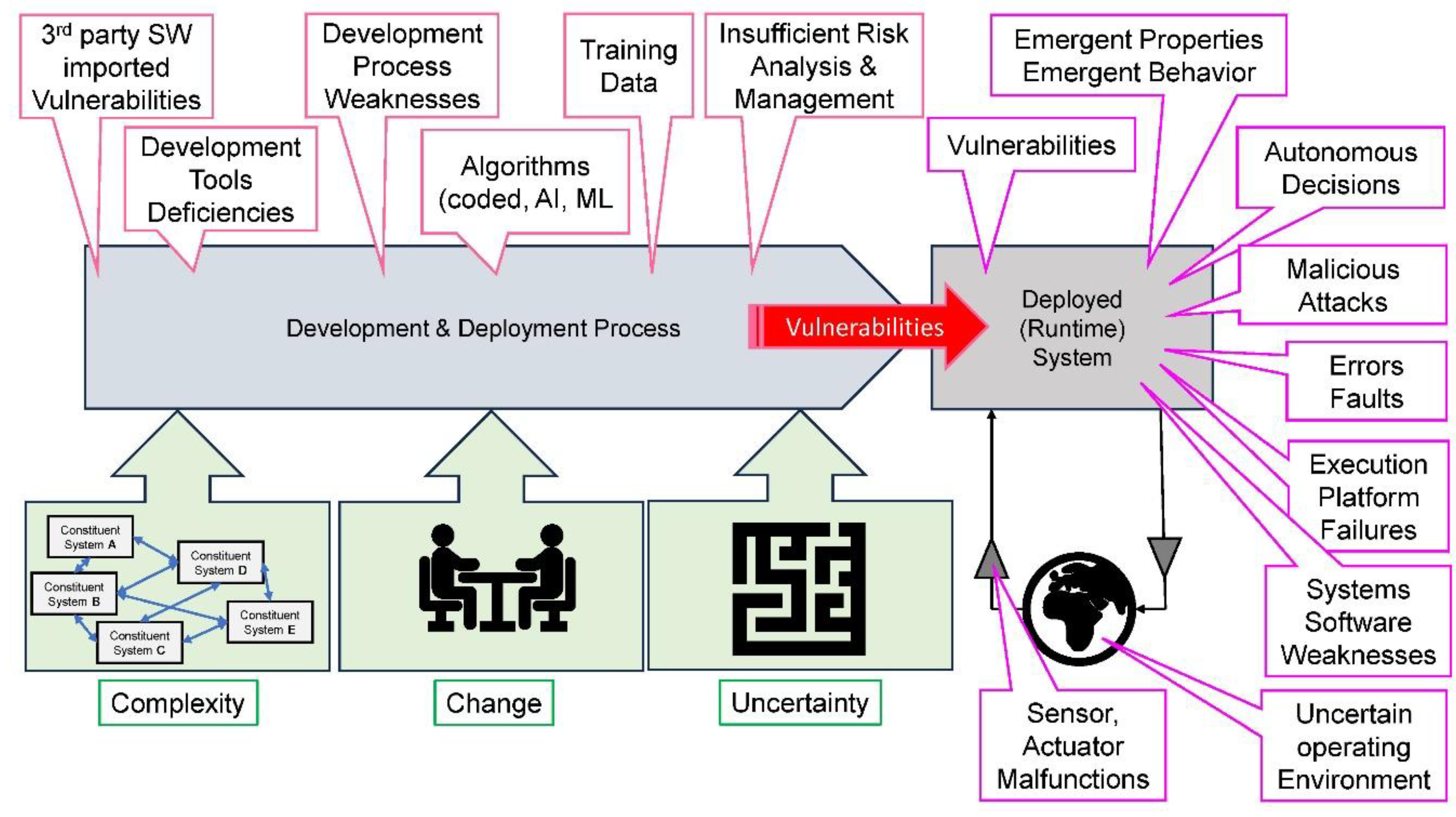

Introduction and Context

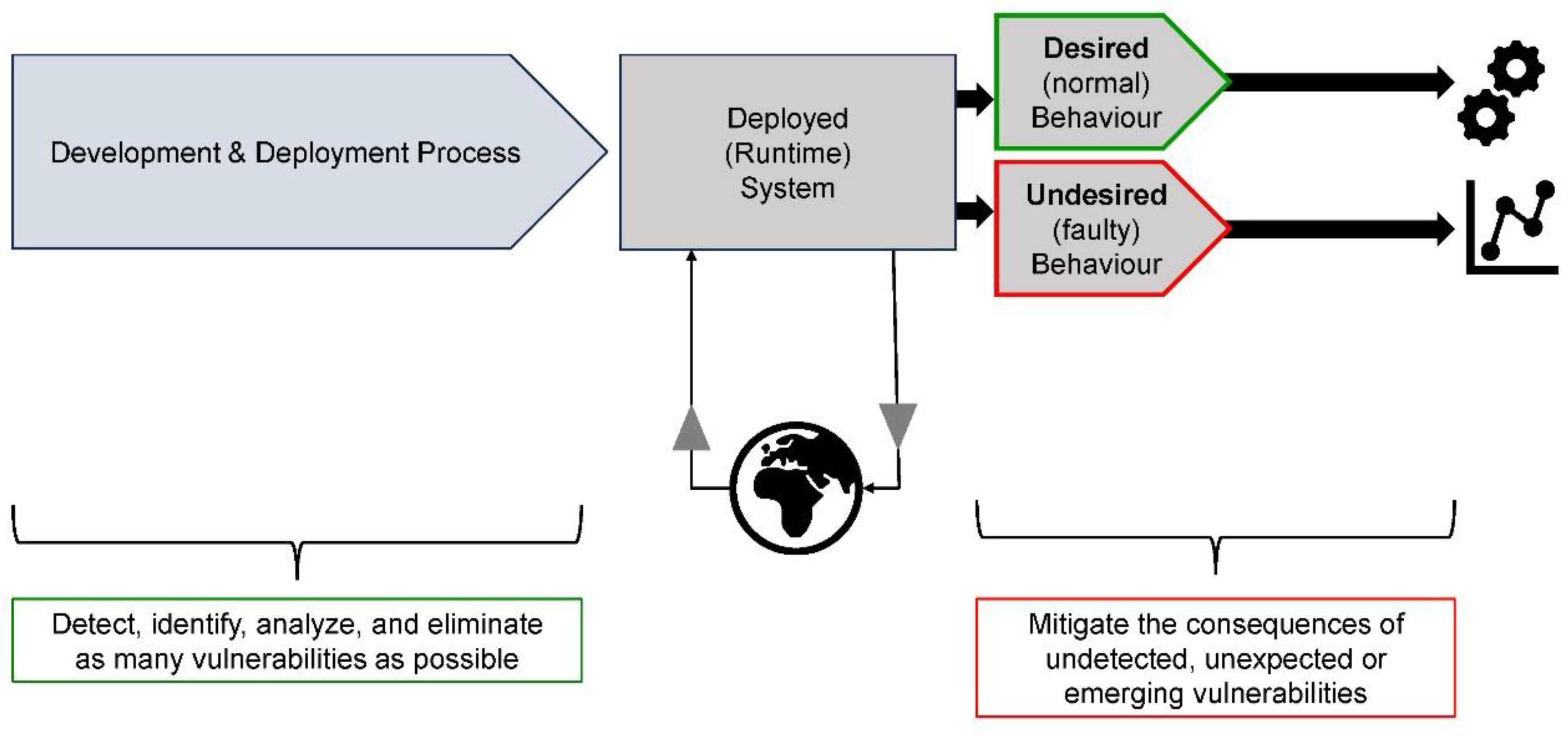

Cyber-Physical Systems Behavior

- (1)

- Desired behavior: Safe and secure operation, complete adherence to specifications, full conformance with laws and regulations, respecting all timing conditions, satisfactory handling of all errors, faults, and failures, comprehensive interaction with the user, trustworthy in all situations and operating conditions;

- (2)

- Undesired behavior: Unsafe, insecure, dangerous, incomprehensible, untrustworthy, or erratic behavior.

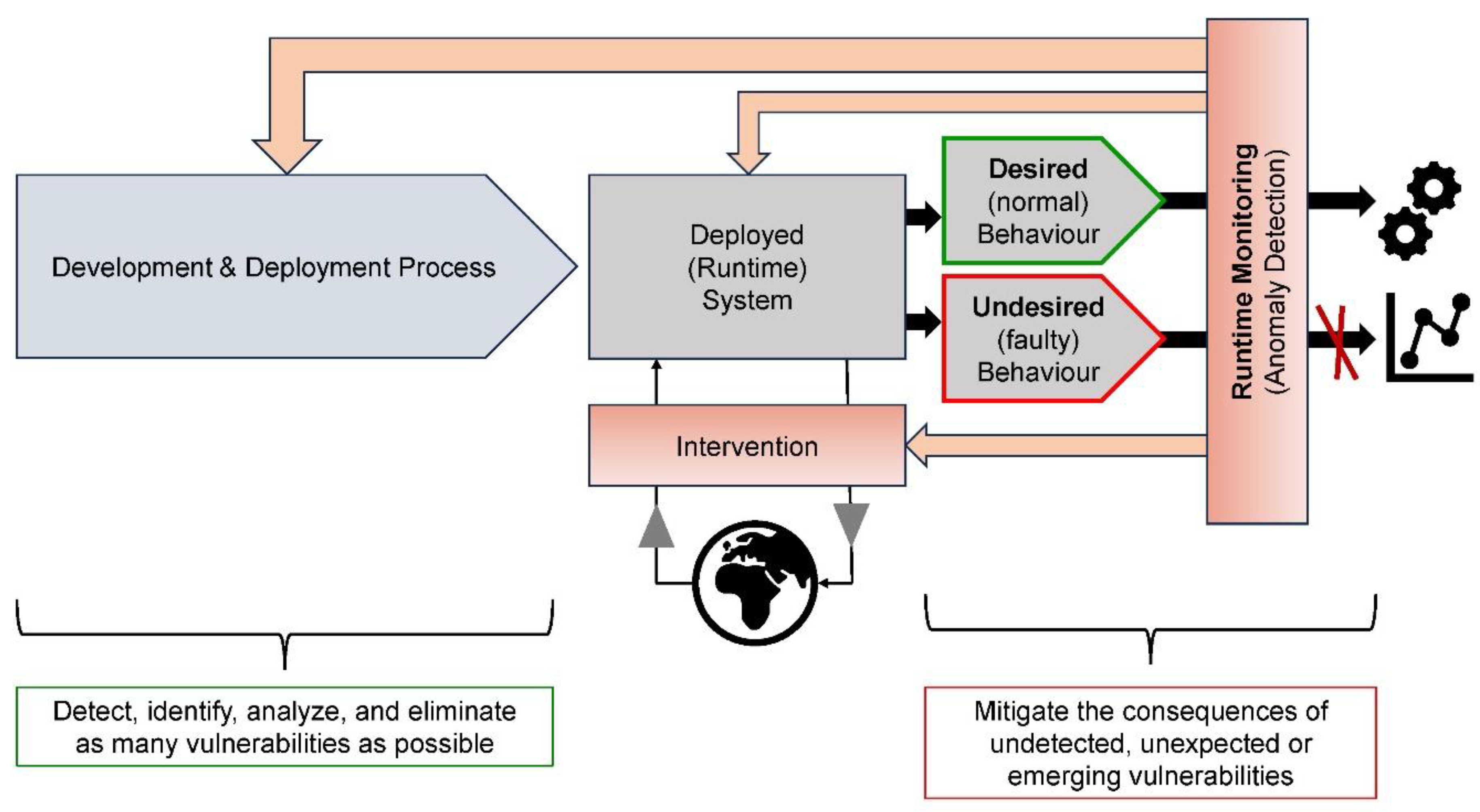

Cyber-Physical Systems Runtime Monitoring

Monitor – Analyze – Intervene

- (1)

- The deployed cyber-physical runtime system in its operating environment;

- (2)

- The anomaly detection (Symbolizing the necessary hardware and software for the application at hand);

- (3)

- The intervention planning element;

- (4)

- The intervention execution blocks.

Monitor

- Data obtained from the real world;

- Synthetic data: Data generated by algorithms, artificial intelligence, or simulations (e.g., Nikolenko, 2021 / Nassif, 2024).

Analyze

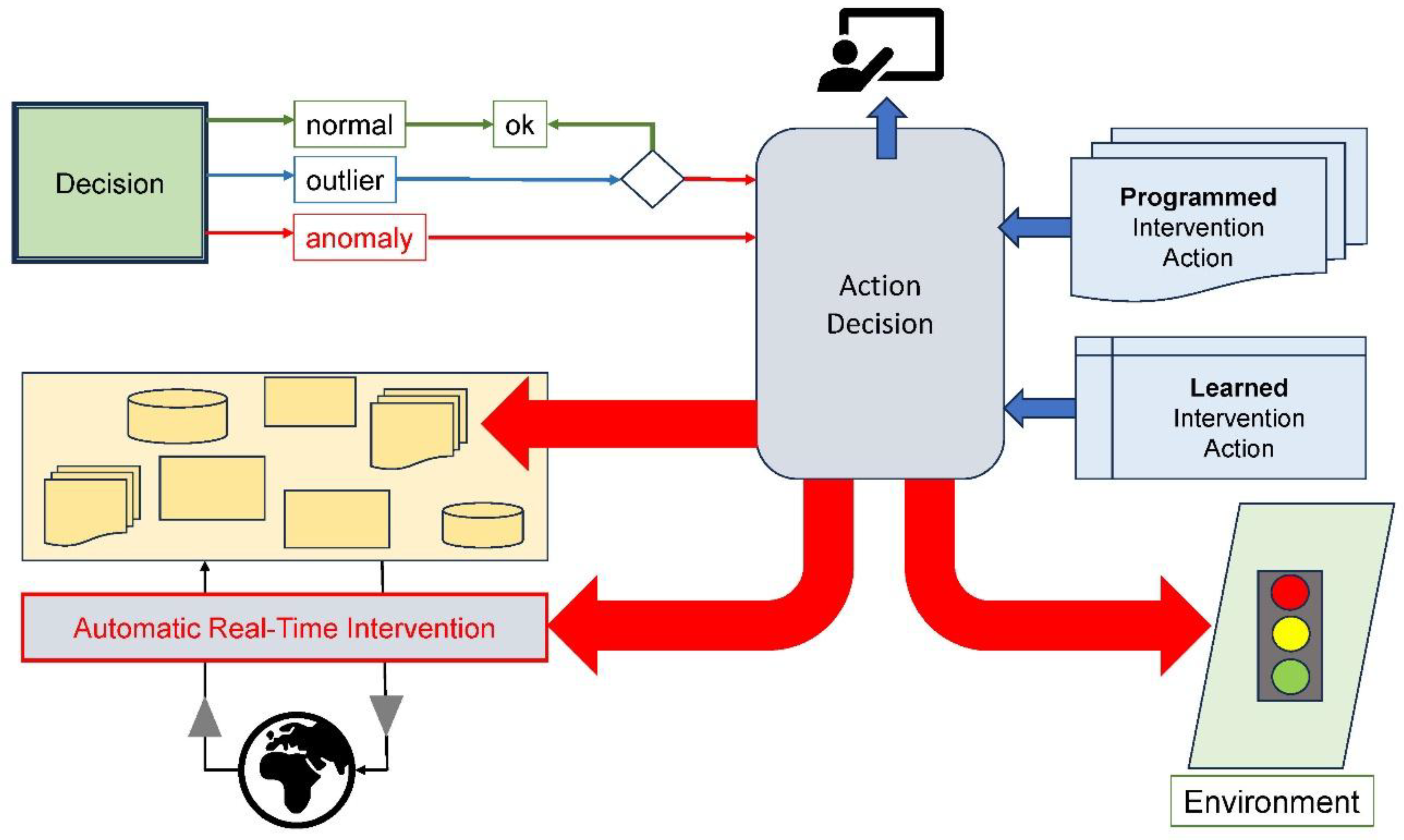

Intervene

- Directly influence the behavior of the control system, i.e., block, change, or override functionality;

- Override or correct sensor or actuator values, i.e., protect the system from harmful input or output values;

- Manipulate the operating environment of the CPS. Examples of actions are:

- Isolating a network node immediately after an unknown thread in the operating system is detected;

- Shutting down a TCP/IP port when excessive inor outbound traffic is measured;

- Taking over a ship’s control when a threatening collision course is computed;

- Setting all traffic lights by the involved car to red after an accident at the intersection;

- Automatically take evasive action when a car recognizes an imminent hit of a pedestrian, animal, or cyclist;

- Force the CPS into a safe state, e.g., trigger an emergency stop of the train;

- Switch to a safe, degraded mode of operation, e.g., limit the maximum speed of a car to 80 km/h after a failure of the antiskid control;

- Close the system access for an employee after unauthorized data access attempts;

- Contact a cardholder after untypical payment behavior is detected.

Safety: Last Defense

Security: Last Defense

- (1)

- The MIL-STD-1553 bus with the bus controller, the bus monitor, and 1…31 bus participants (= remote terminals);

- (2)

- The AI/ML learning component. The first function is a traffic generation simulator, which creates malicious traffic patterns based on a list of attack vectors. The second function is the feature extraction parameters based on a predefined feature list. The relevant feature parameters and their anomaly decision parameters, together with the decision criteria (thresholds), are then provided to the anomaly detection mechanism;

- (3)

- The anomaly detection mechanism. This mechanism monitors the bus traffic and detects anomalies using the CUSUM algorithm (Cumulative Sum, e.g., Granjon, 2014 / Koshti, 2011). This statistical change detection algorithm (Page, 1954) identifies when a time series feature deviates from a reference one. Finally, the decision mechanism – usually based on thresholds – raises an alarm if an anomaly is suspected and triggers defense mechanisms, such as isolating suspicious nodes.

Protective Shell

Extended Aflack Surface, XAI, and Robust AI

- (1)

- The protective shell increases the system’s complexity by introducing additional hardware, software, and processes. As experience shows, additional complexity also enlarges the attack surface (e.g., Cybellium Ltd., 2023), i.e., generates new failure modes (Stamatis, 2019) and enables new attack vectors (Haber et al., 2018). Unfortunately, effective kill chains, i.e., specific attack methods and tools, are readily available to strike AI systems (e.g., Gibian, 2022). A meticulous and thorough risk analysis for the protective shell is therefore required;

- (2)

- Artificial intelligence and machine learning may execute autonomous, inexplicable (although possibly correct) decisions and actions. This autonomous behavior may cause legal, audit, and regulatory issues, but it also poses the danger of harmful decisions. Therefore, safety- or security-critical AI applications must solely use explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) mechanisms! (e.g., Simon, 2023 / Huang, 2023).

- (3)

- In AI-based safety- or security-critical CPS, severe damage can result from their malfunction. Failures, malicious activities, deficient learning, and other issues can cause such malfunctions. To guard against these, the AI must be safe and robust. Fortunately, the field of safe and robust AI is developing rapidly, and sources are available (e.g., Guerraoui, 2024/Huang, 2023/Yampolskiy, 2024/ Hall et al., 2023).

Forensics and The Law

- (1)

- Defend against post-accident and post-incident unwarranted accusations;

- (2)

- Allow authoritative discovery of the causes/sources of the accidents/incidents and use them to improve the CPS.

Open Challenges

- (1)

- Authoritative and law-conforming policies covering the application of artificial intelligence/machine learning for safety and security in different fields of application and diverse organizations;

- (2)

- Dependable, transparent machine learning algorithms (Explainable AI, e.g., Mehta, 2022);

- (3)

- Reliable, consistent, and fair training data (either from the real world or simulated), including their provisioning methods;

- (4)

- Correct, timely, and effective intervention mechanisms, including their planning and decision mechanisms;

- (5)

- Collection of sufficient, meaningful, and legally acceptable forensic data (e.g., Marcella, 2021);

- (6)

- Metrics for the evaluation of the efficiency and effectiveness of AI/ML usage;

- (7)

- Defense against attacks on the AI/ML algorithms, their implementations, and training data;

The Last Question: AI Ethics

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adari S.K., Alla S. (2024): Beginning Anomaly Detection Using Python-Based Deep Learning - Implement Anomaly Detec- tion Applications with Keras and PyTorch. Apress Media, New York, NY, USA. ISBN 979-8-8688-0007-8. [CrossRef]

- Alur Rajeev (2015): Principles of Cyber-Physical Systems. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA. ISBN 978-0-262-02911-7.

- Axelrod C.W. (2012): Engineering Safe and Secure Software Systems. Artech House Books, Norwood, MA, USA. ISBN 978-1- 608-07472-3.

- Bahr N.J. (2017): System Safety Engineering and Risk Assessment: A Practical Approach. CRC Press (Taylor & Francis Group), Boca Raton, FL, USA. 2nd edition. ISBN 978-1-138-89336-8.

- Banish G. (2023): OBD-I & OBD-II - A Complete Guide to Diagnosis, Repair, and Emissions Compliance. CarTech Books, North Branch, MN, USA. ISBN 978-1-61325-752-4.

- Bartocci E., Falcone Y., Editors (2018): Lectures on Runtime Verification - Introductory and Advanced Topics. Springer Na- ture, Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-319-75631-8 (LNCS 10457).

- Beckers A., Teubner G. (2023): Three Liability Regimes for Artificial Intelligence - Algorithmic Actants, Hybrids, Crowds. HART Publishing, Oxford, UK. ISBN 978-1-5099-4937-3.

- Bhuyan H. (2018): Network Traffic Anomaly Detection and Prevention - Concepts, Techniques, and Tools. Springer Interna- tional Publishing, Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-319-87968-0.

- Bilgin E. (2020): Mastering Reinforcement Learning with Python - Build next-generation, self-learning models using rein- forcement learning techniques and best practices. Packt Publishing, Birmingham, UK. ISBN 978-1-838-64414-7.

- Burger W., Burge M., J. (2022): Digital Image Processing - An Algorithmic Introduction. 3rd edition, Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-031-05743-4. [CrossRef]

- Buttfield-Addison P., Buttfield-Addison M., Nugent T., Manning J. (2022): Practical Simulations for Machine Learning- Using Synthetic Data for AI. O’Reilly Media Inc., Sebastopol, CA, USA. ISBN 978-1-492-08992-6.

- Cockcroft A.N, Lameijer J. N. F. (2012): A Guide to the Collision Avoidance Rules. Butterworth-Heinemann, Kidlington, UK, 7th edition.

- Coeckelbergh M., 2020: AI Ethics. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA. ISBN 978-0-262-53819-0.

- Cybellium Ltd., 2023: Mastering Attack Surface Management - A Comprehensive Guide To Learn Attack Surface Manage- ment. Cybellium Ltd., Tel Aviv, Israel. ISBN 979-8-8591-4008-4.

- Dunning T., Friedman E. (2014): Practical Machine Learning - A New Look at Anomaly Detection. O’Reilly and Associates, Sebastopol, CA, USA. ISBN 978-1-491-91160-0.

- Eliot L. (2016): AI Guardian Angel Bots for Deep AI Trustworthiness - Practical Advances in Artificial Intelligence. LBE Press Publishing. ISBN 978-0-6928-0061-4.

- EU, (2021): Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down harmonised rules on Artificial Intelli- gence (Artificial Intelligence Act). European Commission, Brussels, Belgium, COM(2021) 206 final, 21.4.2021. Downloadable from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:e0649735-a372-11eb-9585-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&for- mat=PDF.

- Fidgerald J., Morisset C., (2024): Can We Develop Holistic Approaches to Delivering Cyber-Physical Systems Security? Cambridge University Press, Research Directions: Cyber-Physical Systems. https://doi:10.1017/cbp.2024.1.

- Francois-Lavet V., Henderson P., Islam R., Bellemare M.G., Pineau J. (2018): An Introduction to Deep Reinforcement Learning. Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning: Vol. 11, No. 3-4, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Furrer F.J. (2019): Future-Proof Software-Systems – A Sustainable Evolution Strategy. Springer Vieweg Verlag, Wiesbaden, Germany. ISBN 978-3-658-19937-1.

- Furrer F.J. (2022): Safety and Security of Cyber-Physical Systems. Springer Vieweg Verlag, Wiesbaden, Germany. ISBN 978-3- 658-37181-4.

- Furrer, F.J. (2023). Safe and secure system architectures for cyber-physical systems. Informatik Spektrum, 46, 96–103. [CrossRef]

- Gibian D. (2022): Hacking Artificial Intelligence - A Leader’s Guide from Deepfakes to Breaking Deep Learning. Rowman & Littlefield, London, UK. ISBN ISBN 978-1-5381-5508-0.

- Granjon P. (2014): The CUSUM algorithm. GIPSA-lab, Grenoble Campus, Saint Martin d’Hères, France. Downloadable from: https://hal.science/hal-00914697/document.

- Griffor Edward, Editor (2016): Handbook of System Safety and Security - Cyber Risk and Risk Management, Cyber Secu- rity, Threat Analysis, Functional Safety, Software Systems, and Cyber-Physical Systems. Syngress (Elsevier), Amsterdam, Netherlands. ISBN 978-0-128-03773-7.

- Guerraoui R., Gupta N., Pinot R. (2024): Robust Machine Learning - Distributed Methods for Safe AI. Springer Nature Sin- gapore, Singapore. ISBN 978-981-97-0687-7. [CrossRef]

- Haber M.J., Hibbert B., 2018: Asset Attack Vectors - Building Effective Vulnerability Management Strategies to Protect Or- ganizations. Apress Media LLC, New York, NY, USA. ISBN 978-1-4842-3626-0. [CrossRef]

- Hadeer A., Traore I., Quinan P., Ganame K., Boudar O. (2023): A Collection of Datasets for Intrusion Detection in MIL- STD-1553. {Chapter 4 in Traore et al., 2023}. [CrossRef]

- Hall P., Curtis J., Pandey P. (2023): Machine Learning for High-Risk Applications - Techniques for Responsible AI. O’Reilly Media Inc., Sebastopol, CA, USA. ISBN 978-1-098-10243-2.

- Harrison L. (2020): How to use Runtime Monitoring for Automotive Functional Safety. TechDesignForum White Paper. Downloadable from: https://www.techdesignforums.com/practice/technique/how-to-use-runtime-monitoring-for-automo- tive-functional-safety.

- Hashimoto H., Nishimura H., Nishiyama H., Higuchi G. (2021): Development of AI-based Automatic Collision Avoidance System and Evaluation by Actual Ship Experiment. ClassNK Technical Journal, No. 3, 2021. Chiba, Japan. Downloadable from: https://www.classnk.or.jp/hp/pdf/research/rd/2021/03_e05.pdf.

- Haupt N.B, Liggesmeyer P. (2019): A Runtime Safety Monitoring Approach for Adaptable Autonomous Systems. In: Ro- manovsky A., Troubitsyna E., Gashi I., Schoitsch E., Bitsch F. (Editors): Computer Safety, Reliability, and Security. SAFECOMP 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol 11699. Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland. Downloadable from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335557336_A_Runtime_Safety_Monitoring_Ap- proach_for_Adaptable_Autonomous_Systems/link/5dd2b7b0299bf1b74b4e14f7/download.

- Huang X., Jin G., Ruan W. (2023): Machine Learning Safety. Springer Nature Singapore Pte. Ltd., Singapore. ISBN 978- 981-19-6813-6. [CrossRef]

- IMO (1972): COLREG - Preventing Collisions at Sea. IMO (The International Maritime Organization), London, UK. https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Pages/Preventing-Collisions.aspx.

- Janicke H., Nicholson A., Webber S., Cau A. (2015): Run-Time-Monitoring for Industrial Control Systems. Electronics 2015, 4(4), 995-1017; Downloadable from: https://www.mdpi.com/2079-9292/4/4/995. [CrossRef]

- Johannesson P., Perjons E., 2021: An Introduction to Design Science. Springer Nature, Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-030- 78131-6. [CrossRef]

- Kane A. (2015): Runtime Monitoring for Safety-Critical Embedded Systems. Ph.D.Thesis, Carnegie Mellon University, Pitts- burgh, PA, USA. Downloadable from: https://users.ece.cmu.edu/~koopman/thesis/kane.pdf.

- Kävrestad J. (2020): Fundamentals of Digital Forensics - Theory, Methods, and Real-Life Applications. Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, Switzerland. 2nd edition. ISBN 978-3-030-38953-6. [CrossRef]

- Khan M.T., Serpanos D., Shrobe H. (2016): Sound and Complete Runtime Security Monitor for Application Software. Pre- print, arXiv:1601.04263v1 [cs.CR]. Downloadable from: https://www.researchgate.net/publica-tion/291229626_Sound_and_Complete_Runtime_Security_Monitor_for_Application_Software.

- Knight J. (2012): Fundamentals of Dependable Computing for Software Engineers. CRC Press (Taylor & Francis), Boca Raton, FL, USA. ISBN 978-1-439-86255-1.

- Koped H. (2022): An Architecture for Safe Driving Automation. In: Raskin, JF., Chatterjee, K., Doyen, L., Majumdar, R. (Edi- tors): Principles of Systems Design. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Volume 13660. Springer Nature, Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-031-22336-5. [CrossRef]

- Koshti V.V. (2011): Cumulative Sum Control Chart. International Journal of Physics and Mathematical Sciences. 2011, Vol. 1, October-December, pp.28-32. ISSN: 2277-2111. Downloadable from: https://www.researchgate.net/publica-tion/230888065_Cumulative_sum_control_chart.

- Kuo C. (2022): Modern Time Series Anomaly Detection - With Python & R Code Examples. Packt Publishing, Birmingham, UK. ISBN 979-8-363-29575-1.

- Marcella A.J., Editor (2021): Cyber Forensics - Examining Emerging and Hybrid Technologies. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA. ISBN 978-0-367-52424-1.

- Mehrotra K.G., Mohan C.K., Huang H. (2019): Anomaly Detection Principles and Algorithms (Terrorism, Security, and Computation). Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-319-88445-5.

- Mehta M., Palade V., Chatterjee I. (2022): Explainable AI - Foundations, Methodologies and Applications. Springer Nature, Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-031-12806-6. [CrossRef]

- Möller Dietmar (2016): Guide to Computing Fundamentals in Cyber-Physical Systems - Concepts, Design Methods, and Applications. Springer International Publishing, Cham, Swiderland. ISBN 978-3-319-79747-2.

- Nassif J., Tekli J., Kamradt M. (2024): Synthetic Data - Revolutionizing the Industrial Metaverse. Springer Nature, Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-031-47559-7.

- Nikolenko S.I. (2021): Synthetic Data for Deep Learning. Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3 030 75177 7.

- Oettinger W. (2022): Learn Computer Forensics - Your one-stop guide to searching, analyzing, acquiring, and securing digital evidence. 2nd edition. Packt Publishing, Birmingham, UK. ISBN 978-1-803-23830-2.

- Page E.S. (1954): Continuous Inspection Schemes. Biometrika, Vol. 41, No. 1-2, June 1954, pp. 100-115. Available at: https://security.cybellum.com/the-state-of-automotive-security-2023. [CrossRef]

- Papow, J. (2010): Glitch - The Hidden Impact of Faulty Software. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA. ISBN 978-0- 132-16063-6.

- Press L. (2024): EU Artificial Intelligence Act - The Essential Reference. Lex Press, Independently published. ISBN 979-8-8827- 1805-2.

- Rainey L.B., Jamshidi M., Editors (2018): Engineering Emergence - A Modeling and Simulation Approach. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA. ISBN 978-1-138-04616-0.

- Sachdev K., Saad H.S., Traore I., Ganame K., Boudar O. (2023): Unsupervised Anomaly Detection for MIL-STD-1553 Avi- onic Platforms using CUSUM. {Chapter 5 in Traore et al., 2023}. [CrossRef]

- Sarkis (2023): Training Data for Machine Learning - Human Supervision from Annotation to Data. O’Reilly and Associates, Sebastopol, CA, USA. ISBN 978-1-492-09452-4.

- Shen H., Hashimoto H., Matsuda A., Taniguchi Y., Terada D., Guo C. (2019): Automatic collision avoidance of multiple ships based on deep Q-learning. Applied Ocean Research, Volume 86, May 2019, Pages 268-288. [CrossRef]

- Simon C. (2023): Deep Learning and XAI Techniques for Anomaly Detection - Integrate the theory and practice of deep anomaly explainability. Packt Publishing, Birmingham, UK. ISBN 978-1-804-61775-5.

- Stamatis D.H., 2019: Risk Management Using Failure Mode And Effect Analysis (FMEA). Quality Press, Milwaukee, MI, USA. ISBN 978-0-8738-9978-9.

- Stewart A., J. (2021): A Vulnerable System - The History of Information Security in the Computer Age. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, USA. ISBN 978-1-501-75894-2.

- Traore I., Woungang I., Saad S., Editors (2023): Artificial Intelligence for Cyber-Physical Systems Hardening. Springer Na- ture, Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-031-16239-8. [CrossRef]

- Vaseghi S., V. (2000): Advanced Digital Signal Processing and Noise Reduction. 2nd edition, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK. ISBN 978-0-4716-2692-3.

- VC3 Corporation (2023): The Evolution of Artificial Intelligence in Cybersecurity. VC3 Corporation, Columbia, SC, USA. Downloadable from: https://www.vc3.com/blog/the-evolution-of-artificial-intelligence-in-cybersecurity.

- Winder P. (2020): Reinforcement Learning - Industrial Applications of Intelligent Agents. O’Reilly Media, Sebastopol, CA, USA. ISBN 978-1-098-11483-1.

- Winkle T. (2022): Product Development within Artificial Intelligence, Ethics, and Legal Risk - Exemplary for Safe Autono- mous Vehicles. Springer Fachmedien Vieweg, Wiesbaden, Germany. ISBN 978-3-658-34292-0. [CrossRef]

- Yampolskiy R.V. (2024): AI - Unexplainable, Unpredictable, Uncontrollable. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, CA, USA. ISBN 978-1-032-57626-8. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).