Submitted:

15 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

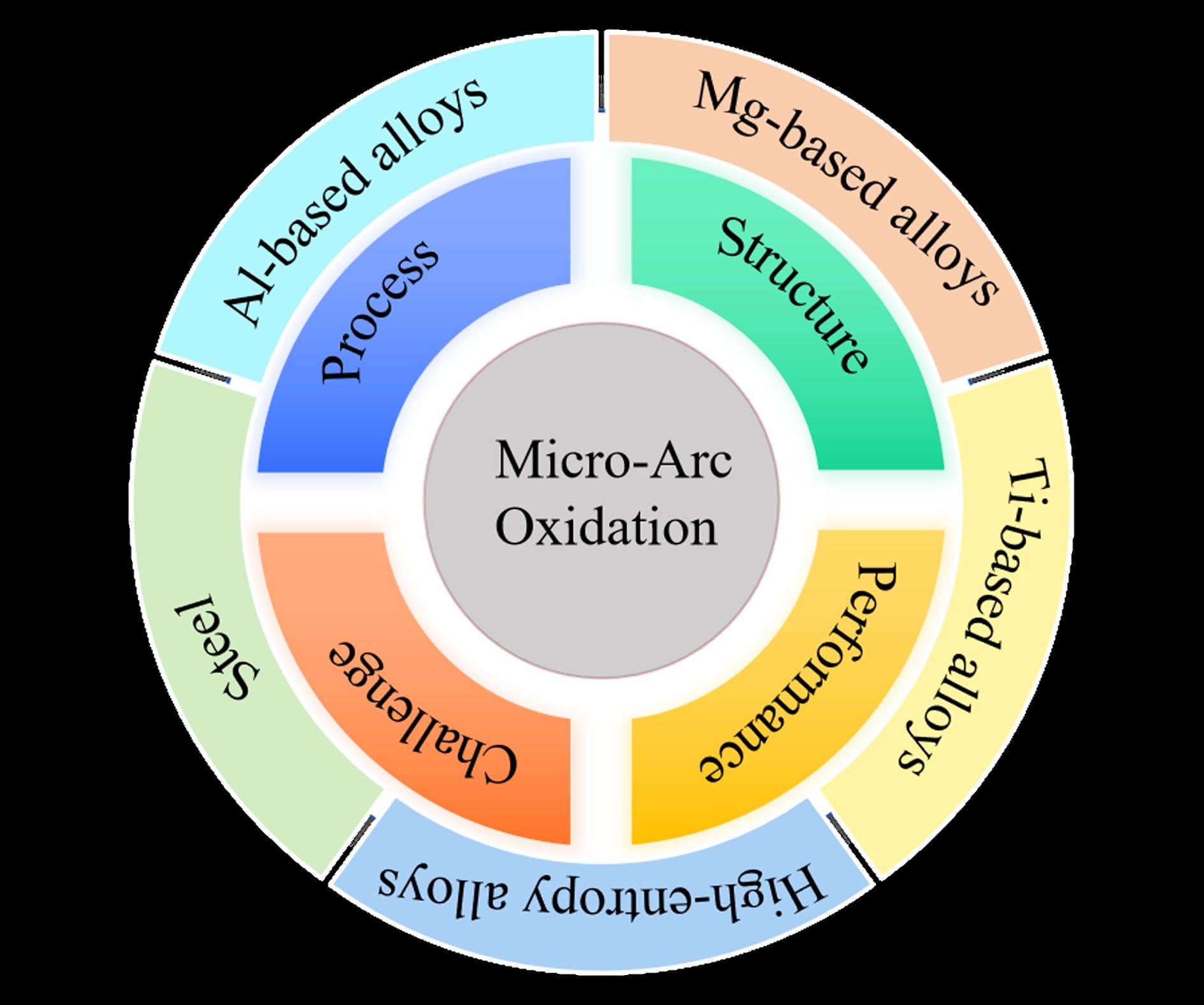

Abstract

Keywords:

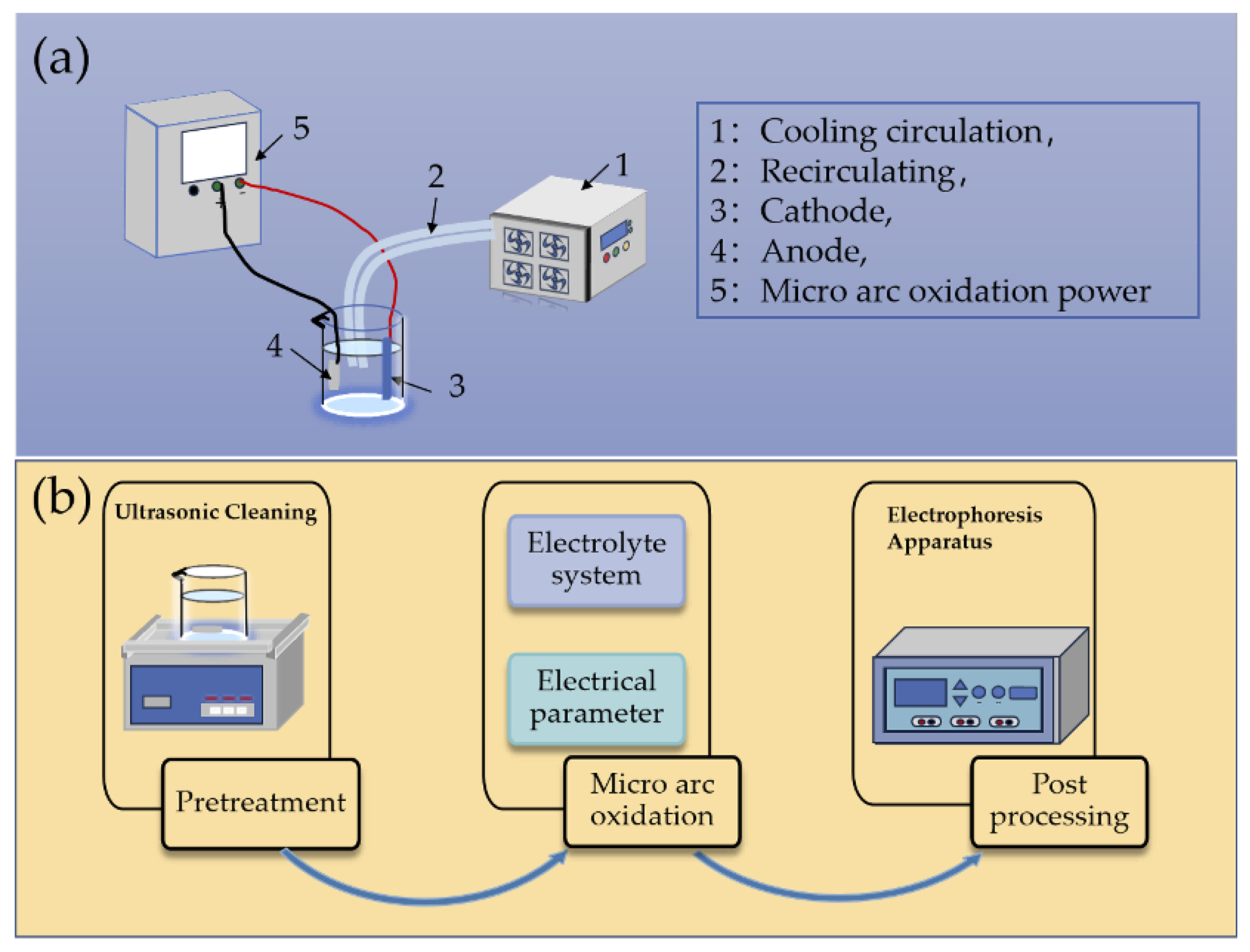

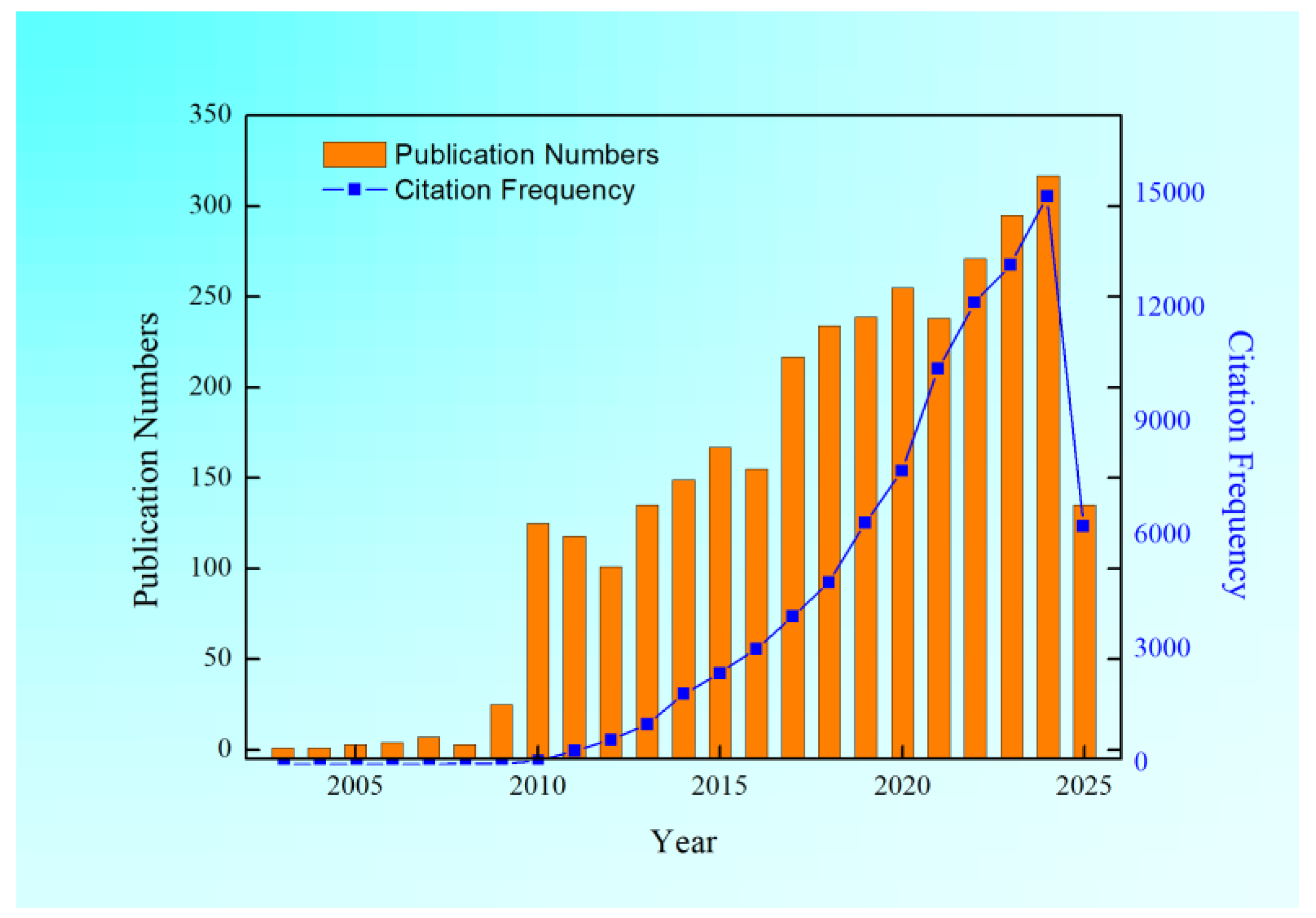

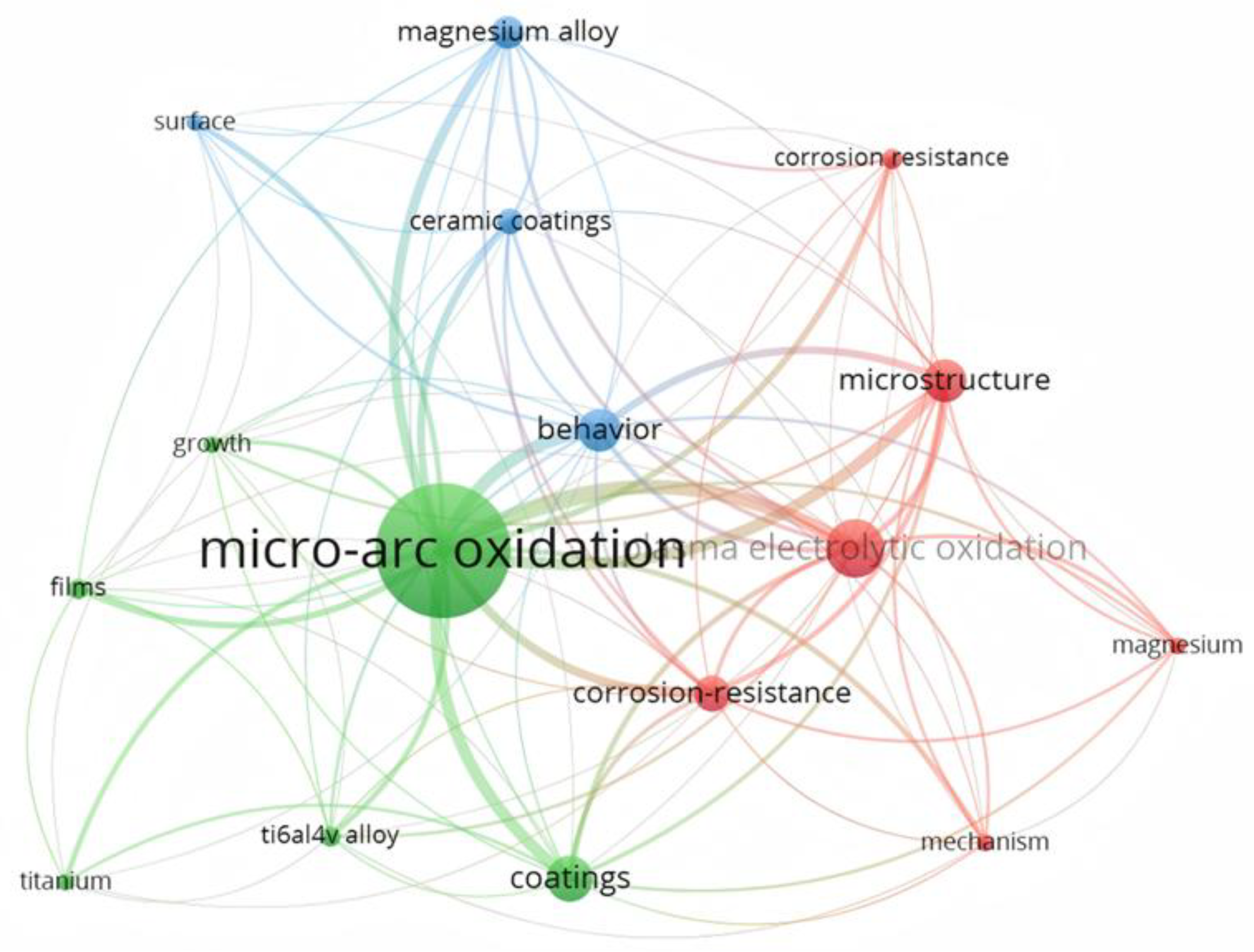

1. Introduction

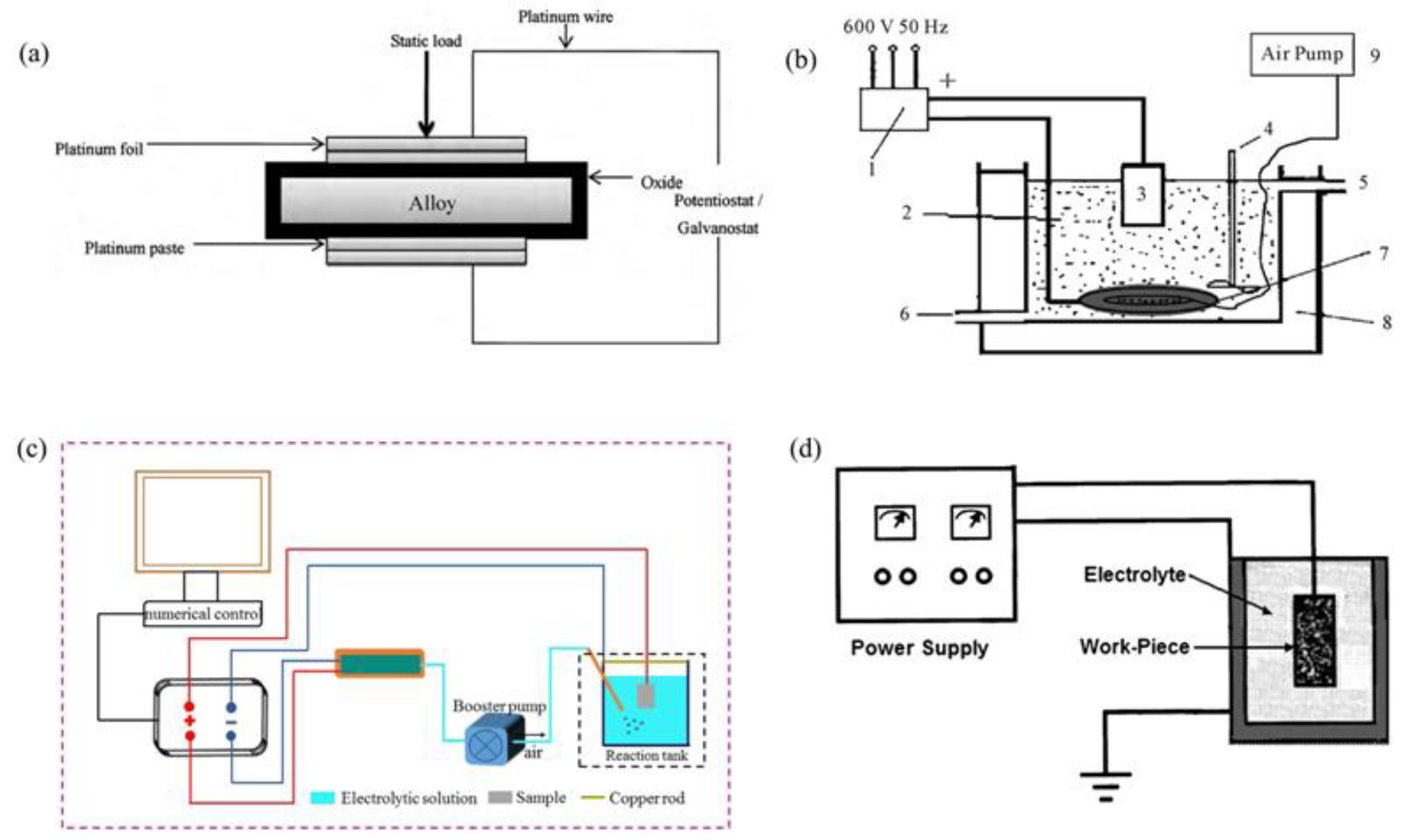

2. MAO Treatment Technology for Various Metallic Materials

2.1. MAO Treatment Technology for Al-Based Alloys

2.2. MAO Treatment Technology for Mg-Based Alloys

2.3. MAO Treatment Technology for Ti-Based Alloys

2.4. MAO Treatment Technology for High-Entropy Alloys

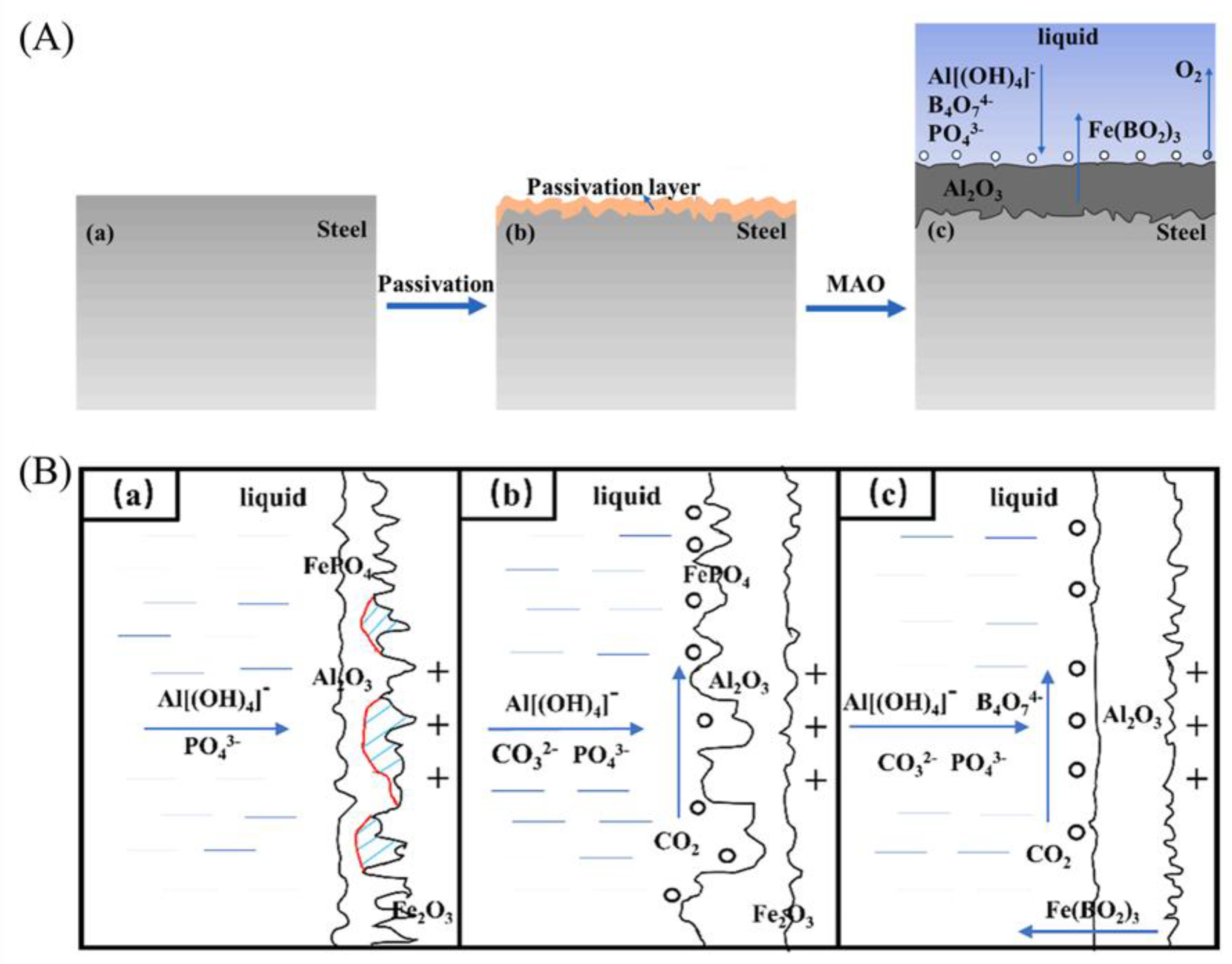

2.5. MAO Treatment Technology for Steel

3. Summary and Outlook

3.1. Summary

3.2. Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Golubkov, P.E.; Pecherskaya, E.A.; Artamonov, D.V.; Zinchenko, T.O.; Gerasimova, Y.E.; Rozenberg, N.V. Electrophysical model of the micro-arc oxidation process. Russ. Phys. J., 2020, 62, 2137-2144. [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.B.; Zhang, C.; Yue, H.T.; Li, Q.; Guo, C.G.; Zhang, J.Z.; Zhao, G.C.; Yang, X.L. A review on the fatigue performance of micro-arc oxidation coated Al alloys with micro-defects and residual stress. J. Mater. Res. Technol., 2023, 25, 4554-4581. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wang, T.; Yu, X.; Sun, X.; Yang, H. Functionalization treatment of micro-arc oxidation coatings on magnesium alloys: A review. J. Alloy. Compd., 2021, 879, 160453. [CrossRef]

- Ming, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Micro-arc oxidation in titanium and its alloys: Development and potential of implants. Coatings, 2023, 13(12), 2064. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, R. F.; Kuroda, P. A.; de Almeida, G. S.; Zambuzzi, W. F.; Grandini, C. R.; Afonso, C. R. New MAO coatings on multiprincipal equimassic β TiNbTaZr and TiNbTaZrMo alloys. BME Adv., 2025, 9, 100139. [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Luo, Z.; Qi, S.; Sun, X. Structure and antiwear behavior of micro-arc oxidized coatings on aluminum alloy. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2002, 154(1), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.P.; Du, K.Q.; Yan, C.W.; Wang, F.H. Electrochemical corrosion behavior of composite coatings of sealed MAO film on magnesium alloy AZ91D. Electrochim. Acta, 2006, 51(14), 2898-2908. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.T.; Jiang, Z.H.; Yao, Z.P.; Zhang, X.L. The effects of anodic and cathodic processes on the characteristics of ceramic coatings formed on titanium alloy through the MAO coating technology. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2005, 252(2), 441-447. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Du, C.; Tao, S.Y.; Chang, Y.Q.; Nie, Z.H.; Wang, Z.; Lu, H.L. Study on the effect and growth mechanism of micro-arc oxidation coating on AlCoCrFeNi high entropy alloy. J. Alloy. Compd., 2025, 1020, 179469. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.P.; Zhou, L.; Li, C.J.; Li, Z.X.; Li, H.Z.; Yang, L.J. Micrographic properties of composite coatings prepared on TA2 substrate by hot-dipping in Al-Si alloy and using micro-arc oxidation technologies (MAO). Coatings, 2020, 10(4), 374. [CrossRef]

- Kumruoglu, L.C.; Ustel, F.; Ozel, A.; Mimaroglu, A. Micro arc oxidation of wire arc sprayed Al-Mg6, Al-Si12, Al coatings on low alloyed steel. Engineering-PRC, 2011, 3(7), 680-690. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Song, R.G.; Kong, D.J. Microstructure and corrosion behaviours of composite coatings on S355 offshore steel prepared by laser cladding combined with micro-arc oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2019, 497, 143703. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Sun, Z.M.; Wang, C.Y.; Huang, A.H.; Ye, Z.S.; Ying, T.; Zhou, L.P.; Xiao, S.; Chu, P.K.; Zeng, X.Q. A self-sealing and self-healing MAO corrosion-resistant coating on aluminum alloy by in situ growth of CePO4/Al2O3. Corros. Sci., 2025, 245, 112706. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gu, Y.; Geng, Y.; Liang, J.; Zhao, J.; Kang, J. Investigating local corrosion behavior and mechanism of MAO coated 7075 aluminum alloy. J. Alloy. Compd., 2020, 826, 153976. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhu, L.; Liu, H.; Li, W. Investigation of MAO coating growth mechanism on aluminum alloy by two-step oxidation method. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2014, 293, 12-17. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C. C.; Lee, J. L.; Kuo, T. H.; Kuo, S. N.; Tseng, K. H. The influence of sodium tungstate concentration and anodizing conditions on microarc oxidation (MAO) coatings for aluminum alloy. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2012, 206(16), 3437-3443. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, S.; Huang, H.; He, M.; Wangyang, P.; Gu, L. Effect of micro-groove on microstructure and performance of MAO ceramic coating fabricated on the surface of aluminum alloy. J. Alloy. Compd., 2019, 777, 94-101. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wei, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, J. Influence of surface micro grooving pretreatment on MAO process of aluminum alloy. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2016, 389, 1175-1181. [CrossRef]

- Shehadeh, L.; Mohamed, K.; Al-Qawabeha, U.; Abu-Jdayil, B. The Role of Copper Incorporation in Improving the Electrical Insulation Properties of Microarc Oxidation Coatings on Aluminum Alloys. Eng. Sci., 2025, 33, 1380. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, J.; Ma, C.; Zhao, G. Analysis of frictional performance of microarc oxidized aluminum alloys in various media: Integration of experimental and MD simulation approaches. Mater. Today. Commun., 2025, 46, 112528. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J. H.; Cui, Y. W.; Shang, Y. Y.; Lu, L. H.; Du, R. W.; Zhu, M. Investigation of third harmonic laser-induced damage on micro-arc oxidized and composite-coated aluminum alloy 7075. J. Alloy. Compd., 2025, 1032, 181087. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D. L.; Jiang, B.; Qi, X.; Wang, C.; Song, R. G. Effect of current density on microstructure, mechanical behavior and corrosion resistance of black MAO coating on 6063 aluminum alloy. Mater. Chem. Phys., 2024, 326, 129800. [CrossRef]

- Long, B. H.; Wu, H. H.; Long, B. Y.; Wang, J. B.; Wang, N. D.; Lü, X. Y.; Jin, Z.S.; Bai, Y. Z. Characteristics of electric parameters in aluminium alloy MAO coating process. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys., 2005, 38(18), 3491. [CrossRef]

- Li, H. X.; Li, W. J.; Song, R. G.; Ji, Z. G. Effects of different current densities on properties of MAO coatings embedded with and without α-Al2O3 nanoadditives. Mater.Sci. Tech.-Lond, 2012, 28(5), 565-568. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.L.; Lü, X.Y.; Bai, Y.Z.; Cui, H.F.; Jin, Z.S. The effects of current density on the phase composition and microstructure properties of micro-arc oxidation coating. J. Alloy. Compd., 2002, 345(1-2), 196-200. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, T.; Xiao, Y.T.; Zhang, L.; Pu, J.; Cao, W.J.; Zhong, X.M. Characterization of micro-arc oxidation coatings on aluminum drillpipes at different current density. Vacuum, 2017, 142, 21-28. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Du, M.H.; Han, F.Z.; Yang, J. Effects of the ratio of anodic and cathodic currents on the characteristics of micro-arc oxidation ceramic coatings on Al alloys. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2014, 292, 658-664. [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.P.; Kuo, Y.C.; Sun, J.K.; He, J.L.; Chin, T.S. High quality oxide-layers on Al-alloy by micro-arc oxidation using hybrid voltages. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2016, 303, 61-67. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Li, X.G.; Li, Y.; Dong, C.F.; Tian, H.P.; Wang, S.X.; Zhao, Q. Growth mechanism of micro-arc oxidation film on 6061 aluminum alloy. Mater. Res. Express, 2019, 6(6), 066404. [CrossRef]

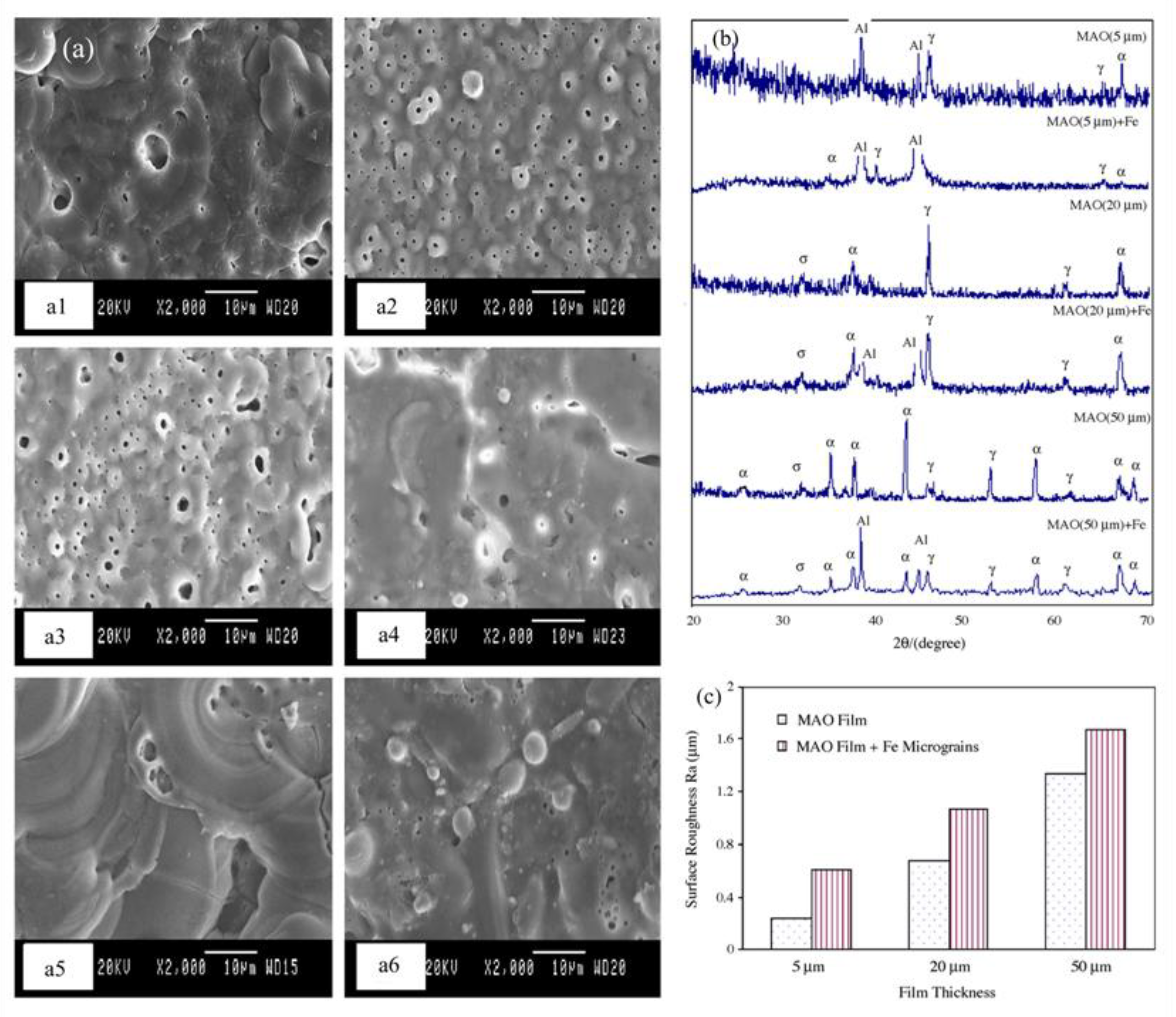

- Jin. F.Y.; Chu, P.K.; Tong, H.H., Zhao, J. Improvement of surface porosity and properties of alumina films by incorporation of Fe micrograins in micro-arc oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2006, 253(2), 863-868. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.P.; Qian, Z.Y.; Liu, X.H.; Zhu, L.Q.; Liu, H.C. Investigation of micro-arc oxidation coating growth patterns of aluminum alloy by two-step oxidation method. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2015, 356, 581-586. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.Z.; Jiang, Z.Q.; Tang, S.G.; Dong, W.B.; Tong, Q.; Li, W.Z. Influence of graphene particles on the micro-arc oxidation behaviors of 6063 aluminum alloy and the coating properties. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2017, 423, 939-950. [CrossRef]

- Arslan, E.; Totik, Y.; Demirci, E.E.; Vangolu, Y.; Alsaran, A.; Efeoglu, I. High temperature wear behavior of aluminum oxide layers produced by AC micro arc oxidation. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2009, 204(6-7), 829-833. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Y.; Cai, Z.B.; Cui, Y.; Liu, J.H.; Zhu, M.H. Effect of oxidation time on the impact wear of micro-arc oxidation coating on aluminum alloy. Wear, 2019, 426, 285-295. [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, A.; Panda, R.; Manwatkar, S.; Sreekumar, K.; Krishna, L. R.; Sundararajan, G. Effect of micro arc oxidation treatment on localized corrosion behaviour of AA7075 aluminum alloy in 3.5% NaCl solution. T. Nonferr. Metal. Soc., 2012, 22(3), 700-710. [CrossRef]

- Xin, S.G.; Song, L.X.; Zhao, R.G.; Hu, X.F. Properties of aluminium oxide coating on aluminium alloy produced by micro-arc oxidation. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2005, 199(2-3), 184-188. [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.F.; Li, Z.P.; Zhao, X.R.; Wang, Z.Y.; Sun, S.N.; Yang, Y.H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, S.Y.; Ren, S.T.; Kou, R.H. Growth mechanism and product formation of Micro-arc oxide film layers on aluminum matrix composites: An analytical experimental and computational simulation study. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2025, 684, 161968. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.H.; Lu, H.L.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Li, S.B. Influence of ultrasonic power modulation on the optimisation of aluminium alloy micro-arc oxidation coating properties. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2025, 679, 161067. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.Q.; Lu, H.L.; Shen, T.J.; Wang, Z.Z.; Xu, G.S.; Liu, Z.H.; Yang, H. Performance study of scanning micro-arc oxidation ceramic coatings on aluminum alloys based on different electrolyte flow rates. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2025, 496, 131686. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.Q.; Li, S.B.; Xue, Z.C.; Liu, Z.H.; Tu, N.; Lu, H.L. Performance evaluation of scanning micro-arc oxidation ceramic coating on aluminum alloy under different current working modes. Mater. Chem. Phys., 2025, 336, 130538. [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, T. S.; Park, I. S.; Lee, M. H. Strategies to improve the corrosion resistance of microarc oxidation (MAO) coated magnesium alloys for degradable implants: Prospects and challenges. Prog. Mater. Sci., 2014, 60, 1-71. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. F.; Zhang, S. F.; Duo, S. W. Influence of phytic acid concentration on coating properties obtained by MAO treatment on magnesium alloys. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2009, 255(18), 7893-7897. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Liang, J.; Wang, D.; Zhou, F. Synergistic effect of hydrophobic film and porous MAO membrane containing alkynol inhibitor for enhanced corrosion resistance of magnesium alloy. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2019, 357, 515-525. [CrossRef]

- Ezhilselvi, V.; Nithin, J.; Balaraju, J. N.; Subramanian, S. The influence of current density on the morphology and corrosion properties of MAO coatings on AZ31B magnesium alloy. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2016, 288, 221-229. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, Y.; Qi, C.; Sun, H.; Zhang, D.; Wan, Y. Effect of solvent acids on the microstructure and corrosion resistance of chitosan films on MAO-treated AZ31B magnesium alloy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2024, 277, 134349. [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Yu, H.; Chen, C.; Ma, R. L. W.; Yuen, M. M. F. Preparation and microstructure of MAO/CS composite coatings on Mg alloy. Mater. Lett., 2020, 271, 127729. [CrossRef]

- Ungan, G.; Cakir, A. Investigation of MgO effect on bioactivity of coatings produced by MAO. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2015, 282, 52-60. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, W.; Xu, T.; Li, H.; Jiang, B.; Miao, X. Preparation and corrosion resistance of a self-sealing hydroxyapatite-MgO coating on magnesium alloy by microarc oxidation. Ceram. Int., 2022, 48(10), 13676-13683. [CrossRef]

- Vladimirov, B. V.; Krit, B. L.; Lyudin, V. B.; Morozova, N. V.; Rossiiskaya, A. D.; Suminov, I. V.; Epel’Feld, A. V. Microarc oxidation of magnesium alloys: A review. Surf. Eng. Appl. Electrochem., 2014, 50, 195-232. [CrossRef]

- Pesode, P.; Barve, S.; Dayane, S. Antibacterial coating on magnesium alloys by MAO for biomedical applications. Res. Biomed. Eng., 2024, 40(2), 409-433. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Lu, C.; Wang, C.; Song, R. Degradation behavior of n-MAO/EPD bio-ceramic composite coatings on magnesium alloy in simulated body fluid. J. Alloy. Compd., 2015, 625, 258-265. [CrossRef]

- Razavi, M.; Fathi, M.; Savabi, O.; Vashaee, D.; Tayebi, L. Biodegradable magnesium alloy coated by fluoridated hydroxyapatite using MAO/EPD technique. Surf. Eng., 2014, 30(8), 545-551. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.F.; An, M.Z.; Xu, S.; Huo, H.B. Formation of oxygen bubbles and its influence on current efficiency in micro-arc oxidation process of AZ91D magnesium alloy. Thin Solid Films, 2005, 485(1-2), 53-58. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H. F.; An, M. Z.; Huo, H. B.; Xu, S.; Wu, L. J. Microstructure characteristic of ceramic coatings fabricated on magnesium alloys by micro-arc oxidation in alkaline silicate solutions. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2006, 252(22), 7911-7916. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. F.; Zhang, S. F. Formation of micro-arc oxidation coatings on AZ91HP magnesium alloys. Corros. Sci., 2009, 51(12), 2820-2825. [CrossRef]

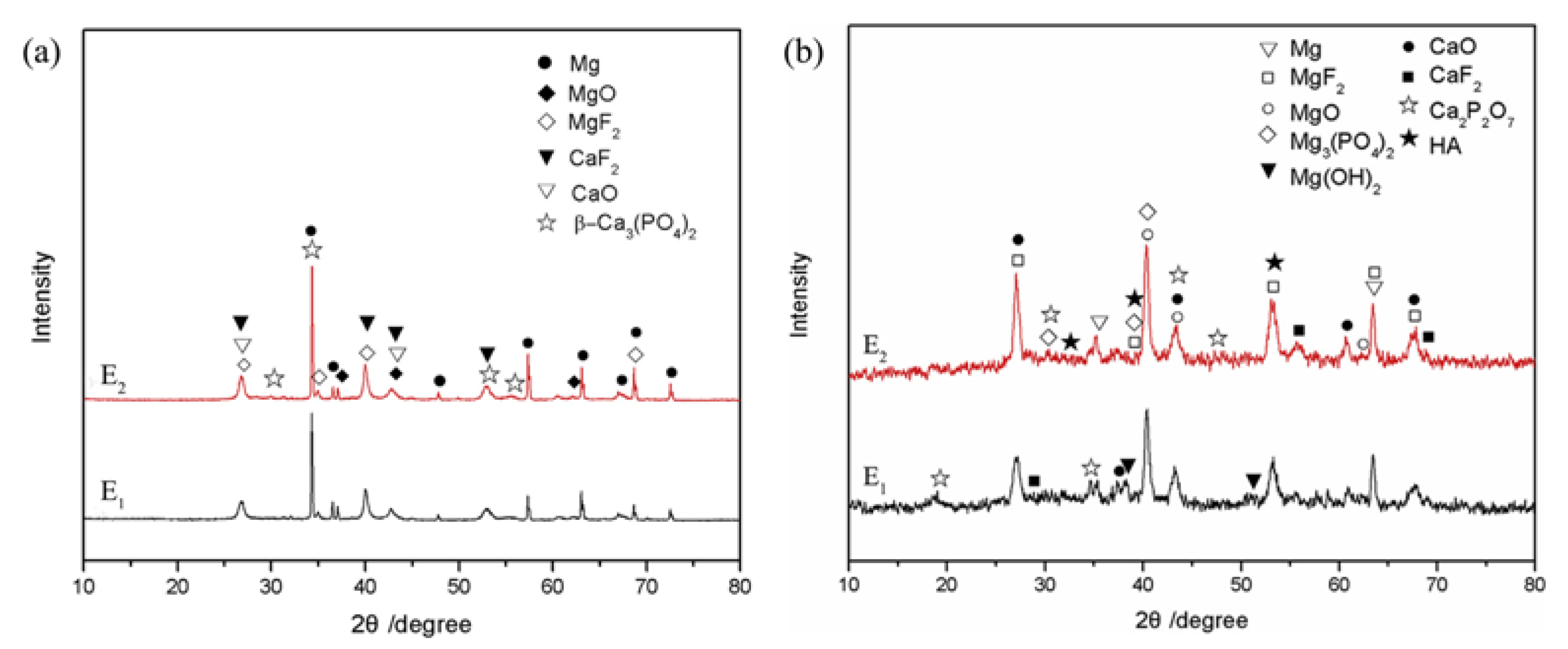

- Tang, H.; Han, Y.; Wu, T.; Tao, W.; Jian, X.; Wu, Y.; Xu, F. Synthesis and properties of hydroxyapatite-containing coating on AZ31 magnesium alloy by micro-arc oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2017, 400, 391-404. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H. F.; An, M. Z. Growth of ceramic coatings on AZ91D magnesium alloys by micro-arc oxidation in aluminate–fluoride solutions and evaluation of corrosion resistance. Appl. Surf. Sci, 2005, 246(1-3), 229-238. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.C.; Cui, C.X.; Wang, Q.Z.; Bu, S.J. Growth characteristics and corrosion resistance of micro-arc oxidation coating on pure magnesium for biomedical applications. Corros. Sci., 2010, 52(7), 2228-2234. [CrossRef]

- Durdu, S.; Aytac, A.; Usta, M. Characterization and corrosion behavior of ceramic coating on magnesium by micro-arc oxidation. J. Alloy. Compd., 2011, 509(34), 8601-8606. [CrossRef]

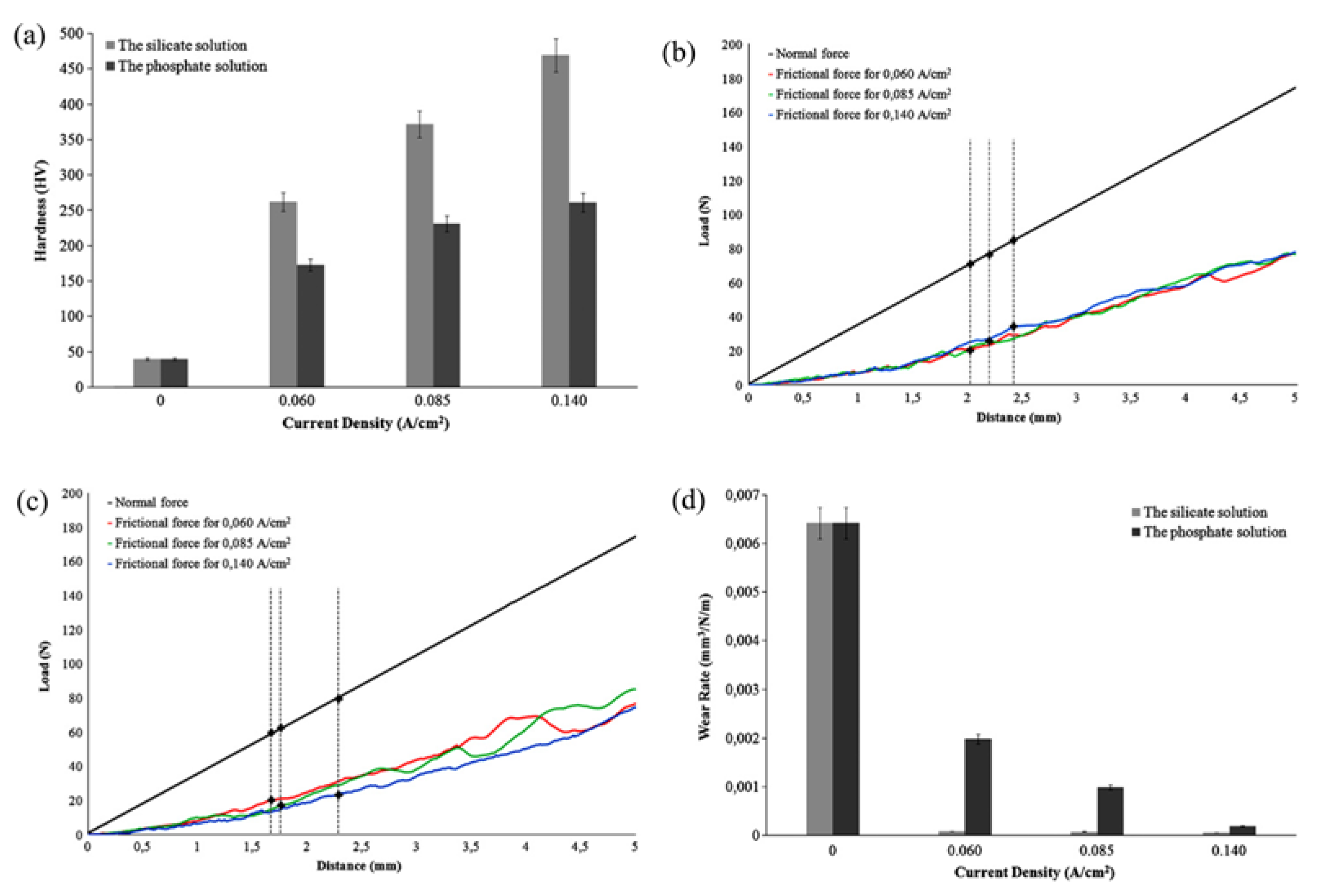

- Muhaffel, F.; Cimenoglu, H. Development of corrosion and wear resistant micro-arc oxidation coating on a magnesium alloy. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2019, 357, 822-832. [CrossRef]

- Durdu, S.; Usta, M. Characterization and mechanical properties of coatings on magnesium by micro arc oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2012, 261, 774-782. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y. K.; Chen, C. Z.; Wang, D. G.; Yu, X. Microstructure and biological properties of micro-arc oxidation coatings on ZK60 magnesium alloy. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B, 2012, 100(6), 1574-1586. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y. K.; Chen, C. Z.; Wang, D. G.; Lin, Z. Q. Preparation and bioactivity of micro-arc oxidized calcium phosphate coatings. Mater. Chem. Phys., 2013, 141(2-3), 842-849. [CrossRef]

- Ma, W. H.; Liu, Y. J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y. Z.. Improved biological performance of magnesium by micro-arc oxidation. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res., 2015, 48(3), 214-225. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Q.; Wang, L.; Zeng, M. Q.; Zeng, R. C.; Kannan, M. B.; Lin, C. G.; Zheng, Y. F. Biodegradation behavior of micro-arc oxidation coating on magnesium alloy-from a protein perspective. Bioact. Mater., 2020, 5(2), 398-409. [CrossRef]

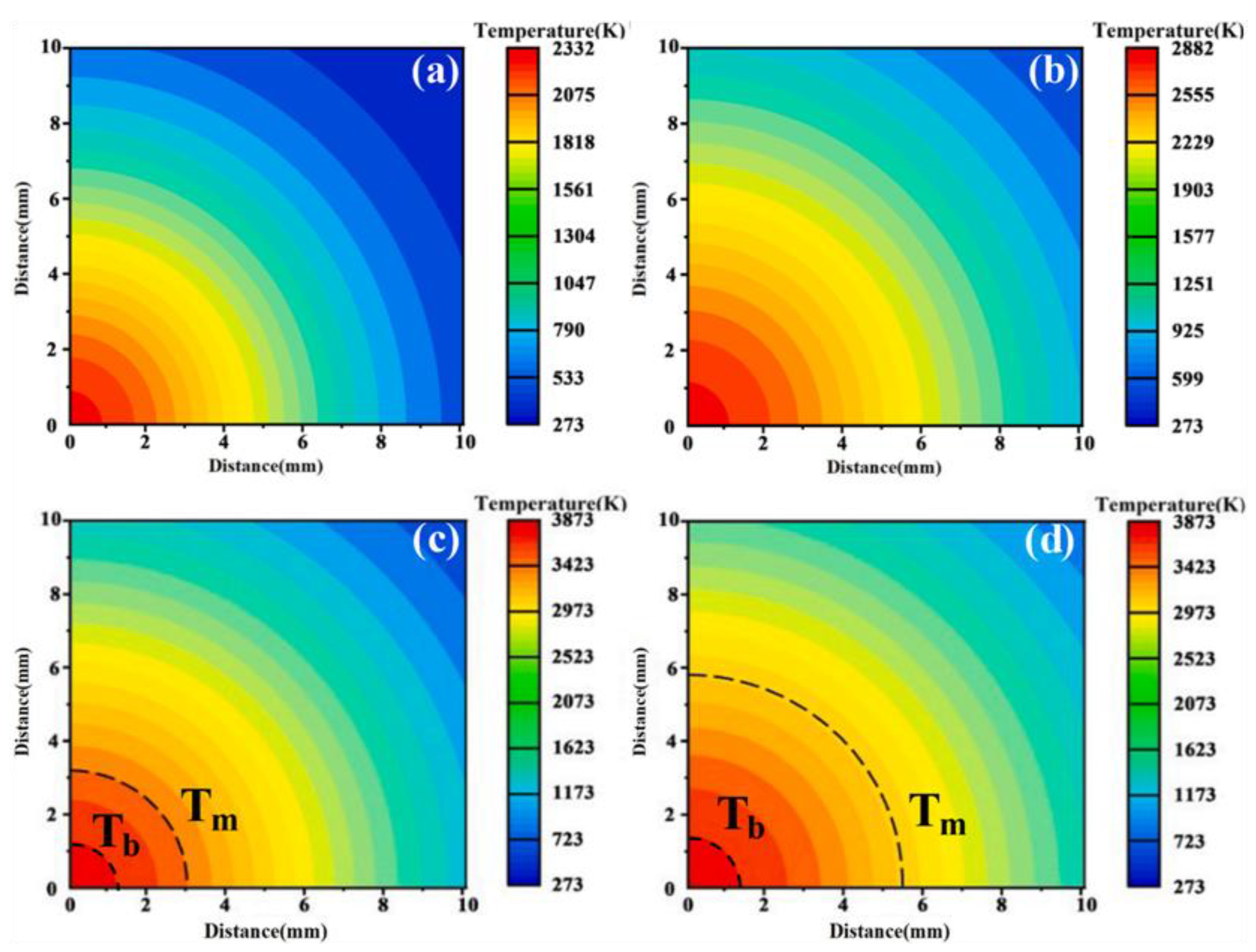

- Shao, Y.; Han, X.; Ma, C.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, X.; Xu, J. The thermal dynamic simulation and microstructure characterization of micro-arc oxidation (MAO) films on magnesium AZ31 irradiated by high-intensity pulsed ion beam. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2025, 682, 161705. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhao, H.; Qu, S.; Li, X.; Li, Y. New developments of Ti-based alloys for biomedical applications. Materials, 2014, 7(3), 1709-1800. [CrossRef]

- Geetha, M.; Singh, A. K.; Asokamani, R.; Gogia, A. K. Ti based biomaterials, the ultimate choice for orthopaedic implants-A review. Prog. Mater. Sci., 2009, 54(3), 397-425. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S. L.; Wang, X. M.; Qin, F. X.; Inoue, A. A new Ti-based bulk glassy alloy with potential for biomedical application. Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 2007, 459(1-2), 233-237. [CrossRef]

- Liao, S. C.; Chang, C. T.; Chen, C. Y.; Lee, C. H.; Lin, W. L. Functionalization of pure titanium MAO coatings by surface modifications for biomedical applications. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2020, 394, 125812. [CrossRef]

- Xi, F.Q.; Zhang, X.W.; Kang, Y.Y.; Wen, X.Y.; Liu, Y. Mechanistic analysis of improving the corrosion performance of MAO coatings on Ti-6Al-4V alloys by annealing. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2024, 476, 130264. [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, P. A. B.; Rossi, M. C.; Grandini, C. R.; Afonso, C. R. M. Assessment of applied voltage on the structure, pore size, hardness, elastic modulus, and adhesion of anodic coatings in Ca-, P-, and Mg-rich produced by MAO in Ti-25Ta-Zr alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol., 2023, 26, 4656-4669. [CrossRef]

- Maj, Ł.; Muhaffel, F.; Jarzębska, A.; Trelka, A.; Trembecka-W´ojciga, K.; Kawałko, J.; Kulczyk, M.; Bieda, M.; Çimeno˘glu, H. Enhancing the tribological performance of MAO coatings through hydrostatic extrusion of cp-Ti. J. Alloy. Compd., 2025, 1010, 178246. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Sun, J.; Huang, X. Formation mechanism of HA-based coatings by micro-arc oxidation. Electrochem. Commun., 2008, 10(4), 510-513. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Hong, S. H.; Xu, K. Structure and in vitro bioactivity of titania-based films by micro-arc oxidation. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2003, 168(2-3), 249-258. [CrossRef]

- Song, W. H.; Ryu, H. S.; Hong, S. H. Antibacterial properties of Ag (or Pt)-containing calcium phosphate coatings formed by micro-arc oxidation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A, 2009, 88(1), 246-254. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J. Effect of ZrO2 particle on the performance of micro-arc oxidation coatings on Ti6Al4V. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2015, 342, 183-190. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z. Q.; Ivanisenko, Y.; Diemant, T.; Caron, A.; Chuvilin, A.; Jiang, J. Z.; Valiev, R.Z.; Qi, M.; Fecht, H. J. Synthesis and properties of hydroxyapatite-containing porous titania coating on ultrafine-grained titanium by micro-arc oxidation. Acta Biomater., 2010, 6(7), 2816-2825. [CrossRef]

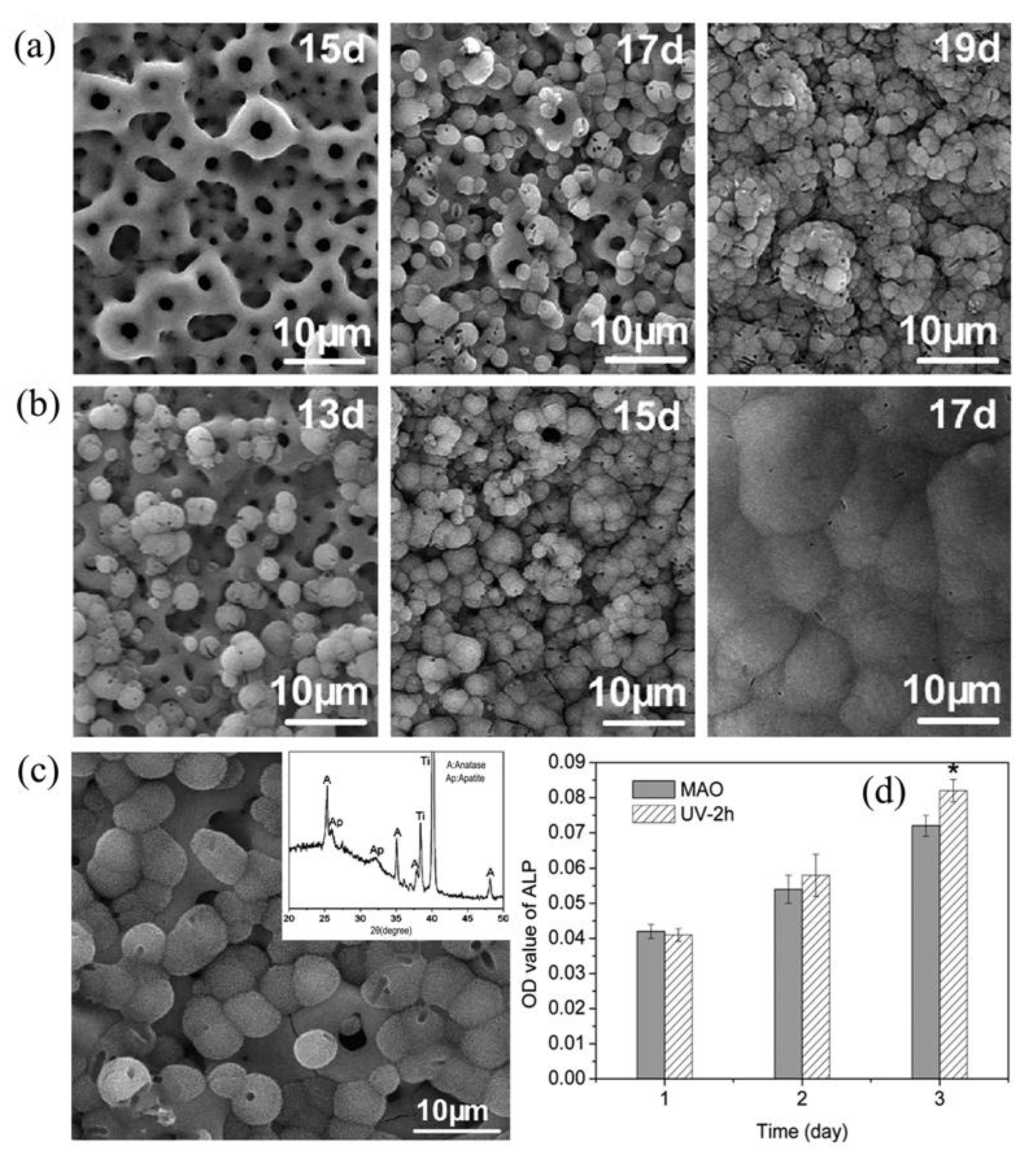

- Xu, L.; Wu, C.; Lei, X.; Zhang, K.; Liu, C.; Ding, J.; Shi, X. Effect of oxidation time on cytocompatibility of ultrafine-grained pure Ti in micro-arc oxidation treatment. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2018, 342, 12-22. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Chen, D.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, K. UV-enhanced bioactivity and cell response of micro-arc oxidized titania coatings. Acta Biomater, 2008, 4(5), 1518-1529. [CrossRef]

- Kung, K. C.; Lee, T. M.; Lui, T. S. Bioactivity and corrosion properties of novel coatings containing strontium by micro-arc oxidation. J. Alloy. Compd., 2010, 508(2), 384-390. [CrossRef]

- Cimenoglu, H.; Gunyuz, M.; Kose, G. T.; Baydogan, M.; Uğurlu, F.; Sener, C. Micro-arc oxidation of Ti6Al4V and Ti6Al7Nb alloys for biomedical applications. Mater. Charact., 2011, 62(3), 304-311. [CrossRef]

- Li, J. X.; Zhang, Y. M.; Han, Y.; Zhao, Y. M. Effects of micro-arc oxidation on bond strength of titanium to porcelain. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2010, 204(8), 1252-1258. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J. H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, G. L.; Sun, M.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Q. L. Growth characteristics and properties of micro-arc oxidation coating on SLM-produced TC4 alloy for biomedical applications. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2019, 479, 727-737. [CrossRef]

- Hao, G. D.; Zhang, D. Y.; Lou, L. Y.; Yin, L. C. High-temperature oxidation resistance of ceramic coatings on titanium alloy by micro-arc oxidation in aluminate solution. Prog. Nat. Sci., 2022, 32(4), 401-406. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. H.; Chen, P. H.; Huang, D. N.; Wu, Z. Z.; Yang, T.; Kai, J. J.; Yan, M. Micro-arc oxidation for improving high-temperature oxidation resistance of additively manufacturing Ti2AlNb. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2022, 445, 128719. [CrossRef]

- George, E. P.; Raabe, D.; Ritchie, R. O. High-entropy alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater, 2019, 4(8), 515-534. [CrossRef]

- Miracle, D. B.; Senkov, O. N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Mater., 2017, 122, 448-511. [CrossRef]

- Li, W. D.; Xie, D.; Li, D. Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y. F.; Liaw, P. K. Mechanical behavior of high-entropy alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci., 2021, 118, 100777. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Yang, W.; Xu, D.; Shao, W.; Chen, J. In situ formation of micro arc oxidation ceramic coating on refractory high entropy alloy. Int. J. Refract. Met. H., 2024, 120, 106563. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z. H.; Yang, W.; Xu, D. P.; Wu, S. K.; Yao, X. F.; Lv, Y. K.; Chen, J. Improvement of high temperature oxidation resistance of micro arc oxidation coated AlTiNbMo0.5Ta0.5Zr high entropy alloy. Mater. Lett., 2020, 262, 127192. [CrossRef]

- Senkov, O. N.; Wilks, G. B.; Miracle, D. B.; Chuang, C. P.; Liaw, P. K. Refractory high-entropy alloys. Intermetallics, 2010, 18(9), 1758-1765. [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.X.; Jiao, Z. P.; Yan, S.; Guo, L.; Feng, L. Z.; Yu, J. X. Microbeam plasma arc remanufacturing: Effects of Al on microstructure, wear resistance, corrosion resistance and high temperature oxidation resistance of AlxCoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy cladding layer. Vacuum, 2020, 174, 109178. [CrossRef]

- Shi, X. Q.; Yang, W.; Cheng, Z. H.; Shao, W. T.; Xu, D. P.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J. Influence of micro arc oxidation on high temperature oxidation resistance of AlTiCrVZr refractory high entropy alloy. Int. J. Refract. Met. H., 2021, 98, 105562. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cheng, Z. H.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, X. Q.; Rao, M.; Wu, S.K. Effect of voltage on the microstructure and high-temperature oxidation resistance of micro-arc oxidation coatings on AlTiCrVZr refractory high-entropy alloy. Coatings, 2023, 13(1), 14. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z. H.; Chen, M. F.; You, C.; Li, W.; Tie, D.; Liu, H. F. Effect of α-Al2O3 additive on the microstructure and properties of MAO coatings prepared on low carbon steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol, 2020, 9(3), 3875-3884. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z. J.; Zeng, C. L. Oxidation behavior and electrical property of ferritic stainless steel interconnects with a Cr–La alloying layer by high-energy micro-arc alloying process. J. Power Sources, 2010, 195(21), 7370-7374. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z. J.; Zeng, C. LaCrO3-based coatings deposited by high-energy micro-arc alloying process on a ferritic stainless steel interconnect material. J. Power Sources, 2010, 195(13), 4242-4246. [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Shao, Y.; Zeng, C.; Wu, M.; Li, W. Oxidation characterization of FeAl coated 316 stainless steel interconnects by high-energy micro-arc alloying technique for SOFC. Mater. Lett., 2011, 65(19-20), 3180-3183. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L. H.; Shen, D. J.; Zhang, J. W.; Song, J.; Li, L. Evolution of micro-arc oxidation behaviors of the hot-dipping aluminum coatings on Q235 steel substrate. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2011, 257(9), 4144-4150. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Z.; Feng, S. S.; Li, Z. M.; Chen, Z. G.; Zhao, T. Y. Microstructure and properties of micro-arc oxidation ceramic films on AerMet100 steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol., 2020, 9(3), 6014-6027. [CrossRef]

- Durdu, S.; Aktuğ, S. L.; Korkmaz, K. Characterization and mechanical properties of the duplex coatings produced on steel by electro-spark deposition and micro-arc oxidation. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2013, 236, 303-308. [CrossRef]

- Durdu, S.; Korkmaz, K.; Aktuğ, S. L.; Çakır, A. Characterization and bioactivity of hydroxyapatite-based coatings formed on steel by electro-spark deposition and micro-arc oxidation. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2017, 326, 111-120. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S. C.; Cheng, B.; Liu, A.; Liu, Z. H.; Xu, G. M.; Liu, P.; Lu, H. L. Research on micro-arc oxidation method based on passivation layer on non-valve metal low-carbon steel surface. Tribol. Int., 2024, 200, 110114. [CrossRef]

- Malinovschi, V.; Marin, A.; Moga, S.; Negrea, D. Preparation and characterization of anticorrosive layers deposited by micro-arc oxidation on low carbon steel. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2014, 253, 194-198. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Li, W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; You, C. Preparation, characteristics and corrosion properties of α-Al2O3 coatings on 10B21 carbon steel by micro-arc oxidation. Surf. Coat. Tech., 2019, 358, 637-645. [CrossRef]

| Component | Concentration/Dosage | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Silicate (Na2SiO3) | 15 g/L | Acts as a silicon source, participates in alumina coating formation. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | 1 g/L | Adjusts electrolyte pH and enhances conductivity. |

| Glycerol (C3H8O3) | 2 mL/L | Serves as a dispersant and stabilizer, ensuring uniform mixing. |

| Silicon Carbide (SiC) Particles | 3 g/L | Particle size ~50 μm; continuous stirring required to maintain suspension. |

| Ingredients | Concentration | Ingredients | Concentration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref 53 | NaAlO2 | 9 g/L | Ref 55 | C6H18O24P6 | 5 g/L |

| KF | 6 g/L | HF(40%) | 20 g/L | ||

| Ref 54 | Na2SiO3 | 6 g/L | H3PO4(98%) | 58 g/L | |

| KF | 2 g/L | H3BO3 | 35 g/L | ||

| KOH | 2 g/L | Hexamethylenetetramine | 360 g/L | ||

| C3H8O3 | 10 mL/L | PH regulator | pH=7.0 |

| Sample | Electrolyte composition | Applied voltage (V) | Initial current density (mA·mm-2) | Final current density (mA·mm-2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.6 M Na2CO3 | 200 | 4.69 | 0.63 |

| A2 | 0.6 M Na2CO3 | 350 | 8.78 | 1.53 |

| B1 | 0.2 M CA | 350 | 7.34 | 1.4 |

| B2 | 0.2 M CA | 400 | 9.69 | 2.13 |

| C1 | 0.04 M Na3PO4 | 350 | 2.18 | 0.16 |

| C2 | 0.04 M Na3PO4 | 450 | 4.28 | 1.09 |

| D1 | 0.2 M CA + 0.02M β-GP | 250 | 2.09 | 0.06 |

| D2 | 0.2 M CA + 0.02M β-GP | 350 | 4.53 | 0.12 |

| D3 | 0.2 M CA + 0.02M β-GP | 450 | 7.03 | 0.47 |

| D4 | 0.2 M CA + 0.02M β-GP | 500 | 9.53 | 0.66 |

| References | Electrolyte Composition | Process Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Ref 91 | Na2SiO3 (12 g/L) + NaOH (1.2 g/L) | Voltage: 500 V, Frequency: 500 Hz, Duty cycle: 10%, Time: 10 min |

| Ref 94 | Na2SiO3 (50 g/L) | Voltage: 450 V, Frequency: 600 Hz, Duty cycle: 8%, Time: 5 min |

| Na2SiO3 (50 g/L) + (NaPO3)6 (25 g/L) + NaOH (5 g/L) | ||

| Na2SiO3 (50 g/L) + (NaPO3)6 (25 g/L) + NaOH (5 g/L) + Na2B4O7 (3 g/L) + KF (4 g/L) |

| Different methods | Wire arc spraying + MAO | Hot-dip aluminizing + MAO | Laser cladding + MAO | Electro-spark deposition + MAO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrolyte composition | 5 g/L Na2B4O7, 5 g/L KOH, 2 g/L Na3PO4, 20 g/L glycerin, with distilled water as the solvent |

8 g/L KOH, 10 g/L Na2SiO3, with distilled water as the solvent |

12 g/L Na2SiO3, 5 g/L KOH, 0.5 g/L NaF, 3 g/L SiO2, 9 g/L TiO2 |

1.65 g/L Na3PO4, 8 g/L NaAlO2 |

| Electrical parameter | Current density: 12 A/dm2, electrolyte temperature: 20–35°C, processing time: 50–150 min | Current density: 0.5–2.5 A/dm2, electrolyte temperature: 40 ± 2°C, processing time: 0–14 min | Current density: 3 – 8 A/dm2 (optimal 5 A/dm2), electrolyte temperature: 30°C, processing time: 30 min | Cnode voltage: 550 V, cathode voltage: 160 V, processing time: 30 min |

| Coatings | NaAlO2(g/L) | NaH2PO4(g/L) | Na2CO3(g/L) | Na2B4O7(g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 15 | 3 | ||

| M2 | 15 | 3 | 3 | |

| M3 | 15 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).