1. Introduction

With the growing strategic demand for marine resource exploitation, ecological environment protection, and underwater military defense, underwater object detection has become an increasingly critical component of intelligent ocean perception. Its applications span multiple domains, including marine biodiversity monitoring, safety inspection of subsea pipelines and facilities, autonomous navigation of unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), and underwater security operations. Compared with terrestrial scenarios, the underwater environment exhibits more complex and severe optical characteristics. Due to the absorption and scattering of light in water, underwater images often suffer from color distortion, low contrast, and blurred details. These degradations not only hinder human visual interpretation but also significantly impair the performance of vision-based automated detection systems. Therefore, developing efficient and robust underwater object detection techniques is of great significance not only for advancing marine scientific research and resource utilization but also for national security and the construction of intelligent ocean engineering.

Image enhancement is an indispensable preprocessing step to ensure subsequent detector performance in underwater object detection. In general computer vision tasks, conventional methods such as histogram equalization, contrast stretching, adaptive histogram equalization (e.g., CLAHE), and color normalization are often applied. While these techniques can temporarily improve visual quality, they fail to address the non-uniform degradations, color shifts, and detail losses commonly present in underwater imagery.

To overcome the limitations of traditional approaches in complex underwater environments, recent studies have increasingly adopted hybrid strategies that combine physical modeling with deep learning. These methods go beyond simple contrast adjustments by incorporating optical priors, generative adversarial networks (GANs), and Transformer architectures to model degradation more effectively. For instance, the DICAM network deeply integrates channel compensation with attention mechanisms, enabling natural color restoration and detail enhancement while maintaining physical interpretability [

1]; FunIEGAN leverages an adversarial framework for real-time enhancement through end-to-end training, significantly improving the perceptual quality of underwater targets [

2]; Rep-UWnet employs lightweight convolutions and residual designs to achieve strong enhancement performance with minimal computational cost, making it suitable for embedded deployment [

3,

4]. More recent approaches such as TOPAL and UDAformer represent emerging trends, utilizing adversarial-perception optimization and the global modeling capacity of Transformers, respectively, to address non-uniform degradation while preserving structural consistency [

5,

6,

7]. Collectively, these advances mark a shift from “experience-driven” enhancement to “physics- and data-driven” paradigms, laying a solid foundation for high-quality underwater perception and detection.

Beyond image enhancement, detection models themselves play a decisive role in underwater recognition tasks. Traditional two-stage detectors such as Faster R-CNN [

8] offer high accuracy in general vision tasks but are difficult to deploy on underwater platforms with real-time constraints due to their complex region proposal and feature alignment steps [

9,

10,

11]. In contrast, single-stage detectors such as YOLO and SSD, with their end-to-end structures and faster inference speeds, have become mainstream in underwater detection. However, due to image degradation, these detectors still struggle with low-contrast targets, small objects, and complex backgrounds. Recent works have proposed various improvements: for example, the SWIPENET framework introduces multi-scale attention to enhance small-object detection and robustness to noise [

12]; U-DECN integrates deformable convolutions and denoising training into the DETR framework, boosting deployment efficiency [

13]; NAS-DETR combines neural architecture search with FPN and Transformer decoders, achieving promising results on both sonar and optical underwater imagery [

14]; PE-Transformer and AGS-YOLO demonstrate the potential of Transformers and multi-scale fusion for underwater detection [

15,

16]; meanwhile, YOLOv5 variants incorporating semantic modules and attention-based detection heads further improve small-object detection [

17]. These studies highlight that although progress has been made, existing detection models still face trade-offs between accuracy and efficiency under complex degraded conditions [

18].

The introduction of Transformer architectures offers new opportunities for underwater detection. Standard Vision Transformers (ViTs) possess strong global modeling capability, enabling them to capture long-range dependencies and handle complex background-target interactions. However, their high computational cost and large memory footprint severely constrain deployment on resource-limited platforms such as UUVs [

19,

20,

21]. Recent research has explored multiple solutions: ViT-ClarityNet integrates CNNs and ViTs to enhance low-quality image representation [

22]; FLSSNet leverages a CNN–Transformer–Mamba hybrid structure to improve long-range dependency modeling and noise suppression [

23]; the RVT series emphasizes position-aware attention scaling and patch-wise augmentation to enhance robustness [

24]; AdvI-token ViT introduces adversarial indicator tokens to detect perturbations during inference [

25]. Existing surveys have also pointed out that while Transformers show promise in underwater detection, systematic studies on energy optimization and adversarial adaptation remain lacking [

26,

27]. These developments form the methodological basis of our Adaptive Vision Transformer (A-ViT), whose dynamic token pruning and early-exit strategies aim to reduce energy consumption while maintaining accuracy and enhancing robustness in degraded and adversarial scenarios.

In adversarial underwater environments, security defense is equally critical. Due to the inherently low quality of underwater images, models are more vulnerable to even subtle perturbations, creating favorable conditions for adversarial attacks. Previous research has shown that unmodified Vision Transformer architectures are especially susceptible to adversarial manipulations, with unstable internal representations even under minimally perturbed inputs [

28,

29,

30]. For example, AdvI-token ViT introduces robustness-discriminating tokens at the input layer to improve adversarial detection [

31]. Related reviews also emphasize that practical deployment must account for distribution shifts, noise interference, and intentional attacks, advocating for adversarially robust frameworks [

32,

33]. In underwater settings, adversarial patch attacks can even be disguised as coral textures or sand patches, making them stealthier and more dangerous [

34]. Therefore, this study addresses not only energy efficiency and detection accuracy but also proposes defense strategies against novel threats such as energy-constrained attacks, ensuring the security and usability of detection frameworks. However, current defense mechanisms remain insufficient: most focus on natural or general image tasks, with limited consideration of underwater-specific degradations and low-quality conditions. Additionally, existing defenses are typically confined to single levels (e.g., adversarial training or input correction), lacking integrated, multi-level strategies spanning image enhancement, detection optimization, and Transformer-level defense. This gap is particularly evident on resource-limited underwater platforms, where models may fail to deploy despite promising laboratory results due to excessive energy consumption or adversarial vulnerabilities [

35].

In summary, current research in underwater object detection is evolving from isolated efforts in image enhancement or model optimization toward multi-factor collaborative solutions. Nevertheless, limitations persist in energy efficiency, adversarial robustness, and systematic integration, hindering practical deployment in complex underwater environments. To this end, this paper proposes an Adaptive Vision Transformer (A-ViT)-based underwater detection framework that achieves breakthroughs across image enhancement, lightweight detection, energy-efficient modeling, and multi-level adversarial defense. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

Underwater imaging hardware framework: A theoretical analysis system is established covering power modeling, endurance estimation, and thermal constraints. Combined with material selection and empirical data, a feasible solution is proposed for shallow-, mid-, and deep-water mission modes.

Image processing module: HAT-based super-resolution and DICAM staged enhancement are integrated for clarity restoration, color correction, and contrast enhancement. Experiments and ablation studies confirm that this module substantially improves detection accuracy.

Adaptive Vision Transformer (A-ViT): Dynamic token pruning and early-exit strategies enable on-demand computation, significantly reducing latency and GPU memory usage. Together with fallback and key-region preservation mechanisms, A-ViT enhances robustness under adversarial perturbations.

Improved detector architecture (YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN): Coordinate attention and a high-order spatial feature pyramid are incorporated into the neck, boosting detection of small and blurred objects while providing accuracy and robustness gains with minimal additional computational cost.

Collectively, this work establishes a closed-loop design that integrates hardware feasibility, image preprocessing, energy-efficient Transformer modeling, and optimized detector architecture, thereby providing a systematic solution for building efficient, robust, and secure underwater intelligent perception systems.

2. Materials and Methods

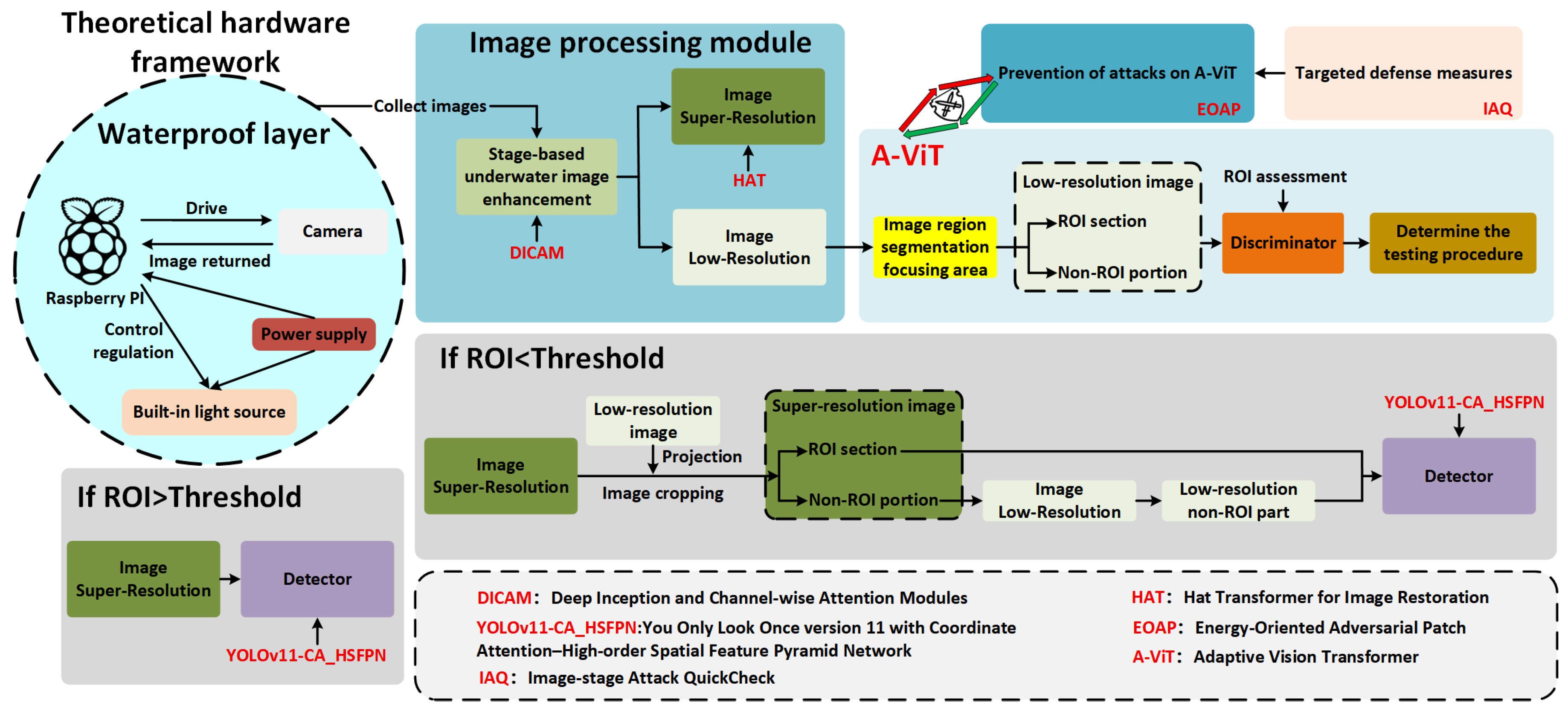

The overall system modules are illustrated in

Figure 1. Centered on the task of underwater object detection, a systematic analysis and set of improvements are introduced across hardware design, image preprocessing, A-ViT-based region-of-interest (ROI) segmentation, detection model optimization, and adversarial defense mechanisms.

At the hardware level, an adaptive imaging framework is proposed with illumination and acquisition conditions tailored for underwater scenarios. The feasibility of this design, as well as key material selections, are validated through theoretical modeling, thereby supporting subsequent software modules and forming a closed-loop system.

In the image preprocessing stage, super-resolution reconstruction, contrast enhancement, and color correction are applied to effectively restore clarity and discriminative features. These enhancements provide high-quality input for the A-ViT attention-based ROI segmentation and downstream detectors.

The A-ViT ROI segmentation module serves as the system’s core component. It incorporates an internal discriminator that rapidly filters ROI values based on pre-defined thresholds and dispatches images to the most suitable detection scheme. This ensures detection accuracy while achieving minimal energy consumption.

For the detection model, an improved YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN architecture is proposed, in which coordinate attention and a high-order spatial feature pyramid are integrated into the neck. This design enhances detection performance for small and blurred targets.

Finally, to mitigate risks posed by potential adversarial attacks, the system integrates security redundancy with the A-ViT’s key-region preservation strategy, enabling robust detection coverage and resilience under interference.

2.1. Underwater Imaging Hardware Design

In an underwater object detection system, the design of imaging hardware must balance energy consumption, endurance, and heat dissipation under constrained energy budgets, while ensuring structural strength and material reliability. In this section, a theoretical framework for power modeling, endurance estimation, and material selection is established, as illustrated in the hardware block of

Figure 1 (top left).

The system mainly consists of the following components:

Main control platform: Embedded processing unit, with power consumption denoted as .

Imaging device: Image sensor or camera module, with power consumption denoted as .

Illumination module: Light source unit (e.g., LED array), with power consumption denoted as and duty cycle ,where increases with operating depth.

Power supply system: Battery pack with nominal voltage

, capacity

, and total energy:

The instantaneous system power consumption is determined by the power of each module and its duty cycles:

Where is the duty cycle of algorithm execution and represents the incremental power induced by algorithmic operations.

Accordingly, the average system power can be expressed as:

Considering power efficiency and the usable energy coefficient, the theoretical endurance time of the battery is:

where

is the usable energy coefficient (0.7–0.9, accounting for depth of discharge and temperature effects), and

is the power conversion efficiency (0.85–0.95).

To further quantify system performance during the imaging process, a per-frame energy consumption index is introduced:

where

is the frame rate (frames/s).

is expressed in joules per frame (J/frame), representing the average energy required to capture a single image. For engineering comparison, this can be converted into energy per thousand frames:

with units of watt-hours per 1000 frames (Wh/1000 frames), which can serve as a direct quantitative metric for comparing different systems and algorithms.

In addition, thermal constraints must be satisfied to avoid system overheating:

where

is the effective surface area of the enclosure required for heat dissipation (m²),

is the convective heat transfer coefficient in water (200–800 W·m⁻²·K⁻¹), and

is the allowable steady-state temperature rise.

In summary, this section establishes a theoretical analysis framework for underwater imaging hardware, covering system composition, power modeling, endurance estimation, and thermal dissipation constraints. Through the derivation of Eqs. (1)–(7) and parametric modeling, the framework enables prediction of energy consumption and endurance across varying task duty cycles. Furthermore, material selection for the housing and optical window is analyzed in the experimental section, where thermal conductivity, structural strength, and environmental adaptability are quantitatively evaluated to provide a theoretical basis for engineering design.

2.2. Image Processing Module

One of the primary challenges in underwater object detection arises from the severe degradation of imaging quality. The absorption and scattering of light in water often result in insufficient resolution, color distortion, reduced contrast, and blurred textures. These degradations not only weaken human visual perception of underwater scenes but also directly impair the performance of deep learning–based detection models. Without effective enhancement, detectors typically fail to extract discriminative features from low-quality inputs, leading to reduced accuracy and insufficient robustness.

To address this issue, a multi-stage image enhancement module is designed at the front end of the detection framework. This module combines super-resolution reconstruction with underwater image enhancement techniques to compensate for resolution deficiencies while correcting color and contrast distortions, thereby providing high-quality inputs for subsequent detection models. Specifically, the module consists of two complementary components: image super-resolution, which focuses on restoring clarity and fine details, and staged underwater enhancement, which emphasizes color correction and texture reinforcement. Together, these processes enable comprehensive optimization of input image quality.

2.2.1. Image Super-Resolution

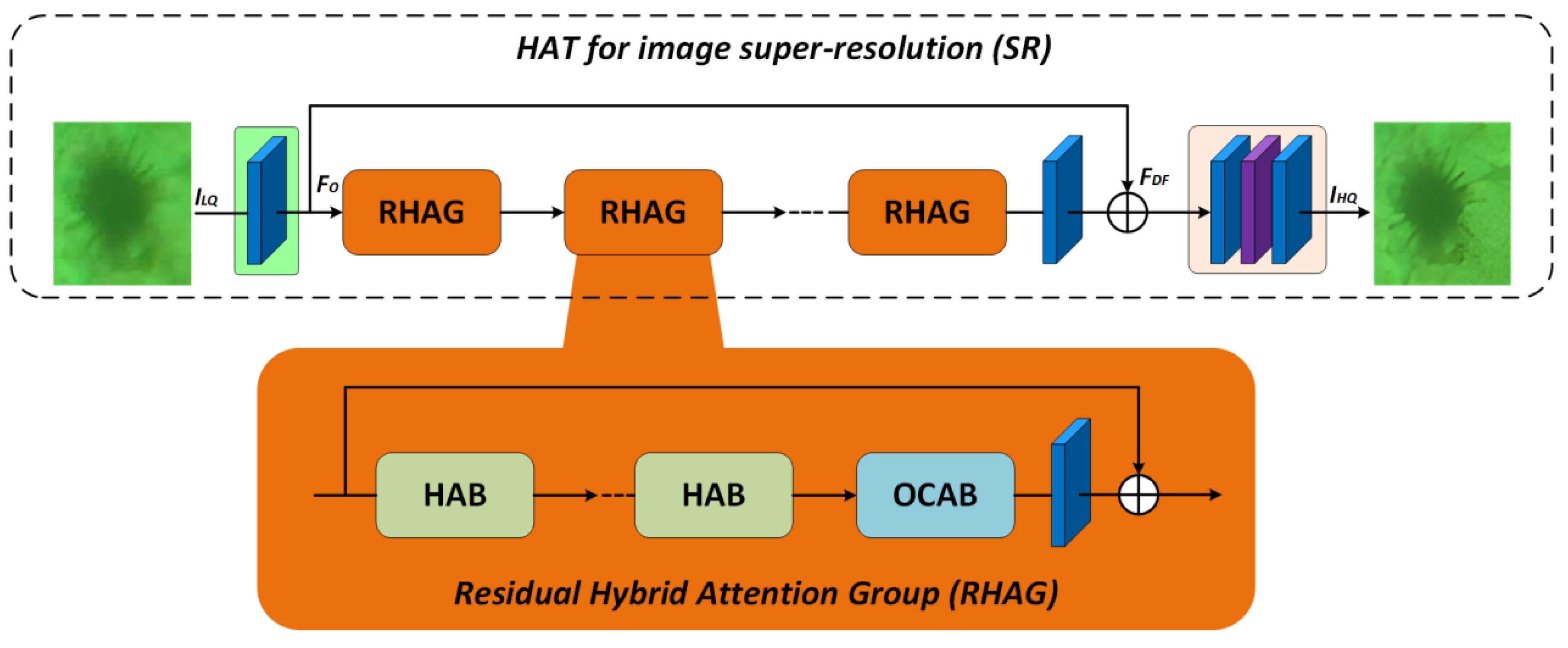

In the proposed underwater object detection system, blur, low resolution, and degradation of fine details are among the key bottlenecks affecting detection accuracy. To address this issue, the image preprocessing stage incorporates the Hybrid Attention Transformer for Image Restoration (HAT) [

36]. By combining hierarchical feature construction with cross-domain attention mechanisms, HAT effectively restores degraded image details such as textures and edge structures. Unlike traditional convolution-based super-resolution methods, HAT leverages the global modeling capability of Transformers, integrating global semantics with local features. This makes it particularly suitable for handling the non-uniform and spatially variant degradations often observed in underwater imagery.

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the HAT architecture consists of three main components: shallow feature extraction, deep feature construction via stacked residual attention groups, and final high-resolution reconstruction. Specifically, the input low-quality image

is first mapped to shallow features

. These features are then processed through

stacked Residual Hybrid Attention Groups (RHAGs), followed by up-sampling using PixelShuffle, which outputs the high-resolution image

:

Within each RHAG, residual connections facilitate feature propagation, while attention mechanisms enhance cross-channel and cross-domain feature interactions. The formulation is expressed as:

The Hybrid Attention Block (HAB) serves as the core unit of RHAG. By integrating window-based multi-head self-attention (W-MSA) with local convolutions, HAB establishes joint modeling of long-range dependencies and local correlations. The self-attention operation is defined as:

where

,

, and

denote the query, key, and value matrices, respectively;

is the feature dimension; and

is a learnable positional bias term, enabling enhanced positional encoding and sensitivity.

To alleviate vanishing gradient and convergence issues in deep residual training, HAT introduces LayerScale residual modulation at the output stage, formulated as:

Where and are learnable scaling parameters that stabilize gradient propagation and improve adaptivity during early-stage training.

Furthermore, HAT incorporates two additional attention mechanisms: the Overlapping Cross-Attention Block (OCAB), which aggregates overlapping window regions to strengthen boundary structure representation, and the Channel Attention Block (CAB), which refines inter-channel correlations to enhance discriminative power. Together, these mechanisms enable RHAG to achieve synergistic enhancement across multiple scales, improving sharpness and structural fidelity in reconstructed images.

At the reconstruction stage, PixelShuffle is applied to up-sample the deep feature maps, restoring them to the target high-resolution output. Experimental results have shown that HAT outperforms conventional methods such as RCAN in terms of PSNR and SSIM metrics, validating its superior ability to preserve fine details and structural consistency. Therefore, HAT is integrated as the image super-resolution component of our proposed framework, ensuring that even under complex degradation conditions, high-quality and stable inputs can be delivered to the subsequent detection modules.

2.2.2. Staged Underwater Image Enhancement

The unique optical properties of underwater environments make imaging quality significantly worse compared with terrestrial scenes. Light propagation in water is subject to substantial absorption and scattering, where red wavelengths attenuate rapidly while blue and green dominate, resulting in severe color imbalance and bias. In addition, scattering caused by suspended particles leads to reduced contrast and blurred textures. Consequently, underwater images often suffer from color cast, poor contrast, and texture degradation, which hinder reliable feature extraction for detection and recognition tasks.

In practical applications, underwater image enhancement is not merely a low-level restoration task but also a critical prerequisite for reliable computation in energy-constrained missions. For underwater navigation, ecological monitoring, and military reconnaissance, poor image quality severely affects perception accuracy and reliability. Without enhancement, deeper imaging layers may accumulate distortions, degrading downstream feature distributions and impairing model robustness. Therefore, image enhancement in underwater environments is indispensable for ensuring stable and trustworthy system performance in complex operational conditions.

To address these issues, this study adopts a staged enhancement strategy that integrates physics-based priors with deep learning. The overall workflow consists of two main stages:

- (1)

Physics-based modeling of degradation.

We begin with a classical underwater degradation model to describe the formation process:

where

is the observed image,

is the latent clean image,

denotes transmission, and BBB represents background light intensity.

To compensate for severe color cast caused by rapid attenuation of red light, a channel-wise compensation mechanism is introduced. The corrected image for channel

is expressed as:

Where is the observed value in channel , and is the corresponding background light. This formulation explicitly restores red-channel attenuation and re-balances three-channel intensity.

- (2)

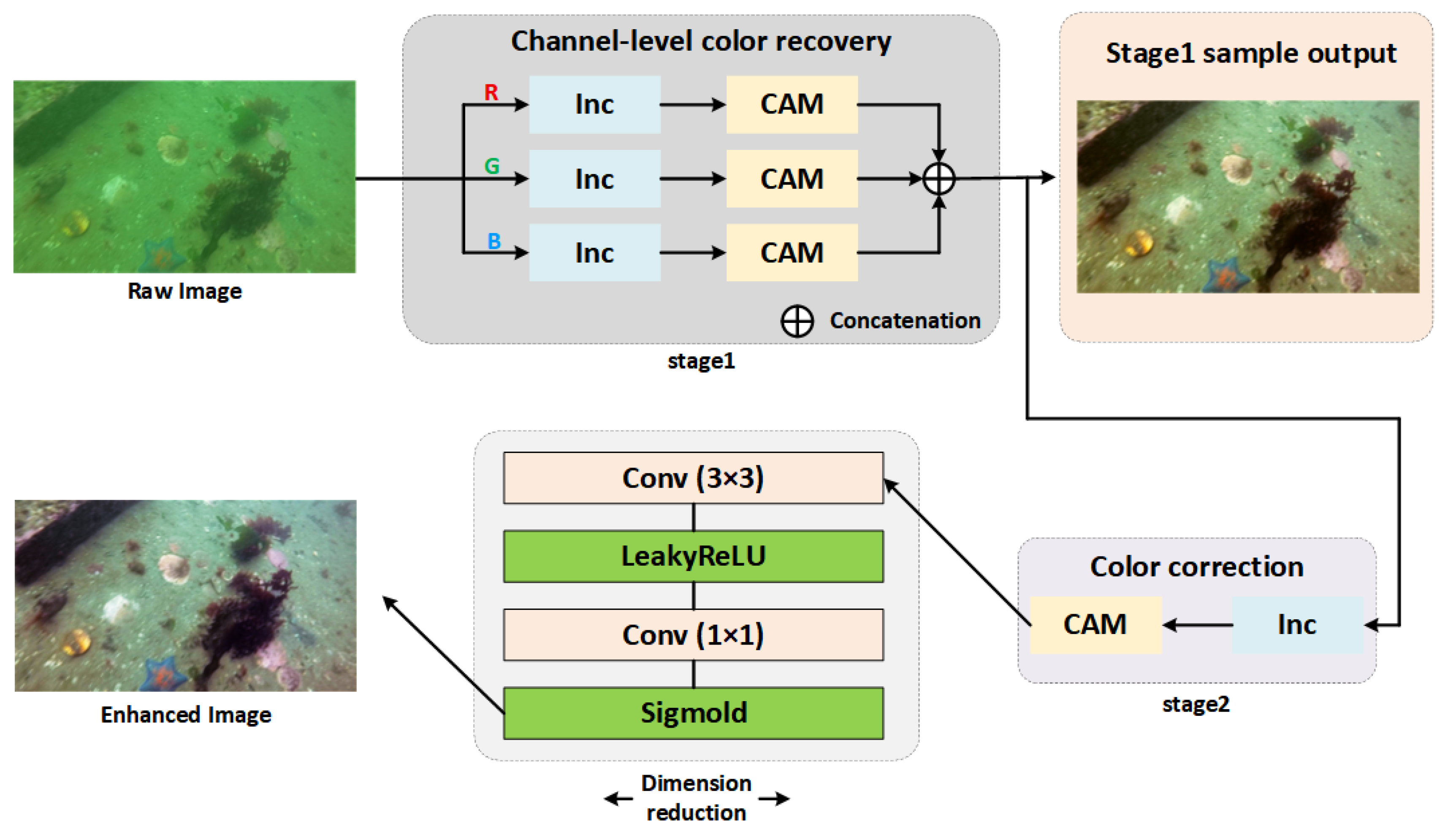

Deep learning–based enhancement with DICAM.

Building on the physics-based correction, we further introduce a Deep Image Correction and Adaptive Modeling (DICAM) network, as illustrated in

Figure 3. The network consists of two successive sub-stages:

- A.

Stage 1: Channel-level recovery. The physics-corrected R/G/B channels are processed with channel attention modules (CAMs) to refine inter-channel correlations and suppress severe chromatic bias. Overlapping local information is aggregated to strengthen structural edges and reduce scattering noise.

- B.

Stage 2: Color correction and dimensional reduction. A compact module comprising convolution (3×3), LeakyReLU, and convolution (1×1) layers compresses redundant features, followed by a Sigmoid activation to produce final enhanced outputs.

The overall enhancement process can be expressed as:

where

represents a nonlinear mapping parameterized by deep network weights

, which integrates physics-based priors with learned feature representations.

Compared with conventional purely physics-driven or data-driven methods, DICAM achieves a hybrid paradigm of “physics-guided and data-adapted fusion.” On the one hand, the physics-based priors ensure natural color consistency and structural interpretability; on the other hand, the learned enhancement provides adaptability to diverse degraded conditions. Experimental evaluations show that DICAM effectively improves contrast, restores color balance, and enhances fine texture reconstruction. This method overcomes the bottlenecks of existing approaches that struggle to balance color correction, contrast enhancement, and detail preservation, thereby delivering stable, high-quality visual inputs for downstream detection and situational understanding.

It is worth noting that in our staged strategy, physics-based correction and DICAM-based enhancement form a progressive loop: the physical model addresses global degradation while DICAM refines local structures and adaptive details. The effectiveness of this staged design will be comprehensively validated in subsequent experiments.

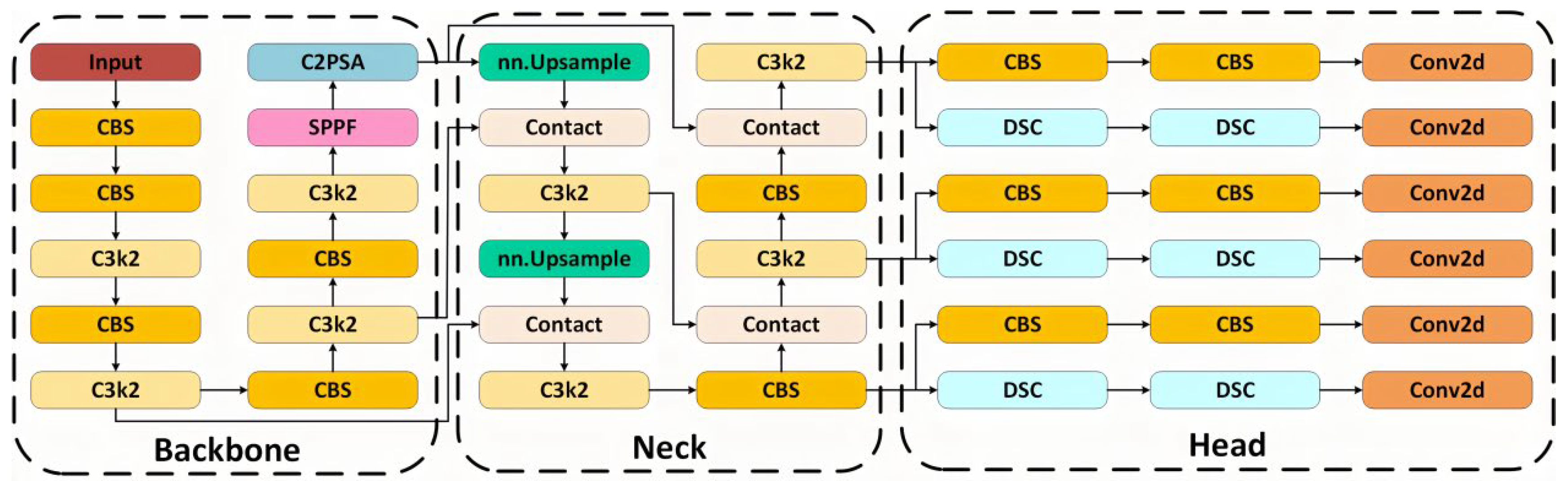

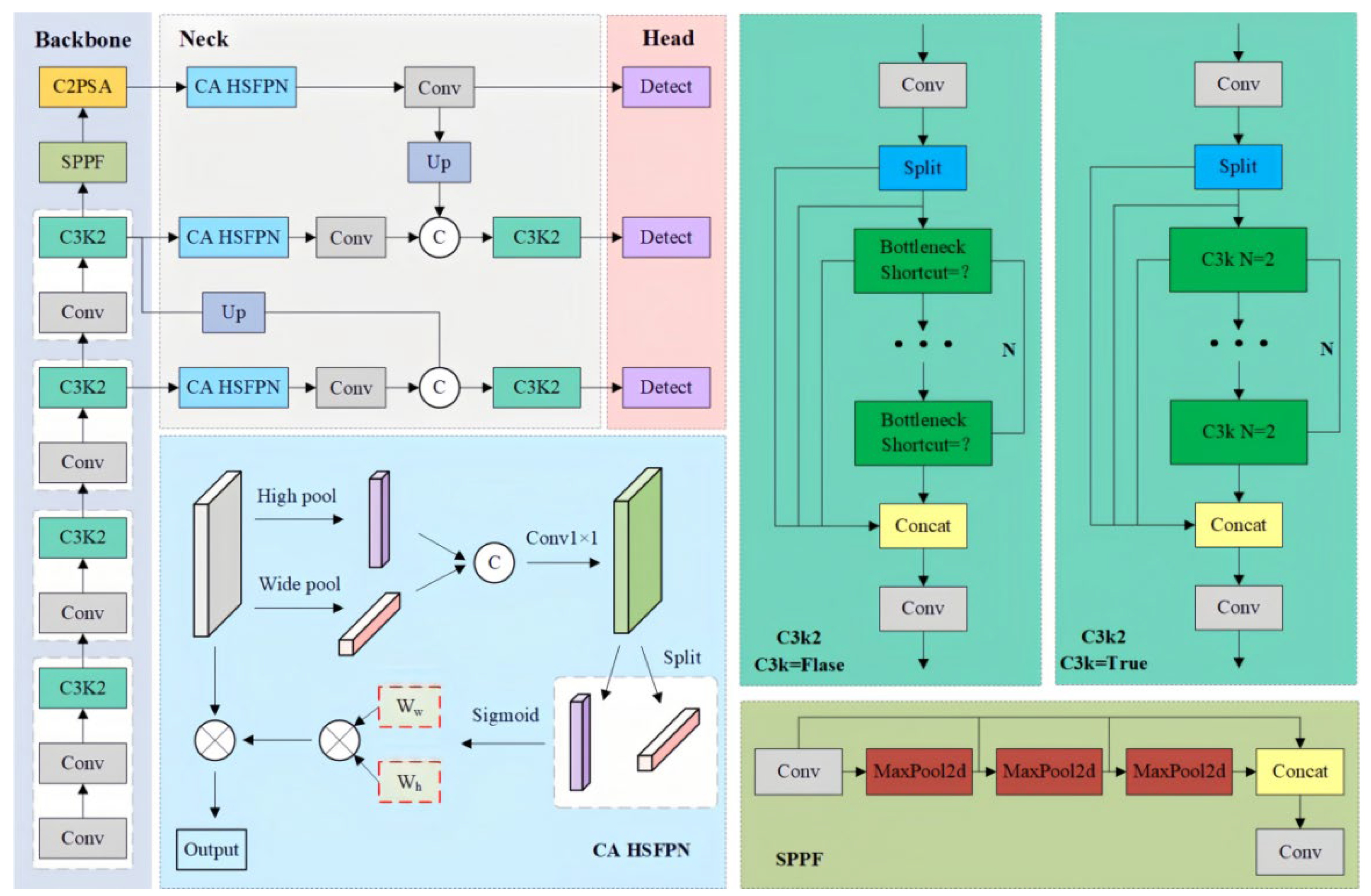

2.3. Improved Detector: YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN

YOLOv11-S, as the latest mainstream version of the YOLO series, adopts an end-to-end Backbone–Neck–Head detection framework. Its architecture is shown in

Figure 4. The backbone performs multi-layer convolutional extraction using CBS and C3k2 modules, while the neck fuses multi-scale features through feature pyramid networks (FPN/PAN). The head is responsible for bounding box regression and classification. The overall computation can be formulated as:

where

is the input image, and

,

, and

denote feature extraction, feature fusion, and detection prediction functions, respectively.

is the activation function.

Although YOLOv11-S demonstrates strong detection capability, its performance degrades in underwater environments due to light attenuation, scattering noise, and small target sizes. Specifically, two main limitations remain: (1) insufficient spatial directionality, leading to blurred target boundaries; and (2) difficulty in distinguishing small or low-contrast targets from cluttered backgrounds, causing missed and false detections.

To overcome these limitations, this study proposes an improved architecture, YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN, shown in

Figure 5. In this design, a Coordinate Attention–High-order Spatial Feature Pyramid Network (CA-HSFPN) module is incorporated into the neck to enhance spatial dependency modeling and improve small-target recognition.

CA-HSFPN Module Principles

The CA mechanism captures long-range dependencies while preserving precise positional information. Given an input feature

, CA performs average pooling along height and width dimensions:

The pooled features are concatenated and compressed through a

convolution and nonlinear activation

:

Directional weights are then generated via separate convolutions:

Finally, spatially-aware feature refinement is achieved as:

This enables dynamic weighting of horizontal and vertical dependencies, strengthening elongated and boundary structures of underwater targets.

- 2.

High-order Spatial Feature Pyramid Network (HSFPN).

On the basis of CA-enhanced features, HSFPN performs multi-level cross-scale fusion. The fused representation is expressed as:

Where denotes the iii-th backbone feature, is coordinate attention, and represents up-sampling and concatenation operations. Compared with conventional FPNs, this approach preserves geometric sensitivity and is well suited to fine-grained distribution patterns of underwater targets.

The overall detection process of the improved architecture is:

- 3.

Advantages of YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN

Compared with the original YOLOv11, the improved YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN offers the following benefits:

- (1)

Enhanced spatial directionality: Explicit modeling of long-range dependencies compensates for YOLOv11’s weakness in spatial feature capture.

- (2)

Improved small-target detection: CA-HSFPN facilitates discrimination of low-contrast small objects from noisy backgrounds, improving recall.

- (3)

Robustness reinforcement: Under challenging conditions such as low illumination and scattering, CA attention highlights structural cues, ensuring stable detection.

- (4)

Lightweight preservation: CA-HSFPN introduces only lightweight convolutions and pooling operations, adding negligible computational cost.

- (5)

Underwater adaptability: Targets with orientation-dependent distributions, such as fish schools, achieve better representation under CA-HSFPN, aligning with underwater scene characteristics.

In summary, YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN achieves balanced optimization of real-time inference speed, detection accuracy, and robustness compared with the original YOLOv11-S. This improvement is particularly suitable for complex underwater detection tasks. Furthermore, the proposed structure provides feasible technical support for practical deployment in underwater monitoring, resource exploration, and intelligent marine equipment.

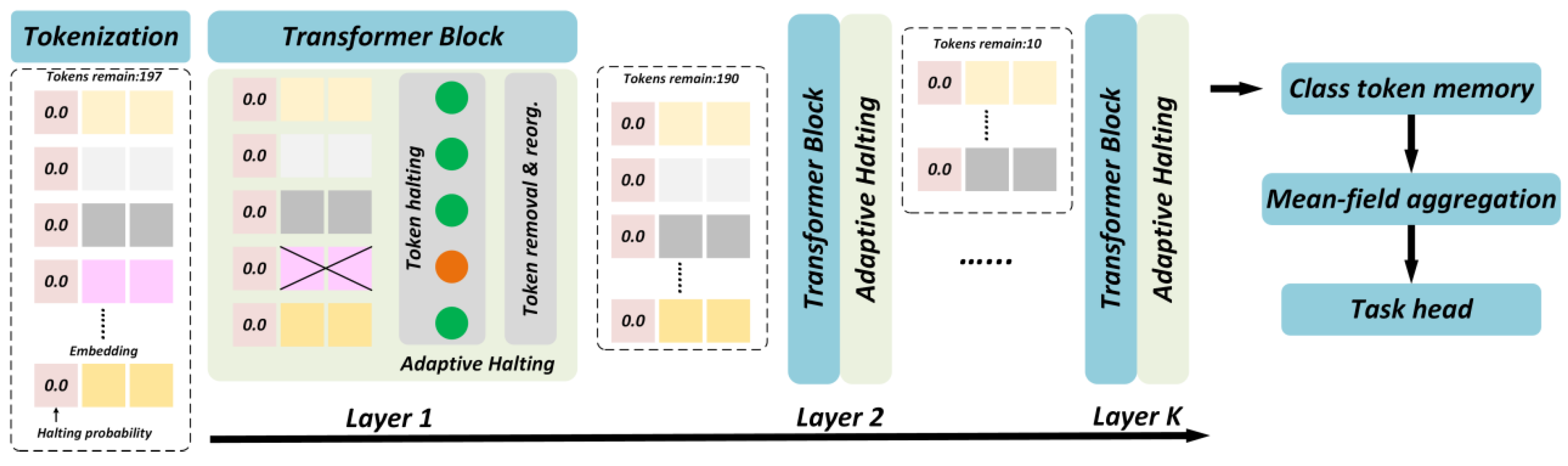

2.4. Adaptive Vision Transformer for Modeling in Adversarial Underwater Environments

In complex underwater adversarial environments, detection models must maintain robustness not only under conditions of insufficient illumination, color distortion, and suspended-particle scattering, but also against intentional adversarial perturbations. Conventional Vision Transformers (ViTs) process all patch tokens uniformly, leading to high computational redundancy and excessive memory consumption, which restrict deployment on resource-limited underwater platforms. To address this challenge, we introduce an Adaptive Vision Transformer (A-ViT) that employs dynamic token selection and early-exit strategies to enable on-demand computation (

Figure 6), thereby reducing computational overhead while maintaining robustness to perturbations.

- 1.

Dynamic Token Pruning

The core concept of ViT is to assess the importance of input tokens adaptively and retain only the most discriminative subset for further computation. Suppose an input image is partitioned into

patches, each represented as a token vector

. In a standard ViT, all tokens are passed through the Transformer encoder with complexity

. For efficiency, A-ViT introduces a token selection function

, which ranks tokens based on joint attention entropy and feature compactness, selecting the most informative subset:

where

is the token set,

denotes information entropy,

represents attention weight magnitude, and α\alphaα is a balancing coefficient. The operator

selects the top-

tokens with the highest discriminability, discarding the rest to reduce computation.

- 2.

Early-Exit Mechanism

A-ViT further incorporates early-exit branches within the Transformer layers. If the classification confidence of an intermediate output exceeds a threshold

, the model directly outputs predictions without traversing deeper layers:

where

denotes the feature set at layer

. For simple samples, inference is terminated early to save energy; for complex or adversarially perturbed samples, deeper layers are automatically activated to extract fine-grained features, ensuring robust predictions.

- 3.

Robustness-Oriented Token Importance

To further strengthen stability under adversarial conditions, A-ViT introduces a robustness-aware importance index. Given a token

, adversarial noise

, and perturbed token

, robustness importance is defined as:

where

is the perturbation distribution. Tokens with lower sensitivity to perturbations are prioritized, improving accuracy and reliability in adversarial underwater environments.

- 4.

Energy-Aware Computation

For efficiency, A-ViT is combined with mixed-precision training and attention acceleration techniques (e.g., FlashAttention). To further optimize memory usage, we model effective computation area by separating foreground ROI tokens and background tokens.

Foreground ROI retention: Regions with high saliency are preserved at full resolution for YOLO-based detection, ensuring accurate boundary recall.

Background down-sampling: Non-salient regions are down-sampled (e.g., to 0.5× or 0.25× resolution) and processed only once, reducing redundancy.

Fallback mechanism: If ROI coverage drops below threshold, the model reverts to full-resolution processing to avoid missing potential targets.

The effective computational area can be expressed as:

where

is the total image area, rrr is the foreground ratio, and sss is the background scaling factor.

For example, in a typical sparse-target scene with and , the effective processed area reduces to ~44% of the original, with accuracy nearly unchanged while peak memory and energy consumption are proportionally reduced.

In this framework, A-ViT acts not as a replacement detector but as a dynamic ROI regulator that prioritizes “focusing on salient objects while downplaying background clutter.” This design ensures that edge deployment can simultaneously meet memory and accuracy requirements, offering superior efficiency compared to full-image detection or purely visualization-driven approaches.

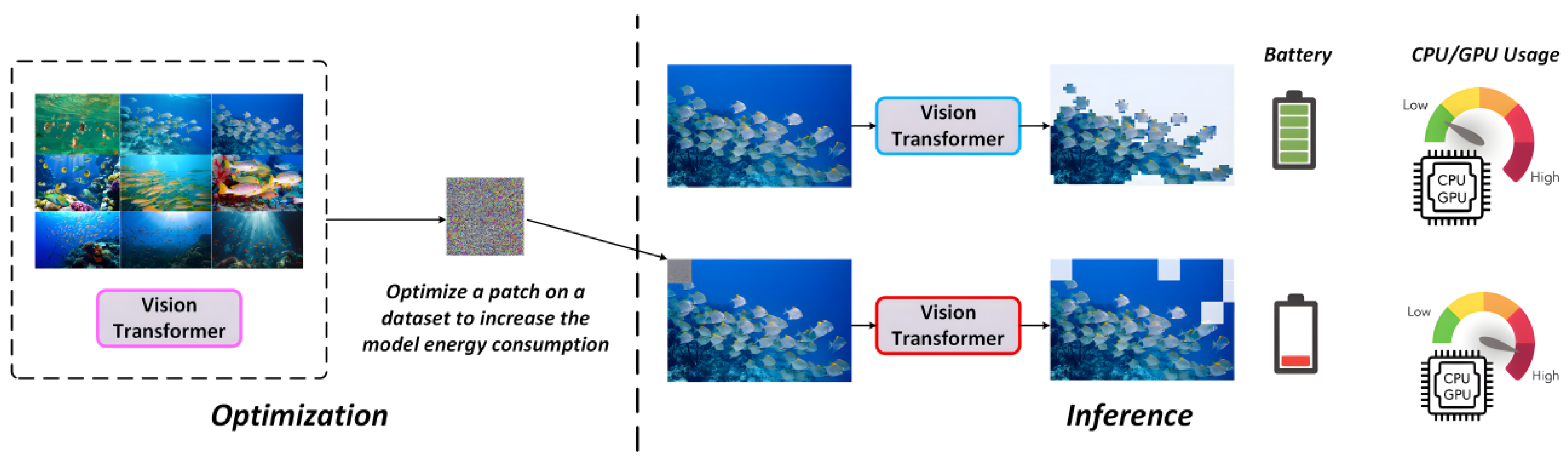

2.5. Energy-Constrained Adversarial Attacks and Vulnerability Analysis of A-ViT

Within the underwater detection framework, the introduction of the Adaptive Vision Transformer (A-ViT) enables significant reduction of redundant computation through dynamic token pruning and early-exit mechanisms, thereby balancing energy efficiency and detection accuracy. This property is particularly critical for resource-limited underwater platforms (e.g., autonomous underwater vehicles or remote monitoring systems). However, the dynamic inference feature of A-ViT simultaneously exposes new vulnerabilities that adversaries may exploit.

Recent studies have revealed that attackers can design Energy-Oriented Adversarial Patches (EOAPs) to exploit this mechanism. Specifically, EOAPs force the model to retain redundant or irrelevant tokens during inference, effectively degrading A-ViT into near full-scale computation. This significantly increases memory and computation cost, thereby eliminating the energy efficiency advantage of A-ViT.

Figure 7 illustrates the EOAP perturbation mechanism.

- 1.

Formulation of the Halting Mechanism

For an input image partitioned into tokens

, the halting probability of token

at the first layer is denoted by

. A token terminates computation early once the accumulated halting probability exceeds a threshold:

where

is the halting layer index of token

. To prevent premature or delayed termination, A-ViT introduces a ponder loss during training:

where

is the expected average halting depth. Additionally, to regularize the halting distribution toward a prior, a KL divergence penalty is employed:

The final joint loss function is thus:

where

is the detection task loss, and

,

are balancing coefficients to ensure efficient allocation of computation across easy and hard samples.

- 2.

EOAP Adversarial Objective

Under adversarial environments, attackers explicitly manipulate the halting mechanism by applying perturbations δ\deltaδ. The optimization target is:

where

represents perturbation constraints (e.g., amplitude bounds or masked regions), and

denotes computational cost (e.g., number of tokens retained or FLOPs). This objective enforces retention of more tokens during inference, forcing A-ViT into near full computation, thus nullifying its efficiency advantage.

In adversarial underwater environments, the threats of EOAPs can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

Natural camouflage. EOAPs can be visually concealed within low-contrast underwater textures such as coral patterns or sand ripples. These perturbations are difficult to distinguish through human vision or simple preprocessing, making them stealthy and dangerous.

- (2)

Practical constraints. Underwater missions are often extremely sensitive to inference latency. If EOAPs induce doubled or prolonged inference times, tasks may fail or incur severe consequences. For instance, in military scenarios, a delayed AUV detector may fail to recognize underwater mines or hostile targets in time, posing critical safety risks.

In summary, although A-ViT demonstrates remarkable advantages in energy-aware optimization, its dynamic inference mechanism exposes new vulnerabilities. Attackers can exploit EOAPs to negate efficiency gains and undermine mission reliability. Therefore, a key challenge for underwater deployment lies in balancing energy efficiency with adversarial robustness. This motivates the defense strategies that will be further elaborated in the subsequent section.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Analysis of Hardware Design and Material Selection Experiments

To further validate the theoretical framework of underwater imaging hardware introduced in

Section 2.1, we conducted experiments focusing on embedded platforms, imaging modules, illumination units, power systems, and optional acceleration components. Based on the previously established power modeling equations, we quantitatively analyzed key metrics—such as energy consumption, endurance, and heat dissipation—under three representative task modes. Unlike purely theoretical evaluation, this section provides specific device models, parameter configurations, and numerical demonstrations to verify the practical applicability of the proposed framework. Furthermore, we extend the analysis to material selection for external housings and optical windows.

The experimental setup included the following components: an embedded processor (Raspberry Pi 4B, 3–5 W), imaging module (Raspberry Pi Camera v2.1, 1.2 W), illumination module (10 W high-intensity LED array with adjustable duty ratio 20–100%), and power system (4S2P 18650 Li-ion battery pack, 14.8 V, 6 Ah, total capacity 88.8 Wh).

Based on operational depth, three task modes were defined:

- (1)

Shallow-water mode: LED duty ratio = 20%.

- (2)

Medium-depth mode: LED duty ratio = 80%.

- (3)

Deep-water mode: LED full power operation.

This classification simulates typical underwater application scenarios. Using the power equations, we computed average power, endurance, energy per frame, and required heat dissipation. Results are shown in

Table 1.

From

Table 1, the system achieves ~8.6 h of endurance in shallow-water mode, with energy consumption per frame as low as 0.53 J/frame, suitable for long-term cruising. In contrast, deep-water mode increases per-frame consumption to 1.77 J/frame, reducing endurance to ~2.6 h. Regarding thermal constraints, the maximum required dissipation area is 58.9 cm², which can be satisfied by standard aluminum alloy housings under a ≤15 K temperature rise. These findings confirm that the theoretical framework in

Section 2.1 remains valid under real hardware settings.

In addition to power and thermal indices, the physical properties of external housing and optical window materials significantly affect long-term reliability.

Table 2 summarizes the transparency, thermal conductivity, density, yield strength, seawater corrosion resistance, and cost of typical candidate materials.

Material Suitability Analysis

- 1.

Metals:

- (1)

Aluminum alloy (6061/5083): High thermal conductivity (120–170 W/m·K) and moderate strength (215–275 MPa) allow effective heat dissipation with relatively low weight, suitable for shallow and medium-depth tasks. However, long-term immersion requires anodizing or protective coatings due to limited corrosion resistance.

- (2)

Stainless steel (316L): Offers excellent seawater resistance, especially against pitting corrosion, though high density (8.0 g/cm³) limits portability.

- (3)

Titanium alloy (Ti-6Al-4V): Superior strength (800–900 MPa) and corrosion resistance make it the only viable choice for >300 m deep-sea missions despite higher cost.

- 2.

Transparent materials

- (1)

PMMA (Acrylic): High transparency (92–93%) and light weight (1.2 g/cm³) make it suitable for shallow (<50 m) low-load tasks. However, low strength (65–75 MPa) and poor durability limit deep-sea use.

- (2)

Polycarbonate (PC): Slightly lower transparency (88–90%) but better impact resistance than PMMA; suitable for shallow-to-medium depths (<100 m).

- (3)

Tempered glass: Transparency 90–92% with yield strength 140–160 MPa, applicable for medium depths (<300 m), though heavier and fracture-prone.

- (4)

Sapphire: Optimal candidate for deep-sea windows (>300 m) due to extreme strength (2000–2500 MPa), excellent corrosion resistance, and high optical stability. Cost, however, restricts large-scale use.

Optimal Structural Solutions

Integrating the results of

Table 1 and

Table 2, two structural strategies are proposed:

Fully transparent solution (PMMA/PC/Sapphire): Simplifies optical design but struggles to meet thermal dissipation requirements under high-load conditions; limited to shallow-water, low-power tasks.

Metallic housing + localized transparent window: Metals provide structural strength and heat dissipation, while the transparent window ensures optical imaging. This hybrid solution flexibly adapts to shallow, medium, and deep-water tasks, achieving balanced performance.

Thus, the optimal material recommendations are:

Shallow-water tasks: Aluminum alloy housing + PMMA/PC window.

Medium-depth tasks: Aluminum alloy or stainless steel housing + tempered glass window.

Deep-water tasks: Titanium alloy housing + sapphire window.

This layered material strategy ensures both mechanical robustness and thermal stability, while maintaining system efficiency and adaptability under varying underwater conditions.

The layered material-selection strategy proposed in this study provides a practical engineering solution that balances mechanical strength, thermal management, optical stability, and cost-effectiveness across shallow, medium, and deep-water tasks. By integrating lightweight alloys with transparent polymers for shallow-water applications, combining aluminum or stainless steel with tempered glass for medium depths, and employing titanium alloy with sapphire for deep-sea missions, the framework ensures long-term reliability under diverse marine environments. This design not only validates the applicability of the theoretical power–thermal models but also establishes a robust hardware foundation for the subsequent integration of the A-ViT system, thereby enhancing both energy efficiency and adversarial robustness in real-world underwater deployments.

3.2. Experimental Analysis of the Image Processing Module

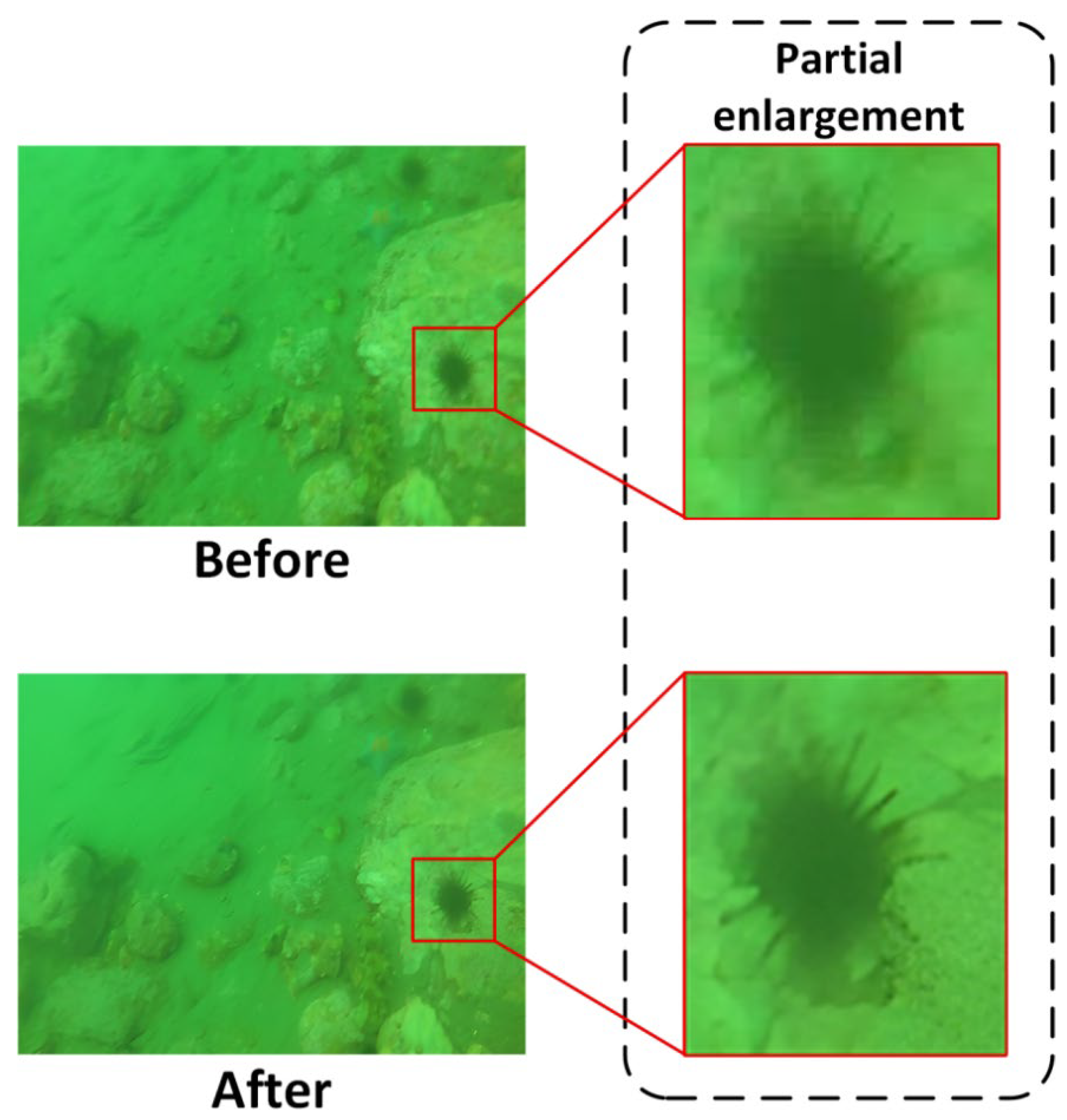

3.2.1. Image Super-Resolution

The optical degradation effect of underwater imaging generally results in insufficient sharpness and the loss of fine details, particularly in scenarios involving long-range observation or small-object recognition. The lack of high-frequency information significantly constrains the discriminative capacity of detection models. To address this issue, we incorporated a Hybrid Attention Transformer (HAT)-based super-resolution reconstruction module in the preprocessing stage, aiming to enhance structural integrity and texture representation of input images.

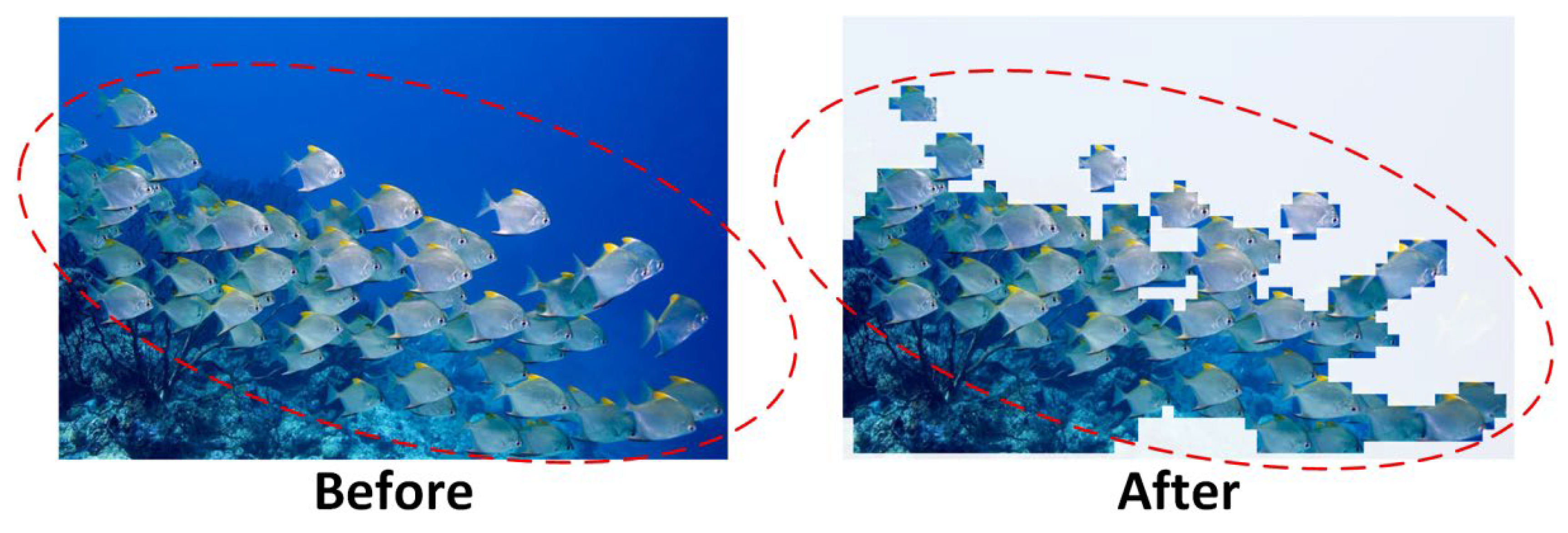

Figure 8 illustrates the visual comparison of underwater images before and after super-resolution reconstruction. In the blurred image (Before), object boundaries, such as those of marine organisms, are severely smeared, and spiny structures are nearly indistinguishable from the surrounding background. After reconstruction (After), the object boundaries appear sharper, fine details are effectively restored, and the overall perceptual clarity and sharpness of the image are significantly improved.

Quantitative evaluations are summarized in

Table 3. The PSNR improved from 15.62 dB to 27.29 dB (+74.8%), indicating a significant reduction in pixel-level noise. The SSIM increased from 0.186 to 0.885 (+375.8%), reflecting comprehensive recovery of structural consistency and local correlation. Meanwhile, MSE decreased from 0.0151 to 0.00187 (−87.6%), demonstrating the superiority of the reconstructed image in pixel precision.

To further verify the reconstruction effectiveness,

Table 3 clearly shows the advantage of HAT in both visual and objective evaluation metrics. Specifically, the PSNR increased from 15.62 dB in blurred images to 27.29 dB after reconstruction, representing a relative improvement of 74.8%, which demonstrates effective suppression of pixel-level noise. The SSIM improved dramatically from 0.186 to 0.885, corresponding to a 375.8% increase, indicating strong recovery of structural similarity and global consistency. Meanwhile, the MSE decreased from 0.0151 to 0.00187, a reduction of 87.6%, confirming enhanced fidelity in pixel-wise reconstruction accuracy.

The results suggest that the HAT-based super-resolution module not only achieves noticeable improvements in visual clarity but also yields consistent advantages in objective metrics. By restoring high-frequency structural details and suppressing noise, the reconstructed images provide more discriminative inputs, which are particularly beneficial for detecting small objects and weak-texture targets in underwater environments.

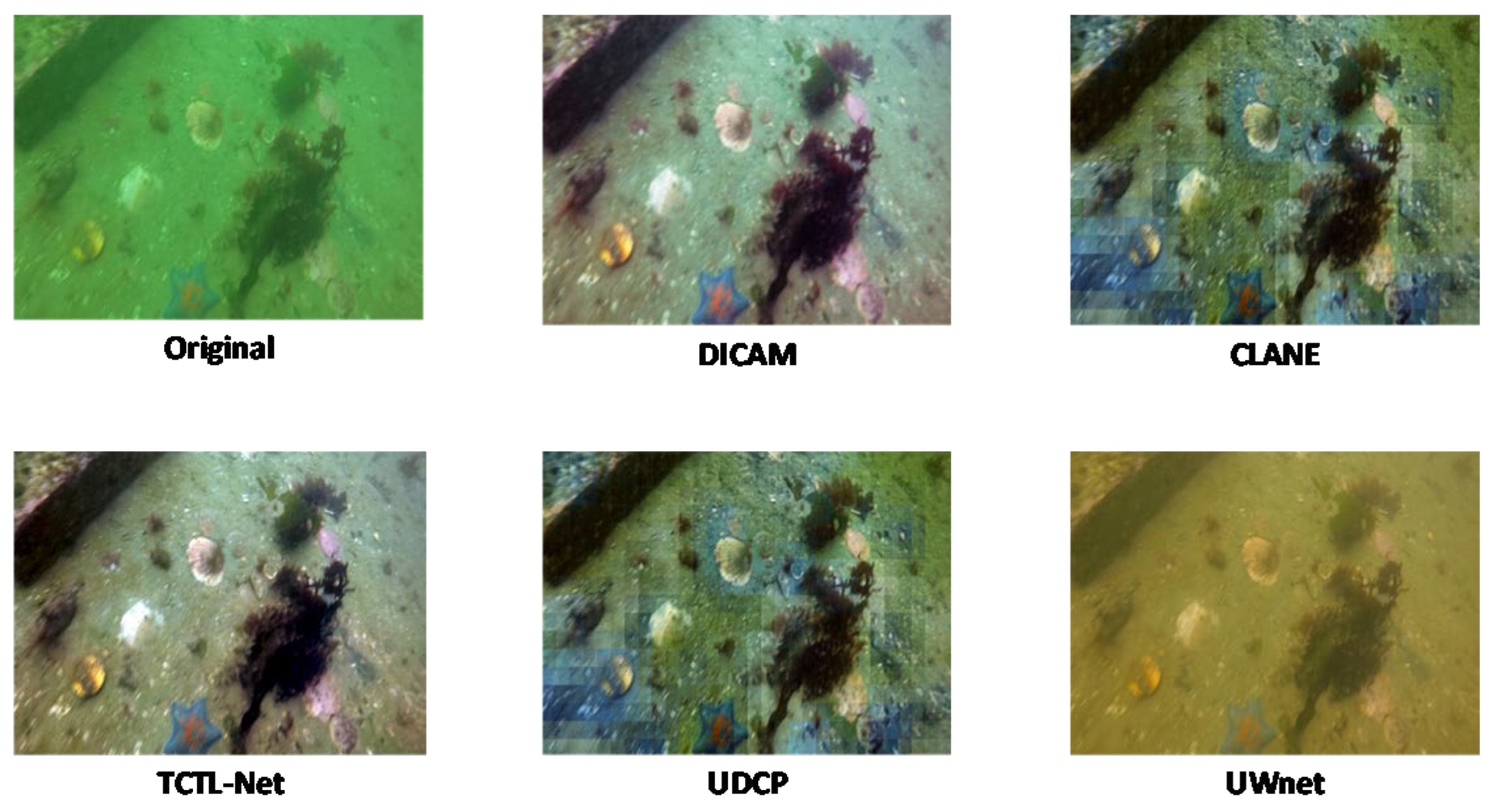

3.2.2. Multi-Stage Underwater Image Enhancement

Underwater images are often affected by absorption and scattering, which lead to color distortion, insufficient contrast, and blurred details. These degradations severely compromise the performance of subsequent detection tasks. To address this issue, we introduce a multi-stage enhancement module at the preprocessing stage, which integrates physics-based priors with deep learning strategies to recover color fidelity, improve contrast, and enhance structural textures, thereby improving the overall image quality.

The proposed enhancement method combines physical imaging priors with convolutional neural network architectures. A channel-level compensation mechanism is employed to restore attenuated color components, followed by contrast enhancement and multi-scale feature fusion to refine fine-grained structures. With end-to-end training support, the method achieves consistent improvements in color restoration, contrast adjustment, and texture enhancement.

Figure 9 illustrates the qualitative comparison of underwater enhancement methods across different representative approaches. The original image exhibits severe color bias, contrast suppression, and blurred target boundaries. CLAHE improves local contrast but amplifies background noise, leading to unnatural appearances. UDCP partially restores color but suffers from bluish over-correction under complex lighting. U-Net shows improved adaptability due to its deep learning capacity but introduces local distortions, with edge details remaining unclear. TCTL-Net further enhances color and contrast but suffers from edge artifacts and over-sharpening. In contrast, the proposed DICAM method achieves a natural balance, effectively suppressing greenish and bluish artifacts, recovering clear edges, and preserving local texture integrity.

Table 4 presents the quantitative evaluation of enhancement methods using UIQM, UCIQE, MSE_UIQM, and MSE_UCIQE. CLAHE achieved the highest UIQM improvement among traditional methods (3.42) but at the cost of unnatural artifacts. UDCP achieved the lowest MSE_UIQM (0.022), reflecting partial restoration but insufficient texture consistency. U-Net achieved balanced performance with UIQM = 3.56 and UCIQE = 0.641, though MSE_UIQM = 0.313 indicated deviations in local consistency. TCTL-Net further improved UCIQE (0.665) but exhibited a high MSE_UIQM (0.500), suggesting over-enhancement and edge distortion.

By comparison, the proposed DICAM method achieved the best performance, with UIQM = 3.85 and UCIQE = 0.673, confirming superior clarity, color fidelity, and overall perceptual quality. Although its MSE_UIQM (0.722) and MSE_UCIQE (0.0092) are relatively higher due to stronger pixel-level adjustments, this trade-off reflects its pursuit of natural visual realism while ensuring structural-texture consistency.

From the perspective of detection tasks, DICAM not only preserves pixel-level fidelity but also enhances discriminative features required by downstream detectors. This explains why incorporating DICAM-enhanced inputs consistently improves both mAP and robustness metrics in complex underwater detection scenarios.

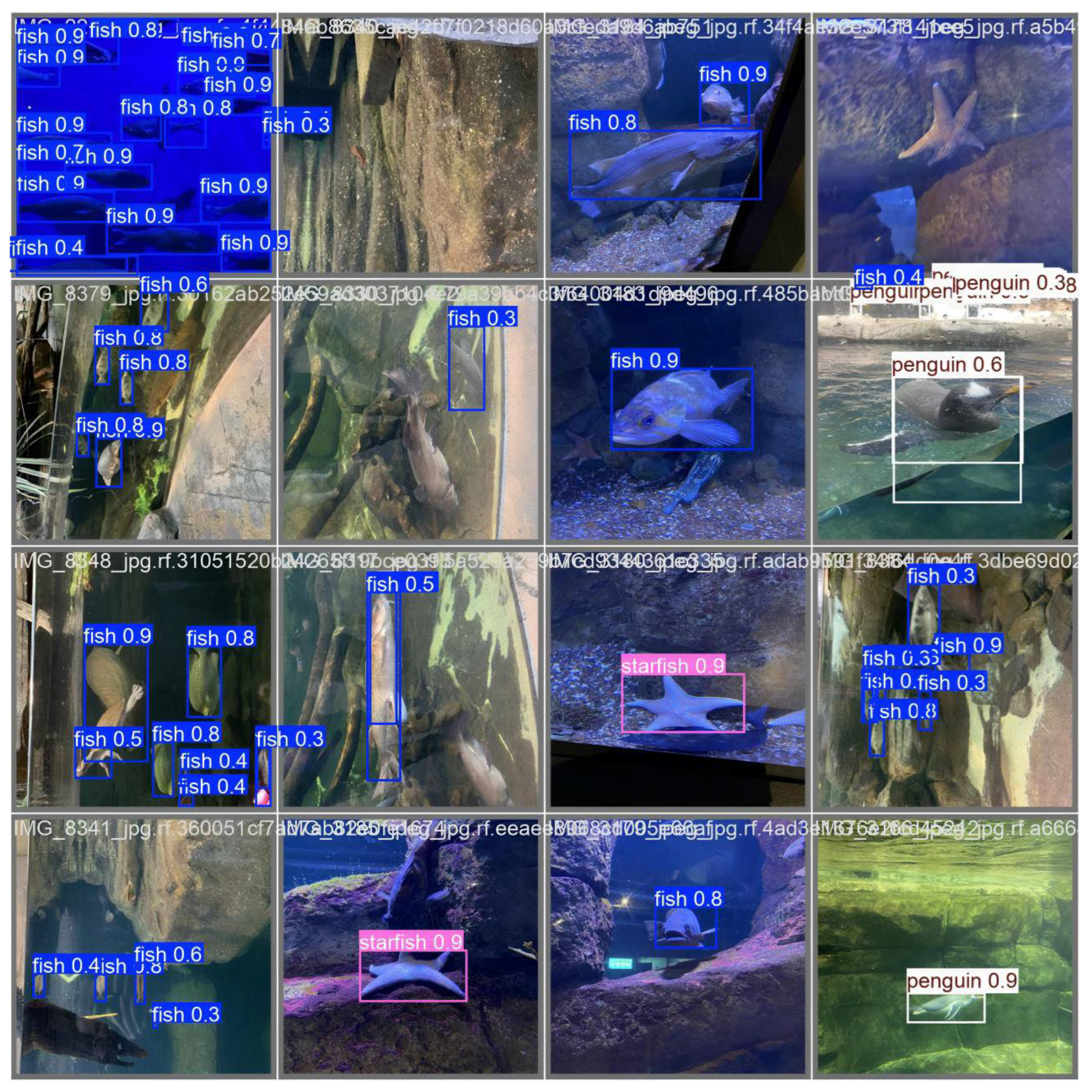

3.3. Visualization Analysis of YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN Detector

Figure 10 presents the visualization results of the improved YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN model in underwater object detection tasks. Overall, the model maintains stable detection performance under challenging conditions such as complex backgrounds, color distortions, and contrast degradation in underwater imagery. The model can accurately recognize multiple categories of underwater objects including fish, penguins, and starfish. The predicted bounding boxes align well with object contours, with confidence scores typically ranging from 0.7 to 0.9, demonstrating strong capability in both classification and localization. Particularly in densely populated fish scenarios, the model effectively distinguishes adjacent individuals while minimizing false positives and missed detections. This highlights the contribution of the introduced HSFPN module in enhancing multi-scale feature fusion, enabling robust detection across different object scales and complex scenes.

In terms of small object detection, YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN shows significant improvements. Even under long-range observation or partial occlusion, the model can still detect small fish or edge-region targets with high confidence. This can be attributed to the integration of the Coordinate Attention (CA) mechanism, which strengthens target-related feature representation by emphasizing informative channels while suppressing redundant background noise. Compared with the baseline YOLO detector, the improved architecture demonstrates stronger adaptability to underwater optical degradations such as color shifts, low contrast, and scattering blur, thereby achieving superior performance in recognizing small and weak-textured objects.

Additionally, the model exhibits promising generalization ability in atypical object detection. For instance, in the detection of penguins and starfish, the improved model consistently provides high-confidence predictions, indicating enhanced cross-category adaptability. Such robustness across multiple species is critical for real-world applications where underwater detection tasks are highly diverse.

In summary, the improved YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN demonstrates outstanding detection performance in complex underwater environments. It maintains high detection accuracy under optical degradations and noisy backgrounds, while significantly improving small-object recognition and multi-target discrimination. These results confirm the synergistic effects of the HSFPN and CA modules, which enhance multi-scale fusion and channel-wise discrimination. The robust detection capability provides a solid foundation for subsequent integration with A-ViT for dynamic inference and adversarial vulnerability analysis.

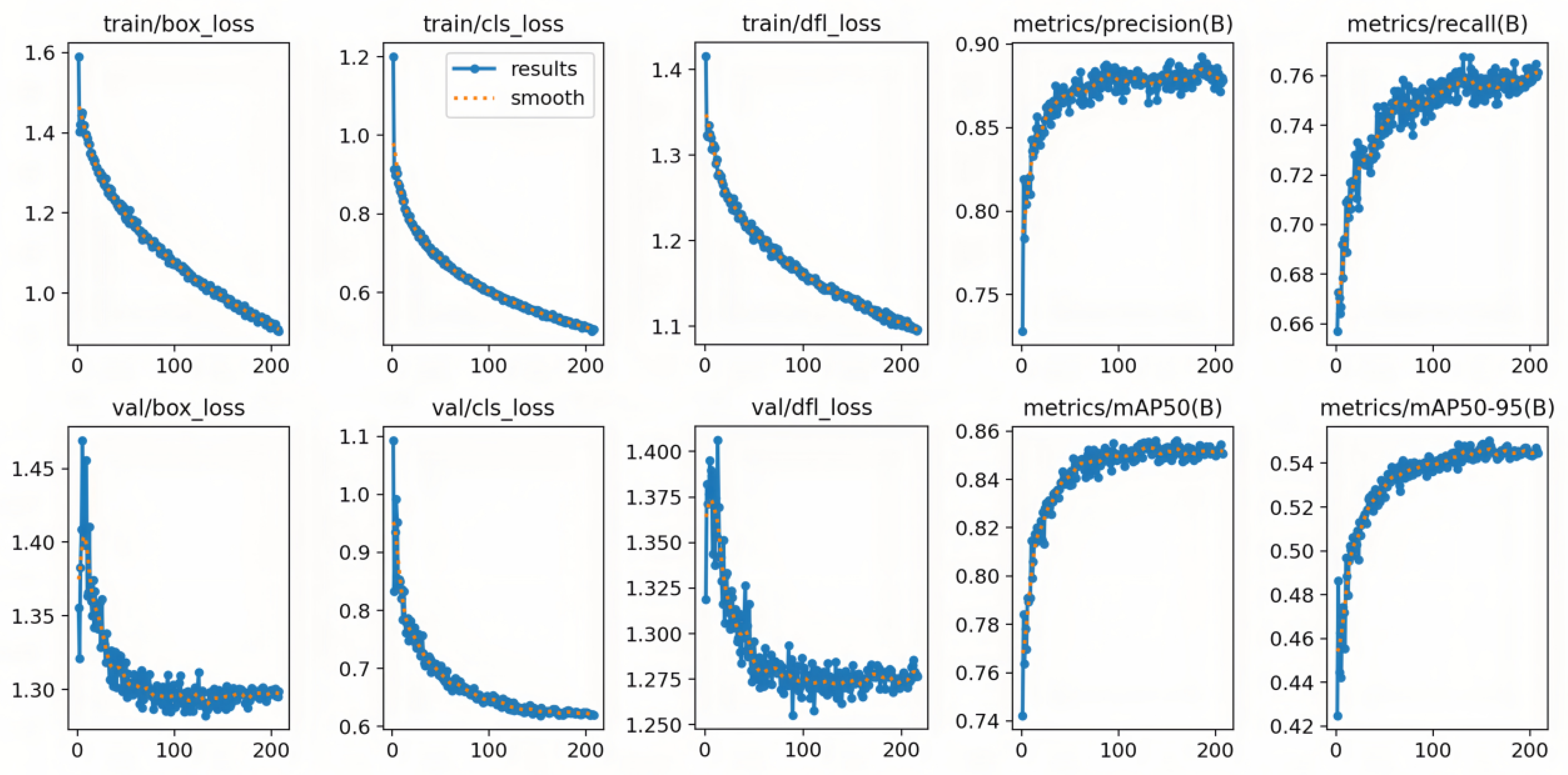

The visualization results confirm strong adaptability in real-world scenarios, while the convergence characteristics further validate the effectiveness of the structural modifications. As shown in

Figure 11, both training and validation losses (box, cls, and dfl) decrease monotonically and gradually converge with increasing iterations. Meanwhile, Precision, Recall, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95 steadily increase and stabilize, reflecting reliable optimization behavior.

The curves exhibit the following properties:

Stable Convergence: Validation box_loss and dfl_loss curves show minimal oscillations, indicating smooth convergence.

Synchronized Quality Improvement: Precision and Recall consistently improve, and the final mAP plateau suggests strong generalization ability.

Effectiveness of Structural Modifications: Compared with the baseline, the CA-HSFPN-enhanced model achieves higher plateaus across metrics, confirming stronger feature representation capacity.

To ensure reproducibility, the training configuration of the improved YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN is summarized in

Table 5. The configuration balances memory constraints with training speed and accuracy, following mainstream object detection practices.

This setup ensures efficient convergence and reliable detection performance, while providing clear reproducibility for future experiments.

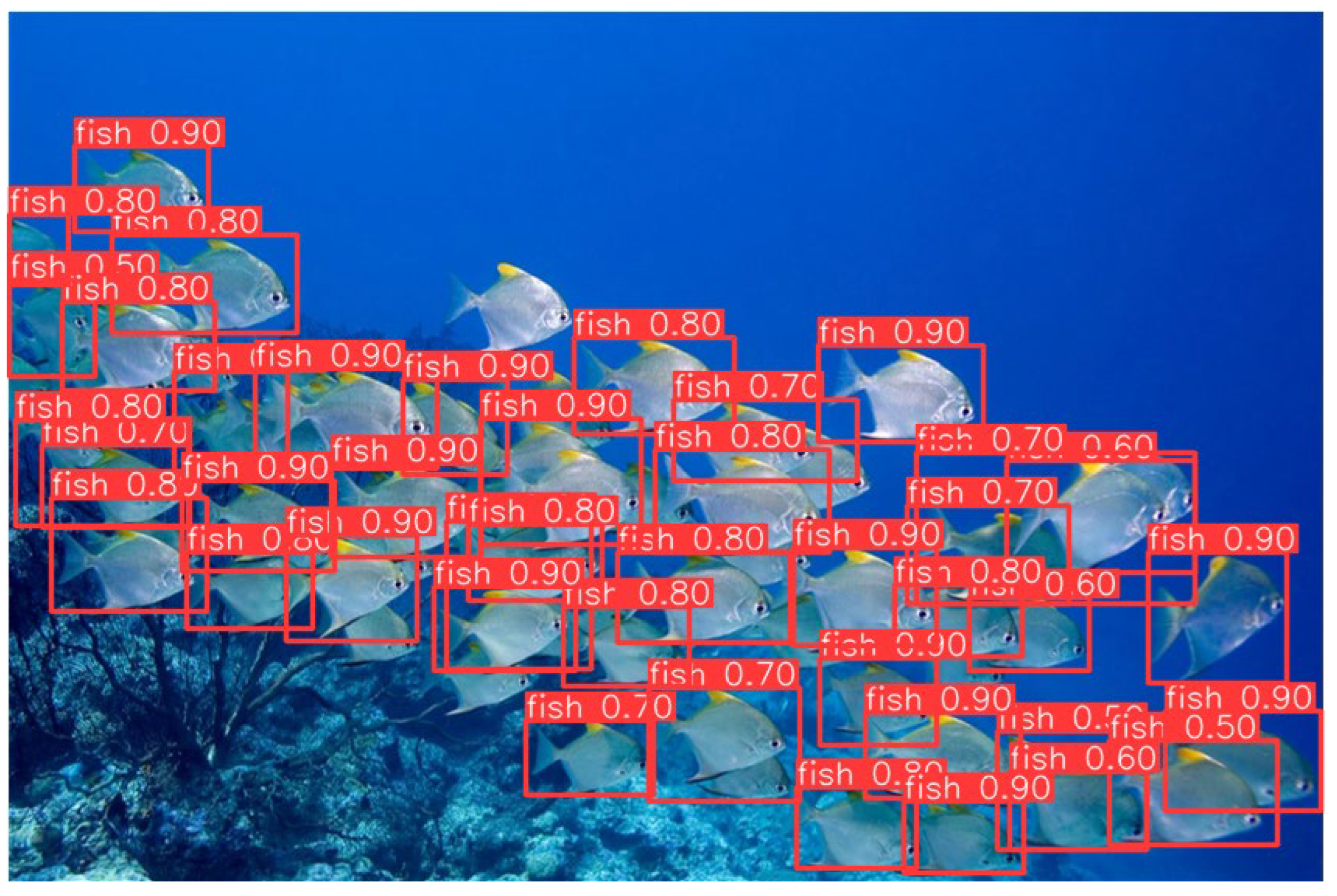

3.4. Visualization Analysis of Fish-School Detection Based on A-ViT

In underwater fish-school detection tasks, relying solely on numerical indicators such as mAP or Precision/Recall can reflect overall performance but often fails to reveal detailed behavior in complex scenarios. Particularly in underwater environments with densely distributed targets, uneven illumination, and significant background disturbances, intuitive visualization provides a clearer demonstration of differences in spatial localization, confidence stability, and robustness across models. Therefore, this study evaluates detection performance on real fish-school images using both unaltered raw inputs and A-ViT dynamically cropped inputs, aiming to visually validate the trade-off between efficiency and robustness introduced by the mechanism.

As shown in

Figure 12, under raw image input, YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN achieves complete and stable bounding-box coverage in dense fish distributions, with confidence scores largely concentrated within the 0.7–0.9 range. This indicates strong classification and localization capability, ensuring accuracy and consistency in detection. However, as shown in

Figure 13, when dynamic cropping by A-ViT is applied, most fish targets are still correctly identified, but the detection results exhibit redundancy: duplicate bounding boxes appear around fish edges, overlaps among boxes increase, and confidence distributions fluctuate more widely. This phenomenon suggests that A-ViT’s token pruning, while reducing redundant computation, inevitably disrupts spatial continuity, thereby introducing more redundant annotations at the detection output level.

It is noteworthy that this redundancy is not purely negative. First, in adversarial settings, perturbations often target background or boundary regions, while A-ViT’s dynamic cropping prioritizes the retention of target-relevant tokens. This ensures comprehensive target coverage, preventing critical missed detections. Consequently, even with redundant bounding boxes, the system maintains effective detection integrity. Second, in safety-critical applications such as autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) or long-range monitoring platforms, avoiding missed detections is often more important than reducing redundancy, as false negatives may directly cause mission failure or safety risks.

From a design perspective, the dynamic cropping of A-ViT complements the structural optimization of YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN. The former substantially reduces background computation, enhancing energy efficiency and inference speed, while the latter—through CA and HSFPN modules—improves discrimination of small and densely packed targets. This synergy enables the system to maintain high confidence despite the spatial discontinuities introduced by cropping. Future integration with advanced non-maximum suppression (NMS) strategies or temporal consistency mechanisms may further reduce redundancy, achieving a balanced trade-off among accuracy, efficiency, and adversarial robustness.

In conclusion, the experimental results highlight the dual role of A-ViT in underwater fish-school detection: on the one hand, its dynamic inference significantly lowers computational overhead and boosts energy efficiency; on the other hand, even with increased redundancy, the system retains complete target coverage and high robustness. These characteristics provide unique advantages for deployment in safety-critical underwater applications, demonstrating that A-ViT serves not only as an effective tool for efficiency optimization but also as a promising pathway to enhance adversarial robustness.

3.5. Dynamic Visualization Analysis and Adversarial Vulnerability Verification of A-ViT in Underwater Fish-School Detection

To further validate the effectiveness of the A-ViT dynamic inference mechanism proposed in

Section 2.4 under complex underwater environments, we conducted visualization experiments on real fish-school images. Underwater scenes often contain large homogeneous water regions and low-texture areas, which are redundantly processed by conventional Transformer frameworks, leading to substantial computational waste. In contrast, A-ViT applies a mathematically defined selection function that integrates attention weights and feature entropy, selectively retaining the most discriminative foreground tokens while discarding redundant background tokens, thereby reducing computational overhead.

As shown in

Figure 14, the left panel presents the raw input, where both fish schools and the surrounding background are fully fed into the network, whereas the right panel illustrates the A-ViT dynamic selection results, where the model focuses on fish-related tokens while cropping or downscaling large background regions. This visualization aligns with theoretical analysis: when the foreground ratio is rrr and the background shrinkage factor is sss, the effective processing area is reduced to approximately rA+(1−r)sArA + (1-r)sArA+(1−r)sA. In sparse-target scenarios, the effective processing area can be compressed to nearly half of the original, resulting in an almost linear reduction in both peak memory usage and FLOPs. Importantly, the preserved regions are concentrated on fish contours and texture details, consistent with the robustness index I(x)I(x)I(x), which favors tokens that remain stable under perturbations. This mechanism not only enhances attention to critical regions but also naturally weakens perturbation-prone background areas, thereby improving overall robustness.

From a system perspective, this adaptive property offers two key advantages:

Energy efficiency improvement — By reducing redundant background computation, A-ViT compresses the effective processing area to less than half, synchronously decreasing memory consumption and inference latency, thereby significantly improving deployability on embedded platforms.

Robustness enhancement — The discarded regions often coincide with locations where adversarial patches can be most effectively hidden, making the dynamic pruning mechanism inherently resistant to such perturbations while lowering energy costs.

In summary, these visualization results empirically confirm the theoretical advantages of A-ViT: its dynamic token selection mechanism not only reduces computational overhead for efficiency but also enhances discriminative robustness in adversarial underwater environments. This finding provides strong empirical support for the dual optimization of energy efficiency and robustness discussed in subsequent sections.

To further examine the impact of adversarial threats, we simulated attacks to evaluate the resilience of the proposed framework under potential hazards. Recent studies have shown that energy-oriented adversarial attacks targeting adaptive Vision Transformers can severely disrupt their dynamic inference mechanism, negating efficiency advantages. To this end, we adopted the SlowFormer attack as a representative scenario and conducted experiments on fish-school images to reveal its real-world risks in underwater contexts.

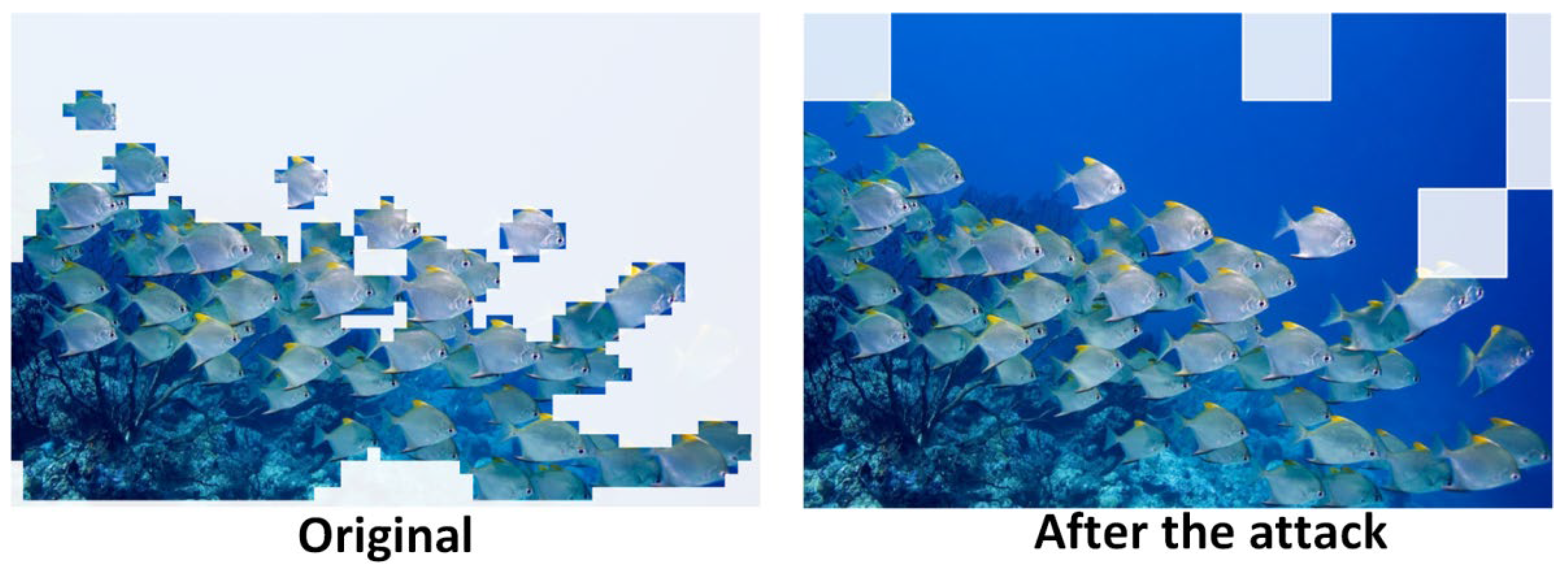

As shown in

Figure 15, after the attack, A-ViT’s token pruning mechanism is heavily disrupted. Normally, the model selectively focuses on fish-related regions while cropping large portions of the background for efficient inference. However, under the SlowFormer attack, the model is forced to retain redundant tokens across multiple areas, even within homogeneous water regions, leading to unnecessary computation. This indicates that the adversarial patch perturbs the halting distribution, delaying token exits and effectively reverting the model to a full ViT inference state.

Critically, this attack not only eliminates A-ViT’s efficiency advantage but also poses severe threats to system energy consumption and robustness. In our experiment, the pruning rate dropped significantly, computation surged, and the device’s power consumption increased nonlinearly, directly reducing endurance on resource-constrained underwater platforms. Meanwhile, excessive attention to background regions reduced the model’s discriminative capacity on fish targets, destabilizing confidence scores. In adversarial scenarios such as military underwater operations, such attacks could increase computational load, impair real-time response, and ultimately weaken mission performance.

These findings reveal the latent risks of energy-oriented adversarial attacks in underwater detection: attackers can undermine deployability without directly reducing detection accuracy, simply by manipulating the computational distribution of the model. This underscores not only the necessity of incorporating adversarial defenses into underwater intelligent perception frameworks but also the importance of achieving a deeper balance between efficiency optimization and adversarial robustness in future detection systems.

4. Discussion

4.1. Ablation Study of Image Processing Modules

In the ablation experiments on image processing modules, the impact of different preprocessing strategies on detection performance exhibits clear variations (see

Table 6). Introducing Color Restoration (CR) alone improves detection accuracy to a certain extent, with mAP@0.5 increasing by 0.6 percentage points. This is because underwater imaging is often affected by spectral attenuation and color distortions; CR helps restore the natural color distribution and local contrast of targets, thereby improving the quality of detector inputs. However, CR has limited ability to recover high-frequency details, which explains its relatively modest improvements.

By contrast, applying Super-Resolution (SR) based on HAT reconstruction leads to an mAP@0.5 of 55.5%, slightly higher than CR alone. This result indicates that high-resolution detail recovery contributes more significantly to detection, especially for small objects and fine-grained features. The SR module effectively reconstructs edge textures and subtle structures, reducing feature loss caused by blurring and insufficient resolution. This observation is consistent with existing literature, where deep learning-based super-resolution methods for underwater image enhancement emphasize the importance of detail recovery for improving detection accuracy [

37,

38,

39].

Furthermore, when CR and SR are combined, performance improves most significantly, with mAP@0.5 reaching 56.0%, representing a 1.3 percentage point gain over the baseline. This demonstrates their complementary roles: CR enhances global color fidelity and contrast, while SR focuses on local high-frequency detail reconstruction. Together, they compensate for both optical degradations and resolution deficiencies in underwater images, significantly improving input quality for the detector. This synergy aligns with the recent “multi-dimensional underwater enhancement” paradigm, which emphasizes addressing both color shift and texture degradation simultaneously to maximize downstream detection accuracy [

40,

41].

In addition, when combining CR+SR with the modified YOLO detector (YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN), overall performance further improves to 57.0%, while Precision and Recall rise to 0.892 and 0.760, respectively. This indicates that once input quality is improved by preprocessing, the optimized detector structure can more effectively exploit its feature extraction and discriminative capabilities. In other words, image quality enhancement and architectural optimization are not independent factors but mutually reinforcing in boosting detection performance.

From an application perspective, these findings hold substantial significance for underwater tasks. Since underwater environments often suffer from both optical degradation and resolution insufficiency, a single processing method is insufficient for comprehensive improvement. The synergy between CR and SR better adapts to such complex degradation conditions. Clearer and more natural inputs not only improve detection accuracy but also enhance robustness for weak-texture targets, small objects, and cluttered backgrounds—capabilities that are particularly critical for underwater defect inspection, long-range monitoring, and similar mission scenarios.

4.2. Performance Analysis and Ablation Study of YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN

To further validate the effectiveness of the proposed improvements, we systematically compared YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN with mainstream detectors, including YOLOv5, YOLOv7, YOLOv8, YOLOv10, YOLOv11, and the RT-DETR series. The results are summarized in

Table 7.

As shown in

Table 7, the YOLO series (v5–v11) demonstrates gradual improvements in Precision, Recall, and mAP@0.5 with each iteration, with YOLOv10 and YOLOv11 showing significant enhancements compared to earlier versions. This indicates progressive adaptations in feature representation, structural optimization, and training strategies to handle complex environments. However, the performance gains across YOLOv5 to YOLOv11 remain limited, with mAP@0.5 improving only from 52.6% to 54.7% (an increase of less than 2.5 percentage points), suggesting that conventional convolution-based detectors face performance bottlenecks in underwater tasks, particularly under optical degradation and small-object scenarios.

By contrast, the RT-DETR series, benefiting from its Transformer architecture, shows stronger potential in global modeling and feature interaction. RT-DETR v1-R50 outperforms YOLOv11 in Recall (0.741) and mAP@0.5 (55.0%), while v2-R50 further improves to 0.749 and 55.9%, respectively. This demonstrates that self-attention mechanisms are more effective in capturing long-range dependencies and multi-object interactions in complex underwater backgrounds. However, their inference latency (12.6–14.8 ms) is considerably higher than that of YOLO models, reflecting the trade-off between accuracy and efficiency in Transformer-based architectures: improved global modeling leads to higher accuracy but at the cost of slower inference.

On this basis, the improved YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN achieves superior overall performance. With Precision of 0.889, Recall of 0.754, and mAP@0.5 of 56.2%, it surpasses both YOLO and RT-DETR counterparts. Meanwhile, its latency is only 10.5 ms, comparable to YOLOv11 and significantly lower than RT-DETR v1/v2. These results indicate that YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN achieves an accuracy breakthrough while maintaining real-time efficiency. Its advantages stem mainly from:

HSFPN — which improves multi-scale feature fusion, alleviating difficulties caused by diverse target sizes in underwater environments;

CA module — which enhances channel-wise discriminability, allowing the model to highlight task-relevant features and suppress background noise.

Together, these improvements address the limitations of convolutional models in representing features under complex underwater conditions.

From an application perspective, the performance differences among models carry practical implications. For tasks with strict real-time requirements (e.g., online underwater robot inspection or rapid pipeline defect detection), YOLO models are more advantageous due to their lower latency. For tasks demanding maximum accuracy (e.g., monitoring small marine organisms or detecting long-range targets), RT-DETR, despite higher latency, provides more robust feature modeling. YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN finds a balanced middle ground—offering YOLO-like real-time speed while surpassing RT-DETR in accuracy—making it particularly suitable for real-time, high-accuracy detection in complex underwater environments.

The ablation study in

Table 8 reveals the contributions of the individual modules. Adding HSFPN alone improves mAP@0.5 by 0.9 percentage points, primarily due to its enhanced multi-scale semantic feature fusion, which alleviates the insufficient feature representation of conventional FPNs in complex backgrounds. Adding CA alone increases mAP@0.5 by 1.1 percentage points, demonstrating that channel attention effectively highlights discriminative features in target regions while suppressing redundant and noisy information.

When both HSFPN and CA are combined, performance improves most significantly, with mAP@0.5 reaching 56.2%—a 1.5 percentage point increase over the baseline—alongside simultaneous gains in Precision and Recall. This synergy indicates complementary effects: HSFPN enhances multi-scale fusion, while CA strengthens channel discrimination, together achieving a balance between global semantics and local discriminability. This observation aligns with recent studies advocating “joint optimization of attention and feature pyramids” [

42,

43,

44] and further validates its effectiveness in complex underwater environments.

It is noteworthy that the inference latency of YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN is only slightly higher than the baseline YOLOv11 (10.5 ms vs. 10.2 ms), indicating that performance improvements are achieved with negligible computational overhead. This accuracy-efficiency trade-off is particularly critical for underwater applications, where detectors are often deployed on resource-limited edge devices or robotic platforms. Ensuring real-time performance while improving accuracy significantly enhances practical usability.

In summary, YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN, by integrating HSFPN and CA modules, achieves synergistic optimization of multi-scale feature fusion and channel attention, delivering superior detection accuracy and robustness in complex underwater scenarios. With its controlled latency and strong real-time capability, this architecture demonstrates high application potential for underwater small-object detection and defect inspection tasks.

4.3. Experimental Analysis of the A-ViT+ROI Dynamic Inference Mechanism

To evaluate the energy–efficiency performance of A-ViT+ROI dynamic inference under varying foreground ratios (FR), we conducted systematic experiments on three representative detectors: YOLOv8, YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN, and RT-DETR-R50 (see

Table 9). Overall, A-ViT demonstrates significant reductions in inference latency and memory usage under low-to-moderate foreground ratios (FR ≈ 0.2–0.4). For example, with YOLOv8 at FR = 0.23, the latency decreased to 7.18 ms, representing a 34.7% reduction compared to the baseline, while memory usage dropped to 0.55 GB, a reduction of 75.0%. Similar patterns were observed with YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN and RT-DETR-R50, achieving latency reductions of 27.3% and 48.9%, and memory savings of 74.6% and 80.0%, respectively, at FR ≈ 0.24 and 0.18. These results indicate that the dynamic token pruning mechanism of A-ViT is particularly effective in sparse-target scenarios, where redundant computations can be avoided, thereby improving real-time performance and hardware efficiency.

However, as the foreground ratio increases (FR ≈ 0.6), the efficiency advantage of A-ViT diminishes or even reverses. For example, with YOLOv8 at FR = 0.62, latency rises to 12.38 ms, an increase of 12.5% over the baseline, while memory usage grows to 2.31 GB. Similar phenomena are observed for YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN (FR ≈ 0.59) and RT-DETR-R50 (FR ≈ 0.65), with latency increases of 6.6% and 3.2%, respectively, memory consumption increasing by about 5%, and fallback mechanisms triggered (Fallback = TRUE). This suggests that in dense-target scenarios, A-ViT must retain more tokens to avoid missed detections, rendering dynamic pruning ineffective and inference close to full computation. Consequently, efficiency gains are lost, and negative growth occurs—consistent with recent findings on dynamic inference, which highlight its superiority under sparsity but inevitable degradation under high-density conditions [

45,

46,

47].

Differences among detectors further reveal architectural characteristics. RT-DETR-R50 achieves the most substantial efficiency gains under low FR, reducing latency by 48.9% and memory by 80.0% at FR = 0.18, reflecting the strong optimization potential of Transformer-based architectures when combined with A-ViT. However, its efficiency also degrades more sharply as FR increases, highlighting its sensitivity to dense target distributions. By contrast, YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN maintains more balanced stability, still achieving a 19.0% latency reduction and 58.9% memory saving at FR ≈ 0.44, showing greater resilience in medium-density conditions. These differences imply that the effectiveness of A-ViT depends not only on foreground ratios but also on the detector’s feature modeling strategy: convolutional architectures demonstrate stability at moderate densities, while Transformers show stronger gains in sparse scenarios.

It should be noted that the FR values for different detectors are not perfectly aligned: FR = 0.23 for YOLOv8, 0.24 for YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN, and 0.18 for RT-DETR-R50. This discrepancy arises from structural differences that affect saliency partitioning. Variations in receptive fields, attention distributions, and feature sensitivities between convolutional and Transformer architectures naturally lead to slight shifts in foreground estimation. Such differences are expected in dynamic inference across architectures and do not affect the overall observed trend.

From an application perspective, these results indicate that A-ViT significantly enhances energy efficiency in underwater tasks with sparse or moderately dense foregrounds, such as long-range monitoring, underwater pipeline inspection, or sparse marine life recognition. However, in dense-target scenarios, such as fish schools or complex seabed topography, the advantages diminish and may even reverse due to fallback-induced overhead. Future research should therefore focus on enhancing the robustness of dynamic pruning in high-density scenarios—for example, through more stable saliency evaluation, multi-scale dynamic scheduling strategies, or hybrid token-retention mechanisms—to ensure efficiency gains remain consistent across diverse application conditions.

4.4. Energy–Efficiency Vulnerability of A-ViT+ROI under Adversarial Attacks

In adversarial experiments (see

Table 10), the energy–efficiency performance of A-ViT+ROI degraded severely, with inference latency and memory consumption increasing across all foreground ratios, and fallback mechanisms being universally triggered. This sharply contrasts with normal conditions, where low-to-moderate foreground ratios (FR ≈ 0.2–0.4) yield significant computational savings. Under attack, however, even at low sparsity levels (FR = 0.18 or 0.23), latency and memory usage increased by 15–20%, indicating that the dynamic inference advantage was entirely nullified. In other words, adversarial perturbations undermine A-ViT’s sparsity adaptation, forcing it to revert to near full-scale computation under all conditions.

More critically, the universal triggering of Fallback = TRUE indicates that attacks not only increase resource consumption but also directly disable A-ViT’s dynamic pruning mechanism. The core strength of A-ViT lies in selectively retaining salient tokens to reduce redundant computation while maintaining accuracy. However, adversarial perturbations shift saliency distributions, misleading the model into marking large background regions as “high-saliency.” Consequently, nearly all tokens are retained, forcing full-image inference. This systemic failure highlights the essence of the attack: not degrading detection accuracy directly, but undermining efficiency by collapsing the pruning logic, thereby inflating energy costs across all scenarios.

Performance differences across detectors further reveal architectural vulnerabilities. For YOLOv8 and YOLOv11-CA_HSFPN, latency and memory usage in low-FR conditions increased by 15–18% and 10–15%, respectively. In contrast, RT-DETR-R50 suffered the most, with latency consistently exceeding 16 ms and memory usage approaching 4 GB, indicating the largest efficiency loss. This suggests that Transformer-based architectures are more susceptible to amplification effects under energy-oriented attacks. Their global modeling characteristics make them prone to large-scale misclassification of background tokens as “critical regions,” magnifying resource overhead. In comparison, YOLO-based models also lost sparsity advantages under attack but exhibited smaller absolute increases in resource usage, suggesting that convolutional structures maintain relatively more stability when dynamic inference is compromised.

Mechanistically, this vulnerability stems from A-ViT’s heavy reliance on saliency estimation. Current A-ViT implementations often depend on attention weights or entropy measures to determine token importance, both of which are highly sensitive to adversarial perturbations. Prior studies confirm similar limitations: DynamicViT [

48] exhibits performance drops in dense scenarios, Token Merging [

49] suffers from robustness issues in complex distributions, and SlowFormer [

50] reveals a fundamental tension between efficiency optimization and adversarial robustness. Collectively, these findings support our results—while dynamic inference excels in sparse conditions, it inevitably degrades or fails under adversarial environments or dense-target scenarios.

From an application perspective, this efficiency vulnerability is particularly dangerous in underwater missions. For long-duration robotic cruises or continuous unmanned platform monitoring, endurance heavily depends on inference efficiency. Once subjected to energy-oriented attacks, systems face not only reduced detection accuracy but also sharp increases in power consumption, shortening mission duration and risking outright task failure. Unlike conventional accuracy-oriented attacks, energy attacks are more insidious, as their primary damage lies in resource exhaustion—posing direct threats to mission sustainability and platform safety.

Therefore, our findings underscore a critical conclusion: A-ViT loses all efficiency advantages under adversarial conditions, making dynamic inference a new point of fragility. Future optimization should focus on enhancing the robustness of saliency estimation to prevent global failures caused by perturbations. Potential strategies include multi-scale consistency validation, redundant token-decision pathways, adversarial training, or saliency-constrained regularization. Moreover, hybrid inference strategies should be explored, enabling models to retain partial pruning capabilities under abnormal saliency distributions, thus avoiding complete regression to full-image inference.

4.5. Defense Strategy: Image-Stage Quick Defense via IAQ