Submitted:

11 September 2025

Posted:

12 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Difference Between MPs and Bulk Plastics

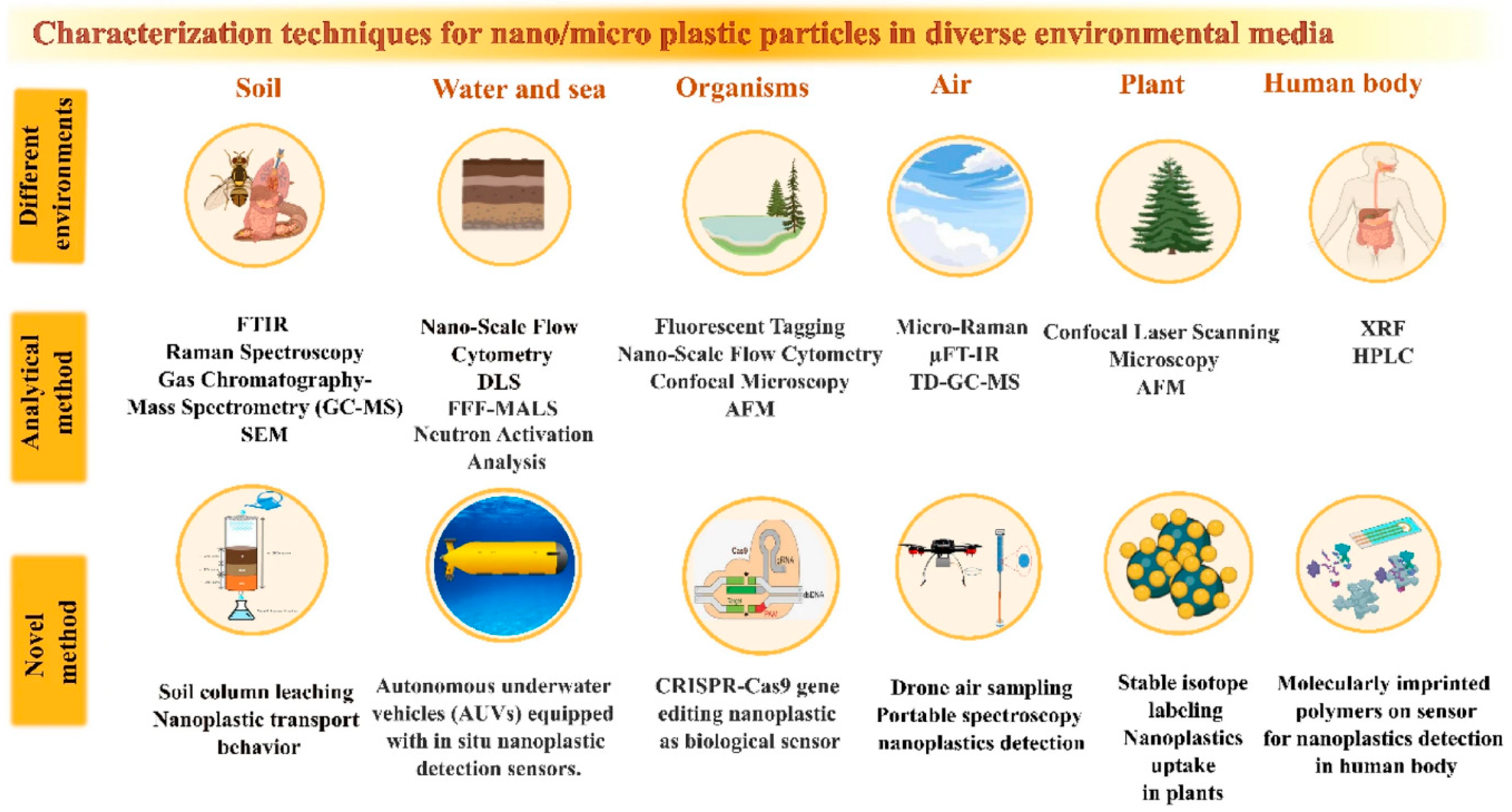

3. Microplastic Identification and Quantification

4. Enhanced Microplastic Degradation Using a Catalyst

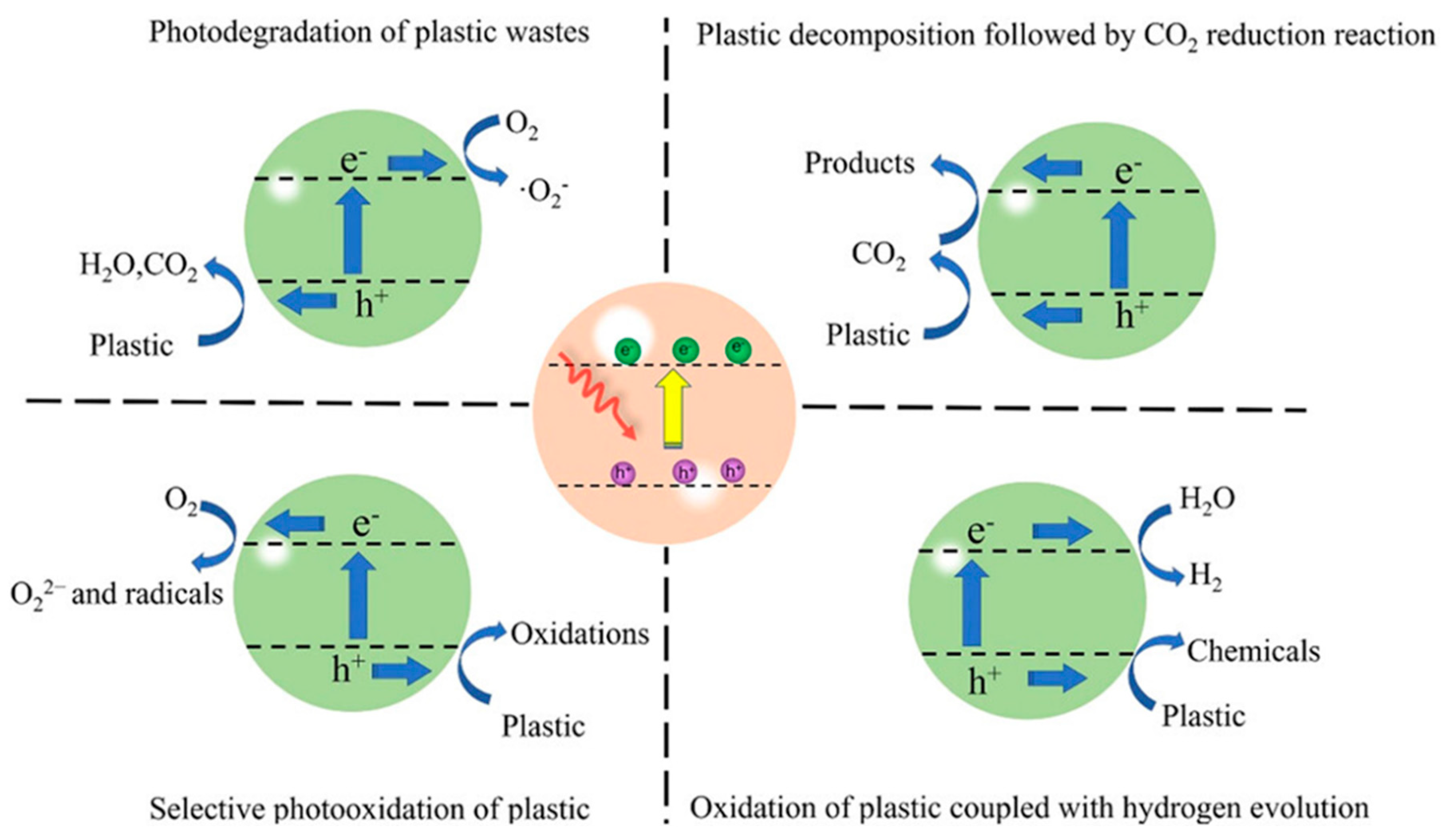

4.1. Photocatalysts

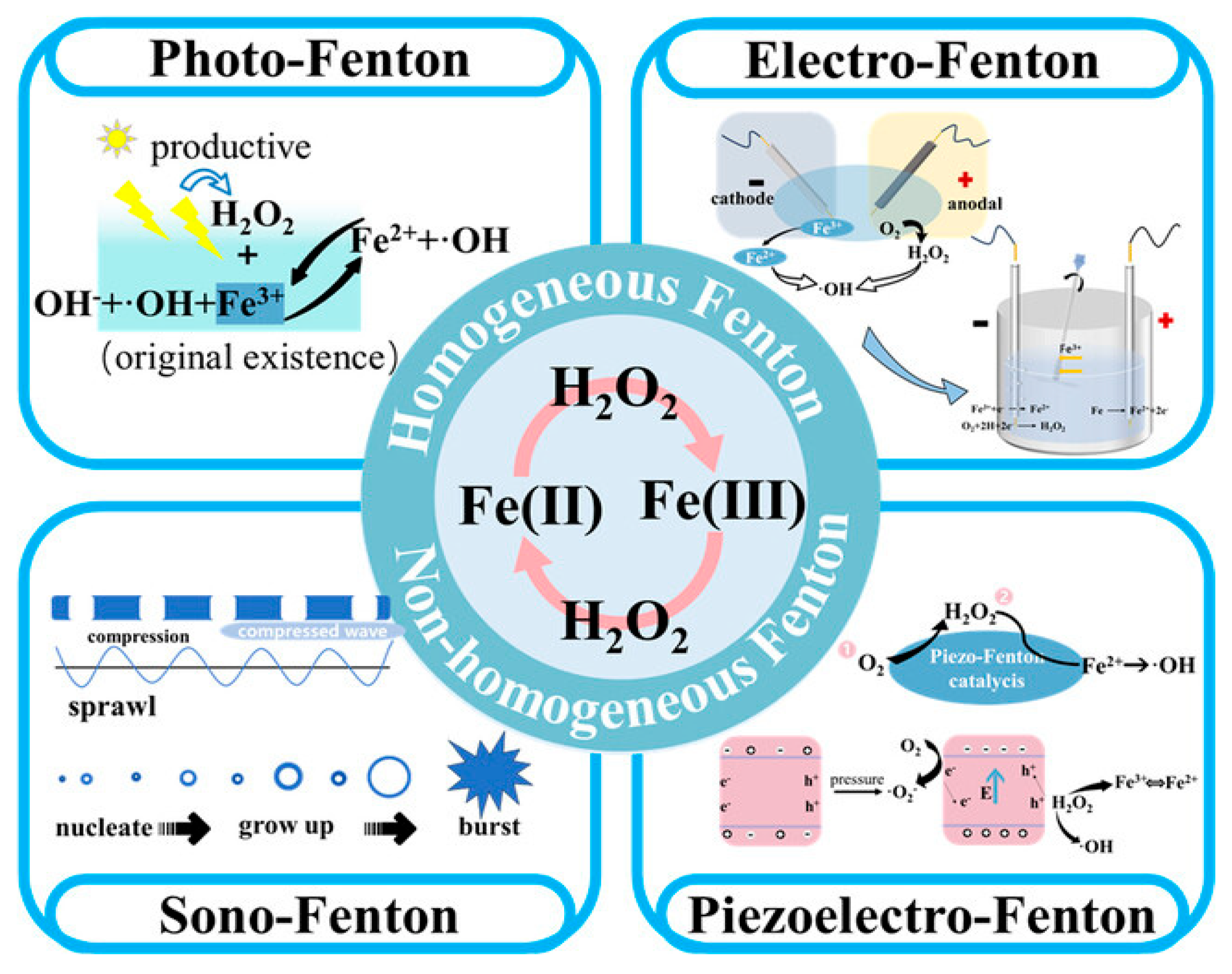

4.2. Fenton and Fenton-like Catalysts

4.3. Thermal Catalytic Process

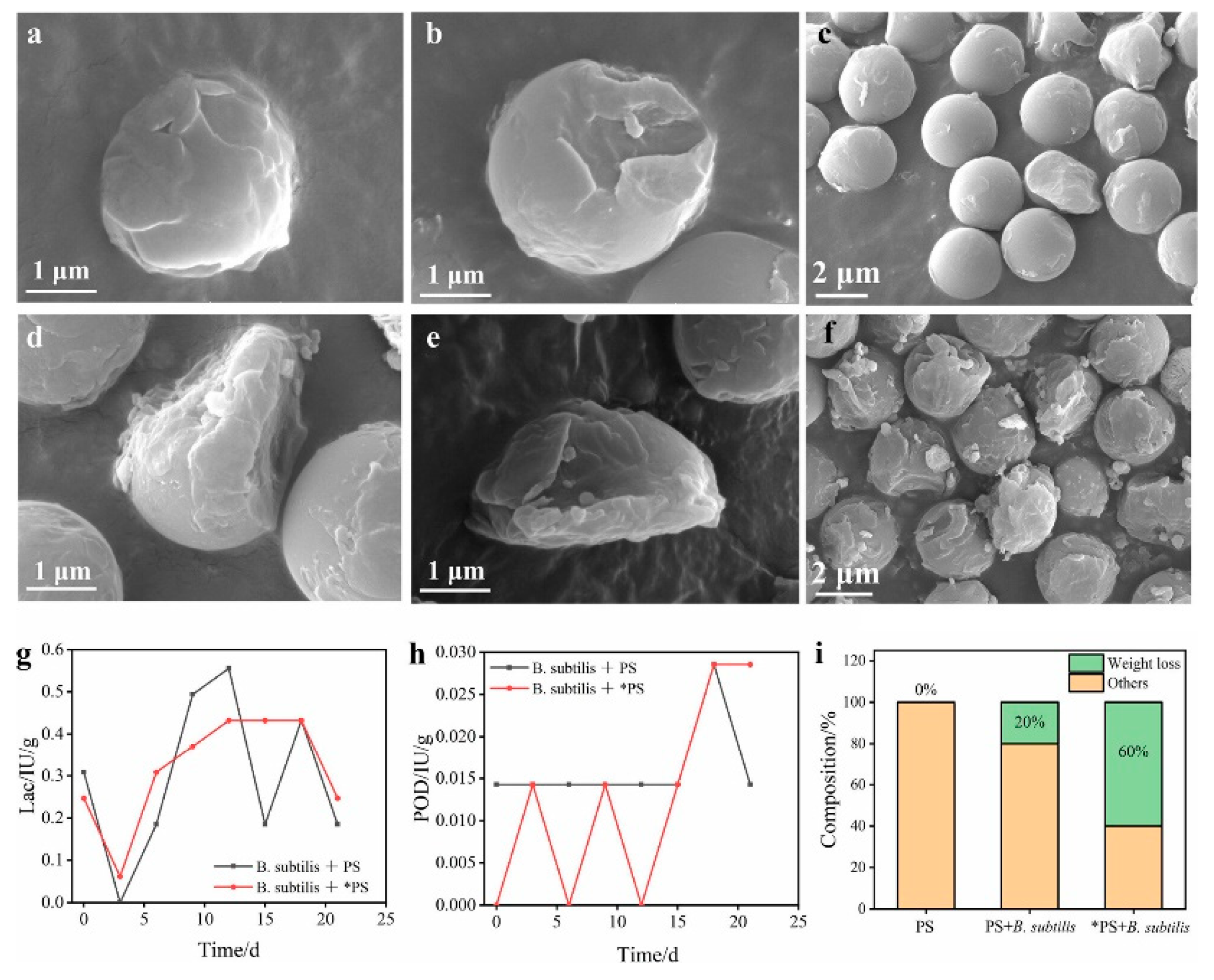

4.4. Bio and Bio-Inspired Catalysts

4.5. Electrocatalysts

4.6. Hybrid Catalysts Coupling Different Reaction Pathways

5. Challenges and Future Opportunities for Catalytic Microplastic Degradation and Upcycling

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thompson, R.C.; Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R.P.; Davis, A.; Rowland, S.J.; John, A.W.G.; McGonigle, D.; Russell, A.E. Lost at Sea: Where Is All the Plastic? Science (1979) 2004, 304, 838–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Nor, N.H.; Kooi, M.; Diepens, N.J.; Koelmans, A.A. Lifetime Accumulation of Microplastic in Children and Adults. Environ Sci Technol 2021, 55, 5084–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.C.; Courtene-Jones, W.; Boucher, J.; Pahl, S.; Raubenheimer, K.; Koelmans, A.A. Twenty Years of Microplastic Pollution Research—What Have We Learned? Science (1979) 2024, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salahuddin, U.; Sun, J.; Zhu, C.; Wu, M.; Zhao, B.; Gao, P. Plastic Recycling: A Review on Life Cycle, Methods, Misconceptions, and Techno-Economic Analysis. Adv Sustain Syst 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutkar, P.R.; Gadewar, R.D.; Dhulap, V.P. Recent Trends in Degradation of Microplastics in the Environment: A State-of-the-Art Review. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 2023, 11, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puteri, M.N.; Gew, L.T.; Ong, H.C.; Ming, L.C. Technologies to Eliminate Microplastic from Water: Current Approaches and Future Prospects. Environ Int 2025, 199, 109397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welden, N.A.; Lusher, A. Microplastics. In Plastic Waste and Recycling; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 223–249.

- Bermúdez, J.R.; Swarzenski, P.W. A Microplastic Size Classification Scheme Aligned with Universal Plankton Survey Methods. MethodsX 2021, 8, 101516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias, J.P.G.L.; Nash, R. Microplastics: Finding a Consensus on the Definition. Mar Pollut Bull 2019, 138, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efimova, I.; Bagaeva, M.; Bagaev, A.; Kileso, A.; Chubarenko, I.P. Secondary Microplastics Generation in the Sea Swash Zone With Coarse Bottom Sediments: Laboratory Experiments. Front Mar Sci 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, K.K.; Sivakumar, R.; Kashian, D. The Microplastics Cycle: An In-Depth Look at a Complex Topic. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 10999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, R.C.; Seeley, M.E.; La Guardia, M.J.; Mai, L.; Zeng, E.Y. A Global Perspective on Microplastics. J Geophys Res Oceans 2020, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, K.; Johnson, E. V.; Malmendal, A.; Linse, S.; Hansson, L.-A.; Cedervall, T. Brain Damage and Behavioural Disorders in Fish Induced by Plastic Nanoparticles Delivered through the Food Chain. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 11452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, M.; Rathod, T.D.; Ajmal, P.Y.; Bhangare, R.C.; Sahu, S.K. Distribution and Characterization of Microplastics in Beach Sand from Three Different Indian Coastal Environments. Mar Pollut Bull 2019, 140, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, C.R.; Santana, M.F.M.; Maluf, A.; Cortez, F.S.; Cesar, A.; Pereira, C.D.S.; Turra, A. Assessment of Microplastic Toxicity to Embryonic Development of the Sea Urchin Lytechinus Variegatus (Echinodermata: Echinoidea). Mar Pollut Bull 2015, 92, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.S.; Alsharbaty, M.H.M.; Al-Tohamy, R.; Khalil, M.A.; Schagerl, M.; Al-Zahrani, M.; Sun, J. Microplastics as an Emerging Potential Threat: Toxicity, Life Cycle Assessment, and Management. Toxics 2024, 12, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamas, A.; Moon, H.; Zheng, J.; Qiu, Y.; Tabassum, T.; Jang, J.H.; Abu-Omar, M.; Scott, S.L.; Suh, S. Degradation Rates of Plastics in the Environment. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2020, 8, 3494–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, J.; Song, J.; Du, X.; Lou, F.; Zhu, Y.; Lei, J.; Huang, Q. Complete Degradation of Polystyrene Microplastics through Non-Thermal Plasma-Assisted Catalytic Oxidation. J Hazard Mater 2024, 480, 136313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Shan, X.; Liu, J. Highly Efficient Low-Temperature Biodegradation of Polyethylene Microplastics by Using Cold-Active Laccase Cell-Surface Display System. Bioresour Technol 2023, 382, 129164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uheida, A.; Mejía, H.G.; Abdel-Rehim, M.; Hamd, W.; Dutta, J. Visible Light Photocatalytic Degradation of Polypropylene Microplastics in a Continuous Water Flow System. J Hazard Mater 2021, 406, 124299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

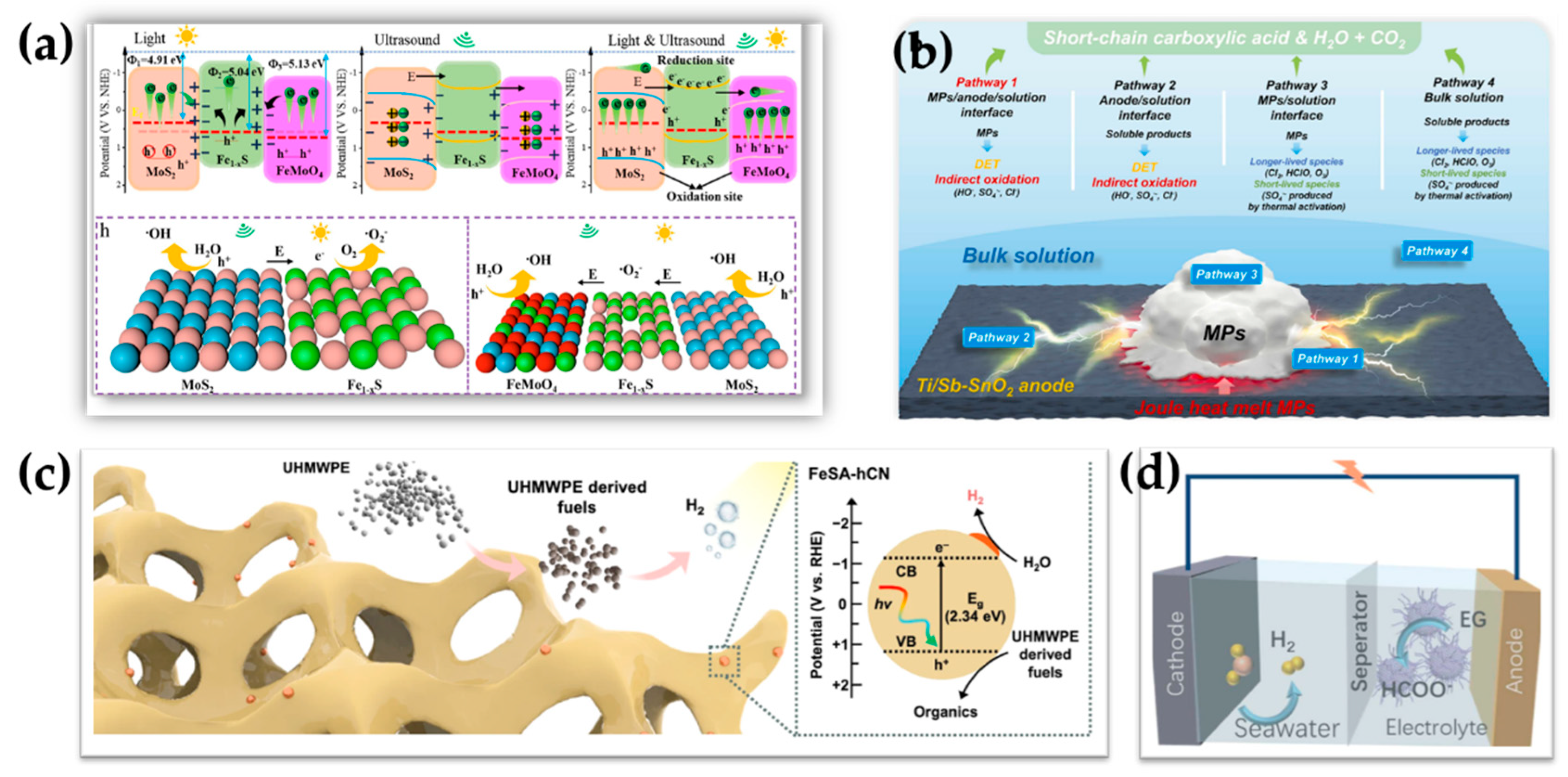

- Lin, J.; Hu, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, W.; Hall, T.; Duan, X.; Sun, H.; Zhang, H.; Cortés, E.; Wang, S. Tandem Microplastic Degradation and Hydrogen Production by Hierarchical Carbon Nitride-Supported Single-Atom Iron Catalysts. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 8769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, A.J.; Mondelli, C.; Jaydev, S.D.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Catalytic Processing of Plastic Waste on the Rise. Chem 2021, 7, 1487–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Aguirre-Villegas, H.A.; Allen, R.D.; Bai, X.; Benson, C.H.; Beckham, G.T.; Bradshaw, S.L.; Brown, J.L.; Brown, R.C.; Cecon, V.S.; et al. Expanding Plastics Recycling Technologies: Chemical Aspects, Technology Status and Challenges. Green Chemistry 2022, 24, 8899–9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehanno, C.; Alty, J.W.; Roosen, M.; De Meester, S.; Dove, A.P.; Chen, E.Y.-X.; Leibfarth, F.A.; Sardon, H. Critical Advances and Future Opportunities in Upcycling Commodity Polymers. Nature 2022, 603, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Korey, M.; Li, K.; Copenhaver, K.; Tekinalp, H.; Celik, S.; Kalaitzidou, K.; Ruan, R.; Ragauskas, A.J.; Ozcan, S. Plastic Waste Upcycling toward a Circular Economy. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 428, 131928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napper, I.E.; Davies, B.F.R.; Clifford, H.; Elvin, S.; Koldewey, H.J.; Mayewski, P.A.; Miner, K.R.; Potocki, M.; Elmore, A.C.; Gajurel, A.P.; et al. Reaching New Heights in Plastic Pollution—Preliminary Findings of Microplastics on Mount Everest. One Earth 2020, 3, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, J.R.; Swarzenski, P.W. A Microplastic Size Classification Scheme Aligned with Universal Plankton Survey Methods. MethodsX 2021, 8, 101516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, L.; Göttlich, S.; Oehlmann, J.; Wagner, M.; Völker, C. What Are the Drivers of Microplastic Toxicity? Comparing the Toxicity of Plastic Chemicals and Particles to Daphnia Magna. Environmental Pollution 2020, 267, 115392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, J. The Chemical Behaviors of Microplastics in Marine Environment: A Review. Mar Pollut Bull 2019, 142, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafa, N.; Ahmed, B.; Zohora, F.; Bakya, J.; Ahmed, S.; Ahmed, S.F.; Mofijur, M.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Almomani, F. Microplastics as Carriers of Toxic Pollutants: Source, Transport, and Toxicological Effects. Environmental Pollution 2024, 343, 123190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Ruz, V.; Gutow, L.; Thompson, R.C.; Thiel, M. Microplastics in the Marine Environment: A Review of the Methods Used for Identification and Quantification. Environ Sci Technol 2012, 46, 3060–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Hu, B.; Wang, H. Analytical Methods for Microplastics in the Environment: A Review. Environ Chem Lett 2023, 21, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.-M.; Wagner, J.; Ghosal, S.; Bedi, G.; Wall, S. SEM/EDS and Optical Microscopy Analyses of Microplastics in Ocean Trawl and Fish Guts. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 603–604, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivleva, N.P.; Wiesheu, A.C.; Niessner, R. Microplastic in Aquatic Ecosystems. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2017, 56, 1720–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primpke, S.; Lorenz, C.; Rascher-Friesenhausen, R.; Gerdts, G. An Automated Approach for Microplastics Analysis Using Focal Plane Array (FPA) FTIR Microscopy and Image Analysis. Analytical Methods 2017, 9, 1499–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, C.F.; Nolasco, M.M.; Ribeiro, A.M.P.; Ribeiro-Claro, P.J.A. Identification of Microplastics Using Raman Spectroscopy: Latest Developments and Future Prospects. Water Res 2018, 142, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batel, A.; Borchert, F.; Reinwald, H.; Erdinger, L.; Braunbeck, T. Microplastic Accumulation Patterns and Transfer of Benzo[a]Pyrene to Adult Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Gills and Zebrafish Embryos. Environmental Pollution 2018, 235, 918–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuguma, Y.; Takada, H.; Kumata, H.; Kanke, H.; Sakurai, S.; Suzuki, T.; Itoh, M.; Okazaki, Y.; Boonyatumanond, R.; Zakaria, M.P.; et al. Microplastics in Sediment Cores from Asia and Africa as Indicators of Temporal Trends in Plastic Pollution. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2017, 73, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peez, N.; Janiska, M.-C.; Imhof, W. The First Application of Quantitative 1H NMR Spectroscopy as a Simple and Fast Method of Identification and Quantification of Microplastic Particles (PE, PET, and PS). Anal Bioanal Chem 2019, 411, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Zhao, B.; Deng, C.; Zhu, C.; Cheng, M.M.-C.; Gao, P.-X. Microplastic Detection and Monitoring in Biological and Environmental Systems: A Mini Review of Techniques and Strategies. International Journal of High Speed Electronics and Systems 2026, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristoni, S.; Dusi, G.; Brambilla, P.; Albini, A.; Conti, M.; Brambilla, M.; Bruno, A.; Di Gaudio, F.; Ferlin, L.; Tazzari, V.; et al. SANIST: Optimization of a Technology for Compound Identification Based on the European Union Directive with Applications in Forensic, Pharmaceutical and Food Analyses. Journal of Mass Spectrometry 2017, 52, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elumalai, P. V.; Dhinesh, B.; Jayakar, J.; Nambiraj, M.; Hariharan, V. Effects of Antioxidants to Reduce the Harmful Pollutants from Diesel Engine Using Preheated Palm Oil–Diesel Blend. J Therm Anal Calorim 2022, 147, 2439–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddison, C.; Sathish, C.I.; Lakshmi, D.; Wayne, O.; Palanisami, T. An Advanced Analytical Approach to Assess the Long-Term Degradation of Microplastics in the Marine Environment. Npj Mater Degrad 2023, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfohl, P.; Wagner, M.; Meyer, L.; Domercq, P.; Praetorius, A.; Hüffer, T.; Hofmann, T.; Wohlleben, W. Environmental Degradation of Microplastics: How to Measure Fragmentation Rates to Secondary Micro- and Nanoplastic Fragments and Dissociation into Dissolved Organics. Environ Sci Technol 2022, 56, 11323–11334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nene, A.; Sadeghzade, S.; Viaroli, S.; Yang, W.; Uchenna, U.P.; Kandwal, A.; Liu, X.; Somani, P.; Galluzzi, M. Recent Advances and Future Technologies in Nano-Microplastics Detection. Environ Sci Eur 2025, 37, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Han, L.; Wang, F.; Ma, C.; Cai, Y.; Ma, W.; Xu, E.G.; Xing, B.; Yang, Z. Photocatalytic Strategy to Mitigate Microplastic Pollution in Aquatic Environments: Promising Catalysts, Efficiencies, Mechanisms, and Ecological Risks. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol 2023, 53, 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Sun, R.; Huang, R.; Wang, H. Superior Fenton-like Degradation of Tetracycline by Iron Loaded Graphitic Carbon Derived from Microplastics: Synthesis, Catalytic Performance, and Mechanism. Sep Purif Technol 2021, 270, 118773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Xu, X.; Zhu, Z.-S.; Yang, Y.; Tian, W.; Hu, K.; Zhong, S.; Yi, J.; Duan, X.; Wang, S. Catalytic Transformation of Microplastics to Functional Carbon for Catalytic Peroxymonosulfate Activation: Conversion Mechanism and Defect of Scavenging. Appl Catal B 2024, 342, 123410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Zhen, M.; Qian, H.; Nie, Y.; Bai, X.; Xia, T.; Laiq Ur Rehman, M.; Li, Q.; Ju, M. Upcycling and Catalytic Degradation of Plastic Wastes. Cell Rep Phys Sci 2021, 2, 100514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraj, J.; Baskaralingam, V.; Stalin, T.; Muthuvel, I. Mechanistic Vision on Polypropylene Microplastics Degradation by Solar Radiation Using TiO2 Nanoparticle as Photocatalyst. Environ Res 2023, 233, 116366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Wang, H.; Huo, P. Plastic Degradation and Conversion by Photocatalysis. In; 2024; pp. 1–22.

- Wang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Jiang, J.; Li, R.; Xiong, J. Preparation of Heterojunction C3N4/WO3 Photocatalyst for Degradation of Microplastics in Water. Chemosphere 2023, 337, 139206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yang, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G. Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of Microplastics by Constructing a Novel Z-Scheme Fe-Doped BiO2−x/BiOI Heterojunction with Full-Spectrum Response: Mechanistic Insights and Theory Calculations. J Hazard Mater 2024, 480, 136080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A.; Jin, M.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Fu, L.; Wu, W. Photocatalytic Technologies for Transformation and Degradation of Microplastics in the Environment: Current Achievements and Future Prospects. Catalysts 2023, 13, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wang, X. Nanomaterial ZnO Synthesis and Its Photocatalytic Applications: A Review. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surana, M.; Pattanayak, D.S.; Yadav, V.; Singh, V.K.; Pal, D. An Insight Decipher on Photocatalytic Degradation of Microplastics: Mechanism, Limitations, and Future Outlook. Environ Res 2024, 247, 118268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Sun, T.; Ma, Y.; Du, M.; Gong, M.; Zhou, C.; Chai, Y.; Qiu, B. Artificial Photosynthesis Bringing New Vigor into Plastic Wastes. SmartMat 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Huang, L.; Nekliudov, A. Construction of Loading G-C3N4/TiO2 on Waste Cotton-Based Activated Carbon S-Scheme Heterojunction for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Microplastics: Performance, DFT Calculation and Mechanism Study. Opt Mater (Amst) 2024, 154, 115786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Jiang, J.; Li, R.; Xiong, J. Preparation of Heterojunction C3N4/WO3 Photocatalyst for Degradation of Microplastics in Water. Chemosphere 2023, 337, 139206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, B.; Wan, S.; Wang, Y.; Guo, H.; Ou, M.; Zhong, Q. Highly-Efficient Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic H2 Evolution Integrated with Microplastic Degradation over MXene/ZnxCd1-XS Photocatalyst. J Colloid Interface Sci 2022, 605, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maulana, D.A.; Ibadurrohman, M. ; Slamet Synthesis of Nano-Composite Ag/TiO 2 for Polyethylene Microplastic Degradation Applications. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2021, 1011, 012054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofa, T.S.; Ye, F.; Kunjali, K.L.; Dutta, J. Enhanced Visible Light Photodegradation of Microplastic Fragments with Plasmonic Platinum/Zinc Oxide Nanorod Photocatalysts. Catalysts 2019, 9, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G. Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of Polystyrene Microplastics in Water over Core–Shell BiO2−x/CuBi2O4 Heterojunction with Full Spectrum Light Response. J Colloid Interface Sci 2025, 686, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, D.; Wu, X.; Wu, D.; Su, N.; Wang, Y.; Chen, F.; Fu, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q. Synergistic Dual-Defect Band Engineering for Highly Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of Microplastics via Nb-Induced Oxygen Vacancies in SnO 2 Quantum Dots. J Mater Chem A Mater 2025, 13, 4429–4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilumbaquin, W.; Castillo-Cabrera, G.X.; Borrero-González, L.J.; Mora, J.R.; Valle, V.; Debut, A.; Loor-Urgilés, L.D.; Espinoza-Montero, P.J. Photoelectrocatalytic Degradation of High-Density Polyethylene Microplastics on TiO2-Modified Boron-Doped Diamond Photoanode. iScience 2024, 27, 109192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Yi, J.; Wang, J.; Qian, Q.; Chen, Q.; Cao, C.; Zhou, W. Enhancing Microplastic Degradation through Synergistic Photocatalytic and Pretreatment Approaches. Langmuir 2024, 40, 22582–22590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Rehman, A.U.; Xu, M.; Not, C.A.; Ng, A.M.C.; Djurišić, A.B. Photocatalytic Degradation of Different Types of Microplastics by TiOx/ZnO Tetrapod Photocatalysts. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Lu, G.; Dang, T.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Yan, Z.; Xie, H. Insight into the Degradation Process of Functional Groups Modified Polystyrene Microplastics with Dissolvable BiOBr-OH Semiconductor-Organic Framework. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 470, 144401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Hidalgo-Jiménez, J.; Sauvage, X.; Saito, K.; Guo, Q.; Edalati, K. Phase and Sulfur Vacancy Engineering in Cadmium Sulfide for Boosting Hydrogen Production from Catalytic Plastic Waste Photoconversion. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 504, 158730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhu, J. Photodegradation of Microplastics through Nanomaterials: Insights into Photocatalysts Modification and Detailed Mechanisms. Materials 2024, 17, 2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Wang, H.; Huo, P. Plastic Degradation and Conversion by Photocatalysis. In; 2024; pp. 1–22.

- Zhou, G.; Xu, H.; Song, H.; Yi, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, X. Photocatalysis toward Microplastics Conversion: A Critical Review. ACS Catal 2024, 14, 8694–8719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; Dong, W. Enhancement of Microplastics Degradation with MIL-101 Modified BiOI Photocatalyst under Light and Dark Alternated System. J Environ Chem Eng 2024, 12, 112958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Sun, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Deng, S.; Yang, H. Boosting Photocatalytic Capability by Dispersing TiO2 into Chitin Matrix for Polystyrene Microplastics Degradation. Appl Surf Sci 2025, 711, 164104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Multivalent Metal Catalysts in Fenton/Fenton-like Oxidation System: A Critical Review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 466, 143147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J. Fenton/Fenton-like Processes with in-Situ Production of Hydrogen Peroxide/Hydroxyl Radical for Degradation of Emerging Contaminants: Advances and Prospects. J Hazard Mater 2021, 404, 124191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerstein, D. Re-Examining Fenton and Fenton-like Reactions. Nat Rev Chem 2021, 5, 595–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Guo, S.; Wang, D.; An, Q. Fenton-Like Reaction: Recent Advances and New Trends. Chemistry – A European Journal 2024, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarghami Qaretapeh, M.; Kouchakipour, S.; Hosseinzadeh, M.; Dashtian, K. Cuttlefish Bone-Supported CoFe2O4 Nanoparticles Enhance Persulfate Fenton-like Process for the Degradation of Polystyrene Nanoplastics. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 490, 151833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Li, N.; Gao, W.; Peng, W.; Peng, X.; Cheng, Z.; Yan, B.; Fu, Y.; Zhan, S.; Chen, G.; et al. Bimetal-Carbon Engineering for Polypropylene Conversion into Hydrocarbons and Ketones in a Fenton-like System. Applied Catalysis B: Environment and Energy 2024, 358, 124411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilli, E.; Pighin, A.F.; Copello, G.J.; Villanueva, M.E. Cobalt/Carbon Quantum Dots Core-Shell Nanoparticles as an Improved Catalyst for Fenton-like Reaction. Nano-Structures & Nano-Objects 2024, 37, 101097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Xu, H.; Hunter, T.N.; Harbottle, D.; Kale, G.M.; Tillotson, M.R. Advanced Polystyrene Nanoplastic Remediation through Electro-Fenton Process: Degradation Mechanisms and Pathways. J Environ Chem Eng 2025, 13, 118907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wang, R.; Miao, L.; Sun, P.; Zhou, B.; Xiong, Y.; Dong, X. Synergistically Piezocatalytic and Fenton-like Activation of H2O2 by a Ferroelectric Bi12(Bi0.5Fe0.5)O19.5 Catalyst to Boost Degradation of Polyethylene Terephthalate Microplastic (PET-MPs). J Colloid Interface Sci 2025, 682, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Yu, X.; Ke, X.; Zhao, J. A Novel Route for Microplastic Mineralization: Visible-Light-Driven Heterogeneous Photocatalysis and Photothermal Fenton-like Reaction. Environ Sci Nano 2024, 11, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Zhou, P.; Yang, Y.; Hall, T.; Nie, G.; Yao, Y.; Duan, X.; Wang, S. Degradation of Microplastics by a Thermal Fenton Reaction. ACS ES&T Engineering 2022, 2, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanaty, M.; Zaki, A.H.; El-Dek, S.I.; Abdelhamid, H.N. Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework@hydrogen Titanate Nanotubes for Efficient Adsorption and Catalytic Oxidation of Organic Dyes and Microplastics. J Environ Chem Eng 2024, 12, 112547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bule Možar, K.; Miloloža, M.; Martinjak, V.; Radovanović-Perić, F.; Bafti, A.; Ujević Bošnjak, M.; Markić, M.; Bolanča, T.; Cvetnić, M.; Kučić Grgić, D.; et al. Evaluation of Fenton, Photo-Fenton and Fenton-like Processes in Degradation of PE, PP, and PVC Microplastics. Water (Basel) 2024, 16, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Song, B.; Zhou, C.; Hu, T.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Y. Advanced Oxidation Processes for the Elimination of Microplastics from Aqueous Systems: Assessment of Efficiency, Perspectives and Limitations. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 842, 156723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, C.; Huang, Q.-X.; Chi, Y.; Yan, J.-H. Adsorption and Thermal Degradation of Microplastics from Aqueous Solutions by Mg/Zn Modified Magnetic Biochars. J Hazard Mater 2021, 419, 126486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabgan, W.; Nabgan, B.; Tuan Abdullah, T.A.; Ikram, M.; Jadhav, A.H.; Jalil, A.A.; Ali, M.W. Highly Active Biphasic Anatase-Rutile Ni-Pd/TNPs Nanocatalyst for the Reforming and Cracking Reactions of Microplastic Waste Dissolved in Phenol. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 3324–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Tang, S.; Zhao, Y. Upcycling Polystyrene Microplastics to Fe/Mo-Doped Sponge-Carbon: Mo5+ Enhanced Electron Transfer for Boosting Fenton-like Performance. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 498, 155460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Yang, J.; Huang, R.; Wang, C. Controlled Carbonization of Microplastics Loaded Nano Zero-Valent Iron for Catalytic Degradation of Tetracycline. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 135123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Xu, X.; Zhu, Z.-S.; Yang, Y.; Tian, W.; Hu, K.; Zhong, S.; Yi, J.; Duan, X.; Wang, S. Catalytic Transformation of Microplastics to Functional Carbon for Catalytic Peroxymonosulfate Activation: Conversion Mechanism and Defect of Scavenging. Appl Catal B 2024, 342, 123410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Che, X.; Hou, X.; Shi, L.; Huang, L. Recent Advances in the Thermo-Catalytic Upcycling of Polyethylene Waste. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2025, 7, 6597–6612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, H.; Wan, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Wan, Y.; Liu, X.; Song, X.; Ma, W.; Huo, P. Catalytic Degradation of Polyethylene Terephthalate Microplastics by Co-N/C@CeO2 Composite in Thermal-Assisted Activation PMS System: Process Mechanism and Toxicological Analysis. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 514, 163192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.-P.; Rintala, J.; Dai, L.; Oh, W.-D.; He, C. The Role of Ubiquitous Metal Ions in Degradation of Microplastics in Hot-Compressed Water. Water Res 2023, 245, 120672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daligaux, V.; Richard, R.; Manero, M.-H. Deactivation and Regeneration of Zeolite Catalysts Used in Pyrolysis of Plastic Wastes—A Process and Analytical Review. Catalysts 2021, 11, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAZALI, N.; WAN ABDULLAH, W.R.; MOHD ZIKIR, N. EFFECT OF THERMO-PHOTOCATALYTIC PROCESS USING ZINC OXIDE ON DEGRADATION OF MACRO/MICRO-PLASTIC IN AQUEOUS ENVIRONMENT. J Sustain Sci Manag 2020, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Wang, S.; Sun, B.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, X.; Li, Z. Adsorption Efficiency and In-Situ Catalytic Thermal Degradation Behaviour of Microplastics from Water over Fe-Modified Lignin-Based Magnetic Biochar. Sep Purif Technol 2025, 353, 128468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Yang, S.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, Y.; M, J.; Nagarajan, D.; Varjani, S.; Chang, J.-S. Recent Advances in Biodegradation of Emerging Contaminants - Microplastics (MPs): Feasibility, Mechanism, and Future Prospects. Chemosphere 2023, 331, 138776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Xu, M.; Zhao, W.; Yang, X.; Xin, F.; Dong, W.; Jia, H.; Wu, X. Microbial Degradation of (Micro)Plastics: Mechanisms, Enhancements, and Future Directions. Fermentation 2024, 10, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, B.; Singh, J.; Singh, J.; Angmo, D.; Vig, A.P. Biodegradation of Different Types of Microplastics: Molecular Mechanism and Degradation Efficiency. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 877, 162912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Xie, Y.; Wang, J. Microplastic Degradation Methods and Corresponding Degradation Mechanism: Research Status and Future Perspectives. J Hazard Mater 2021, 418, 126377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon, I.; Hidalgo, T.; Armani, G.; Rojas, S.; Horcajada, P. Enzyme_Metal-Organic Framework Composites as Novel Approach for Microplastic Degradation. ChemSusChem 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandieh, M.; Liu, J. Removal and Degradation of Microplastics Using the Magnetic and Nanozyme Activities of Bare Iron Oxide Nanoaggregates. Angewandte Chemie 2022, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Yu, Z.; Xue, J.; Luan, T.; Chen, S.; Zhou, S. Mechanisms of Polystyrene Microplastic Degradation by the Microbially Driven Fenton Reaction. Water Res 2022, 223, 118979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.; Hou, Y.; Hou, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q. Enhancement of Microplastics Degradation Efficiency: Microbial Laccase-Driven Radical Chemical Coupling Catalysis. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 507, 160579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, G.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Song, D. Elucidating Polyethylene Microplastic Degradation Mechanisms and Metabolic Pathways via Iron-Enhanced Microbiota Dynamics in Marine Sediments. J Hazard Mater 2024, 466, 133655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, P.; Chen, G.; Fan, J.; Tan, W.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; Li, K. Modulating Ion Migration Realizes Both Enhanced and Long-Term-Stable Nanozyme Activity for Efficient Microplastic Degradation. Chem Sci 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Meng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xie, G. Degradation of Microplastics by Microbial in Combination with a Micromotor. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2025, 13, 4018–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.-S.; Chen, S.-Q.; Zhao, X.-M.; Song, L.-J.; Deng, Y.-M.; Xu, K.-W.; Yan, Z.-F.; Wu, J. Enhanced Degradation of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Microplastics by an Engineered Stenotrophomonas Pavanii in the Presence of Biofilm. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 955, 177129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.; Chen, G.; Fan, J.; Tan, W.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; Li, K. Modulating Ion Migration Realizes Both Enhanced and Long-Term-Stable Nanozyme Activity for Efficient Microplastic Degradation. Chem Sci 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Zhao, W.; Ji, S.; Yang, C.; Zhang, J.; Guo, R.; Zhang, B.; Lyu, W.; Feng, J.; Xu, H.; et al. Joule Heat Assisting Electrochemical Degradation of Polyethylene Microplastics Melted on Anode. Applied Catalysis B: Environment and Energy 2024, 357, 124281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Fan, S.; Li, X.; Shi, J.; Wang, M.; Niu, Z.; Chen, G. Trash to Treasure: Electrocatalytic Upcycling of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Microplastic to Value-Added Products by Mn0.1Ni0.9Co2O4-δ RSFs Spinel. J Hazard Mater 2023, 457, 131743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Tao, M.; Ji, H.; Xiang, X.; Fu, Z.; Liao, L.; Liao, P.; Chen, R. Effective Degradation of Polystyrene Microplastics by Ti/La/Co-Sb-SnO2 Anodes: Enhanced Electrocatalytic Stability and Electrode Lifespan. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 922, 171002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Wang, B.; Liu, Z.; Yang, H.; Chen, Z.; Sun, X. La-Doped Ti/Sb-SnO2 Electrode Enhanced Removal of Microplastics by Advanced Electrocatalysis Oxidation Process (AEOP) Strategy. Desalination Water Treat 2024, 320, 100622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Duan, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chang, L. Degradation of Polyvinyl Chloride Microplastics via Electrochemical Oxidation with a CeO2–PbO2 Anode. J Clean Prod 2023, 432, 139668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Wang, S.; Gong, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Dai, Y.; Zheng, Z.; et al. Highly Efficient Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Coupled with Upcycling of Microplastics in Seawater Enabled via Ni3N/W5N4 Janus Nanostructures. Appl Catal B 2022, 307, 121198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuila, S.K.; Dhanda, A.; Samal, B.; Ghangrekar, M.M.; Dubey, B.K.; Kundu, T.K. Defect Engineered 2D Graphitic Carbon Nitride for Photochemical, (Bio)Electrochemical, and Microplastic Remediation Advancements. ACS ES&T Water 2024, 4, 4283–4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhong, H.; Xu, Q.; Dong, M.; Yang, J.; Yang, W.; Feng, Y.; Su, Z.-M. Vacancy-Rich NiFe-LDH/Carbon Paper as a Novel Self-Supporting Electrode for the Electro-Fenton Degradation of Polyvinyl Chloride Microplastics. J Hazard Mater 2025, 485, 136797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda Zoppas, F.; Sacco, N.; Soffietti, J.; Devard, A.; Akhter, F.; Marchesini, F.A. Catalytic Approaches for the Removal of Microplastics from Water: Recent Advances and Future Opportunities. Chemical Engineering Journal Advances 2023, 16, 100529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Chen, Y.; Gao, C.; Wang, C.; Hu, A.; Dong, G.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, S.; Xiong, Y. Sustainable Conversion of Microplastics to Methane with Ultrahigh Selectivity by a Biotic–Abiotic Hybrid Photocatalytic System. Angewandte Chemie 2022, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Zhou, L.; Duan, X.; Sun, H.; Ao, Z.; Wang, S. Degradation of Cosmetic Microplastics via Functionalized Carbon Nanosprings. Matter 2019, 1, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, F.; Liu, Y.; Gao, M.; Yu, X.; Xiao, P.; Wang, M.; Wang, S.; Wang, X. Degradation of Polyvinyl Chloride Microplastics via an Electro-Fenton-like System with a TiO2/Graphite Cathode. J Hazard Mater 2020, 399, 123023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Liu, W.; Jin, Q.; Lin, H. Piezo-Photocatalytic Enhanced Microplastic Degradation on Hetero-Interpenetrated Fe1−xS/FeMoO4/ MoS2 by Producing H2O2 and Self-Fenton Action. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 508, 160935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jang, J.; Hilberath, T.; Hollmann, F.; Park, C.B. Photoelectrocatalytic Biosynthesis Fuelled by Microplastics. Nature Synthesis 2022, 1, 776–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.-Y.; Jiang, J.-C.; Jin, B.; Meng, L.-Y. Hydrogen Evolution Coupled with Microplastic Upcycling in Seawater via Solvent-Free Plasma F-Functionalized CoNi Alloy Catalysts. J Alloys Compd 2024, 1008, 176593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Zhao, W.; Ji, S.; Yang, C.; Zhang, J.; Guo, R.; Zhang, B.; Lyu, W.; Feng, J.; Xu, H.; et al. Joule Heat Assisting Electrochemical Degradation of Polyethylene Microplastics Melted on Anode. Applied Catalysis B: Environment and Energy 2024, 357, 124281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efremenko, E.N.; Lyagin, I. V.; Maslova, O. V.; Senko, O. V.; Stepanov, N.A.; Aslanli, A.G.G. Catalytic Degradation of Microplastics. Russian Chemical Reviews 2023, 92, RCR5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandieh, M.; Griffiths, E.; Waldie, A.; Li, S.; Honek, J.; Rezanezhad, F.; Van Cappellen, P.; Liu, J. Catalytic and Biocatalytic Degradation of Microplastics. Exploration 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Xie, Y.; Wang, J. Microplastic Degradation Methods and Corresponding Degradation Mechanism: Research Status and Future Perspectives. J Hazard Mater 2021, 418, 126377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Mo, A.; Jiang, J.; Liang, Y.; Cao, X.; He, D. Removal of Microplastics in Water: Technology Progress and Green Strategies. Green Analytical Chemistry 2022, 3, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, H.; Meegoda, J.N. Microplastic Pollution Prevention: The Need for Robust Policy Interventions to Close the Loopholes in Current Waste Management Practices. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Redondo-Hasselerharm, P.E.; Nor, N.H.M.; de Ruijter, V.N.; Mintenig, S.M.; Kooi, M. Risk Assessment of Microplastic Particles. Nat Rev Mater 2022, 7, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xayachak, T.; Haque, N.; Lau, D.; Pramanik, B.K. The Missing Link: A Systematic Review of Microplastics and Its Neglected Role in Life-Cycle Assessment. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 954, 176513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed Nor, N.H.; Kooi, M.; Diepens, N.J.; Koelmans, A.A. Lifetime Accumulation of Microplastic in Children and Adults. Environ Sci Technol 2021, 55, 5084–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Current size categories | Size range | Proposed size categories | Size Range | Organism of equivalent size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoplastic | 0.001–1 µm | Femto-size plastics | 0.02–0.2 µm | Virus |

| Microplastic | 1–1000 µm | Pico-size plastics | 0.2–2 µm | Bacteria |

| Nano-size plastics | 2–20 µm | Flagellates | ||

| Micro-size plastics | 20–200 µm | Diatoms | ||

| Mesoplastic | 1–10 mm | Meso-size plastics | 200–2000 µm | Amphipods |

| Macroplastic | > 1 cm | Macro-size plastics | 0.2–20 cm | Jellyfish |

| Mega-size plastics | 20–200 cm | Jellyfish |

| Category | Bulk plastic | Microplastic |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Intentionally manufactured | MPs are either produced at that size (primary microplastics) or result from the fragmentation of larger plastic waste (secondary microplastics) through aging, weathering and fragmentation |

| Size | > 5 mm | < 5 mm, no lower limit yet |

| Shape | Varied shapes can be controlled | Fragments, fibers, films, foams, and microbeads. The shapes can be broadly categorized as regular (spherical, cylindrical, etc.) or irregular |

| Polymer type | Single type or with controlled polymer types | MPs can be composed of a wide variety of polymer types as a mixture. The most common include polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC). Other polymers like polyamide (PA), polyurethane (PU), polycarbonate (PC), and polyester (PES) are also found in microplastics. The specific polymers found in microplastics can vary depending on the source and location. |

| Surface | Low surface to volume ratio | Higher surface area to volume ratio, higher surface energy. Higher surface charge due to ions absrobtion. May include cracks, pits, and other surface features due to UV radiation, mechanical abrasion, and chemical degradation. |

| Crystallinity | Standard and uniform | Weathering and aging processes can significantly alter the crystallinity of microplastics |

| Surface chemistry | Relative clean | Absorbed substances from the environment, including pollutants (organic, inorganic), nutrients, and microorganisms, leading to changes in their surface properties and behavior. Presence of specific functional groups on the surface (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl) |

| Method | Advantages | Limitations | Particle Size Best Suited For | Typical Pretreatment Steps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Microscopy | Rapid visualization; low cost; simple operation | Limited resolution; cannot identify polymer type | >100 µm | Filtration/sieving; density separation |

| SEM/EDS | Very high resolution; reveals surface structure and aggregation | Cannot identify polymer type; expensive instrumentation; | <100 µm | Filtration/digestion → drying → conductive coating (Au/C) or wet-mode imaging |

| µ-FTIR / FPA-FTIR | Enables polymer identification; FPA allows batch imaging/statistics; high throughput | Low sensitivity for nano plastics; easily disturbed by environmental fouling | >20 µm | Filtration onto IR-transparent substrates; H₂O₂ or enzymatic digestion |

| Micro-Raman | High spatial resolution (sub-micron detection); less affected by water | Strong fluorescence background; long acquisition time; high instrument cost | <20 µm | Clean low-fluorescence filters; filtration |

| ¹H NMR | Rich quantitative information: polymer composition, degradation pathways, additives | Requires large sample amounts; expensive; not suitable for routine monitoring | <300 µm | Bulk sample concentration; solvent extraction |

| Py-GC/MS (incl. TED-GC/MS) | Accurate qualitative/quantitative identification of polymers in mixed or weathered samples; improved throughput | Destructive method; no morphological information | No limitation on particle size | Drying; homogenization; removal of salts/water |

| TGA | Characterizes thermal degradation behavior; combined with FTIR/MS gives composition and quantification | Overlapping thermal peaks; interference from organics or minerals | No limitation on particle size | Drying; homogenization; removal of inorganic/organic matter |

| Catalyst | MP type | Size | Condition | Products | Quantification method |

Efficiency | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-doped BiO2−x/BiOI heterojunction | PET | NA | Xenon lamp (200–1000 nm, 500W) in water | NA | Degradation efficiency by FT-IR characterization | NA | [53] |

| g-C3N4/TiO2/WCT-AC | PE | 0.15 mm | 500W xenon lamp irradiation for 200 h in water at 25 °C with 600 rpm | NA | Weight loss |

67.58 % revmoal in 200h | [58] |

| C3N4/WO3 | PET | 0.45 μm | 300W xenon lamp at 25 °C in water | H2: 14.21 mM and formate, methanol, acetic acid, and ethanol | Weight loss was measured |

NA | [59] |

| MXene/ZnxCd1-xS | PET solution | NA | 300W Xenon lamp, reaction in 50 ml PET solution | 14.17 mmol·g−1·h−1 H2 generation rate. Glycolate, acetate, ethanol, etc. | HNMR spectroscopy | NA | [60] |

| Ag/TiO2 nano-composites | PE | 100-250 μm | UV lamp irradiation with 2000 rpm | NA | Weight loss was measured |

100% in 90 min for 125-200 μm | [61] |

| Pt/ZnO nanorods | LDPE | 50 μm | 50W dichroic halogen lamp, 175h | NA | Carbonyl index (CI) and vinyl index (VI) calculation through FTIR | 13% and 15% increase for CI and VI with Pt compared to ZnO only | [62] |

| Core-shell BiO2−x/CuBi2O4 heterojunction | PS and PE | 4 μm | Full spectrum light sources (300W, Xenon lamp |

Benzoic acid, ethylbenzene and styrene | FTIR was used to quantify the carbonyl content | Severe damage to the surface PS after 15d of full spectrum light irradiation compared to BiO2−x and CuBi2O4 alone | [63] |

| Nb doped SnO2 quantum dot | PE | 350 μm | Visible light from an 8W LED (400–800 nm) and a 200W Xe lamp (380–1100 nm) | CO2 and H2O with HC intermediates | Weight loss |

28.9% weight loss after 7 h | [64] |

| TiO2-modified boron-doped diamond (BDD/TiO2) | HDPE | 250 μm | 6.89 mA cm−2 current density and UV light in aqueous media | Organic compounds such as aldehydes and ketones | FTIR was used to quantify the carbonyl content | 89.91±0.08% of HDPE MPs in a 10-h | [65] |

| BOC-S, BOC-N and BiOCl photocatalysts | PET | 37 μm | 180 °C for 12 h. 300W xenon lamp | CO2 | Weight loss | 44.33% degradation of PET MPs within 5 h. | [66] |

| TiOx/ZnO tetrapod | PE and PES microfibers | 100 μm | 365 nm UV light at room temperature | NA | Weight loss | Complete mass loss of PE and PES under UV illumination for 480 h and 624 h | [67] |

| BiOBr-OH semiconductor-organic framework | PS | 5 μm | 250W Xe lamp for 72 h | Monomeric molecules and multiple molecular complexes | Weight loss, filter with 1 μm filter paper | 7.31% mass loss after 72 h | [68] |

| S vacancy-rich CdS | PET | ~500 μm | Simulated solar irradiation 6h | H2, Terephthalic acid, Ethylene glycol, Formic acid | Mass Loss and GC | 23-fold increase in H2 production compared to commercial CdS | [69] |

| BiOI-MOF composite | PE | 230±90 μm | 500W Xenon lamp for 6 h | Alcohols, lipids, carboxylic acids, long-chain alkane | ATR-FTIR for cabornyl | CI decreased to 0.127 in 6 h | [73] |

| TiO2 anchored chitin sponge | PS | 1 μm | 60W lamp (λ = 365 nm), UV light | 2-Butanone, 3,3-dimethyl cyclohexanone | UV-vis dye assissted quantification | 58.4% in 6h | [74] |

| Catalyst | Plastic type | Size | Mechanism | Condition | Products | Quantification method | Efficiency | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuttlefish Bone-Supported CoFe2O4 nanoparticles | PS | 70 nm | Fenton-like | 100 rpm and 25 °C, APS dosage (0.25–1.25 g/L) | NA | TOC analyzer | 88.27 % removal in 30 min | [79] |

| CuMg co-doped carbonized wood sponge catalysts CuMgCWS | PP | NA | Electro-Fenton | Hydrothermal at 160 °C for 14 h | Hydrocarbons and ketones | Weight loss, GCMS | 80 wt% selectivity to hydrocarbons and ketones | [80] |

| Cobalt/carbon quantum dots core-shell nanoparticles | PP | < 25μm | Fenton-like | 4.0 ml of hydrogen peroxide 35% v/v |

NA | Weight loss | 9.6% degradation in 24 h | [81] |

| Copper-cobalt carbon aerogel (CuCo-CA) | PS | ~119 nm | Fenton | Current: 20 mA, initial pH: 7.0, electrolyte 0.05 M | Acetophenone, benzoic acid, esters, aldehydes, and alcohols | FTIR, UV-Vis, and direct infusion MS | 94.8 % removal efficiency in 6h | [82] |

| Ferroelectric Bi12(Bi0.5Fe0.5)O19.5 | PET | 500–600 μm | Piezo-Fenton | Ultrasound treatment (40 kHz, 120 W), RT | NA | Weight loss, HPLC, LC-MS | 28.9% removal rate in 72 h | [83] |

| α-Fe2O3 nanoflower on TiO2 with a hierarchical structure | PS | 310 nm | Photo-Fenton | A Hg lamp (365 nm, 0.5 W cm−2) , 75 °C | Carboxylic acids or carboxylates, CO2 | 1H NMR, GC | Nearly 100% degradation in 4 h at 75 °C | [84] |

| Zeolitic imidazolate framework@hydrogen titanate nanotubes (HTNT@ZIF-67) | Toothpaste MPs | ~300 μm | Fenton | 1 mL, 30% H2O2 addition | NA | HPLC-MS and weight loss | 97% removal efficiency in 3h | [86] |

| Catalyst | MP type | Size | Mechanism | Condition | Products | Quantification method | Efficiency | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hopcalite-(CuMnOx) | PS | 200 µm | Plasma assisted thermal oxidation | Plasma (20.6 kV, 8.6 kHz), 79% N2 and 21% O2 | CO2 | Weight loss and Micro GC | 98.7 % PS-MPs conversion to CO2 in 60min | [18] |

| Mg/Zn -MBC | PS | 1.0 μm | Pyrolysis | 500 ◦C for 10 m | Aromatics in the range of C6-C9, |

MPs weight concentration |

94.81% MBC only 98.75% Mg-MBC 99.46% Zn-MBC |

[89] |

| Anatase-Rutile Ni-Pd/TNPs | Mixed MPs made from waste plastics blending | <= 5 mm2 | Reforming and cracking | 500–700 °C, N2, phenol dissolved MPs as feed | H2 and liquid fuels | GC-MS, FTIR, GC-FID, and GC-TCD | H2 yield (93%) and phenol conversion (77%) at 700 °C | [90] |

| NiCl2 | HDPE blended to small size | NA | Pyrolysis | 800 ℃, 3 h, N2 | Functional carbon | TGA-DSC | 33.4% carbon yield with 15:1 catalyst to HDPE ratio | [93] |

| Co-N/C@CeO2 composite |

PET | ~4 µm | Thermal-Fenton | PMS (5 mM) + Co-N/C@CeO₂ (0.5 g/L) + H₂O₂ (1 mL), T = 55–65 °C, | HC intermediates, CO₂ + H₂O | Mass loss; GC–MS; UPLC-MS | 92.3% PET MPs degradation at 55 °C with PMS + H₂O₂ (vs. 52.3% without H₂O₂) | [95] |

| Fe³⁺, Al³⁺, Cu²⁺, Zn²⁺ | PE (spheres & fragments), PA (fibers), PP (fragments) | 150–500 µm | Hydrothermal degradation | 180–300 °C, 30 min, (10–85 bar) | Olefins, paraffins, ethanol, glycols; nanoplastics | Weight loss SCOD, TOC, GC–MS, Py–GC–MS, FTIR | PA: >95% in Fe³⁺, 92% in Al³⁺ at 300 °C; PE: ~17–25%; PP: ~13% in Fe³⁺ at 300 °C; | [96] |

| Zeolite catalysts | PE, PP, PS, PET, PVC | Pellets (~3 mm) or powders (<1 mm) | Pyrolysis | 300–600 °C, often ~500 °C, 0.1–0.8 MPa; 15–120 min; | Olefins, aromatics, gasoline/diesel paraffins, waxes, H₂, CH₄, C₂–C₄ | GC–MS, TGA, FTIR; | Liquid oil yield: 80–90%; | [97] |

| ZnO nanoparticles (<50 nm) | PP | Macro: 100 mm²; Micro: 25 mm² | Thermo-photocatalytic | UV-C (254 nm, 11 W), 1–3 g/L ZnO, 35–50 °C, 6 h, air bubbling (1.6 L/min) | Nano plastic | Weight loss measurement | 7.89% weight loss in 6 h | [98] |

| Fe-MBC | PS | 100 nm | Pyrolysis | 550 °C, 10 min, N₂ atmosphere | Styrene (74.6%), benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, α-methylstyrene | UV–Vis (224 nm) for PS conc. GC–MS | Removal efficiency ≈99% (initial) | [99] |

| Catalyst | Plastic type | Size | Condition | Products | Quantification method | Efficiency | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candida rugosa lipase (CrL) immobilization in metal-organic frameworks (CrL_MOFs) | Bis-(hydroxyethyl) terephthalate (BHET) as model compound | NA | Water, 25 °C, 1 bar | H2BDC | High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) | 37 %, 24 h,3 mg of degraded BHET per g of enzyme | [104] |

| Hydrophilic bare Fe3O4 nanoaggregates | HDPE, PP, PVC, PS, and PET | 20-800 μm | 130-260 ℃, autoclave | NA | UV-vis and weight measuring | 100 % degradation close to their melting temperature | [105] |

| Shewanella putrefaciens 200 | PS | 1.20 -1.30 mm | 25 °C and PH: 7.0 in water solution | Benzene ring derivatives | Weight loss was measured by an analytical balance | Weight loss of 6.1 ± 0.6% in 14 days | [106] |

| Manganese oxide free radicals modified SDE-PsLAC, E. coli BL21 | PE | 500–1500 μm | 37 °C or 15 °C for 192h | Aromatics, aliphatics, alcohols, and esters | Weight loss | 91.2 % at 37 °C and 52.4 % at 15 °C within 192 h | [107] |

| Iron-enhanced microbiota | PE | 3–5 mm² piece from commerical plastic bag | 30 to 60 days of cultivation at 37 °C | Heneicosane, octadecane, pentadecane, and 4,6-dimethyl dodecane | Weight loss | 12.38% weight loss in 60 days compared to 10.44% for non iron added samples | [108] |

| MnO2/g-C3N4/fly ash (MCNF) | PS, PE | 5 μm | RT with H2O2 addition | NA | Weight loss | PS degradation 60% in 24 days; 66% PE degradation in 50 days | [110] |

| Engineered S. pavanii with DuraPETase | PET | 500 μm | 30 °C and 150 rpm | TPA, MHET, BHET | HPLC | 38.04μM products generation after 30-day incubation at 30 °C | [111] |

| Mn-doped iron phosphate(LFMP) | Polyamide 6, HDPE, and pp | 0.5 to 4.5 mm | 25 °C or 180 °C for 8h in autoclave | CO2, H2O2, and inorganic small molecules | Weight loss | 91.5% at 180 °C for 8h. 3 times higher than that no doped LFP | [112] |

| Catalyst | Plastic type | Size | Condition | Products | Quantification method | Efficiency | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn₀.₁Ni₀.₉Co₂O₄-δ rod-shaped fiber (RSF) spinel catalyst | PET | <500 μm | 5 mV s−1, 1 M KOH (pH = 14), 0.17 M ethylene glycol | H2 and formate | NMR spectrometer | EG to formate with >95% Faradaic efficiency at 1.42 V vs RHE | [114] |

| Ti/La/Co-Sb-SnO2 anode | PS | 150 μm | 0.5mol/L H2SO4 LSV:scanning rate: 1.0 mV s−1, V: 0 to 2.5 V. | Alcohols, monocarboxylic acids, dicarboxylic acids, esters, ethers, and aldehydes | Weighing method and PY-GCMS | 28% removal in 3 h | [115] |

| Ni3N/W5N4 janus | PET flakes | <500 μm | Scan rate of 5 mV s-1 | H2 and HCOOH | NMR spectrometer | ~85% Faradaic efficiency | [118] |

| Vacancy-rich NiFe-LDH/carbon paper | PVC | 74–147 μm | 10 to 100 mV s⁻¹ | H₂O₂ | Ion Chromatography (IC) and GC–MS | ~76% selectivity for H₂O₂ | [120] |

| CeO2-modified PbO2 anode | PVC | NA | T:20–100 °C, 10–60 mA/cm2, pH (3–11), PVC-MPs (50–150 mg/L), and Na2SO4 10–90 mM | H2O and CO2 | Weight loss and HPLC-MS | 38.67% weight loss in 6 h. 16.67% increase compared to pristine PbO2 anode | [117] |

| Catalyst | Plastic type | Mechanism | Size | Condition | Products | Quantification method | Efficiency | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeSA-hCN (single-atom Fe on porous carbon nitride) | UHMWPE | Tandem MP degradation + H₂ evolution | < 180 μm | Simulated solar irradiation in aqueous suspension, pH 7 | 64% carboxylic acid selec; H₂: 42 µmol/h | Mass loss, HPLC | Near 100% PE degradation | [21] |

| TiO₂/graphite (TiO₂/C) cathode | PVC | Electro-Fenton | 74–147 µm | −0.7 V vs Ag/AgCl using Na₂SO₄ as supporting electrolyte | CO₂, H₂O, and Cl⁻ | Dechlorination efficiency through ion chromatography | ~75% dechlorination efficiency in 6h | [117] |

| Methanosarcina barkeri (M. b) and carbon dot-functionalized polymeric carbon nitrides | Poly(lactic acid), PE, PS, and PUR | Photo-biological | ≤0.04 cm2 | 395±5 nm ultraviolet,35±2 °C | 100 % CH4 | NA | CH4 yield 7.24±0.40 mmol g−1 | [122] |

| Magnetic N-doped nanocarbon springs | MPs from cosmetic pastes | Integrated carbocatalytic oxidation and hydrothermal (HT) | >=0.45 μm | Peroxymonosulfate (PMS) added in a autoclave with water | CO2 and H2O | Filtration through a 0.45-μm membrane. Mass loss measurement and HPLC | 44% of MPs decompositions in 8h | [123] |

| Fe1−xS/FeMoO4/ MoS2 | PS | Piezo-photo-Fenton | 0.55-12.5 μm | Ultrasonic cleaner (at 120 W, 40 kHz) equipped with LED irradiation (24 W) at RT | Benzoic acid and phenylacetic acid | Centrifugation for calculating the weight loss | 58.46 % of PS-MPs in 30h | [125] |

| Zr-doped hematite (α-Fe₂O₃) photoanode | PET | Photo-biological | <2 mm | A mixed condition | Formate and acetate | Quantitative ¹H NMR and HPLC | High faradaic efficiency (>90%) | [126] |

| F-functionalized CoNi-alloy catalyst | PET | Binfunctional | NA | 50 to 300 mV s-1 | H2 and formate | ¹H NMR | 90.7% faradaic efficiency at 1.48 V | [127] |

| Ti/Sb-SnO2 and carbon felt | PE, PP, PS, PVC, PLA, and PET | Thermal-electro | ~400 μm | 20 mA·cm−2 current density, Na2SO4 electrolyte | Oxygen-containing species, H2O and CO2 | Weight loss and GC/MS | 99 % degradation of PE MPs in 6 h | [128] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).