Submitted:

10 September 2025

Posted:

12 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Nitrogen Metabolism in Prokaryotes

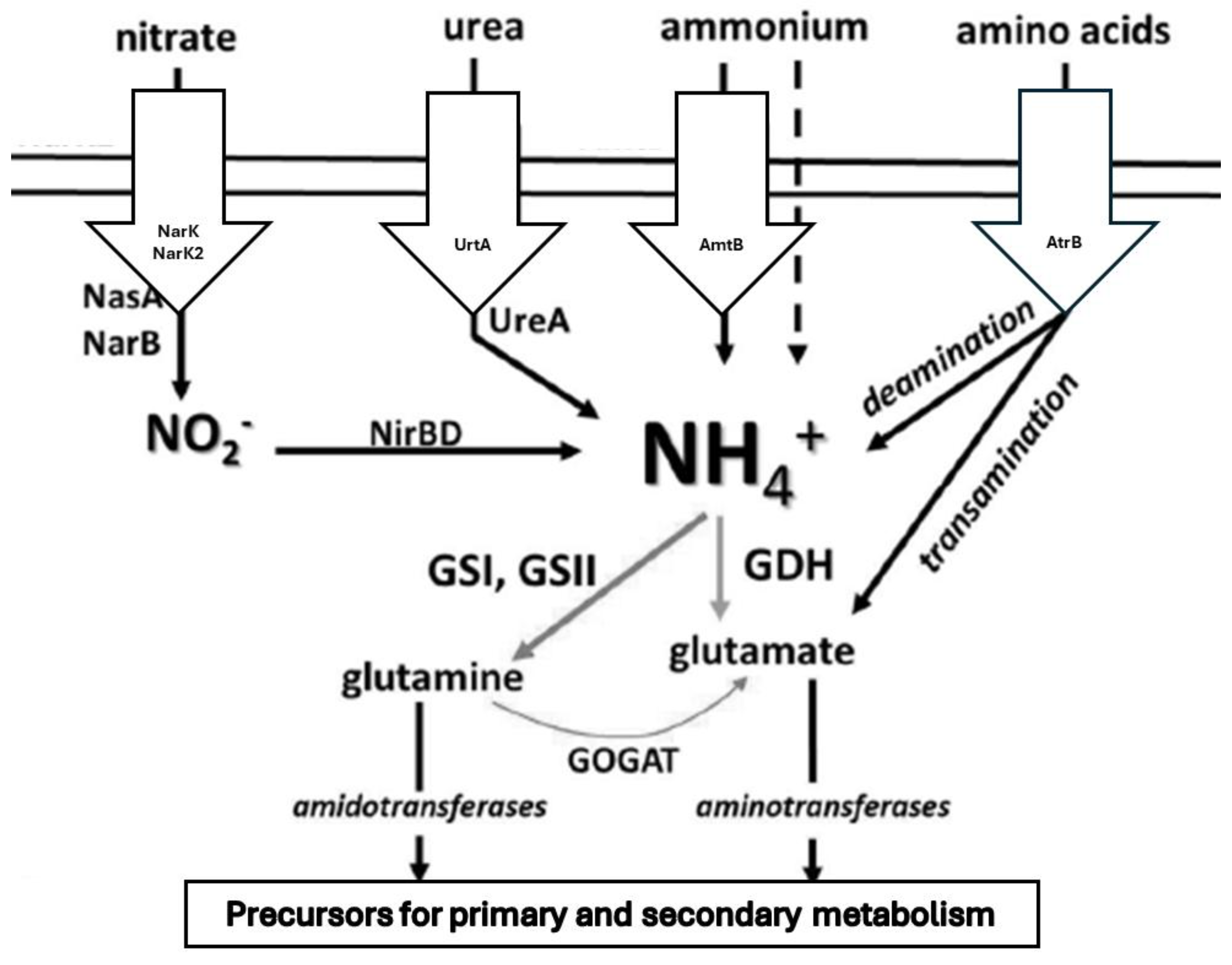

1.1. Nitrogen Uptake and Nitrogen Assimilation in Actinobacteria

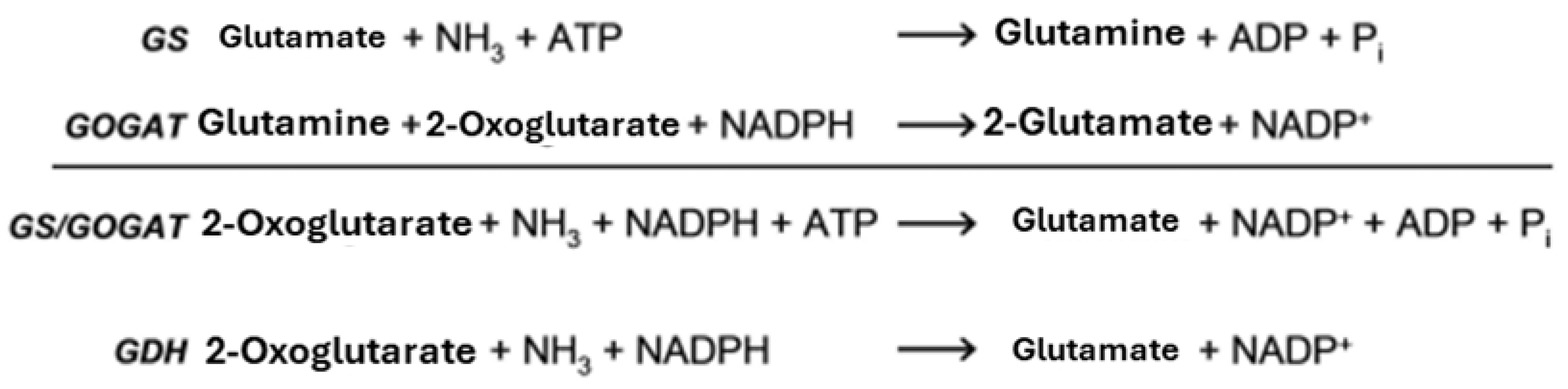

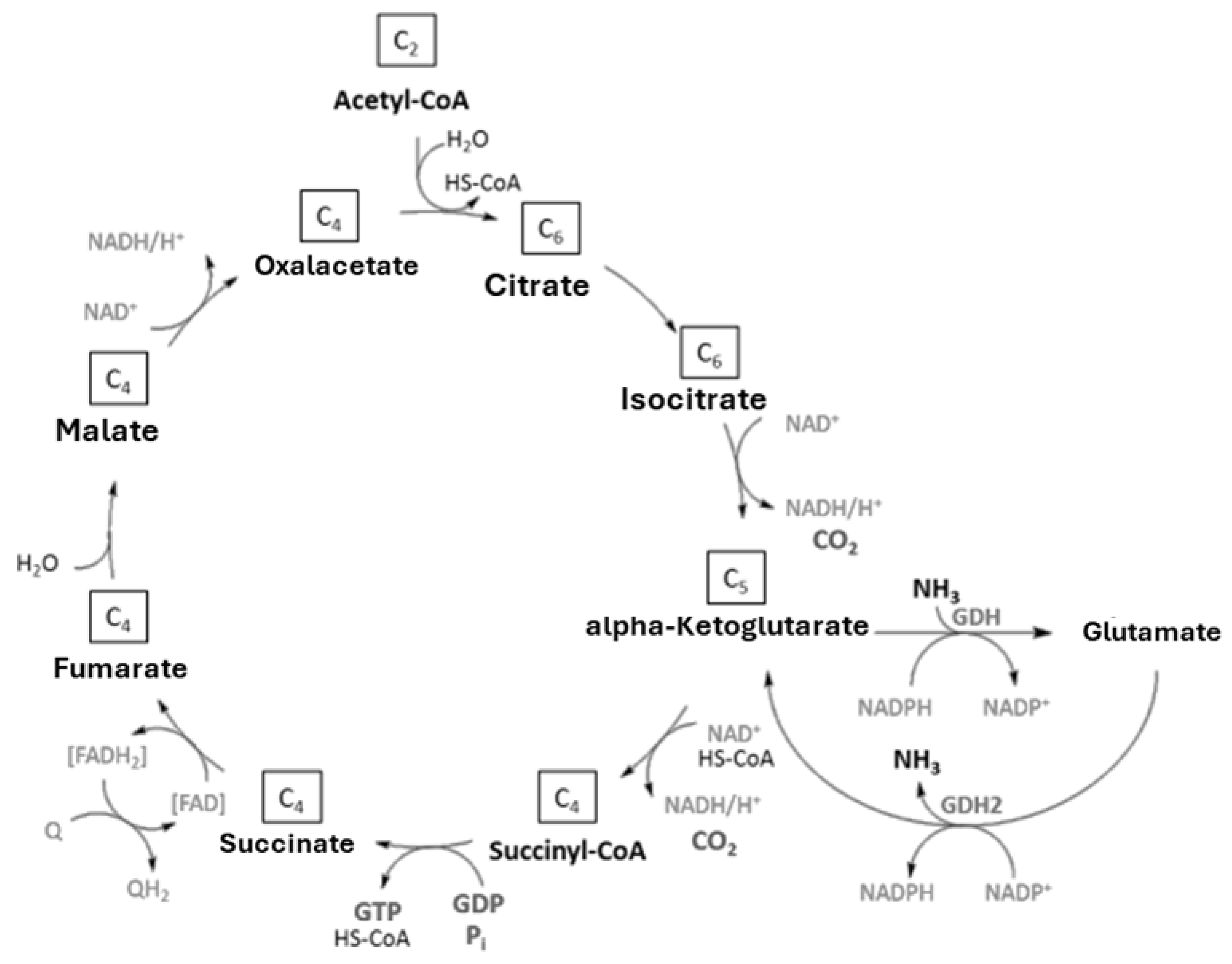

1.1.2. Nitrogen Assimilation in Actinomycetes: ammonium catabolism as central catabolic route

1.1.2.1. Nitrogen Assimilation in Actinomycetales: catabolism of poor nitrogen sources

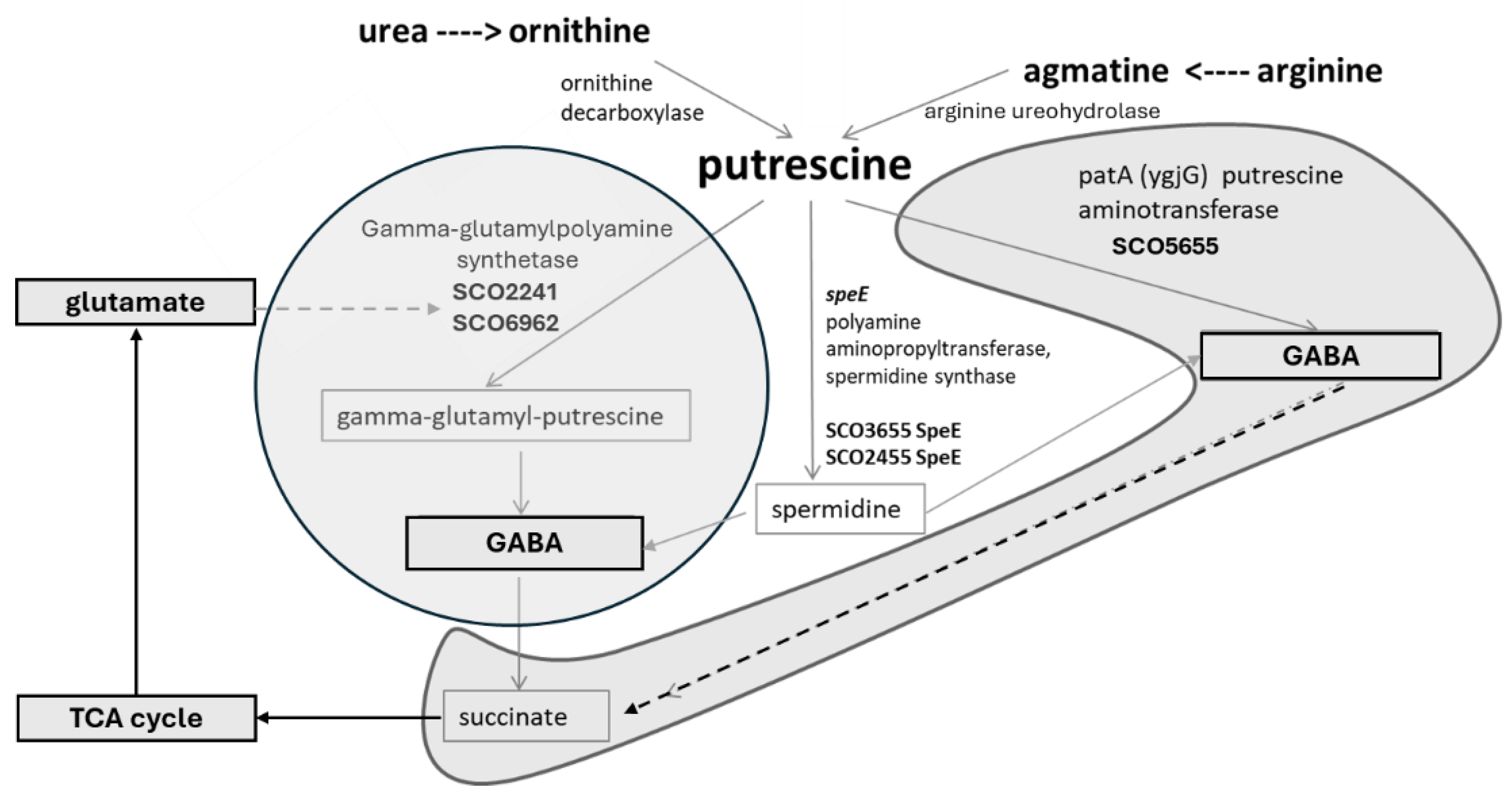

1.1.2.2. Assimilation of Amines in Actinomycetes

1.1.3. Nitrogen Assimilation in Actinomycetales – Transcriptional Regulation

1.1.3.1. Regulation of Central Pathways

1.1.3.2. Regulation of Catabolism of Amines in Actinomycetes

3. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aharonowitz, Y. Nitrogen metabolite regulation of antibiotic biosynthesis. Annu Rev Microbiol 1980, 34, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allaway, D.; Lodwig, E.; Crompton, L.A.; Wood, M.; Parsons, R.; Wheeler, T.R.; Poole, P.S. Identification of alaninedehydrogenase and its role in mixed secretion of ammonium andalanine by pea bacteroids. Mol Microbiol 2000, 36, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, R.; Reuther, J.; Bera, A.; Wohlleben, W.; Mast, Y. A novel GlnR target gene, nnaR, is involved in nitrate/nitrite assimilation in Streptomyces coelicolor. Microbiology 2012, 158, 1172–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, R.; Franz-Wachtel, M.; Tiffert, Y.; Heberer, M.; Meky, M.; Ahmed, Y.; Matthews, A.; Krysenko, S.; Jakobi, M.; Hinder, M.; Moore, J.; Okoniewski, N.; Maček, B.; Wohlleben, W.; Bera, A. Post-translational Serine/Threonine Phosphorylation and Lysine Acetylation: A Novel Regulatory Aspect of the Global Nitrogen Response Regulator GlnR in S. coelicolor M145. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2016, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amon, J.; Bräu, T.; Grimrath, A.; Hänßler, E.; Hasselt, K.; Höller, M.; Jeßberger, N.; Ott, L.; Szököl, J.; Titgemeyer, F.; Burkovski, A. Nitrogen control in Mycobacterium smegmatis: Nitrogen-dependent expression of ammonium transport and assimilation proteins depends on OmpR-type regulator GlnR. J Bacteriol 2008, 190, 7108–7116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.R.; Ninfa, A.J. Mutational analysis of the bacterial signal-transducing protein kinase/phosphatase nitrogen regulator II (NRII or NtrB). J Bacteriol 1993, 175, 7016–7023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.R.; Ninfa, A.J. Role of the GlnK signal transduction protein in the regulation of nitrogen assimilation in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 1998, 29, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.R.; Ninfa, A.J. Characterization of the GlnK protein of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 1999, 32, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.R.; Blauwkamp, T.A.; Bondarenko, V.; Studitsky, V.; Ninfa, A.J. Activation of the glnA, glnK, and nac promoters as Escherichia coli undergoes the transition from nitrogen excess growth to nitrogen starvation. J Bacteriol 2002, 184, 5358–5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.R.; Kamberov, E.S.; Weiss, R.L.; Ninfa, A.J. Reversible uridylylation of the Escherichia coli PII signal transduction protein regulates its ability to stimulate the dephosphorylation of the transcription factor nitrogen regulator I (NRI or NtrC). J Biol Chem 1994, 269, 28288–28293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascaran, V.; Hardisson, C.; Brana, A.F. Regulation of nitrogen catabolic enzymes in Streptomyces clavuligerus. J Gen Microbiol 1989, 135, 2465–2474. [Google Scholar]

- Beckers, G.; Strösser, J.; Hildebrandt, U.; Kalinowski, J.; Farwick, M.; Krämer, R.; Burkovski, A. Regulation of AmtR-controlled gene expression in Corynebacterium glutamicum: Mechanism and characterization of the AmtR regulon. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 58, 580–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrmann, I.; Hillemann, D.; Pühler, A.; Strauch, E.; Wohlleben, W. Overexpression of a Streptomyces viridochromogenes gene (glnII) encoding a glutamine synthetase similar to those of eucaryotes confers resistance against the antibiotic phosphinothricyl-alanyl-alanine. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 5326–5334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, S.D.; Chater, K.F.; Cerdeño-Tárraga, A.-M.; Challis, G.L.; Thomson, N.R.; James, K.D.; Harris, D.E.; Quail, M.A.; Kieser, H.; Harper, D.; A., *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. Complete Genome Sequence of the Model Actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 2002, 417, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besson, S.; Almeida, M.G.; Silveira, C.M. Nitrite reduction in bacteria: A comprehensive view of nitrite reductases. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2022, 464, 214560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, M.; Hanfrey, C.C.; Kinch, L.N.; Elliot, K.A.; Michael, J.A. Evolution of a novel lysine decarboxylase in siderophore biosynthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2012, 86, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipeva, V.; Dumanova, E.; Todorov, T.; et al. Impact of nitrogen assimilation on regulation of antibiotic production in Streptomyces hygroscopicus 155. Antibiot Khimioter 1991, 36, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.S. (1998) A Guide to Polyamines, Oxford University Press, New York.

- Darrow, R.A.; Knotts, R.R. Two forms of glutamine synthetase in free-living root-nodule bacteria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1977, 78, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, K.L.; Katze, J.R.; Kane, J.F. Effect of glutamine on enzymes of nitrogen metabolism in Bacillus subtilis. Journal of bacteriology 1981, 145, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmands, J.; Noridge, N.A.; Benson, D.R. The actinorhizal root-nodule symbiont Frankia sp. strain CpI1 has two glutamine synthetases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987, 84, 6126–6130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, P.C. Glutamate dehydrogenases: The why and how of coenzyme specificity. Neurochemical research 2014, 39, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensinck, D.; Gerhardt, E.C.M.; Rollan, L.; Huergo, L.F.; Gramajo, H.; Diacovich, L. The PII protein interacts with the Amt ammonium transport and modulates nitrate/nitrite assimilation in mycobacteria. Frontiers in microbiology 2024, 15, 1366111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, D.; Falke, D.; Wohlleben, W.; Engels, A. Nitrogen metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2): Modification of glutamine synthetase I by an adenylyltransferase. Microbiology 1999, 145 Pt 9, 2313–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, D.; Weißschuh, N.; Reuther, J.; Wohlleben, W.; Engels, A. Two transcriptional regulators GlnR and GlnRII are involved in regulation of nitrogen metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol Microbiol 2002, 46, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, S.H. Glutamate synthesis in Streptomyces coelicolor. J Bacteriol 1989, 171, 2372–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, S.H.; Sonenshein, A.L. Control of carbon and nitrogen metabolism in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Microbiol 1991, 45, 107–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, M.; Alderson, J.; van Keulen, G.; White, J.; Sawers, R.G. The obligate aerobe Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) synthesizes three active respiratory nitrate reductases. Microbiology (Reading, England) 2010, 156 Pt 10, 3166–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Falke, D.; Sawers, R.G. A respiratory nitrate reductase active exclusively in resting spores of the obligate aerobe Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Molecular microbiology 2013, 89, 1259–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Falke, D.; Pawlik, T.; Sawers, R.G. Oxygen-dependent control of respiratory nitrate reduction in mycelium of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Journal of bacteriology 2014, 196, 4152–4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forchhammer, K. Glutamine signalling in bacteria. Front Biosci 2007, 12, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G. (Hrsg.), (2022) Allgemeine Mikrobiologie, 880 S, 750 Abb., Thieme, 11. vollst. überarb. Aufl., HC, ISBN: 9783132434776.

- Gerlt, J.A. Tools and strategies for discovering novel enzymes and metabolic pathways. Perspect. Sci. 2016, 9, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshroy, S.; Binder, M.; Tartar, A.; Robertson, D.L. Molecular evolution of glutamine synthetase II: Phylogenetic evidence of a non-endosymbiotic gene transfer event early in plant evolution. BMC Evol Biol 2010, 10, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goddard, A.D.; Moir, J.W.; Richardson, D.J.; Ferguson, S.J. Interdependence of two NarK domains in a fused nitrate/nitrite transporter. Molecular microbiology 2008, 70, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goddard, A.D.; Bali, S.; Mavridou, D.A.; Luque-Almagro, V.M.; Gates, A.J.; Dolores Roldán, M.; Newstead, S.; Richardson, D.J.; Ferguson, S.J. The Paracoccus denitrificans NarK-like nitrate and nitrite transporters-probing nitrate uptake and nitrate/nitrite exchange mechanisms. Molecular microbiology 2017, 103, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harth, G.; Maslesa-Galic, S.; Tullius, M.V.; Horwitz, M.A. All four Mycobacterium tuberculosis glnA genes encode glutamine synthetase activities but only GlnA1 is abundantly expressed and essential for bacterial homeostasis. Mol Microbiol 2005, 58, 1157–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, A.; Woyda, K.; Brauburger, K.; Meiss, G.; Detsch, C.; Stülke, J.; Forchhammer, K. Interaction of the membrane-bound GlnK-AmtB complex with the master regulator of nitrogen metabolism TnrA in Bacillus subtilis. The Journal of biological chemistry 2006, 281, 34909–34917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesketh, A.; Fink, D.; Gust, B.; Rexer, H.U.; Scheel, B.; Chater, K.; et al. The GlnD and GlnK homologues of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) are functionally dissimilar to their nitrogen regulatory system counterparts from enteric bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 46, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, S.A.; Welsh, A.; Orellana, L.H.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Chee-Sanford, J.C.; Sanford, R.A.; Schadt, C.W.; Löffler, F.E. Detection and Diversity of Fungal Nitric Oxide Reductase Genes (p450nor) in Agricultural Soils. Applied and environmental microbiology 2016, 82, 2919–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillemann, D.; Dammann, T.; Hillemann, A.; Wohlleben, W. Genetic and biochemical characterization of the two glutamine synthetases GSI and GSII of the phosphinothricyl-alanyl-alanine producer, Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494. Journal of general microbiology 1993, 139, 1773–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojati, Z.; Milne, C.; Harvey, B.; Gordon, L.; Borg, M.; et al. Structure, biosynthetic origin, and engineered biosynthesis of calcium-dependent antibiotics from Streptomyces coelicolor. Chem Biol 2002, 9, 1175–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, D.A. The Leeuwenhoek Lecture, 1987: Towards an understanding of gene switching in Streptomyces, the basis of sporulation and antibiotic production. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1988, 235, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopwood, D.A.; Chater, K.F.; Bibb, M.J. Genetics of antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2), a model streptomycete. Biotechnology 1995, 28, 65–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopwood, D.A. Forty years of genetics with Streptomyces: From in vivo through in vitro to in silico. Microbiology 1999, 145, 2183–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, N.H.; Kirby, R. Comparative genomics of Streptomyces avermitilis, Streptomyces cattleya, Streptomyces maritimus and Kitasatospora aureofaciens using a Streptomyces coelicolor microarray system. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2008, 93, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, R.C.; Daniel, R.M. L-glutamate dehydrogenases: Distribution, properties and mechanism. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. B, Comparative biochemistry 1993, 106, 767–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, K.; Kashiwagi, K. Polyamines: Mysterious modulators of cellular functions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 271, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakoby, M.; Nolden, L.; Meier-Wagner, J.; Krämer, R.; Burkovski, A. AmtR, a global repressor in the nitrogen regulation system of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Molecular microbiology 2000, 37, 964–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, R.P.; Succurro, A.; Kopriva, S. Nitrogen Substrate Utilization in Three Rhizosphere Bacterial Strains Investigated Using Proteomics. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, V.A.; Barton, G.R.; Robertson, B.D.; Williams, K.J. Genome wide analysis of the complete GlnR nitrogen-response regulon in Mycobacterium smegmatis. BMC Genomics 2013, 14, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeßberger, N.; Lu, Y.; Amon, J.; Titgemeyer, F.; Sonnewald, S.; Reid, S.; Burkovski, A. Nitrogen starvation-induced transcriptome alterations and influence of transcription regulator mutants in Mycobacterium smegmatis. BMC research notes 2013, 6, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaak, J.B.; Leung, H.-W.; Stott, W.T.; Busch, J.; Bilsky, J. Toxicology of mono-, di-, and triethanolamine. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1997, 149, 1–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krysenko, S.; Okoniewski, N.; Kulik, A.; Matthews, A.; Grimpo, J.; Wohlleben, W.; Bera, A. Gamma-Glutamylpolyamine Synthetase GlnA3 is involved in the first step of polyamine degradation pathway in Streptomyces coelicolor M145. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krysenko, S.; Matthews, A.; Busche, T.; Bera, A.; Wohlleben, W. Poly- and Monoamine Metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor: The New Role of Glutamine Synthetase-Like Enzymes in the Survival under Environmental Stress. Microb. Physiol. 2021, 31, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysenko, S.; Matthews, A.; Okoniewski, N.; Kulik, A.; Girbas, M.G.; Tsypik, O.; Meyners, C.S.; Hausch, F.; Wohlleben, W.; Bera, A. Initial metabolic step of a novel ethanolamine utilization pathway and its regulation in Streptomyces coelicolor M145. mBio. 2019, 10, e00326–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysenko, S.; Okoniewski, N.; Nentwich, M.; Matthews, A.; Bäuerle, M.; Zinser, A.; Busche, T.; Kulik, A.; Gursch, S.; Kemeny, A.; et al. A Second Gamma-Glutamylpolyamine Synthetase, GlnA2, Is Involved in Polyamine Catabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysenko, S.; Lopez, M.; Meyners, C.; Purder, P.L.; Zinser, A.; Hausch, F.; Wohlleben, W. A novel synthetic inhibitor of polyamine utilization in Streptomyces coelicolor. FEMS microbiology letters 2023, 370, fnad096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysenko, S.; Emani, C.S.; Bäuerle, M.; Oswald, M.; Kulik, A.; Meyners, C.; Hillemann, D.; Merker, M.; Prosser, G.; Wohlers, I.; Hausch, F.; Brötz-Oesterhelt, H.; Mitulski, A.; Reiling, N.; Wohlleben, W. GlnA3Mt is able to glutamylate spermine but it is not essential for the detoxification of spermine in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of bacteriology 2025, 207, e0043924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysenko, S.; Wohlleben, W. Role of Carbon, Nitrogen, Phosphate and Sulfur Metabolism in Secondary Metabolism Precursor Supply in Streptomyces spp. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1571. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumada, Y.; Benson, D.R.; Hillemann, D.; Hosted, T.J.; Rochefort, D.A.; Thompson, C.J.; Wohlleben, W.; Tateno, Y. Evolution of the glutamine synthetase gene, one of the oldest existing and functioning genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 3009–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, S.; Oda, S.; Tsuboi, Y.; Kim, H.G.; Oshida, M.; Kumagai, H.; Suzuki, H. γ-Glutamylputrescine synthetase in the putrescine utilization pathway of Escherichia coli K-12. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 19981–19990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, S.; Sakai, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Muth, A.; Ot, P.; Rather, P.N. Putrescine importer PlaP contributes to swarming motility and urothelial cell invasion in Proteus mirabilis. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 15668–15676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, S.; Oda, S.; Kato, K.; Kim, H.G.; Koyanagi, T.; Kumagai, H.; Suzuki, H. A novel putrescine utilization pathway involves γ-glutamylated intermediates of Escherichia coli K-12. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 4602–4608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusano, T.; Suzuki, H. (eds). (2015) Polyamines: A Universal Molecular Nexus for Growth, Survival, and Specialized Metabolism. Tokyo: Springer.

- Kawakami, R.; Sakuraba, H.; Ohshima, T. Gene cloning and characterization of the very large NAD-dependent l-glutamate dehydrogenase from the psychrophile Janthinobacterium lividum, isolated from cold soil. Journal of bacteriology 2007, 189, 5626–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, D.H.; Lu, C.D. Polyamines induce resistance to cationic peptide, aminoglycoside, and quinolone antibiotics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2006, 50, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Wang, Y.; Han, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; et al. Atypical OmpR/PhoB subfamily response regulator GlnR of actinomycetes functions as a homodimer, stabilized by the unphosphorylated conserved Asp-focused charge interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 15413–15425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magasanik, B. Genetic control of nitrogen assimilation in bacteria. Annual review of genetics 1982, 16, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhoba, X.H.; Krysenko, S. Drug Target Validation in Polyamine Metabolism and Drug Discovery Advancements to Combat Tuberculosis. Future Pharmacology 2025, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrick, M.J.; Edwards, R.A. Nitrogen control in bacteria. Microbiological reviews 1995, 59, 604–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, A.J. Polyamine function in archaea and bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 18693–18701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Fleming, L.; Olin-Sandoval, V.; Campbell, K.; Ralser, M. Remaining Mysteries of Molecular Biology: The Role of Polyamines in the Cell. J. Mol. Biol. 2015, 427, 3389–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhl, D.; Jessberger, N.; Hasselt, K.; Jardin, C.; Sticht, H.; Burkovski, A. DNA binding by Corynebacterium glutamicum TetR-type transcription regulator AmtR. BMC molecular biology 2009, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neidharth, F.C.; Reitzer, L.J. (1996). Regulation of nitrogen utilization Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology (pp. 1344–1356). Washington, DC: ASM Press.

- Ninfa, A.J.; Jiang, P.; Atkinson, M.R. Integration of antagonistic signals in the regulation of nitrogen assimilation in Escherichia coli. Curr Top Cell Regul 2001, 36, 31–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolden, L.; Farwick, M.; Kramer, R.; Burkovski, A. Glutamine synthetases of Corynebacterium glutamicum: Transcriptional control and regulation of activity. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2001, 201, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Redondo, R.; Rodriguez-Garcia, A.; Botas, A.; Santamarta, I.; Martin, J.F.; Liras, P. ArgR of Streptomyces coelicolor is a versatile regulator. PLoS ONE. 2012, 7, e32697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radchenko, M.V.; Thornton, J.; Merrick, M. Control of AmtB-GlnK complex formation by intracellular levels of ATP, ADP, and 2-oxoglutarate. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 31037–31045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radchenko, M.V.; Thornton, J.; Merrick, M. P(II) signal transduction proteins are ATPases whose activity is regulated by 2-oxoglutarate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013, 110, 12948–12953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehm, N.; Buchinger, S.; Strosser, J.; Dotzauer, A.; Walter, B.; Hans, S.; Bathe, B.; Schomburg, D.; Kramer, R.; Burkovski, A. Impact of adenylyltransferase GlnE on nitrogen starvation response in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biotechnol 2010, 145, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitzer, L. Nitrogen assimilation and global regulation in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Microbiol 2003, 57, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitzer, L.; Schneider, B.L. Metabolic context and possible physiological themes of σ54-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2001, 65, 422–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuther, J.; Wohlleben, W. Nitrogen metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor: Transcriptional and post-translational regulation. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 2007, 12, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rexer, H.U.; Schäberle, T.; Wohlleben, W.; Engels, A. ; Investigation of the functional properties and regulation of three glutamine synthetase-like genes in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Arch Microbiol 2006, 186, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, D.J.; Berks, B.C.; Russell, D.A.; Spiro, S.; Taylor, C.J. Functional, biochemical and genetic diversity of prokaryotic nitrate reductases. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS 2001, 58, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, C.D.; Allen, J.W.; Higham, C.W.; Koppenhofer, A.; Zajicek, R.S.; Watmough, N.J.; Ferguson, S.J. Cytochrome cd1, reductive activation and kinetic analysis of a multifunctional respiratory enzyme. The Journal of biological chemistry 2002, 277, 3093–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San Francisco, B.; Zhang, X.; Whalen, K.; Gerlt, K. A novel pathway for bacterial ethanolamine metabolism. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 573.45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.; Vining, L.C. Nitrogen metabolism and chloramphenicol production in Streptomyces venezuelae. Canadian journal of microbiology 1983, 29, 1706–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, V. Dual interacting two-component regulatory systems mediate nitrate- and nitrite-regulated gene expression in Escherichia coli. Res Microbiol 1994, 145, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, J.F.; Basu, P. Evolution of nitrate reductase: Molecular and structural variations on a common function. Chembiochem: A European journal of chemical biology 2002, 3, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streicher, S.L.; Tyler, B. Regulation of glutamine synthetase activity by adenylylation in the Gram-positive bacterium Streptomyces cattleya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1981, 78, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strösser, J.; Ludke, A.; Schaffer, S.; Kramer, R.; Burkovski, A. Regulation of GlnK activity: Modification, membrane sequestration and proteolysis as regulatory principles in the network of nitrogen control in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Mol Microbiol 2004, 54, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeo, M.; Ohara, A.; Sakae, S.; Okamoto, Y.; Kitamura, C.; Kato, D.; Negoro, S. Function of a glutamine synthetase-like protein in bacterial aniline oxidation via γ-glutamylanilide. Journal of bacteriology 2013, 195, 4406–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiffert, Y.; Franz-Wachtel, M.; Fladerer, C.; Nordheim, A.; Reuther, J.; Wohlleben, W.; Mast, Y. Proteomic analysis of the GlnR-mediated response to nitrogen limitation in Streptomyces coelicolor M145. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2011, 89, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiffert, Y.; Supra, P.; Wurm, R.; Wohlleben, W.; Wagner, R.; Reuther, J. The Streptomyces coelicolor GlnR regulon: Identification of new GlnR targets and evidence for a central role of GlnR in nitrogen metabolism in actinomycetes. Mol Microbiol 2008, 67, 861–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, B. Regulation of the assimilation of nitrogen compounds. Annu Rev Biochem 1978, 47, 1127–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Heeswijk, W.C.; Hoving, S.; Molenaar, D.; Stegeman, B.; Kahn, D.; Westerhoff, H.V. An alternative PII protein in the regulation of glutamine synthetase in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 1996, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voelker, F.; Altaba, S. Nitrogen source governs the patterns of growth and pristinamycin production in 'Streptomyces pristinaespiralis'. Microbiology (Reading, England) 2001, 147 Pt 9, 2447–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gunsalus, R.P. The nrfA and nirB nitrite reductase operons in Escherichia coli are expressed differently in response to nitrate than to nitrite. Journal of bacteriology 2000, 182, 5813–5822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.J.; Bennett, M.H.; Barton, G.R.; Jenkins, V.A.; Robertson, B.D. Adenylylation of mycobacterial Glnk (PII) protein is induced by nitrogen limitation. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2013, 93, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, L.V., Jr.; Fisher, S.H. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the Streptomyces coelicolor gene encoding glutamine synthetase. Gene 1988, 71, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, L.V., Jr.; Fisher, S.H. The Streptomyces coelicolor glnR gene encodes a protein similar to other bacterial response regulators. Gene 1993, 130, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, L.V., Jr.; Atkinson, M.R.; Fisher, S.H. Identification and cloning of the glnR locus, which is required for transcription of the glnA gene in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J Bacteriol 1991, 173, 7351–7360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.L.; Liao, C.H.; Huang, G.; Zhou, Y.; Rigali, S.; Zhang, B.; Ye, B.C. GlnR-mediated regulation of nitrogen metabolism in the actinomycete Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2014, 98, 7935–7948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalkin, H.; Smith, J.L. Enzymes utilizing glutamine as an amide donor. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol 1998, 72, 87–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumft, W.G. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews: MMBR 1997, 61, 533–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).