Submitted:

14 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Define Agentic AI and contrast it with generative AI.

- Catalog and analyze its primary applications across the infectious disease continuum—from surveillance to treatment.

- Discuss the critical challenges and risks associated with deploying autonomous agents in high-stakes medical environments.

- Propose future research directions and considerations for the ethical and effective integration of these technologies.

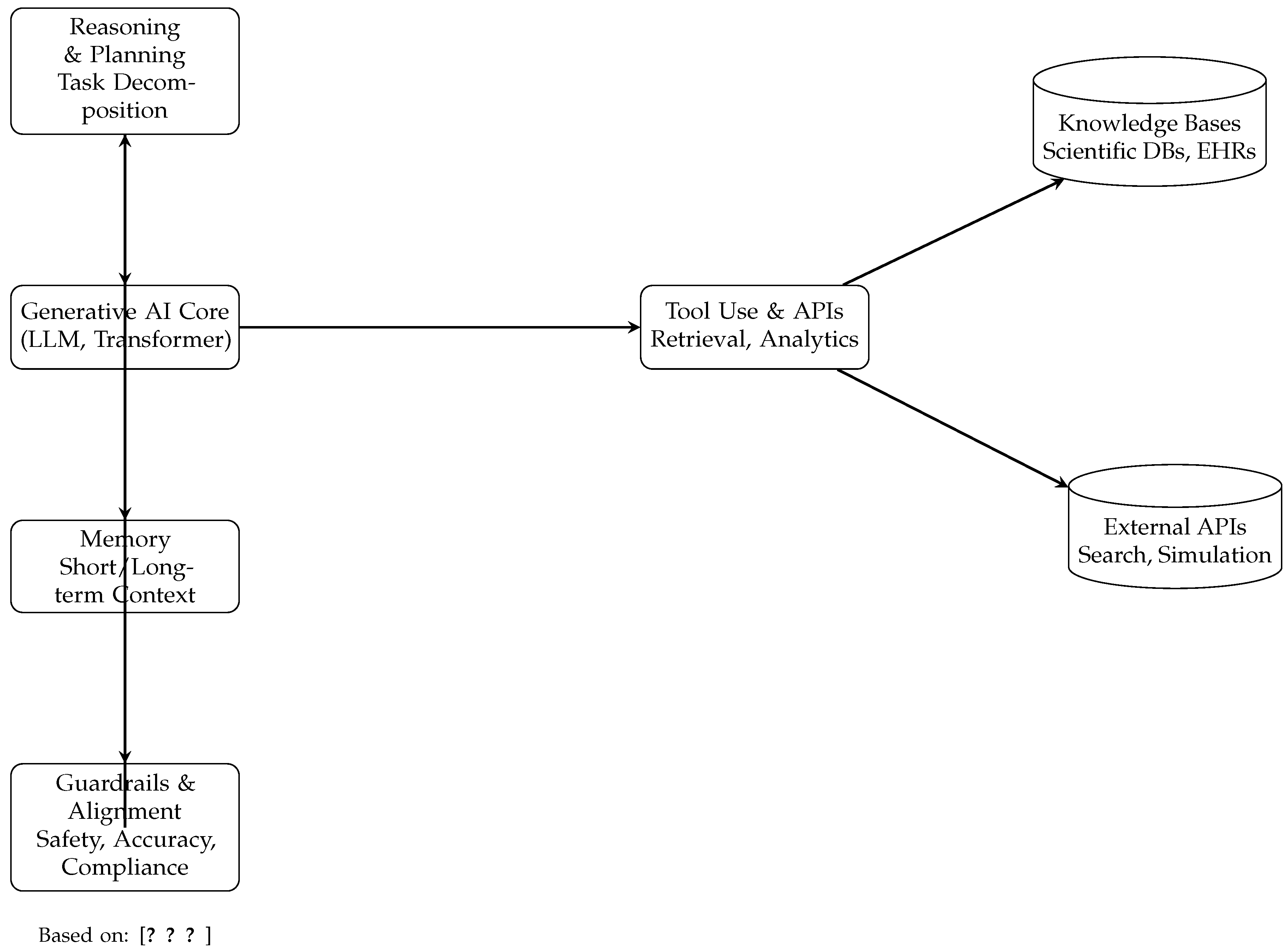

2. From Generative AI to Agentic AI

2.1. Generative AI in Healthcare

2.2. The Agentic AI Paradigm

- Autonomy: Agents can operate with a high degree of independence to achieve a user-defined goal, making decisions without requiring human input for every step.

3. Architecture and Examples of Agentic AI Systems

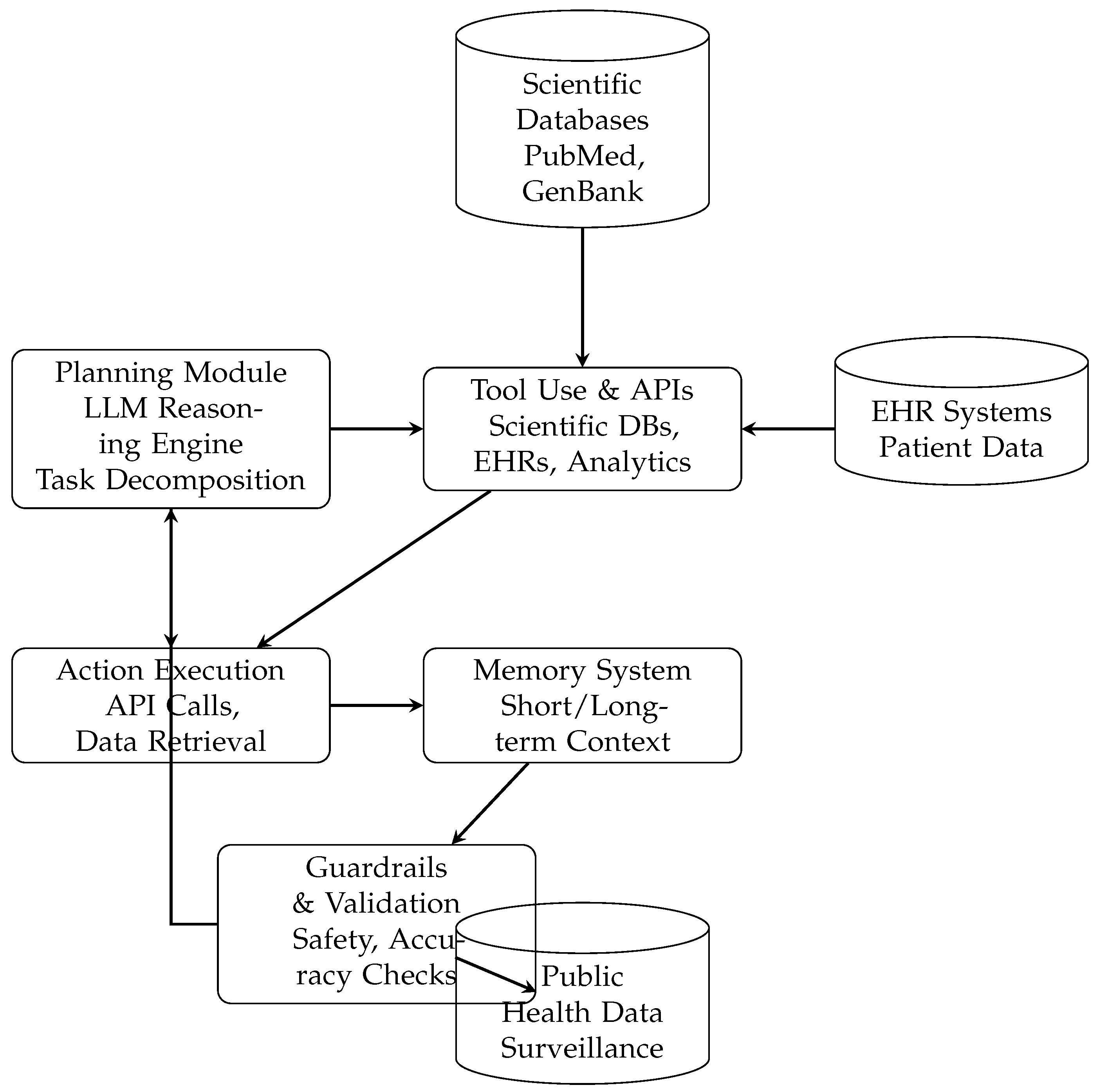

3.1. Core Architectural Components

- Planning Module: This is the core reasoning engine, often a powerful LM like GPT-4 [9], LLaMA, or Gemini. It breaks down a high-level goal into a sequence of actionable subtasks (a "plan"). For example, a goal like "Find the latest research on Omicron BA.5 immune evasion" might be decomposed into: 1) Query PubMed with specific keywords, 2) Filter results by date and relevance, 3) Summarize key findings from the top 5 papers.

-

Tools & APIs: Agents are connected to a suite of external tools that extend their capabilities beyond text generation. Critical tools for infectious disease applications include:

- –

- Scientific Databases: APIs for PubMed, GenBank, PDB, and clinical trial registries.

- –

- –

- Internal Systems: Secure connections to EHRs for data retrieval (e.g., fetching a patient’s lab results) or infection control databases [20].

- Action Execution Unit: This component programmatically calls the required tools based on the plan generated by the LM. It handles authentication, data formatting, and API requests.

- Memory: Agents possess both short-term (within a single session) and long-term memory (across sessions) to maintain context, learn from past actions, and avoid repeating steps. This is crucial for longitudinal tasks like monitoring an outbreak’s progression.

- Guardrails & Validation: Perhaps the most critical component in healthcare, these are predefined rules and validation models that check the agent’s actions and outputs for safety, accuracy, and privacy compliance before they are finalized [15,16]. This helps mitigate hallucination and prevents unsafe actions.

3.2. Notable Platforms and Agent Implementations

- LLaMA (Meta) and Open-Source Agents: While not an agent itself, Meta’s LLaMA series of open-weight models (e.g., LLaMA 2, LLaMA 3) serve as a popular foundation upon which researchers and developers build specialized agents. Their accessibility allows for customization on domain-specific biomedical corpora, enabling the creation of cost-effective agents for tasks like literature review or generating hypotheses from private datasets.

- Oracle OCI Generative AI Agents: Oracle’s cloud platform provides an enterprise-ready environment for building, deploying, and managing AI agents. It emphasizes connecting agents to live organizational data (e.g., lab systems, EHRs) and ensuring responses are grounded in this verified context to improve accuracy, a critical feature for clinical settings [14,15].

- IQVIA AI Agents: Built in collaboration with NVIDIA, IQVIA’s agents are specifically tailored for the life sciences industry. They leverage NVIDIA’s NIM microservices and NeMo Guardrails to create secure, domain-specific agents for applications ranging from clinical data review and target identification to analyzing market landscapes for infectious disease therapeutics [16].

- Causaly Discover: Causaly has announced an "Agentic AI" feature that allows researchers to interact with its vast knowledge base of biomedical literature using natural language. The agent can perform complex, multi-step reasoning to answer questions like "What are biomarkers for sepsis that are modulated by drug X?" by automatically retrieving and synthesizing evidence from millions of publications [26].

- Hippocratic AI’s Healthcare Agents: Focused on patient-facing and operational tasks, these generative AI agents are designed for safety and are being deployed by healthcare systems like WellSpan for applications such as chronic disease education and post-discharge follow-up [27]. This demonstrates a pathway for agentic technology to manage routine tasks, freeing clinical staff for more complex duties.

4. Metrics, Comparison, and Quantitative Fundamentals

4.1. Performance Evaluation Metrics

- Task Success Rate (TSR): The primary metric for any agent is the percentage of times it successfully completes a defined end-to-end task without human intervention. For example, the rate at which it correctly identifies a pathogen from a set of symptoms and lab data and suggests a correct first-line treatment.

-

Process Efficiency Metrics: These measure the agent’s ability to save time and resources.

- –

- Time-to-Insight: Reduction in time required to arrive at a conclusion (e.g., time to generate a outbreak forecast from raw data vs. a human team) [17].

- –

- Cost-per-Task: Computational and operational cost of running the agent for a specific workflow.

- –

- Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) Intervention Rate: The frequency with which a human expert must correct the agent’s plan or output. A lower rate indicates higher autonomy and reliability.

-

Accuracy & Quality Metrics: Domain-specific accuracy remains paramount.

- –

- Forecasting Accuracy: For predictive tasks, standard metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) are used to compare model predictions against ground truth data. Studies have shown generative AI-based forecasting models can achieve significantly lower MAPE values compared to traditional statistical models (e.g., 8.5% vs. 15.2% for COVID-19 case predictions) [25].

- –

- Factual Consistency & Hallucination Rate: Measured by verifying generated text (e.g., a literature summary or diagnostic suggestion) against ground truth sources. The study by Chiu et al. used blinded clinician reviews to score outputs on a Likert scale for factual consistency, finding significant differences between models (GPT-4 outperforming others) [9].

- –

- Comprehensiveness & Coherence: Human-evaluated scores on the completeness and logical flow of the agent’s output [9].

-

Safety & Robustness Metrics:

- –

- Medical Harmfulness Score: The proportion of agent outputs deemed potentially harmful by clinical experts. Alarmingly, studies indicate that fewer than 40% of AI-generated clinical responses may be classified as "harmless" without expert supervision [9].

- –

- Adversarial Robustness: The agent’s resilience to ambiguous, incorrect, or maliciously crafted inputs designed to provoke an erroneous or unsafe action [28].

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Agentic vs. Traditional Approaches

4.3. Theoretical and Quantitative Fundamentals

- Reinforcement Learning (RL) & Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF): The planning modules of advanced agents are often fine-tuned using RLHF, a process where human preferences are used to reward desirable behaviors and penalize undesirable ones (e.g., rewarding concise and accurate answers while penalizing hallucinations). This is fundamental to aligning agent behavior with complex clinical goals.

- Algorithmic Information Theory & Reasoning: The ability to break down tasks relies on concepts of algorithmic complexity. The agent must find the most efficient sequence of actions (or "program") to solve a problem given a set of available tools (APIs).

- Bayesian Reasoning & Uncertainty Quantification: For tasks like diagnosis or forecasting, effective agents must not only provide an answer but also quantify their confidence (e.g., a probability estimate). This allows the human expert to gauge the reliability of the agent’s output. The integration of Bayesian methods into agent frameworks is a critical area of development for clinical safety.

- Graph Theory & Knowledge Representation: The agent’s internal representation of knowledge, especially when integrating data from disparate sources (genomics, EHRs, literature), often relies on graph-based structures (Knowledge Graphs). Navigating and reasoning over these graphs is key to generating insights.

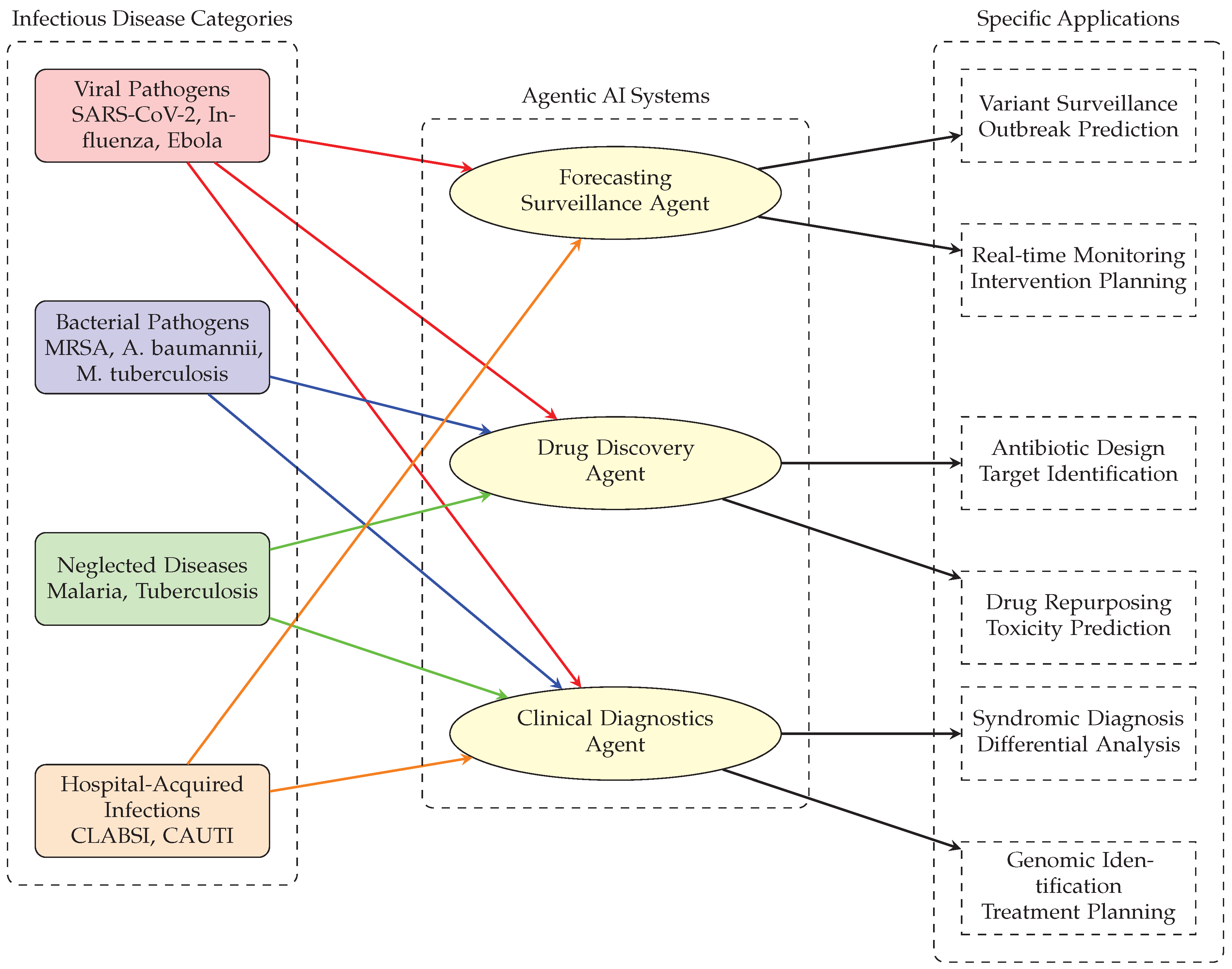

5. Target Pathogens and Agent-Specific Approaches

5.1. Viral Pathogens: Pandemics, Variants, and Antiviral Design

-

RNA Viruses (e.g., SARS-CoV-2, Influenza, Ebola): The high mutation rates of RNA viruses lead to concerning variants and necessitate agile responses.

- –

- Approach: Agents are designed for variant surveillance and predictive modeling. They autonomously ingest global genomic sequence data from platforms like GISAID, identify emerging variants, and forecast their spread and immune evasion potential using advanced models [17,30]. Furthermore, agents leverage generative AI to design broad-spectrum antivirals and predict vaccine targets by modeling viral evolution and protein structures [18,31].

-

Complex Viruses (e.g., HIV): The challenge lies in the virus’s ability to integrate into the host genome and its high diversity.

- –

- Approach: Agents are used to analyze patient-derived genomic data to understand reservoir dynamics and personalize treatment regimens. They also assist in the design of complex immunogens for vaccine development through protein folding predictions and in silico trials [13].

5.2. Bacterial Pathogens: The Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Crisis

-

Drug-Resistant Bacteria (e.g., MRSA, A. baumannii, M. tuberculosis): The pipeline for novel antibiotics is nearly dry.

- –

- Approach: Agentic AI is revolutionizing antibiotic discovery. Agents manage a workflow that involves: 1) Target Identification by analyzing bacterial genomes and essential pathways [26], 2) Generative Chemistry to design novel molecules that inhibit these targets while avoiding existing resistance mechanisms [19,29,32], and 3) Prioritization of candidates for synthesis based on predicted efficacy and toxicity [33,34]. This approach has already yielded promising new antibiotic candidates against priority pathogens.

5.3. Neglected Tropical Diseases and Fungal Pathogens

- Approach: For pathogens like those causing malaria, tuberculosis, and certain fungal infections, agents perform knowledge mining from disparate, often outdated, literature sources to propose novel drug repurposing strategies [21,35]. They can also integrate heterogeneous clinical data from low-resource settings to identify risk factors and optimize intervention strategies, helping to overcome the data scarcity challenge [22].

5.4. Hospital-Acquired Infections (HAIs) and Infection Control

- Approach: Here, agents function as continuous surveillance systems. They are integrated directly with EHRs and lab systems to monitor patient data in real-time. Using natural language processing, they parse clinical notes for signs of infection (e.g., "fever," "redness at catheter site") and combine this with lab culture results to automatically flag potential HAIs much earlier than manual chart reviews allow [20]. This enables pre-emptive intervention by infection control teams.

5.5. The Diagnostic Challenge: Syndromic and Genomic Identification

- Approach: AI agents are being developed as diagnostic coordinators. For syndromic presentation, they can integrate patient-reported symptoms, travel history, and vital signs to suggest a differential diagnosis and recommend specific tests [36]. For genomic identification, agents can analyze raw data from next-generation sequencers in real-time, compare sequences against genomic databases (e.g., NCBI, proprietary pathogen libraries), and provide a definitive identification of the pathogen, often including AMR markers [12,37]. This is particularly powerful for detecting novel or unexpected pathogens.

6. Key Applications of Agentic AI in Infectious Diseases

6.1. Disease Surveillance, Forecasting, and Outbreak Response

- Advanced Forecasting: New AI tools, leveraging the architectural advances behind LLMs, are demonstrating superior performance in predicting the spread of diseases like COVID-19, outperforming state-of-the-art statistical and machine learning models [17,25,30,39]. An agent can autonomously run these forecasts, update them with incoming data, and generate reports for public health officials.

6.2. Accelerating Drug Discovery and Development

6.3. Clinical Diagnostics and Decision Support

- Treatment Planning: By analyzing local antibiograms and patient history, agents can recommend personalized antibiotic regimens, aiding in the fight against antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [47].

- Operational Efficiency: Agents can automate infection control surveillance, such as monitoring for hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) like central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs), ensuring compliance and early detection [20].

6.4. Automated Scientific Research and Knowledge Synthesis

- Literature Review: Agents can be tasked with finding, summarizing, and connecting findings across thousands of papers to generate hypotheses about disease mechanisms or repurpose existing drugs [6].

- Experimental Design: More advanced agents can propose novel experimental protocols or clinical trial designs based on the current state of knowledge [48].

- Viral Evolution Prediction: Agents can model and predict the evolutionary trajectory of viruses, a critical capability for developing broadly effective vaccines and staying ahead of new variants [18].

7. Challenges and Limitations

7.1. Data Quality and Bias

7.2. Hallucination and Factual Inconsistency

7.3. The “Black Box” Problem and Lack of Interpretability

7.4. Security and Propagation of Risks

7.5. Regulatory and Ethical Hurdles

8. Discussion

9. Future Directions

- Development of Robust Evaluation Frameworks: There is an urgent need for standardized benchmarks to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and reliability of AI agents in simulated and real-world clinical environments [51].

- Human-AI Collaboration Models: The most effective near-term use cases will likely be agent-assisted rather than fully autonomous. Research should focus on designing intuitive interfaces that allow clinicians to supervise, steer, and easily correct agents [52].

- Specialized and Modular Agents: Instead of monolithic systems, the future may lie in a ecosystem of specialized, interoperable agents (e.g., a “diagnosis agent,” a “literature agent,” a “treatment agent”) that can be composed for specific tasks [24].

- Focus on Sustainability and Equity: Efforts must be made to ensure these powerful tools do not exacerbate global health inequities. Developing cost-effective solutions that can be deployed in low-resource settings is crucial for global health security [22].

10. Open-Source and Chinese Generative AI Agents in Infectious Disease Research

10.1. The Open-Source Ecosystem as an Enabler

10.2. The Chinese AI Landscape in Healthcare

- Major Research Collaborations: Chinese institutions are active in high-profile international collaborations. A key example is the partnership between the Global Health Drug Discovery Institute (GHDDI) in Beijing and Microsoft Research AI4Science [13]. This collaboration uses AI (likely leveraging a combination of proprietary and custom models) to accelerate drug discovery for infectious diseases like tuberculosis, representing a significant contribution from China to the global fight against neglected diseases.

- Domestic Research and Development: While not detailing specific Chinese LLMs, the bibliography points to robust domestic activity. The clinical study by Chiu et al. is from Hong Kong, and its rigorous evaluation framework for generative AI models in infectious disease consultations exemplifies the high caliber of research being conducted within the Chinese scientific ecosystem [9,10].

- Strategic Focus on Precision Medicine: Research involving the interpretation of immune biomarker data from Electronic Health Records (EHRs) using generative AI aligns with China’s broader strategic focus on precision medicine [45]. This suggests a national research priority where AI agents are seen as key to parsing complex biomedical data for personalized treatment strategies, including for infectious diseases.

10.3. Analysis and Implications

- Open-Source Absence: The lack of direct citation of open-source models like LLaMA suggests that the most cutting-edge clinical and commercial applications documented in the literature (as of the papers’ publication dates) are still relying on the leading proprietary, closed models (e.g., GPT-4) for their superior performance and reliability in high-stakes scenarios.

- Chinese Model Development: While specific Chinese LLMs (e.g., ERNIE, Qwen, ChatGLM) are not named, China’s contribution is evident through its research output, institutional collaborations, and focus on solving large-scale public health problems. The country is building substantial capacity and is likely developing and utilizing its own suite of foundational models tailored to Chinese language data and domestic healthcare priorities.

- A Multipolar Future: The landscape is evolving towards a multipolar world of AI development. The future of Agentic AI in infectious diseases will likely involve a mix of proprietary Western models, open-source alternatives, and competitively advanced Chinese models, each serving different segments of the global market and research community.

11. Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bharel, M.; Auerbach, J.; Nguyen, V.; DeSalvo, K.B. Transforming Public Health Practice With Generative Artificial Intelligence. Health Affairs 2024, 43, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischler, D. Artificial Intelligence Is Leveling Up the Fight Against Infectious Diseases, 2023.

- Alterovitz, G.; Alterovitz, W.L.; Cassell, G.H.; Zhang, L.; Dunker, A.K. AI for Infectious Disease Modelling and Therapeutics. In Proceedings of the Biocomputing 2021, Kohala Coast, Hawaii, USA; 2020; pp. 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AI Agents — What They Are, and How They’ll Change the Way We Work.

- Why AI Agents Are the next Frontier of Generative AI | McKinsey. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/ mckinsey-digital/our-insights/why-agents-are-the-next-frontier-of-generative-ai.

- Accelerating Scientific Breakthroughs with an AI Co-Scientist. Available online: https://research.google/blog/accelerating-scientific-breakthroughs-with-an-ai-co-scientist/.

- Anthony, J. Generative AI in Healthcare: Its Uses and Challenges, 2024.

- Nucci, A. Generative AI in Healthcare: Use Cases and Challenges, 2023.

- Chiu, E.K.Y.; Tam, A.R.; Choi, M.H.; Chung, T.W.H.; Wong, W.C.; Wong, S.S.Y.; Ng, Y.Z.; Sridhar, S.; Yuen, K.Y.; Lau, A.W.T.; et al. Generative Artificial Intelligence Models in Clinical Infectious Disease Consultations: A Cross-Sectional Analysis Among Specialists and Resident Trainees. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, E.K.Y.; Sridhar, S.; Wong, S.S.Y.; Tam, A.R.; Choi, M.H.; Lau, A.W.T.; Wong, W.C.; Chiu, K.H.Y.; Ng, Y.Z.; Yuen, K.Y.; et al. Generative Artificial Intelligence Models in Clinical Infectious Disease Consultations: A Cross-Sectional Analysis among Specialists and Resident Trainees, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S. Agent AI vs Generative AI: A Deep Dive into AI Technologies, 2025.

- Biotia: Fighting Infectious Diseases, Powered by Genomics + AI. Available online: https://www.biotia.io/.

- Hughes, A. GHDDI and Microsoft Research AI4Science Use AI Technology to Achieve Significant Progress in Discovering New Drugs to Treat Global Infectious Diseases, 2024.

- Announcing the General Availability of OCI Generative AI Agents Platform. Available online: https://blogs.oracle.com/ai-and-datascience/post/ga-of-oci-gen-ai-agent-platform.

- Behind the Scenes: Using OCI Generative AI Agents to Improve Contextual Accuracy. Available online: https://blogs.oracle.com/cloud-infrastructure/post/behind-the-scenes-with-generative-ai-agents.

- IQVIA Launches New AI Agents for Life Sciences and Healthcare. Available online: https://www.iqvia.com/newsroom/2025/ 06/iqvia-launches-new-ai-agents-for-life-sciences-and-healthcare.

- Hopkins, J. AI Tool Predicts Disease Outbreaks Using ChatGPT Technology, 2025.

- Pasquini, N. Using Generative AI to Predict Viral Mutations and Develop Vaccines | Harvard Magazine. 2024. Available online: https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2024/11/ai-medicine-predicting-viral-evolution-vaccines.

- Using Generative AI, Researchers Design Compounds That Can Kill Drug-Resistant Bacteria. 2025. Available online: https://news.mit.edu/2025/using-generative-ai-researchers-design-compounds-kill-drug-resistant-bacteria-0814.

- Generative AI May Enhance Healthcare-Associated Infection Surveillance | TechTarget. Available online: https://www.tech target.com/healthtechanalytics/news/366590029/Generative-AI-may-enhance-healthcare-associated-infection-surveillance.

- From Data to Discovery: How AI Agents Are Shaping Medical Research. Available online: https://www.akira.ai/blog/ai-agents-for-medical-research.

- Bose, S. AI’s Role in Public Health and Infectious Diseases, 2024.

- How AI Can Help Health Departments Monitor Infectious Disease Outbreaks. 2025. Available online: https://www.healthbeat.org/ 2025/07/01/artificial-intelligence-infectious-disease-outbreaks/.

- Boost, G.C.S. GenAI and Virtual Agents - GenAI and Conversational Agents. Available online: https://www.cloudskillsboost. google/paths/371/course_templates/1108/video/492772.

- Liang, Z.; Liang, G.; Kuang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liang, Z.; Liang, G.; Yun, K.; Li, Z. Application and Comparative Study of Generative Artificial Intelligence for Epidemic Prediction of Coronavirus Disease. Cureus 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causaly Announces Agentic AI for Scientific Discovery - Causaly. Available online: https://www.causaly.com/news/causaly-announces-agentic-ai-for-scientific-discovery.

- WellSpan One of the First to Launch Hippocratic AI’s Generative AI Healthcare Agent. Available online: https://www.wellspan.org/articles/2024/09/web—hippocratic-ai-launch.

- As AI Agents Spread, so Do the Risks, Scholars Say. Available online: https://www.zdnet.com/article/as-ai-agents-spread-so-do-the-risks-scholars-say/.

- Pappas, P. AI Can Now Imagine Antibiotics We Never Could, 2025.

- Bioengineer. Revolutionizing Infectious Disease Forecasting with Advanced AI Technology, 2025.

- Roy, D. Generative AI Revolutionizes Antibody Therapies Against Viruses, Including COVID-19 And Ebola, 2023.

- Medicine, S. Generative AI Revolutionizes Antibiotic Development against Resistant Pathogens. 2024. Available online: https://www.news-medical.net/news/20240328/Generative-AI-revolutionizes-antibiotic-development-against-resistant-pathogens.aspx.

- Genentech. AI and the Quest for New Antibiotics. Available online: https://www.gene.com/stories/ai-and-the-quest-for-new-antibiotics.

- HHS Funds AI-enhanced Antibiotic Discovery Project | CIDRAP. 2024. Available online: https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/antimicrobial-stewardship/hhs-funds-ai-enhanced-antibiotic-discovery-project.

- Sokolova, B. 9 Companies Using Artificial Intelligence to Fight Infectious Diseases. 2022. Available online: https://www.biopharma trend.com/artificial-intelligence/9-companies-using-artificial-intelligence-to-fight-infectious-diseases-589/.

- AI Agents in Healthcare: Benefits, Use Cases, Future Trends | SaM Solutions. Available online: https://sam-solutions.com/blog/ai-agents-in-healthcare/.

- New AI Technology Can Detect Infections Early and Save Lives | Karolinska Institutet. 2025. Available online: https://news.ki.se/new-ai-technology-can-detect-infections-early-and-save-lives.

- for Healthbeat, D.J.K.V. How AI Can Make Infectious Disease Surveillance Smarter, Faster, and More Useful. 2025. Available online: https://www.wftv.com/news/how-ai-can-make-infectious-disease-surveillance-smarter-faster-more-useful/2TRXO2QSCVMCVCIPXJYONMQ7RE/.

- Artificial Intelligence Reimagines Infectious Disease Forecasting | PreventionWeb. 2025. Available online: https://www.prevention web.net/news/artificial-intelligence-reimagines-infectious-disease-forecasting.

- By. Harnessing AI to Model Infectious Disease Epidemics | Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 2025.

- AI Agents for Infectious Disease Management | Bluebash. Available online: https://www.bluebash.co/services/artificial-intelligence/ai-agents/infectious-disease-management.

- AI Medicines Are Coming: Building the Foundations for Discovery’s next Era. Available online: https://pharmaphorum.com/ deep-dive/ai-medicines-are-coming-building-foundations-discoverys-next-era.

- Digital Transformation and Artificial Intelligence | Sanofi. Available online: https://www.sanofi.com/en/our-science/digital-artificial-intelligence.

- PhD, J.D.G. Drug-Resistant Bacteria Stymied by AI-Designed Antibiotics, 2024.

- Shiwlani, A.; Kumar, S.; Qureshi, H.A. Leveraging Generative AI for Precision Medicine: Interpreting Immune Biomarker Data from EHRs in Autoimmune and Infectious Diseases. Annals of Human and Social Sciences 2025, 6, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How Does Generative AI Contribute to Early Disease Detection? - Ambilio. Available online: https://ambilio.com/how-does-generative-ai-contribute-to-early-disease-detection/.

- ID Is Having a `Wild West Moment’ with AI. Available online: https://www.healio.com/news/infectious-disease/20240401/id-is-having-a-wild-west-moment-with-ai.

- Research Assistant - Bohrium | AI for Science with Global Scientists. Available online: https://www.bohrium.com/paper-details/generative-artificial-intelligence-models-in-clinical-infectious-disease-consultations-a-cross-sectional-analysis-among-specialists-and-resident-trainees/1033599860797866026-98026.

- IQVIA Healthcare-grade AI®. Available online: https://www.iqvia.com/solutions/innovative-models/artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning.

- Trang, B. AI Agents in Health Care: Everything You Need to Know, but Didn’t Know How to Ask, 2025.

- The VR Hype Cycle: Lessons for the Age of AI. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/vr-hype-cycle-lessons-for-ai/.

- Takyar, A. AI Agents for Healthcare: Applications, Benefits and Implementation, 2024.

| Pathogen Category | Primary Challenges | Agentic AI Approach |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Viruses (e.g., SARS-CoV-2) | Rapid mutation, variant emergence, pandemic spread | Variant surveillance, predictive forecasting, antiviral & vaccine design |

| Drug-Resistant Bacteria | Dried-up antibiotic pipeline, complex resistance mechanisms | De novo antibiotic design, target identification, drug repurposing |

| Neglected Diseases | Data scarcity, limited R&D funding | Knowledge mining from literature, data integration from low-resource settings |

| Hospital-Acquired Infections | Preventable, requires real-time surveillance | Automated EHR monitoring, real-time alerting for infection control |

| General Diagnostic | Rapid and accurate pathogen identification | Syndromic diagnostic support, genomic sequence analysis and identification |

| Task | Manual / Traditional Software | Non-Agentic AI (Generative Chatbot) | Agentic AI System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Literature Review for Drug Repurposing | Weeks of researcher time; potential for human error. | Can summarize a single paper but cannot perform end-to-end review across databases. | Hours; autonomously queries multiple DBs, synthesizes findings, generates a report with citations. [21] |

| Infectious Disease Forecasting | Relies on static statistical models (e.g., ARIMA) requiring expert configuration. | Not applicable for full forecasting pipeline. | Autonomously ingests latest data, runs and compares models, generates and disseminates reports. Superior accuracy (lower MAE/MAPE) [25]. |

| Antibiotic Discovery | Years; high-throughput screening is costly and slow. | Can generate molecular structures but cannot validate or prioritize them. | Designs novel compounds in silico, predicts efficacy/toxicity, and prioritizes candidates for synthesis in weeks/months [19,29]. |

| HAI Surveillance | Retrospective manual chart reviews; slow, prone to missing cases. | Can analyze text in EHRs but cannot act on findings. | Real-time monitoring of EHRs; automatically flags potential cases to infection control practitioners [20]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).