1. Introduction

Chronic Kidney Disease, a disease which causes a loss of kidney function, mostly stays quiet until it has developed a lot and is almost too late. CKD is a huge problem worldwide. It has big consequences, such as the death rate increasing, due to late detection and bad disease complications. Treatment is not as effective either. Discovering CKD early is very important because it lets you do something about it, stopping how bad it gets, lowering side effects or outcomes and of course keeping the patient healthy longer. Physicians rely on estimated glomerular filtration rate and proteinuria statistics, especially on patients with diabetes or high blood pressure as well as their individual blood families.

Machine learning is making way for better medical diagnoses. It analyses big data and helps doctors find the solution in the end. This complicated formula can help doctors in noticing a lot that they wouldn’t notice by themself and then do things to help people better. Gradient boosting algorithms get the job done for prediction; where most programs fail - to capture the relationship between nonlinear information and the subject.

To make a good model you have to pick just the right factors. Feature selection simplifies complicated data by choosing which clinical variables are the most important and most relevant, thereby creating a more efficient model. According to the NIDDK this new approach helps doctors to understand why they are better or worse at giving you the predators. A study will analyse the detection of early kidney disease by combining two methods to improve the chances of getting a correct diagnosis and give more confidence in prediction.

1.1. Background on Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) it is a progressive medical illness that occurs when kidneys gradually lose ability to function properly for at least three months. It impairs the kidney to filter waste and excess fluid from blood. Around 10-14% of individuals globally suffer from CKD, especially common among older people. According to reports, approximately 850 million individuals around the world suffer from kidney diseases, particularly CKD and acute kidney injury. In the United States, approximately 14% of adults, which equals 35.5 million people, have chronic kidney disease (CKD). However, some of them do not know that they have it. Diabetes, high blood pressure, heart diseases, and old age are the major risk factors of the illness, which is responsible for its high disability and mortality burden. The early stages of the disease are usually asymptomatic and screenings and diagnosis are important to prevent kidney failure that will need dialysis and transplant.

1.2. Importance of Early Detection

Finding kidney disease early is important. When we find it early, we can give treatment to help slow down the disease. This can help people not get heart disease, kidney failure, or die early. Without a diagnosis, advanced natural course of chronic kidney disease generally occurs till the later stages. Limited treatment options and increased invasiveness are noted at this stage. Routine screening is advised for high-risk individuals, namely those with diabetes, high blood pressure or a family history. Screening can be done by simple tests like estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and albuminuria. Using blood pressure medicines, blood sugar medicines, lifestyle changes and kidney protectors works only when done early on. Along with that, when detection occurs early, the quality of life improves and healthcare costs decrease.

1.3. Role of Machine Learning in Medical Diagnosis

Machine learning (ML) has transformed medical diagnostics. High-dimensional clinical data that cannot be addressed with statistics is now analysable with ML. Machine learning algorithms can find hidden patterns and interactions among variables to predict risk, progression and treatment outcomes of disease more accurately. In CKD (chronic kidney disease), ML (Machine Learning) models can harness data from multiple sources like laboratory tests, demographics, and comorbidities for personalized predictions. These models help doctors and nurses by providing decision support tools that enhance the accuracy of diagnoses, help prioritize patients for early intervention, and help allocate resources efficiently. Moreover, Explainable ML methods further build confidence by enabling analysis of prediction decisions.

1.4. Motivation for Using Gradient Boosting and Feature Selection

Gradient boosting algorithms effectively combine the predictions of various weak learners, such as decision trees, in a staged way to produce powerful predictive models. These complicated algorithms allow them to efficiently achieve a proper representation of quite complex and non-linear relationships. Thus, the CKD prediction performance is essentially better than classifiers that are simpler. Nonetheless, big clinical datasets frequently have features that either do not have significance or are redundant. Use of feature selection methods in the use of ID and selection data dimension, overfitting and computing. Therefore, the integration of gradient boosting with feature selection offers a strong, interpretable, and precise modelling framework for CKD risk assessment, enabling its applicability in clinical settings and supporting early diagnosis.

2. Literature Review

Clinically established diagnosis CKD relies primarily on very early laboratory tests. Standard diagnostic tests include the measurement of serum creatinine to derive estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), urinalysis to measure proteinuria using albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR), and imaging via renal ultrasound or MRI to assess kidney structure. A kidney biopsy may be required in uncertain cases for staging. The early detection of chronic kidney disease or CKD is done by careful evaluation of small decreases in the function of the kidney. Apart from that, a presence of protein in the urine also helps to predict progressive kidney failure or impairment. Presently, the clinical guidelines suggest regular screening of high-risk groups, including diabetic and hypertensive pb and family history. Even with these protocols, it is still difficult to identify early CKD and differentiate patients with different risk profiles just by routine biochemical tests.

2.1. Machine Learning Applications in Healthcare

The field of machine learning (ML) has already reshaped healthcare by permitting complex predictive analytics on complex, high-dimensional clinical datasets. It helps improve clinical decision support, personalized treatment, and forecast of diseases. Analytic models of nuanced support vector machines, random forests, gradient boosting, and neural networks identify patterns frequently not identified by standard analysis and drive early diagnosis and risk stratification. Machine learning (ML) is being used in nephrology to improve detection of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in an accurate and prognostic manner by integrating multiple biomarkers, patient demographics and comorbidities. Also, interpretable machine learning approaches enhance the trust of clinicians by explaining key drivers.

2.2. Previous Studies Using Gradient Boosting

Due to its high accuracy and strength and its ability to capture nonlinear relationships, gradient boosting (an ensemble learning technique formed of weak decision trees) is increasingly popular for CKD prediction. In many recent studies, it has been shown that gradient boosting is better able to deal with imbalanced clinical data than traditional models and can identify greater numbers of significant predictors. For example, the classifiers of CKD stages and modelling of disease progress using XGBoost and LightGBM show state-of-the-art results. The importance scores calculated by the algorithm itself can be used to investigate the clinical relevance of variables, which is valuable for interpreting model decisions.

2.3. Feature Selection Techniques in Medical Datasets

In medical datasets, feature selection is key in reducing dimensionality, removing redundant and irrelevant variables, improving overfitting and enhancing interpretability. Tree based importance ranking, mutual features and recursive feature elimination are many techniques that are applied. In predicting CKD, the careful selection of clinical features and laboratory tests helped make prediction better and useful for clinical purpose by fetching to focus important biomarkers and risk factors. When we do feature selection well, we will have the right model. And a model that will generalize well. Moreover, healthcare data is heterogeneous and contains a lot of features.

2.4. Summary and Gap Identification

They use new technology to better predict known as Chronic Kidney Disorder, but they still may make a mistake or not totally know what is wrong with the body. By using feature selection with gradient boosting, predictive performance is said to be better; However, in many studies there is little thorough validation in any place or in multiple places, which is the real world. In addition, there is a need for the right balance between accuracy’s and transparency. There will most probably be more research into gradient boosting so that it can help a little bit with the problem.

3. Gradient Boosting–Based Chronic Kidney Disease Detection Framework with Integrated Feature Selection

The research uses a publicly available Clinical kidney disease dataset of 400 patients with 25 features. These features include demographic details such as age and gender. It also contains clinical measurement like blood pressure and hemoglobin levels. The dataset finally contains laboratory results that include serum creatinine, blood sugar and albumin. Each record is either CKD-positive or CkD-negative for supervised learning. This dataset contains varied profiles of patients with different types of diseases and diseases at different stages. Thus, it is suitable to build predictive models for the early detection of CKD.

3.1. Source of Data

The dataset is gotten from the UCI Machine Learning Repository which hosts de-identified patient data suited for research. The dataset is validated a lot, so it can be used for model training and benchmarking in CKD prediction.

3.2. Data Preprocessing and Cleaning

Clinical data often contains a lot of missing values, outliers, and categorical variables.

K-Nearest Neighbours (KNN) imputation is used for estimating the values missing. The technique works on the principle of averaging the closest neighbours in the feature space. The purpose of K-Nearest Neighbours imputation is to preserve the data integrity, without throwing away values from the sample.

In order to ensure not to distort the model training dataset, the outliers are detected using Interquartile Range (IQR). The outliers are capped and/or removed.

Categorical Encoding is a method that deals when the feature is subjective like if the person is diabetic or not or somebody has hypertension or not and gets coverts to label encoding or one-hot encoding.

Normalization: Continuous features are normalized with Z-score standardization to bring values to a common scale:

where is the original feature value, is the mean, and is the standard deviation.

3.3. Feature Selection Techniques

Feature selection reduces dimensionality, eliminates redundancy, and enhances model interpretability and performance:

-

Filter Methods:

- ○

Chi-square test evaluates the statistical dependence between categorical features and CKD labels, enabling the removal of irrelevant features.

- ○

Correlation Analysis (Pearson’s r or Spearman’s ) identifies highly correlated continuous features with the target variable to guide selection.

Wrapper Methods:

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) works by removing features with the smallest involvement to the prediction. This is done by training a model iteratively until an optimum feature subset is found. In simple words, RFE’s duty is to find a balance between the complexity of the model and its accuracy.

-

Embedded Methods:

- ○

Tree-Based Importance utilizes embedded feature importance from gradient boosting decision trees computed by the reduction in loss when splitting on the feature.

3.4. Gradient Boosting Algorithm

Gradient Boosting builds a strong classifier by iteratively adding weak learners (decision trees) trained on the residual errors of the previous ensemble to minimize a loss function

. At iteration

m + 1, the model updates according to:

where

is the existing ensemble,

is the new weak learner trained on pseudo-residuals, and

is the step size minimizing the loss.

3.5. Parameter Tuning and Optimization:

Hyperparameters include:

- ○

Learning rate (): Controls contribution of each tree, typically between 0.01 and 0.3.

- ○

Number of trees (): More trees can improve accuracy but increase training time and risk of overfitting.

- ○

Maximum tree depth (): Controls model complexity, deeper trees capture more interactions but risk overfitting.

- ○

Subsampling rate and column sampling control randomness to prevent overfitting.Grid search or randomized search with cross-validation is used for optimal hyperparameter selection.

Implementation Details:

Tools like these can handle missing data and categorical features automatically and run in parallel as they extract subsets of the data.

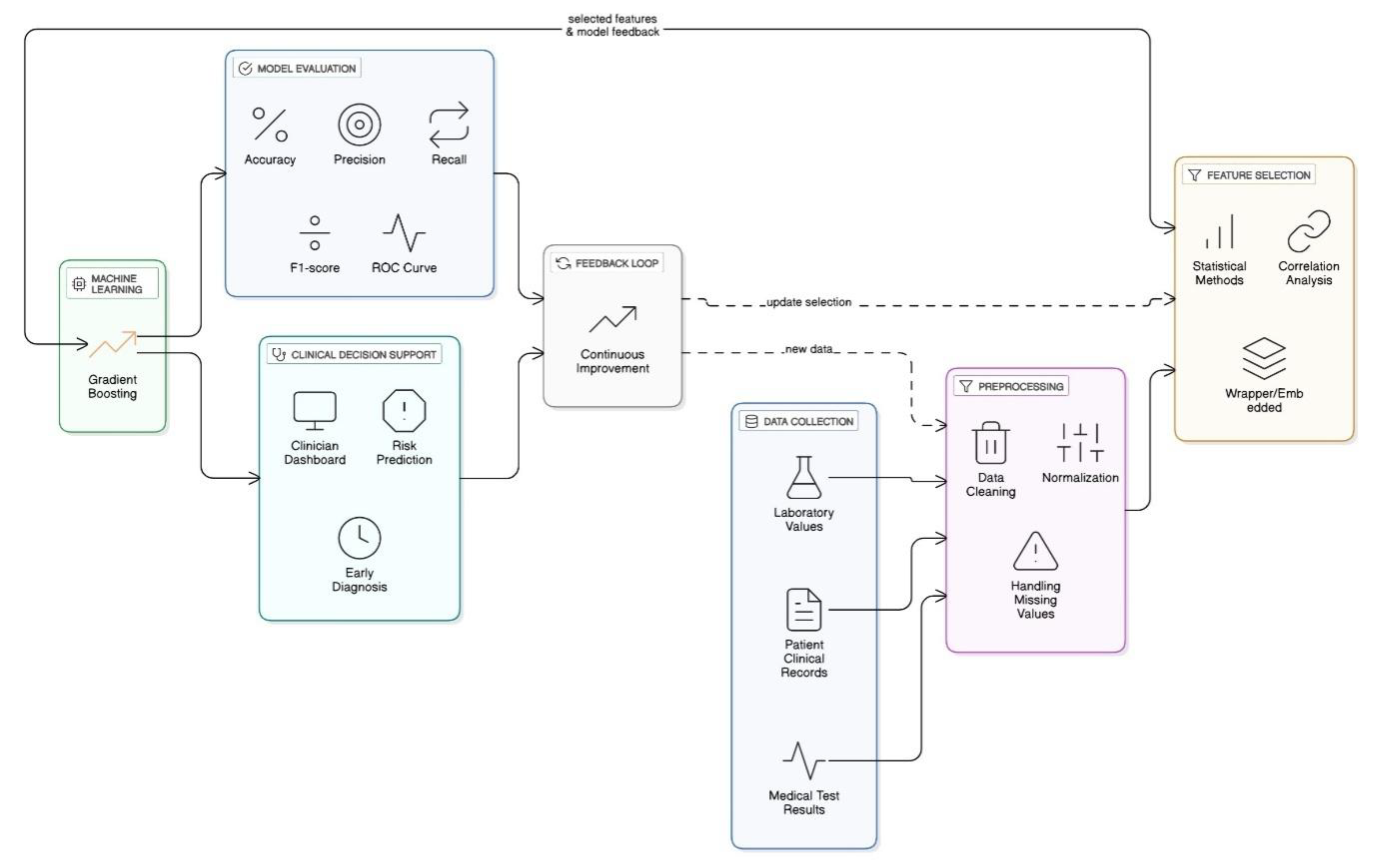

Figure 1.

Architecture for Chronic Kidney Disease Detection Using Gradient Boosting with Feature Selection Techniques.

Figure 1.

Architecture for Chronic Kidney Disease Detection Using Gradient Boosting with Feature Selection Techniques.

3.6. Experimental Setup

The datasets are split into 80% train and 20% test. The training set is subjected to five-fold cross-validation to tune and validate the parameters of the model for generalization and overfitting.

Evaluation focuses on several key metrics defined as follows:

- ○

Accuracy:

The proportion of correctly classified instances out of total instances.

- ○

Precision:

The proportion of correctly predicted positive cases over all predicted positives.

- ○

Recall (Sensitivity):

The proportion of correctly identified positive cases over all actual positives.

- ○

F1-Score:

The harmonic mean of precision and recall to balance false positives and false negatives.

- ○

Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC):

Measures the ability to distinguish between classes across threshold levels; value ranges from 0.5 (random) to 1 (perfect).

Here, TP, TN, FP, and FN denote True Positives, True Negatives, False Positives, and False

Negatives respectively

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Feature Selection Outcomes

Selecting a less complicated prediction model will make the model easier to interpret especially in a clinical setting were explanation materials. The CKD dataset was coddled for applying selection method to find relevant feature for predicting diseased attribute. Statistical methods Pearson correlation, Chi-square test and others individually ranked all the features based on their statistical relationship with the target. Wrapper methods, such as Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), evaluate different groups of features, training models and eliminating the least significant ones recursively. Methods like Lasso regularization and tree-based feature importance from models such as XGBoost, selected features during modelling.

The discoveries showed that serum creatinine, albumin, blood pressure, and specific gravity were reported in several methods. To make a long story short, when a feature is frequently selected by the model, it means that feature is clinically useful. On the average, the feature selection methods reduced the input features from 24 to between 8 and 12, depending on the method, without any loss of predictive performance.

4.2. Model Performance Comparison

4.2.1. With and Without Feature Selection

To study the effect of feature selection on model performance, Gradient Boosting models were trained on the complete set of structures as well as the reduced feature sets of the various selection techniques. Models trained using the complete dataset were kept as a baseline. The other models were evaluated based on accuracy, training efficiency, and generalizability.

The baseline often performed worse than supervised models that only used selected features, even though they used less features. This illustrates that a lot of the original data’s features are probably irrelevant or noisy. On top of that the training time decreased while the overfitting is reduced, which is advantageous in clinical setting for faster models.

4.2.2. Across Different Feature Selection Techniques

We evaluated how well each feature selection method improved model performance. The models that were trained with selection of Chi-square features showed slightly better performance than using all of the features. However, both were effective in getting high values for accuracy of the model, and AUC-ROC. RFE and Lasso could also deliver good performance, but they showed some variability as we under sampled the number of features and how they interacted further down in boosting.

A performance comparison table summarizes the number of features and various evaluation metrics used by the techniques. The Chi-square method produced the highest accuracy and interpretability results, signifying that it may be better suited for this clinical study.

The use of embedded methods allows a good trade-off between efficiency and interpretability of features.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

In order to assess our model efficacy, there were different performance metric calculations, each offering a different view. Accuracy measures the percentage of true positive and true negative predictions out of all the predictions made by the model. The F1-score combines both metrics, allowing for a single score for both recall and precision.

In medicine data science, the “gold standard” metric is the AUC-ROC, which is the model’s ability to discriminate between positive (CKD) and negative (non-CKD). An AUC value of 1.0 indicates perfect judgement. The AUC scores of all models in this study were 0.95 and above. Also, the feature-selected models performed slightly better than the baseline of full features (i.e., thanks to using feature selection). Choosing the right features does not lower the predictive quality of a model and may even improve it.

4.4. Visualization of Results

4.4.1. Confusion Matrix

Confusion matrix clearly depicted the result of model’s prediction with the help of true positive, true negative, false positive and false negative. Models that selected features produced fewer false negatives, which is important in medical diagnostics for chronic kidney disease because a false negative is serious. The model’s high true positive rate suggested a good accuracy of the model towards actual CKD detection.

4.4.2. ROC Curves

All models produced Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves depicting the sensitivity and specificity relationship. The ROC curves were all significantly bowed towards the top-left, indicating strong classification. Models that used smaller subsets of the individual features had higher AUCs, which further corroborates the fact that dimensionality reduction helps enhance model quality.

4.4.3. Feature Importance Plots

We generated feature importance plots from the internal of tree-based algorithms and Lasso coefficients. At the top of the rankings were serum creatinine, albumin, and blood urea. These results corresponded with the medical literature which reinforces the clinical validity of the model. By examining these visualizations, clinicians can understand which parameters are most influential in making predictions, and this will help them trust the outcomes.

4.5. Discussion of Findings

Through analysis, Gradient Boosting combined with techniques that select features provides us better-performing while interpretable and complex model. Choosing features helped with resources needed to run a machine boost algorithm. Therefore, resource optimization has added value.

In clinical practice, predictive performance of the model and transparency have to be balanced. The proposed approach reduces the model to key medically relevant features so that clinicians understand and trust the resulting predictions. The proposed method is more efficient and interpretable than the existing methods reported in the literature, while being more competitive. The appropriate balance of the software makes it a suitable candidate for real-world application.

Despite some shortcomings, such as interference from unbalanced data and absent external validation from different patients, the results remain promising. The limitations indicated that future work should focus on making the model more robust and testing it clinically.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Results in Clinical Context

The study shows that the Gradient Boosting algorithm and robust feature selection can improve the performance on chronic kidney disease (CKD) classification in this study. According to the clinical models, the most influential features are serum creatinine, albumin, specific gravity and blood pressure which are known kidney function markers. The strong association between CKD and either the literature or model consequences gave the machine learning approach credibility. Most Importantly, the considerable sensitivity (recall) of the model along with its AUC-ROC value suggests that the model may also identify at risk patients. It is particularly useful in a clinical setting where early diagnosis is possible to prevent the progression to end-stage renal disease. There will be less need for dialysis or transplantation.

5.2. Benefits of the Proposed Approach

The recommended method offers many benefits for both technology and doctors. To begin with, Gradient Boosting is an ensemble model. As a result, it attains high accuracy in various metrics. Also, the use of feature selection techniques ensures a simpler model that is interpretable, and that clinicians can understand and trust. Less input features mean lower computation costs, quicker training, faster inference, and deployment in resource-constrained healthcare environments. All in all, the method is accurate, efficient, and transparent, three essential requirements for approving machine learning tools in clinical settings.

5.3. Comparison with Existing Methods

The proposed approach performs better than traditional statistical methods and machine learning models which use the entire feature set in terms of accuracy and generalization. The existing works for CKD detection mostly use black-box models or ignore the importance of feature selection, which acts as a bias-inducing shield and brings condensed clinical usability owing to overfitting complications. In contrast, we are not only interested in prediction performance but also the interpretability of results for clinical use. Additionally, Gradient Boosting does a better job at prediction than decision trees or logistic regression which are easier to interpret. As such, this work offers a more realistic and effective solution for CKD detection that outperforms the majority of prevailing works in performance and applicability.

5.4. Limitations of the Study

This study has many limitations, despite its great results. One major limitation is that it used a single dataset, and as a result, may not reflect the full diversity of CKD expressions. Inappropriately, the dataset size and class imbalance may limit the generalizability of the model. Along with this, the features selected are clinically relevant, the model would benefit from temporal data or longitudinal patient histories, which could shed light on disease progression. In addition, while feature importance plots offer some interpretability, the model is still a complex ensemble that may be a problem in circumstances where the model must be fully transparent.

5.5. Potential for Real-World Implementation

From the findings of this study, it can be said that there is great potential for real-world implementation in clinical decision support systems (CDSS). Because the feature set is reduced, the accuracy and inference time are pretty good. The model should be suitable for a hospital information system or EHR. If patients are identified early on that are high-risk patients, then clinicians would be able to prioritize diagnostic tests, make treatment plans, as well as monitor patient progress. Before deploying the model, it should be validated on larger and more diverse datasets, especially in clinic real-time data. Also, the safe adoption of models in healthcare must ensure that privacy and responsibilities of the model must be taken care of.

6. Conclusion

A study was performed on a new type of CKD detection using machine learning technology and feature selection techniques for a practical medical tool. Results that come from doing the process with the boosters have the potential to be significant and accurate at the same time, something that is very important to have. The decision-making process has an easier outcome due to less redundant information. The experiment shows that it can help detection of kidney diseases and stop any complications from happening sooner allowing for better care. This study is a big step in creating new ways for hospitals to help patients get better, and help doctors make better decisions in the process.

Future Enhancements

This model produces acceptable results, however, there is potential for enhancement. Future analysis could target growing the dataset to make enhancements in how well it replicates other health systems and stay resilient. A recent breakthrough in predicating accurate results was recent as deep learning became more popular. Incorporating transparent reasoning techniques into AI will increase trust between A.I. and humans, people may be more likely to use A.I. to make some important decisions. Continuous patient data collection and IoT-enabled devices could possibly provide a wider range of health monitoring options accompanied by decision support systems. Also, more medical work environments will be able to use private model training going on now in the health care world. The enhancements will change the proposed solution so it gets better results and can help more people in many real-world medical situations.

References

- Sharma, T., Reddy, D. N., Kaur, C., Godla, S. R., Salini, R., Gopi, A., & Baker El-Ebiary, Y. A. (2024). Federated Convolutional Neural Networks for Predictive Analysis of Traumatic Brain Injury: Advancements in Decentralized Health Monitoring. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science & Applications, 15(4). [CrossRef]

- KP, A., & John, J. (2021). The Impact Of COVID-19 On Children And Adolescents: An Indianperspectives And Reminiscent Model. Int. J. of Aquatic Science, 12(2), 472-482.

- Akhila, K. P., & John, J. (2024). Deliberate democracy and the MeToo movement: Examining the impact of social media feminist discourses in India. In The Routledge International Handbook of Feminisms in Social Work (pp. 513-525). Routledge.

- John, J., & Akhila, K. P. (2019). Deprivation of Social Justice among Sexually Abused Girls: A Background Study.

- Labhane, S., Akhila, K. P., Rane, A. M., Siddiqui, S., Mirshad Rahman, T. M., & Srinivasan, K. (2023). Online Teaching at Its Best: Merging Instructions Design with Teaching and Learning Research; An Overview. Journal of Informatics Education and Research, 3(2).

- Mohammed, M. A., Fatma, G., Akhila, K. P., & Sarwar, S. (2023). Discussion on the role of video games in childhood studying. European Chemical Bulletin, Budapest, 12(7), 318-341.

- Akhila, K. P., & John, J. (2021). The Impact Of COVID-19 On Children And Adolescents: An Indianperspectives And Reminiscent Model. Science, 12(02), 2021.

- Prabhu Kavin, B., Karki, S., Hemalatha, S., Singh, D., Vijayalakshmi, R., Thangamani, M., ... & Adigo, A. G. (2022). Machine learning-based secure data acquisition for fake accounts detection in future mobile communication networks. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, 2022(1), 6356152. [CrossRef]

- Kalaiselvi, B., & Thangamani, M. (2020). An efficient Pearson correlation based improved random forest classification for protein structure prediction techniques. Measurement, 162, 107885. [CrossRef]

- Raja, A. S., Peerbasha, S., Iqbal, Y. M., Sundarvadivazhagan, B., & Surputheen, M. M. (2023). Structural Analysis of URL For Malicious URL Detection Using Machine Learning. Journal of Advanced Applied Scientific Research, 5(4), 28-41. [CrossRef]

- Peerbasha, S., & Surputheen, M. M. (2021). Prediction of Academic Performance of College Students with Bipolar Disorder using different Deep learning and Machine learning algorithms. International Journal of Computer Science & Network Security, 21(7), 350-358.

- Mohan, M., Veena, G. N., Pavitha, U. S., & Vinod, H. C. (2023). Analysis of ECG data to detect sleep apnea using deep learning. Journal of Survey in Fisheries Sciences, 10(4S), 371-376.

- Vinod, H. C., & Niranjan, S. K. (2018, January). Multi-level skew correction approach for hand written Kannada documents. In International Conference on Information Technology & Systems (pp. 376-386). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Geeitha, S., & Thangamani, M. (2018). Incorporating EBO-HSIC with SVM for gene selection associated with cervical cancer classification. Journal of medical systems, 42(11), 225. [CrossRef]

- Thangamani, M., & Thangaraj, P. (2010). Integrated Clustering and Feature Selection Scheme for Text Documents. Journal of Computer Science, 6(5), 536. [CrossRef]

- Peerbasha, S., & Surputheen, M. M. (2021). A Predictive Model to identify possible affected Bipolar disorder students using Naive Baye’s, Random Forest and SVM machine learning techniques of data mining and Building a Sequential Deep Learning Model using Keras. International Journal of Computer Science & Network Security, 21(5), 267-274.

- Naveen, I. G., Peerbasha, S., Fallah, M. H., Jebaseeli, S. K., & Das, A. (2024, October). A machine learning approach for wastewater treatment using feedforward neural network and batch normalization. In 2024 First International Conference on Software, Systems and Information Technology (SSITCON) (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

- Vinod, H. C., & Niranjan, S. K. (2017, November). De-warping of camera captured document images. In 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Consumer Electronics (ISCE) (pp. 13-18). IEEE.

- Kakde, S., Pavitha, U. S., Veena, G. N., & Vinod, H. C. (2022). Implementation of A Semi-Automatic Approach to CAN Protocol Testing for Industry 4.0 Applications. Advances in Industry 4.0: Concepts and Applications, 5, 203.

- Gangadhar, C., Chanthirasekaran, K., Chandra, K. R., Sharma, A., Thangamani, M., & Kumar, P. S. (2022). An energy efficient NOMA-based spectrum sharing techniques for cell-free massive MIMO. International Journal of Engineering Systems Modelling and Simulation, 13(4), 284-288. [CrossRef]

- Surendiran, R., Aarthi, R., Thangamani, M., Sugavanam, S., & Sarumathy, R. (2022). A systematic review using machine learning algorithms for predicting preterm birth. International Journal of Engineering Trends and Technology, 70(5), 46-59. [CrossRef]

- Vinod, H. C., Niranjan, S. K., & Anoop, G. L. (2013). Detection, extraction and segmentation of video text in complex background. International Journal on Advanced Computer Theory and Engineering, 5, 117-123.

- Vinod, H. C., & Niranjan, S. K. (2020). Camera captured document de-warping and de-skewing. Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience, 17(9-10), 4398-4403. [CrossRef]

- Peerbasha, S., Iqbal, Y. M., Surputheen, M. M., & Raja, A. S. (2023). Diabetes prediction using decision tree, random forest, support vector machine, k-nearest neighbors, logistic regression classifiers. JOURNAL OF ADVANCED APPLIED SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH, 5(4), 42-54. [CrossRef]

- Peerbasha, S., Habelalmateen, M. I., & Saravanan, T. (2025, January). Multimodal Transformer Fusion for Sentiment Analysis using Audio, Text, and Visual Cues. In 2025 International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Computational Networks (ICISCN) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Keshamma, E., Rohini, S., Sankara Rao, K., Madhusudhan, B., & Udaya Kumar, M. (2008). Tissue culture-independent in planta transformation strategy: an Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated gene transfer method to overcome recalcitrance in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Journal of cotton science, 12(3), 264-272.

- Sundaresha, S., Manoj Kumar, A., Rohini, S., Math, S. A., Keshamma, E., Chandrashekar, S. C., & Udayakumar, M. (2010). Enhanced protection against two major fungal pathogens of groundnut, Cercospora arachidicola and Aspergillus flavus in transgenic groundnut over-expressing a tobacco β 1–3 glucanase. European journal of plant pathology, 126(4), 497-508. [CrossRef]

- Thamilarasi, V., & Roselin, R. (2021, February). Automatic classification and accuracy by deep learning using cnn methods in lung chest X-ray images. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 1055, No. 1, p. 012099). IOP Publishing.

- Thamilarasi, V., & Roselin, R. (2019). Lung segmentation in chest X-ray images using Canny with morphology and thresholding techniques. Int. j. adv. innov. res, 6(1), 1-7.

- Thamilarasi, V., & Roselin, R. (2019). Automatic thresholding for segmentation in chest X-ray images based on green channel using mean and standard deviation. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE), 8(8), 695-699.

- Asaithambi, A., & Thamilarasi, V. (2023, March). Classification of lung chest X-ray images using deep learning with efficient optimizers. In 2023 IEEE 13th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC) (pp. 0465-0469). IEEE.

- Thamilarasi, V., & Roselin, R. (2021). U-NET: convolution neural network for lung image segmentation and classification in chest X-ray images. INFOCOMP: Journal of Computer Science, 20(1), 101-108.

- Thamilarasi, V., Naik, P. K., Sharma, I., Porkodi, V., Sivaram, M., & Lawanyashri, M. (2024, March). Quantum computing-navigating the frontier with Shor’s algorithm and quantum cryptography. In 2024 International conference on trends in quantum computing and emerging business technologies (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

- Inbaraj, R., & Ravi, G. (2020). A survey on recent trends in content based image retrieval system. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(11), 961-965.

- Inbaraj, R., & Ravi, G. (2021). Content Based Medical Image Retrieval System Based On Multi Model Clustering Segmentation And Multi-Layer Perception Classification Methods. Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry, 12(7).

- Chary, S. S., Bhikshapathi, D. V. R. N., Vamsi, N. M., & Kumar, J. P. (2024). Optimizing entrectinib nanosuspension: quality by design for enhanced oral bioavailability and minimized fast-fed variability. BioNanoScience, 14(4), 4551-4569. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J. P., Ismail, Y., Reddy, K. T. K., Panigrahy, U. P., Shanmugasundaram, P., & Babu, M. K. (2022). PACLITAXEL NANOSPONGES’FORMULA AND IN VITRO EVALUATION. Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results, 13(7), 2733-2740.

- Kumar, J. P., Rao, C. M. P., Singh, R. K., Garg, A., & Rajeswari, T. (2024). A comprehensive review on blood brain delivery methods using nanotechnology. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical and Life Sciences, 11(3), 43-52. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S., Krishna, K. M., Joshi, S. S., Radhakrishnan, M., Palaniappan, S., Dussa, S., ... & Dahotre, N. B. (2023). Laser based additive manufacturing of tungsten: Multi-scale thermo-kinetic and thermo-mechanical computational model and experiments. Acta Materialia, 259, 119244. [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, S., Joshi, S. S., Sharma, S., Radhakrishnan, M., Krishna, K. M., & Dahotre, N. B. (2024). Additive manufacturing of FeCrAl alloys for nuclear applications-A focused review. Nuclear Materials and Energy, 40, 101702. [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, S., Man, K., Radhakrishnan, M., Pantawane, M. V., Palaniappan, S., Patil, S. M., ... & Dahotre, N. B. (2023). Microstructure enhanced biocompatibility in laser additively manufactured CoCrMo biomedical alloy. Biomaterials Advances, 150, 213415. [CrossRef]

- Inbaraj, R., & Ravi, G. (2021). Multi Model Clustering Segmentation and Intensive Pragmatic Blossoms (Ipb) Classification Method based Medical Image Retrieval System. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology, 25(3), 7841-7852.

- Inbaraj, R., & Ravi, G. (2020). Content Based Medical Image Retrieval Using Multilevel Hybrid Clustering Segmentation with Feed Forward Neural Network. Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience, 17(12), 5550-5562. [CrossRef]

- Sankara Rao, K., Sreevathsa, R., Sharma, P. D., Keshamma, E., & Udaya Kumar, M. (2008). In planta transformation of pigeon pea: a method to overcome recalcitrancy of the crop to regeneration in vitro. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants, 14(4), 321-328. [CrossRef]

- Keshamma, E., Sreevathsa, R., Kumar, A. M., Reddy, K. N., Manjulatha, M., Shanmugam, N. B., ... & Udayakumar, M. (2012). Agrobacterium-mediated in planta transformation of field bean (Lablab purpureus L.) and recovery of stable transgenic plants expressing the cry 1AcF gene. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter, 30(1), 67-78. [CrossRef]

- Entoori, K., Sreevathsa, R., Arthikala, M. K., Kumar, P. A., Kumar, A. R. V., Madhusudhan, B., & Makarla, U. (2008). A chimeric cry1X gene imparts resistance to Spodoptera litura and Helicoverpa armigera in the transgenic groundnut. EurAsia J BioSci, 2, 53-65.

- Keshamma, E., Rohini, S., Rao, K. S., Madhusudhan, B., & Kumar, M. U. (2008). Molecular biology and physiology tissue culture-independent In Planta transformation strategy: an Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated gene transfer method to overcome recalcitrance in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). J Cotton Sci, 12, 264-272.

- Saravanan, V., Sumalatha, A., Reddy, D. N., Ahamed, B. S., & Udayakumar, K. (2024, October). Exploring Decentralized Identity Verification Systems Using Blockchain Technology: Opportunities and Challenges. In 2024 5th IEEE Global Conference for Advancement in Technology (GCAT) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Arunachalam, S., Kumar, A. K. V., Reddy, D. N., Pathipati, H., Priyadarsini, N. I., & Ramisetti, L. N. B. (2025). Modeling of chimp optimization algorithm node localization scheme in wireless sensor networks. Int J Reconfigurable & Embedded Syst, 14(1), 221-230. [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, V., Upender, T., Ruby, E. K., Deepalakshmi, P., Reddy, D. N., & SN, A. (2024, October). Machine Learning Approaches for Advanced Threat Detection in Cyber Security. In 2024 5th IEEE Global Conference for Advancement in Technology (GCAT) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Reddy, D. N., Venkateswararao, P., Vani, M. S., Pranathi, V., & Patil, A. (2025). HybridPPI: A Hybrid Machine Learning Framework for Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Informatics (IJEEI), 13(2).

- Rao, A. S., Reddy, Y. J., Navya, G., Gurrapu, N., Jeevan, J., Sridhar, M., ... & Anand, D. High-performance sentiment classification of product reviews using GPU (parallel)-optimized ensembled methods. [CrossRef]

- NULI, M., KUMAR, J. P., KORNI, R., & PUTTA, S. (2024). Cadmium Toxicity: Unveiling the Threat to Human Health. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 86(5).

- Nelson, V. K., Nuli, M. V., Ausali, S., Gupta, S., Sanga, V., Mishra, R., ... & Jha, N. K. (2024). Dietary anti-inflammatory and anti-bacterial medicinal plants and its compounds in bovine mastitis associated impact on human life. Microbial Pathogenesis, 192, 106687. [CrossRef]

- Putta, S., & Silakabattini, K. (2020). Protective Effect of Tylophora indica against Streptozotocin Induced Pancreatic and Liver Dysfunction in Wistar Rats. Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal, 13(4), 1755-1763. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J., Radhakrishnan, M., Palaniappan, S., Krishna, K. M., Biswas, K., Srinivasan, S. G., ... & Dahotre, N. B. (2024). Cr content dependent lattice distortion and solid solution strengthening in additively manufactured CoFeNiCrx complex concentrated alloys–a first principles approach. Materials Today Communications, 40, 109485. [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, M., Sharma, S., Palaniappan, S., Pantawane, M. V., Banerjee, R., Joshi, S. S., & Dahotre, N. B. (2024). Influence of thermal conductivity on evolution of grain morphology during laser-based directed energy deposition of CoCrxFeNi high entropy alloys. Additive Manufacturing, 92, 104387. [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, S., Palaniappan, S., Pantawane, M. V., Radhakrishnan, M., Patil, S. M., Dowden, S., ... & Dahotre, N. B. (2023). Electrochemical response of heterogeneous microstructure of laser directed energy deposited CoCrMo in physiological medium. Applied Physics A, 129(5), 332. [CrossRef]

- Niasi, K. S. K., Kannan, E., & Suhail, M. M. (2016). Page-level data extraction approach for web pages using data mining techniques. International Journal of Computer Science and Information Technologies, 7(3), 1091-1096.

- Niasi, K. S. K., & Kannan, E. Multi Agent Approach for Evolving Data Mining in Parallel and Distributed Systems using Genetic Algorithms and Semantic Ontology.

- Vidyabharathi, D., Mohanraj, V., Kumar, J. S., & Suresh, Y. (2023). Achieving generalization of deep learning models in a quick way by adapting T-HTR learning rate scheduler. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 27(3), 1335-1353. [CrossRef]

- Jaishankar, B., Ashwini, A. M., Vidyabharathi, D., & Raja, L. (2023). A novel epilepsy seizure prediction model using deep learning and classification. Healthcare analytics, 4, 100222. [CrossRef]

- Hamed, S., Mesleh, A., & Arabiyyat, A. (2021). Breast cancer detection using machine learning algorithms. International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing, 10(11), 4-11. [CrossRef]

- Raja, M. W., & Nirmala, K. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENGINEERING SCIENCES & RESEARCH TECHNOLOGY AN EXTREME PROGRAMMING METHOD FOR E-LEARNING COURSE FOR WEB APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT.

- Banu, S. S., Niasi, K. S. K., & Kannan, E. (2019). Classification Techniques on Twitter Data: A Review. Asian Journal of Computer Science and Technology, 8(S2), 66-69. [CrossRef]

- Mubsira, M., & Niasi, K. S. K. (2018). Prediction of Online Products using Recommendation Algorithm.

- Niasi, K. S. K., & Kannan, E. (2016). Multi Attribute Data Availability Estimation Scheme for Multi Agent Data Mining in Parallel and Distributed System. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research, 11(5), 3404-3408.

- Marimuthu, M., Mohanraj, G., Karthikeyan, D., & Vidyabharathi, D. (2023). RETRACTED: Safeguard confidential web information from malicious browser extension using Encryption and Isolation techniques. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems, 45(4), 6145-6160.

- Lavanya, R., Vidyabharathi, D., Kumar, S. S., Mali, M., Arunkumar, M., Aravinth, S. S., ... & Tesfayohanis, M. (2023). [Retracted] Wearable Sensor-Based Edge Computing Framework for Cardiac Arrhythmia Detection and Acute Stroke Prediction. Journal of Sensors, 2023(1), 3082870.

- Selvam, P., Faheem, M., Dakshinamurthi, V., Nevgi, A., Bhuvaneswari, R., Deepak, K., & Sundar, J. A. (2024). Batch normalization free rigorous feature flow neural network for grocery product recognition. IEEE Access, 12, 68364-68381. [CrossRef]

- Raja, M. W., & Nirmala, D. K. (2016). Agile development methods for online training courses web application development. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research ISSN, 0973-4562.

- Raja, M. W. (2024). Artificial intelligence-based healthcare data analysis using multi-perceptron neural network (MPNN) based on optimal feature selection. SN Computer Science, 5(8), 1034. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).