1. Introduction

Cyber security is a fast-evolving discipline, and threat actors are constantly endeavouring to stay ahead of security teams with new and sophisticated techniques. The use of interconnected devices and accessing data ubiquitously has increased exponentially, raising more security concerns. Traditional security solutions are becoming inadequate in detecting and preventing sophisticated attacks. However, advances in cryptographic and Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques show promise in enabling cyber security experts to counter such attacks [

1]. AI is being leveraged to solve a number of problems using chatbots to virtual assistants and automation, allowing humans to focus on higher-value work but also used for predictions, analytics, and cyber security.

Recovery from a data breach costs

$4.35 million on average and takes 196 days [

2]. Organisations are increasingly investing in cyber security, adding AI enablement to improve threat detection, incident response (IR) and compliance. Patterns in data can be recognised using Machine Learning (ML), monitoring, and threat intelligence to enable systems learn from the past events. It is estimated that AI in the cyber security market will be worth

$102.78 billion by 2032 globally [

3]. Currently, different initiatives are defining new standards and certifications to elicit users’ trust in AI. The adoption of AI can improve best practices and security posture, but also create new forms of attacks. Therefore, secure, trusted and reliable AI is necessary by integrating security in design, development, deployment, operation and maintenance stages.

Failures of AI systems are becoming common, it is crucial to understand and prevent them as they occur [

4,

5]. Failures in general AI have a higher impact than in narrow AI, but a single failure in a superintelligent system might result in a catastrophic disaster with no prospect of recovery. AI safety can be improved with cyber security practices, standards, and regulations. Its risks and limitations should also be understood, and solutions should be developed. Systems commonly experience recurrent problems with scalability, accountability, context, accuracy, and speed in the field of cyber security [

6]. The inventory of ML algorithms and techniques have to be explored through the lens of security. Considering the fact that AI can fail, there should be models in place to make AI decisions explainable [

7].

This paper explores AI and cyber security with use cases and practical concepts in a real-world context based on field experience of the authors. It gives an overview on how AI and cyber security empower each other symbiotically. It discusses the main disciplines of AI and how they can be applied to solve cyber security complex problems and challenges of data analytics. It highlights the need to evaluate both AI for security and security for AI to deploy safe, trusted, secure AI-driven applications. Furthermore, it develops an algorithm and a predictive model, Malicious Alert Detection System (MADS) to demonstrate AI applicability. It evaluates the model’s performance. Proposes methods to address AI-related risks, limitations and attacks. Explores evaluation techniques and recommends a safe and successful adaption of AI.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on AI and cyber security. In

Section 3, the security objectives and AI foundational concepts are presented.

Section 4 discusses how AI can be leveraged to solve security problems. The utilisation of ML algorithms for security use cases are presented in

Section 6.

Section 5, presents a case study of a predictive model MADS and AI evaluation techniques. The risk and limitations of AI are discussed in

Section 7. The paper is concluded with remarks in

Section 8.

2. Background

Security breaches and loss of confidential data are still big challenges for organisations. The spike in cyber threats has been triggered by the migration of data to the cloud, such as health, financial records and digitalisation of social interactions [

8]. Similarly, sensors and industrial devices that were off the grid are now being connected to enterprise networks through Industrial Control Systems (ICS) and the Internet of Things (IoT) [

9]. Traditional approaches to protect this data are no longer adequate. With the increased sophistication of modern attacks, there is a need to detect malicious activities, but also to predict the steps that will be taken by an adversary. This can be achieved with the utilisation of AI by applying it to use cases such as authentication, anomalous behaviour, traffic monitoring and situation awareness [

10].

Current AI research involves search algorithms, knowledge graphs, Natural Languages Processing (NLP), expert systems, ML, and Deep Learning (DL), while the development process includes perceptual, cognitive, and decision-making intelligence. The integration of cyber security with AI has huge benefits, such as improving the efficiency of security systems, performance, and providing better protection from cyber threats. It can improve an organisation’s security maturity by adopting a holistic view of combining AI with human insight. Thus, socially responsible use of AI is essential to further mitigate related concerns [

11].

The speed of processes and the amount of data used in defending cyberspace cannot be handled without automation. AI techniques are being introduced to construct smart models for malware classification, intrusion detection and threat intelligence gathering [

12]. Nowadays, it is difficult to develop software with conventional fixed algorithms to defend against dynamically evolving cyber attacks [

13]. AI can provide flexibility and learning capability to software development. However, threat actors have also figured out how to exploit AI and use it to carry out new attacks.

ML methods are vulnerable to adversarial learning attacks, which aim at decreasing the effectiveness of threat detection [

14]. These attacks are also effective when targeting Neural Networks (NN) policies in Reinforcement Learning (RL) [

15]. AI models are facing threats that disturb their data, learning, and decision-making. Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) can be utilised to optimize security defence against adversaries using proactive and adaptive countermeasures [

16].

The use of a recursive algorithm, DL, and inference in NN have enabled inherent advantages over existing computing frameworks [

17]. AI-enabled applications can be combined with human emotions, cognitions, social norms, and behavioural responses [

18] to improve societal issues. However, the use of AI can also lead to ethical and legal issues, which are already big problems in cyber security. There are significant concerns to data privacy and applications’ transparency because of the severe ambiguity of the current ethical frameworks. It’s also important to address the criminal justice issues related to AI usage, liability, and damage compensation.

2.1. Artificial Intelligence

A system to be considered to have AI capability, must have at least one of the six foundational capabilities to pass the Turing Test [

19] and the Total Turing Test [

20]. These give AI the ability to understand the natural language of a human being, store and process information, reason, learn from new information, see and perceive objects in the environment, manipulate and move physical objects. While some advanced AI agents may possess all six capabilities.

The advancements of AI will accelerate, making it more complex and ubiquitous, leading to the creation of a new level of AI. There are three levels of AI [

21]:

Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI): The first level of AI that specialises in one area, cannot solve problems in other areas autonomously.

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI): AI that reaches the intelligence level of a human, having the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly, and learn from experience.

Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI): AI that is far superior to the best human brain in all cognitive domains, such as creativity, knowledge, and social abilities.

Even ANI has been able to disrupt technology unexpectedly, such as Generative AI, chatbots and predictive models. AI enables security systems such as Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) and Intrusion Detection System (IDS) to store, process and learn from huge amounts of data [

22,

23]. This data is ingested from network devices, workstations, and Application Programming Interface (API), which is used to identify patterns such as sign-in logs, locations, time-zone, connection types and abnormal behaviours. These applications can take actions using the associated sign-in risk score and security policies to automatically block login attempts or enforce strong authentication requirements [

24].

2.1.1. Learning and Decision-Making

The discipline of learning is the foundation of AI, the ability to learn from input data moves systems away from the rule-based programming approach. An AI-enabled malware detection system operates differently from a traditional signature-based system. Rather than relying on a predefined list of virus signatures, the system is trained using data to identify abnormal program execution patterns known as behavior-based or anomaly detection, which is a foundational technique used in malware and intrusion detection systems [

25].

In the traditional approach, a software engineer identifies all possible inputs and conditions that software will be subjected to, but if the program receives an input that it is not designed to handle, it fails [

26]. For instance, searching for a Structured Query Language (SQL) injection in server logs, in the programming approach the vulnerability scanner will continuously look for parameters that are not within limits [

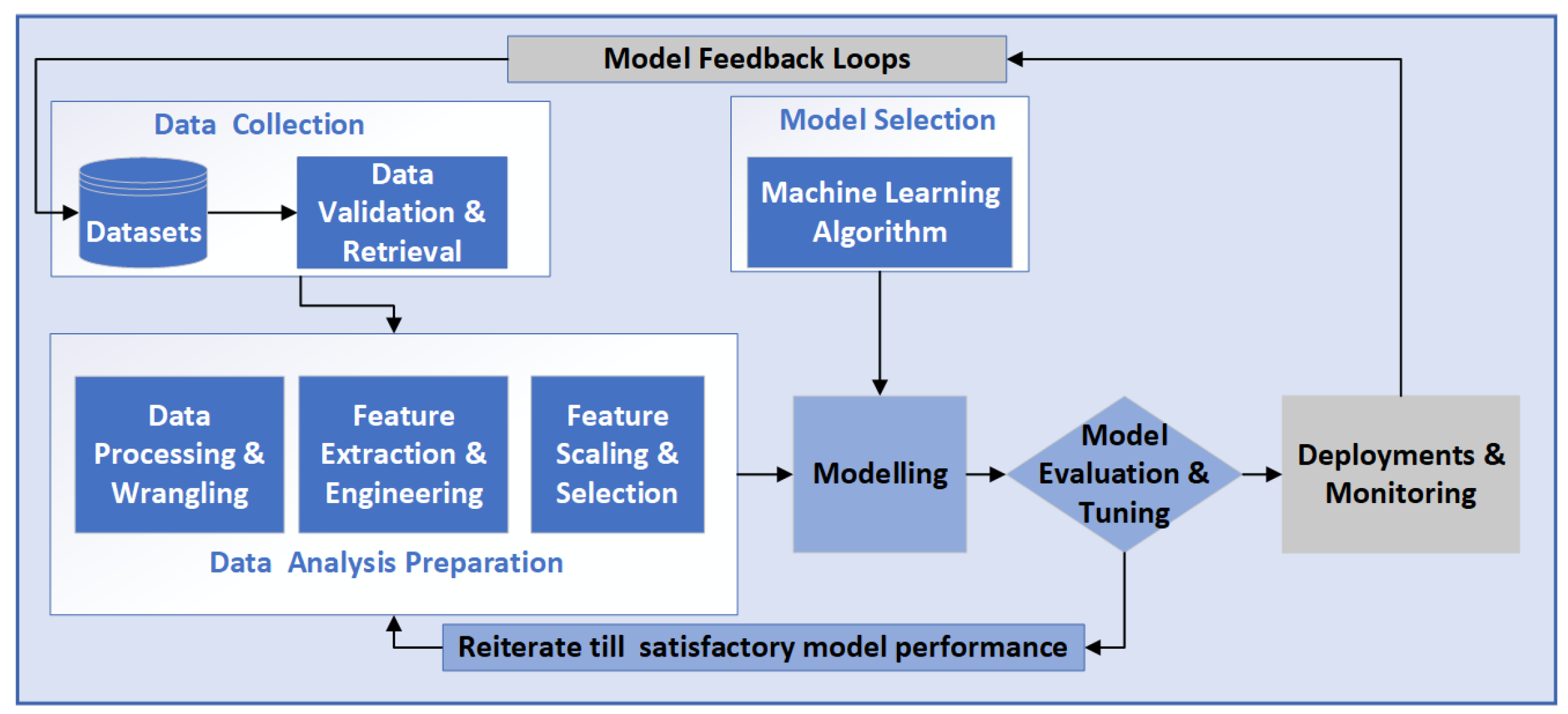

27]. It is also complicated to manage multiple vulnerabilities with traditional vulnerability management methods. However, an intelligent vulnerability scanner foresees the possible combinations and ranges, using a learning-based approach. The training data like source code or program execution context is fed to the model to learn and act on new data following the ML pipeline in

Figure 1 [

28].

2.1.2. Artificial Intelligence and Cyber Security

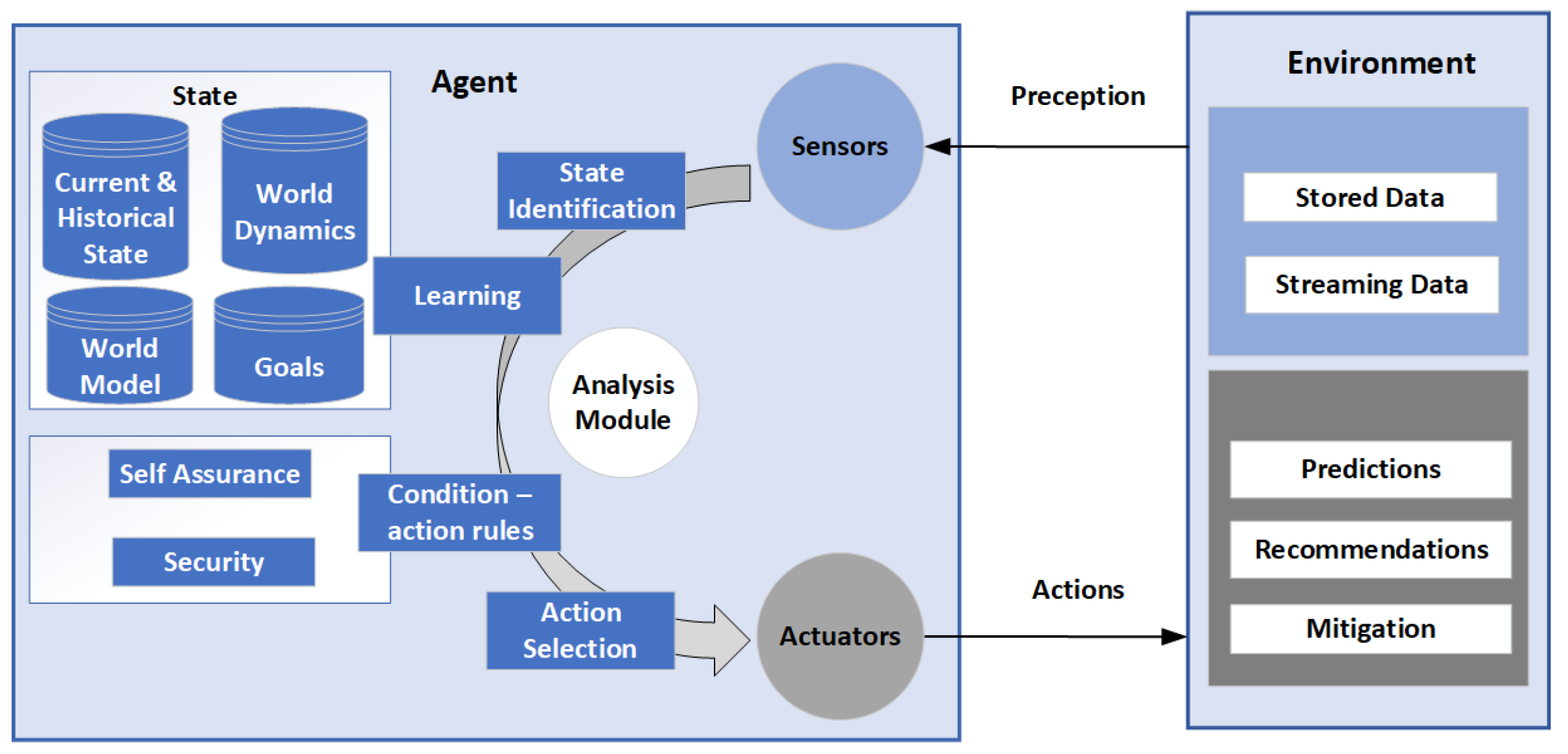

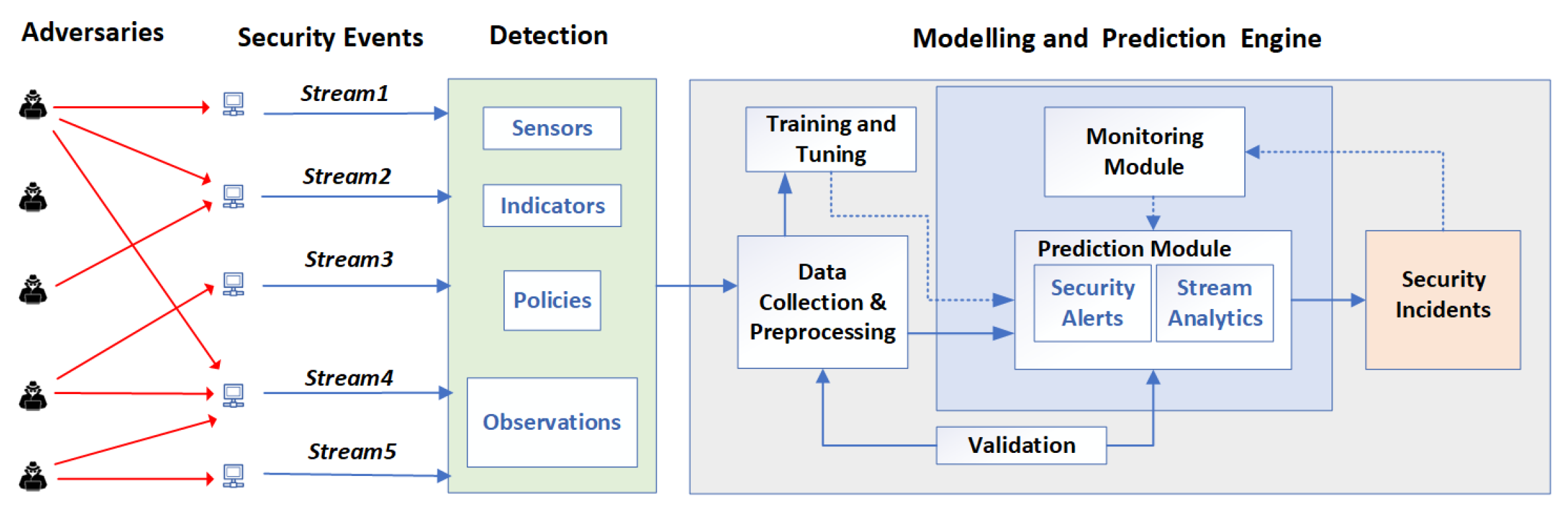

An intelligent agent is used to maximize the probability of goal completion. It is fed huge amounts of data, learns patterns, analyses new data and presents it with recommendations for analysts to make decisions as shown in

Figure 2 [

29]. AI can be used to complement traditional tools together with policies, process, personnel, and methods to minimize security breaches.

Utilising AI can improve the efficiency of vulnerability assessment with better accuracy and make sense of statistical errors such as False Positive (FP) and False Negative (FN) [

30]. Threat modelling in software development is still a manual process that requires security engineers’ input [

31,

32]. Applying AI to threat modelling still needs more research [

33], but AI has already made a great impact on threat detection [

6,

29]. It is also being utilised in IR, providing information about attack behaviour, threat actor (TA)’s Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs), and threat context [

34].

3. Objectives and Approaches

This section explores foundational concepts, objectives and approaches to cyber security.

3.1. Systems and Data Security

The main security objective of an organisation is to protect its systems and data from threats by providing Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability (CIA). Security is enforced by orchestrating frameworks of defensive techniques [

35,

36], embedded in the organisation’s security functions to align with business objectives. Applying controls that protect the organisation’s assets using traditional and AI-enabled security tools.

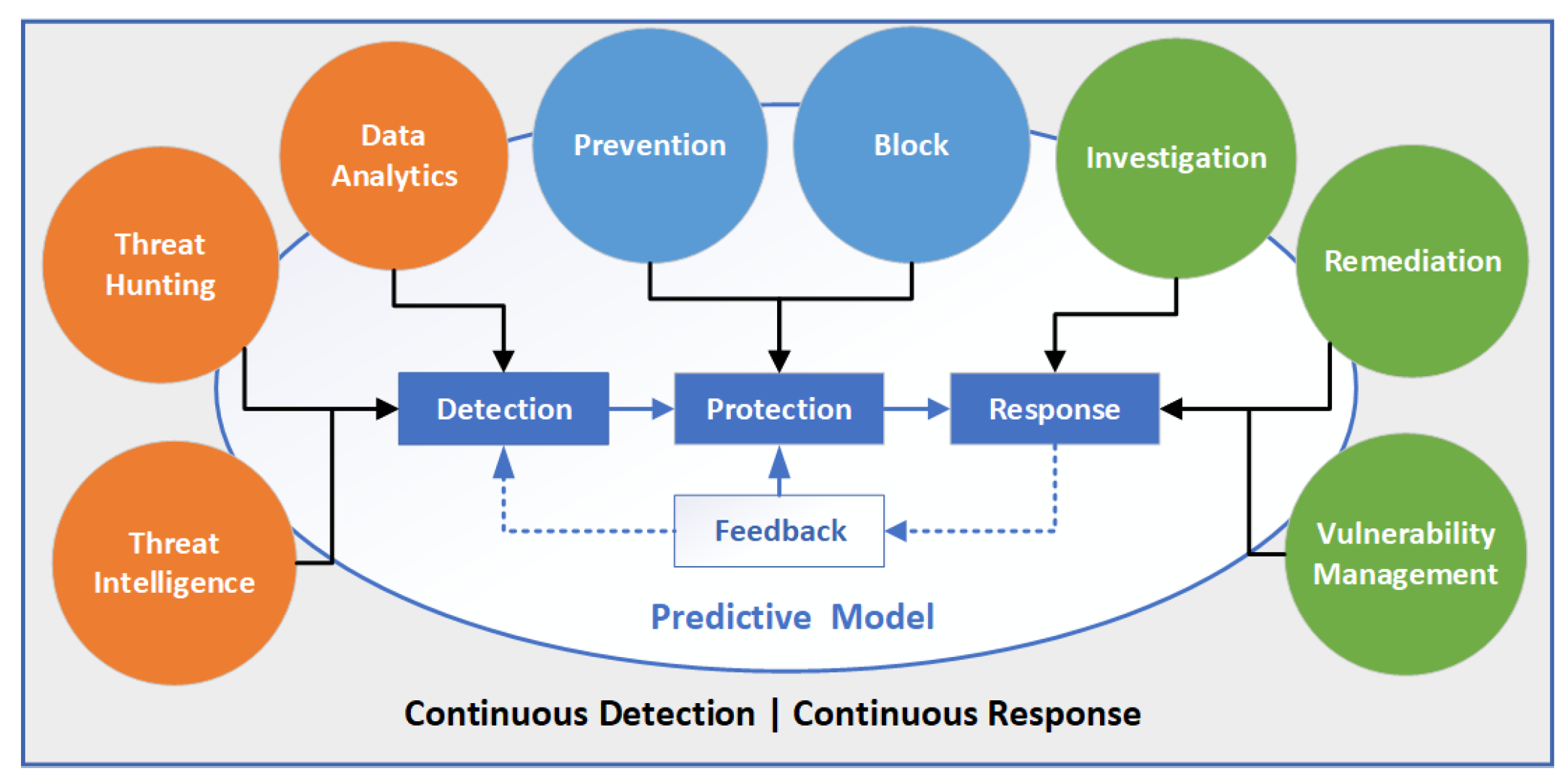

This enables security teams to identify, contain and remediate any threats with lessons learned for feedback to fine-tune the security controls. The feedback loop is also used for retraining ML models with new threat intelligence, newly-discovered behaviour patterns, and attack vectors as shown in

Figure 3. In addition, orchestrating security frameworks needs a skilled team but there is a shortage of such professionals [

37]. Therefore, a strategic approach to employment, training and education of the workforce is required. Moreover, investment in secure design, automation, and AI can augment the security teams and improve efficiency.

3.2. Security Controls

A security incident is prevented by applying overlapping administrative, technical, and physical controls complemented with training, and awareness across the organisation as shared responsibility. The security policies should be clearly defined, enforced, and communicated throughout the organisation [

38], championed by the leadership. Threat modelling, secure designing and coding best practices must be followed together with vulnerability scanning of applications and systems [

39]. Defence in-depth controls must be applied to detect suspicious activities and monitor TAs’ TTPs, unwarranted requests, files integrity, system configurations, malware, unauthorised access, social engineering, unusual pattern, user behaviour and inside threat [

40].

When a potential threat is observed, the detection tool should alert in real-time so that the team can investigate and correlate events to assist in decision-making and response to the threat [

41], utilising tools like EDR, Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) and Security Orchestration, Automation and Response (SOAR). These tools provide a meaningful context about the security events for accurate analysis. If it is a real threat, the impacted resource can be isolated and contained to stop the attack from spreading to unaffected assets following the IR plan [

42].

4. Cyber Security Problems

This section discusses security problems and how AI can improve cyber security by solving pattern problems.

4.1. Improving Cyber Security

Traditional network security was based on creating security policies, understanding the network topography, identifying legitimate activity, investigating malicious activities and enforcing a zero-trust model. Large networks may find this tough, but enterprises can use AI to enhance network security by observing network traffic patterns and advising functional groupings of workloads and policies. The traditional techniques use signatures or Indicators of Compromise (IOC) to identify threats, this is not effective to unknown threats. AI can increase detection rates, but also increase FPs [

43]. The best approach is combining both traditional and AI techniques, which can result in a better detection rate and minimizing FPs. Integrating AI with threat hunting can improve behavioural analytics, visibility, and develop applications and users’ profiles [

44].

AI-based techniques like User and Event Behavioural Analytics (UEBA) can analyse the baseline behaviour of user accounts, and endpoints, and identify anomalous behaviour such as a zero-day attack [

45]. AI can optimize and continuously monitor processes like cooling filters, power consumption, internal temperatures, and bandwidth usage to alert of any failures and provide insights into valuable improvements on the effectiveness and security of the infrastructure [

46].

4.2. Scale Problem and Capability Limitation

TAs are likely to leave a trail of their actions and security teams use the context from data logs to investigate any intrusion, but this is very challenging. They also rely on tools like IDS, anti-malware, and firewalls to expose suspicious activities, but these tools have limitations as some are rule-based and do not scale well in handling massive amounts of data.

IDS constantly scans for signatures by matching known patterns in the malicious packet flow or binary code. If it fails to find a signature in the database, it will not detect the intrusion and the impending attack will stay undetected. Similarly, to identify attacks such as brute force or Denial of Service (DoS), it has to go through large amounts of data over a period of time [

47] and analyse attributes such as source Internet Protocol (IP) addresses, ports, timestamps, protocols and resources. This may lead to a slow response or incorrect correlation by the IDS algorithm.

The use of ML models improves detection and analysis in IDS. It can identify and model the real capabilities and circumstances required by attackers to carry out successful attacks. This can harden defensive systems actively and create new risk profiles [

23]. A predictive model can be created by training on data features that are necessary to detect an anomaly and determine if a new event is an intrusion or benign activity [

48].

4.3. Problem of Contextualisation

Organisations must ensure that employees do not share confidential information with undesired recipients. Data Loss Prevention (DLP) solutions are deployed to detect, block and alert if any confidential data is crossing the trusted parameter of the network [

49]. Traditional DLP uses a text-matching technique to look for patterns against a set of predetermined words or phrases [

50]. However, if the threshold is set too high, it can restrict genuine messages and if set too low confidential data such as personal health records might end up in users’ personal cloud storage, violating user acceptable and data privacy policies.

An AI-enabled DLP can be trained to identify sensitive data based on the context [

51]. The model is fed words and phrases to protect, such as intellectual property, personal information [

52] and unprotected data that must be ignored. Additionally, it is fed information about semantic relationships among the words using embedding technique and then trained using algorithms such as Naive Bayes. The model will be able to recognize the spatial distance between words and assign a sensitivity level to a document and make a decision to block the transmission and generate a notification [

53].

4.4. Processes Duplication

TAs change their TTPs often [

36] but most security practices remain the same, with repetitive tasks that lead to complacency and missing of tasks [

54]. The AI-based approach can check duplicative processes, threats and blind spots on the network that could be missed by the analyst. AI self-adaptive access control can prevent duplication of medical data with smart, transparent, accountable secure duplication method [

55].

To identify the timestamp of attack payload delivery, the user’s device log data is analysed for attack prediction by pre-processing the dataset and creating DL classification to remove duplicate and missing values [

56].

4.5. Observation Error Measurement

There is a need for accuracy and precision when analysing potential threats, as a TA has to be right only once to cause significant damage, while a security team has to be right every time [

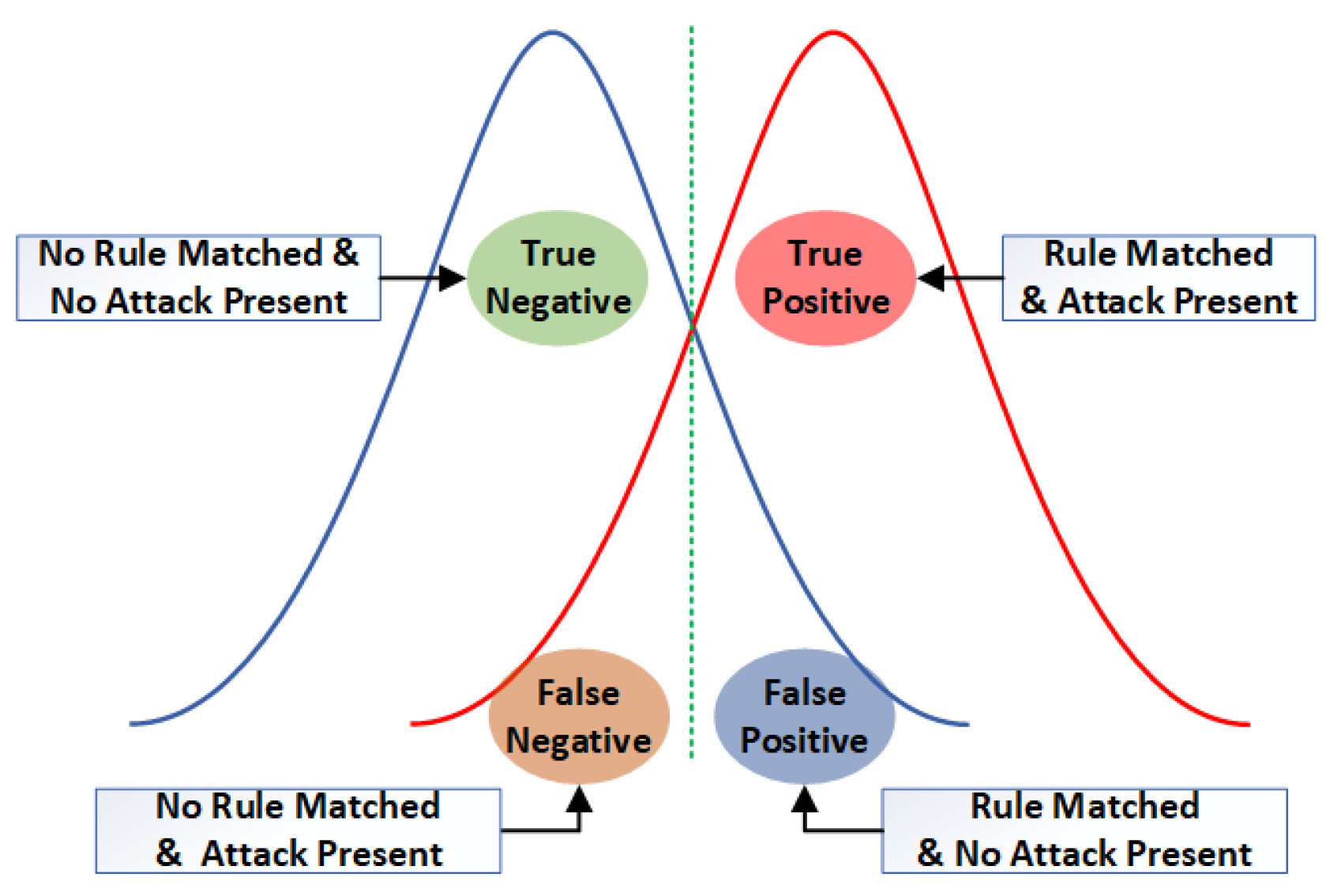

54]. Similarly, if a security team discovers events in the log files that point to a potential breach, validation is required to confirm if it is a True Positive (TP) or FP. But validating false alerts is inefficient, a waste of resources and distracts the security team from real attacks [

57].

An attacker can trick a user into clicking on a Uniform Resource Locator (URL) that leads to a phishing site that asks for user name and password [

58]. Traditional controls are blind to phishing attacks, and phishing emails look more credible nowadays. These websites are found by comparing their URL against block lists [

59], which get outdated quickly, leading to statistical errors as shown in

Figure 4. Moreover, a genuine website might be blocked due to wrong classification or a new fraud website might not be detected. This requires an intelligent solution to analyse a website on different dimensions and characterize it correctly, based on its reputation, certificate provider, domain records, network characteristics and site content. A train model can use these features to learn and accurately categorise, detect, block and report new phishing patterns [

60].

4.6. Time to Act

A security team should go through the logs quickly and accurately, otherwise a TA could get into the system and exfiltrate data without being detected. Today’s adversaries take advantage of the noisy network environment, and they are patient, persistent, and stealth [

61]. The AI-based approach can help to predict future incidents and act before they occur with reasonable accuracy, by analysing the users’ behaviour and security events whether the pattern is an impending attack or not.

A predictive model uses events, data collected, processed and validated with new data to ensure high prediction accuracy as shown in

Figure 5. It learns from previous logins by users’ behaviour, connection attributes, device location, time and attacker’s specific behaviour to build a pattern and predict malicious events. For each authentication attempt, the model estimates the probability of it being a suspicious and risky login [

45].

5. Machine Learning Applications

This section explores ML algorithms that power the AI sphere. The collected data can be labelled or unlabelled depending on the method used such as supervised, semi-supervised, unsupervised, RL [

62] and pattern representation can be solved using classification, regression, clustering and generative techniques.

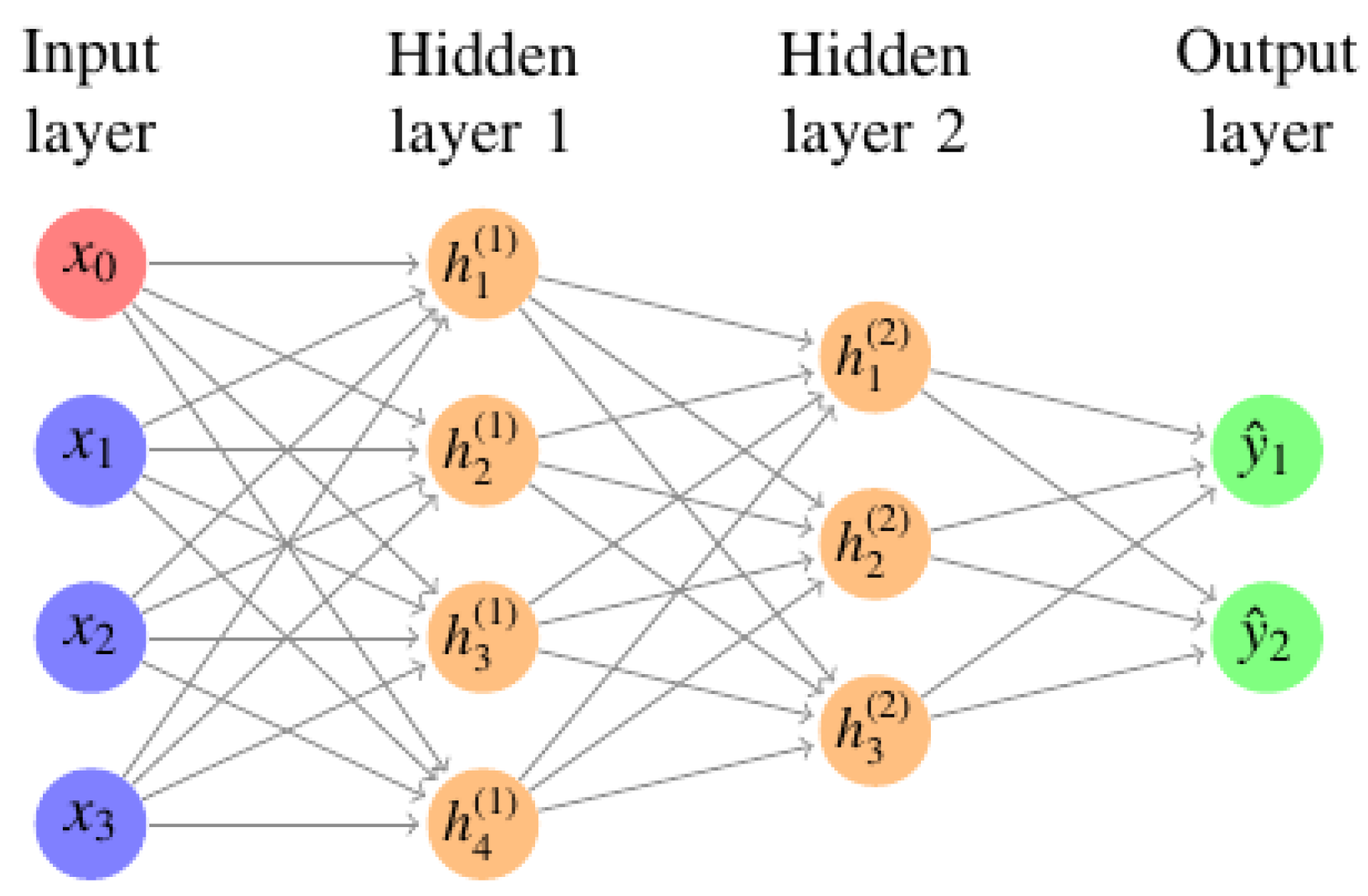

The discipline of learning is one of the capabilities that is exhibited by an AI system. ML uses statistical techniques and modelling to perform a task without programming [

63], whereas DL uses a layering of many algorithms and tries to mimic the Neural Networks (NN) [

64] as shown in

Figure 6. When building an AI solution, the algorithm used depends on training data available, and the type of problem to be solved. Different data samples are collected, and data whose characteristics are fully understood and known to be legitimate or suspicious behaviour is known as labelled data. Whereas data that is not known to be good or bad, and not be labelled is known as unlabelled data.

To train ML model using labelled data, knowing the relationship between the data and desired outcome is supervised learning, whereas when a model discovers new patterns within unlabelled data is unsupervised learning [

65]. In RL, an intelligent agent is rewarded for desired behaviours or punished for undesired ones. The agent has the capacity to perceive and understand its surroundings, act, and learn through mistakes [

66].

Since an algorithm is chosen based on the type of problem being solved and for cyber security, ML is commonly applied to predict future security events based on the information available from past events. Categorizing the data into known categories, such as normal versus malicious. Finding interesting and useful patterns in the data that could not be found like zero-day threats. While generating adversarial synthetic data that is indistinguishable from the real data is achieved by defining the problem to solve, data availability and choosing a subset of algorithms for experiment [

67].

5.1. Classification of Events

Classification segregates new data into known categories and its modelling approximates a mapping function

from input variables

to discrete output variables

, its output variables are called labels or categories [

68]. The mapping function predicts the category for a given observation. Events should be segregated into known categories, such as whether the failed login attempt is from an expected user or an attacker, and this falls under the classification problem [

63]. This can be solved with supervised learning and logistic regression or K-Near Neighbors (k-NN) and it requires labelled data. Equation

1 is a logistic function that can be utilised to find probability prediction. It takes in a set of features

x and outputs a probability

.

where

and

are the parameters of the logistic regression model. The parameters

and

are learned from the training data.

5.2. Prediction by Regression

Regression predictive modelling approximates a mapping function

from input variables

to a continuous output variable

, which is a real-value [

69] and the output of the model is a numeric variable. Regression algorithms can be used to predict the number of user accounts that are likely to be compromised [

70], the number of devices that may be tampered with or the short-term intensity and the impact of a Distributed DoS (DDoS) attack in the network [

71]. A simple model can be generated using linear regression with a linear equation between output variable (

Y), and input variable (

X), to predict a score for newly identified vulnerability in an application. To predict value of (

Y), put in a new value of (

X) using equation

2 for simple linear regression.

where

y is the predicted value,

is the intercept and the value of

y when

x is 0.

is the slope,

x is the independent variable, where

is the change in

y for a unit change in

x. The

is the error term, the difference between the predicted value and the actual value. Whereas, algorithm like support vector regression is used to build more complex models around a curve rather than a straight line. Regression Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) are applicable to intrusion detection and prevention, zombie detection, malware classification and forensic investigations [

13].

5.3. Clustering Problem

Clustering is considered where there is no labelled data and useful insights need to be drawn from untrained data using clustering algorithms such as Gaussian distributions. It groups data with similar characteristics but were not known before. For instance, finding interesting patterns in logs to benefit a security task with a clustering problem [

23]. Clusters are generated using cluster analysis [

72], instances in the same cluster must be similar as much as possible and instances in the different clusters must be different as much as possible. Measurement for similarity and dissimilarity must be clear with a practical meaning [

73], this is achieved with distance

3 and similarity

4 functions.

where

is the

element of

vector,

is the

element of

vector,

d is the dimension of the vectors, and

n is the power to which the absolute values are raised.

where

is the intersection of sets

A and

B,

is the union of the sets

A and

B, and

is the size of set

x.

For clustering pattern recognition problem, the goal is to discover groups with similar characteristics with algorithms such as K-means [

74]. Whereas anomaly detection problem, the goal is to identify the natural pattern inherent in data and then discover the deviation from the natural [

75]. For instance, to detect suspicious program execution, an unsupervised anomaly detection model is built using file access and process map as input data based on algorithms like Density-based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (DBSCAN).

5.4. Synthetic Data Generation

The generation of synthetic data has become accessible due to the advance of rendering pipelines, generative adversarial, fusion models and domain adaptation methods [

76]. Generating new data to follow the same probability distribution function and same pattern as the existing data, can increase data quality, scalability and simplicity. It can be applied to steganography, data privacy, fuzz and vulnerability testing of applications [

77]. Some of the algorithms used are Markov chains and Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) [

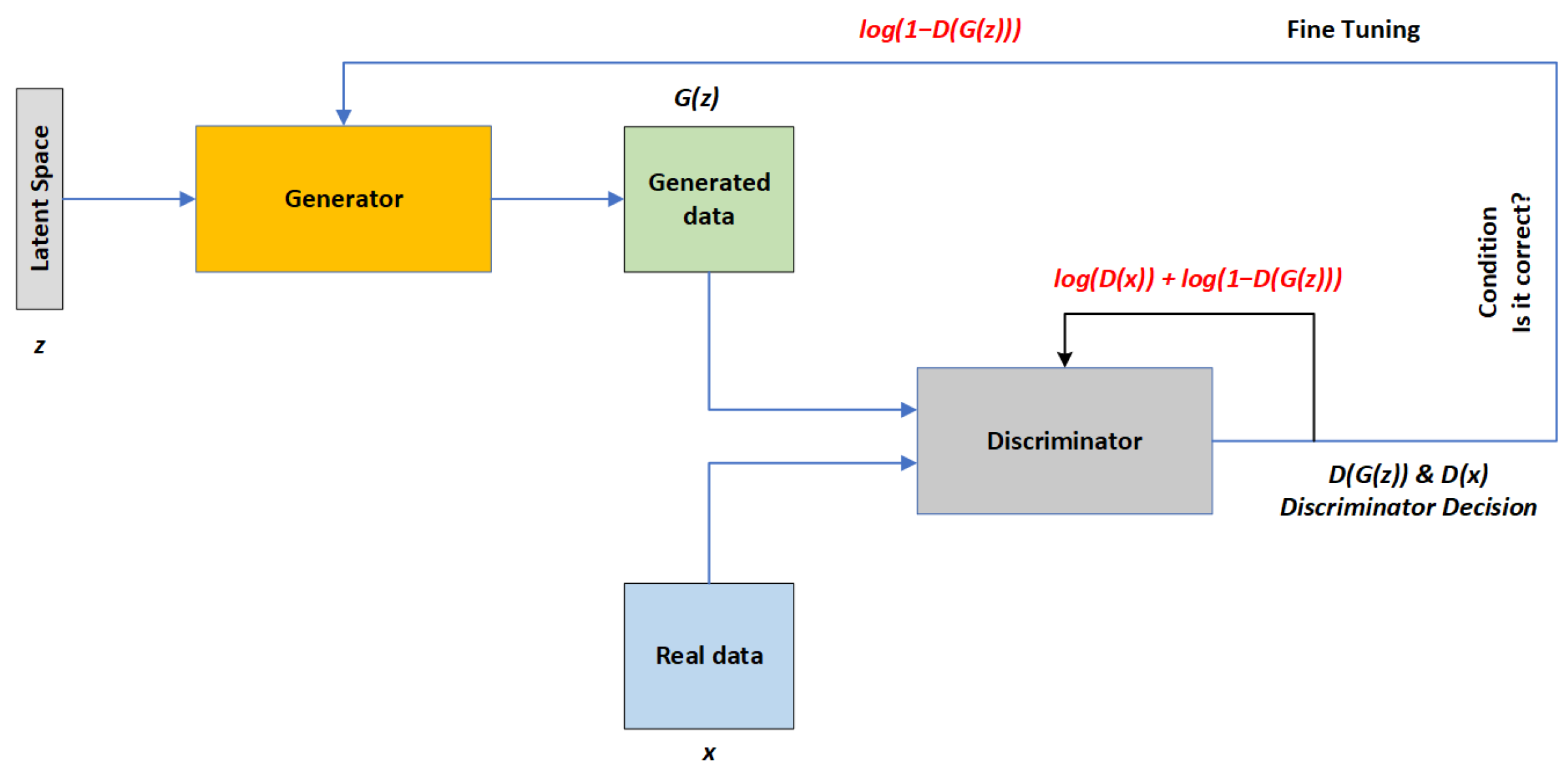

78].

The GAN model is trained iteratively by generator and a discriminator networks. The generator takes random sample data and generates a synthetic dataset, whereas the discriminator compares synthetically generated data with a real dataset based on set conditions [

79] as shown in

Figure 7. The generative model estimates the conditional probability

for a given target

y. Naive Bayes classifier models

and then transforms the probabilities into conditional probabilities

by applying the Bayes rule. GAN has been used for synthesizing deep fakes [

80]. To get an accurate value, Bayes’ theorem’s equation

5 is used.

where the posterior is the probability that the hypothesis

Y is true given the evidence

X. The prior probability is the probability that the hypothesis

Y is true before we see the evidence

X. The likelihood is the probability of the evidence

X given that the hypothesis

Y is true. The evidence is the data that we have observed.

6. Malicious Alerts Detection System (MADS)

This section presents the proposed AI predictive model for Malicious Alert Detection System (MADS). A predictive model goes through training, testing and feedback loops using ML techniques. The workflow for security problems consists of planning, data collection and preprocessing, model training and validation, event prediction, performance monitoring and feedback.

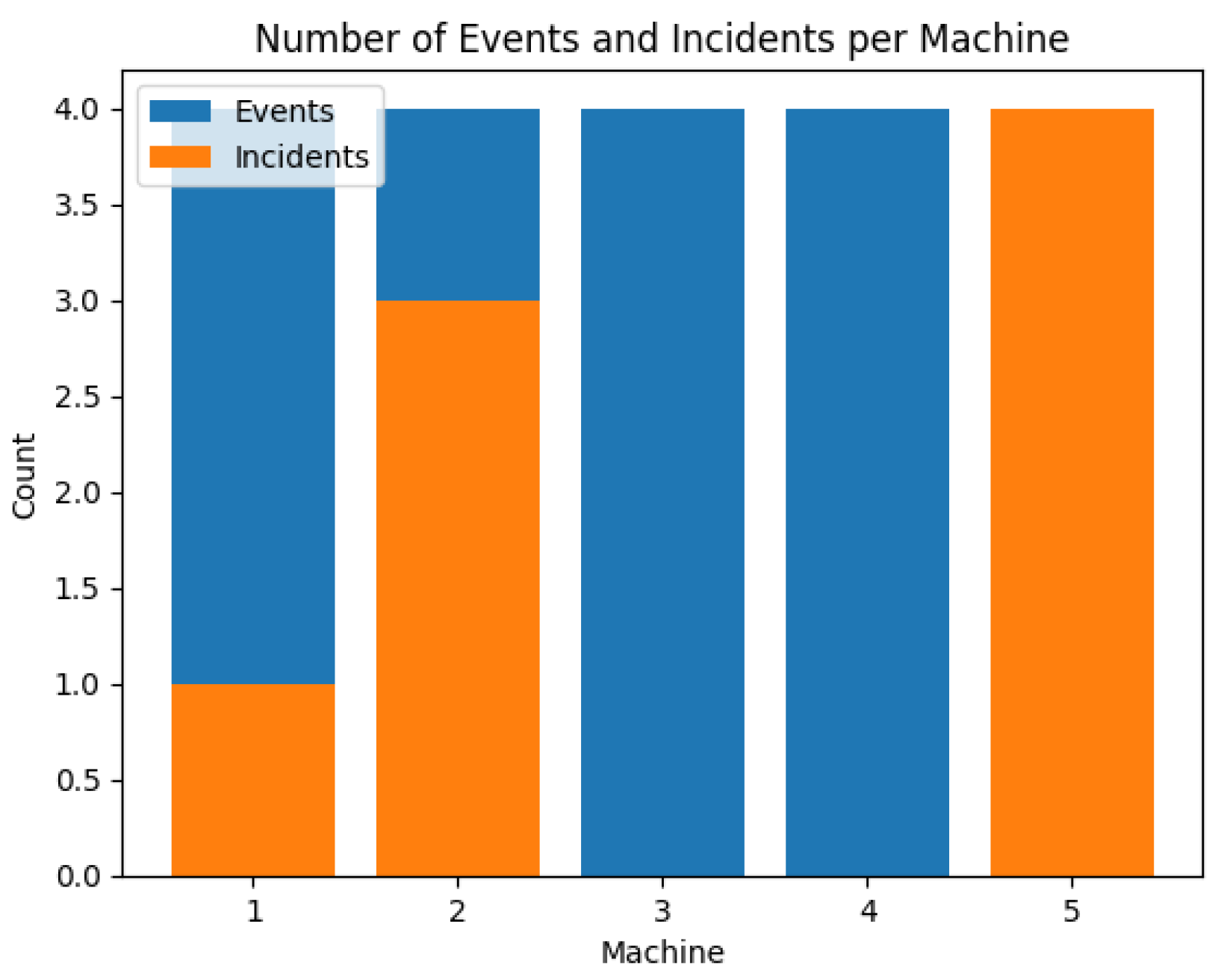

Detecting threats on a device depends on rules developed to detect anomalies in the data being collected and analysed. It requires understanding the data, keeping track of events, correlating and creating incidents on affected machines as shown in

Table 1 and

Figure 5, where machine (

m) represents the endpoint {

} and where (

e) is an event and (

S) is a stream of events {

} of an attack or possible multi-stage attack shown in

Table 2. All machines generate alerts, but not all turn into incidents or are TP, as shown in

Figure 8.

6.1. Multi Stage Attack

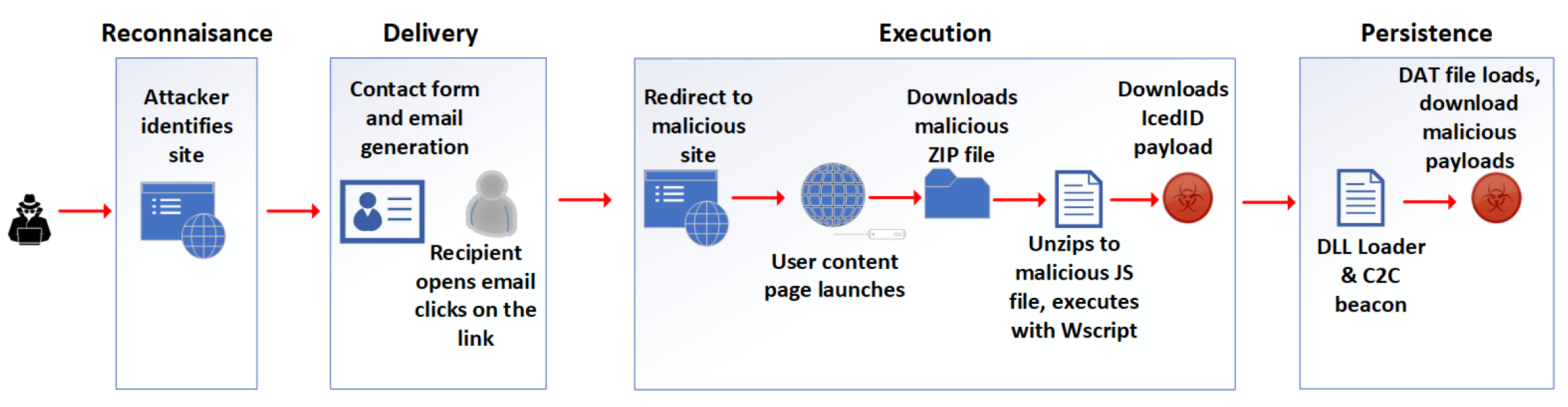

The multistage attack illustrated in

Figure 9 utilises a popular malware, legitimate infrastructure, URLs and emails to bypass detection and deliver IcedID malware to the victim’s machine [

81], in the following stages.

Stage 1: Reconnaissance, TA identifies a website with contact forms to use for the campaign. Delivery, TA uses automated techniques to fill in a web-based form with a query which sends a malicious email to the user, containing the attacker-generated message, instructing the user to download a form with a link to a website. The recipient receives an email sent from a trusted email marketing system, by clicking on the URL link.

Stage 2: Execution, downloads a malicious zip file, unzips to malicious JS file and executes via WS script. Downloads IceID payload and executes the payload.

Stage 3: Redirects to malicious, top-level domain. Google user content page launches. Downloads malicious ZIP file. Unzips a malicious JS file, and executes it via WS script. Downloads IceID payload and executes the payload.

Stage 4: Persistence, IcedID connects to a command-and-control server. Downloads modules and runs scheduled tasks, to capture and exfiltrate data. Downloads implants like Cobalt Strike for remote access. Collecting additional credentials, performing lateral movement and delivering secondary payloads.

Different machines might have similar events with the same TTPs but with different IOCs and could be facing multi-stage attacks with different patterns [

36]. There is no obvious pattern observed in which a certain event

would follow another event

given stream

. A predictive model is utilised to identify FPs, recognize multiple events with different contexts, correlate, and accurately predicts potential threat with attack story, detailed evidence, and remediation recommendation.

|

Algorithm 1: MADS Algorithm |

Require: Machine M, Event Stream S

- 1:

Output: Initialize AlertList = [], IncidentList = [], k-NN Parameter: k, IncidentThreshold, IncidentID = 1, MaliciousSamples = 0 - 2:

for each incoming event e in Event Stream S do

- 3:

AlertList.append(e) - 4:

if length(AlertList) k then

- 5:

maliciousSamples = detectMaliciousSamples(AlertList, k) - 6:

MaliciousSamples += maliciousSamples - 7:

if MaliciousSamples IncidentThreshold then

- 8:

incident = createIncident(AlertList, IncidentID) - 9:

IncidentList.append(incident) - 10:

IncidentID++ - 11:

MaliciousSamples = 0 - 12:

AlertList.clear() - 13:

else

- 14:

AlertList.removeFirstEvent() - 15:

end if

- 16:

end if

- 17:

end for - 18:

Output: IncidentList - 19:

Function: detectMaliciousSamples(alertList, k) - 20:

maliciousSamples = 0 - 21:

for i = 1 to length(alertList) do

- 22:

Di = k-NN(alertList[i], alertList) - 23:

vote = label_voting(Di) - 24:

confidence = vote_confidence(Di, vote) - 25:

if confidence > % and vote != alertList[i] then

- 26:

maliciousSamples++ - 27:

end if

- 28:

end for - 29:

return maliciousSamples - 30:

Function: createIncident(alertList, incidentID)

|

6.2. Detection Algorithm

The security event prediction problem is formalized as security event at timestamp y, where S is the set of all events. A security event sequence observed on an endpoint is a sequence of events observed at a certain time. The detection of security alerts and the creation of incidents are based on the provided event streams and algorithm parameters. Algorithm 1 takes machine (M) and stream (S) consisting of multiple events as input. It uses AlertList to store detected security alerts and IncidentList for created security incidents. The algorithm uses k-NN parameter (k) to determine the number of nearest neighbours to consider and a threshold value to determine when to create a security incident. The is used to assign unique IDs to created incidents and () to keep track of the number of detected malicious samples.

It iterates over each incoming event (e) in stream (S) and appends the event (e) to the AlertList. Checks if the length of the AlertList is equal to or greater than k (the number of events needed for k-NN). Uses detectMaliciousSamples function to identify potential malicious samples in the AlertList using k-NN, and gets the count of malicious samples. Increments the MaliciousSamples counter by the count of detected malicious samples and checks if they exceeded the IncidentThreshold. If the threshold is reached, it calls the createIncident function to create an incident object using the alerts in the AlertList and the IncidentID. Appends the incident object to the IncidentList. Increments the IncidentID for the next incident, resets the MaliciousSamples counter to 0 and clears the AlertList. But if the threshold is not reached, it removes the first event from the AlertList to maintain a sliding window and continues to the next event. It also gives output of the IncidentList containing the created security incidents.

For each alert in the AlertList, the k-NN is calculated using the k-NN algorithm. It performs label voting to determine the most frequent label (vote) among the neighbours. It calculates the confidence of the vote (confidence). If the confidence is greater than 0.60 and the vote is not the same as the original alert, it counts it as a potentially malicious and returns the count of malicious samples. The incident object includes incident ID, alerts timestamps, severity,and affected machines.

The event to be predicted is defined as the next event and each is associated with already observed events . The problem to solve is to learn a sequence prediction based on (S) and predicting for a given machine . A predictive system should be capable of understanding the context and making predictions given the (S) sequence in the algorithm and model output.

6.3. Evaluation of the MADS Model

These are some of the evaluation techniques used when solving ML problems for cyber security [

6,

15,

78,

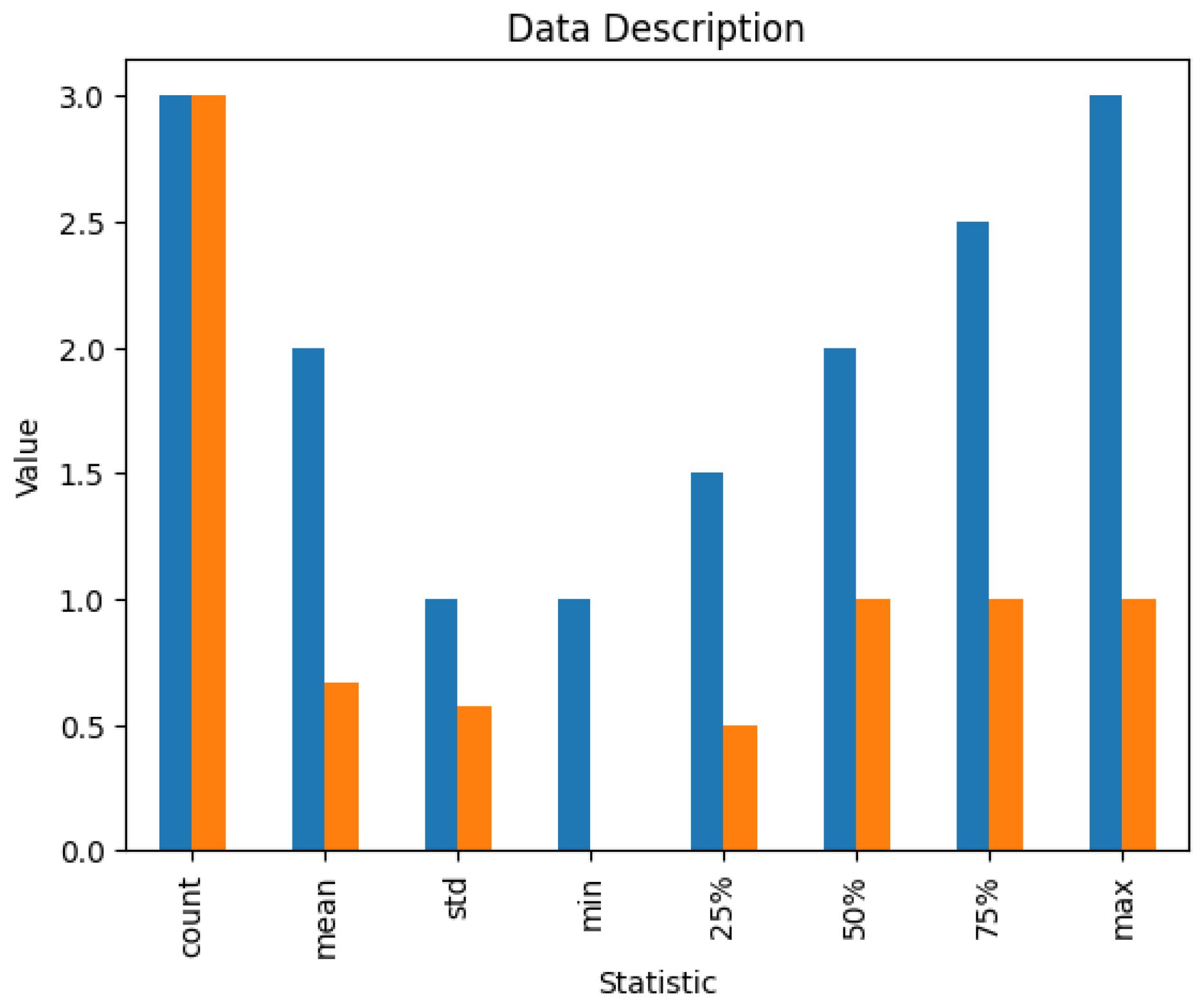

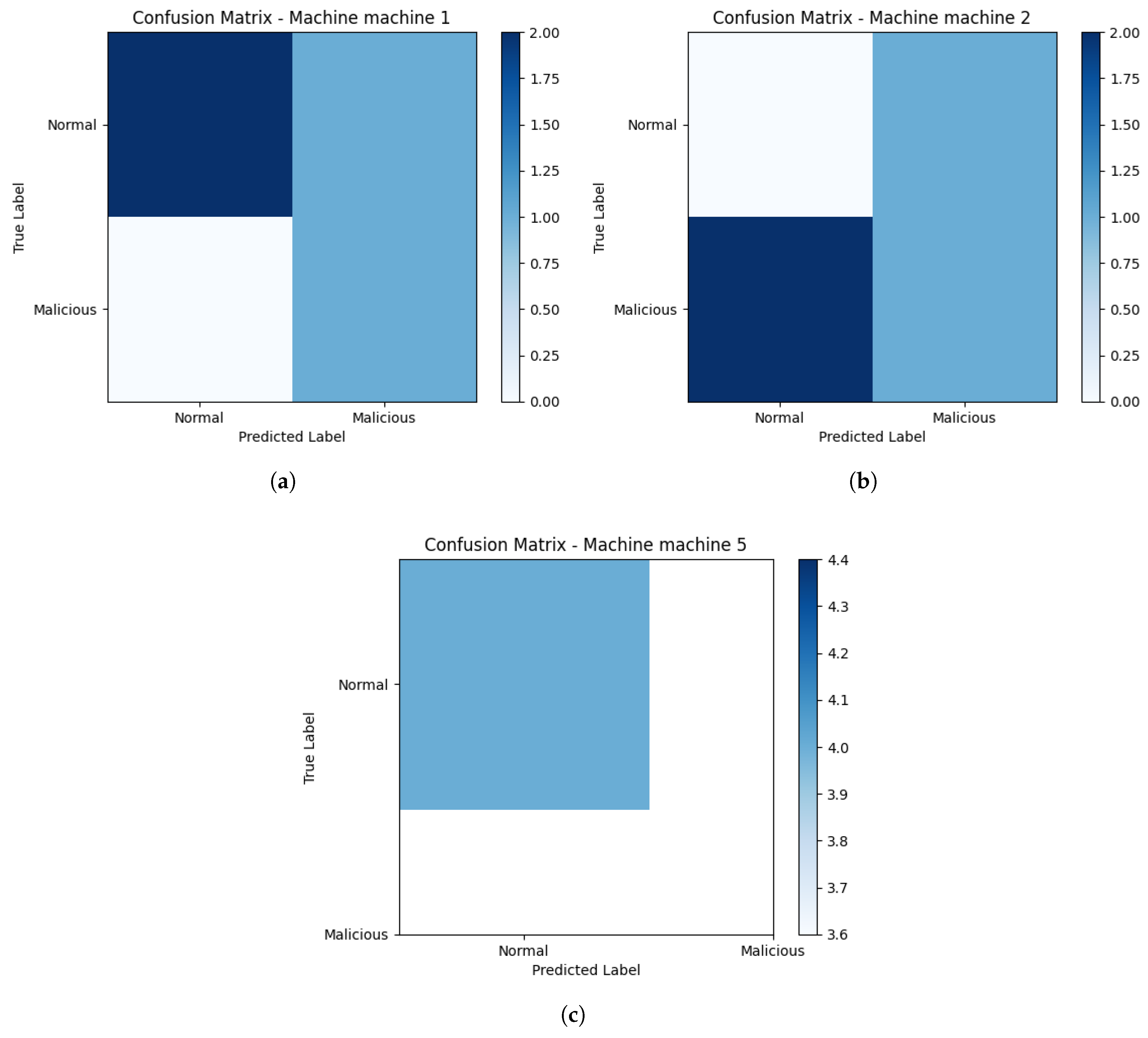

82]. Some machines are excluded because their actual malicious labels had one class or no incidents were created based on the data frame in

Figure 10. For the classification problem, the model is evaluated on TP, True Negative (TN), FP (Type I error) and FN (Type II error) and the elements of the confusion matrix, with

matrix, where

N is the total number of target classes. They are used for accuracy, precision, recall and

. The accuracy is the proportion of the total number of predictions that are considered accurate and determined with equation

6 shown in

Figure 11.

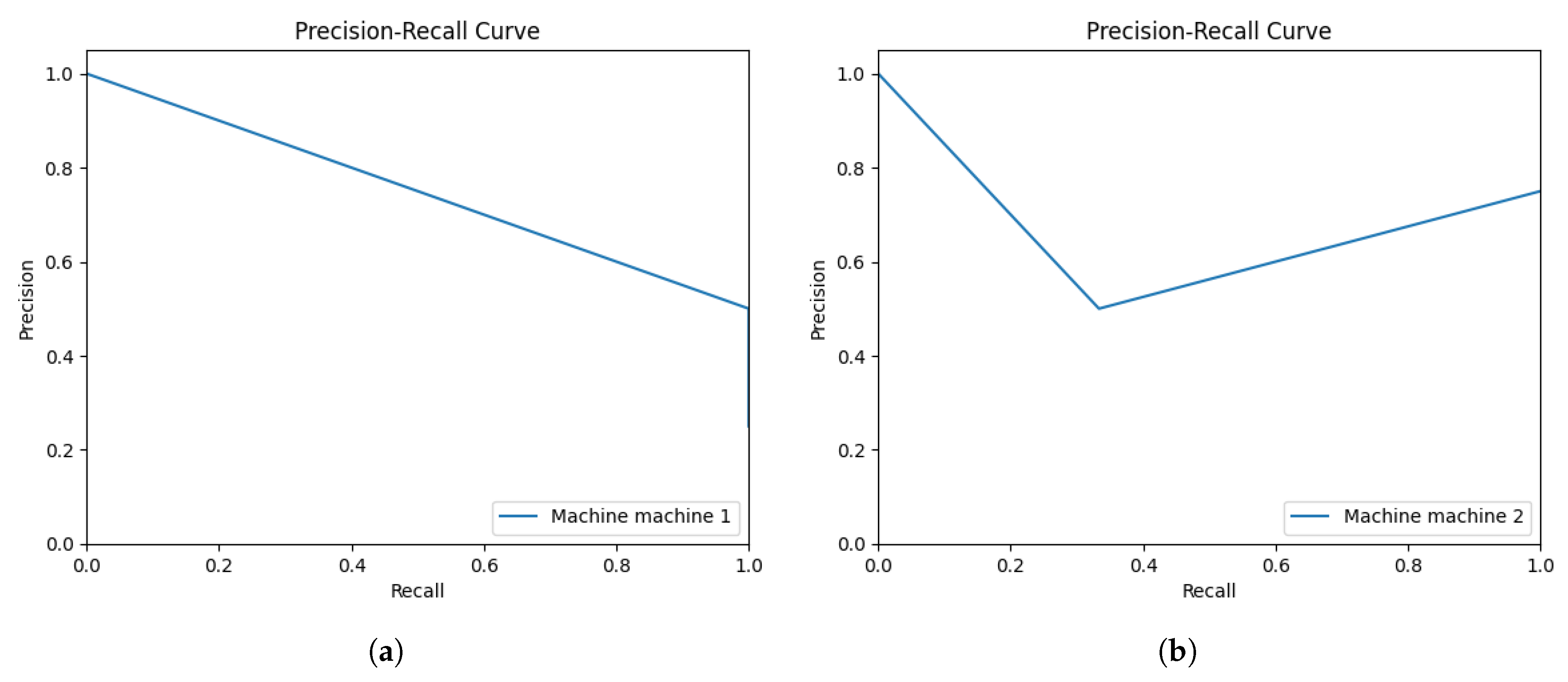

The recall is the proportion of the total number of TP, where FN are higher than FP and calculated with equation

7. Precision is the proportion of the predicted TP that was determined as correct if the concern is FP using equation

8 both shown in

Figure 12.

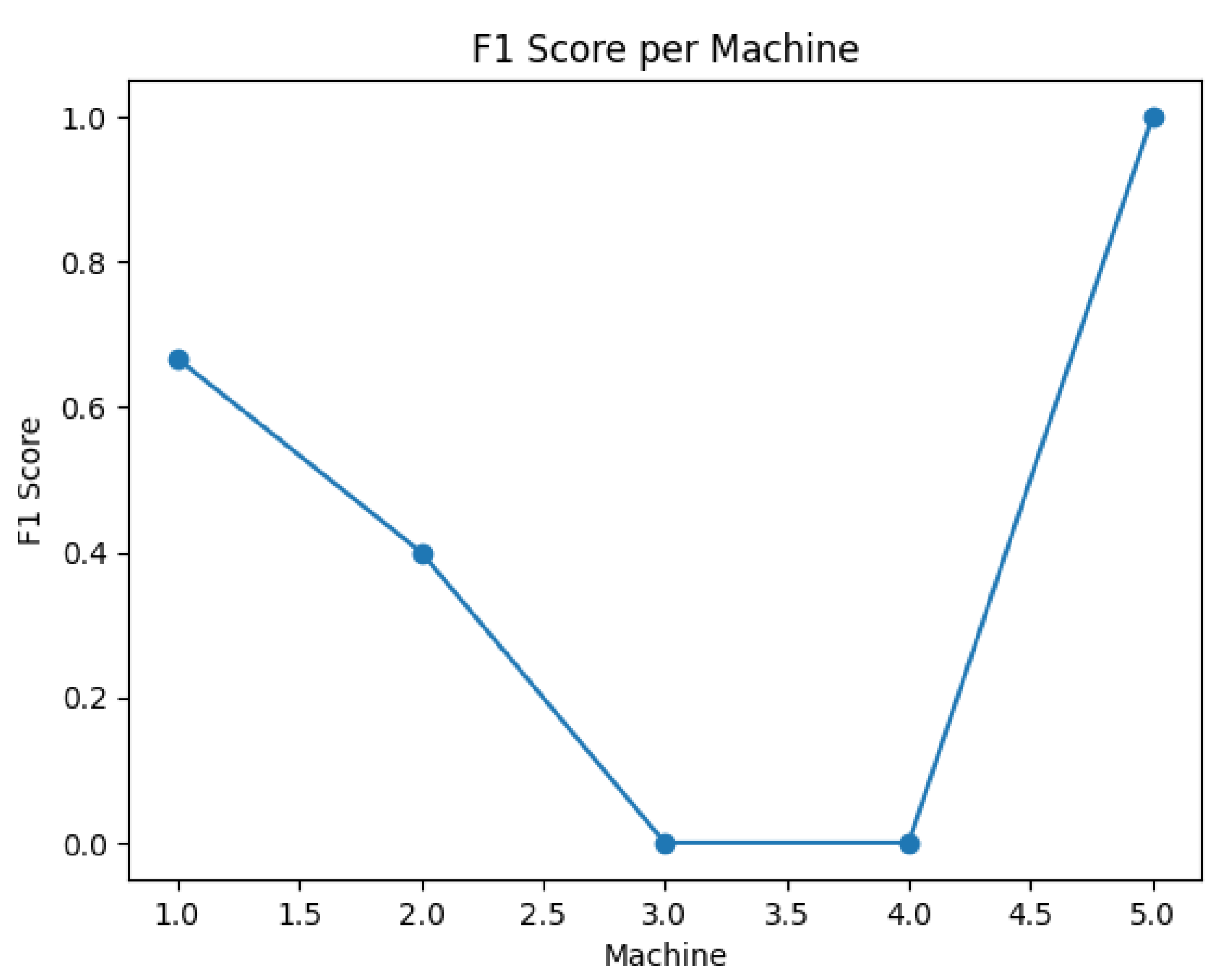

In cases where precision or recall needs to be adjusted, F-measure of F1 – Score (F) is used as a harmonic mean of precision and recall with equation

9, iteration of dataset epochs are shown in

Figure 13.

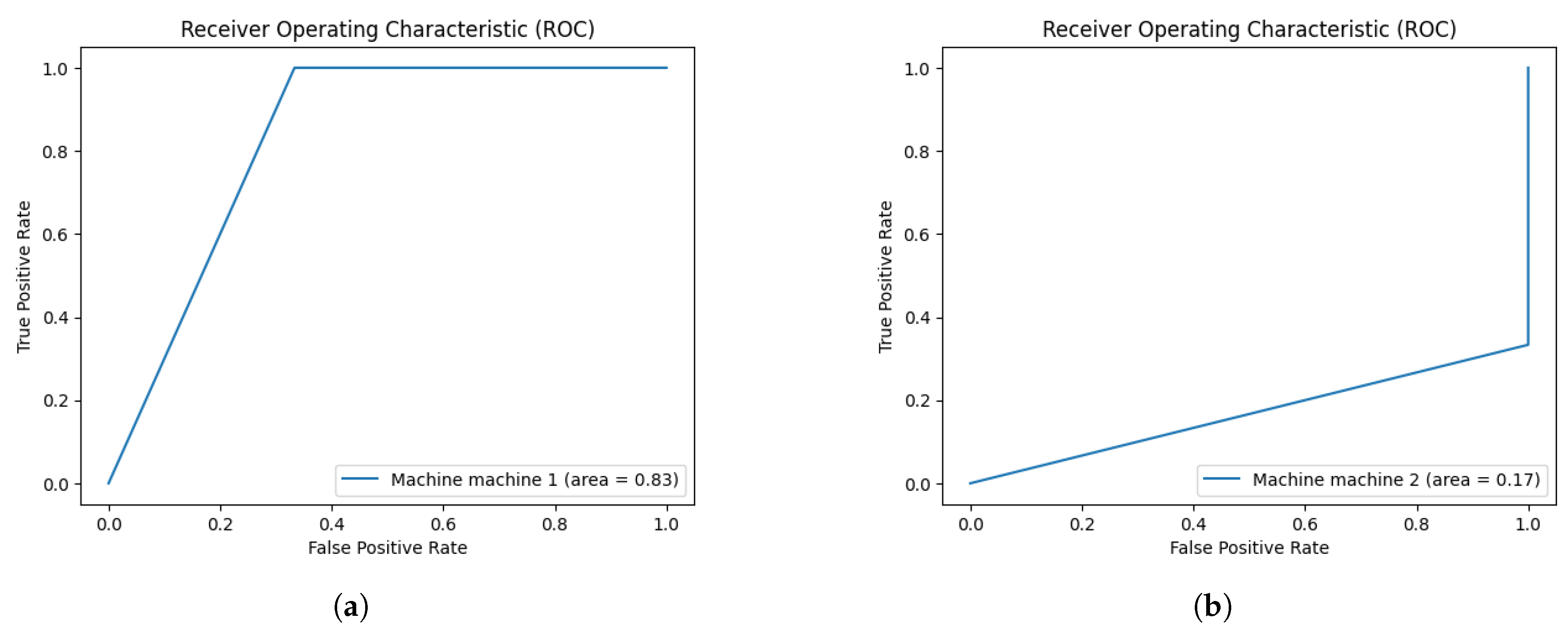

A receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) curve shows the diagnostic ability of the model as its discrimination threshold is varied using TP Rate (TPR) and FP Rate (FPR) shown in

Figure 14 using Formulas

10 and

11.

In clustering, Mutual Information is a measure of similarity between two labels of the same data. Where

is the number of samples in cluster

and

is the number of samples in cluster

. To measure loss in regression, Mean Absolute Error (MAE) can be used to determine the sum of the absolute mean and Mean Squared Error (MSE) to determine the mean or normal difference to provide a gross idea of the magnitude of the error with the equation. While Entropy determines the measure of uncertainty about the source of data. Where

a = Proportion of positive examples and

b = Proportion of negative examples. For GAN, to capture the difference between two distributions in loss functions, the Minimax loss function [

79] and Wasserstein loss function [

82] are used.

7. Risk and Limitation of Artificial Intelligence

The utilisation of AI is picking up momentum, however, there is still a lack of responsible AI frameworks and regulations to enforce security, privacy and ethical practices. Therefore, the existing methods need to be evaluated, and new strategies and standards developed [

83]. For ML, high-quality data is required for training, but due to high costs, existing data and pre-trained models are often obtained from external sources, exposing AI systems to new security risks [

84]. An AI system may produce false results if malicious training data is inserted through a backdoor attack. Mislabelling data might lead to miss-classification like wrongly tagging stop signs in autonomous driving systems [

5,

19] and quarantining files in attack detection. Recently, Zoom URLs were mislabelled as malicious by Microsoft’s EDR, leading to a huge volume of FP alerts, resource wastage and meetings cancellations.

The impact of AI on cyber security is both positive and negative. Mishandling of AI can lead to negative social impact and system compromise. There are also issues of inherent weaknesses in the ML algorithms and their dependencies, poor deployment and maintenance, abuse, espionage and bias.

7.1. Limitations and Poor Implementation

AI comes with limitations and dependencies, if implemented poorly, security teams may end up making poor decisions. ML is probabilistic, DL algorithms do not have domain knowledge or understand network topologies or business logic [

85]. Models may produce results that violate the fundamental constraints of the organisation environment, hence, constraints should be added to algorithms to align with the rules and logic. The AI model is unable to intuitively explain the rationale behind its decision on pattern finding or anomaly detection [

7]. Explainable AI (XAI) techniques can be applied to describe an AI model, its decisions, expected impact and potential biases [

86]. This defines model correctness, fairness, transparency, and results in decision-making. XAI is crucial in building trust and confidence during AI deployment.

There is always a degree of error associated with the probability such as FP and FN errors, bias-variance and auto correlation [

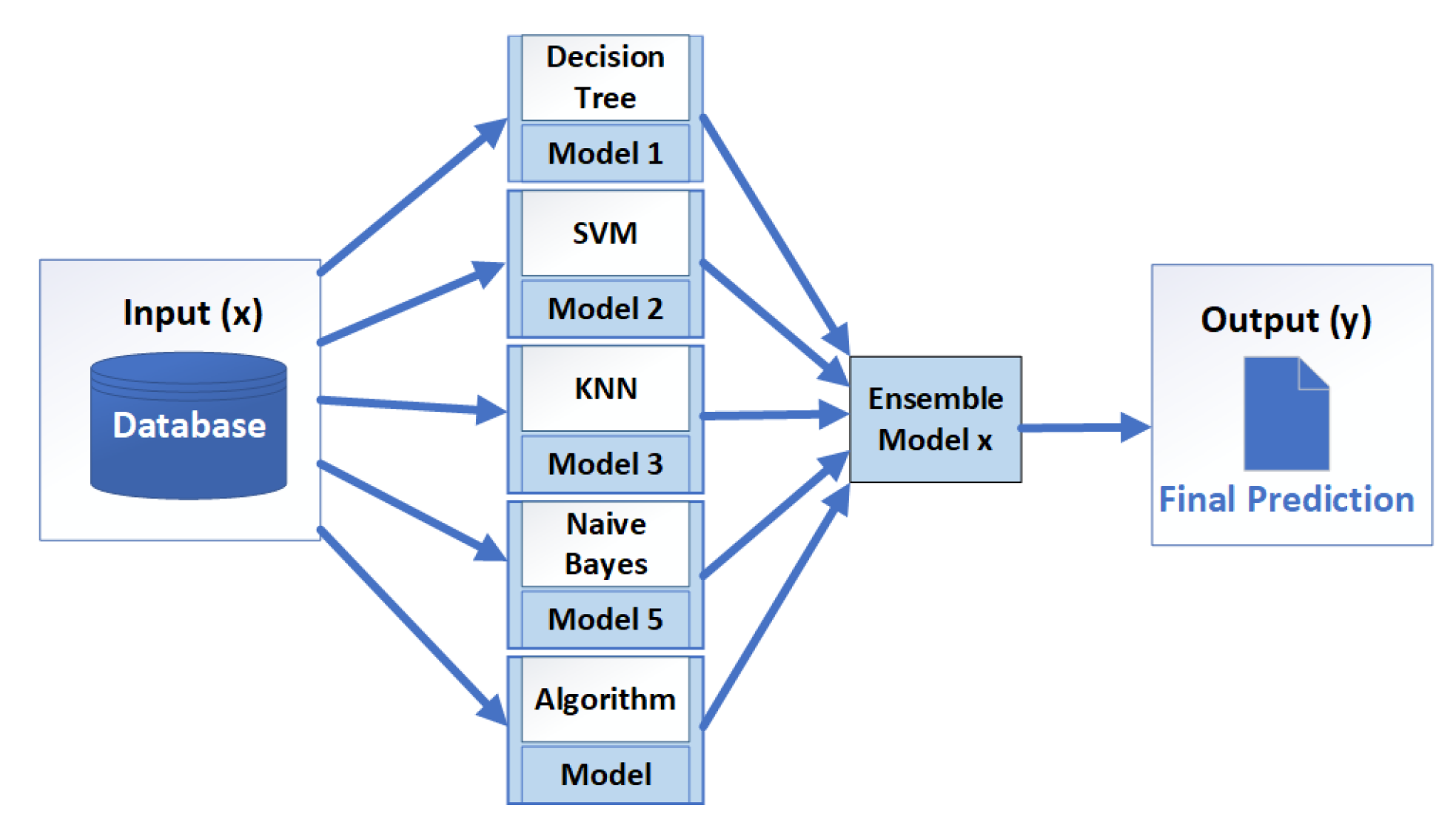

87]. ML has a dependency on large datasets and labelled data, in cases where the train data is not enough, the following methods can be adopted:

Model Complexity: Build a simple model with fewer parameters, less susceptible to over-fitting algorithms. Using Ensemble learning to combine several learners to improve prediction [

88], as shown in

Figure 15.

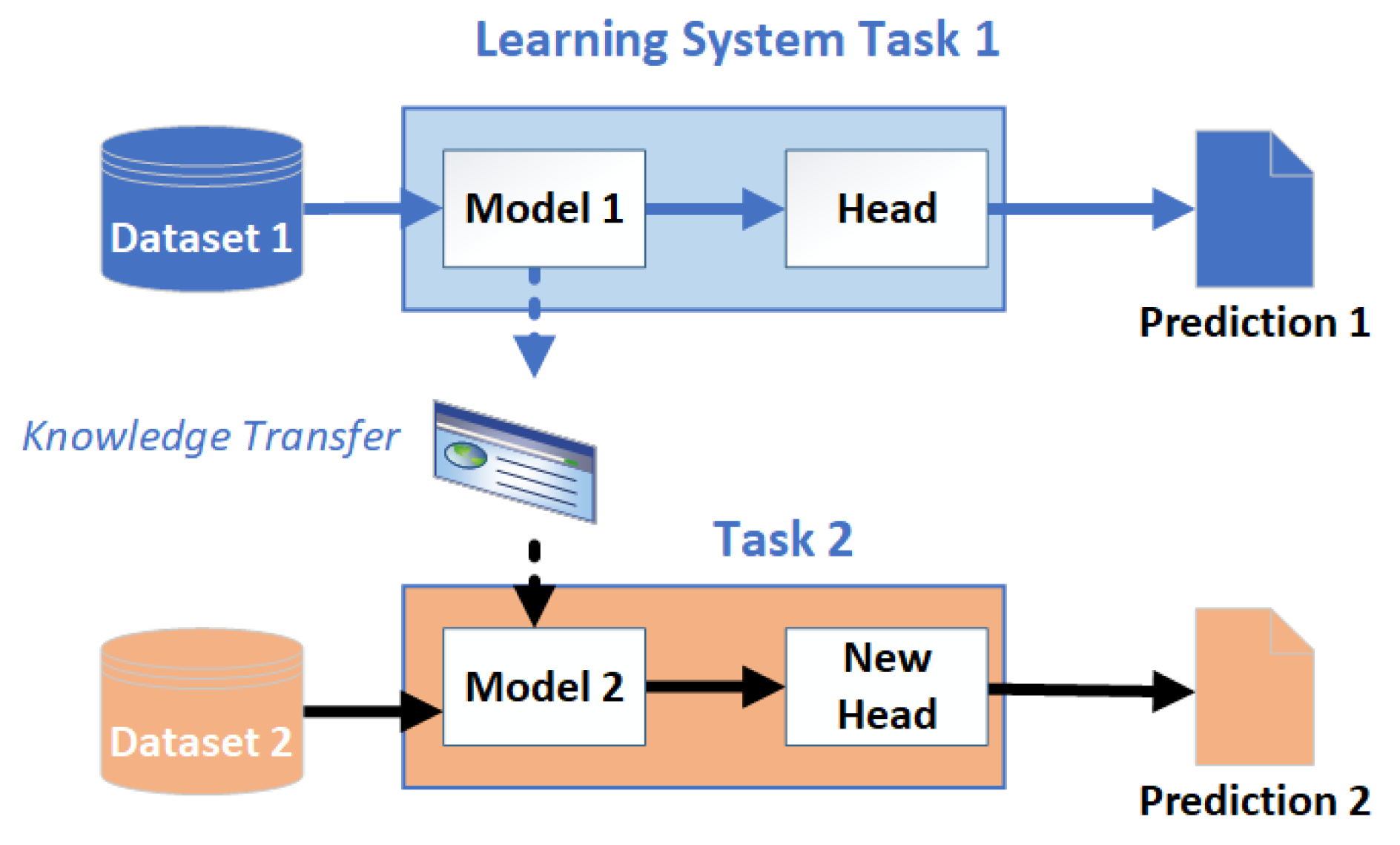

Transfer Learning: Use a pre-built model fine-tuned on small datasets, as shown in

Figure 16. It reuses a trained NN and model weights to solve similar problems [

89].

Data Augmentation: Make slight improvements to get new images with pre-existing samples and increase the number of training samples with scaling, rotation, and affine transforms [

90].

Synthetic Data: Artificially generate samples which mimic the real-world data, when you have a good understanding of the features, but it may induce bias in existing data [

76].

7.2. Attacks against Artificial Intelligence

The creation of an AI has led to new attack surface, exploitation and abuse [

5,

6,

23,

29,

33,

91]. There are also new top 10 most critical vulnerabilities for Large Language Mode (LLM) [

92]. AI is still susceptible to traditional attacks such as buffer overflow, and DoS. Some of AI attacks include:

Adversarial attack: The attacker manipulates input data to fool an AI system into producing incorrect results, by adding noise to an image or object to make it unrecognizable.

Evasion attack: The attacker exploits AI vulnerabilities to evade detection, by modifying a malware file to evade antivirus software.

Poisoning attack: The attacker introduces malicious data into an AI system to corrupt its training or compromise its accuracy. By injecting fake data into a dataset used for training a model to bias it towards making incorrect predictions. An attacker can also insert false data into a training set for a spam filter to cause it to misclassify emails as spam.

Model stealing attack: It involves stealing a trained model to replicate it, extracting a model’s parameters or training data through reverse engineering.

Model inversion attack: It involves extracting sensitive information from an AI system by inverting its trained model to reconstruct a patient’s medical history from a hospital’s system.

Backdoor attack: An attacker adds a hidden trigger to an AI system that can be activated to cause it to behave maliciously. The model might be trained to recognize a pattern input, such as a specific phrase or image, and then program it to perform a specific action when that input is detected.

DoS attack: The attacker sends numerous inputs to cause an AI system to crash or malfunction, such as flooding a chatbot with requests, exceeding its computational and memory resource, and rendering it unavailable for legitimate users.

These attacks are performed against CIA of the AI system during training, testing and in production. The attack against confidentiality aims to uncover the details of the algorithms [

93]. An attack can be initiate by inferring the model’s training attributes, the data and algorithms [

94]. Attack on integrity is aimed at altering the trustworthiness of AI’s capability [

95]. An attack can change the behaviour of the model in classifying the malicious and genuine users such that it fails to classify the users correctly. To amend this change, the model has to be retrained with clean and trustworthy data. An attack on the availability makes the targeted model useless and unavailable. The TA can take control of the model and make it perform a completely different task than it was designed to for, using adversarial reprogramming or induce response action such as temporary shut-down and model recalibration [

96].

7.2.1. Misuse

AI is empowering different industries by enhancing their capability, however, cybercriminals are also utilising AI to carry out attacks with greater speed, scope and stealth than ever before. TAs are bypassing control and utilising the data and API offered by genuine tools to test undetectable malware using ML [

97]. ML enables attackers to be extremely precise and launch an attack where there is the highest likelihood of success, such as identifying and targeting users through online and offline footprints. The TAs are operationalising AI models to automatically build and send targeted phishing emails with specific context unique to each recipient, using genuine cloud vendor platforms. They are utilising generative AI to write text messages, phishing emails and social media posts that can pass filtering tools or convince users.

Attackers’ tasks are now performed by AI models, running autonomously and making highly intelligent decisions [

98]. They can also generate synthetic data to impersonate a person or create false information. A criminal recently impersonated an executive of an energy company, by using a synthetic voice, then persuaded an employee to transfer about a quarter of a million dollars to a fraudulent account [

99].

7.2.2. Limitations

There are some limitations, it requires a lot of time and money on resources like computing power, memory, and data to build and maintain AI systems. Different datasets of malicious codes and anomalies are required. Some organisations just don’t have the resources and time to obtain all the accurate datasets [

12]. Attackers are learning from AI tools to develop more advanced attacks. They are utilising neural fuzzing to leverage AI to quickly test large amounts of random inputs [

100], and learning about the weaknesses of systems by gathering information with the power of NNs.

7.3. Deployment

The limited knowledge of AI has led to deployment problems, leaving organisations more vulnerable to threats. Certain guiding principles should be applied while deploying AI to ensure support, security and capabilities availability [

101]. This improves the effectiveness, efficiency, and competitiveness, it should go through a responsible AI framework and planning process together with the current organisational framework to set realistic expectations for AI projects. Some of the guiding principles are as follows [

102]:

Competency: An organisation must have the willingness, resources, and skill set to build home-grown custom AI applications or a vendor with proven experience in implementing AI-based solutions must be used.

Data readiness: AI models rely on the quantity and quality of data. But it might be in multiple formats, different places or managed by different custodians. Therefore, the use of the data inventory, to assess the difficulty of availability, ingesting, cleaning, and harmonizing the data is required.

Experimentation: Implementation is complex and challenging, it requires adoption, fine-tuning and maintenance even with already-built solutions. Experimenting is expected using use cases, learning, and iterating until a successful model is developed and deployed.

Measurement: An AI system has to be evaluated for its performance and security using a measurement framework. Collect Data must be collected to measure performance, confidence and for metrics.

Feedback loops: Systems are retrained and evaluated with new data. It is best practice to plan and build a feedback loop cycle for the model to relearn, and fine-tune it to improve accuracy and efficiency. Workflow should be developed and data pipelines automated to constantly get feedback on how the AI system is performing using RL [

66].

Education: Educating the team on technology’s operability is instrumental in having a successful AI deployment and it will improve efficiency and confidence. The use of AI can help the team grow, develop new skills and accelerate productivity.

7.4. Product Evaluation

Evaluation is fundamental when acquiring or developing an AI system. Different products are being advertised as AI-enabled with capabilities to detect and prevent attacks, automate tasks, and predict patterns. However, these claims have to be evaluated and identified for scoping and tailoring purposes to fit the organisation’s objectives [

103]. It is vital to validate processes for model training, applicability, integration, proof of concept, acquisition, support model, reputation, affordability, and security to support practical and reasoned decisions [

104].

The documentation of the product’s trained models process, data, duration, accountability, and measures for labelled data unavailability should be provided. It should state if the model has other capabilities, the source of training data, who will be training the model and managing feedback loops, and a time frame from installation to actionable insights should be provided. A good demonstration of an AI product does not guarantee a successful integration in the environment, a proof of concept should be developed with enterprise data and in its environment. Any anticipated challenges should be acknowledged, and supported. A measurement framework should be developed to get meaningful metrics in the ML pipeline. An automated workflow should be developed to orchestrate the testing and deploying of models using a standardised process.

It is important to understand whether AI capabilities were in built or acquired, add-on module or part of the underlying product and the level of integration. The security capabilities and features of the product must be evaluated, including data privacy preservation. There should be a clear agreement on the ownership of the data to align with privacy compliance and evaluate vendors’ approach and measures to protect AI system.

8. Conclusion

The fields of AI and cyber security are evolving rapidly and can be utilised symbiotically to improve global security. Leveraging AI can yield benefits in defensive security, but also empower TAs. This paper discussed the discipline of AI, security objectives and applicability of AI in the field of cyber security. It presented use cases of ML to solve specific problems and developed a predictive MADS model to demonstrate an AI-enabled detection approach. With proper consideration and preparation, AI can be beneficial to organisations in enhancing security, increasing efficiency and productivity. Overall, AI can improve security operations, vulnerability management, and security posture, accelerate detection and response, and reduce duplication of processes and human fatigue. However, it can also increase vulnerabilities, attacks, violation of privacy and bias. AI can also be utilised by TAs to initiate sophisticated and stealth attacks. The paper recommended best practices, deployment operation principles and evaluation processes to enable visibility, explainability, attack surface reduction and responsible AI. Future work will focus on improving the MADS, developing models other use cases and developing a responsible AI evaluation framework for better accountability, transparency, fairness and interpretability.

.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K.K.E.; methodology, E.K.K.E.; validation, E.K.K.E.; formal analysis, E.K.K.E; investigation, E.K.K.E.; writing—original draft preparation, E.K.K.E.; writing—review and editing, E.K.K.E.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zeadally, S.; Adi, E.; Baig, Z.; Khan, I.A. Harnessing artificial intelligence capabilities to improve cybersecurity. Ieee Access 2020, 8, 23817–23837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secuirty, I. The Cost of a Data Breach Report 2022, 2022.

- Finance, Y. Artificial Intelligence (AI) In Cybersecurity Market Size USD 102.78 BN by 2032, 2023.

- Arp, D.; Quiring, E.; Pendlebury, F.; Warnecke, A.; Pierazzi, F.; Wressnegger, C.; Cavallaro, L.; Rieck, K. Dos and don’ts of machine learning in computer security. In Proceedings of the 31st USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 22); 2022; pp. 3971–3988. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R.; Yampolskiy, R. Understanding and Avoiding AI Failures: A Practical Guide. Philosophies 2021, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.C.; Diep, Q.B.; Zelinka, I. Artificial Intelligence in the Cyber Domain: Offense and Defense. Symmetry 2020, 12, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardatos, P.; Papastefanopoulos, V.; Kotsiantis, S. Explainable AI: A Review of Machine Learning Interpretability Methods. Entropy 2021, 23, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panesar, A. Machine Learning and AI for Healthcare: Big Data for Improved Health Outcomes; Apress: Berkeley, CA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuli, S.; Xu, M.; Singh, I.; Singh, K.V.; Lindsay, D.; Tuli, S.; Smirnova, D.; Singh, M.; Jain, U.; et al. Transformative effects of IoT, Blockchain and Artificial Intelligence on cloud computing: Evolution, vision, trends and open challenges. Internet of Things 2019, 8, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishant, R.; Kennedy, M.; Corbett, J. Artificial intelligence for sustainability: Challenges, opportunities, and a research agenda. International Journal of Information Management 2020, 53, 102104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirkuttis, N.; Klein, H. Artificial intelligence in cybersecurity. Cyber, Intelligence, and Security 2017, 1, 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ghillani, D. Deep Learning and Artificial Intelligence Framework to Improve the Cyber Security. Authorea Preprints Publisher: Authorea. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tyugu, E. Artificial Intelligence in Cyber Defense. 2011 3rd International Conference on Cyber Conflict 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Abusnaina, A.; Khormali, A.; Alasmary, H.; Park, J.; Anwar, A.; Mohaisen, A. Adversarial learning attacks on graph-based IoT malware detection systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 39th international conference on distributed computing systems (ICDCS). IEEE; 2019; pp. 1296–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Liu, J.; Xiang, Y.; Niu, W.; Tong, E.; Han, Z. Adversarial attack and defense in reinforcement learning-from AI security view. Cybersecurity 2019, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, Y.; Huo, S.; Hu, H.; Sun, P. Defensive deception framework against reconnaissance attacks in the cloud with deep reinforcement learning. Science China Information Sciences 2022, 65, 170305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Fossaceca, J.M.; Bennett, K.W. A cloud-based computing framework for artificial intelligence innovation in support of multidomain operations. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 2021, 69, 3913–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollini, A.; Callari, T.C.; Tedeschi, A.; Ruscio, D.; Save, L.; Chiarugi, F.; Guerri, D. Leveraging human factors in cybersecurity: an integrated methodological approach. Cognition, Technology & Work 2022, 24, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, B.J. The Turing Test*. Minds and Machines 2000, 10, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnad, S. The Turing Test is not a trick: Turing indistinguishability is a scientific criterion, 1992.

- Kaplan, A.; Haenlein, M. Siri, Siri, in my hand: Who’s the fairest in the land? On the interpretations, illustrations, and implications of artificial intelligence. Business Horizons 2019, 62, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, R.; Paxson, V. Outside the closed world: On using machine learning for network intrusion detection. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE symposium on security and privacy. IEEE; 2010; pp. 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Apruzzese, G.; Andreolini, M.; Ferretti, L.; Marchetti, M.; Colajanni, M. Modeling Realistic Adversarial Attacks against Network Intrusion Detection Systems. Digital Threats 2022, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, V.; Golightly, L.; Modesti, P.; Xu, Q.A.; Doan, L.M.T.; Hall, K.; Boddu, S.; Kobusińska, A. A Survey on Intrusion Detection Systems for Fog and Cloud Computing. Future Internet 2022, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, N.; Koroniotis, N.; Keshk, M.; Zomaya, A.Y.; Tari, Z. Explainable Intrusion Detection for Cyber Defences in the Internet of Things: Opportunities and Solutions. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2023, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B.B.; Tayal, S.P.; Gupta, M. Software engineering and testing; Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2010.

- Stuttard, D.; Pinto, M. The web application hacker’s handbook: Finding and exploiting security flaws; John Wiley & Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- John, M.M.; Olsson, H.H.; Bosch, J. Towards mlops: A framework and maturity model. In Proceedings of the 2021 47th Euromicro Conference on Software Engineering and Advanced Applications (SEAA). IEEE; 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, I.H.; Furhad, M.H.; Nowrozy, R. Ai-driven cybersecurity: an overview, security intelligence modeling and research directions. SN Computer Science 2021, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathas, C.M.; Vassilakis, C.; Kolokotronis, N.; Zarakovitis, C.C.; Kourtis, M.A. On the design of IoT security: Analysis of software vulnerabilities for smart grids. Energies 2021, 14, 2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, M.; Almuairfi, S. Essential Activities for Secure Software Development. Int. J. Softw. Eng. Appl 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edris, E.K.K.; Aiash, M.; Loo, J. An Introduction of a Modular Framework for Securing 5G Networks and Beyond. Network 2022, 2, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotenko, I.; Saenko, I.; Lauta, O.; Vasiliev, N.; Kribel, K. Attacks Against Artificial Intelligence Systems: Classification, The Threat Model and the Approach to Protection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Sixth International Scientific Conference “Intelligent Information Technologies for Industry”(IITI’22).; Springer, 2022; pp. 293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Dunsin, D.; Ghanem, M.; Ouazzane, K. The use of artificial intelligence in digital forensics and incident response (DFIR) in a constrained environment 2022.

- Nist. Cybersecurity Framework CSF. NIST 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, R.; Ashley, T.; Castleberry, J.; Mckenzie, P.; Gupta Gourisetti, S.N. Cyber Threat Dictionary Using MITRE ATT&CK Matrix and NIST Cybersecurity Framework Mapping. In Proceedings of the 2020 Resilience Week (RWS); 2020; pp. 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crumpler, W.; Lewis, J.A. The cybersecurity workforce gap; JSTOR, 2019.

- Alshaikh, M. Developing cybersecurity culture to influence employee behavior: A practice perspective. Computers & Security 2020, 98, 102003. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, W.; Legrand, E.; Åberg, O.; Lagerström, R. Cyber security threat modeling based on the MITRE Enterprise ATT&CK Matrix. Software and Systems Modeling 2022, 21, 157–177. [Google Scholar]

- Danquah, P. Security Operations Center: A Framework for Automated Triage, Containment and Escalation. Journal of Information Security 2020, 11, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlette, D.; Caselli, M.; Pernul, G. A comparative study on cyber threat intelligence: the security incident response perspective. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2021, 23, 2525–2556. [Google Scholar]

- Cichonski, P.; Millar, T.; Grance, T.; Scarfone, K. Computer Security Incident Handling Guide. Technical Report NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-61 Rev. 2, National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Preuveneers, D.; Joosen, W. Sharing machine learning models as indicators of compromise for cyber threat intelligence. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 2021, 1, 140–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, H.; Maynard, S.B.; Desouza, K.C. Demystifying analytical information processing capability: The case of cybersecurity incident response. Decision Support Systems 2021, 143, 113476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salitin, M.A.; Zolait, A.H. The role of User Entity Behavior Analytics to detect network attacks in real time. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Innovation and Intelligence for Informatics, Computing, and Technologies (3ICT); IEEE, 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Khatri, S.K.; Diván, M.J. Optimization of power consumption in data centers using machine learning based approaches: a review. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering 2022, 12, 3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, J. Intrusion and intrusion detection. International Journal of Information Security 2001, 1, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassais, R.; Ezzati-Jivan, N.; Fernandez, J.M.; Aloise, D.; Dagenais, M.R. Multi-level host-based intrusion detection system for Internet of things. Journal of Cloud Computing 2020, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, N.; Hayes, E.; Bertino, E.; Ojo, P.; Choo, K.K.R.; Burnap, P. Impact and key challenges of insider threats on organizations and critical businesses. Electronics 2020, 9, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Traore, I.; Saad, S.; Mamun, M. Automated detection of unstructured context-dependent sensitive information using deep learning. Internet of Things 2021, 16, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, E.G.; Goyal, S.J. Survey on Data Leakage Prevention through Machine Learning Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Mobile and Embedded Technology Conference (MECON). IEEE; 2022; pp. 121–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ghouse, M.; Nene, M.J.; Vembuselvi, C. Data leakage prevention for data in transit using artificial intelligence and encryption techniques. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication and Control (ICAC3). IEEE; 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, M.H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Cento, G.; Jerath, K.; Raman, A.; Lie, D.; Chignell, M.H. Implementing Data Exfiltration Defense in Situ: A Survey of Countermeasures and Human Involvement. ACM Computing Surveys Publisher: ACM New York, NY. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, A.; Delfabbro, P.; Calic, D. Encouraging employee engagement with cybersecurity: How to tackle cyber fatigue. SAGE open 2021, 11, 21582440211000049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Guo, W.; Liu, X.; Chang, V. Privacy-preserving smart IoT-based healthcare big data storage and self-adaptive access control system. Information Sciences 2019, 479, 567–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eunaicy, J.C.; Suguna, S. Web attack detection using deep learning models. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 62, 4806–4813. [Google Scholar]

- Yüksel, O.; den Hartog, J.; Etalle, S. Reading between the fields: practical, effective intrusion detection for industrial control systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, 2016, pp.

- Williams, J.; King, J.; Smith, B.; Pouriyeh, S.; Shahriar, H.; Li, L. Phishing Prevention Using Defense in Depth. In Proceedings of the Advances in Security, Networks, and Internet of Things: Proceedings from SAM’20, ICWN’20, ICOMP’20, and ESCS’20; Springer, 2021; pp. 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Nathezhtha, T.; Sangeetha, D.; Vaidehi, V. WC-PAD: web crawling based phishing attack detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Carnahan Conference on Security Technology (ICCST). IEEE; 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Assefa, A.; Katarya, R. Intelligent phishing website detection using deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 8th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS). IEEE, Vol. 1; 2022; pp. 1741–1745. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Gupta, B.B.; Singh, A.K.; Saraswat, V.K. Orchestration of APT malware evasive manoeuvers employed for eluding anti-virus and sandbox defense. Computers & Security 2022, 115, 102627. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R. A survey on machine learning approaches and its techniques. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Students’ Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Science (SCEECS). IEEE; 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, S. A quick review of machine learning algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2019 International conference on machine learning, big data, cloud and parallel computing (COMITCon). IEEE; 2019; pp. 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, N.; Sharma, R.; Jindal, N. Machine learning and deep learning applications-a vision. Global Transitions Proceedings 2021, 2, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboretti, R.; Ceccato, R.; Pegoraro, L.; Salmaso, L. Design of Experiments and machine learning for product innovation: A systematic literature review. Quality and Reliability Engineering International 2022, 38, 1131–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement learning: An introduction; MIT press, 2018.

- Yoon, J.; Drumright, L.N.; Van Der Schaar, M. Anonymization through data synthesis using generative adversarial networks (ads-gan). IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics 2020, 24, 2378–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panesar, A.; Panesar, A. Machine learning algorithms. In Machine Learning and AI for Healthcare: Big Data for Improved Health Outcomes; Springer, 2021; pp. 85–144. [Google Scholar]

- Paper, D.; Paper, D. Predictive Modeling Through Regression. In Hands-on Scikit-Learn for Machine Learning Applications: Data Science Fundamentals with Python; Springer, 2020; pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- VanDam, C.; Masrour, F.; Tan, P.N.; Wilson, T. You have been caute! early detection of compromised accounts on social media. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining, 2019; pp. 25–32.

- Sambangi, S.; Gondi, L. A machine learning approach for ddos (distributed denial of service) attack detection using multiple linear regression. In Proceedings of the Proceedings. MDPI; 2020; Vol. 63, p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.K.; Dubes, R.C. Algorithms for clustering data; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ezugwu, A.E.; Ikotun, A.M.; Oyelade, O.O.; Abualigah, L.; Agushaka, J.O.; Eke, C.I.; Akinyelu, A.A. A comprehensive survey of clustering algorithms: State-of-the-art machine learning applications, taxonomy, challenges, and future research prospects. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2022, 110, 104743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H. Machine learning: Algorithms, real-world applications and research directions. SN computer science 2021, 2, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolfsson, A.; Ackerman, M.; Brownstein, N.C. To cluster, or not to cluster: An analysis of clusterability methods. Pattern Recognition 2019, 88, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, C.M.; Torralba, A.; Guibas, L.; DiCarlo, J.; Chellappa, R.; Hodgins, J. Next-generation deep learning based on simulators and synthetic data. In Trends in cognitive sciences; Elsevier, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Z.; Hazel, J.W.; Clayton, E.W.; Vorobeychik, Y.; Kantarcioglu, M.; Malin, B.A. Sociotechnical safeguards for genomic data privacy. Nature Reviews Genetics 2022, 23, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Gou, C.; Duan, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, X.; Wang, F.Y. Generative adversarial networks: introduction and outlook. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2017, 4, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Communications of the ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar, K.N.; Shanthi, M. Deepfake: An Endanger to Cyber Security. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Smart Systems (ICSCSS); 2023; pp. 1542–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azab, A.; Khasawneh, M. MSIC: Malware Spectrogram Image Classification. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 102007–102021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjovsky, M.; Chintala, S.; Bottou, L. Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning.; 2017; pp. 214–223. ISSN 2640-3498. [Google Scholar]

- Enisa. Cybersecurity of AI and Standardisation, 2023.

- Bouacida, N.; Mohapatra, P. Vulnerabilities in federated learning. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 63229–63249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, I.; Gupta, R.; Singh, A.K.; Buyya, R. MLPAM: A machine learning and probabilistic analysis based model for preserving security and privacy in cloud environment. IEEE Systems Journal 2020, 15, 4248–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dr. Araddhana Arvind.; Deshmukh.; Sheela N. Hundekari.; Yashwant Dongre.; Dr. Kirti Wanjale.; V. Maral.; Deepali Bhaturkar. Explainable AI for Adversarial Machine Learning: Enhancing Transparency and Trust in Cyber Security. Journal of Electrical Systems, 2024; S2ID: e2729caef077af43f084f8920483f24372d280cb. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Gupta, G.P.; Tripathi, R. An ensemble learning and fog-cloud architecture-driven cyber-attack detection framework for IoMT networks. Computer Communications 2021, 166, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganaie, M.A.; Hu, M.; Malik, A.K.; Tanveer, M.; Suganthan, P.N. Ensemble deep learning: A review. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2022, 115, 105151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Luo, Z.; Klabjan, D.; Zhang, F. Efficient architecture search for continual learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems Publisher: IEEE. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan, S.; Kumar, A. The balancing trick: Optimized sampling of imbalanced datasets—A brief survey of the recent State of the Art. Engineering Reports 2021, 3, e12298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enisa. Securing Machine Learning Algorithms, 2021.

- OWASP. OWASP Top 10 for Large Language Model Applications | OWASP Foundation, 2023.

- Chen, Z.; Tang, M.; Li, J. Inversion Attacks against CNN Models Based on Timing Attack. Security and Communication Networks 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.Z.H.; Agrawal, A.; Coburn, C.; Asghar, H.J.; Bhaskar, R.; Kaafar, M.A.; Webb, D.; Dickinson, P. On the (in) feasibility of attribute inference attacks on machine learning models. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P). IEEE, 2021, pp. 232–251.

- Ala-Pietilä, P.; Bonnet, Y.; Bergmann, U.; Bielikova, M.; Bonefeld-Dahl, C.; Bauer, W.; Bouarfa, L.; Chatila, R.; Coeckelbergh, M.; Dignum, V. The assessment list for trustworthy artificial intelligence (ALTAI); European Commission, 2020.

- Apruzzese, G.; Colajanni, M.; Ferretti, L.; Marchetti, M. Addressing adversarial attacks against security systems based on machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 11th international conference on cyber conflict (CyCon). IEEE; 2019; Vol. 900, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, A.Y.; Chekole, E.G.; Ochoa, M.; Zhou, J. On the Security of Containers: Threat Modeling, Attack Analysis, and Mitigation Strategies. Computers & Security 2023, 128, 103140. [Google Scholar]

- Marino, D.L.; Wickramasinghe, C.S.; Manic, M. An Adversarial Approach for Explainable AI in Intrusion Detection Systems. In Proceedings of the IECON 2018 - 44th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society; 2018; pp. 3237–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyam, S. Artificial Intelligence’s Impact on Social Engineering Attacks 2022.

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wei, Q.; Wang, Q. Neufuzz: Efficient fuzzing with deep neural network. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 36340–36352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, D.; Parida, V.; Palmié, M.; Wincent, J. How AI capabilities enable business model innovation: Scaling AI through co-evolutionary processes and feedback loops. Journal of Business Research 2021, 134, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uren, V.; Edwards, J.S. Technology readiness and the organizational journey towards AI adoption: An empirical study. International Journal of Information Management 2023, 68, 102588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, C.C. Lessons learned from co-governance approaches–Developing effective AI policy in Europe. In The 2021 Yearbook of the Digital Ethics Lab; Springer, 2022; pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lwakatare, L.E.; Crnkovic, I.; Bosch, J. DevOps for AI–Challenges in Development of AI-enabled Applications. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Software, Telecommunications and Computer Networks (SoftCOM). IEEE; 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).