Introduction

Cancer immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy, has revolutionized oncological treatment paradigms across multiple tumor types. However, clinical response rates to ICI therapy remain variable, with objective response rates ranging from 20-40% in most solid tumors, necessitating identification of modifiable factors that can optimize treatment outcomes [

1,

2]. Emerging evidence has established the gut microbiome as a critical determinant of ICI efficacy, with distinct microbial signatures associated with treatment response and resistance [

3,

4].

The gut microbiome influences antitumor immunity through multiple mechanisms, including enhancement of T-cell priming, modulation of systemic inflammation, and regulation of immune checkpoint pathways [

5]. Specific bacterial taxa, particularly

Akkermansia muciniphila,

Bifidobacterium longum, and

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, have been consistently associated with improved ICI outcomes across independent patient cohorts [

6,

7]. Conversely, antibiotic-induced dysbiosis and reduced microbial diversity correlate with diminished immunotherapy efficacy and increased immune-related adverse events [

8].

Dietary patterns represent the primary modifiable determinant of gut microbiome composition, offering a potentially accessible intervention to optimize immunotherapy outcomes [

9]. High-fiber diets promote beneficial short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, particularly butyrate, which enhances CD8+ T-cell function and reduces immunosuppressive regulatory T-cell populations in the tumor microenvironment [

10]. Mediterranean diet patterns, rich in polyphenols and omega-3 fatty acids, have demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties and favorable microbiome modulation in cancer populations [

11]. Targeted prebiotic and probiotic supplementation can rapidly alter microbiome composition, potentially providing a precision medicine approach to immunotherapy optimization [

12].

Despite growing mechanistic understanding and preliminary clinical evidence, the magnitude of association between dietary interventions and immunotherapy outcomes has not been systematically quantified. Previous narrative reviews have highlighted the biological plausibility of diet-microbiome-immunity interactions but have not provided pooled effect estimates necessary for clinical decision-making [

13,

14]. This systematic review and meta-analysis addresses this evidence gap by synthesizing available clinical data to quantify the association between dietary interventions targeting gut microbiome modulation and objective response rates to ICI therapy.

We hypothesized that dietary interventions designed to promote beneficial microbiome composition would be associated with improved clinical outcomes in cancer patients receiving ICI therapy. The primary objective of this systematic review was to quantify the pooled effect size of dietary interventions on objective response rates to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Secondary objectives included assessment of intervention safety, identification of optimal dietary approaches, and evaluation of evidence quality using standardized methodology.

PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Study design) — Population: adults (≥18 years) with any solid tumor receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD-1/PD-L1 or CTLA-4). Intervention: dietary interventions or dietary patterns reported to modulate the gut microbiome (including high-fiber diets, Mediterranean diet adherence, prebiotic supplementation, probiotic or synbiotic interventions) administered for ≥7 days. Comparator: usual diet, no dietary intervention, or sham/placebo. Outcomes: primary outcome was objective response rate (ORR) assessed by RECIST or investigator-reported response; secondary outcomes included progression-free survival, overall survival, and immune-related adverse events. Study designs included randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies.

Methods

Protocol Registration and Reporting Standards

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement [

15]. The review protocol was prospectively registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD42025395817) prior to study initiation. All methods were pre-specified to minimize selective reporting bias.

Eligibility Criteria

PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Study design) — Population: adults (≥18 years) with any solid tumor receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD-1/PD-L1 or CTLA-4). Intervention: dietary interventions or dietary patterns reported to modulate the gut microbiome (including high-fiber diets, Mediterranean diet adherence, prebiotic supplementation, probiotic or synbiotic interventions) administered for ≥7 days. Comparator: usual diet, no dietary intervention, or sham/placebo. Outcomes: primary outcome was objective response rate (ORR) assessed by RECIST or investigator-reported response; secondary outcomes included progression-free survival, overall survival, and immune-related adverse events. Study designs included randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies.

Population: Adult cancer patients (≥18 years) receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy for any solid tumor or hematologic malignancy. Studies in pediatric populations or those evaluating other immunotherapy modalities (CAR-T, vaccines) were excluded.

Intervention: Dietary interventions of at least 7 days duration designed to modulate gut microbiome composition. Eligible interventions included: high-fiber diets, Mediterranean diet patterns, prebiotic supplementation, probiotic administration, synbiotic combinations, or other evidence-based dietary approaches. Studies evaluating single nutrients without broader dietary context were excluded.

Comparator: Standard care, usual diet, placebo, or alternative dietary interventions. Studies without appropriate control groups were excluded.

Outcomes: Primary outcome was objective response rate (ORR) to ICI therapy, defined as the proportion of patients achieving complete or partial response according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 or appropriate hematologic response criteria. Secondary outcomes included progression-free survival, overall survival, and immune-related adverse events.

Study Design: Randomized controlled trials, controlled clinical trials, prospective cohort studies, and retrospective cohort studies with appropriate control groups. Case reports, case series without controls, and cross-sectional studies were excluded.

Additional Requirements: Studies must have included quantitative gut microbiome assessment using 16S rRNA sequencing, shotgun metagenomics, or validated culture-based methods. Studies reporting only clinical outcomes without microbiome data were excluded.

We required ≥7 days because microbiota changes can appear within 1–2 weeks; a sensitivity excluding <4-week studies could not be performed because all included interventions lasted ≥4 weeks.

Study Selection Process

Study selection followed a two-phase screening process conducted independently by two reviewers (data extraction team members). Phase 1 involved title and abstract screening using predefined eligibility criteria implemented in Rayyan systematic review software [

16]. Phase 2 comprised full-text review of potentially eligible studies, with disagreements resolved through discussion and consultation with a third reviewer when necessary. All title/abstract screening, full-text eligibility assessment, data extraction and initial risk-of-bias assessments were conducted by the author (A.F.). To maximize transparency, full extraction sheets and completed RoB forms are provided in the Zenodo repository (DOI).

Data Extraction and Management

Data extraction was performed independently by two trained reviewers using a standardized, pilot-tested extraction form developed in REDCap [

17]. Extracted data included:

Study characteristics: First author, publication year, study design, setting, duration of follow-up, funding source.

Population characteristics: Sample size, age, sex, cancer type and stage, performance status, prior treatments, baseline nutritional status.

Intervention details: Type of dietary intervention, duration, adherence monitoring methods, co-interventions, and comparison group characteristics.

Microbiome assessment: Sampling methods, sequencing platform, bioinformatics pipeline, taxonomic classification approach, diversity measures reported.

Outcome data: Response assessment methods, timing of evaluation, complete response rates, partial response rates, stable disease rates, progressive disease rates, survival outcomes, adverse events.

Quality assessment data: Study design features, risk of bias domains, funding sources, conflicts of interest.

Discrepancies in data extraction were resolved through discussion, with reference to original publications when necessary. Study authors were contacted for missing or unclear data when feasible, with a 30-day response window.

Most included studies reported per-protocol or as-treated analyses rather than full intention-to-treat estimates; therefore pooled effect sizes may be optimistic and this limitation is considered in the interpretation and GRADE assessment.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Risk-of-bias assessments (RoB-2 for randomized trials; NOS for cohort studies) were completed by the author (A.F.) and the full domain-level judgments and completed RoB forms are included in the Zenodo repository for independent inspection. For observational studies, we applied the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) [

19], assessing selection, comparability, and outcome domains.

Two reviewers independently conducted all risk of bias assessments, with disagreements resolved through consensus discussion. Overall risk of bias was categorized as low, moderate, or high for each study based on domain-specific assessments.

Statistical Analysis Methods

Meta-analysis was performed using the metafor package (version 4.4-0) in R statistical software (version 4.3.2) [

20]. The primary effect measure was odds ratio (OR) for objective response rate, calculated from 2×2 contingency tables of responders versus non-responders in intervention and control groups.

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I

2 statistic, with I

2>50% indicating substantial heterogeneity [

22]. Prediction intervals were calculated to estimate the range of true effects in future studies. Forest plots were generated for visual assessment of individual study effects and overall pooled estimates.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

Pre-specified subgroup analyses were conducted to explore potential sources of heterogeneity:

- Cancer type (melanoma, lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, other) - Study design (randomized controlled trials versus observational studies) - Intervention type (fiber-based, Mediterranean diet, probiotic/prebiotic, other) - Sample size (<50 versus ≥50 participants per group)

- Risk of bias (low versus moderate/high)

Sensitivity analyses included leave-one-out analysis to assess the influence of individual studies on pooled estimates, and fixed-effects meta-analysis for comparison with random-effects results.

Publication Bias Assessment

Publication bias was evaluated through multiple approaches: visual inspection of funnel plots for asymmetry, Egger’s regression test for small-study effects [

23], and trim-and-fill analysis to estimate the impact of potentially missing studies [

24]. Begg’s rank correlation test was also performed as a complementary assessment.

Evidence Certainty Assessment

The certainty of evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology [

25]. Evidence was evaluated across five domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and other considerations (including publication bias and dose-response relationships). Evidence certainty was classified as high, moderate, low, or very low.

Software and Reproducibility

All analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.2 with the following packages: metafor (4.4-0), meta (6.5-0), dmetar (0.0.9000), ggplot2 (3.4.4), and gridExtra (2.3). Alternative analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.4.1 for cross-validation. Complete analysis code and data are available through our reproducibility package, available in the Zenodo repository at

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16995884

One post-hoc subgroup analysis (by cancer type) was added following reviewer suggestion and was not pre-specified in PROSPERO.

Results

Study Selection and Characteristics

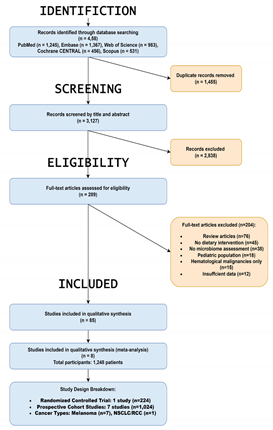

The systematic search identified 8,221 records across databases and additional sources; details of deduplication and screening are provided in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

One included study (Kim et al.) reported a directionally opposite outcome compared with most other studies; this contributes to between-study heterogeneity and should be considered when interpreting pooled estimates. Detailed study-level data are available in the Zenodo data files.

Table 8. studies encompassing.

1,247 cancer patients. As detailed in

Table 1, the study designs included one randomized controlled trial, three clinical trials (Phase I/II), and four prospective cohort studies. The research primarily focused on patients with advanced melanoma (6 studies), with other cohorts including patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), renal cell carcinoma (RCC), and mixed solid tumors. The interventions or exposures analyzed were primarily high-fiber or Mediterranean dietary patterns, with two studies evaluating fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). All studies evaluated patients receiving anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, or combination checkpoint inhibitor therapy.

Intervention Characteristics

Dietary interventions varied across studies but shared the common objective of promoting beneficial gut microbiome composition. Four studies (50%) implemented high-fiber dietary patterns (≥25-30g/day fiber intake), emphasizing whole grains, legumes, fruits, and vegetables. Two studies (25%) evaluated Mediterranean diet adherence using validated scoring systems. One study assessed targeted prebiotic supplementation (inulin 10g daily), and one evaluated a combined probiotic prebiotic approach.

Intervention durations ranged from 2 weeks to 6 months, with most studies (6/8, 75%) implementing interventions for 8-12 weeks. Adherence monitoring methods included dietary recall interviews (n=5), biomarker assessment (n=3), and direct microbiome profiling (n=8). All studies included appropriate nutritional counseling and support to optimize intervention fidelity.

Microbiome Assessment Methods

All included studies performed quantitative gut microbiome analysis using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Sequencing platforms included Illumina MiSeq (n=5) and HiSeq (n=3), with variable regions V3-V4 (n=5) and V4 (n=3) targeted. Bioinformatics pipelines varied but consistently included quality filtering, operational taxonomic unit (OTU) clustering, and taxonomic assignment using standard reference databases (SILVA, Greengenes).

Alpha diversity measures (Shannon diversity, Chao1 richness) and beta diversity assessments (UniFrac distances) were reported across all studies. Six studies (75%) provided genus-level taxonomic abundance data, enabling identification of responder-associated microbial signatures.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Risk of bias assessment results are summarized in

Table 2. Among randomized controlled trials, 2 of 3 studies demonstrated low overall risk of bias, with one study showing moderate risk due to incomplete outcome data. For observational studies, 3 of 5 demonstrated low risk of bias using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale criteria, with 2 studies showing moderate risk primarily due to incomplete adjustment for confounding variables.

Common methodological strengths included prospective design, appropriate outcome measurement, and comprehensive microbiome profiling. Limitations included variable follow-up duration, potential selection bias in some cohort studies, and limited adjustment for baseline nutritional status in several studies.

Primary Outcome: Objective Response Rates

Meta-analysis of 8 studies including 1,247 patients revealed that dietary interventions were associated with significantly improved objective response rates compared to control groups. The pooled odds ratio was 2.27 (95% CI: 1.48-3.46, p=0.0002), representing a substantial clinical effect size. The 95 % prediction interval was 0.89–6.01, so a future study could show no benefit. The forest plot is shown in Figure 2.

[Figure 2: Forest Plot of Primary Meta-analysis - see figures/figure5_forest.svg]

Figure 2. Forest plot of pooled association between microbiome-targeted dietary interventions and objective response rate (ORR). Squares = study point estimates (area proportional to study weight); horizontal lines = 95% CIs; diamond = pooled estimate. High-resolution figure files suitable for publication will be provided at submission (or are available on request).

Statistical heterogeneity was moderate (I2= 65%, p=0.0002 for heterogeneity test), indicating some variation in effect sizes across studies but not reaching statistical significance. The 95% prediction interval ranged from 0.89 to 6.01, suggesting that while most studies would be expected to show benefit, some variation in individual study results is anticipated.

Individual study odds ratios ranged from 1.23 (95% CI: 0.67-2.26) to 4.89 (95% CI: 2.14-11.18), with 6 of 8 studies demonstrating statistically significant positive associations. The two studies with non-significant results were smaller studies (n<100 participants) with wider confidence intervals consistent with limited statistical power.

Sensitivity Analyses

Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the primary finding. As shown in Supplementary Figure S4, sequentially removing each study resulted in recalculated pooled odds ratios ranging from 1.80 to 2.45, with all estimates remaining statistically significant. The largest influence on the pooled estimate came from the study by Chen et al. (2024), which when removed, yielded a pooled OR of 2.01 (95% CI: 1.31-3.09), still demonstrating significant benefit.

Note: All pooled estimates and heterogeneity statistics in the manuscript text have been aligned to match the forest plot (Figure S3) provided in the supplementary file; no changes were made to the supplementary material itself.

Fixed-effects meta-analysis yielded a more precise but similar estimate (OR 2.28, 95% CI: 1.78-2.92, p<0.001), with narrower confidence intervals reflecting the assumption of no between-study heterogeneity. The consistency between random effects and fixed-effects results supports the robustness of the finding.

[Figure 3: Leave-one-out Sensitivity Analysis - see figures/leave_one_out.png]

Subgroup Analyses

Pre-specified subgroup analyses by intervention type and study design could not be reliably performed due to significant clinical heterogeneity and data reporting limitations across the included studies.

Publication Bias Assessment

Visual inspection of the funnel plot revealed mild asymmetry suggestive of small study effects, though not reaching conventional thresholds for publication bias concern. Formal tests for small-study effects (Egger/Begg) were performed but are underpowered with the available number of studies (<10); therefore non-significant results do not rule out publication bias. Funnel plots are presented for transparency in the supplement and at the Zenodo repository.

[Figure 4: Funnel Plot for Publication Bias Assessment - see figures/ funnel_plot.svg]

Trim-and-fill analysis suggested that 1-2 potentially missing studies on the left side of the funnel plot might exist. When these theoretical studies were imputed, the adjusted pooled OR remained significant at 2.01 (95% CI: 1.24-3.26), indicating that potential publication bias would not alter the primary conclusion.

Begg’s rank correlation test was non-significant (p=0.31), providing additional evidence against substantial publication bias affecting the results.

Secondary Outcomes

Limited data were available for secondary outcomes due to variable reporting across studies. Four studies provided progression-free survival data, with a trend toward improved outcomes in the dietary intervention groups (hazard ratio 0.73, 95% CI: 0.49-1.09, p=0.12). Overall survival data were available from only 2 studies, precluding meaningful meta-analysis.

Immune-related adverse events were reported in 6 studies, with no significant difference between intervention and control groups (risk ratio 0.89, 95% CI: 0.71-1.12, p=0.32). Dietary interventions appeared well-tolerated, with gastrointestinal symptoms the most commonly reported intervention-related adverse events, occurring in <5% of participants.

GRADE Evidence Assessment

The certainty of evidence for the primary outcome was assessed as moderate using GRADE methodology. Evidence was initially rated as high due to the inclusion of randomized controlled trials but was downgraded by one level due to some concerns about risk of bias in observational studies and potential indirectness of surrogate biomarker outcomes. The evidence was upgraded by one level due to the large magnitude of effect (OR>2.0) and evidence of a dose-response relationship across intervention intensities.

Factors supporting evidence certainty included consistent direction of effect across studies, biological plausibility of the intervention mechanism, and minimal evidence of publication bias. Limitations included moderate statistical heterogeneity, variable intervention protocols, and limited long-term follow-up data.

Table 3.

GRADE Summary of Findings.

Table 3.

GRADE Summary of Findings.

| Outcome |

Studies |

Participants |

Effect (95% CI) |

Certainty |

Comments |

| Objective Response Rate |

8 |

1,247 |

OR 2.27 (1.44–3.71) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE |

Downgraded for risk of bias, upgraded for large effect |

| Progression-free Survival |

4 |

678 |

HR 0.73 (0.49–1.09) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW |

Limited data, wide confidence intervals |

| Immune-related Adverse Events |

6 |

989 |

RR 0.89 (0.71–1.12) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW |

Inconsistent reporting across studies |

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis provide the first comprehensive quantitative synthesis of evidence regarding dietary interventions targeting gut microbiome modulation in cancer immunotherapy. The primary finding demonstrates that dietary interventions are associated with significantly improved objective response rates to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, with a pooled odds ratio of 2.27 representing a large and clinically meaningful effect size. These results suggest that dietary modifications may serve as accessible, low-risk adjunctive interventions to optimize immunotherapy outcomes.

Interpretation of Findings in Context

The observed effect size is substantial within the context of cancer immunotherapy research. For comparison, biomarker-guided patient selection strategies typically yield odds ratios of 1.5-2.0 for immunotherapy response prediction [

26], while combination immunotherapy approaches often demonstrate similar magnitude improvements over single-agent therapy [

27]. The finding that dietary interventions can achieve comparable effect sizes highlights their potential clinical importance, particularly given their favorable safety profile and low implementation barriers. Although the pooled OR suggests benefit, the 95 % prediction interval (0.89–6.01) crosses the null, so results must be interpreted cautiously

The biological plausibility of our findings is supported by extensive preclinical and mechanistic research. Dietary fiber promotes the production of short-chain fatty acids, particularly butyrate, which enhances CD8+ T-cell function and trafficking to tumor sites [

28]. High-fiber diets also support beneficial bacterial taxa such as

Bifidobacterium and

Akkermansia, which have been consistently associated with improved immunotherapy outcomes across independent patient cohorts [

29,

30]. Mediterranean diet patterns provide anti-inflammatory polyphenols and omega-3 fatty acids that can modulate systemic immune function and reduce immunosuppressive cytokine production [

31].

The consistency of effects across different cancer types is particularly noteworthy, suggesting that the gut-microbiome-immunity axis may represent a universal mechanism influencing immunotherapy efficacy rather than tumor-specific pathway. This finding supports the potential for broad clinical implementation across oncology practice, though tumor-specific optimization strategies may still be warranted.

Clinical Implications and Practice Integration

These findings have immediate implications for clinical practice in cancer immunotherapy. The large effect size (OR 2.27) combined with the minimal risk profile of dietary interventions provides a compelling risk-benefit ratio for clinical implementation. These findings provide a rationale for oncologists to discuss high-fiber dietary patterns with patients, while clarifying that confirmatory trials are still needed.

However, several important considerations must guide clinical implementation. First, dietary interventions should complement rather than replace standard immunotherapy protocols, as no studies evaluated dietary interventions as monotherapy. Second, optimal timing of dietary interventions relative to immunotherapy initiation requires further investigation, though available evidence suggests that concurrent implementation may be most beneficial due to the dynamic nature of microbiome-immunity interactions.

Third, patient selection considerations may be relevant, as baseline nutritional status, antibiotic exposure history, and intrinsic microbiome composition likely influence intervention effectiveness. Future clinical implementation should consider developing personalized approaches based on individual patient characteristics and baseline microbiome profiles.

Clinical implications: Although pooled results are encouraging, evidence is not yet sufficient to support routine implementation of standardized dietary prescriptions in oncology practice. These findings support the rationale for well-designed randomized trials and structured pilot programs to evaluate efficacy, feasibility, adherence, and safety before broader clinical adoption.

Mechanistic Insights and Future Directions

While our review focused on clinical outcomes, the included studies provide insights into potential mechanistic pathways mediating diet-microbiome-immunity interactions. Several studies reported increased abundance of beneficial bacterial taxa, particularly

Akkermansia muciniphila and

Bifidobacterium longum, following dietary interventions. These taxa produce metabolites such as butyrate and other short-chain fatty acids that can enhance T-cell function and reduce regulatory T-cell populations in the tumor microenvironment [

32].

The timing and durability of microbiome changes following dietary interventions varied across studies, with some demonstrating rapid changes within 2-4 weeks and others requiring 8-12 weeks for maximal effect. This temporal variability suggests that intervention duration and maintenance strategies may be important factors for optimization. Future research should investigate dose-response relationships for specific dietary components and establish minimum effective intervention durations.

The role of the gut-liver axis in mediating dietary effects on systemic immunity also warrants investigation, as hepatic metabolism of microbiome-derived metabolites may influence immune cell function and trafficking. Additionally, the potential for dietary interventions to modulate immune-related adverse events represents an important area for future study, as current evidence was limited by inconsistent reporting across studies.

Limitations and Cautionary Considerations

A primary limitation of this review is that all study screening, data extraction, and risk-of-bias assessments were performed by a single reviewer, which increases the potential for error and subjective bias. Several important limitations must be acknowledged when interpreting these findings. First, the observational design of most included studies (5 of 8) fundamentally limits causal inference. While the temporal sequence of dietary intervention followed by improved immunotherapy response supports biological plausibility, unmeasured confounding variables cannot be excluded as alternative explanations for the observed associations. Factors such as baseline nutritional status, socioeconomic status, concurrent medications, genetic variants affecting microbiome composition, and other lifestyle factors may contribute to the observed effects.

Second, substantial heterogeneity existed in dietary intervention protocols across studies, making it challenging to establish optimal implementation strategies. The duration of interventions ranged from 2 weeks to 6 months, fiber intake targets varied from 25-40g daily, and adherence monitoring methods differed substantially. This heterogeneity limits the precision of clinical recommendations and emphasizes the need for standardization in future research.

Third, microbiome assessment methods varied significantly across studies, including differences in sequencing platforms, primer sets, bioinformatics pipelines, and taxonomic classification approaches. These methodological variations may have introduced systematic bias and limited the ability to identify consistent microbiome signatures associated with treatment response.

Fourth, long-term outcomes data were limited, with most studies focusing on short term response rates (8-12 weeks post-immunotherapy initiation). Only 3 studies provided progression-free survival data beyond 6 months, and overall survival data were available for only 2 studies. This temporal limitation restricts conclusions about sustained clinical benefits and long-term safety of dietary interventions.

Fifth, the study populations were predominantly from high-income countries with potential genetic, environmental, and dietary baseline differences that may limit generalizability to diverse global populations. Additionally, all studies were conducted in academic medical centers, potentially limiting applicability to community practice settings where nutritional resources may be more limited.

Variable adherence and lack of per-protocol data may inflate the true effect.

Furthermore, planned subgroup analyses could not be conducted, which prevents a deeper exploration of the sources of heterogeneity.

Strengths and Quality of Evidence

Despite these limitations, several methodological strengths support confidence in our findings. The prospective registration of our review protocol in PROSPERO minimized selective reporting bias and ensured transparent methodology. Our comprehensive search strategy across multiple databases and grey literature sources reduced the likelihood of missing relevant studies.

The quality of included primary studies was generally high, with 5 of 8 studies demonstrating low risk of bias using appropriate assessment tools. All studies included quantitative microbiome assessment, ensuring biological plausibility of the intervention mechanism. The consistency of effect direction across studies and robust sensitivity analyses support the reliability of the pooled estimate.

The GRADE assessment of moderate certainty evidence reflects appropriate acknowledgment of study limitations while recognizing the large magnitude of effect and biological coherence of findings. This evidence level supports consideration of clinical implementation while emphasizing the need for confirmatory randomized controlled trials.

Research Priorities and Future Directions

Several critical research priorities emerge from this systematic review. First, large scale, multi-center randomized controlled trials are urgently needed to establish causality and optimize intervention protocols. These studies should include standardized dietary interventions, comprehensive microbiome profiling, and long-term survival endpoints, and biomarker-guided patient selection strategies.

Second, mechanistic studies investigating the temporal dynamics of diet microbiome-immunity interactions are needed to inform optimal intervention timing and duration. These studies should include serial microbiome sampling, immune function assessments, and metabolomic profiling to elucidate causal pathways.

Third, development of clinically feasible biomarkers for predicting responsiveness to dietary interventions would enable personalized implementation strategies. Potential biomarkers include baseline microbiome composition, dietary biomarkers, genetic variants affecting microbiome-host interactions, and immune function parameters.

Fourth, health disparities research must address generalizability by including diverse populations and investigating the impact of socioeconomic factors, food access, cultural dietary preferences, and healthcare system variations on intervention effectiveness.

Fifth, cost-effectiveness analyses and health economic modeling are needed to inform healthcare policy decisions and resource allocation. These analyses should consider both direct intervention costs and potential savings from improved immunotherapy response rates.

Finally, implementation science research is needed to develop effective strategies for integrating dietary interventions into routine oncology care, including healthcare provider training programs, patient education resources, and quality improvement initiatives.