Submitted:

11 September 2025

Posted:

12 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

-

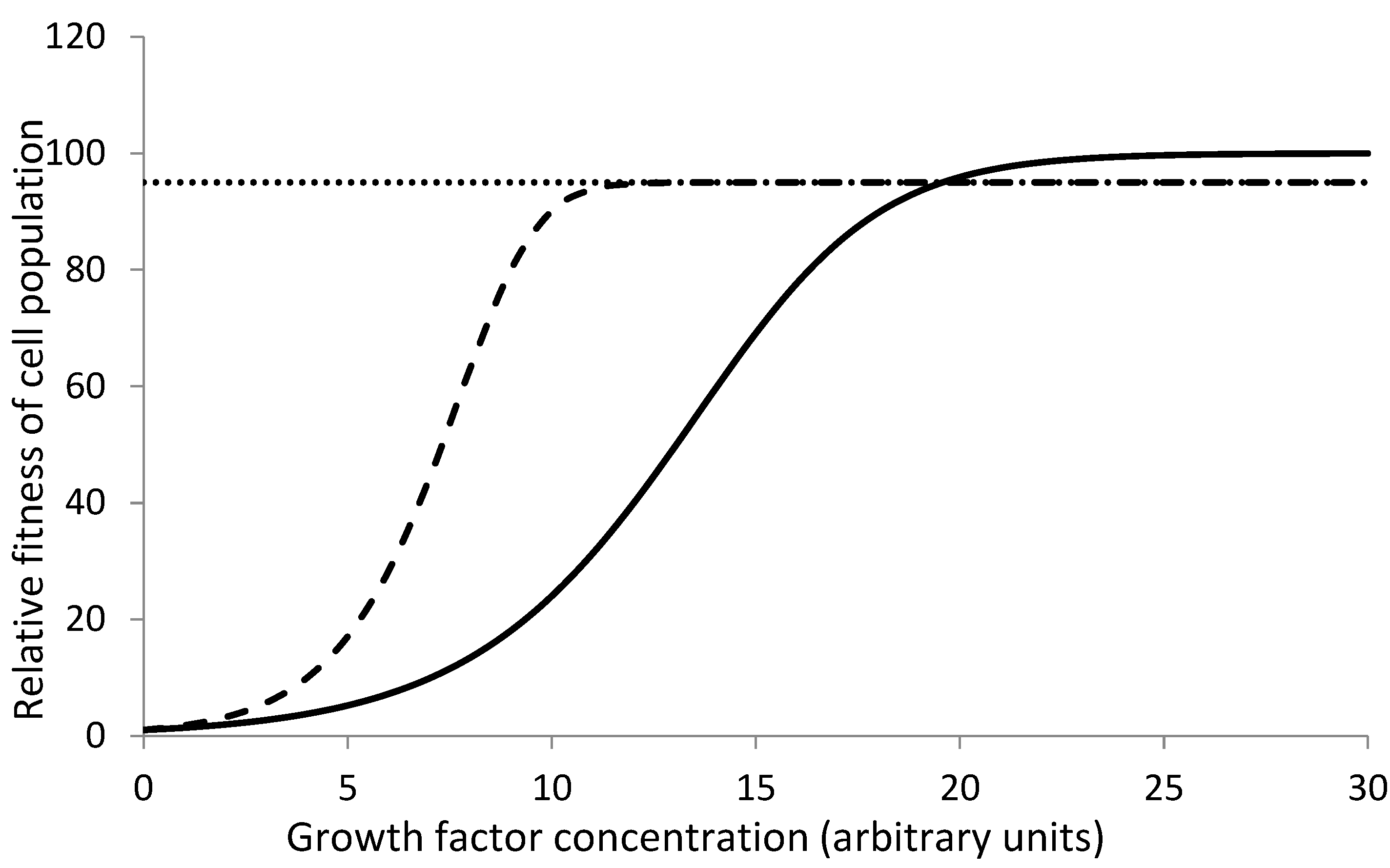

Growth factor deficiency and growth factor independent mutants: This line of thinking exists in literature and there is one example of empirical test as well. Growth factor signaling is one of the crucial mechanisms in the regulation of cell dynamics at both normal and wound healing levels of regulation [11]. Three types of mutations related to EGF signaling are known to occur in different types of cancers. One leads to overexpression of EGF receptor (EGFR), another leads to internal synthesis of EGF by cancer tissue and the third makes pathways downstream of EGF signaling constitutive. In short, the cell becomes partly independent of external EGF signaling. But this implies a higher investment for the cell [12]. If external EGF signal is normal, this extra investment would put the mutant at a slight disadvantage making Rm,h < Rn,h . But if the external signal is weak, any of the three types of mutants will get a selective advantage as in Figure 1, i.e., Rm,a > Rn,a . So a chronically subnormal level of EGF is the context required for the selection of any of the three types of mutants.A similar case with IGF has been demonstrated experimentally by Archetti et al. [10]. In an in vitro experimental competition between IGF II producer and non-producer cells, at low external IFG II, the producer grew better but at higher IGF II the non-producer out-competed the producer. This is a clear empirical demonstration of context based selection.

-

The stem cell renewal differentiation balance:Stem cell dynamics needs asymmetry in the fate of daughter cells. One of them takes the differentiation pathway and another renews to join back to the pool of adult stem cells (ASCs) [13]. Multiple signalling pathways are involved in maintaining this balance. For example, P53 facilitates differentiation whereas EGF facilitates renewal . Baig et al. [11] hypothesized a context based selection on the EGF-P53 balance. If there is a chronic deficiency of EGF signalling, more cells are likely to take the differentiation path and gradually deplete the stem cell pool. Under such circumstances a P53 mutant is more likely to go to renewal, in spite of low EGF, because of which the stem cell pool will get enriched in P53 mutants. But when EGF signalling and stem cell renewal is normal, P53 mutants are less likely to compete with normal stem cells i.e., Rm,h <= Rn,h because the normal functions of P53 including maintenance of mitochondrial efficiency [14,15] are lost. Chronic deficiency of EGF signalling is a possible specific context in which P53 mutants might get selected.Notch signalling is known to facilitate differentiation [16,17] and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) antagonizes Notch signaling in deciding the daughter fate determination after stem cell division [17,18]. BMP is also involved in Iron metabolism and deficiency of Iron leads to lower expression of BMP. In addition BMP expression is also responsive to injury and impacts because that necessitates strengthening of bones [19,20,21]. A combination of sedentary life and iron deficiency is therefore expected to lead to lower BMP expression making Notch induced differentiation excessive. In this context, a Notch under-expressing mutant is likely to get enriched in the ASC population. In contrast when BMP is normal, both the normal ASCs and Notch-inactivating mutants would contribute to the stem cell pool. However, Notch inactivating mutants would have a selective disadvantage due to the necessity of Notch in multiple normal cellular pathways [22,23].One more example is that of Beta-catenin which stimulates stem cell renewal, pleuripotency and mesenchymal transition. WNT signaling is known to stimulate and APC to degrade beta-catenin and a balance in these signaling pathways keeps the stem cell dynamics normal. IGF1 increases expression and stability of beta catenin [25,26,27]. A combination of stress and subnormal IGF signaling will keep beta catenin suppressed due to which stem cell renewal is likely to be subnormal. Under this condition a cell overexpressing beta catenin either by mutated APC or mutated beta catenin itself is more likely to follow the renewal path and therefore get enriched in the stem cell population.

-

Cell cycle and proliferation regulationThe cell cycle is a highly regulated process and the regulation is crucial for tissue homeostasis. Different signalling pathways can facilitate or arrest a given stage of cell cycle. It is tempting to assume that any mutant that relaxes the regulation and allows the cell to proliferate will always get selected. But we see with examples that this is not the case.The retinoblastoma protein pRb regulates the cell cycle mainly by preventing the entry of the cell cycle into S phase and thereby arrests cell proliferation [28]. This is antagonized by growth factors including IFG I, EGF and PDGF acting through CDKCs [29,30,31]. A pRb mutant will not be able to arrest the cell cycle and the mutant cell would proliferate. However whether this mutant gets a selective advantage depends upon the growth factor signaling. In presence of adequate growth factor signals, both normal and mutant calls can proliferate. But pRb has many other functions in the cell including mitochondrial respiration, the electron transport chain, alterations in the mitochondrial polarity and a preference towards glutamine uptake [32] . Therefore when both can proliferate, Rb mutant might be at substantial disadvantage making Rm,h < Rn,h. But when growth factor signals are chronically subnormal, normal cells would remain suppressed making Rm,a > Rn,a .PTEN is a tumor suppressor gene that is frequently mutated or lost in many human cancers. PTEN regulates cell proliferation and a mutation inactivating it may be expected to have an advantage. However PTEN is also important in normal cell functions including mitochondrial functions and genomic stability [33,34]. So it is likely that this disadvantage offsets the possible proliferative advantage to PTEN mutants. Only when the cell cycle remains abnormally suppressed due to some kind of stress or deficiency, PTEN mutants can outcompete.Similarly p16 is a tumor suppressor gene which when inactivated can contribute to cancer development. It is primarily involved in DNA damage repair, maintenance of genome stability, cell cycle and cell proliferation regulation. Under oxidative stress normal cells respond by upregulating p16 expression [35].This upregulation leads to a temporary arrest of cell proliferation allowing the cell to repair oxidative damages. The p16 mutant cell, in contrast, continues to proliferate even in presence of oxidative stress. Therefore under chronic oxidative stress Rm,a > Rn,a . In the absence of oxidative stress while normal cells maintain the regulated proliferation, P16 mutant will be deficient in mitochondrial biogenesis and many other normal functions [36,37] making Rm,h <= Rn,h .

-

Facilitation of angiogenesisAngiogenesis is affected by a number of growth factor and other signals and in sedentary lifestyle many of these signals are deficient. As a result capillary density reduces and so does transport of nutrients and oxygen [38,39,40]. Below a threshold the supply of nutrients, oxygen or growth factors through blood would become growth limiting. In this context if a mutant cell expresses angiogenic signals it can increase local capillary density and thereby is able to proliferate more than others. This advantage may be shared by some of the neighbouring normal cells too and this is a game theoretical problem [10]. In this situation the mutants are expected to get a frequency dependent selective advantage.For example PTEN mutants are known to stimulate angiogenesis through VEGF. This raises the possibility that when angiogenesis is grossly subnormal a PTEN mutant cell stimulates capillary formation around it and get greater nutrient supply [41,42]. Such a cell can get selected over the severely nutrient limited normal cell.

-

Glucose supply for cell proliferationApart from a pro-proliferation signal, cell proliferation also needs adequate energy supply. Therefore restricting glucose uptake or the process of glycolysis can also keep proliferation in check. Insulin is a mitogen as well as a facilitator of glucose uptake but the two functions are executed by different pathways. The insulin receptor INSR-A triggers cell proliferation signals whereas INSR-B is responsible for the pathway leading to glut-4 docking and thereby glucose uptake [43]. In chronic hyperinsulinemia, both the pathways are expected to be upregulated, but that is prevented by a feedback operating through P53 [44,45]. P53 induces insulin resistance because of which glucose uptake remains normal in spite of high insulin. This becomes a case where there is a mitogenic signal but energy restriction puts a limit on proliferation. This is the context in which a P53 mutant can get a selective advantage because it will have upregulated glucose uptake as well. When insulin signalling is normal, this mutant is unlikely to experience any advantage. Instead the normal functions of P53 being impaired, it will be at a disadvantage.

-

Telomerase expression: In stem cell dynamics TERT induces enhanced resistance to cell death under cellular stresses. So TERT overexpression will be beneficial under conditions of stress, but in the absence of stress cells overexpressing TERT would be paying an extra cost of the overexpression and thereby become less competitive than normal cells.Vitamin D deficiency impairs normal telomerase expression [46]. Therefore TERT overexpression may get selected under extreme vit D deficiency.

- (i)

- Many of our hypothesis depend upon altered growth factor expression. The expression of growth factors is behaviour responsive [47,48] and therefore a behavioural mismatch between the ancestral lifestyle in which the human physiology evolved and the modern lifestyle can be a crucial element in the proneness to many modern lifestyle related disorders [49]. Sedentary lifestyle, in particular is likely to create chronic growth factor under-expression and thereby increased chances of cancers. Epidemiological information about growth factor levels is scanty but available studies are compatible with our hypothesis [50,51]. Further other effects of sedentary lifestyle such as obesity are associated with increased cancer risk [52]. Infants with very low birth weight seem to have lower concentrations of IGF-I and IGFBP-3 [53]. As expected by our hypothesis sporadic retinoblastoma are more prevalent in such infants and underweight mothers [54,55].

- (ii)

- (iii)

- (iv)

- A specific anomaly in cancer incidence is that if the somatic evolution of cancers is not mutation limited then why many mutagenic agents are also carcinogenic, although all carcinogens are not mutagenic is a riddle [61,62]. Our hypothesis potentially resolves this anomaly. DNA damage also suppresses the cell cycle, thereby giving time for the DNA repair mechanisms to act. Chronic exposure to mutagenic agents can keep the cell cycle unduly suppressed giving a selective advantage to a mutant escaping the suppression in spite of any metabolic defect the mutation may have induced. In addition to being mutagenic, radiation exposure and other chronic mutagenic exposures also create the selective environment and that completes the causal relationship between mutangens and cancers. Increasing the mutation rate alone is not likely to be sufficient cause of cancer.

- (v)

- Non-mutagenic carcinogens: The presence of non-mutagenic carcinogens [62] itself indicates that something other than mutations js crucial for the somatic evolution of cancer. Whether and how the non-mutagenci carcinogens shape the selective landscape needs to be investigated in detail.

References

- Vibishan, B.; Watve, M.G. Context-dependent selection as the keystone in the somatic evolution of cancer. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 61046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casás-Selves, M.; DeGregori, J. How Cancer Shapes Evolution and How Evolution Shapes Cancer. EvolEduc Outreach 2011, 4, 624–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, A.; Boddy, A.; Mallo, D.; Aktipis, A.; Maley, C.C.; Pepper, J.W. Natural Selection in Cancer Biology: From Molecular Snowflakes to Trait Hallmarks. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017, 7, a029652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozhok, A.I.; DeGregori, J. Aging, Somatic Evolution, and Cancer. In On Human Nature: Biology, Psychology, Ethics, Politics, and Religion; Academic Press: 2017. p. 193–209. [CrossRef]

- Aktipis, C.A.; Nesse, R.M. Evolutionary foundations for cancer biology. Evol Appl. 2013, 6, 144–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktipis, C.A.; Boddy, A.M.; Jansen, G.; Hibner, U.; Hochberg, M.E.; Maley, C.C.; Wilkinson, G.S. Cancer across the tree of life: cooperation and cheating in multicellularity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015, 370, 20140219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktipis, A. The cheating cell: how evolution helps us understand and treat cancer; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Wu, H.; Wiesmüller, L.; et al. Canonical and non-canonical functions of p53 isoforms: potentiating the complexity of tumor development and therapy resistance. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagopati, N.; Belogiannis, K.; Angelopoulou, A.; Papaspyropoulos, A.; Gorgoulis, V. Non-Canonical Functions of the ARF Tumor Suppressor in Development and Tumorigenesis. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archetti, M.; Ferraro, D.A.; Christofori, G. Heterogeneity for IGF-II production maintained by public goods dynamics in neuroendocrine pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 1833–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, U.; Kharate, R.; Watve, M. Somatic evolution of Cancer: A new synthesis [preprint]; 2023. [CrossRef]

- Oña, L.; Lachmann, M. Signalling architectures can prevent cancer evolution. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Y.M.; Yuan, H.; Cheng, J.; Hunt, A.J. Polarity in stem cell division: asymmetric stem cell division in tissue homeostasis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010, 2, a001313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.Q.; Luo, T.T.; Luo, S.C.; Wang, J.Q.; Wang, S.M.; Bai, Y.H.; Yang, Y.L.; Wang, Y.Y. p53 and mitochondrial dysfunction: novel insight of neurodegenerative diseases. J BioenergBiomembr. 2016, 48, 337–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.B.; Kinoshita, C.; Kinoshita, Y.; Morrison, R.S. p53 and mitochondrial function in neurons. BiochimBiophys Acta. 2014, 1842, 1186–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowell, C.S.; Radtke, F. Notch as a tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Cancer 2017, 17, 145–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, A.; Rousset, R. Tissue adaptation to environmental cues by symmetric and asymmetric division modes of intestinal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, A.; Jiang, J. Intestinal epithelium-derived BMP controls stem cell self-renewal in Drosophila adult midgut. eLife 2014, 3, e01857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopf, J.; Petersen, A.; Duda, G.N.; et al. BMP2 and mechanical loading cooperatively regulate immediate early signalling events in the BMP pathway. BMC Biol 2012, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenier, G.; Leblanc, E.; Faucheux, N.; Lauzier, D.; Kloen, P.; Hamdy, R.C. BMP-9 expression in human traumatic heterotopic ossification: a case report. Skelet Muscle 2013, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaleno da Silva, C.; Jatzlau, J.; Knaus, P. BMP signalling in a mechanical context–implications for bone biology. Bone. 2020, 137, 115416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, N.P.; Roy, A.; Banerjee, S. Alteration of mitochondrial proteome due to activation of Notch1 signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2014, 289, 7320–7334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perumalsamy, L.R.; Nagala, M.; Sarin, A. Notch-activated signaling cascade interacts with mitochondrial remodeling proteins to regulate cell survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010, 107, 6882–6887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Robitaille, A.M.; Berndt, J.D.; Davidson, K.C.; Fischer, K.A.; Mathieu, J.; Moon, R.T. Wnt/β-catenin signaling promotes self-renewal and inhibits the primed state transition in naïve human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, E6382–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamos, J.L.; Weis, W.I. The β-catenin destruction complex. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013, 5, a007898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Kang, H.G.; Jeon, S.B.; et al. IGF-1 promotes trophectoderm cell proliferation of porcine embryos by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Cell Commun Signal. 2025, 23, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Playford, M.P.; Bicknell, D.; Bodmer, W.F.; Macaulay, V.M. Insulin-like growth factor 1 regulates the location, stability, and transcriptional activity of β-catenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 12103–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talluri, S.; Dick, F.A. Regulation of transcription and chromatin structure by pRB: Here, there and everywhere. Cell Cycle 2012, 11, 3189–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furlanetto, R.W.; Harwell, S.E.; Frick, K.K. Insulin-like growth factor-I induces cyclin-D1expression in MG63 human osteosarcoma cells in vitro. Mol Endocrinol 1994, 8, 510–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, S.M.; Cheng, Z.Q. Opposing early and late effects of insulin-like growth factor I on differentiation and the cell cycle regulatory retinoblastoma protein in skeletal myoblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Regulation of cell cycle progression by growth factor-induced cell signaling. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolay, B.N.; Dyson, N.J. The multiple connections between pRB and cell metabolism. CurrOpin Cell Biol 2013, 25, 735–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Yang, J.; Yang, C.; Zhu, M.; Jin, Y.; McNutt, M.A.; Yin, Y. PTENα regulates mitophagy and maintains mitochondrial quality control. Autophagy 2018, 14, 1742–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Yang, M.; Gui, H.; Wang, M. PTEN regulates mitochondrial biogenesis via the AKT/GSK-3β/PGC-1α pathway in autism. Neuroscience 2021, 465, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, N.C.; Liu, T.; Cassidy, P.; Leachman, S.A.; Boucher, K.M.; Goodson, A.G.; Grossman, D. The p16INK4A tumor suppressor regulates cellular oxidative stress. Oncogene 2011, 30, 265–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, E.; Liu, B.; Li, C.; Liu, T.; Rutter, J.; Grossman, D. Loss of p16INK4A stimulates aberrant mitochondrial biogenesis through a CDK4/Rb-independent pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 55848–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buj, R.; Aird, K.M. p16: cycling off the beaten path. Mol Cell Oncol 2019, 6, e1677140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.J.; et al. Blunted rise in brain glucose levels during hyperglycemia in adults with obesity and T2DM. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e95913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groen, B.B.; Hamer, H.M.; Snijders, T.; van Kranenburg, J.; Frijns, D.; Vink, H.; van Loon, L.J. Skeletal muscle capillary density and microvascular function are compromised with aging and type 2 diabetes. J ApplPhysiol 2014, 116, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akanksha Ojha Milind Watve (2023) Reduced blood to brain glucose transport as the cause for hyperglycemia: a model that resolves multiple anomalies in type 2 diabetes Qeios, G.L.5.2.D.B. Akanksha Ojha Milind Watve (2023) Reduced blood to brain glucose transport as the cause for hyperglycemia: a model that resolves multiple anomalies in type 2 diabetes Qeios, G.L.5.2.D.B. https://www.qeios.com/read/GL52DB.

- Huang, J.; Kontos, C.D. PTEN modulates vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated signaling and angiogenic effects. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 10760–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, S.; Huynh-Do, U. The role of PTEN in tumor angiogenesis. J Oncol 2012, 2012, 141236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfiore, A.; Malaguarnera, R.; Vella, V.; Lawrence, M.C.; Sciacca, L.; Frasca, F.; Morrione, A.; Vigneri, R. Insulin Receptor Isoforms in Physiology and Disease: An Updated View. Endocr Rev 2017, 38, 379–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strycharz, J.; Drzewoski, J.; Szemraj, J.; Sliwinska, A. Is p53 Involved in Tissue-Specific Insulin Resistance Formation? Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017, 9270549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamino, T.; Orimo, M.; Shimizu, I.; Kunieda, T.; Yokoyama, M.; Ito, T.; Komuro, I. A crucial role for adipose tissue p53 in the regulation of insulin resistance. Nat Med 2009, 15, 1082–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Manson, J.E.; Cook, N.R.; et al. Vitamin D3 and marine ω-3 fatty acids supplementation and leukocyte telomere length: 4-year findings from the VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL) randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2025, 122, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloe, L.; Bracci-Laudiero, L.; Alleva, E.; Lambiase, A.; Micera, A.; Tirassa, P. Emotional stress induced by parachute jumping enhances blood nerve growth factor levels and the distribution of nerve growth factor receptors in lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994, 91, 10440–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nexø, E.; Olsen, P.S.; Poulsen, K. Exocrine and endocrine secretion of renin and epidermal growth factor from the mouse submandibular glands. RegulPept 1984, 8, 327–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watve, M.; Sardeshmukh, A.K. “Vitaction” deficiency: a possible root cause for multiple lifestyle disorders including Alzheimer’s disease. ExplorNeuroprotTher 2024, 4, 108–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford, G.E.; Tayari, L.; Barfoot, M.D.; Peck, A.B.; Tanaka, Y.; Humphreys-Beher, M.G. Salivary EGF levels reduced in diabetic patients. J Diabetes Complications 2000, 14, 140–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasayama, S.; Ohba, Y.; Oka, T. Epidermal growth factor deficiency associated with diabetes mellitus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1989, 86, 7644–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, S.; Irfan, W.; Jameel, A.; Ahmed, S.; Shahid, R.K. Obesity and cancer: a current overview of epidemiology, pathogenesis, outcomes, and management. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajantie, E. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, IGF binding protein (IGFBP)-3, phosphoisoforms of IGFBP-1 and postnatal growth in very-low-birth-weight infants. Horm Res 2003, 60(Suppl 3), 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, J.E.; Omidakhsh, N.; Azary, S.; Ritz, B.; von Ehrenstein, O.S.; Bunin, G.R.; Ganguly, A. A case-control study of sporadic retinoblastoma in relation to maternal health conditions and reproductive factors: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, L.G.; Puumala, S.E.; Carozza, S.E.; Chow, E.J.; Fox, E.E.; Horel, S.; et al. Cancer risk among children with very low birth weights. Pediatrics 2009, 124, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Liu, X.; Lin, E.J.D.; Wang, C.; Choi, E.Y.; Riban, V.; Lin, B.; During, M.J. Environmental and genetic activation of a brain–adipocyte BDNF/leptin axis causes cancer remission and inhibition. Cell 2010, 142, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa Fernandes, M.S.; Santos, G.C.J.; Filgueira, T.O.; Gomes, D.A.; Barbosa, E.A.S.; Dos Santos, T.M.; Câmara, N.O.S.; Castoldi, A.; SoutoFO. Cytokines and immune cells profile in different tissues of rodents induced by environmental enrichment: systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 11986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, S.; Mo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, B.; Liao, Q.; Zhou, M.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Xiong, W.; Li, G.; Guo, C.; Zeng, Z. Chronic stress promotes cancer development. Front Oncol. 2020, 10, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, N.; Shen, C.C.; Hu, Y.W.; Hu, L.Y.; Yeh, C.M.; Teng, C.J.; et al. Risk of cancer in patients with iron deficiency anemia: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0119647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuolo, L.; Faggiano, A.; Colao, A. Vitamin D and cancer. Front Endocrinol 2012, 3, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosendahl Huber, A.; Van Hoeck, A.; Van Boxtel, R. The mutagenic impact of environmental exposures in human cells and cancer: imprints through time. Front Genet. 2021, 12, 760039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordic Council of Ministers Staff. Non-mutagenic carcinogens: mechanisms and test methods. Tema-Nord: Environment, Issue 601. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers; 1998. 88 p.

| Condition | Normal ASCs(n) | Mutant ASCs(m) |

| Healthy micro-environment (h) | Rn,h | Rm,h |

| Altered micro-environment (a) | Rn,a | Rm,a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).