Submitted:

15 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

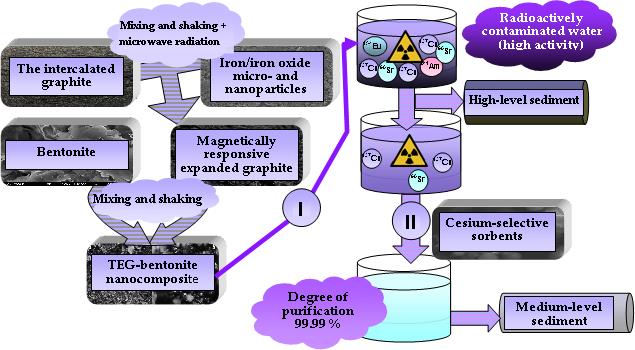

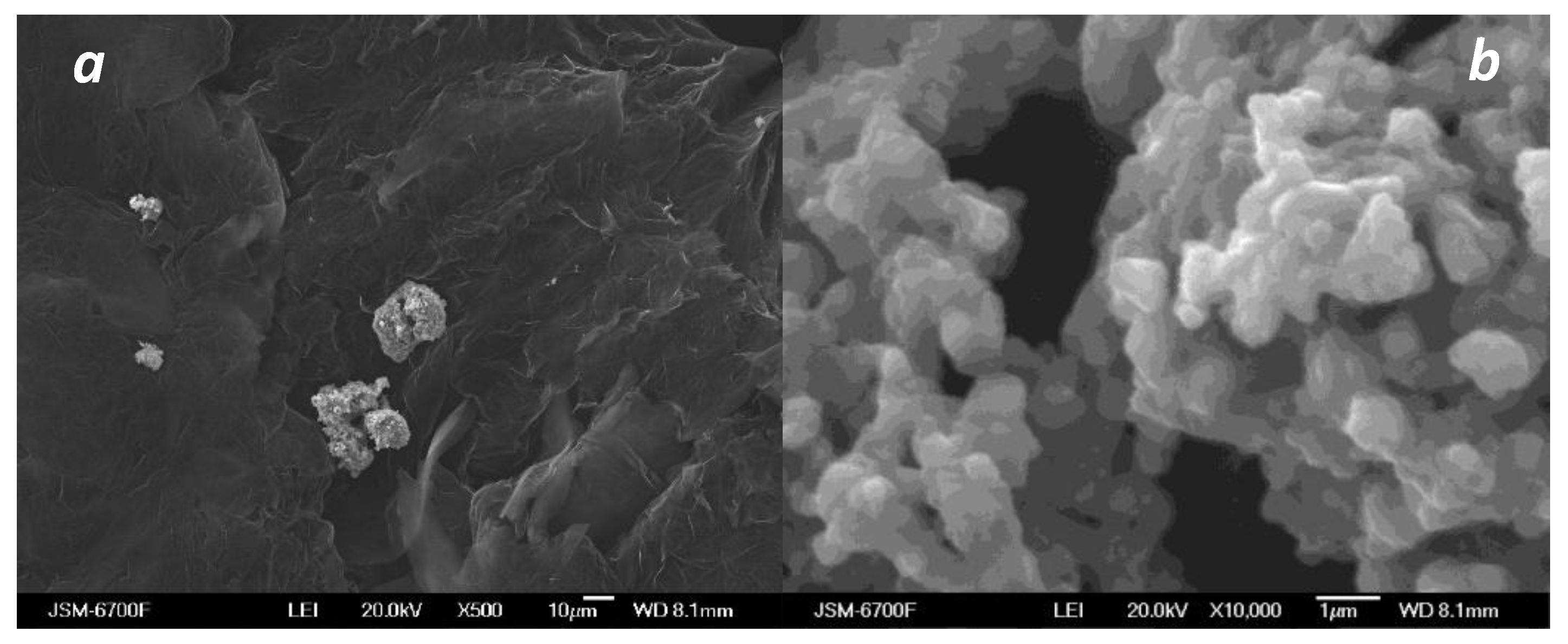

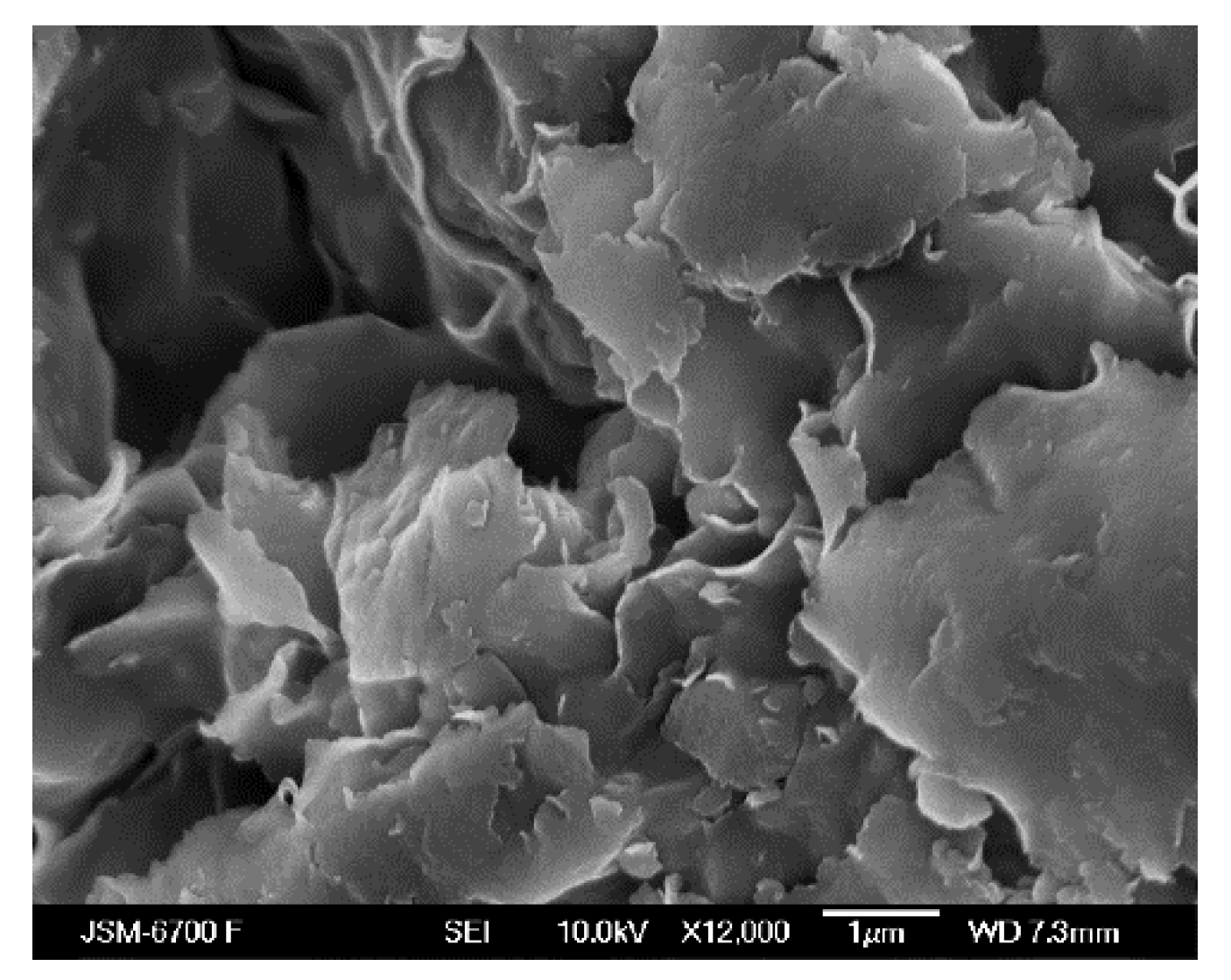

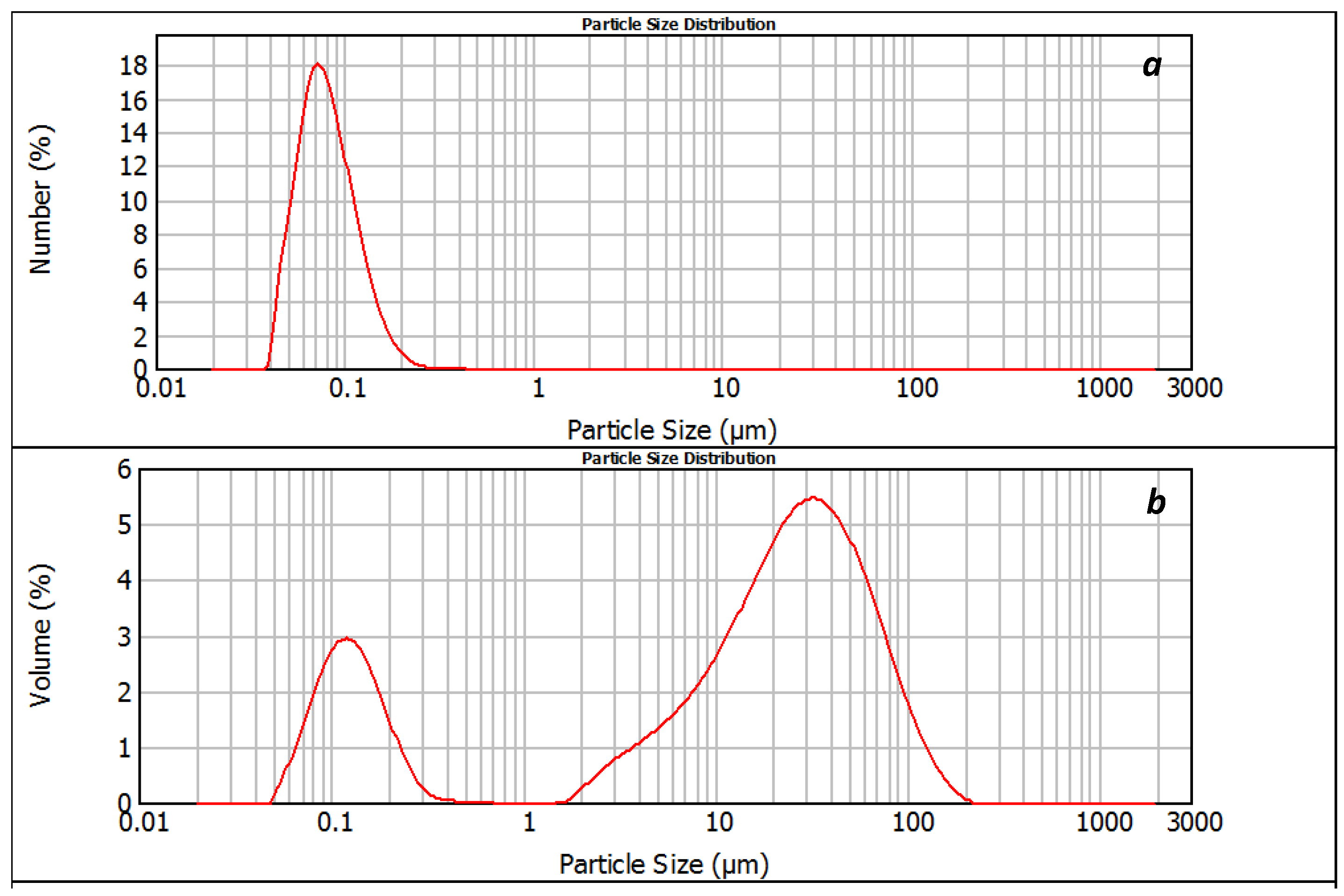

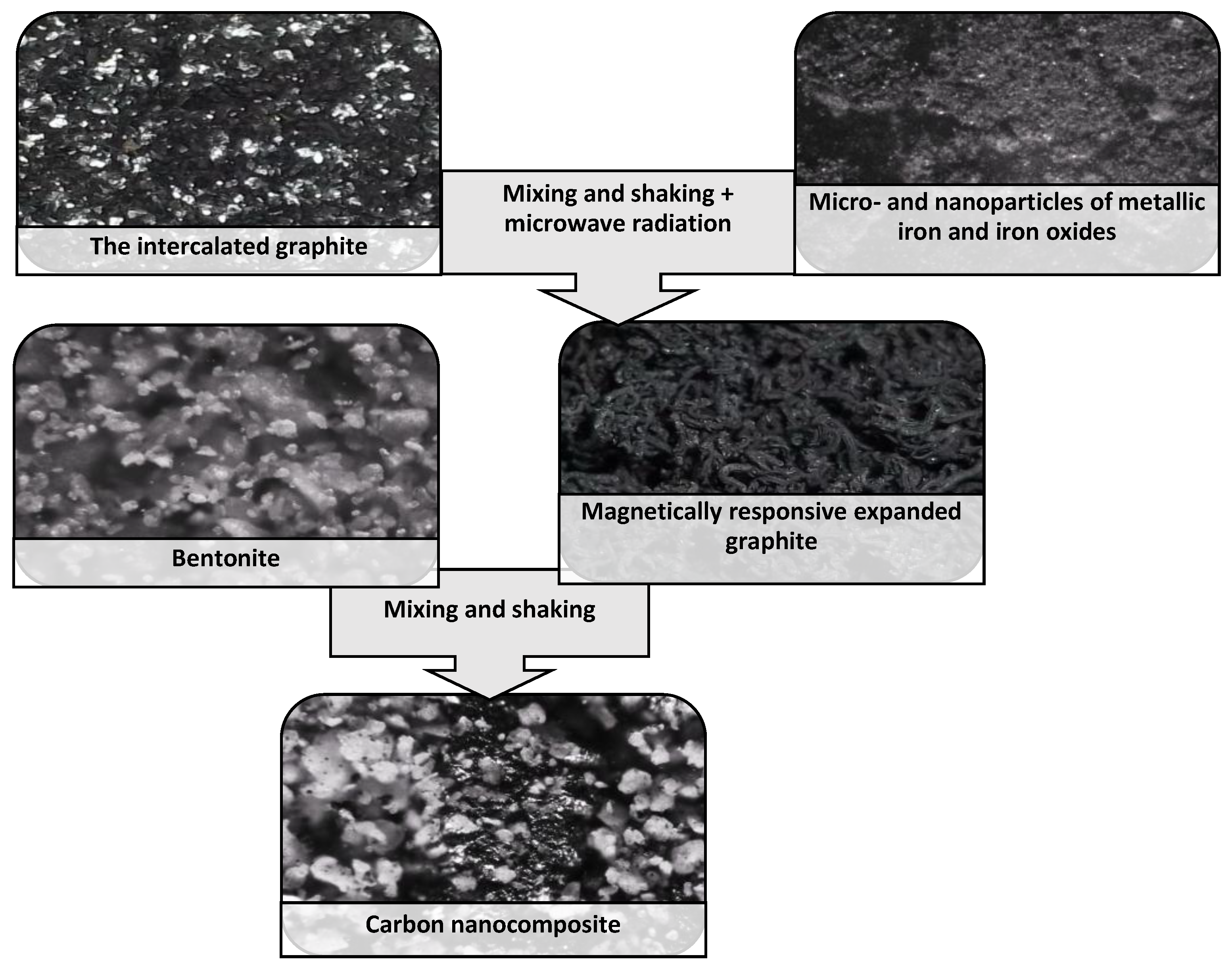

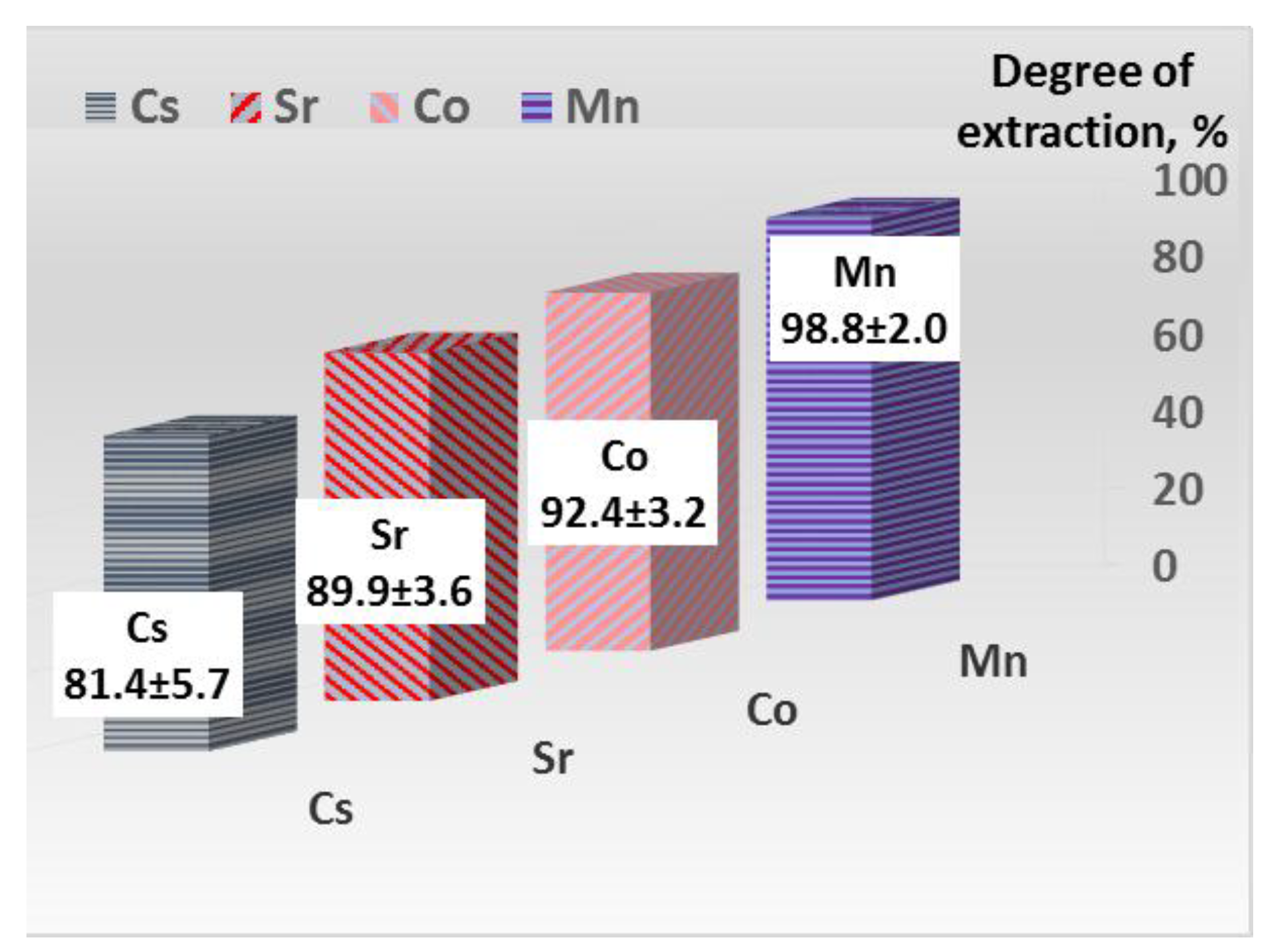

Among the main man-made water pollutants that pose a danger to the environment are oil products, heavy metals and radionuclides, as well as micro- and nanoplastics formed as a result of the destruction of polymeric materials. A characteristic feature of contaminated waters nowadays is their multicomponent and multiphase nature. To purify such waters, it is necessary to use a combination of several advanced methods, with sorption being one of them. The aim of this work is to develop a nanocomposite sorbent comprising magnetically responsive thermally expanded graphite (TEG) and the natural clay bentonite and assess its ability to purify man-made contaminated waters. In the course of the research, the methods of scanning electron microscopy, optical microscopy, dynamic light scattering, and atomic absorption spectrophotometry were used. To obtain the nanocomposite, magnetoresponsive TEG containing micro- and nanoparticles of metallic iron and its oxides as a magnetic component, and bentonite with a montmorillonite content of at least 70% and the particle size of less than 100 μm were used. Given the complex chemical nature of the surface of montmorillonite and magnetoresponsive TEG particles, the interaction of the hydrophobic centers of bentonite with the surface of TEG particles during mechanical activation leads to the formation of loose aggregates capable of sorbing particles of micro- and nanoplastics and non-polar hydrocarbons. The sorption properties of the nanocomposite are dependent on the hydrophobic centers mainly located on the surface of oxidized graphene layers in thermally expanded graphite. The hydrophilic properties of the nanocomposite are due to the presence of aluminol and silanol groups, as well as the charge on the surface of montmorillonite nanocrystals and the Brønsted centers on the surface of TEG particles. The use of the nanocomposite for purification of a nuclear power plant (NPP) radioactively contaminated water simulant containing stable isotopes of cesium, strontium, cobalt, manganese in the presence of hydrophilic and hydrophobic organic substances reduced the content of organic substances by 10-15 times, and the degree of extraction of heavy metals from water was for cesium - 81.4%, strontium – 89.9%, cobalt – 92.4%, and manganese – 98.8%. The use of a carbon nanocomposite for purification of real radioactively contaminated water obtained from the object “Shelter” (“Ukryttya” in Ukrainian), in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, Ukraine) with an activity of 137Cs – 3.3∙107 Bq/dm3, 90Sr – 4.9∙106 Bq/dm3, containing, in addition to radionuclides, organic substances, including micro- and nanoplastics, reduced the radioactivity by three orders of magnitude. The filtrate obtained after purification was free from suspended particles, including colloidal ones. The use of cesium-selective sorbents for additional purification of the filtrate allowed further decontamination of radioactively contaminated water with an efficiency of 99.99%.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Obtaining Magnetoresponsive TEG-Bentonite Nanocomposite

2.3. Research Methods

2.4. Study of the Sorption Activity of the TEG-Bentonite Nanocomposite

2.4.1. Model Solution – Simulant of Radioactively Contaminated Water of Nuclear Power Plants

- stable isotopes of radionuclides – cesium (10.2 mg/dm3), strontium (10.9 mg/dm3), cobalt (4.2 mg/dm3) and manganese (2.4 mg/dm3); they were used as nitrates (KhimLaborReaktiv, Brovary, Kyiv region, Ukraine).

- organic substances: oxalic acid (65 mg/dm3), citric acid (10 mg/dm3), the decontamination surfactant “SHCHIT K” (Shield in Ukrainian, 180 mg/dm3, “Energokhim”, Kyiv, Ukraine), which are used for decontamination of workwear, equipment and premises at nuclear power plants of Ukraine, sodium salt of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (KhimLaborReaktiv, 100 mg/dm3), shampoo/soap (150 mg/dm3), universal washing powder «Lotus» (10 mg/dm3), and oil (200 mg/dm3);

- inorganic substances – boric acid (1,200 mg/dm3), sodium hydroxide (1,040 mg/dm3), potassium hydroxide (90 mg/dm3) and nitric acid (400 mg/dm3), KhimLaborReaktiv, Brovary, Kyiv region, Ukraine.

2.4.2. Radioactively Contaminated Water

2.4.3. Study of Sorption Properties of TEG Nanocomposite

2.4.4. Further Purification of Filtrate

3. Results and Discussion

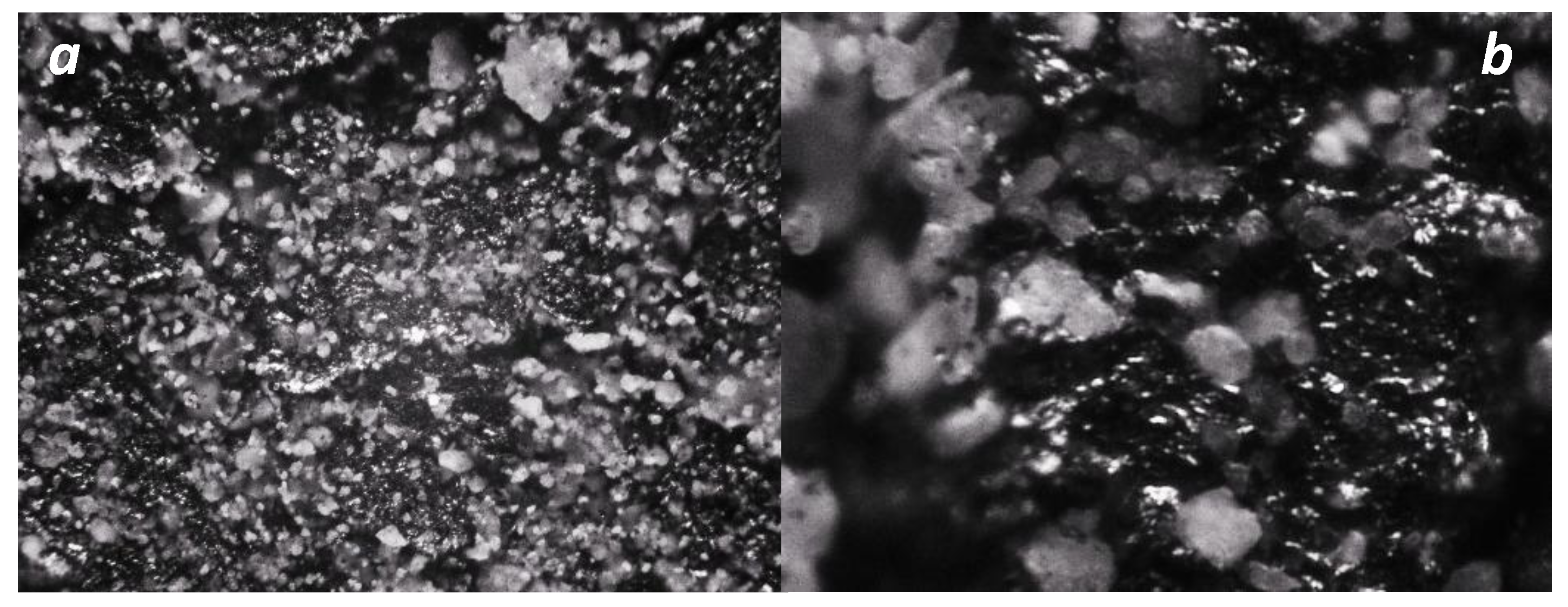

3.1. Characterisation of the Nanocomposite Based on Bentonite and Magnetically Responsive TEG

3.2. Study of Sorption Properties of the Obtained Nanocomposite

3.2.1. Purification of NPP Radioactive Wastewater Simulant

3.2.2. Purification of a Sample of Radioactively Contaminated Water (RCW)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strokal, V.; Kuiper, E.J.; Bak, M.P.; Vriend, P.; Wang, M.; van Wijnen, J.; Strokal, M. Future microplastics in the black Sea: River exports and reduction options for zero pollution. Mar Pollut Bull. 2022, 178, 113633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivva, S. , Zheleznyak, M., Bezhenar, R., Pylypenko, O., Sorokin, M., Demydenko, A., Kanivets, V.; Laptev, G., Votsekhovich, O., Boyko, V., Eds.; HYPERLINK "https: //ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/search/q=author:%22Gudkov%2C+Dmitri%22&sort=date%20desc,%20bibcode%20desc"Gudkov, D. Modeling of major environmental risks for the Kyiv city, Ukraine from the Dnieper river waters - inundation of coastal areas and contamination by the radionuclides deposited in bottom sediments after the Chornobyl accident, EGU General Assembly 2021, online, 19–30 Apr 2021, EGU21-13038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumilova, O.; Sukhodolov, A.; Osadcha, N.; Oreshchenko, A.; Constantinescu, G.; Afanasyev, S.; Afanasyev, S. , Koken, M.; Osadchyi, V.; Rhoads, B.; et al. Environmental effects of the Kakhovka Dam destruction by warfare in Ukraine. Science 2025, 387, 6739–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zub, L.; Prokopuk, M.; Netsvetov, M.; Gudkov, D. Does long-term radiation exposure in Chornobyl impact the reproductive structures of Nuphar lutea (Linn’e) Smith? Environmental Pollution 2024, 363, 125067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkhowa, S.; Sarma, J.; Rani Das, A. Chapter 15. Radiological contaminants in water: pollution, health risk, and treatment. In: Contamination of Water. 2021, pp. 217–236. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Rahman, R.O.; Ibrahium, H.A.; Hung, Y-T. Liquid radioactive wastes treatment: A review. Water 2011, 3, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossard, A.; Lilin, A.; Faure, S. Gels, coatings and foams for radioactive surface decontamination: State of the art and challenges for the nuclear industry. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2022, 149, 104255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, L.I.; Khan, V.E.; Kashkovskyi, V.I.; Dzhuzha, O.V. Purification of drain water and distillation residue from organic compounds, transuranic elements, and uranium at the Chornobyl NPP. Science and Innovation 2014, 10, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Love, D.C.; Rochman, C.M.; Neff, R.A. Microplastics in seafood and the implications for human health. Current Environmental Health Reports 2018, 5, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Jia, Z. Recent insights into uptake, toxicity, and molecular targets of microplastics and nanoplastics relevant to human health impacts. IScience 2023, 26, 106061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, Z.; Meng, X.; Li, J.; Chen, H.; Yu, T.; Xu, M. A preliminary study on the “hitchhiking” of radionuclides on microplastics: A new threat to the marine environment from compound pollution. Toxics 2025, 13, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, Z.; Li, J.; Huang, F.; Zhu, X.; Gao, F.; Yu, T.; Hu, M. Marine microplastics fuel long-range transport of radioactive nuclides: A review. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2025, 221, 118540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, B.; Xin, X.; Lee, K.; Chen, B. Microplastic and oil pollution in oceans: Interactions and environmental impacts. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 838, 156142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Hu, X.; Lin, H.; Yu, G.; Shen, L.; Yu, W. , Li, B.; Leihong, Z.; Ying, M. Membrane technology for microplastic removal: Microplastic occurrence, challenges, and innovations of process and materials. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 520, 166183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topuz, F.; Abdulhamid, M.A. Tailored nanofibrous polyimide-based membranes for highly effective oil spill cleanup in marine ecosystems. Chemosphere 2024, 368, 143730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rosset, A.; Torres-Mendieta, R.; Pasternak, G.; Yalcinkaya, F. Synergistic effects of natural biosurfactant and metal oxides modification on PVDF nanofiber filters for efficient microplastic and oil removal. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2020, 194, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummers, W.S.; Offeman, R.E. Preparation of graphitic oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feicht, P.; Biskupek, J.; Gorelik, T.E.; Renner, J.; Halbig, C.E.; Maranska, M.; et al. Brodie’s or Hummers’ method: oxidation conditions determine the structure of graphene oxide. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 8955–8959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadoshnikov, V.M.; Melnychenko, T.I.; Arkhipenko, O.M.; Tutskyi, D.H.; Komarov, V.O.; Bulavin, L.A.; Zabulonov, Y.L. A composite magnetosensitive sorbent based on the expanded graphite for the clean-up of oil spills: Synthesis and structural properties. C 2023, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, D.; Rojviroon, T.; Niamlang, S.; Militký, J.; Wiener, J; Večerník, J.; Melicheríková, J.; Müllerová, J. Effects of expanded graphite’s structural and elemental characteristics on its oil and heavy metal sorption properties. Scientifc Reports 2024, 14, 13716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Bi, T.; Chen, H.; Hu, Y.; Tian, F.; Lin, Q. Petroleum residue-based ultrathin-wall graphitized mesoporous carbon and its high-efficiency adsorption mechanism. Diamond and Related Materials 2024, 148, 111497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigler, S,; Dotzer, C. ; Hof, F.; Bauer, W.; Hirsch, A. Sulfur species in graphene oxide. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 9490–9496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirov, R.R.; Shayimova, J.; Nasirova, Z.; Solodov, A.; Dimiev, A.M. Analysis of competitive binding of several metal cations by graphene oxide reveals the quantity and spatial distribution of carboxyl groups on its surface. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2018, 20, 2320–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, P.; Southard, R.J. Cation exchange capacity of layer silicates and palagonitized glass in mafic volcanic rocks: a comparative study of bulk extraction and in situ techniques. Clays Clay Min. 1996, 44, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Fu, T.; Sarwar, M.T.; Huaming Yang, H. Recent progress in radionuclides adsorption by bentonite-based materials as ideal adsorbents and buffer/backfill materials. Applied Clay Science 2023, 232, 106796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, F. Ch 1: Montmorillonite: An introduction to properties and utilization. In: Current Topics in the Utilization of Clay in Industrial and Medical Applications, Zoveidavianpoor, M. (Ed.), IntechOpen, 2018, pp. 3–23. ISBN978-1-78923-729-0. [CrossRef]

- İnan, S. Inorganic ion exchangers for strontium removal from radioactive waste: a review. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 2022, 331, 1137–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.S.; Afolabi, O.O. Enhancement and modelling of caesium and strontium adsorption behaviour on natural and activated bentonite. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2025, 37, 103937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslim, W.A.; Al-Nasri, S.K.; Albayati, T.M.; Salih, I.K. Investigation of bentonite clay minerals as a natural adsorbents for Cs-137 real radioactive wastewater treatment. Desalination and Water Treatment 2024, 317, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodakov, G.S. Fizika izmel’cheniya (Physics of Comminution in Russian), Nauka Publ.: Moscow, Russia, 1972. UDK 532. ,.

- Zabashta, Yu.F.; Kovalchuk, V.I.; Svechnikova, O.S.; Bulavin, L.A. Electrocapillary properties of hydrogels. Ukrainian Journal of Physics 2022, 67, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, E.; Rounaghi, S.A.; Eckert, J. Mechanochemical synthesis of rosin-modified montmorillonite: A breakthrough approach to the next generation of OMMT/rubber nanocomposites. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudina, T.F.; Ershova, T.V.; Beylina, N.Yu.; Smirnov, N.N.; Bratkov, I.V.; Shchennikov, D.V. Mechanochemical activation of graphite materials. News of higher educational institutions. Chemistry and chemical technology 2012, 55, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Smirnova, D. N.; Grishin, I. S.; Smirnov, N. N. Synthesis, structure and properties of bentonite - activated carbon composite. ChemChemTech [Izv. Vyssh. Uchebn. Zaved. Khim. Khim. Tekhnol. in Russian] 2024, 67, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashkova, D.; Grishin, I.; Smirnov, N. Mechanism of tetracycline sorption on carbon-bentonite. From Chemistry Towards Technology Step-By-Step, 2024; 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiedkin, D.B.; Grebenyuk, A.G.; Babich, I.V.; Plyuto, Y.V.; Kartel, M.T. Experimental and theoretical study on expanded graphite oxidation. Surface (Poverkhnya, in Ukrainian) 2015, 7, 126–136. [Google Scholar]

- Boichenko, S.; Lejda, K.; Mateichyk, V.; Topilnytskyi, P. Problems of Chemmotology. Theory and Practice of Rational Use of Traditional and Alternative Fuels & Lubricants: Monograph; Center of Educational Literature: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2017; pp. 136–141. ISBN 978-617-673-632-5. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 15705: 2002; Water Quality: Determination of the Chemical Oxygen Demand Index (ST-COD)-Small-Scale Sealed-Tube Method. International Standardisation Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Rudenko, L. I.; Gumenna, O.A.; Dzhuzha, O.V. Membrane methods of treatment of water, which contains polymeric substances and compounds of uranium, strontium, and sodium. Reports of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine 2010, 6, 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Zabulonov, Y.; Melnychenko, T.; Kadoshnikov, V.; Kuzenko, S.; Guzii, S.; Peer, I. New sorbents and their application for deactivation of liquid radioactive waste. In: Zabulonov, Y., Peer, I., Zheleznyak, M. (eds) Liquid Radioactive Waste Treatment: Ukrainian Context. LWRT 2022. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, vol 469. Springer, Cham. 2024, pp. 126–136. [CrossRef]

- Toropov, A.S.; Satayeva, A.R.; Mikhalovsky, S.; Cundy, A.B. The use of composite ferrocyanide materials for treatment of high salinity liquid radioactive wastes rich in cesium isotopes. Radiochimica Acta 2014, 102, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.M.; Zhang, J.L.; Li, K.J.; Ren, S.; Wang, Z.M.; Jiang, C.H.; Li, H.T. Dissolution behaviors of various carbonaceous materials in liquid iron: Interaction between graphite and iron. JOM 2019, 12, 4305–4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimiev, A. M.; Shukhina, K.; Khannanov, A. Mechanism of the graphene oxide formation: The role of water,”reversibility” of the oxidation, and mobility of the C–O bonds. Carbon 2020, 166, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabulonov, Y.L.; Melnychenko, T.I.; Kadoshnikov, V.M.; Odukalets, L.A.; Kuzenko, S.V. A method for producing a magnetically sensitive nanocomposite for the purification of technologically contaminated and radioactive waters containing micro- and nanoplastics and oil products. UA156277U (in Ukrainian), 1: URL: https://sis.nipo.gov.ua/uk/search/detail/1801151/ (accessed on; (accessed on day month year)1801. [Google Scholar]

- Determining the mass related activity of radionuclides. ÄQUIVAL/MASSAKT-01. Procedures Manual for monitoring of radioactive substances in the environment and of external radiation. 2022. ISSN 1865-8725 https://www.bmuv.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Download_PDF/Strahlenschutz/Messanleitungen_2022/aequival_massakt_v2022-03_en_bf.pdf (Accessed 20/08/2025).

- Zabulonov, Y.; Melnychenko, T.; Kadoshnikov, V.; Fedorenko, Y.; Arkhipenko, O.; Molochko, V.; Peer, I.; Bulavin, L. Complex sorbents based on aluminosilicate nanotubes and their application for cleaning radioactively contaminated waters. In: Zabulonov, Y., Peer, I., Zheleznyak, M. (eds) Liquid Radioactive Waste Treatment: Ukrainian Context. LWRT 2023. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, vol 712. Springer, Cham. 2025, pp. 1–13. [CrossRef]

| Fraction, μm | < 1 | 1 – 10 | 10 – 100 | > 100 |

| Sample, % | 20.26 | 13.46 | 62.70 | 3.58 |

| Processing stage | Sorbent used | Radionuclide | Activity, Bq/dm3 |

| Before (initial) | none | 137Cs | 3.3∙107 |

| 90Sr | 4.9∙106 | ||

| After stage 1 | TEG-bentonite nanocomposite | 137Cs | (7.50±0.31) ×103 |

| 90Sr | (1.83±0.28) ×103 | ||

| After stage 2 | Iron hydroxide with nickel-potassium ferrocyanide | 137Cs | (2.24±0.48) ×102 |

| 90Sr | (2.11±0.52) ×102 |

| Radionuclide | Initial activity, Bq/dm3 | Specific activity, Bq/g** | Initial concentration, μg/dm3 | Concentration in RCW, μg/dm3 | |

| after first treatment | after second treatment | ||||

| 137Cs | 3.3∙107 | 3.2×1012 | 10 | 2.4×10-3 | 0.7×10-4 |

| 90Sr | 4.9∙106 | 5.1 ×1012 | 0.96 | 0.36×10-3 | 0.4×10-4 |

| 154Eu | 2.4∙103 | 1.0 ×1012** | 2.4×10-3 | not detected | not detected |

| 241Am | 2.2∙104 | 1.27 x 10¹¹ | 0.17 | not detected | not detected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).