Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

12 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

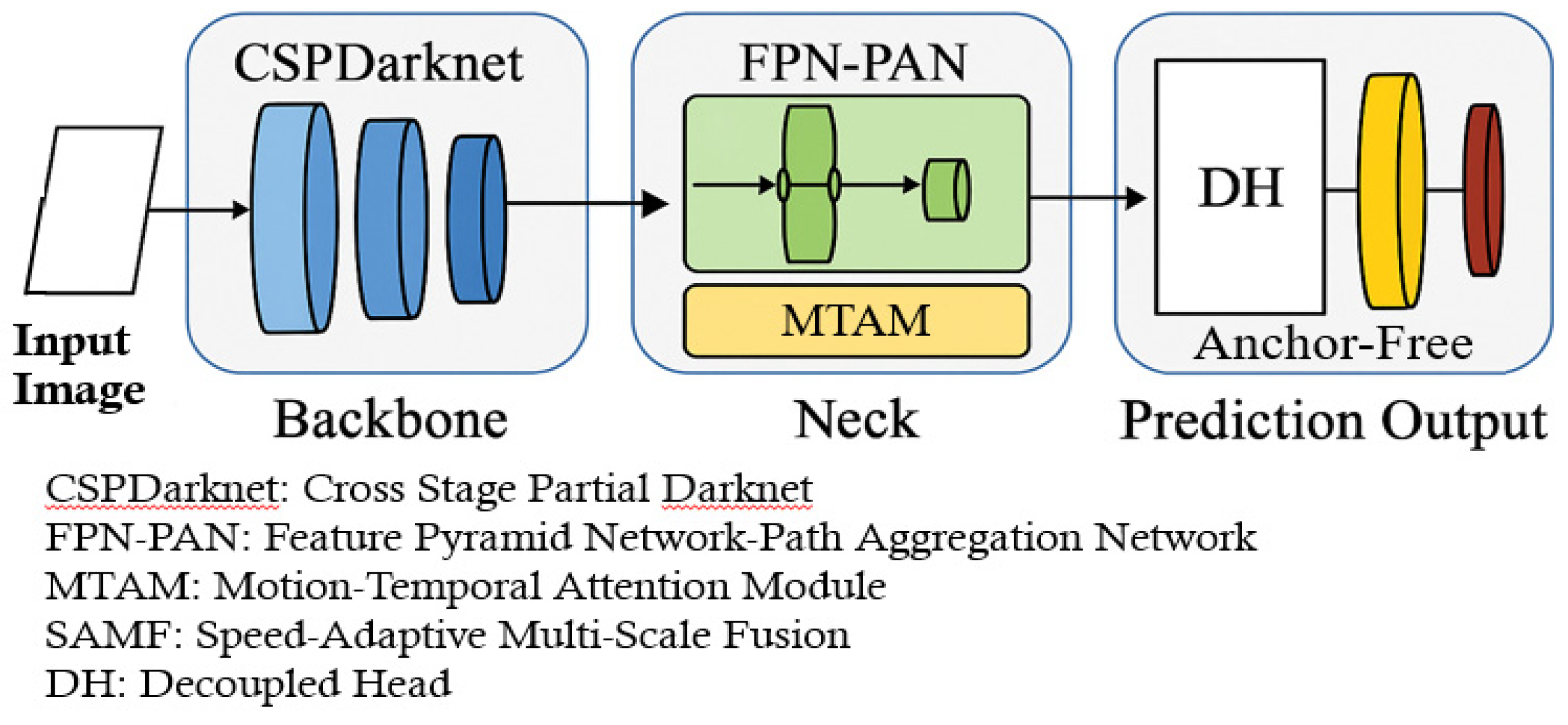

2. Neural Network Architecture

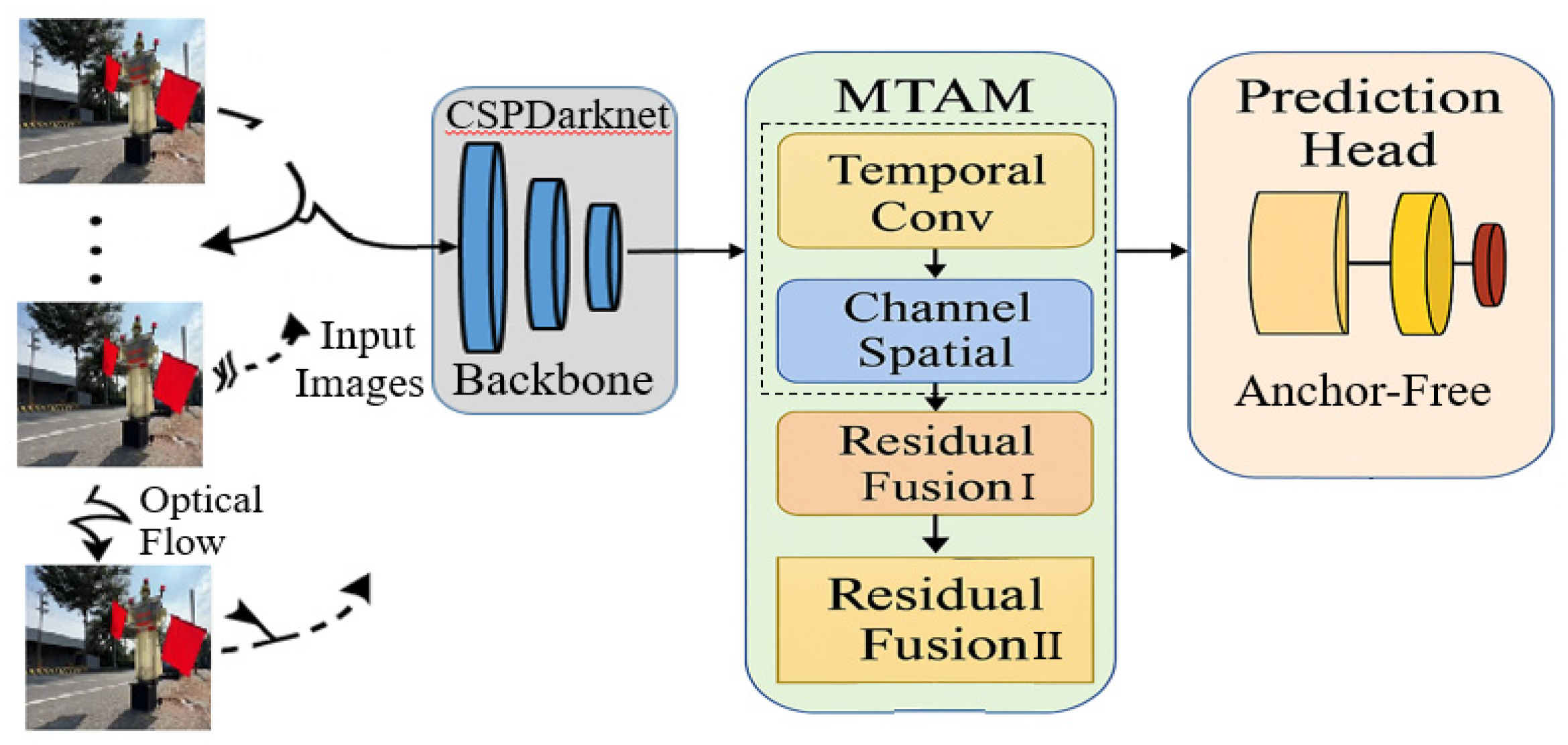

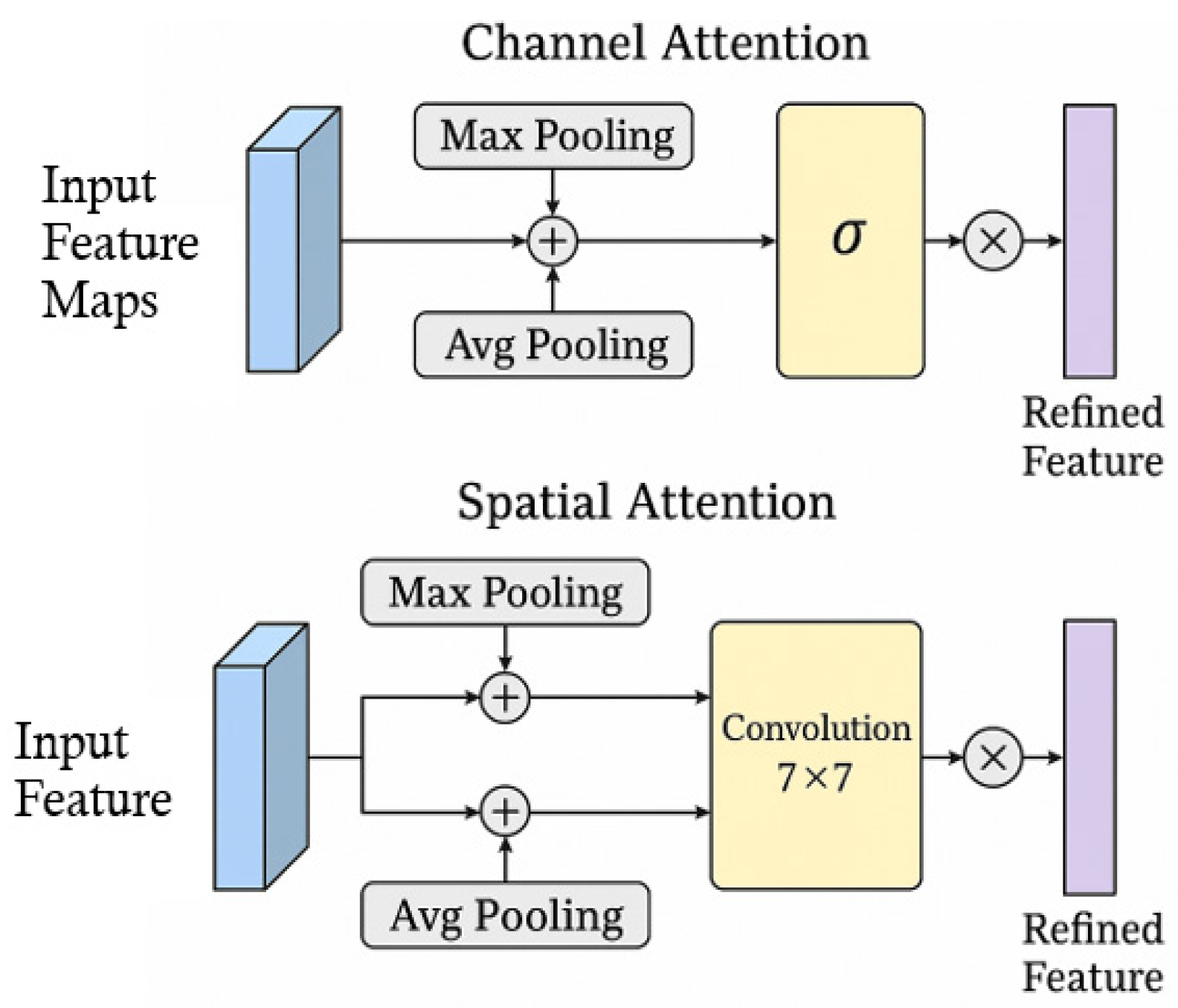

2.1. Motion-Temporal Attention Module (MTAM)

2.2. Loss Functions

2.3. Improved YOLOv8 Loss Function with MTAM module

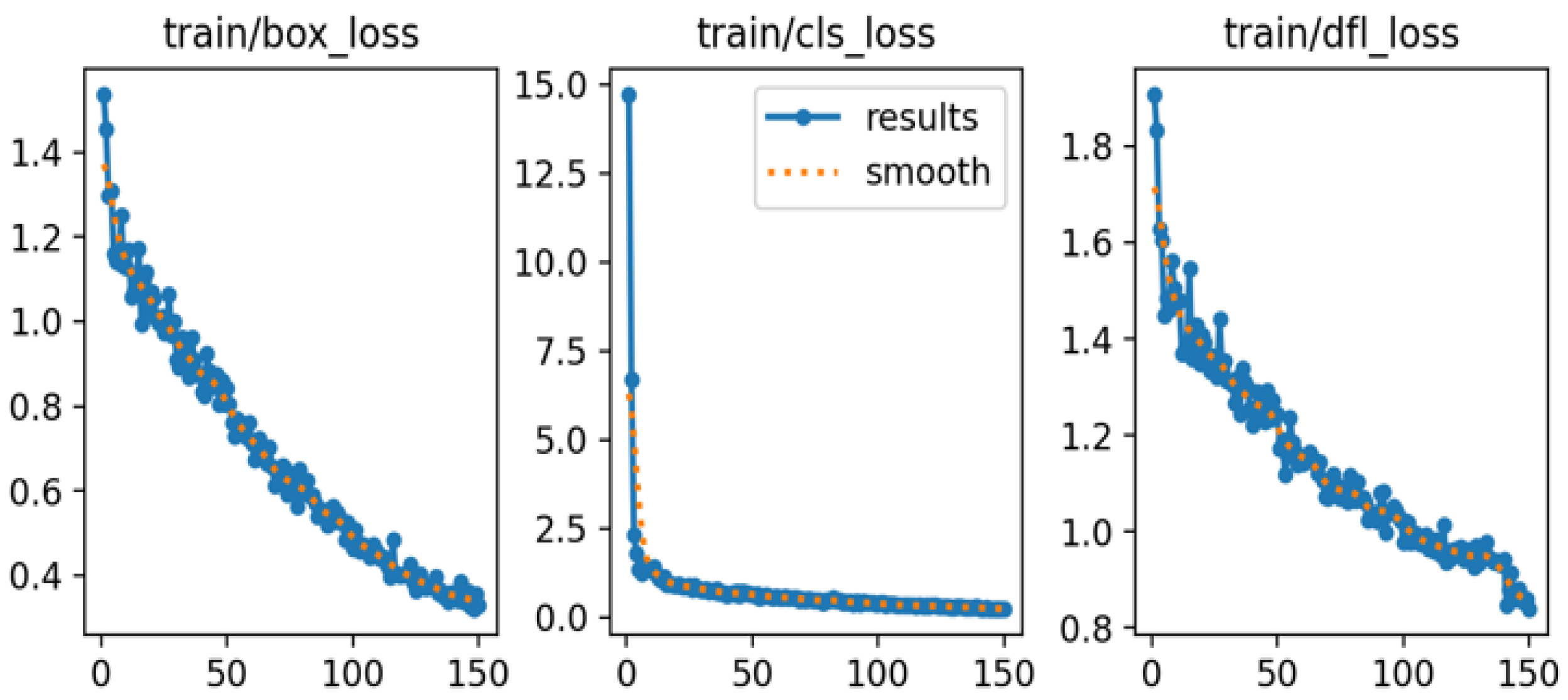

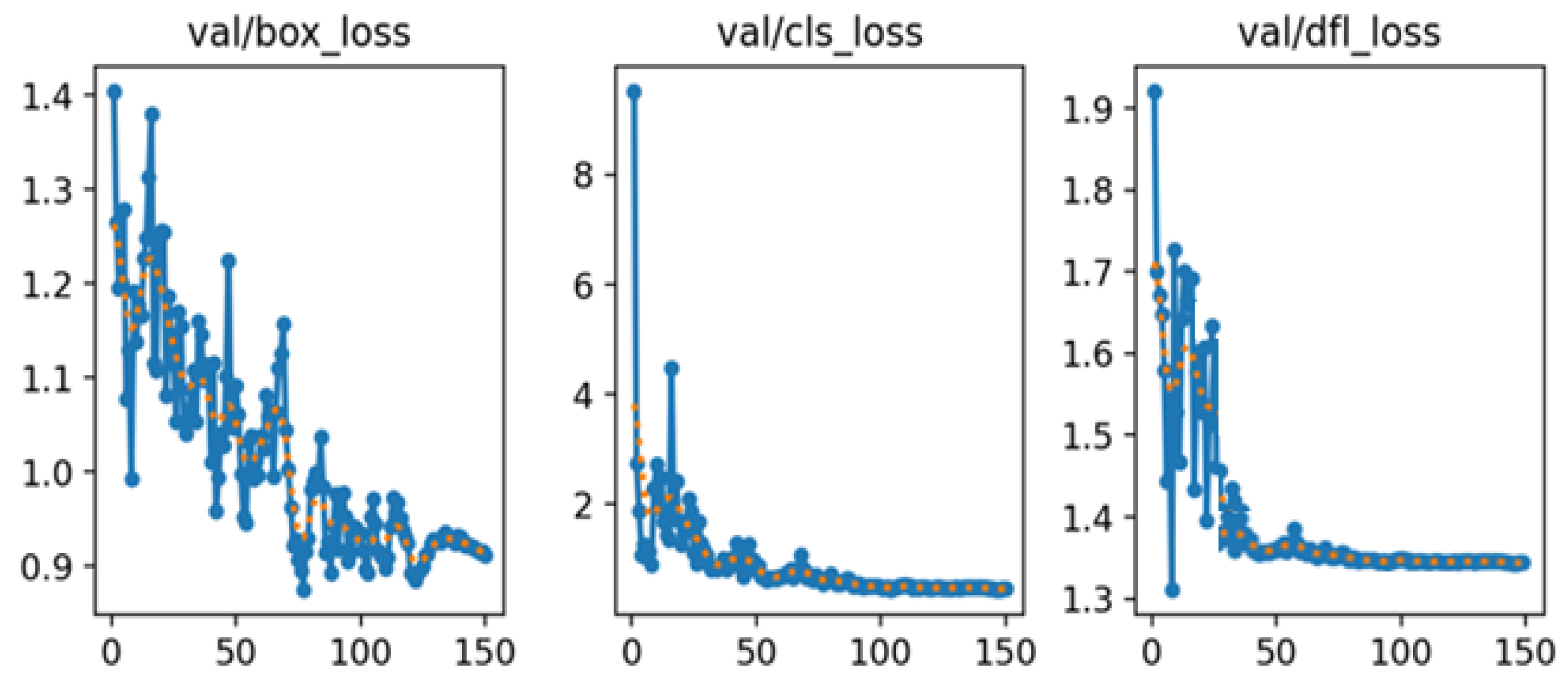

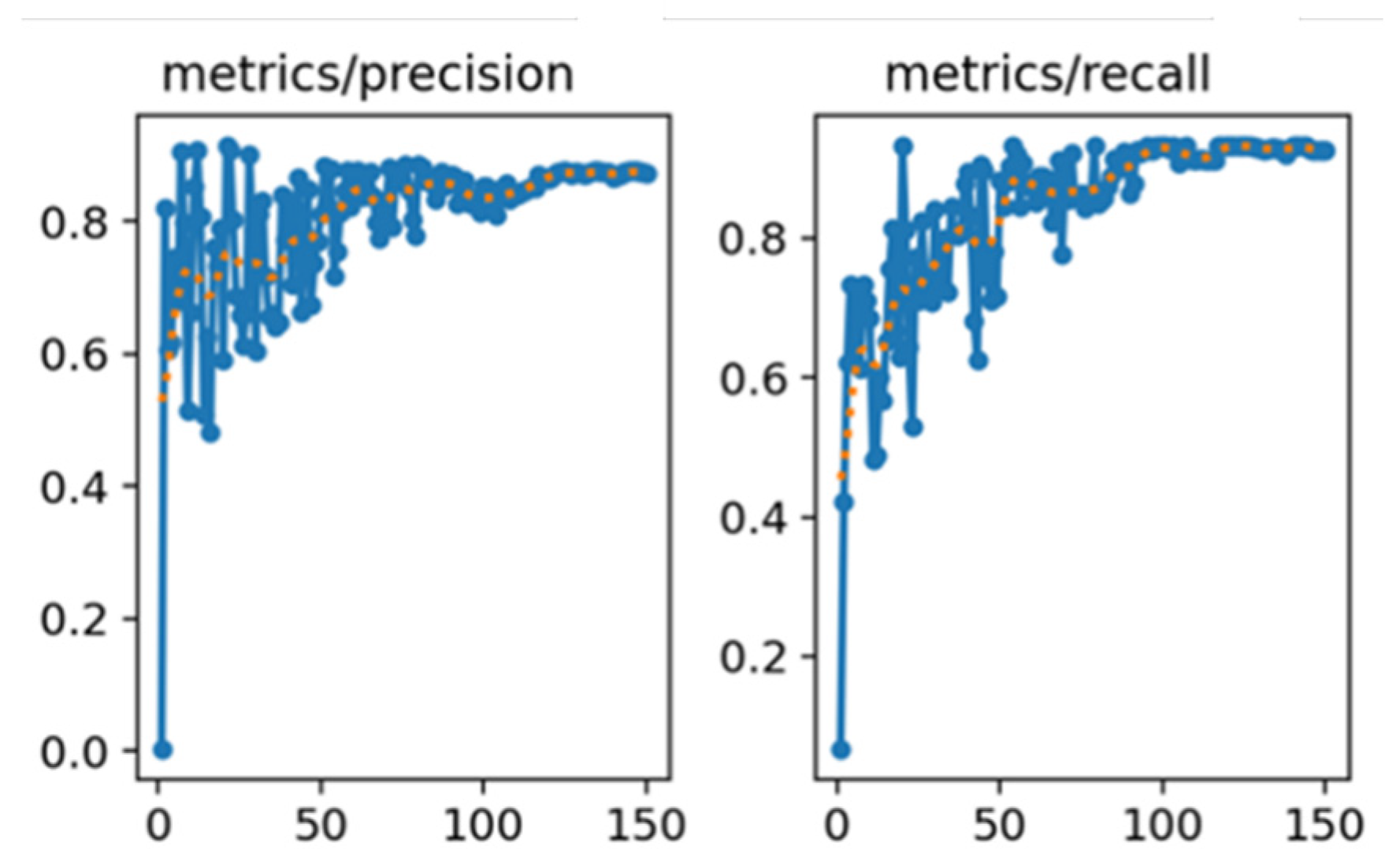

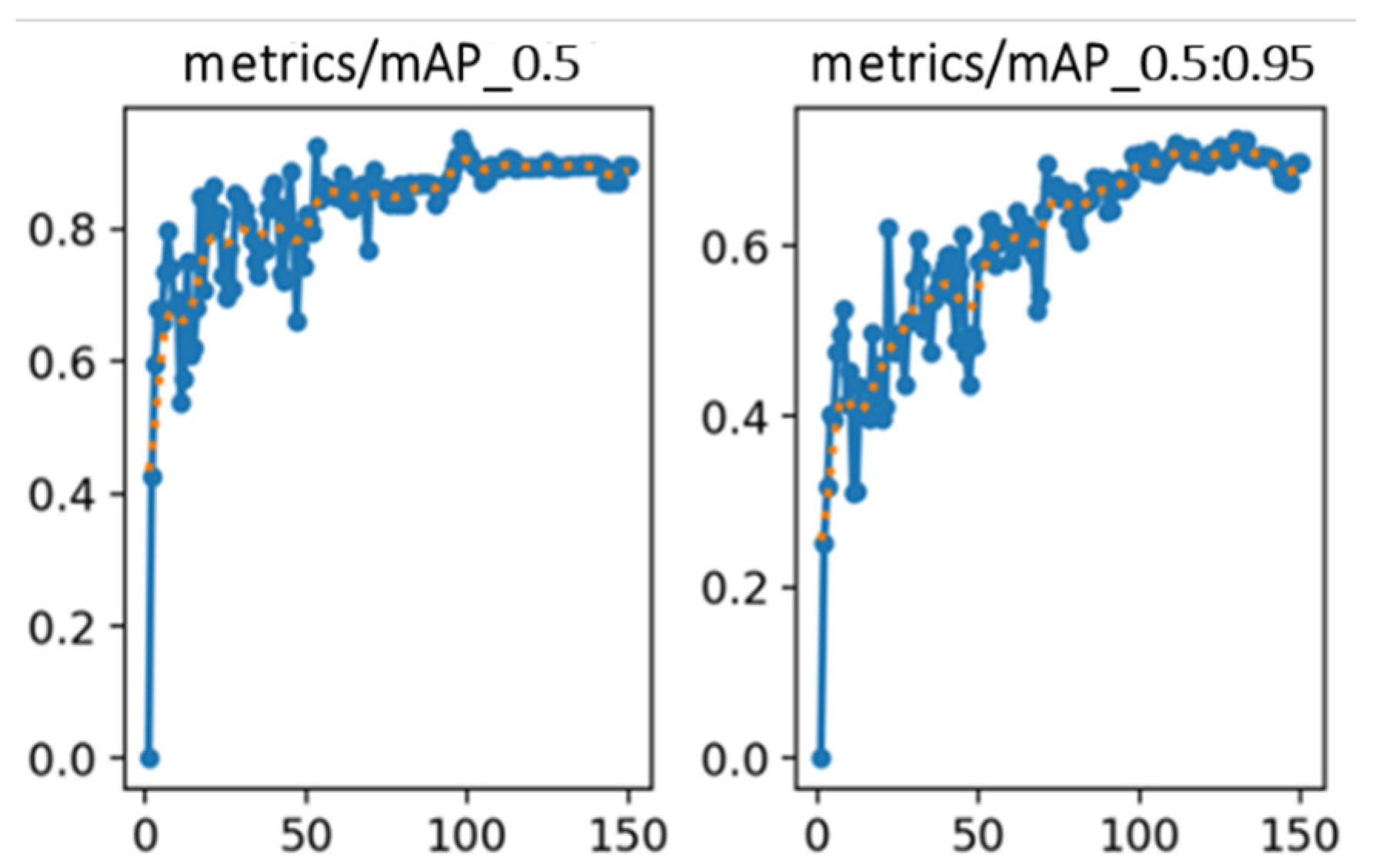

3. Experimental Results

3.1. Experimental Environment Setup

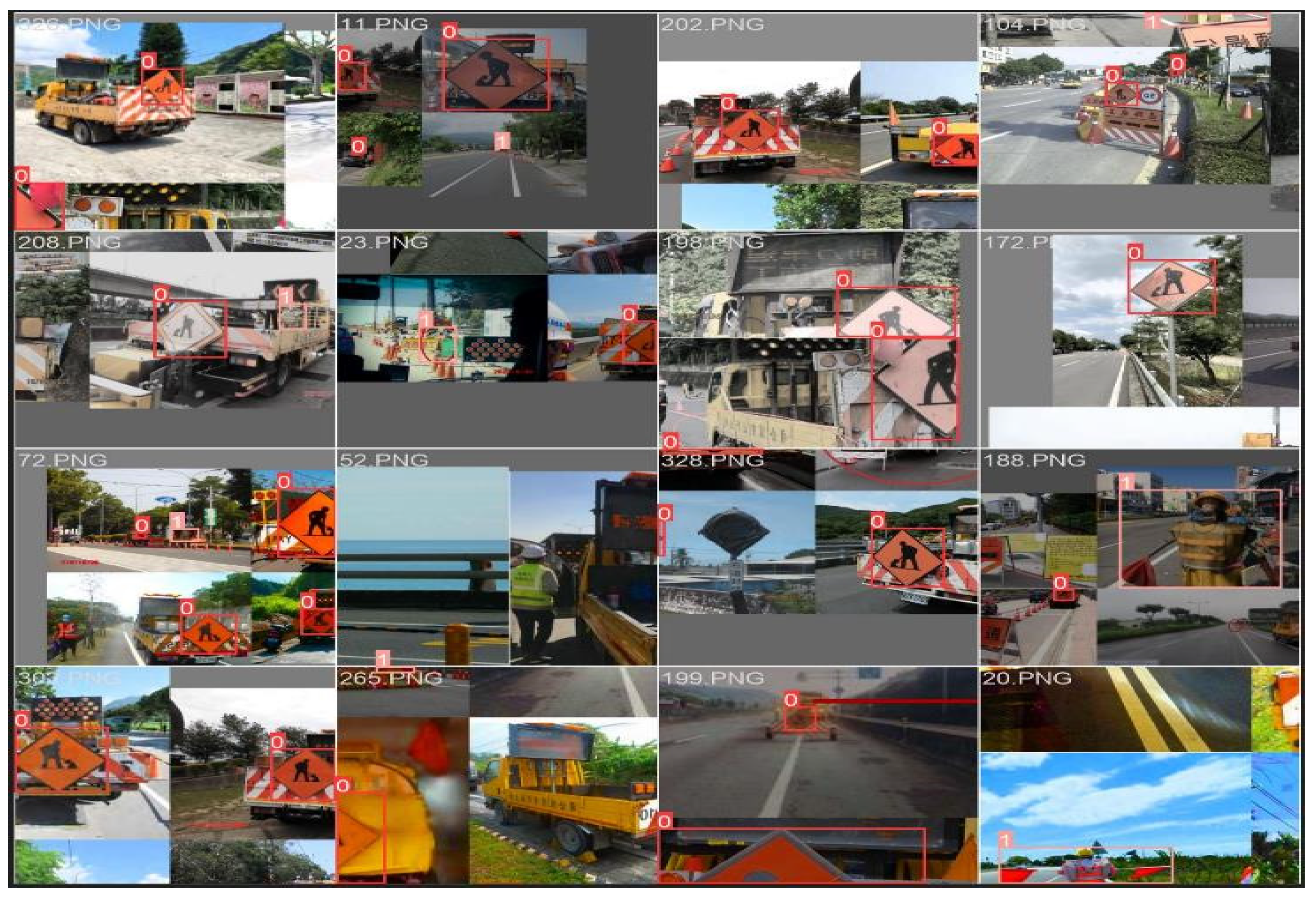

3.2. Image Collection and Augmentation

3.3. Image Data Classification and Labeling

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Q. A survey on AI-driven autonomous driving: trends, challenges, and future directions. IEEE Trans. on Intell. Trans. Syst. 2024, 25, 1875–1891. [Google Scholar]

- Sakure, A.; Bachhav, K.; Bitne, C.; Chopade, V.; Dhavade, V.; Sangule, U. Generative AI solution for lane departure, pedestrian detection and paving of autonomous vehicle. 4th Intl. Conf. on Comput. Auto. and Knowledge Manag. 2023; 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wu, F.; Yang, R. Recent advances in perception and decision-making for autonomous vehicles: from deep learning to real-world deployment. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2023, 38, 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.; Huynh, D.; Tran, Q. Lightweight SSD for real-time object detection on embedded automotive systems. Sensors 2023, 23, 6329. [Google Scholar]

- Khadidos, A.O.; Yafoz, A. Leveraging RetinaNet-based object detection model for assisting visually impaired individuals with metaheuristic optimization algorithm. Sci. Reports (Nature) 2025, 15, 15979–15998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Zhang, T.; Khan, M. (2023). YOLOv8 for real-time road object detection in autonomous driving systems. IEEE Access, 2023, 11, 121230–121242. [Google Scholar]

- Ayachi, R.; Afif, M.; Said, Y. Traffic sign recognition based on scaled convolutional neural network for advanced driver assistance system. 4th Intl. Conf. Image Proc.; Appl. and Syst. (IPAS), 2022; 149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, Q. A lightweight SSD-based object detection model for real-time embed applications. J. of Real-Time Image Proc. 2023, 20, 945–960. [Google Scholar]

- Carranza-García, M.; Torres-Mateo, J.; Lara-Benítez, P.; García-Gutiérrez, J. On the performance of one-stage and two-stage object detectors in autonomous vehicles using camera data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Raza, A. YOLOv8: redefining anchor-free real-time object detection. IEEE Access, 2024, 12, 65432–65445. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Luo, X. Advanced training techniques in YOLOv8: mosaic, mixup, and beyond. IEEE Access, 2023, 11, 117842–117855. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, D.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y. Domain adaptive object detection for real-time autonomous driving applications. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst.; 2024, 25, 2981–2993. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, J.-W.; Chung, K. Swin transformer-based object detection model using explainable meta-learning mining. Applied Sci. 2023, 3213–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.; Chen, M.; Lee, T. Regulatory requirements for construction safety on Taiwanese expressways and their integration with smart vehicle systems. J. Transport. Saf. & Security, 2024, 16, 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Wang, J.; Hsu, C. YOLOv8-based real-time detection of highway work zone hazards for autonomous vehicles. IEEE Trans. on Intell. Transport. Syst. 2024, 25, 4021–4033. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, S. Advanced YOLOv8 architecture with CIoU/EIoU loss for robust object detection. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 125321–125335. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-C.; Lu, Y.-S.; Lin, W.-P. An modified YOLOv5 Algorithm to improved image identification for autonomous driving. In Congress in Comp. Sci.; Comp. Eng. And appl. Comput.; 2023; pp. 2722–2724. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Y. Survey of state-of-art autonomous driving technologies with deep learning. IEEE International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability and Security Companion 2023, 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, J.; Wang, J. Automatic driving scene target detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv5 network. IEEE Intl. Conf. on Comput. Network, Elect. and Auto. 2022; 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- Tampuu, A.; Aidla, R.; Gent, J.A.V.; Matiisen, T. LiDAR as camera for end-to-end driving. Sensors 2023, 23, 2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olimov, B.; Kim, J.; Paul, A.; Subramanian, B. An efficient deep convolutional neural net-work for semantic segmentation. 8th Intl. Conf. on Orange Technol. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Lin, P.; Ma, S.; Xu, T. An improved Yolov5s algorithm for emotion detection. 5th Intl. Conf. on Patt. Recog. and Artifi. Intell. 2022, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Sophia, S.; Joeffred, G.J. Human behavior and abnormality detection using YOLO and conv2D net. Intl. Conf. on Inventive Comput. Technol. 2024, 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ragab, M.G.; Abdulkadir, S.J.; Muneer, a.; Alqushaibi, A.; Sumiea, E.H.; Qureshi, R. ; A comprehensive systematic review of YOLO for medical object detection (2018 to 2023). IEEE Access 2024, 12, 57815–57836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, E.; Chong, J.J.; Choong, Z.J.; Lau, M. A Comparative analysis of cross-validation techniques for a smart and lean pick-and-place solution with deep learning. Electronics 2023, 12, 2371–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Specification |

|---|---|

| CPU/Memory | 6-Core AMD Ryzen 5 7500F 64 bit Processor 3.7 GHz/32GB RAM |

| GPU/Memory | GPU NVDIA GeForce RTX 5080/32 GB Video RAM |

| Deep learning framework | Pytorch 2.1.2 |

| CUDA toolkit | 11.8 |

| Python | 3.13.2 |

| Operating system | Microsoft Windows 11 Home |

| Item | Specification |

|---|---|

| CPU | Quad-core ARM A57 @ 1.43 GHz |

| GPU | GPU 128-core Maxwell |

| Memory | 8 GB 64-bit LPDDR4 25.6 GB/s |

| Ubuntu | 22.04 |

| Connectivity | Gigabit Ethernet, M.2 Key E |

| Interface | USB 4x USB 3.0, USB 2.0 Micro-B |

| Operating system | Jetson Linux 36.4.4 |

| No. | Image data augmentations | Parameter adjustment range |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Contrast | Color ranges from 1-21 |

| 2 | Mixing | Mix images with one another |

| 3 | Brightness | Between -50% and +50% |

| 4 | Grayscale | Colorful to Grayscale |

| 5 | Saturation | Colorfulness: 0.5 to 1.5X |

| 6 | Blur | Up to 4.0px |

| 7 | Hue | Between -55° and +55° |

| 8 | Noise | Add noise up to 10% of pixels |

| Class | Precision rate | Recall rate | mAP (IoU[0.5]) | mAP( IoU [0.5: 0.95]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| all | 91.12 ± 0.70% | 89.30 ± 0.69% | 90.09 ± 0.51% | 71.13 ± 0.82% |

| construction | 97.91 ± 0.30% | 95.10 ± 0.37% | 94.85 ± 0.25% | 76.30 ± 0.60% |

| warning sign person |

90.85± 0.60% 84.60 ± 1.20% |

88.87± 0.36% 83.96 ± 1.35% |

89.63± 0.30% 85.80 ± 0.98% |

71.85± 0.72% 65.24 ± 1.15% |

| Methods | Precision rate | Recall Rate | mAP (IoU[0.5]) | mAP( IoU [0.5: 0.95]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GIoU | 91.12% | 89.30% | 90.09% | 71.13% |

| CIoU | 91.80% | 88.20% | 90.77% | 70.20% |

| EIoU | 88.10% | 91.40% | 83.80% | 70.10% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).