1. Introduction

Wildfires have emerged as one of the most destructive natural disasters worldwide, causing significant economic losses and long-term ecological damage. It is estimated that only a small percentage of wildfires, typically between 3% and 5%, exceed 100 hectares in size. Yet, these larger fires are responsible for 80% to 96% of the total area burned [

1]. The term “megafire” reflects the unprecedented size, impact, and severity of recent wildfires, a trend driven by changing climate patterns and aggressive fire suppression strategies. Climate change has led to more frequent and severe weather events, prolonged droughts, changes in vegetation patterns, and increased fuel loads, making fire behaviour more unpredictable and variable [

2]. The impacts of wildfires extend beyond the destruction of lives, homes, businesses, and infrastructure, also affecting wildlife, forests, crops, soil stability, and air quality [

3].

Human actions like building homes near forests, leaving campfires unattended, or starting fires on purpose can cause wildfires, while natural causes include lightning strikes during hot, dry weather, with fire risk shaped by terrain, available plants, and weather conditions [

4]. Certain regions are particularly susceptible to wildfires due to their arid conditions and high temperatures, while others experience strong winds that can rapidly spread flames.

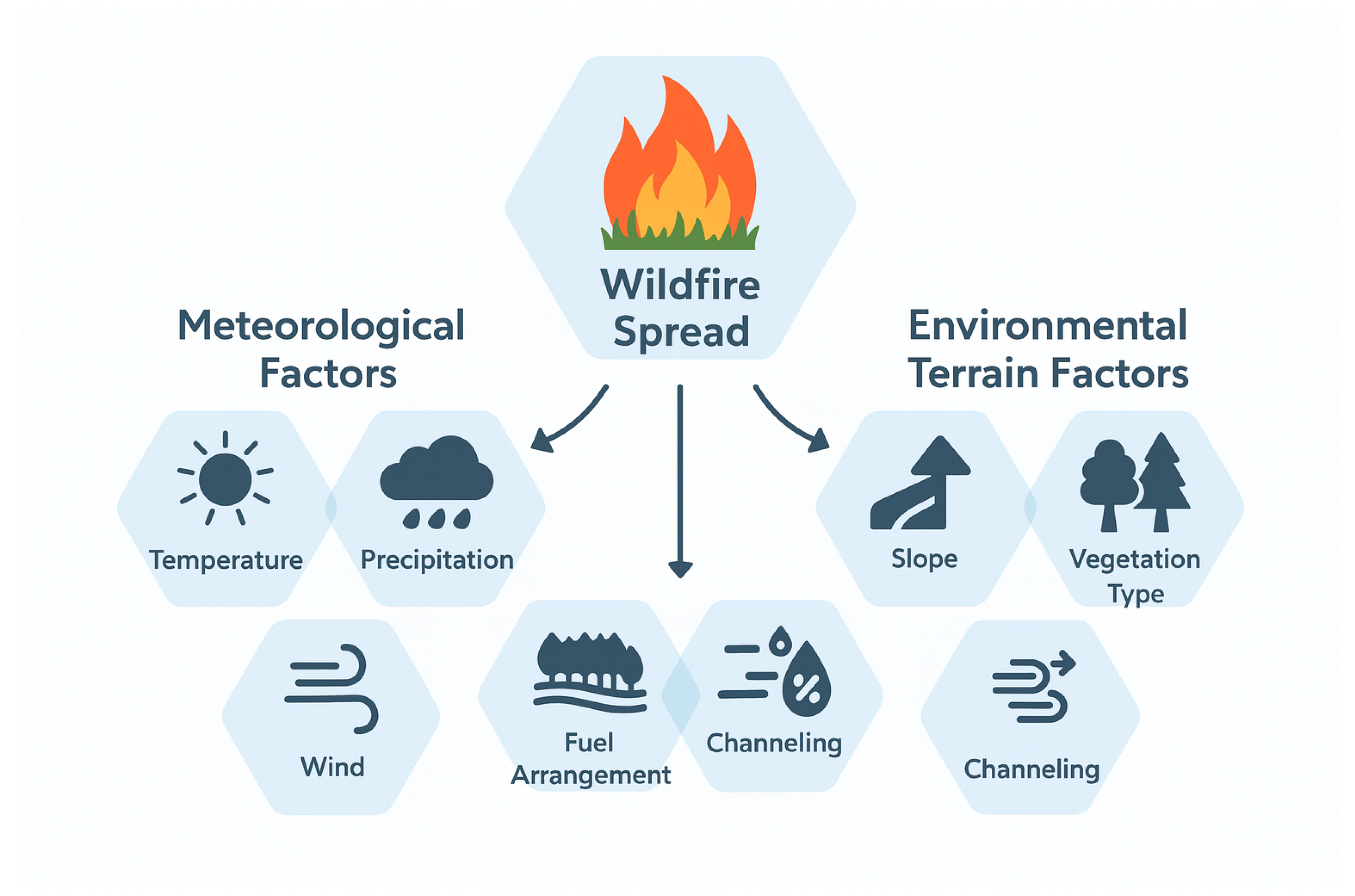

Figure 1 summarises the primary factors influencing wildfire spread, dividing them into meteorological factors (temperature, precipitation, wind, fuel arrangement, channelling) and environmental terrain factors (slope, vegetation type, channelling). These interconnected elements determine the likelihood, speed, and direction of wildfire propagation.

As wildfire behaviour becomes increasingly complex due to climate change and change environmental conditions [

5,

6] there is a growing need for advanced predictive models that can accommodate these dynamic factors [

7]. Early detection, prediction, and forecasting of fires are critical, as traditional systems often fail to detect fires quickly and accurately, resulting in delayed responses and substantial damage [

8,

9].

Recent advances leverage machine learning, which uses sophisticated algorithms and large datasets to improve detection speed and accuracy [

10,

11]. Vision-based techniques further enhance these systems by enabling the interpretation of visual cues, such as smoke or flames, similar to human observation [

12,

13].

The exacerbation of wildfire behaviour is closely linked to climate change, which brings more frequent and severe weather events, prolonged droughts, changes in vegetation patterns, and increased fuel loads [

2]. Understanding and predicting wildfire spread is critical due to its potentially devastating effects on the environment, human life, and property [

3,

14].

1.1. Current Trends and Challenges

Recent advances in wildfire detection and prediction have focused on integrating remote sensing and satellite imagery with machine learning algorithms. Multispectral and hyperspectral data enable large-scale, minute-level fire monitoring and burned area mapping, especially when combined with advanced deep learning models such as recursive Transformers and optical flow techniques [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Deep learning architectures, including U-Net and decision-level super-resolution models, outperform traditional methods, especially when fusing multispectral and SAR data [

20,

21]. Benchmark datasets such as EO4WildFires and Sen2Fire further support model evaluation and generalisation across diverse regions by addressing the challenge of limited annotated data [

22,

23].

Despite these technological advances, challenges persist. Data quality, availability, and the need for advanced processing capabilities to manage large datasets remain significant issues. Satellite-based methods face difficulties in detecting small fires, dealing with cloud and smoke occlusion, and ensuring model transferability across different regions [

5,

18,

24]. However, integrating contextual and structural features into machine learning models has improved generalisation across varied environmental conditions and fire intensities [

25].

The deployment of IoT devices and sensor networks is another major trend, enhancing real-time detection and early warning capabilities. IoT-based wireless sensor networks (WSNs) and energy-optimized frameworks have improved network stability and energy efficiency [

26]. Integrating physical and virtual sensors in WSNs enhances prediction accuracy and scalability, supporting early warning and fire scenario classification [

27]. However, these systems are often limited by power constraints, limited connectivity in remote areas, and data processing capabilities [

8,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Advances in energy-harvesting, efficient algorithms, and edge or fog computing are being developed to extend device lifespan and reliability [

32,

33,

34].

Environmental variability, driven by climate change, complicates fire risk prediction. Shifts in weather patterns, diverse vegetation types, and complex terrains challenge model accuracy, especially when models rely on historical climate data [

5,

6,

22,

35,

36,

37]. Poor air quality and reduced visibility due to smoke or fog can also impede the effectiveness of optical sensors and satellite imagery, leading to detection failures [

38]. The use of additional data sources, such as Sentinel-5P aerosol products, and the fusion of meteorological, topographic, and vegetation data are helping to mitigate some of these environmental challenges [

22,

23].

From a methodological perspective, model complexity and interpretability are key concerns. Deep learning models can be difficult to interpret, making it challenging to understand the prediction rationale [

20,

39,

40]. Data privacy and security are also critical, particularly with federated learning approaches that enable decentralised model training but introduce challenges related to heterogeneous data and communication overhead [

41,

42].

Lastly, models may not adapt well to new conditions, such as novel fire types or unusual weather patterns, leading to decreased performance over time [

43,

44]. The scarcity of annotated datasets, especially for early-stage fires and diverse geographies, remains a persistent obstacle. Techniques such as transfer learning, data augmentation, and the development of benchmark datasets are being explored to address these gaps [

20,

40,

45].

To address these challenges, researchers are exploring innovative, nature-inspired approaches. One promising direction involves leveraging bees’ sensitivity to environmental changes. Our prior work introduced how bees are sensitive and can show different behaviours in response to environmental changes. As naturally sensitive creatures, bees respond to subtle environmental shifts, and their behavioral patterns, particularly acoustic signals may correspond to changes in factors such as temperature, humidity, and vegetation. Exploring these relationships offers valuable insights into potential early indicators of environmental conditions linked to wildfire risk.

This paper aims to conduct a systematic literature review examining the relationship between environmental factors contributing to wildfires and the behavioural responses of bees, focusing on acoustic behaviour. By exploring this novel approach, we aim to contribute to developing innovative, nature-inspired methods for early wildfire detection and prediction, leveraging the sensitivity of bees to environmental changes as a potential indicator of impending wildfires.

1.2. Structure of the Paper

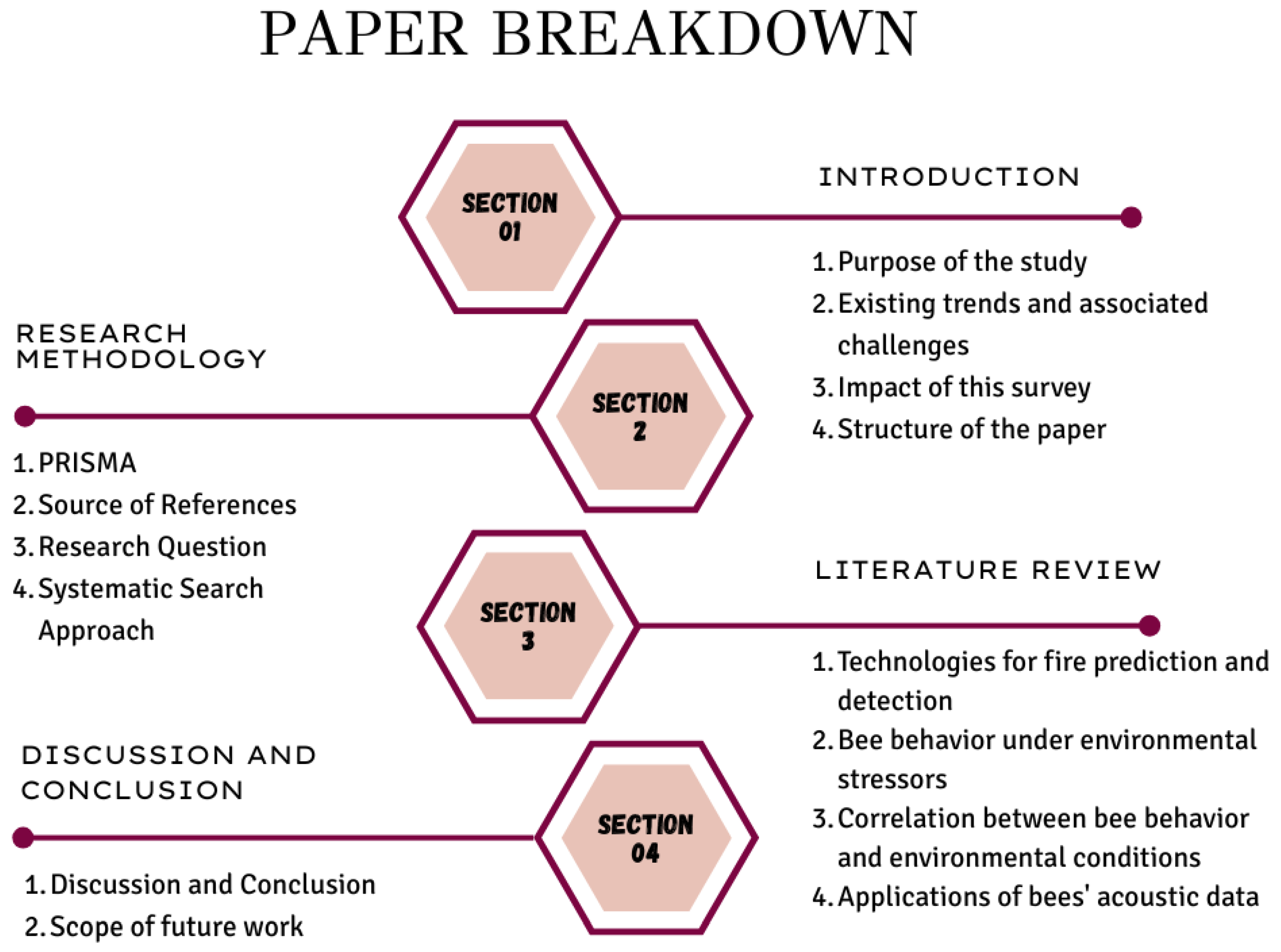

This paper’s organisation is summarised in

Figure 2.

Section 1 introduces the study by outlining its purpose, reviewing existing trends and challenges, highlighting the impact of this survey, and presenting the overall structure of the work.

Section 2 details the research methodology, including the application of PRISMA guidelines, the sources of references, formulation of the research question, and the systematic search approach employed.

Section 3 presents the literature review, covering fire prediction and detection technologies, bee behaviour under environmental stressors, the correlation between bee behaviour and environmental conditions, and the applications of bees’ acoustic data. Finally,

Section 4 offers a discussion and conclusion, addressing the main findings and suggesting potential directions for future research.

4. Synthesis of Challenges, Emerging Directions, and Nature-Inspired Innovations in Wildfire Prediction

Recent advancements in wildfire detection and prediction have focused on integrating remote sensing and satellite imagery with machine learning algorithms. Multispectral and hyperspectral data are being used for fire detection and monitoring, enabling large-scale surveillance [

14,

15,

16]. The use of multisource satellite data, such as Himawari-8/9, MODIS, Sentinel-1/2/3 / 2/3, and VIIRS - combined with advanced deep learning models such as recursive Transformers and optical flow - has greatly improved the speed and accuracy of wildfire monitoring and burned area mapping, allowing for minute-level detection and better temporal up-sampling [

17,

18,

19]. Deep learning architectures, including U-Net and decision-level super-resolution models, outperform traditional methods, especially when fusing multispectral and SAR data [

20,

21]. Benchmark data sets such as EO4WildFires and Sen2Fire further support the evaluation and generalization of the model in diverse regions by addressing the challenge of limited annotated data [

22,

23].

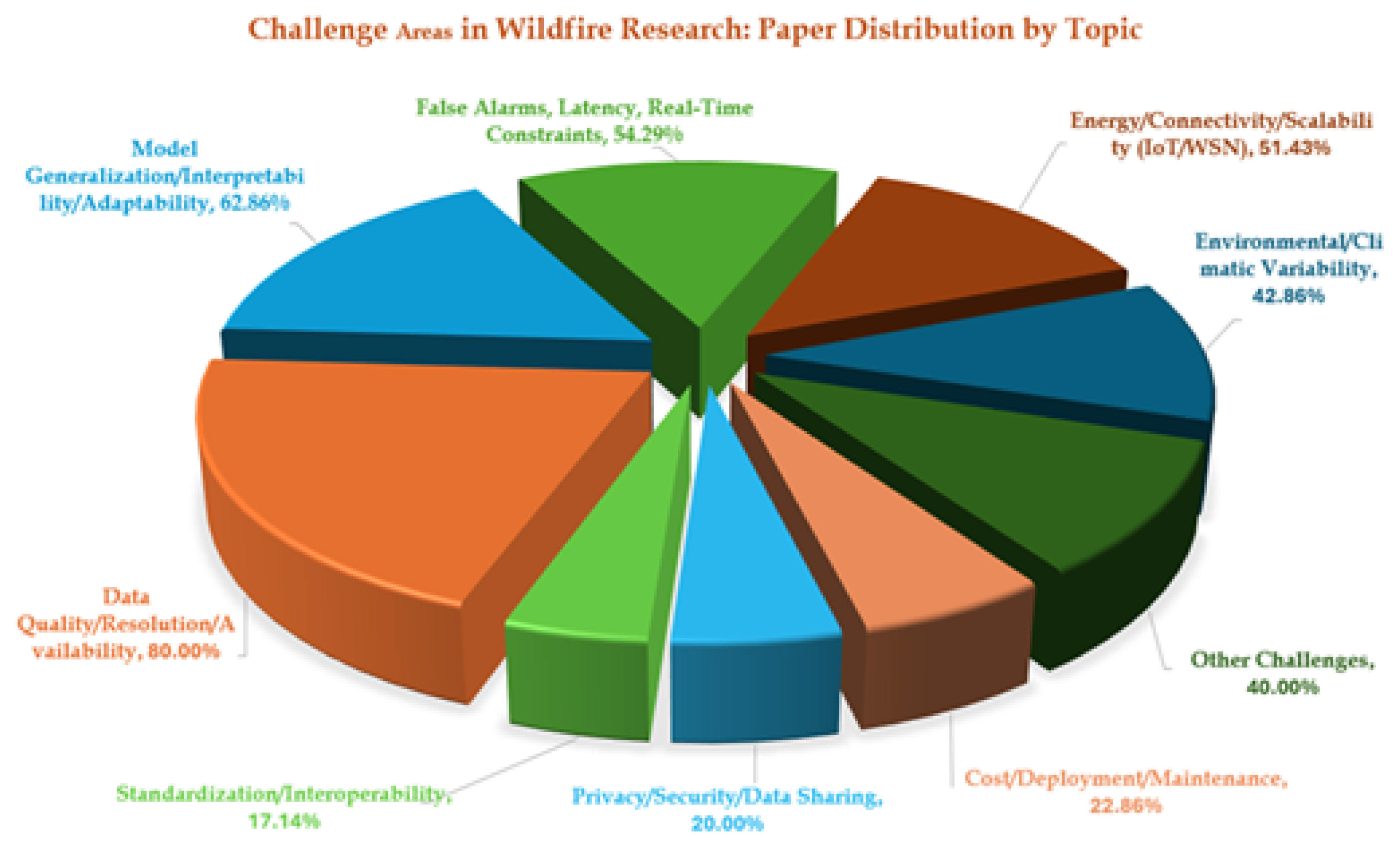

However, as illustrated in

Figure 8, the field faces a spectrum of technological and methodological challenges. The pie chart visually summarizes the prevalence of key challenges discussed in the literature. The most dominant concern, reflected in 80% of the reviewed studies, is data quality, resolution, and availability. This includes issues such as satellite image resolution, cloud cover, and the scarcity of annotated datasets, all of which hinder early detection capabilities. Model generalization, interpretability, and adaptability are the next most cited challenges (62.86%), with many studies noting that deep learning models, while powerful, are often complex and lack transparency, which can impede trust and practical deployment. False alarms, latency, and real-time constraints are also significant, discussed in 54.29% of the literature, as high false positive rates and detection delays can strain emergency resources and reduce the effectiveness of rapid response.

Energy, connectivity, and scalability issues within IoT and wireless sensor networks are highlighted in 51.43% of the studies, emphasising the difficulties of maintaining reliable, energy-efficient networks in remote or rugged environments. Environmental and climatic variability, including the impacts of changing weather patterns, diverse vegetation, and complex terrain, is addressed in 42.86% of the references, underscoring the need for models that can adapt to dynamic and heterogeneous conditions. Other challenges, such as false negatives, environmental interference (e.g., smoke, fog), and algorithmic complexity, are noted in 40% of the studies. Cost, deployment, and maintenance issues are discussed in 22.86% of the literature, particularly regarding the high expenses associated with deploying and maintaining extensive sensor or satellite networks. Privacy, security, and data sharing concerns—especially in the context of federated learning and cross-agency collaboration—are raised in 20% of the references, while standardization and interoperability issues, which hinder the integration and comparison of different systems and datasets, are discussed in 17.14% of the studies.

The diversity of data sources and environmental variables is a defining feature of contemporary wildfire research, as illustrated in

Figure 9. The main categories identified include:

Machine Learning & Deep Learning (26%), which covers image-based detection approaches like CNNs and YOLO, as well as transfer and reinforcement learning applied to satellite, drone, or sensor data [

40,

41,

53];

Remote Sensing & Satellite Imagery (18%), utilizing multispectral/hyperspectral analysis and data fusion from platforms such as MODIS and Sentinel satellites for fire detection and mapping [

17,

21,

58];

IoT & Sensor Networks (15%), which employ wireless sensor networks to monitor environmental parameters like temperature, humidity, and CO

2 [

26,

79];

Emerging Technologies (17%), including digital twins, explainable AI, and quantum computing [

72,

84];

UAVs/Drones & Multi-Modal Learning (12%), integrating drone-mounted sensors and multi-modal data for real-time monitoring [

52,

71,

74]; and

Environmental & Climate Factors (12%), focusing on climate modeling, vegetation, fuel loads, and drought indices [

22,

36,

85]. This multi-faceted approach reflects the field’s emphasis on leveraging a wide range of data and analytical techniques to enhance the accuracy and robustness of wildfire prediction and detection systems.

A closer look at the environmental and climate factors reveals a sophisticated integration of weather variables (temperature, precipitation, wind, humidity, drought), climate variability, vegetation patterns, fuel loads, vapour pressure deficit, soil moisture, large-scale circulation patterns, and more.

Table 2 summarizes the environmental and climate variables studied in the literature, along with their research focus and representative references.

As per the literature, CO

2 fertilization, vegetation growth, and climate-fuel interactions are increasingly studied in the context of climate change. Recent studies show that elevated CO

2 levels can enhance plant growth, leading to increased fuel loads and, consequently, more severe and frequent wildfires [

36,

85,

100]. These interactions highlight the need for predictive models that account for both direct climate effects (e.g., temperature, drought) and indirect effects (e.g., fuel accumulation, vegetation productivity) on fire regimes. This is reflected in the growing share of studies focusing on environmental and climate factors, as shown in

Figure 9.

Future research should prioritise several key areas to advance the field of wildfire prediction and early detection. First, multimodal data integration is essential; combining data from satellites, ground-based sensors, meteorological sources, and innovative bio-indicators such as bee acoustics can significantly enhance the accuracy and timeliness of early warning systems. This integrative approach enables a more comprehensive assessment of wildfire risk by capturing complex environmental interactions that single-source data may overlook.

Second, the development of advanced machine learning models and explainable artificial intelligence (AI) should be emphasised. Highly accurate and interpretable models will facilitate actionable insights for fire managers and policymakers, increasing trust and enabling more effective decision making in operational settings.

Third, there is substantial promise in nature-inspired sensing, particularly through bio-indicators like bees. Investigating bees’ behavioural and acoustic responses to environmental changes offers a novel avenue for detecting precursors to wildfire events. Such approaches may provide earlier and more sensitive risk indicators, especially in ecosystems where traditional technological monitoring faces limitations.

By addressing these directions, future research can contribute to the development of more holistic, adaptive, and robust wildfire prediction frameworks, ultimately mitigating wildfires’ ecological and societal impacts.

Despite considerable progress in wildfire prediction—driven by advances in machine learning, remote sensing, and IoT sensor networks—persistent challenges remain, as illustrated in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. Key limitations include data quality and availability, model generalization, latency, environmental variability, and the scalability of sensor networks. These hurdles highlight the need for innovative and complementary approaches that can provide early and sensitive indicators of wildfire risk.

One promising direction is the use of nature-inspired bioindicators. Bees, for example, are highly sensitive to subtle environmental changes and may exhibit behavioural and acoustic responses to stressors associated with wildfire precursors, such as temperature fluctuations, humidity shifts, and vegetation alterations. By leveraging bee acoustic monitoring alongside traditional environmental data streams, it may be possible to detect early warning signals of wildfire risk that are otherwise missed by remote sensing or meteorological models.

Building on this premise, our current research systematically reviews the literature on the relationship between environmental drivers of wildfires and bee behavioural responses, with a particular focus on acoustic signals. This approach aims to address some of the technological and methodological challenges identified in the wildfire prediction literature by exploring the integration of bee bioacoustics as a supplementary indicator within early warning frameworks. The following section outlines the systematic methodology used to examine these interdisciplinary connections.

Correlation Between Bees Behaviour and Environmental Factors

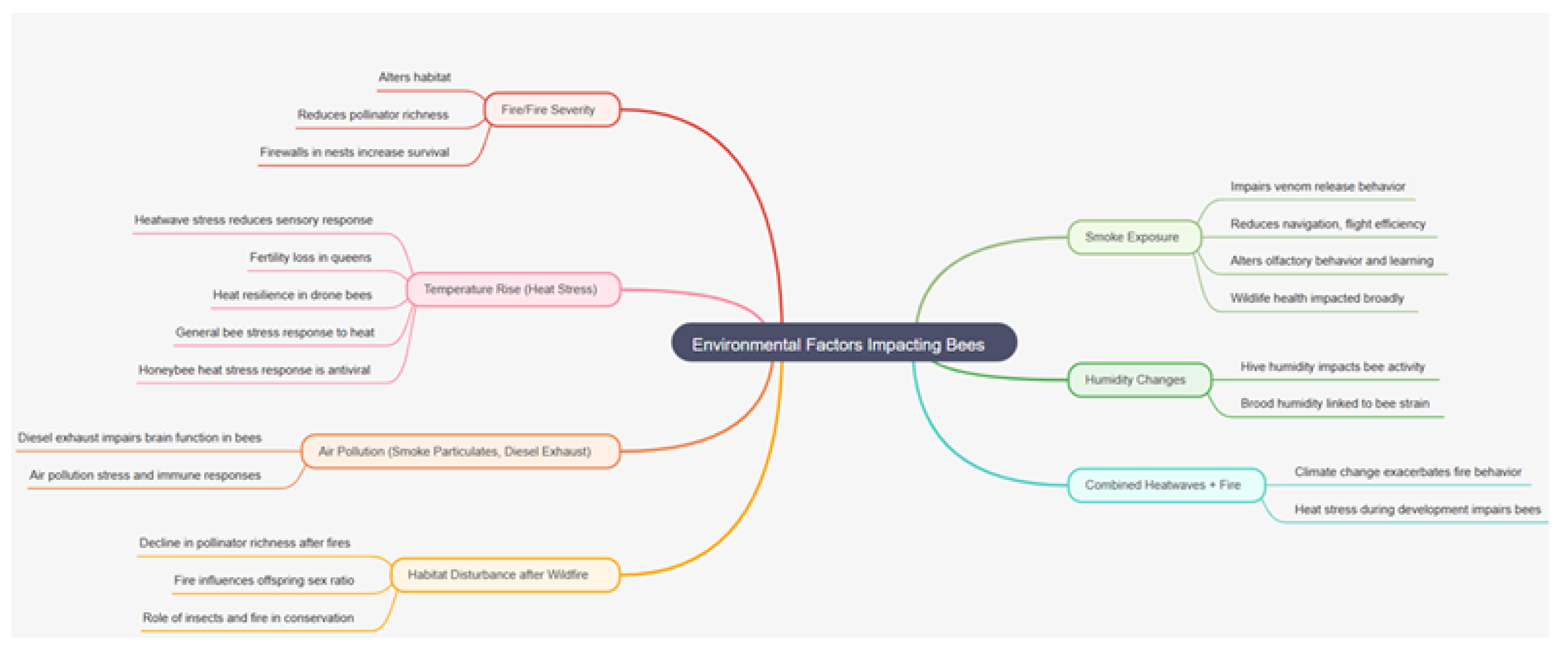

Figure 12 illustrates a conceptual map that comprehensively encapsulates the principal environmental variables exerting influence on apian populations, particularly within the framework of wildfire occurrences. The schematic delineates the interrelationships among fire intensity, escalations in temperature, atmospheric pollution, habitat disruption, exposure to smoke, and fluctuations in humidity, all of which collectively affect bee physiology and behavioural patterns. For instance, fire and thermal stress diminish pollinator diversity, hinder sensory and reproductive capabilities, and challenge bee populations’ resilience. Concurrently, atmospheric pollution and smoke hinder navigational abilities, olfactory learning processes, and immune system functionality. Post-wildfire habitat disturbances further compromise pollinator diversity and reproductive success. Variations in humidity and interactions involving heat or fire may exacerbate stress levels within bee colonies. The cumulative impacts of these factors are frequently synergistic, with climatic alterations exacerbating fire dynamics and developmental heat stress intensifying repercussions on bee health and survival.

The conceptual map further underscores the compounded effects, illustrating how climate change amplifies fire dynamics and how developmental heat stress can detrimentally affect bees. These interactions are not independent; instead, they reinforce one another, culminating in intricate and frequently unpredictable consequences for bee colonies [

105,

110,

113,

117].

Understanding these interrelated factors is crucial for elucidating alterations in bee behaviour and acoustic signals, which are sensitive bio-indicators of environmental stressors. As previously articulated, the integration of bioacoustics monitoring, molecular profiling, and ecological modelling presents promising avenues for the preemptive identification of wildfire threats and for enhancing pollinator resilience within fire-affected ecosystems. Consequently, the conceptual map depicted in

Figure 12 is a theoretical framework for associating environmental stressors with observable modifications in bee populations, thereby fostering innovative methodologies for ecosystem monitoring and conservation initiatives.

The

Table 10 provides a succinct overview of contemporary research concerning the effects of environmental and climatic variables, such as thermal stress, humidity, climate change, wildfires, smoke, and atmospheric pollution, on bee health, behaviour, and colony resilience. Describes areas of investigation, experimental methodologies, and relevant references, encompassing laboratory and field studies. This comprehensive overview, in conjunction with the conceptual map in

Figure 12, emphasises these stressors’ intricate and interlinked impacts on bees, ranging from molecular alterations to modifications in foraging behaviour and communication strategies.

Incorporating methodologies such as bioacoustics monitoring, proteomic profiling, and ecological modelling can enhance the early detection and forecasting of environmental threats. Nevertheless, significant gaps remain in understanding the interactions among multiple stressors and the mechanisms by which bees adapt over extended periods. Addressing these challenges necessitates a multidisciplinary research approach to safeguard pollinators within fire-prone, better, and dynamically changing ecosystems.

7. Challenges, Discussion and Future Direction

The impact of wildfire smoke on bee populations is multifaceted, involving changes in behaviour, foraging patterns, and community dynamics. Although direct studies on bee avoidance behaviours specifically due to smoke are limited, related research provides valuable information on how bees respond to environmental stressors. For instance, honeybees alter their foraging behaviour in response to poor air quality, such as that caused by wildfire smoke, leading to increased foraging trip durations due to disrupted navigation and altered skylight polarization [

124]. This can be interpreted as an avoidance behaviour or difficulty in navigating smoke-affected environments.

Wildfires can lead to changes in bee community composition and abundance, with some species benefiting from new floral resources and nesting sites in burned areas, while others decline [

200,

201]. Specific responses based on different species are evident, as certain bees in the Halictidae family increase in abundance after fire, while others decrease [

202]. Insects, including bees, are sensitive to smoke, which can alter behaviour and physiology. Some species are repelled by smoke, using it as a cue for fire avoidance, while others exhibit altered stress responses like fight-or-flight behaviours [

115,

203].

Smoke exposure disrupts bee foraging by impairing olfactory cues and navigation, leading to increased foraging times and reduced pollination efficiency [

115,

124]. This disruption can cascade through ecosystems, as bees are crucial pollinators. The ecological impacts of wildfires, including habitat changes and resource availability shifts, further influence bee behaviour and community dynamics [

141,

201]. The presence of smoke and pollutants can lead to adverse health effects, contributing to changes in bee movement patterns and avoidance behaviours [

203].

Bees exhibit adaptability to environmental stressors, such as flexible foraging strategies in urban environments, suggesting potential resilience to specific stressors [

196]. However, the cumulative effects of smoke exposure, pollution, and habitat changes necessitate comprehensive mitigation strategies. Habitat diversity and management can mitigate these impacts, highlighting the importance of conservation efforts [

164].

Future research should focus on long-term studies of bee behaviour and community dynamics in fire-prone areas to better understand bee responses to wildfire smoke. Integrating bioacoustics monitoring, proteomic profiling, and ecological modelling can enhance predictive frameworks for detecting environmental stressors [

110,

113,

117]. Investigating specific responses against each species and adaptive mechanisms, along with assessing cumulative effects of multiple stressors, is crucial for predicting how bee communities will adapt to increasing wildfire activity under climate change. By advancing these areas, we can better support pollinator resilience in dynamic ecosystems.

8. Conclusion and Future Directions

The escalating severity and unpredictability of wildfires necessitate early detection systems that are not only technologically advanced but also deeply attuned to environmental signals. This systematic literature review has provided a comprehensive evaluation of recent progress in wildfire prediction methodologies, including machine learning, remote sensing, and IoT technologies, while simultaneously highlighting the emerging ecological perspective of using bee behaviour, especially acoustic signals, as sensitive bioindicators of environmental stressors that often precede wildfire events.

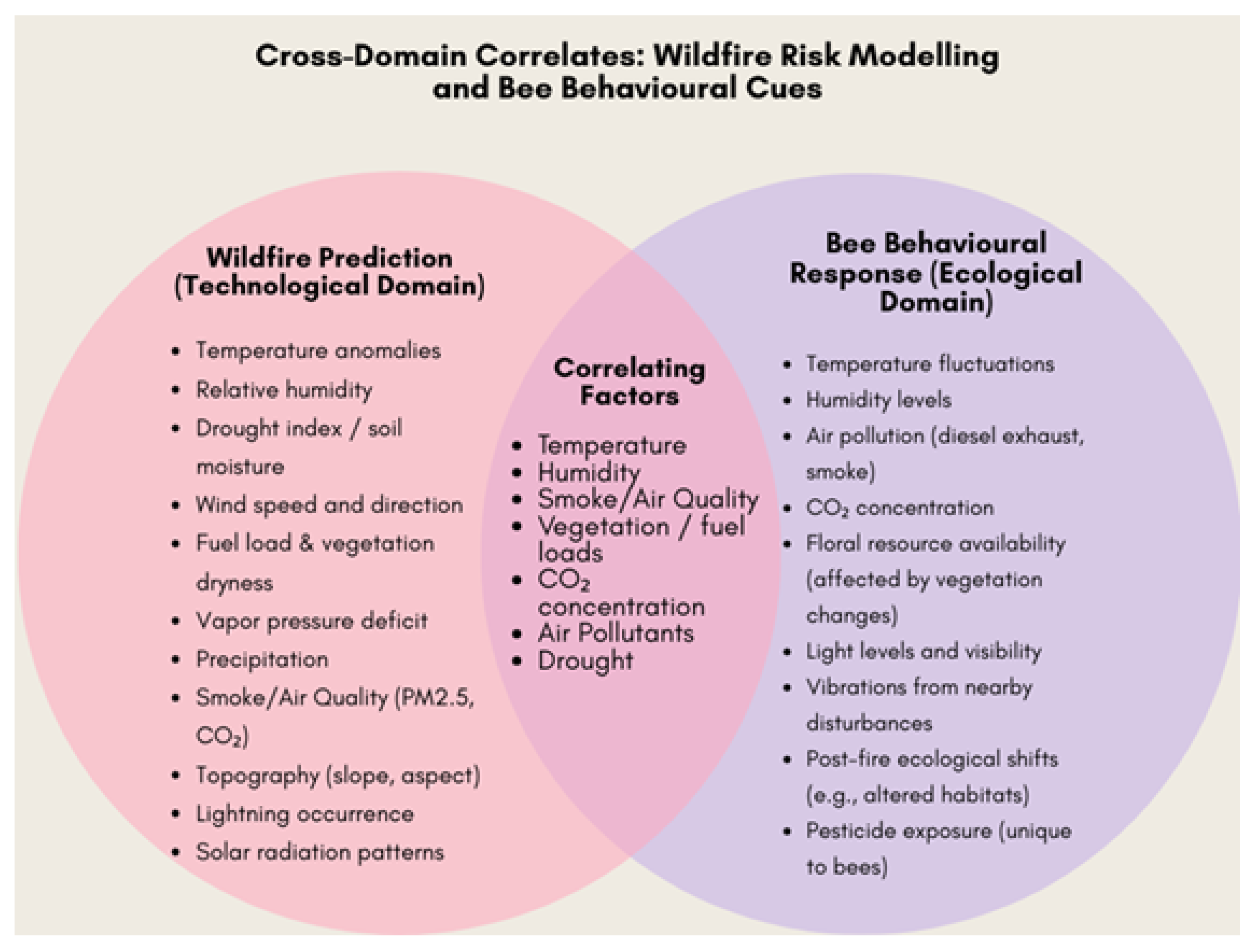

A principal contribution of this review is the identification and synthesis of environmental and climatic factors that simultaneously influence both wildfire risk models and bee behavioural responses. This intersection is visually captured in

Figure 13, a Venn diagram that illustrates the shared and unique factors across the technological and ecological domains. On one side, wildfire prediction systems rely on variables such as temperature anomalies, relative humidity, drought indices, wind, fuel load, and advanced sensor data. On the other hand, bee behavioural studies focus on temperature and humidity fluctuations, air pollution, CO

2 concentration, floral resource availability, light levels, and post-fire ecological shifts. The overlapping region of the Venn diagram highlights correlating factors, such as temperature, humidity, smoke/air quality, vegetation/fuel loads, CO

2 concentration, air pollutants, and drought, that are critical to both domains. These shared factors not only drive wildfire risk but also induce measurable changes in bee behaviour and colony acoustics, underscoring the feasibility of integrating bioacoustics bee data into current early warning frameworks for wildfires.

While advanced machine learning and sensor technologies offer high-resolution, scalable solutions for fire prediction, they are often challenged by data scarcity, high false alarm rates, and environmental noise. Conversely, bees evolved to be acutely sensitive to microclimatic changes and provide complementary, biologically grounded indicators of environmental transformation. Acoustic monitoring of bee colonies has shown promise in detecting stress responses before overt environmental degradation is observable, offering a novel, nature-inspired pathway for early wildfire detection.

However, the integration of these domains is still in its infancy. Future research should prioritise:

Multimodal data fusion: Integrating bee acoustic signals with satellite, meteorological, and IoT sensor data to enhance the robustness and sensitivity of early warning systems.

Development of lightweight machine learning models: Creating models capable of processing real-time bee acoustic data in resource-constrained or remote environments.

Field-based validation: Conducting long-term monitoring of bee colonies in fire-prone areas to inform and train predictive models.

Federated learning frameworks: Establishing privacy-preserving, decentralized learning from distributed bee and environmental sensors to ensure data security and scalability.

Beyond advancing academic understanding, our review highlights important practical and societal prospects associated with this emerging area of research. By synthesizing existing studies on AI-based wildfire detection and bee bioacoustics, we aim to lay the conceptual groundwork for future early warning systems that are both technologically advanced and ecologically informed. Although the integration of bee acoustic monitoring is still in the exploratory phase, it presents an innovative, nature-inspired approach to environmental detection that could enable faster and more reliable wildfire alerts, especially in environments where traditional sensor networks can be impractical or prohibitively costly.

For society, this could lead to greater resilience against wildfires by supporting more timely evacuations and better resource use, reducing risks to people, property, and ecosystems. In research, our work encourages collaboration between ecologists, engineers, and data scientists, promoting the development of more adaptive and effective detection tools. By discussing both the opportunities and the challenges of current approaches, this review encourages further innovation that links technical progress with ecological insight, offering real advantages for wildfire-affected communities and contributing to broader environmental protection and pollinator conservation.

In summary, this review underscores the untapped synergy between AI-driven technologies and bioindicator species like bees for proactive wildfire risk assessment. The convergence of these domains promises more comprehensive, adaptive, and resilient early warning systems grounded in both data science and ecological sensitivity. By recognizing bees not only as pollinators but also as sensitive environmental sentinels, we open the door to innovative, sustainable approaches to the prediction of wildfires, approaches urgently needed in the face of accelerating climate change and environmental volatility.

Figure 1.

AI-generated conceptual diagram illustrating the primary factors that contribute to wildfire spread, categorized into meteorological factors and environmental terrain factors.

Figure 1.

AI-generated conceptual diagram illustrating the primary factors that contribute to wildfire spread, categorized into meteorological factors and environmental terrain factors.

Figure 2.

The organization of this paper.

Figure 2.

The organization of this paper.

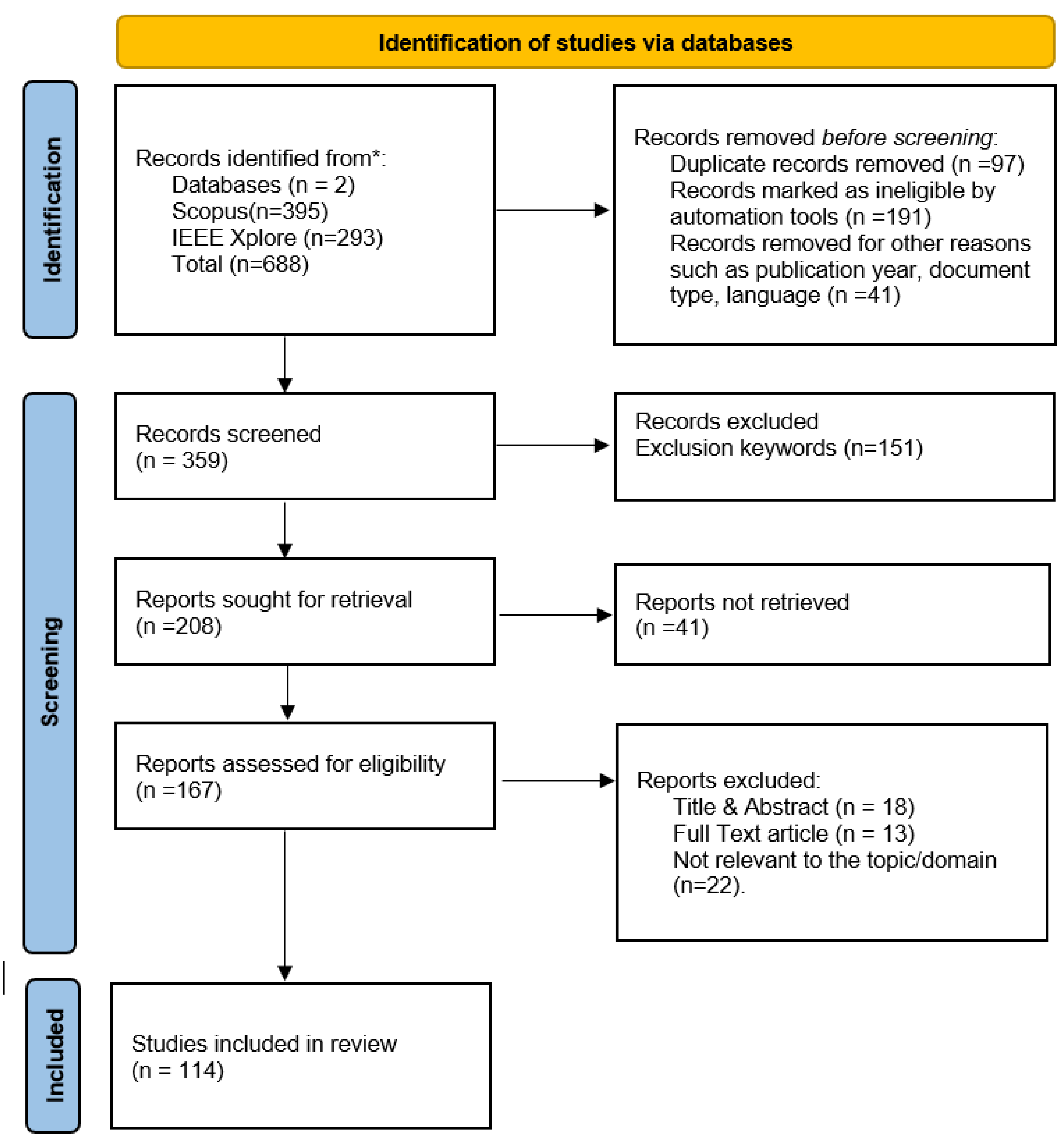

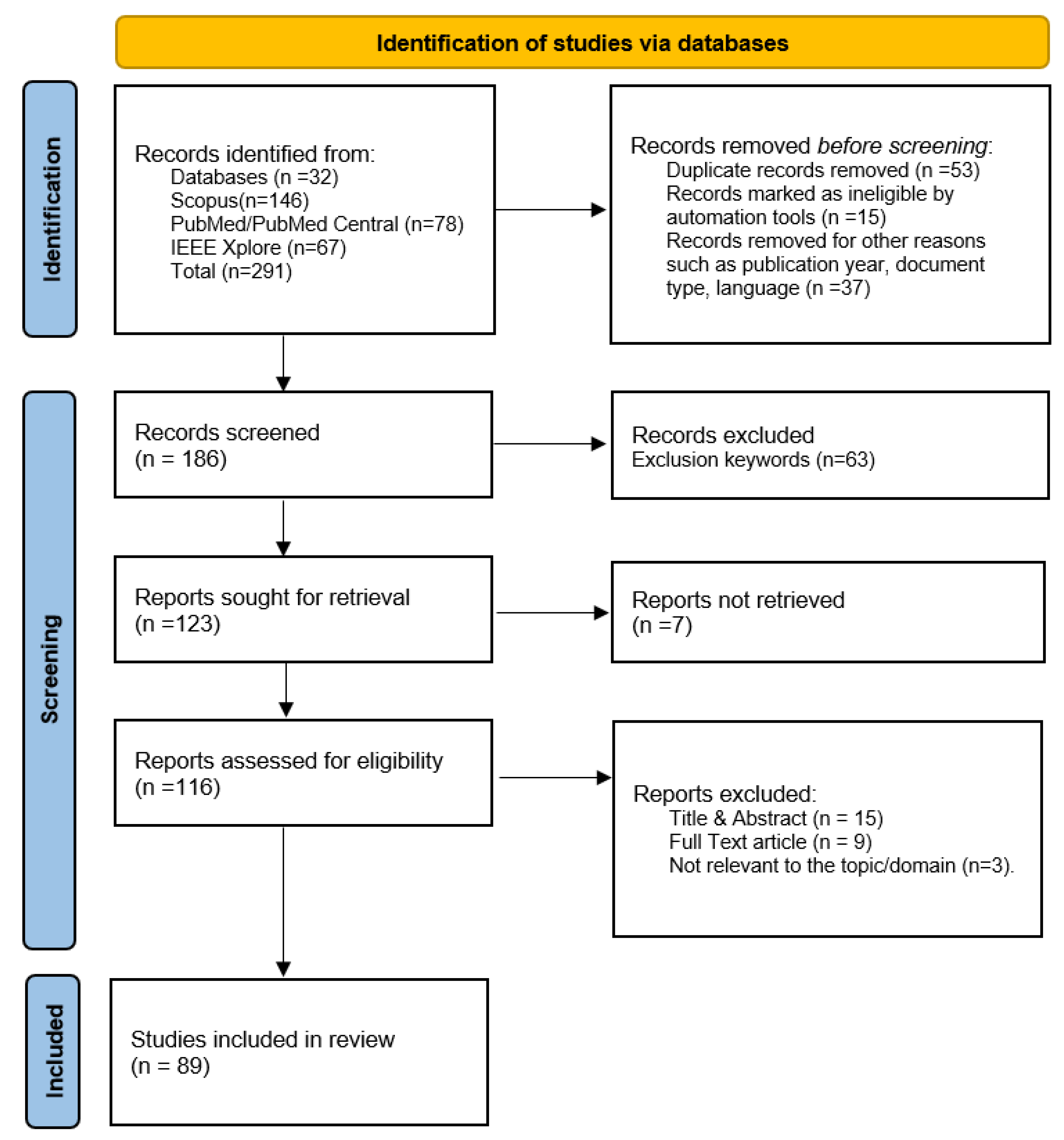

Figure 3.

PRISMA Flowchart Illustrating the Study Selection Process for Systematic Literature Review.

Figure 3.

PRISMA Flowchart Illustrating the Study Selection Process for Systematic Literature Review.

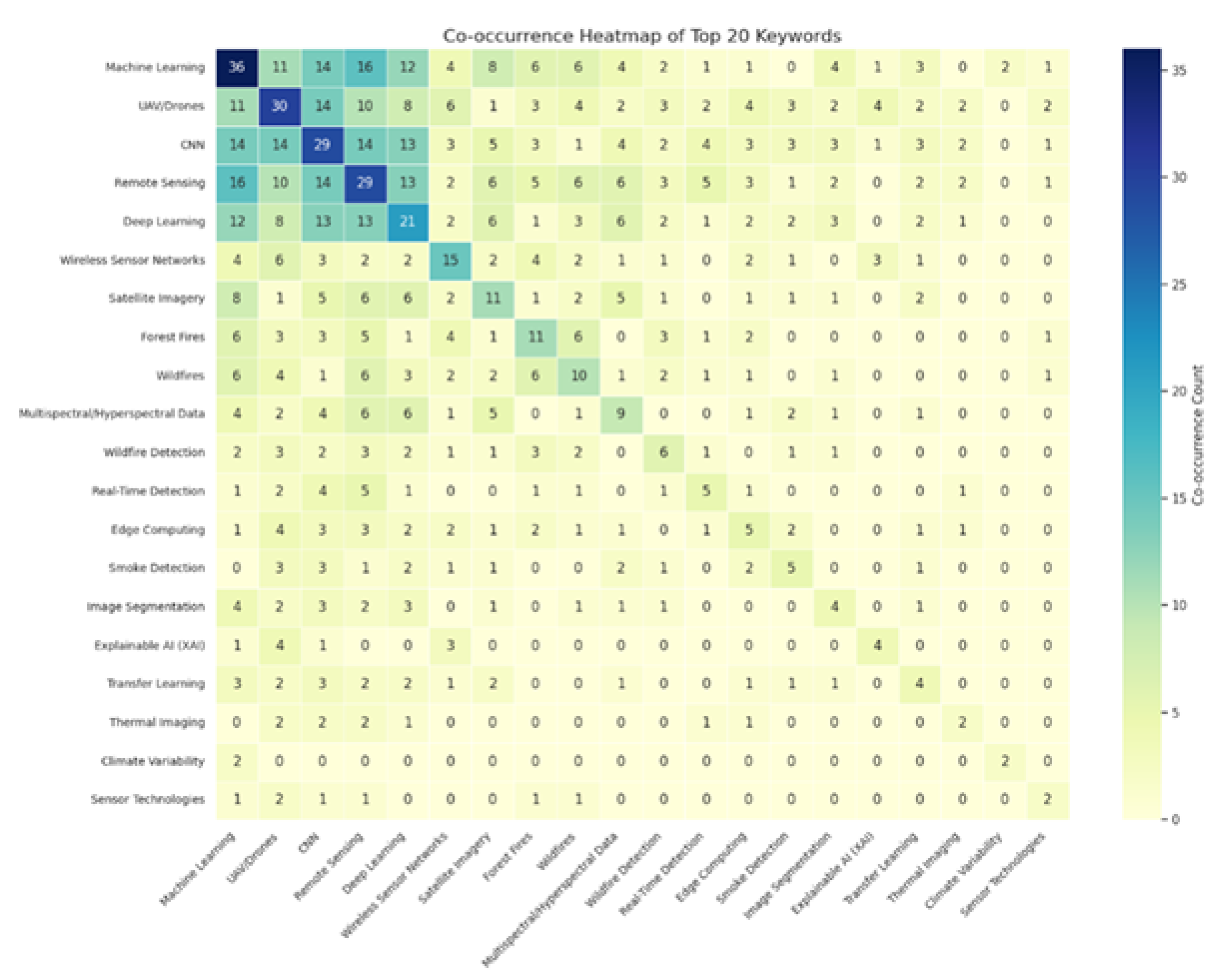

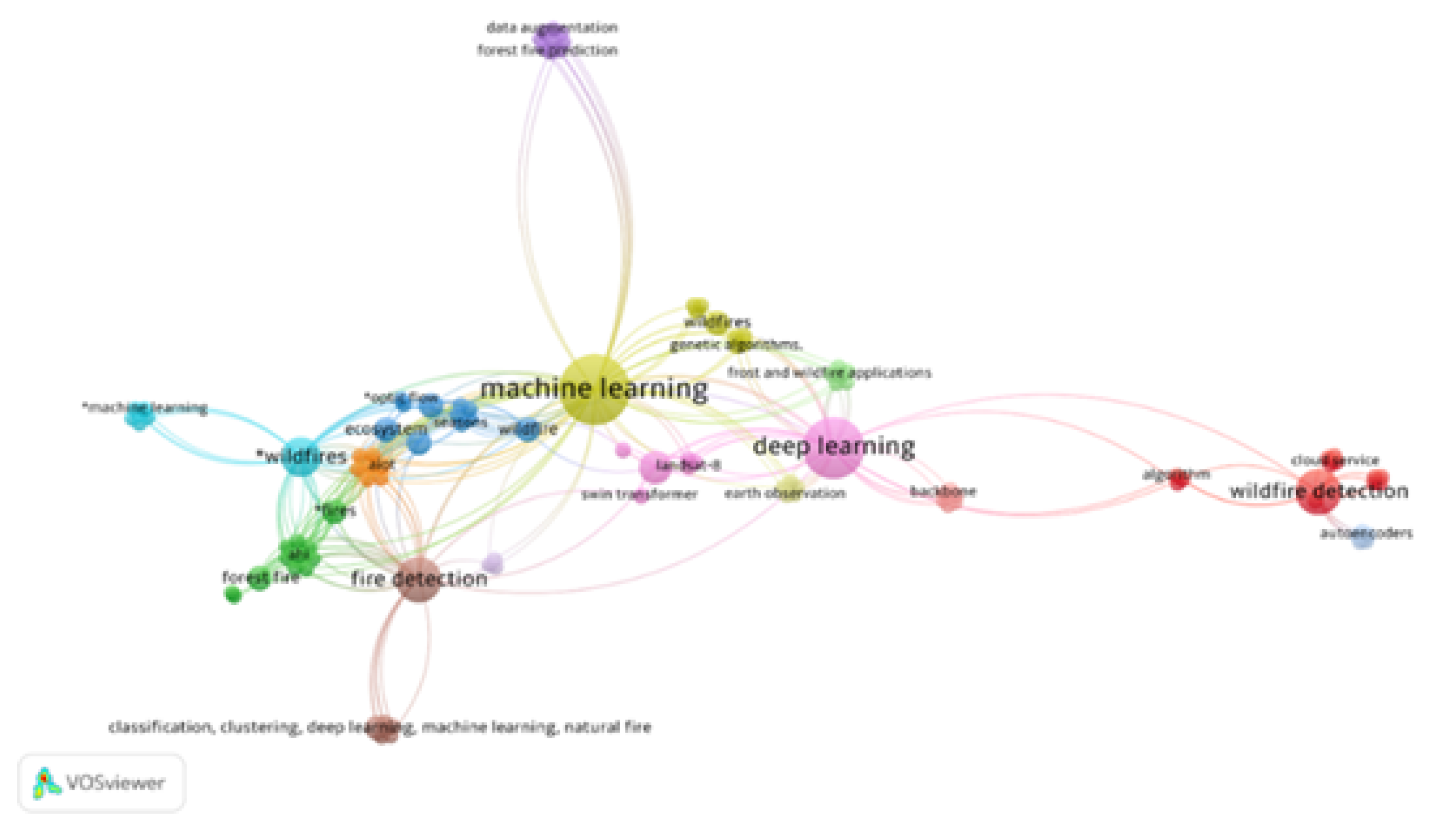

Figure 4.

Keyword co-occurrence network map illustrating dominant research trends in wildfire prediction, with “machine learning” and “deep learning” forming central thematic clusters.

Figure 4.

Keyword co-occurrence network map illustrating dominant research trends in wildfire prediction, with “machine learning” and “deep learning” forming central thematic clusters.

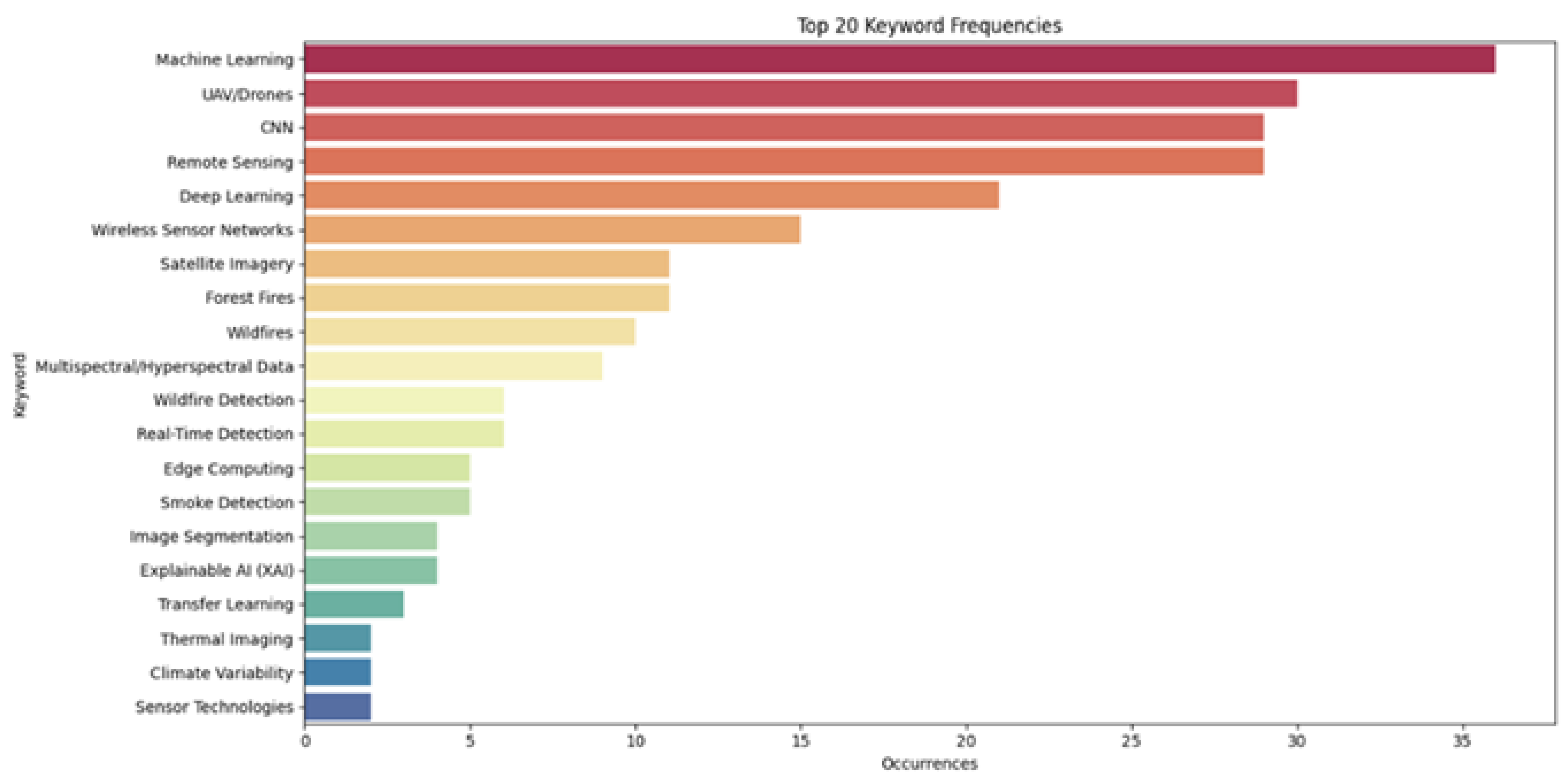

Figure 5.

Top 20 most frequent keywords in wildfire prediction literature, with “machine learning,” “UAVs,” and “CNN” as dominant themes.

Figure 5.

Top 20 most frequent keywords in wildfire prediction literature, with “machine learning,” “UAVs,” and “CNN” as dominant themes.

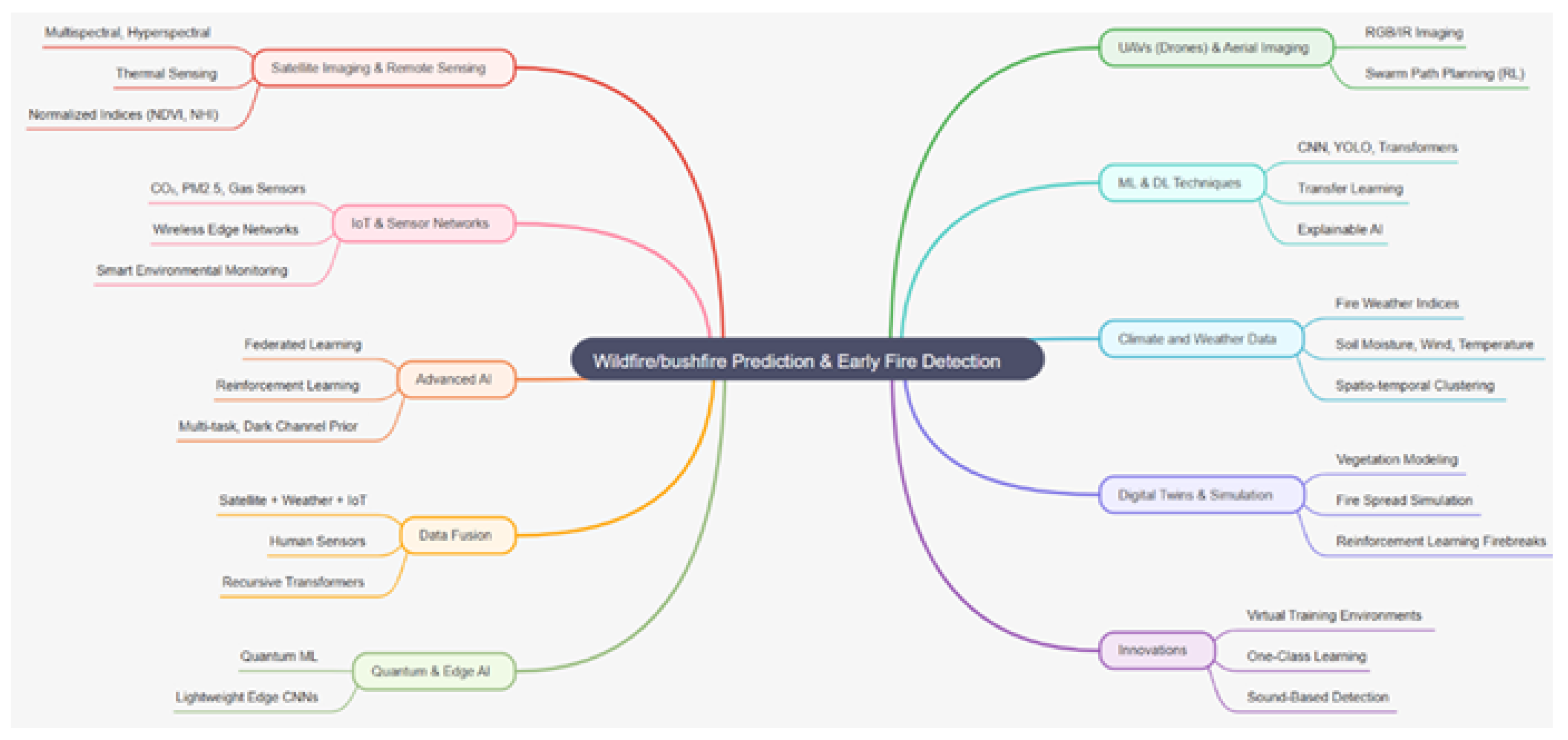

Figure 7.

Thematic mind map of key technologies and domains in wildfire prediction and early fire detection.

Figure 7.

Thematic mind map of key technologies and domains in wildfire prediction and early fire detection.

Figure 8.

Distribution of key challenge areas identified in wildfire research, based on the percentage of papers addressing each issue.

Figure 8.

Distribution of key challenge areas identified in wildfire research, based on the percentage of papers addressing each issue.

Figure 9.

Categorical distribution of wildfire prediction techniques, with detailed annotations on associated technologies and methodologies.

Figure 9.

Categorical distribution of wildfire prediction techniques, with detailed annotations on associated technologies and methodologies.

Figure 10.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the research paper selection process.

Figure 10.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the research paper selection process.

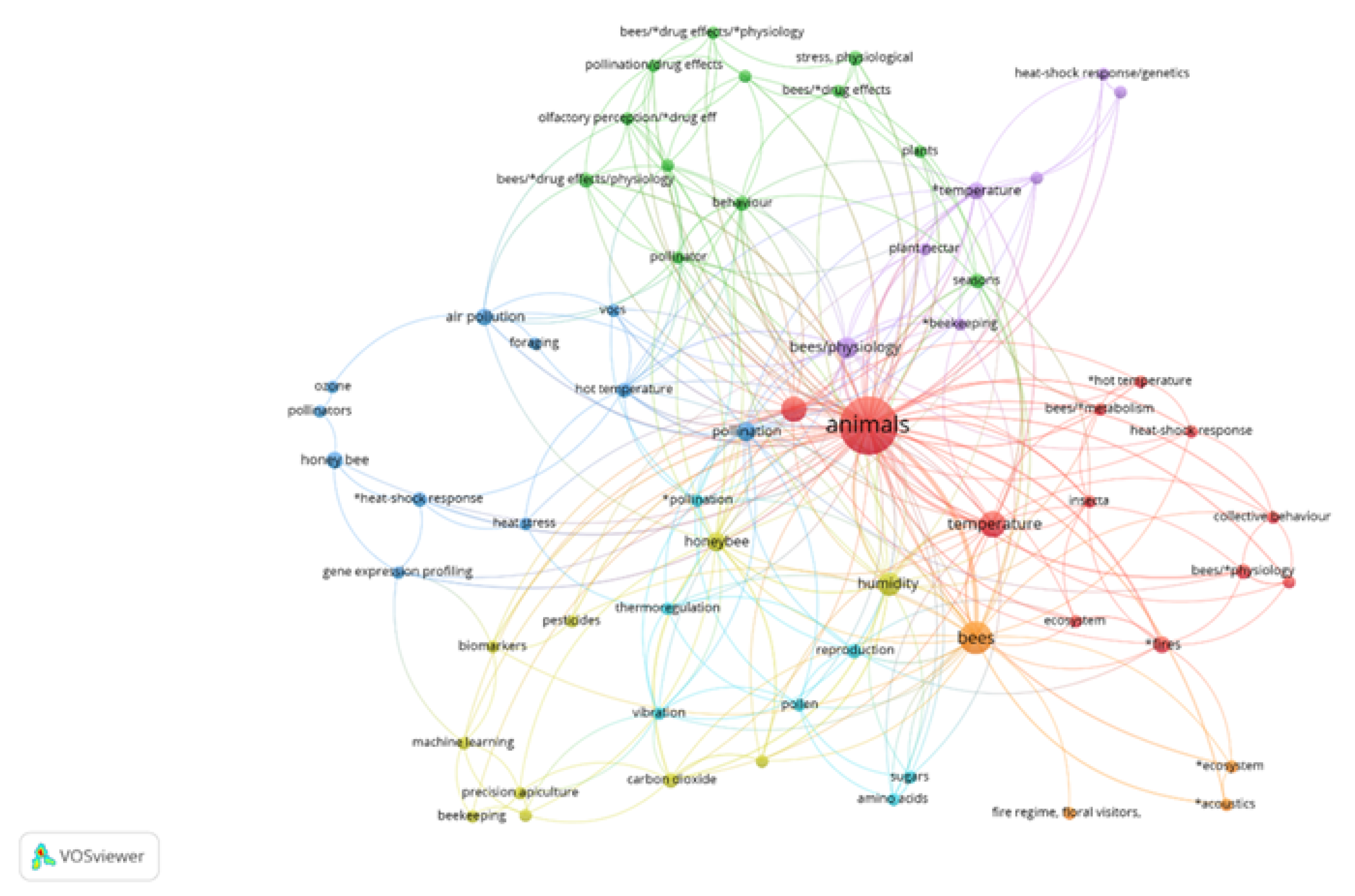

Figure 11.

Keyword Co-Occurrence Network of Environmental and Physiological Factors Affecting Bees.

Figure 11.

Keyword Co-Occurrence Network of Environmental and Physiological Factors Affecting Bees.

Figure 12.

Mind map illustrating the major environmental factors impacting bee populations during wildfire events.

Figure 12.

Mind map illustrating the major environmental factors impacting bee populations during wildfire events.

Figure 13.

Cross-domain Venn diagram illustrating the key environmental and climatic factors shared between wildfire risk modelling (technological domain) and bee behavioural responses (ecological domain).

Figure 13.

Cross-domain Venn diagram illustrating the key environmental and climatic factors shared between wildfire risk modelling (technological domain) and bee behavioural responses (ecological domain).

Table 1.

Research paper selection criteria.

Table 1.

Research paper selection criteria.

| Criteria |

Eligibility |

Exclusion |

| Literature type |

Journal, conference papers |

Review paper, book series, book, chapter in book, conference proceeding |

| Language |

English |

Non-English |

| Timeline |

Between 2019 and 2025 |

2018 and earlier |

Table 2.

Environmental and climate factors are studied in wildfire prediction research, with key references.

Table 2.

Environmental and climate factors are studied in wildfire prediction research, with key references.

| Environmental/Climate Factors |

Key Focus |

Reference |

| Weather variables (precipitation, temperature, wind, humidity, drought), climate variability, vegetation patterns, fuel loads |

Quantifies the effects of environmental factors on wildfire burned area using ML |

[5,14,15,35,44,68,84,85,86,87,88,89,90] |

| Vapor pressure deficit, relative humidity, energy release component (ERC), large-scale circulation patterns |

Identifies drivers of burned area using ML and SHAP interpretation |

[6,44,58,69,84,91,92] |

| Drought, soil moisture, Atlantic/Pacific SST gradient, external radiative forcings |

Predicts multi-year drought and wildfire probabilities using Earth system models |

[5,6,44,85,87,89,91] |

| Fuel moisture, meteorological drivers (temperature, humidity, precipitation) |

Contrasts the environmental conditions of human- vs. lightning-ignited wildfires |

[5,6,38,44,65,85,89,91,93,94] |

| Meteorological conditions (RH, precipitation), vegetation, lightning ignition |

Predicts global lightning-ignited wildfires under climate change |

[5,6,8,43,69,95] |

| Vegetation indices (NDVI), land surface temperature, drought indices |

Reviews remote sensing methods for early fire detection |

[35,44,58,84,85,92,93,94] |

| Topographic heterogeneity, temperature seasonality, climatic water deficit, anthropogenic factors |

Analyses geographical variation in fire regimes under climate change |

[5,35,36,43,58,68,87,88,89,96,97,98] |

| Fuel dryness, vegetation growth, and CO2 fertilization |

Examines how climate change aggravates wildfire behaviour through increased fuel loads |

[36,85,99,100] |

| Antecedent weather-driven vegetation growth, fine fuel accumulation |

Demonstrates value of dynamic vegetation in Great Basin fire prediction |

[2,4,85,101,102] |

Table 3.

Research paper selection criteria.

Table 3.

Research paper selection criteria.

| Criteria |

Eligibility |

Exclusion |

| Literature type |

Journal, Conference papers |

Review paper, book series, book, chapter in book, conference proceeding |

| Language |

English |

Non-English |

| Timeline |

Between 2019–2025 |

2018 and earlier |

Table 4.

Normal and deviated bee behaviours under environmental and climate conditions.

Table 4.

Normal and deviated bee behaviours under environmental and climate conditions.

| Behaviour Aspect |

Normal Behaviour (Typical Conditions) |

Deviated Behaviour (Stressful Conditions) |

Numerical Facts / Evidence |

References |

| Foraging Activity |

Optimal foraging at 21-33.5°C; peak activity in morning/early afternoon; efficient pollen/nectar collection |

Reduced foraging above 33.5°C; foraging nearly ceases above 43°C; trip duration increases in poor air quality |

Foraging trip duration ↑ by 32 min during pollution; optimal range: 21–33.5°C |

[103,104,110,124,125] |

| Colony Temperature Regulation |

Brood nest temperature stable at 33-35°C; fanning and water collection for thermoregulation |

Brood temp fluctuates; heat stress increases fanning up to 300%; metabolic changes, dehydration |

Brood nest temp: 33-35°C; fanning ↑ 300% at 40°C |

[110,125] |

| Brood Rearing |

Stimulated by longer days and resources; continuous in mild climates |

Reduced during heat stress/poor resources; increased disease/Varroa susceptibility |

Brood rearing ↓ during heatwaves; Varroa ↑ with longer brood periods |

[106,107,109] |

| Flight Activity Timing |

Peaks 9 AM-2 PM; diurnal variability linked to floral availability |

Reduced/shifted activity during extreme heat or smoke exposure |

Flight activity peaks 9 AM-2 PM; varies by plant species |

[103,112] |

| Olfactory Sensitivity |

High antennal sensitivity to floral VOCs; effective olfactory learning/memory |

Reduced antennal response to scents; impaired learning due to ozone/pollutants |

Olfactory response ↓ up to 80% after heatwaves; ozone impairs learning |

[126,127,128] |

| Communication (Acoustic Signals) |

Clear waggle dance, piping, and other signals; stable frequency/intensity |

Disrupted signals; stop signals ↑ 4x during smoke; altered dance accuracy; distress piping |

Stop signals ↑ 4x during smoke; piping at 250–280 Hz precedes distress |

[129,130] |

| Temperature |

Brood comb maintained at 33-36°C; RH ∼70%; foraging peaks ∼20°C; bees regulate hive temp by fanning, water collection, clustering, shivering |

Foraging decreases above 35°C; ceases above 43°C; heat stress causes dehydration, impaired immunity, reduced brood; bees move faster, more dispersed; CTmax: honeybees ∼49.1°C, bumblebees ∼53.1°C, sweat bees ∼50.3°C |

CTmax increases only 0.09°C per 1°C rise |

[105,106,110,113,125,131] |

| Humidity |

Bees maintain hive RH via fanning/hygroscopic materials; in-hive RH: 50–75%; brood RH optimal: 90-95% |

Extreme low RH (<30%) or high RH (>75%) disrupts regulation, increases metabolic stress; high RH reduces longevity, exacerbates heat stress |

Best worker survival at 75% RH at 35°C; productivity ↑ 0.237% per 10% RH (up to optimal); survival correlated with RH (, ) |

[132,133,134,135] |

| CO2

|

Typical in-hive CO2: 0.55% (large colony), 0.92% (small); bees tolerate high CO2 without visible distress; fanning increases with CO2

|

High/acute CO2 can induce ovary activation in queens, metabolic shifts; chronic CO2 reduces pollen protein content |

Ovary activation ↑, fat body lipids ↓; protein in ovaries ↑; pollen protein ↓ 30%; CO2 range: 0.33-1.77% |

[136,137,138,139] |

Table 5.

Summary of Environmental Stressors and Their Impact on Bee Acoustics.

Table 5.

Summary of Environmental Stressors and Their Impact on Bee Acoustics.

| Environmental Factor |

Effect on Acoustic Emissions |

Citation |

| Temperature Fluctuations |

Increased intensity of acoustic emissions during extreme weather conditions |

[113,143] |

| Humidity Changes |

Disruption of hygroregulation mechanisms, leading to altered acoustic signals |

[132] |

| Heat Stress |

Activation of physiological stress mechanisms, altering worker activity and acoustic emissions |

[144] |

| Synergistic Effects of Temperature and Humidity |

Amplified impact on acoustic emissions due to combined stress |

[144] |

| Environmental Stressors (General) |

Increased stress levels, leading to altered acoustic emissions and negative impacts on colony health |

[105,106] |

Table 6.

Applications of AI in bee acoustic and environmental monitoring.

Table 6.

Applications of AI in bee acoustic and environmental monitoring.

| Area of Study / Observation |

Factors Discussed |

Method Used |

Results & Findings |

| IoT + ML |

| Bee colony anomaly detection [147] |

Temperature, humidity, hive health |

IoT audio sensors, ML multiclass classification, edge computing |

anomaly detection in real time. |

| Varroa infestation detection [156] |

Hive environment, pest infestation |

IoT sensor aggregation, ML classification |

Detected Varroa presence with high sensitivity, false negatives ↓ 15% |

| Stingless bee honey production monitoring [157] |

Temperature, humidity, floral cues |

IoT sensors, image detection framework |

Yield prediction ↑ 12% |

| Beehive state and events recognition [158] |

Hive sound patterns, swarming, queen loss, foraging |

TinyML audio signal analysis, embedded ML on edge devices |

Audio-based event recognition models achieved event detection (e.g., swarming, queen loss) |

| Precision beekeeping [159] |

Temperature, humidity, CO2, hive weight, activity |

Review and synthesis of IoT+ML methods, multi-sensor system examples |

90-98% classification accuracy for activity states; early anomaly alerts |

| Bee colony health prediction [160] |

In-hive temp/humidity, weight, weather, inspections |

Data fusion (hive sensors + weather), ML-based status forecasting |

Predicted colony health 2 weeks ahead; achieved 85-92% forecast accuracy |

| Image Processing & ML |

| Pollinator conservation, bee monitoring [161] |

Habitat, floral resources, activity |

Object recognition algorithms (CNN), Computer Vision |

Detection ↑ 18%; large-scale monitoring of bee activity |

| Automated insect monitoring [162] |

Habitat, insect diversity |

DIY camera trap, image processing |

bee presence accuracy |

| Bee detection from acoustic data [163] |

Hive acoustics and bee activity |

Image-based spectrogram + selective acoustic features + ML classifiers (e.g., SVM, CNN) |

Accurate bee activity classification from spectrograms; robust with selected features |

| Audio Processing & ML |

| Acoustic monitoring of Bombus dahlbomii [164] |

Temperature, habitat loss, invasives |

Acoustic sensors, ML pattern recognition |

Habitat shifts tracked; 92% accuracy |

| Acoustic monitoring, bee traits [151] |

Temperature, species ID |

Wingbeat analysis, ML, acoustic feature extraction |

Wingbeat frequency negatively correlated with temperature; species classification |

| Beehive audio classification [150] |

Hive state, environmental stress |

Deep learning (CNN), spectrogram analysis |

94% hive state accuracy with CNN; noise robust |

| Swarm prediction via acoustics [153] |

Temperature, hive congestion |

Acoustic biosensor, ML, time-series analysis, SVM, and ANN |

Detected pre-swarm signals 2 days in advance; prediction accuracy 87% |

| Queen detection via audio [165] |

Queen presence, hive health |

Remote audio sensing, ML classification |

91% queen status detection; early warning of queen loss |

| Sound pattern analysis [166] |

Hive behavior, colony stress patterns |

Audio spectral analysis, signal visualization, frequency modelling |

Hive states alter sound spectra; useful diagnostic signal |

| Buzz fingerprinting [167] |

Colony identity, environmental conditions, health status |

Acoustic signal processing, spectral entropy, ML classification |

Unique buzz prints; classification accuracy |

| Multi-Model Data Processing |

| Hive monitoring: weight, temp, traffic [149] |

Temperature, hive activity |

Time series forecasting, ML, sensor fusion |

Health prediction ↑ 15% |

| Bee health & environment review [168] |

Multiple: temp, humidity, stress |

Literature review, ML/DL synthesis |

Integration of multi-source data needed for monitoring |

| Bee health blood test [169] |

Land use, environmental stress |

Mass spectrometry, ML, multi-site data |

Detected biomarkers at 20+ sites; 89% health classification |

| Habitat suitability modelling [145] |

Temperature, climate, and land use |

ML(Random Forest, SVM), cloud computing, spatial modelling |

Predicted Apis florea distribution shifts under climate change; model AUC 0.93 |

| Honey production factors [146] |

Temperature, humidity, environment |

ML regression, variable importance ranking |

Temp/humidity top predictors; model explained 78% yield variance |

| Beehive survival prediction [148] |

Weather, management, climate |

ML, survival analysis |

Weather+management data; Predictions ↑ 22% |

| Crop yield prediction [155] |

Temperature, climate change, yield |

Ensemble ML, environmental data fusion |

Yield ; bee activity critical |

Table 8.

The Impact of Heat Stress on Bee Communication.

Table 8.

The Impact of Heat Stress on Bee Communication.

| Effect of Heat on Communication |

Description of Impact |

Citation |

| Disruption of Sound Production |

Heat stress alters metabolic rate, affecting buzzing sounds in bumblebees. |

[181] |

| Impaired Floral Communication |

Heatwaves reduce antennal responses to floral scents in bumblebees. |

[126] |

| Changes in Social Communication |

Heat stress reduces accuracy of dance communication in honeybees. |

[182] |

| Thermal Communication in Brood |

Heat stress disrupts thermal responses used for brood care. |

[175] |

| Species-Specific Vulnerability |

Solitary bees are more vulnerable to heat stress than social bees. |

[121] |

Table 9.

Environmental Stressors and Their Impact on Bee Acoustics.

Table 9.

Environmental Stressors and Their Impact on Bee Acoustics.

| Environmental Factor |

Effect on Acoustic Emissions |

Citation |

| Temperature Fluctuations |

Increased intensity of acoustic emissions during extremes |

[143] |

| Humidity Changes |

Disruption of hygroregulation, altered acoustic signals |

[132] |

| Heat Stress |

Alter work emissions and acoustic emissions. |

[133,144] |

| Synergistic Effects |

Amplified impact on acoustic emissions |

[144] |

| Environmental Stressors |

Increased stress levels, leading to altered acoustic emissions and negative impacts on colony health. |

[105,106] |

Table 10.

Summary of studies on bee stressors and environmental factors.

Table 10.

Summary of studies on bee stressors and environmental factors.

| Year of Study |

Key Focus Area |

Method Used |

References |

| Heat Stress |

| 2025 |

Effects of zinc-methionine and Sel-Plex; Hyperthermia influence on varroa/viruses; Drone resilience factors; Queen size and HSP90/HSC70 role. |

Lab RT-qPCR, heat chambers, gene expression, statistical resilience models. |

[107,108,186,187] |

| 2023 |

Honeybee heat stress response; Thermal tolerance in stingless bees. |

Thermocouples, video tracking, survival analysis (Kaplan–Meier). |

[110,190] |

| 2022 |

Drone bee abiotic stress sensitivity; Heatwave effects on bumblebee workers. |

Heat shock assays, temp. chambers, maze behaviour tests. |

[189,191] |

| 2021 |

Mechanisms of heat stress response. |

Thermocouples, spectrophotometric physiology assays. |

[106] |

| 2020 |

Heat-induced queen fertility loss; Heat shock response; Immunocompetence effects. |

Histology, qRT-PCR, phenoloxidase enzyme assays in heat chambers. |

[109,192,193] |

| 2019 |

Acetylcholinesterase 1 expression under heat stress. |

RT-PCR, Western blotting, stress analysis. |

[180] |

| Temperature and Humidity |

| 2022 |

Hive colonisation affected by temp. and RH. |

Field loggers + regression analysis. |

[194] |

| Climate Change |

| 2025 |

Climate impacts and mitigation by management. |

Field surveys, interviews, ANOVA. |

[195] |

| 2025 |

Urban climate impacts on Amazonian stingless bees. |

Field sensors + regression modelling. |

[196] |

| General Stressors |

| 2025 |

Stress responses in divergent bee species. |

Biochemical assays (Western blotting, t-tests). |

[197] |

| Wildfire & Smoke Impacts |

| 2024 |

Decline in pollinator richness with fire distance. |

Transect surveys, linear regression. |

[140] |

| 2022 |

Review of smoke impacts on insects. |

Meta-analysis, random effects modelling. |

[115] |

| 2021 |

Wildfire severity effects on bee offspring sex ratio. |

Transect fieldwork, logistic regression. |

[141] |

| Environmental Stressors |

| 2024 |

Vibrational pulse response in colonies; Passive trapping bias. |

Electromagnetic shaker (340 Hz), accelerometers, randomized pulses; Pitfall traps + GLM analysis. |

[129,198] |

| Air and Smoke Pollution |

| 2023 |

Poor air quality linked to bee stress. |

Air sensors + correlation analysis. |

[199] |

| 2020 |

Smoke effects on butterfly flight. |

Flight mill + PM2.5 variation, paired t-tests. |

[115] |

| Diesel Exhaust |

| 2019 |

Diesel exhaust impact on bee memory/learning. |

Diesel exposure, behaviour assays, HSP70 analysis. |

[114] |