1. Introduction

Aerial Image Segmentation (AIS) is an essential task for various city monitoring purposes, such as environmental surveillance, target localization, and disaster response [

1,

2,

3]. With semantic segmentation models trained on large-scale annotated data, humans can easily extract abundant geo-spatial information from aerial images captured by drones or satellites [

4,

5,

6].

1.1. The Challenge of Weather Change caused Domain Shift in Aerial Imagery

While the performance of semantic segmentation algorithms has surged on common benchmarks, progress in handling the domain shift of unseen environmental conditions is still stagnant [

7,

8,

9]. We demonstrate that the aerial segmentation performance of algorithms is prone to significant degradation due to

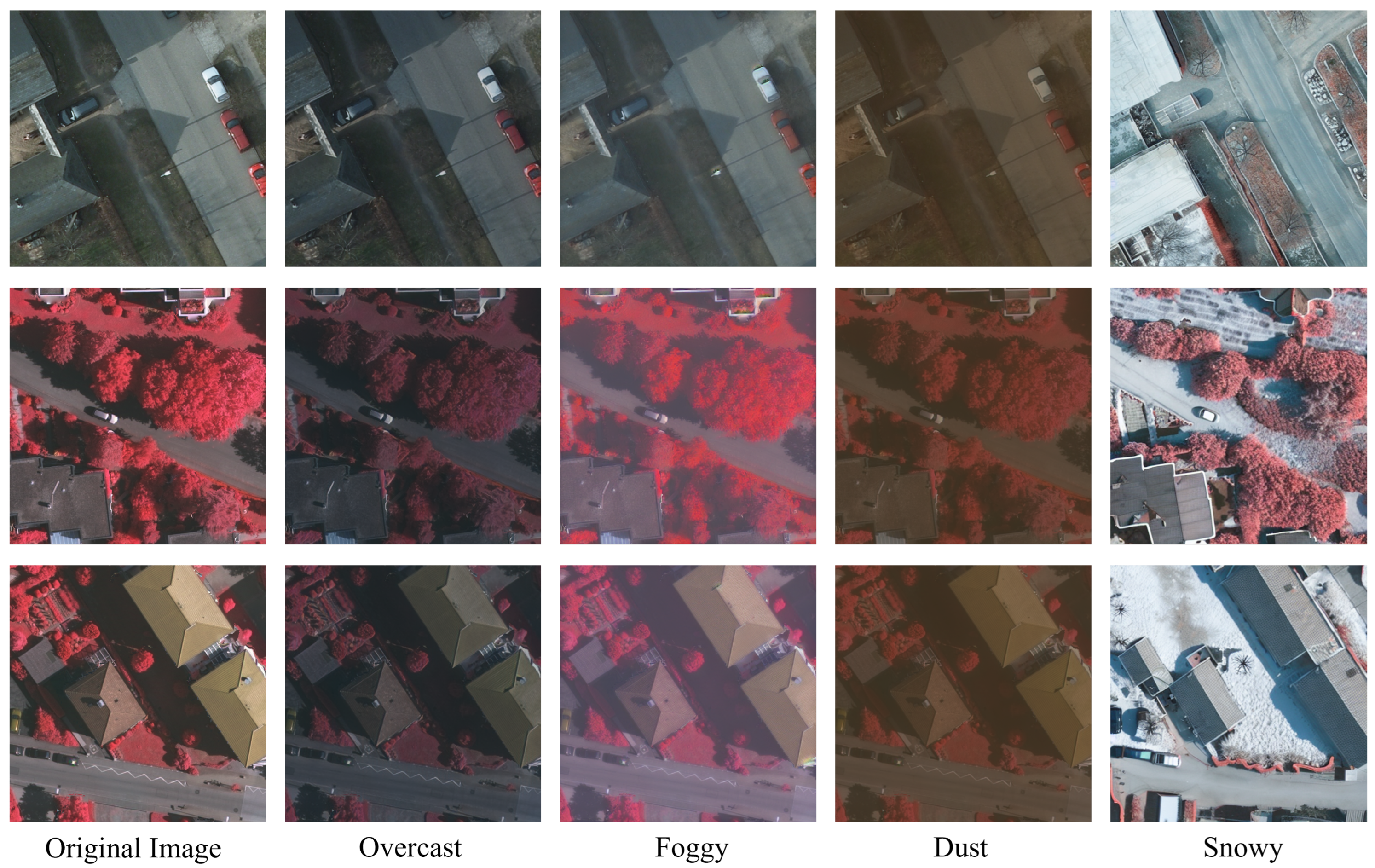

Domain Shift, i.e., the transfer from one domain to another. In

Figure 1, we illustrate this phenomenon by comparing the original data in the ISPRS datasets [

10,

11] with our generated domain-shifted versions, including illumination variations (clear to overcast), changing atmospheric conditions (clear to foggy, dusty), and physical scene changes (clear to snowy). Notably, the scene content and target information remain consistent across all weather variations, while atmospheric conditions and illumination characteristics change significantly in the first three weather domain. The last snowy condition presents additional challenges with physical scene changes including leaf drop, snow-covered roofs and ground, while preserving the information of target of interests. This figure demonstrates the challenge of cross-domain generalization in aerial image analysis.

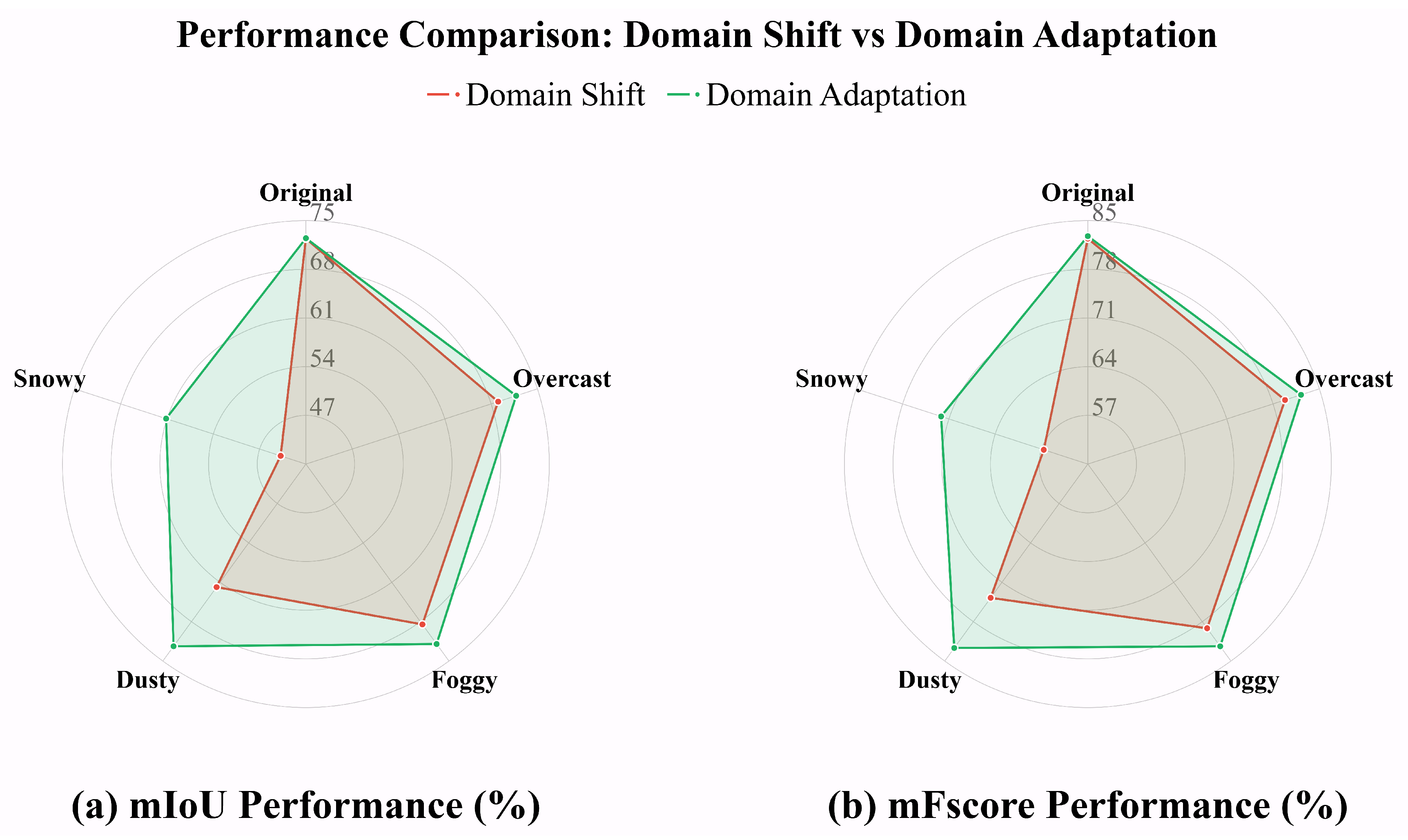

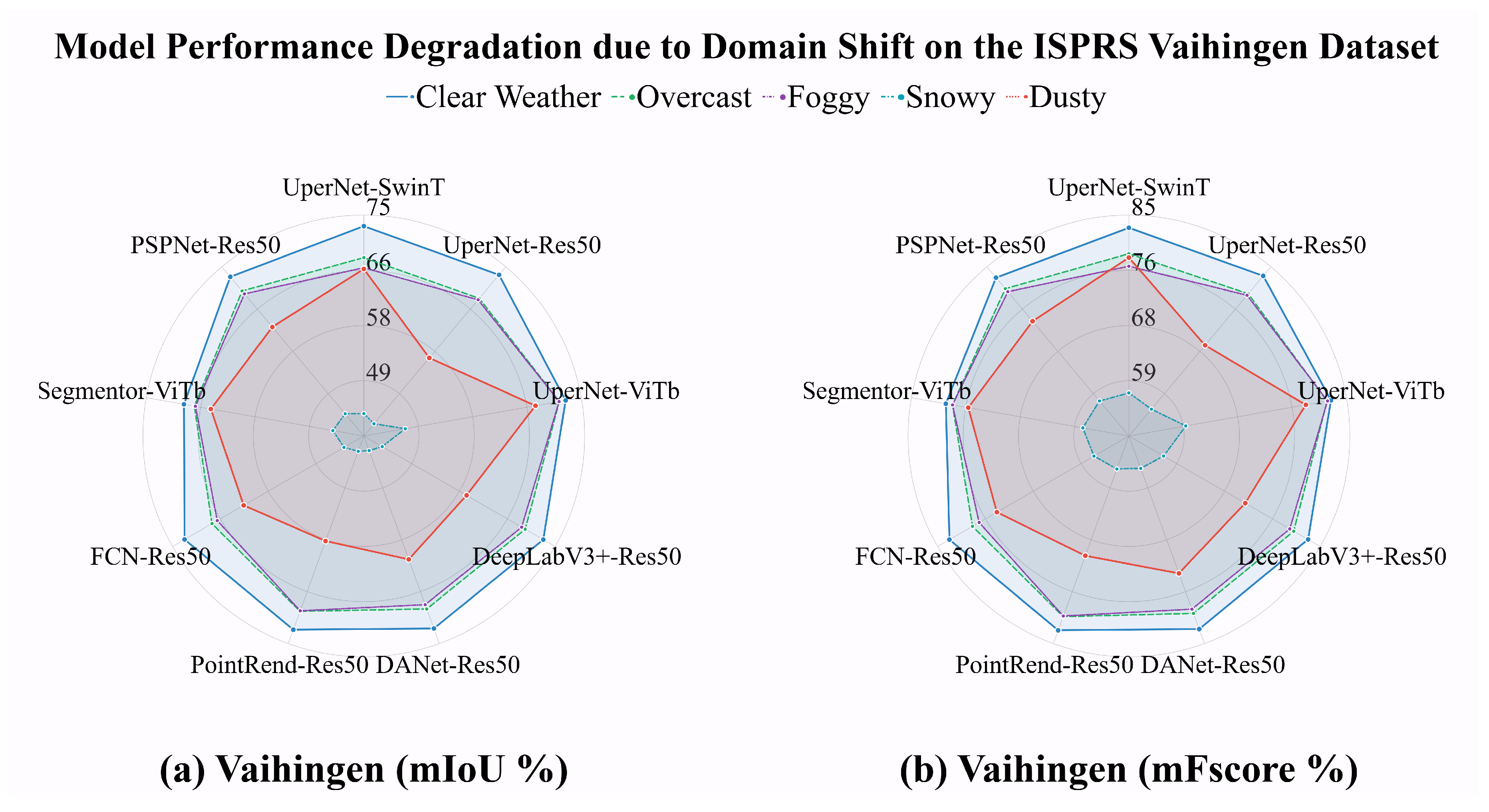

The radar chart in

Figure 2 , in which our evaluations of nine state-of- the-art segmentation models on the ISPRS dataset [

10,

11] and its domain-shifted version are shown, further illustrates that even within the same scene and objects, slightly altering the atmospheric conditions and varying lighting levels pose challenges for aerial image segmentation algorithms. As detailed in the caption of Fig. 2, the results show that after transferring the data from its original, intact domain to shifted domains, there is an average mIoU deterioration of {

-3.35%,

-3.92%,

-10.55%,

-28.59%} and mFscore deterioration of {

-2.61%,

-3.24%,

-8.66%,

-25.76%} under overcast, foggy, dusty, and snowy conditions on the Vaihingen dataset (

resolution). Notably, we generated snowy image sets with five different random seeds, and the numeric results represent the average across these five sets. Compared to the original intact data, the illumination in the shifted overcast images is reduced, foggy and dusty weather additionally changes the atmospheric information, and the snowy scene add physical changes on the target of interest in the original scene, representing typical domain shift. However, the image content, layout, and geo-spatial information between the original and shifted data remain unchanged.

Closing the gap between model performance in the original domain and the shifted domain is a valuable problem to address. An intuitive solution is to incorporate multi-domain data into the model training process. The performance of aerial image segmentation models significantly relies on the availability of training data. Although data from adverse domains is essential to improve the robustness of aerial image segmentation models, such data—including aerial images captured under low illumination and harsh weather conditions is lacking in the current aerial image benchmarks [

10,

11,

12]. On the other hand, even if sufficient data is obtained, annotation remains a time-consuming and labor-intensive task. This paper breaks the limitation of low-domain diversity while eliminating the need for additional annotations on shifted domain data.

1.2. Recent Developments in Generative Model and Image Synthesis

Recently, significant success has been achieved by generative models, which aim to mimic humanity’s ability to yield various modalities. The capacity of GPT-series [

13,

14], Llama series [

15,

16], Qwen series [

17,

18] and DeepSeek series [

19,

20] in Natural Language Processing field has significantly impacted human’s daily life. In the meantime, stable-diffusion [

21,

22], DALL-E [

23,

24] in Computer Vision, have been proposed for generating high-quality realistic images.

While earlier methodologies like Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-based methods [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30] and Variational Autoencoder (VAE)-based methods [

31,

32] demonstrate remarkable performance in yielding realistic samples, training instability remains a well-known issue. For instance, GANs require a delicate balance between the generator and discriminator, which can lead to problems like mode collapse—where the generator produces limited diversity in outputs. This motivated the development of more stable approaches like diffusion models.

Instead of traditional diffusion models (DMs) that denoise the input

x in the image-scale (pixel level) [

33,

34], current general text-to-image (T2I) Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs) [

21,

22,

23,

35,

36] adopt a VAE-like Encoder

and Decoder

structure. LDMs first compress the input into a latent representation

, and afterwards deploy the diffusion process within the latent space, such that the decoder output

is the reconstructed input

x. With the hallmark of achieving a favorable trade-off between reducing computational and memory costs while maintaining high-resolution and quality synthesis, operating on smaller spatial latent representations of the input has become a popular framework for recent generative models [

37,

38,

39]. Based on the development of DM based image generation, some studies also focus on aerial image synthesis [

6,

38,

40,

41] but they all concentrate on the common weather rather than multiple domain data.

Beyond T2I image generation, Image-to-Image (I2I) Style Transfer [

26,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49] is a practical generative task that aims to extract style and texture information from one reference image and transfer it to another image while preserving semantic content. Prior methods can synthesize vivid and diverse results, such as converting a landscape photo into a painterly oil artwork. However, for de facto domain shifts in aerial imagery, the performance of these methods is limited for the following reasons: (1) Lack of diverse style references: These methods lack style reference imagery for various domains and a unified environment that provides diverse weather and illumination conditions; (2) Inadequate handling of complex domain shifts: While traditional neural network-based style transfer models [

26,

42,

43,

44] can handle atmospheric and illumination changes, they fail to tackle complex domain transfers such as snowy conditions, where physical snow/winter-related elements should be added to the scene, e.g., snow accumulation on rooftops and leafless trees; (3) Content alteration issues: Diffusion model (DM)-based methods [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49] are prone to altering the original semantic content of images, such as shifts in object positions or deformations of large structures. While such alterations are acceptable in human face style transfer or art editing, preserving geo-spatial information is vital for remote sensing analysis. Moreover, such content alterations render the original semantic segmentation masks unusable, resulting in an additional expensive annotation burden.

ControlNet [

35] has recently become a promising approach with the capability to control stable diffusion through various conditioning inputs such as Canny edges, skeletons, and segmentation masks. However, it requires detailed text prompts to achieve consistent target generation in the remote sensing domain. Therefore, in this work, in addition to leveraging segmentation maps as layout conditions, we also utilize them as input for LLM-assisted text descriptor generation. Specifically, for each aerial image’s corresponding segmentation mask, we calculate the pixel ratio for each class and assign each class to one of three levels:

high, medium, or low, then construct a scene elements array as input to the LLM. With this approach, detailed and closely scene-corresponding text prompts are generated.

Though a variety of image generation or style transfer models are developed recently, they are still inadequate and encounter some specific problems on the way to handling domain shift in aerial image processing. However, generative models tend to specialize in a particular task and is equipped with its own merits, e.g., style transfer models can easily change the image scene illumination and atmospheric conditions with a fast inference speed; DM-based methods can greatly edit the images’ content while costing a sequence of sampling steps. Therefore, there is a critical need to adopt multiple models and leverage their advantages to generate diverse weather conditions for aerial imagery while preserving semantic content and geo-spatial information. Recently, Large Language Models (LLMs) [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] have emerged as powerful agents capable of orchestrating complex and multi-step tasks. Several pioneering works [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54] have demonstrated that LLMs can effectively learn to coordinate and utilize diverse tools across multiple modalities and domains, achieving remarkable performance in language processing, computer vision, and other challenging applications. Leveraging LLMs as intelligent agents to automatically select and coordinate appropriate models for addressing diverse domain shift scenarios represents a promising and scalable solution.

1.3. Essence and Contributions of this paper

To address the underestimated domain shift challenge in current remote sensing analysis, particularly in aerial image segmentation, we propose DomainShifter (illustrated in

Figure 3) to overcome the limitation of limited domain variety while eliminating the need for additional annotations on domain-shifted data. Specifically, for multi-weather scene transfer in aerial imagery, given a user’s text input, a LLM agent (e.g., Claude 3.7 Sonnet, GPT-4, DeepSeek R-1, etc.) decomposes the task into simpler steps and systematically plans the procedure for resource identification, appropriate generative tool selection, self-correction, and verification. This oaper comprises the following key components:

Aerial Weather Synthetic Dataset (AWSD): To complement existing datasets and address their limitations, we developed Aerial Weather Synthetic Dataset (AWSD), which introduces controlled variations in weather and lighting based on Unreal Engine [

55]. This dataset provides an ideal benchmark for evaluating the robustness of segmentation models in diverse environmental conditions. Leveraging this dataset, we generated realistic domain-shifted data, which supplements existing aerial image segmentation datasets like ISPRS datasets [

10,

11]. We specifically focused on overcast, foggy, and dusty weather conditions, which are typical domain shift scenarios that change illumination and introduce atmospheric obscuration elements. This allowed us to demonstrate the effects of domain shift and present domain adaptation results.

Latent Aerial Style Transfer model (LAST): Based on the AWSD, we present a latent style transfer model for aerial images. This model transfers domain information from synthetic data. In particular, we first utilize a VAE encoder to simultaneously compress both the style reference image and the semantic content image into latent space. The interaction between the style and content is then processed through transformer blocks in this latent space. Finally, the transformed output is decoded back into the image space using the VAE decoder. We transfer clear weather aerial images from the original ISPRS dataset into overcast, foggy, and dusty weather conditions.

Multi-Modal Snowy Scene Diffusion Model (MSDM): In addition to changing illumination and atmospheric information, diffusion models are more appropriate for generating physical element (object) based scenes such as snowy scenes, e.g., snow-covered roofs and ground. To achieve consistency in image content (including targets of interest and layout), we propose a Multi-Modal Snowy Scene Diffusion Model by leveraging both image conditions and text conditions. Specifically, real aerial images’ segmentation masks are simultaneously served as image conditions controlled by ControlNet [

35] and as initial scene descriptions that provide object information in the images. Then the object information is extended into detailed text prompts by a local-implemented Qwen3-14B [

18] model.

Based on the above three contributions, we handle the scarcity of domain-specific data in aerial image segmentation. Moreover, we benchmark nine different state-of-the-art segmentation models on multi-domain datasets generated by Multi-Weather DomainShifter. Extensive experiments reveal the performance degradation caused by domain shifts, and we successfully adapted model performance in the shifted domain while maintaining its effectiveness in the source domain.

2. Related Work

2.1. Semantic Segmentation

Following the pioneer approach, i.e., Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) [

56], encoder-decoder structure has been a prevalent paradigm for semantic segmentation task. In the early stage, these methods [

57,

58,

59,

60] combined the low level feature and its up-sampling high level to obtain the precise objects boundaries meanwhile capture the global information. Consequently, deeplab-series methods [

61,

62,

63] developed the dilated convolutions to enlarge the receptive field of convolutional layers and further employed spatial pyramid pooling modules to obtain multi-level aggregated feature.

In addition to CNN-based semantic segmentation methods, vision transformer-based approaches [

64,

65,

66,

67] have also become popular due to their exceptional ability to capture long-range contextual information among tokens or embeddings. SETR [

68] employs ViT as its backbone and utilizes a CNN decoder to frame semantic segmentation as a sequence-to-sequence task. Moreover, Segmentor [

69] introduces a point-wise linear layer following the ViT backbone to generate patch-level class logits. Additionally, SegFormer [

70] proposed a novel hierarchically structured Transformer encoder which outputs multiscale features and a MLP decoder to combine both local and global information. Notably, many recent Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) [

71]-based affinity learning methods [

4,

5,

72,

73] are proposed to achieve better feature representation and successfully handle the scale-variation problem [

12,

74] in aerial image segmentation.

2.2. Image Style Transfer

Image style transfer [

26,

42,

43,

75] is a practical research field that applies the style of one reference image to the content of another. Image style transfer aims to generate a transferred image that contains the content, such as shapes, structures, and objects, of the original content image but adopts the style, such as colors, textures, and patterns, of the reference style image. The pioneer method [

42] demonstrates that the hierarchical layers of CNNs can extract content and style information, proposing an optimization-based approach for iterative stylization. However, such optimization-based networks are often limited to a fixed set of styles and cannot adapt to arbitrary new ones. To address this limitation, AdaIN [

76] presents a novel adaptive instance normalization (AdaIN) layer that aligns the mean and variance of the content features with those of the style features. Later work by Chen et al. [

77] employs an internal-external learning scheme with two types of contrastive loss, enabling the generated image to be more visually plausible and harmonious. StyTr

2 [

44] aims to keep the content consistency on art style transfer with a content-aware positional encoding (CAPE) transformer, which increases the computation cost and reduces the inference speed, making it less suitable for high-resolution remote-sensing applications.

Recently, with the great generative capability of latent diffusion models (LDM) [

21,

22,

23,

35,

36], style transfer methods based on LDM have achieved tremendous progress [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. However, except for DM’s inherent deficiency, i.e., low generation efficiency caused by the multi-step diffusion process, these methods cannot keep the precise layout of the original content image. Recently, LoRA-based [

78] techniques [

79,

80,

81,

82,

83] have shown remarkable efficacy in capturing style from a single image. In particular, B-LoRA [

82] and ConsistLoRA [

83] fine-tune two attention layers of up-sampling blocks in SDXL [

22] to separately control content and style. However, for each reference image and content image pair, they [

82,

83] need extra LoRA training, which is inefficient for large-scale aerial image processing.

2.3. Domain Shift

Domain shift [

84] is a well-known challenge that results in unforeseen performance degradation when a model encounters conditions different from those in its training phase. To address this issue, domain generalization (DG) algorithms [

85,

86,

87,

88] have been developed to generalize a model across weather conditions and environments unseen during training, where target domain data is unavailable. Additionally, as a sub-field of transfer learning, domain adaptation (DA) methods [

89,

90,

91] have been proposed to adapt a model trained on a source domain to perform effectively on a target domain. Generally, DA algorithms aim to learn a model from labeled source data that generalizes to a target domain by minimizing the distribution gap between the two domains.

The practical application of domain shift solutions is often hampered by the availability of target domain data, which can be rare and difficult to acquire, especially for diverse weather conditions. Moreover, annotating data for new domains is a laborious and time-consuming task. Therefore, unlike methods that rely on real-world target data, our approach utilizes Unreal Engine [

55] to build a synthetic dataset encompassing a wide variety of weather conditions (details in

Section 4.3). Furthermore, we apply style transfer to augment the existing, finely-annotated ISPRS [

10,

11]. As a result, by performing joint training on both the source and the synthetically shifted domains, our method can effectively mitigate the domain shift problem and its associated performance degradation.

3. Methodology

3.1. Multi-weather DomainShifter

Multi-weather DomainShifter is our proposed comprehensive multi-weather domain transfer system that orchestrates multiple generative models to handle diverse weather change caused domain shift scenarios in aerial imagery. As shown in

Figure 3, the system integrates both data resources and specialized tools, coordinated by a Reasoning and Acting (ReAct) framework [

92] based LLM agent [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] that can interpret and execute complex, multi-step user commands delivered in natural language.

3.1.1. System Architecture

The architecture of Multi-Weather DomainShifter consists of the following three core components:

Image Resources: This component serves as the data foundation for all operations. It is subdivided into three libraries: (1) a Style Image Library containing the target domain style references from our synthetic

AWSD dataset (e.g., overcast, foggy, dusty), detailed in

Section 4.3; (2) a Content Image Library storing the source domain images from real-world datasets like ISPRS [

10,

11]; and (3) a Content Mask Library with the corresponding semantic segmentation masks for the content images. The samples of style references, original content images and corresponding segmentation masks are demonstrated in the top part of

Figure 3.

Tool Resources: As shown in the bottom part of

Figure 3. This is a curated library of specialized generative models and general-purpose utilities. All functions in this tool resources are abstracted as

tools with descriptions, enabling the LLM agent to understand how they should be utilized. The primary generative tools are our proposed (1)

LAST model, designed for efficient style transfer of illumination and atmospheric changes (overcast, foggy, dusty), details in

Section 3.2; and (2) the

MSDM, a multi-modal diffusion model for handling complex physical scene alterations like snowy conditions, details in

Section 3.3. The library is augmented with general tools for tasks such as resource listing and data transferring.

LLM Agent (ReAct Framework): The system’s intelligence is orchestrated by an LLM agent operating on the ReAct paradigm [

92]. This agent synergistically combines reasoning and acting to process user needs, which is illustrated in

Figure 3. For each step, it generates a thought process (reasoning), devises an action to execute, and then observes the outcome of that action. This iterative cycle of Thought → Action → Observation allows the agent to dynamically plan, execute, and self-correct until the user’s goal is fully accomplished.

3.1.2. Agent Workflow

The ReAct-based LLM agent follows a conceptual framework that enables autonomous task decomposition and execution, as illustrated in

Figure 3. The agent’s workflow operates through several key phases:

Task Understanding, where natural language instructions are parsed and resource requirements are identified;

Strategic Planning, where the agent devises optimal execution strategies considering computational efficiency and resource availability;

Tool Selection and Execution, where appropriate generative models are selected and invoked based on the specific domain transfer requirements; and

Quality Assurance, where the agent validates outputs and ensures task completion.

This iterative reasoning-acting cycle enables the agent to handle complex, multi-modal domain transfer scenarios that would traditionally require manual intervention. The agent’s ability to dynamically select between LAST for atmospheric changes and MSDM for physical alterations, while coordinating batch processing and resource management, demonstrates the system’s capacity for intelligent orchestration of heterogeneous generative models. This architecture ensures that Multi-Weather DomainShifter can adapt to diverse user requirements and scale efficiently across different domain shift scenarios.

3.2. LAST

To achieve style transfer for aerial images, accounting for variations in weather conditions and illumination while reducing the computational cost of processing, we propose the

Latent-space

Aerial

Style

Transfer (

LAST) model. This model operates in two spaces: image space and latent space, as depicted in

Figure 4. Specifically, inspired by the Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs) [

21], we first compress the input aerial images into the latent space using a pre-trained VAE. The style transformation is then performed in this latent space.

Overall, this model consists of the following parts: (1) A VAE encoder first compresses both images into a latent space. (2) The resulting latent representations are then flattened into sequences. (3) The core style transfer operation is performed by a latent style transformer that processes these sequences. (4) Finally, a VAE decoder reconstructs the modified latent representation back into the image space, producing the final stylized image. Additionally, the perceptual loss [

75], computed via a pre-trained VGG-19 [

93], is applied to optimize the model.

3.2.1. VAE for Image Compression

We first deploy the same setup as Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs) [

21] to compress images into the latent space via a variational autoencoder (VAE [

31,

32]) pre-trained with a Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence penalty.

Given an image in the image space, the encoder maps x to a latent representation , where , with a down-sampling factor . Subsequently, the decoder reconstructs the image from the latent vector z. Specifically, the process within LAST involves three steps:

1) As illustrated in the top-left part of

Figure 3, an encoder

maps the input content image

and style image

to two separate Gaussian distributions:

The reparameterization trick [

31,

94] is applied to sample the latent vectors

and

from their respective distributions:

where ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication,

is a noise tensor, and both

.

2) Within the latent space, the vectors

and

are processed by the Latent Style Transformer (

LSTrans), as shown in the bottom part of

Figure 3, which outputs a new latent vector

:

where

.

3) Finally, the VAE decoder

reconstructs the stylized image

, where

, as indicated in top-right part of

Figure 3.

3.2.2. Latent Style Transformer

The latent representations, denoted as , are first flattened and embedded into latent sequences, represented as . To transfer domain-specific information from the input style image to the content image while preserving original semantic details—such as objects, boundaries, and spatial relationships—we stack three sequential transformer blocks in the latent space to process the compressed latent representations. Each block consists of the following components: A Multi-head Self-Attention (MSA) module to grasp contextual information within the content features; A Multi-head Cross-Attention (MCA) module to facilitate interaction between the content and style sequences; A Feed-Forward Network (FFN) to enhance the model’s capacity for non-linear transformation and feature combination.

As a result, LSTrans outputs the transferred latent sequence. After being rearranged and projected back to the spatial domain, we obtain the transferred latent representation , which is then decoded into the final image in the image space.

3.2.3. Perceptual Loss for Model Optimization

To guide the model to generate a transferred image

that preserves the content of

while incorporating the style of

, we follow established style transfer approaches [

44,

75,

76,

77] and employ a perceptual loss (also known as VGG loss). The total loss

is a weighted sum of a content loss and a style loss:

where

computes the content discrepancy between

and

, and

computes the style discrepancy between

and

. The weights

and

balance these two components.

Given the pre-trained VGG-19 network and input image

, we extract features at different depths to capture distinct visual characteristics. The first four convolutional layers output low-level features

that encode style and domain information, while the last two convolutional layers output high-level features

that encode semantic content. The content loss and style loss are computed as follows:

where

and

represent the high-level features of the transferred image

and content image

respectively, while

and

represent the low-level features of the transferred image

and style image

respectively.

3.3. MSDM

To address the challenge of generating realistic snowy aerial scenes while maintaining semantic consistency, we propose the

Multi-modal

Snowy Scene

Diffusion

Model (

MSDM). This model integrates ControlNet for structural conditioning with an LLM-assisted scene descriptor to generate contextually rich textual prompts. As illustrated in

Figure 5, MSDM ensures that generated snowy scenes preserve the spatial layout and semantic content of the original imagery while incorporating realistic weather-specific visual effects.

3.3.1. ControlNet for Segmentation Mask Conditioning Diffusion Model

As shown in the

Image Prompt of

Figure 5, we employ ControlNet [

35] for snowy scene generation to maintain structural consistency between original domain and generated snowy images. ControlNet extends pre-trained diffusion models by introducing additional conditional inputs without requiring complete retraining of the base model [

21]. We create a trainable duplicate of the U-Net [

57] encoder blocks that processes spatial conditioning information while keeping the original model parameters frozen. Given a segmentation mask

and noisy latent

at timestep

t obtained by applying the forward diffusion process [

21,

34,

95]on the clean latent representation

, the ControlNet generates additional spatial features:

where

is the ground truth noise and

the cumulative noise schedule parameter.

represents the CLIP [

96] text embedding of the input prompt (shared with the original U-Net),

are the down-sampling block residuals, and

is the middle block residual feature. The ControlNet features are integrated into the U-Net prediction through additive residual connections via zero-initialized convolution layers:

Our training objective follows the standard diffusion loss with ControlNet conditioning:

For our application, we utilize segmentation masks from the merged ISPRS Vaihingen dataset as control signals. Each mask contains semantic classes including buildings, roads, trees, low vegetation, vehicles, and clutters, converted to RGB format using pre-defined color mapping. Please refer to original paper of DDPM[

34], DDIM [

95], StableDiffusion[

21] and ControlNet [

35] for detailed architecture and mechanisms.

3.3.2. LLM-assisted Scene Descriptor

To enhance the quality and realism of generated snowy scenes, we incorporate textual descriptions generated by Qwen3-14B [

18]. Unlike fixed templates or manual annotations, our method performs intelligent scene analysis to generate contextually rich and semantically accurate prompts. As indicated in the bottom part of

Figure 5, the LLM analyzes the segmentation masks and generates detailed scene descriptions that capture the semantic content, which are then used as additional conditioning information for the diffusion model.

Segmentation Mask Analysis The LLM-assisted descriptor begins with quantitative analysis of the segmentation mask. For each semantic class

k, we compute the pixel ratio:

We assign semantic importance levels based on class-adaptive thresholds:

The thresholds are empirically determined based on typical class distributions in aerial imagery. For instance, vehicles require lower thresholds () due to their smaller spatial footprint, while buildings and roads use higher thresholds ().

Structured Prompt Generation We select the top-3 most prominent scene elements based on pixel ratios and construct structured LLM input:

where elements are sorted by descending ratio:

. The LLM input combines scene context with quantitative analysis:

where

c represents the urban/suburban classification,

w specifies the target weather condition (snowy), and

t indicates the temporal context (day/night). The LLM generates structured textual descriptions that serve as conditioning prompts for ControlNet training:

This generated prompt is subsequently encoded by the CLIP text encoder to produce the text embeddings

used in Equations (

10), (

11) and (

12)

4. Experiments

Existing aerial image segmentation datasets, such as ISPRS Vaihingen and Potsdam [

10,

11], serve as widely-used benchmarks, offering high-resolution, annotated images of urban environments. While these datasets are invaluable for training and evaluating segmentation models, they have significant limitations in real-world applications. A key issue is the lack of diversity in environmental conditions. As a result, it does not accurately reflect the variability present in real-world aerial imagery [

5]. Consequently, models trained on these datasets often struggle with domain shifts—environmental changes like weather or lighting variations that can drastically reduce segmentation accuracy.

In real-world scenarios, such as disaster response or urban planning, aerial images are frequently taken under challenging conditions, including overcast, fog, snow. The absence of such environmental diversity in standard datasets limits the robustness and adaptability of segmentation models when deployed in dynamic environments. To address this shortcoming, there is a need for a new dataset that not only mirrors the spatial characteristics of datasets like ISPRS but also includes diverse weather conditions to simulate domain shifts.

The experimental evaluation in this section is organized as follows: We first introduce the ISPRS Vaihingen and Potsdam datasets [

10,

11] in

Section 4.1. In

Section 4.2, we demonstrate the weather change caused domain shift effects on model performances using the Vaihingen dataset.

Section 4.3 and

Section 4.4 introduce our proposed AWSD dataset and the implementation details of our LAST/MSDM models. In

Section 4.5, we conduct ablation study to verify our generated data effectiveness and generalization capability, including intra-distribution experiments and cross-distribution experiments. Finally, in

Section 4.6, we present a comprehensive study to demonstrate the domain adaptation effects.

4.1. ISPRS Dataset

The International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing (ISPRS) Vaihingen dataset and Potsdam datasets [

10,

11] are widely used benchmarks from the ISPRS 2D Semantic Labeling Contest.

The Vaihingen dataset consists of high-resolution true orthophotos of Vaihingen, Germany, with a ground sampling distance (GSD) of 9 cm. It includes 33 image tiles, 16 of which are annotated with six semantic categories: impervious surfaces, buildings, low vegetation, trees, cars, and clutter (background). The Potsdam dataset offers a finer GSD of 5 cm, containing 38 tiles of diverse urban scenes with the same six-class annotation scheme. Specifically, the original high-resolution images were processed into non-overlapping 512×512 patches. The resulting Vaihingen dataset contains 344 patches for training and 398 for validation and Potsdam dataset contains 3,456 patches for training and 2,016 for validation.

For our experiments, we mainly use Vaihingen dataset for numeric comparison, including domain shift effect demonstration (details in

Section 4.2) and final comparison study (details in

Section 4.6). Meanwhile we cooperate both Vaihingen and Potsdam dataset for the capacity verification (details in

Section 4.5) of synthetic data generated by

LAST and

MSDM.

4.2. Effect of Weather Change caused Domain Shift

To demonstrate the effect of weather change caused domain shift, using the original ISPRS training set, we trained the following nine semantic segmentation models: UperNet with three different backbones (Swin Transformer [

65], ResNet-50 [

97], and ViT-Base [

64]), DeepLabV3Plus-ResNet-50, DANet-ResNet-50, PointRend-ResNet-50, FCN-ResNet-50, Segmentor-ViT-Base, and PSPNet-ResNet-50 [

56,

59,

63,

66,

69,

72,

98]. We then evaluated their performance on five domains: the original ISPRS validation set and its style-transferred counterparts {

overcast, foggy, dusty, snowy} generated by

LAST and

MSDM. The overview results are illustrated in the radar chart of

Figure 2 and detailed numeric results in mIOU and mFscore are shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively.

Table 1 and

Table 2 reveal a clear pattern of performance degradation (Compared to the original performance under clear weather) as domain shift severity increases. Under

overcast conditions, where image content remains unchanged but illumination is slightly reduced, all models experience performance drops with average mIoU and mFscore deterioration of

3.35% and

2.62% respectively. When atmospheric conditions are further compromised in

foggy and

dusty scenarios—where both illumination changes and reduced atmospheric visibility occur—more severe domain shift leads to progressively worse performance, with drops of

3.92%/

3.24% and

10.55%/

8.66% for mIoU/mFscore respectively. The most dramatic degradation occurs under

snowy conditions, where scene targets are partially occluded or color-altered (e.g., snow covering rooftops), resulting in substantial performance drops of

28.59% and

25.76% for mIoU and mFscore respectively. These results underscore the critical impact of domain shift on semantic segmentation performance, even when the underlying scene structure remains unchanged.

Notably, our analysis reveals that ViT-based backbones demonstrate superior domain robustness compared to CNN-based alternatives. UperNet-ViT-B exhibits the best resilience under mild weather variations with minimal drops (1.00% mIoU under overcast/foggy conditions), while Segmenter-ViT-B shows the most robust performance under severe conditions (dusty: 4.32% mIoU drop, snowy: 23.95% mIoU drop), significantly outperforming ResNet-50 based models which suffer up to 30.81% mIoU degradation under snowy conditions.

4.3. Synthetic Dataset

To rigorously evaluate model performance under domain shift, we introduce the

Aerial

Weather

Synthetic

Dataset (

AWSD), a synthetic dataset created using Unreal Engine 5 [

55]. AWSD is designed to replicate realistic urban environments modeled based on the Potsdam and Vaihingen datasets. Images are captured from a 200-meter aerial perspective, maintaining consistency with the original benchmarks in terms of viewpoint and object layout. Visual examples of our synthetic data are presented in

Figure 6.

In contrast to the static, clear-sky conditions of the ISPRS datasets [

10,

11], AWSD incorporates a diverse range of environmental variations, including challenging weather conditions as well as different illumination settings. As shown the samples from

Figure 6, from top to bottom, we modulate the weather from

overcast,

foggy to the

dusty based on Unreal Engine 5 environment [

55]. These scenarios were purposefully introduced to assess the adaptability of segmentation models to significant domain shifts. Crucially, AWSD retains the same pixel-level semantic annotations across the six urban categories as ISPRS, ensuring a fair and precise evaluation for both small and large objects in complex environments.

Therefore, by systematically introducing these varied scenarios, AWSD directly addresses the challenge of domain generalization. Its synthetic nature enables the consistent and controllable simulation of environmental variations that are difficult and costly to capture in real-world data acquisition solutions. This makes AWSD a valuable resource for developing and benchmarking aerial segmentation algorithms with enhanced robustness for real-world applications.

4.4. Model Implementation Details

Detailed Set up of LAST The LAST model (introduced in

Section 3.2) uses both source-domain content images and target-domain style references. We use ISPRS Vaihingen as the source-domain content images, while the target-domain style is derived from the 1386 synthetic images from our AWSD dataset (462 images for each weather condition:

overcast, foggy, dusty), which were generated using Unreal Engine 5 [

55].

The latent style transformer (

Section 3.2.2) is trained for 160,000 iterations on two NVIDIA RTX 4090 24GB GPUs using the Adam optimizer [

99] with learning rate 5e-4 and learning rate decay 1e-5. The batch size is set to 8. To preserve their pre-trained representations, the parameters of both the VAE (

Section 3.2.2) and the perceptual VGG-19 feature extractor (

Section 3.2.1) remain frozen throughout the training process.

Moreover, during DomainShifter’s

Tool Selection and Execution process in

Section 3.1.2, we use a strength parameter

in post-processing that controls style intensity through linear interpolation between the transferred/stylized output and the original content image. This process can be formally described as:

where

represents the final output image,

is the transferred image from

LAST and

is the original content image (see

Section 3.2).

Detailed Set up of MSDM MSDM approach (details in

Section 3.3) leverages both visual and textual information as generation condition. We utilize ISPRS Vaihingen as the source domain image set along with its corresponding segmentation masks as image input. Subsequently, based on these segmentation masks, LLM-assisted scene descriptors generate the corresponding text input. We implement the training pipeline with

Accelerate for distributed training support. The ControlNet model is initialized from the pre-trained segmentation ControlNet checkpoint from

Huggingface and then fine-tuned on our weather-augmented dataset.

The base model uses Stable Diffusion v1.5 [

21]. To preserve pre-trained knowledge, the VAE encoder/decoder, U-Net, and CLIP text encoder parameters are frozen, while only ControlNet parameters are optimized, significantly reducing memory requirements. We employ standard MSE loss between predicted and ground truth noise in the latent space. For optimization, we employ 4 × RTX5090 32GB GPUs with AdamW optimizer [

100] (learning rate: 1e-5, weight decay: 0.01, constant warm-up scheduler). The LLM (used in

Section 3.3.2 operates with temperature

and 200-token limit, producing 70-100 word prompts optimized for diffusion model performance. During inference, the model is implemented on two RTX 4090 24GB GPUs with device mapping set as auto. Generation uses DDIM [

95] sampling with 30 steps and guidance scale 7.5. Finally, we generate 5 different sets of snowy scene data with random seeds {46, 50, 51, 53, 54}.

4.5. Ablation Study of Synthetic Data Verification

To evaluate the effectiveness and transferable domain adaptation ability of synthetic data generated by Multi-Weather DomainShifter, we augment both the original ISPRS Vaihingen training set and validation set with generated four different domain images. Meanwhile, we generate the various domain data for ONLY Potsdam validation set, because Potsdam contains only the original data but not any weather shifted data.

For simplicity, we take the prevalent Deeplabv3+ [

63] model with ResNet-50 as backbone [

97] for the ablation study and conduct the following comprehensive seven experiments explained below as Exp. 1 to Exp. 7, where the numerical results of Exp. 1 to Exp. 7 are shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4. Meanwhile the following abbreviations respectively denote VN: Vaihingen, Ori: Original, VN Weather (w/o. snow): atmospheric changed data, i.e., overcast, foggy and dusty, VN All Weather (w. snow): All synthetic data in Vaihingen Training set. Notably, for snowy scene generation by Diffusion Model based

MSDM, we average the 5 sets generated results.

-

Exp.1

Train model on only original Vaihingen training set and test on all domains validation set of Vaihingen;

-

Exp.2

Train model on both original Vaihingen training set and LAST generated atmospheric changed data, i.e., overcast, foggy and dusty, abbreviated in VN weather (w/o. snow);

-

Exp.3

Train model on all the Vaihingen Domain data, including the generation from LAST and 5 different set of snowy scene from MSDM, abbreviated in VN ALL Weather (w. snow);

-

Exp.4

Train model on only original Potsdam training set and test on all domains validation set of Potsdam;

-

Exp.5

Train model on both original Potsdam training set and Vaihingen training set;

-

Exp.6

Train model on both original Potsdam training set and the same various domain data in Exp.2, i.e., VN weather (w/o. snow);

-

Exp.7

Training model on original Potsdam training set and all domains training sets in Exp.3, i.e., VN ALL Weather (w. snow).

In general, the ablation study are divided into two main stages. We first conduct intra-distribution validation within the same geographic distribution (Exp.1-3 for Vaihingen Dataset) and cross-distribution validation by transferring the weather knowledge from generated data in Vaihingen training set into a new, unseen geographical distribution, i.e., ISPRS Potsdam dataset (Exp.4-7).

Stage 1: Intra-Distribution Domain Adaptation

The results from Experiments 1-3 demonstrate the effectiveness of synthetic weather data augmentation for enhancing domain adaptation capabilities within the same geographical distribution.

The introduction of atmospheric weather data without snow (Exp.2) yields consistent performance gains: +3.43% mIoU for overcast, +4.40% mIoU for foggy, and a remarkable +14.31% mIoU improvement for the harsher dusty conditions. Similarly, mFscore improvements of +3.04%, +4.03%, and +12.01% are observed for overcast, foggy, and dusty conditions, respectively. The comprehensive weather augmentation including snow data (Exp.3) further enhances model robustness, achieving a substantial +19.39% mIoU and +17.44% mFscore improvement in snowy conditions while maintaining competitive performance across other weather scenarios. Comparing the baseline model trained solely on original Vaihingen data (Exp.1) with the weather-augmented configurations reveals substantial improvements across all atmospheric conditions.

Stage 2: Cross-Distribution Knowledge Transfer

The cross-distribution validation experiments (Exp.4-7) provide crucial evidence that synthetic data introduces genuine weather-related knowledge rather than causing data leakage artifacts that refers to the potential issue where performance improvements might result from the model simply memorizing training data patterns or exploiting unintended correlations between training and validation sets, rather than learning generalizable weather-related visual features. This stage validates the generalization capability of weather-specific features learned from synthetic data.

A critical observation emerges from Exp.5, in which adding only original Vaihingen real data to Potsdam training set results in performance degradation for overcast (-2.95% mIoU, -2.51% mFscore) and foggy (-3.99% mIoU, -3.16% mFscore) conditions compared to the Potsdam baseline (Exp.4). Meanwhile, dusty domain performance shows improvement (+10.19% mIoU, +10.20% mFscore) and snowy performance remains almost unchanged, suggesting that simple dataset combination without weather-specific augmentation provides limited domain adaptation benefits.

The additional atmospheric weather data without snow (Exp.6) demonstrates the effectiveness of weather-specific knowledge transfer. Performance is restored for overcast and foggy conditions while achieving dramatic improvements in dusty domain (+27.98% mIoU, +26.01% mFscore). Notably, snowy scene performance remains comparable to baseline (+1.23% mIoU, +1.39% mFscore), confirming that without snow-specific training data, the model cannot effectively adapt to snowy conditions through other weather augmentations alone.

The final evaluation (Exp.7) utilizing all synthetic weather data validates the full potential of the proposed approach. Compared to the Potsdam baseline (Exp.4), substantial improvements are achieved across all weather conditions: +2.12% mIoU and +1.86% mFscore for overcast, +1.72% mIoU and +1.50% mFscore for foggy, +29.92% mIoU and +27.47% mFscore for dusty, and +5.87% mIoU and +6.34% mFscore for snowy conditions.

The systematic comparison between Experiments 6-7 against both the baseline (Exp.4) and control group (Exp.5) provides compelling evidence for the effectiveness and generalization capability of synthetic weather data. The results conclusively verify this paper’s essence that incorporating additional domain-specific synthetic data significantly enhances model domain adaptation ability and robustness against domain shift.

Moreover, the successful cross-distribution transfer from Vaihingen to Potsdam particularly demonstrates that synthetic weather knowledge generalizes beyond the original geographical context, indicating that the generated data captures fundamental weather-related visual features rather than dataset-specific artifacts. This generalization capability is essential for practical deployment scenarios where models encounter diverse geographical and environmental conditions not represented in the original training distribution.

4.6. Comprehensive Study of Domain Adaptation

Finally, we employ all the generated domain data to re-train and benchmark all the nine semantic segmentation models on ISPRS Vaihingen dataset [

10,

11]. The comprehensive results are detailed in

Table 5 and

Table 6. In addition, for better visualization, the comparison between degradation results caused by domain shift in

Table 5 and

Table 6 and

Table 1,

Table 2 is shown in the radar chart of

Figure 8. Moreover, some samples of prediction are also visualized in

Figure 7, where we still take Deeplabv3+ [

63] here for simplicity. In particular, we sampled two images from validation set of ISPRS Vaihingen dataset [

10,

11] and compared their prediction results under diverse weather domain with only original training data (denotes as

Prediction w/o. Synthetic data, i.e., domain shift results) and with additonal all the synthetic data from {overcast, foggy, dusty and snowy} (denotes as

Prediction w. Synthetic data, i.e., domain adaptation results).

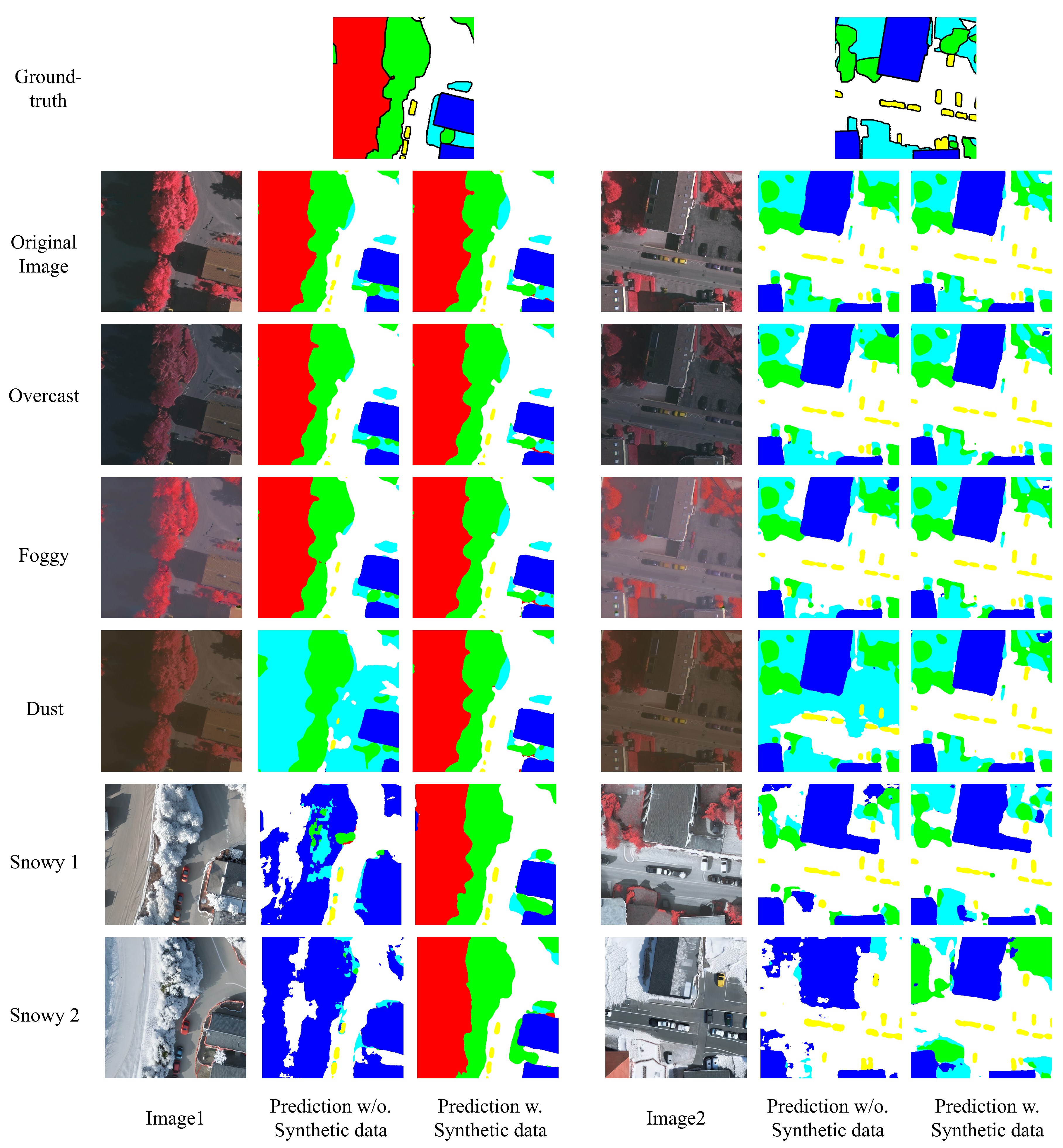

Figure 7.

Visualization of predictions results of two set of samples from Vaihingen dataset. Notably, the Snowy1 and Snowy2 are generated from random seed 46 and 51 respectively. (High-resolution figure, zoom in for a better view).

Figure 7.

Visualization of predictions results of two set of samples from Vaihingen dataset. Notably, the Snowy1 and Snowy2 are generated from random seed 46 and 51 respectively. (High-resolution figure, zoom in for a better view).

Figure 8.

Visualization of domain adaptation recovery (Green Line) with generated various domain-specific data compared to domain shift (Red Line) on the ISPRS Vaihingen datasets. This comparison study, reports both mIoU (left) and mFscore (right) metrics. We average the results of 9 prevalent segmentation methods. (High-resolution figure, zoom in for a better view).

Figure 8.

Visualization of domain adaptation recovery (Green Line) with generated various domain-specific data compared to domain shift (Red Line) on the ISPRS Vaihingen datasets. This comparison study, reports both mIoU (left) and mFscore (right) metrics. We average the results of 9 prevalent segmentation methods. (High-resolution figure, zoom in for a better view).

Our primary evaluation focuses on the robustness and domain adaptation capacity of these models against domain shifts. By retraining on the augmented data, the models exhibit significant performance improvements on the shifted validation sets. As demonstrated in

Figure 7, the predictions (i.e., segmentation masks) of Deeplabv3+ without any synthetic data (shown in the column

Prediction w/o. Synthetic data) gradually deteriorate as the weather conditions progress from easy to difficult. When the weather becomes dusty, where illumination and atmospheric conditions are altered, the shadow regions in

Image1 and

Image2 cannot be correctly handled by the model. Additionally, when the weather shifts to snowy scenes where objects (e.g., the tree in Image1 and buildings in Image2) become white or are covered by snow, the model fails to classify them correctly. In contrast, under the same conditions, after retraining the model with synthetic data from all shifted domains, the model demonstrates clear robustness across all weather conditions (shown in the column

Prediction w. Synthetic data).

Numerically, compared to the deterioration results in

Table 1 and

Table 2 (Red Line in the radar chart of

Figure 8), substantial improvements are achieved across all weather conditions:

+2.75% mIoU and

+2.47% mFscore for overcast,

+3.48% mIoU and

+3.20% mFscore for foggy,

+10.53% mIoU and

+8.89% mFscore for dusty, and

+17.55% mIoU and

+15.74% mFscore for snowy conditions. The results demonstrate significant performance improvement with the synthetic weather data, meanwhile, the model performances on the original real set keeps steady. The comprehensive results demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposals for improving robustness against various domain shifts and enhancing domain adaptation capability.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we have addressed the critical challenge of domain shift in aerial image segmentation by proposing Multi-Weather DomainShifter, a comprehensive multi-weather domain transfer system. Equipped with AWSD, LAST and MSDM, our approach leverages synthetic style transfer coordinated by an LLM agent to enhance model robustness without requiring manual annotation of target domain data. The LLM agent coordination proves valuable in automatically selecting appropriate tools based on specific domain transfer requirements, making the system more practical for real-world deployment where diverse weather conditions need to be handled systematically.

Extensive experiments on nine state-of-the-art segmentation models demonstrate the effect of weather change caused domain shift, then ablation study validate our approach’s effectiveness, and the final comprehensive study demonstrate significant improvements in domain-shifted scenarios while preserving performance in the original domain.

As a result, this paper provides a practical and cost-effective solution for improving the real-world deployability of aerial segmentation models, addressing the critical gap between laboratory benchmarks and practical applications in diverse environmental conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W.; methodology, Y.W.; software, Y.W.; validation, Y.W.; formal analysis, Y.W.; investigation, Y.W.; data curation, R.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W.; writing—review and editing, H.I. and J.O.; visualization, Y.W.; supervision, H.I. and J.O.; project administration, J.O.; funding acquisition, J.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans.

Data Availability Statement

The code and datasets presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions that helped improve the quality of this paper. Moreover, we note that the Latent Aerial Style Transfer (LAST) model, which is one component of our comprehensive system, has been published in The International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods 2025, Porto, Portugal, February, 23 to 25, 2025. The paper title is "LAST: Utilizing Synthetic Image Style Transfer to Tackle Domain Shift in Aerial Image Segmentation", meanwhile all the authors keep the same in the version submitted to MDPI Journal of Imaging including Yubo Wang, Ruijia Wen, Hiroyuki Ishii and Jun Ohya. Meanwhile, this paper presents a substantially expanded work that integrates LAST with additional novel components (Multi-Modal Snowy Scene Diffusion model and LLM agent coordination) to form a complete multi-weather domain transfer system

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIS |

Aerial Image Segmentation |

| AWSD |

Aerial Weather Synthetic Dataset |

| LAST |

Latent Aerial Style Transfer |

| MSDM |

Multi-Modal Snowy Scene Diffusion Model |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| VAE |

Variational Autoencoder |

| GAN |

Generative Adversarial Network |

| LDM |

Latent Diffusion Model |

| DM |

Diffusion Model |

| T2I |

Text-to-Image |

| I2I |

Image-to-Image |

| MSA |

Multi-head Self-Attention |

| MCA |

Multi-head Cross-Attention |

| FFN |

Feed-Forward Network |

| FCN |

Fully Convolutional Network |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| ViT |

Vision Transformer |

| ISPRS |

International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing |

| mIoU |

mean Intersection over Union |

| GSD |

Ground Sampling Distance |

References

- Pi, Y.; Nath, N.D.; Behzadan, A.H. Convolutional neural networks for object detection in aerial imagery for disaster response and recovery. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2020, 43, 101009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Nakano, Y.; Nishimatsu, K.; Hasegawa, K.; Ohya, J. Context Enhanced Traffic Segmentation: traffic jam and road surface segmentation from aerial image. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 14th Image, Video, and Multidimensional Signal Processing Workshop (IVMSP). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–5.

- Liang, Y.; Li, X.; Tsai, B.; Chen, Q.; Jafari, N. V-FloodNet: A video segmentation system for urban flood detection and quantification. Environmental Modelling & Software 2023, 160, 105586. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; He, H.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Cheng, G.; Shi, J.; Weng, L.; Tong, Y.; Lin, Z. Pointflow: Flowing semantics through points for aerial image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021, pp. 4217–4226.

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Nakano, Y.; Hasegawa, K.; Ishii, H.; Ohya, J. MAC: Multi-Scales Attention Cascade for Aerial Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods, ICPRAM 2024. Science and Technology Publications, Lda, 2024, pp. 37–47.

- Toker, A.; Eisenberger, M.; Cremers, D.; Leal-Taixé, L. Satsynth: Augmenting image-mask pairs through diffusion models for aerial semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 27695–27705.

- Dai, D.; Van Gool, L. Dark model adaptation: Semantic image segmentation from daytime to nighttime. In Proceedings of the 2018 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC). IEEE, 2018, pp. 3819–3824.

- Michaelis, C.; Mitzkus, B.; Geirhos, R.; Rusak, E.; Bringmann, O.; Ecker, A.S.; Bethge, M.; Brendel, W. Benchmarking robustness in object detection: Autonomous driving when winter is coming. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.07484 2019.

- Sun, T.; Segu, M.; Postels, J.; Wang, Y.; Van Gool, L.; Schiele, B.; Tombari, F.; Yu, F. SHIFT: a synthetic driving dataset for continuous multi-task domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 21371–21382.

- International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing (ISPRS). ISPRS 2D Semantic Labeling Contest. [Online]. Available: https://www.isprs.org/resources/datasets/benchmarks/UrbanSemLab/semantic-labeling.aspx. Accessed on: July 21, 2025.

- Rottensteiner, F.; Sohn, G.; Gerke, M.; Wegner, J.D.; Breitkopf, U.; Jung, J. Results of the ISPRS benchmark on urban object detection and 3D building reconstruction. ISPRS journal of photogrammetry and remote sensing 2014, 93, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas Zamir, S.; Arora, A.; Gupta, A.; Khan, S.; Sun, G.; Shahbaz Khan, F.; Zhu, F.; Shao, L.; Xia, G.S.; Bai, X. isaid: A large-scale dataset for instance segmentation in aerial images. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, 2019, pp. 28–37.

- Brown, T.B. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.14165 2020.

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774 2023.

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971 2023.

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09288 2023.

- Bai, J.; Bai, S.; Chu, Y.; Cui, Z.; Dang, K.; Deng, X.; Fan, Y.; Ge, W.; Han, Y.; Huang, F.; et al. Qwen technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.16609 2023.

- Yang, A.; Li, A.; Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, B.; Gao, C.; Huang, C.; Lv, C.; et al. Qwen3 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.09388 2025.

- Liu, A.; Feng, B.; Xue, B.; Wang, B.; Wu, B.; Lu, C.; Zhao, C.; Deng, C.; Zhang, C.; Ruan, C.; et al. Deepseek-v3 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.19437 2024.

- Guo, D.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Song, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, R.; Zhu, Q.; Ma, S.; Wang, P.; Bi, X.; et al. Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.12948 2025.

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 10684–10695.

- Podell, D.; English, Z.; Lacey, K.; Blattmann, A.; Dockhorn, T.; Müller, J.; Penna, J.; Rombach, R. Sdxl: Improving latent diffusion models for high-resolution image synthesis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.01952 2023.

- Ramesh, A.; Dhariwal, P.; Nichol, A.; Chu, C.; Chen, M. Hierarchical text-conditional image generation with clip latents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.06125 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Betker, J.; Goh, G.; Jing, L.; Brooks, T.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Ouyang, L.; Zhuang, J.; Lee, J.; Guo, Y.; et al. Improving image generation with better captions. Computer Science. https://cdn. openai. com/papers/dall-e-3. pdf 2023, 2, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. Advances in neural information processing systems 2014, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 2223–2232.

- Zhang, H.; Xu, T.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Metaxas, D.N. Stackgan: Text to photo-realistic image synthesis with stacked generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 5907–5915.

- Brock, A. Large Scale GAN Training for High Fidelity Natural Image Synthesis. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.11096 2018.

- Karras, T.; Laine, S.; Aila, T. A style-based generator architecture for generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 4401–4410.

- Zhang, H.; Goodfellow, I.; Metaxas, D.; Odena, A. Self-attention generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2019, pp. 7354–7363.

- Kingma, D.P. Auto-encoding variational bayes. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6114 2013.

- Vahdat, A.; Kautz, J. NVAE: A deep hierarchical variational autoencoder. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 19667–19679. [Google Scholar]

- Sohl-Dickstein, J.; Weiss, E.; Maheswaranathan, N.; Ganguli, S. Deep Unsupervised Learning using Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning; Bach, F.; Blei, D., Eds., Lille, France, 07–09 Jul 2015; Vol. 37, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 2256–2265.

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Rao, A.; Agrawala, M. Adding conditional control to text-to-image diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2023, pp. 3836–3847.

- Luo, Z.; Gustafsson, F.K.; Zhao, Z.; Sjölund, J.; Schön, T.B. Refusion: Enabling large-size realistic image restoration with latent-space diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023, pp. 1680–1691.

- Li, T.; Chang, H.; Mishra, S.; Zhang, H.; Katabi, D.; Krishnan, D. Mage: Masked generative encoder to unify representation learning and image synthesis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 2142–2152.

- Khanna, S.; Liu, P.; Zhou, L.; Meng, C.; Rombach, R.; Burke, M.; Lobell, D.; Ermon, S. Diffusionsat: A generative foundation model for satellite imagery. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.03606 2023.

- Peebles, W.; Xie, S. Scalable diffusion models with transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 4195–4205.

- Xu, Y.; Yu, W.; Ghamisi, P.; Kopp, M.; Hochreiter, S. Txt2Img-MHN: Remote sensing image generation from text using modern Hopfield networks. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2023, 32, 5737–5750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastry, S.; Khanal, S.; Dhakal, A.; Jacobs, N. Geosynth: Contextually-aware high-resolution satellite image synthesis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 460–470.

- Gatys, L.A.; Ecker, A.S.; Bethge, M. Image style transfer using convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 2414–2423.

- Li, C.; Wand, M. Precomputed real-time texture synthesis with markovian generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision. Springer, 2016, pp. 702–716.

- Deng, Y.; Tang, F.; Dong, W.; Ma, C.; Pan, X.; Wang, L.; Xu, C. Stytr2: Image style transfer with transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 11326–11336.

- Brooks, T.; Holynski, A.; Efros, A.A. InstructPix2Pix: Learning To Follow Image Editing Instructions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2023, pp. 18392–18402.

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Xing, W. StyleDiffusion: Controllable Disentangled Style Transfer via Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), October 2023, pp. 7677–7689.

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, N.; Tang, F.; Huang, H.; Ma, C.; Dong, W.; Xu, C. Inversion-based style transfer with diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023, pp. 10146–10156.

- Sohn, K.; Jiang, L.; Barber, J.; Lee, K.; Ruiz, N.; Krishnan, D.; Chang, H.; Li, Y.; Essa, I.; Rubinstein, M.; et al. Styledrop: Text-to-image synthesis of any style. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.; Hyun, S.; Heo, J.P. Style Injection in Diffusion: A Training-free Approach for Adapting Large-scale Diffusion Models for Style Transfer. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2024, pp. 8795–8805.

- Shen, Y.; Song, K.; Tan, X.; Li, D.; Lu, W.; Zhuang, Y. Hugginggpt: Solving ai tasks with chatgpt and its friends in hugging face. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 38154–38180. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, J.; Wu, J.; Chen, W.; Ren, Y.; Li, H.; Wu, H.; Xiao, X.; Wang, R.; Wen, S. Diffusiongpt: Llm-driven text-to-image generation system. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.10061 2024.

- Liu, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Li, Q.; Yu, J. others. Internchat: Solving vision-centric tasks by interacting with chatbots beyond language. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.05662 2023.

- Wang, Z.; Xie, E.; Li, A.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, Z. Divide and conquer: Language models can plan and self-correct for compositional text-to-image generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.15688 2024.

- Wang, Z.; Li, A.; Li, Z.; Liu, X. Genartist: Multimodal llm as an agent for unified image generation and editing. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 128374–128395. [Google Scholar]

- Unreal, E. Unreal Engine. [Online], 2025. Available: https://www.unrealengine.com/en-us. Accessed on: July 21, 2025.

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR), 2015, pp. 3431–3440.

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention. Springer, 2015, pp. 234–241.

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. Segnet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (PAMI) 2017, 39, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR), 2017, pp. 2881–2890.

- Lin, G.; Milan, A.; Shen, C.; Reid, I. Refinenet: Multi-path refinement networks for high-resolution semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 1925–1934.

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Deeplab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected crfs. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2017, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Rethinking atrous convolution for semantic image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.05587 2017.

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 801–818.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 2020.

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2021, pp. 10012–10022.

- Fu, J.; Liu, J.; Tian, H.; Li, Y.; Bao, Y.; Fang, Z.; Lu, H. Dual attention network for scene segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR), 2019, pp. 3146–3154.

- Guo, M.H.; Lu, C.Z.; Hou, Q.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, M.M.; Hu, S.M. Segnext: Rethinking convolutional attention design for semantic segmentation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 1140–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Lu, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Feng, J.; Xiang, T.; Torr, P.H.; et al. Rethinking semantic segmentation from a sequence-to-sequence perspective with transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR), 2021, pp. 6881–6890.

- Strudel, R.; Garcia, R.; Laptev, I.; Schmid, C. Segmenter: Transformer for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 7262–7272.

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPs) 2021, 34, 12077–12090. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR), 2017, pp. 2117–2125.

- Xiao, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, B.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, J. Unified perceptual parsing for scene understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 418–434.

- Zheng, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, A. Foreground-aware relation network for geospatial object segmentation in high spatial resolution remote sensing imagery. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR), 2020, pp. 4096–4105.

- Xia, G.S.; Bai, X.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Z.; Belongie, S.; Luo, J.; Datcu, M.; Pelillo, M.; Zhang, L. DOTA: A large-scale dataset for object detection in aerial images. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 3974–3983.

- Johnson, J.; Alahi, A.; Fei-Fei, L. Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision. Springer, 2016, pp. 694–711.

- Huang, X.; Belongie, S. Arbitrary style transfer in real-time with adaptive instance normalization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 1501–1510.

- Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zuo, Z.; Li, A.; Xing, W.; Lu, D.; et al. Artistic style transfer with internal-external learning and contrastive learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 26561–26573. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; et al. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, V.; Ruiz, N.; Cole, F.; Lu, E.; Lazebnik, S.; Li, Y.; Jampani, V. Ziplora: Any subject in any style by effectively merging loras. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2024, pp. 422–438.

- Liu, C.; Shah, V.; Cui, A.; Lazebnik, S. Unziplora: Separating content and style from a single image. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.04465 2024.

- Jones, M.; Wang, S.Y.; Kumari, N.; Bau, D.; Zhu, J.Y. Customizing text-to-image models with a single image pair. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH Asia 2024 Conference Papers, 2024, pp. 1–13.

- Frenkel, Y.; Vinker, Y.; Shamir, A.; Cohen-Or, D. Implicit style-content separation using b-lora. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2024, pp. 181–198.

- Chen, B.; Zhao, B.; Xie, H.; Cai, Y.; Li, Q.; Mao, X. Consislora: Enhancing content and style consistency for lora-based style transfer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.10614 2025.

- Ben-David, S.; Blitzer, J.; Crammer, K.; Kulesza, A.; Pereira, F.; Vaughan, J.W. A theory of learning from different domains. Machine learning 2010, 79, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, A.; Zhou, T.; Malisiewicz, T.; Efros, A.A.; Torralba, A. Undoing the damage of dataset bias. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2012, pp. 158–171.

- Muandet, K.; Balduzzi, D.; Schölkopf, B. Domain generalization via invariant feature representation. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2013, pp. 10–18.

- Tobin, J.; Fong, R.; Ray, A.; Schneider, J.; Zaremba, W.; Abbeel, P. Domain randomization for transferring deep neural networks from simulation to the real world. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems (IROS). IEEE, 2017, pp. 23–30.

- Volpi, R.; Namkoong, H.; Sener, O.; Duchi, J.C.; Murino, V.; Savarese, S. Generalizing to unseen domains via adversarial data augmentation. Advances in neural information processing systems 2018, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng, E.; Hoffman, J.; Saenko, K.; Darrell, T. Adversarial discriminative domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 7167–7176.