1. Introduction

The term ‘heavy metals’ (HMs) is often used for metals and metalloids whose density in the pure elemental state exceeds 5 g/cm

3. Some of these elements are essential micronutrients, showing toxicity at concentrations exceeding the tolerance range of a given species, while the other do not play any positive role in biochemistry [

1]. HM ions are released into the environment as a result of natural processes and anthropogenic activities. Due to rapid industrialisation, in recent centuries HMs have become the main environmental pollutants [

1]. HMs toxicity is a complex phenomenon due to the pleiotropic effects they exert on living cells. The most common mechanism of toxicity is due to the similarity of given HM ions to essential metal ions, resulting in the substitution of the latter in their binding sites in proteins and other compounds of biological importance, such as chlorophyll (Chl), as well as in competition for transport systems leading to a shortage of nutrients and a disturbance of ion and water homeostasis [

2]. Highly toxic HM ions often display high affinity for crucial chemical groups. These are mainly thioyl but also histidyl and carboxyl groups of proteins and low-molecular-weight compounds, such as glutathione (GSH) [

3,

4]. The ions of the so-called redox-active HMs undergo a redox cycling in cells that leads to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [

5]. However, an increase in ROS formation may also occur in response to redox-inactive HMs, as a result of general disturbance of cellular metabolism and malfunctioning of ROS-detoxifying processes [

2].

Among HMs, cobalt (Co) has been less examined in terms of its toxicity and tolerance in algae compared to Cd, Pb, Cu, Cr, or Ni [

2]. This element naturally occurs in the Earth’s crust minerals [

6]. Among the important anthropogenic sources of Co are Cu and Ni smelting and refining, alloy manufacturing, battery production, cement industry, pigments and paints, fossil fuel combustion, industrial waste, and agricultural use of phosphate fertilisers [

7,

8]. In many organisms Co is a micronutrient, present in the cobalamin ring of B

12, and in the enzymes nitrile hydratases [

6]. However, it also displays toxicity, which was postulated to be the result of competitive interactions with other metal ions [

9]. In higher plants, excessive Co was observed to cause growth inhibition, disturbed transport of other nutrients (P, S, Cu, Zn, Mn), as well as decrease in Fe content and chlorophyll (Chl) content [

1]. The application of higher Co concentrations resulted in inhibition of important enzymes, i.e. nitrate reductase, photosystem II (PSII), and phosphoenol pyruvate carboxylase. Excess Co has also been shown to inhibit RNA synthesis and disturb mitotic spindle formation [

10].

Inhibition of enzymes and disturbance of nutrient homeostasis can result in enhanced ROS formation in Co-exposed cells and the occurrence of oxidative stress. Indeed, enhanced lipid peroxidation was observed in the haptophyte

Pavlova viridis and in green microalgae

Scenedesmus sp. and

Chlorella sp. treated with excessive CoCl

2 [

11,

12]. Living organisms have evolved several mechanisms of antioxidant defence [

13]. Among them, the most important are low-molecular-weight antioxidants, both hydrophilic and hydrophobic, as well as ROS-detoxifying enzymes. Among the hydrophilic antioxidants, very important ones are GSH and other soluble thiols, and ascorbate (Asc). Free proline (Pro) is known for its osmo-protective function, but it also displays antioxidant action [

2]. On the other hand, lipophilic antioxidants, such as tocopherols (Toc), prenylquinols, and carotenoids, are crucial for the protection of membranes and storage lipids [

14]. Antioxidant enzymes include superoxide dismutases (SOD), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), catalase (CAT), GSH peroxidase, and various other enzymes, including those participating in Asc and GSH recycling [

2].

Organisms also have mechanisms aimed at preventing ROS formation. In photosynthetic cells under illumination, the main source of ROS is photosynthesis, due to the photooxidative action of Chl and the electron leakage from the photosynthetic electron transfer chain. Therefore, an important protective mechanism is based on the dissipation of excessive energy absorbed by the photosynthetic apparatus. It prevents prolonged excitation of Chl, decreasing the chance of unwanted energy transfer to

3O

2 and formation of harmful

1O

2. It also prevents overreduction of the photosynthetic electron transfer chain and the resulting electron leakage and O

2∙- formation [

15,

16]. In

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, the key photoprotective mechanism of quenching of excited states of Chl depends on the light-harvesting complex stress-related (LHCSR) proteins [

17].

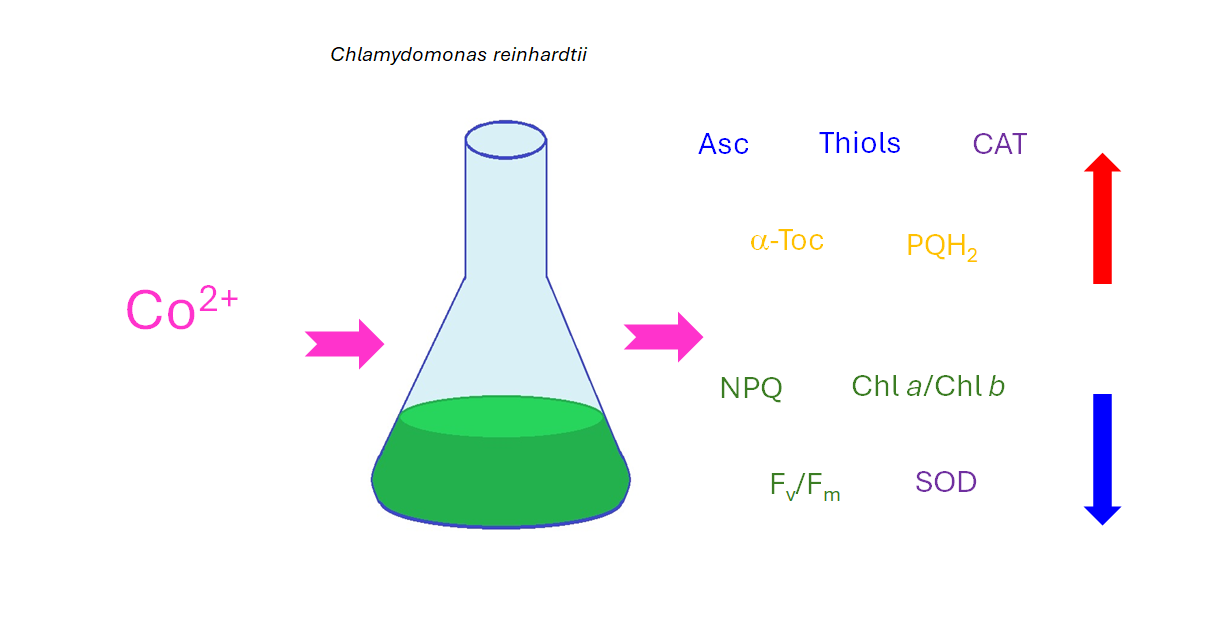

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the impact of toxic concentrations of CoCl

2 on the growth, photosynthetic pigment content, selected photosynthesis-related parameters (maximum quantum yield of PSII and the efficiency of non-photochemical quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence), oxidative stress markers (O

2∙- formation and the content of lipid hydroperoxides, LOOHs), hydrophilic antioxidants (soluble thiols, Asc, Pro), lipophilic antioxidants (α-Tocopherol, α-Toc, and plastoquinol, PQH

2), and ROS-detoxifying enzymes (SOD, CAT, APX), in model green microalgae

C. reinhardtii, widely used in research on HMs toxicity and tolerance [

18].

2. Results

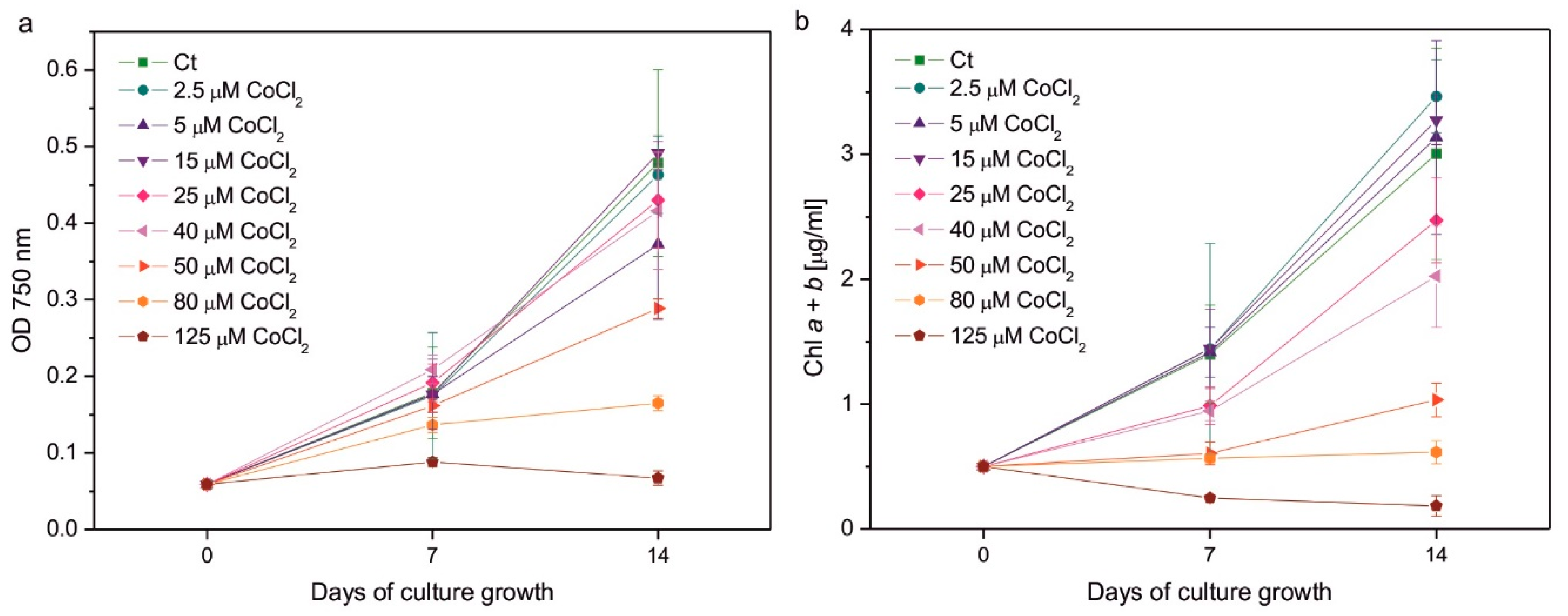

As expected, excessive Co had a negative impact on algal growth (

Figure 1a) and Chl content (

Figure 1b). Considering measurements of OD at λ = 750 nm, which results can be related to the number of cells in the culture, the effect of Co addition was less pronounced after 1 week of growth than after 2 weeks. In 7-day-old cultures, the statistically significant decrease in OD compared to control was observed only for the series with the highest applied CoCl

2 concentration, that is, 125 µM, whereas in 14-day-old cultures it was observed in algae exposed to 80 and 125 µM CoCl

2. The growth of the culture containing 50 µM CoCl

2 was slightly slower compared to the control, but the effect did not turn out to be statistically significant (

Figure 1a). The inhibitory impact of CoCl

2 on Chl content in algal cultures was more pronounced than the impact on culture growth. After 1 week, a statistically significant decrease in the Chl

a +

b content was observed for the series with 50, 80, and 125 µM CoCl

2, while after 2 weeks it was observed for the series with 40, 50, 80, and 125 µM CoCl

2. Slight but statistically insignificant inhibition was observed in algae exposed to 25 µM CoCl

2 (

Figure 1b). The highest concentration of CoCl

2 applied completely inhibited the growth of the culture and caused a decrease in the Chl

a +

b content in the exposed algae (

Figure 1).

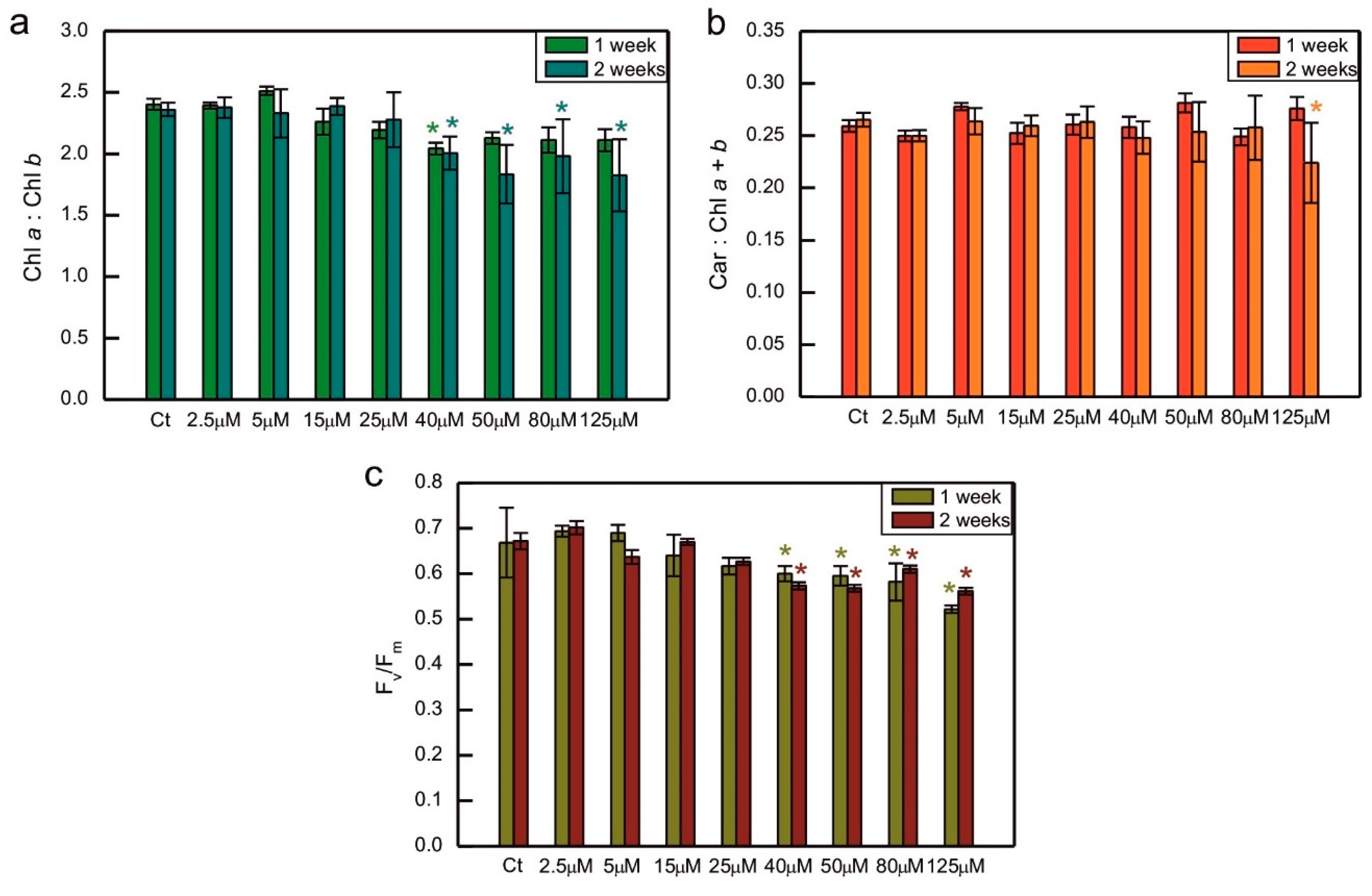

The ratio of Chl

a to Chl

b was decreased compared to the control in algae exposed to 40 µM CoCl

2 both after 1 and 2 weeks of growth, and in 2-week-old cultures treated with 50, 80, and 125 µM CoCl

2 (

Figure 2a). A similar trend, that is a decrease in the series exposed to 40, 50, 80, and 125 µM CoCl

2, when compared to the control, was observed for the maximum quantum yield of PS II. This time the differences between all the above mentioned series and control were statistically significant after 1 and 2 weeks of growth (

Figure 2c). Exposure to CoCl

2 did not cause changes in the total carotenoids to total Chl ratio, except for the series with the highest CoCl

2 concentration applied measured after 2 weeks of exposure, where the decrease could be seen, compared to the control (

Figure 2b).

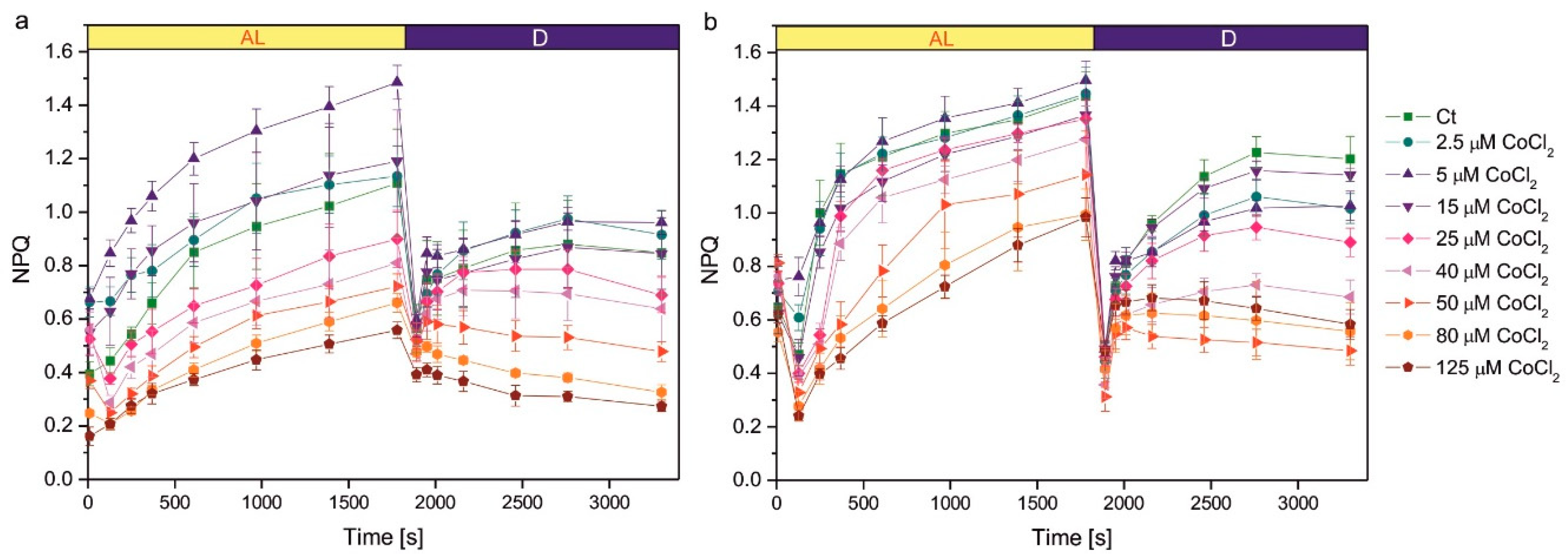

Growth in the presence of CoCl

2 had an impact on the induction of NPQ (

Figure 3). The NPQ parameter measured during actinic light exposure reflects photoprotective mechanisms of non-photochemical quenching of Chl fluorescence, mainly the qE component, induced by ΔpH gradient across thylakoid membranes. The increase in the NPQ parameter in darkness is due to the induction of chlororespiration and the transition from state 1 to state 2, leading to a decrease in the efficiency of energy transfer from LHCII antennae to PSII [

19]. In the 1-week-old culture, the series exposed to 5 µM CoCl

2 showed more efficient NPQ induction during actinic light exposure compared to the control, but this effect was not observed in the 2-week-old culture (

Figure 3). Exposure to higher concentrations of CoCl

2 resulted in a decreased efficiency of NPQ induction. A statistically significant decrease in NPQ was observed compared to the control for CoCl

2 concentrations 40 µM and higher in 1-week-old cultures and for concentrations 50 µM and higher in 2-week-old cultures (

Figure 3). The decreased NPQ in darkness, compared to control, was observed for CoCl

2 concentrations of 50 µM and higher in 1-week-old cultures and for concentrations 25 µM and higher in 2-week-old cultures (

Figure 3).

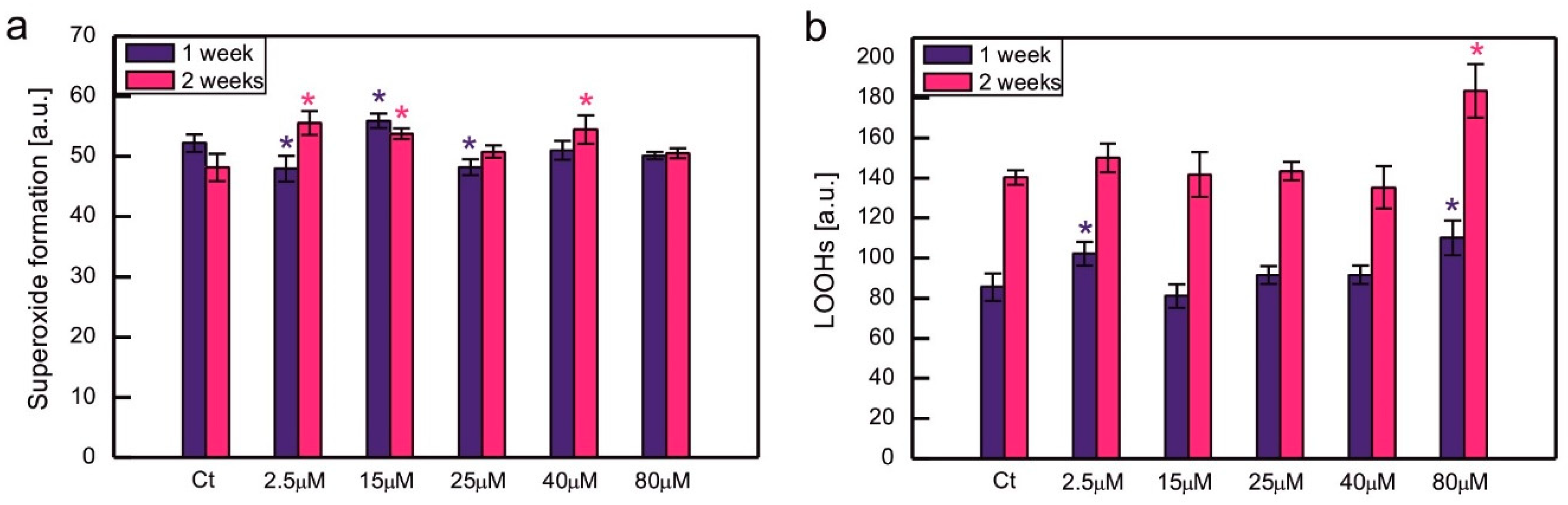

Oxidative stress markers were measured for series selected among those mentioned above, as indicated in

Figure 4. In some series exposed to excessive CoCl

2, the formation of O

2-• was slightly increased or decreased compared to control, but no clear trend could be observed, suggesting that there was no dose-dependent increase in O

2-• formation in Co-exposed algae (

Figure 4a). The content of LOOHs increased compared to the control in

C. reinhardtii exposed to 80 µM CoCl

2. For each series, there was a statistically significant increase in LOOHs content during culture growth (

Figure 4b, significance of differences between weeks 1 and 2 not marked on the plots).

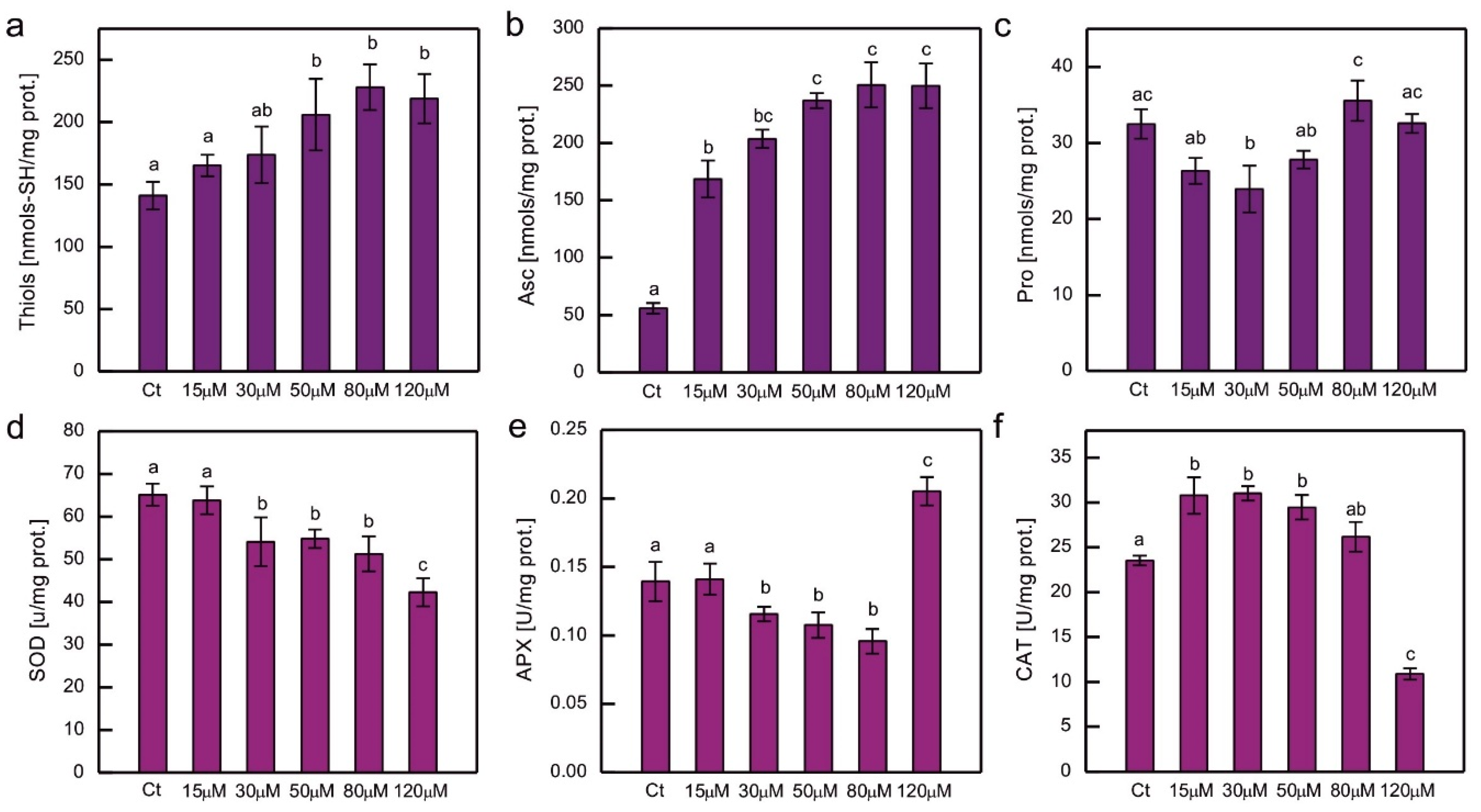

The content of chosen hydrophilic low-molecular-weight antioxidants and the activity of the major ROS-detoxifying enzymes were measured in cultures of

C. reinhardtii exposed to CoCl

2 after 2 weeks (

Figure 5). Exposure to excessive Co resulted in an increase in low-molecular thiols and Asc, and this increase was clearly dose-dependent (

Figure 5a, b). In the case of soluble thiols the increase was approximately 50% compared to the control, while in the case of Asc it was much higher (up to 4.5 times more Asc compared to the control), and the pronounced increase (about 3-fold) was observed for the lowest CoCl

2 concentration tested in the experiment, that is, 15 µM (

Figure 5a, b). The protocol used enabled the evaluation of dehydroascorbate (DHA), which is a stable product of Asc oxidation, but in all the series there were only trace amounts of DHA (results not shown). No increase in Pro content was observed in Co-exposed

C. reinhardtii (

Figure 5c).

Taking into account the response to Co in terms of antioxidant enzyme activity, a dose-dependent decrease was observed for SOD activity for the entire range of CoCl

2 concentrations tested (

Figure 5d), while for APX, it was observed for CoCl

2 concentrations ranging from 15 to 80 µM. In algae exposed to 120 µM CoCl

2 the activity of APX increased by about 50% compared to the control (

Figure 5e). On the other hand, CAT activity increased, by approximately 30%, in cultures exposed to lower CoCl

2 concentrations (15, 30, 50 µM), and decreased by approximately 55% in algae exposed to 120 µM CoCl

2, compared to the control (

Figure 5f).

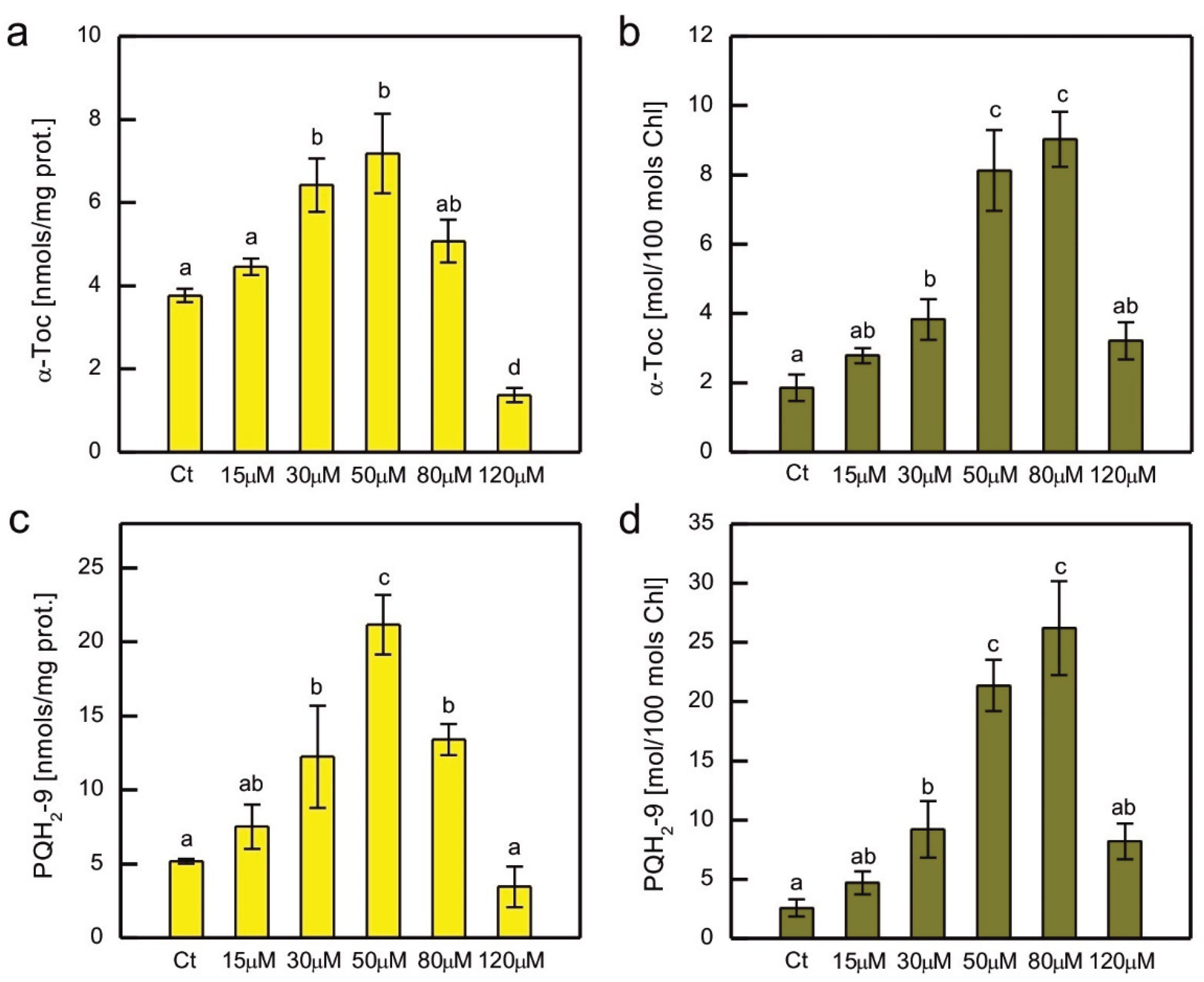

In addition to hydrophilic antioxidants, the content of the major lipophilic antioxidants, α-tocopherol (α-Toc) and plastoquinol-9 (PQH

2-9) was also measured in Co-exposed

C. reinhardtii (

Figure 6). As these compounds are localised in plastids, where they play a crucial role in the protection of the thylakoid membrane against lipid peroxidation, their content was normalised both to total soluble protein content and total Chl content. A clear dose-dependent pattern was observed for both compounds, regardless of the normalisation method, i.e., an increase for the lower CoCl

2 concentrations applied, then a decrease for the higher ones (

Figure 6). The increase in content was more pronounced for PQH

2-9 compared to α-Toc, but apart from that, both compounds showed similar patterns of changes. When the prenyllipid content was normalised to total soluble proteins, a progressive increase with increasing CoCl

2 concentration in the medium was observed in the range of 15-50 µM. Higher CoCl

2 concentrations resulted in a progressive decrease in prenyllipid content (

Figure 6a, c). When prenyllipid content was normalised to Chl content, an increase was observed in the range of 15-80 µM CoCl

2 (

Figure 6b, d). The applied HPLC method allowed measuring of other isoprenoid chromanols occurring in plastids, i.e. γ-tocopherol (γ-Toc) and plastochromanol-8 (PC-8), as well as the oxidised form of PQH

2-9, plastoquinone-9 (PQ-9). However, the amounts of γ-Toc and PC-8 were several times lower than the amount of α-Toc, and the observed trends were similar to those observed for α-Toc, therefore they were not shown. The PQ-9 content constituted only a few percent of the total PQ pool (PQ + PQH

2) and did not change much in the Co-exposed algae compared to control, therefore these results were not shown either.

3. Discussion

The inhibitory effect of HM ions on growth and Chl accumulation in photosynthetic organisms is a well-known phenomenon [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. This effect was observed in

C. reinhardtii exposed to HMs, such as Cd, Cr, Cu, Hg, Ni, or Pb [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. Co ions were shown to inhibit the growth of green microalgae

Chlorella vulgaris,

Scenedesmus obliquus,

C. reinhardtii, diatoms

Phaeodactylum tricornutum,

Nitzschia perminuta, Selenastrum capricornutum (

Raphidocelis subcapitata), and haptophyte

P. viridis [

12,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. The Chl content was decreased in Co-exposed

Chlorella and

Scenedesmus sp. [

11]. Experiments in which both algal growth and Chl content were monitored confirmed the inhibitory effect of Co ions on

Chlorella pyrenoidosa, Monoraphidium minutum, S. capricornutum, and

N. perminuta [

45,

46,

47]. Our previous experiments showed that the negative impact of tested HMs on Chl content in

C. reinhardtii cultures was usually more pronounced than the impact on their OD [

33,

34,

35]. This effect was also observed in the case of Co exposure (

Figure 1). In contrast, in the haptophyte

P. viridis exposed to 10, 20 and 50 μM CoCl

2, the growth was inhibited, but the Chl

a content normalised to cell number increased compared to the control [

12]. In our experiment, the differences in cell numbers and Chl content between the control and Co-exposed series increased during culture growth (

Figure 1). Such an effect was observed also in Co-exposed

C. pyrenoidosa,

C. reinhardtii,

R. subcapitata, Chlorella sp., and

Scenedesmus sp. [

11,

41,

44,

45]. This is similar to the response of

C. reinhardtii to Cd and Cr observed in our previous experiments [

33]. On the other hand,

C. reinhardtii treated with Cu ions seemed to acclimate to this HM during culture growth [

33,

35].

Considering the effect of HM ions on total Chl level and the ratio of Chl

a to Chl

b, it is known that HMs are capable of inhibiting the biosynthesis of these pigments [

48], replacing Mg

2+ in their molecules [

49], and causing Chl degradation through oxidation [

20] and pheophytinization [

37,

50]. The inhibitory action of Co on Chl biosynthesis has been described in the literature [

51]. Taking into account the substitution of Mg

2+ by HMs, Chl

a turned out to be more susceptible to this process than Chl

b [

50]. It was also hypothesised that during stress evoked by HMs, Chl

a could be non-enzymatically oxidised to Chl

b [

52]. Both of the above-mentioned effects would result in a decrease in Chl

a/Chl

b ratio, often observed in photosynthetic organisms treated with HMs [

20,

32,

52]. In the present experiment, the decrease in Chl

a/Chl

b ratio was correlated with a general decrease in total Chl content compared to control (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2a).

An increase in carotenoid content was observed in some experiments with algae treated with HMs [

2]. For example, an increase in carotenoids to Chl ratio occurred in Cd- and Cr-exposed

C. reinhardtii [

34], Cu- and Cr- exposed

C. vulgaris [

53,

54], Cu-exposed

Dunalliella salina and

Dunaliella tertiolecta [

55], and Ni-exposed

Dunaliella sp. [

56]. An increase in carotenoids to Chl

a ratio was observed in Co-exposed diatom

N. perminuta [

46]. However, in our experiment no such effect was observed, i.e. carotenoids to Chl ratio remained rather stable, except for the 2-week-old series with the highest CoCl

2 concentration applied, where the decrease in this ratio suggested enhanced degradation of carotenoid pigments (

Figure 2b). It could be hypothesised that in our model accumulation of carotenoids did not play a key role during acclimation to Co exposure.

The decrease in maximum quantum yield of PS II in response to HMs was observed in some experiments, for example in spinach-derived thylakoids exposed to Cu, Hg, and Pb ions [

57], as well as Pb-exposed

Nitzschia closterium and

C. reinhardtii [

30,

58]. However, in other models no decrease in this parameter was observed in response to HMs. No differences were observed between control series and

C. reinhardtii grown in the presence of Cu, Cd, Cr, Hg, and Ag ions [

33]. In the case of exposure to Co, a dose-dependent decrease in the F

v/F

m parameter was demonstrated for

S. capricornutum [

44,

47]. This effect was also observed in our experiment, where a decrease in F

v/F

m was well correlated with the decrease in total Chl content and Chl

a/Chl

b ratio in Co-exposed algae, suggesting damage to the photosynthetic apparatus (

Figures 1, 2a and c).

The improvement in the efficiency of nonphotochemical quenching of Chl fluorescence was observed in

C. reinhardtii acclimated to Cu, Cd, and Cr ions compared to the control [

33], and in the Cu-tolerant strain of

C. reinhardtii compared to the non-tolerant strain [

59]. We wanted to check if such an effect occurs in

C. reinhardtii acclimated to Co, but enhanced NPQ induction compared to control was observed only for a 1-week-old culture exposed to 5 μM CoCl

2 (

Figure 3). In cultures grown in the presence of CoCl

2 concentrations that cause inhibition of Chl accumulation in cultures, as well as decrease in both Chl

a/Chl

b ratio and the maximum quantum yield of PSII, the decrease in the efficiency of NPQ could be seen, suggesting overall malfunctioning of the photosynthetic apparatus and its regulatory mechanisms. It may be speculated that the decrease in the photoprotective mechanisms would result in PSII damage and the decrease in the Chl

a content. A decrease in NPQ efficiency was also observed in Co-exposed

S. capricornutum [

47]. An interesting and new observation is the change in response of the NPQ parameter in darkness in cultures exposed to high CoCl

2 concentrations compared to control (

Figure 3). It suggests that Co may inhibit chlororespiration or inhibit

stt7 kinase responsible for state transitions in

C. reinhardtii. This topic requires further studies.

The enhancement of ROS production is often observed in photosynthetic organisms suffering from HM-induced stress. There are robust data from the literature that confirm an increase in various markers of oxidative stress in algae exposed to HM ions [

2]. Taking into account

C. reinhardtii, an increase in thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), which are markers of lipid peroxidation, was observed in response to Hg, Cu, and Ni [

26,

31,

32,

35,

38,

60,

61]. An increase in O

2-• formation occurred in

C. reinhardtii growing in the presence of Cd and Cr ions [

34]. Exposure to Co led to an increase in TBARS in

P. viridis,

Scenedesmus sp., and

Chlorella sp. [

11,

12]. On the other hand, in

S. capricornutum ROS production, measured fluorometrically, increased only in the series exposed to 0.5 mg Co (applied as CoCl

2) dm

-3, while there were no statistically significant differences between the control and the series containing 0.1, 0.25, and 0.75 mg Co dm

-3 [

44]. In the present experiment, the formation of O

2-• in Co-exposed

C. reinhardtii was similar to the control (

Figure 4a), suggesting efficient protection against this type of ROS for a tested range of CoCl

2 concentrations. Taking into account lipid peroxidation, an increase in the amount of LOOHs was observed compared to the control in the series with 80 μM CoCl

2, the concentration for which significant growth inhibition occurred (a and

Figure 4b). It suggests that severe poisoning with Co ions led to the exhaustion of antioxidant protection, resulting in the progress of lipid peroxidation.

The antioxidant response to HM-induced stress has been the subject of intensive research. An enhancement of antioxidant protection is often observed in organisms exposed to HMs, although there are no universal trends. The antioxidant response depends on many factors, i.e. HM type and concentration applied, the timing of dosage, culture conditions, species examined, internal concentration of HM ions, sometimes even the type of salt used in the experiment (for example sulphate

vs. chloride). The relatively common type of response is an increase in the antioxidant examined for lower doses of HM salt and a decrease for higher concentrations applied [

2]. This pattern was observed for APX, SOD, and CAT activity in Hg-exposed

C. reinhardtii [

26]. The activity of the enzymes mentioned above was also increased in 1-week-old

C. reinhardtii exposed to 20 μM CuSO

4, which was correlated with the appearance of symptoms of oxidative stress in these algae [

35]. An increase in APX activity was observed in Cr- and Cd-treated

C. reinhardtii, while CAT activity was increased only in algae exposed to Cd, and SOD activity increased in series with Cr ions and decreased in series with Cd ions [

34]. The decrease in SOD activity in response to Cd may be attributed to the inhibitory action of Cd

2+ on this enzyme due to the replacement of Zn

2+ ions in Cu/Zn SOD [

49]. Dose-dependent increase in SOD and CAT activity was observed in Co-exposed

Chlorella and

Scenedesmus sp. [

11]. A dose-dependent increase in CAT, but not in SOD activity was observed in

P. viridis. In the study on the

P. viridis, GSH peroxidase activity was also shown to increase in Co-exposed cells [

12]. On the other hand, a dose-dependent decrease in SOD and CAT activity has been reported in Co-exposed

C. pyrenoidosa [

45]. In the present experiment, exposure to Co led to a dose-dependent decrease in SOD activity, suggesting the inhibitory action of Co

2+ on SOD activity in our model (

Figure 5d). CAT activity was enhanced in Co-exposed algae, except for the highest CoCl

2 concentration applied (

Figure 5f). It could be speculated that in cells exposed to such severe stress, CAT molecules were damaged. It is known that CAT may be inhibited by peroxyradicals [

62], and we observed an increase in lipid peroxidation in the series with the high dose of CoCl

2 in our model. APX activity decreased for the lower CoCl

2 concentrations applied and increased for the highest (

Figure 5e). It may be hypothesised that in the severely affected culture, the expression of the APX-encoding gene was increased, perhaps in an attempt to compensate for the decrease in plastid prenyllipid antioxidants, because APX in

Chlamydomonas is targeted at plastids and mitochondria [

63].

Hydrophilic low-molecular-weight antioxidants are important for protection against HM-induced stress. The amount of soluble thiols increased in Hg-, Cr-, Cd-, and Ni-exposed

C. reinhardtii [

34,

38,

64], Cu-exposed

Scenedesmus bijugatus [

65], Cu-, Ni-, and Zn-exposed

S. capricornutum [

66], and in Cr-exposed

Monoraphidium convolutum [

67]. Exposure to Co was shown to cause an increase in the GSH content in

P. viridis [

12]. HM treatment also led to an increase in Asc level, for example in Cd-, Cr-, and Cu-exposed

C. reinhardtii [

34,

35], as well as in Cu-, and Zn-exposed

Chlorella sorokiniana and

Scenedesmus acuminatus [

68,

69]. The Pro content was increased in Hg-, Cu-, Cd-, Cr-, and Ni-exposed

C. reinhardtii [

34,

38,

60,

70], Cd-, and Cu-exposed

Chlorella sp. [

71], Cu-, Ni-, and Zn-exposed

C. vulgaris [

53,

72], Cu-exposed

C. sorokiniana and

S. acuminatus [

69], Zn-exposed

S. acuminatus [

68], Pb-exposed

Scenedesmus obliquus [

73], as well as in Cu-, and Zn-exposed

Scenedesmus sp. [

74]. In the present experiment, we observed a significant dose-dependent increase in soluble thiols and Asc, suggesting that these compounds play an important protective role in Co-induced stress in

C. reinhardtii, whereas no such trend was observed for Pro (

Figure 5a,b,c).

Prenyllipid antioxidants localised in plastids, tocopherols and PQH

2, turned out to be an important player in antioxidant protection in photosynthetic organisms [

14]. An increase in α-Toc content was observed in Cu-, Cd-, and Cr-exposed

C. reinhardtii [

32,

33,

34], Cu-, and Zn-exposed

C. sorokiniana and

S. acuminatus [

68,

69], as well as in Cu-, and Cd-exposed

Arabidopsis thaliana [

75]. The level of PQH

2 increased in

C. reinhardtii in response to Cr, Cd, and Hg ions [

33,

34]. Furthermore, Cu-tolerant strains of

C. reinhardti, obtained as a result of prolonged growth in media with increased Cu content, contained more α-Toc and PQH

2 than non-tolerant parent strain [

59]. In our experiment, a dose-dependent increase in the content of these prenyllipids was also observed, suggesting that these antioxidants are important for the protection of

C. reinhardtii during Co-induced stress (

Figure 6). The decrease in α-Toc and PQH

2 for the highest CoCl

2 concentrations tested shows the exhaustion of protective mechanisms and can be correlated with the progress of lipid peroxidation and severe inhibition of growth (

Figure 1a, 4b).

4. Materials and Methods

The

C. reinhardtii strain used in the present study was 11-32b (SAG collection

, Göttingen, Germany). For the sake of the experiments, algae were inoculated to provide an initial Chl

a +

b concentration of 0.5 μg/ml, and grown for 2 weeks under continuous white light (50 μmol photons m

−2 s

−1), at 22°C, on the shaker, as described in [

70], in triplicates. Modified Sager-Granick medium: 3.75 mM NH

4NO

3, 1.22 mM MgSO

4·7H

2O, 0.73 mM KH

2PO

4, 0.57 mM K

2HPO

4, 0.36 mM CaCl

2·2H

2O, 37 μM FeCl

3, 16.2 μM H

3BO

4, 0.84 μM CoCl

2·6H

2O, 0.24 μM CuSO

4·5H

2O, 2.02 μM MnCl

2·4H

2O, 0.83 μM (NH

4)

6Mo

7O

24·4H

2O, 3.5 μM ZnSO

4·7H

2O, 5 mM HEPES pH 6.8 [

33] was used in control series and as a basis for the media containing excessive Co. The latter were obtained by adding certain volumes of 50 mM CoCl

2·6H

2O. The concentrations of CoCl

2 applied were selected on the basis of preliminary experiments, where a wide range of concentrations was tested. In the experiment in which the growth of the culture, the content of photosynthetic pigments, and the chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were assessed, 2.5, 5, 15, 25, 40, 50, 80, and 125 µM CoCl

2 were applied. Among the series mentioned above, cultures containing 2.5, 15, 25, 40, and 80 µM CoCl

2 were also used to determine markers of oxidative stress. All measurements were carried out after 1 and 2 weeks of culture growth. In the experiment on antioxidant response, the applied CoCl

2 concentrations were 15, 30, 50, 80, 120 µM, and the samples were collected after 2 weeks of growth.

Algal growth was monitored as OD at λ = 750 nm. Photosynthetic pigments were extracted with acetone as described in [

34] and determined spectrophotometrically according to Lichtenthaler [

76].

Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, that is, maximum quantum yield of PSII photochemistry (F

v/F

m), and non-photochemical quenching (NPQ), calculated as (F

m − F

m’)/F

m’ (where F

m is maximum fluorescence in dark-adapted state, while F

m’ is maximum fluorescence in algae exposed to actinic light), were measured using Open FluorCam FC 800-O (Photon Systems Instruments, Brno, Czech Republic) as described in [

33,

34]. Before measurements, algal suspensions were thickened to provide total Chl concentrations 5 μg/ml and portioned into 48-well plate. The induction of NPQ was measured during 30 min of illumination with red actinic light of intensity of 200 μmol photons m

-2 s

-1. The saturating pulses (white light of intensity 2700 μmol photons m

-2 s

-1) were applied as indicated in the figures.

Lipid hydroperoxides were measured using the fluorescent probe Spy-LHP, 2-(4-diphenylphosphanyl-phenyl)-9-(1-hexyl-heptyl)-anthra(2,1,9-def,6,5,10-d’e’f’)-diisoquinoline-1,3,8,10-tetraone (Dojindo, Japan) as described in [

33]. Shortly: acetone stock solution of the probe was added to ethanol extract obtained of algal pellets to provide the final concentration of the probe, 10 µM; samples were then incubated for 10 min in the dark, centrifuged (5 min, 9 000 g), and the fluorescence spectrum was measured at λ

ex = 465 nm, emission range 500 – 600 nm. Cumulative O

2-• production in

C. reinhardtii cells was analysed using

in vivo nitrotetrazolium blue (NBT) staining as described in [

70].

The selected hydrophilic antioxidants, i.e. Asc, soluble thiols, and Pro, as well as the activity of selected ROS-detoxifying enzymes, i.e. SOD, CAT, and APX, were measured as described in [

70]. There were some minor modifications during sample preparation: 40 ml of algal culture were taken per each sample instead of 30 ml, algal pellets were rinsed with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.0 instead of growth medium, and because the strain 11-32b used in the present study has cell wall, the sonication parameters were different: 35% amplitude, 90 s total time of ultrasound emission in 9 s on/27 s off cycles.

Hydrophobic antioxidants, i.e. α-Toc, and PQH

2, were extracted with methanol and assessed using RP-HPLC system (Jasco LC-4000, Jasco Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) as described in [

34], with minor modification concerning solvent proportions. Briefly, column used was C

18 Tracer Excel 120 ODS-A (5 μm, 25 cm × 0.4 cm) and separation conditions were as follows: methanol:

n-hexane (340:60, v/v), flow rate 1.6 ml min

–1, absorbance detection at λ = 255 nm, fluorescence detection at λ

ex = 290 nm, λ

em = 330 nm.

Data statistical analysis was carried out using STATISTICA 13. The following analyses have been carried out: one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test to compare the means.

Figure 1.

Culture growth followed by optical density at 750 nm (a), and chlorophyll a + b content (b) measured on the 7th and 14th day of growth of Co-exposed C. reinhardtii. The applied CoCl2 concentrations are given in the legends. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). Chl, chlorophyll; Ct, control; OD, optical density.

Figure 1.

Culture growth followed by optical density at 750 nm (a), and chlorophyll a + b content (b) measured on the 7th and 14th day of growth of Co-exposed C. reinhardtii. The applied CoCl2 concentrations are given in the legends. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). Chl, chlorophyll; Ct, control; OD, optical density.

Figure 2.

Chlorophyll a to chlorophyll b ratio (a), the ratio of total carotenoids to total chlorophyll (b), and the Fv/Fm parameter representing the maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (c) in C. reinhardtii exposed to concentrations of CoCl2 indicated in the plots for 2 weeks. Photosynthetic pigment ratios are expressed as the ratios of pigment content expressed in [µg/ml of algal culture]. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). All means were compared using post hoc Tukey’s test, but for better clarity, only statistically significant differences between Co-exposed algae and the respective controls were marked with asterisks, * p<0,05. Car, total carotenoids; Chl a, chlorophyll a; Chl b, chlorophyll b; Ct, control; Fm, maximum fluorescence yield in the dark-adapted state; Fv, variable fluorescence, that is, the difference between Fm and minimum fluorescence in the dark-adapted state, F0.

Figure 2.

Chlorophyll a to chlorophyll b ratio (a), the ratio of total carotenoids to total chlorophyll (b), and the Fv/Fm parameter representing the maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (c) in C. reinhardtii exposed to concentrations of CoCl2 indicated in the plots for 2 weeks. Photosynthetic pigment ratios are expressed as the ratios of pigment content expressed in [µg/ml of algal culture]. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). All means were compared using post hoc Tukey’s test, but for better clarity, only statistically significant differences between Co-exposed algae and the respective controls were marked with asterisks, * p<0,05. Car, total carotenoids; Chl a, chlorophyll a; Chl b, chlorophyll b; Ct, control; Fm, maximum fluorescence yield in the dark-adapted state; Fv, variable fluorescence, that is, the difference between Fm and minimum fluorescence in the dark-adapted state, F0.

Figure 3.

Induction of NPQ in 1-week-old (a) and 2-week-old (b) cultures of Co-exposed C. reinhardtii. The applied CoCl2 concentrations are given in the legend. Before measurements, algae were dark-adapted for 30 min, pre-illuminated with weak red light < 4 µM photons m-2s-1 for 10 min, then exposed to red actinic light of intensity 200 μmol photons m-2s-1. The actinic light was switched off after 1800 s. The timing of the saturating pulses is indicated in the plots. Data are means ± SD (n = 6). AL, actinic light; Ct, control; D, darkness; NPQ, parameter representing non-photochemical quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence.

Figure 3.

Induction of NPQ in 1-week-old (a) and 2-week-old (b) cultures of Co-exposed C. reinhardtii. The applied CoCl2 concentrations are given in the legend. Before measurements, algae were dark-adapted for 30 min, pre-illuminated with weak red light < 4 µM photons m-2s-1 for 10 min, then exposed to red actinic light of intensity 200 μmol photons m-2s-1. The actinic light was switched off after 1800 s. The timing of the saturating pulses is indicated in the plots. Data are means ± SD (n = 6). AL, actinic light; Ct, control; D, darkness; NPQ, parameter representing non-photochemical quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence.

Figure 4.

Superoxide formation measured semi-quantitatively as colour intensity after NBT staining (a) and lipid hydroperoxides monitored using the fluorescent probe Spy-LHC (b) in C. reinhardtii exposed to concentrations of CoCl2 indicated in the plots for 2 weeks. Data are means ± SD (n = 6). All the means were compared using post hoc Tukey’s test, but for better clarity only the statistically significant differences between Co-exposed algae and respective controls were marked with asterisks, * p<0,05. Ct, control; LOOHs, lipid hydroperoxides.

Figure 4.

Superoxide formation measured semi-quantitatively as colour intensity after NBT staining (a) and lipid hydroperoxides monitored using the fluorescent probe Spy-LHC (b) in C. reinhardtii exposed to concentrations of CoCl2 indicated in the plots for 2 weeks. Data are means ± SD (n = 6). All the means were compared using post hoc Tukey’s test, but for better clarity only the statistically significant differences between Co-exposed algae and respective controls were marked with asterisks, * p<0,05. Ct, control; LOOHs, lipid hydroperoxides.

Figure 5.

The content of hydrophilic antioxidants, that is, total soluble thiols (a), ascorbate (b), and proline (c), and the activity of ROS-detoxifying enzymes, that is, superoxide dismutase (d), ascorbate peroxidase (e) and catalase (f), in C. reinhardtii exposed to concentrations of CoCl2 indicated in the plots for 2 weeks. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). Different letters denote means that differ from each other with statistical significance p < 0,05 (post hoc Tukey’s test). APX, ascorbate peroxidase; Asc, ascorbate in its reduced form; CAT, catalase; Ct, control; Pro, proline; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

Figure 5.

The content of hydrophilic antioxidants, that is, total soluble thiols (a), ascorbate (b), and proline (c), and the activity of ROS-detoxifying enzymes, that is, superoxide dismutase (d), ascorbate peroxidase (e) and catalase (f), in C. reinhardtii exposed to concentrations of CoCl2 indicated in the plots for 2 weeks. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). Different letters denote means that differ from each other with statistical significance p < 0,05 (post hoc Tukey’s test). APX, ascorbate peroxidase; Asc, ascorbate in its reduced form; CAT, catalase; Ct, control; Pro, proline; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

Figure 6.

The content of lipophilic antioxidants, i.e. α-tocopherol (a, b) and plastoquinol (c, d), normalised to the content of soluble protein (a, c) or the content of chlorophyll a + b (b, d) in C. reinhardtii exposed to concentrations of CoCl2 indicated in the plots for 2 weeks. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). Different letters denote means that differ from each other with statistical significance p < 0,05 (post hoc Tukey’s test). α-Toc, α-tocopherol; Ct, control; PQH2, plastoquinol.

Figure 6.

The content of lipophilic antioxidants, i.e. α-tocopherol (a, b) and plastoquinol (c, d), normalised to the content of soluble protein (a, c) or the content of chlorophyll a + b (b, d) in C. reinhardtii exposed to concentrations of CoCl2 indicated in the plots for 2 weeks. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). Different letters denote means that differ from each other with statistical significance p < 0,05 (post hoc Tukey’s test). α-Toc, α-tocopherol; Ct, control; PQH2, plastoquinol.