1. Introduction

Japan faces an unprecedented super-aging society, with baby boomers reaching 75 years or older by 2025. Thus, medical and long-term nursing costs are expected to skyrocket and strain national finances. Therefore, extending healthy life expectancy is a national priority. However, the gap between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy has remained unchanged for two decades [

1].

Frailty represents a multidimensional decline in physical, mental, psychological, and social reserves [

2], and a potential condition for those who require long-term care [

3]. Appropriate intervention at or before the stage of frailty is essential to extend one’s healthy life expectancy. Therefore, individuals at high risk of progressing to frailty need to be identified at an early stage.

Obesity appears to be far from the image of frailty, but its factors such as reduced physical activity, inappropriate diet, and impaired muscle protein synthesis caused by metabolic dysfunction [

4] can still lead to frailty. If abdominal obesity is confirmed to contribute to frailty development, it would help target preventive strategies. This study aimed to test the hypothesis that abdominal obesity increases the risk of frailty incidence among community-dwelling adults in Osaka Prefecture.

2. Materials and Methods

This study surveyed community-dwelling people aged 30−79 years who responded to an annual questionnaire on frailty through the“ASMILE” [

5], a healthcare smartphone app, both in 2023 and 2024. Ethical approval for the research protocol was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Sciences and Global Education of Osaka Metropolitan University (approval number: 2022-09, approved on November 1, 2022). Participation required informed consent, in short, residents who consented to participate in this study ticked the corresponding check column after reading the explanations regarding research cooperation when registering for an ASMILE account, residents who consented to participate in this study ticked the corresponding check column.

This retrospective cohort study was conducted from February 2023 to February 2024. The questionnaire survey comprised the Kihon Checklist (KCL), which assesses frailty, and questions regarding exercise habits and frailty awareness. The KCL is a 25-item questionnaire developed by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare to screen older people who will need long-term care services soon [

6] (see the

Supplementary Materials). All 25 questions are answerable by “yes” or “no.” According to previous procedures, those who responded “yes” to at least 7 of the 25 items in the KCL were classified as frail [

7]. Participants also responded to the question about exercise habits (“Do you exercise, such as walking, at least once a week?” [yes/no]) and the question about frailty awareness (“Do you know the word frailty?” [do not know/have heard the word before/know a little/know well]). Height and weight were also identified (through self-report, included in question no. 12 of the KCL) to calculate the body mass index (BMI).

All the abovementioned responses were linked to age and sex data registered in the ASMILE account. In addition, all data were linked to the results of the Specific Health Checkup, Japan’s health examination program that primarily focuses on identifying and preventing metabolic syndrome. Alternatively, data were linked to health checkup results recorded by ASMILE users themselves in the app. Through these procedures, data on the participants’ waist circumference (WC) were acquired. All such procedures were conducted by Osaka Prefecture, and the data obtained were provided to us anonymously. ASMILE also records the daily number of steps, linking to the smartphone’s pedometer function. Step counts were extracted from the 19 days recorded during the study period; then, the average number of steps per day were calculated.

On the basis of the diagnostic criteria for abdominal obesity among Japanese individuals proposed by the International Diabetes Federation [

8], a WC ≥ 85 cm in males and a WC ≥ 90 cm in females indicated abdominal obesity.

The normal distribution of all variables was determined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Categorical variables were compared between groups by using the chi-square test, except for frailty awareness, which was examined using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient; for the consecutive variables, the unpaired t-test was used. The effect size of group differences was examined using Cohen’s d and categorized as small (d > 0.20 and < 0.50), medium (d > 0.50 and < 0.80) or large (d > 0.80). Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for frailty development were calculated using multivariate binary logistic regression. The explanatory variables entered into the model included sex (1 = male, 2 = female), abdominal obesity (1 = yes, 0 = no), exercise habits (1 = yes, 0 = no), and frailty awareness (1 = do not know, 2 = have heard the word before, 3 = know a little, 4 = know well), all coded as categorical variables. Data analyses were performed with SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), and statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 7,620 adults aged 30−79 years responded to both the 2023 and 2024 surveys. Of these surveys, WC data of the 2023 survey could be obtained from 2,962 respondents. Therefore, 2,962 responses (62.7 ± 8.8 years) were finally analyzed.

Table 1 summarizes the prevalence of abdominal obesity among the participants. Abdominal obesity was more prevalent among male participants than female participants (41.2% vs. 10.2%,

p < 0.001). In all participants, 23% presented with abdominal obesity.

In the 2023 survey, participants with abdominal obesity were older than those without (64.8 ± 8.1 years vs. 62.1 ± 9.0 years, p < 0.001, effect size Cohen’s d: 0.327). They also had greater BMI (25.5 ± 2.9 kg/m2 vs. 20.9 ± 2.3 kg/m2, p < 0.001, effect size Cohen’s d: 1.842), WC (92.4 ± 6.7 cm vs. 76.8 ± 6.7 cm, p < 0.001, effect size Cohen’s d: 2.313), and frailty prevalence (21.5% vs. 16.8%, p = 0.006). Conversely, frailty awareness was poorer in the participants with abdominal obesity than in those without (do not know/have heard the word before/know a little/know well: 19.4%/22.8%/29.6%/28.2% vs. 14.0%/18.6%/32.6%/34.8%, ρ = 0.019). The average number of steps per day or exercise habits did not significantly differ between the groups.

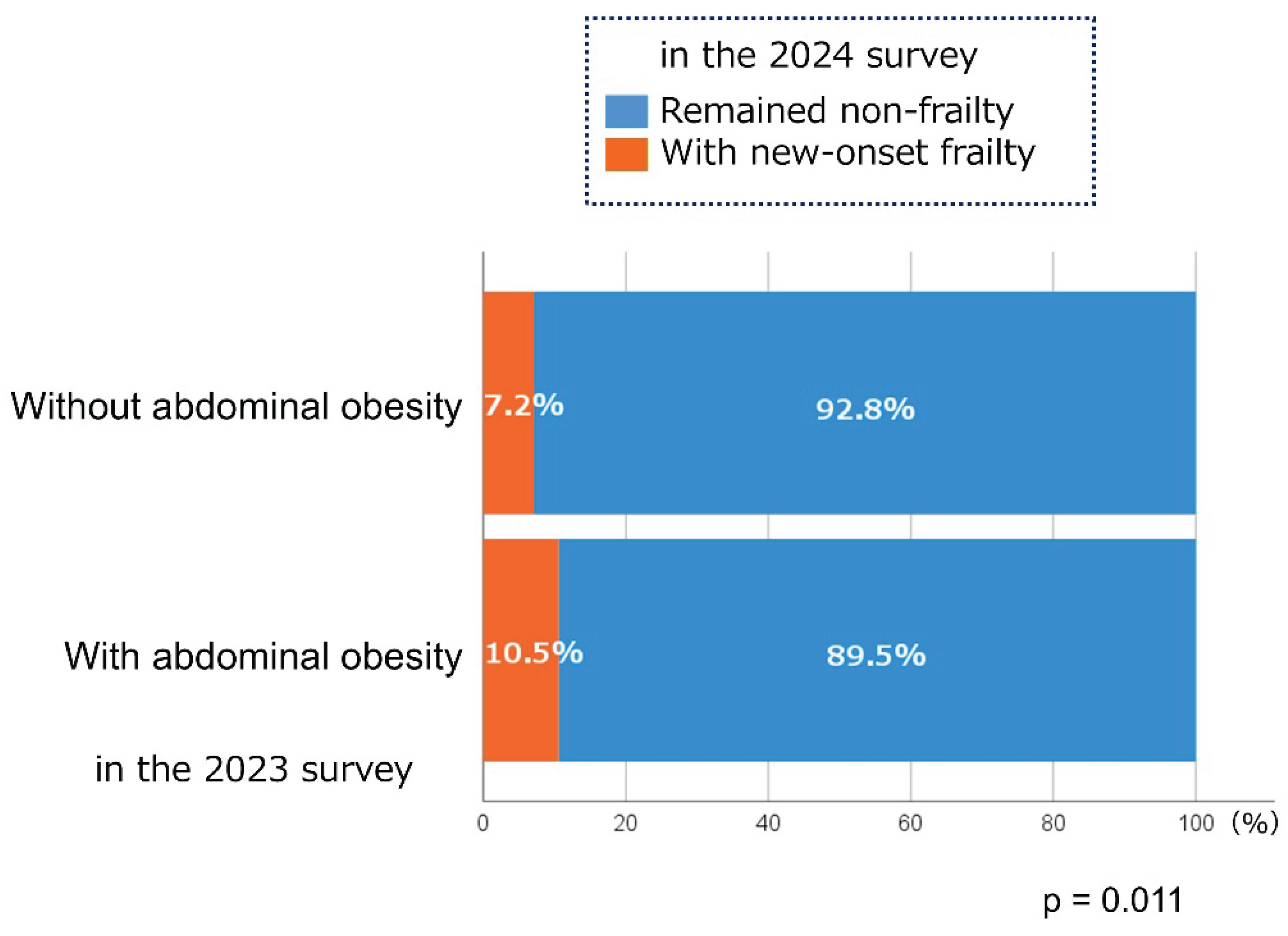

Among 2,431 participants without frailty in the 2023 survey, 7.9% developed the condition in the following year. As shown in

Figure 1, participants with abdominal obesity in the 2023 survey were more likely to develop frailty in the subsequent year than those without (10.5% vs. 7.2%,

p = 0.011). Those who developed frailty in the subsequent year were less engaged to exercise than those who did not (80.3% vs. 90.4%,

p < 0.001). This group was also less aware of frailty (do not know/have heard the word before/know a little/know well: 28.0%/26.9%/24.9%/20.2% vs. 12.3%/17.6%/32.5%/37.6%,

ρ = 0.019).

Regarding the factors associated with frailty development, as shown in

Table 2, logistic regression analysis revealed that frailty awareness (aORs relative to “do not know” were 0.685 [95% CI: 0.452–1.040], 0.360 [95% CI: 0.235–0.550], and 0.257 [95% CI: 0.164–0.405] in “have heard the word before,” “know a little,” and “know well,” respectively) and exercise habits (aOR: 0.480; 95% CI: 0.319–0.720) were significant explanatory variables for frailty development in the subsequent year. Meanwhile, abdominal obesity was not an independent contributor to frailty development in the subsequent year.

4. Discussion

In this study, the proportion of participants who progressed to frailty in the subsequent year was slightly but significantly higher in those with abdominal obesity than in those without. Therefore, those with abdominal obesity should be targeted for frailty preventive measures. However, in our logistic regression analysis, while low awareness of frailty and lack of exercise habits independently contributed to frailty development in the subsequent year, abdominal obesity was not a significant explanatory factor. Thus, at least in a short follow-up period of one year, even if the individuals have abdominal obesity, the impact of abdominal obesity on progression to frailty may be offset if they have knowledge of frailty and exhibit behavioral changes such as developing an exercise habit. Therefore, individuals with abdominal obesity should not only be encouraged to lose weight through an appropriate diet but also gain information about frailty and learn ways to increase exercise time to address the public health issue on frailty.

A previous prospective cohort study showed that visceral obesity and insulin resistance are associated with frailty development [

9], and the results of this study are consistent with its findings. Increased visceral fat induced by inappropriate nutrition and decreased physical activity is accompanied with fat accumulation in skeletal muscle cells, enhancing the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines and the invasion of macrophages into the adipose tissue [

10]. Thus, obesity is not only a metabolic disorder but also a pathological condition of chronic inflammation. These mechanisms can impair the skeletal muscle anabolism, inducing sarcopenia.

According to the results of the 2019 National Health and Nutrition Survey, the percentage of people with abdominal obesity was 45.0% for males aged 30−39 years and approximately 60% for those in their 40s to 70s. As for females, the percentage of those with abdominal obesity increased with age, with approximately 25% of those in their 60s to 70s obtaining abdominal obesity [

11]. In this study, males had a higher percentage of abdominal obesity cases than females, but the percentages of both sexes were lower than that of the national average. In addition to the bias in the number of participants among age groups, this study targeted users who had ASMILE accounts and who had recorded health checkup results themselves in the app, or who linked their Specific Health Checkup results to the app. Therefore, our participants might have been originally health-conscious, and the results should be interpreted with caution. Further research is needed to elucidate whether abdominal obesity also affects frailty development in populations with a high prevalence of obesity.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study indicate the importance of identifying targets to intervene to prevent progression to frailty by using simple, noninvasive tests such as measuring the WC, and actively providing health guidance. In addition, acquiring knowledge about frailty may lead to behavioral changes that help prevent frailty. Therefore, raising awareness of frailty among different age groups is an urgent issue that we need to address.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Table S1: The Kihon Checklist.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Sciences and Global Education of Osaka Metropolitan University approved the research protocol (approval number: 2022-09, approved on Nov 1, 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all ASMILE users who cooperated with this survey, as well as Osaka Prefecture, which is the main body implementing this survey. We would also like to thank all the Osaka Prefecture employees for their cooperation in data acquisition.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Average life expectancy and healthy life expectancy. Available online: https://kennet.mhlw.go.jp/information/information/hale/h-01-002 (accessed on Sep 8 2025).

- Hoogendijk, E.O.; Afilalo, J.; Ensrud, K.E.; Kowal, P.; Onder, G.; Fried, L.P. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet. 2019, 394, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Honda, T.; Narazaki, K.; Chen, T.; Kishimoto, H.; Kumagai, S. Physical Frailty and Risk of Needing Long-Term Care in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: a 6-Year Prospective Study in Japan. J Nutr Health Aging. 2019, 23, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beals, J.W.; Burd, N.A.; Moore, D.R.; van Vliet, S. Obesity Alters the Muscle Protein Synthetic Response to Nutrition and Exercise. Front Nutr. 2019, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osaka Prefecture's health app "ASMILE". Available online: https://www.asmile.pref.osaka.jp (accessed on Jan 18 2024).

- Manual on daily-living function assessment for long-term care prevention (Revised edition). Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/2009/05/dl/tp0501-1c_0001.pdf (accessed on Jan 23 2024).

- Yamaguchi, M.; Yoshida, T.; Yamada, Y.; Watanabe, Y.; Nanri, H.; Yokoyama, K.; Date, H.; Miyake, M.; Itoi, A.; Yamagata, E.; et al. Sociodemographic and physical predictors of non-participation in community based physical checkup among older neighbors: a case-control study from the Kyoto-Kameoka longitudinal study, Japan. BMC Public Health. 2018, 18, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, K.G.; Zimmet, P.; Shaw, J.; I. D. F. Epidemiology Task Force Consensus Group. The metabolic syndrome--a new worldwide definition. Lancet. 2005, 366, 1059–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Tasigchana, R.F.; Leon-Munoz, L.M.; Lopez-Garcia, E.; Gutierrez-Fisac, J.L.; Laclaustra, M.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F.; Guallar-Castillon, P. Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance are associated with frailty in older adults: a prospective cohort study. Age Ageing. 2017, 46, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.C.; Ki, S.W.; Kim, H.; Kang, S.; Kim, H.; Go, G.W. Recent Advances in Nutraceuticals for the Treatment of Sarcopenic Obesity. Nutrients. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Nutrition Survey Waist Circumference Distribution - Waist Circumference Classification. Available online: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/dbview?sid=0003234716 (accessed on Dec 2 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).