Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and Reagents

2.2. Generation of PEDV Mutants

2.3. RNA Secondary Structure Prediction Using mFold

2.4. Plaque Assay

2.5. Growth Kinetics for PEDV Mutants

2.6. The Detection of PEDV Genomic and sgmRNA by Reverse Transcription-Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

2.7. The Detection of PEDV RNA Junction by RNA-seq

2.8. Interferon Induction Assay

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

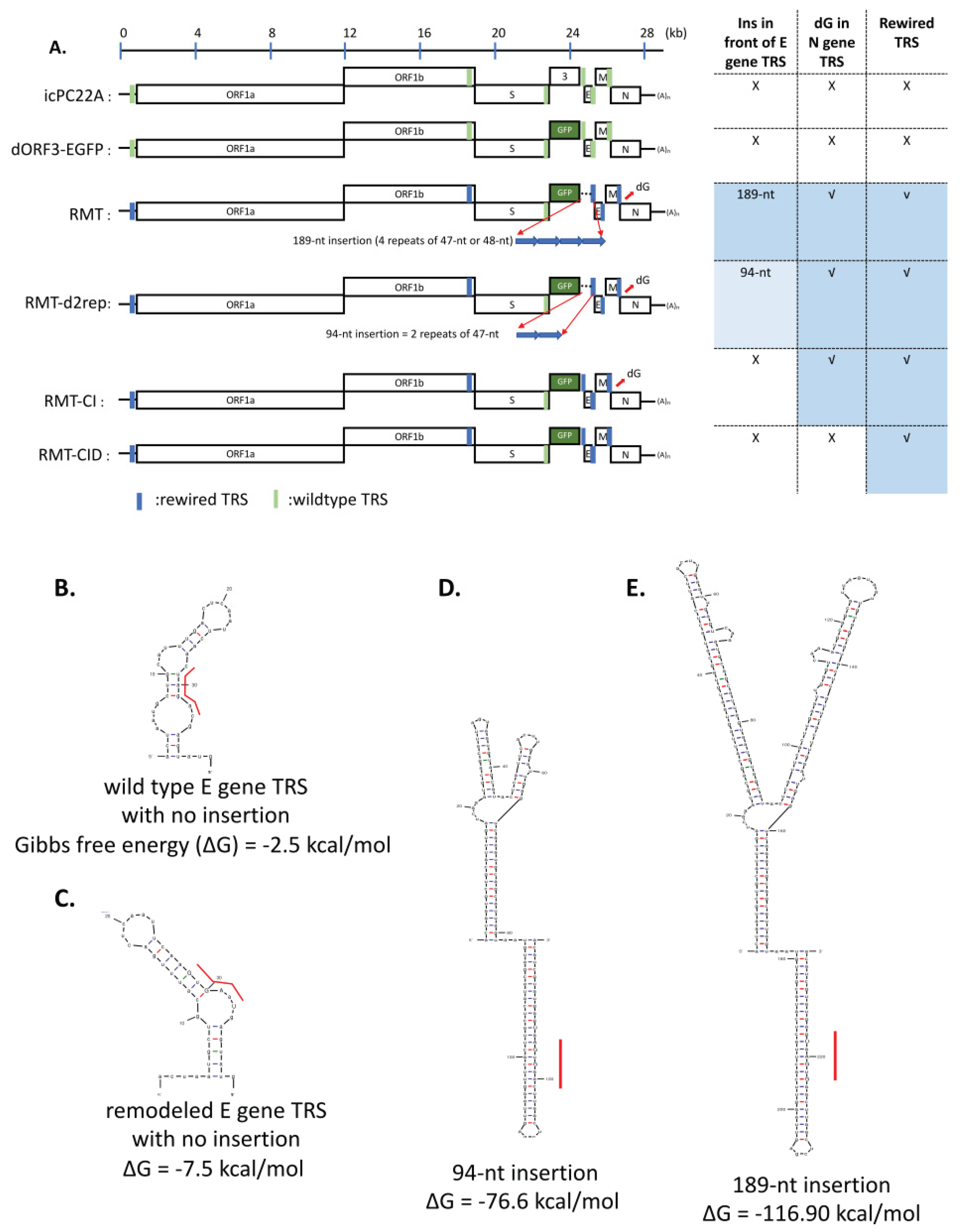

3.1. A Series of PEDV Mutants Were Rescued Using Reverse Genetics

3.2. The Mutations in the TRS Region Changed PEDV Replication Kinetics and Plaque Morphology in Vero Cells

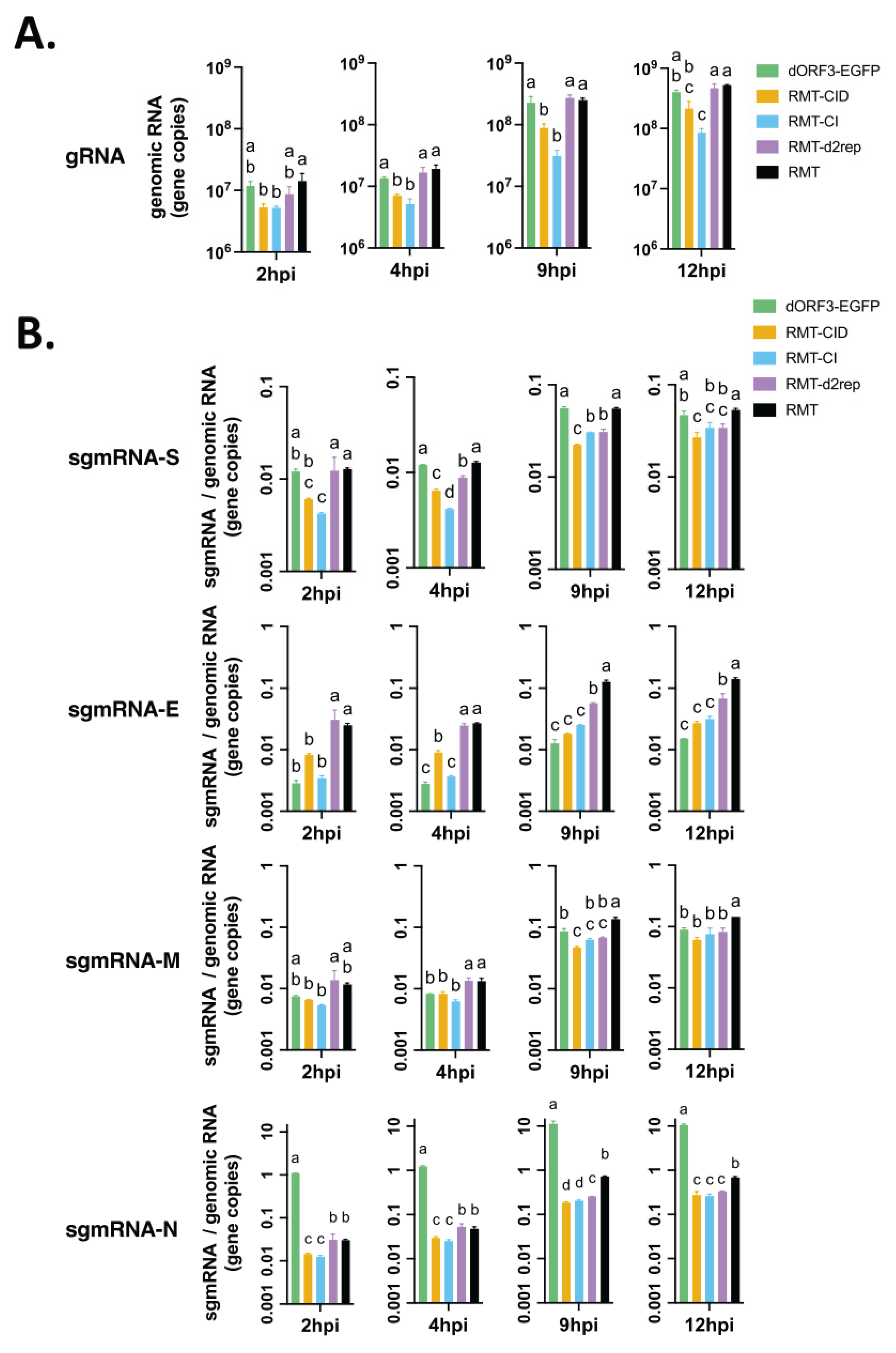

3.3. TRS Mutations Disrupted the Subgenomic RNA Transcription of PEDV in Vero Cells

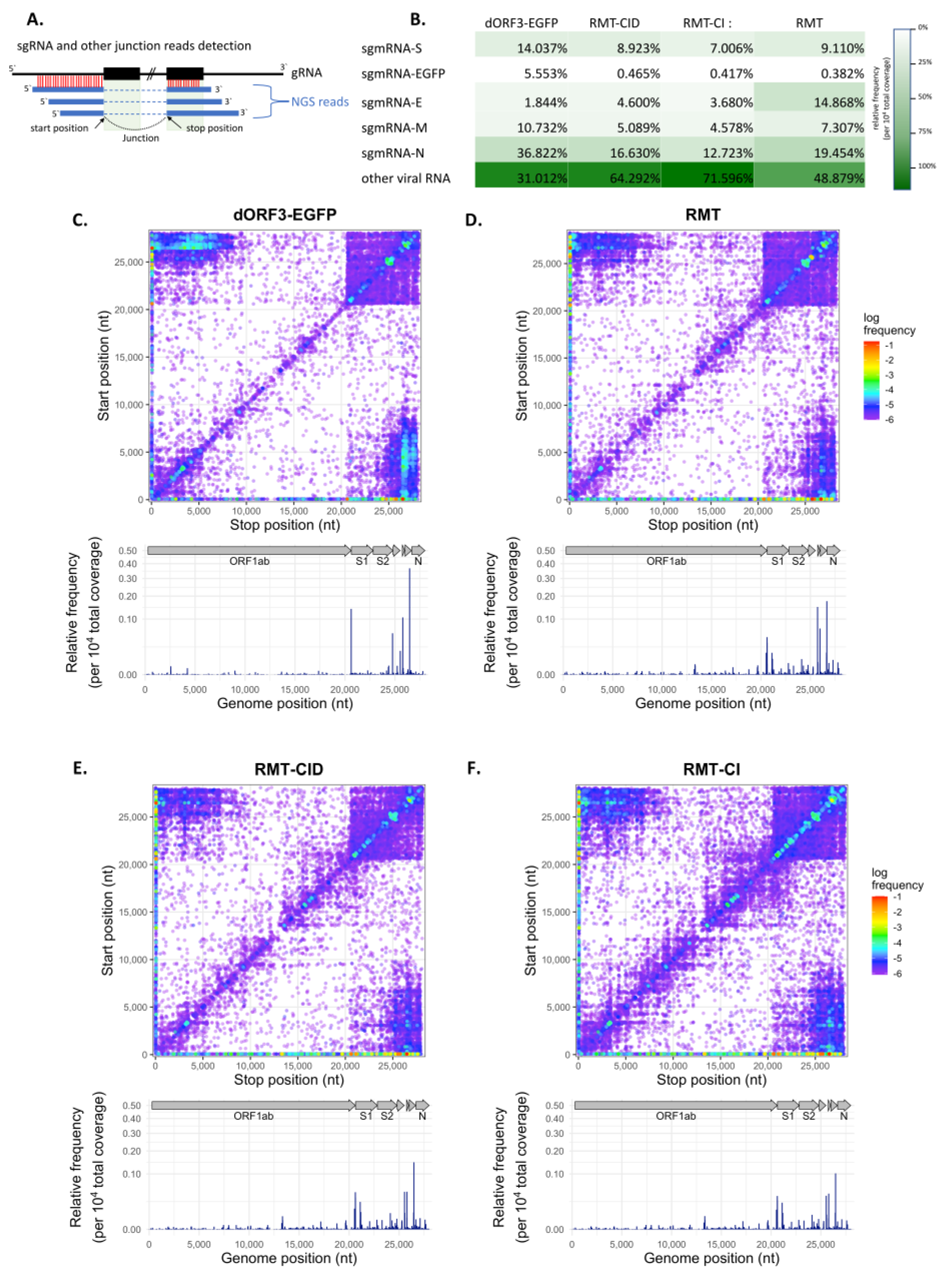

3.4. Canonical and Non-Canonical sgmRNA Syntheses Were Altered in TRS Mutants in Vero Cells

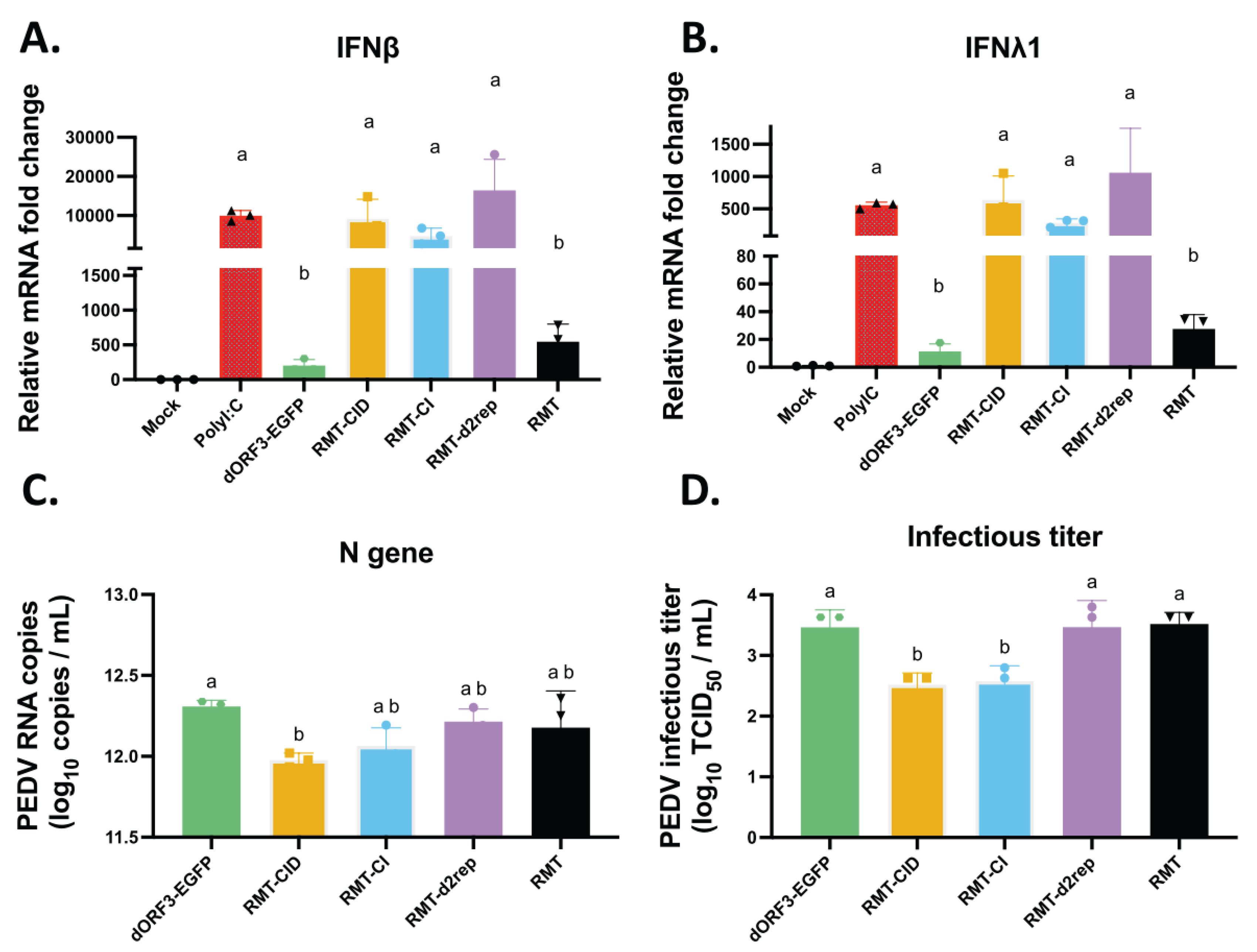

3.5. Effects of TRS Mutations on Type I and Type III IFN Responses, Viral Replication and sgmRNA Abundance in Porcine LLC-PK1 Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CoV | coronaviruses |

| PEDV | porcine epidemic diarrhea virus |

| TRS-CS | transcription regulatory sequences- core sequences |

| gRNA | genomic RNA |

| sgmRNA | subgenomic messenger RNA |

| RMT | ReModel-Trs mutant |

| RMT-CI | RMT-Corrected Insertion |

| RMT-CID | RMT- Corrected Insertion and Deletion |

| RMT-d2rep | RMT-delete 2 repeats |

References

- Deng, X.; Baker, S.C. Coronaviruses: Molecular Biology (Coronaviridae). Encyclopedia of Virology 2021, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasova, A.N.; Kenney, S.P.; Jung, K.; Wang, Q.; Saif, L.J. Deltacoronavirus Evolution and Transmission: Current Scenario and Evolutionary Perspectives. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2021, 7, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiris, J.S.M.; Lai, S.T.; Poon, L.L.M.; Guan, Y.; Yam, L.Y.C.; Lim, W.; Nicholls, J.; Yee, W.K.S.; Yan, W.W.; Cheung, M.T.; et al. Coronavirus as a Possible Cause of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Lancet 2003, 361, 1319–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, A.M.; Boheemen, S. van; Bestebroer, T.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Isolation of a Novel Coronavirus from a Man with Pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. New England Journal of Medicine 2012, 367, 1814–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.-M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.-G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.-W.; Tian, J.-H.; Pei, Y.-Y.; et al. Author Correction: A New Coronavirus Associated with Human Respiratory Disease in China. Nature 2020, 580, E7–E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. A Pneumonia Outbreak Associated with a New Coronavirus of Probable Bat Origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Lorusso, A. Novel Human Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): A Lesson from Animal Coronaviruses. Veterinary Microbiology 2020, 244, 108693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, EN. An Apparently New Syndrome of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhoea. Vet. Rec. 1977, 100, 243–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, F.; Jia, H.; Xiao, Q.; Fang, L.; Wang, Q. Prevention and Control of Swine Enteric Coronaviruses in China: A Review of Vaccine Development and Application. Vaccines 2024, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Deng, F.; Song, Y.; Tang, X.; He, Q. New Variants of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus, China, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Saif, L.J.; Wang, Q. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus (PEDV): An Update on Etiology, Transmission, Pathogenesis, and Prevention and Control. Virus Res 2020, 286, 198045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.T.; Chen, Q.; Gauger, P.C.; Giménez-Lirola, L.G.; Sinha, A.; Harmon, K.M.; Madson, D.M.; Burrough, E.R.; Magstadt, D.R.; Salzbrenner, H.M.; et al. Effect of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Infectious Doses on Infection Outcomes in Naïve Conventional Neonatal and Weaned Pigs. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0139266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Lin, C.-M.; Annamalai, T.; Gao, X.; Lu, Z.; Esseili, M.A.; Jung, K.; El-Tholoth, M.; Saif, L.J.; Wang, Q. Determination of the Infectious Titer and Virulence of an Original US Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus PC22A Strain. Vet Res 2015, 46, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.-Q.; Cai, R.-J.; Chen, Y.-Q.; Liang, P.-S.; Chen, D.-K.; Song, C.-X. Outbreak of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea in Suckling Piglets, China. Emerg Infect Dis 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, L.L.; Tonsor, G.T. Assessment of the Economic Impacts of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus in the United States. Journal of Animal Science 2015, 93, 5111–5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Park, B. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhoea Virus: A Comprehensive Review of Molecular Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Vaccines. Virus Genes 2012, 44, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Wang, Q. Prevention and Control of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea: The Development of Recombination-Resistant Live Attenuated Vaccines. Viruses 2022, 14, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Vlasova, A.N.; Kenney, S.P.; Saif, L.J. Emerging and Re-Emerging Coronaviruses in Pigs. Curr Opin Virol 2019, 34, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternak, A.O.; Spaan, W.J.M.; Snijder, E.J. Nidovirus Transcription: How to Make Sense…? Journal of General Virology 2006, 87, 1403–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Lin, C.-M.; Yokoyama, M.; Yount, B.L.; Marthaler, D.; Douglas, A.L.; Ghimire, S.; Qin, Y.; Baric, R.S.; Saif, L.J.; et al. Deletion of a 197-Amino-Acid Region in the N-Terminal Domain of Spike Protein Attenuates Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus in Piglets. Journal of Virology 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, A.; Yount, B.; Lin, C.-M.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Saif, L.; Baric, R. Characterization of a Pathogenic Full-Length cDNA Clone and Transmission Model for Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Strain PC22A. mBio 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pensaert, MB.; De Bouck, P. A New Coronavirus-like Particle Associated with Diarrhea in Swine. Archives of Virology 1978, 58, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egberink, H.F.; Ederveen, J.; Callebaut, P.; Horzinek, M.C. Characterization of the Structural Proteins of Porcine Epizootic Diarrhea Virus, Strain CV777. Am J Vet Res 1988, 49, 1320–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawicki, S.G.; Sawicki, D.L. Coronaviruses Use Discontinuous Extension for Synthesis of Subgenome-Length Negative Strands. Adv Exp Med Biol 1995, 380, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, S.G.; Sawicki, D.L. A New Model for Coronavirus Transcription. Adv Exp Med Biol 1998, 440, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, S.G.; Sawicki, D.L.; Siddell, S.G. A Contemporary View of Coronavirus Transcription. Journal of Virology 2007, 81, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, I.; Almazán, F.; Zúñiga, S.; Enjuanes, L. Continuous and Discontinuous RNA Synthesis in Coronaviruses. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2015, 2, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, I.; Moreno, J.L.; Zúñiga, S.; Alonso, S.; Enjuanes, L. Role of Nucleotides Immediately Flanking the Transcription-Regulating Sequence Core in Coronavirus Subgenomic mRNA Synthesis. J Virol 2005, 79, 2506–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, S.; Sola, I.; Alonso, S.; Enjuanes, L. Sequence Motifs Involved in the Regulation of Discontinuous Coronavirus Subgenomic RNA Synthesis. J Virol 2004, 78, 980–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, I.; Mateos-Gomez, P.A.; Almazan, F.; Zuñiga, S.; Enjuanes, L. RNA-RNA and RNA-Protein Interactions in Coronavirus Replication and Transcription. RNA Biology 2011, 8, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, S.; Izeta, A.; Sola, I.; Enjuanes, L. Transcription Regulatory Sequences and mRNA Expression Levels in the Coronavirus Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus. J Virol 2002, 76, 1293–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, A.; Lavezzari, D.; Pomari, E.; Deiana, M.; Piubelli, C.; Capobianchi, M.R.; Castilletti, C. sgRNAs: A SARS-CoV-2 Emerging Issue. Aspects of Molecular Medicine 2023, 1, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, J.-Y.; Yang, J.-S.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, V.N.; Chang, H. The Architecture of SARS-CoV-2 Transcriptome. Cell 2020, 181, 914–921.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Jiang, A.; Feng, J.; Li, G.; Guo, D.; Sajid, M.; Wu, K.; Zhang, Q.; Ponty, Y.; Will, S.; et al. The SARS-CoV-2 Subgenome Landscape and Its Novel Regulatory Features. Molecular Cell 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, X.; Liu, M.; Yang, S.; Xu, J.; Hou, Y.J.; Liu, D.; Tang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Q. A Recombination-Resistant Genome for Live Attenuated and Stable PEDV Vaccines by Engineering the Transcriptional Regulatory Sequences. Journal of Virology 2023, 0, e01193–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Aryal, B.; Niu, X.; Wang, Q. Engineering a Recombination-Resistant Live Attenuated Vaccine Candidate with Suppressed Interferon Antagonists for PEDV. Journal of Virology 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Chen, J.; Cao, Z.; Guo, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Tong, G.; Gao, F. Engineering a Live-Attenuated Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus Vaccine to Prevent RNA Recombination by Rewiring Transcriptional Regulatory Sequences. mBio 2024, 0, e02350–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yount, B.; Roberts, R.S.; Lindesmith, L.; Baric, R.S. Rewiring the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) Transcription Circuit: Engineering a Recombination-Resistant Genome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, 12546–12551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, T.; Saif, L.J.; Marthaler, D.; Esseili, M.A.; Meulia, T.; Lin, C.-M.; Vlasova, A.N.; Jung, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q. Cell Culture Isolation and Sequence Analysis of Genetically Diverse US Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Strains Including a Novel Strain with a Large Deletion in the Spike Gene. Veterinary microbiology 2014, 173, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Kong, F.; Xu, J.; Liu, M.; Wang, Q. Mutations in Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Nsp1 Cause Increased Viral Sensitivity to Host Interferon Responses and Attenuation In Vivo. Journal of Virology 2022, 96, e00469–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Ke, H.; Kim, J.; Yoo, D.; Su, Y.; Boley, P.; Chepngeno, J.; Vlasova, A.N.; Saif, L.J.; Wang, Q. Engineering a Live Attenuated PEDV Vaccine Candidate via Inactivation of the Viral 2′-O Methyltransferase and the Endocytosis Signal of the Spike Protein. Journal of Virology 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuker, M. Mfold Web Server for Nucleic Acid Folding and Hybridization Prediction. Nucleic Acids Research 2003, 31, 3406–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, M.; Niu, X.; Hanson, J.; Jung, K.; Ru, P.; Tu, H.; Jones, D.M.; Vlasova, A.N.; Saif, L.J.; et al. The Cold-Adapted, Temperature-Sensitive SARS-CoV-2 Strain TS11 Is Attenuated in Syrian Hamsters and a Candidate Attenuated Vaccine. Viruses 2023, 15, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A SIMPLE METHOD OF ESTIMATING FIFTY PER CENT ENDPOINTS12. American Journal of Epidemiology 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotcheff, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yeung, J.; Sun, Y.; Johnson, J.E.; Torbett, B.E.; Routh, A.L. ViReMa: A Virus Recombination Mapper of next-Generation Sequencing Data Characterizes Diverse Recombinant Viral Nucleic Acids. Gigascience 2023, 12, giad009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Niu, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, Q. Bile Acids LCA and CDCA Inhibited Porcine Deltacoronavirus Replication in Vitro. Vet Microbiol 2021, 257, 109097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Fang, L.; Jing, H.; Zeng, S.; Wang, D.; Liu, L.; Zhang, H.; Luo, R.; Chen, H.; Xiao, S. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Nucleocapsid Protein Antagonizes Beta Interferon Production by Sequestering the Interaction between IRF3 and TBK1. J Virol 2014, 88, 8936–8945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, Y.; Dong, J.; Liang, Y.; Liu, H.-J.; Tong, D. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus N Protein Prolongs S-Phase Cell Cycle, Induces Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, and up-Regulates Interleukin-8 Expression. Vet Microbiol 2013, 164, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Fragoso-Saavedra, M.; Liu, Q. Upregulation of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus (PEDV) RNA Translation by the Nucleocapsid Protein. Virology 2025, 602, 110306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrapp, D.; McLellan, J.S. The 3.1-Angstrom Cryo-Electron Microscopy Structure of the Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Spike Protein in the Prefusion Conformation. J Virol 2019, 93, e00923–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, B.J.; van der Zee, R.; de Haan, C.A.M.; Rottier, P.J.M. The Coronavirus Spike Protein Is a Class I Virus Fusion Protein: Structural and Functional Characterization of the Fusion Core Complex. J Virol 2003, 77, 8801–8811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, R.L.; Deming, D.J.; Deming, M.E.; Yount, B.L.; Baric, R.S. Evaluation of a Recombination-Resistant Coronavirus as a Broadly Applicable, Rapidly Implementable Vaccine Platform. Commun Biol 2018, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Xia, H.; Zou, J.; Muruato, A.E.; Periasamy, S.; Kurhade, C.; Plante, J.A.; Bopp, N.E.; et al. A Live-Attenuated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Candidate with Accessory Protein Deletions. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yan, W.; Hall, A.B.; Jiang, X. Characterizing Transcriptional Regulatory Sequences in Coronaviruses and Their Role in Recombination. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2021, 38, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniotti, M.B.; Papetti, A.; Lavazza, A.; Alborali, G.; Sozzi, E.; Chiapponi, C.; Faccini, S.; Bonilauri, P.; Cordioli, P.; Marthaler, D. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus and Discovery of a Recombinant Swine Enteric Coronavirus, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis 2016, 22, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, S.; Gaudieri, S.; Parker, M.D.; Chopra, A.; James, I.; Pakala, S.; Alves, E.; John, M.; Lindsey, B.B.; Keeley, A.J.; et al. Generation of a Novel SARS-CoV-2 Sub-Genomic RNA Due to the R203K/G204R Variant in Nucleocapsid: Homologous Recombination Has Potential to Change SARS-CoV-2 at Both Protein and RNA Level. Pathog Immun 2021, 6, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mears, H.V.; Young, G.R.; Sanderson, T.; Harvey, R.; Barrett-Rodger, J.; Penn, R.; Cowton, V.; Furnon, W.; Lorenzo, G.D.; Crawford, M.; et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 Subgenomic RNAs That Enhance Viral Fitness and Immune Evasion. PLOS Biology 2025, 23, e3002982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duguay, B.A.; Tooley, T.H.; Pringle, E.S.; Rohde, J.R.; McCormick, C. A Yeast-Based Reverse Genetics System to Generate HCoV-OC43 Reporter Viruses Encoding an Eighth Subgenomic RNA. Journal of Virology 2025, 99, e01671–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stombaugh, J.; Zirbel, C.L.; Westhof, E.; Leontis, N.B. Frequency and Isostericity of RNA Base Pairs. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37, 2294–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresson, S.; Sani, E.; Armatowska, A.; Dixon, C.; Tollervey, D. The Transcriptional and Translational Landscape of HCoV-OC43 Infection. PLOS Pathogens 2025, 21, e1012831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, D.; Mateos-Gomez, P.A.; Enjuanes, L.; Gallego, J.; Sola, I. Structure and Functional Relevance of a Transcription-Regulating Sequence Involved in Coronavirus Discontinuous RNA Synthesis. Journal of Virology 2011, 85, 4963–4973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, P.; Li, Y.; Napthine, S.; Chen, C.; Brierley, I.; Firth, A.E.; Fang, Y. An Intra-Family Conserved High-Order RNA Structure within the M ORF Is Important for Arterivirus Subgenomic RNA Accumulation and Infectious Virus Production. Journal of Virology 2025, 0, e02167–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, K.; Xie, D.; Lau, J.Y.; Shen, W.; Li, P.; Wang, D.; Zou, Z.; Shi, S.; Ren, H.; et al. In Vivo Structure and Dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA Genome. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhugiri, R.; Nguyen, H.V.; Slanina, H.; Ziebuhr, J. Alpha- and Betacoronavirus Cis-Acting RNA Elements. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2024, 79, 102483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-C.; Xia, X.-J.; Li, H.-R.; Jiang, S.-J.; Ma, Z.-Y.; Wang, X. Tandem Repeat Sequence of Duck Circovirus Serves as Downstream Sequence Element to Regulate Viral Gene Expression. Veterinary Microbiology 2019, 239, 108496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, Y.-M.; Fornek, J.; Crochet, N.; Bajwa, G.; Perwitasari, O.; Martinez-Sobrido, L.; Akira, S.; Gill, M.A.; García-Sastre, A.; Katze, M.G.; et al. Distinct RIG-I and MDA5 Signaling by RNA Viruses in Innate Immunity. J Virol 2008, 82, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehwinkel, J.; Gack, M.U. RIG-I-like Receptors: Their Regulation and Roles in RNA Sensing. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Takaoka, A. Innate Immune Recognition against SARS-CoV-2. Inflamm Regener 2023, 43, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Xie, Y.; Feng, R.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y. The Strand-Biased Transcription of SARS-CoV-2 and Unbalanced Inhibition by Remdesivir. iScience 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, H.; Liu, L. Subgenomic RNAs and Their Encoded Proteins Contribute to the Rapid Duplication of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 Progression. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Ma, Z.; Han, W.; Chang, C.; Li, Y.; Guo, X.; Zheng, Z.; Feng, Y.; Xu, L.; Zheng, H.; et al. Deletion of a 7-Amino-Acid Region in the Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Envelope Protein Induces Higher Type I and III Interferon Responses and Results in Attenuation in Vivo. J Virol 2023, 97, e0084723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-M.; Shin, E.-C. Type I and III Interferon Responses in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Exp Mol Med 2021, 53, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Xiao, F.; Hu, D.; Ge, W.; Tian, M.; Wang, W.; Pan, P.; Wu, K.; Wu, J. SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein Interacts with RIG-I and Represses RIG-Mediated IFN-β Production. Viruses 2021, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Son, J.; Gomez Castro, M.F.; Kawagishi, T.; Ren, X.; Roth, A.N.; Antia, A.; Zeng, Q.; DeVeaux, A.L.; Feng, N.; et al. Innate Immune Sensing of Rotavirus by Intestinal Epithelial Cells Leads to Diarrhea. Cell Host Microbe 2025, S1931-3128(25)00053-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Xia, H.; Zou, J.; Muruato, A.E.; Periasamy, S.; Plante, J.A.; Bopp, N.E.; Kurhade, C.; et al. A Live-Attenuated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Candidate with Accessory Protein Deletions 2022, 2022. 2022.02.14.480460.

- Gimenez-Lirola, L.G.; Zhang, J.; Carrillo-Avila, J.A.; Chen, Q.; Magtoto, R.; Poonsuk, K.; Baum, D.H.; Piñeyro, P.; Zimmerman, J. Reactivity of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Structural Proteins to Antibodies against Porcine Enteric Coronaviruses: Diagnostic Implications. J Clin Microbiol 2017, 55, 1426–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Torres, J.L.; DeDiego, M.L.; Verdiá-Báguena, C.; Jimenez-Guardeño, J.M.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Fernandez-Delgado, R.; Castaño-Rodriguez, C.; Alcaraz, A.; Torres, J.; Aguilella, V.M.; et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Envelope Protein Ion Channel Activity Promotes Virus Fitness and Pathogenesis. PLOS Pathogens 2014, 10, e1004077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Rodriguez, C.; Honrubia, J.M.; Gutiérrez-Álvarez, J.; DeDiego, M.L.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; Jimenez-Guardeño, J.M.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Fernandez-Delgado, R.; Verdia-Báguena, C.; Queralt-Martín, M.; et al. Role of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Viroporins E, 3a, and 8a in Replication and Pathogenesis. mBio 2018, 9, 10.1128–mbio.02325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, L.; Masters, P.S. The Small Envelope Protein E Is Not Essential for Murine Coronavirus Replication. Journal of Virology 2003, 77, 4597–4608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Target | Forward primers (5′-3′) | Reverse primers (5′-3′) | Probes (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| gRNA (nsp1) | TGAAGCCGTCTCATACTATTCTG | AATCCCTCAACAGTGTCAGC | FAM-TGCAATGCCGTTTCGTGTCCTTC-BHQ |

| sgmRNA-S | CTATCTACGGATAGTTAGCTC | GAACCGCCTAAAATTAGTGT | FAM- CCACAAGATGTCACCAGGTGCTCAGCT -IBFQ |

| sgmRNA-E | CTATCTACGGATAGTTAGCTC | AGGTGTGTAAACTGCGCTATTA | FAM- TCTGTGCTTCACTTGTCACCGGTTGT-IBFQ |

| sgmRNA-M | CTATCTACGGATAGTTAGCTC | TATCGTCAGTATGATATTCCATG | FAM- ATTCAAGTGAATGAAATATGTCTAACGG -IBFQ |

| sgmRNA-N | CTCTTGTCTACTCAATTCAACTAAACAGAAAC | CCAGTATCCAATTTGCTGGTCC | FAM-TCAGGATCGTGGCCGCAAAC-BHQ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).