1. Introduction

The global demographic shift toward population aging has profound implications for public health. One of the most pressing concerns is the growing prevalence of dementia and the associated psychological burden experienced by both patients and caregivers. Depression and anxiety are projected to increase alongside the demographic transition, with dementia representing a major driver of disability and dependency in later life. In 2019, it was estimated that the number of people living with dementia could reach 152.8 million by 2050, primarily due to increased life expectancy and demographic aging. More recent studies, however, have challenged these projections, noting potential underestimation of prevalence in minority populations such as Black and Hispanic groups [

1,

2], while others argue that lifestyle interventions may contribute to a decline in incidence over time [

3,

4]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 57 million people were living with dementia in 2021, with 10 million new cases diagnosed each year, reflecting a constantly rising global burden [

5].

Dementia prevalence increases exponentially with age, doubling every five years after age 65 [

6]. The condition is particularly prevalent in aging societies such as Japan, Italy and Germany [

7], with Alzheimer’s disease ranked as the most common neurodegenerative disorder worldwide, followed by Parkinson’s disease [

6,

8,

9]. Between 2021 and 2023, WHO reports identified Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias among the top three causes of death in Great Britain [

10]. Pathophysiologically, dementia involves progressive neuronal degeneration, hippocampal and cortical atrophy, synaptic loss and the accumulation of neurotoxic proteins including amyloid-β plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles [

11,

12,

13,

14]. These changes lead to cognitive decline, behavioral alterations and loss of independence, making dementia the leading cause of disability and death among neurological conditions [

15].

Dementia caregiving entails profound emotional, physical and social challenges. A large European survey in 2006 reported that one-third of caregivers provided more than 10 hours of daily care, regardless of dementia severity [

16]. More recently, a study of over 1,400 caregivers across five European countries revealed that nearly 20% received no information at diagnosis, 58% expressed persistent worry about the future, 34% reported depressive symptoms and many described loneliness as a major consequence of their role [

17].

Consistently, caregivers of individuals with dementia experience greater psychological distress than caregivers of other chronic conditions [

18,

19]. A meta-analysis demonstrated that dementia family caregivers are significantly more stressed and report more depressive symptoms and physical problems compared to other caregivers [

20]. Risk factors for heightened distress include demographic variables (female gender, older age, spouse or child relationship to the care recipient), lower socioeconomic status and limited social support [

21,

22,

23,

24]. The severity of the care recipient’s cognitive impairment, often measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), has also been shown to correlate directly with caregiver burden [

25].

Beyond distress, research has increasingly focused on the psychological well-being of caregivers, assessed across multiple domains such as autonomy, self-acceptance, personal growth and purpose in life using Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale [

26,

27,

28]. Evidence suggests that well-being often declines as caregiving responsibilities intensify. For example, Wister et al. (2022) found that caregivers with lower well-being scores were more likely to develop depressive and anxiety symptoms, highlighting the importance of multidimensional assessments [

29]. Coping strategies are equally critical; caregivers who adopt adaptive strategies such as seeking social support or maintaining personal control exhibit better mental health outcomes, whereas reliance on maladaptive coping predicts poorer outcomes [

30,

31].

Depression and anxiety are the two most prevalent mental health concerns among caregivers. According to Pinquart and Sörensen (2007), caregivers consistently report higher levels of depression than non-caregivers, with the gap being most pronounced among those caring for dementia patients [

32]. Depression in caregivers is exacerbated by lack of social support, physical exhaustion and isolation [

33], while anxiety often stems from uncertainty about the future, financial strain and the overwhelming nature of caregiving responsibilities.

Existing research demonstrates that dementia caregiving is associated with profound psychological challenges, but also that individual, relational and socio-economic resources can shape outcomes. However, most studies treat caregivers as a homogeneous group, overlooking the possibility of latent subgroups that differ in their levels of depression, anxiety and well-being. Identifying such profiles is essential for developing tailored interventions. Moreover, socio-economic resources such as education and income may function as resilience factors that buffer against psychological burden, though evidence remains limited.

However, despite substantial variability in caregiver experiences, few studies have empirically tested whether distinct subgroups (profiles) of caregivers can be identified based on co-occurring depressive and anxiety symptoms. Moreover, prior work rarely integrates psychological well-being into such subgroup analyses, and virtually no studies have examined whether socioeconomic factors moderate these associations. Addressing these gaps requires analytic approaches capable of detecting latent heterogeneity, such as Latent Profile Analysis (LPA), while also acknowledging that the number of identifiable profiles is constrained by sample size and may be limited to a small number of broad caregiver groups.

In this context, the present study proposes three exploratory hypotheses: (H1) caregivers will cluster into a small number of latent psychological profiles defined by different combinations of depression and anxiety; (H2) these profiles will show meaningful differences in psychological well-being; and (H3) higher education and income will be associated with attenuated negative relationships between affective symptoms and well-being.

To fill these gaps, the study applies Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) to depressive and anxiety symptoms among family caregivers of dementia patients, following three objectives: identifying distinct psychological profiles of caregivers, examining their associations with dimensions of psychological well-being and exploring whether education and income act as protective moderators.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a single-center, observational, analytical cross-sectional study conducted in the Neurology–Psychiatry Department of the C.F.2 Clinical Hospital (Bucharest, Romania). During the six-month recruitment period (November 2023–April 2024), 120 informal caregivers sought dementia-related services and were screened for eligibility; 73 caregivers met inclusion criteria and were enrolled. Eligibility required participants to be ≥30 years old, a family member of the person with dementia, to have provided care for at least six months and to be actively involved in caregiving at the time of recruitment. Non-family caregivers and individuals with incomplete questionnaire data were excluded. No financial incentives were provided.

Because the sample includes all caregivers who met criteria during this interval rather than a probabilistic sample, the study does not aim for population representativeness and is interpreted as exploratory..

Data collection employed a battery of instruments, chosen to capture both psychological outcomes and relevant contextual factors. These included Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scales (54 items), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), the COVI Anxiety Scale, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; extracted from medical records) and an Anthropological Questionnaire (AQ) specifically developed for this study to gather socio-demographic information. All data were collected in person at the physician’s office. Caregivers completed the self-administered questionnaires on-site, with a researcher available for clarification. The assessment required approximately 45 minutes. Participants were informed that participation was voluntary and would not affect their or their relatives’ access to medical care.

Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scales (Romanian adaptation) [

26,

27,

34] were used to evaluate caregivers’ positive psychological functioning. The instrument consists of six conceptually established dimensions: autonomy, personal growth, positive relations, self-acceptance, purpose in life and environmental mastery. Each dimension is assessed using nine distinct items. Responses are rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, with 28 items reverse-coded to control for acquiescence bias. Subscales can be analyzed separately, but they can also be aggregated into a higher-order well-being index. Previous studies have demonstrated the reliability, factorial validity and cross-cultural robustness of this measure, including in Romanian populations [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach’s α) for the present sample were calculated and reported in the Results section

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). This widely used self-report measure is aligned with DSM-IV and DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for major depression. Scores are interpreted according to established clinical cut-offs: 5–9 = mild, 10–14 = moderate, 15–19 = moderately severe and 20–27 = severe depression. The PHQ-9 has been extensively validated in both clinical and community samples, consistently demonstrating strong psychometric properties [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. In Romania, several validation studies have confirmed its reliability and screening utility across diverse patient groups [

44].

Anxiety was evaluated using the COVI Anxiety Scale, a clinician-rated instrument designed to quantify the severity of anxiety symptoms. The scale categorizes scores into four severity levels: 3–5 = minimal or no anxiety, 6–8 = mild anxiety, 9–11 = moderate anxiety and 12–15 = severe anxiety. The COVI scale is recognized in both research and practice as a brief yet sensitive tool for the assessment of anxiety and it is frequently employed to guide treatment planning and targeted interventions [

45].

Cognitive functioning of the care recipients was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). This 30-item screening tool evaluates orientation, attention, memory and language abilities, yielding a total score between 0 and 30, with lower scores indicating greater cognitive impairment. A threshold of 24 or below is commonly used to suggest the presence of clinically significant impairment. In this study, MMSE scores were extracted directly from patients’ medical records under institutional ethics approval. Because the data were de-identified, separate patient consent was not required. The MMSE is one of the most extensively validated instruments in geriatric and neurocognitive assessment and remains a gold standard in the field [

46,

47,

48]. Because MMSE scores were recorded at diagnosis rather than concurrently with caregiver data collection, this temporal mismatch is acknowledged as a methodological limitation.

The Ryff scales, PHQ-9 and the AQ were self-administered by participants in a private setting within the physician’s office at C.F.2 Clinical Hospital. In contrast, the COVI Anxiety Scale was clinician-rated by the attending psychiatrist. On average, the full assessment procedure required approximately 45 minutes per participant. To ensure clarity and appropriateness of the socio-demographic instrument (AQ), a pilot test was conducted with 15 formal caregivers; their feedback was carefully reviewed and integrated into the final version of the questionnaire. Given the multidomain structure of the Anthropological Questionnaire (AQ), internal consistency was assessed only for conceptually coherent subsets representing behavioral and functional characteristics of the care recipients. For these subsets, Cronbach’s α values generally exceeded thresholds considered acceptable for exploratory research (α ≥ 0.60) (eg.Appetite/Eating domain showed α = 0.69, Current Activity α = 0.73 and Alternative Beliefs α = 0.75.

In contrast, AQ components referring to caregiver sociodemographic information (e.g., age, education, income, living arrangements) were not evaluated using internal consistency metrics because such variables do not represent latent constructs and are not expected to correlate. Accordingly, internal consistency analysis was limited to those AQ domains that conceptually functioned as scales rather than categorical descriptors. All AQ-derived indices were used descriptively, consistent with the instrument’s qualitative–anthropological grounding and the exploratory aims of the study.

All procedures adhered to established ethical standards for research involving human participants. Written informed consent was obtained from all caregivers prior to their participation in the study. Only caregivers were required to sign consent forms, as data regarding the cognitive status of care recipients (MMSE scores) were retrieved exclusively from medical records. These data were used in a fully de-identified format, thereby ensuring participant confidentiality and eliminating the need for separate patient consent.

The overall study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of C.F.2 Clinical Hospital (Reference No. 1781/06.02.2023) and data collection commenced only after ethics approval had been granted.

To further safeguard ethical compliance, participants were informed about the purpose, procedures, potential risks and benefits of the study and were assured that their participation was entirely voluntary and could be withdrawn at any point without affecting their or their relatives’ access to medical care. Data were stored and analyzed in aggregate form only, thereby preventing the identification of individual participants.

Statistical analyses were performed to explore latent heterogeneity in caregivers’ affective symptomatology and to examine its associations with psychological well-being. Prior to modeling, all continuous variables were standardized (z-scores) to place them on a comparable metric and reduce scale-related biases.

To identify distinct caregiver subgroups, a Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) was con-ducted using depressive symptoms (PHQ-9) and anxiety severity (COVI) as indicators. Competing models specifying one to five latent profiles were estimated. Model adequacy was evaluated primarily using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), with the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) considered secondarily. Model selection additionally considered conceptual interpretability, profile distinctiveness, adequacy of class sizes, and convergence stability.

After establishing the optimal latent profile solution, group differences across profiles were examined using one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) for PHQ-9 and COVI scores, followed by Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) tests for pairwise comparisons. Effect sizes (η²) were calculated to quantify the magnitude of the observed differences. This approach allowed for a direct comparison of symptom severity across the emergent caregiver subgroups.

Associations between affective symptomatology (PHQ-9, COVI) and Ryff’s six psychological well-being dimensions were examined using Pearson correlation coefficients. These analyses assessed whether higher depressive or anxiety symptoms were systematically related to lower well-being across specific domains. Correlation analyses were selected to reflect the exploratory nature of the study and to capture broad relational patterns among variables.

Descriptive statistics for each latent profile are presented in tabular form, along-side graphical summaries illustrating profile-specific mean scores and score distribu-tions. These visual and numerical summaries provided a comprehensive overview of within- and between-profile variability.

Finally, to evaluate the potential protective role of socio-economic resources, moderation analyses were conducted with caregivers’ education level and household income. These analyses tested whether higher education or income buffered the nega-tive associations between depressive or anxiety symptoms and psychological well-being. Moderation was examined to determine whether socio-economic resources influence the strength of the relationship between psychological distress and well-being..

3. Results

A total of 73 family caregivers met the inclusion criteria and completed the study protocol. The majority of participants were women (75.3%), a distribution consistent with the well-documented gendered patterns of caregiving in dementia. Caregivers’ ages ranged from 34 to 78 years, with a mean age of 57.1 years (SD = 10.4), indicating that most participants were middle-aged or older adults, a demographic commonly involved in long-term family caregiving. Educational backgrounds were heterogeneous, spanning secondary to higher education, while household income varied considerably, suggesting substantial diversity in socio-economic resources within the sample. Most caregivers resided in urban areas, although a notable proportion came from rural settings, thereby reflecting the mixed socio-demographic composition of the catchment area of the C.F.2 Clinical Hospital.

Regarding their caregiving role, all participants were close family relatives of the care recipients, most frequently adult children or spouses. The minimum caregiving duration was six months; however, many caregivers had been providing support for several years, underscoring the chronic and demanding nature of dementia care in this population.

With respect to the cognitive functioning of the patients, as measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), most were documented as presenting moderate to severe impairment, a pattern aligned with the advanced clinical stages at which families typically seek specialized neurological and psychiatric services. These contextual characteristics—marked by high caregiving intensity, prolonged duration, and substantial cognitive decline in care recipients—underscore the significant emotional, cognitive and practical demands placed upon family caregivers in the present study.

To identify subgroups of caregivers based on affective symptomatology, a latent profile analysis (LPA) was conducted on standardized PHQ-9 (depression) and COVI (anxiety) scores. Models specifying one to five latent profiles were estimated using Gaussian finite mixture modeling with an EII covariance structure. Model fit indices (AIC, BIC, SABIC) are presented in

Table 1.

All fit criteria consistently favored the three-profile solution, which exhibited the lowest BIC (886.91), AIC (818.20) and SABIC (792.38). Accordingly, the three-profile model was retained as the optimal and most parsimonious representation of latent heterogeneity in caregivers’ affective symptoms.

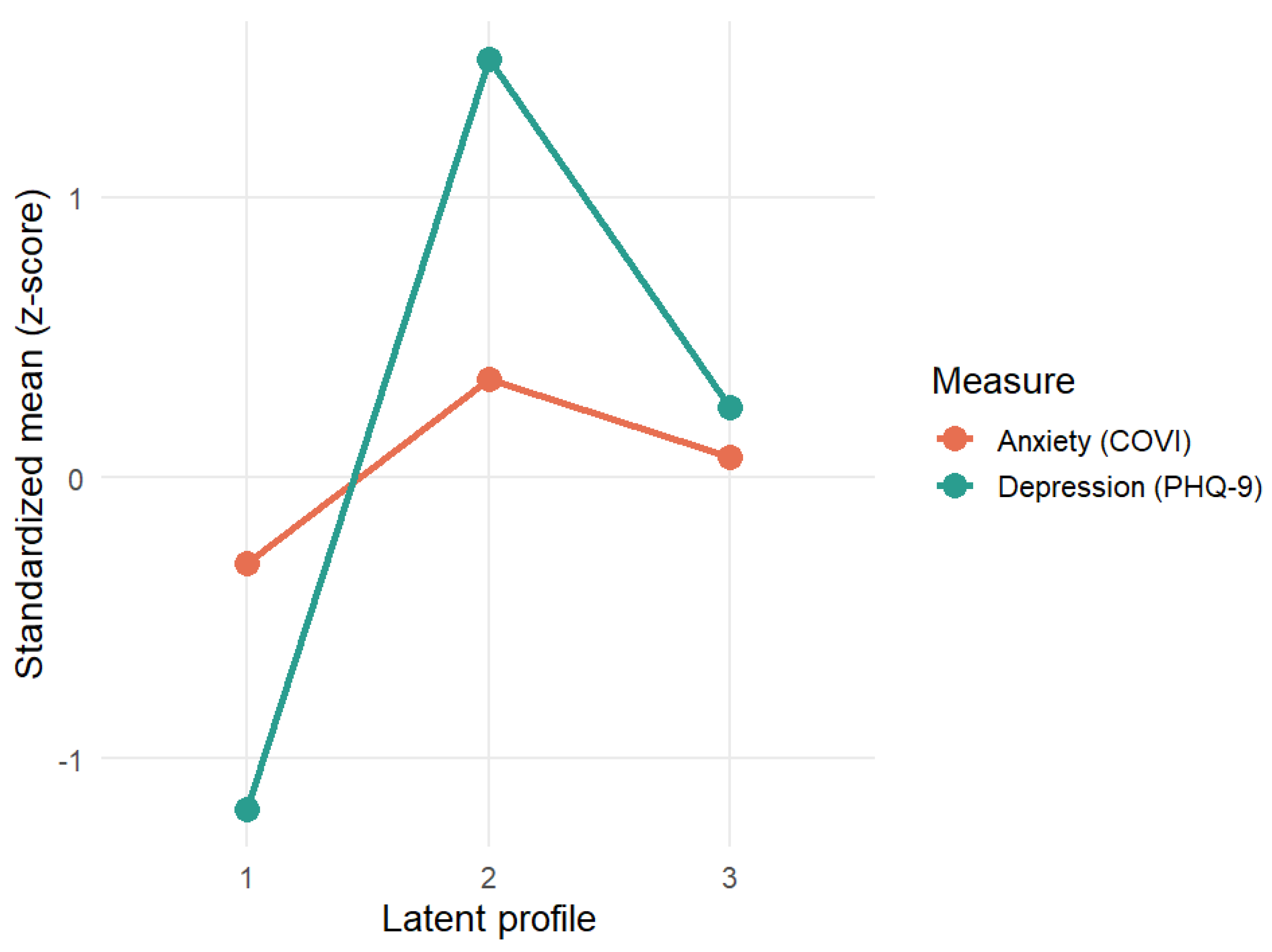

The first profile (n = 24; 32.9%) was characterized by moderate depressive symptoms and moderate anxiety (PHQ-9: M = 11.50; COVI: M = 11.46), representing the subgroup with the lowest overall distress, though mean scores still exceeded typical clinical thresholds. The second profile (n = 36; 49.3%) encompassed caregivers with moderately severe depression accompanied by severe anxiety (PHQ-9: M = 19.72; COVI: M = 12.31) and constituted nearly half of the sample. The third and smallest profile (n = 13; 17.8%) exhibited the most elevated symptomatology, marked by severe depressive symptoms and severe anxiety (PHQ-9: M = 26.85; COVI: M = 12.92), and thus reflects the most psychologically vulnerable subgroup. (

Table 2).

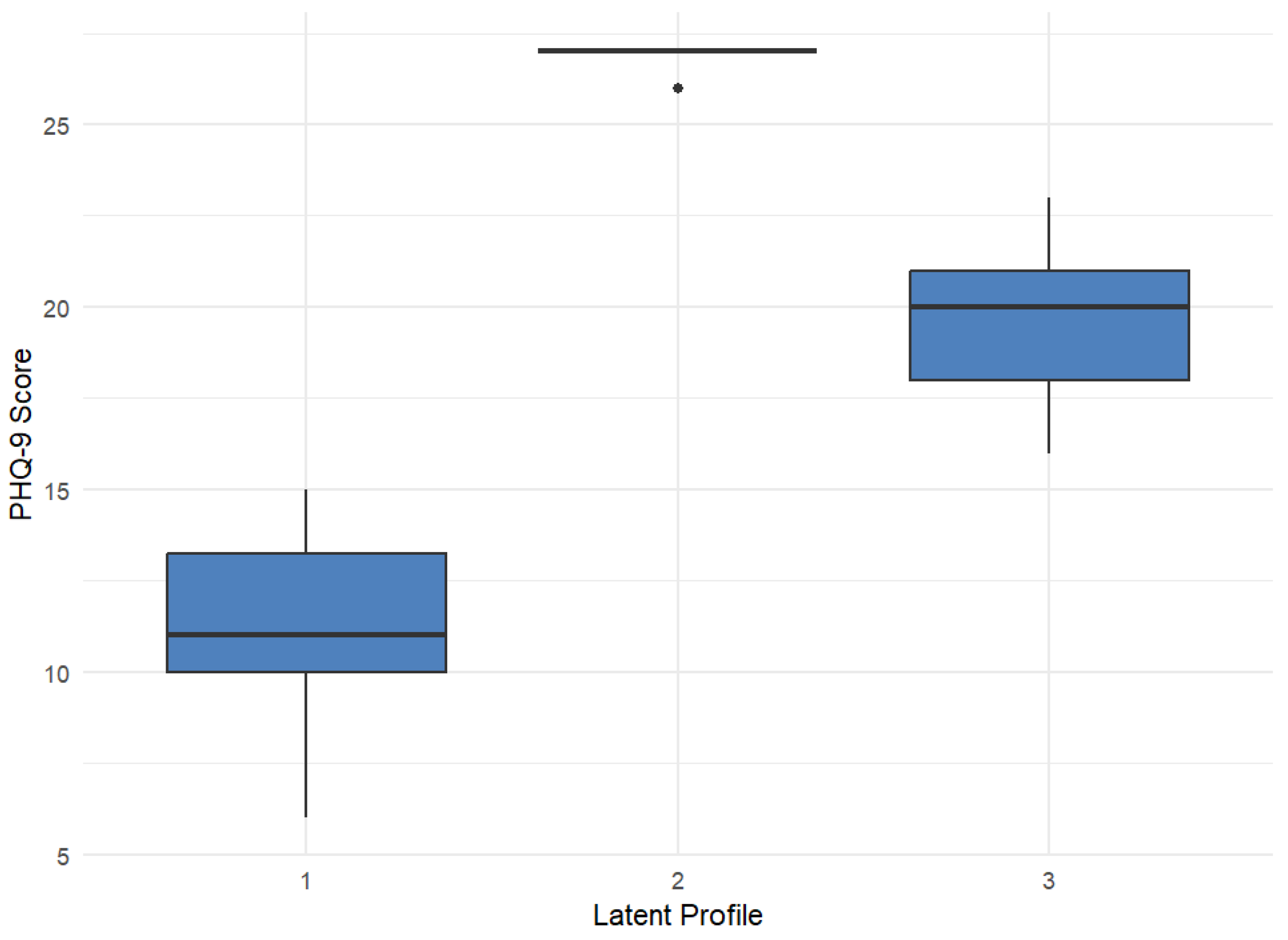

Group differences across the latent profiles were examined using one-way ANOVAs. For depressive symptoms (PHQ-9), the omnibus test indicated a highly significant and substantial effect, F(2, 70) = 307.20, p < .001, η² = .90, suggesting that profile membership accounts for a very large proportion of variance in depressive severity. Post hoc Tukey comparisons showed that all three profiles differed significantly from one another, with Profile 2 exhibiting the highest depressive symptoms, Profile 3 showing intermediate levels, and Profile 1 the lowest.

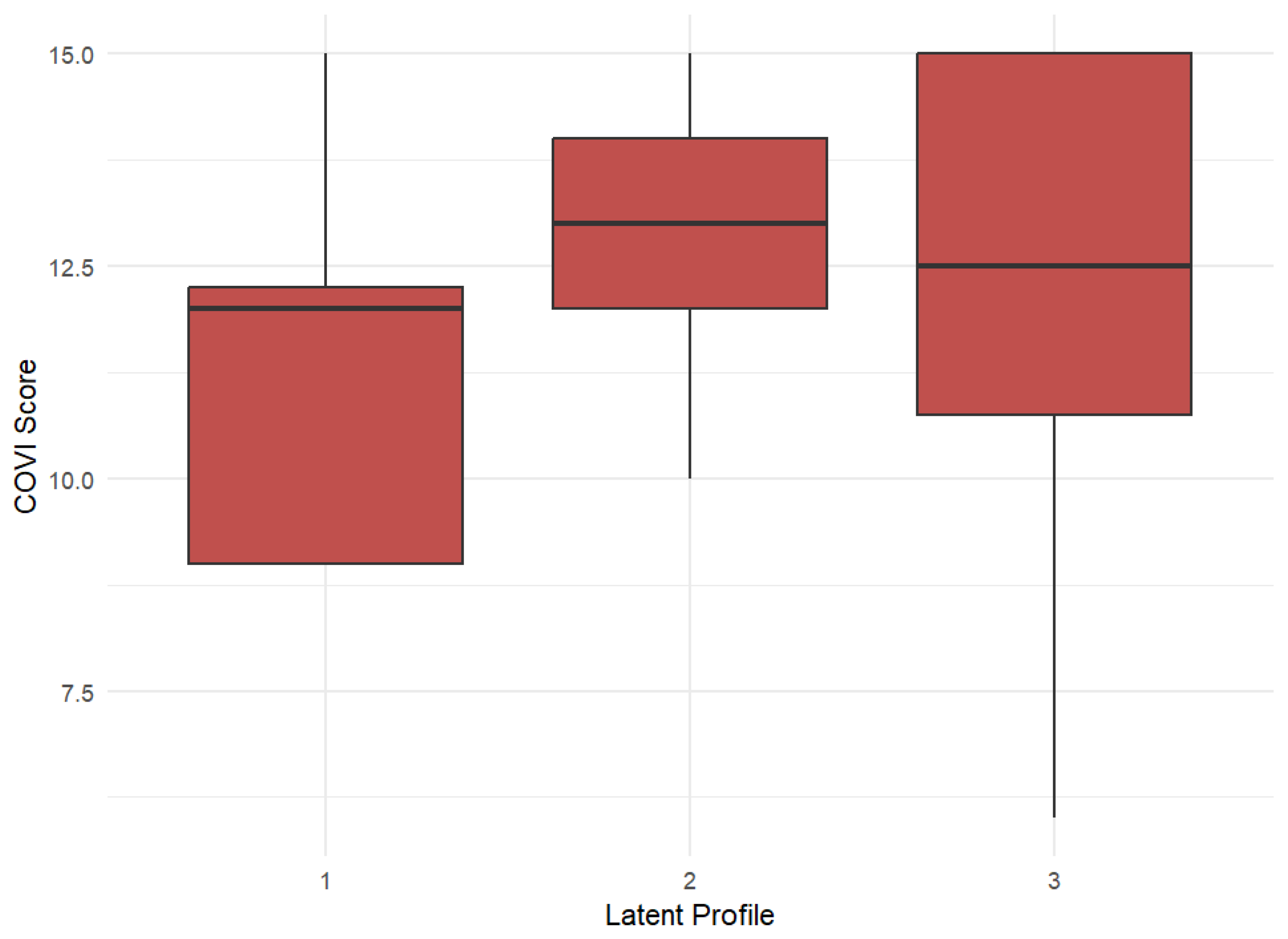

In contrast, anxiety severity (COVI) showed no statistically significant differences across profiles, F(2, 70) = 2.09, p = .131, η² = .06, indicating only a small and non-significant effect. Although descriptive means suggested a trend toward elevated anxiety in Profile 3 and lower anxiety in Profile 1, these differences did not reach statistical significance after correcting for multiple comparisons.

Boxplots illustrating the distribution of PHQ-9 and COVI scores across profiles are presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, respectively, and standardized mean symptom patterns for each latent profile are shown in

Figure 3, providing a visual summary of the magnitude and direction of between-profile differences..

Between-profile comparisons for the six Ryff psychological well-being dimensions indicated that several aspects of well-being differed significantly across the three latent profiles identified through LPA. The most pronounced difference was observed for purpose in life, where the omnibus ANOVA was significant, F(2, 70) = 4.53, p = .014, η² = .115, showing that caregivers belonging to different latent profiles reported meaningfully different levels of purpose in life. A similar pattern emerged for self-acceptance, F(2, 70) = 3.90, p = .025, η² = .100, again indicating systematic variation across profiles. Differences in personal growth approached significance, F(2, 70) = 2.93, p = .060, η² = .077, suggesting a possible but not statistically confirmed profile-related effect. In contrast, positive relations, environmental mastery, and autonomy did not vary significantly across the three profiles (all p > .15), indicating that these dimensions were comparatively stable regardless of caregivers’ latent class membership.

Pearson correlations further clarified the associations between affective symptomatology and well-being. Higher depressive symptoms (PHQ-9) were weakly but significantly associated with lower self-acceptance (r = .25, p = .033) and lower autonomy (r = .24, p = .044). No other correlations between depression and well-being were significant (all p > .16). Anxiety severity (COVI) showed no significant associations with any of the well-being dimensions (all p > .21), suggesting that variation in psychological well-being was more closely related to depressive symptoms than to anxiety levels in this sample.

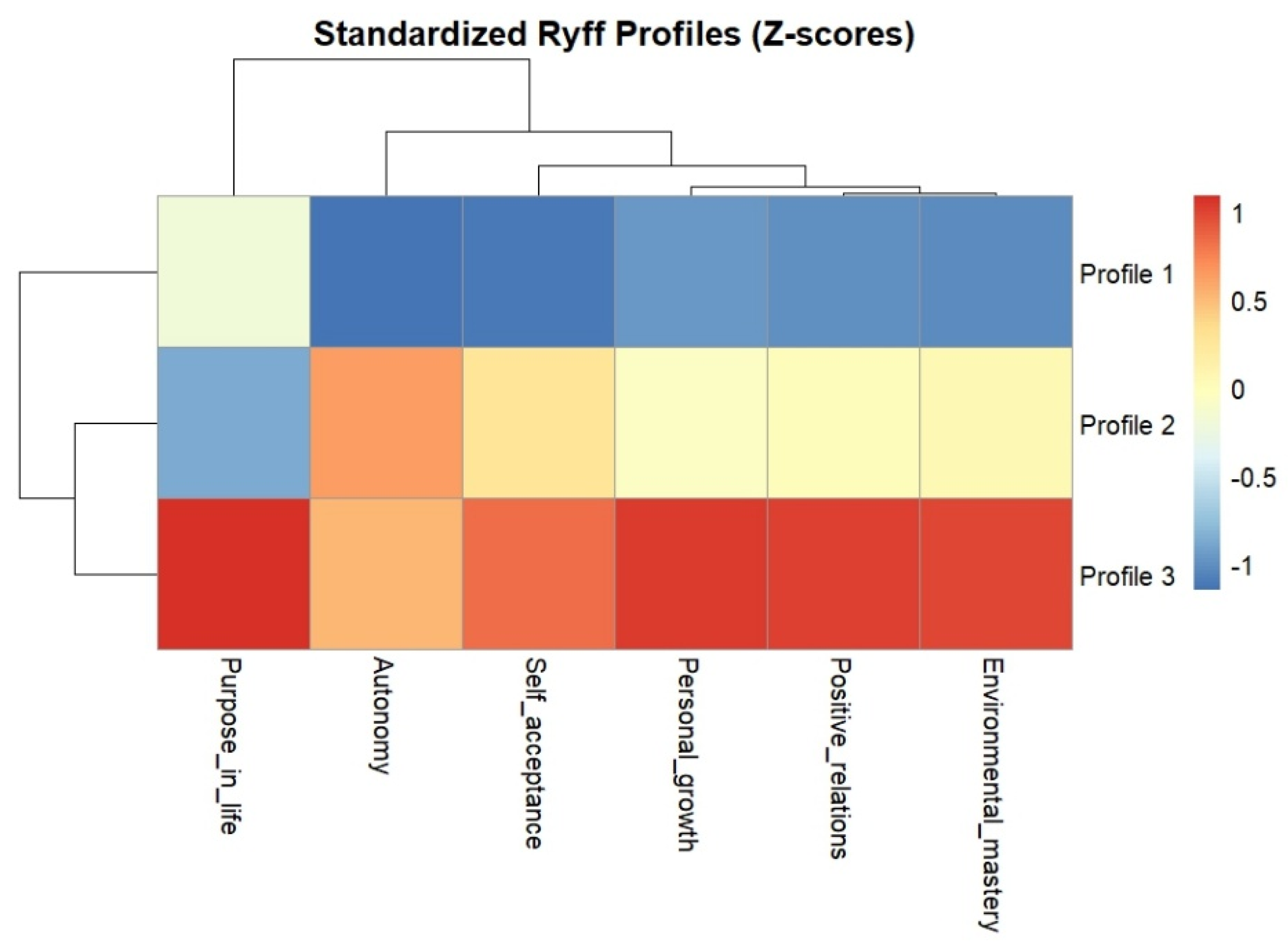

To visualize the multivariate pattern of psychological well-being across profiles, a standardized (z-score) heatmap was generated for the six Ryff dimensions (

Figure 4). The heatmap revealed a clear gradient of well-being across latent profiles. Profile 1 showed consistently negative z-scores across all Ryff domains, indicating lower-than-average well-being. Profile 2 displayed values near the sample mean, whereas Profile 3 demonstrated uniformly elevated scores, with positive deviations across all dimensions.

This pattern shows that Profile 3 exhibited the highest overall well-being, despite presenting moderately severe affective symptoms. Conversely, Profile 1 showed the lowest well-being levels, even though its depressive and anxiety symptoms were the mildest among the three profiles. Thus, the heatmap corroborates the ANOVA and post-hoc findings, highlighting that well-being does not follow a strictly linear relationship with symptom severity.

To evaluate whether global psychological well-being differed between the three latent profiles, an ANOVA was conducted using the composite Ryff_total score. The omnibus test approached but did not reach statistical significance, F(2, 70) = 3.06, p = .053, η² = .08, indicating a trend toward higher well-being in profiles with lower affective symptom severity.

Mean well-being scores increased progressively across the three profiles (

Table 3). Post-hoc Tukey tests revealed a significant difference between Profile 3 and Profile 1 (p = .043), with caregivers in Profile 3 reporting higher overall well-being. Differences between Profiles 2 and 1 and between Profiles 3 and 2 were not statistically significant (all p > .52) (

Table 4).

Based on the mean symptom scores, Profile 1 represented the lowest affective symptom group, whereas Profiles 2 and 3 reflected increasingly severe levels of depression and anxiety. Despite this pattern, caregivers in Profile 3 reported significantly higher overall psychological well-being compared with those in Profile 1. This unexpected result suggests that well-being in this sample does not vary strictly as a linear function of symptom severity. Instead, caregivers in Profile 3—although experiencing moderately severe symptoms—may possess compensatory psychological or contextual resources (e.g., coping strategies, social support, meaning-making) that help maintain higher well-being. No other pairwise comparisons were statistically significant.

To examine whether the three latent profiles differed in socio-economic characteris-tics, caregivers’ education level and monthly household income were compared across profiles (

Table 5). Education levels were distributed relatively evenly among the three groups: Profile 1 included roughly equal proportions of caregivers with high school and higher education, Profile 2 showed a similar pattern with slightly more individuals in the secondary education category, and Profile 3 presented the highest proportion of caregivers with high school education. Fisher’s exact test indicated that these distributions did not differ significantly across profiles.

A similar pattern emerged for household income. Profile 1 and Profile 2 were comparable in their concentration of caregivers within the middle-income range (400–1000 EUR), whereas Profile 3 showed a somewhat higher proportion of caregivers with lower income (up to 400 EUR) and a moderately higher proportion reporting incomes above 1000 EUR. Despite these descriptive contrasts, the association between income and profile membership did not reach statistical significance.

Table 5.

Distribution of education level and household income across the three latent profiles (%).

Table 5.

Distribution of education level and household income across the three latent profiles (%).

| Profile |

Secondary |

High school |

Higher education |

Up to 400 EUR |

400–1000 EUR |

Over 1000 EUR |

| 1 |

8.3% |

50.0% |

41.7% |

8.3% |

79.2% |

12.5% |

| 2 |

15.4% |

46.2% |

38.5% |

7.7% |

84.6% |

7.7% |

| 3 |

2.8% |

61.1% |

36.1% |

30.6% |

50.0% |

19.4% |

| Test statistics |

Education: χ²(4) = 2.99, p = .56; Fisher’s p = .514 |

Income: χ²(4) = 8.55, p = .073; Fisher’s p = .085 |

Taken together, the results indicate that the three latent profiles identified through LPA reflect meaningful variation in caregivers’ affective symptomatology, with implications for their psychological well-being but not for their socio-economic positioning. While education and household income did not differ significantly across profiles—indicating that depressive and anxiety symptom patterns cut across demographic and economic strata—clear differences emerged in psychological functioning. Caregivers in Profile 3, characterized by the lowest affective symptom levels, reported significantly higher overall well-being than those in Profile 1, whereas other pairwise contrasts were nonsignificant. These findings suggest that emotional distress is a primary differentiator of caregiver functioning in this sample, with higher symptomatology associated with diminished well-being, independently of socio-economic resources.

4. Discussion

The present study identified three distinct psychological profiles among family caregivers of individuals with dementia, based on depressive and anxiety symptoms. These profiles reflected meaningful heterogeneity in caregivers’ emotional adjustment rather than differences driven primarily by demographic or socio-economic characteristics. This pattern is consistent with previous work showing substantial variability in caregiver burden and psychological responses, even within apparently similar caregiving contexts (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003; Brodaty & Donkin, 2009).

The three profiles captured qualitatively different configurations of affective symptoms. One group (Profile 1) showed the lowest levels of depressive symptoms combined with moderate anxiety, another group (Profile 3) presented moderately severe depressive symptoms and elevated anxiety, and a third group (Profile 2) was characterized by severe depression and severe anxiety. These clusters underscore that depressive and anxiety symptoms do not simply increase along a single continuum but instead tend to co-occur in specific patterns that reflect different emotional responses and coping demands in the caregiving role (Cejalvo et al., 2021; Wister et al., 2022).

Differences in affective symptomatology were mirrored, though not perfectly, in caregivers’ psychological well-being. The Ryff dimensions of purpose in life and self-acceptance showed the clearest variation across profiles, with more distressed profiles generally reporting lower scores. At the level of the composite well-being index (Ryff_total), the omnibus effect only approached statistical significance, yet post-hoc analyses revealed meaningful contrasts between profiles. In particular, caregivers in Profile 3 reported higher overall well-being than those in Profile 1, despite exhibiting more pronounced depressive and anxiety symptoms. This counterintuitive pattern challenges simple linear models linking symptom severity directly to psychological well-being and suggests that affective symptoms and well-being are not merely opposite poles of a single dimension.

Although Profile 1 exhibited the lowest levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms, its well-being scores were lower than those of Profile 3. One possible interpretation is that caregivers in Profile 3, despite their elevated symptoms, may rely on more adaptive coping mechanisms, greater emotional engagement, or a stronger perceived sense of purpose in caregiving—factors frequently described as protective or resilience-enhancing in the caregiver literature (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2007; Wister et al., 2022). Conversely, caregivers in Profile 1 may experience lower well-being due to factors not captured directly in our affective indicators, such as caregiver fatigue, family conflict, or role overload, which can erode well-being even in the presence of relatively mild depressive and anxiety symptoms. In this sense, well-being appears to depend not only on symptom levels but also on broader psychological and contextual resources.

The heatmap of standardized Ryff scores reinforced this interpretation by showing that caregivers in Profile 3—though moderately symptomatic—displayed the highest psychological well-being across all Ryff dimensions, whereas Profile 1 consistently scored lower. This pattern suggests the presence of compensatory or resilience-related processes (e.g., meaning in caregiving, perceived competence, social support) that may buffer the impact of affective symptoms on well-being in some caregivers. In contrast, the comparatively low well-being observed in Profile 1, despite the lowest symptom scores, indicates that reduced affective symptoms alone do not guarantee psychological flourishing. Taken together, these findings support a multidimensional view in which caregiver well-being is shaped by the interplay between emotional distress and protective psychological resources rather than by symptom severity in isolation (Tatomirescu and al, 2025).

Correlation analyses provided convergent but more fine-grained evidence. Depressive symptoms were weakly yet consistently associated with lower self-acceptance and autonomy, two central components of psychological well-being that reflect how caregivers evaluate themselves and their perceived capacity to manage life demands. This pattern aligns with prior studies showing that depression in caregivers is particularly detrimental to self-worth, perceived control, and adaptive functioning (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2007; Wister et al., 2022). In contrast, anxiety severity showed no meaningful associations with any of the Ryff dimensions, suggesting that in this sample anxiety may have been more contextually fluctuating and less tightly coupled with global well-being than depressive symptomatology.

Socio-economic characteristics—namely education level and household income—did not differ significantly across profiles and did not moderate the associations between affective symptoms and well-being. Although one profile showed a somewhat higher proportion of caregivers with lower income, this tendency was not statistically robust. These findings are in line with previous evidence indicating that, while socio-economic factors can shape access to services and long-term care arrangements, emotional strain and psychological distress in dementia caregiving often cut across socio-economic strata (Brodaty & Donkin, 2009; Cejalvo et al., 2021). In the present study, psychological burden and well-being appeared to be more strongly linked to affective configurations and psychological resources than to educational attainment or financial status.

Overall, the identification of three distinct profiles underscores the importance of assessing both depression and anxiety simultaneously and of considering their combined expression when evaluating caregiver mental health. The findings point to specific subgroups—particularly caregivers with high co-occurring depressive and anxiety symptoms—for whom targeted interventions may be especially warranted. At the same time, the unexpected advantage in well-being observed in Profile 3 relative to the least symptomatic group highlights the potential role of resilience-related processes and suggests that interventions aiming to strengthen meaning, self-acceptance, and autonomy may be beneficial even when symptomatic relief is only partial. In sum, the present study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of caregiver adjustment in dementia, emphasizing that psychological well-being reflects not only the presence or absence of distress but also the capacity to mobilize personal and contextual resources in the face of ongoing caregiving demands.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that family caregivers of individuals with dementia can be meaningfully grouped into three distinct psychological profiles, characterized by different constellations of depressive and anxiety symptoms. These heterogeneous affective patterns highlight that caregiver distress does not follow a simple severity gradient but forms qualitatively different profiles, each with unique implications for psychological well-being. Such variability underscores the importance of individualized screening and tailored support strategies in caregiver interventions. Enhancing caregiver mental health is essential not only for improving their own well-being but also for sustaining the quality and continuity of care provided to persons living with dementia.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the single-center, cross-sectional design limits the generalizability of the findings and does not permit conclusions regarding causality or the temporal stability of the identified profiles. Second, although adequate for exploratory latent profile analysis, the sample size was modest, which may have reduced statistical power, particularly for detecting small-to-moderate differences in psychological well-being across profiles. Third, the study relied on self-report measures for caregivers and retrospective MMSE scores for patients; despite the strong psychometric properties of these instruments, reporting biases and temporal mismatch cannot be fully excluded. Moreover, the study did not directly assess potentially relevant psychological or contextual variables—such as coping strategies, perceived meaning in caregiving, resilience, or social support—that may help explain why some caregivers maintain higher well-being despite elevated symptoms.

Future research should aim to replicate these findings in larger and more diverse, multi-center samples, enabling more stable estimation of latent profiles. Longitudinal designs are needed to examine transitions between profiles over time and to clarify whether specific symptom configurations predict future changes in well-being or caregiving outcomes. Further work should also incorporate additional psychological and contextual factors to better understand the mechanisms underlying differences in well-being among caregivers and to identify targets for tailored intervention strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T.; formal analysis, C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T.; investigation, L.F.T.; methodology, C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T.; software, C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T.; supervision, C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T.; validation C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T.; writing—original draft, C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T.; writing—review and editing, C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of C.F.2 Clinical Hospital (Ref. Number: 1781; and the approval date is 6 February 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nichols, E.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Vollset, S.E.; Fukutaki, K.; Chalek, J.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdoli, A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Akram, T.T.; et al. Estimation of the Global Prevalence of Dementia in 2019 and Forecasted Prevalence in 2050: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2024 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 3708–3821. [CrossRef]

- Stallard, P.J.E.; Ukraintseva, S.V.; Doraiswamy, P.M. Changing Story of the Dementia Epidemic. JAMA 2025, 333, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukadam, N.; Wolters, F.J.; Walsh, S.; Wallace, L.; Brayne, C.; Matthews, F.E.; Sacuiu, S.; Skoog, I.; Seshadri, S.; Beiser, A.; et al. Changes in Prevalence and Incidence of Dementia and Risk Factors for Dementia: An Analysis from Cohort Studies. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e443–e460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Licher, S.; Darweesh, S.K.L.; Wolters, F.J.; Fani, L.; Heshmatollah, A.; Mutlu, U.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Heeringa, J.; Leening, M.J.G.; Ikram, M.K.; et al. Lifetime Risk of Common Neurological Diseases in the Elderly Population. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2019, 90, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators; Health at a Glance; OECD: Paris, France, 2023; ISBN 978-92-64-95793-0. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Sherer, T.; Okun, M.S.; Bloem, B.R. The Emerging Evidence of the Parkinson Pandemic. J. Park. Dis. 2018, 8, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furdu-Lunguț, E.; Antal, C.; Turcu, S.; Costea, D.-G.; Mitran, M.; Mitran, L.; Diaconescu, A.-S.; Novac, M.-B.; Gorecki, G.-P. Study on Pharmacological Treatment of Impulse Control Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Available online: https://data.who.int/countries/826 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Ye, J.; Wan, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, G.-P. Targeting Tau in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Mechanisms to Clinical Therapy. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 19, 1489–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, M.; Dawson, H.N.; Binder, L.I.; Vitek, M.P.; Ferreira, A. Tau Is Essential to β-Amyloid-Induced Neurotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 6364–6369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.; Selkoe, D.J. The Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Progress and Problems on the Road to Therapeutics. Science 2002, 297, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a Biological Definition of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georges, J.; Jansen, S.; Jackson, J.; Meyrieux, A.; Sadowska, A.; Selmes, M. Alzheimer’s Disease in Real Life—The Dementia Carer’s Survey. Int. J. Geriat. Psychiatry 2008, 23, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer Europe. 2006 Alzheimer Europe Survey: Who Cares? The State of Dementia Care in Europe; Alzheimer Europe: Lux-embourg, 2006; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer Europe. European Carers’ Report 2018: Carers’ Experiences of Diagnosis in Five European Countries; Alzheimer Europe: Luxembourg, 2018; ISBN 978-999959-995-2-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart, M.; Sörensen, S. Differences between Caregivers and Noncaregivers in Psychological Health and Physical Health: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Aging 2003, 18, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhalim, D.S.; Ahmed, M.M.; Hussein, H.A.; Khalaf, O.O.; Sarhan, M.D. Burden of Care, Depression and Anxiety Among Family Caregivers of People with Dementia. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2024, 15, 21501319241288029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.-T. Dementia Caregiver Burden: A Research Update and Critical Analysis. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, G.; Shield, T.; Bayliss, K.; Rowland, C.; Flynn, J.; Bee, P.; Hodkinson, A.; Panagioti, M.; Farquhar, M.; Harris, D.; et al. Understanding the Potential Factors Affecting Carers’ Mental Health during End-of-Life Home Care: A Meta Synthesis of the Research Literature. Health Soc. Care Deliv. Res. 2022, 8, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco Barzallo, D.; Schnyder, A.; Zanini, C.; Gemperli, A. Gender Differences in Family Caregiving. Do Female Caregivers Do More or Undertake Different Tasks? BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sörensen, S.; Conwell, Y. Issues in Dementia Caregiving: Effects on Mental and Physical Health, Intervention Strategies and Research Needs. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2011, 19, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fernández, M.; Davis, C.; Molitoris, J.J.; Newhart, M.; Leigh, R.; Hillis, A.E. Formal Education, Socioeconomic Status and the Severity of Aphasia After Stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 1809–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodaty, H.; Donkin, M. Family Caregivers of People with Dementia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 11, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Beyond Ponce de Leon and Life Satisfaction: New Directions in Quest of Successful Ageing. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 1989, 12, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wister, A.; Li, L.; Mitchell, B.; Wolfson, C.; McMillan, J.; Griffith, L.E.; Kirkland, S.; Raina, P.; Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) Team; Costa, A.; et al. Levels of Depression and Anxiety Among Informal Caregivers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Study Based on the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2022, 77, 1740–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, N.R.; Kleinpeter, C.H. Gender Differences in Coping Strategies of Spousal Dementia Caregivers. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2002, 6, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, J.R.; Wilks, S.E.; Lovelace, L.L.; Chen, Z.; Spivey, C.A. Burden Among Male Alzheimer’s Caregivers: Effects of Distinct Coping Strategies. Am. J. Alzheimer's Dis. Other Dement. 2015, 30, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Sorensen, S. Correlates of Physical Health of Informal Caregivers: A Meta-Analysis. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2007, 62, P126–P137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.; Martire, L.M. Family Caregiving of Persons with Dementia: Prevalence, Health Effects and Support Strategies. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2004, 12, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costea-Bărluțiu, C.; Bălaș-Baconschi, C.; Hathazi, A. Romanian Adaptation of the Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale: Brief Report of the Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties. J. Evid.-Based Psychother. 2018, 18, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luştrea, A.; Ghazi, L.A.; Predescu, M. Adapting and Validating Ryff`s Psychological Well-Being Scale on Romanian Student Population. Educ. 2018, 21, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.J.; Del Valle, M.V.; López Morales, H.; Urquijo, S. Propiedades Psicométricas de La Escala de Bienestar Psicológico de Ryff En Argentina. Cienc. Psicol. 2024, 18, e-3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruini, C.; Ottolini, F.; Rafanelli, C.; Ryff, C.; Fava, G.A. La Validazione Italiana Delle Psychological Well-Being Scales (PWB). Riv. Psichiatr. 2003, 38, 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dierendonck, D. The Construct Validity of Ryff’s Scales of Psychological Well-Being and Its Extension with Spiritual Well-Being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bains, N.; Abdijadid, S. Major Depressive Disorder. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaya, H.; Atoui, M.; Hamadeh, A.; Zeinoun, P.; Nahas, Z. Adaptation and Initial Validation of the Patient Health Ques-tionnaire—9 (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder—7 Questionnaire (GAD-7) in an Arabic Speaking Lebanese Psychiatric Outpatient Sample. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 239, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.Y.; Chung, H.; Kroenke, K.; Delucchi, K.L.; Spitzer, R.L. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to Measure De-pression among Racially and Ethnically Diverse Primary Care Patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L. The PHQ-9: A New Depression Diagnostic and Severity Measure. Psychiatr. Ann. 2002, 32, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipman, R.S.; Covi, L.; Downing, R.; Fisher, S.; Kahn, R.; McNair, D.; Rickels, K.; Smith, V. Pharmacotherapy of Anxiety and Depression. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1981, 17, 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. Mini-Mental State. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombaugh, T.N.; McIntyre, N.J. The Mini-Mental State Examination: A Comprehensive Review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1992, 40, 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, T.; Carter, M. Using the Folstein Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) to Explore Methodological Issues in Cognitive Aging Research. Eur. J. Ageing 2012, 9, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mochón, L.; Peña-Longobardo, L.M.; Del Río-Lozano, M.; Oliva-Moreno, J.; Larrañaga-Padilla, I.; García-Calvente, M.D.M. Determinants of Burden and Satisfaction in Informal Caregivers: Two Sides of the Same Coin? The CUIDAR-SE Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaliano, P.P.; Echeverria, D.; Yi, J.; Phillips, P.E.M.; Young, H.; Siegler, I.C. Psychophysiological Mediators of Caregiver Stress and Differential Cognitive Decline. Psychol. Aging 2005, 20, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejalvo, E.; Martí-Vilar, M.; Merino-Soto, C.; Aguirre-Morales, M.T. Caregiving Role and Psychosocial and Individual Factors: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, M.E.; Setti, I.; Alfano, G.; Barello, S. Exploring Risk and Protective Factors for Burnout in Professionals Working in Death-Related Settings: A Scoping Review. Public Health 2025, 241, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro, J.M.; Kahle-Wrobleski, K.; Bruno, G.; Belger, M.; Dell’Agnello, G.; Dodel, R.; Jones, R.W.; Reed, C.C.; Vellas, B.; Wimo, A.; et al. Analysis of Burden in Caregivers of People with Alzheimer’s Disease Using Self-Report and Supervision Hours. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2014, 18, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, R.; Regan, C.; Katona, C.; Livingston, G. Anxiety and Depression in Family Caregivers of People With Alzheimer Disease: The LASER-AD Study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 13, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao, C.-Y.; Wu, H.-S.; Hsiao, C.-Y. Caregiver Burden for Informal Caregivers of Patients with Dementia: A Systematic Review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2015, 62, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Guo, Q.; Luo, J.; Li, F.; Ding, D.; Zhao, Q.; Hong, Z. Anxiety and Depression Symptoms among Caregivers of Care-Recipients with Subjective Cognitive Decline and Cognitive Impairment. BMC Neurol. 2016, 16, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, C. Factors Associated with Depression in Middle-Aged and Elderly People in Romania. Psichologija 2020, 61, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.; Sherwood, P.R. Physical and Mental Health Effects of Family Caregiving. Am. J. Nurs. 2008, 108, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatomirescu, L. F.; Glavce, C. S.; Prada, G. I.; Borosanu, A.; Turcu, S. Socio-Demographic Factors Linked to Psychological Well-Being in Dementia Caregivers. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).