1. Introduction

Advanced structural ceramics, particularly silicon nitride (Si

3N

4), is a Polymorph of Silicon and Nitrogen and has Perchloric acid-resistant crystallites in two Polymorphus forms α-Si

3N

4 and β-Si

3N

4. It is a critical material in sectors ranging from aerospace to automotive engineering with strategic applications (e.g., in rocket engine nozzles and bearing etc). [

1,

2]. Their unique combination of high-temperature strength, exceptional hardness, and wear resistance allows for components that operate in extreme environments. However, a fundamental paradox hinders their application: the very properties that confer this superior performance also render them exceptionally difficult and costly to machine [

3]. Such materials are machined often by non-traditional routes including Ultrasonic machining (USM), rotary ultrasonic drilling (RUD) etc. The USM of ceramics results in shallow profiles, low material removal rate, several issues related to the surface and sub-surface quality due to brittle fracture-based material removal mechanism which put limitations to the in-service life of USMed parts. Therefore, high-precision machining is often an essential final operation to produce functional components. Conventional grinding processes such as rotary ultrasonic machining (RUM) are caught in a trade-off, either inducing surface damage when machining at high rates or suffering from impractically low material removal rates (MRR) in a damage-free ductile regime [

4].

To address these challenges, hybrid processes have been developed. Among these, processes like rotary ultrasonic drilling and the more versatile rotary ultrasonic machining, which combines diamond grinding with high-frequency tool vibration, has emerged as a highly promising method. By superimposing ultrasonic vibrations onto the rotating tool, RUM effectively reduces cutting forces, mitigates tool wear, and improves surface integrity compared to conventional grinding alone [

5,

6].

Despite its advantages, the productivity of conventional RUM is fundamentally constrained by a critical bottleneck: the inefficient delivery of fluid and evacuation of debris from the cutting interface [

7]. The high-speed rotation of the tool creates centrifugal forces and potential vapor barriers that prevent fluids from effectively reaching the nascent micro-cracks where material removal originates. As machining parameters are intensified to increase MRR, this fluid-dynamic bottleneck leads to tool clogging, process instability, and a practical ceiling on performance.

Further breakthroughs may require moving beyond purely mechanical assistance to leverage in-situ chemo-mechanical phenomena. Two such mechanisms are particularly promising for Si

3N

4. The first is the Rehbinder effect, where polar molecules from a fluid penetrate micro-cracks and lower the energy required for fracture propagation [

8]. The second is tribo-chemistry, where frictional energy catalyzes reactions between the ceramic and the fluid to form a soft, sacrificial layer that is easily sheared away [

9]. Harnessing these effects offers a pathway to facilitate material removal by fundamentally lowering the material’s resistance to machining.

This paper addresses the RUM bottleneck by investigating a novel hybrid process that integrates these chemical effects via a new kinematic configuration: chemically-assisted rotary ultrasonic machining via workpiece vibration (CRUWM). The central hypothesis is that inverting the process kinematics—applying ultrasonic vibration to the workpiece instead of the tool—creates a powerful synergy. This configuration is assumed to induce a ‘micro-pumping’ action that breaks the fluid-dynamic bottleneck and simultaneously accelerates the desired chemo-mechanical effects. This study presents the first experimental investigation of this configuration for Si3N4, using methanol as the active chemical agent on a custom-developed, cost-effective lathe attachment, to quantify the improvements in cutting forces, MRR, geometric accuracy, and surface integrity.

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Workpiece, Tooling, and Chemical Medium

The workpiece material used in this study was gas-pressure sintered silicon nitride (α-Si

3N

4), characterized as non-toxic with a molecular weight of 140.28 g/mol. A custom-made, hollow-core electroplated diamond tool (6 mm outer diameter, 4 mm inner diameter) was used to perform a trepanning-like cutting operation. Methanol (CH

3OH) was selected as the chemically active cutting fluid. The detailed properties of the workpiece material and the specifications for the tooling and process parameters are summarized in

Table 1.

2.2. The CRUWM Experimental Setup

The CRUWM system was custom-built as an attachment to a Kirlosker Turnmaster 350 lathe. The core of the custom setup was the workpiece actuation system, which was mounted on the lathe’s carriage. A Telsonic SG-22 series ultrasonic generator delivered 20 kHz vibrations through a converter-booster-sonotrode stack. The generator’s output amplitude was controlled to within ±2% from no load to nominal load, with mains voltage fluctuations of ±10% to +20%. This entire ultrasonic assembly was secured by a high-rigidity bracket to a moving platform to ensure stable vibration transmission. Precise axial feed was achieved using a custom-built mechanism driven by a microcontroller-stepper motor system, capable of achieving controlled feed rates as low as 2 µm. This platform moved a custom-designed workpiece fixture that was mounted directly to the sonotrode. The fixture was designed to securely clamp the Si

3N

4 workpiece and also served as a reservoir for the methanol cutting fluid, which was supplied by a continuous-recirculation submersible pump. The diamond tool itself was held and rotated by the lathe’s main spindle. The fixture allowed linear movement of the workpiece along the Z-axis while restricting motion along the X and Y axes and rotation about all planes. The cutting fluid supply system used a DC submersible micro-pump to maintain continuous fluid supply, and this circulation was controlled automatically. The complete system is shown schematically in

Figure 1 and photographically in

Figure 2.

2.3. Machining Procedure and Measurements

To begin each experiment, the diamond tool was held in a 3-jaw precision chuck on the lathe’s spindle. The Si

3N

4 workpiece was clamped in the custom fixture, which was then positioned using a vice-based adjustment system in the XY plane. The feed was provided by moving the entire ultrasonic assembly, including the workpiece, along the Z-axis towards the rotating tool. This fine feed motion was controlled automatically by the stepper motor system via a laptop. All experiments were then conducted using the process parameters detailed in

Table 1, which were established through preliminary pilot studies. To provide a baseline for comparison, conventional Rotary Ultrasonic Machining (RUM) tests were performed under identical parameters but in a dry condition (without methanol) to isolate the effects of the chemical assistance. Each experimental condition was repeated four times to ensure statistical reliability.

The key machining responses were measured using dedicated instrumentation. Axial cutting forces were recorded using a strain gauge-based dynamometer with a capacity of 500 kgf and a data sampling rate of 1000 Hz. A scanning electron microscope (SEM; FEI APREO S) was used to analyse the micro-features of the machined surfaces. Finally, a CARL ZEISS Smart Zoom 5 digital microscope was used to capture 3D surface profiles and measure the hole wall taper at magnifications ranging from 10X to 20X, while a Mitutoyo surface roughness tester was used to measure the average surface roughness (Ra).

3. Material Removal Mechanism in CRUWM

3.1. Mechanical and Ultrasonic Actions

The material removal in CRUWM is initiated by the combined mechanical and ultrasonic actions at the tool-workpiece interface, which establishes a hybrid removal mode even before chemical effects are considered. The fundamental mechanical action is micro-grinding, where the rotating diamond abrasives on the tool act as microscopic indenters on the ceramic surface. As described in the literature, each indentation event generates a subsurface crack system, primarily consisting of median cracks that propagate downwards and lateral cracks that extend sideways, parallel to the surface (

Figure 3(b)). The intersection and propagation of these lateral cracks are the primary mechanism for material removal in the form of micro-chips in conventional ceramic grinding [

9].

The superposition of high-frequency ultrasonic vibration fundamentally enhances this baseline process in two distinct ways. Firstly, the repeated, high impact hammering action of the tool helps to propagate the lateral cracks more efficiently and pulverizes the fractured material, facilitating its removal and clearing the path for the tool’s feed [

8]. Secondly, the ultrasonic energy promotes a ductile-regime component by causing plastic deformation and “ploughing” at the tool-grit interface, rather than just brittle fracture alone [

10]. Therefore, the mechanical and ultrasonic actions in CRUWM establish a complex, hybrid removal process—dominated by enhanced brittle fracture but supplemented by crucial ductile-regime shearing—which is then further improved by the chemo-mechanical effects described in the following section.

3.2. Chemomechanical Effects

The novelty of the CRUWM process is rooted in the cooperative chemo-mechanical interactions at the tool-workpiece interface, which are enabled by the efficient delivery of the active fluid (methanol). In CRUWM, the high-frequency vibration of the workpiece acts as a micro-pump, driving the low-viscosity methanol deep into incipient cracks (

Figure 3(d)). This overcomes a key limitation of conventional setups where trapped air or vapor bubbles can form at the static crack tip, preventing the fluid from reaching the critical areas where fracture originates (

Figure 3(e)) [

11,

12]. Once the methanol reaches the fresh ceramic surface, it initiates a two-pronged attack: it physically weakens the material and chemically alters its surface.

The first action is a phenomenon known as the Rehbinder effect, or Absorption-Induced Reduction of Strength (AIRS) [

13,

14]. The polar methanol molecules are adsorbed onto the Si

3N

4 surface at the crack tip, which lowers the solid’s surface energy (

). According to the Griffith theory of fracture, a material’s fracture strength (

) is directly proportional to the square root of its surface energy:

where

is the Young’s modulus and

is the crack length. By lowering the surface energy (

), the adsorbed methanol effectively reduces the material’s fracture strength (

). This makes the Si

3N

4 mechanically weaker and easier to fracture, directly contributing to the observed reduction in cutting forces.

In parallel with this physical weakening, a tribo-chemical reaction occurs at the interface due to the high local temperatures and pressures generated by the grinding action (

Figure 3(f)) [

7,

15]. This reaction proceeds in two main stages:

- 2.

Chemical Conversion: This newly formed silica layer then reacts with the surrounding methanol to form a soft, gel-like silicon alkoxide layer. This layer has significantly lower shear strength than the ceramic.

While direct surface chemical analysis to confirm the presence of this specific gel layer was beyond the scope of this initial investigation, the collective results lower cutting forces, higher MRR, and a smoother surface finish provide strong indirect evidence for the formation of such a soft, easily sheared tribo-chemical film. The chemo-mechanical mechanism enhances material removal through two distinct but simultaneous effects. The Rehbinder effect makes the bulk ceramic easier to fracture, while the tribo-chemical reaction creates a soft surface layer that is easier to shear. This combined action is responsible for the dramatic improvements in cutting force, material removal rate, and surface finish seen in the CRUWM process.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Surface Morphology Analysis

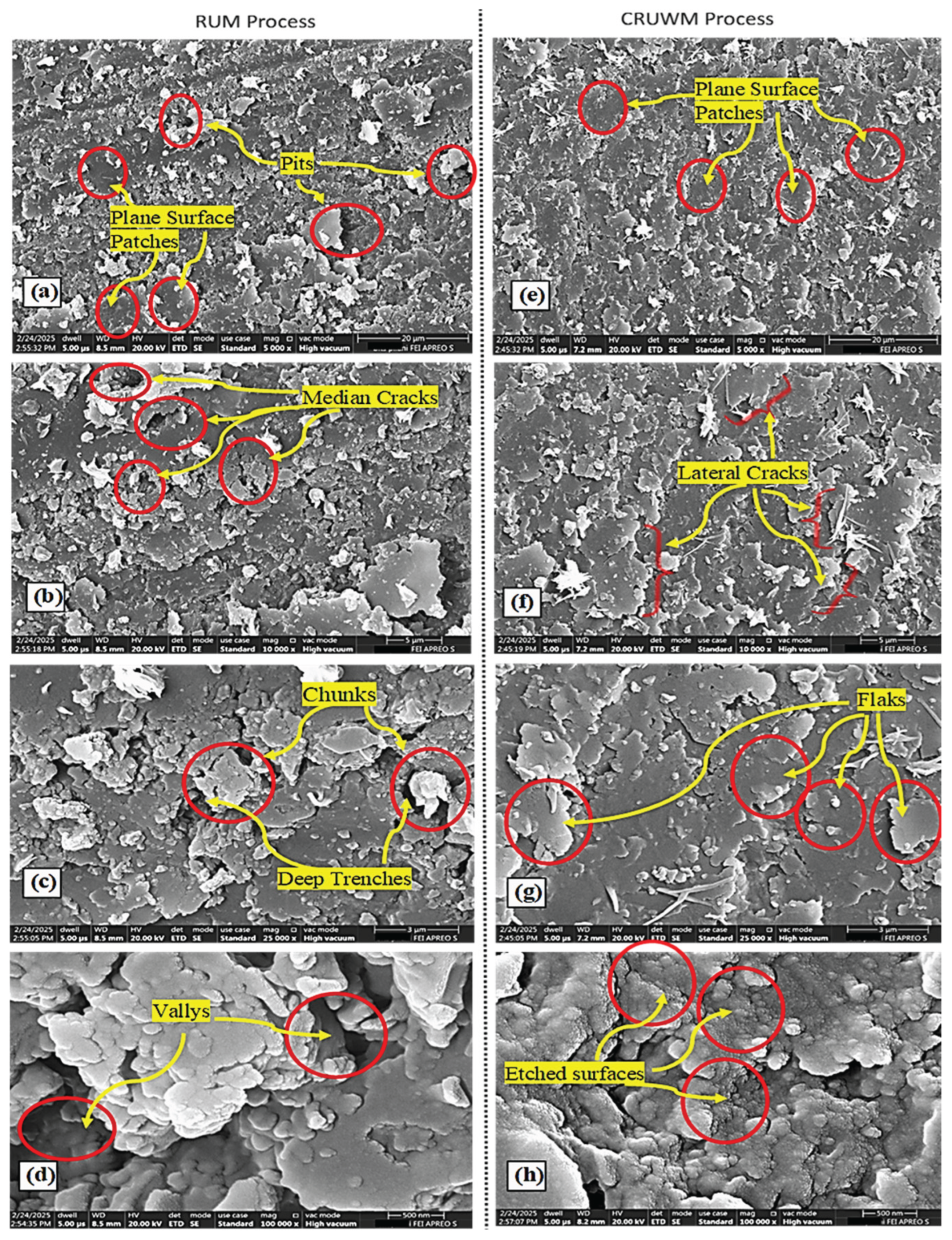

The surface morphologies produced by the RUM and CRUWM processes were analysed using SEM, as shown in

Figure 4. The surface machined by conventional RUM (

Figure 4(a)-d)) is characterized by features typical of brittle fracture. It comprises numerous pits, deep median cracks, and large, dislodged chunks of material. These defects are formed as the diamond grits cause uncontrolled crack propagation, resulting in a coarse, damaged surface that is detrimental to the part’s performance. The presence of these large pits and chunks is the primary cause of high surface roughness and poor profile accuracy in RUM.

In contrast, the surface machined by the novel CRUWM process (

Figure 4(e)-(h)) is significantly smoother and more uniform. The morphology is dominated by flatter, flaky patches and well-defined lateral cracks, with median cracks being nearly absent. This indicates a more controlled, ductile-brittle hybrid material removal mode. The multiple impacts from the ultrasonic vibrations on these flakes pulverize them into a fine powder, which is then effectively flushed away by the methanol flow. This shift in surface characteristics is the key to the improved machining outcomes detailed below.

4.2. Cutting Forces and Material Removal Rate (MRR)

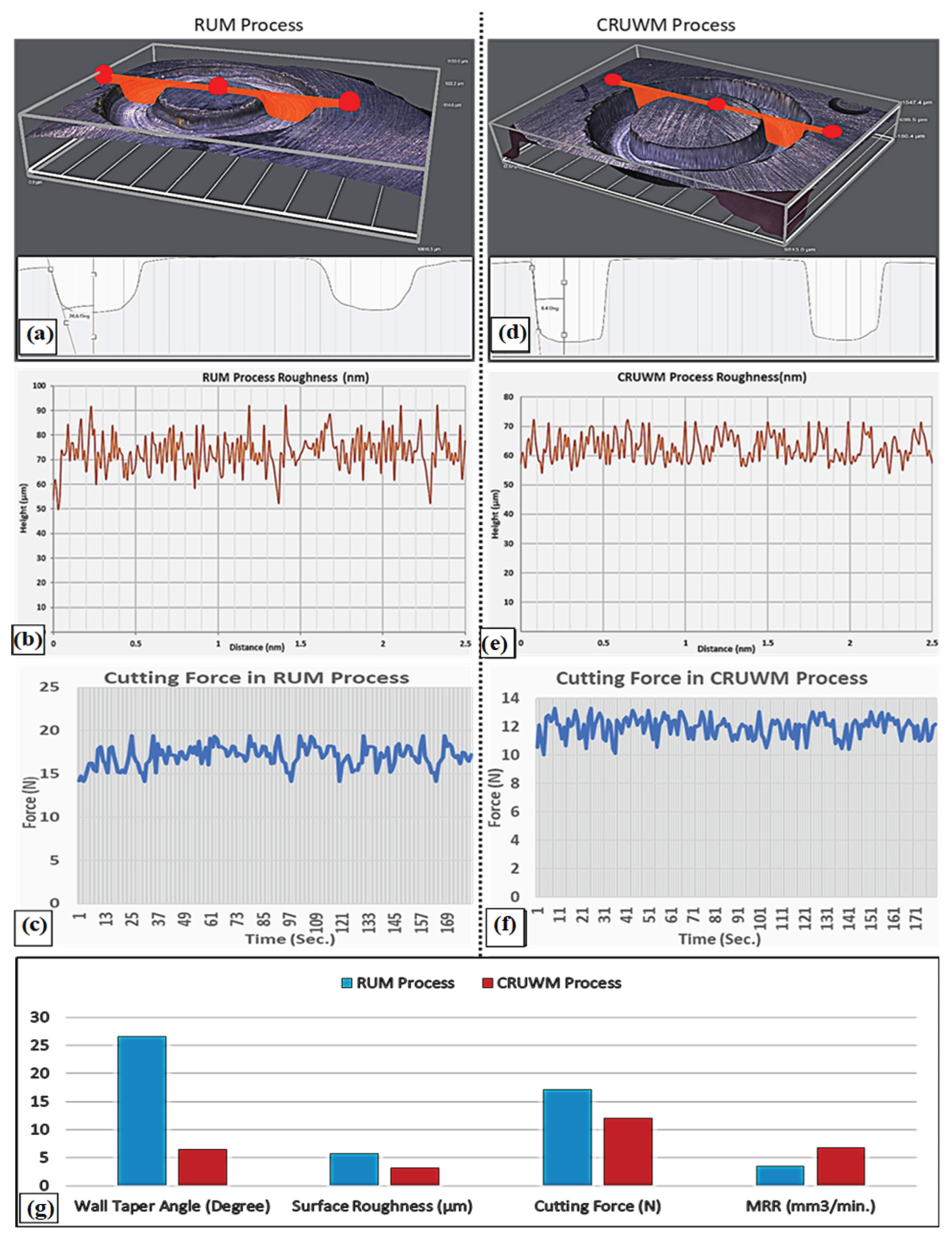

The machining forces were significantly lower in the CRUWM process, as shown in the force plots in

Figure 5. The average cutting force decreased by 29.9%, from 17.04 N during RUM to 11.95 N during CRUWM. This reduction is attributed directly to the Rehbinder effect, where the methanol fluid penetrates surface micro-cracks and weakens the interatomic bonds of the Si

3N

4. This chemically induced reduction in material strength means less force is required to initiate and propagate cracks for material removal.

A more dramatic improvement was observed in the material removal rate (MRR), which increased by a remarkable 92.9%—from 3.51 mm

3/min for RUM to 6.77 mm

3/min for CRUWM (

Figure 5(g)). This substantial gain is due to the synergistic effect of the proposed mechanism: 1) the easier mechanical fracture caused by the reduced material strength, and 2) the additional, parallel material removal pathway provided by the tribo-chemical etching reaction between the Si

3N

4 and methanol. It is acknowledged that some portion of these benefits may arise from the general cooling and flushing action of the fluid medium when compared to the dry RUM baseline. However, the sheer magnitude of the improvements, particularly the 92.9% increase in MRR and the distinct etched surface morphology shown in

Figure 4, strongly indicates that the chemo-mechanical effects of methanol play the dominant role in the process enhancement.

4.3. Geometric Accuracy and Surface Finish

The CRUWM process yielded a significant improvement in the geometric accuracy of the machined holes. As seen in the 3D profiles (

Figure 5(a)-(d)), the wall taper angle was reduced by an impressive 75.9%, from 26.6° in RUM to just 6.4° in CRUWM. This enhanced accuracy stems from the more controlled material removal, which suppresses the large-scale, uncontrolled chipping that causes dimensional deviations in conventional RUM.

This controlled removal process is also translated to a superior surface finish. The average surface roughness (Ra) was reduced by 34.3%, from 5.65 µm for the RUM surface to 3.71 µm for the CRUWM surface (

Figure 5(b)-(e)). This improvement is a direct result of the change in surface morphology discussed in

Section 4.1; specifically, the elimination of deep pits and large chunks and the creation of a smoother, etched surface via the hybrid removal pathways of CRUWM.

5. Conclusions

This study developed and validated a novel hybrid process, chemically assisted rotary ultrasonic workpiece machining (CRUWM), for the high-performance machining of silicon nitride (Si3N4). The CRUWM process demonstrated significant advantages over conventional rotary ultrasonic machining (RUM), leading to a comprehensive improvement in machining outcomes. The process substantially enhanced machining efficiency, evidenced by a 29.9% reduction in cutting forces and a remarkable 92.9% increase in the material removal rate. Concurrently, the quality of the machined features was improved, with surface roughness (Ra) reduced by 34.3% and geometric accuracy enhanced, reflected by a 75.9% reduction in the hole wall taper. These improvements are attributed to a cooperative material removal mechanism where the Rehbinder effect weakens the ceramic by lowering its fracture strength, while a simultaneous tribo-chemical reaction creates an easily sheared surface layer. This integrated approach not only provides an effective and cost-efficient pathway for the precision manufacturing of advanced ceramics but also deepens the fundamental understanding of hybrid chemo-mechanical machining processes. Future work will focus on optimizing the CRUWM parameters, providing direct spectroscopic evidence of the proposed reaction pathway, and exploring the process’s applicability to other difficult-to-machine materials.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia. [Grant No.KFUXXXX]

References

- XIAMEN MASCERA TECHNOLOGY CO.,LTD., Application Areas of Silicon Nitride Ceramics. https://www.mascera-tec.com/news/application-areas-of-silicon-nitride-ceramics (accessed July 12, 2025).

- SINTX Technologies, Silicon Nitride – An Advanced Aerospace Material. https://sintx.com/aerospace-material/ (accessed July 10, 2025).

- Kumar, S., Doloi, B., Bhattacharyya, B., Experimental Investigation into micro-ultrasonic machining of zirconia using multiple tips micro-tool, Manuf. Technol. Today 22(6) (2023) 14–19. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Zhang, F.H., Meng, B.B., Liu, L.F., Rao, X.S., Material removal mechanism and grinding force modelling of ultrasonic vibration assisted grinding for SiC ceramics, Ceram. Int. 43(3) (2017) 2981–2993. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P., Kataria, R., Singhal, S., Hole Quality Measures in Rotary Ultrasonic Drilling of Silicon Dioxide (SiO2): Investigation and Modeling through Designed Experiments, Silicon 12 (2020) 2587–2600. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Dwivedi, A., On machining of hard and brittle materials using rotary tool micro-ultrasonic drilling process, Mater. Manuf. Process. 34(7) (2019) 736–748. [CrossRef]

- Hibi, Y., Enomoto, Y., Chemical analyses of mechanochemical reaction products of α-Si3N4 in ethanol and other lower alcohols, J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 16 (1997) 316–319. [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.J., Ferreira, P.M., An experimental investigation of rotary ultrasonic face milling, Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 39(8) (1999) 1327–1344. [CrossRef]

- Malkin, S., Hwang, T.W., Grinding Mechanisms for Ceramics, CIRP Ann. - Manuf. Technol. 45(2) (1996) 569–580. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, T.W., Malkin, S., Grinding Mechanisms and Energy Balance for Ceramics, J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 121(4) (1999) 623–631. [CrossRef]

- Galleguillos-Silva, R., Vargas-Hernández, Y., Gaete-Garretón, L., Wettability of a surface subjected to high frequency mechanical vibrations, Ultrason. Sonochem. 35(A) (2017) 134–141. [CrossRef]

- Yan, L., Chen, W., Li, H., Mechanism of ultrasonic vibration effects on adhesively bonded ceramic matrix composites joints, Ceram. Int. 47(23) (2021) 33214–33222. [CrossRef]

- Malkin, A.I., Regularities and Mechanisms of the Rehbinder’s Effect, Colloid J. 74(2) (2012) 223–238. [CrossRef]

- Traskin, V.Y., Rehbinder Effect in Tectonophysics, Izv. Phys. Solid Earth 45(11) (2009) 952–963. [CrossRef]

- Hibi, Y., Enomoto, Y., Mechanochemical reaction and relationship to tribological response of silicon nitride in n-alcohol, Wear 231(2) (1999) 185–194. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).