1. Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), a malignancy arising from the biliary epithelium, presents a formidable challenge in clinical oncology due to its aggressive behavior, limited therapeutic options, and rising global incidence [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Accounting for 15% of primary liver tumors, CCA is relatively rare worldwide but imposes a disproportionately high burden in regions like Thailand, where elevated mortality rates contribute to significant annual deaths [

6,

7]. The disease’s insidious onset and late-stage diagnosis often preclude curative surgical intervention, resulting in a dismal prognosis and 5-year survival rates below 20% [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Although progress has been made in elucidating the molecular pathogenesis of cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), effective methods for its early detection remain elusive. Consequently, there is an urgent need to identify novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets [

9,

12].

Tumor biomarkers, encompassing proteins, nucleic acids, and metabolites derived from biofluids or tissues, are pivotal in oncology for enabling early diagnosis, prognostic stratification, and personalized therapy [

13,

14,

15]. These molecules hold promise for addressing CCA’s diagnostic delays and heterogeneity, as they can predict treatment response, monitor recurrence, and guide precision medicine [

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, challenges such as tumor heterogeneity and technical limitations in biomarker detection hinder clinical translation, necessitating robust candidates with proven mechanistic roles in cancer biology [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

CD44v6, a splice variant of the transmembrane glycoprotein CD44, has emerged as a key player in tumor progression and therapy resistance across multiple cancers [

25,

26]. Generated through the alternative splicing and inclusion of the sixth variant exon (v6), CD44v6 functions as a critical signaling hub by acting as a co-receptor for receptor tyrosine kinases like c-Met and VEGFR. This interaction is essential for presenting growth factors to their receptors, thereby activating key downstream oncogenic pathways, including the PI3K/Akt and Ras/MAPK cascades that regulate cell survival, motility, and proliferation [

25,

27,

28,

29]. Its overexpression correlates with metastatic dissemination, stem-like properties, and poor outcomes, positioning it as both a biomarker and therapeutic target [

30,

31]. Preclinical studies demonstrate that CD44v6 silencing, or antibody-mediated targeting suppresses proliferation, invasion, and metastasis in colorectal, gastric, and breast cancers [

32,

33,

34]. Despite this evidence, CD44v6’s role in CCA remains unexplored, leaving a critical gap in understanding its potential utility in this recalcitrant malignancy.

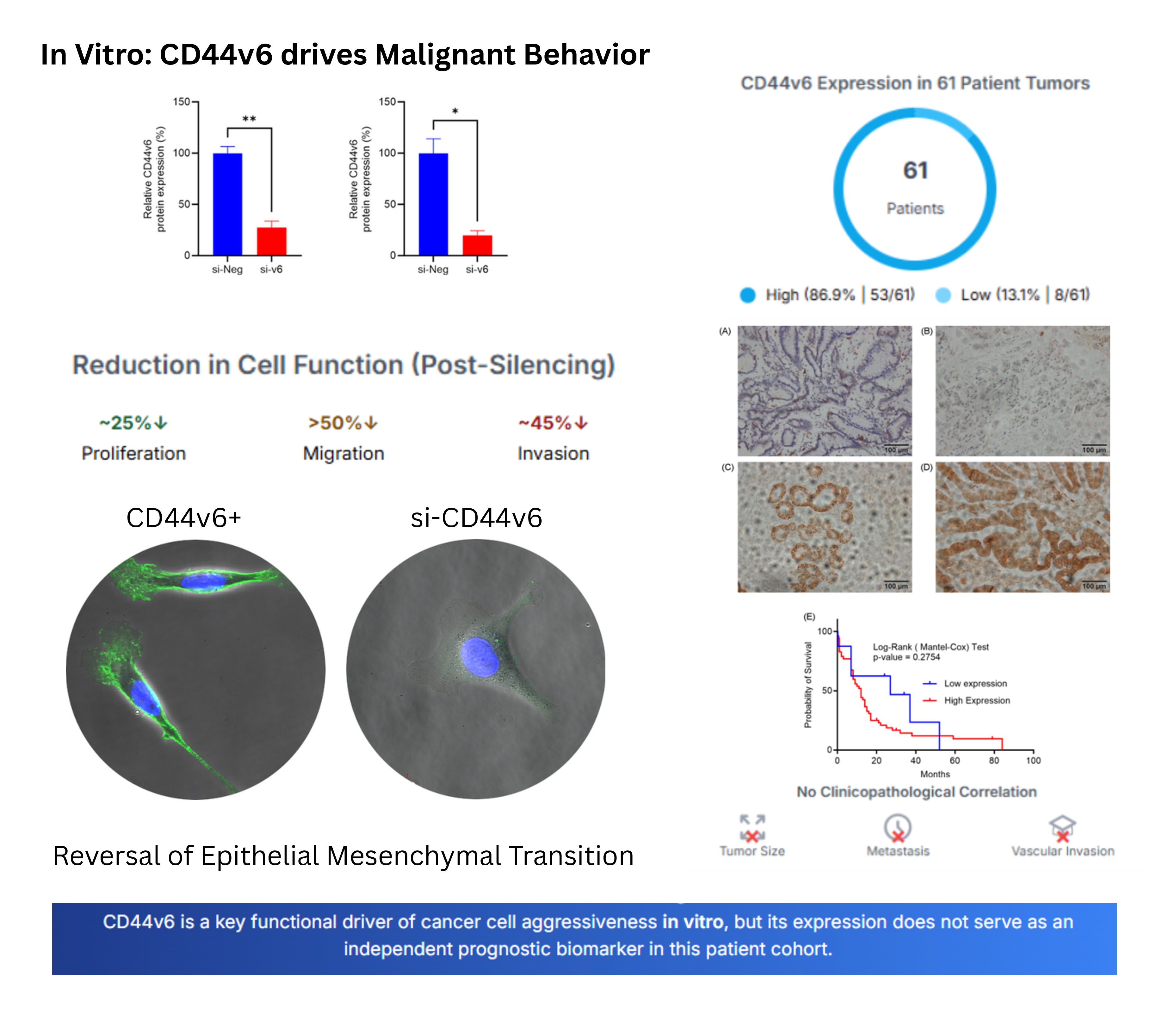

Given the unmet clinical needs in Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) and the oncogenic role of CD44v6 in other cancers, we investigated its function in CCA through integrated in vitro and clinical analyses. While silencing CD44v6 in CCA cell lines effectively reduced proliferation, migration, and invasion, our analysis of a 61-patient cohort found no significant association between CD44v6 expression and clinicopathological outcomes or survival. This conflict between our mechanistic insights and clinical observations highlights the complexities of translating preclinical findings and emphasizes the need to situate CD44v6 within the unique molecular landscape of CCA.

2. Results

2.1. CD44v6 Silencing Reduces Cholangiocarcinoma Cell Proliferation

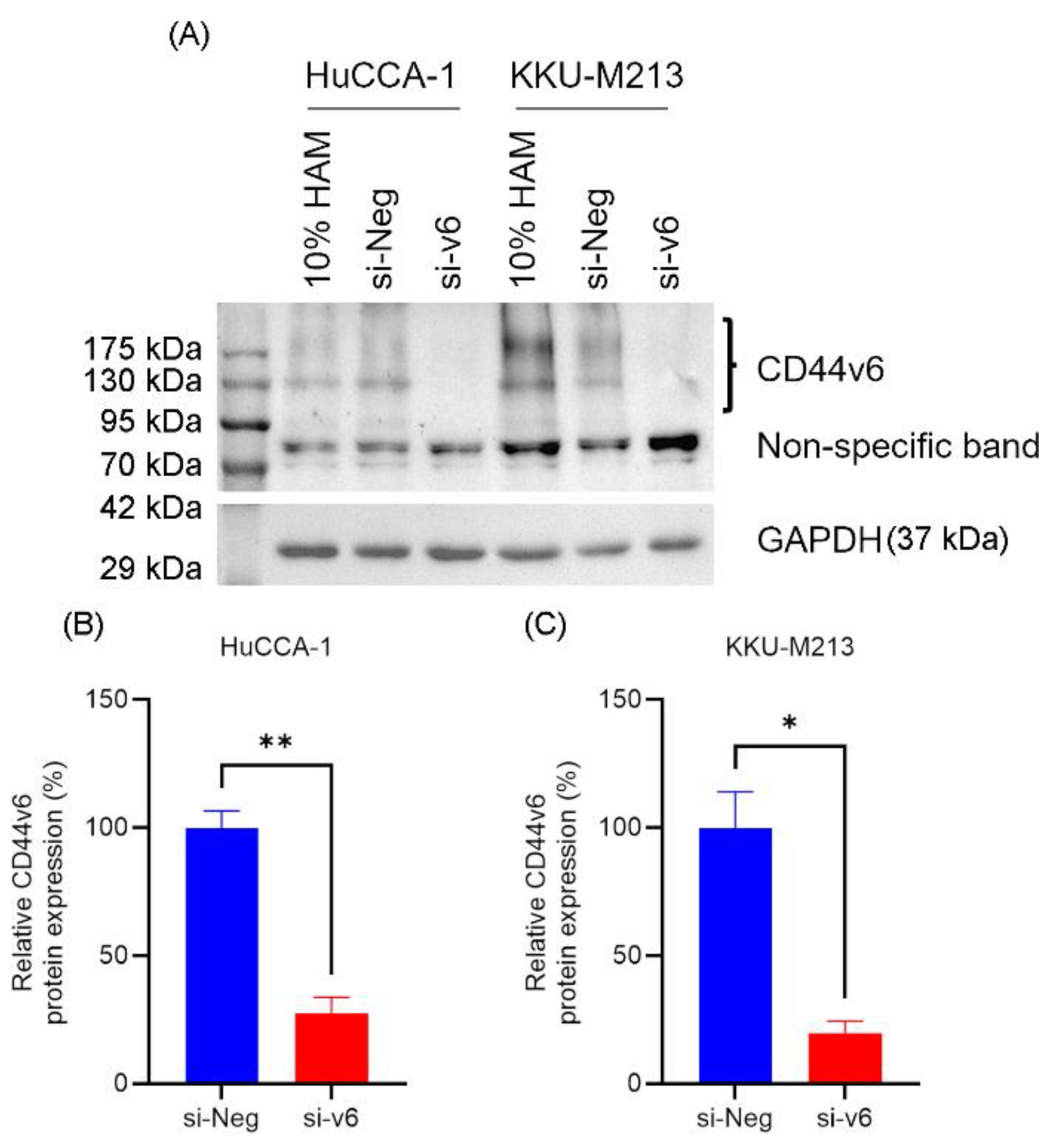

Western blot analysis showed that HuCCA-1 and KKU-M213 cell lines expressed CD44v6 and transfection with CD44v6 siRNA for 48 h significantly reduced the expression of CD44v6 (si-v6) in HuCCA-1 (27.49 ± 6.23 %, p = 0.0187) and KKU-M213 (19.87 ± 4.43 %, p = 0.0042) respectively, compared to negative siRNA control (si-Neg) (

Figure 1B,C).

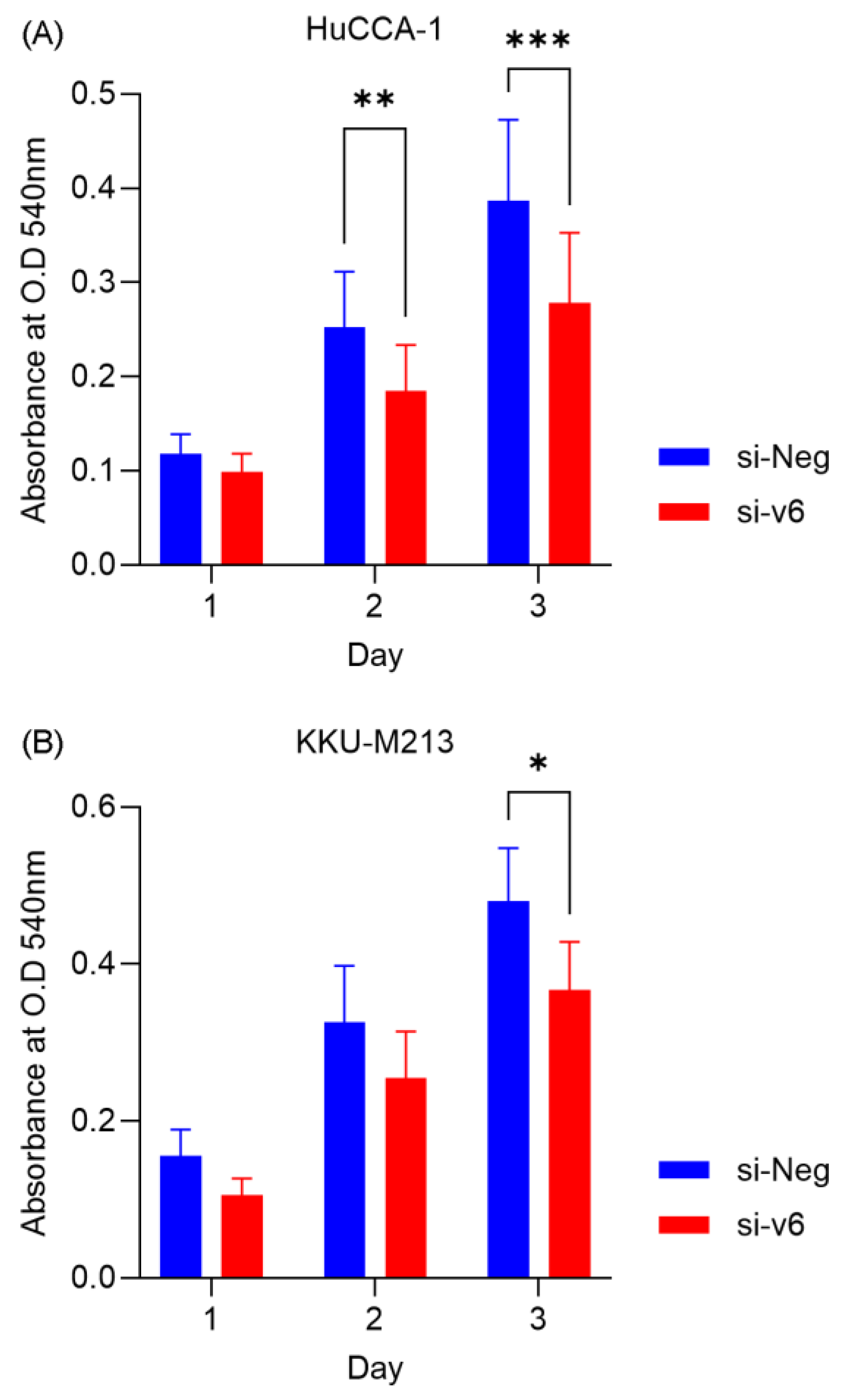

Cell viability assay showed that CD44v6 silencing significantly reduced the viability of HuCCA-1 at Day 2 (73.32 ± 33.33%, p = 0.0272) and Day 3 (72.07 ± 33.08%, p = 0.0205) whereas it reduced the viability of KKU-M213 only at Day 3 (76.42 ± 21.98%, p = 0.0267) (

Figure 2A,B). Targeting CD44v6 significantly reduces CCA proliferation by ~25%. While this suggests its role in controlling cell proliferation is partial, it firmly establishes its biological activity in CCA and supports further investigation into its potentially more critical functions in other cancer hallmarks like migration and invasion.

2.2. CD44v6 Silencing Reduces Migration and Invasion of Cholangiocarcinoma Cells and Induces MET

Given the reported involvement of CD44v6 in metastatic phenotypes [

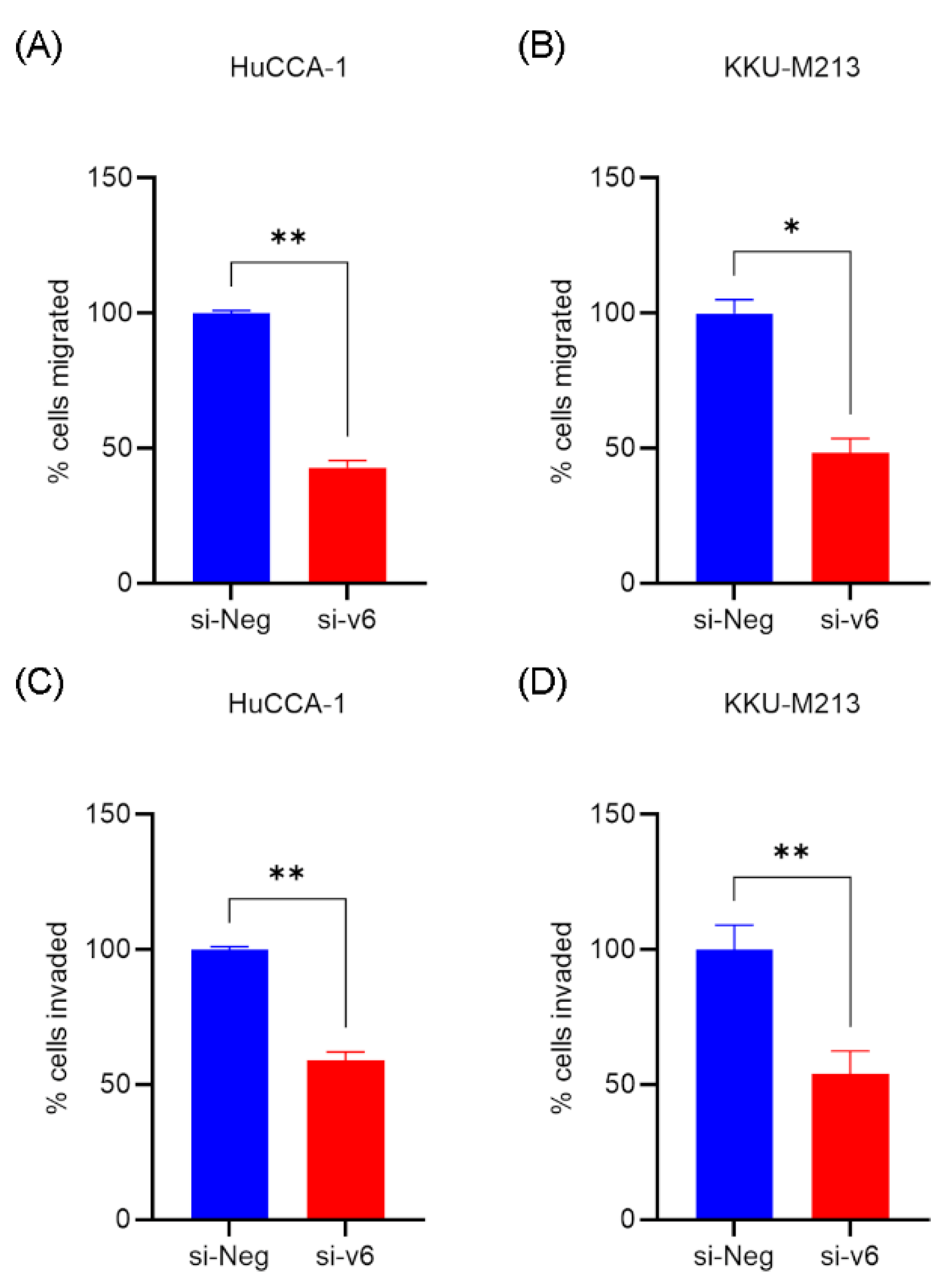

35], we investigated the impact of CD44v6 silencing on cholangiocarcinoma cell behavior. Silencing of CD44v6 significantly reduced the migratory capacity of both HuCCA-1 (42.80 ± 2.68 %, p = 0.0034) and KKU-M213 (48.34 ± 5.23 %, p = 0.0343) cells, as assessed by transwell migration assays. Similarly, CD44v6 silencing impaired the invasive potential of HuCCA-1 (59.10 ± 2.93%, p = 0.0024) and KKU-M213 (54.05 ± 8.39%, p = 0.0027) cells in transwell invasion assays (

Figure 3A–D).

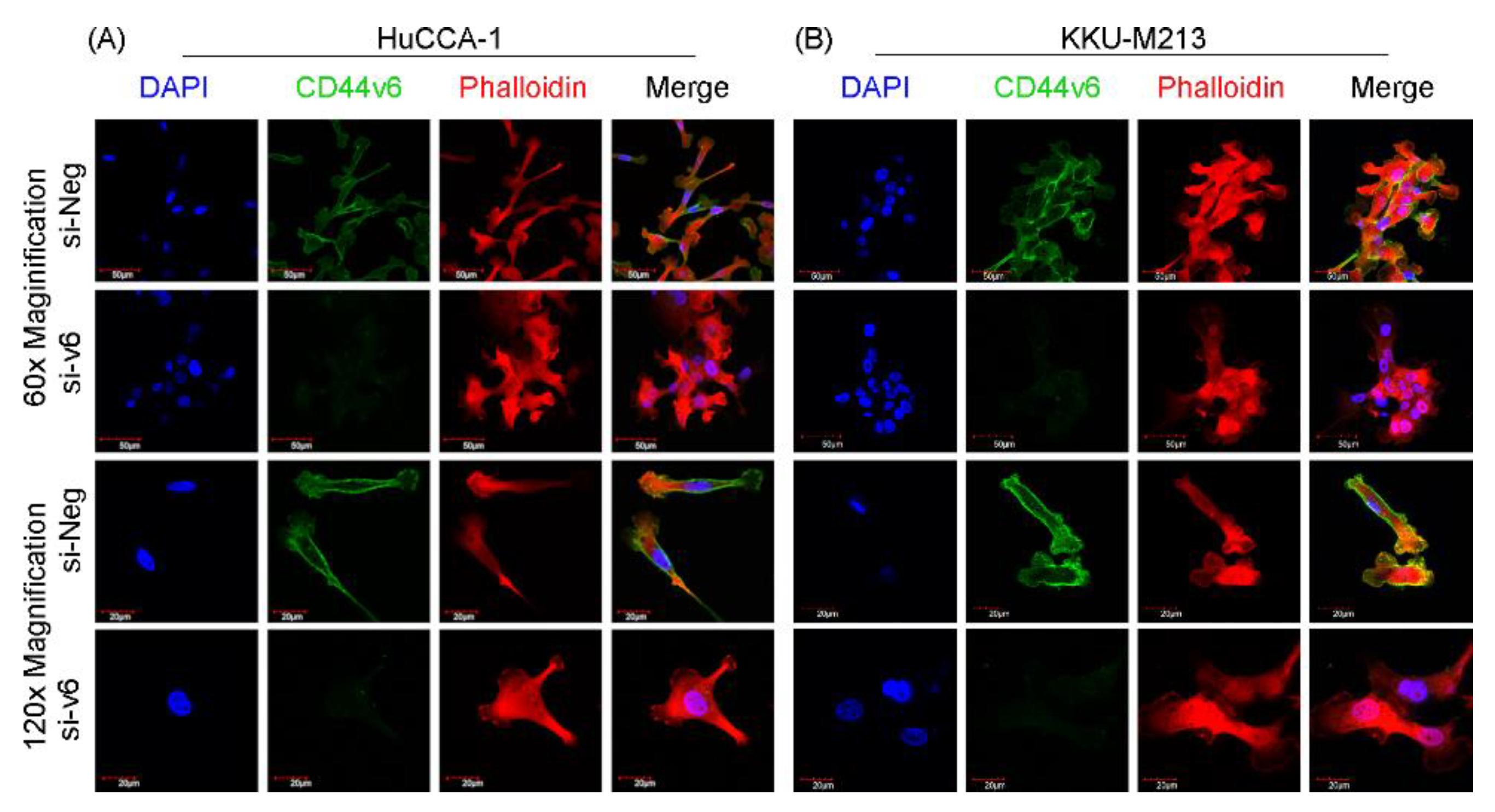

Furthermore, immunofluorescence analysis (

Figure 4A,B) revealed distinct morphological changes in CD44v6-silenced HuCCA-1 and KKU-M213 cells. These cells exhibited a more compact and rounded shape with an organized, clustered arrangement, contrasting with the elongated, spindle-like morphology and scattered, less cohesive arrangement observed in the si-Neg control cells. These morphological changes are consistent with a shift towards a more epithelial-like state, suggesting the induction of a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET).

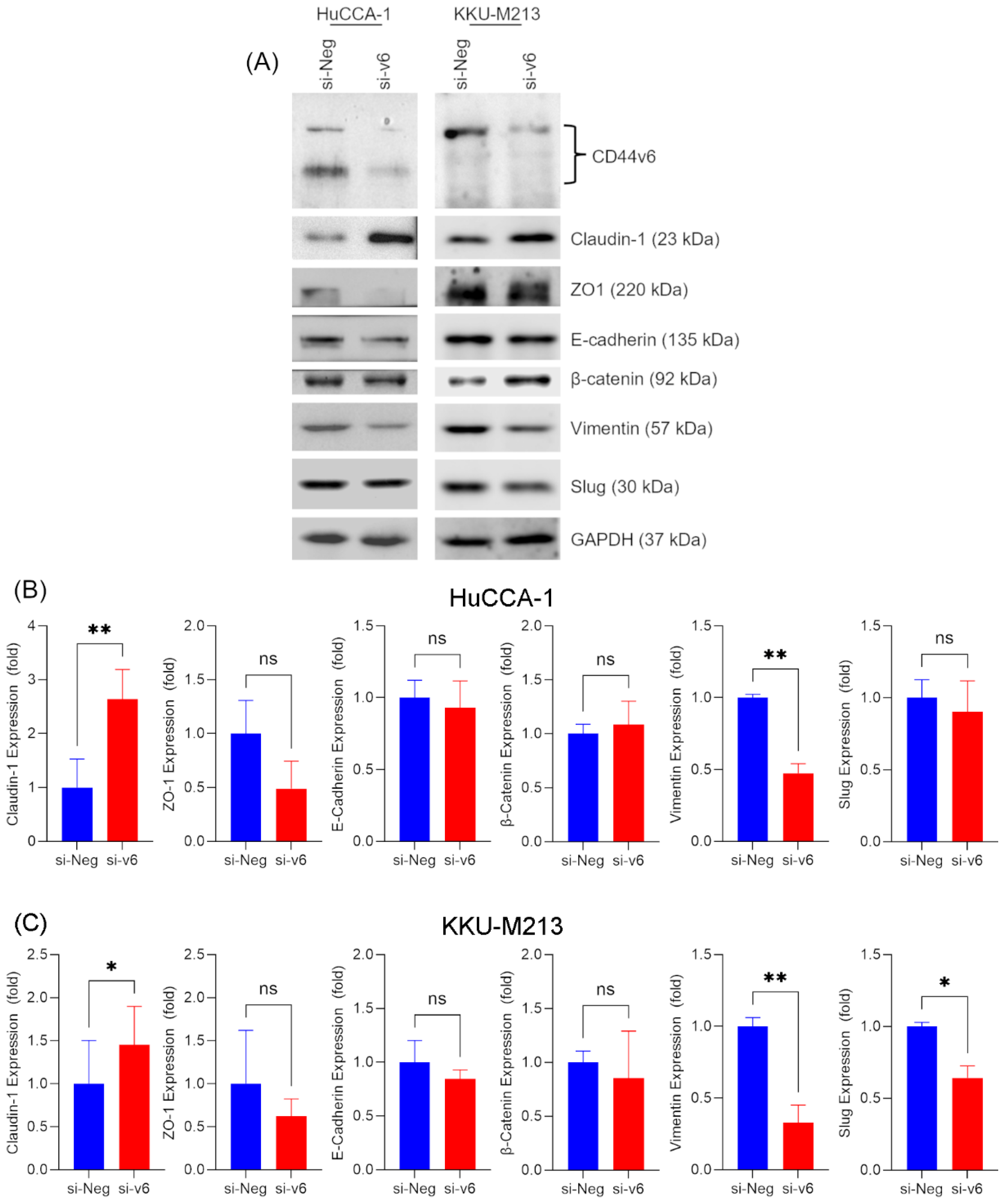

2.3. CD44v6 Silencing Modulates the Expression of Epithelial-Mesenchymal-Transition (EMT) Markers in Cholangiocarcinoma Cells

To confirm that the observed shift towards an epithelial-like morphology was a true MET, we examined the expression of various EMT markers following CD44v6 silencing. Western blot analysis (

Figure 5A) revealed that CD44v6 knockdown significantly increased the expression of Claudin-1 in HuCCA-1 (2.64 ± 0.55-fold, p = 0.0077) and KKU-M213 cells (1.46 ± 0.44-fold, p = 0.0260). However, ZO-1 and E-cadherin, markers of epithelial phenotype were unchanged (

Figure 5B,C).

However, a striking observation was made regarding Vimentin, a mesenchymal marker. CD44v6 silencing led to a marked reduction in Vimentin expression in both HuCCA-1 (0.48 ± 0.07-fold, p = 0.0096) and KKU-M213 (0.33 ± 0.12 fold, p = 0.0098) cells. This downregulation suggests a shift away from a mesenchymal phenotype. Furthermore, we observed a decrease in Slug expression, another mesenchymal marker, in KKU-M213 cells (0.64 ± 0.08, p = 0.0394) whereas no change was observed in HuCCA-1 cell line. Notably, β-catenin expression remained unaffected by CD44v6 silencing in both cell lines (

Figure 5).

These findings collectively indicate that CD44v6 silencing in cholangiocarcinoma cells affects the expression of mesenchymal markers, particularly Vimentin, and the epithelial marker Claudin-1. This suggests that CD44v6 may play a role in maintaining the mesenchymal phenotype in CCA cells, and its downregulation could potentially promote a shift towards a more epithelial state.

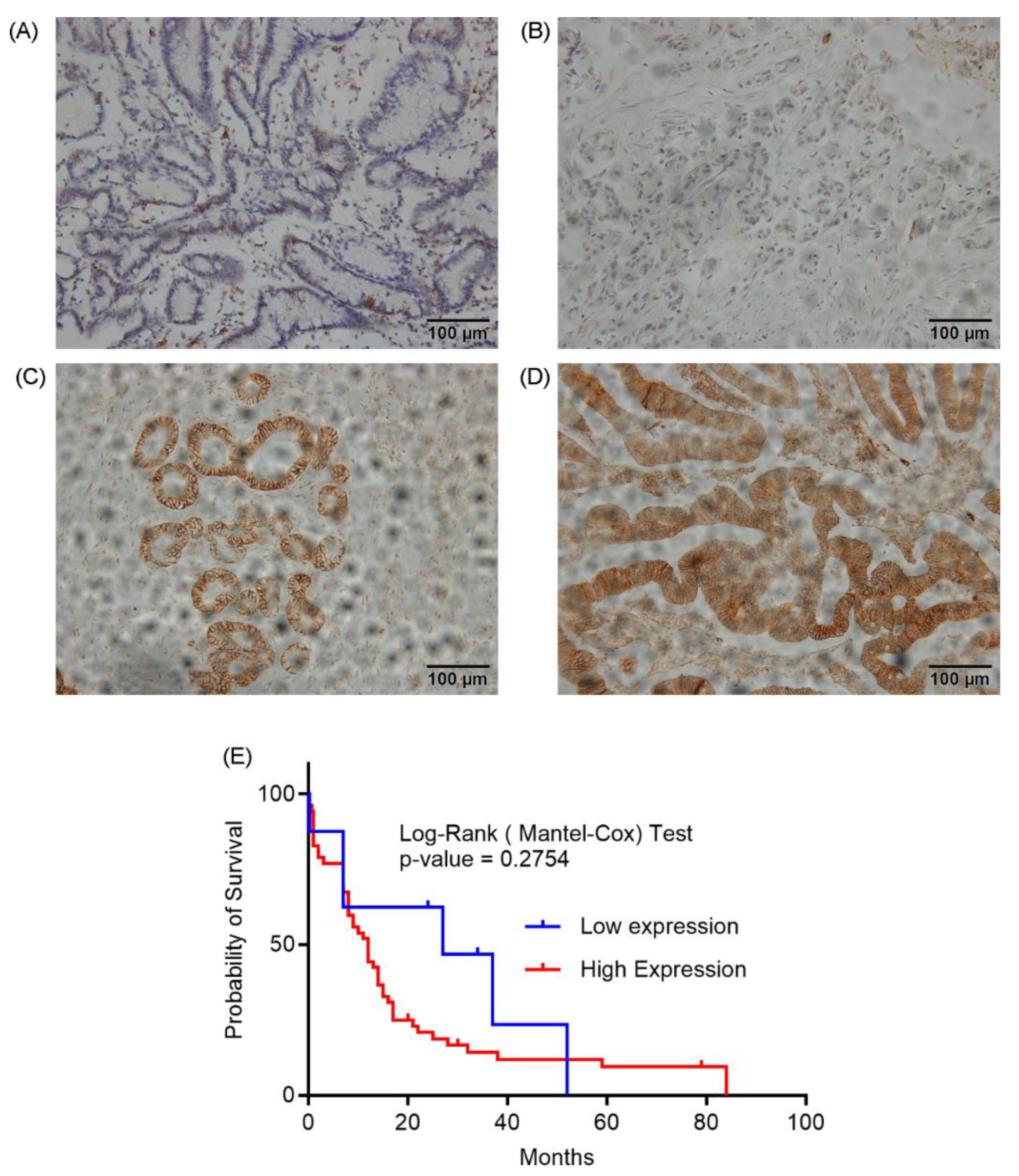

2.4. CD44v6 Expression in Cholangiocarcinoma Tissue and Its Association with Clinicopathological Factors

To evaluate the clinical relevance of CD44v6 in cholangiocarcinoma, we analyzed its expression in tumor tissues from 61 patients. Immunohistochemical staining of paraffinized CCA tissue sections with a polyclonal anti-CD44v6 antibody revealed a wide range of CD44v6 expression levels (

Figure 6A-D). Based on staining intensity, we categorized CD44v6 expression into four grades (0, 1+, 2+, and 3+). Grades 0 and 1+ were designated as low expression, while grades 2+ and 3+ were classified as high expression. A majority of the samples (53/61, 86.9%) exhibited high CD44v6 expression, whereas only 8/61 (13.1%) showed low expression.

We next investigated the association between CD44v6 expression and various clinicopathological parameters (

Table 1). CD44v6 expression did not significantly correlate with sex (p=1.000) or age (<50 vs. ≥50 years; p=1.000). However, we observed trends towards associations between CD44v6 expression and certain tumor characteristics. High CD44v6 expression tended to be associated with larger tumor size (≥5 cm), although this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.520). Extrahepatic tumors were more likely to exhibit high CD44v6 expression compared to intrahepatic tumors (p=0.055). Solitary tumors tended to have higher CD44v6 expression than multiple tumors (p=0.091). No significant association was found between CD44v6 expression and histological grade (p=0.402), lymph node metastasis (p=0.317), distant metastasis (p=0.518), or vascular invasion (p=1.000).

To clarify the clinical relevance of CD44v6, we evaluated its prognostic significance using Kaplan-Meier analysis. While we found that CD44v6 expression was not directly associated with overall survival (

Figure 6E; log-rank p = 0.2754), our analysis did reveal potential trends linking it to specific tumor characteristics, such as size, location, and focality. These findings refine our understanding of CD44v6, suggesting it may contribute to specific aspects of tumor development rather than acting as a robust, standalone prognostic indicator in CCA.

3. Discussion

Our study investigating CD44v6 in cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) revealed complex but significant insights into its biological and clinical roles. Our functional assays indicate a hierarchy in the effects of CD44v6 in CCA cells. While its silencing led to a modest but statistically significant decrease in cell proliferation (~25%), the impact on cell motility was far more pronounced. We observed a dramatic reduction in both migration and invasion, exceeding 50%. These findings align with prior reports implicating CD44v6 in tumor progression across malignancies [

32,

33,

34], particularly its role in metastasis [

30,

31]. Notably, CD44v6-silenced cells exhibited morphological shifts and molecular changes consistent with mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), marked by reduced Vimentin (mesenchymal marker) and elevated Claudin-1 (epithelial marker). This phenotypic reversal suggests CD44v6 may sustain mesenchymal aggressiveness in CCA, and its inhibition could attenuate metastatic potential.

Paradoxically, and in contrast to our strong preclinical data, the clinical analysis of 61 CCA patient tissues revealed no significant associations between CD44v6 expression and clinicopathological features or survival. The modest in vitro effect of CD44v6 on cell proliferation may help explain this lack of independent prognostic significance. The Kaplan-Meier analysis showed no correlation between CD44v6 expression and overall survival; if CD44v6 were a primary driver of overall tumor growth, one would expect its expression levels to correlate more strongly with patient outcomes. This suggests its contribution to tumor burden may be secondary to other oncogenic drivers, explaining why it does not serve as a standalone prognostic marker in this context.

A key reason for the discordance between the strong in vitro invasion data and the clinical analysis is likely a sampling bias within our patient cohort. Of the cases with available data, fewer than 9% had documented distant metastasis. Since the primary role of CD44v6 in vitro was to promote motility and invasion—hallmarks of the metastatic process [

36]—a cohort composed predominantly of patients with non-metastasized tumors lacks the statistical power to reveal this association. This paradox mirrors inconsistencies in other cancers like esophageal carcinoma, where conflicting correlations have been reported [

37,

38,

39]. A meta-analysis, for example, highlighted that CD44v6 only correlated with poor survival in esophageal cancer patients with existing lymphoid metastasis, but not with tumor stage or histology [

40]. Finally, it is important to acknowledge that in vitro models lack the complexity of the tumor microenvironment, and the semi-quantitative nature of immunohistochemistry may also dilute detectable associations.

Our observation that CD44v6 drives a motile, mesenchymal phenotype in CCA cells is well-supported by its known molecular functions in other cancers, where it acts as a major signaling hub. CD44v6 contains peptide motifs that allow it to function as a co-receptor for growth factors like Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), presenting them to their respective receptor tyrosine kinases, c-Met and VEGFR [

25,

28,

29]. In cancers such as colorectal, gastric, and pancreatic, this interaction is critical for activating downstream oncogenic pathways, including Ras/MAPK to promote proliferation and the PI3K/Akt pathway to drive invasion and cell survival [

25,

28,

29].

Furthermore, the cytoplasmic tail of CD44v6 interacts with cytoskeletal linker proteins of the Ezrin-Radixin-Moesin (ERM) family. This physically connects extracellular signals to the actin cytoskeleton, enabling the dynamic remodeling required for cell migration. This mechanism, coupled with CD44v6's ability to regulate the expression and activity of Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs), provides a powerful engine for invasion [

25,

27,

33].

Our finding that silencing CD44v6 induces MET markers aligns with its established role as a cancer stem cell (CSC) marker that maintains a mesenchymal state in gastric, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers [

25,

41]. The lack of a direct clinical correlation in our study does not diminish this biological importance. Instead, it suggests that in the complex in vivo tumor microenvironment, its function is highly context-dependent and may be most critical during the specific step of metastatic dissemination process underrepresented in our patient cohort.

In summary, our research establishes CD44v6 as a functional contributor to key malignant behaviors in CCA. The strong in vitro evidence for its involvement in migration, and invasion, when contrasted with the lack of a direct clinical correlation in our cohort, suggests its function is highly context dependent. This suggests that the primary role of CD44v6 in CCA is not as a standalone prognostic marker, but rather as a powerful facilitator of the metastatic phenotype. This work provides critical insights into CCA's complex biology and underscores the importance of investigating CD44v6 specifically at preventing metastatic progression in CCA.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Lines and Cell Culture

HuCCA-1 and KKU-M213 cell lines were maintained in Ham’s F-12 medium (Gibco, Life technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Life technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere in the presence of 1× antibiotic-antimycotic (Gibco, Life technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA).

4.2. Silencing of CD44v6 Expression by Small Interfering RNA (siRNA)

CD44v6-specific siRNA sequences were purchased from Invitrogen (sense: 5'-GCAACUCCUAGUAGUACAAtt-3'; antisense: 5'-UUGUACUACUAGGAGUUGCtt-3'). A Silencer® Negative Control siRNA (cat. no. 4404021; Ambion; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), which has no homology to any mammalian gene sequence and comprises a 19 bp scrambled sequence with 3' dT overhangs, was used as a negative control. HuCCA-1 and KKU-M213 cells were seeded at a density of 2×10^5 cells per well in 6-well plates and incubated for 24 hours prior to transfection. Cells were then transfected with 20 nM CD44v6 siRNA (si-v6) or negative control siRNA (si-Neg) using Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

4.3. MTT Assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5×103 cells per well in 200 µL of culture medium and incubated overnight at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The following day, cells were transfected with siRNA. After 24 hours, the transfection medium was replaced with Ham's F-12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. At 24-, 48-, and 72-hours post-transfection, the medium was replaced with 200 µL of 0.5 mg/mL MTT (AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany) prepared in Ham's F-12 medium containing 10% FBS, and the cells were incubated for 4 hours at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. The MTT solution was then carefully removed, and 200 µL of analytical-grade DMSO (CAS: 67-68-5, Fisher Chemical, Loughborough, UK) was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. Following a 1-minute shaking, absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a microplate reader (Multiskan EX, Thermo Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland).

4.4. Western-Blot

At 48 hours post-transfection, total cellular protein was extracted as described [

35]. Proteins (30 μg) were resolved on 10% or 12% SDS-PAGE gels at 120 V for 2 h, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (30 V, 4°C, 15 h), and sectioned by molecular weight. The membranes were then cut into sections based on molecular weight markers to allow for probing with different primary antibodies. Membranes were blocked with 3% BSA in TBS-T (1 h, RT), then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted in 1.5% BSA/TBS-T. For experiments requiring multiple membranes, loading controls were probed on each membrane and normalized via densitometry. After washing with TBS-T, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000, 1 h, RT), washed, and visualized using ECL Plus (Bio-Rad) and a G: Box ChemiXL imager (Syngene; Synoptics, Cambridge, UK).

Anti-CD44var (v6) (BMS116) was obtained from eBioscience, Invitrogen. Anti-GAPDH antibody (sc-47724) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA. Anti-claudin-1 (#13255), anti-ZO1 (#8193), anti-E-cadherin (#3195), anti-β-catenin (#8480), anti-vimentin (#5741), anti-slug (#9585), Anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked Antibody (#7074), and Anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked Antibody (#7076) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology®, Beverly, MA, USA. All antibodies were used at a 1:1000 dilution, except for GAPDH, which was used at a 1:2000 dilution. Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ (version 1.54g) [

36].

4.5. Immunofluorescence

Cells were seeded at a density of 2×105 cells per well on sterilized coverslips in 6-well plates and incubated overnight. The following day, CD44v6 silencing was performed. At 48 hours post-transfection, cells were washed with warm serum-free medium and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde containing 2% sucrose in PBS for 20 minutes. Fixed cells were washed three times with PBS for 10 minutes each and blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 hour. Cells were then incubated overnight with an anti-CD44v6 primary antibody diluted 1:1500 in PBS containing 1% BSA. The next day, cells were washed three times with PBS for 10 minutes each and incubated with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (A11034, Thermo Fisher, Eugene, OR, USA). Cells were then counterstained with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated phalloidin (A22283, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA). Fluorescent images were acquired using an FV10i confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

4.6. Transwell Migration and Invasion Assay

At 48 hours post-transfection, HuCCA-1 and KKU-M213 cells were subjected to an in vitro invasion assay using 24-well Transwell chambers with 8 μm pore filters (Transwell, Costar, Boston, MA, USA). Cells (1×105) were suspended in serum-free Ham's F-12 medium and seeded into the upper chamber, which had been pre-coated with 30 μg of Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA). Ham's F-12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS (600 μL) was added to the lower chamber as a chemoattractant. Following a 6-hour incubation at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, non-invading cells on the upper surface of the membrane were removed with cotton swabs, while cells that had invaded through the Matrigel and reached the lower surface were fixed with methanol and stained with 0.5% crystal violet. Invaded cells were counted under a light microscope at 10× magnification. All invasion assays were performed in duplicate and repeated three times independently.

4.7. Immunohistochemistry

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and its later amendments. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Ramathibodi Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand. Paraffin-embedded tissue were sliced into 4-μm- thick sections and analyzed CD44v6 expression by immunohistochemistry on Bond-Max automated immunostainer (Leica Microsystems, Newcastle, UK) using primary monoclonal antibodies against CD44v6 (VFF-18, eBioscience, Austria, 1:500). CD44v6 expression was categorized into four grades based on the intensity and percentage of positively stained cells: grade 0 (negative or <5% positive cells), grade 1+ (weak staining or 5-25% positive cells), grade 2+ (moderate staining or 25-50% positive cells), and grade 3+ (strong staining or >50% positive cells). For statistical analysis, grades 0 and 1+ were designated as low expression, while grades 2+ and 3+ were classified as high expression. Stained sections were visualized using an Olympus BX53 microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, and all experiments were performed in triplicate. Associations between CD44v6 expression and clinicopathological features were analyzed by Chi-square, Student’s t-test and Fisher’s exact test. Survival curve was calculated by using the Kaplan-Meier method. In vitro experimental data were analyzed using the paired t-test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (PASW Statistics 18) or GraphPad Prism 10.4.0.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study establishes CD44v6 as a key functional driver of cholangiocarcinoma cell migration and invasion in vitro, with its silencing leading to a profound reduction in cell motility and a shift toward an epithelial phenotype. However, this potent biological role did not translate into independent prognostic significance in our clinical cohort. This apparent discrepancy highlights a critical insight: CD44v6's primary contribution to CCA progression is likely context-dependent, specifically facilitating the metastatic cascade rather than acting as a standalone prognostic marker.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.T. and K.Z.M.; methodology, K.Z.M., P.R., P.M., H.A. and A.J.; formal analysis, K.Z.M., P.R. and A.J.; investigation, K.Z.M., P.R., P.M., H.A. and A.J.; resources, R.T. and A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, K.Z.M. and R.T.; writing—review and editing, K.Z.M. and R.T; supervision, R.T.; project administration, R.T.; .; funding acquisition, R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Mahidol University (Strategic Research Fund 2025), MU-SRF-RS-11A/68.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and its later amendments. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Ramathibodi Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand (MURA2011/402) (Protocol No. ID 08-54-29).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Mahidol University (Strategic Research Fund 2025), MU-SRF-RS-11A/68. The authors acknowledge the Central Instrument Facility (CIF) and the Center of Nano Imaging (CNI), Faculty of Science, Mahidol University, for providing access to equipment and technical support. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors utilized Gemini 2.5 Pro to enhance readability and language. The authors reviewed and edited the manuscript as necessary and assumed full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCA |

Cholangiocarcinoma |

| siRNA |

Small interfering RNA |

| EMT |

Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition |

| MET |

Mesenchymal-to-Epithelial Transition |

| FBS |

Fetal bovine serum |

| si-v6 |

CD44v6 siRNA |

| si-Neg |

Negative control siRNA |

| MTT |

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| SDS-PAGE |

Sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| BSA |

Bovine serum albumin |

| TBS-T |

Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 |

| HRP |

Horseradish peroxidase |

| ECL |

Enhanced chemiluminescence |

| GAPDH |

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| DAPI |

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

References

- Blechacz, B. Cholangiocarcinoma: Current Knowledge and New Developments. Gut Liver 2017, 11, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeOliveira, M.L.; Cunningham, S.C.; Cameron, J.L.; Kamangar, F.; Winter, J.M.; Lillemoe, K.D.; Choti, M.A.; Yeo, C.J.; Schulick, R.D. Cholangiocarcinoma: thirty-one-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann Surg 2007, 245, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakeeb, A.; Pitt, H.A.; Sohn, T.A.; Coleman, J.; Abrams, R.A.; Piantadosi, S.; Hruban, R.H.; Lillemoe, K.D.; Yeo, C.J.; Cameron, J.L. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg 1996, 224, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.A.; Thomas, H.C.; Davidson, B.R.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet 2005, 366, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosconi, S.; Beretta, G.D.; Labianca, R.; Zampino, M.G.; Gatta, G.; Heinemann, V. Cholangiocarcinoma. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology 2009, 69, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banales, J.M.; Cardinale, V.; Carpino, G.; Marzioni, M.; Andersen, J.B.; Invernizzi, P.; Lind, G.E.; Folseraas, T.; Forbes, S.J.; Fouassier, L.; et al. Expert consensus document: Cholangiocarcinoma: current knowledge and future perspectives consensus statement from the European Network for the Study of Cholangiocarcinoma (ENS-CCA). Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016, 13, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treeprasertsuk, S.; Poovorawan, K.; Soonthornworasiri, N.; Chaiteerakij, R.; Thanapirom, K.; Mairiang, P.; Sawadpanich, K.; Sonsiri, K.; Mahachai, V.; Phaosawasdi, K. A significant cancer burden and high mortality of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in Thailand: a nationwide database study. BMC Gastroenterol 2017, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, T. Cholangiocarcinoma--controversies and challenges. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011, 8, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forner, A.; Vidili, G.; Rengo, M.; Bujanda, L.; Ponz-Sarvise, M.; Lamarca, A. Clinical presentation, diagnosis and staging of cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Int 2019, 39 Suppl 1, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banales, J.M.; Marin, J.J.G.; Lamarca, A.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Khan, S.A.; Roberts, L.R.; Cardinale, V.; Carpino, G.; Andersen, J.B.; Braconi, C.; et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 17, 557–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckmann, K.R.; Patel, D.K.; Landgraf, A.; Slade, J.H.; Lin, E.; Kaur, H.; Loyer, E.; Weatherly, J.M.; Javle, M. Chemotherapy outcomes for the treatment of unresectable intrahepatic and hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a retrospective analysis. Gastrointest Cancer Res 2011, 4, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, T.; Singh, P. Cholangiocarcinoma: emerging approaches to a challenging cancer. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2007, 23, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurisic, V.; Radenkovic, S.; Konjevic, G. The Actual Role of LDH as Tumor Marker, Biochemical and Clinical Aspects. Adv Exp Med Biol 2015, 867, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensalah, K.; Montorsi, F.; Shariat, S.F. Challenges of cancer biomarker profiling. Eur Urol 2007, 52, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, A.; Srinivasan, S.; Clements, J.; Batra, J. Beyond the biomarker role: prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in the prostate cancer microenvironment. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews 2019, 38, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Pu, H.; Liu, Q.; Guo, Z.; Luo, D. Circulating Tumor DNA-A Novel Biomarker of Tumor Progression and Its Favorable Detection Techniques. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jiang, F.; Xue, L.; Peng, C.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Pan, Y.; Wang, X.; Feng, C.; et al. Recent Progress in Biosensors for Detection of Tumor Biomarkers. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Li, P. Circulating nucleosomes as potential biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and treatment monitoring. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 262, 130005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moding, E.J.; Nabet, B.Y.; Alizadeh, A.A.; Diehn, M. Detecting Liquid Remnants of Solid Tumors: Circulating Tumor DNA Minimal Residual Disease. Cancer Discov 2021, 11, 2968–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Qu, X. Cancer biomarker detection: recent achievements and challenges. Chemical Society Reviews 2015, 44, 2963–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Wang, E. Cancer Biomarker Discovery for Precision Medicine: New Progress. Curr Med Chem 2019, 26, 7655–7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, G.A.; Ghosh, S.; Gamboa, L.; Patriotis, C.; Srivastava, S.; Bhatia, S.N. Synthetic biomarkers: a twenty-first century path to early cancer detection. Nat Rev Cancer 2021, 21, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chester, S.J.; Maimonis, P.; Vanzuiden, P.; Finklestein, M.; Bookout, J.; Vezeridis, M.P. A new radioimmunoassay detecting early stages of colon cancer: a comparison with CEA, AFP, and Ca 19-9. Dis Markers 1991, 9, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwong, G.A.; Ghosh, S.; Gamboa, L.; Patriotis, C.; Srivastava, S.; Bhatia, S.N. Synthetic biomarkers: a twenty-first century path to early cancer detection. Nature Reviews Cancer 2021, 21, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhao, S.; Karnad, A.; Freeman, J.W. The biology and role of CD44 in cancer progression: therapeutic implications. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2018, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodewijk, I.; Dueñas, M.; Paramio, J.M.; Rubio, C. CD44v6, STn & O-GD2: promising tumor associated antigens paving the way for new targeted cancer therapies. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1272681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, K.; Hackert, T.; Zöller, M. CD44/CD44v6 a Reliable Companion in Cancer-Initiating Cell Maintenance and Tumor Progression. Front Cell Dev Biol 2018, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orian-Rousseau, V.; Morrison, H.; Matzke, A.; Kastilan, T.; Pace, G.; Herrlich, P.; Ponta, H. Hepatocyte growth factor-induced Ras activation requires ERM proteins linked to both CD44v6 and F-actin. Mol Biol Cell 2007, 18, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Ohnishi, T.; Nishikawa, M.; Ohtsuka, Y.; Kusakabe, K.; Yano, H.; Tanaka, J.; Kunieda, T. A Narrative Review on CD44's Role in Glioblastoma Invasion, Proliferation, and Tumor Recurrence. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todaro, M.; Gaggianesi, M.; Catalano, V.; Benfante, A.; Iovino, F.; Biffoni, M.; Apuzzo, T.; Sperduti, I.; Volpe, S.; Cocorullo, G.; et al. CD44v6 is a marker of constitutive and reprogrammed cancer stem cells driving colon cancer metastasis. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Gross, W.; Zöller, M. CD44v6 coordinates tumor matrix-triggered motility and apoptosis resistance. The Journal of biological chemistry 2011, 286, 15862–15874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Adhikary, G.; Newland, J.J.; Xu, W.; Keillor, J.W.; Weber, D.J.; Eckert, R.L. Transglutaminase 2 Binds to the CD44v6 Cytoplasmic Domain to Stimulate CD44v6/ERK1/2 Signaling and Maintain an Aggressive Cancer Phenotype. Mol Cancer Res 2023, 21, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Dong, L.; Chang, P. CD44v6 engages in colorectal cancer progression. Cell Death & Disease 2019, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.L.; Song, L.N.; Deng, Z.F.; Chen, Y.; Ma, L.J. Prognostic value of CD44v6 expression in breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther 2018, 11, 5451–5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Xian, S.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, Y. CD44v6 may influence ovarian cancer cell invasion and migration by regulating the NF-κB pathway. Oncol Lett 2019, 18, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discovery 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.-D.; Ji, Y.; Liu, P.-F.; Xiang, B.; Chen, G.-Q.; Huang, B.; Wu, S. Correlation of E-cadherin and CD44v6 expression with clinical pathology in esophageal carcinoma. Mol Med Rep 2012, 5, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nozoe, T.; Kohnoe, S.; Ezaki, T.; Kabashima, A.; Maehara, Y. Significance of immunohistochemical over-expression of CD44v6 as an indicator of malignant potential in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2004, 130, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, J.; Yu, H.; Sun, P.; Hu, Y.; Zhong, J.; Zhu, Z. Expression and association of CD44v6 with prognosis in T2-3N0M0 esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Thorac Dis 2014, 6, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Luo, W.; Hu, R.T.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, S.Y.; Jiang, H.X. Meta-Analysis of Prognostic and Clinical Significance of CD44v6 in Esophageal Cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015, 94, e1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Ling, R.; Lai, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Kong, Y. CD44v6-mediated regulation of gastric cancer stem cells: a potential therapeutic target. Clin Exp Med 2025, 25, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).