1. Introduction

The avian species have been incriminated as crucial contributors to the emergence and dissemination of pathogens that pose risks to both animal and human health [

1]; notably, migratory birds hold particular importance due to their capacity to traverse extensive distances seasonally, surmount geographical obstacles, and halt at ecologically analogous sites along their migratory routes, thereby creating clusters that facilitate pathogen spread [

2]. The dispersion, abundance, and extensive distribution of migratory birds across various landmasses and continents significantly contribute to this phenomenon [

3]. In addition to functioning as vectors, migratory birds are recognized reservoirs of zoonotic pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, and [

4]. These pathogens can be maintained over extended periods without clinical symptoms, thereby facilitating cross-species and interspecies transmission [

4].

Incriminatingly, molecular evidence has demonstrated the crucial roles played by this keystone species in the introduction of pathogens to previously unexposed regions; highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 and H5N8 have been repeatedly introduced into Africa through transcontinental migrants, resulting in poultry outbreaks in Nigeria, Egypt, Uganda, and South Africa [

5]. Migratory species have also been associated with the spread of West Nile virus, Newcastle disease virus, Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., and even antimicrobial-resistant bacteria [

6,

7]. The risks of transmission are particularly elevated in shared wetlands and peri-urban areas with inadequate biosecurity measures, where birds interact closely with livestock and human communities, thereby creating opportunities for co-infections, viral reassortment, and the emergence of new genotypes [

8,

9].

Each year, billions of birds facilitate connectivity between Europe and Africa, undertaking migrations between Palearctic breeding sites and Sahel–Sub-Saharan wintering habitats [

10]. In this process, they establish ecological conduits that permit pathogens to traverse thousands of kilometres within a matter of weeks, effortlessly crossing national borders and circumventing traditional biosecurity measures [

11]. Despite Africa’s critical role in global migratory networks, comprehensive data on the pathogens carried by migratory birds remain limited [

12]; unlike Europe and Asia, where structured long-term surveillance has been instituted, most African nations depend on ad-hoc surveillance triggered by outbreaks rather than proactive monitoring, thereby undermining the continent’s capacity for early detection of novel strains [

13]. This deficiency presents a dual challenge for Africa: how to manage and mitigate the epidemiological risks posed by migratory birds and the limited surveillance infrastructure to monitor them. Notably, existing gaps include inadequate knowledge of pathogen diversity, limited genomic surveillance to track viral evolution, and insufficient integration of avian ecology within veterinary and public health systems.

This review aims to: identify pathogens transmitted by migratory birds in Africa, including their role in viral reassortment and the emergence of novel strains; evaluate the implications for disease control and surveillance, with particular attention to the limitations of current systems; and provide policy recommendations tailored to African contexts, emphasizing the integration of One Health approaches for effective monitoring and outbreak preparedness. By synthesizing current evidence, this review highlights the critical role of migratory birds as propagators of emerging infectious diseases in Africa and offers a framework for targeted surveillance, control strategies, and cross-sectoral policy interventions.

2. Migratory Birds in Africa: Patterns and Ecology

Migratory birds are known to travel between Africa and Europe [

14,

15] in search of breeding sites and seasonal resources [

16]; typically, these birds winter in the Sahel [

4], and their migration is usually linked to rainfall [

17]. They breed in the short northern hemisphere summer and migrate south in autumn through Europe and the Mediterranean to spend the winter in Africa, before rerouting back to catch the Northern Spring [

18]. The ability of these birds to move faster than wingless hosts enables them to cross geographical and ecological barriers with ease [

4]; consequently, their increased exposure to multiple infectious pathogens [

19] and their vital role in disease transmission [

20] along their migration routes and beyond their native ranges [

19,

20]. Beyond functioning as hosts, reservoirs, and potential vectors for pathogens [

19,

21,

22], studies demonstrate that migratory birds also serve as transport vehicles for arthropod-borne vectors, such as ticks and lice, thereby further promoting and facilitating the dissemination of pathogens [

15]. Consequently, these reports underline these avian species as supporting both viremic and non-viremic tick-borne pathogen transmission [

15,

23].

2.1. Migratory Birds Implicated in Disease Transmission

The species of migratory birds found in Africa include passerines [

14]; waterfowl such as ducks, geese, and swans, shorebirds and waders [

24]; herons, egrets, and ibises [

25]; and Egyptian Vultures [

26]. Specifically, studies show that migratory waterfowls in the order

Anseriformes are a major vector of infectious pathogens, including

Newcastle virus, Duck plague, WNV, Parvovirus, Salmonella, Escherichia coli, Campylobacter, Vibrio, Chlamydophila psittaci, Pseudomonas, as well as the H5N1 and H5N6 subtypes of

Avian influenza virus [

7,

19,

27,

28]. Further studies additionally indicate that waterfowl serve as long-distance dispersers of the West Nile virus (WNV) among various species, leading to infections in amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and humans [

29]. Similarly, passerines are also vulnerable to fungi, viruses, bacteria, and parasites [

19]. Some of the novel and emerging viruses reported in passerines include

herpesviruses,

retroviruses (such as lymphoid leukaemia),

poxviruses,

coronaviruses, and

flaviviruses [

28,

30,

31]. Beyond these groups, shorebirds and waders possess the potential to disseminate the Avian Influenza virus (AIV) owing to their stopover at wetlands, rice paddies, and coastal lagoons during migration [

24]. Furthermore, the ingestion of infected carcasses by raptors contributes to the persistence of AIV in both natural and anthropogenic environments.

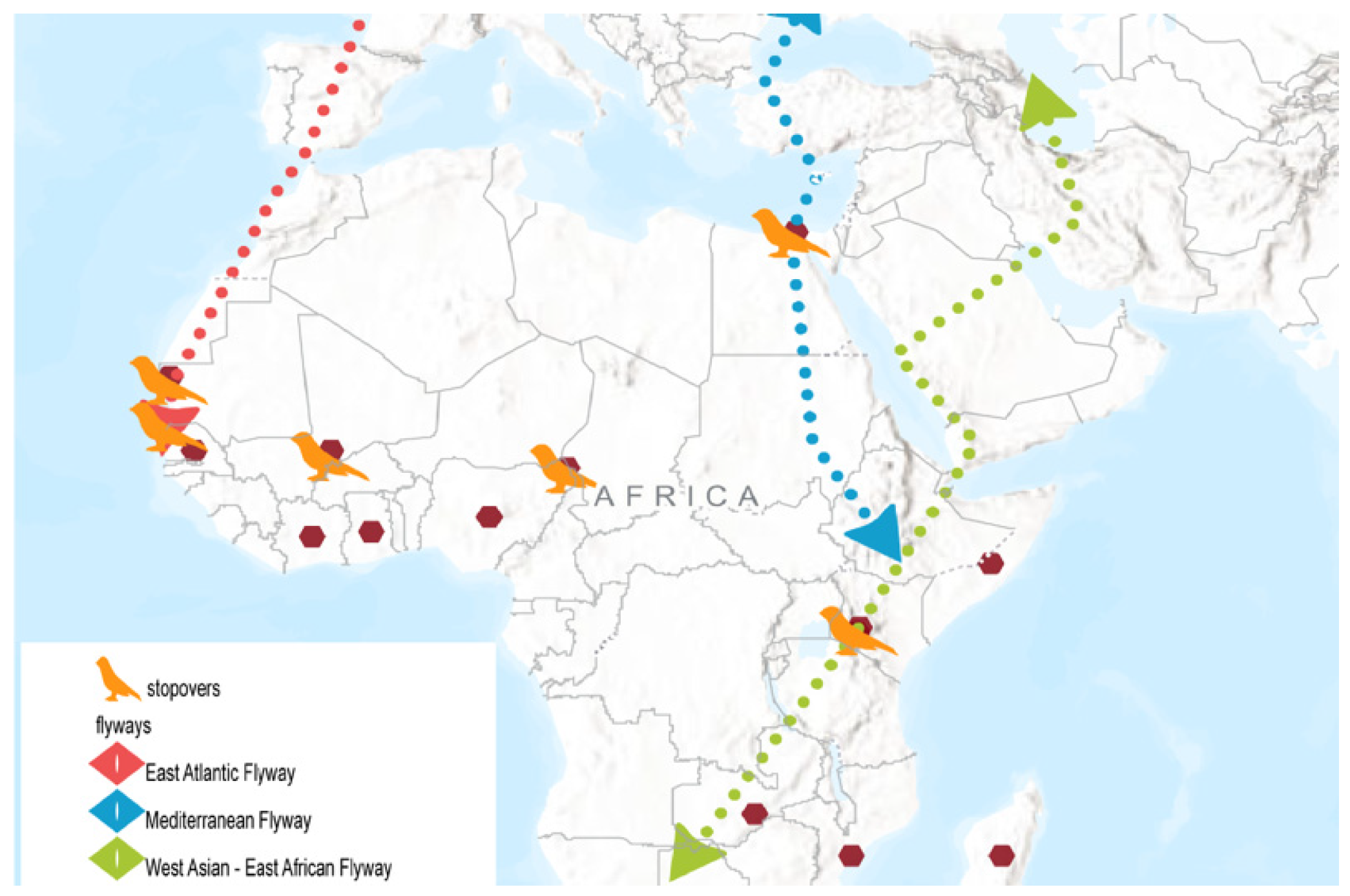

2.2. Major Migratory Flyways

The African/Palearctic migration of birds represents the most significant long-distance avian migration system globally [

18] (

Figure 1). Although it is essential to acknowledge that flyways differ among various bird taxa, migration between Europe and Africa occurs predominantly along three principal migratory axes: the East Atlantic, Black Sea/Mediterranean, and West Asian/East African flyways [

32,

33]. Nevertheless, for certain Anseriformes, particularly ducks, the delineation of flyways is less distinct, with fewer individuals migrating to southern Africa, and a larger proportion traversing a north-east/south-west axis between breeding and wintering regions within Western Eurasia [

32]. Eleonora’s falcons also do not follow a species-specific migratory route but exhibit significant variability in their paths [

34]. Conversely, migration patterns in birds such as geese and swans are generally highly segregated, involving movements along discrete flyways between traditional breeding and wintering grounds [

32]. While some species are classified as residents due to their infrequent movement in response to environmental changes, numerous species typically regarded as ‘migrants’ in Africa are effectively ‘nomads,’ as they do not undertake seasonal migrations but instead relocate owing to the unpredictability of food and water resources [

35].

2.3. Stopover Sites and Disease Propagation

Stopovers serve to prevent adverse environmental conditions, reduce predation risk, and allow time-space adjustments during migration [

2]. Some avian species undertake nonstop flight during migration, whereas others pause at stopover sites, potentially disseminating harboured pathogens [

6]. Due to the seasonal variations in Africa throughout the year [

17], and the impossibility of completing single journeys between breeding grounds and wintering areas, waterbirds utilize stopover sites [

36]. However, these sites do not merely act as resting places for birds en route but also function as clustering regions and hotspots for disease trafficking and dispersal [

19]; by playing these crucial roles in disease transmission and pathogen spread through facilitated interactions among local biological factors and species that are isolated for most of the year [

6,

19].

Across Africa, the western bird population migrates via Morocco to spend the northern winter in West Africa, while the eastern population traverses Egypt en route to eastern and southern Africa [

37] (

Figure 1). The northern Egyptian Nile Delta is regarded as one of the most significant bird migration routes globally [

38], owing to its moderate winter climate and proximity to the Red Sea, which provides abundant food resources [

39]. However, this declares the area a disease dissemination hotspot, as evidenced by the study of Gerloff et al. (2013), which presents a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of full genome sequences from low pathogenic avian influenza viruses (LPAI) circulating in Egypt [

38]. Additionally, the study conducted by Soliman et al. (2010) indicates active circulation of West Nile virus in various regions of Egypt, attributable to migratory bird clustering [

40].

Other notable stopover sites include the Parc National du Banc d’Arguin in Mauritania, which hosts the largest concentrations of coastal waterbirds, supporting millions of birds at peak seasons along the East Atlantic Flyway [

41]. Similarly, along the Senegal River delta, the Djoudj National Bird Sanctuary is also a notable site. The wetlands provide a crucial wintering ground for Palearctic migrants and support large colonies of Great White Pelicans and other African species [

42]. In East Africa, the Kenyan freshwater and alkaline lake System in the Great Rift Valley is home to some of the highest bird diversities in the world. It is a major nesting and breeding ground for great white pelicans [

43].

2.4. Evidential Patterns of Disease Spread from Migratory Birds

The dissemination of infectious pathogens by migratory birds across Africa has been historically influenced by the region’s diverse ecology, migratory flyways, and the principal wetlands that function as resting, breeding, and nesting habitats [

44]. Notably, this concept is reinforced by the continual reintroduction of new viral strains by migratory birds during nearly every season [

45,

46], as well as by satellite telemetry data demonstrating that infected birds can transport pathogens over thousands of kilometres within a matter of days, thereby complicating containment strategies [

47]. Studies indicate reports of an annual migratory pattern, with millions of migratory waterfowl traversing regions such as the Nile Delta, the Lake Chad Basin, the Inner Niger Delta, and the Rift Valley Lakes [

48,

49]. These are areas that strategically overlap dense human and livestock populations, thereby creating “sandwich-like” conditions for zoonotic transmission as disease hotspots, and significantly increasing the likelihood of disease spillover or cross-species transmutation [

50]. Therefore, there is a paramount need to correlate patterns of disease dissemination by relying on an integrated knowledge of ecological mapping of migratory routes, records of disease outbreaks, and analyzed statistical data on reported infections [

51].

Within the Nile Delta, research indicates that waterfowl have been implicated in the introduction of novel high pathogenic

avian influenza viruses (HPAI) strains, with subsequent spillover occurring in poultry and humans [

52]; West Africa, due to its coastal wetlands, tends to see higher rates of introductions of

influenza viruses from Europe, while the pathogen spread in East Africa is more influenced by the Asian flyways [

53]. The H5N1

avian influenza outbreaks in Nigeria in 2006 are widely believed to have been transmitted by infected migratory waterfowl arriving from Eurasia [

54]. This assertion is supported by the high genetic similarity between strains in Asia and those isolated in Nigeria, thereby confirming the transboundary nature of the dissemination [

54]. Furthermore, reports indicate that a nearly identical strain was isolated from a poultry farm in Senegal in 2021, which aligns with strains identified in Europe, further emphasising the intercontinental spread along the East Atlantic flyway [

46].

The transmission of West Nile virus (WNV) in South Africa and Senegal has been associated with the movement of migratory birds, particularly passerines that are capable of maintaining and transporting the virus across different regions [

55]. A total of 61 migratory bird species has been identified as potential contributors to the intercontinental dissemination of WNV or its variants, underscoring the interconnectedness of WNV-risk zones and avian migration pathways [

54]. This assertion is further supported by evidence indicating a potential overlap between WNV lineages 1 and 2, as well as between the Eastern and Western phylogeographic regions, and the two Afro-Palearctic bird migratory flyways [

56]. Moreover, the majority of species within the orders

Accipitriformes,

Falconiformes,

Strigiformes, and

Passeriformes, which are involved in WNV transmission cycles within forested environments, exist freely within these habitats, thereby supporting previous indications. [

57].

Data summarizing disease outbreaks frequently display clusters in proximity to wetlands, lakes, and irrigated agricultural areas [

58]. Between 2006 and 2020, more than 15 confirmed instances of avian influenza outbreaks in poultry were documented in nations such as Nigeria, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire. These countries are situated along the East Atlantic Flyway and function as wintering habitats for migratory waterfowl [

59]. An analysis of avian influenza surveillance data collected from 2002 to 2018 across African countries indicates that 3% of sampled avian populations tested positive for the avian influenza virus [

25]. Although this prevalence remains relatively modest, it highlights the considerable risk of introducing novel pathogen strains, given the substantial volume of bird migration across Africa each season [

25]. Moreover, seasonality significantly impacts the dissemination patterns of the disease; outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in poultry often peak shortly after the arrival of migratory birds during autumn and winter [

60].

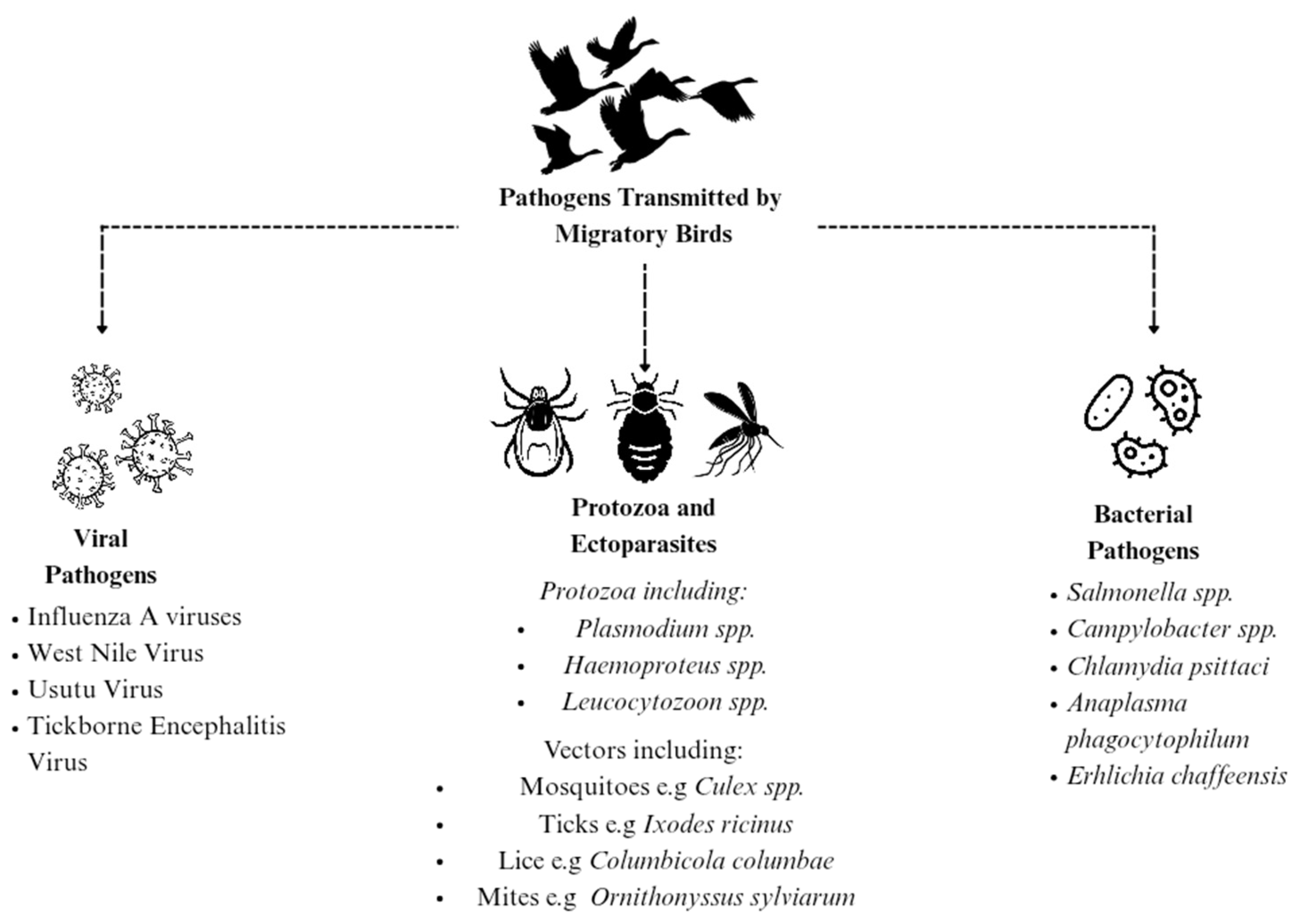

3. Mechanisms of Pathogen Transmission by Migratory Birds

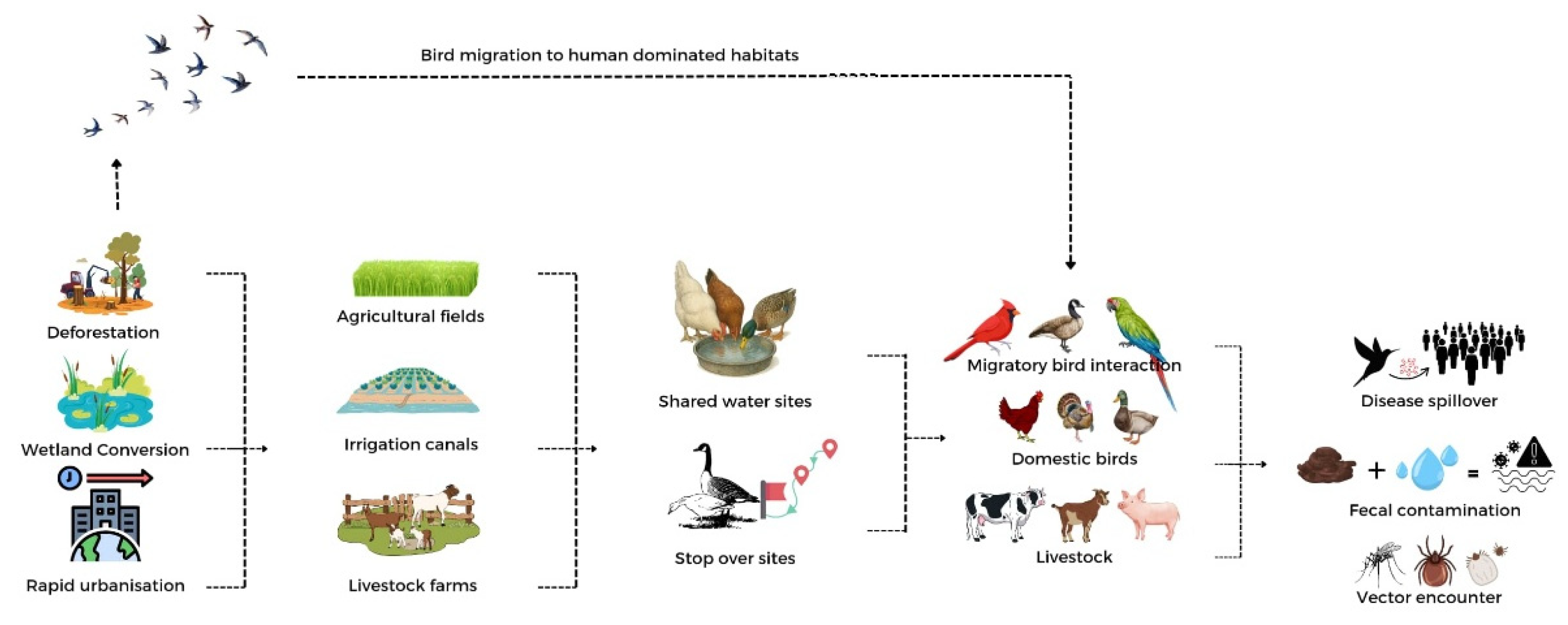

Migratory birds are increasingly recognised as significant contributors to the global spread of pathogens. Their extensive migratory routes, congregation at breeding and stopover locations, and interactions with diverse ecosystems facilitate opportunities for the transmission of viral, bacterial, and parasitic agents across different continents (

Figure 2;

Table 1).

3.1. Major Classes of Pathogens Incriminated in Transmission by Migratory Birds

3.1.1. Viral Pathogens

Migratory birds play a pivotal role in the ecology, evolution, and long-distance dissemination of various viral pathogens, most notably

influenza A viruses (IAVs) and mosquito-borne flaviviruses such as WNV [

61,

62,

63]. Waterfowl and shorebirds (orders

Anseriformes and

Charadriiformes) constitute the principal wildlife reservoirs for AIVs [

61,

63,

64]; nearly all known hemagglutinin and neuraminidase subtype combinations are present in these hosts in low-pathogenic forms, which are typically asymptomatic [

61,

63]. Seasonal bird migrations facilitate connectivity among breeding, staging, and wintering sites across continents, thereby enabling repeated seeding, genetic mixing, and turnover of viral lineages along major flyways [

61,

63]. Longitudinal analyses reveal consistent associations between avian migration ecology and AIV phylodynamics, with waves of subtype turnover aligning with migratory schedules and colony phenology.

The preceding years have highlighted the capacity of wild avian populations to facilitate the rapid, intercontinental dissemination of

highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). Specifically, the H5 clade 2.3.4.4b lineage, which achieved predominance by late 2020, disseminated throughout Eurasia, Africa, and the Americas, resulting in extensive mortality among wild birds and unprecedented outbreaks in poultry [

65]. Additionally, documented spillover events have been reported in a variety of mammalian species [

66,

67]. Molecular epidemiological analyses reveal multiple reassortment events among

avian influenza viruses, resulting in genotypes transported by migratory populations from Europe to North America during 2021–2022, which subsequently dispersed extensively within the United States and Canada. These findings elevate wild birds from mere “vectors” to active maintenance hosts within a panzootic system, with the timing and geography of incursions aligning with established flyway linkages.

Environmental persistence enhances transmission opportunities at aquatic stopover sites, as

influenza A virus (IAV) can remain infectious for several weeks to months in cold, low-salinity water, thereby creating a fecal–oral cycle in wetlands frequented by dabbling ducks; systematic reviews and experimental studies demonstrate slower viral decay rates at lower temperatures and salinity levels, with more rapid inactivation at higher values [

68,

69,

70]. Such abiotic “viral banks” may synchronize subtype dynamics with seasonal congregations of avian hosts and facilitate overwintering in northern wetlands. Beyond

influenza, migratory passerines and certain corvids serve as amplifying hosts for

West Nile virus (WNV) [

71]. In newly affected regions, a limited subset of competent avian species can predominate in transmission, resulting in significant host heterogeneity and superspreading dynamics that link avian communities to the seasonal activity of

Culex vectors [

71,

72,

73].

Emerging avian arboviruses, such as the Usutu virus, along with zoonotic threats posed by the Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), highlight the broad spectrum of viral risks associated with migratory systems [

74,

75,

76,

77]. European populations of Culex pipiens and Aedes albopictus have demonstrated their capacity to facilitate JEV transmission experimentally, thereby raising concerns regarding the potential involvement of widespread waterfowl and peri-urban habitats in the event of JEV introduction. These patterns collectively underscore the critical necessity for coordinated surveillance along migratory flyways, in high-density rookeries, and at vector “bridge” interfaces where avian, mosquito, livestock, and human populations converge.

3.1.2. Bacterial Pathogens

Wild and migratory birds carry a suite of enteric bacteria relevant to both animal and human health, including

Salmonella enterica and

Campylobacter spp. most frequently implicated [

78,

79]. Subsequent work has refined this understanding with higher-resolution culture, typing, and genomic tools, representing a significant synthesis across avian taxa that catalogues frequent isolation of zoonotic bacteria from free-living birds, while also warning that detection methods, biased sampling (e.g., scavengers, gulls), and survival in wild hosts complicate inference of true prevalence and transmission risk [

80]. For

Campylobacter spp.; gulls, waterfowl, and shorebirds are repeatedly identified as carriers, experimental colonisation studies and field surveys demonstrate that wild birds can harbour strains closely related to those in humans and livestock, indicating cross-ecosystem transmission [

81,

82,

83,

84].

Population structure analyses further reinforce host-associated lineages and ecological partitioning, suggesting that not all avian Campylobacter pose direct zoonotic threats [

82]. Complacent meta-analyses indicate that, while birds contribute to environmental loading—particularly around landfills, wastewater sites, and coastal roosts—their relative contribution to human disease burden remains challenging to quantify [

85]. Concerning Salmonella, synthesis and regional surveys indicate variable prevalence rates, ranging from below 1% to over 30%, contingent upon species, habitat, and methodologies [

86]. Gulls, corvids, urban ibises, and avian species that frequently visit anthropogenic food sources often display the highest carriage rates, thus creating potential risks for contamination of surface water, crops, and livestock feed [

86]. Additional research has demonstrated carriage in migratory and urban-adapting species, through genomic characterization of serovars and virulence genotypes, with occasional high prevalence in specific contexts [

86]. The epidemiological relevance includes: (i) direct avian disease outbreaks, (ii) contamination incidents at the wildlife–agriculture interface, and (iii) the potential dissemination of antimicrobial resistance determinants across landscapes [

19].

Key ecological mechanisms connect migration to the dissemination of bacteria [

4]. First, large gatherings at staging wetlands and landfills augment faecal contamination, thereby heightening the risk of downstream exposure for grazing livestock and the contamination of irrigation channels [

4]. Second, migratory connectivity can facilitate the transmission of strains across biogeographic regions, with stopover sites acting as’ bacterial hubs.” The simultaneous use of agricultural fields by geese, cranes, and gulls during migration introduces fecal matter directly onto cultivated fields, recognized as an (albeit episodic) risk pathway within produce safety frameworks [

4]. Although establishing a causal link between specific outbreaks and wild birds remains infrequent, the preponderance of evidence advocates for a surveillance strategy that prioritizes high-density avian activity sites near food production and water infrastructure [

87]. Recent comparative global analyses further detail the risk landscape: migratory birds tend to harbour a more diverse total pathogen assemblage than resident birds but do not necessarily carry a higher proportion of zoonoses, implying that migration increases encounter and mixing rates without uniformly elevating zoonotic hazards [

4]. This underscores the necessity to specify “which birds, where, and when,” moving beyond generic assumptions about migration to focus on species ecology, behaviour at stopover sites, and proximity to human systems.

3.1.3. Parasitic Agents

Haemosporidian protozoa—Plasmodium, Haemoproteus, and Leucocytozoon—are widespread in birds, with transmission by ornithophilic mosquitoes (primarily

Culex, but also

Culiseta, Mansonia, Aedeomyia, Coquillettidia), biting midges, and blackflies depending on parasite genus [

88]. Long-standing field parasitology and modern molecular surveys converge on

Plasmodium relictum as the most cosmopolitan avian malaria agent, comprising multiple mitochondrial lineages with broad host ranges and global distribution [

89,

90]. Migration enables both the geographic spread of parasite lineages and the assembly of diverse parasite communities within individual hosts at stopovers, increasing opportunities for within-host competition and recombination [

91,

92]. Emerging community-level and network analyses now demonstrate that migratory species often occupy central positions in host–parasite networks, connecting otherwise isolated parasite lineages and local bird communities. Comparative studies have shown a higher prevalence and lineage diversity in long-distance migrants (e.g.,

Acrocephalus warblers) compared to partial migrants or residents [

90,

93,

94]. These network connections have consequences beyond birds: by transporting parasites into new regions, migrants can trigger novel vector–parasite associations where competent vectors exist, potentially altering local transmission equilibria [

95,

96].

Surveillance activities conducted within the Doñana wetlands in southern Spain—a significant migratory hub—have identified the simultaneous circulation of

West Nile virus (WNV) and avian

Plasmodium among

Culex perexiguus and

Culex pipiens mosquitoes. This finding underscores that overlapping arboviral and protozoan transmission cycles can be sustained within the same aquatic, bird-abundant ecosystems [

97]. Long-term entomological research in East Asia similarly reports a variety of avian

Plasmodium lineages present in

Culex mosquito populations, with seasonal variations observed in vector abundance and parasite community composition [

88]. Experimental studies further demonstrate that avian

Plasmodium can upregulate parasitemia following mosquito probing, potentially increasing infectiousness during peak vector seasons [

98]. The interplay between climate variability, land-use change, and migration patterns is of critical importance; elevated temperatures can prolong vector seasons and suitable habitats, thereby coinciding with migration schedules to amplify exposure periods [

96,

99]. Ferraguti et al. (2018) highlight that comprehending and forecasting avian malaria dynamics necessitate an integrated approach considering the “three players”—host, parasite, and vector—rather than isolating individual components [

88,

97].

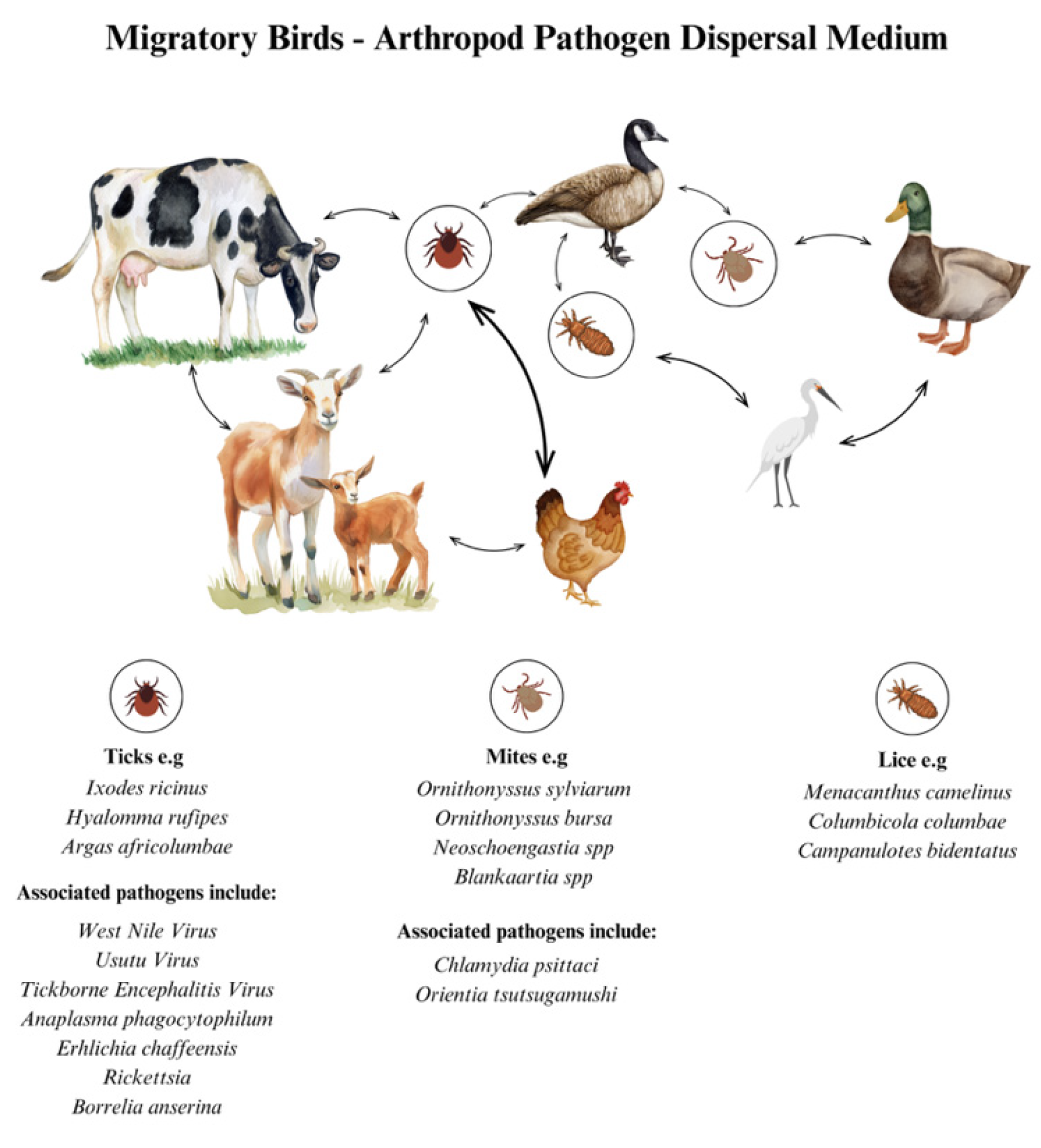

A notable effect is that naïve island bird faunas, such as those in Hawaii, have experienced significant mortality following the introduction of competent vectors and parasites. Similar risks are present along continental corridors as species ranges expand or shift [

88]. It is important to note that haemosporidians are not the only parasites transported by migrants; avian species also carry ticks and other ectoparasites, thereby potentially facilitating the introduction of tick-borne protozoa and bacteria into new regions. These transmission routes are further examined in the context of relevant pathways [

100,

101] (

Figure 3). The overarching perspective depicts migration as a macro-ecological engine: aggregating hosts, vectors, and parasites in space and time; promoting lineage mixing; and redistributing infections across diverse biomes [

90,

92,

99] (

Figure 3).

Table 1.

Mechanisms of Pathogen Transmission by Migratory Birds.

Table 1.

Mechanisms of Pathogen Transmission by Migratory Birds.

| |

Pathogen |

Route of Transmission |

Birds Implicated |

References |

| Viruses |

Avian Influenza Virus |

Fecal–oral |

Waterfowl, shorebirds, dabbling ducks |

[61,62,63] |

| |

|

Aerosol |

Pelicans, gannets, geese, cranes |

[102] |

| |

West Nile virus |

Culex mosquitoes |

Corvids |

[71] |

| |

Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) |

Culex pipiens, Aedes albopictus

|

Herons, egrets, bitterns |

[74,76] |

| |

Usutu virus |

Mosquito-borne |

Kurrichane thrush, piping hornbill, and little greenbull (Andropadus virens)

|

[103] |

| Bacteria |

Campylobacter spp. |

Fecal shedding & environmental persistence |

Gulls, waterfowl, shorebirds, pigeons, blackbirds, house sparrows |

[81,82,83,84] |

| |

Salmonella spp. |

Fecal–oral |

Egyptian geese, grey-headed gulls |

[104] |

| |

Escherichia coli |

Fecal–oral |

Passerines, waterfowl |

[80] |

| |

Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato |

Tick-borne

(Ixodid ticks) |

Passerines |

[101] |

| Parasites |

Plasmodium spp. (avian malaria) |

Mosquito-borne (Culex, Culiseta, Mansonia) |

Warblers, finches, waterfowl, pigeons, raptors |

[90,97] |

| |

Haemoproteus spp. |

Biting midges (Culicoides spp.) |

Passerines, pigeons, raptors |

[88] |

| |

Leucocytozoon spp. |

Blackflies (Simuliumspp.) |

Waterfowl, raptors, passerines |

[105] |

| |

Trichomonas gallinae |

Direct contact, contaminated water |

Pigeons, doves, raptors |

[80] |

| |

Toxoplasma gondii |

Ingestion of oocyst-contaminated feed/water |

Waterfowl, passerines |

[88]#break# |

| |

Babesia/Theileria spp. |

Tick-borne (Ixodid ticks carried by birds) |

Passerines, seabirds |

[100,101] |

3.2. Major Routes of Pathogen Transmission

3.2.1. Fecal Shedding & Environmental Persistence

Enteric viruses and bacteria utilize fecal deposition in wetlands, agricultural fields, and urban water bodies as a dominant route of pathogen transmission and transfer; In the case of IAV, fecal–oral transmission among dabbling ducks is sustained by environmental reservoirs; quantitative syntheses show that low temperatures and low salinity prolong viral persistence in water, allowing infection chains to bridge gaps in host density and season [

64,

68,

69,

70]. These findings highlight that cold-staged lakes can act as “memory” of previous infection waves, facilitating subtype re-emergence when migrants return, similar fecal contamination dynamics apply to

Salmonella and

Campylobacter, where high bird density and anthropogenic attractants (landfills, farm lagoons) increase loading into waterways and onto soil, with downstream exposure of grazing livestock and produce [

78,

81,

82].

3.2.2. Direct and Aerosol/Respiratory Contact

Colonial nesting and roosting behaviours—tens of thousands of birds packed in limited space, direct contact, and short-range aerosol spread. The recent HPAI epizootic produced catastrophic die-offs in colony-nesting species (pelicans, gannets, geese, cranes) [

102], illustrating how dense social structure can amplify transmission and mortality independent of environmental reservoirs [

106,

107]. While enteric shedding dominates for IAV in waterfowl, species with more respiratory tropism or behaviours involving close preening and feeding can sustain contact-mediated spread at rookeries and urban roosts [

107].

3.2.3. Mosquito-Borne Routes

Arboviruses rely on competent mosquito vectors, and avian communities provide the vertebrate amplification. For WNV in temperate zones,

Culex mosquitoes (e.g.,

Cx. pipiens, Cx. perexiguus) are the principal vectors; their abundance, host-seeking behaviour, and seasonal dynamics, combined with local bird species composition and immunity, determine outbreak intensity [

71,

72,

73]. Recent vector surveillance at a major European flyway site confirmed co-circulation of WNV with avian

Plasmodium, underscoring shared ecological drivers [

97]. Evidence from experimental infections indicates that European populations of

Cx. pipiens and

Aedes albopictus can also transmit JEV, reinforcing the need for pre-emptive surveillance at bird–vector interfaces given globalization and climate shifts [

74,

76].

3.2.4. Tick-Borne Routes and Bird-Mediated Dispersal

Migratory birds regularly carry ixodid ticks across long distances. They can disseminate both the ticks and the pathogens they harbour—

Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato,

tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV),

Rickettsia spp.,

Anaplasma phagocytophilum—seeding new foci outside endemic ranges [

101]. Repeated field studies at ornithological observatories in northern Europe demonstrate seasonal influxes of migratory birds infested with ticks, which carry detectable pathogens. Additionally, global reviews emphasise the role of avian species as transport hosts and potential reservoirs or co-feeding hosts [

100,

101]. Surveillance in Italy and elsewhere continues to expand the list of bird-borne tick–pathogen associations. Management implications include early-season acarological monitoring at migration bottlenecks and public health messaging in newly affected peri-urban green spaces [

100].

3.2.5. Bridging Interfaces

The highest risks arise where these pathways intersect: wetlands adjacent to dairies or feedlots, landfills beside produce fields, urban parks with dense roosts and abundant

Culex breeding, and stopovers that concentrate birds above tick-rich vegetation. A One Health surveillance architecture—combining bird banding, carcass reports, wastewater and surface-water testing, mosquito trapping, and tick screening—offers the best chance to detect and mitigate cross-species transmission before it spills into livestock or human populations [

108].

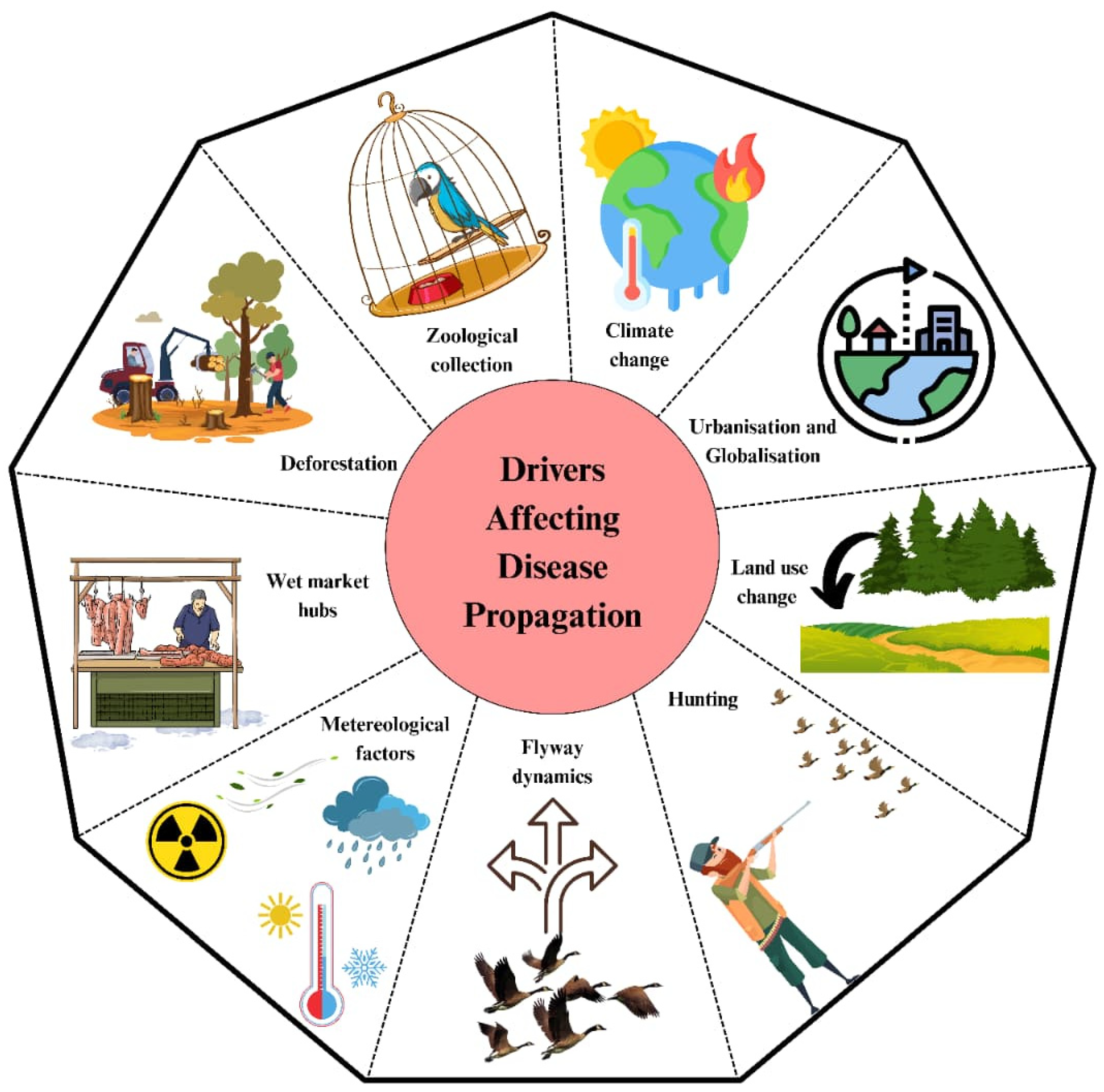

4. Drivers Affecting Disease Propagation by Migratory Birds

Numerous anthropogenic and ecological factors, such as urbanization, hunting, wet market activities, land-use changes, and climate change, combined to make it easier for pathogens to spread along migratory routes (

Figure 4). Therefore, it is essential to comprehend these interrelated elements to forecast spillover risks, direct surveillance activities, and inform evidence-based disease control strategies.

4.1. Meteorological Factors

Rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns are altering the Afro-Palearctic flyways by affecting the timing and availability of food and water resources for avian species [

109,

110]. The advancement of spring seasons, coupled with increasingly hot and arid conditions in the Sahel and North African stopover locations, compels species to adjust their migratory schedules, congregate at diminishing wetland habitats, explore novel sites, or migrate further south or to higher elevations [

110,

111]. These modifications in migratory routes and timing elevate interactions among various bird species, resulting in heightened overlap between migratory birds, resident species, domestic poultry, and vectors, thereby fostering conditions conducive to the dissemination of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. Evidence indicates that climate-induced disruptions in migration, extended stopover durations, and increased overlap with resident populations amplify the risk of pathogen transmission [

109].

4.2. Climate Change and Pathogen Dynamics

An increasing body of scholarly research shows that waterbirds are currently changing their distributions in response to climate variability [

112,

113,

114], while wetlands are undergoing climate-driven transformations [

115,

116,

117]. Africa, particularly its sub-Saharan regions, functions as a seasonal refuge for millions of Eurasian waterbirds, including approximately 5.4 million ducks that migrate to western and eastern Africa during the northern winter [

24,

48]. Rising temperatures and drought conditions decrease the extent of wetlands, resulting in the concentration of large flocks into a reduced number of habitats for extended periods [

118]. This crowding increases the likelihood of fecal–oral transmission of

influenza A viruses and enhances opportunities for spillover events at the interfaces between poultry and wildlife [

24,

119]. Field studies conducted across the continent demonstrate that factors such as rainfall, water levels, and bird density are significant predictors of

Avian influenza (AI) prevalence in wildfowl [

119]. Phenological mismatches induced by climate change may redirect migratory birds into novel ecosystems, including irrigated farmland and peri-urban wetlands—where contact among wild birds, poultry, and humans is more probable, thereby creating new pathways for pathogen transmission [

111]. Indirectly, warmer conditions accelerate mosquito development, shorten the extrinsic incubation period of WNV, and expand the seasonal and elevational ranges of avian-feeding vectors [

120]. Although much of this work comes from Europe and temperate systems, similar thermal mechanisms underpin growing WNV suitability across Afro-Palearctic flyways that connect African avian reservoirs to Eurasia [

121,

122]

4.3. Flyway Dynamics

Extensive surveillance confirms persistent circulation of

influenza A viruses in African wild and domestic birds, reflecting both local maintenance and episodic amplification [

24,

119]. Phylogeographic studies indicate that Africa often serves as an ecological sink for highly pathogenic

Avian influenza virus (HPAI) H5 lineages, which enter through migratory bird movements and the poultry trade [

123]. West Africa has emerged as a major hotspot, with onward spread shaped by host ecology and climatic conditions [

53]. The 2016–2018 H5N8 epidemic exemplifies this pattern, entering sub-Saharan Africa via Eurasian flyways and significantly impacting wild avifauna and poultry [

124,

125,

126]. Corresponding trends are observable for WNV, in which avian species serve as reservoirs and mosquitoes act as vectors. Elevated temperatures amplify mosquito abundance, viral replication, and habitat suitability, thereby heightening WNV risks along the Afro-Palearctic migration corridors [

127]. Modelling confirms that climate change has already broadened the extent of WNV-suitable regions, further emphasising the crucial role of migratory connectivity in transcontinental virus circulation [

120,

121].

4.4. Land-Use Change

Deforestation, wetland conversion for agricultural purposes, and rapid urbanization are reducing the habitats available to migratory birds, resulting in fragmented, human-dominated landscapes across Africa [

114]. These environmental changes disrupt the Afro-Palearctic flyways, compelling species to adjust their stopover and wintering strategies [

128]. Consequently, these shifts lead to increased concentrations of various bird species, heightened interactions with poultry in peri-urban or agricultural settings, and escalated encounters with vectors thriving in altered ecosystems. Collectively, these factors create ecological “hotspots” that facilitate the transmission of

Influenza A Virus (IAV) and

West Nile virus (WNV) [

24,

129,

130,

131] (

Figure 5). Large-scale African wetland studies illustrate that AIV prevalence exhibits a strong correlation with hydrological conditions and bird crowding [

119]. Agricultural drainage and irrigation initiatives (e.g., rice, sugarcane) diminish wetland availability, channelling migratory birds into fewer habitats and increasing disease risk. Birds displaced from natural habitats increasingly utilize peri-urban reservoirs, irrigation canals, and livestock ponds, where they interact with poultry, thereby forming viral “mixing bowls” [

24,

132]. Conversely, the protection and restoration of wetlands serve to reduce host density and risky interfaces, consequently decreasing AIV prevalence [

133].

4.5. Deforestation and Agricultural Expansion

Deforestation influences avian communities and migratory patterns, leading some species to transition into novel ecosystems dominated by poultry and synanthropic birds; comprehensive global analyses indicate that habitat alteration increases exposure to haemosporidian parasites and viruses [

73,

134] (

Figure 5). In African agricultural wetlands, a subset of adaptable “bridge-host” species has been identified to migrate between wildfowl habitats and farms, facilitating the transfer of AIV and other

flavivuses across the wild–domestic interface [

132]. On a continental scale, agricultural expansion serves as the primary catalyst for avian habitat destruction, thereby enhancing wild–domestic interactions along flyways (BirdLife International, 2022).

4.6. Urbanisation and Vector-Borne Risks

Urbanization significantly contributes to the development of heat islands, nutrient-rich aquatic environments, and stormwater management systems that facilitate the breeding of Culex mosquitoes, recognised as primary vectors for

West Nile virus [

127]. Empirical research has consistently demonstrated that changes in land use and urban expansion lead to an increase in vector populations and the potential for

West Nile virus transmission [

127] (

Figure 5). Although most evidence is derived from temperate regions, analogous processes apply to Afro-Palearctic pathways [

127,

135]. Risk maps specific to Africa further emphasise extensive zones conducive to WNV, where avian, vector, and human populations intersect, particularly in irrigated and urban environments.

4.7. Wet Markets and Trade Hubs

Live-bird markets (LBMs) function as convergence points for diverse avian species originating from multiple geographic regions—such as migratory waterfowl and domestic poultry—creating “mixing vessels” where

Avian influenza viruses (AIVs) may be subject to amplification and reassortment [

136] In West Africa, genomic investigations reveal that Nigerian LBMs consistently harbour and disseminate

influenza A viruses, with particular emphasis on H9N2 strains; whole-genome analyses demonstrate ongoing circulation and transmission connections between markets and farms [

137]. Similar patterns have been identified in Mali, where H9N2 lineages indicate regional dissemination through trade networks (Sanogo et al., 2024). In Egypt, LBMs have served as critical reservoirs for highly pathogenic H5 viruses, including those from clade 2.3.4.4b, which have been detected in conjunction with farm outbreaks [

138,

139,

140].

4.8. Poultry Farms and the Wild–Domestic Interface

Production systems that situate domestic waterfowl, free-ranging poultry, rice paddies, and irrigation canals in proximity to migratory waterbirds establish quintessential ‘bridge host” conditions for the maintenance and spillover of

Avian influenza virus (AIV) [

132]. In rural Egypt, research has identified free-ranging practices, shared water sources, and inadequate disposal of carcasses and feces as primary factors contributing to the occurrence of H5N1 in backyard poultry [

140]. Moreover, increased domestic–wild bird contact rates were observed in affected villages [

141]. In Southern Africa, the introduction of clade 2.3.4.4 H5Nx viruses by migratory birds has led to their dissemination among commercial poultry and ostriches, exemplifying the potential for breaches in farm biosecurity amid heightened wild-bird activity [

53,

142].

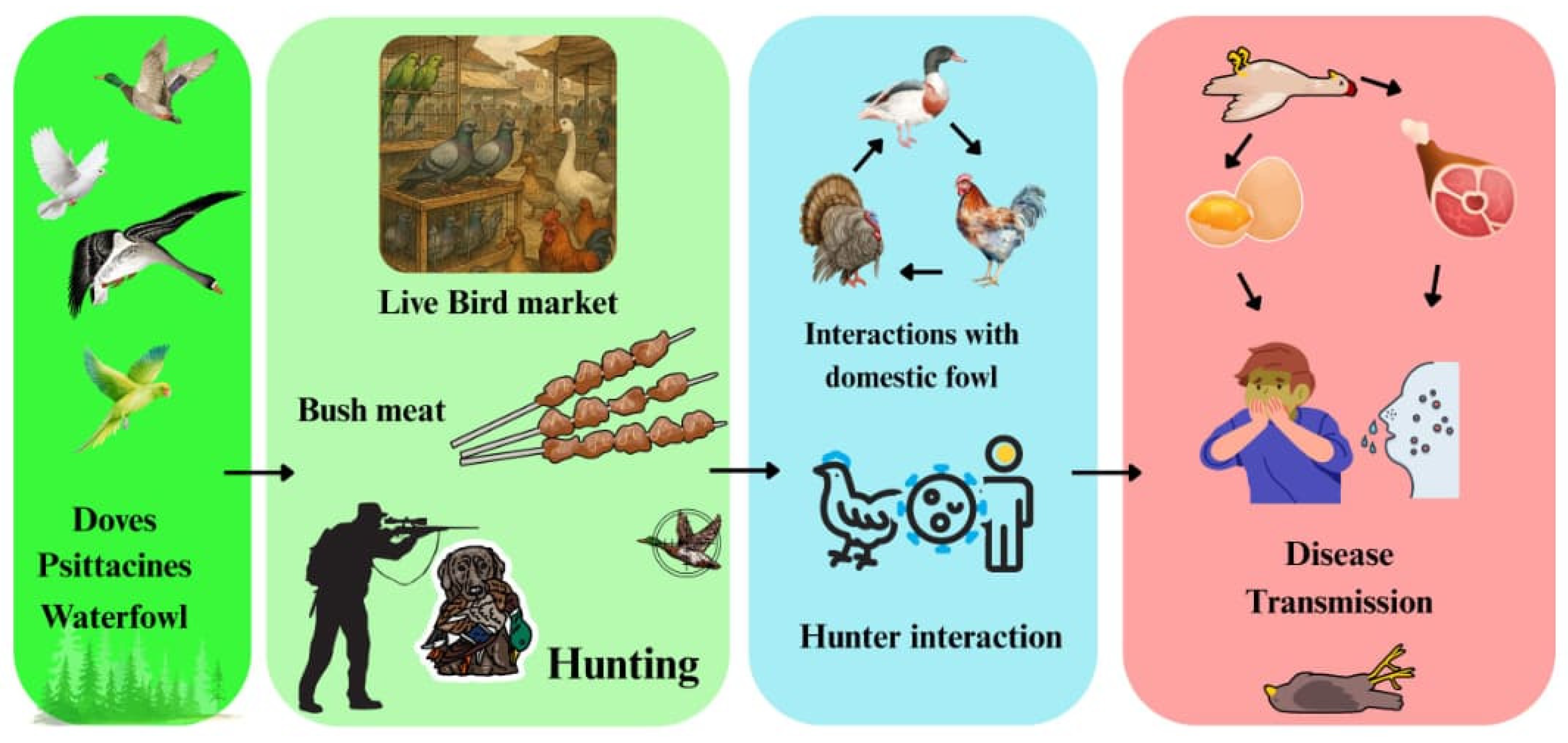

4.9. Hunting, Bushmeat Trade, and Field Processing

The hunting, harvesting, and informal sale of wild birds—including migratory waterfowl and doves—constitute additional transmission pathways among hunters, domestic flocks, and other wildlife [

143]. Although data concerning pathogens in hunted birds throughout the continent remains limited, reviews under the One Health framework consistently recognise bushmeat and wildlife markets as high-risk interfaces for pathogen spillover; This is due to the clustering of stressed, multi-species hosts and the facilitation of cross-regional movement, including the

Avian influenza virus (AIV) [

53,

144] (

Figure 6). Genomic surveillance in southern Africa confirms that, once AIVs establish in wild columbids and waterfowl, there is potential for spillover into nearby domestic settings—habitats also frequented by hunters [

143].

4.10. Avian Pets and Zoological Collections

The legal and informal trade of cage birds—such as psittacines, passerines, and columbids—maintains a range of avian pathogens, particularly

Chlamydia psittaci (psittacosis), which infects both wild and domestic birds and can spill over to humans [

145]. Zoological gardens and rehabilitation centres, which house mixed collections of exotic and native birds, have also reported incursions of HPAI during regional outbreaks [

146]. In southern Africa, clade 2.3.4.4 H5Nx affected zoo populations alongside commercial and wild birds, underscoring the two-way risk between captive and free-living avifauna [

143]. Similarly, H5N8 caused mass mortality in African penguins in Namibia, demonstrating the vulnerability of conservation species to spillover events [

146].

4.11. Globalization: Flyways, Trade Routes, and Outbreaks

High-resolution phytogeography reveals that intercontinental H5 epizootics coincide with extensive bird migrations and are also disseminated through commercial trade. The 2014–2017 H5N8 outbreaks adhered to sub-Arctic staging areas and Eurasian flyways prior to dissemination to multiple regions, underscoring the pivotal role of migratory waterbirds in enabling swift, long-distance transmission [

147]. In Africa, recurrent introductions position the continent predominantly as an ecological sink rather than a source, with further dissemination primarily influenced by host ecology and environmental conditions [

53]. More recent research, integrating avian distribution data with H5 lineage dynamics, demonstrates a strong temporal correlation between migratory periods and the worldwide dispersal of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza [

148].

4.12. Cross-Border Poultry Systems as Viral Amplifiers

Once viruses are introduced, poultry trade networks—including LBMs, cross-border poultry transport, and regional value chains—serve as accelerators that bypass natural flyway distances. West African studies reveal that H9N2 and other AIVs persist within LBMs, with genomic evidence of spread along trade routes [

137,

149]. Globally, analyses indicate that wild-bird migration accounts for long-distance jumps, while poultry production and trade explain local and regional persistence—two interconnected drivers of spread [

150,

151]. In southern Africa, genomic studies of clade 2.3.4.4b H5 outbreaks document repeated introductions followed by sustained farm-level transmission, highlighting how porous borders and commodity flows facilitate viral spread after initial seeding [

152,

153].

5. Sequelae of Migratory Birds as Drivers of Infectious Diseases

Migratory birds serve as natural reservoirs and dispersal agents for a broad spectrum of pathogens, making them pivotal actors in the ecology and epidemiology of emerging and re-emerging diseases. The sequelae of this role span ecological disruptions, agricultural and veterinary losses, human health impacts, and evolutionary dynamics such as antigenic shift, ultimately reinforcing the need for integrated One Health surveillance.

5.1. Ecological Sequelae

5.1.1. Biodiversity Impact

The cascading impacts of disease propagation by migratory birds not only threaten livestock and human health but also disrupt ecological balance, alter species abundance, drive declines in susceptible wildlife populations, and pose a significant risk to biodiversity conservation. Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) has repeatedly caused unprecedented die-offs in wild waterfowl, gannets, cranes, and seabirds, with broad consequences for community structure and long-term species recovery [

61,

62]. The emergence of WNV in North America similarly triggered sharp population declines in corvids and other passerines, with persistent effects on avian biodiversity [

71,

73]. Since 2020, there has been a major shift in the epidemiology of Avian influenza, with the virus evolving into a multi-host panzootic that increasingly affects both wild birds and mammals [

154,

155]

. Mortality events have now been documented in over 300 bird species worldwide, including waterfowl, raptors, and seabirds, with notable declines in gannets (

Morus spp.), terns (Sterninae), and skuas (Stercorariidae)—long-lived, low-fecundity taxa that face uncertain recovery following mass mortality [

155,

156]. In the Easter Ross Peninsula, coinciding with confirmed HPAI cases in sympatric pink-footed geese (

Anser brachyrhynchus), common buzzards (

Buteo buteo) experienced a sharp decline in occupied territories, exemplifying the indirect trophic impacts of HPAI outbreaks [

157]

.

The impact of Highly Pathogenic

Avian Influenza (HPAI) on biodiversity now extends beyond avian species. In South America, a minimum of 31,894 South American sea lions (Otaria flavescens) and 17,400 southern elephant seals (Mirounga leonina) have fallen victim to HPAI, underscoring the unprecedented expansion of host range and mortality across diverse taxa [

158,

159]. Other mammals, including dairy cattle and carnivores, have also been affected [

160,

161]. The geographical scope of these outbreaks is equally concerning: instances among wild bird populations have been documented in Nigeria (greater crested tern, pied crow, grey crowned crane), Lesotho, Botswana, and South Africa, where mass mortality events among the endangered Cape cormorants (

Phalacrocorax capensis) occurred during the 2021 H5N1 outbreak [

152,

162,

163]. In Europe, recurrent epizootics involving the Usutu virus have caused substantial declines in blackbird and passerine populations, resulting in significant alterations within local avian communities [

74,

77]. Collectively, these events emphasize the dual role of migratory birds as not only vectors of zoonotic pathogens but also as catalysts for significant biodiversity changes at both regional and global scales.

5.1.2. Parasite Host Network Restructuring

During migration across different geographical regions, migratory birds encounter locally endemic parasites, which they may acquire and later spread to new areas along their routes [

164,

165,

166]. By transporting these parasites across biogeographic boundaries, migrants significantly influence parasite ecology and evolution, often altering infection patterns at stopover and breeding sites [

93,

130,

167]. These patterns are strongly influenced by host phylogeny. Co-evolutionary processes and parasite adaptation to specific host environments increase the likelihood of closely related hosts sharing parasites, resulting in phylogenetically structured networks [

168,

169,

170]. The arrival of new parasites can disrupt existing host-parasite relationships and create novel associations, reshaping entire ecological networks [

171]. Migratory birds frequently occupy pivotal positions within ecological networks by encountering diverse parasite communities along their migratory pathways. Through these interactions, migrants have the capacity to homogenize parasite populations across geographically distant regions, thereby enhancing network connectivity. Notably, long-distance migrants tend to exhibit higher prevalence and greater diversity of haemosporidian parasites, which they can introduce into novel host communities and acquire locally, facilitating a bidirectional transfer of parasites [

172].

Recent studies further underscore the complexity of these interactions, Han et al. (2023) demonstrated that winter visitors exhibited higher prevalence and infection intensity; however, they infrequently shared parasites with resident birds. This indicates that such migrants are likely to acquire Plasmodium during migration or at departure points, with limited subsequent transmission to resident populations. For example, Jenkins et al. (2012) found that migratory birds often harbour broader parasite assemblages compared to residents, while Teitelbaum et al. (2018) demonstrated that long-distance migrants host greater parasite diversity, reflecting their broader geographic exposure. Collectively, these findings highlight migratory birds as critical “connectors” within global parasite–host networks. By linking distant ecosystems, they facilitate lineage recombination, reshape community structures, and alter endemic transmission equilibria. Such processes underscore the macro-ecological role of migrants in driving parasite evolution, expanding pathogen ranges, and influencing disease emergence at the wildlife–livestock–human interface.

5.2. Agro-Veterinary Sequelae

5.2.1. Veterinary Losses – Poultry and Livestock Outbreak

From a veterinary perspective, the consequences of bird-borne pathogen dissemination are particularly severe for poultry; HPAI incursions, seeded by wild birds, have devastated poultry industries worldwide, triggering mass culling campaigns, disrupting food supply chains, and prompting international trade bans [

66,

67]. The African poultry industry is especially vulnerable, facing intermittent outbreaks that threaten productivity, profitability, and rural livelihoods. Migratory birds play a crucial role in spreading avian-borne diseases into agricultural systems, with cascading impacts that include declines in poultry consumption and significant price reductions [

173]. During the initial outbreak of Highly Pathogenic

Avian Influenza (HPAI) in Egypt (2005–2006), over 30 million birds were slaughtered, resulting in an estimated economic loss of LE 3 billion (approximately US

$0.5 billion). Throughout the nation, approximately 250,000 workers lost their employment due to the collapse of poultry production, as well as the closure of feed mills, hatcheries, and retail outlets [

173]. International trade restrictions and the cessation of poultry exports exacerbated the crisis, while the destruction of valuable national genetic lines and breeds resulted in irreparable long-term losses. Demand for vaccines and drugs increased by 11.6%, further straining already fragile production systems [

174].

Beyond influenza, bacterial pathogens such as

Salmonella spp. and

Campylobacter spp. are frequently shed by gulls, geese, and corvids, contaminating irrigation water, livestock feed, and crop fields [

78,

79,

81]. These contamination events present intermittent yet significant risks for the occurrence of foodborne outbreaks. An additional, and equally urgent, concern pertains to the role of migratory birds in the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Birds harbour extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing

E. coli and other

Enterobacteriaceae, acting as vectors for the transcontinental spread of resistance determinants [

85].

5.2.2. AMR Movements

Migratory avian species are increasingly acknowledged as potential vectors for the transmission of bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Environmental hotspots such as wastewater treatment facilities, aquaculture ponds, and intensive livestock farms function as reservoirs for antibiotics, resistant bacteria, and resistance genes, which subsequently disseminate into the surrounding ecosystems [

175]. The proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) across these environments constitutes a significant global threat to both human and animal health [

176]. The movements of wildlife, particularly those of long-distance migratory birds, exacerbate this issue. Through foraging at contaminated sites and dispersing across various continents, migratory birds function as mobile vectors capable of facilitating the international dissemination of resistant bacteria and ARGs, including into remote or previously unaffected regions [

177,

178]. Furthermore, studies indicate that resistant strains and genes can be exchanged among migratory bird species at shared stopover habitats, facilitating lineage mixing and enhancing the global dissemination of AMR determinants.

5.3. Human Health Sequelae

5.3.1. Emerging Arbo-Pathogen Risk

The zoonotic consequences of pathogen spread via migratory birds are especially evident in the emergence and increase of arboviruses. Migratory birds serve as important reservoirs and amplifying hosts for WNV,

Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), and

Usutu virus (USUV), which are then transmitted to humans through mosquito vectors, resulting in outbreaks of encephalitis and serious neurological conditions [

73,

76,

179]. Evidence from Europe shows that avian

Plasmodium and WNV can coexist within the same

Culex mosquito populations, illustrating how shared ecological factors can maintain complex, overlapping transmission cycles and raise the risk of multi-pathogen spillover [

89]. Besides mosquito-borne viruses, passerine migrants also facilitate the dissemination of ixodid ticks infected with

Borrelia burgdorferi (the causative agent of Lyme disease),

Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV), and

Anaplasma phagocytophilum, which is responsible for Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis. Seasonal field investigations conducted in northern Europe document influxes of tick-infested migratory birds that introduce pathogens into new regions, thereby effectively expanding the geographic distribution of tick-borne diseases [

100,

101]

5.3.2. Propagating Enteric Infections – Foodborne Disease

Campylobacter species, particularly

C. jejuni and

C. coli, are the leading zoonotic bacteria associated with human gastroenteritis worldwide. Wild birds, especially migratory species, serve as important reservoirs and potential transmission pathways from avian sources to humans [

180]. Surveillance conducted at wintering and stopover sites in China between May 2020 and March 2021 identified multiple

Campylobacter species—including

C. jejuni,

C. coli,

C. lari, and

C. volucris—in fresh fecal droppings of migratory birds, highlighting the high diversity of

Campylobacter circulating in wild avifauna [

180]. Agricultural environments further represent critical high-risk interfaces. Wu et al. (2024) demonstrated that livestock farms and manure lagoons provide attractive foraging habitats for wild birds, thereby facilitating cross-species pathogen transmission. These findings align with those of Hald et al. (2016), who demonstrated that birds foraging on mixed diets of animal waste and vegetation near poultry and cattle stables carried higher loads of thermophilic

Campylobacter [

82,

180].

Beyond carriage, migratory birds may harbour virulence determinants and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes [

39]; In Egypt and elsewhere,

Campylobacter strains isolated from migratory birds have demonstrated both virulence and resistance profiles, raising concerns about spillover into broiler flocks and the wider poultry production chain [

39]. Supporting these findings, a meta-analysis of 431 North American bird species reported pooled prevalence estimates of 27% for

Campylobacter, 20% for pathogenic

E. coli, and 6.4% for

Salmonella. However, the study emphasized substantial uncertainty regarding direct spillover into humans, reflecting significant data gaps [

85]. Large-scale surveys provide further evidence of the zoonotic potential of wild birds. A recent global analysis detected 760 pathogens in 1,438 wild birds

, including 212 with confirmed zoonotic potential and 387 classified as emerging pathogens identified within the past four decades. These findings reinforce the critical role of wild, particularly migratory, birds as reservoirs and disseminators of enteric pathogens with implications for human health [

4].

5.4. One Health Implication

5.4.1. International Initiatives and Policy Making

The global nature of migratory bird movements and the transboundary risks associated with avian-borne pathogens make international cooperation essential for effective surveillance and control. The World Health Organization (WHO), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) emphasize the importance of coordinated monitoring and transparent data sharing . Joint platforms such as the FAO–OIE–WHO Global Early Warning System (GLEWS) provide integrated surveillance across the animal–human health interface, enabling the early detection of avian influenza strains and reducing the risk of spillover into poultry or human populations [

181]. At the regional level, strong frameworks exist in Europe. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) coordinate continent-wide monitoring of avian influenza and other zoonoses in wild birds, producing seasonal risk assessments that guide national preparedness and rapid response (EFSA et al., 2023). In Africa, regional initiatives are expanding but remain challenged by limited veterinary infrastructure, uneven diagnostic capacity, and resource constraints [

182]. Avian influenza outbreaks frequently result in immediate international trade restrictions, disrupting poultry markets and rural economies. Countries affected by HPAI outbreaks face not only direct losses from mass culling but also long-term impacts on food security and farmer livelihoods [

62,

158,

173].

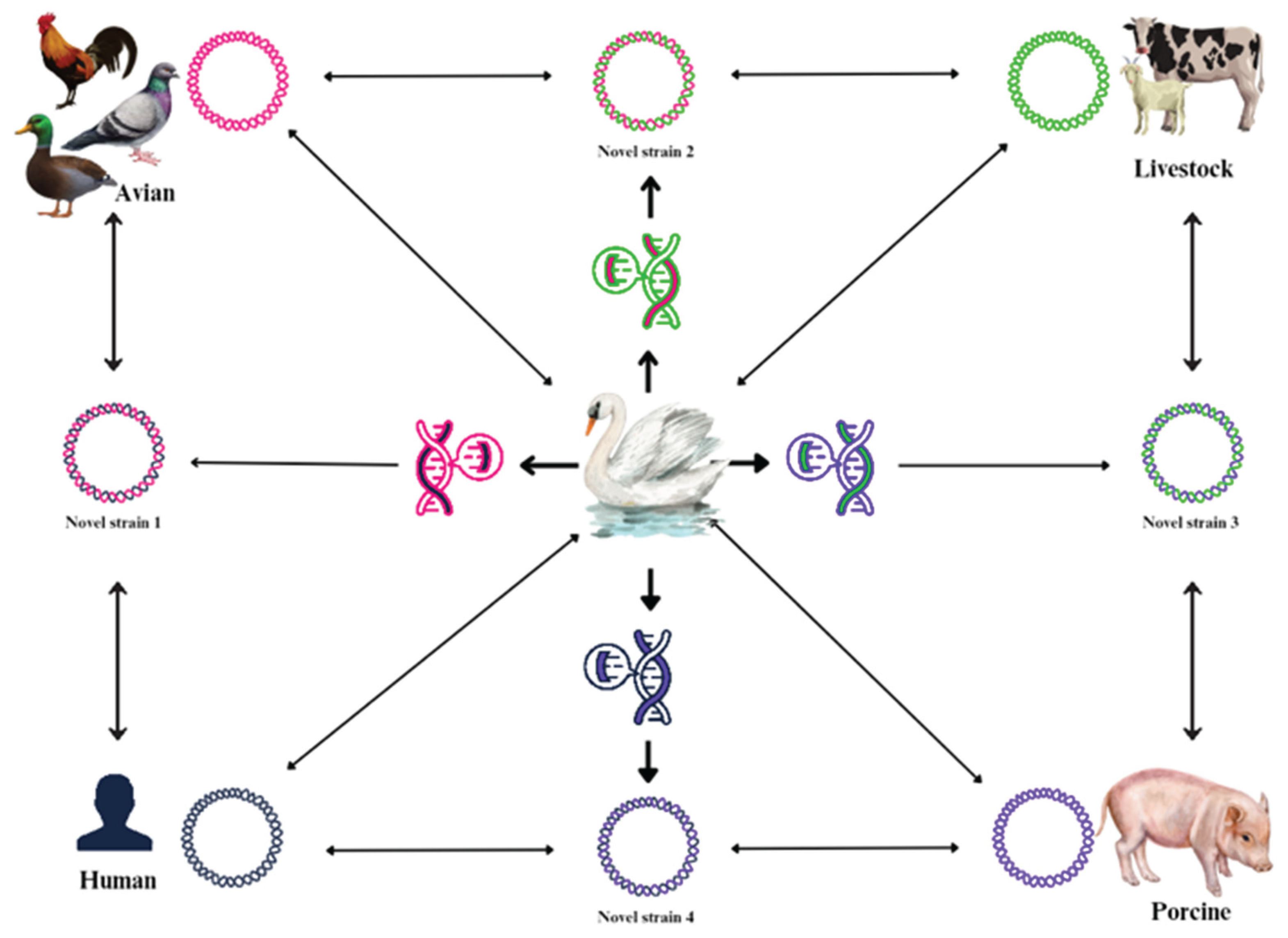

5.4.2. Antigenic Drift and Shift– Emergence of New Outbreak

The antigenic evolution of influenza viruses underpins both seasonal epidemics and the emergence of pandemics. Antigenic drift refers to the gradual accumulation of amino-acid substitutions in hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) that alter antibody binding, enabling reinfection and necessitating frequent vaccine updates [

85,

183,

184]. Decades of surveillance link drift magnitude to epidemic variability: years with larger drift often produce greater vaccine mismatch and more severe seasons [

85,

183]. Mechanistically, drift reflects immune selection on variable epitopes, receptor-binding avidity trade-offs, and constraints imposed by HA structure and glycosylation [

85,

183]. Antigenic shift is an abrupt, major change in antigenicity caused by gene-segment reassortment (or less commonly, direct species jumps) in influenza viruses. The eight-segment genome facilitates exchange when a host is co-infected with distinct lineages. Historically, pandemic strains have arisen when novel hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) segments from nonhuman reservoirs (avian or swine) enter human-adapted backbones; the resulting antigenic novelty finds a largely susceptible population ([

185,

186,

187] (

Figure 7).

Migratory birds are the principal reservoir in which extensive antigenic and genetic diversity is generated and maintained; mixed-species aggregations at wetlands favour co-infection and reassortment among numerous LPAI subtypes [

61,

62] (

Figure 7). When such reassortants acquire polybasic cleavage sites or other virulence determinants in domestic poultry, HPAI epizootics can arise. If the resulting viruses retain their fitness in wild birds, flyways can disseminate them broadly (

Figure 7). The global 2021–present H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b panzootic illustrates this dynamic. Genomic analyses reveal multiple reassortment events that produced distinct genotypes, which rapidly spread with migrants, caused mass mortality in wild birds, and subsequently spilled over into mammals [

63,

66,

67]. These events fundamentally alter risk assessments: wild birds are no longer merely recipients of poultry-origin HPAI but are also capable of maintaining and exporting highly fit viral lineages, thereby impacting surveillance priorities and vaccination policies in animal health. From a forecasting perspective, the interplay between drift, shift, and migration establishes the “antigenic weather.” Extensive avian migrations facilitate the connection of distant viral gene pools, while environmental persistence within aquatic habitats extends the period for potential co-circulation and co-infection [

64,

68]. Reviews of influenza A virus ecology in wild birds underscore how host characteristics (such as age structure, immunity, and stopover duration) and viral traits (including replication efficiency and environmental stability) collectively influence transmission dynamics and evolutionary processes. [

61,

62].

6. Ongoing Surveillance and Monitoring Efforts in Africa

The African surveillance system comprises a network of interconnected components, where countries generate field data, regional organisations focus on data storage, and international platforms convert these inputs into early warning systems [

188]. Officially, two primary mechanisms link African animal health reporting to the global stage. Through designated country focal points, the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) oversees the World Animal Health Information System (WAHIS), which documents incidents of livestock and wildlife diseases and produces annual reports, mid-year updates, and immediate notifications [

189]. The Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Emergency Prevention System for Animal and Plant Health (EMPRES-AH) facilitate risk management and early warning initiatives, while EMPRES-i+ consolidates official and informal reports [

124].

At the continental level, the African Union Inter-African Bureau for Animal Resources (AU-IBAR) oversees the collection of routine health and vaccination data from fifty-five member states through the Animal Resources Information System (ARIS) [

190]. Additionally, the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) and it’s One Health Programme, along with the Zoonotic Disease Prevention and Control Strategy for 2025–2029, establish the policy foundation for cross-sectoral surveillance and rapid response mechanisms [

191]. Furthermore, the African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement (AEWA), a legally binding treaty encompassing 255 species, provides practical models for disease surveillance systems and promotes systematic counts, reporting, and training under its Plan of Action for Africa (2019–2027) and its Waterbird Monitoring Program [

192,

193].

7. Perspective Piece: Approach to Curtailing the Spread of Infectious Disease Pathogen by Migratory Birds in Africa

7.1. Strengthened Cross-Border Surveillance

Despite existing research on surveillance in migratory birds within Africa, numerous gaps and challenges persist in the region, thereby underscoring the necessity for enhanced surveillance efforts. One such deficiency pertains to the limited sequencing infrastructure available in many African laboratories, combined with the prioritisation of human sample testing over animal samples [

25,

194]. Furthermore, findings obtained from research-oriented targeted surveillance are predominantly published in scholarly journals and infrequently integrated into official reporting databases. This discrepancy results in a lack of synchronisation between national surveillance systems and research outputs [

194]. Additional limitations include heightened diagnostic costs, which restrict the volume of samples collected, and the difficulties associated with capturing migratory birds, thereby impeding the feasibility of random sampling [

132]. Consequently, addressing disease transmission from migratory birds necessitates the development of a collaborative network involving scientists and researchers from academic, industrial, and governmental sectors to facilitate resource sharing, information exchange, and the safe sampling of wild avian populations [

19]. This should be complemented by strengthened regional coordination and adequate funding to support effective surveillance initiatives within the region [

194]. Lastly, the scope of surveillance should extend beyond highly pathogenic avian influenza to include screening for other pathogens as well [

195].

7.2. Genomic Sequencing and Bioinformatics

Genomic sequencing and bioinformatics possess the potential to augment pathogen surveillance among African migratory birds by providing a level of identification that exceeds the capabilities of traditional epidemiological methods [

196]. The ability of researchers to differentiate between altered, novel, and local pathogen genes through comprehensive viral genome analysis, combined with the integration of ecological and epidemiological data, offers a novel perspective in efforts to mitigate the emergence of new pathogens. A particularly significant insight provided by genome sequencing is the identification that outbreaks of highly pathogenic

Avian influenza (HPAI) in Africa are predominantly due to recurrent introductions rather than continuous local evolution. Phylogenetic analyses of clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 viruses identified in West Africa, East Africa, and Southern Africa since 2021 have consistently shown clustering with Eurasian lineages, as opposed to earlier African isolates [

197]. Similarly, in 2023, genomic characterisation of H5N1 outbreaks in South Africa revealed at least two distinct introductions of H5N1, with genomic sequences detected in domestic poultry, seabirds, and raptors [

142]. The advancement and refinement of genomic tools, especially their adoption within Africa, present a new perspective emphasising the importance of genomic surveillance. This transition will enable the realignment of strategic priorities and policies from merely controlling farm-level outbreaks to strengthening sentinel surveillance during pre-migration and peak-migration phases. Such capacity is of critical importance within the African context, as migratory birds travel during winter, thereby creating numerous opportunities for pathogen reintroduction, particularly viral, during this period (Maseko et al., 2023).

7.3. Species Typing in Relation to Ecology

Another significant contribution, exemplified by the integration of surveillance data with genomic information, is the precise identification of species in relation to ecological contexts, serving as a linkage between domestic and wild reservoirs [

198,

199]. Migratory seabirds such as gulls are succumbing along the West African coast and in South Africa; viruses with genomes nearly indistinguishable from those identified in domestic chicken flocks have been detected [

153]. These findings inform our contextualised recommendations for prioritising corpse sampling and genetic testing within coastal colonies [

200].

7.4. Environmental Genomics

Environmental genomics can also enhance surveillance capabilities by associating pathogens with drug resistance in remote African regions. A study employing multi-country fresh guano demonstrated that environmental RNA sequencing can recover complete influenza genomes from roosts across Mozambique, Madagascar, Somalia, and Yemen, including H5N1 viruses with mutations associated with reduced susceptibility to oseltamivir [

201]. This methodology reinforces the premise that highly pathogenic influenza lineages are circulating undetected alongside antiviral resistance, thereby emerging as a potential concern. Incorporating guano-based sequencing will prove particularly valuable for Africa’s extensive and inaccessible terrains, as the cost-effectiveness of this approach renders it a promising complement to traditional surveillance methods.

7.5. Advanced ‘Omics Techniques: Genomics, Bioinformatics, and AI Adoption

Technological advancements in standardized bioinformatics and sequencing platforms have expedited the integration of genomics into real-time outbreak response initiatives across Africa. Notable efforts such as the Africa Pathogen Genomics Initiative (Africa PGI), overseen by the Africa CDC, have furnished laboratories within more than 30 member states with sequencing capabilities, trained personnel, and data-sharing pipelines [

191]. Complementary networks, including H3ABioNet, have further reinforced this infrastructure by incorporating genomic surveillance into a One Health framework. Data generated by African laboratories are increasingly being deposited in open repositories such as GISAID and GenBank, facilitating rapid comparisons and enhancing situational awareness across borders. The policy implications of genomic surveillance are already manifest. Firstly, genomic evidence has highlighted the necessity of prioritising surveillance at high-risk ecological sites- such as coastal rookeries, wetlands, and pre-migration staging areas- rather than concentrating solely on poultry farms. Secondly, the integration of wildlife, veterinary, and public health genomic data into unified pipelines has bolstered early warning systems, thereby enabling poultry producers and public health authorities to strengthen biosecurity measures and carcass-handling protocols during outbreak periods.

Notwithstanding these advancements, substantial deficiencies persist. Continuous investment in environmental sampling, portable sequencing technologies, and bioinformatics training is imperative to broaden coverage and ensure that laboratories across Africa are capable of both generating and interpreting genomic data in real-time. Herein, advanced ’omics technologies present transformative potential. Artificial intelligence (AI) offers additional prospects for enhancing surveillance. Deep learning algorithms, sophisticated computational techniques, and image-processing platforms are being utilised in diagnostic tools capable of detecting avian influenza infections with unprecedented accuracy and efficiency [

202]. Likewise, AI-driven predictive models and big-data analytics can improve early warning systems by simulating transmission dynamics, identifying hotspots, and guiding rapid response strategies. Although these applications are still in preliminary stages, the widespread adoption and integration of AI into Africa’s genomic and epidemiological networks would facilitate real-time monitoring of outbreaks related to migratory birds, thereby bridging gaps among veterinary, environmental, and public health systems [

203]. By merging genomics, bioinformatics, and AI-driven methodologies, African nations have the potential to establish a next-generation surveillance infrastructure capable of anticipating, detecting, and mitigating disease threats at the nexus of migration, livestock, and human health.

7.6. Mathematical Modelling

To comprehend and manage infectious diseases such as avian influenza, flaviviruses, and other pathogens transmitted by migratory birds, the employment of mathematical models is of fundamental importance. These models are essential for mapping disease dissemination and developing algorithms that analyse real-world data. Such approaches provide quantitative frameworks for simulating disease transmission and assessing control strategies [

204]. Among various types of models, analytical or mathematical models, such as the’ Susceptible–Exposed–Infectious–Recovered” (SEIR) model, offer a comprehensive structure for understanding the dynamics of avian influenza transmission. These models, grounded in experimental or empirical data, play a vital role in elucidating epidemics and comprehending pathogen behaviour within populations. Furthermore, spatial models consider the geographic distribution of farms and the mechanisms of disease spread. These models deliver more precise insights into estimates of virus introduction and contact tracing within specific regions, underscoring the influence of spatial factors on the effectiveness of control measures and transmission rates [

204].

7.7. Incorporating Predictive Modelling with a One Health Framework

Pathogen transmission, replication, survival, and mutation can only be fully understood and effectively managed through integrated risk assessment and a multidimensional approach. By merging genetic, environmental, and epidemiological datasets, AI-driven models can generate higher-resolution risk assessments and identify emerging hotspots of zoonotic diseases at fine spatial and temporal scales [

203,

205]. Machine learning applications in ecological niche modelling already provide promising precedents. For example, predictive algorithms have been used to model the global distribution of avian influenza virus and assess how climatic, ecological, and host-related factors interact to shape risk landscapes [

206]. More recent work demonstrates the use of AI-based niche models to identify key environmental predictors of infection in waterfowl, underscoring the potential to adapt these tools for African-specific settings [

207]. Such models could be used to produce predictive maps that prioritize wetlands, migratory stopover sites, and poultry production zones where surveillance and intervention are most urgently required.

Beyond static mapping, the integration of dynamic compartmental models with artificial intelligence (AI) is particularly promising. Real-time West Nile virus (WNV) forecasting systems, which simulate local interactions among avian hosts, mosquito vectors, livestock, and humans, exemplify how predictive modelling can anticipate outbreak trajectories and inform timely interventions [