1. Introduction

Giacomo Ciamician played a significant role in the development of organic chemistry between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He certainly played a crucial role in the development of photochemistry applications when used to discover the behavior of organic compounds [

1].

Ciamician was an innovator, open to new ideas, but at times he also had closed attitudes that were difficult to understand. Regarding the tetrahedral structure of carbon proposed by van’t Hoff, he said: “I do not wish to examine further here whether this conception (...) should be considered as durable or as a transitional form. The history of organic chemistry seems to speak strongly in favor of the latter possibility” [

2].

Ironically, Ciamician’s name is linked to the first photochemical reaction characterized by high stereoselectivity, due to the presence of a chiral tetrahedral carbon atom on the substrate. The presence of a chiral carbon atom, in fact, since the reaction is intramolecular, leads to the formation of new bonds that can only form on one side of the molecule, thus stereoselectively.

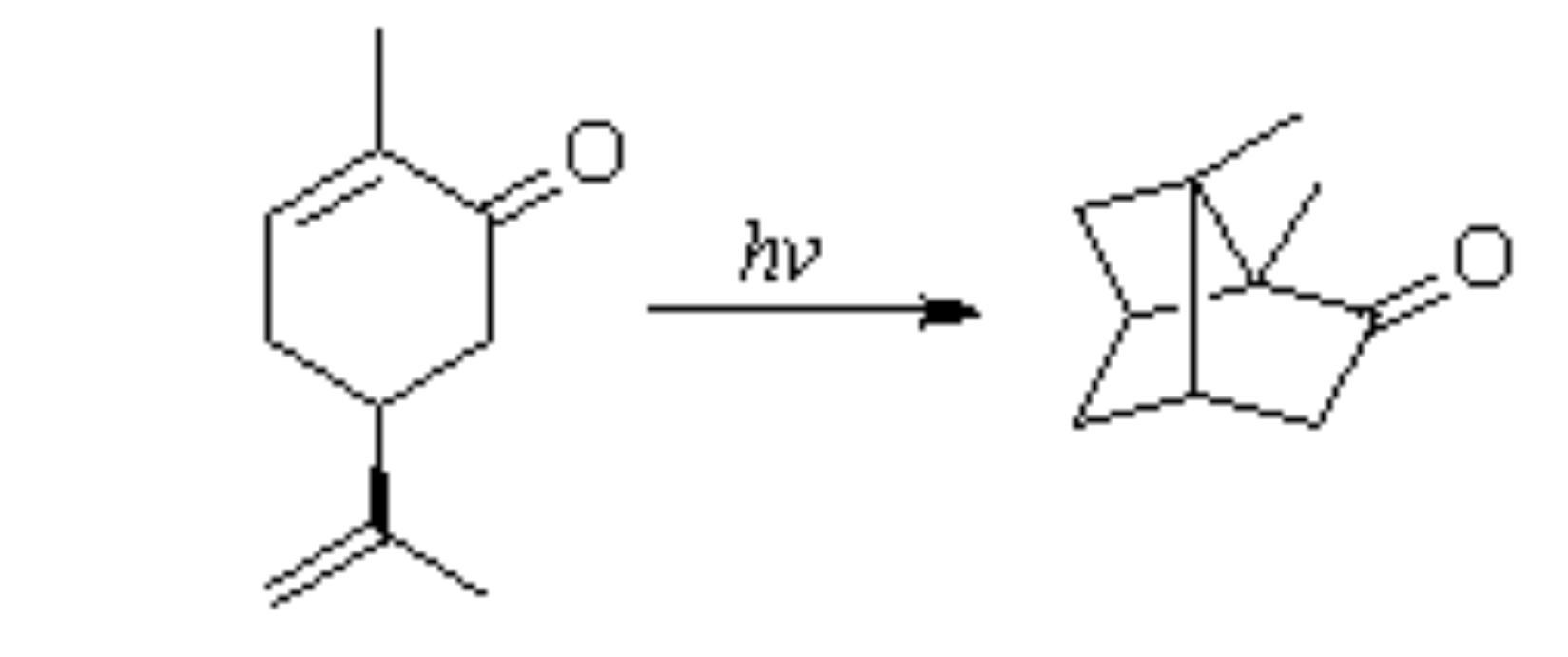

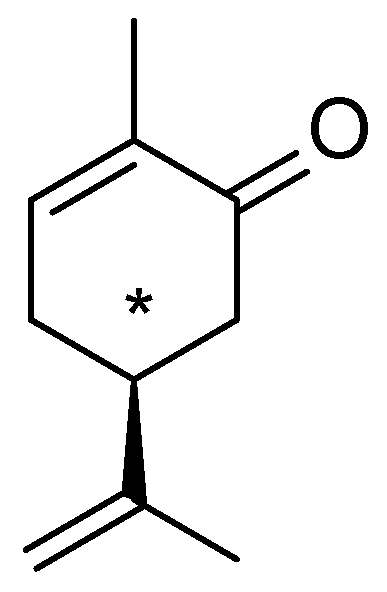

In a 1908 article, Ciamician described the behavior of carvone (a terpene,

Figure 1) when irradiated in a hydroalcoholic solution with sunlight in summer-autumn [

3]. This compound has an asymmetric carbon atom (indicated by the asterisk) bearing four different substituents. Irradiation under the conditions described led to the formation of a mixture of products. The most significant was a resin, likely resulting from the polymerization of the substrate. An oily residue remained, consisting of unreacted carvone and a different solid substance. This compound, resulting from the photochemical reaction, was separated by steam distillation. The compound is solid and melts at 100 °C. Ciamician obtained this product in a very low yield (6%), but this did not prevent him from studying it. The reaction product turned out to be a carbonyl compound since it reacts with hydroxylamine to yield the corresponding oxime and with semicarbazide to yield the corresponding semicarbazone.

Elemental analysis of these derivatives was consistent with a molecular formula of C10H14O, i.e., an isomer of the substrate.

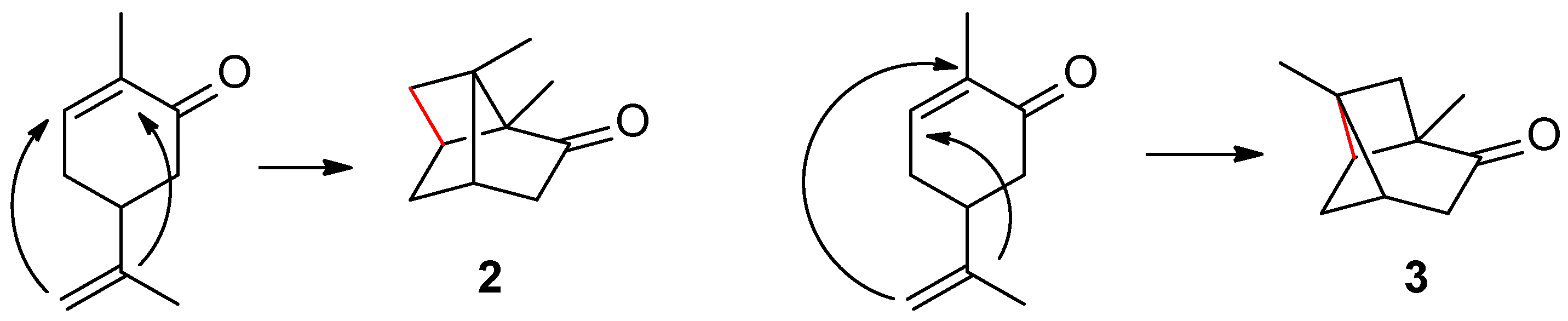

Based on these data, and considering that the structure of carvone is non-planar (

Figure 2), it was possible to hypothesize the interaction between the carbons belonging to the two double bonds to form a four-membered ring.

The result is the assignment of structure

2 to the reaction product (

Scheme 1). This assignment was not based on a proper demonstration of the structure. It was more the result of logical reasoning (the analogy of the observed behavior with the dimerization of cinnamic acids) than an assignment made using the usual criteria for demolishing the structure at the time.

A few years later, the work was resumed by Emilio Sernagiotto [

4]. This researcher, in Bologna since 1913, published two articles on the same reaction [

5,

6]. Sernagiotto repeated the reaction and found a 12.3% yield of the isomerization product. Compared to Ciamician’s original work, Sernagiotto performed a series of tests aimed at identifying the structure. The compound does not absorb hydrogen in the presence of palladium on carbon, therefore it does not have double bonds; it is a saturated compound. It is oxidized with permanganate in a hot, basic environment to yield two products: the first was a dicarboxylic acid. This result was consistent with a structure analogous to that of camphor, where the carbonyl group and the adjacent carbon have been oxidized to a carboxylic acid. The second was a keto acid derived from the first by further oxidation and decarboxylation (elementary analysis shows the presence of one less carbon atom).

The product of the photochemical reaction was then treated with sulfuric acid in an alcoholic solution, under conditions in which, according to the author, “the opening of the secondary nuclei in polycyclic ketones occurs (...) and determines the formation of double bonds in these.” The result is a compound that was still an isomer of carvone, which retained the ketone function and had a double bond (which was reduced by reaction with hydrogen). The physical characteristics of the compound did not allow its identification.

The physical characteristics of the compound did not allow for its identification. Treatment of the compound with permanganate leads to the formation of levulinic acid CH3COCH2CH2CO2H.

Reduction of the ketone function with sodium yielded the corresponding alcohol. If the product of the photochemical reaction was treated with phosphorus pentachloride, 2-chlorocimol was obtained. This product indicates that the isopropyl group present in carvone was retained in the reaction product adding a piece to the structure.

These are the experimental data. What conclusions did Sernagiotto draw from these results? First, the author of the article considered that in addition to the reaction product

2, claimed by Ciamician, the formation of another product (

3) was also possible, resulting from the coupling of the two double bonds in reverse order (

Scheme 2).

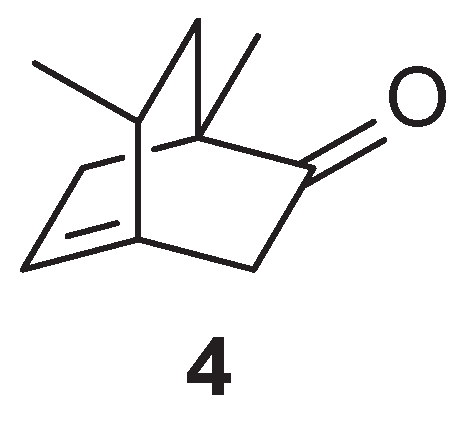

Sernagiotto was unable to identify the isomerization product in an acidic environment deriving from

2 or

3, however he hypothesized that in both cases the bond indicated in red in

Scheme 2 must be broken. This assumption, however, was completely arbitrary. Since the oxidation of this last isomerization product yielded levulinic acid, Sernagiotto concluded that the isomerization product of

3, which he identifies in a completely arbitrary manner as compound

4 (

Figure 3), was better able to yield the five-carbon sequence of levulinic acid upon oxidation.

In conclusion, for Sernagiotto, the product of the photochemical reaction is 3, and not 2, as claimed by Ciamician. As we have tried to clarify, however, these assertions were not based on certain experimental indications, but on hypotheses (the breaking of a certain bond instead of another) that had not been proven.

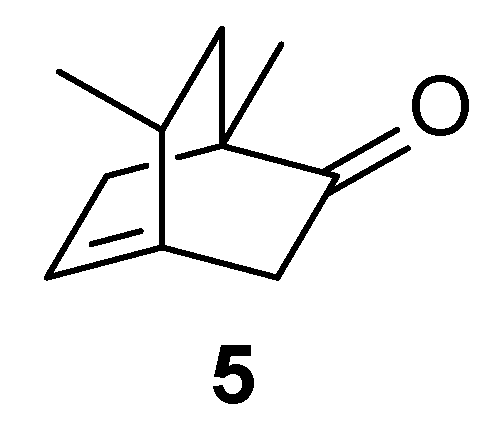

The photochemical reaction of carvone was then repeated by Büchi in 1957 [

7]. Büchi repeated the reaction and obtained the isomerization product with a yield of 9.4%.

He also realized, however, that the reaction is stereospecific. Starting from a chiral compound (α

D 55.6 (c 3.07 in ethanol), he found that the product, in which additional asymmetric carbon atoms are generated, retained optical activity (α

D 86.9 (c 1.02 in ethanol)). He also attempted to identify the product of the subsequent isomerization in an acidic environment described by Sernagiotto, and based on the infrared spectrum alone, which would suggest the presence of exocyclic methylene, he assigns, again in a highly arbitrary manner, structure

5 to the isomerization product, a product that could be formed from

2 (

Scheme 3).

The structure of compound 5 is not demonstrated. The rest of the article concerns the oxidation of the product of the photochemical reaction with perbenzoic acid. This reaction yields two products. The main one is described, but the structure is not demonstrated in any way; the secondary one, which appears to derive from an uncommon isomerization process, is recognized by demolition until a recognizable product is obtained.

Finally, one of the products resulting from oxidation with perbenzoic acid is treated with sulfuric acid to yield an aromatic compound. It remains rather unclear to me how a tricyclic structure can be established starting from an aromatic demolition product.

In conclusion, this publication, like previous ones on the subject, is unable to conclusively demonstrate the structure of the photochemical isomerization product. It was necessary to wait until 1965 to put an end to this matter [

8]. First, the reaction was repeated, and, operating at lower substrate concentrations, a 46% yield was achieved. The structure

2 of the photochemical reaction product was then confirmed by the proton NMR spectrum.

A long history, that of carvone isomerization where the isomerization mechanism was not investigated. Büchi proposed a radical mechanism based on the formation of the triplet excited state of carvone [

7]. However, until now, theoretical calculations were not performed in order test the Büchi hypothesis.

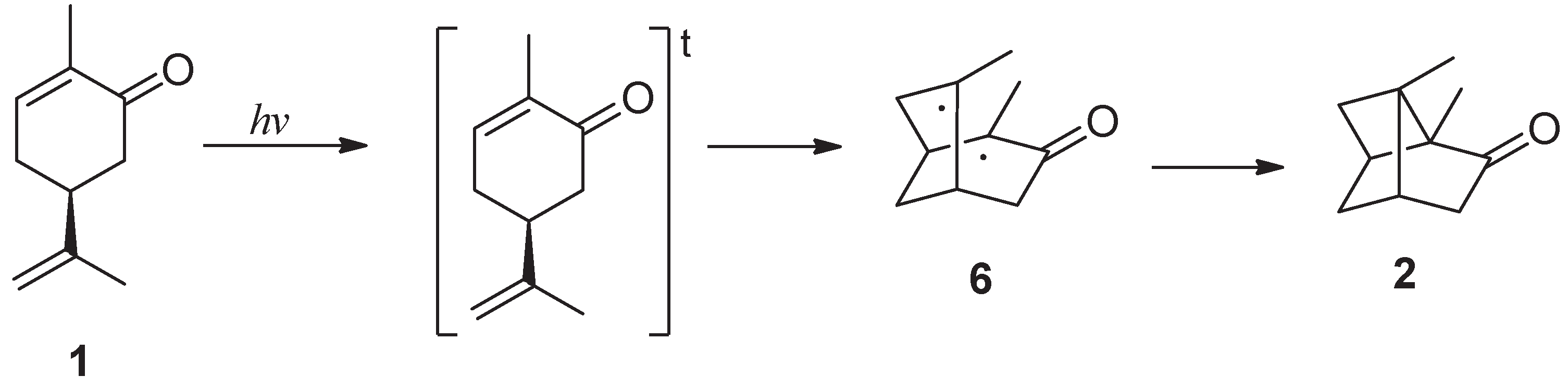

3. Results and Discussion

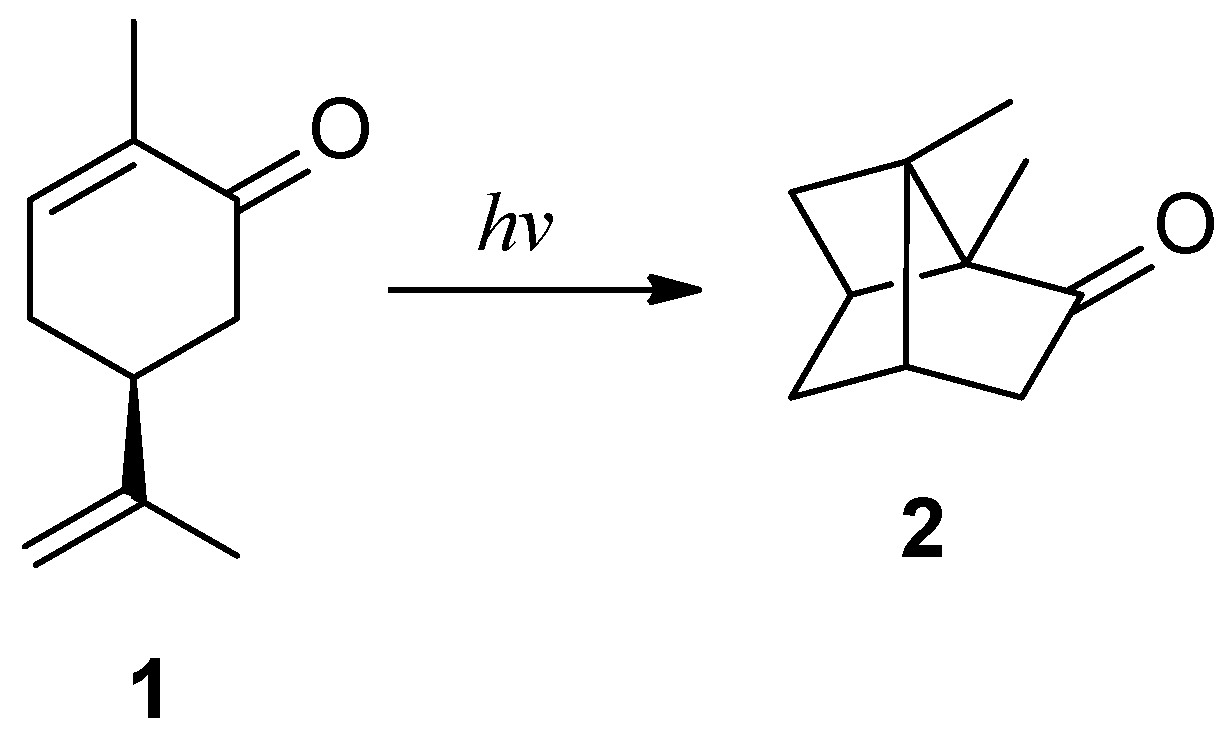

Büchi suggested for carvone photoisomerization a mechanism described in the

Scheme 4 where the excited triplet state gave a radical coupling giving the biradical intermediate

6 that cyclized to give the cyclobutene ring in

2 [

7].

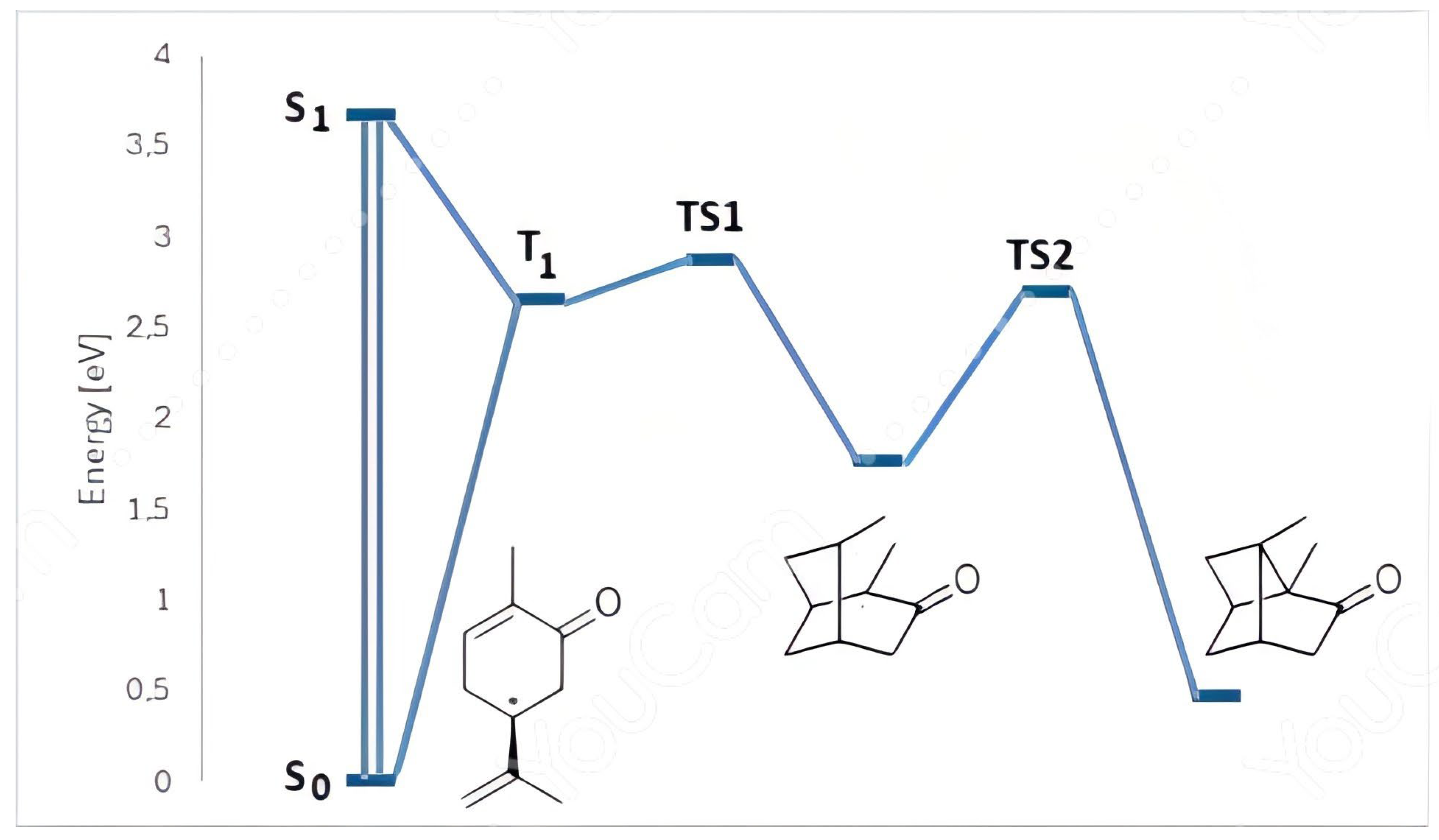

Calculations have been performed in order to test this hypothesis and to verify if other possible mechanisms (i.e. concerted [2+2]-cycloadditon) were present. DFT calculations have been performed at B3LYP/6-311G+(d,p) level of theory. Optimized structure for carvone in its ground state was used in TD-DFT calculation of the first excited singlet state. Carvone showed an absorption at λ 339 nm, corresponding to a S

1 state at 3.66 eV (

Figure 4). The excited singlet state can be converted into the corresponding triplet state at 2.65 eV (

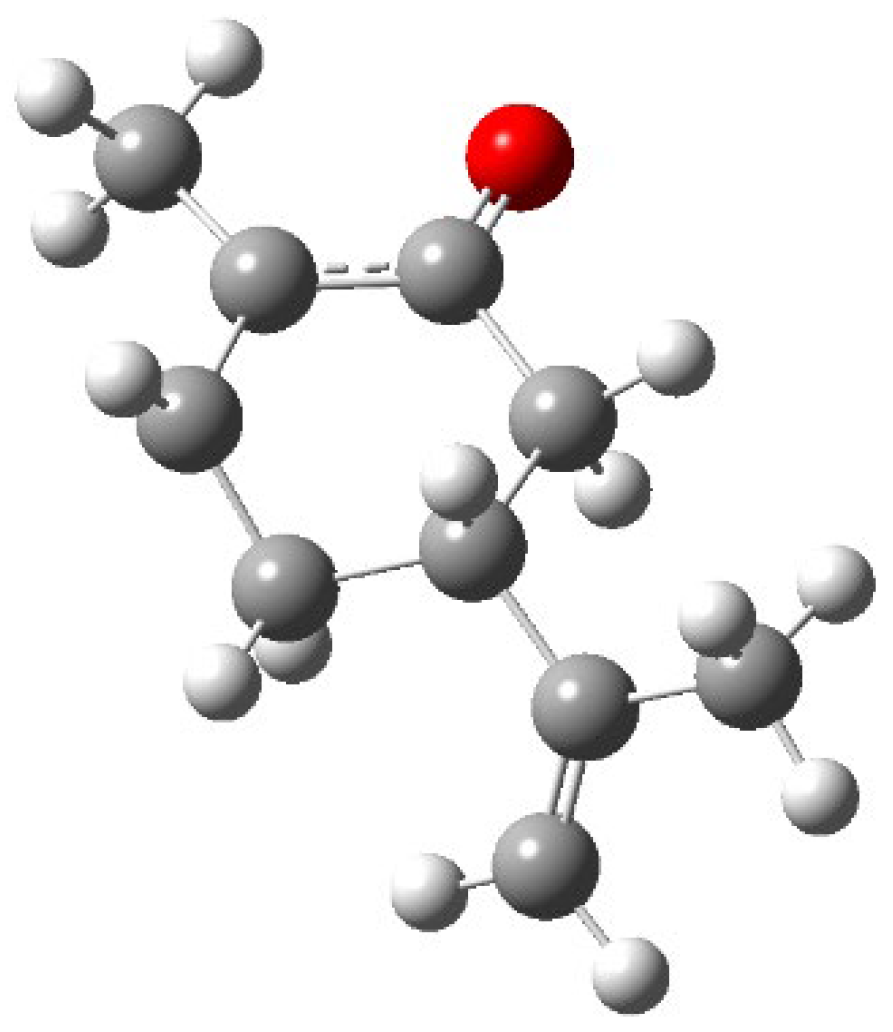

Figure 4).

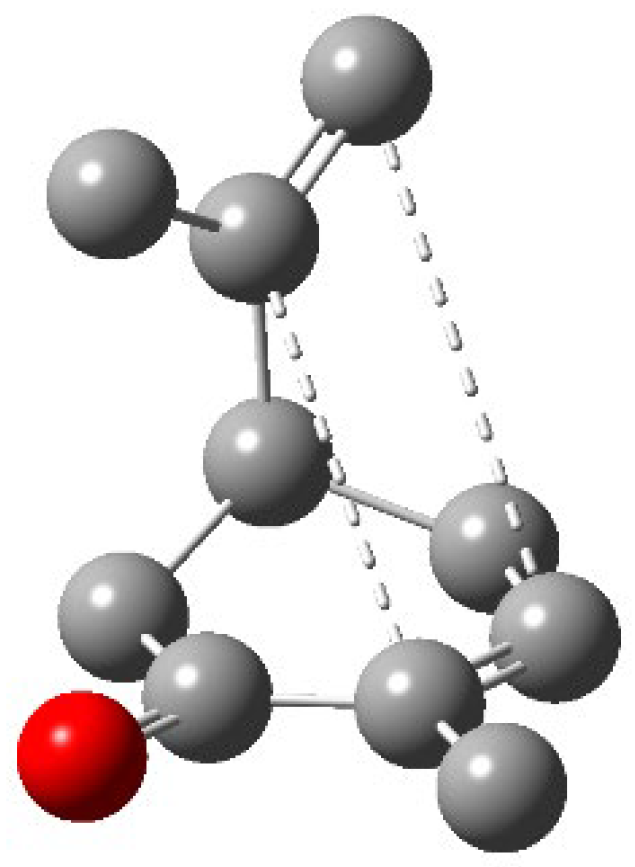

The triplet state is a distorted hexagonal structure with a relevant radical character on the carbon atom in β to the carbonyl group (

Figure 5).

Triplet state can be converted into the biradical

6 (

Scheme 4,

Figure 4) through a very small transition state TS1 (0.22 eV) (

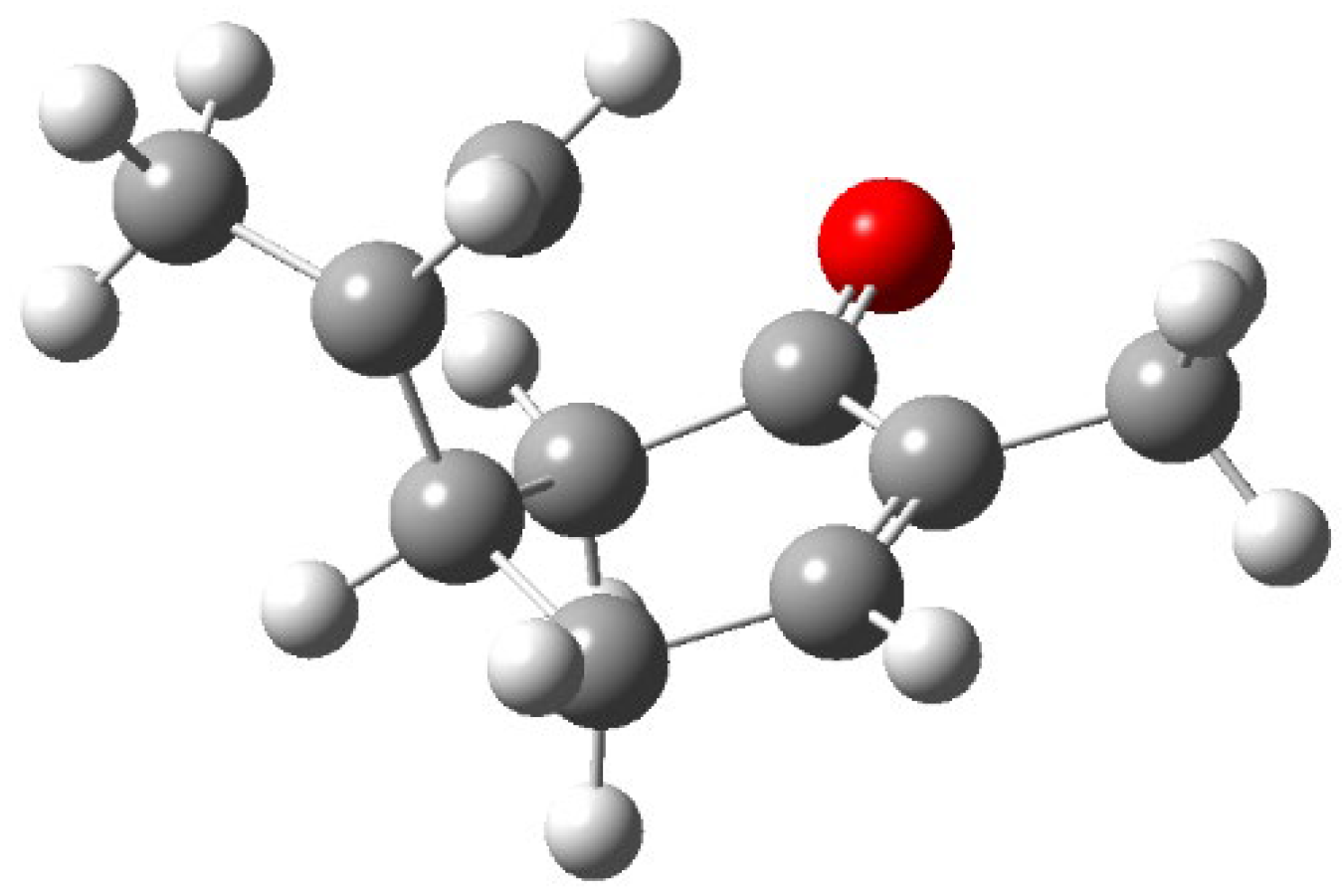

Figure 4). The transition state showed a significant conformational deformation of the structure of the triplet state (

Figure 6). While isopropylene side chain in the triplet is quite on the same plane of the cyclohexenone, in the transition state the side chain is orthogonal to cyclohexenone. The double bond in isopropylene is broken but the new bond with the carbon atom in β position to the carbonyl group is not formed. The double bond in the cyclohexanone is intact. The transition state appears to be an early one.

The following ring closure to the final tricyclic product needs to go beyond a transition state with an energy of 0.93 eV (

Figure 4). Also in this case, the transition state is an early one. It is noteworthy that compound

2, the final product of the reaction, has energy higher than that of the starting material. The reaction is thermodynamically forbidden. This datum can explain the low yields reported for the reaction from

1 to

2.

To test the possible presence of a [2+2]-cycloaddition reaction in the first excited singlet state, we performed CASSCF(6,6) calculations at 6-311G+(d,p). The calculations did not allow to determine the presence of conical intersection in the first excited singlet state.