1. Introduction

The traditional

“Gruiformes

” comprises diverse living and extinct bird lineages that share superficial similarities with rails or cranes and exhibit broad geographical distribution. However, recent phylogenetic analyses support the monophyly only of the more restricted “core Gruiformes” [

1,

2,

3], which includes the sister taxa Gruoidea, composed of Psophiidae (trumpeters), Aramidae (limpkin), and Gruidae (cranes), and Ralloidea, constituted by Rallidae (rails), Sarothruridae (flufftails), and Heliornithidae (finfoots) [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Among them, Rallidae stands out for its high dispersal capacity and cosmopolitan distribution. This is one of the most specious clades within the order, having colonized a broad range of habitats, from marshes and grasslands to forests, which often results in convergent morphological patterns that obscure their evolutionary history [

5]. Despite detailed anatomical studies of some fossil species [

e.g.

,; [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]], the fossil record of Rallidae provides limited insight into the early evolution of the family. Several early and middle Eocene remains previously attributed to Rallidae [

12,

16,

17,

18,

19] have either been rejected due to their fragmentary preservation [

10] or reassigned to other avian groups [

12,

20,

21,

22]. The earliest well-supported rallid fossils correspond to

Belgirallus oligocaenus and

B. minutus, both described by Mayr and Smith [

11] from the earliest Oligocene of Belgium and Germany [

11] with additional indeterminate remains from Egypt [

23]. The fossil record of Rallidae, and Gruiformes more broadly becomes increasingly abundant during the Neogene.

In Argentina, it includes the basal gruiform

Anisolornis excavatus Ameghino, 1891 from the Early–Middle Miocene Santa Cruz Formation [

24], as well as fragmentary Late Miocene remains from the Ituzaingó Formation referred to the extant genus Grus [

24]. Additional rallid fossils include Late Pleistocene remains of various extant

Fulica species from the Luján Formation in Buenos Aires Province [

26], and an indeterminate species of

Porphyrio from Middle Pleistocene deposits at Bajo San José, in the upper basin of the Río Sauce Grande [

27].

A new tarsometatarsus from Pleistocene levels of the La Esperanza Formation, exposed in Olavarría (Buenos Aires Province), is here assigned to the rallid Aramides cajaneus. A brief discussion of paleoenvironmental implications derived from this finding is provided below.

2. Materials and Methods

The specimen, collected by one of the authors (MDlR), is housed in the paleontological collection of Cementos Avellaneda (CCA), Olavarría, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, under the acronym CCA-165. It consists of a right tarsometatarsus. Comparative material is housed in the Ornithological Section (MLP-Or) of the Vertebrate Zoology Division at the Museo de La Plata (Argentina) and in the Division of Birds Collection (USNM) of the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution (USA).

Descriptions follow the osteological terminology of [

28] and the hypotarsus morphology as outlined by Mayr [

29]. Measurements were taken with a vernier caliper to the nearest 0.02 mm.

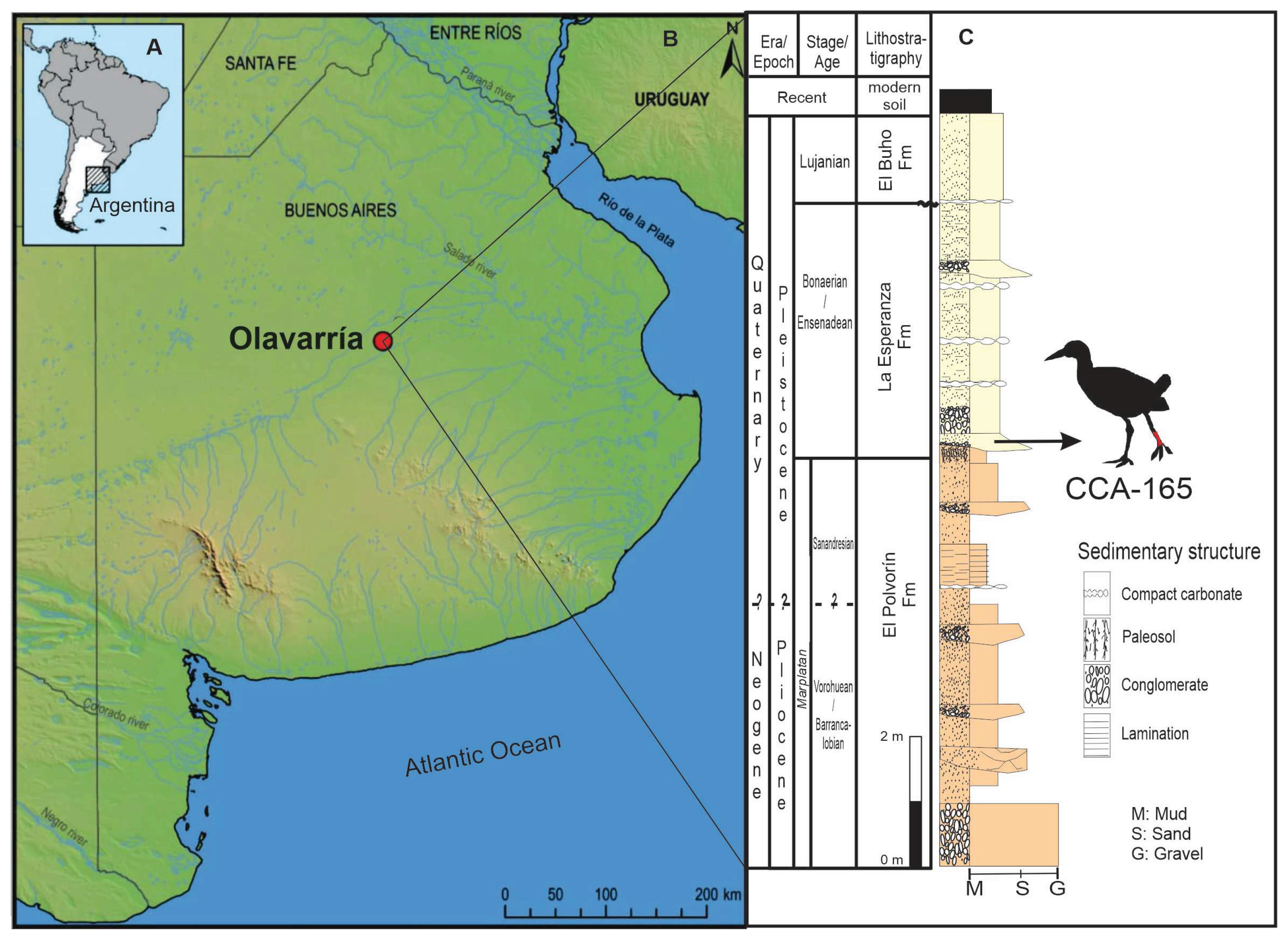

3. Geological and Geographical Setting

The study area is located near the city of Olavarría (S36°58′40′′.06; W60°12′23′.92), Buenos Aires Province, Argentina (Pampas Region). This area (

Figure 1A-C) exposes a Neogene-Quaternary succession (

Figure 1C), which has been exposed due to mining activity. The formational units of these Cenozoic packages are from base to top, the La Alcancía, El Polvorín, La Esperanza, and El Búho Formations [

30], which unconformably support Neoproterozoic units of the Sierras Bayas Group and the Cerro Negro Formation [

31]. The La Esperanza Formation [

30] consists of four levels. The basal layer, from which the fossil remains studied here originate (

Figure 1C), is composed of conglomerate lenses and coarse sands that contain abundant fossil remains, most of which are disarticulated and fragmented. Within the coarse sands, lenses of black tinges of manganese oxides are deposited; fossils also acquire a dark, blackish coloration.

The stratigraphic units of the quarry exhibit prominent erosional surfaces, characteristic of a mountainous environment subject to contemporary tectonic uplift [

30,

32]. The presence of coarse sands and conglomerates arranged in strata with decreasing grain size and lenticular structure suggests a high-energy environment with fluctuating flow. These characteristics are typical of braided fluvial systems [

33]. The lenticular structure reflects channel migration or bar formation within these systems, while the gradual decrease in grain size may indicate stream decline or episodic events such as floods.

Specimen CCA-165 was found at the time of the exhumation of a Glyptodon sp. carcase. Other remains of Hippidion sp., Lama sp., Panochthus intermedius, Glyptodon munizi, Mylodon, Glyptodontinae cf. Doedicurus, and Toxodontidae were exhumed from the same level. This diversity of taxa would correspond to an Ensenadense Stage/age (Gelasian-Calabrian), early Pleistocene.

3. Systematic Paleontology

Class Aves

Subclass Neornithes

Order Gruiformes

Family Rallidae

Genus Aramides

Aramides cajaneus

3.1. Material

CCA-165: right tarsometatarsus

3.2. Description

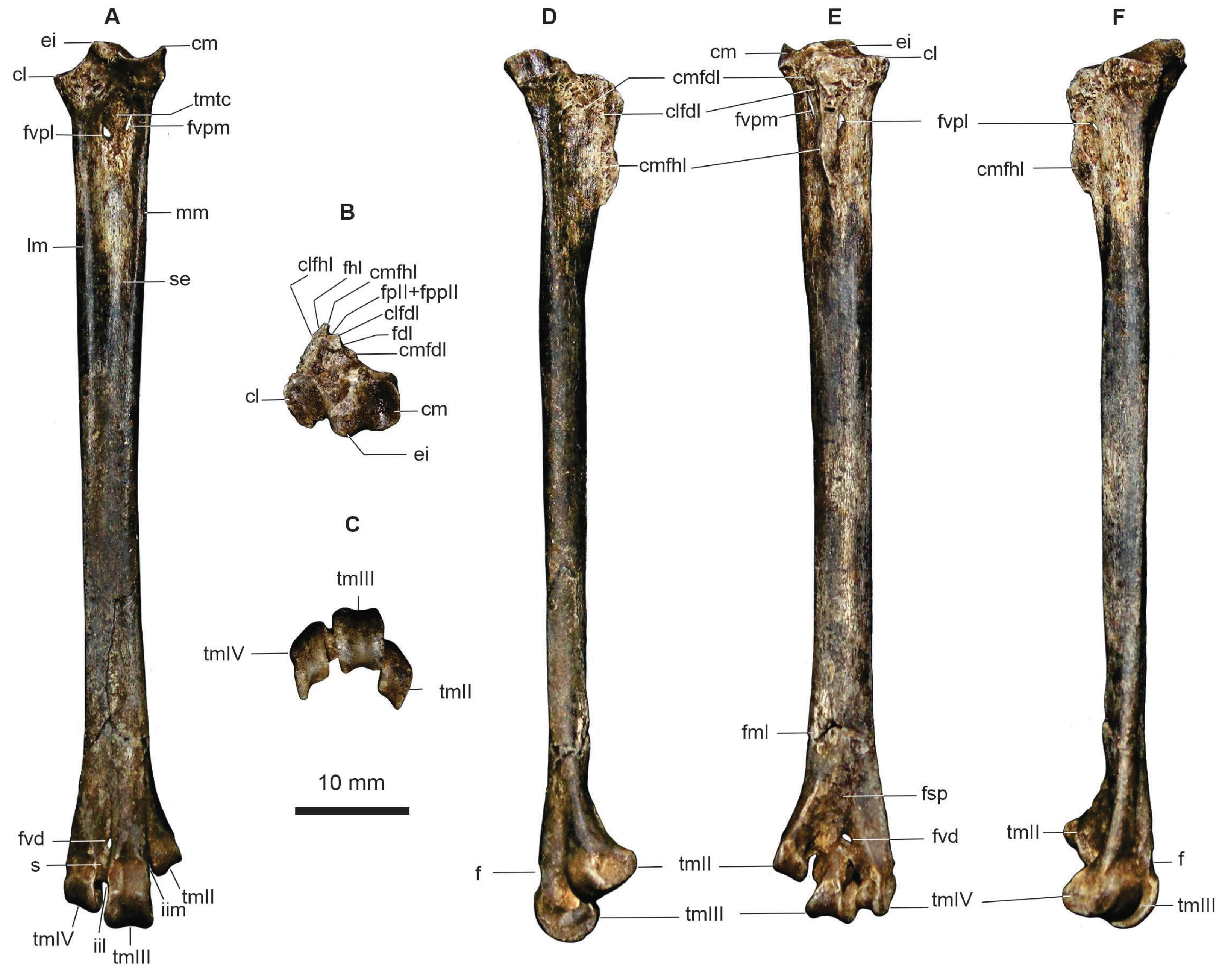

The tarsometatarsus is elongated, with a slender gracile shaft. The eminentia intercotylaris is pointed and projects proximally slightly beyond the medial rim of the cotyla medialis (

Figure 2A). The proximalmost portion of the shaft tapers both proximally and distally to the impressio lig. collateralis lateralis (

Figure 2A). In dorsal and plantar views, the foramen vasculare proximale mediale opens more proximally than the foramen vasculare proximale laterale (

Figure 2A, E). Both foramina are elongated and pierce the diaphysis, opening on either side of the hypotarsus (

Figure 2E).

The tuberositas musculi tibialis cranialis forms a rounded protuberance, distal to which the sulcus extensorius becomes slightly deeper. The lateral and medial edges of this sulcus are delimited by raised margins that become gradually lower distally (

Figure 2A).

The fossa metatarsi I is shallow and elongated (

Figure 2E). The trochlea metatarsi II ends more proximally than the incisura intertrochlearis lateralis; the trochlea is relatively more distally projected and plantarly deflected, with the medial margin projecting even farther plantarly. The trochlea metatarsi III is the most symmetrical in terms of plantar projection and the development of its trochlear margins. It is also the most dorsally positioned and is slightly displaced medially relative to the shaft axis. The trochlea metatarsi IV shows an intermediate degree of plantar deflection (

Figure 2C, F). Its margins are symmetrical in dorsal view, although the lateral margin is more expanded plantarly than the medial one (

Figure 2A, C, E).

The foramen vascular distale is large and opens on both the plantar and dorsal surfaces, well separated from the incisura intertrochlearis lateralis. A deep sulcus extends proximally from this foramen along the shaft but does not reach the sulcus extensorius (

Figure 2A, E). Well-defined pits or rounded fossae are developed along the margins of trochleae metatarsalia III and IV (

Figure 2A, D, E). The fossa supratrochlearis plantaris is triangular and contains two foramina of unequal size at its proximal portion (

Figure 2E).

The hypotarsus is slightly eroded, and the canal for the tendon of the musculus flexor digitorum longus (fdl) is broken, appearing as an open sulcus bounded by the crista medialis fdl and the crista lateralis fdl. The crista medialis of the canal for the tendon of musculus flexor hallucis longus (fhl) is the most prominent. It is inclined medially and separates the sulcus for the tendons of musculus flexor perforatus digiti II and musculus flexor perforans et perforatus digiti II from that of the fhl. The crista lateralis fhl is barely developed. The fossa parahypotarsalis medialis is absent (

Figure 2B).

3.3. Remarks

The genus

Aramides includes eight species (

A. ypecaha,

A. wolfi,

A. mangle,

A. saracura,

A. calopterus,

A. cajaneus,

A. albiventris, and

A. axillaris), which are similar to each other and mainly distinguished by throat, breast, and belly coloration, along with certain differences in size and proportions [

34]. According to published data, the intraspecific variation of

A. cajaneus (Gray-cowled Wood-Rail) ranges from 33 to 40 cm in height and from 320 to 480 g in weight [

35], with the largest individuals being up to 21% taller and 50% heavier than the smallest ones.

This variation is also reflected in tarsometatarsal length. For example, adult females MLP-Or 2156 from Argentina and USNM 612267 from Panama have tarsometatarsi measuring 90 mm and 80 mm in length, respectively. CCA-165, measuring 83.25 mm in length, falls within this intraspecific range.

4. Discussion

The La Esperanza Formation in Olavarría has long been recognized for its contributions to the understanding of Pleistocene faunas. However, no avian remains had been reported from this locality until now. This study documents the first occurrence of rails (Aves, Gruiformes, Rallidae) in the formation, expanding the known diversity of its Pleistocene vertebrate assemblage. As previously noted, and in contrast to the present-day abundance and diversity of the group, the fossil record of Rallidae in Argentina is limited to a few fragmentary remains.

The specimen described here is assigned to

Aramides based on a combination of features that also distinguish it from other rallids with a similar tarsometatarsal morphology, such as

Fulica and

Pardirallus. In

Aramides, as in the specimen CCA-165, the trochlea metatarsi II terminates more proximally than the incisura intertrochlearis lateralis. The tarsometatarsus is elongated with a slender shaft, including a proximally projected and sharply defined eminentia intercotylaris (rounded and blunt in Fulica), and gracile trochleae that are moderately divergent. The shaft narrows more abruptly distal to the cotylae than in

Pardirallus, and the sulcus extensorius that hosts two large foramina vascularia is delimited by well-defined edges. The hypotarsus configuration matches that of other rallids [

29] (

Figure 4), [

36] (

Figure 2), with a well-developed and medially inclined crista medialis for the flexor hallucis longus, a weakly developed crista lateralis fhl, and a sulcus for the flexor digitorum longus, likely modified (from a canal) by taphonomic processes.

The presence of Aramides provides valuable paleoenvironmental information about the conditions that prevailed in the region during the Pleistocene. Although the genus comprises terrestrial species, they are consistently linked to wetland environments. Of the two species currently occurring in or near the area where specimen CCA-165 was recovered, only A. cajaneus matches it in size.

Aramides cajaneus is the most widely distributed rallid in the Americas, ranging from southwestern Central America to central Argentina, reaching just north of Olavarría. It typically inhabits riparian and swampy environments, including forested wetlands, stream banks, and marsh margins. Although it generally remains concealed in dense vegetation, it occasionally forages in open areas. Nests are constructed above the ground, often over water, using twigs and grasses, and placed in shrubs or trees up to three meters high. Due to its ecological flexibility,

A. cajaneus inhabits a wide range of moist habitats, including seasonal wetlands, reedbeds, and humid scrublands adjacent to wooded zones [

35,

37].

The occurrence of A. cajaneus in the La Esperanza Formation suggests that wooded or semi-wooded wetlands were present in the area during the Pleistocene. This is consistent with the information derived from the sedimentary structures observed in the collecting site, which indicate fluvial environments. This finding helps reconstruct local paleoenvironments and provides a foundation for further research on avian biogeography and environmental change in southern South America, particularly in the Pampean Region during the Pleistocene.

5. Conclusions

The tarsometatarsus CCA-165 is confidently assigned to Aramides cajaneus (Rallidae, Gruiformes), a modern species with a broad distribution across the Neotropics, extending as far south as areas near the discovery site. This record constitutes not only the first occurrence of A. cajaneus in the fossil record of Argentina, but also the first avian remains recovered from the Pleistocene deposits of the La Esperanza Formation (Olavarría, Argentina). Beyond its taxonomic importance, the presence of this species provides valuable paleoenvironmental insights. The ecological preferences of extant A. cajaneus indicate that the area was likely characterized by seasonal wetlands and/or humid scrublands during the Late Pleistocene. Additionally, the nesting behavior of the species, which requires vegetated and wooded areas, suggests the existence of forested patches in the landscape. Taken together, this evidence contributes to refining paleoenvironmental reconstructions for the region and underscores the relevance of avian fossils as indicators of past habitats.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.H., M.D.L.R, and M.A.S.; methodology, C.A.H., M.D.L.R, and M.A.S.; validation, C.A.H., M.D.L.R, and M.A.S.; formal analysis, C.A.H., M.D.L.R, and M.A.S.; investigation, C.A.H., M.D.L.R, and M.A.S.; resources, C.A.H. and M.D.L.R; data curation, M.D.L.R; writing—original draft preparation C.A.H., M.D.L.R, and M.A.S.; writing—review and editing, C.A.H., M.D.L.R, and M.A.S.; visualization, C.A.H., M.D.L.R, and M.A.S.; supervision, C.A.H; project administration, C.A.H. and M.D.L.R; funding acquisition, C.A.H., M.D.L.R, and M.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Universidad Nacional de La Plata.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting reported results can be found in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the company “Cementos Avellaneda S. A.” for promoting and supporting research in Paleontology and for allowing us to study the materials. To Mariana Picasso (MLP) for access to comparative material, and Jorge La Grotteria for kindly providing the photo of Aramides cajaneus.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ericson, P.G.P.; Anderson, C.L.; Britton, T.; Elżanowski, A.; Johansson, U.S.; Källersjö, M.; Ohlson, J.I.; Parsons, T.J.; Zuccon, D.; Mayr, G. Diversification of Neoaves: Integration of molecular sequence data and fossils. Biology Letters 2006, 2, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fain, M.G.; Krajewski, C.; Houde, P. Phylogeny of “core Gruiformes” (Aves: Grues) and resolution of the Limpkin–Sungrebe problem. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 2007, 43, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, S.J.; Kimball, R.T.; Reddy, S.; Bowie, R.C.K.; Braun, E.L.; Braun, M.J.; Chojnowski, J.L.; Cox, W.A. , Han, K.-L., Harshman, J., Huddleston, C.J., Marks, B.D., Miglia, K.J., Moore, W.S., Sheldon, F.H., Steadman, D.W., Witt, C.C., and Yuri, T. A phylogenomic study of birds reveals their evolutionary history. Science 2008, 320, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, G. Metaves, Mirandornithes, Strisores and other novelties: A critical review of the higher-level phylogeny of neornithine birds. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 2011, 18, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-R, J.C.; Gibb, G.C.; Trewick, S.A. Deep global evolutionary radiation in birds: Diversification and trait evolution in the cosmopolitan bird family Rallidae. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 2014, 81, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prum, R.O.; Berv, J.S.; Dornburg, A.; Field, D.J.; Townsend, J.P.; Lemmon, E.M.; Lemmon, A.R. A comprehensive phylogeny of birds (Aves) using targeted next-generation DNA sequencing. Nature 2015, 526, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, G. The Paleogene fossil record of birds in Europe. Biological Reviews 2005, 80, 515–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayr, G. A rail (Aves, Rallidae) from the early Oligocene of Germany. Ardea 2006, 94, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr, G. A new raptorial bird from the Middle Eocene of Messel, Germany. Historical Biology 18, 95–102. [CrossRef]

- Mayr, G. Paleogene fossil birds, 2nd ed.; Springer. Switzerland, 2009; pp. 1–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, G.; Smith, R. Ducks, rails, and limicoline waders (Aves: Anseriformes, Gruiformes, Charadriiformes) from the lowermost Oligocene of Belgium. Géobios 2001, 34, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, S.L. A synopsis of the fossil Rallidae. In Rails of the world: A monograph of the family Rallidae; Ripley, D.S., Ed.; Godine, 1977a; pp. 339–379. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, S.L. The fossil record of birds. In Avian biology; Farner, D.S., King, J.R., Parkes., K.C., Eds.; Academic Press: USA, 1985; Vol. 3, pp. 79–238. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman, D.W. Prehistoric extinctions of Pacific Island birds: Biodiversity meets zooarchaeology. Science 1995, 267, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steadman, D.W. 2006. In Extinction and biogeography of tropical Pacific birds; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, USA, 2006; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, C.J.O.; Walker, C.A. Birds of the British Upper Eocene. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 1976, 59, 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.J.O.; Walker, C.A. Birds of the British Middle Eocene. In Studies in Tertiary avian paleontology; Harrison, C.J.O.; Walker, C.A., Eds. Tertiary Research Special Paper 1979, 5, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, C.J.O. Further additions to the fossil birds of Sheppey: A new falconid and three small rails. Tertiary Research 1984, 5, 179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Mlíkovský, J. Cenozoic birds of the world. Part 1: Europe; Ninox Press: Czech Republic, 2002; pp. 1–417. [Google Scholar]

- Cracraft, J. Systematics and evolution of the Gruiformes (Class Aves). 3. Phylogeny of the suborder Grues. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 151, 1–127.

- Cracraft, J. Continental drift, paleoclimatology, and the evolution and biogeography of birds. Journal of Zoology 169, 455–545. [CrossRef]

- Mourer-Chauviré, C. The Galliformes (Aves) from the Phosphorites du Quercy (France): Systematics and biostratigraphy. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Science Series 1992, 36, 67–95. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, D.T.; Olson, S.L.; Simons, E.L. Fossil birds from the Oligocene Jebel Qatrani Formation, Fayum Province, Egypt. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 1987, 62, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degrange, F.J.; Noriega, J.I.; Areta, J. Diversity and paleobiology of the Santacrucian birds. In Early Miocene paleobiology in Patagonia: High-latitude paleocommunities of the Santa Cruz Formation; Vizcaíno, S.F., Kay, R.F., Bargo, M.S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, USA, 2012; pp. 138–154. [Google Scholar]

- Noriega, J.I.; Agnolín, F.L. El registro paleontológico de las aves del “Mesopotamiense” (Formación Ituzaingó; Mioceno Tardío–Plioceno) de la provincia de Entre Ríos, Argentina. INSUGEO: Tucumán, Argentina, 2008, 17, 271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Cenizo, M.M.; Agnolín, F.L.; Pomi, L.H. A new Pleistocene bird assemblage from the Southern Pampas (Buenos Aires, Argentina). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 2015, 420, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, C.; Tomassini, R. Late Cenozoic vertebrates from the southern Pampean Region: Systematic and biochronostratigraphic update. In Palinología del Meso–Cenozoico de Argentina; Martínez, M.; Olivera, D. Eds.; Publicación Electrónica de la Asociación Paleontológica Argentina 2016, 16, 202–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumel, J.J. Handbook of avian anatomy: Nomina anatomica avium (No. 23); Publications of the Nuttall Ornithological Club: Cambridge, USA, 1993; pp. 1–719. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr, G. Variations in the hypotarsus morphology of birds and their evolutionary significance. Acta Zoologica 2016, 97, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poiré, D.G. Secuencias sedimentarias Neoproterozoico–Paleozoico inferior del Sistema de Tandilia y su cobertura del Terciario superior–Cuaternario en la zona de Olavarría: Guía de campo. Centro de Investigaciones Geológicas 2012, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Poiré, D.G.; Gaucher, C. Lithostratigraphy: Neoproterozoic–Cambrian evolution of the Río de la Plata Palaeocontinent. In Neoproterozoic–Cambrian tectonics, global change and evolution: A focus on southwestern Gondwana, Gaucher, C.; Sial, A.N.; Halverson, G.P.; Frimmel, H.E., Eds., Developments in Precambrian Geology 2009, 16, 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Poiré, D.G.; Canessa, N.D.; Scillato-Yané, G.J. : Carlini, A. A.; Canalicchio, J.M.; Tonni, E.P. La Formación El Polvorín: Una nueva unidad del Neógeno de Sierras Bayas, Sistema de Tandilia, Argentina. Actas del XVI Congreso Geológico Argentino, 2005, 1, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, J.S. Rivers and floodplains; Blackwells, Oxford, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, D.W.; Billerman, S.M.; Lovette, I.J. Rails, gallinules, and coots (Rallidae), version 1.0. In Birds of the world; Billerman, S.M., Keeney, B.K., Rodewald, P.G., Schulenberg, T.S., Eds.; Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, L.G.; Salvador, S.A. Datos de pesos de aves argentinas. Parte 4. Historia Natural, 2017, 7, 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- De Mendoza, R.S.; Carril, J.; Degrange, F.J.; Tambussi, C.P. Specialized diving traits in the generalist morphology of Fulica (Aves, Rallidae). Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 13966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B. Gray-cowled Wood-Rail (Aramides cajaneus), version 1.0. In Birds of the world; Billerman, S.M., Keeney, B.K., Rodewald, P.G., Schulenberg, T.S., Eds.; Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).